Abstract

A powerful analytical approach, namely the fractional residual power series method (FRPS), is applied successfully in this work to solving a class of fractional stiff systems. The methodology of the FRPS method gets a Maclaurin expansion of the solution in rapidly convergent form and apparent sequences based on the Caputo sense without any restriction hypothesis. This approach is tested on a fractional stiff system with nonlinearity ranging. Meanwhile, stability and convergence study are presented in the domain of interest. Illustrative examples justify that the proposed method is analytically effective and convenient, and it can be implemented in a large number of engineering problems. A numerical comparison for the experimental data with another well-known method, the reproducing kernel method, is given. The graphical consequences illuminate the simplicity and reliability of the FRPS method in the determination of the RPS solutions consistently.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Initial value problems of fractional order often appear during the modeling of many issues in the major scientific disciplines, leading us to a deeper understanding, quantification capability, and simulation of a particular feature of the real-world problems, including the disciplines of physics, biology, chemistry, engineering, and economics. Unfortunately, it seldom happens that these equations have solutions that can be expressed in closed form, so it is common to seek approximate solutions by means of numerical methods. As a matter of terminology, stiff systems form a class of mathematical problems that appear frequently in the study of many real phenomena. They were first highlighted by Curtiss and Hirschfelder [1]. They are observed in the study of chemical kinetics, aerodynamics, ballistics, electrical circuit theory and other areas of applications [2]. The mathematical stiffness of a problem reflects the fact that various processes in the considered physical models have different rates. It results from the decaying of some of the solution components being more rapidly than other components as they contain the term \(e^{-\lambda t}\), \(\lambda >0\). However, many numerical and analytical techniques have been employed recently for solving stiff systems of ordinary differential equations including the homotopy perturbation method [3], the block method [4], the multistep method [5], and the variational iteration method [6]. Examples of another mathematical models and effective numerical solutions can be found in [7,8,9].

In the last decades, the topic of fractional calculus has attracted the attention of numerous researchers for its considerable importance in many applications such as fluid dynamics, viscoelasticity, physics, entropy theory and vibrations [10,11,12,13,14]. In this regard, many differential equations of integer order were generalized to fractional order, as well as various methods were developed to solve them. Recently, the Atangana-Baleanu fractional concept has been suggested as a novel fractional operator in the Liouville–Caputo sense based on the generalized Mittag-Leffler function; such fractional operator is with a non-singular and non-local kernel that has been introduced in order to better describe complex physical problems that follow at the same time the power and exponential decay law; see for example [15,16,17,18,19]. Thereby, approximate and analytical techniques have been introduced to obtain solutions of fractional stiff systems such as the homotopy analysis method [20], the homotopy perturbation method [21], and the multistage Bernstein polynomial method [22].

For the first time, this paper aims to utilize the residual power series (RPS) algorithm for solving fractional order stiff systems of the following form:

subject to the initial condition

where \(t\geq 0\), \(a_{i}\) are real finite constants, \(f_{i}: [0,\infty ) \times \mathbb{R}^{m} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\), \(i=1,2, \dots ,m\), are continuous real-valued functions on the domain of interest, which can be linear or nonlinear, \(D^{\beta _{i}}\) is the Caputo derivative fractional order \(\beta _{i}\), \(i=1,2, \dots ,m\), \(m \in \mathbb{N}\), and \(u_{i} ( t )\) are unknown analytical functions to be determined. Here, we assume that the fractional stiff systems (1.1) and (1.2) has unique smooth solution for \(t\geq 0\).

The RPS technique has been used in providing approximation numerical solutions for certain class of differential equations under uncertainty [23]. Later, the generalized Lane-Emden equation has been investigated numerically by utilizing the RPS method. Also, the method was applied successfully in solving composite and non-composite fractional DEs, and in predicting and representing multiplicity solutions to fractional boundary value problems [24, 25]. Furthermore, [26,27,28,29] assert that the RPS method is easy and powerful to construct power series solution for strongly linear and nonlinear equations without terms of perturbation, discretization, and linearization. Unlike the classical power series method, the FRPS method distinguishes itself in several important aspects such that it does not require making a comparison between the coefficients of corresponding terms and a recursion relation is not needed and provides a direct way to ensure the rate of convergence for series solution by minimizing the residual error related.

Bearing these ideas in mind, this work is organized as follows. In the next section, some basic definitions and preliminary remarks related to fractional calculus and generalized Taylor’s formula are described. Section 3 is devoted to establishing the FRPS algorithm for obtaining the approximate solutions for a class of stiff system of fractional order. Meanwhile, a description of the proposed method is presented. Stability and convergence analyses are also presented. Several numerical applications are given in Sect. 4 to illustrate the simplicity, accuracy, applicability and reliability of the presented method. Further, a comparison between the numerical results of the FRPS method and another approximate method, namely, the reproducing kernel Hilbert space method, has been given. Finally, a brief conclusion is given in the last section.

2 Fundamentals concepts

The purpose of this section is to present some basic definitions and facts related to fractional calculus and fractional power series, which are used in subsequent sections of this study.

Definition 2.1

([30])

The Riemann–Liouville fractional integral operator of order \(\beta >0\) is defined by

For \(\beta =0\), it yields \(( J_{a}^{\beta } u ) ( t ) =u(t)\).

Definition 2.2

([30])

For \(n-1<\beta <n\), \(n \in \mathbb{N}\). The Caputo fractional derivative operator of order β is defined by

Specially, \(D_{a}^{\beta } u ( t ) = u^{(n)} (t)\) for \(\beta =n\).

The operators \(D_{a}^{\beta }\) and \(J_{a}^{\beta }\) satisfy the following properties:

Definition 2.3

([26])

A power series (PS) expansion at \(t= t_{0}\) of the following form:

for \(n-1<\beta \leq n\), \(n \in \mathbb{N} \) and \(t\leq t_{0}\), is called the fractional power series (FPS).

Theorem 2.1

([25])

There are only three possibilities for the FPS \(\sum_{m=0}^{\infty } a_{m} (t- t_{0} )^{m\beta }\), which are:

-

(1)

The series converges only for \(t= t_{0}\). That is; the radius of convergence equals zero.

-

(2)

The series converges for all \(t\geq t_{0}\). That is; the radius of convergence equals ∞.

-

(3)

The series converges for \(t\in [ t_{0}, t_{0} +R ) \), for some positive real number R and diverges for \(t> t_{0} +R\). Here, R is the radius of convergence for the FPS.

Theorem 2.2

([25])

Suppose that \(u(t)\) has a FPS representation at \(t= t_{0}\) of the form

If \(u(t)\in C[ t_{0}, t_{0} +R)\), and \(D^{m\beta } u ( t ) \in C( t_{0}, t_{0} +R)\), for \(m=0,1,2,\dots \), then the coefficients \(c_{m}\) will be of the form \(c_{m} = \frac{\mathcal{D}_{t}^{m\beta } u ( t_{0} )}{\varGamma ( m\beta +1 )} \), where \(\mathcal{D}^{m\beta } = \mathcal{D}^{\beta } \cdot \mathcal{D}^{\beta } \cdots \mathcal{D}^{\beta }\) (m times).

3 Fractional residual power series method

In this section, we are intending to use the FRPS method for solving a class of stiff systems of fractional order described in (1.1) and (1.2) through substituting the FPS expansions within truncation residual functions will be used. To do so, we assume that the FPS solution of the fractional stiff systems (1.1) and (1.2) at \(t=0\) has the following form:

The aim of the FRPS algorithm is obtaining a supportive approximate solution to the proposed model. Thus, by using the initial conditions in Eq. (1.2), \(u_{i} ( 0 ) = a_{i,0}\), as initial iterative approximation of \(u_{i} ( t )\), Eq. (3.1) can be written as

Consequently, the suggested solution \(u_{i} ( t )\) can be approximated by the following kth-truncated series:

According to the RPS algorithm, the residual function will be defined as

Therefore, the kth-residual function \(\operatorname{Res} {u_{i,k}} ( t )\), for \(k=1,2,3,\dots ,n\), can be given by

As in [25,26,27], we have \(\operatorname{Res} {u_{i}} ( t ) =0\), and \(\lim_{k\rightarrow \infty } \operatorname{Res} {u_{i,k}} ( t ) = \operatorname{Res} {u_{i}} ( t )\), for each \(t\geq 0\). As a matter of fact, this yields \(D^{n\beta _{i}} \operatorname{Res} {u_{i,k}} ( t ) =0\) for \(n=0,1,2,\dots ,k\), \(i=1,2,\dots ,m\), and \(D^{n\beta _{i}} \operatorname{Res} {u_{i}} ( 0 ) = D^{n\beta _{i}} \operatorname{Res} {u_{i,k}} ( 0 ) =0\). As a result, to determine the unknown coefficients of Eq. (3.3), one can seek the solution of the following fractional equation:

To illustrate the basic idea of the FRPS algorithm for finding the first unknown coefficient \(a_{i,1}\), we substitute \(u_{i,1} ( t ) = a_{i,0} + a_{i,1} \frac{t^{\beta _{i}}}{\varGamma (1+ \beta _{i} )}\) in the kth-residual function Eq. (3.5) with \(k=1\), \(\operatorname{Res} {u_{i,1}} ( t )\), to get

Based on Eq. (3.6) and then using the fact \(\operatorname{Res} {u_{i,1}} ( 0 ) =0\), it yields \(a_{i,1} = f_{i} ( 0, a_{1,0}, a_{2,0}, \dots , a_{m,0} )\). Therefore, the first FRPS approximated of IVPs (1.1) and (1.2) will be

Likewise, to obtain the second unknown coefficient \(a_{i,2}\), we substitute \(u_{i,2} ( t ) = a_{i,0} + a_{i,1} \frac{t ^{\beta _{i}}}{\varGamma (1+ \beta _{i} )} + a_{i,2} \frac{t^{2\beta _{i}}}{ \varGamma (1+ 2\beta _{i} )}\) in the kth-residual function Eq. (3.5) with \(k=2\), \(\operatorname{Res} {u_{i,2}} ( t )\), to get

Therefore, applying the operator \(D^{\beta _{i}}\) on \(\operatorname{Res} {u_{i},2} ( t )\) will show that

Consequently, by using the fact \(D^{\beta _{i}} \operatorname{Res} {u_{i,2}} ( 0 ) =0\), the second unknown coefficient \(u_{i,2}\) will be given by \(u_{i,2} = f_{i} ( 0, a_{1,1}, a_{2,1}, \dots , a_{m,1} )\). Therefore, the second FRPS approximated of IVPs (1.1) and (1.2) will be as

By repeating the same routine until arbitrary order, the other unknown coefficients, \(a_{i,k}\), will be obtained [31, 32].

Lemma 3.1

Suppose that \(u ( t ) \in C [t_{0}, t _{0} +R)\), \(R>0\), \(D_{t_{0}}^{j\beta } u(t)\in C( t_{0}, t_{0} +R)\), and \(0<\beta \leq 1\). Then, for any \(j \in \mathbb{N} \), we have

Proof

Using property (2.5) of the fractional integral operator, we can write

Applying (2.7) for \(( J_{t_{0}}^{j\beta } D_{t_{0}}^{j\beta } ) ( D_{t_{0}}^{\beta } u ) ( t )\), we get

□

Theorem 3.1

Let \(u ( t )\) has the FPS in (2.8) with radius of convergence \(R>0\), and suppose that \(u ( t ) \in C [t_{0}, t_{0} +R)\), \(D_{t_{0}}^{j\beta } u ( t ) \in C ( t_{0}, t_{0} +R )\) for \(j=0,1,2, \dots , N+1\). Then

where \(u_{N} ( t ) = \sum_{j =0}^{{N}} \frac{D _{t_{0}}^{j\beta } u ( t_{0} )}{\varGamma (j\beta +1)} (t- t _{0} )^{j\beta }\) and \(R_{N} ( \zeta ) = \frac{D_{t_{0}} ^{(N+1)\beta } u ( \zeta )}{\varGamma ((N+1)\beta +1)} (t- t _{0} )^{(N+1)\beta }\), for some \(\zeta \in ( t_{0},t)\).

Proof

First, we notice that

Using Lemma 3.1, we get

So,

But

Finally, we substitute in (3.8) to get (3.7). □

Remark 1

The formula of \(u_{N} ( t ) \) in the previous theorem gives an approximation of \(u ( t )\), and \(R_{N} ( \zeta )\) is the truncation (the remainder) error that results from approximating \(u ( t ) \) by \(u_{N} ( t ) \). Moreover, if \(\vert D_{t_{0}}^{(N+1) \beta } u ( \zeta ) \vert < M\) on \([ t_{0}, t_{0} +R)\), then the upper bound of the error can be computed by

Remark 2

For solving stiff system in (1.1) using the FRPS technique, we put

So, if we assume that each \(u_{i} ( t )\) has the FPS in (3.9) with radius of convergence \(R_{i} >0\), and that \(u_{i} ( t ) \in C [ 0, R_{i} )\), \(D_{0}^{j \beta _{i}} u_{i} ( t ) \in C ( 0, R_{i} )\) for \(j=0,1,2, \dots , N+1\), then \(u_{i} ( t ) = u_{iN} ( t ) + R_{iN} ( \zeta )\), ∀i. The approximate solution \(\boldsymbol{U}_{\boldsymbol{N}} ( t ) = ( u_{1N} ( t ), u_{2N} ( t ),\dots , u _{mN} ( t ) )^{T}\) converges to the exact solution \(\boldsymbol{U} ( t ) = ( u_{1} ( t ), u _{2} ( t ),\dots , u_{m} ( t ) )^{T}\) as \(N\rightarrow \infty \), \(\forall t\in [ 0,R ) \), where \(R= \min \{ R_{1}, R_{2},\dots , R_{m} \}\) and the remainder error equals

4 Numerical applications

To confirm the high degree of accurateness and efficiency of the proposed FRPS method for solving stiff systems of fractional order, numerical patterns and examples are applied in this section. Also, we make a comparison with another numerical technique, namely, the reproducing kernel Hilbert space method. The reader can find a description and applications for this method in [33,34,35,36]. Computations were performed by using the Mathematica package.

Example 4.1

Consider the following fractional-order stiff system:

subject to the initial conditions

The exact solution of this system when \(\alpha =1\) is

For \(k=1\), the first truncated power series approximations from Eq. (3.3) have the forms

and the first residual functions are

From (3.6), \(\operatorname{Res} {u_{1}} ( 0 ) =0\) and \(\operatorname{Res} {v_{1}} ( 0 ) =0\), which gives \(c_{1} =94 \) and \(d_{1} =-98\). So

For \(k=2\), the second truncated power series approximations have the forms

and the second residual functions are

From (3.6), \(D_{0}^{\alpha } \operatorname{Res} {u_{2}} ( 0 ) =0\) and \(D _{0}^{\alpha } \operatorname{Res} {v_{2}} ( 0 ) =0\), which gives \(c_{2} =-9404\) and \(d_{2} = 9412\). So

Continuing this process, we get

Some numerical results and tabulated data for \(\alpha =1\) and \(k=200\) are given in Table 1 using the FRPS method. In Table 2, numerical results for the same example using the RKHS method have been given. Figures 1 and 2 show the comparison between the behavior of the exact solution and the approximate solution using the FRPS and the RK methods, respectively, for \(\alpha =1\) with step size 0.2.

The behavior of FRPS solution of Example 4.1: __ exact; …. approximated

The behavior of RK solution of Example 4.1: __ exact; …. approximated

Example 4.2

Consider the nonlinear fractional-order stiff system:

subject to the initial conditions \(u ( 0 ) =1\), \(v ( 0 ) =1\).

The exact solution of this system when \(\alpha =1\) is \(u ( t ) = e^{-2t}\), \(v ( t ) = e^{-t}\).

For \(k=1\), the first truncated power series approximations have the forms

and the first residual functions are

From (3.6), \(\operatorname{Res} {u_{1}} ( 0 ) =0\) and \(\operatorname{Res} {v_{1}} ( 0 ) =0\), which gives \(c_{1} =-2\) and \(d_{1} =-1\). So

For \(k=2\), the second truncated power series approximations have the forms

and the second residual functions are

From (3.6), \(D_{0}^{\alpha } \operatorname{Res} {u_{2}} ( 0 ) =0\) and \(D _{0}^{\alpha } \operatorname{Res} {v_{2}} ( 0 ) =0\), which gives \(c_{2} = 4\) and \(d_{2} = 1\). So

Continuing this process, we get

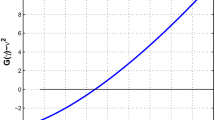

Some numerical results and tabulated data using the FRPS method for \(\alpha =1\) and \(k=20\) are given in Table 3 and Fig. 3.

The FRPS solution behavior of Example 4.2 for \(\alpha =1\) and \(k=20\)

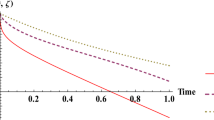

To show the accuracy of this method, the RKHS method for the same example with \(k=1000\) are applied and the results are summarized in Table 4 and Fig. 4. For fractional derivatives, we take \(k=10\) and apply the RPS method for \(\alpha _{i} =0.95+0.005i\), \(i=0, 1, \dots, 9\) as shown in Fig. 5. Figure 6 shows the results for \(\alpha _{i} =0.1+0.1i\), \(i=0, 1, \dots, 9\).

The RK solution behavior of Example 4.2 for \(\alpha =1\) and \(k=1000\)

The solutions behavior of Example 4.2 for \(\alpha _{i} =0.95+0.005i\), \(i=0, 1, \dots, 9\)

The solutions behavior of Example 4.2 for \(\alpha _{i} =0.1+0.1i\), \(i=0, 1, \dots, 9\)

5 Conclusion

In this work, we applied an analytical iterative method depending on the residual power series to get an approximate solution to a stiff system of fractional order in the Caputo sense. Numerical examples for both linear and nonlinear fractional stiff systems were given to show the effectiveness of the proposed method. By comparing our results with the exact solutions and results obtained by another numerical method, we observe that the RPS method yields an accurate approximation.

References

Curtiss, C., Hirschfelder, J.: Integration of stiff equations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 38, 235–243 (1952)

Shalashilin, V., Kuznetsov, E.: Parametric Continuation and Optimal Parametrization in Applied Mathematics and Mechanics. Springer, Dordrecht (2003)

Aminikhah, H., Hemmatnezhad, M.: An effective modification of the homotopy perturbation method for stiff systems of ordinary differential equations. Appl. Math. Lett. 24, 1502–1508 (2011)

Akinfenwa, O., Akinnukawe, B., Mudasiru, S.: A family of continuous third derivative block methods for solving stiff systems of first ordinary differential equations. J. Niger. Math. Soc. 34, 160–168 (2015)

Yakubu, D., Markus, S.: The efficiency of second derivative multistep methods for the numerical integration of stiff systems. J. Niger. Math. Soc. 35, 107–127 (2016)

Atay, M., Kilic, O.: The semianalytical solutions for stiff systems of ordinary differential equations by using variational iteration method and modified variational iteration method with comparison to exact solutions. Math. Probl. Eng. 2013, Article ID 143915 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/143915

Altawallbeh, Z., Al-Smadi, M., Komashynska, I., Ateiwi, A.: Numerical solutions of fractional systems of two-point BVPs by using the iterative reproducing kernel algorithm. Ukr. Math. J. 70(5), 687–701 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11253-018-1526-8

Baleanu, D., Golmankhaneh, A.K., Golmankhaneh, A.K.: Solving of the fractional non-linear and linear Schrodinger equations by homotopy perturbation method. Rom. J. Phys. 54, 823–832 (2009)

Jafarian, A., Ghaderi, P., Golmankhaneh, A.K.: Construction of soliton solution to the Kadomtsev–Petviashvili-II equation using homotopy analysis method. Rom. Rep. Phys. 65(1), 76–83 (2013)

Beyer, H., Kempfle, S.: Definition of physical consistent damping laws with fractional derivatives. Z. Angew. Math. Mech. 75, 623–635 (1995)

He, J.: Some applications of nonlinear fractional differential equations and their approximations. Sci. Technol. Soc. 15, 86–90 (1999)

Baleanu, D., Mustafa, O.G., Agarwal, R.P.: On the solution set for a class of sequential fractional differential equations. J. Phys. A, Math. Theor. 43(38), 385209 (2010)

Al-Smadi, M., Freihat, A., Khalil, H., Momani, S., Khan, R.A.: Numerical multistep approach for solving fractional partial differential equations. Int. J. Comput. Methods 14, 1750029 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219876217500293

Al-Smadi, M.: Simplified iterative reproducing kernel method for handling time-fractional BVPs with error estimation. Ain Shams Eng. J. 9(4), 2517–2525 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2017.04.006

Saad, K.M., Al-Sharif, E.: Analytical study for time and time-space fractional Burgers’ equation solutions. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2017, 300 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-017-1358-0

Saad, K.M., Baleanu, D., Atangana, A.: New fractional derivatives applied to the Korteweg–de Vries and Korteweg–de Vries–Burger’s equations. Comput. Appl. Math. 37, 5203–5216 (2018)

Saad, K.M., Atangana, A., Baleanu, D.: New fractional derivatives with non-singular kernel applied to the Burger’s equation. Chaos 28, 063109 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5026284

Baleanu, D., Fernandez, A.: On some new properties of fractional derivatives with Mittag-Leffler kernel. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 59, 444–462 (2018)

Abu Arqub, O., Al-Smadi, M.: Atangana–Baleanu fractional approach to the solutions of Bagley–Torvik and Painlevé equations in Hilbert space. Chaos Solitons Fractals 117, 161–167 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2018.10.013

Rani, A., Saeed, M., Ul-Hassan, Q., Ashraf, M., Khan, M., Ayub, K.: Solving system of differential equations of fractional order by homotopy analysis method. J. Sci. Arts 3(40), 457–468 (2017)

Khan, N., Jamil, M., Ara, A., Khan, N.U.: On efficient method for system of fractional equations. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2011, 303472 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/303472

Alshbool, M., Hashim, I.: Multistage Bernstein polynomials for the solutions of the fractional order stiff systems. J. King Saud Univ., Sci. 28, 280–285 (2016)

Chang, Y., Corliss, G., Atomft, G.: Solving ODE’s and DAE’s using Taylor series. Comput. Math. Appl. 28, 209–233 (1994)

Fernandez, A., Baleanu, D.: The mean value theorem and Taylor’s theorem for fractional derivatives with Mittag-Leffler kernel. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018, 86 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-018-1543-9

El-Ajou, A., Abu Arqub, O., Al-Smadi, M.: A general form of the generalized Taylor’s formula with some applications. Appl. Math. Comput. 256, 851–859 (2015)

Komashynska, I., Al-Smadi, M., Abu Arqub, O., Momani, S.: An efficient analytical method for solving singular initial value problems of nonlinear systems. Appl. Math. Inf. Sci. 10(2), 647–656 (2016)

Komashynska, I., Al-Smadi, M., Ateiwi, A., Al-Obaidy, S.: Approximate analytical solution by residual power series method for system of Fredholm integral equations. Appl. Math. Inf. Sci. 10(3), 975–985 (2016)

Moaddy, K., Al-Smadi, M., Hashim, I.: A novel representation of the exact solution for differential algebraic equations system using residual power-series method. Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2015, Article ID 205207 (2015)

Hasan, S., Al-Smadi, M., Freihet, A., Momani, S.: Two computational approaches for solving a fractional obstacle system in Hilbert space. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2019, 55 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-019-1996-5

Kilbas, A., Srivastava, H., Trujillo, J.: Theory and Applications of Fractional Differential Equations, 1st edn. Elsevier, New York (2006)

Inc, M., Korpinar, Z.S., Al Qurashi, M., Baleanu, D.: A new method for approximate solutions of some nonlinear equations: Residual power series method. Adv. Mech. Eng. 8(4), 1–7 (2016)

Akgül, A., Inc, M., Karatas, E., Baleanu, D.: Numerical solutions of fractional differential equations of Lane–Emden type by an accurate technique. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2015, 220 (2015)

Abu Arqub, O., Al-Smadi, M.: Numerical algorithm for solving time-fractional partial integrodifferential equations subject to initial and Dirichlet boundary conditions. Numer. Methods Partial Differ. Equ. 34(5), 1577–1597 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/num.22209

Al-Smadi, M., Abu Arqub, O.: Computational algorithm for solving Fredholm time-fractional partial integrodifferential equations of Dirichlet functions type with error estimates. Appl. Math. Comput. 342, 280–294 (2019)

Abu Arqub, O., Odibat, Z., Al-Smadi, M.: Numerical solutions of time-fractional partial integrodifferential equations of Robin functions types in Hilbert space with error bounds and error estimates. Nonlinear Dyn. 94(3), 1819–1834 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-018-4459-8

Cui, M., Lin, Y.: Nonlinear Numerical Analysis in the Reproducing Kernel Space. Nova Science, New York (2009)

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the responsible editor and the anonymous referees for their valuable efforts.

Availability of data and materials

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Funding

No funding sources to be declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally, and they read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Freihet, A., Hasan, S., Al-Smadi, M. et al. Construction of fractional power series solutions to fractional stiff system using residual functions algorithm. Adv Differ Equ 2019, 95 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-019-2042-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-019-2042-3