Abstract

Low-temperature stress (LTS) is one of the major abiotic stresses that affect crop growth and ultimately decrease grain yield. The development of rice varieties with low-temperature stress tolerance has been a severe challenge for rice breeders for a long time. The lack of consistency of the quantitative trait loci (QTLs) governing LTS tolerance for any given growth stage over different genetic backgrounds of mapping populations under different low-temperature stress conditions remains a crucial barrier for adopting marker-assisted selection (MAS). In this review, we discuss the ideal location and phenotyping for agromorphological and physiological parameters as indicators for LTS tolerance and also the traits associated with QTLs that were identified from biparental mapping populations and diverse rice accessions. We highlight the progress made in the fields of genome editing, genetic transformation, transcriptomics, and metabolomics to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of cold tolerance in rice. The stage-specific QTLs and candidate genes for LTS tolerance brought out valuable information toward identifying and improving LTS tolerance in rice varieties. We showed 578 QTLs and 38 functionally characterized genes involved in LTS tolerance. Among these, 29 QTLs were found to be colocalized at different growth stages of rice. The combination of stage-specific QTLs and genes from biparental mapping populations and genome-wide association studies provide potential information for developing LTS-tolerant rice varieties. The identified colocalized stage-specific LTS-tolerance QTLs will be useful for MAS and QTL pyramiding and for accelerating mapping and cloning of the possible candidate genes, revealing the underlying LTS-tolerance mechanisms in rice.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Low-temperature stress

- Physiological indicators

- Stage-specific QTLs and genes

- Breeding strategies

- Genetic transformation

1 Introduction

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is an important cereal crop, being the staple food for more than half of the world’s population, providing 21% of global human per capita energy (Nalley et al. 2017). Approximately one tenth of Earth’s arable land is planted to rice, which is the primary source of food. The demand for this staple crop has put more pressure on rice breeders and biotechnologists to intensify rice production systems to enhance yield productivity under drastic changes in global climatic variations (GCVs). Based on the projection of global population growth, rice production must increase its annual yield by 1.2–1.5% in the coming decades to ensure global food security (Seck et al. 2012).

Rice is grown globally in diverse ecosystems, ranging from a few meters below sea level to as high as 2700 m above mean sea level (amsl). Despite rice originating in the swampy areas of the tropics, it is susceptible to a wide range of abiotic stresses (Ranawake and Nakamura 2011). Changes in GCVs have shifted the distribution of temperature variability across the globe. These remarkable shifts have resulted in more frequent low-temperature stress/cold stress events (chilling stress and freezing stress) during the rice-growing season, especially in subtropical and temperate regions, with consequent adverse effects on rice production. Low-temperature stress (LTS) is one of the major abiotic stresses that significantly decrease rice grain yield and is experienced by 10% of the total 130 million ha of rice (Mohanty et al. 2012). For instance, rice farmers have suffered significant declines in grain yield ranging from 0.5 to 2.5 t/ha in Australia, with an average yield income loss of USD 23.2 million/year because of LTS (Farrell et al. 2001).

Low temperature affects the rice industry in Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, and South and North America. In the mountainous regions of South Korea, extremely low temperatures severely damaged rice crops in 1980 and 1993, with grain yield dropping by 26.0% and 9.2%, respectively, compared with the national average yield during those years (Schiller et al. 2001). Also, severe grain yield losses due to LTS conditions were reported in Italy, the United States (Board et al. 1980), and Chile. In India, LTS occurs in about 60% of the rice area in the northeastern and western hill states of the Himalayas, with cold stress caused by the cold irrigation water from melted snow and low ambient air temperature. LTS also directly affects crop duration, which increases relatively with cold temperature, thereby limiting to a large extent the possibility of double cropping in areas where water control is possible (Matlon et al. 1998).

Rice cultivars vary prominently in their tolerance of LTS, with subspecies indica more sensitive to LTS, while japonica cultivars are known to tolerate cold stress (Kim and Tai 2013). The rice crop is relatively sensitive to temperatures below 15 °C, which causes varying effects across different crop growth stages such as germination, seedling, vegetative, reproductive, and grain maturity (Andaya and Mackill 2003a, b). Low temperatures directly affect the crop by causing slow growth and decreased seedling vigor (Ali et al. 2006) as well as a delayed and lower percentage of germination (da Cruz and Milach 2000). At the seedling stage, manifestations of cold stress include low numbers of seedlings, decreased tillering, increased plant mortality, and induced nonuniform crop maturity (Zhang et al. 2014b). At the vegetative stage, LTS increases the growth period as exhibited by leaf discoloration or yellowing, leaf rolling or wilting, slowed growth, poor germination and seedling establishment, and the presence of rotten and dead seedlings (Lone et al. 2018). During flowering, the most sensitive stage, low temperature brings anomalies at anthesis, resulting in the cessation of anther development, nonripening of pollen, nonemergence of anthers from spikelets, improper anther dehiscence, pollen grains remaining in anther loculi, poor pollen shedding, and failure of pollen to germinate after reaching the stigmas (Suh et al. 2010; Shakiba et al. 2017).

LTS in both temperate and high-altitude rice-growing areas in the tropics and subtropics causes damaging effects throughout the growth dynamics of the crop (Ranawake and Nakamura 2015). The effect of LTS on different plant growth stages (germination, seedling, and reproductive) is crucial. In addition, there is a need for identifying an ideal location for phenotypic screening under LTS conditions, especially for agronomic, physiological, and biochemical traits to help in the development of LTS-tolerant cultivars. The establishment of genetic and genomic resources for LTS tolerance is a vital step toward the development of LTS-tolerant varieties. Over the years, the genetic and physiological perspectives of cold tolerance have been extensively studied, giving way to the development of a diverse set of criteria for evaluating the cold-tolerance phenomenon in rice at different growth stages. The rapid development of molecular markers and next-generation sequencing technology tools such as bisulfite sequencing and whole-transcriptome shotgun sequencing have been accelerated in many crop plants (Fig. 1). Several genomic regions have been studied for LTS in rice using biparental mapping populations and association mapping procedures. In this review, we have tried to organize and discuss the stage-specific QTLs and candidate genes for LTS tolerance, which could be used in LTS-tolerance rice varietal improvement programs. We also provide here the phenotypic characterization of LTS-tolerance traits at different growth stages of rice and associated genomic regions from the literature along with the traits. We also cover genome editing, genetic transformation, transcriptomics, and metabolomics tools for elucidating the molecular mechanisms of LTS tolerance in rice.

2 Phenological, Physiological, and Biochemical Indicators of LTS Tolerance at Different Developmental Stages

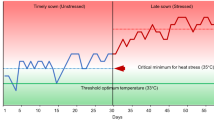

Screening for LTS in rice can be done at various growth stages (Table 1). In controlled conditions, LTS screening can be achieved timely with precision; however, it restricts the population in both sample size and number of samples. Thus, to screen large-sized populations, LTS breeding programs have resorted to evaluating many populations using cold water under field conditions (Snell et al. 2008). Such cold-water screening under field conditions has been established in research stations in Japan (Nagano 1998) and Korea (Lee 2001). The air temperature thresholds at the reproductive stage for cold-sensitive and cold-tolerant varieties are 20 °C and 15 °C, respectively (Satake 1976). Hence, high-elevation areas with low air and water temperatures, especially in subtropical regions in Kunming, People’s Republic of China (subsequently “China”), and in regions of Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh, India, are ideal spots for screening for cold tolerance (Jiang et al. 2012). Natural cold-screening hotspots that represent the target population of environments are vital for the systematic screening of germplasm and segregating breeding materials. The selection of such hotspots is crucial for the success of breeding and molecular genetic studies.

Rice is quite sensitive to LTS, mainly in tropical and subtropical regions at different growth stages. The critical temperature of the germination and reproductive stage at 15 and 17 °C has shown a significant impact on growth stage and yield decrease. However, the optimum temperature required for rice cultivation ranges from 25 to 35 °C (Yoshida 1981). The selection of LTS-tolerant rice varieties with a short duration is the key requirement for decreasing LTS damage. The effects of LTS in different growth stages, such as germination stage (GS), seedling stage (SS), and reproductive stage (RS), have significant impacts on agromorphological changes and yield component losses, especially in tropical zones. As compared to indica or indica × japonica backgrounds, japonica rice varieties have shown a wide range of LTS tolerance (da Cruz et al. 2013). The list of some LTS-tolerant rice varieties provided in Table 2 spans different countries, and most of these varieties are japonica type. However, some indica rice varieties also showed considerable LTS tolerance at the GS or SS (Biswas et al. 2017).

A few varieties have been proven to have a better performance for LTS in stage-specific growth conditions: for instance, Jinheung, Nipponbare, RNR 18805, and Italica Livorno for the GS (Miura et al. 2001; Fujino et al. 2004); M202, Lemont, and AAV002863 for the SS (Andaya and Mackill 2003b; Lou et al. 2007); and Norin PL8, Kirara397, RNR 17813, Akshaydhan, Taramati, WGL 44, Bhadrakali, JGL 3844, and WGL 44 for the RS (Saito et al. 2001; Kuroki et al. 2009). However, four rice varieties, B55, Banjiemang, Lijiangheig, and HSC55 from China and the United States, showed a consistent tolerance in three different growth stages (GS, SS, and RS) in rice (Basuchaudhuri 2014). For a further selection of LTS-tolerant rice varieties, several screening methods have been proposed, along with their pros and cons, for LTS-tolerant genotypes (Almeida et al. 2016). The selection of promising rice genotypes under natural LTS might favor negative results because of unpredictable climatic alterations in terms of stress intensity and duration of LTS. However, using high-throughput screening techniques such as image analysis, yield trait score, and robotics in controlled conditions of temperature, water, and air might help to detect tolerant genotypes and could also elucidate the traits related to morphological, biochemical, and yield-attributed traits during the plant growth period (Yang et al. 2014). Earlier studies of Snell et al. (2008), Suh et al. (2010), and Khatun et al. (2016) mentioned having developed reliable and straightforward screening methodologies for the selection of LTS-tolerant rice genotypes by preparing specific tanks for imposing cold-water irrigation and using a phytotron cabinet and low temperature in the glasshouse at different growth stages, which can provide the critical component traits. The primary focus traits for the GS related to germination rate, germination index, coefficient of germination, coleoptile length, and radicle length and also associated with early seedling vigor could be important traits for the selection of LTS tolerance at the GS (Li et al. 2018). In the SS, leaf discoloration, seedling survivability, leaf chlorophyll content, and estimation of the concentration of osmoprotectants (spermine and glycine betaine) and trehalose accumulation could be useful indicators to detect LTS at the SS (Han et al. 2004; Lou et al. 2007; Suh et al. 2012). Similarly, seed-setting rate, pollen growth development, incomplete panicle exsertion, days to flowering, spikelet fertility, and grain yield are the key traits for selection criteria at the RS (Ye et al. 2009; Jena et al. 2012; da Cruz et al. 2013). However, the natural incidence of LTS is significantly influenced to alter tolerance trait expression during phenotypic evaluation. Therefore, a combination of advanced molecular marker technology and high-throughput screening technologies provides the best method for prospecting for LTS-tolerant genotypes.

Several protocols exist to screen for cold tolerance/sensitivity in rice using different physiological and biochemical indicators. Two good indices of cold tolerance are seedling survival percentage (SSP) after subjecting seedlings to different low-temperature regimes (Morsy et al. 2007) and seedling chlorosis (Nagamine 1991). Many researchers have used SSP to analyze the resistance of transgenic plants to low temperatures (Chen et al. 2012; Huang et al. 2012). Nevertheless, the drawback of information obtained from SSP is that it is neither reproducible under natural conditions nor feasible for QTL studies. On the other hand, seedling chlorosis or the decrease in chlorophyll and leaf yellowing induced by cold stress could be captured by Soil Plant Analysis Development (SPAD) values to provide a more accurate measurement of cold stress at the seedling stage over a visual score. This indicator gives the direct association of the photosynthetic activity of the leaves, with low-temperature intensity and duration, as one of the yardsticks to screen rice germplasm and populations against cold stress (Hussain et al. 2018).

The accumulation of more dry matter and the functionality of photosystem-II (PSII) provide quantitative information on plant performance under cold-stress conditions (Gururani et al. 2015). An increase in the efficiency of PSII photochemistry gives information on the structural and functional changes in the photosystem of different plant types or transgenics, especially when the seedlings are exposed to low temperatures (Bonnecarrère et al. 2011). A sudden drop in chlorophyll integrity parameter and chlorophyll fluorescence (Fv/Fm) indicates a gas exchange decrease caused by alterations in the photosynthetic system. Therefore, combined information on gas exchange analysis and chlorophyll fluorescence is necessary to study the photosynthetic process (Saad et al. 2012) under cold stress. The expression of the AISAP gene of Aeluropus littoralis in rice confers broad tolerance of several abiotic stresses through the maintenance of photosynthetic apparatus integrity (Saad et al. 2012), particularly for PSII. The AISAP gene has become the tool to precisely evaluate for cold tolerance as it is related to final photosynthetic activity (da Cruz et al. 2013).

Biochemical parameters such as electrolyte leakage (EL), proline (Pro), and ascorbic acid (AA) were reported to be higher in sensitive variety IR50 than in resistant cultivar M202 (Kim and Tai 2011). Lee et al. (1993) showed that the exogenous application of abscisic acid (ABA) biosynthetic inhibitors resulted in low accumulation and low survival of seedlings under cold stress. Breeding varieties that accumulate higher concentrations of osmoprotectants (spermine and glycine betaine) was seen to be a strategy to overcome stresses (Yang et al. 1996), which has been proven through the development of transgenic rice that accumulates higher glycine betaine and shows resistance to LTS (Sakamoto and Murata 2002). Furthermore, the significant induction in the expression of antioxidative enzymes such as catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and ascorbate peroxidase (APEX) under cold stress (Kuk et al. 2003) explained the rate of cold tolerance (Morsy et al. 2007) by RNA interference (RNAi) (Song et al. 2011) and in transgenic rice encoding Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (sodC1) (Lee et al. 2009a, b).

The high tolerance of rice of cold stress could also be attributed to trehalose accumulation (Ge et al. 2008). Song et al. (2011) also found that accumulated amounts of trehalose can be used as an index for low-temperature tolerance/sensitivity. Increased amounts of trehalose through the overexpression of the OsNAC5 gene in transgenic rice plants were found to result in improved PSII function under abiotic stress conditions as it restricted damage due to photooxidation and exhibited soluble carbohydrates 20% higher than in nontransgenic plants (Garg et al. 2002). Similarly, at the reproductive stage, no sugar (sucrose and hexoses) accumulation has been found in anthers of low temperature-tolerant lines, resulting in no pollen grain sterility (Oliver et al. 2007). The overexpression of the gene OsAPXa (ascorbate peroxidase) in transgenic rice lines resulted in increased fertility under cold stress (Sato et al. 2011). It is also reported that unsaturated fatty acid content is related to plasma membrane stability at cold temperatures during the vegetative stage. Tolerant genotypes exhibited an increase in the amount of linolenic acid and a decrease in palmitic acid (da Cruz et al. 2010). Therefore, lipid peroxidation (Zhang et al. 2012a), along with EL (Huang et al. 2012), can be used to evaluate membrane lipid damage, which is an indirect assessment of cold tolerance.

Below the soil surface, roots play a crucial role under chilling stress, and root hydraulic conductivity (Lpr) is found to be profoundly affected when the plants are exposed to cold stress (Yamori et al. 2010). Murai-Hatano et al. (2008) found that Lpr decreased when susceptible rice genotypes were exposed to a temperature of 15 °C and the decrease was linked to transmembrane proteins, such as the aquaporins. These physiological and biochemical methods used for evaluating stress in rice genotypes and transgenic rice plants have played a significant role in understanding the crop’s mechanism of response against cold. However, most of these procedures are destructive, time-consuming, and stage-specific and are also inadequate and inappropriate for breeding programs involving the evaluation of many lines with large sample sizes. Therefore, to better understand cold-tolerance mechanisms, it is indispensable to study the phenomenon at the molecular level.

To improve the tolerance of rice of LTS, it is imperative to understand it at the molecular and physiological levels. At changing temperatures, rice plants modify their biological pathways, and molecular alterations occur within a different growth stage (Xiao et al. 2018; Ding et al. 2019). At different growth stages of rice plants, the initial effects of LTS are a decline in plasma membrane fluidity and transportation mechanism and alterations in physiological and metabolic activities, leading to disturbance of signaling processes (Ding et al. 2019). The cascades of the signaling process were followed by adjusting their cellular metabolism by activating the plasma membrane transporters and altering the metabolic responses (Fig. 2). These changes occurred in the intracellular levels by increasing abscisic acid concentrations via changes in growth hormones such as auxin and gibberellins and cross talk between the ethylene and salicylic acid signaling mechanism (Ghosh et al. 2016; Moraes De Freitas et al. 2016). These mechanisms have occurred through an alteration of membrane fluidity and the rearrangement of the cytoskeleton by the influx of calcium, which can trigger a downstream response to LTS tolerance by C-repeat binding factor: CBF-dependent (C-repeat/drought-responsive element-binding factor-dependent) and CBF-independent transcriptional pathways (Chinnusamy et al. 2010; Ma et al. 2015). Different growth stage-specific LTS-tolerance genes can be classified into three major groups as transcription factors, protein kinase genes, and functional genes, which may be involved in signal transduction pathways. Mainly, the CBF transcription factor regulates cold-responsive gene (COR) expression by binding to the CRT/DRE element. The promoter sequence of the CBF region is activated by the bHLH transcriptional activator of the inducer of CBF expression (ICE), which can also induce the expression of CBF genes toward LTS tolerance (Ito et al. 2006; Su et al. 2010). In addition to CBF pathway-related transcription factors, two genes, FRO1 (FROSTBITE 1) and OsFAD2, encode ferric reduction oxidase 1 and fatty acid desaturase 2, which are involved in LTS-tolerance mechanisms by maintaining membrane fluidity (Bevilacqua et al. 2015). The influx of calcium signals has also been associated with nitric oxide, reactive oxygen species, and mitogen-activated protein kinases, which can trigger the cascades of signaling pathways leading to LTS tolerance (Yuan et al. 2018). LTS tolerance at the germination stage is an important component trait for rapid seedling growth and uniform crop establishment, especially in the direct-seeding production system. The overexpression of the zeta class of glutathione S-transferases (OsGSTZ1) significantly improved germination rate and seedling growth under LTS (Takesawa et al. 2002). Similarly, Jin et al. (2018) identified a novel zinc finger transcription factor (OsCTZFP8) and it plays a key role in LTS tolerance at the reproductive stage in pollen fertility and seed setting along with yield per plant. Therefore, studying LTS-tolerance mechanisms at specific growth stages is crucial and may provide a better understating of key gene functions and their role in developing LTS-tolerant rice varieties in future breeding programs.

Sequential steps involved in the triggering of the signaling cascades for low-temperature stress (LTS) tolerance. Schematic representations of the LTS signal mostly processed by various biological processes such as stress perceptions and physiological and molecular responses. (1) LTS signaling initiated by ABA accumulation, and this is transduced to ABRE-containing NAC genes, which regulate the expression of NACRS genes for tolerance of LTS (Hu et al. 2008). (2) The higher concentration of ABA-induced pollen sterility occurs by increasing the expression of ABA biosynthetic genes OsZFP1 and OSNCED3 that convert zeaxanthin to xanthoxin. The LTS-tolerant plants were followed by ABA catabolism with a higher expression of two ABA-8-hydroxylase genes and further reduced to ABA concentration in anthers via C-8 hydroxylation pathways (Ji et al. 2011; Sharma and Nayyar 2016). (3) Increasing the influx of Ca2+ signals mediated by the DREB-CRT/DRE pathway under LTS, which is transduced by calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs), and MYB family transcription factors induce the stress-responsive genes. OsMYB3R-2 regulates the LTS-tolerance mechanism at the seedling stage. OsMYB3R-2 may regulate through OsCPT1, which is involved in the DREB/CBF pathway in rice (Su et al. 2010). (4) MYBS3 is a single DNA-binding repeat MYB transcription factor, which mediates sugar signaling and also tolerance of the LTS signaling pathway. Interestingly, MYBS3 has a distinct tolerance mechanism with short- and long-term adaptation of LTS tolerance by repressing the DREB1/CBF pathway and late and slow response to LTS tolerance. (5) The cascades of mitogen-activated protein kinase consist of three components (MAPKKK, MAPKK, and MAPK) activated by an excess of reactive oxygen species under LTS. Kumar et al. (2008) found that MAP kinases 4 and 6 are strongly regulated by LTS and salt stress at the seedling stage. Cytosolic thioredoxin (OsTrx23) has a potential negative regulator for MAPKs’ activity. (6) LTS can also decrease the endogenous levels of bioactive gibberellic acid (GA) by the transcriptional repression of two bioactive GA synthesis genes (GA20ox3 and GA3ox1) (Sharma and Nayyar 2016). GAs had cross-talk with other hormones to regulate the stress-response mechanism. The signal cascades of GA interact with the receptor GID1 (GA INSENSITIVE DWARF1) and GRAS family protein DELLA involved in pollen development. The two TFs (ABI3 and ABI5) bind with DELLA complex proteins, which can promote the expression of SOMNUS involved as a negative regulator of seed germination (Serrano-Mislata et al. 2017; Li et al. 2018). The cross talk with auxin and jasmonic acid-biosynthetic genes plays a major role in favoring germination under LTS. The LTS signaling and regulations of the expression of TFs and gene responses are indicated by arrows. Each pathway relates to different traits under LTS. These traits are SC stomata closure, LP lipid peroxidation, MS membrane stability, RWC relative water content, PS pollen sterility, CC cell cycle, LG leaf growth, SG seedling growth, GM germination, PD pollen development

3 Genes/QTLs Underlying LTS in Rice Detected by Linkage Mapping and GWAS

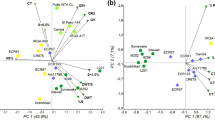

For tolerance of LTS, information on the chromosomal location of QTLs and genes is limited in different growth stage-specific traits in rice. We carried out a comprehensive literature survey, including a Gramene database (http://archive.gramene.org) search, and aggregated 578 cold-specific QTLs associated with various growth stages, including germination, seedling, and booting or reproductive stages. Among these QTLs, 239 (41.3%) were mapped through genome-wide association studies (GWAS), while 339 (58.7%) QTLs were identified from different types of biparental mapping populations, and detailed information is provided in Table 3. Based on the distribution of the reported QTLs on the chromosomes, the highest number of QTLs was noticed on chromosome 1 (65), followed by chromosome 7 (60), whereas the lowest number of QTLs was noticed on chromosome 8 (35) (Fig. 3a). Furthermore, based on the association of these QTLs with growth, stage-specific traits were classified into 214 QTLs related to GS, 249 QTLs for SS, and 115 QTLs for RS (Fig. 3b).

The physical positions of these stage-specific QTLs are depicted in Fig. 4. The QTLs were classified as main-effect QTLs (M-QTLs), based on the phenotypic variance explained by each QTL, which was ≥30%. Notably, five M-QTLs for GS-related traits (including germination rate, germination percentage, and germination index) were found on chromosomes 2, 5, and 7 (Xu et al. 2008; Cui et al. 2018); 15 M-QTLs for SS related to shoot and root growth traits on chromosomes 4, 6, 7, 8, 11, and 12 (Andaya and Mackill 2003b; Wang et al. 2009; Ranawake et al. 2014; Yu et al. 2018); and 13 M-QTLs for RS related to heading time, panicle weight, spikelet fertility, and culm length on chromosomes 1, 2, 4, 7, and 10 (Dai et al. 2004; Kuroki et al. 2009; Wainaina et al. 2018) were identified. A total of 29 QTLs were colocalized on all 12 chromosomes except on chromosomes 5 and 12 (Fig. 4 and Table 4). However, the colocalized stage-specific QTLs range from two to seven. Interestingly, the highest numbers of GS- and SS-specific QTLs were colocalized in the 22.5 Mb genomic region on chromosome 7. Three combinations of stage-specific QTLs (GS, SS, and RS) were identified on chromosome 10 in the 19.1 Mb region (Liu et al. 2013; Pan et al. 2015; Schläppi et al. 2017).

Diagram of LTS-tolerance QTLs by comprehensive literature survey and Gramene database (http://archive.gramene.org) in rice. On the right side, the numerical values in chromosome bars indicate the position of QTLs and genes in Mb, and on the left side, those indicate the QTLs for stage-specific and LTS-tolerance genes. A colored font represents the stage-specific QTLs (green: germination; blue: seedling; and red: reproductive/booting stage) and genes for LTS tolerance (pink). The octagonal shapes and numerical values represent the two different stage-specific QTLs that were colocalized in the same genetic region, and the square shape indicates the QTLs and reported LTS-tolerance genes aligned together in the same genetic regions of chromosomes

3.1 Germination Stage

Seed germination is of paramount interest for breeding varieties suitable for temperate regions and high-elevation areas, but it is given a lower priority than traits such as high yield and grain quality. To date, more than 200 QTLs (98 QTLs were identified from biparental mapping populations and 116 QTLs from GWAS) have been mapped on the 12 chromosomes (Fig. 3). The phenotypic variance of these QTLs ranges from 3.58% to 42.29%. The M-QTLs (≥30% PVE) for the GS were identified on chromosome 2 (qLTG-2-1), chromosome 5 (qLTG-5-2.1 and qLTG-5-2.2), and chromosome 7 (qGV7-1.1 and qGI7-1.2) (Xu et al. 2008; Yang et al. 2018). With a comprehensive analysis of GS-QTLs, nine genetic regions on eight chromosomes (Ch3: 17.2–17.8 Mb, Ch5: 21.5–21.6 Mb, Ch6: 5.4–6.2 Mb, Ch7: 1.7–2.7 and 20.13–22.6 Mb, Ch9: 21.9–24.6 Mb, Ch10: 11.6–14.2 Mb, Ch11: 23.0–24.2 Mb, and Ch12: 7.0–7.1 Mb) had more than four GS-QTLs that were colocalized. Recently, Yang et al. (2018) identified 12 and 23 QTLs for low-temperature germinability (LTG) and cold tolerance at the seedling stage by using recombinant inbred lines (RILs) that were derived from a backcross population of Dongnong422 and Kongyu131. Interestingly, seven QTLs on chromosome 12 in the 7.1 Mb region and four QTLs on chromosome 7 in the 22.55 Mb region were colocalized, and they were associated with several GS traits such as germination time and rate, mean length of incubation time, coefficient of germination, germination value, mean daily germination, and germination index. Cloning and characterization of the major QTL qLTG3-1, conferring more than 30% of the variation (Fujino et al. 2004), revealed that this gene encodes for a protein of unknown function. At the same time, a microarray analysis indicated that a complex metabolic and signal pathway was involved (Fujino and Matsuda 2010). Genome-wide expression analysis suggested that genes involved in defense responses were upregulated by qLTG3-1 and played a more general role in germination (Fujino et al. 2008), whereas correlation with proteomics indicated its involvement in rice growth and adaptability (Fujino and Sekiguchi 2011). With genome-wide association mapping studies, Pan et al. (2015) identified significant 17 QTLs from the 174 mini-core collections of Chinese rice accessions, 45 QTLs from the 202 Rice Mini-Core Collections (Schläppi et al. 2017), and 54 QTLs from a global collection of 400 Rice Diversity Panel 1 (Shakiba et al. 2017) that were detected under low-temperature germinability in rice. Given these challenges and potential in the form of effective QTLs (E-QTLs) with colocalization of QTLs, the development of molecular markers for selection for LTG would significantly contribute to identifying and developing LTS-tolerant varieties.

3.2 Seedling Stage

Low-temperature stress severely affects the SS, causes slow growth, yellowing symptoms on leaves, drying of leaves, and decreased early seedling vigor, and ultimately leads to seedling death (Wang et al. 2011; Lone et al. 2018). Tolerance of LTS at the SS is one of the key stages to ensure stable early seedling growth in temperate and high-altitude regions. For the genetics of the SS, several researchers have identified SS-specific QTLs using different genetic backgrounds of mapping populations such as RILs, near-isogenic lines (NILs), introgression lines, doubled haploids, and segregating F2 and F3 families (Biswas et al. 2017; Liang et al. 2018; Sun et al. 2019). However, the genetic backgrounds of japonica donors as LTS-tolerant cultivars have revealed that several QTLs and genes are controlling LTS tolerance during the SS in rice. So far, more than 249 QTLs (both major and minor) have been mapped on all of the rice chromosomes responsible for LTS tolerance at the seedling stage (Table 3). Among the total QTLs, 159 were identified from biparental mapping populations and 90 from GWAS. The phenotypic variance of these QTLs ranges from 4.51% to 60.96%. Fifteen M-QTLs (≥30% PVE) were identified on six different chromosomes: 4, 6, 7, 8, 11, and 12. However, only a few of them were M-QTLs that were colocalized with different stage-specific QTLs. For instance, qSCT4.2 (57.62% PVE) on chromosome 4 (22.3–26.91 Mb) was shared with four QTLs (qRL-4-2_23d, q9d-4, qLTG-4-2, and qHD-4) for root length, percentage of plumule growth, germination rate, and heading date under LTS conditions (Miura et al. 2001; Wainaina et al. 2018; Yu et al. 2018). Similarly, qSCT8 (60.96% PVE) on chromosome 8 (24.6–27.8 Mb) was shared with cold-tolerance seedling-stage QTL qCTS8-1 (Andaya and Mackill 2003b), seed weight per plant QTL qSWTCT8-4 (Shakiba et al. 2017), and seedling survival rate QTL qLTSSvR8-2 (Pan et al. 2015). Importantly, two M-QTLs (qCTS12a and qCTS12b) for cold-induced wilting tolerance and cold-induced necrosis tolerance on chromosome 12 had PVE of 40.6% and 41.7% (Andaya and Mackill 2003b), respectively. The same genetic region of 7.1–9.3 Mb overlapped with ten QTLs for GS- and RS-related traits such as germination index, incubation time, coefficient of germination, and seed-setting rate (Pan et al. 2015; Yang et al. 2018). Other two M-QTLs (qGAS12 and qSCT12.1) had PVE of 42.9% and 53.09%, respectively. These QTLs were associated with the growth ability of seedlings at low temperatures (Han et al. 2004) and seedling cold tolerance (Yu et al. 2018) on chromosome 12. The genetic region of 24.2–25.0 Mb was shared with GS- and SS-specific QTL qCTS12.1 (Wang et al. 2011), qLTSS12-2 (Schläppi et al. 2017), and qSWTCT12 (Shakiba et al. 2017).

The seedling-stage QTLs (seven genetic regions on seven chromosomes) were found to overlap with more than five SS-specific QTLs. The highest number of QTLs was found to overlap in the 16.3–18.4 Mb region on chromosome 10 (12 QTLs), followed by 11 QTLs on chromosomes 2 and 11 (at 14.3–17.7 and 6.8–11.3 Mb), six QTLs on chromosome 3 (2.7–3.7 Mb) and chromosome 9 (1.1–4.8 Mb), and five QTLs on chromosome 7 (22.5–23.8 Mb) and chromosome 11 (24.9–25.4 Mb), respectively. However, two chromosomes (7 and 11) have significant M-QTLs that are also colocalized with more than five QTLs. In a deeper understanding of these two chromosomes, the M-QTL qCTS7(2) on chromosome 7 (20.0–20.9 Mb) had PVE of 35.3%, and it overlapped with two other QTLs (qCTGERM7-4 and qCTB-1.7) related to GS and RS (Dai et al. 2004; Ranawake et al. 2014; Shakiba et al. 2017). Another M-QTL, qCTS11(1)-2 on chromosome 11 (20.5–26.0 Mb), had PVE of 35.6% (Ranawake et al. 2014), the same region was associated with a seed germination recovery rate QTL (qGRR11) (Jiang et al. 2017), and two SS-specific QTLs (qCTS11-9 and qCTS11-10) were identified from the GWAS analysis (Wang et al. 2016). Therefore, the combination of stage-specific QTLs with GS, SS, and RS in the same genetic region could be a promising site for identifying potential candidate genes for improving LTS tolerance in the seedling stage.

3.3 Booting/Flowering Stage

Unlike the GS and SS, the RS is highly sensitive to LTS. Many traits, such as microspore abortion, no anther dehiscence, high spikelet sterility, incomplete panicle exsertion, delayed heading, and failure to produce pollen grains, are affected by LTS in the RS (da Cruz et al. 2013; Liang et al. 2018). Several studies have detected and mapped many major- and minor-effect QTLs responsible for LTS tolerance at the booting/flowering stage using different genetic backgrounds of mapping populations (Table 3). So far, more than 100 QTLs have been mapped on all of the rice chromosomes. The QTLs for tolerance at the RS showed that 81 QTLs from biparental mapping populations and 33 QTLs from GWAS were identified from the comprehensive literature survey. The phenotypic variance of these QTLs ranges from 2.94% to 71.0%. A total of 14 M-QTLs (≥30% PVE) were located on six different chromosomes (1, 2, 4, 7, 8, and 10). Saito et al. (1995) reported two QTLs on chromosomes 3 and 4 responsible for cold tolerance at the booting stage from Norin PL8. Saito et al. (2001) also reported two OTLs (Ctb-1 and Ctb-2) on chromosome 4 governing spikelet fertility under cold stress by using a set of NILs derived from a cross between cold-tolerant rice variety Norin PL8 and cold-sensitive commercial variety Kirara397 from northern Japan. By using cool-water irrigation (19 °C), Kuroki et al. (2009) identified five QTLs for cold tolerance at the booting stage, four QTLs for days to heading, and three QTLs for culm length on chromosomes 1, 2, and 10. One of the major QTLs (qCTB.1) flanked by RM1003 and RM3482 on chromosome 1 associated with cold tolerance at the booting stage was discovered after 3 years of field trials at the National Agricultural Research Centre for Hokkaido Region, Sapporo, Japan. Similarly, eight QTLs for the booting stage were identified on chromosomes 1, 4, 5, 10, and 11 by using a set of NILs from a cold-tolerant japonica landrace (Kunmingxiaobaigu) and cold-sensitive japonica cultivar (Towada) (Xu et al. 2008). However, four QTLs (qCTB-1-1, qCTB-4-1, qCTB-5-1, and qCTB-5-2) were detected in two different environments.

A total of nine genetic regions on chromosome 1 (28.6 and 36.6 Mb), chromosome 2 (21.5 Mb), chromosome 4 (24.5 Mb), chromosome 7 (8.1 and 18.1 Mb), chromosome 8 (11.5 Mb), and chromosome 10 (9.2–9.6 and 20.0–25.2 Mb) were associated with tolerance of RS traits such as heading time, booting stage, culm length, spikelet fertility, spikelet number, and panicle weight (Dai et al. 2004; Kuroki et al. 2009; Wainaina et al. 2018). The M-QTL (qCTB_1) on chromosome 1 for cold tolerance at the booting stage had PVE of 47.3% (Kuroki et al. 2009), and it was close to the genetic region associated with SS-specific QTL qCTSR1-3 (36.9 Mb) (Zhang et al. 2018) and MYB transcription factor OsMYB3R-2 (36.1 Mb), which is bound to the mitotic-specific activator during LTS tolerance (Ma et al. 2009). The overexpression of this gene significantly enhances the many transcripts for G2/M phase-specific genes in response to cold stress. Another M-QTL (qSNP_1; 28.6 Mb) in the genetic region on the same chromosome overlapped with Osa-MIR319a. In rice, the miR319 gene family comprises two genes, Osa-MIR319a and Osa-MIR319b. Both of them are significantly involved in increasing leaf blade width under cold tolerance (Yang et al. 2013a). The colocalization of stage-specific QTLs on chromosome 2 is associated with nine QTLs (21.1–21.8 Mb) for GS- and SS-specific QTLs (Lou et al. 2007; Shakiba et al. 2017; Yang et al. 2018). Similarly, the M-QTL qPW-7 (PVE of 41%) on chromosome 7 overlapped with cold-tolerance seedling-stage QTL qCTS7-3 (Wang et al. 2016). Six M-QTLs were associated with tolerance of RS traits on chromosome 10. In the interval regions of M-QTLs, two QTLs (qLTG10-2, 21.1 Mb; qCTGERM10-4, 22.3 Mb) and one DNA-binding repeat MYB transcription factor (OsMYBS3, 22.1 Mb) are responsible for cold tolerance at the GS and SS (Su et al. 2010; Schläppi et al. 2017; Shakiba et al. 2017). The overexpression of MYBS3 confers chilling tolerance, and it has also been associated with MYBS3-mediated cold signaling pathways (Su et al. 2010). Taken together, the stage-specific QTLs of different combinations of GS, SS, and RS and associated candidate gene results could prove to be useful in breeding programs for low temperature-tolerant rice lines. These M-QTLs along with colocalized stage-specific QTLs have great potential for use in the future as their application through marker-assisted selection will hasten the process of developing cold-tolerant rice varieties for temperate and high-altitude ecosystems.

The LTS-tolerance QTLs mentioned above included a comparison of stage-specific QTL positions across different genetic backgrounds of mapping population studies. Such comparisons of stage-specific QTL positions are more informative. These QTLs may harbor potential candidate genes related to LTS, thus providing valuable information to develop LTS-tolerant rice cultivars. For this, the functionally characterized LTS-tolerance genes were collected from the OGRO database (Overview of Functionally Characterized Genes in Rice Online database) on the Q-TARO website (http://qtaro.abr.affrc.go.jp/ogro). A total of 38 candidate genes were involved in LTS tolerance in different parts of the rice plant. Specific gene functions for LTS tolerance and stages are mentioned in Table 5 and are also mapped on the genetic map (Fig. 4). Among these candidate genes, the majority of them were associated with the SS (25 genes), followed by two genes for the RS. The remaining eight genes were for the SS and RS, two genes for the GS and SS, and a single gene for the GS and RS. Functionally, the candidate genes were involved in altering the various metabolic and physiological pathways in different growth stages of LTS-tolerance mechanisms. Seven genetic regions on four chromosomes (17.9 Mb on chromosome 1; 25.6 and 34.4 Mb on chromosome 3; 15 and 25.7 Mb on chromosome 5; and 23.9 and 26.3 Mb on chromosome 6) are colocalized with candidate genes and QTLs. For example, OsSPX1 is colocalized with qCTS6-5 at 23.9 Mb on chromosome 6. A previous study revealed that OsSPX1 plays a key role in the cross talk between cold tolerance, phosphate homeostasis, and oxidative stress tolerance in the SS (Wang et al. 2013a), and the cold tolerance QTL (qCTS6-5) was mapped in the SS by using GWAS (Wang et al. 2016). Based on the fine-tuning of the interval regions of the M-QTLs, several researchers have identified many candidate genes for LTS tolerance. The M-QTLs and colocalized QTLs within identified genetic regions, especially on chromosomes 1, 3, 5, 7, and 10, may be potential genomic regions to introgress into existing moderately LTS-tolerant genotypes or mega-varieties to improve their rate of tolerance in marker-assisted breeding programs.

4 Molecular Mechanisms of LTS Tolerance

Several genes and transcription factors are involved in regulating the molecular pathways related to alteration of physiological and metabolic compounds and, further, reprogramming of their gene expression patterns against cold-stress tolerance mechanisms (Fig. 2). During LTS response, multiple sensors and signaling elements on the plasma membrane trigger the expression of COR (cold-responsive) genes via increasing cytosolic Ca2+ levels. This increase in Ca2+ is mediated by the ligand-activated Ca2+ channels. Further higher levels of Ca2+ in the cytosol lead to signal amplification through phospholipids (Williams et al. 2005; Hashimoto and Komatsu 2007; Chinnusamy et al. 2010), which are sensed by calcium-binding proteins and other transcription factors regulating the expression of LTS-tolerance genes, which can ultimately lead to adaptation and survival during cold-stress conditions (Shinozaki and Yamaguchi-Shinozaki 2000). However, the changes in various gene expression patterns are governed by a signal cascade mechanism, which also triggers the formation of plant hormones (abscisic acid, salicylic acid, and ethylene) that may be involved in integrating various stress signal pathways and controlling downstream stress responses. CBF (C-repeat/DREB [drought-responsive element-binding factor]) regulon is a highly conserved cold-response pathway (Chinnusamy et al. 2010). The ICE1–CBF transcriptional cascade plays a crucial role in cold acclimation (Zhang et al. 2004). Constitutively expressed ICE1 (inducer of CBF Expression 1) binds to the CBF promoter to activate cold-resistance genes, and overexpressing ICE1 has significantly enhanced cold tolerance in Arabidopsis (Chinnusamy et al. 2003). Similarly, ICE2 (At1g12860, a homolog of ICE1) overexpression demonstrated enhanced freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis after cold acclimation (Fursova et al. 2009). The report published showed that it interacts with the alpha subunit of the sole heterotrimeric G protein, leading to a cytosolic Ca2+ signal or itself behaving as a cold-sensing calcium channel. A Ca2+ signal may be mediated by CPKs and CBL-CIPKs, which in turn activate MAP kinases (Yang et al. 2010). Phosphorylation of transcription factors such as that of CAMTAs and ICE1/2 is supposed to be caused by activated MPKs, which in turn activate COR genes (Zhu 2016).

Most COR genes carry C-repeats or DREBs (CCGAC cis-element) in their promoters, which bind to CBFs to activate their expression (Chinnusamy et al. 2007). The induction of CBF1, CBF2, and CBF3 precedes the COR genes in response to cold stress. Constitutive overexpression studies in Arabidopsis revealed redundant functional activities of CBF1, CBF2, and CBF3 and showed different functions in cold acclimation (Gilmour et al. 2004). This was observed in the cbf2 T-DNA insertion mutant with enhanced tolerance of freezing (with or without cold acclimation), dehydration, and salt stress through increased expression of CBF1 and CBF3. Furthermore, the cold-induced expression of CBF1 and CBF3 precedes that of CBF2, revealing a temporal difference in CBF expression. These results indicate that CBF1 negatively regulates CBF3 and CBF2 to optimize the expression of downstream target genes (Doherty et al. 2009). Transgenic analysis of CBF1 and CBF3 RNAi lines revealed that both CBF1 and CBF3 are required for the full set of CBF regulon expression and freezing tolerance (Novillo et al. 2004). While responding to cold stress, ICE1 and calmodulin-binding transcription activators (CAMTAs) bind to CBF3 and CBF2 promoters, respectively, to respond to their expression (Doherty et al. 2009). Furthermore, in many cellular signaling pathways, particularly in response to cold stress, protein phosphorylation is considered crucial, and it predicts the involvement of one or more protein kinases to phosphorylate ICE1 to help in CBF expression (Chinnusamy et al. 2007; Yang et al. 2010).

4.1 Signaling Pathways Leading to LTS Tolerance from the Cloned Genes

Transgenic and gene expression analysis has helped to understand the physiological mechanisms responsible for tolerance against various abiotic stresses, including LTS, in plants (Gao et al. 2008; Moraes De Freitas et al. 2016). Using the OGRO database on the Q-TARO website, we collected 38 candidate genes that have been functionally characterized for LTS tolerance in different stages of the rice plant (Table 5 and Fig. 4). Among the total number of genes, eight were involved in the two stage-specific tolerance mechanisms of LTS. Four genes on chromosome 1 (OsCOIN, 0.2 Mb; OsGSK1, 5.7 Mb; OsGH3-2, 32.2 Mb; and OsMYB3R-2, 36.1 Mb), two genes on chromosome 6 (OsiSAP8, 24.4 Mb; and OsbZIP52, 27.3 Mb), and a single gene on chromosome 4 (OsCAF1B, 34.9 Mb) and chromosome 11 (OsAsr1, 3.2 Mb) were associated with tolerance at the SS and RS in rice.

The promising genetic regions of OsGH3-2 (Greco et al. 2012) and OsMYB3R-2 (Ma et al. 2009) showed clear evidence of seedling survival rate and seed-setting rate under cold stress. The overexpression of OsGH3-2 significantly modulates abscisic acid (ABA) and endogenous indole-2-acetic acid (IAA) homeostasis, resulting in increased cold tolerance. Furthermore, two genes (OsTPP1 and OsFAD2) on chromosome 2 and a single gene (OsZFP182) on chromosome 3 were associated with the GS, SS, and RS. Expression analysis of OsTPP1 confers a tolerance mechanism for salt and cold by activating the transcriptional regulation pathways (Ge et al. 2008). The expression pattern of OsFAD2 under LTS in different tissues in young seeds, stems, roots, and leaves plays a significant role in membrane lipid desaturation and maintenance of the lipid balance in different photosynthetic tissue (Shi et al. 2012). Meanwhile, overexpression of OsZFP182 in transgenic lines showed an increasing accumulation of various osmolytes, which resulted in an increase in tolerance of drought, cold, and salt (Huang et al. 2012).

On chromosomes 5 and 10, two genes (OsLti6b and OsPRP3) are associated with the RS. OsLti6a and OsLti6b encode membrane proteins that contribute greatly to membrane stability (Morsy et al. 2005; Kim et al. 2007). OsPRP3 is a novel flower-specific prorich protein (PRP) that is significantly overexpressed in the RS under LTS, mainly in flower development (Gothandam et al. 2010). The remaining 25 candidate genes are involved in LTS tolerance in the SS. The important upregulated or overexpressed genes/TFs concerning their expression and function in different LTS stages and in cold stress conditions are described briefly in Table 5. The overexpression of several TFs and protein kinases, such as OsISAP8, OsbHLH1, OsDREB1/CBF, ROS-bZIP, SNAC2, OsCIPK12, OsNAC6, OsCOIN, OsMAPK5, OsMYB4, and OsISAP1, confers LTS tolerance in the SS in rice (Mukhopadhyay et al. 2004; Nakashima et al. 2007; Xiang et al. 2007; Kanneganti and Gupta 2008).

For tolerance in the RS, two cell wall acid invertase genes (OsINV1 and OsINV4) and one vacuolar acid invertase gene (OsINV2) were associated with low temperature at the pollen developmental stage. Among these genes, OsINV4 is anther-specific and is downregulated by cold treatment, consequently causing a disturbance in hexose production and starch formation in the pollen grains in the tapetum cells. However, no decrease in expression of OsINV4 vis-à-vis any sucrose accumulation in the anthers and pollen grains in a cold-tolerant cultivar (R31) was observed after cold treatment (Oliver et al. 2005). The OsMAPK5 gene codes for a protein involved in kinase activity usually induced by ABA and various biotic and abiotic stresses. OX lines for the OsMAPK5 gene exhibited increased tolerance of cold and other stresses (Xiong and Yang 2003). Thus, LTS tolerance at specific growth stages involved essential stress-responsive genes and TFs, which may be potential targets in genetic improvement for LTS tolerance in rice. However, the constitutive overexpression of these genes has led to metabolic instability and yield penalty and, as observed in so many experiments, has retarded growth under normal conditions, as shown by transgenic plants (Gilmour et al. 2000; Ito et al. 2006; Nakashima et al. 2007). Using stress-inducible promoters such as the rd29A promoter instead of constitutive promoters minimizes these side effects on plant growth (Kasuga et al. 2004). However, although the complex nature of the cold-tolerance phenomenon has been explained by transgenic technology, as many genes/TFs have been exploited and manipulated, its field utility is yet to be explored and assessed.

The important COLD1 gene of Nipponbare in the background of 93-11 exhibited tolerance in the rice SS by encoding a GTPase-accelerating binding factor that regulates G-protein signaling by sensing cold to trigger Ca2+ signaling for cold tolerance (Ma et al. 2015). Five QTLs (on chromosomes 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8) were reported from the cross between chilling-tolerant Nipponbare (japonica) and chilling-sensitive 93-11 (indica) cultivars at 4 °C of cold treatment. Among these QTLs, three (COLD2, COLD4, and COLD5) were found genetically interacting with each other, and together, they contributed PV of 16.8%, while COLD1 alone exhibited PV of 7.23%. Fine-mapping of COLD1 leads to the identification of sequential alterations at the first exon (SNP1) and fourth exon (SNP2) and five substitutions in introns (SNP3) in the 4.78-kb region of the COLD1j gene (LOC_Os04 g51180). The transgenic approach proved that the SNP2 allele (COLD1jap) had a significant overexpression compared to WT plants and suggested that COLD1 modulates chilling tolerance in rice. Therefore, a good combination of stage-specific QTLs and cold-tolerance genes could be helpful for developing LTS tolerance in rice. Despite the detection of cold-tolerance genes and QTLs, to date, none of the LTS-tolerant varieties were ever developed through marker-assisted backcrossing (MAB). This raises two questions: first, are the discovered LTS tolerance-related QTLs and genes verifiably useful for MAB? Second, is there a lack of training of LTS-tolerance rice breeders to exploit the advances in molecular genetics of LTS tolerance? However, a more reliable and reproducible QTL must be first identified to improve LTS tolerance through more breeder-friendly MAB approaches.

4.2 Genome-Wide Association Studies for LTS Tolerance

The recent development in high-throughput genome sequencing platforms, GWAS, has become a powerful tool to exploit linkage disequilibrium to dissect traits and identify the genomic regions associated with a trait of interest. GWAS have been used in various research efforts such as drought, salinity, and deficiency and toxicity tolerance to understand the trait associated with the whole-genome sequence of genotypes using a diverse set of rice germplasm accessions. The sequencing of rice genotypes is commonly classified into SNP array genotypes and resequenced SNP genotypes. Zhang et al. (2018) identified high-quality filtered reads with a call rate of 95% for 3867 SNP markers by genotyping 249 indica rice varieties using a 5K SNP rice array for cold tolerance at the bud burst stage. GWAS for severity of damage (SD) and seed survival rate (SR) revealed 47 SNP loci significantly associated with SD and SR in cold treatment at 5 °C for 5 days. Among these SNPs, the major QTL qCTSR1-2 on chromosome 1 overlapped with qCTSD1-2, which explains 13.2% of the total phenotypic variation. GWAS for germination and reproductive stages that Shakiba et al. (2017) conducted with the Rice Diversity Panel 1 (RDP1), which consisted of 400 O. sativa accessions belonging to five major subpopulations, resulted in the identification of 42 loci associated with cold tolerance, and several QTLs were colocalized with previously reported LTS-tolerance QTLs. Recently, Xiao et al. (2018) identified a potential candidate locus (LOC_Os10g34840) on chromosome 10, which is responsible for cold tolerance at the seedling stage, by assessing the total diversity panel of 1033 rice accessions with 289,231 SNP markers. The loci at 18.58–18.65 Mb overlap with previously reported cold-tolerance QTLs (Xiao et al. 2015), and, furthermore, they have been fine-mapped and validated by quantitative expression analysis. Similarly, using specific locus amplified fragment sequencing (SLAF-seq) technology, Song et al. (2018) conducted GWAS with 150 accessions of rice landraces by using high-density SNPs A total of 26 significant SNPs were associated with cold tolerance at the seedling stage. These SNPs had PVE ranging from 26% to 33%, and among them, three QTLs were colocalized with previously cloned genes such as OsFAD2, OsMYB2, and OsCIPK03 related to LTS tolerance at the rice seedling stage (Yang et al. 2012). Interestingly, Song et al. (2018) noticed a strong signal of trait-marker association peaks on chromosome 1, with PVE of 27%. The expression profiling and bioinformatics analyses reveal that a novel candidate gene (Os01g0620100) showed a significant difference between the cultivars tolerant and sensitive to LTS because of the polymorphism in the WD40 domain. Thus, Os01g0620100 is an important source for developing LTS tolerance by using marker-assisted selection. A comprehensive literature survey of GWAS for LTS tolerance resulted in a total of 239 QTLs distributed on all 12 chromosomes (Fig. 3). Among these, 116 QTLs for GS, 90 QTLs for SS, and 33 QTLs for RS were reported by several researchers (Pan et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2016; Sales et al. 2017; Schläppi et al. 2017; Shakiba et al. 2017; Singh et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2018). The highest number of QTLs was detected on chromosome 2 (42), whereas the lowest number was detected on two chromosomes, 10 and 12 (14 QTLs). The physical position of each stage-specific QTL from GWAS revealed that three major genetic regions on chromosome 1 (41.39–41.86 Mb), chromosome 3 (3.03–3.76 Mb), and chromosome 6 (6.01–6.80 Mb) were colocalized with more than four QTLs. Two QTLs (qCTGERM1-8 and qSWTCT1-2) for GS and two other QTLs (qCTS1-4 and qCTS1-5) for SS stage-specific QTLs overlapped on chromosome 1 (Wang et al. 2016; Shakiba et al. 2017). Similarly, eight QTLs (qCTS3-6, qCTS3-7, qCTSR3-1, qCTSD3-1, qCTS3-8, qLTRSSR3-1, qLTSSR3-1, and qCTS3-9) detected on chromosome 3 for GS, SS, and RS were colocalized (Pan et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2018). Four QTLs associated with three traits related to germination rate, cold tolerance at the seedling stage, and plumule recovery growth after cold exposure were colocalized on chromosome 6 for the GS and SS (Wang et al. 2016; Schläppi et al. 2017; Shakiba et al. 2017). Interestingly, five chromosomal regions at 30.1 Mb (chromosome 4), 5.1 Mb (chromosome 6), 28.3 Mb (chromosome 7), 14.2 Mb (chromosome 8), and 27.3 Mb (chromosome 12) were associated with the GS, and some RS-specific QTLs were also aligned together in the same genetic regions. With a large number of QTLs for stage-specific traits from GWAS information from the genome sequencing data, high-throughput phenotyping and various statistical methods could provide beneficial information for MAB programs and the discovery of potentially useful chilling-tolerance genes/alleles . Furthermore, the combination of gene expression profiling and omics technologies such as proteomics, metabolomics, epigenetics, and genome editing tools will facilitate the confirmation of more candidate gene functions in rice.

4.3 Transcriptomics Related to LTS Tolerance

Transcriptome sequencing has increased the accessibility of genomic resources in various crops, including rice. Transcriptome analysis using microarray technologies is one of the most powerful techniques that link sequence information directly to functional genomics (Sinha et al. 2018) and immensely contributes to understanding the specific tissue- or stress response-related genes in the molecular mechanisms of biotic and abiotic stress tolerance. Comparative transcriptome analysis provides a way to distinguish different genes that are regulated in stress tolerance in comparison to expression patterns between the homologous genes in various crops (Lee et al. 2019). In response to LTS tolerance, Yang and Poovaiah (2003) observed that, at low temperatures, commonly upregulated genes were associated with Ca2+ signal transduction. Several genes such as Ca2+-dependent protein kinases, calmodulin, mitogen-activated protein kinase 1, Ca-transporting ATPases, protein phosphatase 2C family proteins, and serine/threonine-protein kinases related to signal transduction pathways were identified in the endoplasmic reticulum-phase of chilling-stress tolerance (Yang et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2012b). A key initial event that occurs in cold-stress response is the induction of the AP2/EREBP TF family, which includes CBF/DREB TFs, which are commonly induced within 30 min of cold treatment in plants (Zhang et al. 2004; Ito et al. 2006). CBF/DREB genes have also been shown to be gated by a circadian clock and to display cyclic behavior during cold stress (Gilmour et al. 2004). Previously, Bai et al. (2015), working on the anther transcriptome of photo-thermosensitive genic male sterile rice lines Y58S and P64S under cold stress, identified some differentially expressed genes (DEGs) involved in signal transduction, metabolism, transport, and transcriptional regulation. Among these DEGs, more differentially expressed MYB (myeloblastosis) and three zinc finger family TFs and signal transduction components such as calmodulin-/calcium-dependent protein kinases were observed in the Y58S comparison group. LOC_Os01g62410 (OsMYB3R-2), identified as an upregulated gene in Y58S, encodes for an MYB domain protein activation TF that regulates the CBF pathway and cell cycle progression during cold stress, resulting in increased cold tolerance (Ma et al. 2009). In a similar study, Su et al. (2010) reported the role of MYBS3 (LOC_Os10g41200) in regulating signaling pathways at low temperature, suggesting that MYB family members are good candidates for improving LTS tolerance in rice. Furthermore, molecular evidence indicates that CBF responds early, and MYBS late, to chilling stress, suggesting distinct pathways that function sequentially and complementarily to promote short- and long-term cold-stress adaptation in rice. Gene profiling on chilling-tolerant japonica rice incubated for 24 h at 10 °C revealed that an “early response” regulatory network including ROS-bZIP1 plays a crucial role in short-term adaptive responses (Yang et al. 2012). Moreover, several regulatory clusters, including bZIP factors acting on as1/ocs/TGA-like element-enriched clusters , R2R3-MYB factors acting on MYB2-like element-enriched clusters, and ERF factors acting on GCC-box/JAre-like element-enriched clusters, are involved in early chilling response, and oxidative signaling by H2O2 is at the center of the regulatory network (Yun et al. 2010).

Furthermore, genes involved in gibberellic acid (GA), indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), and cytokinin biosynthesis responded to cold temperature in such a way that their expression profiles were either downregulated or upregulated in cold-susceptible and cold-tolerant rice varieties (Park et al. 2010). For example, the IAA biosynthesis genes YUCCA1 and TAA 1:1 showed variety-specific regulation. Among the genes involved in cytokinin biosynthesis and signaling, the expression of LOG, HK1, and HK3 was significantly downregulated only in the cold-susceptible variety. Similarly, among the genes involved in ABA biosynthesis, neoxanthin synthase (NSY), and ABA-aldehyde oxidase 3 (AAO3) were downregulated only in the cold-tolerant variety. It is presumed that the levels of these bioactive hormones are maintained relatively high at cold temperatures in cold-tolerant varieties, which can help minimize the cold stress imposed on developing reproductive organs.

In a comparative transcriptome analysis of the shoots and roots of cold-tolerant variety TNG67 and cold-sensitive variety TCN1, the expression of OsRR4 type-A response regulators in roots of TNG67 was upregulated. The TFs OsIAA23, SNAC2, OsWRKY1v2, 24, 53, 71, HMGB, OsbHLH, and OsMyb were expressed in the roots or shoots of TNG67, and AP2/ERF in the shoots and roots of both varieties during cold stress, making them good candidate genes for cold-stress tolerance in rice. Also, phytohormone-related genes for ABA, polyamine, auxin, and jasmonic acid were preferentially upregulated in the shoots and roots of the cold-tolerant genotype. Functional clustering of the majority of DEGs involved in early chilling response showed their role in a complicated chilling-responsive regulatory network such as phytohormone signaling, photosynthesis pathway, ribosome translation machinery, and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. The localization of the majority of DEGs in chloroplasts suggests a link between chilling-stress tolerance in rice and photosynthesis (Wang et al. 2016). This was observed in a comparative transcriptome profiling of the common wild rice GXWR (China)-derived chilling-tolerant chromosome segment substitution line.

4.4 Proteomics Related to LTS Tolerance

Proteins are the key components in the majority of cellular events; hence, investigating their structure, function, abundance, and interactions at a given time is advantageous to “omics” studies. Protein translational and posttranslational regulations, particularly of stressor-specific protein classes altered due to stress conditions, can also be detected by proteomics, thereby rendering a complex phenomenon such as the tolerance mechanisms for cold and other stresses well understood and addressed. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DE) or liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) is used in protein extraction followed by protein separation and identification (Wittmann-Liebold et al. 2006; Fournier et al. 2007; Hashimoto and Komatsu 2007; Wang et al. 2013c).

Proteomic studies were undertaken pertaining to cold tolerance in rice seedlings and anthers (Cui et al. 2005; Yan et al. 2006; Hashimoto and Komatsu 2007; Zhang et al. 2014a; Lee et al. 2015). Comprehensive transcriptomic and proteomic analyses in rice have illustrated that many genes and functional proteins are involved in the crop’s chilling response (Hashimoto and Komatsu 2007; Nakashima et al. 2007; Kanneganti and Gupta 2008; Oh et al. 2009; Lee et al. 2015). Furthermore, many proteins, including otsA and otsB (trehalose synthesis), choline monooxygenase (glycine betaine synthesis), and WFT1 and WFT2 (fructan synthesis) (Garg et al. 2002; Shirasawa et al. 2006), were found to be involved in the regulation of low-temperature tolerance in rice. Using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) , Cui et al. (2005) observed 60 protein spots progressively upregulated in response to LTS. These cold-responsive proteins include four factors of protein biosynthesis, four molecular chaperones, two proteases, eight enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of cell wall components, and seven antioxidative enzymes and proteins linked to energy pathways as in signal transduction, besides two proteins of unknown function. In addition to these proteins, chloroplast proteome is also subject to cold stress because of the localization of identified proteins in the chloroplast. Other cold-responsive proteins are sucrose synthase (Maraña et al. 1990), phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (Sanchez-Ballesta et al. 2000), and ferritin (Kawamura and Uemura 2003). Proteins involved in energy metabolism in the leaf blade were upregulated, while defense-related proteins were downregulated or even disappeared when rice seedlings were exposed to 5 °C for 48 h (Hashimoto and Komatsu 2007). Hashimoto and Komatsu (2007) used the 2D PAGE-based proteomics method for rice root plasma membrane and identified 12 cold-responsive proteins, including cold shock protein-1, which decreased significantly under cold-stress conditions. Most of the cold-responsive proteins associated with energy production, signal transduction, protein synthesis, and defense were revealed by their functional characterization.

Proteins involved in phytohormone biosynthesis play a role in stress tolerance. Asakura et al. (2004) found that GA-related proteins have increased expression during rice seed germination. The elevated expression of GA receptor GID1L2 observed in the resistant strain suggests the role played by GA in mediating the response to cold temperature in the germinating embryo. The low-temperature germination of the resistant rice line was associated with proteins involved in GA signaling, protein trafficking, and ABA-mediated stress response compared with the susceptible strain. Colebrook et al. (2014) also noticed that increased GA biosynthesis and GA signaling were linked to stress tolerance. The elevated expression of TF HBP-1b involved in the general mechanism of protein trafficking through a secretory pathway and two proteins of unknown function, UPF0041 domain-containing protein (LOC_Os07g26700.1) and the expressed protein (LOC_Osg09910.1), suggested their possible role in seed germination or cold stress (Lee et al. 2015). Phosphorylation of cellular proteins or protein kinase activation during the initial stage of cold acclimation has also been observed (Garbarino et al. 1991), and a fragment of RuBisCO large subunit protein was phosphorylated to a greater extent than others in cold-tolerant rice varieties using 2-DE analysis (Komatsu et al. 1999).

Gel-based protein separation has been used in proteomic studies, which has resulted in the identification of only high-abundant proteins, leaving TFs, kinases, and transport proteins belonging to low-abundant protein classes undetected. Although advanced LC-based separation techniques have resulted in the detectability of low-abundant proteins, phosphorylation, glycosylation, and oxidation caused by posttranslational changes that are likely to be induced by stressors are yet to be comprehensively explained with the use of these approaches. Also, metabolic processes mediated by plant hormones as well as subcellular protein translocation and protein-protein interactions are yet to be found associated with the cold-stress phenomenon and tolerance mechanisms. To move forward with our knowledge on a time-dependent response, new proteomic strategies, such as hydrogen-deuterium exchange and surface plasmon resonance-MS, together with integrated cell biology approaches such as immune precipitation and live imaging analysis, will be required.

4.5 Metabolomics Related to LTS Tolerance

Metabolites are the final response of a biological system to environmental changes so that an aberrant metabolism is linked to the most predictive of phenotypes. The successful application of metabolomics can provide a deeper insight into a plant’s phenotypic response to abiotic stresses and can determine the pattern related to stress tolerance. For example, in a targeted metabolite analysis of two rice genotypes under LTS (13/12 °C), Morsy et al. (2007) observed that the chilling-tolerant genotype exhibited accumulated galactose and raffinose, while the same sugars were found to be decreasing in the chilling-sensitive variety. Also, a higher endogenous content of oxidative products and the presence of a more efficient reactive oxygen species (ROS)-scavenging metabolism were found in the chilling-tolerant genotype during chilling stress. Similarly, Arbona et al. (2013) studied photosynthetic dysfunction and effectors of osmotic readjustment at primary metabolite levels (sugars, amino acids, and Krebs cycle intermediates) and secondary levels (antioxidants) and observed a relative accumulation of some primary or secondary metabolites.

Most sugars have earlier been reported to function as osmoprotectants, nutrients, and signaling molecules in rice (Guy et al. 2008; Ma et al. 2009). Similar studies have been carried out in other crops (Urano et al. 2009; Bowne et al. 2012; Araújo et al. 2013). In a comparative metabolomics study between the varieties LTH (cold-tolerant japonica) and IR29 (cold-sensitive indica) under no-stress and chilling-stress conditions (4 °C for 2, 8, 24, and 48 h, and recovery of 24 h), it was observed that 82 of 106 metabolites exhibited significant differences and described 18.1% of the total PV (Zhao et al. 2013). Of the total of 120 stress vs. control comparisons, 85 (71%) cases had significantly increased amino acid levels, whereas only 7 (6%) cases had significantly decreased amino acid levels, which involved aspartic acid, cysteine, glutamic acid, and glycine. Compared to IR29, LTH recorded more amino acids that significantly increased at all times of the stress as well as considerably higher levels of cysteine, isoleucine, phenylalanine, proline, serine, threonine, and valine. This strongly suggests that differential amino acid accumulation is a general feature of the variety in response to chilling stress at the seedling stage. Regarding organic acids, 81 of 248 (33%) showed significantly decreased levels of LTH compared to IR29, whereas only 24 (10%) cases had significantly increased levels. Consistent decreased levels were obtained for four organic acids (oleic, quinic, eicosanoic, and sinapic) across all times of the stress in both genotypes, implying that energy production is remarkably inhibited in rice during chilling stress. Furthermore, 34 of 304 (11%) cases showed significantly increased levels of some sugars in LTH at later times of the stress, signifying that these late-accumulating sugars may be associated with the cold tolerance of LTH. Zhang et al. (2016) performed a comparative metabolomics study between japonica Nipponbare and indica 93-11 at six times during chilling treatment and found that amino acid accumulation occurred on a large scale and was consistent with the appearance of chilling injury. The accumulation of antioxidation-related compounds appeared earlier in Nipponbare than in 93-11 at the mid-treatment stage, whereas, during recovery, a higher level of ROS was observed in Nipponbare. Furthermore, metabolites related to stress tolerance and senescence were found to be induced/accumulated in Nipponbare and 93-11, respectively.

The combinational approaches of genome and metabolome are more interesting for phenotype prediction and are quite useful in breeding for stress tolerance. Selection based solely on genetic markers is highly biased because the environment profoundly influences most of the economic traits. The development of a metabolite quantitative trait locus (mQTL) and metabolome-wide association studies (MWAS) could be helpful in crop improvement by overcoming the problems emerging from differing environmental conditions during selection. This field will take advantage of the new plant genomes issued recently and of the modern and more powerful metabolite profiling tools (Dumas 2012; Wei et al. 2018). Some useful results at the metabolome level and the involvement of different metabolites in plant responses, as discussed above, have provided more insight into the complexity of cold-stress response. Even though this has extended our understanding of the molecular mechanism of plant response to stresses, their reconfiguration under stresses is still quite complex because of the involvement of multiple molecular pathways (Guy et al. 2008).

5 Breeding Approaches for LTS Tolerance in Rice

Developing breeding strategies for LTS-tolerant rice varieties is still a challenge to plant breeders because of the complex nature and lack of suitable rice varieties for high-latitude regions, mainly in China, Japan, Australia, and Korea. Therefore, identifying LTS-tolerance traits and breeding tolerant rice varieties are necessary for these regions. Several researchers have proposed different strategies such as adjusting sowing time, selecting suitable rice varieties with growth duration that avoids the peak LTS periods, and replacing LTS-susceptible rice varieties (Ye et al. 2009). However, with rapid changes in GCVs and the expected population increases, breeding for LTS tolerance and improving LTS-tolerance mechanisms are the critical factors to meet future global food demand.

5.1 Improving LTS Tolerance by Conventional Breeding Approaches

Cold tolerance is the ability of rice plants to sustain yield in the presence of low-temperature stress (Shakiba et al. 2017). Genetic breeding has been used as the approach to cope with low-temperature sensitivity. The indica subspecies are better adapted to tropical environments such as India, China, and Indonesia, while japonica cultivars have more adaptation under temperate climates such as those in Japan, Korea, and Java, Indonesia (Takahashi 1984). It has been observed that japonica genotypes are relatively better in tolerating a higher degree of cold stress at the germination stage (Lee 2001; da Cruz and Milach 2004) as well as at the vegetative and reproductive stages (Saito et al. 2004; da Cruz et al. 2006a; Zhang et al. 2017; Xiao et al. 2018). However, some indica genotypes from high-latitude regions may have moderate cold tolerance (Gautam et al. 2018). There are reports of some javanica, an ecotype of japonica, being tolerant of cold (Sweeney and McCouch 2007). Cold-tolerance genes from javanica cultivars such as Silewah, Lambayeque 1, and Padi Labou Alumbis were introduced into several temperate japonica breeding lines in Japan (Saito et al. 2004).

Selection under field conditions for cold tolerance in rice is unpredictable; hence, for effective selection, robust screening protocols using strong selective agents such as low temperature and the use of controlled air or low water temperature are highly important (da Cruz et al. 2006b). The major limitation to evaluating large plant populations in controlled-temperature environments is to provide enough space for the material. Growth chambers and phytotron facilities lead to quicker and more precise results; however, small-sample testing leads to a loss in effective population size. To deal with these limitations, some rice breeding programs use cold water under field conditions as a selection criterion, allowing the evaluation of many different populations and thousands of plants per population (Snell et al. 2008). Several experimental stations in Japan (Okamoto et al. 1986; Horisue et al. 1988; Nagano 1998; Shinada et al. 2013), Bangladesh (Khatun et al. 2016), and Korea (Jeong et al. 1998) have successfully used cold water to screen rice breeding material for cold tolerance. Different traits depend on the developmental stage, which is used as an indicator to identify cold-tolerant/susceptible lines. Some correlation studies revealed that varieties having germination and seedling tolerance under low-temperature conditions might also be tolerant at the booting and flowering stages (Ye et al. 2009). Inheritance and heritability of LTS tolerance at the germination stage showed involvement of both additive and nonadditive gene actions, with the latter component relatively more important for coleoptile length and coleoptile growth decrease. In a similar kind of study, epistatic interaction (a nonadditive effect) was found to be important for rice germination capacity at low temperature. Some tolerance genes may be more important, whereas others are stage-specific. No such genes have been demonstrated, which are responsible for cold tolerance over all the stages.