Abstract

Brown planthopper (BPH) is the most devastating pest of rice. Host-plant resistance is the most desirable and economic strategy in the management of BPH. To date, 29 major BPH resistance genes have been identified from indica cultivars and wild rice species, and more than ten genes have been fine mapped to chromosome regions of less than 200 kb. Four genes (Bph14, Bph26, Bph17 and bph29) have been cloned. The increasing number of fine-mapped and cloned genes provide a solid foundation for development of functional markers for use in breeding. Several BPH resistant introgression lines (ILs), near-isogenic lines (NILs) and pyramided lines (PLs) carrying single or multiple resistance genes were developed by marker assisted backcross breeding (MABC). Here we review recent progress on the genetics and molecular breeding of BPH resistance in rice. Prospect for developing cultivars with durable, broad-spectrum BPH resistance are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rice is the most important cereal crops in the Asia-Pacific region, particularly China, India, Japan, Indonesia, and Vietnam, where the brown planthopper (BPH, Nilaparvata lugens Stål) has become its most damaging insect pest. In 2005 and 2008 China reported a combined rice production loss of 2.7 million tons due to direct damage caused by BPH (Brar et al. 2009). Currently, the main method of controlling BPH is application of pesticides such as imidacloprid. However, the intensive and indiscriminate use of chemicals leads to environmental pollution, kills natural enemies of the target pest, may result in development of BPH populations that are resistant/tolerant to insecticides, ultimately leading to a resurgence in BPH populations (Lakshmi et al. 2010; Tanaka et al. 2000). Host-plant resistance is therefore most desirable and economic strategy for the control or management of BPH (Jena et al. 2006).

BPH is a migratory, monophagous rice herbivore. According to the length of the wing, adults BPH are biomorphic with varying wing lengths. The short winged cannot migrate, but produces larger amounts of eggs; BPH with long wings are able to fly between regions and bridge gaps in subsequent cropping seasons. The combined effect of the two types makes BPH an internationally explosive and devastating pest of rice. The differentiation of wing type is genetically controlled and a research group at Zhejiang University recently identified two highly homologous insulin receptor genes that play a key role in the wing differentiation (Xu et al. 2015).

Different biotypes (or races) of BPH vary in virulence (or ability to infest) different rice genotypes (Sogawa 1978). Four biotypes have been well known since the 1980s. In China, biotype 2 dominates, from the 1990s has sometimes been mixed with biotype 1 (Tao et al. 1992). However, the current population may be shifting to the more destructive Bangladesh type (Lv et al. 2009). New biotypes arise to overcome resistance genes prolonged use in a single widely used variety or suite of varieties with the same resistance gene (Cohen et al. 1997; Jing et al. 2012). For example, the first resistant variety IR26 possessing the Bph1 gene became susceptible of biotype 2 after only two years of use (Khush 1971). The genetic mechanism of BPH biotype generation in BPH is still not well understood, but there is overwhelming evidence from many plant disease/pest combinations that virulence involves the change or loss of specific effector proteins that are recognized by the plant host to induce the resistance (antibiosis) response.

Rice varieties have different mechanisms of resistance to BPH, classed as antixenosis, antibiosis and tolerance (Alam and Cohen 1998; Painter 1951). Antibiosis is the most commonly studied mechanism (Cohen et al. 1997; Du et al. 2009; Qiu et al. 2010). BPH behavior (host-searching, feeding, mating) is most obviously affected by resistant varieties through antibiosis. After infestation by BPH the rice plant activates its own stress response for defense, including secretion of insect-toxic compounds, activation of expression of genes producing metabolic inhibitors, and formation of physical barrier (such as cuticle thickening, and callose deposition) to prevent continuous feeding by BPH (Cheng et al. 2013). Hao et al. (2008) showed that plants carrying Bph14 undergo quicker deposition of callose on the sieve plate following infestation than those without the gene, suggesting that sieve tube plugging is an important mechanism for defense to BPH.

Since the development of molecular markers (SSR, InDel, SNPs) and functional genomics, the genetic studies of BPH resistance in rice have intensified. To date 29 BPH resistance genes have been detected in rice, and four (Bph14, Bph26, Bph17 and bph29) have been cloned (Du et al. 2009; Liu et al. 2015; Tamura et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2015). Both marker-assisted selection (MAS) and conventional breeding have enabled resistance genes to be combined (or ‘pyramided’) in elite rice varieties to improve BPH resistance and its durability. We review here recent progress on BPH resistance genetics and molecular breeding in rice, aiming to help a wider utilization of BPH resistance genes.

Review

BPH resistant germplasms

Evaluation of BPH resistance

A thorough evaluation of BPH resistance in the abundant germplasms is critical for identification and utilization of BPH resistance genes (Jena and Kim 2010). Various evaluation methods were developed to measure response to BPH in rice varieties. Based on the type host:pest interaction, evaluation methods can be divided into two groups. The first directly evaluates host resistance by measuring the degree of damage following BPH infestation. The modified seedbox test (SSST test) is recognized as a standard method. SSST assesses damage to seedlings (leaf yellowing, plant withering and dwarfing) caused by the progeny of an initial infestation with a set number of nymphs (Panda and Khush 1995). It is suitable time- and space-saving assay for testing of germplasm and breeding materials. However, results from this test are affected by temperature, humidity, nymphs instar, density, biotype, population and natural enemies. The second approach indirectly the relative host response by examining the physiological and biochemical reactions of the BPH (feeding rate, fecundity and survival) feeding on different varieties. Parameters measured include honeydew excretion, survival rates, preference settling, and feeding behavior (Pathak et al. 1982; Sangha et al. 2008; Klignler et al. 2005). Some t evaluation methods attempt to address host tolerance using compensation ability and yield loss rate (Dixon et al. 1990; Alam and Cohen 1998). Ultimately, all possibilities for reducing the insect population or its fitness through use host genotype must be reconfirmed in laboratory/greenhouse trials and in the field.

Source of BPH resistance

Since the 1970s, a large number of germplasm accessions have been screened for response to BPH at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) by mass screening evaluation (Jackson 1997). After searching the Genesy database (https://www.genesys-pgr.org/zh/welcome) maintained at IRRI we identified a total of 573 cultivated rice accessions that showed resistance to at least one BPH biotype. Among them, 484 accessions (92.5 %) showed resistance to biotype 1, and only 80 accessions (15.3 %) were resistant to all three biotypes (Fig. 1). Wild rice is a key source of resistant germplasm. Various species commonly show high resistance to all three biotypes. Eighteen species of wild rice, comprising 265 accessions, were highly resistant, and two species (O. officinalis and O. minuta) accounted for 41 % of the total (Fig. 2).

Frequencies of rice accessions resistant to different BPH biotypes. The data were partially selected and summarized from the Genesy database (https://www.genesys-pgr.org/zh/welcome). The total of 573 cultivated rice accessions showed resistance to at least one biotype. Biotype 1, Biotype 2 and Biotype 3 represent the number of cultivars only resistance to biotype1, 2 or 3 of BPH, respectively. 1 + 2 + 3 denotes the number of cultivars resistance to all three biotypes

The first BPH resistance was identified in 1967 (Pathak et al. 1969). Since then genes Bph1, bph2, Bph3 and bph4 have been identified in genetic analyses of various donors (Lakashminarayana and Khush 1977; Khush et al. 1985). These four genes have been used extensively in breeding programs in Southeast Asia (Jairin et al. 2007a), and a large number of BPH resistant varieties have been released by IRRI since 1976. However, some of them have lost effectiveness with the evolution and subsequent increase of new biotypes (Table 1).

Genetics of BPH resistance

Mapped BPH resistance genes

Twenty nine BPH resistance genes have been identified from ssp. indica and wild relatives (Ali and Chowdhury 2014; Wang et al. 2015). Most of these genes were located to specific rice chromosome regions, but the identities of a few (e.g. bph5 and bph8) are confusing because of the lack marker technology in early studies (Qiu et al. 2014). Since the development of molecular markers (such as SSR, InDel, and SNPs) and functional genomics increasing numbers of resistance genes have been fine mapped and some were cloned. To date, more than ten genes have been fine mapped to regions of less than 200 kb (Table 2). Most of resistance alleles are dominant, but several are a few are recessive (bph4, bph5, bph7, bph8, bph19 and bph29).

All BPH resistance genes identified to date are from indica varieties and wild relatives. Bph1-Bph9, Bph19, Bph25-Bph28 are from indica accessions, wheraes Bph10-Bph18, Bph20, Bph21, Bph27 and bph29 are from wild rice species (Table 2). Introgression lines (ILs) derived from crosses of O. sativa and wild species have been used to map many of the BPH resistance genes (Jena and Khush 1990; Brar and Khush 1997). For example, Bph18, located on 12 L, was identified in IR65482-17-216-1-2, a BPH resistant IL derived from O. australiensis. Up to now, 11 genes have been identified in wild rice, including Bph11-Bph15 were from O. officinalis, Bph10 and Bph18 were from O. australiensis, Bph20 and Bph21 were from O. minuta, and Bph27 and bph29 were from O. rufipogon.

Multiple BPH resistance genes are clustered in a similar way to blast resistance genes (Jena and Kim 2010; Ramalingam et al. 2003). For example, eight genes (Bph1, Bph2, Bph9, Bph10, Bph18, Bph19, Bph21 and Bph26) are cluster in a 22–24 Mb region on chromosome 12 L, and six (Bph12, QBph4, QBph4.2, Bph15, Bph17 and Bph20) are closely linked in a region of 5–9 Mb on chromosome 4S. Another three genes together are located within a19–22 Mb on chromosome 4 L, and four are concentrated in a 0–2 Mb region on chromosome 6S (Table 2, Fig. 3). These QTLs/gene clusters might involve different genes, different alleles at a single locus, or even the same gene, but mediate different resistance mechanisms or show different response to different BPH biotypes (Qiu et al. 2010). Additional genetic analyses, including allelism tests and gene cloning are needed to resolve these possibilities.

Multiple BPH resistance genes/QTLs with the same names are also located to different positions. For example, Bph1 from three different donors (Mudgo, TKM6 and Nori-PL3) was mapped to different positions on chromosome 12 (Table 2). Bph26 was recently cloned and sequence comparison indicated that it is the same as Bph2 (Tamura et al. 2014). Discrepancies in genetic maps have caused duplicated nomenclature for the same gene. For example, Bph27 and Bph27(t) were fine mapped to the adjacent locations on the long arm of chromosome 4 (Huang et al. 2013; He et al. 2013), and it is possible that they might be different due to their different origins (derived from wild rice and a cultivated relative, respectively). According to the rules of genetic nomenclature for rice, it is necessary for the authors of different reports to rename duplicated genes to avoid confusion to readers. Bph3 and Bph17 each described as single Mendelian factors in the resistant cultivar Rathu Heenati (RH) by different research groups. The rice scientific community has accepted the findings as Bph17 on chromosome 4 (Rahman et al. 2009, Qiu et al. 2012) and Bph3 on chromosome 6 (Jairin et al. 2010, Myint et al. 2012). These reports acknowledged in review papers (Jena and Kim, 2010, Fujita et al. 2013, Cheng et al. 2013) and on the cereal crop GRAMENE website (http://archive.gramene.org/documentation/nomenclature/) as well as Oryzabase (http://www.shigen.nig.ac.jp/rice/oryzabase/). However, Liu et al. (2015) reported the gene chromosome 4 cloned from RH as’Bph3’ when it actually originally reported as ‘Bph17’ (Sun et al. 2005). In our opinion the cloned gene on chromosome 4 (Liu et al., 2015) should have been reported as ‘Bph17’.

Mapping of minor BPH resistance QTLs

Using different mapping populations (RIL, DH, F2:3) from crosses of susceptible and resistant varieties, more QTLs were detected on all rice chromosomes except 5 and 9 (Alam and Cohen, 1998; Soundararajan et al. 2004; Liu et al. 2009; Ali and Chowdhury, 2014). However, those minor QTLs could not be confirmed due to the complex inheritance of the BPH resistance (Jena and Kim, 2010). Several studies showed that some highly resistant varieties carry many minor QTLs in addition to one or more major genes. Such combinations suggest possibilities for more durable resistance contributed by minor QTLs (Bosque-Perez and Buddenhagen 1992). For example, an elite variety IR64 from IRRI showed more durable and stable resistance than IR26, although both carry Bph1. In a further seven minor QTLs were detected on chromosomes 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 8 from IR64 (Alam and Cohen 1998). Likewise, the Sri Lankan variety Rathu Henati has shown durable resistance to all four BPH biotypes in Southeast Asia since the 1970s, as it not only carries major genes Bph3 and Bph17, but also minor QTLs on chromosomes 2, 3, 4, 6 and 10 (Jairin et al. 2007a; Kumari et al. 2010; Sun et al. 2005). A recent study showed that indica cultivar ADR52 possesses two major genes Bph25 and Bph26, along with several minor QTLs associated with resistance to BPH, white-backed planthopper (WBPH) and green leafhopper (Srinivasan et al. 2015).

Map based cloning of BPH resistance genes

Gene identity helps to clarify the molecular mechanisms of BPH resistance. Advances in sequencing technology and functional genomics have facilitated BPH resistance gene cloning. To date, Bph14, Bph26, Bph17 and bph29 have been cloned by map-based cloning.

Bph14 is the first cloned BPH resistance gene originated from O. officinalis. Bph14 was originally fine-mapped to a 34 kb region on chromosome 3 L. Sequence comparison base on two parents showed that gene Ra was unique to the resistant parent. Further genetic complementation tests determined that Ra was the Bph14, which encodes a coiled-coil, nucleotide-binding and leucine-rich repeat (CC-NB-LRR) protein. The unique LRR domain might function in specific recognition of a BPH effector, with consequent activation of the defense response, possibly through induction of a SA-dependent resistance pathway (Du et al. 2009).

Bph26 was cloned from indica variety, ADR52. Early study showed that ADR 52 carries two genes, Bph25 and Bph26 located on chromosomes 6S and 12 L, respectively (Myint et al. 2012). Like Bph14, Bph26 encodes a CC-NB-LRR protein that mediates antibiosis to BPH. Sequence comparison indicated that Bph26 is the same as Bph2, which was overcome by biotype 2. However, pyramiding of Bph25 and Bph26 could significantly improve BPH resistance, suggesting a valuable application in rice resistance breeding (Tamura et al. 2014).

Bph17 was cloned from Sri Lankan indica variety Rathu Heenati. Initially, Bph17 was fine-mapped to a 79 kb region containing four clustered genes on chromosome 4S. Transgenic tests showed that three genes independently confer resistance to BPH, and gene pyramided transgenic lines showed enhanced resistance. Bph17 is actually a cluster of three genes encoding plasma membrane-localized lectin receptor kinases (OsLecRK1—OsLecRK3), which collectively function to confer broad-spectrum, durable resistance and provide an important gene source for MAS and transgenic breeding for BPH resistance (Liu et al. 2015).

bph29, a recessive gene from O. rufipogon, fine-map to a 24 Kb region on chromosome 6S. Through a transgenic experiment, the bph29 allele from the susceptible variety was transferred into the resistant variety, and the positive progenies were susceptible, whereas the negative progenies retained high resistance. bph29 encodes a B3 DNA-binding protein. Expression patterns analysis showed that bph29 is restricted to the vascular tissue where BPH attacks. Expression of bph29 activates the SA signaling pathway and suppresses the jasmonic acid/ethylene (JA/Et)-dependent pathway after BPH infestation and induces callose deposition in phloem cells, resulting in antibiosis to BPH (Wang et al. 2015).

Genes and TFs associated with BPH resistance

In addition to the traditional map-based cloning method, some genes and transcription factors (TFs) associated with BPH resistance have been identified through reverse genetics approaches such as T-DNA mutants and genes homology. Bphi008a is a resistance gene that is induced by BPH feeding; it is involved in ethylene signaling. Plants carrying a transgenic Bphi008a allele show significantly enhanced resistance to BPH (Hu et al. 2011b). Another two genes, OsERF3 and OsHI-LOX, are ethylene response factors and lipoxygenase genes, respectively, involved in a JA/Et-dependent pathway and act as inhibitor of the gene expression to improve resistance to BPH (Lu et al. 2011; Zhou et al. 2009). With the development of rice genomics and proteomics, continued screening and validation of genes that are regulated by BPH feeding, and clarification of resistance mechanisms will promote research of BPH—associated genes and offer possibilities for resistance breeding.

Molecular breeding for BPH resistance

Since the 1970s, several BPH resistance genes such as Bph1, bph2, Bph3 and bph4 have been identified and transferred into elite susceptible varieties at IRRI, and a series of improved cultivars (e.g. IR26, IR36, IR50 and IR72) with BPH resistance were developed and released (Jairin et al. 2007a; Jena and Kim, 2010). However, the improved cultivars carrying single resistance gene lose effectiveness due to the evolution of new biotypes (Jena and Kim 2010). Therefore, to develop new varieties with more durable and stable BPH resistance, there has to be use of more genes, preferably pyramided into multiple gene lines or possibly deployed in multiline single gene mixtures such that new biotypes will be hampered or delayed.

Integrating MAS into conventional rice breeding

MAS greatly increases the efficiency and effectiveness of breeding. By determining and developing DNA markers for target genomic regions, desired individuals possessing particular genes or QTLs can be identified in germplasm collections based on genotyping rather than phenotyping (Collard et al. 2005). New strategy that fits breeder requirements should include a planned MAS strategy, MAS-based backcrossing breeding (MABC) and gene pyramiding (Fig. 4).

An integrated strategy of MAS and conventional breeding. MAS strategy is in the center position throughout the entire process of breeding. The primary goal is development of useful markers tightly linked to target QTLs/genes by QTL mapping experiments (primary mapping, fine mapping and QTL validation). MABC include three generations of backcrosses and one generation of selfing, accompanied by positive and negative selection for minimizing the donor segments linked to target gene, and background selection for maximizing the recurrent genome. After phenotype evaluation of BC3F2 lines, NILs containing single target gene are obtained. Multiple NILs that carrying different genes are crossed each other to produce pyramided lines. MAS based conventional breeding include 8–9 generations of selfing, accompanied by multiple cross within three parents, field and MAS selection in a large F2 population, preliminary and further yield trials in F3 and F4-8 population. After phenotype evaluation, the F8-9 progenies with enhanced target traits and high yield potential could be obtained, designated as ‘improved versions’

Construction of a MAS system for using BPH resistance genes

The efficiency of MAS largely depends on the distance between molecular markers and genes/QTLs associated with target traits. The development of useful markers tightly linked to target traits is accomplished by QTL mapping experiments. Generally, the markers are validated in fine mapping studies. Based on the positional information of BPH-resistance genes previously reported (Table 2), SSR and InDel markers adjacent to related genes were designed, and used to track the target genes in the segregating generation, and to test whether these markers were closely linked with genes. Thus, several MAS systems with high efficiency associated with these genes were developed (Table 3).

MABC for BPH resistance

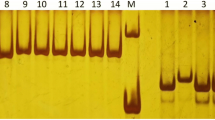

It takes a minimum of 6–8 backcrosses to fully recover a recurrent parent genome using conventional breeding methods, but MABC enables the procedure to be shortened to 3 or 4 backcrosses (Tanksley et al. 1989). There are three levels of selection in which markers are applied in backcross breeding (Fig. 5). Firstly, markers are used to select target alleles whose effects are difficult to observe phenotype (e.g. resistance in the absence of actual disease/pest tests), this is referred to as ‘positive selection’; secondly, markers are used to select for progeny with the target gene and tightly-linked flanking markers in order to produce chromosomes that harbor the target allele with minimal surrounding DNA from the donor parent (minimizing linkage drag), designated as ‘negative selection’ or ‘recombinant selection’; thirdly, markers that are distributed across all 12 rice chromosomes can be selected for recovery of the recurrent parent genome, known as ‘background selection’. A typical example of MABC that used markers for all three objectives was performed by Chen et al. (2000).

MABC has been used to develop multiple BPH-resistance introgressions (ILs) or near-isogenic lines (NILs). Using a Bph18-cosegergation marker 7312. T4A for positive selection, and 260 SSR markers across all rice 12 chromosomes for background selection, Bph18 was transferred into an elite japonica variety ‘Junambyeo’ and ILs with enhanced BPH resistance were developed (Suh et al. 2011). Using negative selection, linkage drag between Bph3 and Wx a alleles was successfully broken resulting in ILs with broad spectrum BPH resistance and good quality (Jairin et al. 2009). In our laboratory, a number of genes (Bph3, Bph6, Bph9, Bph14, Bph15, Bph10, Bph18, Bph20, QBph4, QBph3) were individually incorporated into 9311 (an elite variety in China) using MABC, and a set of NILs was developed with enhanced BPH resistance. These NILs harbor target gene regions of less than 100 kb and the recurrent parent genome (>99.5 %) was recovered with a breeding chip with high-density SNP markers for negative and background selection (data unpublished).

Pyramiding BPH resistance genes

Using MAS, we can simply and easily combine multiple genes/QTLs together into a single genotype simultaneously. Through conventional breeding to pyramid traits, individual plants/lines must be phenotypically screened for all tested traits. However, it may be impossible or extremely difficult to pyramid traits such as pest resistance where unique biotypes may be needed for screening as the presence of one gene may prevent phenotypic selection for others. Pyramiding of resistance genes or QTLs in rice has now become an effective method for developing lines with disease and pest resistance (Divya et al. 2014; Dokku et al. 2013; Jiang et al. 2015; Pradhan et al. 2015; Singh et al. 2015; Suh et al. 2013; Wan et al. 2014).

Using MAS based conventional breeding, progress has been made in pyramiding two or more major BPH resistance genes into susceptible cultivars. The pyramided lines (PLs) carrying Bph1 and bph2 genes showed higher resistance than the lines with only bph2 (Sharma et al. 2004). Qiu et al. (2012) used MAS for pyramiding Bph6 and Bph12 genes into japonica and indica cultivars. The PLs had stronger resistance level than ILs with Bph6 alone, followed by the single-Bph12 ILs. In addition, three dominant BPH resistance genes (Bph14, Bph15, Bph18) were pyramided into the elite indica rice 9311 and its hybrids using MABC. The results showed an additive effect of those pyramiding genes, the order of the gene effect being 14/15/18 ≥ 14/15 > 15/18 ≥ 15 > 14/18 ≥ 14 ≥ 18 > none (Hu et al. 2013). Additionally, pyramiding BPH resistance genes and other resistances have become routine in rice breeding. Wan et al. (2014) reported development of a new elite restorer line possessing tolerance to BPH, stem borer, leaf folder and herbicide through pyramiding Bph14, Bph15, Cry1C, and glufosinate-resistance gene bar.

In order to develop new cultivars with durable BPH resistance, we should not only use gene pyramiding, but exploit genetic diversity for ecological reasons. Zhu et al. (2000) reported an example of genetic diversity and blast disease control in rice. Furthermore, multiple NILs were developed representing all possible combinations of several blast resistance QTLs/genes from a durably resistant cultivar (Fukuoka et al. 2015; Khanna et al. 2015). Similarly, we have pyramided Bph14 and Bph15 into several different rice hybrids, and experiments indicated that planting resistant pyramided hybrids around conventional susceptible hybrids significantly reduced the overall population of BPH over a large field area, thereby reducing the BPH threat and contributing to sustainable of rice production (Hu et al. 2011a). Moreover, multilines (NILs, ILs, or PLs) carrying different assortments of genes should also help in containing BPH populations to manageable levels.

Conclusion and perspective

In the recent years, significant progress has been made in molecular breeding of rice for yield, quality, biotic and abiotic stress resistances and certain agronomic traits (Rao et al. 2014). However, the genetics rice: BPH interaction and molecular breeding for BPH resistance have been restrained due to the intricacy of interaction between rice and BPH. Host—plant resistance is an effective environmentally friendly approach to control BPH and maintain yield potential of cultivars (Jena and Kim, 2010). Future breeding approaches must focus on developing cultivars with durable, broad-spectrum resistance.

The first objective is to identify and characterize new resistance genes from diverse germplasm resources, particularly wild species. The second objective is to understand the molecular interactions between rice and BPH. We should not only accelerate research on map-base cloning of BPH resistance genes, but also pay attention to and the genome and genetics of BPH itself. The BPH genome was sequenced and genomes of BPH and its endosymbionts revealed complex complementary contributions for host adaptation (Xue et al. 2014). Mapping of the rice resistance-breaking gene of the BPH has facilitated understanding of interactions of BPH and rice (Jing et al. 2014; Kobayashi et al. 2014). The third objective is to pyramid major genes or QTLs or to deploy NILs or ILs carrying multiple single resistance genes in multilines. Recently, molecular breeding design (MDB) have become popular for molecular breeding in crop improvement and should contribute to future breeding outcomes (Xu and Zhu, 2012). Molecular breeding designs for BPH resistance will involve three steps: (1) map all QTLs for BPH resistance by high-throughput genotyping and reproducible phenotyping; (2) evaluate and reconfirm allelic variation in these QTLs by development of NILs; and (3) conduct design breeding according to a bioinformatics platform and simulation studies. The final objective is to develop new varieties that contain the best genotypic combinations to confer durable resistance.

References

Alam SN, Cohen MB (1998) Detection and analysis of QTLs for resistance to the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens, in a doubled-haploid rice population. Theor Appl Genet 97:1370–1379

Ali MP, Chowdhury TR (2014) Tagging and mapping of genes and QTLs of Nilaparvata lugens resistance in rice. Euphytica 195:1–30

Brar DS, Khush GS (1997) Alien introgression in rice. Plant Mol Biol 35:35–47

Brar DS, Virk PS, Jena KK et al (2009) Breeding for resistance to planthoppers in rice. Planthopper: new threats to the sustainability of intensive rice production systems in Asia. IRRI. p 401-427

Bosque-Perez NA, Buddenhagen IW (1992) The development of host-plant resistance to insect pests: outlook for the tropics. In: Menken SBJ, Visser JH, Harrewijn P (eds) Proc 8th Int Symp insect-plant relationships. Kluwer, Dordrecht, pp 235–249

Cha YS, Ji H, Yun DW et al (2008) Fine mapping of the rice Bph1 gene, which confers resistance to the brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens) and development of STS markers for markerassisted Selection. Mol Cells 26:146–151

Cheng XY, Zhu LL, He GC (2013) Towards understanding of molecular interactions between rice and the brown planthopper. Mol Plant 6:621–634

Chen JW, Wang L, Pang F (2006) Genetic analysis and fine mapping of a rice brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens Stål) resistance gene bph19(t). Mol Genet Genomics 275:321–329

Chen S, Lin XH, Xu CG et al (2000) Improvement of bacterial blight resistance of ‘Minghui 63’, an elite restorer line of hybrid rice, by molecular marker-assisted selection. Crop Sci 40:239–244

Cohen MB, Alam SN, Medina EB et al (1997) Brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens, resistance in rice cultivar IR64: mechanism and role in successful N. lugens management in Central Luzon, Philippines. Entomol Exp Appl 85:221–229

Collard BCY, Jahufer MZZ, Brouwer JB et al (2005) An introduction to markers, quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping and marker-assisted selection for crop improvement: The basic concepts. Euphytica 142:169–196

Dixon AGO, Bramel-Cox PJ, Reese JC et al (1990) Mechanism of resistance and their interactions in 12 sources of resistance to biotype E greenbug (Homoptera: Aphididae). J Econ Entomol 83:234–240

Divya B, Robin S, Rabindran R et al (2014) Marker assisted backcross breeding approach to improve blast resistance in Indian rice (Oryza sativa) variety ADT43. Euphytica 200:61–77

Dokku P, Das KM, Rao GJN (2013) Pyramiding of four resistance genes of bacterial blight in Tapaswini, an elite rice cultivar, through marker-assisted selection. Euphytica 192:87–96

Du B, Zhang WL, Liu BF et al (2009) Identification and characterization of Bph14, a gene conferring resistance to brown planthopper in rice. P Natl Acad Sci USA 106:22163–22168

Fujita D, Kohli A, Horgan FG (2013) Rice resistance to planthoppers and leafhoppers. Critical Reviews in Plant Sci 32:162–191

Fukuoka S, Saka N, Mizukami Y et al (2015) Gene pyramiding enhances durable blast disease resistance in rice. Sci Rep 5:7773

Hao P, Liu C, Wang Y et al (2008) Herbivore-induced callose deposition on the sieve plates of rice: an important mechanism for host resistance. Plant Physiol 146:1810–1820

Hu J, Cheng MX, Gao GJ et al (2013) Pyramiding and evaluation of three dominant brown planthopper resistance genes in the elite indica rice 9311 and its hybrids. Pest Manag Sci 69:802–808

Hu J, Li X, Wu CJ et al (2012) Pyramiding and evaluation of the brown planthopper resistance genes Bph14 and Bph15 in hybrid rice. Mol Breeding 29:61–69

Hu J, Xiao C, Cheng MX et al (2015a) Fine mapping and pyramiding of brown planthopper resistance genes QBph3 and QBph4 in an introgression line from wild rice O. officinalis. Mol Breeding 35:3. doi:10.1007/s11032-015-0228-2

Hu J, Xiao C, Cheng MX et al (2015b) A new finely mapped Oryza australiensis-derived QTL in rice confers resistance to brown planthopper. Gene 561:132–137

Hu J, Yang CJ, Zhang QL et al (2011a) Resistance of pyramided rice hybrids to brown planthoppers. Chinese J Appl Entom 48:1341–1347 (in Chinese with english abstract)

Hu J, Zhou J, Peng X et al (2011b) The Bphi008a gene interacts with the ethylene pathway and transcriptionally regulates MAPK genes in the response of rice to brown planthopper feeding. Plant Physiol 156:856–872

He J, Liu YQ, Liu YL et al (2013) High-resolution mapping of brown planthopper (BPH) resistance gene Bph27(t) in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Mol Breeding 31:549–557

Hirabayashi H, Angeles ER, Kaji R et al (1998) Identification of brown planthopper resistance gene derived from O. officinalis using molecular markers in rice. Breed Sci 48(Suppl):82, in Japanese with english abstract

Hirabayashi H, Kaji R, Angeles ER et al (1999) RFLP analysis of a new gene for resistance to brown planthopper derived from O. officinalis on rice chromosome 4. Breed Sci 48:48–53 (in Japanese with english abstract)

Huang D, Qiu Y, Zhang Y et al (2013) Fine mapping and characterization of BPH27, a brown planthopper resistance gene from wild rice (Oryza rufipogon Griff.). Theor Appl Genet 126:219–229

Ishii T, Brar DS, Multani DS et al (1994) Molecular tagging of genes for brown planthopper resistance and earliness introgressed from Oryza australiensis into cultivated rice, O. sativa. Genome 37:217–221

Jackson MT (1997) Conservation of rice genetic resources: the role of the International Rice Genebank at IRRI. Plant Mol Biol 35:61–67

Jairin J, Phengrat K, Teangdeerith S et al (2007a) Mapping of a broad-spectrum brown planthopper resistance gene, Bph3, on rice chromosome 6. Mol Breeding 19:35–44

Jairin J, Sansen K, Wongboon W et al (2010) Detection of a brown planthopper resistance gene bph4 at the same chromosomal position of Bph3 using two different genetic backgrounds of rice. Breeding Sci 60:71–75

Jairin J, Teangdeerith S, Leelagud P et al (2007b) Detection of brown planthopper resistance genes from different rice mapping populations in the same genomic location. Sci Asia 33:347–352

Jairin J, Teangdeerith S, Leelagud P et al (2009) Development of rice introgression lines with brown planthopper resistance and KDML105 grain quality characteristics through marker-assisted selection. Field Crop Res 110:263–271

Jena KK, Jeung JU, Lee JH et al (2006) High-resolution mapping of a new brown planthopper (BPH) resistance gene, Bph18(t), and marker-assisted selection for BPH resistance in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Theor Appl Genet 112:288–297

Jena KK, Khush GS (1990) Introgression of genes from Oryza officinalis Well exWatt to cultivated rice, O. sativa L. Theor Appl Genet 80:737–745

Jena KK, Kim SM (2010) Current status of brown planthopper (BPH) resistance and genetics. Rice 3:161–171

Jena KK, Pasalu IC, Rao YK et al (2003) Molecular tagging of a gene for resistance to brown planthopper in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Euphytica 129:81–88

Jiang JF, Yang DB, Ali J et al (2015) Molecular marker-assisted pyramiding of broad-spectrum disease resistance genes, Pi2 and Xa23, into GZ63-4S, an elite thermo-sensitive genic male-sterile line in rice. Mol Breeding 35:83. doi:10.1007/s11032-015-0282-9

Jing S, Liu B, Peng L et al (2012) Development and use of EST-SSR markers for assessing genetic diversity in the brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens (Stål)). B Entomol Res 102:113–122

Jing S, Zhang L, Ma Y et al (2014) Genome-wide mapping of virulence in brown planthopper identifies loci that break down host plant resistance. PLoS One 9:e98911. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0098911

Kawaguchi M, Murata K, Ishii T et al (2001) Assigment of a brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens Stål) resistance gene bph4 to the rice chromosome 6. Breed Sci 51:13–18

Khanna A, Sharma V, Ellur RK et al (2015) Development and evaluation of near-isogenic lines for major blast resistance gene(s) in Basmati rice. Theor Appl Genet 128:1243–1259

Khush GS (1971) Rice breeding for disease and insect resistance at IRRI. Oryza 8:111–119

Khush GS, Karim AR, Angeles ER (1985) Genetics of resistance of rice cultivar ARC 10550 to Bangladesh brown planthopper biotype. J Genet 64:121–125

Kim SM, Sohn JK (2005) Identification of rice gene (Bph1) conferring resistance to brown plant hopper (Nilaparvata lugens Stål) using STS markers. Mol Cells 20:30–34

Klignler J, Creasy R, Gao LL et al (2005) Aphid resistance in Medicago truncatula involves antixenosis and phloem-specific, inducible antibiosis, and maps to a single locus flanked by NBS-LRR resistance gene analogs. Plant Physiol 137:1445–1455

Kobayashi T, Yamamoto K, Suetsugu Y et al (2014) Genetic mapping of the rice resistance-breaking gene of the brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens. Proc Biol Sci 281:20140726

Kumari S, Sheba JM, Marappan M et al (2010) Screening of IR50 x Rathu Heenati F7 RILs and identification of SSR markers linked to brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens Stål) resistance in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Mol Biotechnol 46:63–71

Lakashminarayana A, Khush GS (1977) New genes for resistance to the brown planthopper in rice. Crop Sci 17:96–100

Lakshmi VJ, Krishnaiah NV, Katti G et al (2010) Development of insecticide resistance in rice brown planthopper and whitebacked planthopper in Godavari Delta of Andhra Pradesh. Indian J. Plant Prot 38:35–40

Liu Y, Su C, Jiang L et al (2009) The distribution and identification of brown planthopper resistance genes in rice. Hereditas 146:67–73

Liu YQ, Wu H, Chen H et al (2015) A gene cluster encoding lectin receptor kinases confers broadspectrum and durable insect resistance in rice. Nat Biotechnol 33:301–305

Lu J, Ju H, Zhou G et al (2011) An EAR-motif-containing ERF transcription factor affects herbivore-induced signaling, defense and resistance in rice. Plant J 68:583–596

Lv WT, Du B, Shangguan XX et al (2014) BAC and RNA sequencing reveal the brown planthopper resistance gene BPH15 in a recombination cold spot that mediates a unique defense mechanism. BMC Genomics 15:674–589

Lv ZP, Yang CJ, Hua HX (2009) Identification of the biotypes of the brown planthopper (BPH) in Wuchang area. Hubei Agricultural Sciences 48:1369–1370 (in Chinese with English abstract)

Murai H, Hashimoto Z, Sharma P et al (2001) Construction of a high resolution linkage map of a rice brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens Stål) resistance gene bph2. Theor Appl Genet 103:526–532

Murata K, Fujiwara M, Murai H et al (2001) Mapping of a brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens Stål) resistance gene Bph9 on the long arm of chromosome 12. Cereal Res Commun 29:245–250

Myint K, Fujita D, Matsumura M et al (2012) Mapping and pyramiding of two major genes for resistance to the brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens [Stål]) in the ricecultivar ADR52. Theor Appl Genet 124:495–504

Painter RH (1951) Insect resistance in crop plants. Macmillan Co., New York

Panda N, Khush GS (1995) Host plant resistance to insects. CAB International, Wallingford, p 431

Pathak MD, Cheng CH, Furtono ME (1969) Resistance to Nephotettix cincticeps and Nilaparvata lugens in varieties of rice. Nature 223:502–504

Pathak PK, Saxena RC, Heinrichs EA (1982) Parafilm sachet for measuring honeydew excretion by Nilaparvata lugens on rice. J Econ Entomol 75:194–195

Pradhan SK, Nayak DK, Mohanty S et al (2015) Pyramiding of three bacterial blight resistance genes for broad-spectrum resistance in deepwater rice variety, Jalmagna. Rice 8:19. doi:10.1186/s12284-015-0051-8

Qiu Y, Guo J, Jing S et al (2010) High-resolution mapping of the brown planthopper resistance gene Bph6 in rice and characterizing its resistance in the 93–11 and Nipponbare near isogenic backgrounds. Theor Appl Genet 121:1601–1611

Qiu Y, Guo J, Jing S et al (2012) Development and characterization of japonica rice lines carrying the brown planthopper-resistance genes BPH12 and BPH6. Theor Appl Genet 124:485–494

Qiu YF, Guo JP, Jing SL et al (2014) Fine mapping of the rice brown planthopper resistance gene BPH7 and characterization of its resistance in the 93-11background. Euphytica 198:369–379

Rahman ML, Jiang W, Chu SH et al (2009) High-resolution mapping of two rice brown planthopper resistance genes, Bph20(t) and Bph21(t), originating from Oryza minuta. Theor Appl Genet 119:1237–1246

Ramalingam J, Vera Cruz C, Kukreja K et al (2003) Candidate defense genes from rice, barley, and maize and their association with qualitative and quantitative resistance in rice. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact 16:14–24

Rao YC, Li YY, Qian Q (2014) Recent progress on molecular breeding of rice in China. Plant Cell Rep 33:551–564

Renganayaki K, Fritz AK, Sadasivam S et al (2002) Mapping and progress toward map-based cloning of brown planthopper biotype-4 resistance gene introgressed from Oryza officinalis into cultivated rice. O. sativa. Crop Sci 42:2112–2117

Sangha JS, Chen YH, Palchamy K et al (2008) Categories and inheritance of resistance to Nilaparvata lugens (Hemiptera: Delphacidae) in mutants of indica rice ‘IR64’. J Econ Entomol 101:575–583

Sharma PN, Ketipearachchi Y, Murata K et al (2002) RFLP/AFLP mapping of a brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens Stål) resistance gene Bph1 in rice. Euphytica 129:109–117

Sharma PN, Torii A, Takumi S et al (2004) Marker-assisted pyramiding of brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens Stål) resistance genes Bph1 and Bph2 on rice chromosome 12. Hereditas 140:61–69

Singh AK, Singh VK, Singh A et al (2015) Introgression of multiple disease resistance into a maintainer of Basmati rice CMS line by marker assisted backcross breeding. Euphytica 203:97–107

Sogawa K (1978) Quantitative morphological variations among biotypes of the brown planthopper. Rice Res Newsl 3:9–10

Soundararajan RP, Kadirvel P, Gunathilagaraj K et al (2004) Mapping of quantitative trait loci associated with resistance to brown planthopper in rice by means of a doubled haploid population. Crop Sci 44:2214–2220

Srinivasan TS, Almazan MLP, Bernal CC et al (2015) Current utility of the BPH25 and BPH26 genes and possibilities for further resistance against plant- and leafhoppers from the donor cultivar ADR52. Appl Entomol Zool 50:533–543

Su CC, Zhai HQ, Wang CM et al (2006) SSR mapping of brown planthopper resistance gene Bph9 in Kaharamana, an indica rice (Oryza sativa L.). Acta Genet Sin 33:262–268

Suh JP, Jeung JU, Noh TH et al (2013) Development of breeding lines with three pyramided resistance genes that confer broad-spectrum bacterial blight resistance and their molecular analysis in rice. Rice 6:5

Suh JP, Yang SJ, Jeung JU et al (2011) Development of elite breeding lines conferring Bph18 gene-derived resistance to brown planthopper (BPH) by marker-assisted selection and genome-wide background analysis in japonica rice (Oryza sativa L.). Field Crop Res 120:215–222

Sun LH, Wang CM, Su CC et al (2006) Mapping and marker-assisted selection of a brown planthopper resistance gene bph2 in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Acta Genet Sin 33(8):717–723

Sun L, Su C, Wang C et al (2005) Mapping of a major resistance gene to brown planthopper in the rice cultivar Rathu Heenati. Breed Sci 55:391–396

Tamura Y, Hattori M, Yoshioka H et al (2014) Map-based cloning and characterization of a brown planthopper resistance gene BPH26 from Oryza sativa L. ssp. indica cultivar ADR52. Sci Reports 4:5872

Tanaka K, Endo S, Kazana H (2000) Toxicity of insecticides to predators of rice planthoppers: Spiders, the mirid bug and the dryinid wasp. Appl Entomol Zool 35:177–187

Tanksley SD, Young ND, Paterson AH et al (1989) RFLP mapping in plant breeding: new tools for an old science. Bio/Technology 7:257–263

Tao LY, Yu XP, Wu GR (1992) Preliminary monitoring the biotypes of the brown planthopper Nilaparvata Lugens Stål in China. Scientia Agricultura Sinica 25:9–13 (in Chinese with English abstract)

Wan BL, Zha ZP, Li JB et al (2014) Development of elite rice restorer lines in the genetic background of R022 possessing tolerance to brown planthopper, stem borer, leaf folder and herbicide through marker-assisted breeding. Euphytica 195:129–142

Wang Y, Cao LM, Zhang YX et al (2015) Map-based cloning and characterization of BPH29, a B3 domain-containing recessive gene conferring brown planthopper resistance in rice. J Exp Bot 66:6035–6045

Wu H, Liu YQ, He J et al (2014) Fine mapping of brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens Stål) resistance gene Bph28(t) in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Mol Breeding 33:909–918

Xue J, Zhou X, Zhang CX et al (2014) Genomes of the rice pest brown planthopper and its endosymbionts reveal complex complementary contributions for host adaptation. Genome Biol 15:521

Xu HJ, Xue J, Lu B et al (2015) Two insulin receptors determine alternative wing morphs in planthoppers. Nature 519:464–467

Xu H, Zhu J (2012) Statistical approaches in QTL mapping andmolecular breeding for complex traits. Chin Sci Bull 57:2637–2644

Zhou G, Qi J, Ren N et al (2009) Silencing OsHI-LOX makes rice more susceptible to chewing herbivores, but enhances resistance to a phloem feeder. Plant J 60:638–648

Zhu Y, Chen H, Fan J et al (2000) Genetic diversity and disease control in rice. Nature 406:718–722

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Weiren Wu for valuable advice on this review. This work was supported in part bygrants from the National High Technology Research (2014AA10A600), the National Program on Research and Development of Transgenic Plants (2016ZX08001002-002), the National Natural Science Foundation (31371701, 31401355) and the Foundation of the Ministry of Agriculture of China (CARS-01-03) and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

JH and YQH wrote the manuscript. YQH acted as corresponding author. All authors read and approved of the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, J., Xiao, C. & He, Y. Recent progress on the genetics and molecular breeding of brown planthopper resistance in rice. Rice 9, 30 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-016-0099-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-016-0099-0