Abstract

The aim of the study was to understand aspects of life that men and women associate with happiness and to explore the connections between these associations and well-being (measured as positive affect, negative affect and life satisfaction) in different periods of life. Participants were 785 people who were asked to list associations that came to mind on hearing the word ‘happiness’. The moderating roles of gender and period of life (adolescence/adulthood, transition/no transition) were analysed. Participants associated happiness mostly with health and relationships. Other categories included knowledge, work, material goods and freedom. Those who associated happiness with work had higher levels of positive affect. Associating happiness with relationships predicted greater life satisfaction, whereas associating it with material goods predicted lower satisfaction. Gender moderated the relationship between associations and positive affect: associating happiness with material goods decreased positive affect among men but no such effect was observed among women; associating happiness with relationships was beneficial for women but unbeneficial for men. Additionally, associations with material goods predicted lower positive affect, especially in times of transition. Associating happiness with knowledge decreased positive affect in adolescents and increased it in adults. Some ways of understanding happiness improved life satisfaction but none were related to negative affect. The relationship between concepts of happiness and positive affect is complex; some concepts are unbeneficial only for some people and during certain periods of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Lay conceptions of happiness are individual cognitive representations of the nature and experience of well-being (McMahan and Estes 2010a) and are a relatively new subject of psychological research. As stated by Delle Fave and colleagues, this is ‘one crucial topic [that] has been neglected: what do lay people refer to, when they speak about happiness?’ (Delle Fave et al. 2011, p. 187). Studies focusing on lay conceptions incorporate well-established approaches to happiness, such as eudaimonic or hedonistic perspectives (see Carr 2009; Delle Fave et al. 2011, Delle Fave et al. 2013b; Trzebinska 2008) but there remain gaps in our understanding of the impact of these lay conceptions on experienced subjective well-being. These areas require qualitative data and studies using a mixed methods approach (Delle Fave et al. 2013a).

Our study’s aim was to investigate individual conceptions of happiness held by Polish people of different ages and genders. We also wanted to explore if these conceptions are more or less beneficial for individual well-being. Our assumption was that the individual’s concepts of happiness can influence individual well-being (i.e. how happy or satisfied a person is). The literature indicates that there are indeed dimensions that can facilitate or decrease well-being (e.g. perceiving material goods as a prerequisite of happiness is unbeneficial for well-being, Kasser and Ryan 1993). However, we still do not know if these categories serve similar functions for males and females or for people at different stages of individual development.

1.1 Subjective Well-Being

Most studies of happiness and well-being are based on one of two types of measurement: (a) evaluations of general well-being that do not identify specific areas of life or (b) evaluations of well-being in specific areas of life (such as job, family or relationships) that can later be used to create an index of well-being. Studies of general happiness allow participants freedom to apply their own well-being criteria. From a phenomenological perspective, this is a valuable well-being index because individuals themselves are the best experts on their own sense of well-being (Zalewska 2003). This more phenomenological perspective, however, has its drawbacks: it ignores the criteria that people use to judge the quality of their lives. In contrast, some studies analyse areas of life chosen a priori by the researchers. This approach provides valuable information about the associations between specific areas of life and well-being but limits the subjectivity of well-being; it is the researcher, not the participant, who decides which areas are important (Torras 2008).

In our study, we aimed to build a bridge between these two approaches by including measures of general well-being (without identifying specific areas) and individual conceptions of happiness. We hoped to determine those dimensions that participants considered important to their understanding of happiness to determine what, in their opinions, constitutes happiness and to measure their individual experience of well-being. We aimed to close the gap in well-being research noted by Delle Fave et al. (2011), who identified a dearth of qualitative and exploratory research on lay conceptions of happiness, especially with bigger samples. We use Diener’s (2000) conception of subjective well-being. This consists of an affective component (positive and negative affect) and a cognitive component consisting of evaluations of one’s own life as satisfying or not (satisfaction with life). These three elements (positive affect, negative affect and satisfaction with life) are expected to correlate but they are not identical (Schimmack 2008), so we examine their correlation with lay conceptions of happiness separately.

1.2 Lay Conceptions of Happiness

In the last 2 years, researchers have aimed to establish a methodology for the study of lay conceptions of happiness. Most studies have used scales based on Western philosophical and psychological perspectives (Delle Fave et al. 2011). This is a serious limitation and more exploratory studies are needed to create a more culture-fair methodology. Research indicates that individual conceptions of happiness are to some extent universal (Pflug 2009) but that culture and society are both important in determining how people perceive happiness (Delle Fave et al. 2013b; Joshanloo 2012), suggesting that concepts of happiness are culture-specific. Analysis of happiness categories ought to take into account the particular cultural domain and data gathering should, as far as possible, be free from assumptions about the nature of happiness so that participants can freely describe their understanding of happiness. The investigation of lay conceptions of happiness is important in determining what is actually researched in studies of subjective well-being. Many inferences are made from philosophical perspectives, such as hedonic or eudaimonic conceptions (see Carr 2009; Delle Fave et al. 2011; Trzebinska 2008), and even though they are the cornerstones of our understanding of happiness a more direct approach is needed to understand what happiness means to individuals living in a given society at a particular time.

The study of lay conceptions of happiness is also valuable from a theoretical point of view as it may elucidate the relationships between various elements of well-being and establish whether it is a multifaceted concept (Delle Fave et al. 2011). For example, evidence indicates that cognitive and affective components of well-being are correlated yet separate constructs (e.g. Lucas et al. 1996). Similarly, lay conceptions may constitute yet another element of the structure of well-being. Studies of lay conceptions of happiness that also include well-being measures can indicate how separate well-being dimensions are influenced by various aspects of happiness as understood by individuals.

1.3 Lay Conceptions of Happiness and Subjective Well-Being Experience

European statistics identify the following dimensions as connected to well-being: health, relationships, freedom, work, knowledge and material goods (Eurostat 2010). The universal elements of lay conceptions of happiness are partly congruent with eudaimonic and hedonistic concepts, and the concept of happiness that an individual adopts may affect the experienced well-being (Ryan and Deci 2001). Eudaimonic beliefs are more strongly related to well-being than are hedonistic beliefs (McMahan and Estes 2010b); however, lay conceptions typically include both eudaimonic and hedonistic elements, such as mental states of satisfaction and contentment, positive emotions, achievement and control, self-autonomy, freedom from ill-being and relationships (Lu and Gilmour 2004). These refer to profound aspects of life such as health, relationships with others, work and material goods. Several studies have examined links between these areas and experienced well-being.

Relationships are one of the strongest correlates of positive emotions (Bradburn 1969); they alleviate stress (Sęk and Cieślak 2004; Uchino 2004) and their absence greatly decreases well-being (e.g. ostracism, Baumeister and Leary 1995). Bonn and Tafarodi (2013) report that people emphasize that close and enduring relationships are important to well-being. An overwhelming majority of respondents refer to social relationships as necessary for achieving happiness (Diener and Oishi 2005; Diener and Seligman 2004; for an overview see Caunt et al. 2013). Relationship quality is also important in explanations of well-being constructs (Lehmann et al. 2014).

Subjective health influences well-being and vice versa (Diener and Chan 2011) and participants frequently mention health as one of the factors vital for well-being (Argyle 1999), despite the fact that people adapt very well to new circumstances and their well-being may return to baseline levels even in the face of serious health issues (Brickman and Campbell 1971). However, the consequences of associating well-being with health are unknown. Placing great value on health and concentrating on one’s health may promote health behaviours, promoting subjective well-being through better health. However, individuals who concentrate on their health may focus on symptoms of possible illnesses; this in turn may decrease well-being. It is also possible that people value health more when they experience health problems.

Lay conceptions of happiness congruent with the eudaimonic approach include elements such as achievement, growth and competency (McMahan and Estes 2010a), all of which may be associated with the occupational realm. The relationship between work and subjective well-being is complex and includes issues such as job satisfaction (e.g. spillover effects, Judge and Watanabe 1993a, b), work-life balance, employment status or occupational stressors. In other words, work is vital for well-being and is indirectly expressed in lay conceptions of happiness. These effects suggest that placing value on professional aspects of life may facilitate greater well-being because of stronger correlations between indices of well-being and eudaimonic elements of lay conceptions of happiness (McMahan and Estes 2010a).

There is no clear relationship between individual income, income in societies (Diener and Biswas-Diener 2002) and subjective well-being, but findings from a few studies indicate that valuing material things and financial success is negatively correlated with well-being (Kasser and Ryan 1993). Moreover, financial discrepancy (the gap between what one wants and what one has) decreases well-being (Brown et al. 2009) and the relationship between the value attached to money and well-being is mediated by motives for making money; it might be important for well-being if someone wants to make money, but the more important question is what they want the money for (Srivastava et al. 2001).

1.4 The Role of Gender and Age

This paper addresses two fundamental questions about gender and well-being: (a) whether there are differences in subjective well-being between men and women and (b) whether there are differences in the impact of lay conceptions of happiness on subjective well-being among men and women. The same questions apply to age differences.

Differences in happiness of men and women are not straightforward and studies yield conflicting results. A Gallup World Poll-based study indicated that women are generally happier or as happy as men (Zweig 2014), despite the popular view that their well-being is lower than that of men. Other studies have shown that gender differences in subjective well-being in a particular society are moderated by gender inequality (Tesch-Römer et al. 2008). Moreover, women are more likely to experience higher rates of negative affect. However, data on life satisfaction and positive affect are mixed; some research suggests that women may experience higher levels of these components of well-being whereas other studies report no such differences (Fujita et al. 1991, overview in Tesch-Römer et al. 2008).

Lay conceptions of happiness need to be analysed within a particular cultural reality. As Delle Fave and colleagues state: ‘cultural, economic, and collective rules and norms can indeed expand or restrict the opportunities for action, development and flourishing available to individuals within a society’ (Delle Fave et al. 2013b, p. 228). Although Western societies, including Poland, strive for gender equality, there are still many differences in opportunities and norms between men and women. There are still differences between Poland and other European countries in the gender ideology predominant in public discourse and expressed in the law and social policy. This may influence ideas about feminine and masculine social roles and norms. These norms in turn are likely to impact and differentiate individual goals and needs.

First, differences in norms may determine individual expectations about, for example, family, career or self-development and consequently determine how individuals understand happiness. Second, they may result in some conceptions of happiness affecting the well-being of women and men differently. Men and women in Poland may have a different understanding of their roles in society that are expressed, for example, in the gender stereotypes strongly perpetuated in Polish public discourse. These cultural norms may impact the understanding of happiness through the attribution of meaning to different behaviours and activitiesFootnote 1; they may encourage women and men to ascribe different meanings to activities in specific areas (e.g. motherhood, careers) and form different goals and values. Polish studies indicate that girls in high school value relationships and the common good more than boys (Zalewska 1998). They also value conformity and caring for others more than boys, who emphasize individual achievement and autonomy (Koralewicz 1987). Community orientation (striving for cooperation associated with motives of intimacy and affiliation) is also higher among women than men, but agency orientation (striving for self-enhancement associated with motives of achievement, dominance and self-autonomy) is higher among men than women (Wojciszke 2010). All Polish studies in this area based on self-reports point to gender differences in goals.

Additionally, those conceptions that are congruent with social roles typical for one gender may be more beneficial, because they may generate less tension between the individual and his/her social surroundings.Footnote 2 This may be truer for Polish women than men, as studies indicate that, compared to men, women more often choose activities that are in line with social expectations (Zalewska 1987).

As Kroll (2011) claims, there is no unitary ‘happiness formula’; different things make different people happy and there are gender-specific elements that contribute to well-being. For example, informal socializing increases satisfaction with life among women more than among men. These elements, however, are often reported to be mediated by cultural climate, the value of traditional roles and discrimination of women in a given country (Zweig 2014), so any research claims and interpretations are somewhat limited to particular cultural domains. There is evidence for gender differences in the effects of job status on well-being (Jaros and Zalewska 2008; Trzcinski and Holst 2012); while men suffer most from unemployment and benefit from high status jobs, job status affords almost no well-being benefits for women. Men and women also tend to react differently to adverse events (Forest 1996); these events decrease satisfaction in women but affect global happiness in men. Similarly, self-esteem is a better predictor of well-being for men, whereas for women relationship harmony is a better predictor (Reid 2004).

Finally, biological conceptions may explain gender differences in well-being. Women score more highly on neuroticism and emotionality than men and numerous studies have found correlations between these dimensions and well-being (Schmitt et al. 2008). Biological conceptions may also help interpret the links between goals and happiness; different biological roles, connected to reproduction and childcare for example, may influence goals and values and in turn lead to a different understanding of happiness.

McMahan and Estes (2012, p. 80) state that: ‘Little is known… about how individual conceptions of well-being may change with age or how this construct may impact psychosocial functioning at different points in the lifespan.’ The authors provide a detailed overview of previous studies of lay conceptions of well-being and age, concluding that there are fundamental differences between younger and older adults in terms of goals (knowledge acquisition in younger groups vs. emotion regulation in older), values (terminal in older groups vs. instrumental in younger) or meaning-making after significant events (which happen more often in groups of older adults).

Psychology offers many approaches to age and individual human development; the two main schools of thought involve dialectical and stage models (e.g. Erikson 1950; Ijzendoorn et al. 1984). Our aim was to explore differences between people of different ages in a specific cultural and temporal context. We chose to use a stage model approach; this may limit the generalization of the results but may also serve as a starting point for further (longitudinal) studies on age and lay conceptions of happiness.

Stage models are based on the belief that human development happens in stages, which have certain qualitative characteristics and that individuals face specific tasks in every stage (e.g. Erikson 1950). This idea was further developed by Levinson, who described these tasks with greater emphasis on the social and cultural context (1986). He divided life into four stages/eras, each lasting about 20 years: pre-adulthood, early, middle, and late adulthood. These eras are separated by transitional periods, or turning points, when important decisions about future life need to be made. According to Levinson, these periods are especially challenging because they require people to rethink their life structure (in a similar way to Erikson’s conception of conflict resolution). Even if the chronological end points of these eras change with civilizational development and become more flexible, the general, most universal tasks and transitions are similar in many Western societies; most people move from dependence in childhood to independence in adulthood, attend schools, work, form relationships, have children and face challenges connected to getting older.

Three elements are missing from studies of age and lay conceptions of happiness. First, although differences between older and younger adults have been investigated, little is known about the role of lay conceptions in the experience of well-being. Integration of the two elements (well-being and conceptions of happiness), especially if age is treated as a moderating variable, could yield interesting results. Conceptions of well-being congruent with developmental tasks at a particular stage in life (Erikson 1950; Levinson 1986) may be more beneficial to individual well-being than conceptions that emphasize elements incongruent with opportunities available to people at a certain level of development. This claim is supported by the selective optimization and compensation model, which indicates that changes in values and goals that happen when people age may be a sign of adaptation to changing circumstances (Baltes and Baltes 1990). It is also supported by McMahan and Estes’s study (2012), which indicated that older and younger adults differ in their conceptions of happiness and that some dimensions (e.g. avoidance of negative experience and experience of pleasure) were more strongly associated with well-being for older adults.

Second, Ryff and Singer (2008) found that age differences in subjective well-being are complex. Very few studies have compared well-being in adolescents and adults but those that have, indicate that the relationship between personality and well-being is connected to life-span development (e.g. Butkovic et al. 2012). For example, data on the dynamics of neuroticism may elucidate the dynamics of well-being (Costa et al. 1986). However, little is known about adolescent concepts of happiness and their impact on the experience of well-being.

Third, studies of conceptions of well-being and their impact on experienced well-being usually measure such conceptions according to a priori categories. This method limits the participant’s freedom to choose his or her own understanding of what happiness is. Even though categories presented by researchers such as McMahan and Estes (2012) are correlated with those that people often spontaneously mention, complete reliance on spontaneous understanding of happiness may yield interesting results.

In summary, research indicates possible differences between genders and between developmental periods in lay conceptions of happiness. Moreover, the associations between these conceptions and experienced well-being may be different for women and men, and for people at different stages of their lives.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

Participants (N = 785) represented different periods of adolescence and adulthood. There were two groups of teenagers (aged 13–14: n = 183 and 17–18: n = 209) and two groups of adults (28–33: n = 208 and 40–45: n = 197). One group from each age period represented a time of transition; those aged 17–18 were experiencing the end of obligatory education and those aged 40–45 experiencing the mid-life period. The two adolescent groups were still dependent, living with parents and going to school; the adult groups enjoyed the full range of legal and civic rights reserved for adults and were (at least partly) financially independent (all adult participants had jobs). The 13–14-year-olds (adolescence, no transition) attended school and did not anticipate major changes in their (in)dependence. They would still be going to school and living with parents for at least another 4 years. The teenagers aged 17–18 (adolescence, transition) attended high school and were nearing the end of adolescence (age 18) and preparing to move on to the next stage of life (emerging adulthood, 18–29) (Arnett 2012). They were on the verge of leaving school and making choices for their future paths, such as choosing subjects for the ‘matura’ exam (the Polish equivalent of SATs, which determines later field of study/career), leaving home or not and moving to a different town to study (Robinson and Smith 2010). Most Polish teenagers at this point still live at home but expect their lives to change drastically in subsequent years when they move on to full adulthood or emerging adulthood (Arnett 2012). Young adults (adulthood, no transition) in their late 20s and early 30s represented early adulthood. At this age, many important life events take place but there is no evidence that this is a time of crisis. Rather, events such as marrying and having children are realizations of developmental tasks set for early adulthood (Levinson 1986). Adults aged 40–45 (adulthood, transition) represented the period of mid-life. Polish studies suggest that people experience a period of mid-life transition around 40–45 years of age and that this is a time of crisis (Oleś 1995, 2000). Census data on divorce (for which the average age is 40–41, Główny Urząd Statystyczny [GUS] 2012) suggests that this period signifies a change in life structure. The sample showed a close to even distribution of women and men (women/men: adolescents, 54/46 %; first transition, 40/60 %; young adults, 53/47 %; mid-life, 56/44 %).

2.2 Procedure

For the teenaged sample, the study was conducted in class with the teacher present. Students were assured that refusing to participate would have no negative consequences, participation was voluntary and anonymous, and individual data would not be analysed. For the adult sample, the questionnaires were distributed in the workplace (after obtaining permission from a manager or Human Resources Department) and a deadline for return was set. Participants were informed that the study was anonymous and voluntary. The questionnaires were completed within 1 week and placed in a sealed envelope to be returned.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Well-Being Indices

Positive and negative affect were measured using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (Watson et al. 1988) translated into Polish with a back-translation. The measure includes a list of 10 adjectives referring to positive (e.g. interested, excited) and 10 to negative affective states (e.g. guilty, ashamed) and respondents were asked to indicate how intensely they had experienced each state during the 2 weeks prior to the study. The scale ranges from 1 (only slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely).

Satisfaction with life was measured using the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al. 1985). Participants indicated to what extent they agreed with the statements about their lives (e.g. ‘In most ways my life is close to my ideal’) on a scale of 1 (I definitely disagree) to 7 (I definitely agree). Higher scores indicate better life satisfaction.

2.4 Understanding Happiness: The Importance of Criteria Associated with Happiness

There are various proposals about how to measure individual understanding and conceptions of happiness (e.g. free-format essays, Pflug 2009; happiness recipes, Caunt et al. 2013). We chose the associative technique (Karwoski and Berthold Jr. 1945; Ross et al. 2006; Szalay and Brent 1967) because the outcome data allow for comparisons between individual people or groups and the data can be analysed quantitatively. The simplicity of the answers is both a strength and a weakness of the method. The associations are stable so we assumed that they include stable clusters of ideas about happiness. This might be a problem for other methods; for instance, the temporal stability of essay contents is unknown. Additionally, the simplicity of the grammatical form of associations limits data reduction issues. The only operation that needs to be performed with the data is putting the words or short phrases into categories, whereas in other methods context also needs to be analysed. The drawback of the technique lies mostly in our limited understanding of what the associations denote: whether the words/phrases should be understood as values, deficits or resources.

Participants were asked to list associations that came to mind during one minute from hearing the stimulus word ‘happiness’. We first conducted a preliminary analysis choosing the six categories proposed by Eurostat (2010) as appropriate for further investigation. However, these categories are quite broad so we listed additional subcategories to facilitate the categorization of responses (Table 1). The analyses were conducted using the associative group analysis method verified in longitudinal studies, which indicated that the associations appearing closest to the stimulus word were the most stable ones. With this method, the most important and most stable categories connected to ‘happiness’ are adequately represented in the data set. The method suggests that associations should be weighted: 6 points for the first associations, 5 for the second, 4 for the third, and 3 for the fourth to seventh. In the present study, only a few participants listed more than seven associations, so only the first seven responses were taken into account. The associations were then weighted according to the points indicated by the authors of the associative group analysis method. This resulted in an index of each category’s weight for each person calculated as a proportion of the category’s weight to maximal importance. Maximal importance is the number of points a category would get if all seven associations listed by one person came from the same category. The results were then transformed so that a maximum weight would be 100 points; however, none of the categories gained more than 40 points.

We also created an additional category, ‘Symbols and synonyms of happiness’. The word ‘happiness’ in the Polish language means both ‘happiness’ and ‘luck’, so some of the associations denoted symbols from those two areas, such as a four-leaf clover, chocolate and perfume. Further analyses indicated that these mostly reflected traditional symbols of happiness in sayings or folklore, but also featured in advertisements and stereotypes. Such contents do not pertain to individual experience and some researchers have recommended treating them as non-diagnostic. For example, in Rotter’s Incomplete Sentences Blank (Rotter and Rafferty 1950), song titles, catch phrases or cultural clichés are not interpreted as indicative of individual experience and are scored as neutral. Therefore, we treated this category as one of two ‘other’ categories and did not interpret its contents.

The remaining category, ‘ambiguous’, consisted of associations placed in different categories by the judges. These could be interpreted as pertaining to individual experience but usually contained words with a double meaning, such as ‘powodzenie’ in Polish, which means success and prosperity (in terms of material well-being) or popularity with other people, or ‘zrozumienie’ in Polish, denoting comprehension (in terms of knowledge) or understanding (being understood by other people). These two associations are in fact multi-categorical; the former includes relationships and material well-being and the latter refers to knowledge and relationships.

The associations were ascribed to these categories by five competent judges; if four judges agreed in their categorization then the association stayed in its category. The remaining associations were moved to the ‘Other—Ambiguous’ category. The proportion of associations in this category was small (3.3 % of all listings) but these associations were usually further from the stimulus word ‘happiness’ so their computed weight was even smaller (see Table 1 for percentages of weights). In similar studies (Delle Fave et al. 2013b), judges discussed their categorization to reach a common opinion on contents that were initially categorized differently. In our study, however, we decided to retain the initial opinions without asking the judges to discuss their choices. We chose this procedure because the proportion of ambiguous associations was small and the words involved had double meanings, so any discussion between judges might actually have constructed a new meaning rather than identifying an existing one.

2.5 Statistical Analyses

We used SPSS Statistics 20.0 software (IBM Corp. 2011) to conduct the analyses. Regression analysis was used to examine if some conceptions of happiness were beneficial or unbeneficial for the experience of positive affect, negative affect and satisfaction (dependent variables, separate regression analysis for each). In the first step, three dichotomous variables were included: gender (1 = female, 0 = male), transition (1 = period of transition, 0 = no transition) and adulthood (1 = adulthood, 0 = adolescence). In the second step, the weights of subsequent categories of associations were entered. In the third step, pair-wise interactions between weights and each remaining predictor were entered (i.e. gender, transition, adulthood). All significance tests used the .05 level (two-sided). The interaction plots were computed using Sibley’s Utilities for examining interactions in multiple regression (2008).

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 2 shows means, standard deviations, ranges and reliabilities for the dependent variables. All measures reached sufficient reliability. Mean values for positive affect, negative affect and satisfaction are all on the positive side of the scale (above the midpoint for positive affect and satisfaction and below for negative affect). Correlations between well-being variables are significant, but not strong, suggesting that we should look for their antecedents separately (Table 3).

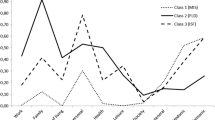

3.2 Understanding of ‘Happiness’ Among Men and Women of Different Ages

All participants associated happiness mostly with two categories: relationships and health. In comparison to these, other categories were mentioned rarely (at least four times less often). For most groups, the relationship category was most important, and health took second place, except for women in the oldest group (mid-life) for whom health was more important. The data show that happiness is understood mostly as depending on close familial, friendly or romantic relationships; these were the predominant types of associations mentioned by the participants and then ascribed to this category by judges (examples: friends, baby, husband/wife, family). The two elements of health and positive emotions were most common in the health category. Participants directly associated happiness with health; that is, they mentioned the word health in response to the word ‘happiness’ and they listed words denoting positive emotions, such as joy, smile, good mood (see Table 4).

3.3 Beneficial and Unbeneficial Categories of Associations Among People of Different Ages

The second aim of the study was to determine whether associating happiness with specific categories is beneficial or unbeneficial for well-being. Three moderating variables were included in this analysis: gender, periods of transition in life (as opposed to no transition) and adulthood (adults vs. adolescents; Table 5).

3.4 The Role of Gender, Transition and Adulthood

Male gender was associated with stronger positive affect and weaker negative affect; being a man predicted better affective well-being but gender had no association with the cognitive component of well-being. Times of transition predicted lower positive affect and lower satisfaction; during periods of transition less intense positive affect and decreased satisfaction would be expected in comparison to other periods. Being an adult (as opposed to being adolescent) had no predictive value for any of the well-being dimensions.

3.5 Beneficial and Unbeneficial Categories of Associations

Positive affect was more intense when happiness was associated with work. This was the only straightforward effect for the emotional component of well-being. There were two effects for satisfaction: importance of material goods decreased satisfaction and importance of relationships increased satisfaction.

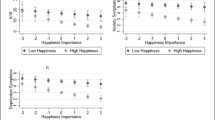

3.6 Categories, Gender and Periods of Life: Interaction Effects

Significant interaction effects were identified only for positive affectivity. No significant moderating effects were found for the two remaining components of well-being (negative affect and satisfaction). Associating happiness with material goods decreased positive affect among men, but not among women; for women this category had little effect (Fig. 1). The category of relationships was beneficial for women and unbeneficial for men; that is, understanding happiness in terms of close relationships was connected to more intense positive affect among women and to less intense positive affect among men (Fig. 2). The category of material goods was unbeneficial for all periods but the effect was stronger in times of transition. This suggests that, especially in more difficult times, understanding happiness as involving the possession or purchase of many things may decrease the intensity of positive emotions (Fig. 3). In adolescence, knowledge was an unbeneficial category; in adulthood, it was beneficial because it increased positive affect (Fig. 4).

4 Discussion

This study aimed to investigate subjective well-being in a Polish sample by examining (1) lay conceptions of happiness among men and women of different ages, (2) differences in experienced well-being between genders and between developmental periods and (3) associations between lay conceptions and experience of well-being among men and women of different ages.

4.1 Conceptions of Happiness in the Polish Sample

A vast majority of participants associated happiness with two areas: health and relationships with other people. These were the two most common categories for age and gender groups. The data are congruent with previous studies in which participants listed relationships and health as important elements of well-being (Eurostat 2010). Similar results were obtained in international studies conducted by Delle Fave et al. (2011), in which the most significant domains of happiness were family, relationships and health, or family and work (Delle Fave et al. 2013b). The data from this Polish sample are similar to those reported in other Western countries, suggesting that these categories are universal within this cultural realm. The functions of relationships have been extensively analysed by Ed Diener and colleagues (e.g. Diener and Oishi 2005) and it has been claimed that relationships with others are necessary (not only beneficial) for well-being. For example, according to self-determination theory (Ryan and Deci 2001) relatedness is a basic psychological need that allows people to feel satisfied (see also Delle Fave et al. 2011). Data suggest that the function of relationships may be twofold: they correlate with well-being and they are a causal force. The more and the better relationships we have, the better we feel, because relationships play a vital role in many aspects of human life, ranging from mere survival to everyday functioning. Moreover, changes in relationships influence well-being, as in the case of widows or divorced people (see Diener and Oishi 2005). Echoing claims made by Delle Fave et al. (2013a), these findings support theoretical assumptions about the meaning of relationships for well-being because they directly show that for lay people this is the most important category in the understanding of happiness. Although our data do not allow for inferences about the specific meaning of these associations, previous work (e.g. Delle Fave et al. 2011) indicates that participants feel that relationships affect well-being because they serve as a motive underlying goals and meaning of life.

The category ‘health’ included the experience of health itself and positive emotions. This points to the importance of freedom from ill-being (Lu and Gilmour 2004) as an element associated with being happy. It also indicates that the ability to experience positive emotions, such as joy and contentment (which point to freedom from mental ill-being), is central to concepts of happiness. Interestingly, this suggests that at an implicit level people believe that happiness is a state of physical and mental well-being that allows for full and unhindered functioning.

Relationships and health constituted a large proportion of all listed associations, with other categories rare by comparison. Nevertheless, work and material goods were also associated with happiness and, to a much lesser extent, knowledge and freedom. In conclusion, all categories identified by Eurostat as meaningful for well-being were also mentioned by Polish participants, so we managed to confirm this list in qualitative research.

4.2 Experience of Well-Being in the Polish Sample

As in other studies worldwide (Diener and Diener 1996), Polish studies indicate that Polish people are generally happy and satisfied (Jaros and Zalewska 2008). In our sample, women experienced less intense positive affect and more intense negative affect but there were no gender differences in satisfaction. However, we did not control for the social inequalities between genders that may be responsible for some of these differences (Zweig 2014). Both social and biological conceptions may be helpful in explaining these inequalities. Social conceptions emphasize that gender differences in many psychological variables are likely to stem from differences in socialization. Polish social reality is still characterized by traditional gender roles and gender inequality (e.g. expressed in lower wages for women, GUS 2012) and stereotypical approaches to femininity and masculinity are still widespread. In consequence, women may be more eager to admit to experiencing negative emotions because it is congruent with stereotypical feminine emotionality.

Biological conceptions emphasize that there are gender differences in temperamental and personality characteristics that correlate with emotional functioning; for example, emotional reactivity is higher among women and is connected to greater sensitivity to emotional stimuli, which consequently produces lower positive affect and increased negative affect (Bojanowska and Zalewska 2014; Zawadzki and Strelau 1997). There are also gender differences in neuroticism levels, which are higher among women (Costa et al. 1986), suggesting that women experience a less positive affective balance.

We suspected that transitional times, as described in Levinson’s (1986) model of human development, would be connected to a decline in well-being, because they are more challenging and may be stressful. In our sample, the only decrease we observed for transition periods pertained to positive affectivity. This suggests that transition times in our group were of moderate or mild intensity; if stress were greater, both positive and negative affect would be expected to change. We derive this claim from the dynamic model of affect (Reich and Zautra 2002), which states that positive and negative affects are most independent of one another under low stress. When stress is low, processing capacity is at its maximum and so the person is able to draw fine distinctions and process many dimensions of judgment simultaneously. This enables the person to react with changes to one type of affect but not to both (which happens with stress of greater intensity).

4.3 Beneficial and Unbeneficial Conceptions of Happiness

We found that subjective well-being was connected to lay conceptions of happiness and observed both straightforward effects and interaction effects. Satisfaction with life was lower if happiness was associated with material possessions and higher if happiness was associated with relationships. These data are congruent with studies on values and well-being (Kasser and Ryan 1993), which suggest that concentrating on external goals, such as financial success, is connected to poorer indices of well-being and confirms the positive role of relationships in subjective well-being. We suspect that people who associate happiness with relationships invest more time and effort in their relationships, which improves relationship quality and leads to greater life satisfaction.

We also showed that people who associated happiness with the work domain experienced more intense positive affect. Research indicates that personal growth and competence development are intrinsic motives underlying work goals (Delle Fave et al. 2013b), which facilitate engagement, enjoyment and the experience of flow (Csikszentmihalyi 2000). In this context, our findings are congruent with McMahan and Estes’s (2010b) suggestion that the eudaimonic elements of lay conceptions of happiness are connected to experienced well-being. Data suggest that perceiving happiness to be achieved through work promotes positive affect but, surprisingly, this is not connected to other dimensions of well-being.

Interestingly, some dimensions of the lay conceptions of happiness were not universally beneficial or unbeneficial for well-being. We observed that men who listed material goods as connected to happiness experienced less intense positive affect than those who mentioned material goods less often. This suggests that a materialistic approach is especially damaging for men but has no such effect for women. This may be because of the cultural and societal mechanisms that generate traditional gender ideology and typical gender roles in Poland.

While Poland is a Western society, traditional gender roles are still more prevalent there compared to many European countries, which means that men are viewed as breadwinners responsible for household income even if most women also have jobs (Langdon and Klomegah 2013). Previous studies indicate that men are more sensitive to job status (Jaros and Zalewska 2008, Poland; Trzcinski and Holst 2012, Germany); there are few or no differences in well-being among women with different job status (managerial, non-high level or household position) whereas among men there are differences between all groups. The two elements of material possessions and job status may be indicative of social status. Perhaps perceiving social status as a prerequisite of happiness is not beneficial for men because traditional masculinity is threatened by current cultural and social transitions; for example, by women’s increasing role in the job market and heated public discussion about traditional and liberal gender ideology.

We also found gender differences in the association of happiness with relationships. Women who mentioned relationships more experienced more intense positive affect, whereas men who emphasized relationships experienced less intense positive affect. There are a number of possible explanations for this. First, stereotypical masculine and feminine roles expressed in traditional gender ideology, in which women are considered responsible for social and emotional bonds (Langdon and Klomegah 2013), suggest that valuing relationships is desirable among women but not among men. The traditional model of masculinity does not promote sensitivity, and traditional conceptions of gender roles and differences in socialization suggest that men should be independent while women should be interdependent (Cross and Madson 1997). This is congruent with social role valorization theory (Wolfensberger 2011); attitudes congruent with predominant social roles are more beneficial because they do not induce as much stress.

Second, most theoretical approaches to gender differences consider women to be taught or predisposed to care for relationships.Footnote 3 If we accept this claim, then associating happiness with relationships may be easier for women but may prove difficult for men, creating tensions between the traditional and the liberal concept of masculinity. This explanation fits with findings from Polish samples that goals connected with relationships are more important for girls than for boys (Koralewicz 1987; Zalewska 1998) and for women more than for men (Wojciszke 2010).

This study showed that age may function to moderate the relationship between conceptions of happiness and well-being. In transitional periods, the association of happiness with material goods was especially damaging, more so than in periods of no transition. As Levinson (1986) suggests, transitional periods take place at specific points in individual development when structural changes are expected, such as moving from dependence to independence. According to Erikson (1950), these times are characterized by a necessary change in perspective. Both approaches posit some form of challenge or stress in these periods, so why should happiness not be associated with material possessions at these times? Perhaps this mechanism functions to ‘add insult to injury’ in that two converging unfavourable elements (the stress of transition and the valuing of extrinsic rewards) produce an even stronger unbeneficial effect. We suspect that only positive affect was influenced because the transitions experienced by our participants were of mild intensity (Reich and Zautra 2002). Material goods (e.g. shopping, nice things, money) may represent a hedonistic dimension incongruent with the characteristics of a transition period, when energy should be spent on facing change and challenge (Levinson 1986), integration of meaning and continuity (Erikson 1950) rather than on extrinsic values.

Finally, we also observed different effects of associating knowledge and understanding with happiness for adolescents and adults. Adults who listed knowledge more often experienced more positive affect but there was an inverse effect for adolescents. Perhaps the value of knowledge may not be beneficial in adolescence because it is a sign of an unresolved conflict; the issue of working hard to acquire knowledge should have been resolved at an earlier stage (Industry vs. Inferiority, Erikson 1950). Moreover, knowledge and understanding are associated with eudaimonic elements of lay conceptions of happiness (internalised values, spiritual and competence development) and developing such an approach to happiness requires a certain level of maturity and the resolution of the most important tasks of adolescence: identity formulation (Erikson 1950) or gaining independence (Levinson 1986). More recent research suggests that solving these tasks nowadays lasts much longer than expected by Erikson, so the new stage of ‘emerging adulthood’ at ages 18–29 has been proposed (Arnett 2012). These findings suggest that eudaimonic conceptions of happiness may be beneficial only after these tasks have been completed, usually later than 18, whereas our teenaged sample was 13–18. As a result, teenagers who associated happiness with the eudaimonic dimension had lower indices of positive affect.

Contrastingly, adults who associated happiness with knowledge and understanding (personal growth, competence and spiritual development) experienced increased positive affect. These eudaimonic beliefs about happiness seemed to indicate maturity related to the search for generativity, which can be achieved by assuming socially valuable roles (Erikson 1950) such as that of a parent or, later on, a mentor (Levinson 1986).

In conclusion, people mostly associate happiness with health and relationships but the effect of lay conceptions of happiness on experienced well-being differs depending on gender and age. Associating happiness with work and relationships promotes well-being, while associating it with material possessions may be damaging, particularly for men and in times of transition. Moreover, Polish women who associate happiness with relationships experience more positive emotions while men who do the same experience less positive emotions. Associating happiness with knowledge and understanding in the adult sample promoted well-being but decreased well-being in the adolescent sample.

4.4 Limitations and Future Research

First, the method used—the associative technique—is only one possible way to measure lay conceptions of happiness. As stated in the Methods, this technique seemed most fitting for the purpose of the study but its limitations include problems with interpretations of the associations themselves. Associations may point to deficits; for example, people experiencing health issues would mention health more often than healthy people, or people experiencing problems in relationships would more often claim that happiness is associated with relationships. However, associations may represent instead those areas that participants feel particularly good about; for example, they may associate happiness with a particular relationship (e.g. listing ‘child’ as their first association) because it currently makes them happy. The list of possible interpretations is surely not complete and this needs to be considered in future studies.

Second, the study used a Polish sample, which limits the possibility for generalization, especially in terms of gender effects. The results can be considered universal only after similar studies have been conducted in other countries, or if similar findings are obtained after controlling for significant social or cultural variables, such as traditional gender roles and stereotypes about femininity and masculinity prevalent in a particular society.

Third, the transitionality of the periods was inferred from the characteristics of particular age groups. We did not verify if the participants experienced these transitions but relied on objective criteria, such as accompanying stages of formal education. Future work would need to verify the transitionality of particular periods in terms of subjective experience.

Notes

This notion is similar to ideas expressed by Csikszentmihalyi (2000).

This process is similar to assumptions in social role valorization theory (Wolfensberger 2011).

Such ideas can be found in biological conceptions (e.g. gender differences arise from the different biological roles of males and females in reproduction and underlie gender role development and differentiation), sociologically-oriented theories (emphasizing construction of gender at an institutional level) or social cognitive theory (emphasizing the learning process) (Bussey and Bandura 1999).

References

Argyle, M. (1999). Causes and correlates of happiness. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 353–373). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Arnett, J. (2012). Going global: New pathways for adolescents and emerging adults in a changing world. Journal of Social Issues, 68(3), 473–492. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2012.01759.x.

Baltes, P. B., & Baltes, M. M. (1990). Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimization with compensation. In P. B. Baltes & M. M. Baltes (Eds.), Successful aging: Perspectives from the behavioral sciences (pp. 1–34). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497.

Bojanowska, A., & Zalewska, A. M. (2014). Subjective well-being at different stages of life: The interplay of emotional reactivity and social support (manuscript submitted for publication).

Bonn, G., & Tafarodi, R. W. (2013). Visualizing the good life: A cross-cultural analysis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(6), 1839–1856. doi:10.1007/s10902-012-9412-9.

Bradburn, N. M. (1969). The structure of psychological well-being. Oxford: Aldine.

Brickman, P., & Campbell, D. T. (1971). Hedonic relativism and planning the food society. In M. H. Appley (Ed.), Adaptation-level theory (pp. 287–305). New York: Academic Press.

Brown, K., Kasser, T., Ryan, R. M., Alex Linley, P. P., & Orzech, K. (2009). When what one has is enough: Mindfulness, financial desire discrepancy, and subjective well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(5), 727–736. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2009.07.0.

Bussey, K., & Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory of gender development and differentiation. Psychological Review, 106(4), 676–713. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.106.4.676.

Butkovic, A., Brkovic, I., & Bratko, D. (2012). Predicting well-being from personality in adolescents and older adults. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13(3), 455–467. doi:10.1007/s10902-011-9273-7.

Carr, A. (2009). Psychologia pozytywna. Poznań: Zysk i s-ka.

Caunt, B. S., Franklin, J., Brodaty, N. E., & Brodaty, H. (2013). Exploring the causes of subjective well-being: A content analysis of peoples’ recipes for long-term happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(2), 475–499. doi:10.1007/s10902-012-9339-1.

Costa, P. T., McCrae, R. R., Zonderman, A. B., Barbano, H. E., Lebowitz, B., & Larson, D. M. (1986). Cross-sectional studies of personality in a national sample: II. Stability in neuroticism, extraversion, and openness. Psychology and Aging, 1(2), 144–149. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.1.2.144.

Cross, S. E., & Madson, L. (1997). Models of the self: Self-construals and gender. Psychological Bulletin, 122, 5–37.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Beyond boredom and anxiety: Experiencing flow in work and play. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Delle Fave, A., Brdar, I., Freire, T., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Wissing, M. P. (2011). The eudaimonic and hedonic components of happiness: Qualitative and quantitative findings. Social Indicators Research, 100, 185–209.

Delle Fave, A., Brdar, I., Wissing, M., & Vella-Brodrick, D. (2013a). Sources and motives for personal meaning in adulthood. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6, 517–529.

Delle Fave, A., Wissing, M. P., Brdar, I., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Freire, T. (2013b). Perceived meaning and goals in adulthood: Their roots and xrelation with happiness. In A. Waterman (Ed.), The best within us: Positive psychology perspectives on eudaimonia (pp. 227–248). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55(1), 34–43. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34.

Diener, E., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2002). Will money increase subjective well-being? A literature review and guide to needed research. Social Indicators Research, 57, 119–169.

Diener, E., & Chan, M. Y. (2011). Happy people live longer: Subjective well-being contributes to health and longevity. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 3(1), 1–43. doi:10.1111/j.1758-0854.2010.01045.x.

Diener, E., & Diener, C. (1996). Most people are happy. Psychological Science, 7(3), 181–185.

Diener, E., Emmons, R., Larsen, J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75.

Diener, E., & Oishi, S. (2005). The nonobvious social psychology of happiness. Psychological Inquiry, 16(4), 162–167. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli1604_04.

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. P. (2004). Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5(1), 1–31. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00501001.x.

Erikson, E. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Morton.

Eurostat. (2010). Well-being indicators. Feasibility study. Results of critical review. Paper presented at the 8th meeting of the working group on sustainable development, Luxembourgh.

Forest, K. B. (1996). Gender and the pathways to subjective well-being. Social Behavior and Personality, 24(1), 19–34. doi:10.2224/sbp.1996.24.1.19.

Fujita, F., et al. (1991). Gender differences in negative affect and well-being: The case for emotional intensity’. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 427–434.

Główny Urząd Statystyczny, GUS (2012) Podstawowe informacje o sytuacji demograficznej 2012.[Basic information on the demographic situation 2012], retrieved on January 21st, 2014 from http://www.stat.gov.pl/cps/rde/xbcr/gus/l_podst_inf__o__syt_demograficznej_2011.pdf

IBM Corp. (2011). IBM statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Ijzendoorn, M. H., Goossens, F. A., & van der Veer, R. (1984). Klaus F. Riegel and dialectical psychology: In search for the changing individual in a changing society. Storia e critica della psicologia, 5(1), 5–28.

Jaros, R., & Zalewska, A. M. (2008). Jakość życia w zależności od sytuacji na rynku pracy (p. 66). Łódź: PIĄTEK TRZYNASTEGO Wydawnictwo. ISBN 978-83-61479-48-2.

Joshanloo, M. (2012). A comparison of Western and Islamic conceptions of happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies,. doi:10.1007/s10902-012-9406-7.

Judge, T. A., & Watanabe, S. (1993a). Another look at the job satisfaction–life satisfaction relationship. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 939–948.

Judge, T. A., & Watanabe, S. (1993b). Another look at the job–life satisfaction relationship. Academy of Management Best Papers Proceedings,. doi:10.5465/AMBPP.1993.10317003.

Karwoski, T. F., & Berthold, F, Jr. (1945). Psychological studies in semantics: II. Reliability of free association tests. Journal of Social Psychology, 22(1), 87–102.

Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1993). A dark side of the American dream: Correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(2), 410–422. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.65.2.410.

Koralewicz, J. (1987). Autorytaryzm, lęk, konformizm. Wrocław: Ossolineum.

Kroll, C. (2011). Different things make different people happy: Examining social capital and subjective well-being by gender and parental status. Social Indicators Research, 104(1), 157–177. doi:10.1007/s11205-010-9733-1.

Langdon, D., & Klomegah, R. (2013). Gender wage gap and its associated factors: An examination of traditional gender ideology, education, and occupation. International Review of Modern Sociology, 39(2), 173–203.

Lehmann, V., Tuinman, M. A., Braeken, J., Vingerhoets, A. M., Sanderman, R., & Hagedoorn, M. (2014). Satisfaction with relationship status: Development of a new scale and the role in predicting well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies,. doi:10.1007/s10902-014-9503-x.

Levinson, D. J. (1986). A conception of adult development. American Psychologist, 41(1), 3–13.

Lu, L., & Gilmour, R. (2004). Culture and conceptions of happiness: Individual oriented and social oriented swb. Journal of Happiness Studies, 5(3), 269–291. doi:10.1007/s10902-004-8789-5.

Lucas, R. E., Diener, E., & Suh, E. (1996). Discriminant validity of well-being measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3), 527–539.

McMahan, E. A., & Estes, D. (2010a). Measuring lay conceptions of well-being: The beliefs about well-being scale. Journal of Happiness Studies,. doi:10.1007/s10902-010-9194-x.

McMahan, E. A., & Estes, D. (2010b). Hedonic versus eudaimonic conceptions of well-being: Evidence of differential associations with experienced well-being. Social Indicators Research,. doi:10.1007/s11205-010-9698-0.

McMahan, E. A., & Estes, D. (2012). Age-related differences in lay conceptions of well-being and experienced well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13(1), 79–101. doi:10.1007/s10902-011-9251-0.

Oleś, P. (1995). Kryzys “połowy życia” u mężczyzn. Psychologiczne badania empiryczne [Mid-life crisis among men. Psychological empirical studies]. Lublin: Redakcja Wydawnictwa KUL.

Oleś, P. (2000). Psychologia przełomu połowy życia [Psychology of mid-life breakthrough]. Lublin: Redakcja Wydawnictwa KUL.

Pflug, J. (2009). Folk theories of happiness: A cross-cultural comparison of conceptions of happiness in Germany and South Africa. Social Indicators Research, 92(3), 551–563. doi:10.1007/s11205-008-9306-8.

Reich, J. W., & Zautra, A. J. (2002). Arousal and the relationship between positive and negative affect: An analysis of the data of Ito, Cacioppo, and Lang (1998). Motivation and Emotion, 26(3), 209–222. doi:10.1023/A:1021773013487.

Reid, A. (2004). Gender and sources of subjective well-being. Sex Roles, 51(11–12), 617–629. doi:10.1007/s11199-004-0714-1.

Robinson, O. C., & Smith, J. A. (2010). Investigating the form and dynamics of crisis episodes in early adulthood: The application of a composite qualitative method. Qualitative Research In Psychology, 7(2), 170–191. doi:10.1080/14780880802699084.

Ross, A., Fullop, M., & Pergar Kuscer, M. (2006). Teachers’ and pupils’ constructions of competition and cooperation: A three-country study of Slovenia, Hungary and England. Ljubljana: Tiskatna Littera.

Rotter, J. B., & Rafferty, J. E. (1950). Manual: The Rotter incomplete sentence blank. College form. New York: Psychological Corp.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166.

Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. H. (2008). Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 13–39. doi:10.1007/s10902-006-9019-0.

Schimmack, U. (2008). The structure of subjective well-being. In M. Eid & R. J. Larsen (Eds.), The science of subjective well-being (pp. 97–123). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Schmitt, D. P., Realo, A., Voracek, M., & Allik, J. (2008). Why can’t a man be more like a woman? Sex differences in Big Five personality traits across 55 cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(1), 168–182. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.94.1.168.

Sęk, H., & Cieślak, R. (2004). Wsparcie społeczne, sposoby definiowania, rodzaje i źródła wsparcia, wybrane koncepcje teoretyczne. In H. Sęk & R. Cieślak (Eds.), Wsparcie społeczne, stres i zdrowie. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa.

Srivastava, A., Locke, E. A., & Bartol, K. M. (2001). Money and subjective well-being: It’s not the money, it’s the motives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(6), 959–971. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.80.6.959.

Szalay, L. B., & Brent, J. E. (1967). The analysis of cultural meanings through free verbal associations. Journal of Social Psychology, 72(2), 161–187.

Tesch-Römer, C., Motel-Klingebiel, A., & Tomasik, M. J. (2008). Gender differences in subjective well-being: Comparing societies with respect to gender equality. Social Indicators Research, 85(2), 329–349. doi:10.1007/s11205-007-9133-3.

Torras, M. (2008). The subjectivity inherent in objective measures of well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(4), 475–487.

Trzcinski, E., & Holst, E. (2012). Gender differences in subjective well-being in and out of management positions. Social Indicators Research, 107(3), 449–463. doi:10.1007/s11205-011-9857-y.

Trzebinska, E. (2008). Psychologia pozytywna. Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Naukowe i Profesjonalne.

Uchino, B. N. (2004). Social support and physical health: Understanding the health consequences of relationships. Yale: Yale University Press.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070.

Wojciszke, B. (2010). Sprawczość i Wspólnotowość. Gdańsk: GWP.

Wolfensberger, W. (2011). Social role valorization: A proposed new term for the principle of normalization. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 49(6), 435–440. doi:10.1352/1934-9556-49.6.435.

Zalewska, A. (1987). Temperament młodzieży uczącej się a ocena jej aktywności przez rówieśników. Psychologia Wychowawcza, 30(4), 415–430.

Zalewska, A. (1998). Ważność wartości społecznych wśród młodzieży uczącej się. Forum Psychologiczne, 3(2), 144–165.

Zalewska, A. (2003). Dwa światy. Warszawa: Academica.

Zawadzki, B., & Strelau, J. (1997). Formalna Charakterystyka Zachowania – Kwestionariusz Temperamentu. Podręcznik. Warszawa: Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych PTP.

Zweig, J. S. (2014). Are women happier than men? Evidence from the gallup world poll. Journal of Happiness Studies,. doi:10.1007/s10902-014-9521-8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bojanowska, A., Zalewska, A.M. Lay Understanding of Happiness and the Experience of Well-Being: Are Some Conceptions of Happiness More Beneficial than Others?. J Happiness Stud 17, 793–815 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9620-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9620-1