Abstract

Background

Wheat stripe rust, caused by Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici (Pst), is one of the most devastating diseases of the wheat crop. It causes significant reductions in both grain yield and grain quality. In recent years, new and more virulent races have overcome many of the known resistance genes in Argentinian germplasm. In order to identify loci conferring resistance to the local races of Pst for effective utilization in future breeding programs, a genome-wide association study (GWAS) was performed using a collection of 245 bread wheat lines genotyped with 90 K SNPs.

Results

To search for adult plant resistance (APR) the panel was evaluated for disease severity (DS) and area under disease progress curve (AUDPC) in field trials during two years under natural infection conditions. To look for seedling or all-stage resistance (ASR) the panel was evaluated to determine infection type (IT) under greenhouse conditions against two prevalent races in Argentina. The phenotypic data showed that the panel possessed enough genetic variability for searching for sources of resistance to Pst. Significant correlations between years were observed for Pst response in the field and high heritability values were found for DS (H2 = 0.89) and AUDPC (H2 = 0.93). Based on GWAS, eight markers associated with Pst resistance (FDR < 0.01) were identified, of these, five were associated with ASR (on chromosomes 1B, 2A, 3A and 5B) and three with APR (on chromosomes 3B and 7A). These markers explained between 2% and 32.62% of the phenotypic variation. Five of the markers corresponded with previously reported Yr genes/QTL, while the other three (QYr.Bce.1B.sd.1, QYr.Bce.3A.sd and QYr.Bce.3B.APR.2) might be novel resistance loci.

Conclusion

Our results revealed high genetic variation for resistance to Argentinian stripe rust races in the germplasm used here. It constitutes a very promising step towards the improvement of Pst resistance of bread wheat in Argentina. Also, the identification of new resistance loci would represent a substantial advance for diversifying the current set of resistance genes and to advance in the improvement of the durable resistance to the disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is an important crop for global food security that provides 20% of the daily calories and over 25% of the protein consumed by the human population [1]. In spite of the fact that more than 700 million tons of wheat are produced every year in the world, further production increases are required to satisfy the future demand for food [2]. Argentina is among the countries with the capacity to fulfill part of that demand [1]. This country has the potential to produce five times the grains required by its population [3], because of the Rolling Pampas, one of the most productive regions of the world [4]. However, wheat production faces several biotic and abiotic obstacles that usually cause major economic losses in terms of yield and quality. Currently, estimates of potential yield losses for the wheat crop attributed to pathogens are estimated to be around 21.5% [5]. Among the main diseases described in wheat, rusts take a preponderant place, as they are widespread in all wheat regions and are highly destructive [6].

Stripe (yellow) rust, caused by the biotrophic fungus Puccinia striiformis Westend. f. sp. tritici Erikss (Pst) is one of the most devastating diseases of the wheat crop worldwide [7,8,9]. Stripe rust causes significant reductions in both yield and grain quality. Yield losses can range from 10 to 70% depending on the susceptibility of the cultivar, timing of initial infection, rate of disease development, and duration of disease [10]. However, Pst can cause 100% of yield losses in highly susceptible genotypes if infection occurs very early and the disease continues developing during the entire growing season [10, 11].

Historically, Pst epidemics have occurred mainly in temperate areas with cool and wet weather conditions [12]. Until a few years ago, stripe rust was considered a sporadic disease in Argentina. In fact, it used to occur in the Southern wheat region only when temperatures during spring were lower than normal and under high humidity conditions. However, since 2015 both the incidence and severity of this disease have been increasing [13], and in 2017, the disease reached an epiphytic level in the Argentine wheat region [14, 15]. The basis of this abrupt change seems to be the wide spread of susceptible cultivars and the emergence of new races that have expanded their virulence profiles, capable of adapting to warmer temperatures, and with higher aggressiveness than the previously characterized races [15]. These races overcame many of the major resistance genes in germplasm adapted to Argentina [16, 17].

Although some fungicides are effective for the control of stripe rust, the chemical application adds considerable cost to crop production and poses potential environmental risks. For this reason, the use of genetic resistance represents the most effective, economic, and ecological strategy to reduce losses due to this disease [18]. Genetic resistance to stripe rust can be broadly categorized as either race-specific or non-race-specific [18, 19]. The former is often referred to as seedling resistance or all-stage resistance (ASR) because it can be detected at the seedling stage but remains effective at all stages of plant growth. This kind of resistance generally results in a strong hypersensitive response associated with high levels of resistance. It is frequently conferred by single genes or combinations of a few genes and is characterized by being specific to the race of the pathogen [19]. In contrast, non-race-specific resistance, also called adult plant resistance (APR), is expressed at later stages of plant growth through low disease severities at the adult-plant stage in the field [19]. This type of resistance is polygenic and governed by the additive effects of several low-effect genes [20]. These genes are effective against all Pst races and are characterized by various degrees of resistance (partial or quantitative resistance) [18, 21,22,23].

Due to the high level of resistance and the easy incorporation of single genes into commercial cultivars, ASR has been more attractive to breeding programs in the past [24]. However, this type of resistance is readily broken by new virulent races; hence, it has a relatively limited effective life [25,26,27]. Contrarily, APR has the advantage of providing more durable resistance [21, 28]. However, cultivars with this type of resistance can suffer significant yield losses when rust starts developing early in the growing season and environmental conditions continue to be favorable for the expression of the disease [7]. This situation has forced wheat breeders to focus on pyramiding strategies that combine multiple race-specific and non-race-specific resistance genes. This approach provides a complex resistance against the dynamics of pathogen virulence and increases the durability of the deployed resistance [29, 30].

According to the Catalogue of Gene Symbols for Wheat [31] and the 2020 Supplement (https://wheat.pw.usda.gov/GG3/wgc) there are currently 83 officially designated Yr genes for resistance to stripe rust and 42 temporarily designated genes. Many of these genes have been introduced into wheat varieties from wheat relatives and exotic species. However, most of them are already ineffective against the new Pst races that appeared in the last years [14, 15]. Besides, numerous quantitative trait loci (QTL) studies have been carried out identifying > 350 QTL so far [32]. Nevertheless, most of the previous research studies, were based on classical mapping methods that are costly, characterized by low resolution in QTL detection, and restrict the number of alleles sampled per locus in each population hindering the examination of the full range of genetic diversity available in the crop [33, 34]. In this way, considering that Pst constitutes a great threat in the Argentine wheat region, the identification and characterization of new sources of resistance to the local races have become essential to improve durable resistance to this disease.

Currently, the possibility of obtaining resistance gene combinations is being increasingly facilitated by the recent advances in genomics, statistics, and efficient mechanisms of genome manipulation [35]. Using efficient methods of genetic analysis to facilitate the identification and pyramiding of genomic regions associated with traits of agronomic importance in diverse germplasm accessions is an aim for the effective use of diversity in crop breeding programs. Genome-wide association study (GWAS) constitutes a widely used approach to detect quantitative trait loci (QTL) in plants, as they combine phenotypic and genotypic data from a large number of individuals [36]. This tool can examine a relatively wide portion of natural variation in a species and detect trait associations to much smaller genomic regions because the sampled diversity includes many more recombination events than those observed in traditional recombinant inbred line or doubled haploid populations [37]. GWAS has been used in QTL mapping for diverse traits in numerous plant species [38, 39]. In wheat, GWAS has been successfully used for agronomic traits [40, 41], quality [42], and disease resistance [43, 44], among others. Therefore, GWAS represents a highly advantageous alternative for the identification and characterization of new sources of durable resistance to Pst.

In order to advance in the genetic improvement of the resistance to stripe rust, the objectives of this study were to: (1) characterize the diversity of the resistance to local races of stripe rust of Argentina in a wide collection of spring bread wheat genotypes, (2) to conduct a genome-wide search for single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with resistance to current races of Pst from Argentina and (3) to compare the Pst resistance loci identified in this work with previously identified Yr genes and QTs.

Results

Evaluation of wheat germplasm

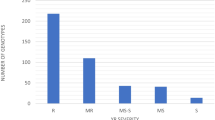

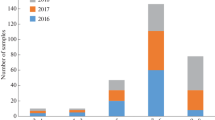

Wheat germplasm responses (ITs) to two Pst races of stripe rust pathogen at seedling stage and the DS and AUDPC data of the adult-plant stage evaluated in the field during the two years are summarized in Table 1. The mapping population showed diverse responses to stripe rust and continuous variation was observed for all the variables across the conducted experiments (Fig. 1). At the seedling stage, broad phenotypic variation was exhibited among the 245 genotypes evaluated for each race (P < 2.16 × 10–16) (Table S1). Based on the IT data, for Yr19-71, 17.2% of the accessions displayed high resistance reactions (IT = 0–4), while 67.2% of the accessions were considered susceptible (IT = 7–9). The remaining 15.6% of the accessions showed an intermediate reaction (IT = 5–6). On the other hand, for Yr20-161, 19.3% of the accessions exhibited a resistant response, 75% of the accessions were highly susceptible and 5.7% of the genotypes displayed an intermediate reaction (Fig. 1).

Frequency distribution of the response to stripe rust in the collection of 245 spring bread wheat genotypes evaluated for seedling resistance -infection type (IT) for the races a Yr19-71 and b Yr20-161- and field-based resistance -c disease severity (DS) and d area under disease progress curve (AUDPC)-

In the APR screening, sequential restricted maximum likelihood ratio tests revealed highly significant variation due to genotypes (P < 0.0001) (Table S2). Across the years, DS ranged from 0.05 to 1 across the panel, with an average of 0.27. The AUDPC ranged from 2 to 926.25 with an average of 156.31. Variance component analysis by restricted maximum likelihood (REML) showed that σ2g was greater than σ2ge for both variables. High broad-sense heritability values were observed for DS (H2 = 0.89) and AUDPC (H2 = 0.93) indicating that a high portion of the observed phenotypic variation was caused by the genotypic component (Table S3).

Based on the population structure analysis performed in this population by Zhang et al. [45] (Fig S1), a significant correlation (P < 0.001 and r ranging from 0.19 to 0.34) was observed between the population sub-clusters and the response to stripe rust resistance (Fig. 2) Besides, LSD test showed significant differences among the subpopulations, justifying the use of the population structure in the panel in the GWAS model.

Effect of population structure on the response to stripe rust in the collection of 245 spring bread wheat genotypes: a Infection type (IT) for the race Yr19-71, b IT for the race Yr20-161, c Disease Severity (DS), and d Area Under Disease Progress Curve (AUDPC). Box plots show trait distribution and compare the levels of stripe rust among the four subpopulations. Boxes indicate the middle 50% of the data and the median (solid horizontal line). The whiskers show the range of adjacent values; dots indicate outliers. The subpopulation represented by the same lowercase letter(s) are not significantly different at p = 0.01

Marker-trait association and annotation

Seedling stage resistance

A total of five SNPs (at false discovery rate -FDR- adjusted P < 0.01) were significantly associated with the two races and were located on chromosomes 1B, 2A, 3A, and 5B (Table 2, Fig. 3a). The percentage of phenotypic variation (R2) for IT to Yr19-71 explained by the significant marker, Tdurum_contig11004_688, located on chromosome 1B, was 32.6%, while the R2 for IT to Yr20-161 ranged from 2% for wsnp_Ex_c33932_42333941 on 5B to 16.5% for Tdurum_contig44861_581 on 1B. The resistance alleles of the genomic regions showed allelic effects of reducing IT by 5.1 for Yr19-71 and from 0.8 to 4.7 for Yr20-161 (Fig. 4a and b). QQ-plots for IT to Yr19-71 (Figure S1a) and Yr20-161 (Figure S1b) reflected that the distribution of observed associations (P-values) was close to the distribution of the expected associations on the lower left section of the graph. SNPs on the upper right section, deviating from the diagonal, are most likely associated with these traits.

Circle Manhattan plots for stripe rust resistance in the collection of 245 spring bread wheat genotypes evaluated for a Seedling resistance (inside: infection type -IT- for the race Yr19-71; outside: IT for Yr20-161) and b Field-based resistance (inside: disease severity –DS-; outside: area under disease progress curve -AUDPC-). SNPs associated with stripe rust resistance are marked with red stars

Allelic effects of the highly significant SNP markers on a BLUP-values of disease severity –DS- b BLUP-values of the Area Under Disease Progress Curve -AUDPC- c infection type -IT- for the race Yr19-71 and d IT for Yr20-161. Left: Favorable (resistance-associated) allele; Right: unfavorable allele. The marker allele represented by the same lowercase letter(s) are not significantly different at p = 0.01

Field-based resistance to stripe rust

A total of three SNPs, at FDR-adjusted P < 0.01, were associated with field-based resistance to stripe rust (Table 3, Fig. 3b), and they were located on chromosomes 3B and 7A. Of these, two SNPs were associated with DS, and all three were associated with AUDPC. Markers wsnp_Ku_c33335_42844594 -on chromosome 3B- and wsnp_Ex_c20062_29096408 -on 7A- were commonly detected for the two traits. The phenotypic variation (R2) explained by the SNPs for DS was 13.4% for wsnp_Ku_c33335_42844594 and 7.7% for wsnp_Ex_c20062_29096408; in turn, for AUDPC, R2 ranged from 7.8% for wsnp_Ex_c20062_29096408, to 14% for wsnp_Ku_c33335_42844594. The resistance alleles of the genomic regions showed allelic effects of reducing stripe rust responses ranging from 0.17 to 0.19 for best linear unbiased predictors (BLUP) of DS and 0.23 to 0.28 for BLUP of AUDPC (Fig. 4c and d). QQ-plots for DS (Figure S1c) and AUDPC (Figure S1d) reflected that the distribution of observed associations was close to the distribution of the expected associations on the lower left section of the graph and the SNPs on the upper right section of the graph, which deviate from the diagonal, are most likely associated with these traits.

Relationship between the number of favorable alleles and response to stripe rust

After ranking the accessions by increasing order based on the number of APR-associated favorable alleles, a comparison between the groups evidenced a decrease in the average trait values in line with the increase in the number of resistance alleles (Fig. 5). For DS, genotypes that combined the two favorable alleles significantly improved APR to stripe rust reducing the mean by 35% compared with the genotypes with no such alleles (P = 1.41 × 10–6). In the same way, for AUDPC, accessions with the three resistance alleles significantly reduced the mean by 553.12 compared with the genotypes without any favorable allele (P = 2.4 × 10–14).

Effect of the number of resistant alleles on a DS and b AUDPC. The numbers in abscissa indicate number of favorable alleles in each subset of genotypes. The error bars indicate the mean standard error of each subset of genotypes. The subsets of genotypes represented by the same lowercase letter(s) are not significantly different at p = 0.01

Comparison of Pst resistance QTL and Yr genes

In order to identify which of the SNP markers described in Tables 2 and 3 mapped to similar regions to those of previously identified Yr resistance genes and QTL, physical positions of these markers were compared with the physical location of the flanking markers for each previously reported QTL or Yr gene [22, 23, 33, 44], according to the reference sequence of the bread wheat genome (Ref Seq v2.1; IWGSC) [46, 47]. QTL confidence intervals were established based on ± the intermarker physical distance corresponding to the critical LD r2 [22, 44](Fig S2). Five SNP markers on chromosomes 1B, 2A, 3B, 5B and 7A were mapped in the same region of previously reported stripe rust resistance QTL and/or genes. Other two SNPs on chromosomes 3A and 3B were mapped far from any currently known Pst resistance gene identified in Triticum aestivum. The remaining marker on chromosome 1B was mapped to the same region of a previously reported QTL, but it was determined to be different from this QTL based on the phenotype. Hence, these last three genomic regions most likely tag new Pst resistance loci. Figures 6 and 7 show the comparisons between the genomic regions reported here and the previously identified resistance genes and QTL mapped in the same regions. Detailed description of Figs. 6 and 7 are summarized in Table S4.

Comparisons of the chromosome positions (in Mb, denoted with horizontal grey marks on vertical black bars) between the QTL identified in this study associated with seedling resistance to stripe rust (left bar per chromosome) and the reported Yr genes and QTL (right bar per chromosome). SNP markers identified in this GWAS are underlined. All positions are approximate, and thus should be treated as guidelines for future studies. The detailed information of the previously mapped Yr genes and QTL is presented in Supplementary Table 6

Comparisons of the chromosome positions (in Mb, denoted with horizontal grey marks on vertical black bars) between the QTL identified in this study associated with adult plant resistance to stripe rust (left bar per chromosome) and the reported Yr genes and QTL (right bar per chromosome). SNP markers identified in this GWAS are underlined. All positions are approximate, and thus should be treated as guidelines for future studies. The detailed information of the previously mapped Yr genes and QTL is presented in Supplementary Table 6

Discussion

Evolution of new races of stripe rust in bread wheat is a recurrent threat for successful production of this crop in many regions around the world, including Argentina. Recently, the emergence of the new racial groups of Pst, caused a breakdown of many of the major resistance genes in germplasm adapted in the country [15, 16]. Therefore, the identification of new sources of resistance and their introgression into adapted germplasm is a pressing need for accelerating durable stripe rust resistance breeding in bread wheat.

Response of spring wheat accessions to stripe rust

In this study, a large and diverse collection of spring wheat lines from several breeding programs was characterized for seedling resistance to two prevailing races of Pst in Argentina and field-based resistance during two years. Highly significant differences among the genotypes were found in both ASR and APR reflecting the effectiveness of the phenotyping strategy and the presence of a considerable genetic variation in the panel. Results from ASR evaluation showed that depending on the race, 15–17% of the genotypes were resistant while 67–75% displayed intermediate resistance and 8–10% were susceptible, indicating the presence of single major genes in the panel, which might include uncharacterized major Yr resistance genes.

On the other hand, among the 156 accessions that showed strong to moderate resistance in the field, with disease severity values < 0.2, 101 were resistant only at a post-seedling growth stage. This may indicate that the resistance in these genotypes is likely conferred by APR genes or QTL. The incorporation and deployment of these non-race-specific resistance genes is an important objective for wheat breeding programs because this kind of genes have historically provided more durable resistance than race-specific resistance genes [18, 30, 35].

The high degree of broad-sense heritability for DS and AUDPC (H2 = 0.89 and H2 = 0.93 respectively) indicates that the phenotypic variation in stripe rust resistance is stable and mainly explained by the genotypic variation. These values result favorable for the identification of significant associations in GWAS. Likewise, selection for highly resistant genotypes could be successful in future breeding programs. Similar broad-sense heritability values were reported in previous studies [22, 23].

Besides, highly significant differences were found between the years and genotype x year interaction indicating that the response of the genotypes differed in 2020 and 2021 (P < 0.0001). These statistically significant differences observed in the two years were most likely the result of variation in environmental variables (temperature and rainfall). In this situation, BLUP values were calculated to reduce the environmental impact and increase the reliability of the results. Nevertheless, a high degree of correlation was observed for Pst response between the two years (r = 0.82 for DS and r = 0.87 for AUDPC).

Population structure of the spring bread wheat accessions

The power of association mapping studies depends on levels of genetic variation, linkage disequilibrium, and population structure [48]. Many studies have shown that the lack of appropriate correction for population structure can lead to false-positive trait-marker associations [49,50,51,52]. In this way, identifying and taking into consideration population structure is important before conducting GWAS to avoid spurious associations.

Population structure of the 245 accessions from the spring bread wheat collection was investigated by Zhang et al. [45] and the analysis revealed the clustering of the panel into four subpopulations as most likely representative. The characterization of the subgroups was mainly reflected by the geographic origin of the genotypes. In the present study, the population structure of the collection was used as a covariate in the GWAS to reduce the likelihood of false-positive associations. Additionally, a significant correlation was observed between the population sub-clusters and the response to stripe rust resistance, justifying the use of the population structure in the model.

Significant associations in the GWAS

GWAS using high-quality SNP marker data and Pst assessments from field trials and greenhouse experiments provided valuable information for a comprehensive analysis of stripe rust resistance in the spring bread wheat collection. The recently developed BLINK method was used in the present study to explore single-marker associations. This last-generation GWAS algorithm, which implements a multiple loci test method by combining a fixed-effect model with Bayesian information criteria and uses linkage disequilibrium information, increases the statistical power while better controlling the false-positive rate [49]. QQ- plots reflected that the distribution of observed associations (P-values) was close to the distribution of the expected associations on the lower left section of the graph (Fig S1). This means the method implemented for GWAS was sufficiently stringent to control spurious associations.

A total of eight SNP markers were detected as being significantly associated with experiment-wise correction for multiple testing (FDR adjusted P < 0.01) in both seedling and field experiments. Analysis showed a significant effect due to pyramiding minor resistant alleles identified in this study. The accessions that harbored relatively few or none of the identified resistance-associated favorable alleles showed a comparatively high disease level. Similar to a previous report by Maccaferri et al. [22], Naruoka et al. [53], and Yao et al. [54], resistance to Pst was enhanced continuously with an increase in the number of favorable alleles, which revealed the additive effect of accumulation of alleles of field-based resistance QTL. This constitutes a promising result in the context of genetic improvement for durable resistance to Pst.

Alignment of QTL to the previously identified Yr genes/QTL

The IWGSC genome assembly (IWGSC RefSeq v2.1) was used to compare resistance loci detected in the current study with previously mapped Yr genes and QTL. SNP markers on two genomic regions were mapped far from any previously identified Yr gene. Other marker was mapped on the same region of a previously reported QTL, but different based on the phenotype. Thus, these three genomic regions could tag new Pst resistance loci. The remaining genomic regions were mapped close to known Yr genes and QTL. Relationship of the significant genomic regions with previously mapped Yr genes and QTL are discussed below.

Chromosome 1B

To date, numerous Pst genes have been identified on chromosome 1B including: Yr9 [55], Yr10 [56], Yr15 [57, 58], Yr24/Yr26, [56, 59] Yr29 [60], Yr64 [57] and Yr65 [57]. Likewise, several temporarily designated Yr genes have been mapped to 1B including: YrAlp [61], YrC142 [62], YrCHK [63], YrExp1 [61] and YrH52 [64] among others. Furthermore, many QTL associated with APR to stripe rust have been identified on this chromosome [44, 65, 66]. In this research, SNP Tdurum_contig11004_688 (QYr.Bce.1B.sd.2), identified on the short arm of chromosome 1B, was in association with the resistance to pathotype -Yr19-71.

Of the many Yr genes mapped to 1B, resistance gene Yr15 is located in the same region as SNP Tdurum_contig11004_688. Yr15 was discovered in the accession G25 of wild emmer wheat (Triticum turgidum ssp. dicoccoides), the tetraploid progenitor of hexaploid common wheat [67] and since then it has been introgressed into various tetraploid and hexaploid wheats. The Yr15 gene was recently cloned by Klymiuk et al. [58] and has been described as a putative protein kinase-pseudokinase named WTK1, conferring all-stage resistance against more than 3000 genetically diverse Pst races, including modern races, such as ‘Warrior’. Although certain Pst races were reported to be virulent on Yr15 [68], since 2003 there has not been informed virulence on Yr15 in the newly isolated Pst races [69]. In accordance with this, the seedling test demonstrated that Yr19-71 pathotype is avirulent on the Yr15 gene. We know that the Yr15 gene is present in some of the 245 spring bread wheat accessions of the collection used in this study. Therefore, it is likely that Tdurum_contig11004_688 represents the Yr15 gene.

Chromosome 2A

One genomic region (QYr.Bce.2A.sd) was identified on chromosome 2A in association with seedling resistance to Yr20-161 pathotype. SNP BobWhite_c4517_120 was found within the same chromosomal region where one temporarily designated gene YrJ22 [70] is located. YrJ22 is a dominant gene, identified in the Chinese wheat cultivar Jimai 22. For this gene we do not know the response to the Yr19-71 and Yr20-161 pathotypes since the source of YrJ22 has not been tested against the two races. Further analyses are required to confirm whether the resistance conferred by SNP BobWhite_c4517_120 is due to YrJ22.

Chromosome 3B

In the present study, CAP12_rep_c7064_56 (QYr.Bce.3B.APR.1) was found to be associated with adult plant resistance to Pst on chromosome 3B. Previous studies have reported that numerous Yr genes and stripe rust resistance QTL are present on this chromosome. In the proximal end of the short arm of chromosome 3B, four Yr genes are present: Yr4 [31], Yr57 [71], Yr30 [72] and the temporarily designated gene Yrns-B1 [31]. Besides, in that chromosomal region a cluster of stripe rust APR QTL have been mapped: QYr-3B_Alturas, a high-temperature adult-plant resistance QTL identified in the American spring bread wheat cultivar Alturas [73]; QYrco.wpg-3B.1_Brundage identified in the winter bread wheat cultivar Brundage [66]; QYr-3B_Oligoculm in the Israeli bread wheat Oligoculm [72]; QYr.cim‐3BS_Chapio in the spring bread wheat cultivar Chapio [74]; QYr-3B.1_Pavon in the spring bread wheat cultivar Pavon76 [75]; QYr.tam-3B_Quaiu in bread wheat cultivar Quaiu 3 [76]; Yr.cim-3BS.2_Francolin#1 identified in the cultivar Francolin#1 [77]; QYr.inra-3BS_Renan in cultivar Renan [78]; QYr.ucw-3B.2 identified in a worldwide collection of spring bread wheat [22]; QYr.caas-3BS in the Chinese winter wheat cultivar Zhong 892 [79] and QYr.sun-3B_Kukri, identified in the cultivar Kukri [80]. Marker CAP12_rep_c7064_56 in our study was mapped within the confidence interval of the QYr.sun-3B_Kukri. Therefore, it is likely that resistance conferred by CAP12_rep_c7064_56 is linked to the QTL QYr.sun-3B_Kukri identified by Bariana et al. [80].

Chromosome 5B

One genomic region (QYr.Bce.5B.sd) was identified on chromosome 5B in the same chromosomal region of the designated gene for resistance to stripe rust Yr47 [81]. Yr47 is a seeding resistance gene identified in Iranian common wheat landraces [81]. However, it is not known the response of Yr47 to the Yr19-71 and Yr20-161 pathotypes. As the source of Yr47 has not been tested against the two pathotypes used in this study, further analysis may be required for clarification.

Chromosome 7A

SNP wsnp_Ex_c20062_29096408 was found to be associated with APR to Pst (both DS and AUDPC) on chromosome 7A (QYr.Bce.7A.APR). In this chromosomal region two QTL: QYr.sun-7A identified in the synthetic hexaploid CPI133872 [82] and QYr.caas-7A_Jingshuan 16 mapped in the Chinese wheat cultivar Jingshuan 16 [83] have been reported. QYr.sun-7A and QYr.caas-7A_Jingshuan.16, which were mapped close to wsnp_Ex_c20062_29096408, were reported as minor APR QTL; therefore, it is likely that the marker identified in this study is linked to these QTL. The identity or similarity of the genomic region tagged by wsnp_Ex_c20062_29096408 with previously mapped QTL needs to be further investigated.

Novel potential genomic regions identified in this study and their significance

Three genomic regions identified in this study might be tagging novel genomic regions. Two of these regions on chromosomes 3A (QYr.Bce.3A.sd) and 3B (QYr.Bce.3B.APR.2) were mapped where no Pst genes or QTL have been previously reported. The third region (QYr.Bce.1B.sd.1) was in the same location of a previously reported QTL, but was determined to be different from this QTL based on the phenotype.

SNP Tdurum_contig44861_581 (QYr.Bce.1B.sd.1) was mapped in the proximal end of the short arm of chromosome 1B between two previously reported genes: Yr10 [84] and YrAlp [61]. Yr10 gene was mapped in association with the Xpsp3000 marker at 5.15 Mb, whereas Tdurum_contig44861_581 detected in this study is located at 28 Mb. Likewise YrAlp was associated with the Xwgp47 marker at 58.7 Mb. On the other hand, SNP Tdurum_contig44861_581 overlapped with the previously reported QTL QYr.cau-1BS [82]. However, the marker identified in this study confers seedling resistance of low IT, and QYr.cau-1BS is not associated with the seedling resistance (exhibits high/susceptible IT), but it is associated with the adult plant resistance (latent period). These findings indicate that QYr.Bce.1B.sd.1 could be a novel Pst resistance gene.

One genomic region (QYr.Bce.3A.sd) was identified on chromosome 3A in association with seedling resistance to the Yr20-161 race. Stripe rust seedling resistance SNP Excalibur_rep_c103091_266 was identified in the short arm of chromosome 3A where two previously reported Yr genes were mapped: Yr76 gene, identified in the winter club wheat cultivar Tyee [85] and YrHu [86] identified in Psathyrostachys huashanica, a related species to Triticum aestivum. Nevertheless, QYr.Bce.3A.sd did not map within the confidence interval of these genes. Hence QYr.Bce.3A.sd might be a new stripe rust resistance gene.

The marker wsnp_Ku_c33335_42844594, designated as QYr.Bce.3B.APR.2, was found in association with seedling resistance against the Yr20-161 pathotype in the short arm of chromosome 3B. Four Yr resistance genes Yr4 [31], Yr57 [31], Yr30 [72] and Yrns-B1 [31] are reported on this region. However, according to the reference sequence -Ref Seq v2.1- of the IWGSC, wsnp_Ku_c33335_42844594 is outside the genomic region of any of these reported genes. While the marker identified here is mapped at 71.87 Mb, Yr4, Yr57, Yr30 and Yrns-B1 are located at 4.9, 4.94, 6.7 and 17.6 Mb respectively. Thus, based on its physical position, QYr.Bce.3B.APR.2 could be representing a potential new source for resistance to stripe rust.

The results presented here, give an overview of the relationships between the loci identified in this study and the previously identified Pst resistance genes and QTL. Nevertheless, these results should be considered with prudence because of the intrinsic limitations of published maps, which can result in distorted distances in some region of the map. Besides, the low resolution of the original maps of Pst genes and the extended LD in wheat make the comparisons are difficult. In this way, the relationships described in this section should be considered as tentative.

Conclusion

The results of the present study highlight the possibility of exploiting the high genetic diversity in wheat germplasm collections to identify genomic regions associated with the resistance to stripe rust. The collection of spring bread wheat exhibited a wide range of phenotypic variation for both field-based and seedling resistance to stripe rust. Genotypes with a higher percentage of alleles associated with the stripe rust resistance constitute valuable genetic resources that could be used as parents in Argentine breeding programs to improve stripe rust resistance. In the present study, we identified eight QTL associated with the resistance to stripe rust; three of them could be probably novel. The markers linked to QTL identified in the current research result of substantial value for marker-assisted selection in wheat breeding programs. These genomic regions constitute the initial step to search for their candidate genes, which will allow their better manipulation in the future

Methods

Plant material

A collection of 245 spring bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes, already described in Zhang et al. [45] and well adapted to Argentinian environments, was used in this study. Briefly, the panel from several breeding programs, included 69 genotypes from CIMMYT (CMT), 12 from South Dakota State University (SDK), 42 from the University of California, Davis (UCD), 26 from the University of Idaho (UIA), 19 from the University of Minnesota (UMN), 15 from Washington State University (WAS), and 62 from various locations (other US programs and 14 other countries, Table S5).

As described by Zhang et al. [45], genotyping was carried out at the USDA-ARS genotyping laboratory, Fargo, ND using the Infinium wheat SNP 90 K iSelect assay (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) developed by the International Wheat SNP Consortium [85]. After removing those SNPs with very low minor allele frequency (MAF) < 3% and/or > 10% missing values, a total of 22,226 high-quality SNP markers were used for the GWAS.

Population structure was investigated by Zhang et al. [45] using STRUCTURE 2.3.4 [48] and principal component analysis (PCA) with the R package ade4 (Fig. S1) [87]. In short, four subpopulations were determined as most likely representative of the population structure, and the corresponding Q-matrices (4 × 245) of population membership coefficients were obtained (Table S5). The extent of linkage disequilibrium (LD) in this association panel was calculated by Zhang et al. [45], based on pairwise LD squared correlation coefficients (r2) for all intra-chromosomal SNP loci. The scatter plot of r2 versus physical distance was fitted using a nonlinear model described by Remington et al. [88] in R [89] with the function nls (nonlinear least squares method). The physical distance at which LD fell below the r2 thresholds -determined by Zhang, et al. [45]- was used to define the confidence intervals of the QTL detected in this study.

Additionally, a group of 24 genotypes was used in this work as differential testers of pathogenic variability of Pst (Table S6). The group included a set of 19 near-isogenic lines (NILs) developed by Dr. Wellings from Sydney University, three genotypes carrying specific gene or gene combinations kindly provided by CIMMYT, Mexico, and two European cultivars. The NILs are based on the Australian cultivar Avocet (of a high degree of susceptibility to Pst) and represent a set of wheat lines that are similar except for the presence of single genes for resistance. Furthermore, two Argentinian cultivars were included as checks in the experiments: Don Mario Algarrobo (universally susceptible to Pst) and Baguette 750 (susceptible to races of Pst with a higher virulence spectrum).

Finally, three highly susceptible local cultivars to the main races of Pst detected in the wheat region: Buck Claraz, SN 90, and Klein Lanza, were included as checks in the field experiments. These cultivars were chosen for presenting average severity values above 0.7 in the wheat region during the last years.

Phenotypic trait evaluation

Seedling resistance screening

Seedling resistance to stripe rust was characterized under controlled conditions in a greenhouse at the INTA Bordenave Experimental Station (37°45′45’’ S; 63°05′28’’ W; 205 m.a.s.l.), Buenos Aires province, Argentina. Races Yr19-71 and Yr20-161, representing the most prevalent races of the most frequent genetic groups of Pst in Argentina were used [90, 91]. Ten seeds of each genotype of the population were grown in plastic pots filled with a potting medium. When the two first leaves were fully expanded, the seedlings were inoculated by spraying the Yr19-71 / Yr20-161 urediniospores suspended in mineral oil (Soltrol 170) using an atomizer. Inoculated seedlings were sprayed with a fine mist of sterile water and incubated at 8 °C for 18 h in a dew chamber with relative humidity close to 100%. Then, seedlings were transferred to a greenhouse with a mean temperature of 16 ± 2 °C. Infection type (IT) was recorded for each seedling 15 days after inoculation based on a 0–9 scale [92]. Lines of the stripe rust differential set were also characterized for IT response to these two races in order to obtain the virulence/avirulence formulae of the races (Table S7).

Field-based resistance screening

Adult plants of the 245 genotypes were evaluated for response to Pst natural infection in field experiments at the INTA Balcarce Experimental Station (37°46′01’’ S; 58°18′29’’ W; 118 m.a.s.l.), Buenos Aires province, Argentina in two crop seasons (2020 and 2021). Sowing dates were August 4th in 2020 and August 6th in 2021. In the two field experiments, a non-replicated augmented design with eight blocks was used. Plots consisted of a single 1 m-long row with 30 cm between rows. Sowing density was adjusted to 350 plants m2. The susceptible checks Buck Claraz, SN 90, and Klein Lanza, were replicated twice in each block. The same checks also were planted as spreader rows bordering the trials to provide uniform stripe rust infection across the plots. Experiments were rainfed and conducted under optimal nutritional conditions.

Disease assessment started when most flag leaves of the susceptible checks displayed a disease severity of at least 50% and continued at least four times at 4-day intervals. Disease severity (DS) was visually assessed, based on the percentage of leaf area covered with uredinia, according to the modified Cobb’s scale [93]. After the last DS score when the disease progress ended, the area under the disease progress curve (AUDPC) was calculated according to the method used by Wilcoxon et al. [94].

Statistical analyses of the phenotypic data

Statistical analyses were performed using R software [89]. The IT data were analyzed by fitting linear models with the lm function. The statistical model used was:

where \({y}_{ij}\) is the response variable of genotype “i” on repetition “j”, \(\mu\) is the mean value of the response variable of genotype “i”, and \({\varepsilon }_{ij}\) is the random error of the observation of genotype “i” on repetition “j”.

Assumptions on this model are: \({y}_{ij }\sim N\left(\mu ; {\sigma }_{e}^{2}\right)\) and \({\varepsilon }_{ij }\sim N\left(0; {\sigma }_{e}^{2}\right)\). ANOVA was performed to determine the significance of the effects of genotypes.

DS and AUDPC data were analyzed by fitting linear mixed models with the lme function from package nlme [95]. Models were fitted considering years and blocks as fixed factors and genotypes and genotype x year interaction as random factors. The statistical model used was:

where \({y}_{ijk}\) is the response variable of genotype “i” on block “k” in the year “j”, \(\mu\) is the mean value of the response variable,\({\alpha }_{j}\) is the fixed effect of the year “j”, \({\beta }_{k\left(j\right)}\) is the fixed effect of the block “k” in the year “j”, \({\tau }_{i}\) is the random effect of genotype “i”, \({\gamma }_{j\left(i\right)}\) is the random interaction effect between genotype “i” and year “j”, and \({\varepsilon }_{ijk\left(s\right)}\) is the random error of the observation of genotype “i” on repetition “k” in the year “j”.

Assumptions on this model are: \({\alpha }_{j}\sim N\left(0; {\sigma }_{g}^{2}\right), { \beta }_{k\left(j\right)}\sim N\left(0; {\sigma }_{g}^{2}\right), {\tau }_{i} \sim N\left(0; {\sigma }_{g}^{2}\right)\), \({\gamma }_{j\left(i\right)}\sim N\left(0; {\sigma }_{ge}^{2}\right)\) and \({\varepsilon }_{ijk}\sim N\left(0; {\sigma }_{res}^{2}\right),\) all are independent of each other.

Sequential restricted maximum likelihood ratio tests were performed to determine the significance of the random effects of genotypes and genotype by year interactions. Best linear unbiased predictors (BLUPs) were obtained for all the genotypes. Variance components for genotypes, years, and genotype by year interactions were estimated using the Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) method [96]. Broad-sense heritabilities (H2) were estimated from variance components according to Hallauer et al. [97]. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated between the subpopulations and response to stripe rust resistance. Least significant differences (LSD) test was performed among the subpopulation according to the response to stripe rust resistance.

Association analysis

To identify loci associated with responses to stripe rust, GWAS was performed using 22,226 informative SNPs in the set of 245 genotypes. Association analyses were implemented in GAPIT 3 (Genomic Association and Prediction Integrated Tool v3) (Gapit 2021; [98]) in R software [89]. Association analyses were performed using Bayesian- information and linkage-disequilibrium iteratively nested keyway -BLINK, [99]-. The population structure was used as covariate to control for spurious associations. The quantile–quantile (QQ) plot is a useful tool for assessing how well the model used in GWAS accounts for population structure. The majority of the points in the QQ-plot should lie on the diagonal line. Deviations from this line suggest the presence of spurious associations due to population structure and familial relatedness. It is expected that the SNPs on the upper right section of the graph deviate from the diagonal and these SNPs are most likely associated with the trait under study [98].

In order to minimize the chance of false-positive marker-trait associations, significant association loci were considered at genome-wide adjusted P < 0.01 based on the False Discovery Rate (FDR) multiple correction method [100]. Linear models were performed to assess the amount of phenotypic variation explained by the significant markers. The markers were used as the independent variable and BLUP of DS and AUDPC and IT values were included as the response variable. Circular Manhattan plots were generated by GAPIT 3 using R packages gplot and scatterplot3d. Names assigned to the QTL identified in this study start with the prefix “Q” for QTL, followed by “Yr” for yellow rust, “Bce” for Balcarce, chromosome name and “sd” for seedling trait or “APR” for adult plant resistance trait.

To assess the pyramiding effect of resistant alleles of QTL for APR identified in this study, the genotypes were classified into groups containing different numbers of resistant alleles. Differences between DS and AUDPC of these groups were compared using the Least Significant Differences (LSD) Test.

Comparison of Pst resistance QTL and Yr genes

In order to determine whether the significant SNPs detected in this study were located in the same position as that of previously reported Yr genes and resistance QTL, the physical locations of the genomic regions were compared. The physical positions were determined according to the reference sequence -Ref Seq v2.1- of the International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium (IWGSC) [46]. For the segments of the chromosomes containing the genomic regions detected in this research, previously reported Yr genes and resistance QTL were integrated in a map including different marker types. Genomic regions were drawn with chromoMap in R [101] Information of these Yr genes and QTL are presented in Table S4.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- APR:

-

Adult plant resistance

- ASR:

-

All-stage resistance

- AUDPC:

-

Area under disease progress curve

- BLINK:

-

Bayesian- information and linkage-disequilibrium iteratively nested keyway

- BLUPs:

-

Best linear unbiased predictors

- DS:

-

Disease severity

- FDR:

-

False Discovery Rate

- GWAS:

-

Genome-wide association study

- H2 :

-

Broad-sense heritability

- IT:

-

Infection type

- IWGSC:

-

International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium

- LD:

-

Linkage disequilibrium

- LSD:

-

Least Significant Differences

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- Pst :

-

Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici

- QTL:

-

Quantitative Trait locus

- REML:

-

Restricted maximum likelihood ratio

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- Yr :

-

Yellow rust

References

FAO. Crops prospect and food situation. 2021. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/.

CIMMYT. Nutrition, health and food security Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maiz y Trigo. 2021. https://www.cimmyt.org/news/nutrition-health-food-security/.

Aramburu Merlos F, Monzon JP, Mercau JL, Taboada M, Andrade FH, Hall AJ, et al. Potential for crop production increase in Argentina through closure of existing yield gaps. Field Crops Res. 2015;184:145–54.

Hall AJ, Rebella CM, Ghersa CM, Culot JP. Field-crop systems of the Pampas. Ecosyst World. 1992;18:413–50.

Savary S, Willocquet L, Pethybridge SJ, Esker P, McRoberts N, Nelson A. The global burden of pathogens and pests on major food crops. Nat Ecol Evol. 2019;3:430.

Simón MR, Börner A, Struik PC. Fungal wheat diseases: etiology, breeding, and integrated management. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:498.

Chen W, Wellings C, Chen X, Kang Z, Liu T. Wheat stripe (yellow) rust caused by Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici. Mol Plant Pathol. 2014;15:433–46.

Wellings CR. Global status of stripe rust: a review of historical and current threats. Euphytica. 2011;179:129–41.

Tehseen M, Tonk F, Tosun M, Randhawa H, Kurtulus E, Ozseven I, et al. QTL mapping of adult plant resistance to stripe rust in a doubled haploid wheat population. Front Genet. 2022;13:900558.

Chen X. Epidemiology and control of stripe rust [Puccinia striiformis f. sp tritici] on wheat. Can J Plant Pathol. 2005;27:314–37.

Chen X, Kang Z. Introduction: history of research, symptoms, taxonomy of the pathogen, host range, distribution, and impact of stripe rust. In: Chen X, Kang Z, editors. Stripe rust. Dordrecht: Springer; 2017. p. 1–33.

Stubbs R. Stripe rust. In: Roelfs AP, Bushnell WR, editors. Cereal rusts. Vol. II. Disease, distribution, epidemiology, and control. New York: Academic Press; 1985. p. 61–101.

Campos P, Formento N, Couretot L, Alberione E. Aparición epifítica de roya amarilla del trigo en la región pampeana argentina. 2016.

Carmona M, Sautua F. Epidemias de roya amarilla del trigo. nuevas razas en el mundo, monitoreo y decisión de uso de fungicidas. Agr Amb. 2018;38:37–58.

Campos P. Estado de Situación de las royas de trigo en Argentina. Campaña 2019. 2020. https://inta.gob.ar/sites/default/files/inta_royastrigo19_act20_campos.pdf.

Hubbard A, Lewis CM, Yoshida K, Ramirez-Gonzalez RH, de Vallavieille-Pope C, Thomas J, et al. Field pathogenomics reveals the emergence of a diverse wheat yellow rust population. Genome Biol. 2015;16:1–15.

Losert D, Maurer HP, Leiser WL, Würschum T. Defeating the Warrior: genetic architecture of triticale resistance against a novel aggressive yellow rust race. Theor Appl Genet. 2017;130:685–96.

Chen X. High-temperature adult-plant resistance, key for sustainable control of stripe rust. 2013. p. 608–27.

Chen X, Line R. Gene number and heritability of wheat cultivars with durable, high-temperature, adult-plant (HTAP) resistance and interaction of HTAP and race-specific seedling resistance to Puccinia striiformis. Phytopathology (USA). 1995;85:573–8.

Singh RP, Huerta-Espino J, William HM. Genetics and breeding for durable resistance to leaf and stripe rusts in wheat. Turk J Agric For. 2005;29:121–7.

Lagudah ES. Molecular genetics of race non-specific rust resistance in wheat. Euphytica. 2011;179:81–91.

Maccaferri M, Zhang J, Bulli P, Abate Z, Chao S, Cantu D, et al. A genome-wide association study of resistance to stripe rust (Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici) in a worldwide collection of hexaploid spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). G3. 2015;5:449–65.

Muleta KT, Chen X, Pumphrey M. Genome-wide mapping of resistance to stripe rust caused by Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici in hexaploid winter wheat. Crop Sci. 2020;60:115–31.

Chen X. Challenges and solutions for stripe rust control in the United States. Aust J Agric Res. 2007;58:648–55.

Wellings C. A new pathotype of wheat stripe rust with implications for the VPM resistance. The University of Sydney. Plant Breeding Institute, Cereal rust report (season 2006). 2007;4:1–2.

Wellings C. Global status of stripe rust. BGRI 2010 technical workshop oral presentations Full papers and abstracts May 30–31, 2010. St Petersburg: Borlaug Global Rust Initiative (BGRI); 2010. p. 34–48.

Chen X, Penman L, Wan A, Cheng P. Virulence races of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici in 2006 and 2007 and development of wheat stripe rust and distributions, dynamics, and evolutionary relationships of races from 2000 to 2007 in the United States. Can J Plant Pathol. 2010;32:315–33.

Singh R, Huerta-Espino J, Bhavani S, Herrera-Foessel S, Singh D, Singh P, et al. Race non-specific resistance to rust diseases in CIMMYT spring wheats. Euphytica. 2011;179:175–86.

Hou L, Chen X, Wang M, See DR, Chao S, Bulli P, et al. Mapping a large number of QTL for durable resistance to stripe rust in winter wheat Druchamp using SSR and SNP markers. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126794.

Nelson R, Wiesner-Hanks T, Wisser R, Balint-Kurti P. Navigating complexity to breed disease-resistant crops. Nat Rev Genet. 2018;19:21.

McIntosh R, Yamazaki Y, Dubcovsky J, Rogers J, Morris C, Appels R, et al. Catalogue of gene symbols for wheat in 12th international wheat genetics symposium. 2013.

Jan I, Saripalli G, Kumar K, Kumar A, Singh R, Batra R, et al. Meta-QTLs and candidate genes for stripe rust resistance in wheat. Sci Rep. 2021;11:1–13.

Bulli P, Zhang J, Chao S, Chen X, Pumphrey M. Genetic architecture of resistance to stripe rust in a global winter wheat germplasm collection. G3. 2016;6:2237–53.

Flint-Garcia SA, Thornsberry JM, Buckler ES IV. Structure of linkage disequilibrium in plants. 2003. p. 1–33.

Liu L, Yuan C, Wang M, See D, Zemetra R, Chen X. QTL analysis of durable stripe rust resistance in the North American winter wheat cultivar Skiles. Theor Appl Genet. 2019;132:1677–91.

Huang X, Han B. Natural variations and genome-wide association studies in crop plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2014;65:531–51.

Nordborg M, Weigel D. Next-generation genetics in plants. Nature. 2008;456:720–3.

Wang M, Jiang N, Jia T, Leach L, Cockram J, Waugh R, et al. Genome-wide association mapping of agronomic and morphologic traits in highly structured populations of barley cultivars. Theor Appl Genet. 2012;124:233–46.

Jia G, Huang X, Zhi H, Zhao Y, Zhao Q, Li W, et al. A haplotype map of genomic variations and genome-wide association studies of agronomic traits in foxtail millet (Setaria italica). Nat Genet. 2013;45:957–61.

Dodig D, Zoric M, Kobiljski B, Savic J, Kandic V, Quarrie S, et al. Genetic and association mapping study of wheat agronomic traits under contrasting water regimes. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:6167–88.

Luján Basile SM, Ramírez IA, Crescente JM, Conde MB, Demichelis M, Abbate P, et al. Haplotype block analysis of an Argentinean hexaploid wheat collection and GWAS for yield components and adaptation. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19:1–16.

Reif JC, Gowda M, Maurer HP, Longin C, Korzun V, Ebmeyer E, et al. Association mapping for quality traits in soft winter wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2011;122:961–70.

Letta T, Maccaferri M, Badebo A, Ammar K, Ricci A, Crossa J, et al. Searching for novel sources of field resistance to Ug99 and Ethiopian stem rust races in durum wheat via association mapping. Theor Appl Genet. 2013;126:1237–56.

Yao F, Zhang X, Ye X, Li J, Long L, Yu C, et al. Characterization of molecular diversity and genome-wide association study of stripe rust resistance at the adult plant stage in Northern Chinese wheat landraces. BMC Genet. 2019;20:1–16.

Zhang J, Gizaw SA, Bossolini E, Hegarty J, Howell T, Carter AH, et al. Identification and validation of QTL for grain yield and plant water status under contrasting water treatments in fall-sown spring wheats. Theor Appl Genet. 2018;131:1741–59.

International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium, Appels R, Eversole K, Stein N, Feuillet C, Keller B, et al. Shifting the limits in wheat research and breeding using a fully annotated reference genome. Science. 2018;361:eaar7191.

Zhu T, Wang L, Rimbert H, Rodriguez JC, Deal KR, De Oliveira R, et al. Optical maps refine the bread wheat Triticum aestivum cv. Chinese Spring genome assembly. Plant J. 2021;107:303–14.

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–59.

Yu J, Pressoir G, Briggs WH, Vroh Bi I, Yamasaki M, Doebley JF, et al. A unified mixed-model method for association mapping that accounts for multiple levels of relatedness. Nat Genet. 2006;38:203–8.

Visioni A, Gyawali S, Selvakumar R, Gangwar OP, Shekhawat PS, Bhardwaj SC, et al. Genome wide association mapping of seedling and adult plant resistance to barley stripe rust (Puccinia striiformis f. sp. hordei) in India. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:520.

Zhu C, Gore M, Buckler ES, Yu J. Status and prospects of association mapping in plants. Plant Genome. 2008;1:5–20.

Gyawali S, Otte ML, Chao S, Jilal A, Jacob DL, Amezrou R, et al. Genome wide association studies (GWAS) of element contents in grain with a special focus on zinc and iron in a world collection of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). J Cereal Sci. 2017;77:266–74.

Naruoka Y, Garland-Campbell K, Carter A. Genome-wide association mapping for stripe rust (Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici) in US Pacific Northwest winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2015;128:1083–101.

Yao W, Liu Z, Fan Y, Shen X, Chao K, Hou L, et al. Inheritance and molecular markers for yellow rust resistant gene(s) in wheat cultivar Tianxuan43. Acta Phytopathology. 2015;45:48–56.

Lukaszewski AJ. Manipulation of the 1RS. 1BL translocation in wheat by induced homoeologous recombination. Crop Sci. 2000;40:216–25.

Ma J, Zhou R, Dong Y, Wang L, Wang X, Jia J. Molecular mapping and detection of the yellow rust resistance gene Yr26 in wheat transferred from Triticum turgidum L using microsatellite markers. Euphytica. 2001;120:219–26.

Cheng P, Xu L, Wang M, See D, Chen X. Molecular mapping of genes Yr64 and Yr65 for stripe rust resistance in hexaploid derivatives of durum wheat accessions PI 331260 and PI 480016. Theor Appl Genet. 2014;127:2267–77.

Klymiuk V, Yaniv E, Huang L, Raats D, Fatiukha A, Chen S, et al. Cloning of the wheat Yr15 resistance gene sheds light on the plant tandem kinase-pseudokinase family. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1–12.

Zhang X, Han D, Zeng Q, Duan Y, Yuan F, Shi J, et al. Fine mapping of wheat stripe rust resistance gene Yr26 based on collinearity of wheat with Brachypodium distachyon and rice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57885.

William M, Singh R, Huerta-Espino J, Islas SO, Hoisington D. Molecular marker mapping of leaf rust resistance gene Lr46 and its association with stripe rust resistance gene Yr29 in wheat. Phytopathol. 2003;93:153–9.

Lin F, Chen X. Genetics and molecular mapping of genes for race-specific all-stage resistance and non-race-specific high-temperature adult-plant resistance to stripe rust in spring wheat cultivar Alpowa. Theor Appl Genet. 2007;114:1277–87.

Wang R, Hai L, Zhang X, You G, Yan C, Xiao S. QTL mapping for grain filling rate and yield-related traits in RILs of the Chinese winter wheat population Heshangmai× Yu8679. Theor Appl Genet. 2009;118:313–25.

Liu F, Niu Y, Deng H, Tan G. Mapping of a major stripe rust resistance gene in Chinese native wheat variety Chike using microsatellite markers. JGG. 2007;34:1123–30.

Peng J, Fahima T, Röder M, Li Y, Dahan A, Grama A, et al. Microsatellite tagging of the stripe-rust resistance gene YrH52 derived from wild emmer wheat, Triticum dicoccoides, and suggestive negative crossover interference on chromosome 1B. Theor Appl Genet. 1999;98:862–72.

Rosewarne G, Herrera-Foessel S, Singh R, Huerta-Espino J, Lan C, He Z. Quantitative trait loci of stripe rust resistance in wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2013;126:2427–49.

Case AJ, Naruoka Y, Chen X, Garland-Campbell KA, Zemetra RS, Carter AH. Mapping stripe rust resistance in a BrundageXCoda winter wheat recombinant inbred line population. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91758.

Gerechter-Amitai Z, Van Silfhout C, Grama A, Kleitman F. Yr15—a new gene for resistance to Puccinia striiformis in Triticum dicoccoides sel. G-25. Euphytica. 1989;43:187–90.

Hovmøller MS, Justesen AF. Appearance of atypical Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici phenotypes in north-western Europe. Aust J Agric Res. 2007;58:518–24.

Hovmøller MS, Rodriguez-Algaba J. Global rust reference center. 2021. https://agro.au.dk/forskning/internationale-platforme/wheatrust/.

Chen C, He Z, Lu J, Li J, Ren Y, Ma C, et al. Molecular mapping of stripe rust resistance gene YrJ22 in Chinese wheat cultivar Jimai 22. Mol Breed. 2016;36:1–8.

Randhawa MS, Bariana HS, Mago R, Bansal UK. Mapping of a new stripe rust resistance locus Yr57 on chromosome 3BS of wheat. Mol Breed. 2015;35:1–8.

Suenaga K, Singh R, Huerta-Espino J, William H. Microsatellite markers for genes Lr34/Yr18 and other quantitative trait loci for leaf rust and stripe rust resistance in bread wheat. Phytopathol. 2003;93:881–90.

Zhao L, Feng J, Zhang C-Y, Xu X-D, Chen X-M, Sun Q, et al. The dissection and SSR mapping of a high-temperature adult-plant stripe rust resistance gene in American spring wheat cultivar Alturas. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2012;134:281–8.

Yang E-N, Rosewarne G, Herrera-Foessel S, Huerta-Espino J, Tang Z-X, Sun C-F, et al. QTL analysis of the spring wheat “Chapio” identifies stable stripe rust resistance despite inter-continental genotype× environment interactions. Theor Appl Genet. 2013;126:1721–32.

William H, Singh R, Huerta-Espino J, Palacios G, Suenaga K. Characterization of genetic loci conferring adult plant resistance to leaf rust and stripe rust in spring wheat. Genome. 2006;49:977–90.

Basnet B, Singh R, Ibrahim A, Herrera-Foessel S, Huerta-Espino J, Lan C, et al. Characterization of Yr54 and other genes associated with adult plant resistance to yellow rust and leaf rust in common wheat Quaiu 3. Mol Breed. 2014;33:385–99.

Lan C, Rosewarne GM, Singh RP, Herrera-Foessel SA, Huerta-Espino J, Basnet BR, et al. QTL characterization of resistance to leaf rust and stripe rust in the spring wheat line Francolin# 1. Mol Breed. 2014;34:789–803.

Dedryver F, Paillard S, Mallard S, Robert O, Trottet M, Negre S, et al. Characterization of genetic components involved in durable resistance to stripe rust in the bread wheat ‘Renan.’ Phytopathol. 2009;99:968–73.

Liu J, He Z, Wu L, Bai B, Wen W, Xie C, et al. Genome-wide linkage mapping of QTL for adult-plant resistance to stripe rust in a Chinese wheat population Linmai 2× Zhong 892. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0145462.

Bariana H, Bansal U, Schmidt A, Lehmensiek A, Kaur J, Miah H, et al. Molecular mapping of adult plant stripe rust resistance in wheat and identification of pyramided QTL genotypes. Euphytica. 2010;176:251–60.

Bansal U, Forrest K, Hayden M, Miah H, Singh D, Bariana H. Characterisation of a new stripe rust resistance gene Yr47 and its genetic association with the leaf rust resistance gene Lr52. Theor Appl Genet. 2011;122:1461–6.

Zwart R, Thompson J, Milgate A, Bansal U, Williamson P, Raman H, et al. QTL mapping of multiple foliar disease and root-lesion nematode resistances in wheat. Mol Breed. 2010;26:107–24.

Ren Y, He Z, Li J, Lillemo M, Wu L, Bai B, et al. QTL mapping of adult-plant resistance to stripe rust in a population derived from common wheat cultivars Naxos and Shanghai 3/Catbird. Theor Appl Genet. 2012;125:1211–21.

Wang L, Ma J, Zhou R, Wang X, Jia J. Molecular tagging of the yellow rust resistance gene Yr10 in common wheat, PI 178383 (Triticum aestivum L.). Euphytica. 2002;124:71–3.

Xiang C, Feng J, Wang M, Chen X, See D, Wan A, et al. Molecular mapping of stripe rust resistance gene Yr76 in winter club wheat cultivar Tyee. Phytopathol. 2016;106:1186–93.

Ma D, Fang Z, Yin J, Chao K, Jing J, Li Q, et al. Molecular mapping of stripe rust resistance gene YrHu derived from Psathyrostachys huashanica. Mol Breed. 2016;36:1–9.

Dray S, Dufour A-B. The ade4 package: implementing the duality diagram for ecologists. J Stat Softw. 2007;22:1–20.

Remington DL, Thornsberry JM, Matsuoka Y, Wilson LM, Whitt SR, Doebley J, et al. Structure of linkage disequilibrium and phenotypic associations in the maize genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:11479–84.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 3.0.2. 2020. http://www.R-project.org/.

Hovmøller MS, Rodriguez-Algaba J, Thach T, Justesen AF, Hansen J. Report for Puccinia striiformis race analyses/molecular genotyping, GRRC, Flakkebjerg, DK-4200 Slagelse, Denmark. 2019. https://agro.au.dk/fileadmin/www.grcc.au.dk/International_Services/Pathotype_YR_results/Summary_of_Puccinia_striiformis_molecular_genotyping_2018.pdf.

Hovmøller MS, Rodriguez-Algaba J, Thach T, Justesen AF, Hansen J. Report for Puccinia striiformis race analyses and molecular genotyping 2017, Global Rust Reference Center (GRRC), Aarhus University, Flakkebjerg, DK-4200 Slagelse, Denmark. 2018. https://agro.au.dk/fileadmin/Summary_of_Puccinia_striiformis_race_analysis_2017.pdf.

McNeal F, Konzak C, Smith E, Tate W, Russell T. A uniform system for recording and processing cereal research data. US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. 1971;42:34–121.

Peterson RF, Campbell A, Hannah A. A diagrammatic scale for estimating rust intensity on leaves and stems of cereals. Can J Res. 1948;26:496–500.

Wilcoxon RD, Skovmand B, Atif A. Evaluation of wheat cultivars for ability to retard development of stem rust. Ann Appl Biol. 1975;80:275–81.

Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, Team RC. nlme: Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R Package Version. 2013;3:111.

Milliken GA, Johnson DE. Analysis of messy data, volume III: analysis of covariance. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2001. p. 624.

Hallauer AR, Carena MJ, Miranda Filho Jd. Quantitative genetics in maize breeding. Iowa: Springer Science & Business Media; 2010. p. 662.

Wang J, Zhang Z. GAPIT Version 3: boosting power and accuracy for genomic association and prediction. GPB. 2021;19:629–40.

Huang M, Liu X, Zhou Y, Summers RM, Zhang Z. BLINK: a package for the next level of genome-wide association studies with both individuals and markers in the millions. GigaScience. 2019;8:giy154.

Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100:9440–5.

Anand L, Rodriguez Lopez CM. ChromoMap: an R package for interactive visualization of multi-omics data and annotation of chromosomes. BMC Bioinform. 2022;23:1–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Jorge Dubcovsky (UCDavis, California, EEUU) for kindly providing the association mapping population used in this study, and members of the Grupo Trigo Balcarce (Estación Experimental Agropecaria INTA Balcarce) for helping with the experiments.

Funding

This project was supported by the project PE-I126 from the National Institute of Agricultural Technology (INTA), Argentina. MFF has a scholarship granted by the National Council for Science and Technology (CONICET), Argentina. These funding organizations did not play a role in the study design, analysis, or data interpretation presented in this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MFF and LSV conceived the experiments and the manuscript; MFF and ANP carried out the field experiments; MFF and PEC carried out the greenhouse experiments; MFF and LSV performed the GWAS analysis; MFF drafted the manuscript; ACP, ANP and PEC improved the manuscript. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Methodological statement

All methods were carried out in accordance with the appropriate guideline for plant material used in the study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table S1.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine the significance of the fixed effects of genotypes for Infection type for Yr19-71 and Yr20-161 races. Supplementary Table S2. Sequential restricted maximum likelihood ratio tests to determine the significances of the random effects of genotypes and genotype by year interactions for DS and AUDPC. Supplementary Table S3. Variance component estimates (genotypic, genotype x year interaction and residual variances) and broad-sense heritability (H2) for the analyzed traits. Supplementary Table S4. Information of the reported stripe rust resistance genes or quantitative trait loci on the segments of the chromosomes containing the genomic regions identified in this study. Supplementary Table S5. Accession number, synonyms, origin, pedigrees and subpopulation for the 245 bread wheat accessions included in the GWAS. Supplementary Table S6. Wheat differential lines used for race typing of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici. Supplementary Table S7. Virulence/avirulence formula of the Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici races used for seedling resistance screening.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Figure S1.

Structure analysis in the spring wheat association-mapping panel. a) The STRUCTURE analysis showed four hypothetical subpopulations represented by different colors. b) First two components (PC1 and PC2) of a principal component analysis of the spring wheat accessions color coded by breeding program (adapted from Zhang, et al. [45]). c) Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree showing the subpopulations corresponding to the structure analysis. Supplementary Figure S2. Quantile-quantile (QQ) plots of the observed and the expected p values of the GWAS model. a) QQ-plot for seedling resistance (infection type -IT- for the races Yr19-71 and Yr20-161); b) QQ-plot for Adult plant resistance (Disease Severity and area under disease progress curve –AUDPC-). Supplementary Figure S3. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) decay over physical distance. The scatter plots showing pairwise SNP markers LD r2 value as a function of inter-marker physical distances (Mbp) of (a) 1B chromosome; (b) 2A chromosome; (c) 3A chromosome; (d) 3B chromosome; (e) 5B chromosome; (f) 7A chromosome. The red curve represents the model fit to LD decay. The blue dashed line represents the specific critical r2 value beyond which LD is likely due to linkage. The green dashed line represents the confidence interval for the quantitative trait loci regions in which LD r2 = critical r2 value.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Franco, M.F., Polacco, A.N., Campos, P.E. et al. Genome-wide association study for resistance in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) to stripe rust (Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici) races in Argentina. BMC Plant Biol 22, 543 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-022-03916-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-022-03916-y