Abstract

Background

Pepper, Capsicum annuum L., Solanaceae, is a major staple economically important vegetable crop worldwide. Limited functional genomics resources and whole genome association studies could be substantially improved through the application of molecular approach for the characterization of gene content and identification of molecular markers. The massive parallel pyrosequencing of two pepper varieties, the highly pungent, Saengryeg 211, and the non-pungent, Saengryeg 213, including de novo transcriptome assembly, functional annotation, and in silico discovery of potential molecular markers is described. We performed 454 GS-FLX Titanium sequencing of polyA-selected and normalized cDNA libraries generated from a single pool of transcripts obtained from mature fruits of two pepper varieties.

Results

A single 454 pyrosequencing run generated 361,671 and 274,269 reads totaling 164.49 and 124.60 Mb of sequence data (average read length of 454 nucleotides), which assembled into 23,821 and 17,813 isotigs and 18,147 and 15,129 singletons for both varieties, respectively. These reads were organized into 20,352 and 15,781 'isogroups’ for both varieties. Assembled sequences were functionally annotated based on homology to genes in multiple public databases and assigned with Gene Ontology (GO) terms. Sequence variants analyses identified a total of 3,766 and 2,431 potential (Simple Sequence Repeat) SSR motifs for microsatellite analysis for both varieties, where trinucleotide was the most common repeat unit (84%), followed by di (9.9%), hexa (4.1%) and pentanucleotide repeats (2.1%). GAA repeat (8.6%) was the most frequent repeat motif, followed by TGG (7.2%), TTC (6.5%), and CAG (6.2%).

Conclusions

High-throughput transcriptome assembly, annotation and large scale of SSR marker discovery has been achieved using next generation sequencing (NGS) of two pepper varieties. These valuable informations for functional genomics resource shall help to further improve the pepper breeding efforts with respect to genetic linkage maps, QTL mapping and marker-assisted trait selection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pepper (Capsicum spp., Solanaceae), is an important vegetable crop mostly used as spice, condiment, medicine, vegetable and a significant source of vitamin A and C (Bosland and Votava 2000), throughout the world. Originated and initially domesticated in the Americas, the genus includes 38 species with 5 (C. annuum, C. chinense, C. frutescens, C. baccatum, and C. pubescens) domesticated ones (Hill et al. 2013), having C. annuum as the most economically important one (Bosland and Votava 2000; Perry et al. 2007). It has been used as a model organism for classical and molecular genetics analyses very similar to the other Solanaceous member tomato. The detailed genetic, mapping, comparative genomics and gene-based association studies facilitate the identification of quantitative traits loci (QTLs) and subsequent identification of genes via map-based cloning strategies to understand the genetic control of various traits (Xu et al. 2003; Jun et al. 2008). These studies are enabled by the genome-wide molecular characterization of the germplasm (Lee et al. 2004; Yi et al. 2006; Kim et al. 2008) and require enough molecular markers for the production of dense linkage and association maps to identify these QTLs. Numerous genetic markers have been identified and mapped in the recent past (Prince et al. 1995; Ben Chaim et al. 2001; Hernandez-Verdugo et al. 2001; Lefebvre et al. 2001; Rao et al. 2003; Paran et al. 2004; Oyama et al. 2006; Kim et al. 2008) and Simple Sequence Repeats (SSRs) and Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) have been found as the most attractive ones for these studies (Lee et al. 2005). SSRs (Microsatellite markers) are important because of their locus-specific codominant and multiallelic nature, significant abundance in the genome, and high rates of transferability across species (Saha et al. 2006; Aggarwal et al. 2007). These have already been widely used in molecular mapping of important genes in many organisms, marker-assisted selection (MAS) in breeding, genetic diversity and distance evaluation, genome-wide association analysis, and comparative genetics (Mian et al. 2008; Cavagnaro et al. 2010; Csencsics et al. 2010; Dutta et al. 2011; Jun et al. 2011). Despite the numerous available markers, the whole genome association studies in pepper are not possible as the marker density is not enough to target candidate genes underlying a QTL region and conduct association mapping for complex traits (Livingstone et al. 1999; Minamiyama et al. 2006; Barchi et al. 2007; Wu et al. 2009; Truong et al. 2010; Kong et al. 2012). These studies require a large number of markers and cost effective genotyping technology, where lack of markers covering the whole genome stands as the major limitation to the development of high throughput genotyping assays. The rapid identification of these markers associated with complex, economically important traits in crops has been hindered by the lack of whole genomic sequence, high-resolution maps and cost-effective platforms for high density genotyping. This eventually restricts the commercial application of these genomic resources for gene discovery and molecular breeding.

Recent advances in next generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have created unprecedented opportunities for generating genomic information in even previously uncharacterized systems (Logacheva et al. 2011; Lu et al. 2011; McDowell et al. 2011; Sloan et al. 2012). The process of whole genome sequencing, rapid identification and annotations of gene sequences (Mizrachi et al. 2010; Garg et al. 2011), novel and alternatively spliced genes (Roberts and Smith 2002) and the determination of the variations in nucleotide sequences provides new platform for gene expression analysis (Ameline-Torregrosa et al. 2006; Kim et al. 2006; Cohen et al. 2010) and identification of regulatory elements, target critical genes and enormous polymorphic molecular markers motifs (Gore et al. 2009; Tangphatsornruang et al. 2009; You et al. 2011; Zalapa et al. 2012; Zhu et al. 2012). With these detailed informations, QTL fine mapping and map-based cloning of economically important genes which require development of high density molecular markers in QTL regions become more achievable in identification of genes for important and complex traits (Ben Chaim et al. 2001; Mian et al. 2008; Lee et al. 2009). The transcriptome assembly of this economically important pepper crop is a major requirement in order to generate high-quality gene based molecular markers that are an important resource for determination of functional genetic variations and could be used in breeding programs. Therefore, aiming the transcriptome assembly and cost effective identification of SSR markers, first transcriptome profiling of two varieties of pepper, C. annuum; the 'highly pungent’ Saengryeg 211 and 'non-pungent’ Saengryeg 213 (Jung et al. 2006) using 454 pyrosequencing technology with emphasis on microsatellite markers discovery has been performed in the present study.

Methods

Plant material and cDNA preparation

Mature fruits from two varieties of pepper C. annuum L., Saengryeg 211 and Saengryeg 213 cultivated in greenhouse were collected and stored at -80°C. 100 mg tissues were used for total RNA extraction via RNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen) based on TRIzol RNA isolation protocol. Quantity and quality of the extracted RNA was determined using a BIOSPEC-NANO spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) and agarose gel electrophoresis. It was purified using the PolyATract mRNA isolation system IV (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and then it was used to synthesize the full-length cDNA using ZAP-cDNA synthesis kit (Stratagene, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Finally, cDNA was fragmented by nebulization using an Agilent 2100 BioAnalyzer (Waldbronn, Germany) for library construction with a mean fragment size of about 600 bp.

Library preparation

For the generation of DNA library to be used for Genome Sequencer FLX titanium (GS-FLX, Roche, Mannheim, GE), approximately, 1 μg of the DNA was used. The cDNA fragments ends were blunted and two short adapters were ligated to both the ends following the standard procedures. The adaptors provided priming sequences for amplification and sequencing of the sample library fragments as well as 'the sequencing keys’, a short sequence of 4 nucleotides. The sequencing key released the unbound strand of each fragment (with 5’ Adaptor A) following repair of any nicks in the double-stranded library. The single stranded template DNA (sstDNA) was quantitated, including a functional quantitation to determine the optimal amount of the library to use as input for emulsion-based clonal amplification.

454 pyrosequencing

Manufacturer’s instructions were followed for high-throughput sequencing of the constructed libraries (GS FLX Titanium General Library Preparation Kit/emPCR kit/sequencing kit, Roche Diagnostics, http://www.roche.com) using approximately 1 μg of the adaptor-ligated cDNA population sheared by nebulization. Single effective copies of template species from the DNA library to be sequenced were hybridized to DNA capture beads and the immobilized library was re-suspended in the amplification solution. The mixture was emulsified and subjected to PCR amplification. The DNA carrying beads were recovered from the emulsion and enriched after amplification. As part of the enrichment process, the second strands of the amplification products were melted away, leaving the amplified ssDNA library bound to the beads. The sequencing primer was then annealed to the immobilized amplified DNA templates. After amplification, the DNA-carrying beads were set into the wells of a PicoTiterPlate device (PTP) so that each well contains single DNA beads only. The loaded PTP was eventually inserted into the sequencer for pyrosequencing and sequencing reagents were sequentially flowed over the plate. All the information from the wells was captured and recorded simultaneously and processed in real time.

Transcriptome assembly and annotation

The transcriptome assembly process is required to account for the co-existence of simultaneously highly related but distinct sequences to represent alternative splice variants of the same as well as different alleles from the same or different loci. The eukaryotic gene expression including the alternative splicing makes this complete process very complicated (Modrek & Lee 2002). GS de novo Assembler employs a network or graph-based approach to describe the connectivity between assembled contigs. Individual reads are split by introducing breaks into the assembly and these are further used to define the alternative connections between contigs. Assembled contigs are organized into 'isogroups’ which represent all contigs from a given genetic locus. Within each isogroup, contigs can be connected in different permutations (termed 'isotigs’), each of which can be loosely thought of as a specific splice variant or allele (Sloan et al. 2012; http://454.com/downloads/my454/documentation/gs-flx-plus/454SeqSys_SWManual-v2.6_PartC_May2011.pdf).

The reads thus generated were trimmed of low quality, low complexity [poly(A)], and the adaptor sequences and singleton trimming was analyzed using the SeqClean ver. 1.0 and Lucy program ver. 2.19. De novo assembly was performed for the delicate mapping of each sequence. Reference ESTs and mRNA data used for comparison between the sequences of two pepper varieties and that of the public transcript were collected from the NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?mode=Info&id=4072&lvl=3&lin=f&keep=1&srchmode=1&unlock). All the isotigs and singletons were identified by the analysis of sequence assembly and the assembled transcript sequences were functionally annotated using blastx algorithm and non-redundant protein database at NCBI by blast software with a cut-off e-value of 1.0E-3. By the automated blastx analysis the GI accessions of best hits were retrieved, and the GO accessions were mapped to GO terms according to molecular function, biological process and cellular component ontologies (http://www.geneontology.org/).

Simple sequence repeat detection

All isotigs and singletons separately from both transcriptome data were used to mine the SSR motifs to obtain the information of molecular markers in both the pepper varieties. All non-redundant trimmed sequences were screened for repeat motifs using the Repeatmasker (http://www.repeatmasker.org/), SSRIT (Simple Sequence Repeat Identification) http://www.gramene.org/db/markers/ssrtool using Perl regular expressions to find perfect SSR within the sequences (Temnykh et al. 2001). Sequences containing at least 6 di nucleotide repeats and 4 tri nucleotide repeats or larger were selected as microsatellite. All motifs having continuous uninterrupted repeats were classified as perfect and those containing more than one class of repeats were classified as compound. Mononucleotide repeats were defined both in terms of base pairs and number of repeats. The resulting output was filtered to exclude duplicate SSRs within the same isogroup because multiple isotigs from the same isogroup can share sequences.

Results

sstDNA Library construction

The sstDNA libraries were constructed through total RNA isolation, mRNA purification, cDNA synthesis, cDNA fragmentation and adaptor ligation based on the standard protocols from commercial kits. cDNA was fragmented for the production of transcripts fragments with the standard length necessary for 454 pyrosequencing.

454 pyrosequencing and sequence assembly

361,671 and 274,269 raw reads with a total length of 164.49 and 124.60 Mb were generated by the 454 GS FLX Sequencer for Saengryeg 211 and Saengryeg 213, respectively (Table 1). These raw sequencing reads were eventually reduced to 351293 (97.13%) and 266703 (97.24%) high quality sequences for both the varieties after filtering of adaptors, and primers. The raw data were deposited in EBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the accession numbers Study_IDs ERP001874 for Saengryeg 211 and ERP001873 for Saengryeg 213, respectively. For Saengryeg 211; 78.17% of the screened reads (282,705) were incorporated into assembled sequences (isotigs), with remaining 5.01% as singletons (18,147). 60,789 reads (16.80% of reads subjected to assembly) were excluded because of being partially assembled (50,330; 13.91%), from repeat regions (111; 0.03%), outliers (5,075; 1.40%), or too short (5,273; 1.45%). The assembly resulted in 23,821 isotigs out of which 18,363 (77.08%) isotigs were assembled by one contig and the average number of contigs per isotigs was 1.4. The isotig N50 length was 1,028 bp, and the number of isogroups was 20,352 (18,317 [90.00%] of these were assembled by one isotig, whereas 18,295 [89.89%] were assembled by one contig, and the mean number of isotigs per isogroup was 1.2). Similarly, in case of Saengryeg 213; 217,905 (79.45%) of the screened reads were incorporated into assembled sequences (isotigs or contigs), with 15,129 (5.51%) singletons remaining. 60,789 reads (16.80% of reads subjected to assembly) were excluded because they were only partially assembled (33,427; 12.18%), from repeat regions (242; 0.08%), outliers (3,699; 1.34%), or too short (3,831; 1.39%). The assembly resulted in 17,813 isotigs out of which 14,556 (81.71%) isotigs were assembled by one contig and the average number of contigs per isotigs was 1.3. The isotig N50 length was 977 bp, and the number of isogroups was 15,781 (14,537 [92.11%] of these were assembled by one isotig, whereas 14,520 [92.01%] were assembled by one contig, and the mean number of isotigs per isogroup was 1.1).

Functional annotations of the transcriptome sequences

Assembled sequences from pooled reads were validated by sequence based alignments against ESTs submitted at NCBI database. Besides, manual assessment of alignment for all transcripts with their blastx hits against protein NR databases at NCBI was also performed.

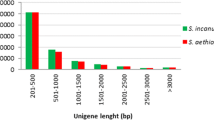

Out of total 23821 unigenes for Saengryeg 211 and 17813 unigenes for Saengryeg 213, 15007 (62.99%) and 12093 (67.88%) hit at least one significant alignment to existing gene model in blastx searches (Figure 1). The associated hits were searched for their respective GO terms derived from dynamic controlled ontologies to describe the function of genes and gene products. This yielded significant annotations representing the best possible hits which were classified into three major categories namely, biological process, cellular component functions and molecular functions. Of the assigned GO terms, 4555 and 3673 were to known biological processes function, 5032 and 4118 to cellular component function, and 5421 and 4302 to the molecular functions in Saengryeg 211 (Figure 2) and Saengryeg 213 (Figure 3), respectively, indicating a large functional diversity of genes in the transcriptomic data. However, there were still 3,795 and 3,010 sequences unclassified, for both the varieties, respectively. Functional classification of the transcripts in biological process category showed that metabolic process, transport, regulation of biological processes, response to stimulus and cellular process were among the highly represented groups indicating that the plant is undergoing rapid growth and extensive metabolic activity. Genes involved in DNA binding, catalytic and transferase activities were highly represented in molecular function category indicating dominance of gene regulation, signal transduction and enzymatically active processes. Genes involved in other important biological processes such as cell differentiation, communication, transport were also identified through GO annotations. About one third unigenes for both accessions did not hit the highly homologous sequences in the target database, probably representing novel transcripts which could be of great importance for further study.

SSR Discovery

A total of 3,766 and 2,431 potential SSR motifs, candidates for microsatellite analysis were discovered from the sequenced data for Saengryeg 211 and Saengryeg 213, respectively. Trinucleotide was the most common repeat unit with a frequency of 75.06% and 75.97%, followed by the di (10.43%; 9.62%), hexa (6.02%; 6.17%) and pentanucleotide repeats (3.63%;3.29%) in Saengryeg 211and Saengryeg 213, respectively. The GA repeat (22.3%) was the most frequent repeat motif, followed by CAG (8.7%), TGG (7.6%), GAA (6.5%), and CAT (6.0%) (Figure 4). Mononucleotide SSRs were excluded because of the frequent homopolymer errors found in the Roche 454 pyrosequencing data. The SSRs number of other types with di- and tri-nucleotides motifs was found almost the same, indicating there were some differences existing between Saengryeg 211 and Saengryeg 213.

Discussion

De novo assembly has been performed for the transcriptome analysis, function annotation and development of numerous markers in various plants (Parchman et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2010; Oliver et al. 2011) including pepper to rapidly generate a large amount of sequence data (Lu et al. 2011;2012; Ashrafi et al. 2012; Go’ngora-Castillo et al. 2012; Hill et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2013). Go’ngora-Castillo et al. (2012) and Liu et al. (2013) have introduced the recent study of pepper transcriptome (Capsicum transcriptome database).

In the present study, de novo transcriptome assembly of these two pepper varieties Saengryeg 211 and Saengryeg 213 were performed by GS Roche Assembler Newbler, which, unlike other assemblers, created isotigs from contigs that are consistently connected by a subset of reads and correspond to alternative transcripts (owing to splicing variants). The reads obtained from the sequencing runs were assembled into isotigs and singletons and were organized into 'isogroups’. Isotigs, which shared the reads, were categorized into the same isogroup. Average lengths of these isotigs were observed to be larger than lengths obtained previously, namely 100 bp for maize (Barbazuk et al. 2007), 247 bp for eucalyptus (Novaes et al. 2008) because of the enhanced performance owing to improvements for longer reads and that of the efficient Roche 454 instrumentation assembler software (Parchman et al. 2010). The majority of pepper EST sequences used in the current project as reference had been first assembled by Kim et al. (2008) in which 22,011 unigenes were assembled with an average consensus sequences length of 1,688 bp. The 454 system generates long sequences but suffers from low sequence depth. However, in recent studies for diploid genome systems in plants, where genome duplication and polyploidy are prevalent, whole genomic samples from large mapping populations are sequenced for complex traits association studies. These have mostly relied on low sequencing coverage at lower depth (2-4x) (Li et al. 2011; Deschamps et al. 2012) which is an attractive strategy for marker discovery from de novo characterized samples (Altshuler et al. 2010). The performance of the NGS technologies at low sequence coverage is correlated with per-base sequence coverage uniformity; where Roche 454, with the most uniform coverage, performs the best and suggests that for all the NGS technologies, achieving more uniform sequence coverage would result in considerably higher performance at lower coverage. It provides a powerful and cost-effective alternative to sequencing smaller numbers of individuals at high depth (Flannick et al. 2012).

The assembled sequences were functionally annotated to determine that the majority were involved in proteins with binding function, regulation and metabolism. Two-third of all assembled sequences showed a combination of some known as well as unknown hits. About half of the sequences could be linked with specific functions and the rest were unknown either because no similar sequence was present in the reference database or they matched a protein of unknown function. Approximately one-third of the assembled sequences had no hits and could not be assigned a specific functional annotation. It has been reported that the ability to detect significant sequence similarity partially depends on the length of the query sequence, many of the short sequencing reads obtained using next-generation technology cannot be matched to known genes (Lu et al. 2011). Moreover, the part of sequences showing no hits plausibly included alternative splice variants, novel gene products, and differentially expressed genes, which are of great importance for further research. The transcriptome assembly of two pepper parental lines (CM334 and Taean) and their hybrid line (TF68) has been carried out by Lu et al.2011;2012 using the GS-454 FLX Titanium to sequence mRNA that was collected from fruits of greenhouse-grown peppers. After the transcriptome assembly, the functional annotation of these contigs determined the involvement of majority of contigs in proteins with binding function, regulation and metabolism. These results are similar to our transcriptome assembly and functional annotation.

A total of 3,766 and 2431 potential SSR markers were identified from these two varieties of C. annuum genome sequences, respectively. The tri-nucleotide repeats were found to be the maximum which are more frequently detected in coding regions (Yu et al. 2011). These repeats are generally more robust since they are reported to give fewer “stutter bands” than those based on dinucleotide repeats and these trinucleotide repeats in particular have been demonstrated to be highly polymorphic and stably inherited (Yang et al. 2012). While the tri- and dinucleotides repeats mostly contributed to the major proportion of SSRs in these two varieties, a very small share was contributed by mono-, tetra-, penta- and hexa-nucleotide repeats. A similar trend was observed in other species (Sonah et al. 2011). Based on the variety of SSRs identified in this study, the future SSR marker optimization may be best focused on those comprising trinucleotide repeats. Detection of mutants by comparative marker analysis in these non-pungent and pungent chilli peppers might render new information on structural or regulatory genes that participate in capsaicinoid biosynthesis (Liu et al. 2013). It could lay a platform for better understanding the metabolic pathways in chilli pepper. However, all the predicted molecular markers need to be validated.

Conclusions

This study provides a significant strategy of a) de novo transcriptome assembly which can be potentially used for any species for broad characterization of genes; b) functional annotation of the assembled transcripts to number of putative genes related to numerous metabolic and biochemical pathways and c) identification of large numbers of high quality SSRs with diverse motifs, which upon validation could facilitate the identification of polymorphisms within the species. Combined with some recent previous works on pepper the large number of potential SSRs detected here provides a plethora of potential markers that may prove useful in multiple applications including genetic mapping and QTL analyses. Nevertheless, the ultimate goal remains to use the available genetic resources to develop new pepper varieties with higher yields, better flavours and more resistance to biotic as well as abiotic stresses.

References

Aggarwal RK, Hendre PS, Varshney RK, Bhat PR, Krishnakumar V, Singh L: Identification, characterization and utilization of EST-derived genic microsatellite markers for genome analyses of coffee and related species. Theor Appl Genet 2007,114(2):359–372. 10.1007/s00122-006-0440-x

Altshuler D, Durbin RM, Abecasis GR, Bentley DR, Chakravarti A, et al.: A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature 2010, 467: 1061–1073. 10.1038/nature09534

Ameline-Torregrosa C, Dumas B, Krajinski F, Esquerre-Tugaye MT, Jacquet C: Transcriptomic approaches to unravel plant-pathogen interactions in legumes. Euphytica 2006,147(1):25–36.

Ashrafi H, Hill T, Stoffel K, Kozik A, Yao JQ, Chin-Wo SR, Deynze AV: De novo assembly of the pepper transcriptome ( Capsicum annuum ): a benchmark for in silico discovery of SNPs, SSRs and candidate genes. BMC Genomics 2012, 13: 571. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-571

Barbazuk WB, Scott JE, Hsin DC, Li L, Patrick SS: SNP discovery via 454 transcriptome sequencing. Plant J 2007,51(5):910–918. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03193.x

Barchi L, Bonnet J, Boudet C, Signoret P, Nagy I, Lanteri S, Palloix A, Lefebvre V: A high-resolution, intraspecific linkage map of pepper ( Capsicum annuum L.) and selection of reduced recombinant inbred line subsets for fast mapping. Genome 2007,50(1):51–60. 10.1139/g06-140

Ben Chaim A, Paran I, Grube R, Jahn M, van Wijk R, Peleman J: QTL mapping of fruit related traits in pepper ( Capsicum annuum ). Theor Appl Genet 2001, 102: 1016–1028. 10.1007/s001220000461

Bosland PW, Votava E: Peppers: Vegetable and spice capsicums. Oxford, Wallingford: Cabi; 2000.

Cavagnaro PF, Senalik DA, Yang L, Simon PW, Harkins TT, Kodria CD, Huang S: Genome-wide characterization of simple sequence repeats in cucumber ( Cucumis sativus L.). BMC Genomics 2010, 11: 569–586. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-569

Cohen D, Bogeat-Triboulot MB, Tisserant E, Balzergue S, Martin-Magniette ML, Lelandais G, Ningre N, Renou JP, Tamby JP, Le Thiec D, Hummel I: Comparative transcriptomics of drought responses in populus: a meta-analysis of genome-wide expression profiling in mature leaves and root apices across two genotypes. BMC Genomics 2010,11(1):630. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-630

Csencsics D, Brodeck S, Holderegger R: Cost-effective, species-specific microsatellite development for the endangered dwarf bulrush ( Typha minima ) using next-generation sequencing technolog y . J Hered 2010, 101: 789–793. 10.1093/jhered/esq069

Deschamps S, Llaca V, May GD: Genotyping by sequencing in plants. Biology 2012,1(3):460–483. 10.3390/biology1030460

Dutta S, Kumawat G, Singh BP, et al.: Development of genic-SSR markers by deep transcriptome sequencing in pigeonpea [ Cajanus cajan (L.) Millspaugh]. BMC Plant Biol 2011, 11: 17. 10.1186/1471-2229-11-17

Flannick J, Korn JM, Fontanillas P, Grant GB, Banks E, et al.: Efficiency and power as a function of sequence coverage, SNP array density, and imputation. PLoS Comput Biol 2012,8(7):e1002604. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002604

Garg R, Patel RK, Tyagi AK, Jain M: De novo assembly of chickpea transcriptome using short reads for gene discovery and marker identification. DNA Res 2011, 1: 11.

Go’ngora-Castillo E, Fajardo-Jaime R, Ferna’ndez-Cortes A, Jofre-Garfias A, Lozoya-Gloria E, et al.: The capsicum transcriptome DB: a “hot” tool for genomic research. Bioinformation 2012,8((1):043–047.

Gore MA, Wright MH, Ersoz ES, Bouffard P, Szekeres ES, Jarvie TP, Hurwitz BL, Narechania A, Harkins TT, Grills GS, Ware DH, Buckler ES: Large-scale discovery of gene-enriched SNPs. Plant Genome 2009,2(2):121–133. 10.3835/plantgenome2009.01.0002

Hernandez-Verdugo S, Luna-Reyes R, Oyama K: Genetic structure and differentiation of wild and domesticated populations of Capsicum annuum from Mexico. Plant Syst Evol 2001, 226: 129–142. 10.1007/s006060170061

Hill TA, Ashrafi H, Chin-Wo SR, Yao J, Stoffel K, et al.: Characterization of Capsicum annuum genetic diversity and population structure based on parallel polymorphism discovery with a 30 K unigene pepper GeneChip. PLoS One 2013,8(2):e56200. 10.1371/journal.pone.0056200

Jun TH, Van K, Kim MY, Lee SH, Walker DR: Association analysis using SSR markers to find QTL for seed protein content in soybean. Euphytica 2008,162(2):179–191. 10.1007/s10681-007-9491-6

Jun TH, Michel AP, Rouf Mian MA: Development of soybean aphid genomic SSR markers using next generation sequencing. Genome 2011,54(5):360–367. 10.1139/g11-002

Jung JW, Cho MC, Cho YS: Fruit quality of once-over harvest pepper ( Capsicum annuum . L.) Cultivar 'Saengryeg No 211’ and 'Saengryeg No 213’. Kor J Hort Sci Technol 2006,24(2):205–206.

Kim DS, Kim DH, Yoo JH, Kim BD: Cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence and amplified fragment length polymorphism markers linked to the fertility restorer gene in chili pepper ( Capsicum annuum L.). Mol Cells 2006,21(1):135–140.

Kim HJ, Baek KH, Lee SW, Kim JE, Lee BW, Cho HS, Kim WT, Choi D, Hur CG: Pepper EST database: comprehensive in silico tool for analyzing the chili pepper ( Capsicum annuum ) transcriptome. BMC Plant Biol 2008,8(1):101. 10.1186/1471-2229-8-101

Kong Q, Zhang G, Chen W, Zhang Z, Zou X: Identification and development of polymorphic EST-SSR markers by sequence alignment in pepper, Capsicum annuum (Solanaceae). Am J Bot 2012, 99: e59-e61. 10.3732/ajb.1100347

Lee JM, Nahm SH, Kim YM, Kim BD: Characterization and molecular genetic mapping of microsatellite loci in pepper. Theor Appl Genet 2004,108(4):619–627. 10.1007/s00122-003-1467-x

Lee CJ, Yoo E, Shin J, Lee J, Hwang HS, Kim BD: Nonpungent Capsicum contains a deletion in the capsaicinoid synthetase gene, which allows early detection of pungency with SCAR markers. Mol Cells 2005,19(2):262–267.

Lee HR, Bae IH, Park SW, Kim HJ, Min WK, Han JH, Kim KT, Kim BD: Construction of an integrated pepper map using RFLP, SSR, CAPS, AFLP, WRKY, rRAMP, and BAC end sequences. Mol Cells 2009,27(1):21–37. 10.1007/s10059-009-0002-6

Lefebvre V, Goffinet B, Chauvet JC, Caromel B, Signoret P, Brand R, Palloix A: Evaluation of genetic distances between pepper inbred lines for cultivar protection purposes: Comparison of AFLP, RAPD and phenotypic data. Theor Appl Genet 2001, 102: 741–750. 10.1007/s001220051705

Li Y, Sidore C, Kang HM, Boehnke M, Abecasis GR: Low-coverage sequencing: implications for design of complex trait association studies. Genome Res 2011, 21: 940–951. 10.1101/gr.117259.110

Liu S, Li W, Wu Y, Chen C, Lei J: De Novo transcriptome assembly in Chili Pepper ( Capsicum frutescens ) to identify genes involved in the biosynthesis of capsaicinoids. PLoS One 2013,8(1):e48156. 10.1371/journal.pone.0048156

Livingstone KD, Lackney VK, Blauth JR, van Wijk R, Jahn MK: Genome mapping in Capsicum and the evolution of genome structure in the Solanaceae. Genetics 1999,152(3):1183–1202.

Logacheva MD, Kasianov AS, Vinogradov DV, et al.: De novo sequencing and characterization of floral transcriptome in two species of buckwheat ( Fagopyrum ). BMC Genomics 2011, 12: 30. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-30

Lu FH, Yoon MY, Cho YI, et al.: Transcriptome analysis and SNP ⁄ SSR marker information of red pepper variety YCM334 and Taean. Sci Hortic 2011, 129: 38–45. 10.1016/j.scienta.2011.03.003

Lu FH, Cho MC, Park YJ: Transcriptome profiling and molecular marker discovery in red pepper, Capsicum annuum L. TF68. Mol Biol Rep 2012, 39: 3327–3335. 10.1007/s11033-011-1102-x

McDowell ET, Kapteyn J, Schmidt A, et al.: Comparative functional genomic analysis of Solanum glandular trichome types. Plant Physiol 2011, 155: 524–539. 10.1104/pp.110.167114

Mian MAR, Kang ST, Beil SE, Hammond RB: Genetic linkage mapping of the soybean aphid resistance gene in PI 243540. Theor Appl Genet 2008,117(6):955–962. 10.1007/s00122-008-0835-y

Minamiyama Y, Tsuro M, Hirai M: An SSR-based linkage map of Capsicum annuum . Mol Breeding 2006,18(2):157–169. 10.1007/s11032-006-9024-3

Mizrachi E, Hefer CA, Ranik M, Joubert F, Myburg AA: De novo assembled expressed gene catalog of a fast-growing Eucalyptus tree produced by Illumina mRNA-Seq. BMC Genomics 2010, 11: 681. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-681

Modrek B, Lee C: A genomic view of alternative splicing. Nat Genet 2002, 30: 13–19. 10.1038/ng0102-13

Novaes E, Drost DR, Farmerie WG, Pappas GJ Jr, et al.: High-throughput gene and SNP discovery in Eucalyptus grandis, an uncharacterized genome. BMC Genomics 2008, 9: 312. 10.1186/1471-2164-9-312

Oliver RE, Lazo GR, Lutz JD, et al.: Model SNP development for complex genomes based on hexaploid oat using high-throughput 454 sequencing technology. BMC Genomics 2011, 12: 77. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-77

Oyama K, Hernandez-Verdugo S, Sanchez C, Gonzalez-Rodriguez A, Sanchez-Pena P, Garzon-Tiznado JA, Casas A: Genetic structure of wild and domesticated populations of Capsicum annuum (Solanaceae) from northwestern Mexico analyzed by RAPDs. Genet Resour Crop Evol 2006, 53: 553–562. 10.1007/s10722-004-2363-1

Paran I, van der Voort JR, Lefebvre V, Jahn M, Landry L, van Schriek M, Tanyolac B, Caranta C, Chaim AB, Livingstone K, et al.: An integrated genetic linkage map of pepper ( Capsicum spp.). Mol Breed 2004,13(3):251–261.

Parchman T, Geist K, Grahnen J, Benkman C, Buerkle C: Transcriptome sequencing in an ecologically important tree species: assembly, annotation, and marker discovery. BMC Genomics 2010,11(1):180. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-180

Perry L, Dickau R, Zarrillo S, Holst I, Pearsall DM, et al.: Starch fossils and the domestication and dispersal of chili peppers (Capsicum spp. L.) in the americas. Science 2007, 315: 986–988. 10.1126/science.1136914

Prince JP, Lackney VK, Angeles C, Blauth JR, Kyle MM: A survey of DNA polymorphism within the genus Capsicum and the fingerprinting of pepper cultivars. Genome 1995, 38: 224–231. 10.1139/g95-027

Rao GU, Ben Chaim A, Borovsky Y, Paran I: Mapping of yield-related QTLs in pepper in an interspecific cross of Capsicum annuum and C. frutescens . Theor Appl Genet 2003,106(8):1457–1466.

Roberts GC, Smith CWJ: Alternative splicing: combinatorial output from the genome. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2002,6(3):375–383. 10.1016/S1367-5931(02)00320-4

Saha MC, Cooper JD, Mian MAR, Chekhovskiy K, May GD: Tall fescue genomic SSR markers: development and transferability across multiple grass species. Theor Appl Genet 2006,113(8):1449–1458. 10.1007/s00122-006-0391-2

Sloan DB, Keller SR, Berardi AE, Sanderson BJ, Karpovich JF, Taylor DR: De novo transcriptome assembly and polymorphism detection in the flowering plant Silene vulgaris (Caryophyllaceae). Mol Ecol Resour 2012,12(2):333–343. 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2011.03079.x

Sonah H, Deshmukh RK, Sharma A, Singh VP, Gupta DK, Gacche RN, Rana JC, Singh NK, Sharma TR: Genome-wide distribution and organization of microsatellites in plants: an insight into marker development in Brachypodium . PLoS One 2011, 6: e21298. 10.1371/journal.pone.0021298

Tangphatsornruang S, Somta P, Uthaipaisanwong P, Chanprasert J, Sangsrakru D, Seehalak W, Sommanas W, Tragoonrung S, Srinives P: Characterization of microsatellites and gene contents from genome shotgun sequences of mungbean [ Vigna radiata (L) Wilczek]. BMC Plant Biol 2009, 9: 137–148. 10.1186/1471-2229-9-137

Temnykh S, DeClerck G, Lukashova A, Lipovich L, Cartinhour S, McCouch S: Computational and experimental analysis of microsatellites in rice ( Oryza sativa L.): Frequency, length variation, transposon associations, and genetic marker potential. Genome Res 2001, 11: 1441–1452. 10.1101/gr.184001

Truong HTH, Kim KT, Kim S, Chae Y, Park JH, Oh DG, Cho MC: Comparative mapping of consensus SSR markers in an intraspecific F 8 recombinant inbred line population in Capsicum. Hort Environ Biotechnol. 2010,51(3):193–206.

Wang Z, Fang B, Chen J, Zhang X, Luo Z, Huang L, Chen X, Li Y: De novo assembly and characterization of root transcriptome using Illumina paired-end sequencing and development of SSR markers in sweetpotato ( Ipomoea batatas ). BMC Genomics 2010, 11: 726. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-726

Wu F, Eannetta N, Xu Y, Durrett R, Mazourek M, et al.: A COSII genetic map of the pepper genome provides a detailed picture of synteny with tomato and new insights into recent chromosome evolution in the genus Capsicum . Theor Appl Genet 2009, 118: 1279–1293. 10.1007/s00122-009-0980-y

Xu DH, Abe J, Gai JY, Shimamoto Y: Diversity of chloroplast DNA SSRs in wild and cultivated soybeans: evidence for multiple origins of cultivated soybean. Theor and Appl Genetics 2003, 105: 645–653.

Yang T, Bao SY, et al.: High-throughput novel microsatellite marker of faba bean via next generation sequencing. BMC Genomics 2012, 13: 602. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-602

Yi G, Lee J, Lee S, Choi D, Kim BD: Exploitation of pepper EST-SSRs and an SSR-based linkage map. Theor Appl Genet 2006,114(1):113–130. 10.1007/s00122-006-0415-y

You FM, Huo N, Del KR, Gu YQ, Luo MC, McGuire PE, Dvorak J, Anderson OA: Annotation-based genome-wide SNP discovery in the large and complex Aegilops tauschii genome using next-generation sequencing without a reference genome sequence. BMC Genomics 2011, 12: 59. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-59

Yu JN, Won C, Jun J, Lim Y, Kwak M: Fast and Cost-Effective Mining of Microsatellite Markers Using NGS Technology: An Example of a Korean Water Deer Hydropotes inermis argyropus . PLoS One 2011,6(11):e26933. 10.1371/journal.pone.0026933

Zalapa JE, Cuevas H, Zhu H, Steffan S, Senalik D, Zeldin E, McCown B, Harbut R, Simon P: Using next-generation sequencing approaches to isolate simple sequence repeat (SSR) loci in the plant sciences. Am J Bot 2012,99(2):193–208. 10.3732/ajb.1100394

Zhu H, Senalik D, McCown BH, Zeldin EL, Speers J, Hyman J, Bassil N, Hummer K, Simon PW, Zalapa JE: Mining and validation of pyrosequenced simple sequence repeats (SSRs) from American cranberry ( Vaccinium macrocarpon Ait.). Theor Appl Genet 2012, 124: 87–96. 10.1007/s00122-011-1689-2

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the Next-Generation BioGreen 21 Program (Plant Molecular Breeding Center No. PJ008024), Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Y-IC, J-HK carried out the population and genetic studies. J-HK, ST, Y-IC participated in the molecular biology experiments and data analysis. ST drafted the manuscript. H-EL, M-CC participated in the design of the study. D-SK, J-GW participated in the design of the study and its coordination. Y-KA conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahn, YK., Tripathi, S., Cho, YI. et al. De novo transcriptome assembly and novel microsatellite marker information in Capsicum annuum varieties Saengryeg 211 and Saengryeg 213. Bot Stud 54, 58 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1999-3110-54-58

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1999-3110-54-58