Abstract

We trace the evolution of research on extreme solar and solar-terrestrial events from the 1859 Carrington event to the rapid development of the last twenty years. Our focus is on the largest observed/inferred/theoretical cases of sunspot groups, flares on the Sun and Sun-like stars, coronal mass ejections, solar proton events, and geomagnetic storms. The reviewed studies are based on modern observations, historical or long-term data including the auroral and cosmogenic radionuclide record, and Kepler observations of Sun-like stars. We compile a table of 100- and 1000-year events based on occurrence frequency distributions for the space weather phenomena listed above. Questions considered include the Sun-like nature of superflare stars and the existence of impactful but unpredictable solar "black swans" and extreme "dragon king" solar phenomena that can involve different physics from that operating in events which are merely large.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Research on extreme solar and solar-terrestrial activity dates to the notable event of 1859 (Carrington 1859; Hodgson 1859; Stewart 1861), but it is only within the last twenty years that extreme events, as a separate class, have been examined in detail. The threat posed by extreme space weather events to Earth’s technological infrastructure provided much of the impetus for this development. Detailed studies of the impact of a severe space weather event on modern society have been conducted by the US National Research Council (NRC; 2008), Lloyds of London (2010), JASON (2011), and the UK Royal Academy of Engineering (2013), among others.Footnote 1 The NRC report contains an estimate for the economic costs of such a storm of “$1 trillion to $2 trillion during the first year alone … with recovery times of 4–10 years”. From the Lloyds’ report: “Sustained loss of power could mean that society reverts to nineteenth century practices. Severe space weather events that could cause such a major impact may be rare, but they are nonetheless a risk and cannot be completely discounted.”

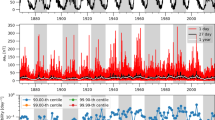

The investigation of extreme space weather has broadened as new windows—historical cosmogenic nuclide events (Miyake et al. 2012) and Kepler observations of flares on Sun-like stars (Maehara et al. 2012)—were opened. In this review, we trace the evolution of research on extreme solar activity and review work on the limits of the various types of extreme space weather and their occurrence probabilities.

1.1 1859: in the beginning

Richard Carrington, the accomplished nineteenth century English astronomer (Cliver and Keer 2012), described his discovery of the first solar flare—on 1 September 1859—in a brief Monthly Notices paper that is a mixture of scientific rigor (e.g., avoiding any correspondence with Hodgson, who also observed the flare, to maintain the independence of their accounts), excitement (“being somewhat flurried by the surprise, I hastily ran to call someone to witness the exhibition with me, and on returning within 60 s, was mortified to find that it [the flare] was already much changed and enfeebled”), and caution (“While the contemporary occurrence [of solar flare and geomagnetic disturbance] may deserve noting, he [Carrington] would not have it supposed that he even leans toward hastily connecting them. ‘One swallow does not make a summer.’”). From his detailed account of the "singular appearance seen in the Sun", it seems clear that Carrington knew that the transient bright emission patches he observed in the large spot group near central meridian (Fig. 1) represented a new and important solar phenomenon. What he could not know was that the “sudden conflagration” he observed on the Sun and the ensuing geomagnetic storm were historically large—possibly the largest that have been directly observed (Cliver and Dietrich 2013). It was recognized at the time that the 1859 magnetic storm was strong, but just how strong was hard to say. It was accompanied by a widespread aurora (Loomis 1859, 1860, 1861) and the magnetometers at Greenwich (east of London) and Kew (west), both near to Carrington’s observatory in Reigate (south of London) and Hodgson’s in Highgate (north), were driven off-scale, but systematic magnetic records only dated from the 1830s (Chapman and Bartels 1940) and there was little basis for comparison.

Image reproduced with permission from Cliver and Keer (2012), copyright by Springer; the enlarged portion of RGO 67/266 in (B) is reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library

a Carrington’s (1859) carefully executed drawing of his sunspot group 520 on 1 September 1859, the first visual record of a solar flare. The initial (A and B) and final (C and D) positions of the white-light emission are indicated. Solar east is to the right. b Enlargement of region 520 from an early solar photograph made at Kew Observatory by Warren De la Rue on 31 August 1859.

1.2 2003–2004: surge in interest in extreme events

The establishment of the extreme strength of the Carrington storm awaited the study by Tsurutani et al. (2003) who analyzed long-buried geomagnetic observations of the event from Colaba Observatory where the automatic recording that led to off-scale readings at Greenwich and Kew had not yet been instituted. The manual observations at ~ 10-min intervals at Bombay indicated a storm three times as intense as any that has been observed since. While the three-times assessment is likely an overestimate (Akasofu and Kamide 2005; Siscoe et al. 2006; Cliver and Dietrich 2013), the 1859 storm remains among the strongest events ever observed (Hayakawa et al. 2020c, 2022). The year 2003 was ripe for a renewed appreciation of the intensity of the Carrington storm. The discipline of space weather was becoming established and interest in long-term space weather, sparked by Eddy’s (1976) rediscovery of the Maunder Minimum, was fueled by the concern of global warming. The journal Space Weather began publication in 2003 (Lanzerotti 2003) and a series of Space Climate Symposia (Mursula et al. 2004) was inaugurated in 2004. In this context, the Tsurutani et al. (2003) paper became a seminal paper for research on extreme solar activity.

The NASA Astrophysics Data System (ADS) annual citation rate for Carrington's Monthly Notices paper on the 1859 event (Fig. 2) shows the recent growth of interest in the first recognized extreme solar event and in extreme events generally. The citation spike in 2006 reflects the publication in Advances in Space Research of the proceedings of a workshop on the Carrington event at the University of Michigan in late 2003 (Clauer and Siscoe 2006).

Recent growth (through 2020) in citations to Carrington's (1859) Monthly Notices paper on the discovery of the 1859 flare

In 2004, Cliver and Svalgaard presented a paper at the first Space Climate Symposium that listed the observed/inferred extreme values of: the peak intensity of solar flares (based on soft X-ray observations and magnetic crochet amplitudes); Sun-Earth disturbance transit time (a proxy for the average speed of coronal mass ejections (CMEs)); solar proton event amplitude, inferred—erroneously, it now appears (Wolff et al. 2012; Sukhodolov et al. 2017)—from nitrate concentrations in ice cores; geomagnetic storm intensity; and low-latitude auroral extent. The limiting cases of the various types of events they considered are analogous to the 100-year floods or hurricanes of terrestrial climate. Note the inclusion of the CME (Webb and Howard 2012), intermediary to flare and storm, in this list of space weather phenomena. CMEs are a relatively new aspect of solar activity first directly observed in the early 1970s (Koomen et al. 1974, and references therein; Gopalswamy 2016) that were pointedly brought to the forefront in solar-terrestrial physics by Gosling (1993) with an important precursor in Kahler (1992).

1.3 2012: new windows

The year 2012 witnessed significant advances, based on disparate data sets, in the study of extreme solar activity. Miyake et al. (2012) obtained high-time-resolution measurements of the 14C concentration in the tree rings of two Japanese cedar trees that showed a transient increase of ~ 12‰ from 774 to 775 AD (Fig. 3). The origin of the 774–775 AD 14C enhancement was immediately a matter of debate. Was it caused by a very large solar energetic proton (SEP) event (or a closely-spaced cluster of high-energy proton events such as occurred from August to October 1989) (Usoskin et al. 2013) or by a galactic gamma-ray burst (GRB; Hambaryan and Neuhäuser 2013; Pavlov et al. 2013a, b)? Since 2012, numerous studies, including a multi-isotope investigation (Mekhaldi et al. 2015) of the 774–775 AD cosmogenic-nuclide event and a similar event in 993–994 AD discovered by Miyake et al. (2013), have provided strong evidence for the solar scenario (Miyake et al. 2020a).

Image reproduced with permission from Miyake et al. (2012), copyright by Macmillan

Measured 14C content at 1–2-year time resolution for two Japanese cedar trees showing the cosmogenic nuclide event of 774–775 AD.

Potential evidence far from the Sun bearing on the limits of the strength of solar flares was provided by the precise, long-term, and continuous photometry of stars by the Kepler satellite (Koch et al. 2010) that had the search for extra-solar planets as its primary task. For the first 120 days of the Kepler mission, Maehara et al. (2012) reported the observations of 14 superflares (with energy > 1034 erg) on 14,000 Sun-like stars slowly-rotating G-type main-sequence stars with surface temperatures of 5600–6000 K). They calculated that a flare with bolometric energy > 1034 erg could occur on a Sun-like star once every 800 years. The question of whether the Sun in its present state is capable of producing a flare of this size remains unsettled (Aulanier et al. 2013; Shibata et al. 2013; Tschernitz et al. 2018; Schmieder 2018; Notsu et al. 2019; Okamoto et al. 2021). In a detailed survey of 38 large eruptive (i.e., CME-associated) solar flares from 2002 to 2006, Emslie et al. (2012) found that the X28 soft X-ray flare on 4 November 2003 had the largest radiative energy (4.3 × 1032 erg), while the X17 flare on 28 October 2003 had the largest total (radiative plus CME kinetic energy) energy (1.6 × 1033 erg). The corresponding inferred values for the Carrington flare are essentially identical to these estimates: ~ 5 × 1032 erg (bolometric) and ~ 2 × 1033 erg (total) (Cliver and Dietrich 2013).

There was a further important development in 2012. On 23 July of that year a major backside eruption on the Sun was observed both remotely and in situ by the STEREO spacecraft (Kaiser et al. 2008). Work by several teams of investigators (Russell et al. 2013; Baker et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2014a, b; Riley et al. 2016; cf. Ngwira et al. 2013) indicated that had the eruption occurred on the front side of the Sun, it might have produced a magnetic storm greater than that inferred for the Carrington event.

1.4 Subsequent developments

Hayakawa et al. (2017) presented evidence for a space weather event in 1770 that rivaled or exceeded aspects of the 1859 event. Aurorae from 16 to 18 September 1770 were observed at geomagnetic latitudes as low as ~ 20° in both the southern and northern hemispheres, comparable to those following the 1859 event, and the estimated area of the likely associated sunspot region (from a contemporary drawing) was ~ 6000 millionths of a solar hemisphere, approximately three times that of the mean area for the source region of the Carrington flare (Newton 1943; Jones 1955). Similarly, Love et al. (2019c) deduced a minimum Dst intensity for the 15 May 1921 geomagnetic storm that equaled (within uncertainties) that inferred for the Carrington storm. Other developments include the Knipp et al. (2016) review of the notable May 1967 space weather event which drew attention to an aspect of extreme space weather that deserves increased attention—extreme radio bursts that pose a threat to radar operations and radio communications (e.g., Cerruti et al. 2008)—and the discovery and verification of a third historical cosmogenic nuclide event in ~ 660 BC (Park et al. 2017; O’Hare et al. 2019) that was comparable to the 774–775 AD event. More recently, Cliver et al. (2020b) inferred a bolometric energy of ~ 2 × 1033 erg for the flare associated with the 774 AD proton event and Reinhold et al. (2020) presented evidence suggesting that the Sun is currently in a state of subdued activity relative to its stellar peers.

1.5 Related work

Previous reviews on extreme events have been published by Riley (2012), Schrijver et al. (2012), Hudson (2015, 2021), Riley et al. (2018), Gopalswamy (2018) and Hapgood et al. (2021). Here, in addition to the phenomena of solar flares, CMEs, geomagnetic storms, and low-energy proton events, we consider sunspot groups, flares on Sun-like stars, solar radio bursts, fast transit interplanetary coronal mass ejections (ICMEs), low-latitude aurorae, and high-energy proton events that give rise to cosmogenic nuclide enhancements—topics that were not included or were more lightly treated in the reviews of extreme events listed above. We do not, however, consider the effects of extreme solar events on the ionosphere (e.g., sudden ionospheric disturbances and polar cap absorption events), atmosphere (e.g., ozone depletion) and lithosphere (e.g., geomagnetically induced currents), all of which are addressed by Riley et al. (2018). The emphasis in Hapgood et al. (2021) is on the terrestrial impacts of extreme solar activity. Recent reviews by Tsurutani et al. (2020) and Temmer (2021) focuses on space weather generally. Although the rarity of extreme events makes their footing less certain, there is evidence for certain of the phenomena we consider that the physics of extreme space weather events can differ from that in events which are merely large.

Our focus will be on the largest directly observed, inferred, and theoretically derived values of size/intensity measures of the various types of solar emissions and of geomagnetic storms. For solar flares, geomagnetic storms, and solar proton events, long-term indirect observations are provided by magnetograms (via magnetic crochets), auroral records, and cosmogenic nuclide data, respectively. We compile lists of the largest observed events in each category for comparison with future events and tabulate estimates of 100- and 1000-year events based on occurrence probability distribution functions.

In Sects. 2–7 we consider the different types of extreme activity, in turn, and in Sect. 8 we present and discuss a summary table of extreme events.

2 Sunspot groups

2.1 100- and 1000-year spot groups

The primary data base used to estimate the areas of 100-year and 1000-year solar spot groups is that compiled at the Royal Greenwich Observatory from 1874 to 1976 (RGO; Willis et al. 2013a, b; Erwin et al. 2013) and extended to the present using data from the US Air Force’s Solar Observing Optical Network (SOON) and other observatories (Muñoz-Jaramillo et al. 2015; Giersch et al. 2018; Mandal et al. 2020).Footnote 2 Such estimates begin with histograms of projection-corrected spot group areas (measured in millionths of a solar hemisphere (μsh; 1 μsh = 3.0 × 106 km2)). Various functional forms have been used to fit the size distribution of spot groups, dependent in part on the data sets and time intervals considered.

Bogdan et al. (1988), Baumann and Solanki (2005), and Leuzzi et al. (2018) used lognormal functions to fit distributions of group spot areas. Baumann and Solanki considered the RGO data set from 1874 to 1976, restricting their analysis to groups within ± 30° from central meridian, to minimize the errors resulting from visibility corrections. They only considered groups with umbral areas > 15 μsh and total areas > 60 μsh in their fits because of intrinsic measurement errors and distortion due to seeing for small groups. Their lognormal number density functions for the maximum (peak value observed during disk passage) and instantaneous (all daily observations), umbral and total (umbral plus penumbral), group areas are shown in Fig. 4. In Fig. 4b, the curves for maximum and snapshot total spot areas are essentially identical.

Image reproduced with permission from Baumann and Solanki (2005), copyright by ESO

a Size distribution of maximum (circles) and instantaneous (crosses) sunspot group umbral areas. b Same as a for total group areas. The log-normal fits are over-plotted. The vertical lines indicate the smallest areas considered for the fits.

Double or bi-lognormal functions have also been used to fit distributions of spot group areas (Kuklin 1980; Nagovitsyn et al. 2012, 2017; Nagovitsyn and Pevtsov et al. 2021). Nagovitsyn and Pevtsov considered the maximum total areas of groups observed by Greenwich from 1874 to 1976 and from Kislovodsk Mountain Astronomical Station (KMAS) from 1977 to 2018. The crossover point for the two lognormal distributions of Nagovitsyn and Pevtsov corresponds to the 60 μsh lower limit of the area range that Baumann and Solanki considered for their single lognormal distribution. From analysis of instantaneous group areas from multiple data sets including RGO and KMAS, Muñoz-Jaramillo et al. (2015) concluded that while the larger spot groups had a lognormal distribution, the smaller groups were better represented by a Weibull (1951) function (cf. Nagovitsyn and Pevtsov 2021).

Figure 5 shows a comparison made by Muñoz-Jaramillo et al. (2015) of fits to the instantaneous total group sunspot number area from RGO for four different functions: lognormal, power law, exponential, and Weibull. For the five data sets Muñoz-Jaramillo et al. considered (RGO, KMAS, SOON, Pulkovo Observatory (Nagovitsyn et al. 2008), and the Heliospheric and Magnetic Imager (HMI; Scherrer et al. 2012) on the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO; Pesnell et al. 2012), the best fit was provided by the Weibull function distribution in each case although it only passed the Kolomogorov-Smirnov test for the HMI data set.

Image reproduced with permission from Muñoz-Jaramillo et al. (2015), copyright by AAS

Distribution of the instantaneous total group sunspot area from RGO, fitted by four different functions. The dark-gray shaded area indicates the range over which the fits were made.

Figure 6 shows a downward cumulative distribution of spot group areas (left hand axis) from Gopalswamy et al. (2018) for a data set consisting of observed daily whole sunspot areas for spot groups from 1874 to 2016 (based on RGO data from 1874 to 1976 and SOON data after 1976). The blue curve is a modified exponential function to the annualized distribution on the right hand axis

Downward cumulative distribution (left hand axis) of the number of solar spot groups from 1874 to 2016 with instantaneously-measured total areas greater than a given value A (black circle data points). This annualized distribution (right hand axis) is fitted with a modified exponential function (solid blue line) and power-law (dashed red line; for the tail of the distribution) to give the occurrence frequency distribution (OFD). The fit parameters to Eq. (1; exponential) and Eq. (2; power law) are given in the figure. The intersections of the dashed horizontal lines with the fitted curves give the areas of the 100-year and 1000-year spot groups. Adapted from Gopalswamy (2018)

with a normalization factor (a), in addition to location (b) and scale (c) parameters, that gives the occurrence frequency distribution (OFD).Footnote 3 The scale factor (c) reflects the spread of the distribution in the X-parameter. The data are fitted to this function by making an initial guess of the three parameters and using an IDL routine called MPFIT (e.g., https://pages.physics.wisc.edu/~craigm/idl/fitting.html) (Gopalswamy, personal communication, 2021) to determine the best-fit values.

Gopalswamy (2018) also obtained a power-law fit (Newman 2005) for the tail of the distribution (dashed red line),

with the minimum X-value determined by the maximum-likelihood estimator (MLE; Clauset et al. 2009). The parameters for both the exponential and power-law fits are given in the figure. In both Eqs. (1) and (2), X is the log of the spot group area and Y is the log of the number of number of groups per year for this area.

Equations (1) and (2) define occurrence frequency distributions (OFDs) that give the probability of a spot group with area A ≥ a given value occurring during one year. The intersection of the exponential and power-law fits with the dashed horizontal lines drawn from 10−2 and 10−3 on the right-hand y-axis indicate the spot areas of 100-year and 1000-year spot groups. The exponential fit indicates a maximum 100-year spot area of 5780 μsh sunspot that is comparable to the largest (corrected for foreshortening) whole sunspot area of 6132 μsh for Greenwich sunspot group 14886 on 8 April 1947 (Newton 1955). The corresponding estimate for a 1000-year sunspot is 8200 μsh. The power-law fit yields 100-year and 1000-year estimates for maximum group areas of 7100 and 13,600 μsh.

From the above it is clear that the choice of a function to fit a size distribution is not straightforward and the form used will affect the 100-year and 1000-year estimates obtained. For this reason we adopt a conservative empirical approach that favors the modified exponential function of Gopalswamy (2018) for several of the phenomena considered below; with its three free parameters, this function generally fits distributions well over their full parameter range, as in Fig. 6. Because power-law functions are commonly used for flare X-ray and radio distributions (e.g., Aschwanden 2014), we consider them as well, comparing exponential and power-law 100-year and 1000-year event estimates when both functions are available.

2.2 Sunspot groups versus active regions

To date, sunspot group area is the parameter most commonly used to make estimates of the largest possible solar flare (as discussed in Sect. 3.1.7 below). This is likely due to the ready availability of the digital RGO record but there is no guarantee that group spot area is the optimum parameter from which to determine the limiting energy of extreme flares. The entire magnetic active region (AR) determines field configuration, although spots dominate where the (free) energy can be stored. Harvey and Zwaan (1993) considered AR size at maximum development and found a power law with slope close to − 2 for the distribution, without a clear indication of turnover at the largest sizes. It may well be significant that sunspot groups (the strong core fields of active regions) have a lognormal distribution while AR sizes that include more dispersed peripheries have a power law.

3 Flares on the sun and sun-like stars

3.1 Solar flares

3.1.1 Solar flare soft X-ray burst classification

The current standard measure for solar flare intensity is the widely-used Geostationary Environmental Satellite System (GOES) ABCMX SXR classification system which is defined as follows: SXR classes A1-9 through X1-9 correspond to flare peak 1–8 Å fluxes of 1–9 × 10−n W m−2 where n = 8, 7, 6, 5, and 4, for classes A, B, C, M, and X, respectively. Occasionally, flares are observed which peak intensities ≥ 10−3 W m−2. Rather than being assigned a separate letter designation, such flares are referred to as X10 events and above.Footnote 4

Approximately 20 flares of class X10 or higher have been observed during the last ~ 40 years.Footnote 5 The largest GOES SXR flare yet recorded occurred on 4 November 2003. The 1–8 Å detector saturated at a level of X18.4, with an estimated SXR class of X35 ± 5 (Cliver and Dietrich 2013) based on consideration of values given in Kiplinger and Garcia (2004), Thomson et al. (2004, 2005), Brodrick et al. (2005), and Tranquille et al. (2009). The bulk of the SXR class estimates for this flare were obtained via comparisons of flare SXR intensities and the amplitudes of flare-associated sudden ionospheric disturbances (SIDs; Mitra 1974; Prölls 2004; Tsurutani et al. 2009) caused by energetic flare photons leading to increased electrical conductivity in the day-side ionosphere, e.g., the magnetic crochet observed for the 1859 event. Cliver and Dietrich (2013) obtained an estimate for the Carrington flare of X45 ± 5 based on the magnetic crochet (a type of SID recorded by ground-based magnetometers) observed for this event (Cliver and Svalgaard 2004; Boteler 2006; Clarke et al. 2010). The November 2003 and September 1859 flares provide the current benchmarks for extreme flare activity. Less certain is an estimate of X285 ± 140 (Cliver et al. 2020b: Sect. 7.8 below) for the flare associated with the inferred SEP event of 774 AD (Miyake et al. 2012; Usoskin et al. 2013). Because flares such as those observed/inferred in 1859 and 774 AD are rare, we need to look at the ensemble of lesser flares observed by the GOES system since 1976 to estimate the occurrence frequency of extreme flares of this size and larger.

3.1.2 Solar flare frequency distributions

The GOES 1−8 Å soft X-ray measurements provide the longest, uninterrupted, and uniformly calibrated data set available for solar flares. Thus these records provide the basis for statistical studies that seek to establish the frequency of occurrence of flares as a function of flare magnitude. The most often used magnitude metric is the peak intensity of the flare as measured in that passband (expressed in W m−2), i.e., the ABCMX GOES classification.

Flares of classes A and B are under-reported in the GOES records because during active phases of the solar cycle such faint flares are often hard to separate from (or detect above) the supposedly quiescent background and are judged to be of low interest. As a further complication, flare magnitude is often not corrected for background emission, so that the weak flares that are reported are intrinsically overestimated in their strength. The least observationally biased records are those for flares of classes C, M, and X.

Many studies over the past decades have established that, at least for the larger flares, the frequency distribution for peak brightness of flares is well approximated by a power law (a thorough review in the literature of power-law fits to flare strength parameters can be found in Aschwanden et al. (2016) who also discuss waiting time distributions). The first such distribution listed by Aschwanden is that of Akabane (1956) who presented a distribution for burst peak radio intensities at 3.0 GHz. Subsequently, Hudson et al. (1969) showed a frequency histogram based on solar hard X-rays as observed by the Orbiting Solar Observatory (OSO-3) satellite that, with hindsight, hints at a power-law distribution for the more intense flares, although it lacks an explicit power-law fit to the data. Such an approximation was made by Drake (1971) based on soft X-ray measurements by the Explorer 33 and 35 spacecraft. Similar power-law distributions were first reported a few years earlier for UV Ceti type flare stars (very cool main sequence stars that exhibit frequent flaring; e.g., Kunkel 1968; Gershberg 1972; Lacy et al. 1976; Kowalski et al. 2013).

Rosner and Vaiana (1978) suggested that one way to create such frequency distributions would be to have a system in which exponential growth in stored energy is interrupted at random times by a flare-like event in which a substantial amount of the stored energy is removed from the system. But if such an energy build-up would occur in regions on the solar surface, a correlation between flare brightness and waiting time would be expected. The absence of such a correlation in both solar observations (Aschwanden et al. 1998) and stellar data (as already noted by, e.g., Lacy et al. 1976) led to other ideas, including that of self-organized criticality (SOC; Bak et al. 1987, 1988; applied to solar flares by Lu and Hamilton 1991). The SOC model for solar flares is based on the assumption that flares occur as a time-varying, or non-stationary, Poisson process. We point the reader to Aschwanden et al. (1998, 2016) for descriptions of the developments of such interpretations, focusing here on the distribution functions rather than the processes behind them.

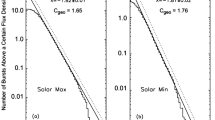

In an extensive study of ~ 50,000 GOES SXR bursts observed over a 25-year period from 1976 through 2000–38,000 of which were in classes C-X, Veronig et al. (2002a) obtained well-defined fluence and peak flux distributions that could be fitted by power laws with similar exponents: − 2.03 ± 0.09 and − 2.11 ± 0.13, respectively. These power-law approximations to the frequency distribution hold for over 2.5 orders of magnitude, with no significant indication of a change in behavior up to the largest flares observed. At a flare magnitude bin at ~ X15 (based on only two flares), the histogram simply aborts at the end of a straight power law (Fig. 7).

Image reproduced with permission from Veronig et al. (2002a), copyright by ESO

Frequency distribution of flare 1–8 Å peak flux with least squares fit for GOES SXR flares from 1976 to 2000.

The work by Gopalswamy (2018) includes a comparable analysis of flare magnitudes over a 47-year period from 1969 through 2016, including 55,285 flares of class C1 or larger (it did not consider the ~ 11,500 B class flares included in the Veronig et al. 2002a, sample). This larger sample was obtained over a time base that almost doubles that of Veronig et al. (2002a) by including more recent data and also extending the GOES records with Solar Radiation (SOLRAD) satellite data for the period 1969–1975. The downward-cumulative representation of the frequency distribution for that data set (Fig. 8) exhibits a deviation from a power-law distribution (see also, e.g., Riley 2012). In a log–log downward cumulative representation, an approximation by power laws suggests a break towards less-frequent larger flares somewhere around X4, defined by a total of about 100 flares at that magnitude or larger. Such a downward break is consistent with the conclusions reached by Schrijver et al. (2012).

Downward cumulative distribution (left hand axis) of the number of flares from 1969 to 2016 with peak SXR fluxes greater than a given value F (blue diamond and red circle data points). This annualized distribution (right hand axis) is fitted with a modified exponential function (solid blue line) and power law (dashed red line; for the tail of the distribution (red circle data points)) to give the occurrence frequency distribution. The fit equations and parameters are given in the figure. Adapted from Gopalswamy (2018)

The century- and millennium-level flares based on the modified exponential function fit to the SXR peak values in Fig. 8 are X44 and X101, respectively. The corresponding bolometric energy values from Gopalswamy (2018) are ~ 4 × 1032 erg and ~ 1033 erg. The 100- and 1000-year estimates based on power laws are comparable (X42 and X115; ~ 4 × 1032 erg and ~ 1.2 × 1033 erg). Both functional forms fit the tail of the distribution well. For a 10,000-year flare, the exponential function yields ~ X200 versus ~ X310 for the power-law fit.

While the radiative energy of the strongest observed solar flare is often given variously as 1032 erg, about 1032 erg, or ~ 1032 erg (e.g., Candelaresi et al. 2014; Peter et al. 2014; Osten and Wolk 2015; Hudson 2016; Maehara et al. 2017; Notsu et al. 2019; Brasseur et al. 2019), the measured value is a half-decade larger. Emslie et al. (2012) reported that the inferred/observed radiative energies of 12 events from 2002 to 2006 were above the 1032 erg threshold. For the three largest such events (4 November 2003, 4.3 × 1032 erg, X35 ± 5; 28 October 2003, 3.6 × 1032 erg, X17; 7 September 2005, 3.2 × 1032 erg, X17), the bolometric energy was measured directly by the Total Irradiance Monitor (TIM; Kopp and Lawrence 2005) on the Solar Radiation and Climate Experiment (SORCE; Rottman 2005). Thus, the largest observed (November 2003) and inferred (September 1859; ~ 5 × 1032 erg, ensemble estimate of X45 ± 5; Cliver and Dietrich 2013; based on electromagnetic emissions) flares are comparable to the 100-year flare given by Fig. 8.

3.1.3 White-light flares

The flare Carrington and Hodgson independently recorded on 1 September 1859 was observed in integrated light. Thus their Monthly Notices papers were the first reports of what came to be known as “white light flares” (WLFs). A compilation of reports of such events from (1859–1982) is given in Neidig and Cliver (1983a). At that time, Neidig and Cliver (1983b) reckoned that such flares were relatively rare, with an occurrence frequency of ~ 15 per year based on a ~ 2.5-year period from June 1980 to December 1982 following the maximum of solar cycle 21. They determined that a flare with SXR class ≥ X2 originating in a large (≥ 500 μsh), magnetically complex, sunspot group was a sufficient condition for a white light flare. Two decades later, Hudson et al. (2006) used Transition Region and Coronal Explorer (TRACE; Handy et al. 1999) images, which encompassed a wavelength range from 1500 to 4000 Å, and identified 11 white-light flares that had SXR classes ranging from C1.6 to M9.1 (median = M1.2) to “support the conclusion of Neidig (1989) that white-light continuum occurs in essentially all flares.” Subsequently—based on observations of many flares with the Variability of Solar Irradiance and Gravity Oscillations (VIRGO: Fröhlich et al. 1995) experiment on the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO; Domingo et al. 1995)—Kretzschmar (2011) estimated that white-light emission might typically account for ~ 70% of the total radiated flare energy, following an earlier estimate by Neidig (1989) of ≲ 90% based on analysis of the 24 April 1981 white-light flare (Neidig 1983).

White-light flares are of particular importance in studies of extreme flares on Sun-like stars because of the observations of such flares by the high-precision (better than 0.01% for moderately bright stars) visible wavelength (i.e., white-light, 4000–9000 Å) photometer on the Kepler spacecraft (Koch et al. 2010), which operated from 2009 to 2018. The durations of stellar white-light flares can exceed several hours (Maehara et al. 2012) versus typical durations of ≲ 10 min (Neidig and Cliver 1983a) for their largest solar counterparts, although some of this discrepancy may be due to the lower sensitivity of early WLF observations (see Fig. 13 below). Stellar flares detected by Kepler have bolometric energies exceeding 1033 erg (Maehara et al. 2012; Shibayama et al. 2013), exceeding those of the largest solar flares (~ 4 × 1032 erg; Emslie et al. 2012; cf. Kane et al. 2005) by about a factor of three. Whereas the Kepler photometer detects essentially all superflares with amplitudes > 1% of the average stellar flux on solar-type (G-type dwarfs, 5100 K < Teff < 6000 K and log g > 4.0) stars, corresponding to a flare bolometric energy of ~ 5 × 1034 erg (Shibayama et al. 2013), the estimated detection completeness for ~ 1034 and 1033 erg flares are ~ 0.1 and 0.001, respectively (Maehara et al. 2012).

It is well-accepted that the paradigm of the solar flare also holds also for the large (1034–35 erg) stellar flares (Gershberg 2005). In the standard picture of solar flares, a rapid conversion occurs, via magnetic reconnection, of energy stored in the magnetic field to energies distributed over bulk kinetic energy and thermal and non-thermal particle distributions. A significant fraction of this converted energy is eventually released as a pulse in the visible radiation, the observable diagnostic of the Kepler superflares on Sun-like stars. Like solar flares, stellar flares: (1) occur on single “solar-type” stars, viz., G-type main sequence stars with Teff and gravity similar to that of the Sun and rotation periods > 10 days and without hot Jupiters (Maehara et al. 2012; Shibayama et al. 2013; Okamoto et al. 2021; Sect. 3.2.2); (2) show evidence of non-thermal particle populations and of temperatures ≳ 107 K (e.g., Osten et al. 2007; Benz and Güdel 2010); (3) exhibit a characteristic fast rise and slower, near-exponential, decay in X-rays (Kahler et al. 1982; Haisch et al. 1983); and (4) have lower-energy emissions that often scale with the time integral of their high-energy emissions (equivalent to the Neupert effect for solar flares; Hawley et al. 1995; Güdel 2002; Osten et al. 2004; see Sect. 3.1.4). The above evidence for the commonality of stellar flare characteristics and processes with those that occur during smaller solar flares implies that the statistics of energetic flares on a multitude of Sun-like stars (see Sect. 3.2) can provide information on extreme solar flares that may occur only once per millennium or even less frequently (Notsu et al. 2019; Okamoto et al. 2021).

3.1.4 Impulsive and gradual phases of flares: The Neupert effect

The separation of flare emission into a fast-rise impulsive phase followed by a slowly decaying gradual phase has long been noted in multiple wavelengths (Fletcher et al. 2011). The impulsive phase of flares (Dennis and Schwartz 1989; Benz 2017), characterized by non-thermal hard X-ray and radio bursts, marks the time of the early principal energy release in a flare. See Fletcher et al. (2011) and Benz (2017) for detailed reviews of flare observations.

In a prescient six-page paper based on early flare soft X-ray data for three flares, Neupert (1968) found that the integral of impulsive phase microwave emission in each flare resembled the rise of the SXR light curve. He hypothesized that collisional losses by the energetic electrons responsible for the microwave burst heated the chromosphere to sufficient temperatures to eject plasma into the low corona where its cooling was manifested by the slow decay of thermal SXR emission during the flare gradual phase.

The support structure for Neupert’s conjecture on the conversion of non-thermal energy to thermal energy in a solar flare lay in the future. It consisted of: the thick target model of hard X-ray emission (Brown 1971; Kane and Donnelly 1971), the CSHKP model for eruptive solar flares (Carmichael 1964; Sturrock 1968; Hirayama 1974; Kopp and Pneuman 1976; Hudson 2021), and the establishment of chromospheric evaporation (Antonucci et al. 1984; Fisher et al. 1985). In addition, evidence that white light emission is powered by energetic electrons accelerated during the flare impulsive phase accumulated (Hudson 1972; Machado and Rust 1974; Rust and Hegwer 1975; Neidig 1989; Hudson et al. 1992; Neidig and Kane, 1993). Figure 9 (taken from Hayes et al. 2016) shows the inverse aspect of the Neupert effect—hard X-ray emission is the derivative of the SXR time profile (Dennis and Zarro 1993)—using modern data.

Image reproduced with permission from Hayes et al. (2016), copyright by AAS

Illustration of the Neupert (1968) effect in which the time derivative of flare soft X-ray (1–8 Å) emission during the impulsive phase of a flare mimics the flare hard X-ray time profile (Dennis and Zarro 1993). (Top panel) Normalized light curves for different wavelengths/radio frequencies/energies for a flare on 28 October 2013 flare. (Bottom panel) Normalized derivatives of the four SXR channels in the top panel. The red vertical lines bracket the flare impulsive phase.

Figure 10 shows a CSHKP schematic for an eruptive flare that illustrates various elements of the Neupert effect: acceleration of electrons and protons at a neutral current sheet, propagation of electrons to the low atmosphere giving rise to hard X-ray and microwave emission and heating of the chromosphere via particle bombardment, evaporation of the heated plasma to fill SXR emitting loops, and subsequent retraction and cooling of these loops as manifested by the appearance of post-flare Hα loops (Švestka et al. 1987).

CSHKP schematic showing the global structure of an eruptive solar flare and the major energy conversion via reconnection viewed in cross section along the magnetic neutral line. Adapted from Martens and Kuin (1989); with input from Anzer and Pneuman (1982), Howard et al. (2017), and Veronig et al. (2018)

According to the Neupert effect, the impulsive phase of flares can be interpreted as the time interval during which magnetic reconnection occurs. In the two-dimensional schematic in Fig. 10, this phase would end when the last closed loop of the CME is disconnected from the pinched off lower loop system. In theory, the SXR intensity at this time would be at it or near its maximum. In reality, Veronig et al. (2002b) found that this coincidence or near-coincidence of the end of the impulsive phase with SXR maximum was observed for only about 50% of their sample of ~ 1100 C2-X4 flares. In ~ 25% of the cases, the SXR emission peak occurred after the impulsive phase hard X-ray emission, and another ~ 25% of cases were unclear. For a much smaller subset of 66 large impulsive hard X-ray flares, Dennis and Zarro (1993) found that 80% of the events were consistent with the Neupert effect, suggesting that a relationship between SXR emission and white light emission can be valid for extreme events.

The significance of the Neupert effect for this review is two-fold: (1) it provides a link between the widely used (and more readily available) SXR intensity as a measure of flare size and the physically more significant measure of flare white-light energy which dominates the radiative energy budget of flares; and (2) as will be seen in Sect. 3.2, it allows flares on Sun-like stars to be directly compared with solar flares in terms of the standard CMX SXR classification.

The classic Neupert effect suggests that magnetic reconnection, particle acceleration, and post-flare loop formation, are confined to the flare impulsive phase, a useful generalization. Subsequently, Zhang et al. (2001) demonstrated that the SXR rise phase corresponded to the interval of CME acceleration. That said, magnetic reconnection, particle acceleration, and loop formation can continue for up to ≳ 10 h (e.g., Bruzek 1964; Kahler 1977; Akimov et al. 1996; Gallagher et al. 2002; Tripathi et al. 2004), well beyond the impulsive phase, as can particle acceleration by CME-driven shocks. Moreover, these late phase phenomena can give rise to strong, and even extreme (e.g., Frost and Dennis 1971; Chupp et al. 1987; Gary 2008; Hudson 2018) solar phenomena. Time profiles of flare emission at various frequencies/energies are given in Fig. 11. The hard and soft X-ray traces during the impulsive phase in panels (b) and (c) display the classic Neupert effect, which applies for the majority of flares, particularly the smaller confined events, but also for eruptive events with late phase reconnection too weak (or too high in the corona) to significantly affect the SXR time profile in panel (c)—consistent with the radiative energy domination of the impulsive phase. As shown in panels (b), (d), and (e), and discussed in Sect. 4, electrons accelerated in certain of these eruptive events can result in gradual hard X-ray and microwave bursts as well as intense decimetric bursts at ~ 1 GHz, with peak flux densities as large as 105–106 solar flux units.

Schematic of time profiles of flare emissions at various wavelengths and energy ranges. The meter wavelength range (m–λ; 30–300 MHz in panel a) exhibits various spectral types of which fast drift type III bursts are a characteristic emission of the impulsive phase and slow-drift type II bursts are the defining emission of the second phase of fully developed radio events (McLean and Labrum 1985). The various time profiles shown have been simplified to emphasize the separation of the delayed non-thermal emissions both from the impulsive phase and from each other. The delayed electron-generated emissions in panels b, d, and e are attributed to late-phase reconnection in post flare loop systems while the delayed > 100 MeV γ-ray emission in panel f is attributed to shock-accelerated high-energy protons that precipitate to the photosphere. These extended phase emissions have little effect on the flare SXR time profile (panel c)

Late phase particle acceleration in eruptive flares can also manifest itself in remotely-sensed high-energy solar γ-ray emission. When first observed in the 1980s and early 1990s, prolonged 100 MeV γ-ray emission, attributed to the decay of neutral pions which require acceleration of protons to ≳ 300 MeV energies—the highest that can be inferred from γ-ray observations—for their production, contrasted sharply with the Neupert effect in which flare energy degrades over time from non-thermal X-ray and radio emissions to thermal soft X-rays. Rather than flare electromagnetic emission becoming progressively less energetic after the impulsive phase, 100 MeV γ-ray emission characteristically occurs during the late phase of flares (Share et al. 2018). The most economical (Occam’s razor) explanation for acceleration of the energetic protons responsible for such emission is that they are accelerated by the same coronal shocks (manifested by the slow-drift metric type II burst in panel (a)) that give rise to the solar energetic particles detected by spacecraft near Earth (Sect. 7).

3.1.5 Energetics of flares and CMEs

1−8 Å soft X-ray and broad-band visible light emissions are but two of the channels into which the processes related to solar flares deposit energy. Magnetic energy is converted not only into photon emission in other channels, but also into kinetic energy of non-thermal particle populations, and the bulk kinetic energy associated with the motion of material ejected from the flaring active region. Specific electromagnetic, plasma, and particle aspects of solar eruptions will be considered in following sections of this review.

Figure 12 (taken from Emslie et al. 2012) shows the various pathways by which energy is converted and released during eruptive solar flares. Emslie et al. analyzed wide-ranging data for a sample of 38 M- and, mostly, X-class flares. Figure 12 summarizes their findings for six well-studied X-class flares. All of the listed phenomena in the figure derive their energy ultimately from the free (or excess) magnetic energy of an active region (Efm), defined to be the non-potential energy beyond (or in excess of) that obtained from a potential field model. Emslie et al. (2012) estimated that, on average, the amount of Efm of an active region was equal to 30% of the modelled potential energy determined from line-of-sight magnetograms. For the six events upon which Fig. 12 is based, with an average flare magnitude of X6, the median Efm was ~ 15 × 1032 erg. Emslie et al. estimated that ~ 30% of the free energy in an active region was released in an eruptive event. This, in turn, implies that the energy released in large flares amounts to ~ 10% of the magnetic energy in an active region (see also Shibata et al. 2013). Thus, it is not surprising that magnetic field changes between before and after a flare are hard to spot unambiguously in the overall, always-evolving, multi-thermal coronal configuration. In contrast, rapid changes associated with flares are detected in the photospheric field, most readily in association with SXR flares of class M or X (e.g., Wang et al. 2002; Liu et al. 2005; Sudol and Harvey 2005; Castellanos Durán et al. 2018). The search for such changes was lengthy, however, beginning with Carrington (1859) who looked unsuccessfully following the 1 September 1859 flare (Fig. 1) for any changes in the sunspot group based on the sketch he had made prior to the flare.

Image reproduced with permission from Emslie et al. (2012), copyright by AAS

Bar chart showing the free magnetic energy (denoted by the bottom bar) contained in various energy sinks (with their standard deviations in logarithmic values) for six major eruptive flares (X2.5, X3.0, X3.8, X7.1, X8.3, X10; averaging to X5.8). “Magnetic energy” is the assumed free energy, taken to be 30% of the estimated energy in a potential field over the active region based on observed line-of-sight magnetograms. Energy release is dominated by CMEs and flare electromagnetic radiation.

In keeping with the increased emphasis on CMEs versus flares per se for space weather during the last ~ 25 years, Emslie et al. (2012) find that, on average—for the two dominant terms of energy release (Fig. 12)—CME energy (kinetic plus gravitational potential) is ~ 3 times larger than the flare bolometric energy. Aschwanden et al. (2017) performed an analogous analysis to that of Emslie et al. (2012) for a sample of 157 M- and X-class eruptive flares observed from 2002–2006 and found that the ratio of CME to bolometric energy was ~ 1:1 versus ~ 3:1 determined by Emslie et al. (2012). These different samples preclude a straightforward direct comparison. X-class flares constituted 76% of the Emslie et al. (2012) sample with a median of X2 versus < 10% of that for Aschwanden et al. (2017; median < M2). As this review focuses on the largest, most energetic events, we use the Emslie et al. result.

This ~ 3:1 ratio CME to flare energy obtained by Emslie et al. is presumably an underestimate because the magnetic energy of the CME (Webb et al. 1980) is not taken into account in the determination. In addition, the CME masses and speeds in the SOHO Large Angle Spectroscopic Coronagraph (LASCO; Brueckner et al. 1995) CME data base (https://cdaw.gsfc.nasa.gov/CME_list/; Yashiro et al. 2004; Gopalswamy et al. 2009) used by Emslie et al. are underestimated because of projection effects (Vourlidas et al. 2002, 2010; Vršnak et al. 2007; Paouris et al. 2021). Emslie et al. (2012) write that the mass is underestimated by about a factor of two for CMEs that are associated with flares ≲ 40° from the limb—approximately half of their sample—with greater underestimates for those closer to disk center. Vršnak et al. find that average velocities of non-halo limb-CMEs are 1.5–2 times higher than for such CMEs originating near disk center. This underestimation of CME parameters impacts estimates of the largest possible solar flare (Sect. 3.1.7) that are based on active region energy and flare energy released by reducing the radiative energy budget. For a plausible 9:1 apportionment (vs. 3:1), only 10% of the released energy would go into the flare.

In reference to extreme solar flares, we can safely conclude that they are eruptive. Schrijver (2009) reviewed studies on flares with and without CMEs, including Andrews (2003), Yashiro et al. (2005), and Wang and Zhang (2007), that showed whereas ~ 20% of low to mid C-class flares have associated CMEs, ~ 90% of X-class flares are eruptive. The largest reported flares that lacked CMEs were an X3.1 flare on 24 October 2014 from NOAA spot group 12192 that produced several confined X-class flares (e.g., Thalmann et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2016; Green et al. 2018; Gopalswamy 2018), an X3.6 flare on 16 July 2004 (Wang and Zhang 2007), and an X4.0 flare on 9 March 1989 (Feynman and Hundhausen (1994). For flares on active stars, it has been argued (Drake et al. 2016; Alvarado-Gómez et al. 2018; Moschou et al. 2019; Li et al. 2020, 2021) that much stronger magnetic fields than observed on the Sun would not allow free energy to be released via eruption below some threshold. Based on observations of solar CMEs, Li et al. (2021) speculate that for an active region with unsigned flux of 1024 Mx on a solar- type star, the CME association rate for X100 flares would be < 50%. To date, the most intense solar flares yet inferred (viz., 1 September 1859 and 774 AD (Sect. 7.8)) are eruptive by virtue of their terrestrial effects—geomagnetic storm and proton event, respectively—which both imply CME association (Kahler 1992; Gosling 1993).

3.1.6 Empirical relationship between flare total solar irradiance and SXR class

Even though most of the solar flare electromagnetic radiation, or bolometric output, occurs in the visible range, the contrast with the quiescent photosphere is low. Only the larger white-light flares stand out clearly against the photospheric background in high-resolution images while only the most extreme flares such as 28 October or 4 November 2003 can be recognized as spikes in the record of total solar irradiance (TSI; Woods et al. 2004, 2006; Kretzschmar 2011). As shown in Fig. 13 (from Kopp 2016), the X17 flare on 28 October in the Halloween sequence in 2003 reached a peak brightness in the visible wavelength range of only 0.028% of TSI.

Image reproduced with permission from Kopp (2016), copyright by the author

Comparison of the total solar irradiance (TSI) signal from the X17 flare on 28 October 2003 with a bolometric energy of 3.6 × 1032 erg, and the corresponding scaled GOES 1−8 Å signal.

However, when averaging observations over multiple flares, the signal-to-noise ratio increases. Kretzschmar et al. (2010) and Kretzschmar (2011) used this ensemble technique in a superposed-epoch analysis of observations made with the VIRGO experiment on SOHO to correlate the GOES measured soft X-ray energy (\(\mathcal{F}\) GOES) and bolometric energy of over 2100 solar flares (with GOES classes from C4 up to X17) over an 11-year period. Kretzschmar (2011) presented his results averaged over fairly wide energy ranges in order to have sufficient signal-to-noise. In their analysis of solar and stellar flares, Schrijver et al. (2012) fitted a power-law relationship to these SOHO and GOES measurements to obtain

for the conversion from 1 to 8 Å GOES radiated energy to bolometric energy (both expressed in erg) based on flares with bolometric energies ranging from 3.6 × 1030 erg to 5.9 × 1031 erg. The GOES 1−8 Å channel, commonly used to characterize flares and their frequency distribution, captures < 2% of the total radiation emitted by large flares (Woods et al. 2006; Kretzschmar 2011; Emslie et al. 2012).

To go from soft X-ray radiated energy to peak brightness (which sets the GOES flare class) we can use observations of the almost 50,000 flares that were analyzed by Veronig et al. (2002a). They find that the GOES 1−8 Å radiated energy,

with their SXR fluence measurement converted to energy by multiplying by 4π × (1 AU)2 and peak SXR flux scaled to equal unity for an X1 class flare (10−4 W m−2), where 1 AU = 1 astronomical unit (1.5 × 108 km).

Combining Eqs. (3) and (4) leads to a relationship between total radiated energy, \({\mathcal{F}}_{{{\text{TSI}}}}\) (in erg), and the scaled GOES flare class:

Thus values of 1032 (1033) erg correspond to a ~ X5 (~ X115) flare, with uncertainties in the mean relationships as well as flare-to-flare differences resulting in overall uncertainties of easily half an order of magnitude (e.g., Emslie et al. 2012; Benz 2017; Gopalswamy 2018). Because TSI is dominated by white-light emission in the impulsive phase of flares, Eq. (5) can be considered a corollary of the Neupert effect.

3.1.7 Estimates of the largest possible solar flare based on the largest observed sunspot group

(a) Estimates based on reconnection flux

Large flares require large active regions with substantial amounts of magnetic flux near a high-gradient polarity separation line (Schrijver 2007). As noted in Sect. 2.1, the largest sunspot group recorded since systematic area measurements began at RGO in 1874 (Greenwich group 14886) occurred on 8 April 1947 (Fig. 14), with a corrected total spot area of 6132 μsh. Estimates of the total unsigned magnetic flux of such an active region range from 2 to 6 × 1023 Mx (Toriumi et al. 2017; Schrijver et al. 2012). Figure 15 (adapted from Toriumi et al.) shows a plot of unsigned magnetic flux (from spots and plage) for active regions associated with 51 flares located within 45° of solar central meridian from 2011–2015 (black diamonds). The red circle data points with fitted dashed line are based on unsigned flux values from Kazachenko et al. (2017). Linear fits to both data sets give a value of ~ 2 × 1023 Mx for the April 1947 spot group. At the same time, the largest spot groups in this figure (all but one from spot group 12192 in October 2014) hint at a non-linear fit line in the log–log plot that could reach the 6 × 1023 Mx value used by Tschernitz et al. The large black circle in Fig. 15 represents a compromise average flux value of 4 × 1023 Mx.

Image reproduced with permission from Aulanier et al. (2013), copyright by ESO

The largest sunspot group reported since 1874, as observed on 5 April 1947 in Ca II K1v (left) and Hα (right) by the Meudon spectroheliograph. The largest area of this group (Greenwich 14886), as reported by the Royal Greenwich Observatory (RGO) was 6132 μsh on 8 April.

Scatter plot of total unsigned active region (AR) magnetic flux versus sunspot area (black diamonds) for 51 ≥ M5.0 flares (from 29 active regions) located within 45° of disk center from 2011 to 2015 (Toriumi et al. 2017). The location of the black circle point for the April 1947 spot group (Greenwich 14886) is based on an average of the estimated total unsigned flux from Schrijver et al. (2012; 6 × 1023 Mx) and Toriumi et al. (2017; 2 × 1023 Mx). The black straight line is the result of a linear fit to data in the log–log plot. The red circle data points with fitted dashed line are based on the unsigned flux values for these events from Kazachenko et al. (2017). Adapted from Toriumi et al. (2017)

The Schrijver et al. estimate of ~ 6 × 1023 Mx assumes a uniform field strength of ~ 3000 G for the spotted area of group. While ~ 3000 G is not unreasonable for the peak field strength of a large single spot, such a value is reached < 10% of the time in sunspot umbrae (Pevtsov et al. 2014). Moreover, the corrected umbral area of Greenwich 14886, is only 739 μsh. Schrijver et al. (2012) used an overall sunspot group area of 6000 μsh but did not consider plage. This neglect of the plage contribution offsets the assumption of the high uniform field strength in the sunspots.

Cycle18 (1944–1954), which included the great spot group of April 1947 is known as the cycle of “giant” sunspots (Dodson et al. 1974). The five spot groups since 1874 with observed areas > 4500 μsh all occurred in this cycle. (The next largest group, with an area of 3716 μsh, occurred in January 1926.) While large spot areas are indicative of the potential for extreme events, they are not sufficient for their occurrence. Of these five spot groups, two (February 1946 (− 220 nT; http://dcx.oulu.fi/dldatadefinite.php) and July 1946 (− 268 nT) were associated with “great”, but not “outstanding” magnetic storms, the designation given the May 1921 event (Jones 1955). As we shall see in Sects. 6 and 7, the intensities of geomagnetic storms and solar energetic proton events, respectively, can be affected by other factors than the size of the parent sunspot group.

Tschernitz et al. (2018) find a strong correlation between the GOES class of a flare and the rate of magnetic reconnection for a sample of 51 flares (SXR class B3-X17). They estimate the reconnection rate by mapping the Hα ribbon evolution in time onto the region’s magnetogram (Fig. 16a). Among the most pronounced correlations (r = 0.92) they find a scaling between GOES SXR class and the total reconnected flux \({\Phi }_{\mathrm{r}}\) (in Mx; 1 Mx = 10−8 Wb) (Fig. 16b). Tschernitz et al. (2018) find that the largest events involve about half of the magnetic flux contained in the active region. For the April 1947 spot group with a total magnetic flux of 6 × 1023 Mx (after Schrijver et al. 2012), Tschernitz et al. inferred a largest possible SXR flare of class ~ X500 (with confidence bounds from X200-X1000) as shown in Fig. 16b, with a corresponding bolometric energy of ~ 3 × 1033 erg. However, because the correlation of Tschernitz et al. used the average of the positive and negative magnetic flux rather than the total unsigned flux as estimated by Schrijver et al. (2012), the reconnection flux for the 1947 region should be reduced by another factor of two from 3.0 × 1023 Mx to 1.5 × 1023 Mx (A. Veronig, personal communication, 2021), reducing the SXR class estimate to X180 (− 100, + 300) (1.4 (− 0.6, + 1.4) × 1033 erg) via Eq. (5). For the compromise total (average) unsigned flux of 4(2) × 1023 Mx for the April 1947 active region in Fig. 15 (with 50% flux involvement), Fig. 16b yields a SXR class of X80 (− 40, + 120) (with bolometric energy of 0.8 (− 0.3, + 0.7) × 1033 erg). For reasons given in 3.1.7(c) below, our preferred estimate based on Fig. 16b is the X180(− 100, + 300) value for an unsigned flux of 6 × 1023 Mx. Figure 17 gives an impression of the areas of sunspot groups that appear to be required to power flares of different magnitudes. The inset shows the large 1947 active region for comparison with a modelled spot group in the upper right of the figure that, based on the above calculation, could produce a 1033 erg flare.

Image reproduced with permission from Tschernitz et al. (2018), copyright by AAS

a Determination of reconnection flux φ for an eruptive M1.1 flare on 2011 November 9. The cumulated pixels swept over by the flare ribbons are superimposed on the HMI line of sight magnetogram (scaled to ± 500 G). Red (blue) areas indicate negative (positive) magnetic polarity. b Total flare reconnection flux \({\Phi }_{\mathrm{r}}\) (defined as the mean of the absolute values of the reconnection fluxes in both polarity regions) versus GOES 1–8 Å SXR peak flux FSXR. Blue squares indicate confined events, and red triangles indicate eruptive events. The linear regression line derived in log–log space for all events (thick line) is plotted along with the 95% confidence intervals (thin lines).

A cartoon depicting estimated areas of sunspot groups (exclusive of any surrounding facular areas) needed to power flares with different energy budgets. These estimates were originally developed by, and depicted in, Aulanier et al. (2013) for the parts of the sunspot groups involved in the flaring, which is assumed to be up to a third of the overall group size. In this modified version, Schmieder (2018) tripled the areas of the groups for the bipole involved in flaring (with red outlines) to show the sizes of spot groups required to reach up to a maximum value of a large stellar flare of around 1036 erg. In the Sun and stars, the flux in two thirds of the region may not be fully contained in spots, of course, but could also be distributed over extended facular regions. In a modification of the figure from Schmieder (2018), we overlaid, in the solar image on the left, the largest observed sunspot group since 1874 (shown in Ca II K1v; full disk image in Fig. 14) for comparison with the group in the upper right quadrant which has an estimated peak flare energy of 1033 erg. The two symbols in the right-hand image that resemble tires are sunspot drawings of uncertain scale by John of Worcester from 1128 AD December 8 (https://sunearthday.nasa.gov/2006/locations/firstdrawing.php)

Kazachenko et al. (2017) performed a similar study to that of Tschernitz et al. based on over 3000 flare events (C1.0-X5.4) by measuring the ribbons observed in the 1600 Å channel of SDO/AIA (Atmospheric Imaging Assembly; Lemen et al. 2012) instead of Hα spectroheliograms, and mapping these to SDO/HMI magnetograms. They find

Equation (6) was derived as a linear reduced major axis fit to logarithmic variables (Isobe et al. 1990). The slope of 0.58 derived by Tschernitz et al. (2018) for the fit line in Fig. 16b and that of Kazachenko et al. in Eq. (6) are statistically consistent. Toriumi et al. (2017) obtain a slope of 0.28 ± 0.10 for a sample of 51 events but for a small (M5.0-X5.4) range. For an active region with total unsigned flux of 4 × 1023 Mx and 50% flux involvement, Eq. (6) yields an ~ X55 SXR flare with radiative energy of ~ 6 × 1032 erg from Eq. (5), comparable to the ~ X45 and 5 × 1032 erg values inferred for the 1 September 1859 event.

(b) Estimates based on active region energy and released flare energy

As noted in Sect. 3.1.5, solar flares and eruptions are powered by some fraction of the excess or free (i.e., non-potential) magnetic energy (Efm) of an active region. Efm is distributed throughout the magnetic field of an active region. Sometimes, authors define a “free energy density” as if that would provide information on where the primary contributions to free energy would be located. However, despite the fact that the difference of the integral of the field energy for non-potential and potential fields can be mathematically written as the integral over the difference of what looks like a local quantity, namely

this should not be interpreted to mean that the physical quantity of the resulting integrand maps to, say, the electrical currents that most contribute to the free energy. Efm is intrinsically a large-scale quantity.

Estimation of Efm is complicated by the facts that we cannot directly measure the coronal magnetic field and that models of that field based on the measurements of polarized photospheric light are, at best, uncertain at present. Nevertheless, as summarized by Emslie et al. (2012): “Numerous efforts have been undertaken to estimate nonpotential magnetic energies in active regions near disk center. The methods include: (1) using the magnetic virial theorem estimates from chromospheric vector magnetograms (Metcalf et al. 1995, 2005), (2) semi-empirical flux-rope modelling using Hα and EUV images with MDI LOS magnetograms (Bobra et al. 2008), and (3) MHD modelling (Metcalf et al. 1995; Jiao et al. 1997) and non-potential field extrapolation based upon photospheric vector magnetograms (Guo et al. 2008; Schrijver et al. 2008; Thalmann and Wiegelmann 2008; Thalmann et al. 2008). These methods are labor intensive, and uncertainties in their energy estimates are large. For example, error bars on virial free-energy estimates can exceed the potential magnetic energy. Also, there is considerable scatter in estimates from studies that employ several methods to analyze the same data (e.g., Schrijver et al. 2008). A couple of generalizations, however, can be made. Free energies determined by virial methods matched or exceeded the potential field energy, while free energies estimated using other techniques typically amounted to a few tens of percent of the potential field energy. Published values for free energies in analytic (Schrijver et al. 2006) and semi-empirical (Metcalf et al. 2008) fields meant to model solar fields also hover around a few tens of percent of the potential field energy.” Thus, as noted above, Emslie et al. (2012) adopted 30% of the modelled potential energy of an active region as their estimate of the free energy available for eruptive flares.

It may well be that a value of ~ 30% of the total magnetic energy of an active region represents a maximum value of the free energy beyond which active-region coronal fields cannot be stable. A model example of this can be found in the magnetohydrodynamic experiment performed by Aulanier et al. (2010, 2012) and analyzed in light of extreme flaring by Aulanier et al. (2013). In their bipolar region, one polarity is subjected to a rotational shear, which builds up until an instability in the field develops, manifested in the eruption of a flux rope mimicking a CME. Aulanier et al. (2013) note that the “CME itself was triggered by the ideal loss-of-equilibrium of a weakly twisted coronal flux rope …, corresponding to the torus instability (Kliem & Török 2006; Démoulin and Aulanier 2010)”. During the eruption, the field above their modelled bipolar region released 19% of the total magnetic energy, with most of that energy available for the thermal evolution of the corona (i.e., a flare) and the remaining 5% going into the bulk kinetic energy of the CME. While the fraction of total energy released in this numerical experiment approaches 30%, the ~ 20:1 apportionment between flare and CME is opposite to that of Emslie et al. (2012).

Aulanier et al. (2013) obtained relationships between active region length scale, typical field strength, flux, and energy content. Reformulation of their results yields the following scaling between the total energy E(AR) (erg) contained in the active region magnetic field, the region’s total unsigned flux \(\Phi \) (Mx), and the core field strength of the simulated spot pair, BC (Mx cm−2):

This equation permits an independent determination of the largest possible flare from that determined in Sect. 3.1.7(a). With the scaling of Eq. (8), a maximum field strength of BC = 3.5 kG (Aulanier et al. 2013) and an active region flux of Φmax = 4 × 1023 Mx yields a total active region energy E of 6.6 × 1034 erg. Apportioning per Sect. 3.1.5, the released energy (approximately one-tenth of active region magnetic potential energy) is 6.6 × 1033 erg, with bolometric energy (~ one-fourth of released energy) of ~ 1.7 × 1033 erg and a SXR class of ~ 240 via Eq. (5)Footnote 6.

In another estimate of this type, Toriumi et al. (2017) calculated the total energy released in a flare based on the integral of the flux contained in the flare ribbons over time. For an estimated total magnetic flux of 2 × 1023 Mx for the April 1947 active region (Fig. 15) and under the assumptions that the ratio of ribbon area to spot area was 0.85 and that two-thirds of the computed energy would be released in a flare, they obtained a released energy of ~ 1 × 1034 erg, which after Emslie et al. (2012) would translate to a bolometric energy ~ 2.5 × 1033 erg, and a ~ X410 SXR flare from Eq. (5).

The likely underestimation of CME energies noted in Sect. 3.1.5 will reduce the SXR class estimates based on the work of Aulanier et al. (2013) and Toriumi et al. (2017). Assuming a 6:1 (vs. 3:1) apportionment of released free energy between CMEs and flares, respectively, results in a SXR class estimate of X105 (X185) for Aulanier et al. (Toriumi et al.).

(c) Composite estimate

Altogether, the above estimates have a surprisingly low range of values, all lying within the X80 (− 40, + 120) range for the estimate from Fig. 16b, based on a total unsigned flux of 4 × 1023 Mx from Fig. 15. The lower limit SXR class and radiative energy estimates of Kazachenko et al. (X55; 6 × 1032 erg) and Tschernitz et al. (X40; 5 × 1032 erg) are comparable to the parameters for the 1 September 1859 and 4 November 2003 flares, which originated in spot groups less than half as large as April 1947. Because of this and the apparent upward curvature of magnetic flux with increasing group spot area in Fig. 15, we adopt: (1) the reconnection flux based estimate of X180 (− 100, + 300) given by Fig. 16b from Tschernitz et al. as our preferred estimate of the largest possible flare, and (2) the total unsigned flux value of 6 × 1023 Mx they used as the best estimate of the unsigned flux for the April 1947 active region. An unsigned flux of 6 × 1023 Mx would increase the SXR flare class (radiative energy) estimate of Kazachenko et al. to X105 (9.4 × 1032 erg), and those of Aulanier et al. and Toriumi et al. to ~ X240 (1.7 × 1033 erg) and ~ X4000 (1.3 × 1034 erg), respectively. We reject the ~ X4000 estimate of Toriumi et al. as a clear outlier—an overestimate apparently due to assumptions regarding spot:ribbon area ratio and the fraction of the computed energy released. From Fig. 8, a 10,000-year flare would have a bolometric energy of ~ 2 × 1033 erg versus the 1.3 × 1034 erg value calculated from Eq. (5) for the ~ X4000 estimate from Toriumi et al. Nominal SXR class and energy values of X180 and 1.4 × 1033 erg are approximately five and three times as large as the respective values (~ X40; ~ 5 × 1033 erg) for the 1859 and 2003 flares. Our preferred estimate of X180 (− 100, + 300), indicated by bold/italic font in Table 1, can be considered a composite because it encompasses the ~ X105 and ~ X240 estimates of Kazachenko et al. and Aulanier et al., respectively, with all three estimates based on an unsigned magnetic flux of 6 × 1023 Mx. The lower end of the X180 (− 100, + 300) estimate for the largest possible flare based on the April 1947 active region exceeds that of the largest flares observed since 1859 (from smaller spot groups) and the upper limit encompasses the X285 (± 140) SXR class estimated for the inferred flare for the 774–775 AD SEP event (Sect. 7.8).

3.2 Flares on Sun-like stars

3.2.1 Stellar flare research before Kepler

The first generally recognized observations of stellar flares (on the faint dwarf star L 726-8; also designated UV Ceti) occurred on 25 September 1948 (Joy and Humason 1949) and 7 December 1948 (Luyten 1949a, b). Luyten (1949a) noted that Edwin Carpenter’s photographic plates, taken on 7 December with the 36-in. telescope at Steward Observatory in Tucson (Fig. 18), give “the first observation of the extreme rapidity of the [flare brightness] change—to twelve times the original luminosity [of the star] in less than 3 min …” Precursor observations of stellar flares were made by Hertzsprung in 1924 (Bastian 1990; Gershberg 2005), Luyten (1926) and Van Maanen (1940, 1945). Subsequently, radio (Lovell 1963; Slee et al. 1963a, b; Orchiston 2004) and X- ray emissions (Heise et al. 1975; Güdel 2004) were found to accompany optical stellar flares.

Image reproduced with permission from https://speccoll.library.arizona.edu/, copyright by University of Arizona

Edwin Carpenter (center) shows University of Arizona students the 36-in. telescope of the Steward Observatory in 1957. Carpenter was the first to record the rapidity with which some stellar flares can unfold.

Joy and Humason (1949) and Luyten (1949a, b) used the terms “flare-up” or “flare” when describing the stellar phenomenon but neither paper makes an analogy to solar flares. Luyten (1949b) suggested that the cause might be “the same as that which produces a nova, or an SS Cygni star.” In the preface of his monograph on solar activity in main sequence stars, Gershberg (2005) places the establishment of the similarity of solar and stellar flares in the mid-1960s, following the first high-time resolution spectra of flares on UV Ceti variables. As noted in Sect. 3.1.3, several lines of evidence support the close relationship of physical processes observed in stellar and solar flares.

3.2.2 Discovery of superflares on solar-type (vs. Sun-like) stars

X-ray observations show that young stars can have very large flares, termed “superflares” (Schaefer et al. 2000), defined as flares with radiative energy more than 1033 erg (~ 2–3 times more energetic than the largest directly observed solar flares; Emslie et al. 2012). These young stars rotate very fast with rotational periods of a few days, much less than solar sidereal rotation period of ~ 25 days at the equator. Generally, such fast rotating stars are strong X-ray sources even in their quiescent phase, indicating the presence of strong magnetic field and often with evidence that large fractions of the stellar surface are covered by starspots (Pevtsov et al. 2003). Consequently, it has been assumed that superflares would never occur on the present Sun, since the Sun is old and is slowly rotating.

However, by analyzing previously existing astronomical data, Schaefer et al. (2000) identified nine superflares with energies ~ 1033–38 erg in ordinary solar-type stars (i.e., G type main sequence stars with rotational velocities less than 10 km s−1; rotation period > 5 days). Concurrently, Rubenstein and Schaefer (2000) argued from analogy with RS CVn binary star systems that superflares on solar-type stars were caused by a “hot Jupiter” (Mayor and Queloz 1995; Marcy and Butler 1998; Schilling 1996), a Jovian-type exoplanet orbiting close-in to these stars. Rubenstein and Schaefer thus implied that—because of the lack of a hot Jupiter—the Sun is not a candidate to produce superflares. Cuntz et al. (2000) laid the framework for how a close-in giant planet could cause stellar activity via gravitational and magnetic interaction. Ip et al. (2004) used a numerical MHD simulation to show that a star-planet magnetic interconnection could lead to energy release comparable to that of a typical solar flare and Lanza (2008) explained the phase relation between stellar hot spots and planetary location in terms of such a linkage. Direct observational evidence between stars with close-in Jovian planets and superflares was lacking, however (e.g., Saar et al. 2004).

One of the authors of this review, Kazunari Shibata, questioned the hot-Jupiter hypothesis of Rubenstein and Schaefer (2000) because the RS CVn stars on which the hypothesis is based have short rotation periods due to tidal locking. Hence in 2010 Shibata started to encourage young researchers and students to search for superflares on solar-type stars (G type dwarfs) observed by Kepler. As a result, Maehara et al. (2012) reported 365 superflares (with radiative energy > 1033 erg) on 148 “solar-type” stars (defined as G-type main sequence stars with effective temperature of 5100–6000 K and log (surface gravity (cm/s2) ≥ 4.0) during 120 days of Kepler observations. For more restrictive criteria, they identified [9] superflares on 5 “Sun-like” stars in the sample with effective temperatures of 5600–6000 K and rotational periods between 11.0 d and 17.1 d (Maehara et al.; Supplementary Information). As a reflection of Shibata’s encouragement, the Nature paper reporting these results included five undergraduate researchers as co-authors (T. Shibayama, S. Notsu, Y. Notsu, T. Nagao, and S. Kusaba).

Later, Shibayama et al. (2013) extended the survey and confirmed the work of Maehara et al. by finding 1547 superflares (including those reported by Maehara et al. 2012) on 279 G-type dwarf stars during 500 days (from 2009 May to 2010 September) of Kepler observations. In all, they found 44 superflares on 19 Sun-like stars. Of these 19 Sun-like stars, three had rotational periods longer than the solar rotation period of ~ 25 days, suggesting that slowly rotating stars like the Sun could exhibit superflares.