Abstract

Background

Stripe rust, caused by the fungal pathogen Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici (Pst), is a serious foliar disease of wheat. Identification of novel stripe rust resistance genes and cultivation of resistant cultivars are considered to be the most effective approaches to control this disease. In this study, we evaluated the infection type (IT), disease severity (DS) and area under the disease progress curve (AUDPC) of 143 Chinese wheat landrace accessions for stripe rust resistance. Assessments were undertaken in five environments at the adult-plant stage with Pst mixture races under field conditions. In addition, IT was assessed at the seedling stage with two prevalent Pst races (CYR32 and CYR34) under a controlled greenhouse environment.

Results

Seventeen accessions showed stable high-level resistance to stripe rust across all environments in the field tests. Four accessions showed resistance to the Pst races CYR32 and CYR34 at the seedling stage. Combining phenotypic data from the field and greenhouse trials with 6404 markers that covered the entire genome, we detected 17 quantitative trait loci (QTL) on 11 chromosomes for IT associated with seedling resistance and 15 QTL on seven chromosomes for IT, final disease severity (FDS) or AUDPC associated with adult-plant resistance. Four stable QTL detected on four chromosomes, which explained 9.99–23.30% of the phenotypic variation, were simultaneously associated with seedling and adult-plant resistance. Integrating a linkage map of stripe rust resistance in wheat, 27 QTL overlapped with previously reported genes or QTL, whereas four and one QTL conferring seedling and adult-plant resistance, respectively, were mapped distantly from previously reported stripe rust resistance genes or QTL and thus may be novel resistance loci.

Conclusions

Our results provided an integrated overview of stripe rust resistance resources in a wheat landrace diversity panel from the southern autumn-sown spring wheat zone of China. The identified resistant accessions and resistance loci will be useful in the ongoing effort to develop new wheat cultivars with strong resistance to stripe rust.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Wheat (Triticum aestivum) is an important cereal crop worldwide and is a central pillar of global food security [1, 2]. In the coming decades, wheat production must increase more rapidly to keep pace with continued population growth [3]. However, to increase yield stably under climate change and biotic stress is an extreme challenge [4, 5]. Stripe rust, caused by the pathogenic fungus Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici (Pst), is a serious foliar disease of wheat that poses an increasing threat to wheat production worldwide [1]. The disease develops in wheat-producing areas with hypothermal and moist environments during the growing season, especially in China, which has experienced the largest wheat stripe rust epidemics by area in the world [6, 7]. The nationwide severe epidemics of wheat stripe rust in 1950, 1964, 1990 and 2002 caused substantial reductions in wheat yield [8]. In 2017, the stripe rust epidemic affected 1.65 million ha in 12 provinces [9]. Stripe rust is a critical constraint to wheat production and losses in grain yield can attain 40 to 100% under severe infections [10]. To reduce losses, appropriate application of fungicides is effective to control the disease. However, the effects of the high cost of fungicides and environmental concerns must be considered [11]. As a result of changes in the predominant races and emergence of new races, many wheat cultivars have become susceptible to stripe rust, thus accelerating the cultivar turnover frequency [7]. Mining of novel genetic resources and the breeding of disease-resistant cultivars is an effective, economic and environmentally friendly strategy to control stripe rust in wheat [7, 12].

Stripe rust resistance can be classified as all-stage resistance (ASR; also termed seedling resistance) or adult-plant resistance (APR) based on the growth stage of the plant [13]. The resistance genes can be classified as race-specific or race non-specific according to their effectiveness against different Pst races. Generally, race-specific resistance is expressed at all growth stages (from the seedling to the adult-plant stages) and thus belong to ASR. Wheat cultivars that carry these genes may become susceptible when new or rare pathogen races arise [14]. In contrast, genes conferring APR are usually race non-specific [15]. Combining APR and ASR genes is an important approach to develop new wheat cultivars with adequate durable resistance [11, 16, 17].

To date, 83 Yr genes for stripe rust resistance have been formally designated (Yr1 to Yr83) and more than 100 temporarily named Yr genes or quantitative trait loci (QTL) have been reported [18,19,20]. However, many of these resistance genes are ineffective against newly prevalent Pst races or are not yet widely incorporated in wheat cultivars in China and elsewhere [21, 22]. As an example, Yr9 was widely used in Chinese wheat breeding since the 1960s [8, 23]. A new Pst race CYR29 (Chinese yellow rust 29 with virulence to Yr9) was detected in 1985, resulting in yield losses of 2.65 million tonnes in 1990 [8]. Similar consequences were observed with the emergence and prevalence of the races CYR31, CYR32 and CYR33, resulting in loss of stripe rust resistance in many wheat cultivars (including Fan 6, Kangyin 655, Suwon 11 and their derivative cultivars) [8]. The race CYR34 emerged in 2009 and has become the main source of virulence against Guinong 22 and its derivative cultivars carrying the Yr24/Yr26 locus [24]. At present, CYR32 and CYR34 are the most virulent and predominant races in China [9, 24]. Accordant with the aphorism “Rust never sleeps” [25], there is an ongoing need to search for novel sources of genetic resistance to stripe rust.

China is considered to be a unique epidemiological zone and the largest independent epidemic region [1]. Wheat stripe rust most frequently affects the winter wheat production areas in Northwest, Southwest and North China and the spring wheat growing areas in Northwest China [23]. There is considerable diversity in epidemiological conditions among the wheat-growing areas in China [26]. Overall, the region of southern Gansu and northwestern Sichuan was considered to be a “center of origin for virulence” [8]. Identification and utilization of novel sources of resistance genes are essential for improvement of stripe rust resistance in wheat breeding in this zone. Wheat landraces have been selected by farmers over many years to adapt to local environmental conditions [27]. Such landraces harbor great diversity of genes that respond to abiotic and biotic stresses and influence traits such as growth habit, cold, heat or drought tolerance, early growth vigor, competitiveness with weeds, and disease tolerance [27]. These genes may be important resources useful for stripe rust resistance breeding [12, 20, 28,29,30,31]. However, relatively few studies have investigated genetic diversity and stripe rust resistance in wheat landraces from the southern autumn-sown spring wheat zone of China.

Genome-wide association study (GWAS) is an effective approach to investigate complex phenotypic traits and to identify loci associated with target traits [32]. GWAS has been widely used to study agronomically important traits of a variety of crops, including maize, soybean, rice, cotton and wheat [33,34,35,36,37]. In addition, GWAS has been used to identify the genes underlying resistance to stripe rust in wheat [20, 38,39,40]. In the present study, 143 common wheat landrace accessions from the southern autumn-sown spring wheat zone of China were evaluated for resistance to Pst at the seedling and adult-plant stages in multiple years and field locations. We assessed the genetic diversity, population structure and linkage disequilibrium (LD) patterns of the accessions based on Diversity Arrays Technology sequencing (DArT-seq) and simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers and identified genomic regions controlling stripe rust resistance for utilization in wheat breeding.

Results

Analysis of stripe rust response

To characterize seedling resistance to stripe rust, we recorded the infection type (IT) response to the Pst races CYR32 and CYR34 at the seedling stage for the wheat landrace panel. The susceptible check Mingxian 169 was rated with IT = 4 for the two races tested. The majority of accessions in this panel showed a high frequency of susceptibility to CYR32 (95.8%) and CYR34 (93.7%), respectively. Based on the IT, four accessions (IT ≤2) including Lushanmai (AS661605), Yuqiumai (AS661657), Zhenixiaomai (AS661777) and Guangtoumai (AS661671) were resistant to both the Pst races (Fig. 1a, Additional file 1).

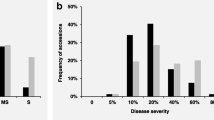

Box plot, violin plot and raw data points distributions of IT (a) evaluated in the seedling stage for CYR32 and CYR34; At the adult plant stage, IT (b), FDS (c) and the AUDPC (d) evaluated against Pst of mixed races in five environments. Tests at Chongzhou from the year 2016 to 2018 was referred to as CZ16, CZ17 and CZ18; at Mianyang from the year 2016 to 2017 referred to as MY16 and MY17, respectively

The responses of the 143 wheat landraces to mixed races of Pst were evaluated in five environments in the field (designated CZ16, CZ17, CZ18, MY16 and MY17). Based on BLUP values, a Pearson correlation analysis revealed significant correlations (P < 0.01) for IT, final disease severity (FDS) and area under the disease progress curve (AUDPC) that were observed among the five environments at the adult-plant stage, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.58 to 0.89, 0.57 to 0.89 and 0.60 to 0.92, respectively (Additional file 2). The H2 values for IT, FDS and AUDPC were high across the five environments and BLUP values; the H2 values were 93.98, 94.07 and 94.02%, respectively (Table 1). The panel showed a higher frequency of resistance in the field environments than that observed in the seedling tests. With regard to IT (≤ 2), 48.3–75.5% of the accessions displayed resistance to the mixed Pst races in all five environments at the adult-plant stage (Fig. 1b, Additional file 1). Similarly, 63.6–89.5% of the accessions displayed resistance with low FDS values (< 60%) under the five environments (Fig. 1c, Additional file 1). Across the five environments, the phenotypic performance of the panel varied from 0 to 14 for AUDPC (Fig. 1d, Additional file 1). Seventeen accessions showed stable high-level resistance to stripe rust across all environments under field tests. These accessions originated from Sichuan (6), Yunnan (6), Gansu (3), Guizhou (1) and Shaanxi (1) (Additional file 1), respectively. Among these accessions, Lushanmai (from Sichuan) and Guangtoumai (from Guizhou) showed stable resistance to the Pst races CYR32 and CYR34 at the seedling stage and resistance in all field environments. In addition, Bendiyoumangxiaomai (from Yunnan) and Liulengmai (from Guizhou) likely showed ASR resistance to a single Pst race (CYR32 or CYR34) (Additional file 1).

Genetic diversity analysis

After filtering, 6404 polymorphic markers (comprising 5898 polymorphic DArT-seq markers and 506 polymorphic allele variations for SSR markers) were retained for the 143 accessions. Among these markers, 2120, 3229 and 1055 markers were located in the A, B and D subgenomes, respectively. Chromosome 2B (709) carried the most markers, whereas chromosome 4D (52) carried the fewest markers. Gene diversity, polymorphism information content (PIC) and minor allele frequency (MAF) for the entire genome ranged from 0.2879 to 0.3653, 0.2355 to 0.2916 and 0.2070 to 0.2800 with averages of 0.3288, 0.2664 and 0.2390, respectively. Subgenome B showed the highest gene diversity, PIC and MAF values (0.3307, 0.2674 and 0.2407, respectively). Subgenome D exhibited the lowest gene diversity, PIC and MAF values (0.3232, 0.2630 and 0.2319, respectively). Among individual chromosomes, chromosome 6A carried 376 markers and showed the highest genetic diversity, PIC and MAF values, whereas chromosome 2D carried 270 markers and exhibited the lowest genetic diversity, PIC and MAF values (Table 2).

Population structure, kinship and LD analyses

The population structure (Q-matrix) was calculated by means of Bayesian clustering using the 6404 polymorphic markers for the 143 accessions, which were divided into two subgroups, designated subgroup 1 (Gp1) and subgroup 2 (Gp2) (Additional file 3a). Gp1 contained 67 accessions, which originated from Sichuan (52), Yunnan (7), Shaanxi (5), Gansu (2) and Guizhou (1) provinces. Gp2 consisted of 76 accessions that originated from Fujian (6), Gansu (5), Guangdong (12), Guangxi (4), Guizhou (14), Hunan (1), Jiangxi (1), Shaanxi (1), Sichuan (18) and Yunnan (14) provinces. On the basis of IT scores, Gp1 contained a higher number of accessions (33) that showed resistance to stripe rust than that of Gp2 (12) in all five environments (Additional file 1). All accessions in each subgroup (Gp1 and Gp2) formed a single cluster (Additional file 3b). The extent of LD and average rate of LD decay of the 143 genotypes was graphically displayed based on pairwise LD squared correlation coefficients (r2) for all intra-chromosomal markers against the genetic distance (Additional file 4). The half-decay distance was 4 cM when the LD declined to 50% (r2 = 0.25) of its initial value. Hence, the significant associated loci on the same chromosome within the confidence interval of ±4 cM were considered to be located in the same quantitative trait locus (QTL) block.

Marker–trait associations at the seedling stage

Using data for the 6404 polymorphic markers, a GWAS analysis was performed for stripe rust IT to a single Pst race (CYR32 or CYR34) at the seedling stage based on a mixed linear model. The GWAS for IT identified a total of 18 DArT-seq markers and one SSR marker within 17 QTL on 11 chromosomes as significantly associated (P < 0.001) with seedling resistance; these markers were located on chromosomes 1A, 1B, 2A, 2B, 3B, 4A, 5B, 6A, 6B, 7B and 7D (Fig. 2). The phenotypic variation explained (PVE) by the marker–trait associations ranged from 8.71 to 17.94% (Table 3). Based on the LD decay distance observed in this study, significant markers within 4 cM were combined as a QTL, hence 17 QTL regions were detected with IT. Of these QTL, 10 QTL were significantly associated with ASR to CYR32 and seven QTL were significantly associated with ASR to CYR34. Thirteen of these QTL corresponded with previously reported genes or QTL, and four potentially novel QTL associated with seedling resistance were identified on chromosomes 1B, 2B, 3B and 6A (Fig. 3, Additional file 5).

The MLM Manhattan plot of stripe rust resistance significantly associated markers. The horizontal line shows the genome-wide significant threshold –log10(P) value of 3.0. The associated MTAs for IT of CYR32, CYR34 with seedling resistance, IT, FDS and AUDPC based on the BLUP from the inner circle to the outer circle

The position of the potentially novel QTL on chromosomes 1B, 2B, 3B and 6A in this study. QTL marked as red color on the left side of chromosomes were the potentially new QTL in this study. The reported genes and QTL were marked as black color and mapped on the left and right side of the chromosomes separately

Marker–trait associations at the adult-plant stage

Following the same procedure, the GWAS analysis was also performed for IT, FDS and AUDPC of stripe rust against the mixed Pst races within five environments at the adult-plant stage. A total of 32 markers (31 DArT-seq markers and one SSR marker) within 15 QTL on seven chromosomes were identified as significantly associated (P < 0.001) with APR in at least two environments; these markers were located on chromosomes 1B, 2A, 2B, 3B, 4A, 5B and 6A (Fig. 2). The PVE by the marker–trait associations ranged from 8.09 to 23.77% (Table 4). On chromosomes 1B, 2B and 4A, five markers were associated with one trait (IT, FDS, or AUDPC). In addition, 27 markers represented loci significantly associated with stripe rust FDS and AUDPC on chromosomes 1B, 2A, 2B, 3B, 5B and 6A. The ranges in PVE for the FDS and AUDPC loci were in the ranges 8.09–20.92% and 8.16–23.77%, respectively. Based on the LD decay distance observed in this study, significant markers within 4 cM were combined as a QTL, hence a total of 15 QTL regions for IT, FDS, and AUDPC were detected. Chromosome 1B contained four QTL, chromosomes 3B and 5B carried three QTL each, chromosome 2B included two QTL and one QTL was detected on each of chromosomes 2A, 4A and 6A. Among these QTL, 11 QTL linked to one marker were associated with IT, FDS, or AUDPC, respectively. The locus QYrsicau-5B.3 linked to 1,108,002 and 1,223,817 was associated with both FDS and AUDPC and the PVE was 13.75–20.08% and 14.39–23.3%, respectively. QYrsicau-2B.1 and QYrsicau-5B.2 were linked to three and six markers, respectively. Notably, QYrsicau-3B.3 was linked to ten markers, of which 1,129,542 was associated with both FDS and AUDPC in three and five environments and the PVE was 19.66 and 19.29%, respectively. Fourteen QTL corresponded with previously reported genes or QTL. QYrsicau-6A was a potentially novel QTL associated with the adult-plant stage response (Fig. 3, Additional file 5). Notably, four QTL (QYrsicau-1B.2, QYrsicau-2B.1, QYrsicau-3B.2 and QYrsicau-5B.3) on chromosomes 1B, 2B, 3B and 5B were detected at the seedling and adult-plant stages for which the PVE ranged from 9.99 to 23.30%, respectively.

Favorable allele analyses

Four QTL were significantly associated with stripe rust in at least four environments in the field. These stable QTL, consisting of QYrsicau-2B.1, QYrsicau-3B.3, QYrsicau-5B.2 and QYrsicau-5B.3, showed the highest frequencies (68.53–86.71%) among the favorable resistance-associated alleles in the 143 accessions. We investigated the additive effects of the favorable alleles of these four APR QTL on the traits BLUP_IT, BLUP_FDS and BLUP_AUDPC (Fig. 4). A significant negative correlation was identified between the number of favorable alleles in individual accessions and the respective stripe rust IT, FDS and AUDPC, with R2 values of 0.17, 0.30 and 0.31, respectively. These results indicated that accessions with favorable alleles exhibited higher resistance to stripe rust, and supported the use of a combination of several loci for wheat disease-resistance breeding (Fig. 4).

Discussion

Stripe rust resistance in the wheat landrace diversity panel from the southern autumn-sown spring wheat zone of China

In this study, 143 common wheat landrace accessions from the southern autumn-sown spring wheat zone of China were evaluated for resistance against Pst at the seedling and adult-plant stages. Based on IT scores, 33 (49.25%) resistant accessions in this panel were clustered in Gp1, whereas Gp2 contained 12 (15.79%) accessions. Interestingly, all of these 45 accessions originated from southwestern provinces, namely Sichuan (26 accessions), Yunnan (8), Shaanxi (4), Guizhou (4) and Gansu (3). China is considered to be a unique epidemiological zone [1]. The autumn-sown spring wheat production areas of these provinces are located within stripe rust epidemic regions in China [23, 26]. In particular, southern Gansu and northwestern Sichuan comprise a “center of origin for virulence” [8]. Understandably, resistant accessions were more likely to be selected by farmers among wheat landraces grown in the stripe rust epidemic regions. Furthermore, a majority of resistant accessions in this panel displayed APR resistance to stripe rust, suggesting that race non-specific and durable resistance genes might be favored by artificial selection in Chinese wheat landraces to provide durable resistance. For example, ‘Chinese Spring’, which is a wheat landrace originating from Sichuan province, showed stable resistance to stripe rust across all environments at the adult-plant stage. This accession carries Yr18 [71], which is a durable stripe rust resistance gene that is frequently present in Chinese wheat landraces [72]. Such resistant accessions from Chinese wheat landraces represent a valuable resource for development of durable stripe rust resistant cultivars in wheat breeding.

Comparison of high-confidence loci with adult-plant resistance other wheat zones of China

Thirty-two markers linked with 15 QTL on seven chromosomes were identified as significantly associated (P < 0.001) with IT, FDS or AUDPC in at least two environments with APR. Six putative QTL for stripe rust resistance have been identified previously in Chinese landrace wheat populations from different wheat-growing zones [20, 30, 31]. Five of these QTL, including QYrsicau-1B.1, QYrsicau-1B.2, QYrsicau-2A, QYrsicau-5B.1 and QYrsicau-5B.3, were located close to QTL previously identified in accessions from the Yellow and Huai River Valleys [30]. QYrsicau-1B.1, QYrsicau-1B.2 and QYr.sicau-2B.2 were located close to QTL previously identified in landraces from the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River [20]. Only two QTL, QYrsicau-1B.2 and QYrsicau-5B.1, were identified in the northern Chinese wheat zone [31]. The QTL shared among wheat zones likely originated in ancestral landraces and the present-day distribution of these QTL might reflect the historical spread of wheat in China [73] and differences in selection pressures for stripe rust. Nine QTL were unique to the southern autumn-sown spring wheat zone of China, suggesting that wheat landraces from this zone harbor unique characteristics in the genetic diversity of resistance to stripe rust and may be used as novel germplasm resources for stripe rust resistance breeding.

Novel stripe rust resistance loci

In the present landrace wheat panel, 19 loci within 17 QTL were significantly associated with ASR to Pst detected in the seedling test. However, no overlap in QTL for seedling resistance to the two races CYR32 and CYR34 was observed, presumably because few accessions were resistant to both Pst races in this panel. Of these QTL, four QTL differed from previously identified genes or QTL for resistance to Pst (Table 3). Three potentially novel loci (Yrsicau-2B.2, Yrsicau-3B.2, and Yrsicau-6A.2) were associated with resistance to CYR32, and Yrsicau-1B.2 was associated with resistance to CYR34. Yrsicau-1B.2 was closely associated with YrC142, which is a temporarily designated stripe rust resistance gene in synthetic wheat CI142 [74]. However, CI142 is a synthetic wheat line originating from a durum wheat (Triticum durum) × Aegilops tauschii cross. There is a negligible likelihood that a QTL in a Chinese wheat landrace is identical to one that originated in durum wheat. Yrsicau-2B.2 was located close to QYraq.cau-2BL flanked by the microsatellite markers Xwmc175 and Xwmc332. QYraq.cau-2BL is derived from an Italian winter wheat cultivar Aquileja [75] and is an APR locus. Thus, the ASR locus Yrsicau-2B.2 is predicted to differ from QYraq.cau-2BL. Based on the consensus map, Yrsicau-3B.2 identified by the marker 3,953,802 and Yrsicau-6A.2 identified by 3,021,470 are unlikely to be closely linked with previously identified genes or QTL. Therefore, these four ASR loci are potentially novel. Several accessions that show ASR to stripe rust were observed to carry these novel loci. For example, Yuqiumai (AS661657), Zhenixiaomai (AS661777) and Guangtoumai (AS661671), which show resistance to both CYR32 and CYR34, carried the resistance alleles of Yrsicau-1B.2 and Yrsicau-3B.2. These resistant accessions carrying novel ASR loci could be utilized for development of wheat cultivars possessing ASR to stripe rust.

In addition, 32 markers within 15 QTL on seven chromosomes were identified as significantly associated (P < 0.001) with IT, FDS or AUDPC in at least two environments with APR (Table 4). However, all of these QTL except QYrsicau-6A were tightly linked or overlapped with the positions of known APR genes or QTL (Table 4). QYrsicau-6A was identified by the DArT-seq marker 3,021,470, which was located on the long arm of chromosome 6A at ~ 609.4 Mb and explained 9.76–14.38% of the phenotypic variation across different environments. This novel QTL was detected in 13 accessions that showed high levels of APR for stripe rust (IT ≤1) (Additional file 1). These resistant accessions may serve as favorable donor parents of APR for wheat breeding.

Conclusions

In this study, we evaluated the stripe rust resistance of 143 wheat landrace accessions from the southern autumn-sown spring wheat zone of China. Seventeen accessions showed stable high-level resistance to stripe rust at the adult-plant stage in five test environments, whereas four accessions showed resistance to the Pst races CYR32 and CYR34 at the seedling stage. The GWAS results revealed that 19 loci within 17 QTL were significantly associated with ASR, and 32 loci within 15 QTL were identified as significantly associated with APR. Among these loci were five potentially novel QTL. The identified resistant accessions and resistance loci will be useful in the ongoing effort to develop new wheat cultivars with strong resistance to stripe rust.

Methods

Plant materials

A collection of 143 common wheat Chinese landrace accessions obtained from the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences of National Germplasm Repository were used in this study. These accessions were originated from 10 Chinese provinces, namely Sichuan (70), Yunnan (21), Guizhou (15), Guangdong (12), Gansu (7), Fujian (6), Shaanxi (6), Guangxi (4), Hunan (1) and Jiangxi (1). The list of accessions is provided in Additional file 1.

Greenhouse evaluation

Evaluation of the IT response of wheat seedlings to two prevalent Chinese Pst races (CYR32 and CYR34) was performed under a controlled greenhouse environment at the Plant Protection Institute of the Gansu Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Gansu, China. The avirulence/virulence classification of the Pst races is provided in Additional file 6 [9, 24, 37, 49, 76,77,78,79,80]. Five to six seeds of each accession were sown in a plastic pot filled with nutrient soil. Seedlings of each accession were inoculated with Pst races when plants were at approximately the two-leaf stage. First, a spore suspension (fresh uredospores:aqueous Twain, 25:1, m/V) was prepared. The spore suspension was evenly sprayed on the leaves of the plants. The suspension was left for 30 min to dry. The inoculated plants were placed in a dark dew chamber in full humidity for 24 h at 10–15 °C. Subsequently, the plants were moved to a greenhouse maintained at 15–16 °C. A photoperiod of 12–14 h light and 10–12 h darkness was maintained throughout the experiment. The susceptible control was the highly susceptible wheat cultivar Mingxian 169. The IT was scored 15–18 d after inoculation [81] using the 0–4 scale described previously, as follows: resistant (0–2) and susceptible (3–4) [82].

Field evaluation

All accessions were assessed for stripe rust resistance at the adult-plant stage after artificial inoculation in 5 year-location environments performed at two field sites in Sichuan Province, namely Chongzhou (CZ; 30°33′N, 103°39′E) and Mianyang (MY; 31°23′N, 104°49′E). Seeds were sown at Chongzhou in late October and at Mianyang in early November. The evaluations were performed at Chongzhou from 2016 to 2018 (three crop seasons) and at Mianyang in 2016 and 2017 (two crop seasons), which were designated CZ16, CZ17, CZ18, MY16 and MY17, respectively.

In all field trials, five randomly chosen plants of all accessions were evaluated per three replicate rows. Plots were prepared as 1.50-m-long rows, spaced 0.30 m apart, and sown with 15 seeds for each accession. Two highly susceptible common wheat cultivars, SY95–71 and Taichung 29, used as a spreader border were planted around each plot and every 20 rows. At the tillering stage, an equal number of mixed Pst races and talc (1:50, m/V) was mixed evenly, and the daubing method was used for artificial inoculation. Plants were inoculated with a mixture of Chinese prevalent Pst races (CYR 32, CYR 33, CYR 34, Sull-4, Sull-5, Sull-7 and G22–14).

Stripe rust responses were recorded when the susceptible cultivars SY95–71 and Taichung 29 displayed disease severity (DS) of up to 80%. In all trials, stripe rust resistance was evaluated three times at weekly intervals. We scored IT using the 0–4 scale described previously [82]. The DS was scored as percentage of infected leaf area (0, 5, 10, 20, 40, 60, 80% or 100%) in accordance with the standard for monitoring and forecasting wheat stripe rust (National Standard of the People’s Republic of China, GB/T 15795–2011). Data for final disease severity (FDS) were used for GWAS analysis. The DS was used to calculate the AUDPC using the following formula: AUDPC = \( {\sum}_{i=1}^{n-1}\left[\left({x}_{i+1}+{x}_i\right)/2\right]\left({t}_{i+1}-{t}_i\right) \), where xi = flag leaf rust severity on the ith date, ti = the ith day and n = number of times on which DS was recorded [83].

Phenotypic data analysis

To eliminate the impact of environmental factors on stripe rust responses, BLUP values for each accession across environments were calculated by a linear model with random effects for variance components using the lme4 package in R [84]. The broad-sense heritability (H2) estimates for IT, FDS and AUDPC were calculated for each environment using QTL IciMapping v4.1 [85] with the formula H2 = VG/(VG + VE), where VG and VE are estimates of the genetic and environmental variances, respectively [86]. A Pearson’s correlation analysis of BLUP values for the five environments was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The phenotypic variation was estimated as the minimum, maximum and mean values of all traits in the five environments and BLUP values.

Genotyping and genetic diversity

Genomic DNA was extracted from fresh leaf tissue from each accession using the modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide method [87]. DNA samples were diluted to a working solution of 50–100 ng/μL with an A260/ A280 ratio of 1.8–2.0. The panel of 143 wheat landraces was used for genotyping based on DArT-seq technology (Diversity Arrays Technology, Canberra, ACT, Australia). A total of 133 SSR markers, associated with stripe rust resistance genes, were obtained from the GrainGenes database (http://wheat.pw.usda.gov) and previous reports [88,89,90,91], and used for additional genotyping. All SSR markers were subjected to PCR amplification in a reaction volume of 3 μL. The PCR products were separated by 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel and visualized by silver staining [92]. For quality control, markers with missing values > 10% and MAF < 5% were removed [93]. After applying these filtering criteria, 5898 DArT-seq markers and 133 SSR markers with 506 polymorphic allele variations were used to estimate population structure and kinship coefficients for the GWAS. The PIC values were calculated for each marker using the formula PIC = 1 − ∑(Pi)2, where Pi is the proportion of the population carrying the ith allele [94]. PowerMarker v3.25 [95] was used to estimate PIC, MAF and gene diversity of the DArT-seq and SSR data.

Population structure, kinship and LD analysis

A population structure analysis was performed using the Bayesian clustering algorithm implemented in STRUCTURE v2.3.4 [96]. The data set comprised 6404 markers, including 5898 DArT-seq and 506 polymorphic allele variations from SSR markers. In total, ten independent STRUCTURE runs were performed with K-value varying from 1 to 10 using the admixture model with 10,000 replicates for burn-in and 10,000 replicates for Markov chain Monte Carlo iterations [93]. The optimal K-value was determined using the delta K method [97]. Kinship among the 143 wheat landrace accessions was estimated with the 6404 markers using TASSEL v3.0. The LD across the known genetic distance for each chromosome of all accessions was calculated using TASSEL v3.0 [98] with 5898 DArT-seq markers. The LD squared allele frequency correlation was evaluated for the entire genome. Significant pair-wise markers were chosen using the criteria P < 0.001 and r2 > 0.1. The LD decay plot and half-decay distance were generated using r2 and the genetic map distance between markers. All high-confidence associated loci in the half decay distance region on the same chromosome were combined as a single QTL.

Association analysis

To identify loci associated with the response of the 143 accessions to Pst races, GWAS analyses were performed using 6404 markers and the mixed linear model with Q and K as covariates implemented in TASSEL v3.0 software [99]. Association tests were conducted for phenotypic traits values (IT, FDS and AUDPC) from all single environments and the BLUP values. The significance threshold was −log10(P) > 3 [100]. Significant markers were visualized with a Manhattan plot using the “Manhattan” function in the “qqman” package [99] in R × 64 3.6.3. The loci that showed a significant association detected in at least two environments were selected for further analyses.

Comparison of QTL locations with previously reported Yr genes and QTL

We compared the locations of significant QTL determined in this study with those of previously reported Yr genes and QTL based on an integrated map to determine whether the QTL were novel. The map included 80 permanently named Yr genes, 67 temporarily designated Yr genes and 327 previously mapped QTL of DArT-seq, SSR and SNP markers and was generated using BioMercator v4.2 [101, 102]. In the study, physical positions of significant markers were annotated using the reference sequence of bread wheat (IWGSC RefSeq v1.0) [103]. The different markers were combined into a single putative QTL if they were located within a confidence interval of ±4.0 cM (where LD was predicted to fall below the critical threshold of r2 = 0.3) [104].

Availability of data and materials

All the data supporting the results in this article are included in the present and the additional files.

Abbreviations

- APR:

-

Adult-plant resistance

- ASR:

-

All-stage resistance

- AUDPC:

-

Area under the disease progress curve

- BLUP:

-

Best linear unbiased predictor

- CYR34:

-

Chinese yellow rust 34

- DArT-seq:

-

Diversity Arrays Technology sequencing

- DS:

-

Disease severity

- FDS:

-

Final disease severity

- GWAS:

-

Genome-wide association study

- H 2 :

-

Broad-sense heritability

- IT:

-

Infection types

- LD:

-

Linkage disequilibrium

- MAF:

-

Minor allele frequencies

- MTAs:

-

Marker–trait associations

- PIC:

-

Polymorphism information content

- Pst :

-

Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici

- PVE:

-

Phenotypic variation explained

- QTL:

-

Quantitative trait locus

- SSR:

-

Simple sequence repeat

References

Solh M, Nazari K, Tadesse W, Wellings CR. The growing threat of stripe rust worldwide. In: Borlaug global rust initiative (BGRI) conference, 2012. Beijing: Technical Workshop, (ed. McIntosh R. A.); 2012. p. 1–10.

Juliana P, Singh RP, Singh PK, Crossa J, Huerta-Espino J, Lan CX, Bhavani S, Rutkoski JE, Poland JA, Bergstrom GC. Genomic and pedigree-based prediction for leaf, stem, and stripe rust resistance in wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2017;130(7):1–16.

Ray DK, Ramankutty N, Mueller ND, West PC, Foley JA. Recent patterns of crop yield growth and stagnation. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1293.

Abberton M, Batley J, Bentley A, Bryant J, Cai H, Cockram J, Costa DOA, Cseke LJ, Dempewolf H, De PC. Global agricultural intensification during climate change: a role for genomics. Plant Biotechnol J. 2016;14(4):1095–8.

Zeng QD, Wu JH, Liu SJ, Huang S, Wang QL, Mu JM, Yu SZ, Han DJ, Kang ZS. A major QTL co-localized on chromosome 6BL and its epistatic interaction for enhanced wheat stripe rust resistance. Theor Appl Genet. 2019;132(5):1409–24.

Chen WQ, Wellings C, Chen XM, Kang ZS, Liu TG. Wheat stripe (yellow) rust caused by Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici. Mol Plant Pathol. 2014;15(5):433–46.

Li H, Feng J, Xu XD, Lin RM, Wang FT, Xu SC. Genetic analysis and location of a resistance gene for Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici in wheat cultivar Zhengmai 7698. J Genet. 2018;97:931–7.

Chen WQ, Wu LR, Liu TG, Xu SC, Jin SL, Peng YL, Wang BT. Race dynamics, diversity and virulence evolution in Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici, the causal agent of wheat stripe rust in China from 2003 to 2007. Plant Dis. 2009;93:1093–101.

Wang L, Zheng D, Zuo SX, Chen XM, Zhuang H, Huang LL, Kang ZS, Zhao J. Inheritance and linkage of virulence genes in Chinese predominant race CYR32 of the wheat stripe rust pathogen Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:120.

Mumtaz S, Khan IA, Ali S, Zeb B, Iqbal A, Shah Z, Swati ZA. Development of RAPD based markers for wheat rust resistance gene cluster (Lr37-Sr38-Yr17) derived from Triticum ventricosum L. Afr J Biotechnol. 2009;8(7):1188–92.

Chen XM. Integration of cultivar resistance and fungicide application for control of wheat stripe rust. Can J Plant Pathol. 2014;36(3):311–26.

Manickavelu A, Joukhadar R, Jighly A, Lan CX, Huerta-Espino J, Stanikzai AS, Kilian A, Singh RP, Ban T. Genome wide association mapping of stripe rust resistance in afghan wheat landraces. Plant Sci. 2016;252:22–229.

Lin F, Chen XM. Genetics and molecular mapping of genes for race-specific all-stage resistance and non-race-specific high-temperature adult-plant resistance to stripe rust in spring wheat cultivar Alpowa. Theor Appl Genet. 2007;114:1277–87.

Wu JH, Huang S, Zeng QD, Liu SJ, Wang QL, Mu JM, Yu SZ, Han DJ, Kang ZS. Comparative genome-wide mapping versus extreme pool-genotyping and development of diagnostic SNP markers linked to QTL for adult plant resistance to stripe rust in common wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2018;131:1777–92.

Chen XM. High-temperature adult-plant resistance, key for sustainable control of stripe rust. Am J Plant Sci. 2013;4:608–27.

Chen XM, Line RF. Gene action in wheat cultivars for durable, high-temperature, adult-plant resistance and interaction with race-specific, seedling resistance to Puccinia striiformis. Phytopathology. 1995;85:567–72.

Zheng SG, Li YF, Lu L, Liu ZH, Zhang CH, Ao D, Li LR, Zhang CY, Rong L, Luo CP. Evaluating the contribution of Yr genes to stripe rust resistance breeding through marker-assisted detection in wheat. Euphytica. 2017;213:50.

Li JB, Dundas I, Dong CM, Li GR, Trethowan R, Yang ZJ, Hoxha S, Zhang P. Identification and characterization of a new stripe rust resistance gene Yr83 on rye chromosome 6R in wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2020;133:1095–107.

McIntosh RA, Yamazaki Y, Dubcovsky J, Rogers J, Morris C, Appels R, Xia XC. Catalogue of Gene Symbols for Wheat. 2019; Online: https://shigen.nig.ac.jp/wheat/komugi/genes/symbolClassList.jsp.

Cheng YK, Li J, Yao FJ, Long L, Wang YQ, Wu Y, Li J, Ye XL, Wang JR, Jiang QT, Kang HY, Li W, Qi PF, Liu YX, Deng M, Ma J, Jiang YF, Chen XM, Zheng YL, Wei YM, Chen GY. Dissection of loci conferring resistance to stripe rust in Chinese wheat landraces from the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River via genome-wide association study. Plant Sci. 2019;287:110204.

Sharma-Poudyal D, Chen XM, Wan AM, Zhan GM, Kang ZS, Cao SQ, Jin SL, Morgounov A, Akin B, Mert Z, Shah SJA, Bux H, Ashraf M, Sharma RC, Madariaga R, Puri KD, Wellings C, Xi KQ, Wanyera R, Manninger K, Ganzález MI, Koyda M, Sanin S, Patzek LJ. Virulence characterization of international collections of the wheat stripe rust pathogen, Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici. Plant Dis. 2013;97(3):379–86.

Zeng QD, Shen C, Yuan FP, Wang QL, Wu JH, Xue WB, Zhan GM, Yao S, Chen W, Huang LL, Han DJ, Kang ZS. The resistance evaluation of the Yr genes to the main prevalent pathotypes of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici in China. Acta Phytopathol Sinica. 2015;45:641–50.

Wan AM, Zhao ZH, Chen XM, He ZH, Jin SL, Jia QZ, Yao G, Yang JX, Wang BT, Li GB, Bi YQ, Yuan ZY. Wheat stripe rust epidemic and virulence of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici in China in 2002. Plant Dis. 2004;88(8):896–904.

Liu B, Liu TG, Zhang ZY, Jia QZ, Wang BT, Gao L, Peng YL, Jin SL, Chen WQ. Discovery and pathogenicity of CYR34, a new race of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici in China. Acta Phytopathologica Sinica. 2017;47(5):681–7.

Merridee AW, Siiri I, Samuel WF, Naomi LH. Thiol-based redox signalling: rust never sleeps. Int J Biochem Cell B. 2011;43(8):1079–85.

Zeng SM, Luo Y. Long-distance spread and interregional epidemics of wheat stripe rust in China. Plant Dis. 2006;90(8):980–8.

Jaradat A A. Wheat landrace: Genetic resources for sustenance and sustainability. 2011 USDA-ARS, Morris, Minnesota, USA. Available at https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/50600000/products-wheat/AAJ-Wheat%20Landraces.pdf. (Accessed June 2018), 1-20.

Sehgal D, Dreisigacker S, Belen S, Küçüközdemir Ü, Mert Z, Özer E, Morgounov A. Mining centuries old insitu conserved turkish wheat landraces for grain yield and stripe rust resistance genes. Front Genet. 2016;7:201.

Ye XL, Li J, Cheng YK, Yao FJ, Long L, Yu C, Wang YQ, Wu Y, Li J, Wang JR, Jiang QT, Li W, Ma J, Wei YM, Zheng YL, Chen GY. Genome-wide association study of resistance to stripe rust (Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici) in Sichuan wheat. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19:147.

Long L, Yao FJ, Yu C, Ye XL, Cheng YK, Wang YQ, Wu Y, Li J, Wang JR, Jiang QT, Li W, Ma J, Liu YX, Deng M, Wei YM, Zheng YL, Chen GY. Genome-wide association study for adult-plant resistance to stripe rust in Chinese wheat landraces (Triticum aestivum L.) from the yellow and Huai river valleys. Front. Plant Sci. 2019;10:596.

Yao FJ, Zhang XM, Ye XL, Li J, Long L, Yu C, Li J, Wang YQ, Wu Y, Wang JR, Jiang QT, Li W, Ma J, Wei YM, Zheng YL, Chen GY. Characterization of molecular diversity and genome-wide association study of stripe rust resistance at the adult plant stage in northern Chinese wheat landraces. BMC Genet. 2019;20:38.

Korte A, Farlow A. The advantages and limitations of trait analysis with GWAS: a review. Plant Methods. 2013;9:29.

Zhang F, Wu ZC, Wang MM, Zhang F, Dingkuhn M, Xu JL, Zhou YL, Li ZK. Genome-wide association analysis identifies resistance loci for bacterial blight in a diverse collection of indica rice germplasm. PLoS One. 2011;12(3):e174598.

Tian F, Bradbury PJ, Brown PJ, Hsiaoyi H, Qi S, Sherry FG, Rocheford TR, Mcmullen MD, Holland JB, Buckler ES. Genome-wide association study of leaf architecture in the maize nested association mapping population. Nat Genet. 2015;43(2):159–62.

Zhang HY, Li CY, Davis EL, Wang JS, Griffin JD, Kofsky J, Song BH. Genome-wide association study of resistance to soybean cyst nematode (Heterodera glycines) HG type 2.5.7 in wild soybean (Glycine soja). Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:1214.

Fu YZ, Dong CG, Wang J, Wang YY, Li CQ. Genome-wide association study reveals the genetic control underlying node of the first fruiting branch and its height in upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Euphytica. 2019;215:35.

Zhou XL, Hu T, Li X, Yu M, Li YY, Yang SZ, Huang KB, Han DJ, Kang ZS. Genome-wide mapping of adult plant stripe rust resistance in wheat cultivar Toni. Theor Appl Genet. 2019;132:1693–704.

Chen JL, Chu CG, Souza EJ, Guttieri MJ, Chen XM, Xu S, Hole D, Zemetra R. Genome-wide identification of QTL conferring high-temperature adult-plant (HTAP) resistance to stripe rust (Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici) in wheat. Mol Breed. 2012;29:791–800.

Naruoka Y, Garland-Campbell KA, Carter AH. Genome-wide association mapping for stripe rust (Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici) in US Pacific northwest winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2015;128:1083–101.

Godoy JG, Rynearson S, Chen XM, Pumphrey M. Genome-wide association mapping of loci for resistance to stripe rust in North America elite spring wheat germplasm. Phytopathology. 2017;108(2):234–45.

Jighly A, Oyiga BC, Makdis F, Nazari K, Youssef O, Tadesse W, Osman A, Ogbonnaya FC. Genome-wide DArT and SNP scan for QTL associated with resistance to stripe rust (Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici) in elite ICARDA wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) germplasm. Theor Appl Genet. 2015;128:1277–95.

William HM, Singh RP, Huerta-Espino J, Palacios G, Suenaga K. Characterization of genetic loci conferring adult plant resistance to leaf rust and stripe rust in spring wheat. Genome. 2006;49(8):977–90.

Dadkhodaie NA, Karaoglou H, Wellings CR, Park RF. Mapping genes Lr53 and Yr35 on the short arm of chromosome 6B of common wheat with microsatellite markers and studies of their association with Lr36. Theor Appl Genet. 2011;122:479–87.

Prins R, Pretorius ZA, Bender CM, Lehmensiek A. QTL mapping of stripe, leaf and stem rust resistance genes in a Kariega × avocet S doubled haploid wheat population. Mol Breed. 2011;27:259–70.

Ren Y, He ZH, Li J, Lillemo M, Wu L, Bai B, Lu QX, Zhu HZ, Zhou G, Du JY, Lu QL, Xia XC. QTL mapping of adult-plant resistance to stripe rust in a population derived from common wheat cultivars Naxos and Shanghai 3/catbird. Theor Appl Genet. 2012;125:1211–21.

Dong ZZ, Hegarty JM, Zhang JL, Zhang WJ, Chao S, Chen XM, Zhou YH, Dubcovsky J. Validation and characterization of a QTL for adult plant resistance to stripe rust on wheat chromosome arm 6BS (Yr78). Theor Appl Genet. 2017;130:2127–37.

Singh A, Pandey MP, Singh AK, Knox RE, Ammar K, Clarke JM, Clarke FR, Singh RP, Pozniak CJ, Depauw RM. Identification and mapping of leaf, stem and stripe rust resistance quantitative trait loci and their interactions in durum wheat. Mol Breed. 2013;31:405–18.

Lan CX, Zhang YL, Herrera-Foessel SA, Basnet BR, Huerta-Espino J, Lagudah ES, Singh RP. Identification and characterization of pleiotropic and co-located resistance loci to leaf rust and stripe rust in bread wheat cultivar Sujata. Theor Appl Genet. 2015;128:549–61.

Quan W, Hou GL, Chen J, Du ZY, Lin F, Guo Y, Liu S, Zhang ZJ. Mapping of QTL lengthening the latent period of Puccinia striiformis in winter wheat at the tillering growth stage. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2013;136:715–27.

Christopher MD, Liu SY, Hall MD, Marshall DS, Fountain MO, Johnson JW, Milus EA, Garland-Campbell KA, Chen XM, Griffey CA. Identification and mapping of adult plant stripe rust resistance in soft red winter wheat VA00W-38. Crop Sci. 2013;53(3):871–9.

Lan CX, Liang SS, Zhou XC, Zhou G, Lu QL, Xia XC, He ZH. Identification of genomic regions controlling adult-plant stripe rust resistance in Chinese landrace Pingyuan 50 through bulked segregant analysis. Phytopathology. 2010;100(4):313–8.

Case AJ, Naruoka Y, Chen X, Garland-Campbell KA, Zemetra RS, Carter AH. Mapping stripe rust resistance in a Brundage X coda winter wheat recombinant inbred line population. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91758.

Chen XM, Line RF, Jones SS. Chromosomal location of genes for resistance to Puccinia striiformis in winter wheat cultivars Heines VII, Clement, Moro, Tyee, Tres and Daws. Phytopathology. 1995;85(11):75–381.

Lin F, Chen XM. Quantitative trait loci for non-race-specific, high-temperature adult-plant resistance to stripe rust in wheat cultivar express. Theor Appl Genet. 2008;118:631.

Hou L, Dong-Fang MA, Mao-Lin HU, Miao-Miao HE, Yan LU, Jing JX. Genetic analysis and molecular mapping of an all-stage stripe rust resistance gene in Triticum aestivum-Haynaldia villosa translocation line V3. J Integr Agr. 2013;12(12):2197–208.

Melichar JPE, Berry S, Newell C, Maccormack R, Boyd LA. QTL identification and microphenotype characterization of the developmentally regulated yellow rust resistance in the UK wheat cultivar Guardian. Theor Appl Genet. 2008;117:391–9.

Agenbag GM, Pretorius ZA, Boyd LA, Bender CM, Prins R. Identification of adult plant resistance to stripe rust in the wheat cultivar Cappelle-Desprez. Theor Appl Genet. 2012;125:109–20.

Vazquez MD, Peterson CJ, Riera-Lizarazu O, Chen XM, Heesacker A, Ammar K, Crossa J, Mundt CC. Genetic analysis of adult plant, quantitative resistance to stripe rust in wheat cultivar ‘Stephens’ in multi-environment trials. Theor Appl Genet. 2012;124:1–11.

Bulli P, Zhang JL, Chao S, Chen XM, Pumphrey M. Genetic architecture of resistance to stripe rust in a global winter wheat germplasm collection. G3-Genes Genom Genet. 2016;6:2237–53.

Boukhatem N, Baret PV, Mingeot D, Jacquemin JM. Quantitative trait loci for resistance against yellow rust in two wheat-derived recombinant inbred line populations. Theor Appl Genet. 2002;104:111–8.

Yan R, Liu LS, He ZH, Ling W, Xia XC. QTL mapping of adult-plant resistance to stripe rust in a ‘Lumai 21 × Jingshuang 16’ wheat population. Plant Breed. 2015;134(5):501–7.

Zhou XL, Han DJ, Chen XM, Mu JM, Xue WB, Zeng QD, Wang QL, Huang LL, Kang ZS. QTL mapping of adult-plant resistance to stripe rust in wheat line P9897. Euphytica. 2015;205:243–53.

Rosewarne GM, Singh RP, Huertaespino J, Rebetzke GJ. Quantitative trait loci for slow-rusting resistance in wheat to leaf rust and stripe rust identified with multi-environment analysis. Theor Appl Genet. 2008;116:1027–34.

Hao YF, Chen ZB, Wang YY, Dan B, Buck J, Brown-Guedira G, Johnson J. Characterization of a major QTL for adult plant resistance to stripe rust in US soft red winter wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2011;123:1401–11.

Lan CX, Rosewarne GM, Singh RP, Herrera-Foessel SA, Huerta-Espino J, Basnet BR, Zhang YL, Yang EN. QTL characterization of resistance to leaf rust and stripe rust in the spring wheat line francolin#1. Mol Breed. 2014;34:789–803.

Vazquez MD, Zemetra R, Peterson CJ, Chen XM, Heesacker A, Mundt CC. Multi-location wheat stripe rust QTL analysis: genetic background and epistatic interactions. Theor Appl Genet. 2015;128:1307–18.

Rosewarne GM, Singh RP, Huerta-Espino J, Herrera-Foessel SA, Forrest KL, Hayden MJ, Rebetzke GJ. Analysis of leaf and stripe rust severities reveals pathotype changes and multiple minor QTLs associated with resistance in an avocet × Pastor wheat population. Theor Appl Genet. 2012;124:1283–94.

Mallard S, Gaudet D, Aldeia A, Abelard C, Besnard AL, Sourdille P, Dedryver F. Genetic analysis of durable resistance to yellow rust in bread wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2005;110:1401–9.

Lu YM, Lan CX, Liang SS, Zhou XC, Di L, Gang Z, Lu QL, Jing JX, Wang MN, Xia XC. QTL mapping for adult-plant resistance to stripe rust in Italian common wheat cultivars Libellula and Strampelli. Theor Appl Genet. 2009;119:1349–59.

Dracatos PM, Zhang P, Park RF, McIntosh RA, Wellings CR. Complementary resistance genes in wheat selection ‘avocet R’ confer resistance to stripe rust. Theor Appl Genet. 2016;129:65–76.

Krattinger SG, Lagudah ES, Spielmeyer W, Singh RP, Huerta-Espino J, McFadden H, Bossolini E, Selter LL, Keller B. A putative ABC transporter confers durable resistance to multiple fungal pathogens in wheat. Science. 2009;323(5919):1360–3.

Kolmer JA, Singh RP, Garvin FD, Viccars L, William HM, Huerta-Espino J, Ogbonnaya FC, Raman H, Orford S, Bariana HS, Lagudah ES. Analysis of the Lr34/Yr18 rust resistance region in wheat germplasm. Crop Sci. 2008;48(5):1841–52.

Zhou Y, Tang H, Cheng MP, Dankwa KO, Chen ZX, Li ZY, Gao S, Liu YX, Jiang QT, Lan XJ, Pu ZE, Wei YM, Zheng YL, Hickey LT, Wang JR. Genome-wide association study for pre-harvest sprouting resistance in a large germplasm collection of Chinese wheat landraces. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:401.

Wang LM, Zhang ZY, Liu HJ, Xu SC, He MZ, Liu HX, Veisz O, Xin ZY. Identification, gene postulation and molecular tagging of a stripe rust resistance gene in synthetic wheat CI142. Cereal Res Commun. 2009;37:209–15.

Guo Q, Zhang ZJ, Xu YB, Li GH, Feng J, Zhou Y. Quantitative trait loci for high-temperature adult-plant and slow-rusting resistance to Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici in wheat cultivars. Phytopathology. 2008;98(7):803–9.

Liu TG, Peng YL, Chen WQ, Zhang ZY. First detection of virulence in Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici in China to resistance genes Yr24 (=Yr26) present in wheat cultivar Chuanmai 42. Plant Dis. 2010;94(9):1163.

Han DJ, Wang QL, Chen XM, Zeng QD, Wu JH, Xue WB, Zhan GM, Huang LL, Kang ZS. Emerging Yr26-virulent races of Puccinia striiformis f. tritici are threatening wheat production in the Sichuan Basin, China. Plant Dis. 2015;99(6):754–60.

Zhang B, Jai QZ, Huang J, Cao SQ, Sun ZY, Luo HS, Wang XM, Jin SL. Trends and toxicity analysis of new strains G22-9 and G22-14 in Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici. Acta Agriculturae Boreali Occidentalis Sinica. 2015;24:125–30.

Wu JH, Wang QL, Chen XM, Wang MJ, Mu JM, Lv XN, Huang LL, Han DJ, Kang ZS. Stripe rust resistance in wheat breeding lines developed for Central Shaanxi, an overwintering region for Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici in China. Can J Plant Pathol. 2016;38(3):317–24.

Yao Q, Wang JR, Yan M, Zhan GM, Huang LL, Kang ZS. Virulence and genotypic diversity of wheat stripe rust races CYR32 and CYR33 in China. J Plant Prot. 2018;45:46–52.

Cao SQ, Wang XM, Jia QZ, Sun ZY, Luo HS, Zhang B, Zhang J, Jin MA, Wang WJ, Jin SL. Evaluation of resistance to stripe rust in wheat varieties (lines) during 2003-2013 in Longnan region, Gansu province. J Plant Genet Resour. 2017;18:253–60.

Bariana HS, Mcintosh RA. Cytogenetic studies in wheat. XV. Location of rust resistance genes in VPM1 and their genetic linkage with other disease resistance genes in chromosome 2A. Genome. 1993;36:476–82.

Das MK, Rajaram S, Mundt CC, Kronstad WE. Inheritance of slow-rusting resistance to leaf rust in wheat. Crop Sci. 1992;32(6):1452–6.

Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67(1):76465.

Meng L, Li HH, Zhang LY, Wang JK. QTL IciMapping: integrated software for genetic linkage map construction and quantitative trait locus mapping in biparental populations. Crop J. 2015;3:269–83.

Smith SE, Kuehl RO, Ray IM, Hui R, Soleri D. Evaluation of simple methods for estimating broad-sense heritability in stands of randomly planted genotypes. Crop Sci. 1998;38(5):1125–9.

Saghai-Maroof MA, Soliman KM, Jorgensen RA, Allard R. Ribosomal DNA spacer-length polymorphisms in barley: Mendelian inheritance, chromosomal location and population dynamics. P Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81(24):8014–8.

Röder MS, Korzun V, Wendehake K, Plaschke J, Tixier M, Leroy P, Ganal MW. A microsatellite map of wheat. Genetics. 1998;149(4):2007–23.

Peng JH, Fahima T, Röder MS, Huang QY, Dahan A, Li YC, Grama A, Nevo E. High-density molecular map of chromosome region harboring stripe-rust resistance genes YrH52 and Yr15 derived from wild emmer wheat, Triticum dicoccoides. Genetica. 2000;109:199–210.

Suenaga K, Singh RP, Huerta-Espino J, William HM. Microsatellite markers for genes Lr34/Yr18 and other quantitative trait loci for leaf rust and stripe rust resistance in bread wheat. Phytopathology. 2003;93(7):881–90.

Li GQ, Li ZF, Yang WY, Zhang Y, He ZH, Xu SC, Singh RP, Qu YY, Xia XC. Molecular mapping of stripe rust resistance gene YrCH42 in Chinese wheat cultivar Chuanmai 42 and its allelism with Yr24 and Yr26. Theor Appl Genet. 2006;112:1434–40.

Bassam BJ, Caetano-Anollés G. Silver staining of DNA in polyacrylamide gels. Appl Biochem Biotech. 1993;42:181–8.

Liu YX, Lin Y, Gao S, Li ZY, Ma J, Deng M, Chen GY, Wei YM, Zheng YL. A genome-wide association study of 23 agronomic traits in Chinese wheat landraces. Plant J. 2017;91:861–73.

Botstein D. Construction genetic linkage map in man using restriction fragment length polymorphisms. Am J Hum Genet. 1980;32(3):314–31.

Liu K, Muse SV. PowerMarker: an integrated analysis environment for genetic marker analysis. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(9):2128–9.

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–59.

Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol Ecol. 2005;14(8):2611–20.

Bradbury PJ, Zhang Z, Kroon DE, Casstevens TM, Ramdoss Y, Buckler ES. TASSEL: software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(19):2633–5.

Turner SD. Qqman: an R package for visualizing GWAS results using Q-Q and Manhattan plots. bioRxiv. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1101/005165.

Valluru R, Reynolds MP, Davies WJ, Sukumaran S. Phenotypic and genome wide association analysis of spike ethylene in diverse wheat genotypes under heat stress. New Phytol. 2017;214(1):271–83.

Chen XM, Kang ZS. Introduction: history of research, symptoms, taxonomy of the pathogen, host range, distribution and impact of stripe rust. In: Chen XM, Kang ZS, editors. Stripe rust. Dordrecht: Springer; 2017. p. 1–33.

Cheng YK, Yao FJ, Ye XL, Jiang QT, Li W, Deng M, Wei YM, Chen GY. Construction of linkage map of the meta quantitative trait loci (MQTL) on stripe rust resistance in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Acta Phytopathologica Sinica. 2019;49(5):632–49.

IWGSC. Shifting the limits in wheat research and breeding using a fully annotated reference genome. Science. 2018;361:eaar7191.

Maccaferri M, Ricci A, Salvi S, Milner SG, Tuberosa R. A high-density, SNP-based consensus map of tetraploid wheat as a bridge to integrate durum and bread wheat genomics and breeding. Plant Biotechnol J. 2015;13:648–63.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. Qiu-Zhen Jia (Plant Protection Research Institute, Gansu Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Lanzhou, P. R. China) for providing the stripe rust races, and the support from Prof. Li-Hui Li and Xiu-Quan Li (Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences) for plant materials.

Funding

This work was supported by the projects from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0102000, 2016YFD0100100, 2017YFD0100900), the International Science and Technology Cooperation and Exchanges Programs of Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province (2019YFH0063), and the Major Science and Technology Projects in Sichuan Province, China (2018NZDZX002). The funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or in the writing of the report or decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YW1 analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript; CY carried out the experiment, YC carried out the analyses of association mapping and optimized these styles for charts; FY, LL, YW2, JL and HL carried out the phenotypic evaluation; JW contributed to manage plant materials and provided the DArT-seq genotype; QJ, WL, ZP, PQ, JM, MD, YW3 and XC participated in the field experiment; GC, HK, YJ and YZ designed and carried out the experiment, formulated the questions, analysed the data and revised the manuscript. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

143 wheat landraces used in this study and the infection type (IT) in the seedling stage for CYR32 and CYR34 and IT, final disease severity (FDS) and area under the disease progress curve (AUDPC) in the adult-plant stages among five environments.

Additional file 2.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients for infection type (IT), final disease severity (FDS) and area under the disease progress curve (AUDPC) against stripe rust evaluated among five environments during 2016 to 2018. Different environments were all correlated, Significant at P < 0.01.

Additional file 3.

Population structure of 143 wheat landrace accessions in Southern Autumn-Sown Spring Wheat Zone of China. (a) The population structure of 143 accessions with Bayesian clustering analysis. Two colors stand for 2 different compositions. The Subgroup 1 (Gp1) mainly showed as red color. The Subgroup 2 (Gp2) mainly showed as green color; (b) Estimated the distance of hierarchical clustering for the accessions using Fast Ward grouping algorithm and heat map showing the kinship and phylogenetic relations.

Additional file 4.

Genome-wide average linkage disequilibrium (LD) decay plot for 143 wheat landraces based on 5899 DArT markers. The scatter plots showing pairwise DArT markers LD r2 value as a function of inter-marker genetic distances (cM).

Additional file 5.

The position of the potentially novel QTL and details of reported QTL and Yr genes located on the integrated map.

Additional file 6.

The avirulence(A) /virulence(V) formula of the Pst races used in this study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Yu, C., Cheng, Y. et al. Genome-wide association mapping reveals potential novel loci controlling stripe rust resistance in a Chinese wheat landrace diversity panel from the southern autumn-sown spring wheat zone. BMC Genomics 22, 34 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-020-07331-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-020-07331-1