Abstract

Polygalacturonase-inhibiting proteins (PGIPs) have been shown to recognize fungal polygalacturonases (PGs), which initiate innate immunity in various plant species. Notably, the connection between rice OsPGIPs and PGs in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola (Xoc), which causes bacterial leaf streak (BLS), remains unclear. Here, we show that OsPGIP1 was strongly induced after inoculating rice with the Xoc strain RS105. Furthermore, OsPGIP1-overexpressing (OV) and RNA interference (RNAi) rice lines increased and decreased, respectively, the resistance of rice to RS105, indicating that OsPGIP1 contributes to BLS resistance. Subsequently, we generated the unique PG mutant RS105Δpg, the virulence of which is attenuated compared to that of RS105. Surprisingly, the lesion lengths caused by RS105Δpg were similar to those caused by RS105 in the OV lines compared with wild-type ZH11 with reduced Xoc susceptibility. However, the lesion lengths caused by RS105Δpg were still significantly shorter in the OV lines than in ZH11, implying that OsPGIP1-mediated BLS resistance could respond to other virulence factors in addition to PGs. To explore the OsPGIP1-mediated resistance, RNA-seq analysis were performed and showed that many plant cell wall-associated genes and several MYB transcription factor genes were specifically expressed or more highly induced in the OV lines compared to ZH11 postinoculation with RS105. Consistent with the expression of the differentially expressed genes, the OV plants accumulated a higher content of jasmonic acid (JA) than ZH11 postinoculation with RS105, suggesting that the OsPGIP1-mediated resistance to BLS is mainly dependent on the plant cell wall-associated immunity and the JA signaling pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The battle between pathogens and plants, known as the “arms race”, is the result of millions of years of coevolution (Boller and He 2009). Similar to the skin of animals, the plant cell surface is the first layer of physical and chemical protection against invading pathogens. This first protective layer includes the plant waxy cuticles and the release of plant metabolites that act as anti-microbial compounds (Jones and Dangl 2006; Malinovsky et al. 2014). Unlike animals with circulating antibodies against pathogens, plants have developed a two-tiered innate immune systems: pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) and effector-triggered immunity (ETI) (Jones and Dangl 2006; Li et al. 2016). Beyond the cuticle layer, the plant cell wall is the second barrier that prevents the colonization of phytopathogenic organisms (Bellincampi et al. 2014). The plant cell well is a dynamic structure that is mainly composed of a framework of cellulose microfibrils that are cross-linked to each other by heteropolysaccharides to create a rigid structural framework (Lampugnani et al. 2018). To penetrate the plant cell wall and colonize their host, plant pathogens produce cell wall-degrading enzymes (CWDEs), including pectin methylesterases (PMEs), hemicellulases, cellulase and polygalacturonases (PGs) (Kalunke et al. 2015). PGs are secreted by fungi, bacteria and insects at the early stage of infection and serve as a pathogenicity factor. This hydrolytic enzyme cleaves the α-(1–4) linkages between the D-galacturonic acid residues of homogalacturonan to degrade cell wall polysaccharides and facilitate the availability of host nutrients (Kalunke et al. 2015; Bacete et al. 2018).

To prevent the degradation of the cell wall by phytopathogens and insects, plants induce the expression of CWDE inhibitors, such as polygalacturonase-inhibiting proteins (PGIPs), to block the activity of PG, delaying the hydrolysis of oligogalacturonides (Kalunke et al. 2015). PGIPs are typically plant cell wall proteins that contain ten imperfect leucine-rich repeat (LRR) motifs to form two β-sheets that interact with PGs (Di Matteo et al. 2003; Benedetti et al. 2011). In most cases, plant PGIPs show inhibitory activity against PGs in vitro, suggesting that they encode defense-related genes (Wang et al. 2015a; Kalunke et al. 2015). In addition to directly inhibiting PGs, PGIPs can form a complex with PGs, to promote the generation of oligogalacturonide (OG) fragments with low degrees of polymerization (DP) (Benedetti et al. 2015). OGs function as a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) that is recognized by the receptor wall-associated kinase 1 (WAK1) to induce host immunity (Brutus et al. 2010). Studies have indicated that the application of long or trimeric OGs activates the immune response to resist necrotrophic pathogens and nematodes (Galletti et al. 2008; Rasul et al. 2012; Davidsson et al. 2017; Shah et al. 2017).

PGIPs have been shown to be regulators of resistance to different pathogens in a variety of plants. Overexpressing PcPGIP from pear and BrPGIP2 from Brassica rapa resulted in enhanced resistance to the bacterial pathogens Xylella fastidiosa and Pectobacterium carotovorum in grapevine and Chinese cabbage, respectively (Agüero et al. 2005; Hwang et al. 2010). Numerous plant PGIPs, including PvPGIP2 from Phaseolus vulgaris (Sicilia et al. 2005), PGIP from tomato (Schacht et al. 2011), PGIP from bean (Borras-Hidalgo et al. 2012), GmPGIP3 from Glycine max (Wang et al. 2015a), VrPGIP2 from mungbean (Chotechung et al. 2016) and GhPGIP1 from cotton (Liu et al. 2017), play positive roles in the resistance to different fungi, partially by suppressing PG activity. In Oryza sativa, the expression of five out of seven PGIP genes is upregulated in response to Rhizoctonia solani infection, the causative agent of sheath blight (SB) of rice (Lu et al. 2012). OsPGIP1 was identified to positively regulate resistance through the direct inhibition of PGs produced by R. solani (Wang et al. 2015b; Chen et al. 2016). Furthermore, the expression of OsPGIP4 was reported to be upregulated upon bacterial pathogen infection, and overexpressing OsPGIP4 in rice enhanced the resistance of rice to bacterial leaf streak (BLS) (Feng et al. 2016).

BLS, which is caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola (Xoc), is one of the major bacterial diseases of rice, and it is difficult to control due to the lack of highly disease-resistant rice varieties (Niño-Liu et al. 2006). BLS is prevalent among southern and central China, southeast Asia and African, with increasing outbreak frequency and severity. Two sources of resistance have been documented for BLS: the qualitative resistance gene locus Xo1, which is only effective against African Xoc isolates, and the quantitative trait loci (QTL) qBlsr5a (xa5), which confers resistance to both BLS and bacterial blight of rice (Xie et al. 2014; Triplett et al. 2016). Research has shown that modifying the expression of defense-related (DR) genes alters the resistance of rice to Xoc. For example, the overexpression of the broad-spectrum disease resistance gene OsMPK6, an indole-3-acetic acid amido synthetase (GH3–2), a nucleotide binding and leucine-rich repeat domain (NLR) protein heteropairs RGA4/RGA5, OsPGIP4, OsMAPK10.2, the small heat shock protein gene OsHSP18.0-CI and the phytosulfokine receptor 1 (OsPSKR1) enhanced the resistance of rice to BLS (Shen et al. 2010; Fu et al. 2011; Feng et al. 2016; Hutin et al. 2016; Ma et al. 2017; Ju et al. 2017; Yang et al. 2019). The repression of OsWRKY45–1, a receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase (NRRB), OsImpα1a and OsImpα1b also enhanced the resistance of rice to Xoc (Tao et al. 2009; Guo et al. 2014; Hui et al. 2019).

We previously reported that overexpression of OsPGIP4 enhanced the resistance of rice to BLS (Feng et al. 2016); however, the role and mechanism of action of OsPGIP1 in rice and Xoc interactions remains unknown. In this study, we showed that OsPGIP1 expression was induced in response to Xoc. We generated OsPGIP1-overexpressing and OsPGIP1-suppressed transgenic rice and demonstrated the positive role of OsPGIP1 in the resistance of rice to BLS. Unlike previous examples of the PGIP-PGs working model, the OsPGIP1-mediated resistance to BLS is induced by other pathogenicity factors in addition to the PG of Xoc. Moreover, our results showed that the OsPGIP1-mediated immune response to BLS was related to pathogen-related (PR) gene and cell wall-associated gene expression through RNA sequencing analysis and jasmonic acid (JA) accumulation. In general, our results demonstrate the benefits of utilizing OsPGIP1 in breeding disease-resistant rice that will be resistant to BLS and SB caused by bacterial and fungal pathogens, respectively.

Methods

Plant Materials, Bacterial Strains, Plasmids and Rice Transformation

The BLS-susceptible rice variety Zhonghua 11 (ZH11, Oryzae sativa L. ssp. japonica) and moderately resistant variety Acc8558 (O. sativa L. ssp. indica), the donor of the BLS-resistance quantitative trait locus qBlsr5a that contains xa5, OsPGIP1 and OsPGIP4 (Chen et al. 2006; Xie et al. 2014; Feng et al. 2016), were grown in a greenhouse at 26 ± 2 °C, with a photoperiod of 16 h and relative humidity of 85% to 100%, as previously reported (Feng et al. 2016). The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. To generate the OsPGIP1 overexpression transgenic lines, the complete OsPGIP1 gene was cloned into plasmid pU1301, directly after the maize ubiquitin constitutive promoter via Kpn I and BamH I restriction sites to make pU1301::OsPGIP1. To generate the OsPGIP1-silenced rice, an OsPGIP1 gene fragment 570 bp in size was inserted into pDS1301 using Kpn I and BamH I, and a second inverted fragment was inserted using Sac I and Spe I to generate ds1301::OsPGIP1, which mediated RNA interference by expressing double-stranded RNA in rice (Li et al. 2013). The recombinant plasmids of pU1301::OsPGIP1 and ds1301::OsPGIP1 were introduced into A. tumefaciens strain EHA105.

Gene Expression Analysis

Infected leaves were collected at 0, 2, 4, 8, 24, and 96 h postinoculation (hpi) for ZH11 and at 0, 6, 24, 48, and 96 hpi for Acc8558. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany). OsPGIP1 expression was confirmed in different rice varieties (ZH11 and Acc8558) inoculated with RS105 using quantitative PCR (qPCR). First strand cDNA was generated using ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix with gDNA Remover kit (TOYOBO, Japan). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on a QuantStudio™ 6 Flex Real-Time System (Applied Biosystems, USA) with KOD SYBR qPCR Mix (TOYOBO). The qPCR program followed that described in Ju et al. 2017, using OsACTIN (LOC_Os03g50890) as an internal control (Additional file 2: Table S1).

Manipulation of the Polygalacturonase Gene in X. oryzae pv. oryzicola

To generate the knockout mutation of PG in Xoc, we used the RS105 putative polygalacturonase sequence (GenBank accession No. WP_014503099) to design the primers XocPG-up and XocPG-down (Additional file 2: Table S1) that amplified a 935 bp fragment upstream and a 963 bp fragment downstream of the gene from RS105. The two fragments were fused into one fragment and then cloned into pK18mobsacB using BamH I and Hind III to generate the plasmid pK18mobsacB-PG. To generate a homologous recombination mutant, we introduced the plasmid pK18mobsacB-PG into RS105 competent cells as previously described (Zou et al. 2012). Single crossover mutants were selected using kanamycin as a selective marker, and colonies that grew were then transferred to sucrose screening medium to select a double exchange unmarked mutant. The RS105Δpg strain resulting from homologous recombination was further confirmed by PCR and DNA sequencing.

To complement RS105Δpg, a 2285 bp genomic DNA fragment that included the promoter and full coding sequence of the protein was amplified using pairs of forward and reverse primers for XocPG-CP (Additional file 2: Table S1). The fragment was double digested with EcoR I and Hind III and cloned into pVSP61. The recombined plasmid was transformed into RS105Δpg competent cells to obtain the complement RS105Δpg-CP.

Pathogen Inoculation Growth Curve and Resistance Assessment

The Xoc strains RS105, RS105Δpg and RS105Δpg-CP were grown on polypeptone-sucrose-agar medium (10 g l− 1 polypeptone, 1 g l− 1 glutamic acid, 10 g l− 1 sucrose and 15 g l− 1 agar) at 28 °C for 3 days and then resuspended in sterile water to an OD600 of 0.5 (Ju et al. 2017). Fully expanded leaves of four- to six-week-old rice were inoculated with a bacterial suspension of RS105, RS105Δpg or RS105Δpg-CP using a blunt end syringe. Disease severity was assessed by measuring water-soaked lesion length at 14 days postinoculation (dpi). To investigate the in planta bacterial growth, rice leaves were inoculated with a bacterial suspension of a Xoc strain, RS105, RS105Δpg or RS105Δpg-CP, at an OD600:0.1 of. Inoculated leaves were harvested and used for determining bacterial populations at 1, 4, and 7 dpi as previously described (Ju et al. 2017; Yang et al. 2019).

Yeast Two Hybrid

The 1572 bp DNA fragment of the PG gene that deleted the transmembrane domain was amplified from the RS105 genome using pairs of XocPG-BD primers (Additional file 2: Table S1) and then cloned into pGBKT7 as a bait vector BD-PG. The 870 bp DNA fragment of OsPGIP1 and 968 bp DNA fragment of OsPGIP4 that deleted the transmembrane domain were amplified using forward and reverse primers of OsPGIP1-AD and OsPGIP4-AD, respectively (Additional file 2: Table S1), from ZH11 cDNA and then cloned into pGADT7 as the prey vectors AD-OsPGIP1 and AD-OsPGIP4. The BD-PG and AD-OsPGIP1 vectors, and BD-PG and AD-OsPGIP4 vectors were cotransformed into Y2H golden yeast cells through PEG-LiAc-mediated transformation according to the instructions of the Yeastmaker Yeast Transformation System 2 (Clontech, the USA). The yeast transformants grew on double-dropout minimal base (SD/−leucine-tryptophan), and the interaction in yeast was tested by quadruple-dropout minimal base (SD/−leu-trp-ade-his) and aureobasidin A. The pGBKT7–53 and pGADT7-T vectors were used as positive controls in the yeast transformation protocol.

RNA-Seq and Analysis

As previously described (Ju et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2018), mixed RNA samples of noninfected and infected (24 hpi) leaves of ZH11 and OV-24 were used for library construction and sequencing with BGISEQ-500 by the Beijing Genomic Institution (www.genomics.org.cn, BGI, Shenzhen, China). In brief, 9 individuals of ZH11 and OV-24 were grown side-by-side in one container. After 6 weeks of growth, the rice leaves were inoculated with RS105 and collected for RNA extraction at 0 hpi and 24 hpi. For each sample, we collected approximately 100 mg of leaves from three individuals to extract total RNA with TRI reagent to form three replicates for ZH11, ZH11-RS (ZH11 inoculated with RS105 at 24 hpi), OV-24 and OV-24- RS (OV-24 inoculated with RS105 at 24 hpi). Subsequently, equal amounts of total RNA from three replicates were mixed together for library construction. The above experiments were repeated again, and the sequencing reads were collected and analyzed separately. The clean reads were aligned to the rice Nipponbare reference genome (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu). Gene expression levels were quantified via fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped (FPKM). Genes with a P-value< 0.001 and log2 (FPKM-OV-24/FPKM-ZH11 or FPKM- ZH11-RS/FPKM-ZH11 or FPKM-OV-24-RS/FPKM-OV-24) > 1 were considered differentially expressed genes (DEGs). DEGs commonly repeated in two experiments were collected for further functional analysis. Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of the DEGs in the GO database (http://www.geneontology.org/) was used to recognize the main biological functions. The two transcriptome datasets have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive Database (http://trace.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/sra) under the Accession Number PRJNA517024.

Hormone Determination and Treatment

ZH11 and OsPGIP1-overexpressing rice were grown for 6 weeks in a greenhouse and then inoculated with RS105. Inoculated and noninoculated leaves with RS105 at 24 hpi were collected separately and prepared for hormone quantification. Three biological replicates of approximately 100 mg to 150 mg leaves were used to measure the contents of SA and JA according to a previous reference (Xu et al. 2016).

Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was repeated at least three times independently. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software. Student’s t-test and least significant difference (LSD) test were used for significant analysis, and a P test value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The Expression Patterns of Seven OsPGIPs after Inoculation with Xoc RS105

There are seven OsPGIPs (OsPGIP1–7) throughout the genome of rice, of which the expression of five OsPGIPs, excluding OsPGIP6 and OsPGIP7, was strongly induced after inoculation with the fungal pathogen R. solani (Lu et al. 2012). However, the response of OsPGIPs to the bacterial pathogen Xoc remains unclear. Thus, we detected the expression of all OsPGIP members during infection with the Xoc strain RS105. The relative expression of OsPGIP1 was continuously increased during the initial 24 h after inoculation and then rapidly decreased to normal levels from 24 hpi to 96 hpi (Fig. 1a). In contrast to OsPGIP1, six other OsPGIPs showed decreased expression at 4 hpi (Fig. 1a), indicating a unique function of OsPGIP1 in BLS resistance. Moreover, OsPGIP2 and OsPGIP4 had showed the most similar expression patterns during Xoc infection, which presented a peak expression level at 8 hpi, and the expression patterns of OsPGIP3 and OsPGIP5 and of OsPGIP6 and OsPGIP7 were similar to each other (Fig. 1a). We further investigated the difference in the expression of OsPGIP1 to OsPGIP7 between the susceptible variety ZH11 and the moderately resistant variety Acc8558. OsPGIP1 had a similar expression pattern but was induced at higher levels in Acc8558 than in ZH11 (Fig. 1b). In addition, the expression patterns of OsPGIP2 and OsPGIP4 after inoculation with RS105 in Acc8558 were also similar to those in ZH11, but the expression levels were even higher in Acc8558 (Additional file 7: Figure S1). Then, we analyzed the promoter sequence of OsPGIP1, which showed several differences between ZH11 and Acc8558 (Additional file 1: Text S1). The promoter sequence of OsPGIP1 in Acc8558 contains more ethylene-responsive elements (ERE-motif) and SEB-1 binding sites (STRE-motif) but one less W-box, GATA-motif and Myc, which may respond to the higher induction of OsPGIP1 in Acc8558, than that of ZH11 (Additional file 3: Table S2). Overall, the expression pattern of OsPGIP1 upon inoculation with RS105 implied that it may be involved in resistance to Xoc.

Expression patterns of rice OsPGIPs in response to the Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola strain RS105. a Relative expression of OsPGIPs in ZH11 in response to Xoc. The gene expression levels of OsPGIP1 to OsPGIP7 were analyzed by qRT-PCR after inoculation with Xoc stain RS105 at 2, 4, 8, 24, and 96 h. b The expression of OsPGIP1 in response to RS105 at 6, 24, 48, and 96 h in the susceptible rice variety ZH11 and moderately resistant variety Acc8558. The housekeeping gene ACTIN was used to normalize the data. Error bars represent the standard deviations for three replicates. Three independent experiments were performed with the same expression pattern

OsPGIP1 Contributes to Bacterial Leaf Streak Resistance

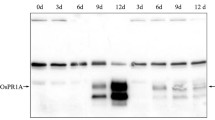

To verify that OsPGIP1 is involved in BLS resistance, we generated OsPGIP1-overexpressing and OsPGIP1-silenced transgenic lines of rice in susceptible ZH11 by A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation. A total of 29 OsPGIP1-overexpressing transgenic lines were generated in the T0 generation. Twelve of them were confirmed using the specific primers Hpt-Forward and Hpt-Reverse (Additional file 2: Table S1). Compared to the wild-type ZH11, these same 12 lines showed significantly shorter lesion lengths than after inoculation with RS105 (Additional file 8: Figure S2a). Based on the lesion length scored in the T0 generation, three lines were selected for further characterization in the T1 generation. This included the moderately resistant line pU1301::OsPGIP1–12 (1.625 ± 0.176 cm), the most resistant line pU1301::OsPGIP1–24 (1.505 ± 0.165 cm), and the weakest resistant line pU1301::OsPGIP1–29 (1.825 ± 0.226 cm) (named OV-12, OV-24 and OV-29, respectively, hereafter). As shown in Additional file 8: Figure S2b, the resistance phenotype is cosegregated with pU1301::OsPGIP1, as identified by DNA amplification in all three T1 progeny. We also observed the resistance phenotype to RS105 in the OV-12 and OV-24 lines in the T2 progeny (Fig. 2a). The relative expression level of OsPGIP1 in these lines showed approximately 1500-fold and 2000-fold enhanced expression in the OV-12 and OV-24 lines compared with that in ZH11 (Fig. 2b). Both the increased expression of OsPGIP1 and shortened lesion length were detected in OV-12 and OV-24 (Fig. 2a, c). Alternatively, OV-24 had increased resistance to RS105 compared to OV-12, and the expression level of OsPGIP1 was higher in OV-24 than in OV-12 (Fig. 2b, c). In addition, the bacterial population of RS105 in the OsPGIP1-overexpressing line OV-24 was significantly reduced compared to ZH11 (Additional file 11: Figure S5). Together, these data suggest that the overexpression of OsPGIP1 enhanced the resistance of rice to Xoc.

OsPGIP1 contributes to bacterial leaf streak resistance. a The phenotypes of the RS105 lesions that developed on ZH11 and two OsPGIP1-overexpressing lines (OV-12 and OV-24) at 14 days after infiltration. The arrows represent the boundaries of lesion expansion caused by RS105 infection. b Relative expression fold change of OsPGIP1 in OV-12 and OV-24. The expression of wild-type ZH11 was used as a control and set to 1. The housekeeping gene ACTIN was used to normalize the data. c The lesion lengths of ZH11, OV-12 and OV-24 at 14 days after inoculation with RS105. d The phenotypes of the RS105 lesions that developed on ZH11 and two OsPGIP1-suppressed lines (RNAi-7 and RNAi-10) at 14 days after infiltration. The arrows represent the boundaries of lesion expansion caused by RS105 infection. e Relative expression level of OsPGIP1 in RNAi-7, RNAi-10 and ZH11. The expression of wild-type ZH11 was used as a control and set to 1. ACTIN was an internal reference gene for normalization. f The lesion lengths of ZH11, RNAi-7 and RNAi-10 inoculated with RS105 after 14 days. Data were analyzed using a t-test. Asterisks represent statistically significant differences from the ZH11 wild type at P < 0.05

Three independent silenced transgenic lines were generated, RNAi-7, RNAi-10 and RNAi-11. These three lines were inoculated with RS105 in the T1 progeny. We observed cosegregation in these three lines, and all lines were verified as ds1301::OsPGIP1 using primers Hpt-Forward/Reverse by PCR. Furthermore, these two silenced lines were more susceptible to RS105, indicated by longer lesion lengths when compared to WT ZH11 (Additional file 9: Figure S3). Additional studies in the T2 generation of silenced plants, RNAi-7 and RNAi-10, demonstrated that OsPGIP1 mRNA was reduced in RNAi-7 and RNAi-10 by 94% and 87% compared to that in WT, respectively (Fig. 2e). The lesion length reached an average of 3.06 ± 0.26 cm and 2.84 ± 0.20 cm compared to 2.17 ± 0.10 cm in ZH11 (Fig. 2d, f). We also found that the RS105 population in the OsPGIP1-silenced line RNAi-10 was larger than that in ZH11 (Additional file 11: Figure S5). These results suggest that silencing the expression of OsPGIP1 enhanced the susceptibility of rice to BLS.

OsPGIP1 is located in the same locus as the QTL qBlsr5a in the moderately resistant variety Acc8558 (Xie et al. 2014), implying that it may play a role in qBlsr5a-mediated resistance. To test this, we generated OsPGIP1 RNAi lines. The three individual RNAi lines of the T1 generation in the Acc8558 background were more susceptible to RS105 than wild-type Acc8558 (Additional file 10: Figure S4), which supports that OsPGIP1 is a defense-related gene that contributes to BLS resistance.

A PG Works as a Facilitator of the Pathogenic Function in Xoc

Fungal PGs have been reported as virulence factors in Botrytis cinerea (ten Have et al. 1998) and Claviceps purpurea (Oeser et al. 2002). To determine whether PGs act as virulence factors in the bacteria Xoc, we generated the PG gene mutant of RS105Δpg by DNA recombination. The lesion length caused by RS105Δpg was shorter than that cause by RS105 in both the susceptible rice ZH11 and moderately resistant rice Acc8558 (Fig. 3b, c). Furthermore, we also performed a bacterial growth curve in planta of RS105 and RS105Δpg, which revealed that the populations of RS105Δpg were less than those of RS105 in both ZH11 and Acc8558 (Fig. 3d). To verify that the PG mutant was the cause of the reduced virulence, we constructed the PG complementation strain RS105Δpg-CP. Inserting a copy of the wild-type gene nto the mutant strain RS105Δpg restored the lesion lengths to the wild-type lesion lengths (2.12 ± 0.18 cm), similar to wild-type RS105 in ZH11 (2.16 ± 0.21 cm) (Fig. 3e). Thus, we conclude that PG acts as a pathogenicity factor in Xoc strain RS105.

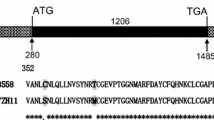

The polygalacturonase gene acts as a virulence factor of RS105 during infection in rice. a The position of the polygalacturonase (PG) gene in the Xoc RS105 genome. b The phenotype of RS105 and the PG mutant strain (RS105Δpg) on the susceptible rice variety ZH11 and moderately resistant variety Acc8558. Images were photographed 14 days after inoculation. c The statistical counting of lesion length at 14 days after inoculation with RS105 and RS105Δpg on ZH11 and Acc8558. The data were counted from over 10 plants and analyzed using a t-test (P < 0.05). Asterisks represent statistically significant differences from ZH11. d The bacterial growth curves of RS105 and RS105Δpg in ZH11 and Acc8558 rice at 1, 4, and 7 days. Significant differences were determined by t test: *P < 0.05. e Lesion length after inoculation with RS105, RS105Δpg and PG gene complementary stain (RS105Δpg-CP) at 14 days in ZH11. The letters above the bars represent the significant differences at a value of P ≤ 0.05 (LSD test). The above experiments were repeated three times with similar results

OsPGIP1-Mediated Resistance Is Induced by Other Pathogenicity Factors in Addition to PG

Previous studies demonstrated that PGIPs directly interact with fungal PGs and inhibit the PG enzyme activities that initiate OG-mediated PTI to restrict pathogen growth (Wang et al. 2015a, 2018; Benedetti et al. 2015). Although we have found that the overexpression of OsPGIP4 enhances resistance to Xoc (Feng et al. 2016), the role of OsPGIP1 in response to plant pathogenic bacteria remains unclear. To explore the possibility of direct protein-protein interactions between OsPGIP1and PG, we conducted a yeast two-hybridization experiment. No protein-protein interactions were observed under the conditions tested (Additional file 12: Figure S6). We identified PG as a pathogenicity factor in rice-Xoc interactions (Fig. 3b, c and d), and the overexpression of OsPGIP1 (Fig. 2a, b and c) increased resistance to Xoc. We questioned whether OsPGIP1 resistance was mediated in response to PG alone or if there were additional pathogen-associated molecular patterns that were perceived by this gene. To test this hypothesis, we measured the lesion lengths of ZH11, OsPGIP1 OV-12 and OsPGIP1 OV-24 caused by RS105, RS105Δpg and RS105Δpg-CP. RS105Δpg caused shorter lesions in ZH11 compared to RS105 and RS105Δpg-CP and caused similar lesion lengths in the two OsPGIP1 OV lines (Fig. 4). This indicates that the PG-dependent virulence was completely abolished by the overexpression of OsPGIP1. Moreover, compared to ZH11, in the OsPGIP1 OV lines, resistance to RS105Δpg was demonstrated (Fig. 4), indicating that OsPGIP1-mediated resistance is not only responsive to the PG in Xoc but also responsive to other virulence factors in Xoc or Xoc-induced susceptible factors in rice.

OsPGIP1-mediated resistance is complemented and induced by XocPG in addition to other Xoc pathogenicity factors. Lesion lengths of RS105, RS105Δpg and RS105Δpg-CP in ZH11 and OsPGIP1-overexpressing lines OV-12 and OV-24. The letters above the bars represent the significant differences at a value of P ≤ 0.05 (LSD test). The above experiment was repeated three times with similar results

RNA-Seq Analysis of OsPGIP1-Overexpressing Rice

To identify the genes that contribute to OsPGIP1-mediated resistance to Xoc, we performed transcriptome sequencing analysis in the OsPGIP1-overexpressing line OV-24 (T3 generation) and wild type ZH11. We found that only 138 DEGs, including 75 upregulated and 63 downregulated genes, were differentially expressed in OV-24 compared with ZH11 (Additional file 13: Figure S7a). Of the 138 DEGs, only 3 were defense-response genes, and most were predicted to be of unknown function (Additional file 13: Figure S7a). Upon inoculation with RS105, 786 and 676 DEGs were identified in ZH11-RS and OV-24-RS compared with ZH11 and OV-24, respectively. The DEGs of ZH11-RS vs. ZH11 contained 674 upregulated genes and 112 downregulated genes, while the DEGs of OV-24-RS vs. OV-24 contained 627 upregulated genes and 49 downregulated genes (Fig. 5a, b). The DEGs of ZH11-RS vs. ZH11 and OV-24-RS vs. OV-24 showed that 297 genes were commonly differentially expressed; 379 DEGs specifically responded to Xoc in OV-24-RS vs. OV-24, and 489 DEGs changed only in ZH11-RS vs. ZH11 (Additional file 13: Figure S7b). Among the 297 common DEGs, 282 and only 13 genes were upregulated and downregulated, respectively (Fig. 5a, b and Additional file 4: Table S3). Comparisons of the 138 DEGs of OV-24 vs. ZH11 with ZH11-RS vs. ZH11 or OV-24-RS vs. OV-24, 30 and 32 common DEGs were identified, respectively, and only 15 were commonly shared for both (Additional file 13: Figure S7b). More DEGs were identified after inoculation with Xoc, indicating that OsPGIP1-mediated resistance relied on enhanced gene expression upon Xoc infection.

RNA-seq analysis of differentially expressed genes between the OsPGIP1-overexpressing line (OV-24) and ZH11 in response to RS105 inoculation. a and b Venn diagram of upregulated (a) or downregulated (b) DEGs in response to RS105 at 24 h postinoculation. DEGs were considered at P value< 0.001 and |log2-fold change| > 1. ZH11-RS vs. ZH11 and OV-24-RS vs. OV-24 represent the common DEGs identified in two experimental repeats, with noninfected ZH11 and OV-24 as controls. c Heatmap analysis of the common significantly upregulated DEGs in OV-24-RS vs. OV-24 and ZH11-RS vs. ZH11. The heatmap was classified into defense response, cell wall metabolism, transcription factors (TFs), receptor-like kinases (RLKs) and ROS metabolism. The intensity of color indicates the expression level of genes from left to right, indicating higher gene expression. d The expression of the transcription factor genes, cell wall-related genes and defense response genes that were upregulated in RNA-seq analysis was evaluated by qRT-PCR in ZH11 and OV-24. The internal control gene was ACTIN. The above experiments were repeated three times with similar results

Functional Analysis of the Three Categories of DEGs in Response to Xoc in OsPGIP1-Overexpressing Rice

The results showed that 282 DEGs were upregulated in both ZH11-RS and OV-24-RS (Fig. 5a, b). A heatmap representing the analysis of the upregulated genes is shown in Fig. 5c. The GO functions of the 282 upregulated DEGs in both OV-24-RS and ZH11-RS were classified into five categories: defense response, cell wall metabolism, transcription factors, receptor-like kinases (RLKs) and ROS related (Fig. 5c). Of the 282 commonly upregulated DEGs, 143 genes showed higher expression in OV-24-RS than in ZH11-RS (Additional file 4: Table S3). Of the 345 upregulated and 34 downregulated genes specifically regulated in OV-24-RS vs. OV-24, we identified 5 genes related to defense response, 32 genes related to cell wall metabolism, 10 genes related to polysaccharide metabolism, 6 genes related to chitin catabolism and 41 genes related to oxidation-reduction (Additional file 5: Table S4 and Additional file 14: Figure S8).

It has previously been shown that combining the expression of the pathogenesis-related (PR) genes of chitinase and β-1,3-glucanase enhanced the resistance of rice to R. solani (Sridevi et al. 2008). CHIT13 (Os09g0494200) and CHIT14 (Os10g0542900), which encode chitinases, were significantly induced in OV-24 compared to ZH11 (Fig. 5c). The PR genes JIOsPR10 (Os03g0300400), RSOsPR10 (Os12g0555000) and JAmyb (Os11g0684000) respond to Magnaporthe grisea inoculation and JA treatment (Jwa et al. 2001; Hashimoto et al. 2004; Cao et al. 2015). These three PR genes had increased expression in OV-24 compared with ZH11 (Fig. 5d and Additional file 5: Table S4). PAL4 (Os02g0627100) is a positive regulator in rice broad-spectrum disease resistance (Tonnessen et al. 2015), and it was also induced in OV-24 (Fig. 5d). Cell wall metabolism is particularly involved in the biotic stress response (Le Gall et al. 2015). We also observed that the cell wall biosynthesis genes CESA7 (Os10g0467800), GLU (Os04g0497200) and GLUB (Os03g0669300) were induced in OV-24 and ZH11 (Fig. 5c). Lignin is a main complex of phenolic polymers that exist in plant cell walls and affects defense signaling in biotic stress (Gallego-Giraldo et al. 2018). We identified that a series of lignin biosynthesis genes were more highly expressed in OV-24 than in ZH11, including PAL3 (Os02g0626600), PAL6 (Os04g0518400), PAL7 (Os05g0427400) and CAD (Os03g0101600), which were also exhibited expression upregulated by qRT-PCR (Fig. 5c, d). Additionally, the cellulose synthase genes CESA1 (Os05g0176100), CESA4 (Os01g0750300), CESA5 (Os03g0837100), and CSLA3 (Os06g0230100) and lignin synthesis gene PAL3 (Os02g0626100) were upregulated only in OV-24 in addition to the common cell wall biosynthesis genes in OV-24 and ZH11 (Fig. 5c, d). In conclusion, OsPGIP1-mediated resistance to Xoc may rely on activating the expression of PR genes and cell wall-responsive genes.

Overexpression of OsPGIP1 or OsPGIP4 Caused the Accumulation of Jasmonic Acid Postinoculation with Xoc

Generally, hormones in host plants, such as SA, JA and ET, change in response to pathogen attack (Spoel and Dong 2008). The interaction between PGs and PGIPs is associated with the accumulation of OGs inducing host resistance through the hormone pathway (Benedetti et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2018). When the Fusarium phyllophilum FpPG and its cognate Phaseolus vulgaris PvPGIP2 were ectopically expressed in Arabidopsis, the accumulation of excessive SA was detected, which in turn activated the immune response (Benedetti et al. 2015). Our previous studies found that the overexpression of OsPGIP4 induced the expression of JA biosynthesis-related genes after inoculation with RS105 (Feng et al. 2016). In this study, we found that some JA-related genes were upregulated in OV-24. To determine whether JA is involved in OsPGIP1-mediated immunity to Xoc, we measured the JA and SA levels in both OsPGIP1-OV and wild-type ZH11. The SA levels were not significantly different between the control and RS105-inoculated ZH11, OV-12 and OV-24 rice plants (Fig. 6). In the noninoculated control plants, the JA levels were similar in ZH11 and two tested OsPGIP1-OV rice lines. In the RS105-inoculated plants, the JA level increased in both the ZH11 and OsPGIP1-OV rice lines at 24 hpi (Fig. 6). More importantly, the RS105-inoculated plants showed two-fold higher levels of JA in OsPGIP1 OV rice lines than in ZH11 (Fig. 6). In general, the OsPGIP1 OV rice lines accumulate more JA to enhance the resistance to Xoc.

Increased accumulation of jasmonic acid in OsPGIP1-overexpressing compared with ZH11 after inoculation with Xoc. The SA and JA contents were measured in the ZH11 and OsPGIP1-overexpressing lines OV-12 and OV-24 without inoculation and 24 h postinoculation with RS105. The letters above the bars represent the significant differences at a value of P ≤ 0.05 (LSD test)

Discussion

PGIPs have clearly been shown to protect plants by enhancing their resistance to fungi; however, there are few examples of PGIPs enhancing plant resistance to bacterial pathogens (Kalunke et al. 2015; Feng et al. 2016). Rice has seven OsPGIPs genes, and they have been shown to respond to various hormones and fungi (Lu et al. 2012). Previously, the overexpression of OsPGIP1 was shown to enhance the resistance of rice to R. solani (Wang et al. 2015a, b; Chen et al. 2016). Constitutive heterogeneous expression of OsPGIP2 enhanced the resistance of B. napus to S. sclerotiorum (Wang et al. 2018). In the present study, we identified that the overexpression of OsPGIP1 enhanced the resistance of rice, while in contrast, the RNAi rice lines showed decreased resistance to Xoc strain RS105 in the susceptible variety ZH11 (Fig. 2). Additionally, repressing OsPGIP1 expression attenuated resistance to RS105 in the moderately resistant variety Acc8558 (Additional file 10: Figure S4). We concluded that OsPGIP1 contributes to BLS resistance. In addition to OsPGIP4, which is located in the closely linked region of OsPGIP1 on chromosome 5 (Feng et al. 2016), we supplied OsPGIP1 as an additional example of a PGIP that combats bacterial pathogens in rice.

The interaction between PGIPs and PG plays crucial roles in resistance to pathogens. PvPGIP2 from P. vulgaris can inhibit the activity of PGs from Aspergillus niger, Fusarium moniliforme and F. phyllophilum (Leckie et al. 1999; Benedetti et al. 2013), and the crystal structure of chemically cross-linked PvPGIP2-FpPG reveals the interaction of PvPGIP2 and FpPG (Benedetti et al. 2011). Ectopic expression of PvPGIP2-FpPG chimera elicited immune responses in Arabidopsis that increased resistance to fungal and bacterial phytopathogens (Benedetti et al. 2015). However, wheat expressing PvPGIP2 shows no resistance to ergot disease because it loses the ability to inhibit PG activity in Claviceps purpurea (Volpi et al. 2013). Thus, PGIP-mediated defense responses require PGIP-PG complex formation. Among the seven PGIPs in rice, the recombinant proteins of OsFOR1 and OsPGIP1 inhibited the activity of PG from A. niger and R. solani, respectively (Jang et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2015b; Chen et al. 2016). Only OsPGIP2 was identified to interact with both SsPG3 and SsPG6 from S. sclerotiorum (Wang et al. 2018). Here, we confirmed that the PG gene contributed to the virulence of RS105. Compared with RS105, RS105Δpg had attenuated virulence in both the susceptible rice variety ZH11 and the moderately resistant variety Acc8558 (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, there was no significant difference in the disease phenotype caused by RS105 and RS105Δpg in the OsPGIP1 OV rice (Fig. 4). The results indicate that PG-mediated virulence deficiency was genetically complemented by overexpressing OsPGIP1. However, based on yeast two-hybridization (Additional file 12: Figure S6), no obvious interaction was found between PG and OsPGIP1, suggesting a different resistance mechanism of OsPGIP1 for the bacterial pathogen Xoc and the fungal pathogen R. solani.

Three other observations also supported the above difference. First, the DR genes were characterized as having upregulated expression upon pathogen inoculation (Kou and Wang 2010). Lu et al. (2012) investigated the expression pattern of OsPGIP1, which slowly increased before 12 hpi, rapidly increased from 12 to 60 hpi, and then decreased slowly from 60 to 96 hpi upon inoculation with R. solani WH-1. In the same ZH11 rice variety, the expression of OsPGIP1 rapidly increased from 0 to 24 hpi and then decreased upon inoculation with Xoc RS105 (Fig. 1a). Moreover, the activated level of OsPGIP1 differed between WH-1 and RS105, with approximately 350-fold and 17-fold peaks in their relative transcript levels, respectively. The different expression patterns implied that they have diversified functions in the resistance to pathogens. Second, PGase activity has been identified from the extraction of PG from R. solani (Chen et al. 2016). However, in addition to there being no interaction between XocPG and OsPGIP1, whether the prokaryotic expression of XocPG or crude protein extracted from RS105 and RS105Δpg was used, we did not detect clear PGase activity with agar diffusion assays (data not shown). Third, we found that OsPGIP1 OV lines primed the accumulation of a higher level of JA but not SA upon inoculation with Xoc RS105 (Fig. 6). Although we have not quantified the content of JA and SA upon inoculation with R. solani, Onda et al. (2018) described that SA treatment enhanced the resistance while JA treatment enhanced the susceptibility of rice to R. solani. Combining the findings that OsPGIP1 OV lines are still resistant to RS105Δpg (Fig. 4), we believe that OsPGIP1-mediated resistance has another unclear mechanism in addition to responding to XocPG.

To understand the mechanism by which OsPGIP1 mediates resistance to Xoc, we performed RNA-seq of OsPGIP1 OV rice. Without RS105 inoculation, the OsPGIP1 OV rice showed few gene alterations compared with ZH11, and no defense-related genes were identified. This is consistent with the results of the analysis of the JA and SA contents, which showed no significant changes between OsPGIP1 OV and ZH11 without inoculation (Fig. 6). A large number of genes were differentially expressed in both OsPGIP1 OV and ZH11 during inoculation (Additional file 13: Figure S7). Among them, two categories, PR genes and cell wall-related genes, were enriched among the common and OsPGIP1 OV-specific DEGs (Fig. 5). Several CHITs, JIOsPR10 (Os03g0300400) and RSOsPR10 (Os12g0555000), were differentially expressed in OsPGIP1 OV lines at 24 hpi with RS105 inoculation (Fig. 5). In addition to PR genes, the cell wall defense-associated genes and several MYB transcription factors were highly expressed or characteristically induced in OsPGIP1 OV rice (Fig. 5 and Additional file 14: Figure S8). The plant cell wall provides a native barrier to block the incursion of different pathogens, and its structure is complex with cellulose, callose, pectins, hemicelluloses, lignin and polysaccharides. Cellulose synthases (CESAs), glucan synthase-like (GSLs) enzymes, and xyloglucan endo-transglycosylases/hydrolases (XTHs) induced expression and participated in cell wall reestablishment (Lampugnani et al. 2018; Bacete et al. 2018). In our study, we found that the cell wall-establishing genes, such as CESA1, CESA4, CESA5, CESA7 and CSLA3, and lignin synthesis genes, including PAL1, PAL3, PAL6, PAL7 and CAD, were upregulated in OsPGIP1 OV rice after inoculation with RS105 (Additional file 5: Table S4 and Additional file 6: Table S5). The results indicated that CESA4 and CESA7 are important cellulose synthase genes for controlling cell wall formation (Tanaka et al. 2003; Zhang et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2016). MYB transcription factors play important roles in regulating cell wall biosynthesis in plants. For instance, Arabidopsis MYB46 directly targets the promoters of CESA4, CESA7 and CESA8 to induce the expression of three cellulose synthase genes that regulate secondary cell wall formation (Kim et al. 2013). The heterogeneous expression of the PdMYB10/128 R2R3-MYB pair in Populus increased the fiber cell wall thickness in Arabidopsis (Chai et al. 2014). The expression of EjMYB1 promotes the expression of EjPAL1, Ej4CLs and EjCADs to increase lignin biosynthesis under cold stress in Eriobotrya japonica (Xu et al. 2014). Several rice MYBs are involved in regulating cell wall biosynthesis. The OsMYB103L gene plays a role in leaf rolling and directly binds the promoters of CESA4, CESA7, and CESA9 to regulate gene expression and promote cell wall formation (Yang et al. 2014; Ye et al. 2015). OsMYB61 directly regulates CESA gene expression to participate in cell wall construction (Huang et al. 2015). Here, we identified three upregulated MYB TFs in common DEGs of OsPGIP1 OV rice and ZH11 after inoculation with RS105, including the MYB-like (Os12g0564100), MYB58/63 (Os04g0594100) and Jamyb genes (Fig. 5c). All three MYB TFs were more strongly induced in OsPGIP1 OV rice, which coincided with the expression of cell wall-associated genes (Fig. 5). Among them, MYB58/63 has been shown to be a positive regulator of OsCESA7 gene expression (Noda et al. 2015). It is possible that OsPGIP1-mediated resistance may protect rice against Xoc through cell wall reestablishment in addition to inducing PR gene expression.

Overall, we identified that the overexpression of OsPGIP1 could enhance resistance to BLS in addition to SB (Wang et al. 2015a, b; Chen et al. 2016). Currently, SB is one of the most severe diseases in rice that causes the highest prevalence of infection each year. BLS is becoming the major epidemic bacterial disease, spreading rapidly and widely in southern and central China. Both rice BLS and SB resistance are mainly controlled by quantitative trait loci (Xie et al. 2014; Manosalva et al. 2009), increasing the applied range of OsPGIP1 in disease-resistance breeding. It was previously shown that there is often a resistance cost upon the overexpression of DR genes in addition to enhanced disease resistance.For instance, OsHSP18.0-CI-overexpressing rice exhibited lower plant height and smaller panicles than wild-type ZH11 rice (Ju et al. 2017). However, overexpressing OsPGIP1 has no obvious harmful effects on development and agricultural traits in Xudao3 (Chen et al. 2016). Here, compared to ZH11, two OsPGIP1 OV lines in the ZH11 background also had no effect on yield traits, including tiller number and 1000 seed-grain weight (Additional file 15: Figure S9). Consistent with the lack of significant resistance cost, the SA and JA contents (Fig. 6) and the expression level of PR genes (Fig. 5) showed no significant changes between the OsPGIP1 OV lines and ZH11 without pathogen challenge. Therefore, we conclude that OsPGIP1 is an ideal candidate to aid in the development of resistant rice.

Conclusions

Our study revealed that PG is a virulence factor in Xoc. OsPGIP1 is an ideal DR gene that contributes to BLS resistance in addition to resistance to SB in rice. We also revealed that the OsPGIP1-mediated resistance is induced by XocPG and other Xoc pathogenicity factors. It is primed by the activated expression of PR genes, the cell wall defense-associated genes and their regulators, and an accumulation of JA.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data sets supporting the results of this article are included within the article and its additional files. The RNA-seq data supporting the results of this article are available in the NCBI’s SRA with the accession number PRJNA517024 (http://trace.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/sra). The accession numbers of related genes in this research are listed in the Additional file 2: Table S1.These genes can be searched out in NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and Rice Genome Annotation Project (http://www.rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/).

Abbreviations

- BLS:

-

Bacterial leaf streak

- CWDEs:

-

Cell wall-degrading enzymes

- DAMP:

-

Damage-associated molecular pattern

- DEG:

-

Differentially expressed gene

- dpi:

-

Days post inoculation

- DR:

-

Defense-related

- hpi:

-

Hours postinoculation

- OGs:

-

Oligogalacturonides

- OV:

-

Overexpressing

- PG:

-

Polygalacturonase

- PGIP:

-

Polygalacturonase-inhibiting protein

- PR:

-

Pathogenesis related

- SB:

-

Sheath blight

- WAK1:

-

Wall-associated kinase 1

- WT:

-

wild-type

- Xoc :

-

Xanthomons oryzae pv. oryzicola

References

Agüero CB, Uratsu SL, Greve C, Powell AT, Labavitch JM, Meredith CP, Dandekar AM (2005) Evaluation of tolerance to Pierce’s disease and Botrytis in transgenic plants of Vitis vinifera L. expressing the pear PGIP gene. Mol Plant Pathol 6:43–51

Bacete L, Mélida H, Miedes E, Molina A (2018) Plant cell wall-mediated immunity: cell wall changes trigger disease resistance responses. Plant J 93:614–636

Bellincampi D, Cervone F, Lionetti V (2014) Plant cell wall dynamics and wall-related susceptibility in plant-pathogen interactions. Front Plant Sci 5:228

Benedetti M, Andreani F, Leggio C, Galantini L, Di Matteo A, Pavel NV, De Lorenzo G, Cervone F, Federici L, Sicilia F (2013) A single amino-acid substitution allows endo-polygalacturonase of Fusarium verticillioides to acquire recognition by PGIP2 from Phaseolus vulgaris. PLoS One 8:e80610

Benedetti M, Leggio C, Federici L, De Lorenzo G, Viorel Pavel N, Cervone F (2011) Structural resolution of the complex between a fungal polygalacturonase and a plant polygalacturonase-inhibiting protein by small-angel X-ray scattering. Plant Physiol 157:599–607

Benedetti M, Pontiggiaa D, Raggia S, Cheng Z, Scalonia F, Ferraria S, Ausubel FM, Cervonea F, De Lorenzoa G (2015) Plant immunity triggered by engineered in vivo release of oligogalacturonides, damage-associated molecular patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:5533–5538

Boller T, He SY (2009) Innate immunity in plants: an arms race between pattern recognition receptors in plants and effectors in microbial pathogens. Science 324:742–744

Borras-Hidalgo O, Caprari C, Hernandez-Estevez I, Lorenzo GD, Cervone F (2012) A gene for plant protection: expression of a bean polygalacturonase inhibitor in tobacco confers a strong resistance against Rhizoctonia solani and two oomycetes. Front Plant Sci 3:268

Brutus A, Sicilia F, Macone A, Cervone F, De Lorenzo G (2010) A domain swap approach reveals a role of the plant wall-associated kinase 1 (WAK1) as a receptor of oligogalacturonides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:9452–9457

Cao W, Chu R, Zhang Y, Luo J, Su Y, Liu J, Zhang H, Wang J, Bao Y (2015) OsJAMyb, a R2R3-type MYB transcription factor enhanced blast resistance in transgenic rice. Physiol Mol. Plant Pathol 92:154–160

Chai G, Wang Z, Tang X, Yu L, Qi G, Wang D, Yan X, Kong Y, Zhou G (2014) R2R3-MYB gene pairs in Populus: evolution and contribution to secondary wall formation and flowering time. J Exp Bot 65:4255–4269

Chen C, Zheng W, Huang X, Zhang D, Lin X (2006) Major QTL conferring resistance to rice bacterial leaf streak. Agr Sci China 5(3):216–220

Chen X, Chen Y, Zhang L, Xu B, Zhang J, Chen Z, Tong Y, Zuo S, Xu J (2016) Overexpression of OsPGIP1 enhances rice resistance to sheath blight. Plant Dis 100:388–395

Chotechung S, Somta P, Chen J, Yimram T, Chen X, Srinives P (2016) A gene encoding a polygalacturonase-inhibiting protein (PGIP) is a candidate gene for bruchid (Coleoptera: bruchidae) resistance in mungbean (Vigna radiata). Theor Appl Genet 129:1673–1683

Davidsson P, Broberg M, Kariola T, Sipari N, Pirhonen M, Palva ET (2017) Short oligogalacturonides induce pathogen resistance-associated gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol 17:19

Di Matteo A, Federici L, Mattei B, Salvi G, Johnson KA, Savino C, De Lorenzo G, Tsenoglou D, Cervone F (2003) The crystal structure of polygalacturonase-inhibiting protein (PGIP), a leucine-rich repeat protein involved in plant defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:10124–10128

Feng C, Zhang X, Wu T, Yuan B, Ding X, Yao F, Chu Z (2016) The polygalacturonase-inhibiting protein 4 (OsPGIP4), a potential component of the qBlsr5a locus, confers resistance to bacterial leaf streak in rice. Planta 243:1297–1308

Fu J, Liu H, Li Y, Yu H, Li X, Xiao J, Wang S (2011) Manipulating broad-spectrum disease resistance by suppressing pathogen-induced auxin accumulation in rice. Plant Physiol 155:589–602

Gallego-Giraldo L, Pose S, Pattathil S, Peralta AG, Hahn MG, Ayre BG, Sunuwar J, Hernandez J, Patel M, Shah J, Rao X, Knox JP, Dixon RA (2018) Elicitors and defense gene induction in plants with altered lignin compositions. New Phytol 219:1235–1251

Galletti R, Denoux C, Gambetta S, Dewdney J, Ausubel FM, De Lorenzo G, Ferrari S (2008) The AtrbohD-mediated oxidative burst elicited by oligogalacturonides in Arabidopsis is dispensable for the activation of defense responses effective against Botrytis cinerea. Plant Physiol 148:1695–1706

Guo L, Guo C, Li M, Wang W, Luo C, Zhang Y, Chen L (2014) Suppression of expression of the putative receptor-like kinase gene NRRB enhances resistance to bacterial leaf streak in rice. Mol Biol Rep 41:2177–2187

Hashimoto M, Kisseleva L, Sawa S, Furukawa T, Komatsu S, Koshiba T (2004) A novel rice PR10 protein, RSOsPR10, specifically induced in roots by biotic and abiotic stresses, possibly via the jasmonic acid signaling pathway. Plant Cell Physiol 45:550–559

Huang D, Wang S, Zhang B, Shang-Guan K, Shi Y, Zhang D, Liu X, Wu K, Xu Z, Fu X, Zhou Y (2015) A gibberellin-mediated DELLA-NAC signaling cascade regulates cellulose synthesis in rice. Plant Cell 27:1681–1696

Hui S, Shi Y, Tian J, Wang L, Li Y, Wang S, Yuan M (2019) TALE-carrying bacterial pathogens trap host nuclear import receptors for facilitation of infection of rice. Mol Plant Pathol 20:519–532

Hutin M, Césari S, Chalvon V, Michel C, Tran TT, Boch J, Koebnik R, Szurek B, Kroj T (2016) Ectopic activation of the rice NLR heteropair RGA4/RGA5 confers resistance to bacterial blight and bacterial leaf streak diseases. Plant J 88:43–55

Hwang BH, Bae H, Lim HS, Kim KB, Kim SJ, Im MH, Park BS, Kim DS, Kim J (2010) Overexpression of polygalacturonase-inhibiting protein 2 (PGIP2) of Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp pekinensis) increased resistance to the bacterial pathogen Pectobacterium carotovorum ssp carotovorum. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult 103:293–305

Jang S, Lee B, Kim C, Kim SJ, Yim J, Han JJ, Lee S, Kim SR, An G (2003) The OsFOR1 gene encodes a polygalacturonase-inhibiting protein (PGIP) that regulates floral organ number in rice. Plant Mol Biol 53:357–372

Jones DGJ, Dangl JL (2006) The plant immune system. Nature 444:323–329

Ju Y, Tian H, Zhang R, Zuo L, Jin G, Xu Q, Ding X, Li X, Chu Z (2017) Overexpression of OsHSP18.0-CI enhances resistance to bacterial leaf streak in rice. Rice 10:12

Jwa NS, Kumar Agrawal G, Rakwal R, Park CH, Prasad Agrawal V (2001) Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel Jasmonate inducible pathogenesis-related class 10 protein gene, JIOsPR10, from rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedling leaves. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 286:973–983

Kalunke RM, Tundo S, Benedetti M, Cervone F, De Lorenzo G, D’Ovidio R (2015) An undate on polygalacturonase-inhibiting protein (PGIP), a leucine-rich repeat protein that protects crop plants against pathogens. Front Plant Sci 6:146

Kim WC, Ko JH, Kim JY, Kim J, Bae HJ, Han KH (2013) MYB46 directly regulates the gene expression of secondary wall-associated cellulose synthases in Arabidopsis. Plant J 73:26–36

Kou Y, Wang S (2010) Broad-spectrum and durability: understanding of quantitative disease resistance. Curr Opin Plant Biol 13:181–185

Lampugnani ER, Khan GA, Somssich M, Persson S (2018) Building a plant cell wall at a glance. J Cell Sci 131:jcs207373

Leckie F, Mattei B, Capodicasa C, Hemmings A, Nuss L, Aracri B, De Lorenzo G, Cervone F (1999) The specificity of polygalacturonaseinhibiting protein (PGIP): a single amino acid substitution in the solvent exposed beta-strand/beta-turn region of the leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) confers a new recognition capability. EMBO J 18:2352–2363

Le Gall H, Philippe F, Domon JM, Gillet F, Pelloux J, Rayon C (2015) Cell wall metabolism in response to abiotic stress. Plants 4:112–166

Li B, Meng X, Shan L, He P (2016) Transcriptional regulation of pattern-triggered immunity in plants. Cell Host Microbe 19:641–650

Li N, Kong L, Zhou W, Zhang X, Wei S, Ding X, Chu Z (2013) Overexpression of Os2H16 enhances resistance to phytopathogens and tolerance to drought stress in rice. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult 115:429–441

Liu N, Zhang X, Sun Y, Wang P, Li X, Pei Y, Li F, Hou Y (2017) Molecular evidence for the involvement of a polygalacturonase-inhibiting protein, GhPGIP1, in enhanced resistance to Verticillium and Fusarium wilts in cotton. Sci Rep 7:39840

Loper JE, Lindow SE (1987) Lack of evidence for the in situ fluorescent pigment production by Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae on bean leaf surfaces. Phytopathology 77:1449–1454

Lu L, Zhou F, Zhou Y, Fan X, Ye S, Wang L, Chen H, Lin Y (2012) Expression profile analysis of the polygalacturonase-inhibiting protein genes in rice and their responses to phytohormones and fungal infection. Plant Cell Rep 31:1173–1187

Ma H, Chen J, Zhang Z, Ma L, Yang Z, Zhang Q, Li X, Xiao J, Wang S (2017) MAPK kinase 10.2 promotes disease resistance and drought tolerance by activating different MAPKs in rice. Plant J 92:557–570

Malinovsky FG, Fangel JU, Willats WGT (2014) The role of the cell wall in plant immunity. Front Plant Sci 5:178

Manosalva PM, Davidson RM, Liu B, Zhu X, Hulbert SH, Leung H, Leach JE (2009) A germin-like protein gene family functions as a complex quantitative trait locus conferring broad-spectrum disease resistance in rice. Plant Physiol 149:286–296

Niño-Liu DO, Ronald PC, Bogdanove AJ (2006) Xanthomonas oryzae pathovars: model pathogens of a model crop. Mol Plant Pathol 7:303–324

Noda S, Koshiba T, Hattori T, Yamaguchi M, Suzuki S, Umezawa T (2015) The expression of a rice secondary wall-specific cellulose synthase gene, OsCesA7, is directly regulated by a rice transcription factor, OsMYB58/63. Planta 242:589–600

Oeser B, Heidrich PM, Muller U, Tudzynski P, Tenberge K (2002) Polygalacturonase is a pathogenicity factor in the Claviceps purpurea/rye interaction. Fungal Genet Biol 36:176–186

Onda Y, Mochida K, Noutoshi Y (2018) Salicylic acid-dependent immunity contributes to resistance against Rhizoctonia solani, a necrotrophic fungal agent of sheath blight, in rice and Brachypodium distachyon. New Phytol 217:771–783

Rasul S, Dubreuil-Maurizi C, Lamotte O, Koen E, Poinssot B, Alcaraz G, Wendehenne D, Jeandroz S (2012) Nitric oxide productionmediates oligogalacturonide-triggered immunity and resistance to Botrytis cinerea in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Environ 35:1483–1499

Schacht T, Unger C, Pich A, Wydra K (2011) Endo- and exopolygalacturonases of Ralstonia solanacearum are inhibited by polygalacturonase-inhibiting protein (PGIP) activity in tomato stem extracts. Plant Physiol Biochem 49:377–387

Schäfer A, Tauch A, Jäger W, Kalinowski J, Thierbach G, Pühler A (1994) Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145:69–73

Shah SJ, Anjam MS, Mendy B, Anwer MA, Habash SS, Lozano-Torres JL, Grundler FMW, Siddique S (2017) Damage-associated responses of the host contribute to defence against cyst nematodes but not root-knot nematodes. J Exp Bot 68:5949–5960

Shen X, Yuan B, Liu H, Li X, Xu C, Wang S (2010) Opposite functions of a rice mitogen-activated protein kinase during the process of resistance against Xanthomonas oryzae. Plant J 64:86–99

Sicilia F, Fernandez-Recio J, Caprari C, De Lorenzo G, Tsernoglou D, Cervone F, Federici L (2005) The polygalacturonase-inhibiting protein PGIP2 of Phaseolus vulgaris has evolved a mixed mode of inhibition of endopolygalacturonase PG1 of Botrytis cinerea. Plant Physiol 139:1380–1388

Spoel SH, Dong XN (2008) Making sense of hormone crosstalk during plant immune responses. Cell Host Microbe 3:348–351

Sridevi G, Parameswari C, Sabapathi N, Raghupathy V, Veluthambi K (2008) Combined expression of chitinase and β-1,3-glucanase genes in indica rice (Oryza sativa L.) enhances resistance against Rhizoctonia solani. Plant Sci 175:283–290

Tanaka K, Murata K, Yamazaki M, Onosato K, Miyao A, Hirochika H (2003) Three distinct rice cellulose synthase catalytic subunit genes required for cellulose synthesis in the secondary wall. Plant Physiol 133:73–83

Tao Z, Liu H, Qiu D, Zhou Y, Li X, Xu C, Wang S (2009) A pair of allelic WRKY genes play opposite roles in rice-bacteria interactions. Plant Physiol 151:936–948

ten Have A, Mulder W, Visser J, van Kan JA (1998) The endopolygalacturonase gene Bcpg1 is required for full virulence of Botrytis cinerea. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact 11:1009–1016

Tonnessen BW, Manosalva P, Lang JM, Baraoidan M, Bordeos A, Mauleon R, Oard J, Hulbert S, Leung H, Leach JE (2015) Rice phenylalanine ammonia-lyase gene OsPAL4 is associated with broad spectrum disease resistance. Plant Mol Biol 87:273–286

Triplett LR, Cohen SP, Heffelfinger C, Schmidt C, Huerta AI, Tekete C, Verdier V, Bogdanove AJ, Leach JE (2016) A resistance locus in the American heirloom rice variety Carolina Gold Select is triggered by TAL effectors with diverse predicted targets and is effective against African strains of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola. Plant J 87:472–483

Volpi C, Raiola A, Janni M, Gordon A, O’Sullivan DM, Favaron F, D’Ovidio R (2013) Claviceps purpurea expressing polygalacturonases escaping PGIP inhibition fully infects PvPGIP2 wheat transgenic plants but its infection is delayed in wheat transgenic plants with increased level of pectin methyl esterification. Plant Physiol Biochem 73:294–301

Wang A, Wei X, Rong W, Dang L, Du LP, Qi L, Xu HJ, Shao Y, Zhang Z (2015a) GmPGIP3 enhanced resistance to both take-all and common root rot diseases in transgenic wheat. Funct Integr Genomics 15:375–381

Wang D, Qin Y, Fang J, Yuan S, Peng L, Zhao J, Li X (2016) A missense mutation in the zinc finger domain of OsCESA7 deleteriously affects cellulose biosynthesis and plant growth in rice. PLoS One 11:e0153993

Wang R, Lu LX, Pan XB, Hu ZL, Ling F, Yan Y, Liu YM, Lin YJ (2015b) Functional analysis of OsPGIP1 in rice sheath blight resistance. Plant Mol Biol 87:181–191

Wang Z, Wan L, Xin Q, Chen Y, Zhang X, Dong F, Hong D, Yang G (2018) Overexpression of OsPGIP2 confers Sclerotinia sclerotiorum resistance in Brassica napus through increased activation of defense mechanisms. J Exp Bot 69:3141–3155

Xie X, Chen Z, Cao J, Guan H, Lin D, Li C, Lan T, Duan Y, Mao D, Wu W (2014) Toward the positional cloning of qBlsr5a, a QTL underlying resistance to bacterial leaf streak, using overlapping sub-CSSLs in rice. PLoS One 9:e95751

Xu Q, Truong TT, Barrero JM, Jacobsen JV, Hocart CH, Gubler F (2016) A role for jasmonates in the release of dormancy by cold stratification in wheat. J Exp Bot 67:3497–3508

Xu Q, Yin XR, Zeng JK, Ge H, Song M, Xu CJ, Li X, Ferguson IB, Chen KS (2014) Activator- and repressor-type MYB transcription factors are involved in chilling injury induced flesh lignification in loquat via their interactions with the phenylpropanoid pathway. J Exp Bot 65:4349–4359

Yang C, Li D, Liu X, Ji C, Hao L, Zhao X, Li X, Chen C, Cheng Z, Zhu L (2014) OsMYB103L, an R2R3-MYB transcription factor, influences leaf rolling and mechanical strength in rice (Oryza sativa L.). BMC Plant Biol 14:158

Yang W, Zhang B, Qi G, Shang L, Liu H, Ding X, Chu Z (2019) Identification of the phytosulfokine receptor 1 (OsPSKR1) confers resistance to bacterial leaf streak in rice. Planta 250:1603–1612

Ye Y, Liu B, Zhao M, Wu K, Cheng W, Chen X, Liu Q, Liu Z, Fu X, Wu Y (2015) CEF1/OsMYB103L is involved in GA-mediated regulation of secondary wall biosynthesis in rice. Plant Mol Biol 89:385–401

Zhang B, Deng L, Qian Q, Xiong G, Zeng D, Li R, Guo L, Li J, Zhou Y (2009) A missense mutation in the transmembrane domain of CESA4 affects protein abundance in the plasma membrane and results in abnormal cell wall biosynthesis in rice. Plant Mol Biol 71:509–524

Zhang B, Liu H, Ding X, Qiu J, Zhang M, Chu Z (2018) Arabidopsis thaliana ACS8 plays a crucial role in the early biosynthesis of ethylene elicited by Cu2+ ions. J Cell Sci 131:jcs202424

Zou L, Zeng Q, Lin H, Gyaneshwar P, Chen G, Yang C (2012) SlyA regulates T3SS genes in parallel with the T3SS master regulator HrpL in Dickeya ddantii 3937. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:2888–2895

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Professor Wenxian Sun and Professor Gongyou Chen for providing pVSP61 and pK18mobsacB vector respectively.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Program of Transgenic Variety Development of China (2018ZX08010-05B, 2016ZX08001–002), the Natural Science Fund for Outstanding Young Scholars of Shandong Province (JQ201807), and the Shandong Modern Agricultural Technology & Industry system (SDAIT-17-06).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZC and XD designed the experiments. TW, CP, BL and WW performed the experiments. TW and ZC analyzed data. LK and FL help to field management. FCL help to test the enzymatic activity. TW and ZC wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Text S1.

Comparison of the OsPGIP1sequence containing CDS and promoter between ZH11 and Acc8558.

Additional file 2: Table S1.

The primers used in this study.

Additional file 3: Table S2.

The putative cis-elements of the OsPGIP1 promoters in ZH11 and Acc8558.

Additional file 4: Table S3.

RNA-seq analysis of the common DEGs in ZH11-RS vs. ZH11 and OV-24-RS vs. OV-24.

Additional file 5: Table S4.

RNA-seq analysis of the unique DEGs of OV-24-RS vs. OV-24.

Additional file 6: Table S5.

RNA-seq analysis of the unique DEGs of ZH11-RS vs. ZH11.

Additional file 7: Figure S1.

Expression patterns of rice OsPGIPs in response to RS105 in Acc8558 rice. The expression of OsPGIPs in BLS moderately resistant rice variety Acc8558 at 6, 24, 48, and 96 h postinoculation was related to leaves without inoculation (0 h). The ACTIN was used as an internal control. Error bars represent the standard deviations for three replicates.

Additional file 8: Figure S2.

Resistance of the OsPGIP1-overexpressing plants to the Xoc strain RS105 in the T0 and T1 generation. (a) Lesion length analysis of OsPGIP1-overexpressing transgenic rice in the T0 generation in a ZH11 background 14 days after inoculation with RS105. (b) Cosegregation of the lesion length with PCR positive selection in the T1 generation for the OV-12, OV-24 and OV-29 lines. The average lesion length was calculated with more than ten inoculation sites for each individual plant. The gel image indicates the plants carrying pU1301::OsPGIP1 by PCR amplification with the primer pair of Hpt-F/R. Bars represent the means ± SD. Significant differences were determined by t test: *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, respectively.

Additional file 9: Figure S3.

Three OsPGIP1-silenced lines enhanced the susceptibility of ZH11 to bacterial leaf streak in the T1 generation. Cosegregation of the lesion length with PCR positive selection for three OsPGIP1-silenced rice lines, RNAi-7, RNAi-10 and RNAi-11, in the ZH11 background. The average lesion length was measured with over ten inoculation sites for each individual plant. The gel image indicates the plants carrying ds1301::OsPGIP1 by PCR amplification with the primer pair Hpt-F/R. Bars represent the means ± SD. Significant differences were determined by t test: *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, respectively.

Additional file 10: Figure S4.

Repressing the OsPGIP1 expression enhanced the susceptibility of Acc8558 to BLS in the T1 generation. Cosegregation of the lesion length with PCR positive selection for three OsPGIP1 RNAi lines, RNAi-1, RNAi-4 and RNAi-7 in moderately resistant rice variety Acc8558 background. The average lesion length was calculated with over ten inoculation sites for each individual plant. The gel image indicates the plants carrying ds1301::OsPGIP1 by PCR amplification with the primer pair Hpt-F/R. Bars represent the means ± SD. Significant differences were determined by t test: *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, respectively.

Additional file 11: Figure S5.

Bacterial growth curve of RS105 in OsPGIP1-overexpressing and OsPGIP1-silenced rice lines. The bacterial populations of RS105 in the wild-type ZH11 rice, OsPGIP1-overexpressing rice line OV-24 and OsPGIP1-silenced rice line RNAi-10 were detected at 1, 4 and 7 days postinoculation. Significant differences were determined by t test: *P < 0.05.

Additional file 12: Figure S6.

XocPG fails to interact with OsPGIP1 or OsPGIP4 by yeast two hybridization. The yeast transformants grew on double-dropout minimal base (SD/−leucine-tryptophan) and the interaction in yeast was tested by quadruple-dropout minimal base (SD/−leu-trp-ade-his) and aureobasidin A. The pGBKT7–53 and pGADT7-T yeast transformation was used as the positive control.

Additional file 13: Figure S7.

GO analysis of the DEGs in OsPGIP1-overexpressing rice. (a) The functional analysis of genes that were upregulated and downregulated in OV-24 compared with ZH11 without RS105 inoculation. (b) The Venn diagram of DEGs in OV-24 compared with ZH11 (ZH11vs OV-24), ZH11 inoculated with RS105 compared to ZH11 (ZH11 vs ZH11-RS), and OV-24 inoculated with RS105 compared to OV-24 (OV-24 vs OV-24-RS).

Additional file 14: Figure S8.

GO analysis of DEGs uniquely regulated in the OsPGIP1-overexpressing rice. The GO analysis of DEGs that specifically changed in OsPGIP1 OV-24-RS included cellular component, molecular function and biological process categories.

Additional file 15: Figure S9.

The yield traits of OsPGIP1-overexpressing rice showed no significant changes. (a) The tiller number of the two OsPGIP1 OV lines (OV-12 and OV-24) and ZH11 were counted in at least 30 individual plants after the full growth period. (b) The OV-12, OV-24 and ZH11 rice seeds were harvested after the complete growth period and after removing moisture with a dryer. Then 1000 seed grains were weighed for the rice, and the experiment was repeated 10 times.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, T., Peng, C., Li, B. et al. OsPGIP1-Mediated Resistance to Bacterial Leaf Streak in Rice is Beyond Responsive to the Polygalacturonase of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola. Rice 12, 90 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-019-0352-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-019-0352-4