Abstract

The Mamu-A, Mamu-B, and Mamu-DRB genes of the rhesus macaque show several levels of complexity such as allelic heterogeneity (polymorphism), copy number variation, differential segregation of genes/alleles present on a haplotype (diversity) and transcription level differences. A combination of techniques was implemented to screen a large panel of pedigreed Indian rhesus macaques (1,384 individuals representing the offspring of 137 founding animals) for haplotype diversity in an efficient and inexpensive manner. This approach allowed the definition of 140 haplotypes that display a relatively low degree of region variation as reflected by the presence of only 17 A, 18 B and 22 DRB types, respectively, exhibiting a global linkage disequilibrium comparable to that in humans. This finding contrasts with the situation observed in rhesus macaques from other geographic origins and in cynomolgus monkeys from Indonesia. In these latter populations, nearly every haplotype appears to be characterised by a unique A, B and DRB region. In the Indian population, however, a reshuffling of existing segments generated “new” haplotypes. Since the recombination frequency within the core MHC of the Indian rhesus macaques is relatively low, the various haplotypes were most probably produced by recombination events that accumulated over a long evolutionary time span. This idea is in accord with the notion that Indian rhesus macaques experienced a severe reduction in population during the Pleistocene due to a bottleneck caused by geographic changes. Thus, recombination-like processes appear to be a way to expand a diminished genetic repertoire in an isolated and relatively small founder population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

During the past few decades, the Indian rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) has been one of the animals of choice for preclinical, biomedical research. Because of an import prohibition regarding these animals, however, researchers often make alternative use of rhesus macaques from China or aim to become self-sustaining by breeding Indian monkeys. The Biomedical Primate Research Centre (BPRC) has chosen the latter possibility mainly because the genetics of the Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC), which is highly important for diverse immune-related diseases, has been studied exhaustively in these monkeys for more than 30 years. Additionally, a few groups were assembled with rhesus macaques of Burmese origin. In addition to rhesus macaques, cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) have emerged as study animals in recent years, and the BPRC houses a small breeding colony of Indonesian cynomolgus monkeys.

As in humans, the highly polymorphic genes of the macaques' MHC encode cell-surface glycoproteins, of which the classical class I (Mamu-A and Mamu-B) and class II (Mamu-DR, Mamu-DQ and Mamu-DP) molecules are equipped with a groove that can accommodate peptides of foreign origin. In the past, the BPRC's Indian-origin rhesus macaque colony was typed for its MHC (Mamu)-A, MHC-B and MHC-DR antigens (Bontrop et al. 1995; Roger et al. 1976; van Es and Balner 1978) by serological methods. Haplotypes were defined by segregation analyses and named according to the founder animals, in which the haplotype was originally observed. Over the last two decades, serotyping has been replaced by molecular techniques like full-length cDNA sequencing for class I (Boyson et al. 1996; Otting et al. 2007; Otting et al. 2005; Otting et al. 2008) and sequencing of the most polymorphic exon 2 of the various class II genes (Bontrop et al. 1999; Doxiadis et al. 2001; Doxiadis et al. 2000; Khazand et al. 1999; Otting et al. 2002; Otting et al. 2000; Otting et al. 1998; Slierendregt et al. 1995; Slierendregt et al. 1994). In Indian rhesus macaques, DP and DQ molecules are encoded by a single pair of genes: namely, DPA1/DPB1 and DQA1/DQB1, respectively. In contrast, the A, B and DR regions have been subjected to several rounds of duplications (Dawkins et al. 1999; Gaudieri et al. 1997; Kulski et al. 1999). As a consequence, the A, B and DRB macaque regions show diversity in both the number and variety of loci that are present per chromosome/haplotype, a phenomenon referred to as “region configuration polymorphism” (Bonhomme et al. 2008; Doxiadis et al. 2011; Doxiadis et al. 2009b; Otting et al. 2005; Slierendregt et al. 1994). For Indian rhesus macaques, one to three transcribed A genes may be present per haplotype, of which A1 is generally the most polymorphic one characterised by a high transcription level (Otting et al. 2005). The A region of rhesus macaques of other origins and of cynomolgus macaques of various origins shows even higher levels of diversity (Budde et al. 2010; Kita et al. 2009; Ma et al. 2009; Otting et al. 2007; Pendley et al. 2008; Saito et al. 2012; Wiseman et al. 2009). The Mamu-B region shows still more region configuration polymorphisms reflected by up to ten transcripts per haplotype (Daza-Vamenta et al. 2004), of which only one or two are transcribed at a higher level in B cells and/or PBMCs (Campbell et al. 2009; Greene et al. 2011; Karl et al. 2008; Otting et al. 2005; Otting et al. 2008; Uda et al. 2005). However, expression levels may vary in different cell types as described for distinct leukocyte subsets (Greene et al. 2011). Furthermore, the DRB region of rhesus and cynomolgus monkeys contains two to six DRB genes per haplotype, two or three of which appear to be transcribed, whereas the others seem to be pseudo-genes (Blancher et al. 2012; Blancher et al. 2006; de Groot et al. 2004; Doxiadis et al. 2012). In contrast to humans, in which only five DRB configurations (DR1, DR8, DR51, DR52 and DR53) are described and which all contain a very polymorphic DRB1 gene, a high number of DRB configurations have been defined in macaques with low levels of allelic variation within a given configuration.

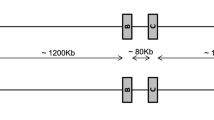

Because of the variable number and content of Mamu-A, Mamu-B and Mamu-DRB genes per haplotype, most techniques suitable for their molecular typing are time consuming and laborious. Therefore, microsatellite genotyping methods have been developed based on the presence of polymorphic short tandem repeats (STR), the amplification of which results in length patterns that are characteristic for the various A, B and/or DRB haplotypes. In the case of Mamu-A, two microsatellites, D6S2854 and D6S2859, have been used that are localised next to the relevant genes (Doxiadis et al. 2011). The Mamu-B region can be defined by four different STRs, MIB6, MIB7, MICA and D6S2793, which are situated in the B region of macaques (Bonhomme et al. 2008; Doxiadis et al. 2009b). The most straightforward genotyping can be performed with microsatellite D6S2878, named DRB-STR, which is localised within intron 2 of virtually all DRB genes and, thus, serves as an excellent tool for haplotyping both macaque and other primate species (de Groot et al. 2008a; de Groot et al. 2009; Doxiadis et al. 2007a; Doxiadis et al. 2009a; Otting et al. 2012). A combination of all molecular techniques mentioned above has been implemented to screen the Indian and Burmese rhesus macaques and to define their MHC haplotypes. The results of this study will be presented and compared to the Mhc haplotypes of Indonesian cynomolgus monkeys.

Materials and methods

Animals and cell lines

The BPRC houses a breeding colony of about 650 rhesus macaques of Indian origin. The colony was founded in the 1970s by more than 140 animals, and it has been pedigreed for more than seven generations. Additionally, the BPRC-bred rhesus macaques of Burmese origin were founded by two alpha males and 13 females and two mixed-bred animals, but breeding of these animals has been discontinued. For the last 10 years, all breeding groups consist of one alpha male and two to six females with their offspring. Lymphoblastoid B-cell lines and genomic DNA (gDNA) have been available from most of the animals in the colony for the last 20 years so that animals could also be typed retrospectively. Thus, in the present study, 2,377 Mamu core haplotypes (Mhc-A, Mhc-B and Mhc-DRB) of 1,384 rhesus macaques of Indian and 145 of Burmese origin could be defined. Extended haplotypes with additional DQA1, DQB1 and DPB1 information have also been defined on more than 2,000 chromosomes for the Indian rhesus macaques, and Mamu-A/B/DRB/DQ haplotypes have been determined on 258 chromosomes of rhesus monkeys of Burmese origin.

Haplotype definition

In the past, Mhc haplotypes of Indian rhesus macaques were defined by co-segregation of A and B antigens in at least two animals of the same family and were named according to the founder animal, with prefixes A and B indicating a founder male and prefixes C and D indicating a founder female, respectively. Currently, a haplotype is defined by co-segregation of the same microsatellite (STR) pattern in at least two animals of the same family with STR D6S2878 for DRB and STRs D6S2854 and D6S2859 for Mamu-A. In addition, in most of the Indian monkeys, segregation of four B region-related STRs (MIC6, MIC7, MICA and D6S2793) has been followed. Furthermore, Mamu-A and Mamu-B as well as Mamu-DRB of a given founder haplotype have been ascertained by full-length complementary DNA (cDNA) or by exon 2 gDNA sequencing of selected animals, respectively. In such a way, 176 haplotypes of Indian rhesus macaques based on 137 founder animals have been defined along with 24 haplotypes of Burmese monkeys based on 17 founders.

Mamu-A and Mamu-B typing by full-length cDNA sequencing

RNA was isolated from lymphoblastoid B cell lines (RNeasy kit, Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and subjected to a One-Step RT-PCR kit (Promega BioSystems, Madison, WI, USA), as recommended by the supplier. In these reactions, the primers 5′MAS: AATTCATGGCGCCCCGAACCCTCCTCCTGG, 3′MAS: CTAGACCACACAAGGCGGCTGTCTCAC, 5′MBS: ATTCATGGCGCCCCGAACCCTCCTCCTGC and 3′MBS: CTAGACCACACAAGACAGTTGTCTCAG, which are specific for Mamu-A and Mamu-B transcripts, respectively, were used. The final elongation step was extended to 7 min to generate a 3′ A overhang. The RT-PCR products were cloned by using the InsTAclone kit (Fermentas, St. Leon-Rot, Germany) or the PCR cloning kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). After transformation, colonies were picked for plasmid isolations: namely, 16–32 colonies for the Mamu-A transcript and 32–64 colonies for the Mamu-B transcript, respectively. Sequencing reactions were performed using the BigDye terminator cycle sequencing kit version 3.1, and samples were run on a Genetic Analyzer 3130 (both Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The sequences were analysed with MacVector™ (Oxford Molecular Group).

Mamu-DQA1, Mamu-DQB1, Mamu-DPB1 and Mamu-DRB exon 2 sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from EDTA blood samples or from immortalised B-lymphocytes by a standard salting out method. The amplification of exon 2 of Mamu-DQA1, Mamu-DQB1 and Mamu-DPB1 was performed mainly according to earlier published methods (Doxiadis et al. 2003; Doxiadis et al. 2006), except that the PCR mix contained 5–50 ng of DNA, 2.5 mM of MgCl2, and 0.4 μM of the following primers for DQB1: 5′DQB1-intr1 TCC CCG CAG AGG ATT TCG TG, 3′ DQB1-intr2 TGC GGG CGA CGA CGC CTC ACC TC or, alternatively, the following primers for DPB1: 5′DPB1new GGA TTA GGT GAG AGT GGT GCC C; 3′DPB1new CRG CCC AAA GCC YTC ACT CAC. The PCR conditions were according to published methods (Doxiadis et al. 2003), with an annealing temperature of 62 °C for DQB1. The PCR conditions and primers for amplification of DRB exon 2 + STR in intron 2 are described elsewhere (Doxiadis et al. 2007a). The exon 2 sequences of DQA1, DQB1 and DPB1 were first sequenced directly (Doxiadis et al. 2003) and analysed with the SBTengine programme (GenDx, Utrecht, The Netherlands). DQA1, DQB1 and DPB1 sequences containing unknown alleles as well as DRB sequences were subjected to cloning and sequencing with 15 to 60 clones selected on the basis of the amplicon using pJet cloning kit (Fermentas, Heidelberg, Germany) and on conditions as described above and elsewhere (Penedo et al. 2005). The sequences were analysed with MacVector™ (Oxford Molecular Group) and SeqMan Pro (DNASTAR, Lasergene). The sequence of the new allele Mamu-DQB1*06new (preliminary name; accession number KC835255) has been sent to NHP IPD-MHC and is waiting for allele definition. Although Mamu-DRA1 and Mamu-DPA1 are also at least oligomorphic, because their polymorphism is localised mostly outside exon 2, the alleles of these genes have not been determined in this study.

Microsatellite genotyping by D6S2878, D6S2854, D6S2859, D6S2793, MIB6, MIB7 and MICA

Mamu-DRB genotyping by microsatellite D6S2878 (DRB-STR) was performed as described earlier (Doxiadis et al. 2007a). Additionally, Mamu-A genotyping by STRs D6S2854 and D6S2859 was performed as published previously (Doxiadis et al. 2011; Wiseman et al. 2007). For genotyping of the Mamu-B region, four STRs (D6S2793, MIB6, MIB7 and MICA) were selected, and the following primers, which had been newly designed or published earlier (Wiseman et al. 2007), were used:

D6S2793-F NED-CTACCTCCTTGCCAAACTTGCTATTTGT, D6S2793-R AATAGCCATGAGAAGCTATGTGGGGGA, MIB6-F6-FAM-GATTCTTCAGAGAAGCAGAACC, MIB6-RCTGCAGATTTTCGTATGTAC; MIB7-F VIC-GAGAAGCAGAACCAATAGGGGG, MIB7-R TGTGCCTCATCCAATCAG TGG, MICA-F NED-CCTTTTTTTCAGGGAAAGTGC and MICA-RCCTTACCATCTCCAGAAACTGC. The labelled primers were synthesised by Applied Biosystems and the unlabelled primers by Invitrogen (Paisley, Scotland). The PCR reaction for D6S2793 was performed in a 20 μl reaction volume containing 1 U of phusion hot start high fidelity DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Breda, The Netherlands) with 3 % DMSO, 0.08 μM of the respective forward and reverse primers, 3.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 1× HF buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 50 ng DNA. For this PCR, a “touchdown” programme was used with 30 s at 98 °C as initial denaturation step, followed by 4 cycles as published earlier (Wiseman et al. 2007). A final extension step was performed at 72 °C for 5 min. For MIB7, the PCR reaction was performed in a 25-μl reaction volume containing 1 U of Taq polymerase (Invitrogen, Paisley, Scotland) with 0.24 μM of the forward and reverse primers, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 1× PCR buffer II (Invitrogen, Paisley, Scotland) and 50 ng DNA. For MICA and MIB6, a multiplex PCR was used in a 25-μl reaction volume containing 1 U of Taq polymerase (Invitrogen, Paisley, Scotland) with 0.48 μM of the forward and reverse primers of MICA, 0.2 μM of the forward and reverse primers of MIB6, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 1× PCR buffer II (Invitrogen, Paisley, Scotland) and 50 ng DNA. The cycling parameters for MIB7 and the multiplex PCR of MIB6/MICA were a 5-min 94 °C initial denaturation step, followed by 4 cycles of 1 min at 94 °C, 30 s at 58 °C and 30 s at 72 °C. The programme was followed by 25 cycles of 45 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 58 °C and 30 s at 72 °C. A final extension step was performed at 72 °C for 30 min. The amplified DNA was prepared for genotyping according to the manufacturer's guidelines and was analysed on the ABI 3130 genetic analyser (Applied Biosystems). STR analysis was performed using the GeneMapper programme (Applied Biosystems).

Test of linkage disequilibrium

Global linkage disequilibrium (GLD) between each pair of loci (known phase) was tested with an extension of a Fisher's exact test as implemented in Arlequin 3.5 (Excoffier and Lischer 2010). In brief, the test starts with a contingency table of haplotype counts, where the marginal totals are the allele counts at each locus and then uses a Monte-Carlo Markov Chain approach (Guo and Thompson 1992) to generate tables with the same marginal totals and a probability smaller than or equal to the original table. To assess the null hypothesis of no association (i.e., no linkage disequilibrium) between the loci, a p value equal to the proportion of tables having a probability smaller than or equal to the original table is estimated. The Markov chain was run for 9 million stages with an initial burn in of 10,000.

Additionally, the classical linkage disequilibrium coefficient D (and its significance using a χ2 test), the standardised linkage disequilibrium coefficient D′, and the square of the correlation coefficient r 2 were computed between all pairs of alleles/haplotypes for each pair of loci. For the A, B and DRB regions, which contain multiple loci, the alleles of each region of a certain haplotype (e.g., the Mamu-A region that may be represented by several Mamu-A genes) were summarised and considered to belong to a unique locus, since no recombination had been observed between them in the population studied. All allelic associations were reported; however, only haplotypes with more than three copies observed in the sample were discussed.

The adjustment of individual p values, which was made in order to take multiple testing into account (for GLD or haplotype linkage disequilibrium (LD)), was performed using the False Discovery Rate (FDR) method for each pair of loci (Benjamini and Yekutieli 2001). This method is less conservative than the usual Bonferroni's correction. However, the extra power comes at the cost of an increase in false positives and, therefore, results should be viewed with caution if only one or a few haplotypes exhibit significant adjusted LD p values for a given pair of loci.

Results

Mamu-A haplotyping of Indian rhesus macaques

In Indian rhesus macaques, 13 Mamu-A serotypes and an additional one, called “blank” (−), had been delineated in the past (Fig. 1). Additionally, five Mamu-A region configurations (r.c.) have been defined previously according to their number and content of loci, and “major” and “minor” A alleles have been determined based on transcription levels (Otting et al. 2007; Otting et al. 2005). The Mamu-A serotypes confer to A haplotypes, which are characterised by different lineages of the “major” A1 locus (Fig. 1, colour coded). The “minor” A2 locus comprises two lineages, A2*05 and A2*24, whereas two other “minor” loci, A3 and A4, are represented by only one lineage each, A3*13 and A4*14, respectively. Using high-resolution sequencing and additional methods such as microsatellite typing with D6S2854 and D6S2859 the serological “blank” specificity could be subdivided into two well-defined A haplotypes (Fig. 1; haplotype 1e: A—a, and 5d: A—b). Furthermore, one other haplotype could by redefined as well (Fig. 1, haplotype 2b), and an additional haplotype could also be deciphered (Fig. 1, last entry). The associated A alleles of the latter, however, have not yet been determined at the nucleotide sequence level. We were able to show that STR typing with both microsatellites resulted in STR-length patterns, which could always be unambiguously related to a certain Mamu-A haplotype. In such a way, 17 Mamu-A haplotypes could be defined (Fig. 1). Four A haplotypes, characterised by the lineages A1*001, A*002, A*004 and A*008, are observed at a frequency greater than 10 % in the Indian rhesus macaque panel tested (Fig. 1, red-bordered).

Mamu-A region configurations/haplotypes of Indian rhesus macaques. The order and positioning of the loci/lineages is schematically drawn and does not represent the actual localisation of the genes on the chromosome. Solidus indicates the detection of either one or the other Mama-A allele or STR length, whereas comma indicates that both STR lengths have been detected. STR lengths in brackets could not always be observed. Question mark indicates that an allele or locus is expected but (not yet) detected. n.d. not defined

Mamu-B haplotyping of Indian rhesus macaques

In the past, 15 B serotypes had been defined in our Indian rhesus macaque colony. These serotypes correspond to 17 region configurations/haplotypes that can be differentiated by molecular methods (Fig. 2). In contrast to the Mamu-A region, there may be one, two or three B loci per chromosome that encode for a “major” B transcript. The total number of loci, however, which encode for a B transcript and that are detected by Sanger sequencing, vary from one to seven per haplotype (Otting et al. 2005). Even more “minor” B alleles will be observed when high-throughput next-generation sequencing is performed. Furthermore, 40 different B lineages/loci have been defined in our Indian rhesus macaques. As a consequence, a B haplotype is mostly characterised by a set of B lineages/loci, which are jointly inherited together (Fig. 2). However, configuration 17, encoding the “major” allele B*012:01, harbours, additionally, a “major” B*022 (Fig. 2, haplotype 17a) or a “major” B*038 lineage (Fig. 2, haplotype 17b) or even both (Sauermann et al. 2008). This configuration encodes, furthermore, three “minor” alleles (not shown in Fig. 2) and represents the best-characterised rhesus macaque B region, since it is present on one of the chromosomes for which the physical map has been published (Daza-Vamenta et al. 2004; Otting et al. 2005; Shiina et al. 2006).

Mamu-B region configurations/haplotypes of Indian rhesus macaques. The order and positioning of the loci/lineages is schematically drawn and does not represent the actual localisation of the genes on the chromosome. Solidus indicates the detection of either one or the other STR length, whereas comma indicates that both STR lengths have been detected. STR lengths in brackets could not always be observed. n.d. not defined

To simplify Mamu-B haplotyping, several microsatellites were tested for their use as B region-specific markers. Because the Old World monkey's class I A region (Doxiadis et al. 2011; Kulski et al. 2004), and especially the B region (Doxiadis et al. 2009b), underwent several duplication processes in their evolutionary history, B-related microsatellite typing mostly results in highly complex and ambiguous patterns and, therefore, seems unsuitable as a typing tool. However, genotyping with microsatellites MIB6 and MIB7 (Bonhomme et al. 2008; Doxiadis et al. 2009b) resulted in patterns that are often haplotype-specific (Fig. 2). In addition, two microsatellites (MICA and D6S2793) were chosen. These microsatellites are localised within the MIC genes, which are situated next to the B region. As in the HLA system, each haplotype comprises two MIC genes (Averdam et al. 2007; Doxiadis et al. 2007b). In contrast to the situation in humans, however, rhesus macaques encode a MICB gene in conjunction with either a MICA or a MICAB gene, of which the latter is considered to be a fusion product of MICA and MICB (Doxiadis et al. 2007b). The MICA-STR is positioned within exon 5 of the MICA gene, whereas D6S2793 (=MICB) is observed within intron 1 of MICB as well as of MICAB. Thus, there should be only one MICA-STR present per haplotype, whereas two different STR lengths may be observed for D6S2793, which is indeed the case for the region configurations 5 and 10 (Fig. 2). In contrast to the A-related STRs, the four B-related STRs often show different STR lengths within a given B haplotype, which are, however, specific for a certain founder animal. Nevertheless, STR typing with the chosen microsatellites mostly leads to an unambiguous definition of the Mamu-B haplotypes. As observed for the A region, there are only a few B configurations: namely, those characterised by the lineages B*001, B*012 and B*024, observed at a frequency greater than 10 % in the panel (Fig. 2, red-bordered).

Mamu-DRB haplotyping

In contrast to Mhc class I typing in rhesus macaques, DR serotyping has been proven not to be valuable for high resolution typing, most probably due to the lack of suitable antisera. In the last two decades, cloning and sequencing of the most polymorphic Mamu-DRB exon 2 have been performed instead, and 16 DRB region configurations have been defined in our Indian rhesus macaque colony (Fig. 3). The number of DRB loci varies from two to six per haplotype, and 19 different DRB loci/lineages have been defined. Nearly all region configurations contain at least one DRB6 pseudo-gene, but other lineages, or certain alleles of other lineages as well, might not be transcribed (de Groot et al. 2004). Some loci/lineages, e.g., DRB3*04 and DRB1*07, are named according to human lineages as defined by their exon 2 sequence, but most lineages are macaque specific (“W”). In contrast to the B region, loci/lineages are shared by several configurations (Fig. 3, colour coded). As holds true for the A and B regions, however, allelic variation is rarely observed within a certain DRB configuration, with the exception of region configuration 3, which is polymorphic for both DRB1 loci (Fig. 3a–f).

Mamu-DRB region configurations/haplotypes of Indian rhesus macaques. The order and positioning of the loci/lineages is schematically drawn and does not represent the actual localisation of the genes on the chromosome. Solidus indicates the detection of either one or the other STR length. Here, STR lengths in brackets indicate that the STR lengths have been defined by sequencing, not by STR typing. n.d. not defined

Microsatellite typing with D6S2878, which is situated in intron 2 of nearly all DRB genes and possesses STR-length patterns that are haplotype specific, has recently been proven to be an ideal tool for DRB typing in various species (de Groot et al. 2008a; de Groot et al. 2009; Doxiadis et al. 2007a; Doxiadis et al. 2009a; Otting et al. 2012). Thus, microsatellite typing with this STR has been performed and has resulted in the definition of 22 DRB haplotypes in Indian rhesus macaques (Fig. 3). Only a few DRB haplotypes are highly frequent; 1a, 3a and 4 are present at a frequency greater than 10 % (Fig. 3, red-bordered).

Mhc-A–B–DRB haplotyping

In the present study, we were able to analyse 1,383 Indian rhesus macaques (N haplotypes = 2,377) for their A–B–DR region by various molecular techniques, which has resulted in the definition of 176 Mhc core haplotypes, 140 of which are different (Suppl. Table 1). Thus, most of the haplotypes are unique to one founder animal. Although the majority of these haplotypes are rare (1 %), 12 haplotypes are observed at a frequency between 2 and 4 %, and two A–B–DRB combinations are more frequent (5.6 and 8.5 %), but none exceeds 10 % (Table 1). Whereas the most frequent haplotype (A1*002:01–B*001:01, B*007:01–DRB3*04:03, DRB*W3:05) has been observed in three unrelated founder animals, the second most frequent combination (A1*004:01:01–B*19:01, B*024:01–DRB1*03:09, DRB6*01:01, DRB*W2:01) has been introduced into the breeding colony only once. As such, the latter frequency is the result of the breeding success of one single alpha male. Although the number of different Mamu-A, Mamu-B and Mamu-DRB types is limited within the Indian rhesus macaque population tested (17, 18 and 22, respectively, see Figs. 1, 2 and 3), the number of different Mamu-A–B–DRB core haplotypes is high. Indeed, Mamu-A can combine with diverse B and DRB haplotypes and vice versa (Suppl. Table 1). An example is given for the most frequent Mamu-A type, A1*004:01:01, A4*14, which has been observed to segregate with a total of 23 different B–DRB combinations in the Indian rhesus macaque population (Fig. 4A). Comparable results are gained if the most frequent B (B*001:01, B*007:01/02/03, B*030:02) and DRB (DRB1*03:09, DRB6*01:01, DRB*W2:01) haplotypes are analysed and can be detected with 26 different A–DRB and 23 A–B combinations, respectively (Fig. 4B and C).

Combinations of the most frequent Mamu-A, Mamu-B, or Mamu-DRB haplotype. A Mamu-A1*004:01:01 combinations with all different Mamu-B and Mamu-DRB haplotypes. B Mamu-B*001:01:01 combinations with all different Mamu-A and Mamu-DRB haplotypes. C Mamu-DRB1*03:09 combinations with all different Mamu-A and Mamu-B haplotypes

Extended haplotypes in Indian rhesus macaques

In addition to the core Mhc, polymorphism at the adjacent DQA1, DQB1 and DPB1 loci have been defined in Indian rhesus macaques. DQA1 and DQB1 show comparable allelic variation levels with 15 and 17 alleles observed, respectively (Suppl. Table 2). Furthermore, Mamu-DQA1 and Mamu-DQB1 segregate as strongly linked pairs (Fig. 5), of which DQA1*01:04/DQB1*06:01, DQA1*26:01/DQB1*18:01 and DQA1*26:02/DQB1*18:11 are the most frequent combinations in our cohort, with 17, 19 and 21 %, respectively. In our panel, DPB1 is the least polymorphic gene with 13 alleles, of which two are observed at a very low frequency (Suppl. Table 2, grey) and are only present in two unrelated founder animals. Extended Mhc haplotypes (N = 2,156) have been defined for 138 of the 176 founder haplotypes, and 127 have turned out to be unique (Suppl. Table 3). The most common A–B–DRB haplotype, A1*002:01–B*001:01, B*007:01–DRB3*04:03, DRB*W3:05, which has been observed in three founders (Table 1; A 2777, B 2957 and D 2849), can be subdivided into two haplotypes on the basis of their DPB1 alleles (Table 2, grey coloured). Both are present at nearly equal frequencies in the colony. Comparably, most of the common haplotypes that are represented by more than one founder can be subdivided by DQ–DP typing and, consequently, some of the founder A–B–DRB–DQ–DP haplotypes are observed at less than 2 % (Suppl. Table 3) and are, therefore, not listed in Table 2. Both haplotypes of one founder animal (2957) are segregating with a close high frequency (~4 %, Table 2), indicating that both haplotypes have been introduced at equal levels in the breeding colony.

Linkage disequilibrium of Mhc alleles of Indian rhesus macaques

Since the number of different extended haplotypes is high in comparison to the relatively low degree of classes I (A, B) and II (DRB, DQ and DP) haplotypes/alleles, we analysed the patterns of linkage disequilibrium in the founder population both by a test of global linkage disequilibrium (GLD) between each pair of loci/regions and by assessing the linkage disequilibrium (LD) of individual alleles/haplotypes. The p values of individual haplotypes were obtained by an extended exact test and were adjusted for multiple testing (as described in “Materials and methods”).

The global tests (Table 3) reveal strong associations amongst the class II loci/regions, and, more particularly, amongst DRB, DQA1, DQB1 and DPB1, which appear to form a tight linkage group, where each locus/region is in highly significant GLD (P < 0.001) with the others. A and B (P < 0.001), and B and DRB (P < 0.05) regions are also in significant GLD. These observations are consistent with relative genomic positions and physical distances amongst the loci (Daza-Vamenta et al. 2004).

The analysis of haplotype LD confirms the strong linkage for class II specificities, as many individual class II haplotypes exhibit significant linkage disequilibrium. For DQA1–DQB1, all tandems are in significant LD at the 1 % level, as is true for all but one DRB–DQA1 and DRB–DQB1 pair. DPB1, which is also in significant GLD with the other class II loci, shows a lower proportion of significant allelic association (1 % level) with the other loci (4/15 with DQA1; 5/14 with DQB1; and 4/15 with DRB) (Suppl. Table 4). The general pictures for linkage disequilibria presented by both methods (i.e., GLD and individual LD) are in close agreement, even if the adjusted p values that remain significant for the A–B haplotypes after multiple test adjustments refer to rare haplotypes with fewer than three copies (Suppl. Table 4, green coloured).

Mamu-A, -B and -DRB haplotyping of Burmese macaques

In contrast to the situation involving Indian rhesus macaques, Mamu-A and Mamu-B serotyping of monkeys of other origins could not be undertaken because of the lack of suitable antisera. As a result, only molecular typing data are available for rhesus macaques of Burmese origin. Within the offspring (# 145 animals) of two alpha male founders (4049 and 4052), 13 females, and two Indian/Burmese mix-bred animals, 15 different Mamu-A haplotypes could be observed (Table 4). Because no “minor” A loci have been detected for some of the Burmese A haplotypes, we did not define a locus/haplotype name. One haplotype, however, is identical to the Indian macaque haplotype 5a (Fig. 1 and Table 4, bold), and two others are probably identical as well. Unlike in Indian rhesus macaques, a region configuration lacking the A1 locus could be observed (Table 4, haplotype 11). Additionally, a duplication of the “major” A1 locus and configurations with another “major” A locus (A7) have been defined (Table 4, haplotypes 10 and 9). Furthermore, haplotypes are detected with other “minor” A loci such as A5 or A6, which have not yet been observed in Indian rhesus macaques (Table 4, haplotypes 7, 8 and 11) (Doxiadis et al. 2011).

Comparable results have been gained for the Mamu-B region of Burmese animals (Table 5). Here, 16 different B configurations/haplotypes have been defined by STR typing and full-length sequencing. In addition, two haplotypes could be determined by microsatellite typing but not yet by sequencing. Two B region configurations are probably identical in Burmese and Indian rhesus macaques (Fig. 2 and Table 5, haplotypes 8 and 11). Two B alleles (B*066:01 and B*067:01) appear to be part of three different configurations. B*066:01 is observed with B*067:01 and B*068:01 in Burmese macaques (Table 5, haplotypes 26 and 27), whereas in Indian macaques, there is one B haplotype that combines all three B alleles (Fig. 2, haplotype 12). Therefore, it is conceivable that an ancient recombination process built up that haplotype 12 in Indian rhesus macaques or, vice versa, the two Burmese haplotypes. However, the possibility cannot be excluded that the respective B loci of the Burmese rhesus macaques have been missed by Sanger sequencing and will show up in next-generation sequencing methods.

Microsatellite typing and subsequent sequencing has allowed definition of 15 different Burmese DRB haplotypes (Table 6), three of which are identical to DRB haplotypes of Indian rhesus macaques (Fig. 3 and Table 6; haplotypes 1a, 3a and 3f, bold), and one is nearly identical (Fig. 3, haplotype 15 and Table 6: haplotype 15b). Haplotype 3f is frequently observed in both populations. Only one allele (DRB1*03:09), which is part of the most common Indian DRB region configuration 4 (Fig. 3), is observed together with two different alleles on haplotype 22 in Burmese macaques. Since both haplotypes are the most frequent ones in the respective macaque populations, these haplotypes may also be built up by recombination-like events.

Extended haplotypes in Burmese rhesus macaques

In addition to the core MHC, the class II loci DQA1 and DQB1 have also been defined in Burmese rhesus macaques. Eleven DQA1 and 13 DQB1 alleles have been observed, which are similar or sometimes identical to the DQ alleles that are detected in Indian animals. Twelve Mamu-DQA1/DQB1 pairs could be defined, of which those that are observed frequently in Indian monkeys are also present in Burmese macaques (Fig. 5, orange blocks). Most DQ combinations, however, are different if one compares monkeys of Burmese and Indian origins, confirming the observation that DQ alleles and combinations are strongly origin specific (Fig. 5, yellow and turquoise blocks) (Doxiadis et al. 2003). In total, 24 founder haplotypes of Burmese monkeys could be defined for their Mamu-A/B/DRB/DQ content, 22 of which represent different combinations (Table 7). There is only one Burmese Mhc haplotype (B 4052, Table 7, bold), of which the A, B, DRB and DQ types are also detected separately in Indian macaques. The same A–B–DRB–DQ combination on one haplotype, however, has not been observed in the studied Indian cohort. Thus, no extended Burmese Mhc haplotype is identical to haplotypes observed in Indian rhesus macaques.

Discussion

Although a lower number of Burmese rhesus macaques has been studied in comparison to Indian rhesus monkeys, the total of A, B, or DRB haplotypes encountered in both populations is nearly identical (e.g., 17 Indian Mamu-A [Fig. 1] versus 15 Burmese Mamu-A [Table 4] haplotypes). The number of different Indian Mamu-A, Mamu-B or Mamu-DRB haplotypes is even lower when compared to those in cynomolgus macaques. In a population of Indonesian cynomolgus monkeys, which was much smaller than the Indian rhesus macaque panel, more Mafa-A, Mafa-B and Mafa-DRB haplotypes have been observed (e.g., 17 Indian Mamu-A versus 29 Mafa-A haplotypes) (Otting et al. 2012). Furthermore, Mhc typing of Chinese rhesus macaques as well as Burmese macaques from other breeding colonies has shown that the high degree of Mamu-A and Mamu-B variation detected in these animals is comparable to the variation observed in cynomolgus monkeys (Li et al. 2012; Liu et al. 2012; Naruse et al. 2010; Otting et al. 2007; Otting et al. 2008). In contrast, the low degree of A, B and DRB variation observed in Indian rhesus macaques is also detected for single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in these monkeys (Ferguson et al. 2007; Smith and McDonough 2005). All results are in accord with the notion that the Chinese population expanded by a factor of more than three and separated from the Indian population ~162 thousand years ago. After separating, the Indian population maintained its ancestral population size until ~50 to 20 thousand years ago, when it was reduced by a factor of four, probably owing to a severe bottleneck due to geographic events like desiccation and/or a subsequent onset of glacial conditions (Hernandez et al. 2007; Smith and McDonough 2005). Thus, the reduced number of A, B and DRB haplotypes in Indian rhesus macaques most likely does not reflect a sampling bias. However, this possibility cannot be completely excluded without sampling of wild-caught rhesus monkeys from various parts of India.

According to the low number of A, B and DRB region variation, one would expect the number of core Mhc-A/B/DRB haplotypes defined in Indian rhesus monkeys to be lower than the number of haplotypes observed in Burmese rhesus or in Indonesian cynomolgus macaques. This, however, is not the case; the Indonesian cynomolgus macaque colony, based on ~28 founder animals, possesses 32 different Mhc haplotypes, and in Indian rhesus macaques, originating from ~140 founders, a comparable number of different haplotypes (i.e. 140) have been defined. This approximation can be confirmed by a random sampling of 32 of the 176 Indian Mhc founder haplotypes, 30 of which turned out to be dissimilar (Suppl. Table 5). Thus, the number of different Mhc haplotypes in Indian rhesus macaques is nearly as high as in Indonesian cynomolgus monkeys. However, nearly every haplotype has a unique Mafa-A, Mafa-B and Mafa-DRB pattern due to allelic variation and different region configurations, whereas in Indian rhesus macaques Mhc haplotypes generate their diversity by a recombination of a relatively small number of A, B and DRB segments.

Additionally, the GLD between each pair of Mhc loci/regions of Indian rhesus macaques shares some similarities with certain Mhc loci in humans with respect to a highly significant GLD between DRB, DQA and DQB. Moreover, as in humans, GLD was detected between A and B on the one hand, and B and DRB on the other hand. However, Indian rhesus macaques showed significant GLD between DPB1 and the other three class II loci/regions, whilst in humans, such a linkage has not been consistently observed between DPB1 and any other loci (Sanchez-Mazas et al. 2000). This may be due to differences in recombination hotspots. As no pairs of loci exist with more than three haplotypes, no meaningful GLD can be detected in cynomolgus monkeys. As observed in our cynomolgus macaque panel of Indonesian origin, Mhc haplotypes with unique A, B, and DRB patterns are also described in cynomolgus macaques of other origins and in Chinese rhesus macaques (Karl et al. 2008; Otting et al. 2007; Saito et al. 2012). These results confirm LD measurements made by the correlation coefficient of alleles from frequency-matched SNPs. The SNP data showed that in Indian rhesus macaques, the LD extends much further than LD observed in European humans, whereas the Chinese rhesus macaque population shows little LD, even for SNPs that are physically very close (Hernandez et al. 2007). Although the different Mhc haplotypes of Indian rhesus monkeys are most probably a result of recombination-like events between the A, B and DR regions, only ten crossing-over events have been mapped within the core MHC of the >2,300 Indian haplotypes analysed, of which five are A–B and four are B–DRB recombinations (one remained undefined). Thus, the recombination rate in Indian rhesus macaques seems to be slightly lower for A–B and much lower for B–DRB than in humans, where recombination frequencies of 0.21 and 0.94 for A–B and B–DRB, respectively, have been described (Martin et al. 1995a, b). As a consequence, the observed Indian Mhc haplotypes appear to be old entities, which were already present in the founder animals. Thus, recombination-like events were gathered over long evolutionary time spans, one of which most likely started to occur in the distant past and within a reduced founder population. There is no evidence that recombination frequencies in Indian rhesus macaques as such differ from those in other macaque species or in rhesus macaques of other origins. Additionally, selection pressure may have given advantage to the offspring of animals in which a recombination had taken place. This phenomenon is also observed in cynomolgus macaques from the island of Mauritius, where seafarers introduced a small founder population of animals ~500 years ago. Six highly frequent Mhc haplotypes appear to account for almost all Mhc diversity in those monkeys, in which the offspring after ~100 generations show about 30 % recombinants of these original Mhc haplotypes (Mee et al. 2009; Wiseman et al. 2007). Similar observations were made in chimpanzees, which experienced a selective sweep targeting the MHC region (de Groot et al. 2008b; de Groot et al. 2002). Thus, recombination-like processes appear to be a mechanism whereby a diminished genetic repertoire in an isolated and small founder population may be expanded. As a consequence, at the population level, the animals possess different haplotypes warranting the possibility that a wide range of adaptive immune responses may be directed to one and the same, as well as to various, pathogens.

References

Averdam A, Seelke S, Grutzner I, Rosner C, Roos C, Westphal N, Stahl-Hennig C, Muppala V, Schrod A, Sauermann U, Dressel R, Walter L (2007) Genotyping and segregation analyses indicate the presence of only two functional MIC genes in rhesus macaques. Immunogenetics 59:247–251

Benjamini Y, and,Yekutieli D (2001) The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Annals of Statistics1165-1188

Blancher A, Tisseyre P, Dutaur M, Apoil PA, Maurer C, Quesniaux V, Raulf F, Bigaud M, Abbal M (2006) Study of cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis) MhcDRB (Mafa-DRB) polymorphism in two populations. Immunogenetics 58:269–282

Blancher A, Aarnink A, Tanaka K, Ota M, Inoko H, Yamanaka H, Nakagawa H, Apoil PA, Shiina T (2012) Study of cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis) Mhc DRB gene polymorphism in four populations. Immunogenetics 64:605–614

Bonhomme M et al (2008) Genomic plasticity of the immune-related Mhc class I B region in macaque species. BMC Genomics 9:514

Bontrop RE, Otting N, Slierendregt BL, Lanchbury JS (1995) Evolution of major histocompatibility complex polymorphisms and T-cell receptor diversity in primates. Immunol Rev 143:33–62

Bontrop RE, Otting N, de Groot NG, Doxiadis GG (1999) Major histocompatibility complex class II polymorphisms in primates. Immunol Rev 167:339–350

Boyson JE, Shufflebotham C, Cadavid LF, Urvater JA, Knapp LA, Hughes AL, Watkins DI (1996) The MHC class I genes of the rhesus monkey. Different evolutionary histories of MHC class I and II genes in primates. J Immunol 156:4656–4665

Budde ML, Wiseman RW, Karl JA, Hanczaruk B, Simen BB, O'Connor DH (2010) Characterization of Mauritian cynomolgus macaque major histocompatibility complex class I haplotypes by high-resolution pyrosequencing. Immunogenetics 62:773–780

Campbell KJ, Detmer AM, Karl JA, Wiseman RW, Blasky AJ, Hughes AL, Bimber BN, O'Connor SL, O'Connor DH (2009) Characterization of 47 MHC class I sequences in Filipino cynomolgus macaques. Immunogenetics 61:177–187

Dawkins R, Leelayuwat C, Gaudieri S, Tay G, Hui J, Cattley S, Martinez P, Kulski J (1999) Genomics of the major histocompatibility complex: haplotypes, duplication, retroviruses and disease. Immunol Rev 167:275–304

Daza-Vamenta R, Glusman G, Rowen L, Guthrie B, Geraghty DE (2004) Genetic divergence of the rhesus macaque major histocompatibility complex. Genome Res 14:1501–1515

de Groot N, Doxiadis GG, De Groot NG, Otting N, Heijmans C, Rouweler AJ, Bontrop RE (2004) Genetic makeup of the DR region in rhesus macaques: gene content, transcripts, and pseudogenes. J Immunol 172:6152–6157

de Groot N, Doxiadis GG, de Vos-Rouweler AJ, de Groot NG, Verschoor EJ, Bontrop RE (2008a) Comparative genetics of a highly divergent DRB microsatellite in different macaque species. Immunogenetics 60:737–748

de Groot NG, Otting N, Doxiadis GG, Balla-Jhagjhoorsingh SS, Heeney JL, van Rood JJ, Gagneux P, Bontrop RE (2002) Evidence for an ancient selective sweep in the MHC class I gene repertoire of chimpanzees. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:11748–11753

de Groot NG, Heijmans CM, de Groot N, Otting N, de Vos-Rouweller AJ, Remarque EJ, Bonhomme M, Doxiadis GG, Crouau-Roy B, Bontrop RE (2008b) Pinpointing a selective sweep to the chimpanzee MHC class I region by comparative genomics. Mol Ecol 17:2074–2088

de Groot NG, Heijmans CM, de Groot N, Doxiadis GG, Otting N, Bontrop RE (2009) The chimpanzee Mhc-DRB region revisited: gene content, polymorphism, pseudogenes, and transcripts. Mol Immunol 47:381–389

Doxiadis GG, Otting N, de Groot NG, Noort R, Bontrop RE (2000) Unprecedented polymorphism of Mhc-DRB region configurations in rhesus macaques. J Immunol 164:3193–3199

Doxiadis GG, Otting N, de Groot NG, Bontrop RE (2001) Differential evolutionary MHC class II strategies in humans and rhesus macaques: relevance for biomedical studies. Immunol Rev 183:76–85

Doxiadis GG, Otting N, de Groot NG, de Groot N, Rouweler AJ, Noort R, Verschoor EJ, Bontjer I, Bontrop RE (2003) Evolutionary stability of MHC class II haplotypes in diverse rhesus macaque populations. Immunogenetics 55:540–551

Doxiadis GG, Rouweler AJ, de Groot NG, Louwerse A, Otting N, Verschoor EJ, Bontrop RE (2006) Extensive sharing of MHC class II alleles between rhesus and cynomolgus macaques. Immunogenetics 58:259–268

Doxiadis GG, de Groot N, Claas FH, Doxiadis II, van Rood JJ, Bontrop RE (2007a) A highly divergent microsatellite facilitating fast and accurate DRB haplotyping in humans and rhesus macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:8907–8912

Doxiadis GG, Heijmans CM, Otting N, Bontrop RE (2007b) MIC gene polymorphism and haplotype diversity in rhesus macaques. Tissue Antigens 69:212–219

Doxiadis GG, de Groot N, Dauber EM, van Eede PH, Fae I, Faner R, Fischer G, Grubic Z, Lardy NM, Mayr W, Palou E, Swelsen W, Stingl K, Doxiadis II, Bontrop RE (2009a) High resolution definition of HLA-DRB haplotypes by a simplified microsatellite typing technique. Tissue Antigens 74:486–493

Doxiadis GG, Heijmans CM, Bonhomme M, Otting N, Crouau-Roy B, Bontrop RE (2009b) Compound evolutionary history of the rhesus macaque MHC class I B region revealed by microsatellite analysis and localization of retroviral sequences. PLoS One 4:e4287

Doxiadis GG, de Groot N, Otting N, Blokhuis JH, Bontrop RE (2011) Genomic plasticity of the MHC class I A region in rhesus macaques: extensive haplotype diversity at the population level as revealed by microsatellites. Immunogenetics 63:73–83

Doxiadis GG, de Vos-Rouweler AJ, de Groot N, Otting N, Bontrop RE (2012) DR haplotype diversity of the cynomolgus macaque as defined by its transcriptome. Immunogenetics 64:31–37

Excoffier L, Lischer HE (2010) Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol Ecol Resour 10:564–567

Ferguson B et al (2007) Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) distinguish Indian-origin and Chinese-origin rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). BMC Genomics 8:43

Gaudieri S, Leelayuwat C, Townend DC, Kulski JK, Dawkins RL (1997) Genomic characterization of the region between HLA-B and TNF: implications for the evolution of multicopy gene families. J Mol Evol 44(Suppl 1):S147–S154

Greene JM et al (2011) Differential MHC class I expression in distinct leukocyte subsets. BMC Immunol 12:39

Guo SW, Thompson EA (1992) A Monte Carlo method for combined segregation and linkage analysis. Am J Hum Genet 51:1111–1126

Hernandez RD, Hubisz MJ, Wheeler DA, Smith DG, Ferguson B, Rogers J, Nazareth L, Indap A, Bourquin T, McPherson J, Muzny D, Gibbs R, Nielsen R, Bustamante CD (2007) Demographic histories and patterns of linkage disequilibrium in Chinese and Indian rhesus macaques. Science 316:240–243

Karl JA, Wiseman RW, Campbell KJ, Blasky AJ, Hughes AL, Ferguson B, Read DS, O'Connor DH (2008) Identification of MHC class I sequences in Chinese-origin rhesus macaques. Immunogenetics 60:37–46

Khazand M, Peiberg C, Nagy M, Sauermann U (1999) Mhc-DQ-DRB haplotype analysis in the rhesus macaque: evidence for a number of different haplotypes displaying a low allelic polymorphism. Tissue Antigens 54:615–624

Kita YF, Hosomichi K, Kohara S, Itoh Y, Ogasawara K, Tsuchiya H, Torii R, Inoko H, Blancher A, Kulski JK, Shiina T (2009) MHC class I A loci polymorphism and diversity in three Southeast Asian populations of cynomolgus macaque. Immunogenetics 61:635–648

Kulski JK, Gaudieri S, Martin A, Dawkins RL (1999) Coevolution of PERB11 (MIC) and HLA class I genes with HERV-16 and retroelements by extended genomic duplication. J Mol Evol 49:84–97

Kulski JK, Anzai T, Shiina T, Inoko H (2004) Rhesus macaque class I duplicon structures, organization, and evolution within the alpha block of the major histocompatibility complex. Mol Biol Evol 21:2079–2091

Li A, Wang X, Liu Y, Zhao Y, Liu B, Sui L, Zeng L, Sun Z (2012) Preliminary observations of MHC class I A region polymorphism in three populations of Chinese-origin rhesus macaques. Immunogenetics 64:887–894

Liu Y, Li A, Wang X, Sui L, Li M, Zhao Y, Liu B, Zeng L, Sun Z (2012) Mamu-B genes and their allelic repertoires in different populations of Chinese-origin rhesus macaques. Immunogenetics

Ma X, Tang LH, Qu LB, Ma J, Chen L (2009) Identification of 17 novel major histocompatibility complex-A alleles in a population of Chinese-origin rhesus macaques. Tissue Antigens 73:184–187

Martin M, Mann D, Carrington M (1995a) Corrigendum: recombination rates across the HLA complex: use of microsatellites as a rapid screen for recombinant chromosomes. Hum Mol Genet 4:423–428, (1995). Hum Mol Genet4: 2423

Martin M, Mann D, Carrington M (1995b) Recombination rates across the HLA complex: use of microsatellites as a rapid screen for recombinant chromosomes. Hum Mol Genet 4:423–428

Mee ET, Badhan A, Karl JA, Wiseman RW, Cutler K, Knapp LA, Almond N, O'Connor DH, Rose NJ (2009) MHC haplotype frequencies in a UK breeding colony of Mauritian cynomolgus macaques mirror those found in a distinct population from the same geographic origin. J Med Primatol 38:1–14

Naruse TK, Chen Z, Yanagida R, Yamashita T, Saito Y, Mori K, Akari H, Yasutomi Y, Miyazawa M, Matano T, Kimura A (2010) Diversity of MHC class I genes in Burmese-origin rhesus macaques. Immunogenetics 62:601–611

Otting N, Doxiadis GG, Versluis L, de Groot NG, Anholts J, Verduin W, Rozemuller E, Claas F, Tilanus MG, Bontrop RE (1998) Characterization and distribution of Mhc-DPB1 alleles in chimpanzee and rhesus macaque populations. Hum Immunol 59:656–664

Otting N, de Groot NG, Noort MC, Doxiadis GG, Bontrop RE (2000) Allelic diversity of Mhc-DRB alleles in rhesus macaques. Tissue Antigens 56:58–68

Otting N, de Groot NG, Doxiadis GG, Bontrop RE (2002) Extensive Mhc-DQB variation in humans and non-human primate species. Immunogenetics 54:230–239

Otting N, Heijmans CM, Noort RC, de Groot NG, Doxiadis GG, van Rood JJ, Watkins DI, Bontrop RE (2005) Unparalleled complexity of the MHC class I region in rhesus macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:1626–1631

Otting N, de Vos-Rouweler AJ, Heijmans CM, de Groot NG, Doxiadis GG, Bontrop RE (2007) MHC class I A region diversity and polymorphism in macaque species. Immunogenetics 59:367–375

Otting N, Heijmans CM, van der Wiel M, de Groot NG, Doxiadis GG, Bontrop RE (2008) A snapshot o the Mamu-B genes and their allelic repertoire in rhesus macaques of Chinese origin. Immunogenetics 60:507–514

Otting N, de Groot N, de Vos-Rouweler AJ, Louwerse A, Doxiadis GG, Bontrop RE (2012) Multilocus definition of MHC haplotypes in pedigreed cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis). Immunogenetics 64:755–765

Pendley CJ, Becker EA, Karl JA, Blasky AJ, Wiseman RW, Hughes AL, O'Connor SL, O'Connor DH (2008) MHC class I characterization of Indonesian cynomolgus macaques. Immunogenetics 60:339–351

Penedo MC, Bontrop RE, Heijmans CM, Otting N, Noort R, Rouweler AJ, de Groot N, de Groot NG, Ward T, Doxiadis GG (2005) Microsatellite typing of the rhesus macaque MHC region. Immunogenetics 57:198–209

Roger JH, van Vreeswijk W, Dorf ME, Balner H (1976) The major histocompatibility complex of rhesus monkeys. VI. Serology and genetics of Ia-like antigens. Tissue Antigens 8:67–86

Saito Y, Naruse TK, Akari H, Matano T, Kimura A (2012) Diversity of MHC class I haplotypes in cynomolgus macaques. Immunogenetics 64:131–141

Sanchez-Mazas A, Djoulah S, Busson M, Monnier L, de Gouville I, Poirier JC, Dehay C, Charron D, Excoffier L, Schneider S, Langaney A, Dausset J, Hors J (2000) A linkage disequilibrium map of the MHC region based on the analysis of 14 loci haplotypes in 50 French families. Eur J Hum Genet 8:33–41

Sauermann U, Siddiqui R, Suh YS, Platzer M, Leuchte N, Meyer H, Matz-Rensing K, Stoiber H, Nurnberg P, Hunsmann G, Stahl-Hennig C, Krawczak M (2008) Mhc class I haplotypes associated with survival time in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected rhesus macaques. Genes Immun 9:69–80

Shiina T, Ota M, Shimizu S, Katsuyama Y, Hashimoto N, Takasu M, Anzai T, Kulski JK, Kikkawa E, Naruse T, Kimura N, Yanagiya K, Watanabe A, Hosomichi K, Kohara S, Iwamoto C, Umehara Y, Meyer A, Wanner V, Sano K et al (2006) Rapid evolution of major histocompatibility complex class I genes in primates generates new disease alleles in humans via hitchhiking diversity. Genetics 173:1555–1570

Slierendregt BL, Otting N, van Besouw N, Jonker M, Bontrop RE (1994) Expansion and contraction of rhesus macaque DRB regions by duplication and deletion. J Immunol 152:2298–2307

Slierendregt BL et al (1995) Identification of an Mhc-DPB1 allele involved in susceptibility to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in rhesus macaques. Int Immunol 7:1671–1679

Smith DG, McDonough J (2005) Mitochondrial DNA variation in Chinese and Indian rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Am J Primatol 65:1–25

Uda A, Tanabayashi K, Fujita O, Hotta A, Terao K, Yamada A (2005) Identification of the MHC class I B locus in cynomolgus monkeys. Immunogenetics 57:189–197

van Es AA, Balner H (1978) RhLA complex of rhesus monkeys. X. Implications of the association between D and Ia1 locus antigens. Tissue Antigens 12:279–296

Wiseman RW, Wojcechowskyj JA, Greene JM, Blasky AJ, Gopon T, Soma T, Friedrich TC, O'Connor SL, O'Connor DH (2007) Simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 infection of major histocompatibility complex-identical cynomolgus macaques from Mauritius. J Virol 81:349–361

Wiseman RW, Karl JA, Bimber BN, O'Leary CE, Lank SM, Tuscher JJ, Detmer AM, Bouffard P, Levenkova N, Turcotte CL, Szekeres E Jr, Wright C, Harkins T, O'Connor DH (2009) Major histocompatibility complex genotyping with massively parallel pyrosequencing. Nat Med 15:1322–1326

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Donna Devine for carefully editing this manuscript and Henk van Westbroek for preparing the figures. This work was supported, in part, by the NIH/NIAID project HHSN272201100013C.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Doxiadis, G.G.M., de Groot, N., Otting, N. et al. Haplotype diversity generated by ancient recombination-like events in the MHC of Indian rhesus macaques. Immunogenetics 65, 569–584 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00251-013-0707-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00251-013-0707-8