Abstract

This literature review evaluates the development and impact of analytical tax research (ATR) from 2000 until 2022. Based on 345 research papers, we (1) identify emerging and declining research topics in the area of ATR, (2) examine the trends in publication outlets and author teams, and (3) analyze citation metrics at both the level of articles and authors to measure perception and impact of ATR. First, we find that rather new topics, such as the impact of taxation on entrepreneurship, innovation and R&D, have begun to attract attention. Second, tax journals are not the preferred outlet for ATR and author teams exhibit a decreasing gender imbalance. Third, citation metrics are highly centered on specific publications and individual authors. Moreover, publications that appeared in economics and finance journals generate disproportionately large citation numbers compared to those that were published in tax, accounting and business research journals. Authors from Anglo-American institutions have significantly more citations than researchers from German-speaking countries. We find that ATR does not form a closed community. It unites researchers from different backgrounds based on their— sometimes nonrecurring—thematic interest in the effects of taxation on economic decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Analytical tax research (ATR) has been a traditional strength of German and Austrian business tax research (BTR).Footnote 1 Since the 1960s, German-speaking academics have used formal mathematical models to discover or examine various tax effects, especially on investment and financing decisions.Footnote 2 As most of their studies were written and published in German until the 1990s, BTR had remained largely separate from the international tax research community before then.Footnote 3 However, the discipline has been subject to the growing importance of publishing internationally during the past two decades.

This literature review analyzes how ATR in particular has developed during this period, and how large its impact has been. We examine ATR from a meta-perspective to identify current developments, citation patterns, and emerging and declining trends in a changing research environment. This systematic overview of ATR studies enables us to pinpoint avenues for future research and assess the potentials for their success. Specifically, we investigate the overall quantity of research output and research topics in ATR (Sects. 3 and 4), the key characteristics of the analytical models (Sect. 4), the development of ATR since 2000 (Sect. 5), the impact of publications (Sect. 6) and the impact of individual researchers, both measured by their respective citations (Sect. 7).

Earlier reviews of tax literature (Hundsdoerfer et al. 2008a for a comprehensive review of the German BTR literature) often focus on empirical research (e.g., Shackelford and Shevlin 2001; Hanlon and Heitzman 2010). Some examine a clearly defined set of research questions (e.g., Lietz 2013 for tax avoidance; Bauer et al. 2018 for principal-agent models with taxes; Wilde and Wilson 2018 for corporate tax planning; Sawyer and Tan 2020 for tax research in New Zealand; Jacob 2022 for empirical studies on real effects of taxation); others focus on specific journals without any methodological or topical restrictions (e.g., Betting and Wagner 2013; Ertel 2017). However, findings in empirical tax research do not automatically embrace findings in ATR. Analytical and empirical tax research differ from one another in numerous ways. Foremost, each one employs different methods and addresses different audiences outside academia. Model-based tax research deals with the decision-making of both individual and corporate taxpayers and legislators; empirical tax research primarily informs tax authorities on the consequences of certain taxes and evaluates these consequences for affected taxpayers (Wagner 2022). Our literature review enhances the understanding of BTR by a distinct examination of the focus and impact of ATR since 2000 under a special consideration of German contributions. Its insights are useful for established analytical tax researchers, empirical tax researchers and junior researchers. For established analytical tax researchers, this review provides insights in the development of their discipline. For empirical tax researchers, it helps to learn about research topics that have reliable theoretical underpinnings and might deserve additional empirical evaluation. For junior researchers, it identifies starting points for their own research and encourages them to evaluate their potential future success.

The goal of our literature review is to document the development of ATR over time and analyze its academic perception and its boundaries—under special consideration of the development of German contributions. Thus, our review focuses on analytical, i.e. model-based, tax research in both domestic and international journals and is not limited to specific research questions or topics. Our review comprises 345 publications in ATR from 2000 to 2022. While the overall number of publications seems rather small for a period of almost 23 years, the observation that analytical research represents only a minor proportion of total research output is congruent with other disciplines. For example, in audit research only 2.2% of all publications rely on analytical research methods (Köhler and Ma 2018).

All the analyses in the 345 publications use formal models. None of these papers is primarily empirical or normative, or has a sole economics or finance focus. We explain the sample selection process in detail in Sect. 2. Despite the restrictions with regard to the primary research focus, we find that publications that investigate taxation and its link to investment and financing decisions (still) constitute the major topic in ATR, with 26.1% (finance) and 19.7% (investment) of all 345 studies. Apart from this observation, the topics in ATR are partly novel and for sure diverse—they comprise research on personnel planning, tax neutrality, transfer prices, pensions, and the role of advisors amongst others. Overall, the developments in ATR follow Shackelford and Shevlin’s (2001:324) observation for empirical tax research: “Instead of a trunk with major branches, the tax literature grew like a wild bush, springing in many directions.”

We present three major observations in the discipline of ATR itself between 2000 and 2022. First, tax journals are not the preferred outlet for ATR articles, which tend to appear in business and economics journals—even though no study in our review has a pure economics focus. Second, English as publication language has become dominant over German since 2010, whereas both languages have been on par before. Third, author teams are increasingly gender balanced. However, the majority of research teams remains purely male.

In line with other citation studies (e.g., Brown and Gardner 1985; Lindquist and Smith 2009), we find that the distributions of citations per publication and per author are highly right-skewed, meaning that a few publications drive the overall impact of ATR. The top 20 papers, less than 6% of all 345 publications in our review, account for up to three quarters of all citations, depending on the citation database. In contrast, about half of all ATR publications are hardly ever cited (or are not included in the relevant citation databases). Along the same lines, the citation numbers are highly researcher-centered. Depending on the database, up to 65% of all citations as measured at the author level are attributable to the 25 most frequently cited researchers. Those authors constitute only roughly 6% of all authors in our review and are not associated with German-speaking institutions for the most part.Footnote 4 We suspect that German-speaking researchers in ATR do not follow a culture of mutual citations, keeping their measurable impact in the—even national—scientific community low. Moreover, their research often informs practitioners, who use the knowledge, but of course do not generate citations.

Overall, ATR publications are very heterogeneous apart from their common research method. Fragmented ATR communities in accounting, business research, economics, and finance have limited overlap. So far, BTR has only partly integrated into the different international communities. One reason is that analyses of a national tax law—while important from a domestic perspective—are often of limited interest and accessibility to an international audience. We conclude that ATR makes important contributions for audiences also outside the scientific community, can provide theoretical foundation for empirical tax research, but does not constitute a closed community, as also authors who are primarily economists, or finance or accounting researchers contribute to ATR.

The paper proceeds as follows: Sect. 2 describes the methodology of our literature review. Section 3 outlines the research areas in ATR. Section 4 explains their specific research focus and respective model characteristics. Section 5 extends the overview by a quantitative analysis on the development of ATR. Section 6 analyzes the citations of ATR papers. Section 7 examines the citations of individual authors and identifies their common characteristics. Section 8 pinpoints promising avenues for future research. Section 9 summarizes and concludes.

2 Methodology

2.1 Approach

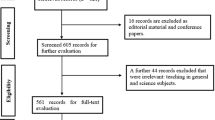

We identified the relevant literature for our literature review in a multi-step approach. First, we determined the scope of our search. We enclosed years from 2000 onwards to, first, give an extensive and comprehensive, yet still manageable overview of ATR and, second, capture rather new developments in ATR since the turn of the millennium. To establish an external benchmark for the papers’ quality, we considered published articles only and excluded working papers. For the selection of journals, we followed the VHB-Jourqual3 in the area of taxation (WK STEU). The VHB-Jourqual3 was published by the German Academic Association for Business Research (VHB)Footnote 5 in 2015. It ranks German and international scientific business and economics journals by means of letters (A + down to D). We included all 57 journals with a C-rating or higher from the list and we excluded all D-rated journals to ensure focus on research-centered articles. Additionally, we included 11 high-quality journals without a ranking (no ranking “n.r.”) that were mentioned in the VHB-Jourqual3 rating, but rated by only a few researchers.Footnote 6 Furthermore, we extended the list of journals by 15 more magazines from the area of general business administration (ABWL) and three from the area of accounting (WK RECH), which have featured tax-related articles previously. Supplemental material 1 shows a list of all potentially relevant journals.

We decided to use the Scopus database for an automated search request, since it covers most of the potentially relevant journals.Footnote 7 The Scopus search request, which we provide as supplemental material 2 in the Appendix, resulted in 1,776 search hits. To the best of our knowledge, neither Scopus, nor any other publications database, allows for the pre-filtering of articles by research method. Therefore, we manually sorted out all articles, which primarily apply non-analytical research methods, i.e., archival-empirical, experimental and normative methods, or have their main emphasis on economics topics, e.g., considerations about welfare, general equilibria and tax competition. For those journals that Scopus does not cover or only covers for specific years, we manually went through all respective annual tables of contents to detect ATR-publications (1,748 pages in total). We provide the list of all journals that include ATR articles that are part of our literature review as supplemental material 2 in the Appendix.

Our final set of publication includes 345 articles. Table 1 summarizes the selection process.

2.2 Limitations

Each step of the literature selection process requires decisions that can appear somewhat arbitrary. Our fundamental choice to use the VHB-Jourqual3 can be contestable, as the rating comprises also domestic journals and does not necessarily reflect the international relevance of the journals. However, the choice corresponds to our aims to assess the development of German ATR and evaluate its integration into international research communities. Hence, the wide coverage of the VHB-Jourqual3 seems helpful for our research purposes.

Our next basic decision is to cut the inclusion of journals at a C-rating in the VHB-Jourqual3. C-journals are “renowned scientific journals” according to VHB (2022). Furthermore, we viewed journals, which are linked to tax research (WK STEU), but not formally rated (see supplemental material 1 in the Appendix), as relevant for our analyses, since the lack of a formal rating is only due to a low respondent number, not due to a practitioner-focus. In contrast, D-journals—although classified as “scientific journals”—are typically practitioner-oriented without a rigorous review process. Thus, the cutoff at a C-rating reflects the focus of our review on academic ATR. In our sample, only nine articles appeared in journals without a rating. Due to the low number of articles without a rating, a possible impact on the overall sample quality is negligible. At the same time, some highly respected journals are not included in the VHB-Jourqual3 ranking and therefore not part of our review. Examples are Quarterly Journal of Economics, Review of Economic Studies, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Foundations and Trends in Accounting, Journal of Law, Finance and Accounting or Plos one. However, the number of ATR articles excluded due to this limitation should be small, since the journals put their focus on finance and economics research, which is not part of our review.

Next, we turn to the implementation and execution of our search for relevant literature. For the automated search in Scopus, we used keywords to narrow down the initial search result of more than 91,000 articles. Given that our keyword list (see supplemental material 2 in the Appendix) is quite extensive, the number of ignored publications should be small. However, first, for some journals Scopus exhibits gaps for several volumes; second, Scopus does not cover some of the relevant—mainly German—journals at all (see supplemental material 1 in the Appendix). In these cases, we compensated gaps in the database by means of hand-collection. Since such a manual search might be superior to an automated search, we expect German papers (with domestic focus) to be slightly overrepresented in our review. With regard to the citation analyses, the gaps in Scopus coverage prevented us from conducting an automated comprehensive cross-citation analysis that is applied in some bibliometric studies as citation information is obviously missing in parts.Footnote 8

Furthermore, no commonly used database offers to restrict the search of publications to certain research methods.Footnote 9 Thus, we had to scrutinize the employed research methods of the publication manually. If a study used analytical and empirical methods equally, we still included it.Footnote 10 For international journals, such an assessment was relevant occasionally. For some German journals (especially for Betriebswirtschaftliche Forschung und Praxis, BFuP, and Steuer und Wirtschaft, StuW), we had to define which type of calculus counts as a formal model. We did not count simple numerical examples, simulations or present value calculations as models and rather required a minimum level of analytical abstraction. When in doubt, we included the publication, so that, again, German journals can be overrepresented in our study. In the vast majority of cases, the categorization is unambiguous. However, we do not claim total objectivity.

Moreover, we are aware that the separation of public economics and BTR is ambiguous. However, some topics do not belong to BTR in general, such as tax competition, regulatory competition, general equilibrium models, welfare analyses, optimal taxation or tax incidence. We used the respective keywords in our search strategy to exclude economics papers that deal with these topics (see supplemental material 2 in the Appendix). Applying the four-eye-principle, we manually checked each paper on its research method and topic and eliminated it if it clearly belonged to the economics literature in our view. Again, we do not claim total objectivity and cannot exclude that other researchers would come to different conclusions in some (rare) cases, but tried to work as rigorous as possible.

3 Classification of topics in analytical tax research

To organize the papers in our literature review, we follow Wagner’s (2004) thoughts on the distinction of tax research with regard to its general topics and examined questions (Fig. 1). We categorize the publications by means of their research topic to allow a precise, but not overwhelmingly detailed classification. It enables us to document areas of interest and pinpoint promising paths for further investigation. Again, we want to emphasize that only published papers constitute the basis for our analysis. Their number is a function of research activity and serves as a proxy for current interest of journals, readers, and authors.

In Sect. 4, we give an overview of the papers in our review in relation to their main research topic. As visualized in Fig. 1, the main research topics comprise issues of (4.1) tax avoidance, tax evasion or profit shifting, (4.2) transfer prices, (4.3) repatriation, (4.4) the choice of legal form for a company, (4.5) personnel planning in a company, (4.6) pensions and provisions, (4.7) the role of tax advisors, (4.8) entrepreneurship, innovation and research and development (R&D), (4.9) tax neutrality, (4.10) tax burden, (4.11) private decisions, (4.12) finance or (4.13) investment. Table 2 summarizes the number of publications in each main categories, broken down by two full decades (2000 to 2009; 2010 to 2019) and the currently ongoing decade (2020 and onwards). We are aware that the current decade has only started in 2020, so final assessments for the current decade would be premature.

As a caveat, the categorization of research topics is subject to opinions. The reader might prefer a more or less detailed classification or even different categories. Whenever a paper covers more than one category, we assigned it in accordance with our view of the paper’s focus. We concede that readers can disagree with our perception.

In contrast to empirical tax research (Jacob 2022), finance- and investment-related analyses are a major research area in ATR from 2000 to 2022 (jointly 158 papers or 45.8% of all papers). In the subsequent places follow considerations about tax avoidance, tax evasion and profit shifting (16.2%), tax neutrality (7.5%), tax burdens (7.5%), personnel planning (6.4%), and transfer prices (4.6%). Figure 2 depicts the publishing activity in the different research topics throughout the last 23 years and highlights several shifts.

Whereas ATR on the role of tax advisors had already attracted some interest in the 1990s (Klepper et al. 1991; Melumad et al. 1994; Beck et al. 1996; Phillips and Sansing 1998), this area appears under-investigated with only three papers in our sample. Analyses of innovation-related topics (i.e., entrepreneurship, innovation and R&D) recently increased in popularity (11 papers). In contrast, publications on the topics of repatriation and choice of legal form for companies remain on a stable, but low level. Analytical research on tax avoidance and on tax evasion and profit shifting remain evergreen topics.

Figure 3 excludes the two dominant areas of finance- and investment-related ATR, thereby highlighting the importance of analytical research on tax avoidance, evasion and profit shifting.

Overall, about 92% of all papers in our review examine some form of income or profit tax. Apart from profit taxes, inheritance taxes play a (minor) role. A few articles consider wealth-related taxes in addition or as an alternative to profit taxes (e.g. Sureth and Maiterth 2008; Diller et al. 2015; Niemann and Sureth-Sloane 2019; Bjerksund and Schjelderup 2021). One paper in the review analyses the consequences of a tobacco tax, another paper also takes the value-added tax into account, but other types of taxes do not seem to attract researchers’ attention.

4 Overview on the topics in analytical tax research

In this section, we give an overview of the papers within each research area and summarize the related key figures. The key figures comprise the ratings of the journals, in which the publications appeared, and the characteristics of the models in the respective analyses, i.e., the number of periods, the underlying probability assumptions (deterministic or stochastic models) and the territorial scope (domestic versus cross-border). Table 3 presents a summary.

4.1 Tax avoidance, tax evasion and profit shifting

ATR on tax avoidance, tax evasion and profit shifting evolves around the question how and under which circumstances both companies and individuals (can) minimize their tax burden. The works of Hines (2004), Desai and Dharmapala (2006), Jacob et al. (2021) examine the determinants of tax avoidance or the related governmental reactions. While the aforementioned analyses focus on firms, considerations about the minimization of inheritance tax center on individuals (Jansen and Gröning 2003; Nordblom and Ohlsson 2006; Jansen 2007; Kundisch et al. 2007; Diller 2008a; Diller and Kittl 2016; Diller et al. 2019, 2021). Yim (2009) evaluates the most efficient usage of an audit budget from an inspector’s perspective.

In contrast to studies on tax avoidance, examinations of tax evasion usually integrate the possibility for the government to sanction taxpayers. The topic of tax evasion comprises publications that examine circumstances and facilitation of tax evasion and potential connections between tax compliance and governmental audits (Mills and Sansing 2000; Feltham and Paquette 2002; Crocker and Slemrod 2005; Snow and Warren 2005; Bayer 2006; Goerke 2007; Bayer and Cowell 2009; Diller et al. 2013; Lee 2015; Levaggi and Menoncin 2016; Immordino and Russo 2017; Di Gioacchino and Fichera 2020). Furthermore, these analyses examine the role of firm characteristics (Lee 2001; Çule and Fulton 2009), joint tax evasion (Boadway et al. 2002), firm investments (Baumann and Friehe 2010), uncertainty (Caballé and Panadés 2005; Bernasconi et al. 2015; Diller and Lorenz 2015; Bag and Wang 2021), interaction and coordination among taxpayers (Bernasconi and Zanardi 2004; Garay et al. 2012; Sanchez 2015) and targeted audits (Levaggi and Menoncin 2012; Lipatov 2012; Phillips 2014; Hashimzade et al. 2016). Other works focus on the impact of the underground economy (Blackburn et al. 2012) or corruptibility (Cerqueti and Coppier 2015).

The topic of profit shifting and minimization of reported profits for tax purposes is of interest in ATR (Hundsdoerfer 2000; Gallmeyer et al. 2006; Klassen and Sansing 2006; Schreiber 2009; Dietrich and Kiesewetter 2011; Schmidtmann 2012; Freidank 2016; Gresik 2016; Kiesewetter et al. 2018; Bloch and Demange 2021), also with regard to the usage of transfer prices in profit shifting (Gresik and Osmundsen 2008; Halperin and Srinidhi 2010; Autrey and Bova 2012). Furthermore, Yoon (2000) analyses the role of litigation cost reimbursement rules on the number of settlements in cases on aggressive corporate tax reports, De Simone et al. (2013) evaluate the potential of cooperative tax-compliance programs and Bachmann et al. (2016a) examine the link between R&D offshoring and tax incentives.

Of the 56 articles in this area, 20 appeared in A + or A-rated journals. Of the remaining 36 papers, 26 were published in B, seven in C-journals, three in journals without rating.Footnote 11 25 of the models are multi-period. 33 of the models are stochastic and 10 work with cross-border or international setups. In 25 of the models, the government acts a strategic player in a tax compliance game.

4.2 Transfer prices

The analytical research area of transfer prices has attracted constant interest throughout the last decades. In parts, it is closely related to the topic of tax avoidance and profit shifting (Sansing 2001; Hyde and Choe 2005; Kari and Ylä-Liedenpohja 2005; De Waegenaere et al. 2006; Kiesewetter and Mugler 2007; Mammen 2011; Martini et al. 2012; Dürr and Göx 2013; Afik and Lahav 2016; Große 2018; Juranek et al. 2018; Reineke et al. 2022), but puts the transfer pricing itself into the research focus. Other examinations put their focus on the link between tax minimizing transfer prices and organizational structures (Narayanan and Smith 2000; Martini 2015; Löffler 2019; Reineke and Weiskirchner-Merten 2021).

Eight of all 16 articles appeared in A + or A-, four in B- and three in C-rated journals. Inherent to the topic, the vast majority of papers examines international settings. Eleven of 16 models span one period, nine are stochastic and two integrate the government as strategic player.

4.3 Repatriation

Only five articles (Altshuler and Grubert 2002; Dodonova and Khoroshilov 2007; De Waegenaere and Sansing 2008; Stiller 2013; Klassen et al. 2014) cover the topic of profit repatriation and related tax considerations. The number of publications might be so small as the topic is often bound to a U.S.-context that does not necessarily translate to other settings.

Two of the papers were published in A-journals, two in B-journals and one in a C-journal. All models consider timelines with at least two periods and, of course, refer to international settings. Two of the models use a probability distribution, none integrates a strategic governmental player.

4.4 Choice of legal form

Similar to the area of profit repatriation, ATR on the impact of taxation on the choice of companies’ legal forms attracts less interest currently. Most papers have an Austrian or German tax law background. The topic is wide and can relate to considerations about organizational form and international tax allocation mechanisms. However, it puts its research emphasis on the tax-minimizing design of company structures (Husmann and Strauch 2006; Eberhartinger and Pummerer 2007; Müller et al. 2010; Kudert et al. 2015; Blaufus et al. 2015; Scheffler and Zausig 2017) or evaluates this design (Müller and Semmler 2003).

Of all seven articles that cover the topic, five appeared in B-journals and two in C-journals. The ranking of the outlets reflects that this topic typically has a national tax law background, which might not be of interest for highly-ranked journals that demand generalizability of results. Four models use one-period settings, five are deterministic and three consider cross-border settings.

4.5 Personnel planning

The research topic of personnel planning deals with questions about employment, motivation and compensation of firm managers and the related impact of taxes. Agency conflicts in this context already received attention in the literature review by Bauer et al. (2018). In contrast to our review, the review by Bauer et al. (2018) also featured publications before 2000 and working papers. Amongst other works, their literature review covers papers by Halperin et al. (2001), Niemann and Simons (2003), Niemann (2008), Göx (2008), Radulescu (2012), Voßmerbäumer (2012, 2013), Dietl et al. (2013), Martini and Niemann (2015), Meißner et al. (2014), Martini et al. (2016) and Krenn (2017). Publications by Niemann (2007), Ewert and Niemann (2012) and Schneider et al. (2021) are related to the topic of agency conflicts and taxation, but not part of the literature review by Bauer et al. (2018). Furthermore, ATR on personnel planning can comprise very specific considerations about motivation, e.g. the usage of work time accounts (Wellisch 2003a) or equity-based compensation (Widdicks and Zhao 2014). Furthermore, it evaluates (tax) optimal implementation of different compensation types, such as options (Simons 2000, 2001) or fringe benefits (Voßmerbäumer 2010), and examines country- or industry-specific effects (Pummerer and Steller 2016; Kroh and Weber 2016).

Of the 22 articles on personnel planning, four were published in A-, 16 in B-, and two in C-journals. Characteristic for principal-agent models, the great majority of the models, 17 of 22, makes single-period considerations, and is of stochastic nature with, again, 17 articles. Models in 19 articles use domestic settings.

4.6 Pensions and provisions

The category of tax-related considerations about pensions and provisions comprises ten publications—all of which are German (Brassat and Kiesewetter 2003; Wellisch 2003b; Wrede 2003; Wellisch and Machill 2007; Blaufus and Eichfelder 2008; Schönemann et al. 2009; Suttner and Wiegard 2012; Scheffler 2016; Schätz-lein 2020; Gamm et al. 2020).

Seven of the papers appeared in B-journals, two in C-journals, one in a journal without a formal rating. Nine of the related ten models span more than one period, also nine are deterministic, and, again, nine have a domestic focus on Germany as their country of interest.

4.7 Role of tax advisors

All three papers on the role of tax advisors (Elitzur and Yaari 2021; Konrad 2021; Kaçamak 2022) were published during the last two years, two of them in B-journals. The topic seems to experience a revival in interest after the 1990s (Klepper et al. 1991; Melumad et al. 1994; Beck et al. 1996; Phillips and Sansing 1998), and accounts for a noticeable share in ATR publications in the 2020s of 12% (3 of 25 papers).

Two models are single-period; two are stochastic; all refer to national settings. The role of tax advisors is the only research area in which a majority of papers (two out of three) models the fiscal authorities as a strategic player.

4.8 Entrepreneurship, innovation, and R&D

Publications in the area of ATR on entrepreneurship, innovation and R&D tackle questions about entrepreneurial activity (Haufler et al. 2014; Fossen et al. 2020), investments in innovation (Williams et al. 2001; Bachmann and Baumann 2013; Haufler et al. 2014; d’Andria 2016; d’Andria 2019; Rupp 2020; Boadway et al. 2021) and R&D (McKenzie 2008; De Waegenaere et al. 2012, 2021).

One paper appeared in a journal with A + rating, two papers in A-, six in B-, and two in C-journals. Six of the related models cover more than one period, six are deterministic and seven evolve around a domestic setting.

4.9 Tax neutrality

Considerations about tax neutrality have been popular among mostly German-speaking researchers—also before the starting year of our literature review. Neutrality considerations can refer to inheritance taxation (Hiller 2001), pension taxation (Kiesewetter and Niemann 2002, 2003; Fuest and Brügelmann 2003), or shareholder taxation (König and Wosnitza 2000; Jacob 2009; Lindhe and Södersten 2012). Furthermore, tax neutrality papers deal with the impact of corporate taxation on investment decisions (Heinhold et al. 2000; König and Sureth 2002; Ruf 2004; Husmann 2007; Diller and Grottke 2010; Kanniainen and Panteghini 2013; Schreiber 2013; Hemmerich and Kiesewetter 2014; Schreiber and Stiller 2014), financing decisions (Maiterth and Sureth 2006; Kubota and Takehara 2007; Blaufus and Hundsdoerfer 2008; Rumpf 2009; Ruf 2010; Ott 2013). Furthermore, Knirsch (2007) proposes a theory-based measure for decision distortions caused by taxation. Although German authors dominate the topic in our literature review, tax neutrality seems to have gained a little more attention from non-German researchers recently (Bond and Devereux 2003; Hebous and Klemm 2020; Södersten 2020).

Only one of the 26 articles was published in an A-journal, but 21 in B- and 4 in C-journals. Since the top-rated journals only publish in English, a reason for the very low share of publications in top-rated (A + and A) journals lies in the German language that 15 of the articles in this topic use.

In 20 models, the authors use multi-period settings. Again, 20 models are deterministic and 21 models refer to domestic settings.

4.10 Tax burden

Examinations of tax burdens in ATR comprises the broad range of publications that evaluate the (monetary) costs that come with a specific tax or the related accounting methods from a taxpayers’ perspective. “Tax burden” does not refer to tax incidence, which we regard as an economics topic. Some articles investigate inheritance tax burdens (Brähler and Hoffmann 2011; Simons et al. 2012; Franke et al. 2016), other examine corporate tax burdens (Schreiber et al. 2002; Maiterth 2003; Eichfelder 2011; Müller et al. 2011; Ruf 2011; Musumeci and Sansing 2014)—especially with regard to the Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base “CCCTB” (Pummerer and Steckel 2005; Schreiber and Führich 2009; Ortmann and Sureth-Sloane 2016) or losses (Brähler et al. 2009; Becker and Steinhoff 2014). Moreover, three articles examine the effect of timing decisions (Panteghini 2004; Bachmann et al. 2016b; Kiesewetter and Schätzlein 2019). Furthermore, a noticeable share of examinations deals with individuals’ tax burdens (Knobloch and Rümmele 2005; Diller 2006; Hechtner 2011; Diller et al. 2015; Glowienka 2015; Gandhi and Kuehlwein 2016; Fritz-Schmied et al. 2019). One article examines the effect of a tobacco tax on smuggling (Delipalla 2009) and one the effect of loss-offset restrictions on risk sharing (Djanani and Pummerer 2004).

Of all 26 articles, 21 were published in B-journals and five in C-journals, none in a top-rated journal. Similar to the ATR on tax neutrality—the vast majority of articles is written in German. Overall, 18 models are deterministic and 18 cover more than one period. Slightly more than 80% (21 of 26) of the models evaluate domestic settings.

4.11 Private decisions

The research area of private decisions in ATR covers all articles that concern the private life of individuals with regard to tax-related effects. Barigozzi et al. (2019) and Creedy and Gemmell (2020) evaluate how personal decisions are related to the tax assessment of (married) couples. Milligan (2003) examines how contribution limits affect savings in tax-preferred accounts. Desai et al. (2007) and Galmarini et al. (2013) deal with theft and related condemnation of individuals under different tax conditions.

One of the five articles was published in an A + -rated journal, another one in an A-journal, two in B-journals, one article appeared in a journal without rating. Three of the models are deterministic; three make single-period considerations; all models have domestic settings.

4.12 Finance

The area of finance-related articles constitutes the biggest topic in ATR, accounting for slightly more than 26% of all ATR publications from 2000 to 2022 according to our literature review. The topic can be divided into the subcategories “firm and asset valuation”, “valuation of tax shields”, “evaluation of tax burdens in firm valuation”, “choice of financial instruments” and “timing considerations”.

35 analyses concern firm and asset valuations (Scheffler 2001, 2014; Bogner et al. 2002; Harris et al. 2001; Husmann et al. 2002, 2006; Lund 2002, 2014; De Waegenaere et al. 2003; Jonas et al. 2004; Kiesewetter and Lachmund 2004; Richter 2004; Streitferdt 2004, 2010; Laas 2006; Rapp 2006; Schultze and Zimmermann 2006; Bachmann and Schultze 2007; Gröger 2007; Schultze and Dinh Thi 2007; Wilhelm and Schosser 2007; Hundsdoerfer et al. 2008b; Muche 2008; Bauer et al. 2009; Eikseth and Lindset 2009; Kruschwitz and Löffler 2009; Piehler and Schwetz-ler 2010; Diller 2012; Schosser 2012; Diedrich 2013; Realdon 2013; Li et al. 2016; Dierkes and Schäfer 2017; Krause 2018, 2019; Bjerksund and Schjelderup 2021; Goldbach et al. 2021).

Twenty-one publications deal with tax shields and their valuation (Fernandez 2004; Schultze 2005; Cooper and Nyborg 2006; Bachmann and Schultze 2008; Mai 2008; Eberl 2009; Förster et al. 2009; Liu 2009; Scholze 2010; Rauch et al. 2010; Watrin and Stöver 2011; Bachmann and Schultze 2011; Qi 2011; Brähler and Kühner 2012; Couch et al. 2012; Maßbaum et al. 2012; Streidtferdt 2013; Lampenius and Buerkle 2014; Krause and Lahmann 2016; Arnold et al. 2008; Kruschwitz and Löffler 2018). Twelve publications evaluate tax burdens in firm valuation (Eggert and Weichenrieder 2002; Kämpf 2003; Bogner et al. 2004; Gordon 2010; Menoncin and Panteghini 2010; Laitenberger 2003; Krapp and Wotschofsky 2004; Kruschwitz and Löffler 2004; Homburg et al. 2008; Schreiber and Mai 2008; Müller and Wiese 2010; Hechtner et al. 2011).

Eleven articles examine the choice of financial instruments (Altrock 2002; Klein 2004; McDonald 2004; Tsai 2005; Guenther and Sansing 2006; Dierkes et al. 2009; Qi et al. 2010; Sikes and Verecchia 2015; Mammen 2016; Meyering and Hintzen 2018; Scheffler and Kohl 2018) and eight publications deal with timing considerations (Panteghini 2006; Patek 2007; Mai 2006; Maßbaum and Sureth 2009; Dorfleitner et al. 2010; Hoffmann and Nippel 2012; Polito 2012; Bachmann et al. 2015). One analysis deals with the relation of inheritance tax and firm valuation (Diller and Löffler 2012). Other works examine the impact of collaterals (Li et al. 2016) or the German “Abgeltungssteuer” (Kiesewetter and Lachmund 2004) on a firm’s capital structure (Li et al. 2016).

Four of the 90 publications appeared in A + journals, ten in A-journals, 53 in B- and 22 in C-journals. Inherently to the topic, the great majority of papers employs multi-period models (76 models); 54 models are stochastic. Of all 90 models, 80 concern domestic settings. Surprisingly, no single paper models a fiscal authority as a strategic player.

4.13 Investment

ATR on the relation between investment and taxation comprises 68 publications and therefore is the second biggest topic in ATR according to our survey, accounting for 19.7% of all ATR-papers from 2000 to 2022. Investment-related ATR can be divided into the subcategories “investment valuation”, “choice of investment instrument or location”, “timing and uncertainty considerations”, “calculations of tax burdens and effective tax rates” and “risk-taking”.

The analyses by Babcock (2000), Hillebrandt (2001), Buhl et al. (2001), Schröer (2004), Dunbar and Sansing (2002), Fochmann and Rumpf (2010), Williams et al. (2010), Diedrich et al. (2011), Bachmann et al. (2016c), and Albertus et al. (2022) deal with valuation of potential investments, i.e., firms or assets. Other publications examine the choice of capital accumulation and asset allocation (Shoven and Sialm 2004; Alvarez and Koskela 2007; Dietrich and Kiesewetter 2007; Fischer and Gallmeyer 2017), of location (Ortmann 2015) or of investment funds (Kühn et al. 2019; Kalies 2020) or evolve around shareholders (Guenther and Sansing 2006; Lindhe and Södersten 2016; Babkin et al. 2017; Gurr 2019).

Papers in the third subtopic analyze investment timing considerations, partially under conditions of irreversibility (Jou 2000; Böckem 2001; Hundsdoerfer 2001; Niemann 2004; Niemann and Sureth 2004, 2005, 2008 & 2013; Becker et al. 2006; Panteghini 2007; Knirsch and Schanz 2008; Knobloch 2008; Kudert and Klipstein 2010; Morellec and Schürhoff 2010; Schneider and Sureth 2010; Niemann 2011; Marekwica 2012; Kari and Laitila 2015; Hegemann et al. 2017; Weisbach 2017; Cai et al. 2018; Niemann and Sureth-Sloane 2019; Eberhardt and Thomsen 2019) or with regard to inheritance taxation (Diller et al. 2021).

Thirteen articles are dedicated to calculations about tax burdens and effective tax rates (Panteghini 2001; Devereux and Griffith 2003; Sureth and Langeleh 2007; Diller 2008b; Sureth and Maiterth 2008; Müller and Sureth 2010; Blaufus and Mantei 2014; Fochmann and Jacob 2015; Mori and Ikeda 2015; Sander and Schmiel 2016; Melkonyan and Kahlenberg 2017; Hechtner 2017; Kudert and Höppner 2020). Moreover, six articles analyze risk-taking and related returns (Benninga and Sarig 2003; Fedele et al. 2011; Nippel and Podlech 2011; Pummerer and Steller 2013; Sims 2015; Bauer and Kourouxous 2017). Three other articles create strong relations to empirical research by developing new empirical instruments or measures (Robinson and Sansing 2008; Shackelford et al. 2011; Diller et al. 2017) or find theoretical underpinnings for empirical evidence (Bachmann et al. 2018).

Seven of the 68 articles in the topic appeared in A + journals, eight in A-journals, 35 in B-journals and 17 in C-journals. Similar to the finance-related models, most investment-related models span more than one period (52 models). Again, the majority of the models (37 models) are stochastic and refer to domestic settings (60 models). Only one model treats the fiscal authorities as a strategic player.

5 Development of analytical tax research over time

This section quantitatively illustrates how ATR evolved over time with regard to its outlets, i.e. rating and category, the publication language, the size of the author teams and the gender distribution within the teams. It is important to notice, that we have a full overview about the completed decades 2000 to 2009 and from 2010 to 2019, while the current decade is still ongoing. For the current decade, we can analyze the full years 2020 and 2021, and the year 2022 until November 5. Hence, any final assessments for the current decade would be premature; rather we describe trends—that may or may not persist throughout the upcoming years.

To give an overview on the external perception of ATR, we look at the number of papers by journal rating and year of publication, as summarized in Table 4.

The number of yearly publications has been relatively constant between 2000 and 2022 with a mean of 15 publications per year. The proportion of publications in A + and A-journals stays at a similar level from the 2000s (6.3% and 14.5%), 2010s (5.0% and 14.3%) until the years 2020 to 2022 (4.0% and 16.0%), although the top-level journals in our review have increased their number of issues in the last ten years. It is noteworthy that the share of publications in B-rated journals decreased by ten percentage points from the 2000s to the 2010s, accompanied by a shift towards publications in C-rated journals in the 2010s.Footnote 12 However, this shift does not continue in the recent three years, where the B-publications outweigh the C-publications by far (64 vs. 8%). Consequently, it is not possible to identify a clear trend towards higher- or lower-ranked journals.

Next, we turn to the journal categories, in which the papers appeared. We distinguish between the disciplines accounting, business research (BWL), economics, finance and taxation and allocated each of the 51 journals in our study to one of them.Footnote 13 Strikingly, neither accounting nor tax journals account for the most publications in ATR, as Table 5 shows. Actually, business research journals have been the major outlet for ATR since at least 2000, publishing 44.9% of all articles—however, the trend does not persist in the most recent three years, in which economics and accounting journals overtook business research journals with regard to ATR publications. Economics journals have covered a quarter of all of ATR publications since 2000, and are even experiencing an upward trend recently. In contrast, finance journals account for only a small fraction of publications throughout the decades between 6.3 and 8.0%. This is surprising, because finance-related topics are very popular in ATR, as pointed out in Sect. 4. Overall, tax journals do not seem to be the preferred outlet for ATR, which appear to focus on legal or empirical tax research, but experience an upward trend in the last three years.

Next, we summarize the language, in which the papers are written by publication decade in Table 6. Of all 345 articles, 201 (58.3%) are written in English and 144 (41.7%) in German. We fully acknowledge that the large number of publications in German language is due to our special consideration of German BTR in this literature review, the related usage of the VHB-Jourqual3 as our basis for journal ratings and our manual search in mainly German journals, as explained in Sect. 2. Despite this special focus on German publications, we observe a shift in the publication language from German to English throughout the years. While German was almost on par with English in ATR publications in the 2000s, now the vast majority of published papers is written in English, i.e. 76% in the last three years.

Of the 345 papers in our study, 119 are single-authored, 142 papers have two authors, and 76 have three authors. Only seven papers have four authors and one article was written by five authors, the maximum team size in our review. The average author team comprises two researchers. We observe a slight increase of the average number of authors per paper over time, with a minimum of 1.6 in 2000 and a maximum of 2.4 in 2018. Table 7 summarizes the observations.

Apart from shifts in language and the number of co-authors, we also detect changes in the gender distribution within the authors or author teams that contribute to ATR. Table 8 shows that throughout the last 23 years, 71.6% of all teams (including single authors) comprised male researchers only, while purely female single authors or author teams are rare (for 5.2% of all papers). Overall, 14.2% of all teams in ATR were gender-balanced. However, the proportion of purely male author teams in ATR has decreased from 74.2% in the 2000s to 56% in the last three years. At the same time, the overall number of women in author teams rose over the years, while the number of gender-balanced teams has stayed roughly constant. Since 2020, the average proportion of women in author teams has been 28.7%.

6 Citation analysis for analytical tax research at the publication level

This section describes the impact of ATR on the research community as measured by citations. To disentangle the impact of research findings and individual researchers, we distinguish between citations related to specific publications and citations related to individual researchers. To capture the impact as comprehensibly as possible, we rely on three different databases, Scopus, Google Scholar and Web of Science Core Collection (WoS). Using three databases allows us to depict different dimensions of impact and integrating an immediate validity check. First, we use Scopus to ensure internal consistency with our previous literature review. Second, we incorporate citations as captured by the web search engine Google Scholar to depict impact in a wider range of literature, such as preprints, monographs or dissertations and journals that are not covered by Scopus. Third, we use WoS as a genuine citation database.Footnote 14 To keep the analysis manageable and work within the scope of this literature review, we do not track when a paper was cited or by which other publications it was cited.Footnote 15

Of the 345 papers in our survey, 196 papers (56.8%) have citation number entries in Scopus, 313 papers (90.7%) in Google Scholar, but only 131 papers (38.0%) in WoS. For the remaining papers, the citation numbers are missing in the respective databases. Table 9 provides descriptive statistics for the distribution of citations per paper in each database if missing entries are treated as zero; Table 10 provides the same statistics if missing entries are excluded. For both approaches, the distribution of citations is heavily right-skewed. For the citation analyses in this section, we replace missing entries as zero, since we want to picture the measured impact of ATR from 2000 to 2022.

To introduce a benchmark, we begin by providing results on the number of citations overall and in the different research topics in Table 11. All 345 publications generated 3,401 (Scopus), 13,132 (Google Scholar), 2,832 (WoS) citations in total (effective date: December 22, 2022). ATR on the choice of legal form for companies as well as pensions and provisions hardly create any citations, even in the broader database of Google Scholar, because these research areas are characterized by specifics of the German or Austrian tax law and therefore hardly relevant for an international audience. The three papers in the topic “role of tax advisors” are rarely cited, most probably due to their recent publication dates. Surprisingly, the two largest areas of finance- and investment-related ATR do not generate corresponding amounts of citations. A reason for this observation might be that many of these papers were published in Germany-based (business research) journals without a wider international range rather than in internationally visible finance journals that attract significantly more citations.Footnote 16 Often, these papers refer to German tax reforms and are interesting mainly for researchers affiliated with German institutions. In contrast, the area of tax avoidance, evasion and profit shifting accounts for more than 40% of all citations—even though publications in this area make up only 16.2% of all publications in our sample. Only 1.4% of all publications deal with private decisions, such as tax-minimizing marriage, but generate between 8.5% (Google Scholar) and 11.9% (WoS) of all citations.Footnote 17

As Table 12 depicts, publications in journals with A + and A-rating have a substantially higher mean number of citations (78.5 or 23.0 in Scopus; 265.8 or 71.5 in Google Scholar; 70.6 or 18.0 in WoS) than publications in B- or C-journals (3.3 or 0.5 in Scopus; 18.3 or 8.5 in Google Scholar; 2.6 or 0.1 in WoS). From 2000 to 2022, 200 papers appeared in B-journals, 67 in C-journals (Table 4). Almost two thirds of the B-publications (125) and more than three quarters of the C-publications (52) were not even cited once according to Scopus. As supplemental material 4 in the Appendix, we provide the results of a simple regression analysis with the citation numbers as the dependent variable and the language of the publication, journal ratings and categories, and female share of the author team, and publication year as the independent variables. The results show that a journal rating below an A + rating is significantly associated with lower citation numbers.Footnote 18 Furthermore, the year of publication and citations of an article are negatively related, as a more current article had less time to attract attention and hence generate citations. While the language has no significant relation to the citation numbers for an individual paper, many German or Germany-based journals have lower rankings and account for a substantial proportion of articles in our review, which especially considers German contributions to ATR. More than half of all publications in our review are covered by six Germany-based journals: Zeitschrift für Betriebswirtschaft (ZfB)/Journal of Business Economics (JBE) (B-rated, 14.2% of all papers), Betriebswirtschaftliche Forschung und Praxis (BFuP) (C-rated, 9%), Steuer und Wirtschaft (StuW) (B-rated, 7.8%), Zeitschrift für Betriebswirtschaftliche Forschung (ZfbF)/Schmalenbach Business Review (SBR) (B-rated, 7.8%), FinanzArchiv (FA) (B-rated, 6.4%) and Die Betriebswirtschaft (DBW) (C-rated, 6.4%). However, these six journals combined account for only 3.0% (Scopus), 14.7% (Google Scholar) and 2.2% (Web of Science) of all citations.

Table 13 shows key citation figures for the ten journals with the most publications in our literature review. The journals of German origin ZfB/JBE, BFuP, StuW, DBW, ZfbF/SBR, FA and also the Review of Managerial Science (RMS) have far lower shares in total citations than their corresponding shares in total ATR publications. The Journal of the American Taxation Association (JATA), the internationally well-known journal of the Tax Section of the American Accounting Association, is similarly “under-cited”, benchmarked against publication shares. Publications in JATA generated only up to 1.1% of all citations (Scopus), but represent 2.9% of all papers in ATR from 2000 to 2022. This finding suggests that the low citation numbers are not only due to the German language or origin of an article.

In contrast, economics journals such as International Tax and Public Finance (ITax), even though B-rated, and Journal of Public Economics (JPubE), A-rated, have much higher shares in total citations than in total publications and therefore can be called “over-cited”. Overall, the distributions of citations per paper are highly right-skewed with citation medians well below the respective means.

Confirming previous findings (e.g., Rapp et al. 2019), the English publications account for between 89.5% (Google Scholar) and 99.97% (WoS) of all citations, as captured in Table 14.

Finally, Table 15 summarizes the citations of publications distinguished by journal category. While only 7% of all ATR publications since 2000 appeared in finance journals (Table 5), citations in these journals account for between 37.7% (Google Scholar) and 45.1% (WoS) of all citations. As shown in supplemental material 4 in the Appendix, a publication in a finance journal and citation numbers are positively associated. Similarly, only a quarter of publications appeared in economics journals, but generated around 40% of citations. However, the “over-citation” for economics journals is not statistically significant. In contrast, 45% of all papers appeared in business journals, but generated only between 3.1% (WoS) and 13.8% (Google Scholar) of all citations. Tax journals published 12.2% of all papers in our review, but only between 1.4% (WoS) and 3.5% (Google Scholar) of all citations are related to these papers. Part of the explanation is that a substantial amount of papers in our review was published in StuW (10.7%), which is not covered by Scopus and WoS and accounts for only 1.3% of Google Scholar citations. Hence, tax journals are neither the preferred outlet for ATR, nor do they have high impact as measured by citations. Consequently, articles in economics and finance journals tend to be over-cited, articles in business and tax journals are under-cited, relative to the number of papers in our study. Citation numbers in accounting journals are roughly proportional to the number of papers.

As a sensitivity analysis, we exclude the two most frequently cited papers (Desai and Dharmapala 2006, concerning the topic of tax avoidance, tax evasion and profit shifting, and Desai et al. 2007, concerning the topic of private decisions) from our sample, since they account for almost one third of all paper citations. In the following, we describe the effect of the exclusion of the articles on the previous analyses.

With regard to the citations by research topics, the citations in the area of tax avoidance decrease by around 12 percentage points. However, the topic remains the most frequently-cited one with up to 34.7% of all citations (WoS). Investment-related ATR follows in second place (increase of around 7 to 8 percentage points in all databases) and finance-related ATR (increase of around 6 to 7 percentage points in all databases). The topic of private decision loses almost all its citations.

Since the two deleted articles were published in the Journal of Financial Economics, an A + rated journal, the citation shares of the A + journal category decrease dramatically by around 20 percentage points for all databases. Accordingly, the citation shares for A-rated journals increase substantially up to 49.9% (Scopus) and up to 28.4% (Scopus) for B-journals. Hence, at least in Google Scholar, the category of B-journals become the most-cited one, also because the now most-cited paper (Devereux and Griffith 2003) was published in the B-rated journal International Tax and Public Finance.

Similarly, the citation shares of finance journals—although still overrepresented when benchmarked against their total share in ATR publications—decrease by up to 30 percentage points. After the exclusion of the outlier papers, economics journals become even more dominant with regard to citation shares, accounting for up to 65.2% of all citations (WoS, 42.1% previously).

7 Citation analysis for analytical tax research at the researcher level

7.1 Overview of characteristics of authors and author teams

In this section, we present some statistics regarding the authors of the 345 publications in our literature review, i.e. our author population. Contrary to our previous analyses, we do not rely on the Web of Science as a database at the author level, since different authors with identical names are sometimes treated as the same person, blurring their individual citations. For each author, we gather information on their affiliation,Footnote 19 i.e. the name and country of the institution, gender, respective number of (co-)authored publications in our review, number of co-authors in our author population and number of citations in Scopus and Google Scholar, and Scopus and Google Scholar h-indices. The h-index is an indicator of productivity and citation impact of the author. In the next subsection, we identify an author’s impact in the research community, approximated by individual citations.

As Table 16 shows, the 345 papers in our literature review are (co-)authored by 410 individuals from 26 countries. As explained in Sect. 2 and emphasized throughout the paper, authors from German institutions make up the majority of researchers due to high representation of German journals in our literature review. More than 47% of all researchers are affiliated with German universities and 55% of all authors in work for institutions of the German-speaking countries Germany, Austria and Switzerland (henceforth D-A-CH regionFootnote 20). We include Swiss authors, because Switzerland is part of the VHB area. The inclusion of Switzerland also accounts for the physical proximity and same official language, which can drive research interests. As pointed out in the previous sections, many of the D-A-CH-authors tend to focus on specific problems in national tax law and in German language, which might be published in lower ranked journals, not generating high citations numbers (see Table 13). Nine authors of D-A-CH-institutions are associated with Swiss universities (see Table 16).

Among the 410 authors in our population, 355 (78%) are listed in the Scopus database; 49 of the remaining non-listed 55 authors are or were affiliated with German institutions.Footnote 21 Only 175 (42.6%) of all authors are registered at Google Scholar. Except for two authors, all authors with a Google Scholar entry are also listed in Scopus, but not the other way around. There are even several highly respected international researchers without Google Scholar information.Footnote 22 Apart from the smaller number of mostly German authors, the Scopus-listed subgroup is identical to the total author population. In contrast, the subgroup of Google Scholar-listed authors is much more centered around Anglo-American countries, i.e., Australia, Canada, New Zealand, UK, USA, with 74 of 175 authors (42.2%) and much less on the D-A-CH countries (48 of 175 authors, or 27.4%).

Within our literature review, the vast majority of authors (co-)authored solely one article within our sample (75.3%). As Table 17 summarizes, 54 authors wrote two, 20 wrote three, nine wrote four, and 18 wrote five or more articles within our sample. The average number of publications is 1.6; 17 articles constitute the maximum number of publications of one author. Of course, this distribution does not reflect absolute research productivity, since publications in disciplines apart from ATR are not part of our examination. However, the large gap between median (1 paper per author) and maximum number of publications (17 papers for one author) in ATR points to the heterogeneity of the research field, where some authors make ATR their main or only focus, whereas others address ATR issues only occasionally.

Table 18 displays the number of distinct co-authors for each of the 410 authors in our review.Footnote 23 Of all 410 authors, 57 (13.9%) do not have co-authors within our author population. Nevertheless, most of the authors in our review have one or two co-author(s) within the ATR community, with a mean of 1.7 and maximum of 14. Repeated co-authorships are counted only once. Overall, the previously described findings show that the ATR community is open to researchers who primarily work in other disciplines.

7.2 General insights on authors’ impact

We evaluate the impact of individual researchers by means of several metrics, such as absolute citations and h-indices, to minimize discretionary leeway. Table 19 gives an overview on the distribution of absolute citations at the authors’ level.

Citation numbers in Scopus and Google Scholar are highly correlated with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.96.Footnote 24 The distribution of citations is highly right-skewed, since many authors are rarely or even never cited and a few authors are cited very frequently. Of 355 authors included in Scopus, 24 authors (6.8%) have zero, 86 (24.2%) ten or less Scopus citations. In contrast, three authors in our population have more than 10,000 Scopus citations and 14 authors have more than 10,000 Google Scholar citations.Footnote 25 The top 10% authors of each database account for 68.6% of all Scopus citations (35 authors) and 55.8% of all Google Scholar citations (17 authors).

Due to the larger number of publications covered by Google Scholar, the citation counts are also much higher, especially at the lower end of the distribution. This notion is underlined by a look at the first quartile of citations—whereas the mean number of Google Scholar citations per author is 6.9 times (= 4,185.6/603.7) the mean number of Scopus citations, the multiple is 46.3 (= 533/11.5) for the first quartile and 12.8 for the median (= 1,493/117).Footnote 26

Despite the high correlation between Scopus and Google Scholar information, we include Google Scholar citations in our analysis for two reasons. First, they allow capturing the impact of less-cited authors, such as authors who publish in Germany-based or German-language journals (see Table 13), since Google Scholar depicts impact in a wider range of literature, such as preprints, monographs or dissertations and journals that are not covered by Scopus. Second, they give a broader view of an author’s oeuvre in lower-ranked journals and herewith total research productivity (see also Sect. 6).

Next, we use the h-index to measure the impact in the research community throughout the years 2000 to 2022, as displayed in Table 20. The h-index is defined as “A scientist has index h if h of his or her Np papers have at least h citations each and the other (Np−h) papers have ≤ h citations each.” (Hirsch 2005:16,569). Since the definition of the h-index limits the influence of outliers, i.e. very frequently cited papers at the author’s level, the distribution of the h-indices is less right-skewed than the distribution of citations. Nevertheless, the median h-indices of 5 (Scopus) and 18 (Google Scholar) also show that half of all authors are rarely cited. In our author population, 90% have an h-index of 17 or less (Scopus) or 39 or less (Google Scholar). We want to note carefully that h-indices seem to be specific to certain disciplines, e.g., h-indices of researchers in the Natural Sciences appear to be much higher (e.g., Hirsch 2005) and comparisons across different subdisciplines should be handled with care. The larger an academic discipline, the higher is the probability of a paper being cited—as noticed before, ATR constitutes a rather small discipline.

7.3 Gender and citations

As pointed out in Sect. 5, a decreasing, yet remarkable gender imbalance in author teams still characterizes ATR (Table 8). At the individual level, 81.4% of Scopus-listed authors are male, only 18.6% are female. With regard to a possible gender citation gap, we find mixed results. Table 21 shows the Pearson correlation coefficients between a gender dummy (1 for females, 0 for males) and our citation measures. All correlation coefficients are negative, but very small. The correlation coefficients between the number of citations and the gender dummy are not statistically significant. However, the correlations between gender and the h-indices are statistically significant, but only at the 5% and 10% significance level, respectively. Although the mean, median and maximum citation numbers for male authors are much higher than for female authors for both citations, as shown in Table 22, and h-indices, as shown in Table 23, the differences are not statistically significant. In supplemental material 5 in the Appendix, we provide the results of an additional simple regression analysis with citation metrics as the dependent variable and gender, country of affiliation and number of published documents as independent variables. The analysis cannot confirm a systematic gender citation bias exists. However, we do not want to state overconfident results based on first and rather simple analyses and do not exclude that a gender citation bias exists in ATR. These first results can serve as a starting point for an analysis, which is fully dedicated to examining such possible biases.

7.4 Country of affiliation and citations

From our previous citation analyses at the publication level (see Table 13), we infer the country of the author’s home institution to play a role in the author’s individual impact. Again, we use dummy variables (1 for D-A-CH affiliation, 0 otherwise) in our separate analyses. Table 24 shows the correlation coefficients for the indicator variables D-A-CH and our citation metrics, Table 25 for the Anglo-American-dummy and our citation metrics. Indeed, authors from German-speaking institutions (in the D-A-CH region) are much less frequently cited than authors from Anglo-American institutions.Footnote 27

We find negative (positive) correlations between affiliation with an institution in the D-A-CH (Anglo-American) region and citations as well as h-indices. The correlation coefficients for Scopus metrics are highly significant, for Google Scholar metrics only at the 10% level. In supplemental material 5 in the Appendix, we show the results of a simple regression analysis with citation metrics as the dependent variable and gender, country of affiliation and number of published documents as independent variables. It supports the notion that an author’s affiliation with a D-A-CH-institution is negatively associated with individual citation measures. In contrast, the affiliation with an Anglo-American institution and individual citation measures are positively related. The distributions of citations and h-indices in the respective subsets of our dataset underline the observations, as shown in Tables 26 and 27.

Overall, authors from the D-A-CH region have lower citation scores than authors from the Anglo-American countries. While it is not surprising that the international ATR community does not cite German publications due to language barriers and research questions that might be specific to German or Austrian tax (law), it is interesting that also researchers from the D-A-CH region rarely cite each other’s publications, as their overall low citation metrics reveal. The small size of this research community is probably part of the explanation. Along these lines, U.S.-based authors dominate the four lists of top 25 authors according to Scopus and Google Scholar citation numbers and h-indices, as displayed in supplemental materials 6 to 9. Table 28 displays all D-A-CH-based authors who appear in at least one of the four top 25 lists.

Only one of the D-A-CH-based authors in this list has his research focus on the core discipline of BTR. The other authors are from neighboring disciplines such as public economics and finance. This insight suggests that a strong institutional background in (national) taxation is not necessary for publishing highly cited ATR papers.Footnote 28

It would be interesting to analyze whether these results are specific to D-A-CH-based authors or could also arise in a different national context. Here, an adequate control group would be crucial. It should consist of a non-English-speaking country with a strong base of national journals in which ATR is published to allow the detections of rifts between nationally relevant and internationally accessible publications. Given that BTR as a distinct academic discipline exists only in Austria and in Germany, we, however, conjecture that such a control group does not exist in tax research.

7.5 Sensitivity analysis

To conduct a sensitivity analysis at the authors’ level, we exclude the two most frequently-cited papers (Desai and Dharmapala 2006; Desai et al. 2007) from our sample, similar to our sensitivity analysis at the paper level (Sect. 6). Deleting these two papers also leads to the omission of four authors who are all highly-cited males, affiliated with Anglo-American institutions. Compared to the original author population of 410, the citation numbers of the remaining 406 authors are less right-skewed, although still distinctly asymmetric. The differences of the citation metrics between male and female authors are slightly reduced, as the four deleted authors are male. The correlation coefficients of the “female” dummy variable with the citation metrics continues to be negative, but either insignificant (citation numbers) or only significant at the 10% level (h-indices).

The dominance of Anglo-American authors with respect to citation numbers and h-indices is only marginally affected by the omission of the four (Anglo-American) authors. The signs, sizes and p-values of the correlation coefficients of the “D-A-CH” or “Anglo-American” dummy variables and the citation metrics are very similar to the original author population of 410. As a consequence, all our results from the basic analysis are still valid.

8 Avenues for future research

8.1 Areas of focus and open research questions in analytical accounting research

Based on our analysis of research topics in Sect. 4, we try to identify growing, shrinking or previously neglected research areas in ATR. Currently, the areas of ATR on the role of tax advisors and entrepreneurship, innovation and R&D exhibit growth trends. The topic on the role of tax advisors experiences a (small) revival after it had already been a topic of interest in the 1990s. From 2000 to 2022, three papers concern the role of tax advisors, apparently leaving a lot of room for further research. We think that the role of tax advisors is under-investigated, especially when benchmarked against its practical relevance. Small and medium-sized firms as well as multinationals use the help of either external or in-house tax advisors for tax declaration or tax planning, and for regular or infrequent transactions.Footnote 29 Tax advisory is a highly specialized service whose quality the recipient cannot observe easily or verify beforehand, so that principal-agent problems arise. Selecting the right advisor, choosing between external advisors and an internal tax department, or monitoring (internal or external) tax advisors poses decision problems that well-established models from principal-agent theory or game theory could address. Doing so could provide the missing theoretical basis for tax avoidanceFootnote 30 or additional insights in the “under-sheltering puzzle”.Footnote 31

Moreover, we think that the interplay of taxes and entrepreneurship, innovation and R&D is of special importance due to the digitalization of the economy and the rise of business analytics for both scientific communities and practitioners. Often intangible assets, high risk and high growth potential and option-like values characterize digital business models whose tax consequences can deviate from traditional ones. Therefore, the combination of models for investment under uncertainty (such as real option theory, asset pricing or expected utility theory) with newly arising questions in innovation-related topics seems a promising avenue for future ATR. Findings can contribute to the theoretical basis for empirical studies in this field and inform the typical addressees of ATR, i.e., individual and corporate taxpayers and legislators.

Given the large number of applications for investment, financing, valuation and the well-established models in these areas, it is likely that these streams of the literature will continue to play a pivotal role in ATR. We think that the tax risk associated with particular investment and financing decisions or the riskiness of a tax shield in valuation procedures deserves special attention—especially in times of increased investment risk and volatile markets.Footnote 32 Similarly, the current discussion and implementation of taxes on energy-related windfall profits (see European Council 2022c) should trigger a reassessment of legislative fiscal risks for investors.

In contrast, the tax neutrality and tax burden literature both seem to have peaked in the 1990s/2000s.Footnote 33 The growing importance of cross-border rather than domestic models probably led to the insight that tax neutrality is unattainable in an international context with its variety of different tax rates and tax bases. Although, analyses of the effects of international tax allocation mechanisms, such as transfer prices or formula apportionment, constantly contribute to ATR, we are skeptical with respect to model-based analyses on the current OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) proposals, Pillar One and Pillar Two,Footnote 34 due to their complexity and unresolved legal issues.Footnote 35

Several tax topics are widely neglected in the papers in our review. Most striking is the near absence of analyses of non-profit taxes.Footnote 36 Despite the significant contribution of the Value-Added Tax (VAT) to tax revenue in most EU countries and proven interest from empirical research (e.g. Jacob et al. 2019), only one paper in our review also accounts for VAT-effects (Kroh and Weber 2016). The reasons for this neglect could be either due to the presumed neutrality of VAT or our exclusion of tax incidence papers that we attribute to public economics. Furthermore, none of the papers in our review addresses the effects of procedural law on economic decisions—although ATR could help firms to make informed decisions in administrative processes and legislators to understand firms’ behavior. In addition, ATR on transfer prices, tax avoidance or tax evasion currently neglects tariffs—even though they are crucial in cross-border trade and can either alleviate or aggravate tax incentives.Footnote 37 Integrating tariffs into analyses could provide additional explanations of tax avoidance behavior of multinationals.

Intensive discussions on ESG reporting have arisen recently.Footnote 38 If disclosure requirements extend to firms’ tax strategy (e.g., characterized as transparent, co-operative, aggressive, etc.), investors’ or other stakeholders’ reactions might induce firms to adjust either their tax strategy or their economic decisions, causing real economic effects. Since the rationale is not always straightforward, a formal model can provide a sound theoretical basis for future empirical studies and explain the possible effects. At a national level, research questions can arise from national tax reform proposals or multi-national initiatives and serve as triggers for ATR. Here, only formal models have the potential to explain the consequences for taxpayers as well as fiscal authorities and provide timely information for legislators.

8.2 Publication strategy

Given the low citation numbers and the low ranking of national journals, there seem to be few incentives to focus on analyses that benefit mainly practitioners, unless the researcher’s institution or professional environment considers such a focus a major responsibility of ATR. Authors who set that focus should not take the blame for an allegedly low research productivity, since ATR is a small academic discipline with high national relevance, but low international visibility. However, institutional incentives for researchers or reputational concerns can induce them to concentrate on more publishable topics. Finance journals typically do not attach importance to special institutional tax knowledge. Hence, ATR researchers should capitalize on such a knowledge by teasing out generalizable aspects of country-specific tax legislation and target accounting and public economics journals, which appreciate this approach. Paradoxically, publications in plain tax journals do not appear a particularly promising publication strategy for tax researchers.

9 Summary and conclusion

This literature review extends earlier reviews of tax research and focuses only on the area of analytical tax research (ATR) without a restriction to specific research topics, but with a special consideration of German and Austrian business tax research (BTR). We provide an overview of the development of ATR from 2000 to 2022 and evaluate its impact on the scientific community by means of citation analyses. Our literature review covers 345 publications, written by 410 authors in both German and English language. Most of the articles examine finance- and investment-related research questions. However, also novel topics, such as examinations of the impact of taxation on entrepreneurship, innovation and R&D, attract increasing interest; others, such as the topic of tax avoidance, tax evasion and profit shifting, remain high in interest. Within the 23 years of our review period, English has overtaken German as main publication language, and gender distribution in author teams has become somewhat more balanced, while the size of teams has remained similar throughout the years. Interestingly, tax journals are not the main outlet for ATR. Rather, our analysis shows that ATR united authors from different disciplines, such as accounting, business research, economics and finance in different outlets.