Abstract

Can elected officeholders use their power to extract rents for themselves, or can their accountable behavior be ensured by a threat of future elections? It has been argued that such a threat may fail, particularly if voters are forward looking and elections serve a selection purpose. We consider the accountability problem in elections with selection concerns and multiple voters. When there are multiple voters, pivotality considerations may support equilibria where incumbents behave accountably even with a selection incentive in their favor. In an accompanying laboratory experiment we find that there is heterogeneity among incumbents in terms of their accountability—some incumbents extract much, others do not. Voters are always more likely to re-elect the incumbent if there is a higher future benefit to the voters from her re-election, but less so if they extract rents. An interesting equilibrium is when the incumbent creates a majority group of voters and treats them favorably, with this favored majority voting for her. Here voters’ beliefs about their pivot probabilities are tied to whether they are in this majority group or not.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In democratic regimes voters delegate the decision rights on the choice of public goods and the power to redistribute to political agents. This principal–agent relationship is not perfect. The agents are endowed with legislative or executive powers. Ideally, the political agents act on behalf of the voters. But they might abuse this power to extract rents for their own benefits, use funds to work on their legacy to history or fund prestige projects that give little benefits to the voters.

One possible way to discipline elected representatives and to prevent these types of extractive behavior is the voter’s power over the decision to re-elect these representatives on the basis of their actions in office. In seminal contributions, Barro (1973) and Ferejohn (1986) showed how elections may serve to discipline office-holders, and how voters can sanction politicians in an equilibrium that respects sequential rationality.Footnote 1

This retrospective voting hypothesis led to considerable empirical research since the pioneering work by Kramer (1971). The seminal contribution by Fiorina (1978) drew attention to retrospective voting on the basis of voters’ personal economic condition. More recent surveys or original contributions offering literature surveys are Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier (2000), Alt et al. (2011) and Kayser and Peress (2012). It establishes a role for retrospective behavior by which economic performance and wellbeing of the individual voter matter in her voting decisions. Voters punish incumbents at the ballot box if they are economically worse off.

This sanctioning mechanism might become inoperative if voters have forward looking concerns—like selecting the best candidate who maximizes future benefits. Voters might view elections as a tool to select the best candidate for the office. Considering past actions of the incumbent sunk, if at an election voters anticipate that one of the available candidates (say, the incumbent) offers higher future payoffs, there is an incentive to select that candidate. This forward looking selection motive will dominate and render the retrospective sanctioning threat empty, when voters are sequentially rational. The choice of whether to re-elect an elected representative takes place at the end of the office period. Rent-seeking or appropriation that took place during the office period is sunk at that point of time. Assuming that feelings of revenge etc. are absent, voters should be forward looking. Time consistent voting behavior implies that they might even re-elect such an incumbent, if the alternative is to elect a competitor who does not behave differently or is even worse. Fearon (1999) made this point very forcefully. Besley (2006), Woon (2012), and Ashworth (2012) also take up this argument.

This brings us to two questions. Can the threat of not being re-elected, induce accountable behavior of an incumbent in an equilibrium when voters are fully rational and have forward looking concerns? Empirically, does this threat result in accountable behavior? Here, accountable behavior is defined as incumbent acting in the interest of the voters and not appropriating the resources for herself. In the paper, we contribute to these two questions. We reconsider the relationship between sanctioning and selection from a theory perspective as well as using a laboratory experiment. We assume a two period voting game with one incumbent office-holder, one challenger politician and many voters. In the first period, the incumbent can take a decision to extract rent or to act in the interest of voters. This is followed by the voting stage. We assume that all voters prefer the incumbent to get re-elected. This preference is taken as exogenous and we call this a selection incentive in favor of the incumbent or an incumbency advantage.Footnote 2 It is independent of the incumbent’s actions or performance in office and the incumbent’s actions and their consequences are sunk at the election stage.Footnote 3 In a short theory analysis we identify a perfect Bayesian equilibrium with sanctioning of the incumbent even if all voters have uniform and strong selection preferences and prefers that the incumbent is re-elected. The main departure from the literature that brings this equilibrium into existence is the consideration of pivotality beliefs that become important if the electorate consists of more than one voter and applies majoritarian voting. The voters’ selection motive dominates any sanctioning role of elections if voters have strict preferences for one candidate over the other, but this applies only for those voters who think that they can influence the majoritarian electoral outcome, i.e., those voters who believe they are pivotal.

We identify an asymmetric equilibrium that has an interesting structure. The electorate is homogeneous ex-ante, but becomes endogenously divided by the incumbent into a majority group that is favored by the incumbent and a minority group that is treated unfavorably. The majority that is favored receives positive benefits from the incumbent’s actions and the minority that is unfavored receives nothing. The favored majority constitutes the group of voters who eventually supports and re-elects the incumbent. In this equilibrium each of the favored voters is pivotal in the election outcome. The minority group is excluded from the distribution of benefits. They still prefer that the incumbent is re-elected, but in the equilibrium none of these voters has real voting power. Each of the members in the minority group is non-pivotal in the equilibrium. The mistreated voters choose to vote against the incumbent. This is optimal for them, but is a weakly dominated strategy.Footnote 4 To an outside observer, the treatment of voters by the politician and the resulting voting behavior may appear to be reciprocal. It appears as if mutual favoritism between a majority subgroup of the electorate and the incumbent guides the players’ behavior. However, this apparent ‘reciprocity’ is only spurious.

The elimination of weakly dominated strategies as well as trembling are plausible refinement concepts and the fact that the equilibrium would be a victim of such refinement concepts seemingly makes it less compelling. However, rather than following such refinement concepts we take an experimental route and check whether and to what extent laboratory subjects’ behavior is in line with the predictions of such an equilibrium. This leads to the second part of the paper, where we report on a voting experiment that we conducted. We find a considerable diversity of behavior. Incumbents who behave more accountably are rewarded by re-election more frequently than less accountable ones. This holds with and without a selection motive being present, but a selection motive generally leads to less accountable behavior, and to a larger re-election probability of the incumbent for given levels of accountability.

We find that voting behavior is influenced by the level of accountability of the incumbents and the selection incentive. Voters’ belief about the likelihood of their vote being pivotal in the election outcome (henceforth pivotality beliefs) is influenced by whether they were part of the majority that was favored by the incumbent or not. However, we do not observe stronger selection effects on the voters who believe to be pivotal. On the side of politician behavior, some incumbents choose behavior that is in line with the equilibrium that favors a majority and the voting behavior in these cases is qualitatively in line with the predictions made by the equilibrium as well.

Our experiment is related to work by Collier et al. (1987). They find evidence in the laboratory for voters using a reward–punishment model to induce politicians to act in their interests. Woon (2012) also sheds a favorable light on retrospective voting. The paper uses an incomplete information voting experiment where politicians vary in types and the voters try to match them to a probabilistic state of the world. The paper observes that voters rely on a retrospective voting behavior.

Feltovich and Giovannoni (2015) also test retrospective and prospective voting motives (sanctioning and selection respectively) in the laboratory. In their experiment, the incumbents can appropriate from a given budget, with the remaining amount distributed equally among the voters. The amount voters receive serves as the main focus of the retrospective voters. They then allow (non-binding) campaign promises from the candidates to induce prospective voting concerns. They find that candidates who promise less appropriation are elected more often indicating prospective voting. Voters also punish those candidates who break their campaign promises, indicating that retrospective voting gives credibility to campaign promises/prospective voting. They also show that voting in line with selection motive requires sophistication from the side of the voters to evaluate the quality of the candidate and her suitability to the office in the form of credibility of campaign promise. Often retrospective voting is the simpler alternative to this cognitively demanding task.

In our experiment we simplify the voters’ task by making the selection incentive as straightforward as possible. We induce a preference for the incumbent through design by giving a higher payoff to all the voters if the incumbent is re-elected. We also deviate from many of the past experiments by introducing majority voting. A single voter may or may not be pivotal in the election outcome in our setting and our analysis focuses on this dimension.

Our analysis is also related to the literature on vote buying. Dal Bó (2007) allows for sophisticated vote-buying strategies by a single candidate. A related mechanism is at work in Dahm et al. (2014) in a different context. Both approaches use the fact that there is a redundancy of votes for reaching a simple majority and that voters can be influenced by reward mechanisms. Implicitly they give the incumbent politician the right to make contingent price offers for their votes. What the incumbent pays may not only depend on the voter’s choice but also on the aggregate electoral outcome. This type of sophisticated vote-buying requires an ability to commit on the side of the candidate. We do not assume such commitment. A further literature gives politicians commitment power to make credible promises about their behavior once they are elected. They also give both the incumbent and a challenger active roles. Seminal papers are by Myerson (1993) and Lizzeri and Persico (2001). This type of commitment is absent in the Barro-Ferejohn framework which we rely on and this lack of commitment is at the center of the moral hazard problem.

Our game is also mildly related to the ultimatum game literature, particularly the one with multiple responders. An early paper on this is Kagel and Wolfe (2001). These games are also about distributional offers to which a group of players reacts. This strand of literature focuses on identifying the extent to which fairness models explain the decisions made in ultimatum games with multiple respondents. Diermeier and Gailmard (2006) tests if the theories of self-interest, egalitarianism or inequality aversion can explain the behavior in ultimatum games with two responders and reports that the results are inconsistent with predictions of these three models. Fischer and Güth (2012) use three party ultimatum games where the proposer can exclude one of the other players from getting a share of the pie. They do not find evidence to support that this exclusion changes the behavior of the responder and the non excluded responder.

There are also some important differences between these games and our voting context. First, the accountability game and the ultimatum game have different structures. In our framework the allocation choice that is made by the incumbent politician is not subject to acceptance or rejection by the set of voters: it is implemented in any case. Second, voters make decisions that might lead to re-election of the incumbent or vote her out of office. Again, this is not a problem of division of a given pool of resources between them. Thirdly, in our setting all voters have similar roles—we do not ex-ante differentiate the electorate. A fourth conceptual difference is the context. We consciously frame our game as a voting game. In such a game incumbents and voters are quite different subjects. Moreover, politicians stay politicians and voter stay voters throughout all rounds. This makes an egalitarian norm between them less salient than in the ultimatum game.

In the next section we reconsider the standard sanctioning/selection model with both moral hazard and candidate heterogeneity. Section 3 presents the hypotheses, Sect. 4 presents the experimental set-up, Sect. 5 presents results from the experiment and Sect. 6 concludes.

2 A simple voting framework

Our voting framework with an accountability problem has two periods, \(t=1\) and \(t=2\). The set of players consists of a politician who reigns in period 1 and a set N of voters \(i=1,\ldots ,(2n-1)\). Politicians and candidates are labeled as female (‘she’) and voters are male (‘he’) in what follows. In the first stage the incumbent politician has a budget of given size \(m=1\). She chooses non-negative period-1 transfers \(x_{1},\ldots ,x_{2n-1}\) to the voters. The sum of these transfers cannot exceed the budget m. She keeps the remainder \(y=1-\Sigma _{i\in N}x_{i}\) for herself. In the second stage voters cast their votes. All voters vote. Each voter chooses between two politicians: the incumbent and a challenger (a player with no active role and decision options). They vote simultaneously and the majority rule applies: the politician who receives at least n votes wins.

Payoffs of active players are as follows. The incumbent keeps the amount y of the budget and this is the payoff if the incumbent is not re-elected. She has an additional benefit \(b>1\) and therefore a total payoff of \(y+b\) if and only if she wins at least n votes. This benefit b may be thought of as office rents from being re-elected. The sum of these constitute the incumbent’s payoff. Voters value their transfer \(x_{i}\). A benefit \(\theta \ge 0\) is added if the incumbent is re-elected. We address two cases: The voter might be indifferent about whether the incumbent is re-elected (\(\theta =0\)), as in the analysis by Ferejohn (1986). Or the voter prefers the incumbent and attributes \(\theta >0\) to her re-election as in Fearon (1999).Footnote 5 Like all other aspects in this model, the size of the incumbency advantage \(\theta\) is common knowledge. Voter i’s payoff is the sum of the transfer \(x_{i}\) and the benefit \(\theta\) in case of re-election of the incumbent.

Let us consider the choice of a voter as a function of \((y,x_{1},\ldots ,x_{2n-1})\). Define \(\hat{p} _{i}\) as voter i’s probability belief that i’s vote is pivotal, i.e., the probability which i attributes to the event that exactly \(n-1\) of all other voters j vote for the incumbent and all the other \(n-1\) voters vote for the challenger. A voter i who maximizes his payoff and attributes a positive probability \(\hat{p}_{i}>0\) to being a pivotal voter strictly prefers to vote for the incumbent if \(\theta >0\) and is indifferent if \(\theta =0\). A voter who attributes a zero probability \(\hat{ p}_{i}=0\) to being pivotal is precisely indifferent about whether to vote for or against the incumbent.

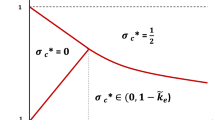

This allows us to recover the results of Ferejohn (1986) and of Fearon (1999). If there is only one single voter, this voter is pivotal with probability 1. Accordingly, this voter will always vote for the incumbent if \(\theta >0\) (Fearon). If \(\theta =0\), then the voter is indifferent about whom to vote for and may choose any tie-breaking rule. In particular, the voter may choose to vote for the incumbent if and only if \(y=0\), i.e., if the incumbent shows full accountability. If the incumbent, for some reason, anticipates this tie-breaking rule, then the incumbent will choose \(y=0\) and will be re-elected (Ferejohn). For a larger but uneven number of voters pivotality (and voters’ beliefs about it) becomes an issue. By choice of a suitable tie-breaking rule it is possible to establish that any choice of \(y\in [0,m]\) and a majority of votes for the incumbent can emerge as a perfect Bayesian equilibrium, irrespective of the size \(\theta\) of the incumbency advantage.

Intuitively, for any budget allocation choice a voting subgame exists for which a supermajority (at least \(n+1\) of voters) vote for the incumbent. This holds because, if a set with at least n voters votes for the incumbent, then any of the voters outside this set is not pivotal and therefore indifferent about whom to vote for. This voter may well vote for the incumbent as well. A particular value of y can, for instance, be supported by tie-breaking choices of indifferent voters such that this is the largest y for which non-pivotal (and hence indifferent) voters re-elect the incumbent: the incumbent is re-elected with a supermajority if the amount kept by her is smaller or equal to this y.Footnote 6 The multiplicity of equilibrium has been used by Ferejohn (1986) to support a high degree of accountability as an equilibrium by making the voter’s equilibrium choice in case of the voter’s indifference a function of the budget allocation choice.

The behavior of voters who are non-pivotal (and hence indifferent) might be conditioned on the publicly observed degree of accountability of the incumbent. It may be interesting to consider the case in which any voter i can condition his behavior only on the amount of transfer \(x_{i\text { }}\) which he received. We can characterize the following perfect Bayesian equilibrium in this case:

Proposition 1

Suppose the incumbent has a strictly positive incumbency advantage. If\(n>1\), then a perfect Bayesian equilibrium exists that is described by favoritism as follows. The politician chooses to allocate\(x_{j}=1/n\)to preciselynvoters. Each voterjbelieves that he is pivotal with probability 1 if he received\(x_{j}=1/n\), and each voter believes that he is non-pivotal if\(x_{j}\ne 1/n\). Only the voters who believe that they are pivotal vote for the incumbent.

The proof is in the appendix. The equilibrium that is characterized in Proposition 1 has some interesting properties. The voters who received transfers vote for the incumbent and voters who did not receive transfers vote against the incumbent. They behave as if they reward or punish the incumbent, depending on having been treated well or poorly. In fact, this electoral outcome is not driven by such desires to reward or punish, or to reciprocate favors. It is just a possible equilibrium outcome of forward looking voters. All voters are sequentially rational and narrowly selfish.

Proposition 1 makes suggestions about how beliefs are formed in the equilibrium. The voters who received transfers are pivotal and voters who received nothing are not pivotal. When we move to the experimental section we also provide a behavioural story on how these beliefs are formed. To the extent that pivotality is interpreted ex-post as a measure of political connectedness or influence, it seems as though the ones who are politically connected are the ones who receive transfers. The voters who do not receive transfers are not among the selectorate. They are also in a minority. They are excluded and deprived of political influence. The equilibrium appears as if there is a majority of voters who establish an ingroup, and a minority of voters who form the outgroup. But ex-ante there is no heterogeneity among voters here, there is no such element of ‘connectedness’ here and no differences in connectedness. The ingroup-outgroup interpretation with reciprocity between the incumbent and her selectorate and the apparent causality are purely spurious.

3 Hypotheses

Theory considerations showed that there is a large set of equilibrium outcomes. Refinement concepts tell us that some of these equilibria might be more plausible than others from a theory point of view. However, an at least equally relevant question is what voters really do. We first concentrate on predictions about the voting subgames, which support the following hypotheses about the qualitative behavior in the laboratory.

H1 Selection hypothesis

For any given allocation choices of the incumbents, the voters are more inclined to vote for the incumbent if the incumbent has an incumbency advantage.

This hypothesis is a mild version of Fearon’s selection dominance argument. The strict version of this hypothesis is the claim that selection always dominates the voting incentives. If all voters prefer a candidate, they all vote for him. Laboratory results are typically less deterministic, so the Selection Hypothesis captures the essence of the theory claim about selection in a qualitative form.

H2 Retrospective voting hypothesis

(1) If the incumbent has no incumbency advantage, voters are more inclined to vote for the incumbent if the incumbent behaved more accountably. (2) For any given incumbency advantage, voters are more inclined to vote for the incumbent if the incumbent behaved more accountably.

This hypothesis is formulated on the basis of the original considerations by Barro (1973) and by Ferejohn (1986) and reflects the idea of retrospective voting. The weak part of the hypothesis [i.e., part (1)] refers to Ferejohn’s result that a sanctioning equilibrium exists if the voters are indifferent about who is in power in the future. The strong part of the hypothesis [i.e., part (2)] suggests that this result is also true if one allows for an incumbency advantage of a given size.

Voters’ payoff from voting for the incumbent is higher if the incumbency advantage is higher, and if the voter attributes a higher probability to being pivotal in the election. A voter’s belief about own pivotality probability and incumbency advantage, hence, interact positively and a higher pivotality belief should therefore make the incumbency advantage more salient and more influential for the voting decision. This leads to the pivotality hypothesis.

H3 Pivotality hypothesis

The influence of incumbency advantage on voter behavior is stronger if a voter considers it more likely that he is pivotal.

We can test this hypothesis using the stated beliefs of voters about whether they think it is more likely or not that their vote is decisive.

In the experiment we will give the incumbent choice alternatives in which all voters are treated equally and alternatives in which the incumbent can favor a majority of voters, to the detriment of a minority of voters. In line with the equilibrium behavior that is characterized in Proposition 1, we would expect behavior along the following lines:

H4 Favored majorities hypothesis

Voters who belong to the favored majority expect to have a higher probability of being pivotal than voters in a less favored minority. Moreover, the voters in the favored majority are more likely to vote for the incumbent.

Next we turn to incumbents’ choices. The multiplicity of equilibria in the voting subgame does not give the incumbent very clear guidance, and one would therefore expect to see a wide range of possible accountability choices. However, taking the above probabilistic hypotheses by heart, they imply that an incumbent may consider it more likely to be re-elected if she has an incumbency advantage. Moreover, for a given incumbency advantage, the incumbent may consider it more likely to be re-elected if she behaves more accountably. This is also the clear prediction from Fearon’s claim that selection considerations dominate, as sanctioning is only time consistent if the voter is indifferent. Hence, we expect behavior in line with the following

H5 Decreasing accountability hypothesis

The incumbent behaves less accountably if she has an incumbency advantage.

Endowed with these hypotheses we now describe the experimental setting.

4 Experimental setting

The experiment was conducted among the students of a large German university in the months of October and November, 2016. The program was coded in z-Tree (Fischbacher 2007) and the subjects were invited through ORSEE (Greiner 2004). A between-subjects design was used, i.e., each subject participated in only one treatment. The instructions for the subjects were handed out to them on paper. In addition, they had to watch a video in which the instructions were read to them aloud by the same person and in an unchanged environment for the two treatments.Footnote 7 Participants were informed of the anonymity of their decisions and that they were not allowed to communicate with each other. The subjects also had to undergo mock questions to check their comprehension of the instructions and the rules of the experiment before proceeding.

Participants were informed that they are part of an interaction resembling a political process.Footnote 8 Subjects interacted in groups of five in each treatment. Each group consisted of one incumbent politician, one challenger politician, and three voters. In each group, two of the subjects were randomly assigned the role of politician (as incumbent or challenger) and three of the subjects were assigned the role of voter. Subjects were informed of their roles and kept their respective roles throughout the experiment, i.e. a subject in the role of a politician remained in that role throughout the experiment.

The voting game consisted of two stages.

Stage 1

The incumbent politician has a budget \(m = 120\) talerFootnote 9 at her disposal. The incumbent has one decision to make—to allocate this budget between herself and the three voters in one of five possible ways as listed in Table 1.Footnote 10

Of these, option 1 [120;(0,0,0)] is where the incumbent retains the whole 120 taler and distributes nothing to the three voters (the first number in the vector corresponds to the amount the incumbent keeps for herself and the following three numbers are the amounts transfered to each of the voters). This is a case of no accountability of the incumbent office-holder. Option 2 [30;(30,30,30)] and option 4 [60;(30,30,0)] are options of partial accountability, as the incumbent keeps a smaller or larger share of the budget for herself. Option 3 [0;(60,60,0)] and option 5 [0;(40,40,40)] are options that are in conformity with full accountability, as the incumbent distributes the whole budget to the voters. The five options differ with respect to accountability, but also with respect to symmetry/asymmetry of treatment of voters. Note that options 1, 2 and 5 treat all voters perfectly equally both from an ex-ante point of view as well as from the ex-post allocation. Options 3 and 4 describe distributions that allocate different amounts of the budget to different voters. If the incumbent chooses one of the asymmetric options, the computer determines which of the voters receive positive amounts and which voter gets zero. Hence, from an ex-ante point of view, the incumbent treats all voters equally. But from an ex-post point of view, the voters are treated differently, as two voters receive considerable amounts and one voter receives nothing. As anonymity applies and the incumbent does not know the identity of voters 1, 2 and 3, these asymmetric outcomes are implemented by a random mechanism.

Stage 2

After the incumbent has made the allocation decision, the voting decision follows. The voters make voting choices. These are possibly a function of the allocation choices made by the incumbent. The voters have to decide to either vote for the incumbent or for the challenger. However, to elicit more observations, we use the strategy method for the voting process. Voters have to vote for the incumbent or challenger under each realizable state of the world. Due to the asymmetry in the amounts voters receive in two of the five allocation options, the five allocation choices of the incumbent translate into seven cases describing the possible situations of an individual voter. These different situations are listed in Table 2.

When using the strategy method the voters’ choices are not observed by the politician at the point of making her choice, and the conditional choices made by the voters are then applied to the actual choice made by the incumbent. This procedure is, hence, equivalent to a strict sequentiality in decision making in which the allocation choice is followed by the voting choices. The votes that result are tallied and the winner is announced. The winner of the election receives \(b=140\) taler (this amount exceeds the initial budget \(m=120\) taler).

After the voting choices have been made and before the winner is announced we elicit the beliefs of voters on how pivotal their votes were in each of the seven voting choices they made. Voters are asked if they believed that it was more or less likely that their vote tipped the outcome in the election. “Tipping” here means that had the voter voted differently, the majority outcome of the election would have been different. With three voters, a voter’s vote tips the outcome of the election only if one of the remaining two voters votes for the incumbent and the other votes for the challenger. In a way the pivotality belief of a voter shows what he thinks about the voting pattern of the other two voters. This completes the set of decisions to be made.

Each subject participates in only one session and plays the game of budget allocation followed by voting decisions eight times in this session. To avoid quasi-repeated games effects, the participants were randomly re-matched. While voters remained voters and politicians remained politicians, random re-matching made sure that a voter-subject voted on a different incumbent in each round, and that the set of co-voters also changed.Footnote 11 Among politician-subjects the role as incumbent or challenger was randomly chosen in each round.

At the end of each round, subjects are informed of the allocation vector chosen by the incumbent, the winner of the election, the number of votes received by the winner and their own earnings in taler.

Treatments

The two treatments we study are identical along all dimensions except whether the incumbent politician has an incumbency advantage in the election or not. This difference is simply in the monetary benefits of each voter if the incumbent is re-elected or not.

In the baseline treatment, voters have the same exogenous monetary benefit irrespective of whether the incumbent or the challenger is elected. More precisely, each voter receives 20 taler once the election is completed, and irrespective of whether the incumbent or the challenger is elected. The incumbency advantage is \(\theta =0\) taler. This baseline treatment is henceforth referred to as the No Incumbency Advantage treatment (NIA).

The second treatment is referred to as the Incumbency Advantage treatment (IA). The treatment follows precisely the very same rules as the baseline treatment. However, each of the voters receives 20 taler if the challenger of stage 1 gets elected and 30 taler if the incumbent gets re-elected. Hence, the incumbency advantage is \(\theta =10\) taler. In this treatment voters have a larger monetary benefit if the incumbent is re-elected.

The experiment also included post-experiment tests. These comprised standard tests of social and risk preferences (Murphy et al. 2011; Dohmen et al. 2011) and a questionnaire on the Dark Triad. It assesses the participant’s strength of narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy, three types of personality traits that were identified in psychology (see Jones and Delroy 2014). Furthermore a set of control questions on demographic information and past political activity were asked.

5 Data and results

We conducted 9 sessions in each treatment with a total number of 345 subjects (175 in NIA and 170 in IA). Around 61% of the subjects had past political experience and had voted in at least one election in the past. Of the 345 students, 172 (roughly half) identified as female. Three rounds from the main experiment and one of the post-experiment tests were randomly chosen for payment. Additionally, there was a show up fee of 6 euros. The experiment lasted 90 minutes and the average payoff was 22 euros. We now turn to the various hypotheses.

5.1 Selection versus retrospection

First we address the hypothesis on selection. A first result is that voters are more likely to vote for the incumbent when there is a selection incentive (in IA) than when there isn’t (in NIA), conditional on the transfers received. Figure 1 provides descriptive evidence. The four pairs of columns show the shares of voters who voted for the incumbent for each of the transfer amount received. Light grey bars represent the NIA treatment (left column) and the dark grey bars represent the IA treatment (right column). For all four possible levels of own receipts, voters are significantly more inclined to vote for the incumbent in IA than NIA (tests of equality of means done using Wilcoxon rank sum tests, \(p<0.001\)). The difference between the treatments are larger for own receipts of 0 and 30 taler and the gap closes down for own receipts of 40 and 60 taler.

Voting for the incumbent for each transfer received. Note: Given the different possible budget allocation choices, a voter can receive zero, 30, 40 or 60 taler. The four pairs of columns show the shares of voters who voted for the incumbent for each of these receipts, with observations from the NIA treatment in light grey (left column) and observations from the IA in dark grey (right column). For all four possible levels of own receipts, voters are more inclined to vote for the incumbent in IA than NIA

Table 3 provides the regression analysis where the dependent variable, ‘vote for the incumbent’, is binary and takes value 1 if the vote is for the incumbent and 0 if it is for the challenger. Here, we report the results from an OLS regression for ease of interpretation but they are in line with the results from probit regression (marginal effects are reported in the online appendix). We use standard errors clustered at the individual level.Footnote 12 Column (1) indicates a significant treatment effect—voters are more likely to vote for the incumbent when there is an incumbency advantage, that is, voters have a selection incentive irrespective. This is true controlling for the transfers received by the voters. As predicted by the theory on the dominant role of selection incentives, even the quantitatively small selection incentive that is caused by the incumbency advantage has a clear treatment effect that has the predicted sign and is significant. We summarize this result as the selection result.

Selection result

For any given allocation choice of the incumbents, the voters are more likely to vote for the incumbent when there is an incumbency advantage.

Next we turn to the hypothesis on retrospective voting. Column (1) of Table 3 shows that a voter’s probability of voting for the incumbent rises with the transfer amount received by this voter. Column (2) repeats the same estimation with controls. Column (3) adds accountability levels to the regression. We define full accountability as when the incumbent does not keep any of the budget and distributes everything. Partial accountability is when the incumbent keeps a part of the budget for herself and transfers the rest to all or some of the voters. A case of no accountability is when the incumbent panders all of the budget for herself. From the Table 3, other things being equal, compared to no accountability, partial accountability of the incumbent increases the probability of voters voting for the incumbent by 13 percentage points and full accountability raises it by 16.8 percentage points. Voters who get 0 taler are more likely to vote for the challenger than the incumbent (Fig. 1). However, as the own receipts increase from 0 to 30 taler, voters are more likely to vote for the incumbent in both treatments. This holds for own transfers of 40 and 60 taler although the probability of voting for the incumbent is the highest when the transfers are 40 taler in both the treatments.

Voting for the incumbent for each transfer received—details. Note: The first number in the string of numbers (for e.g., 0 in 0–30–30) corresponds to the taler received by the voter making the decision where as the next two correspond to the amounts received by the other two voters. The bars show the share of voters voting for the incumbent for their corresponding own receipts

A closer look at the voters who receive 0 taler reveals that in addition to own receipts, the voters pay attention to the amount received by the other two voters and how accountable the incumbent was in stage 1 (Fig. 2, first three sets of bars). In the no accountability case of option 1 [120;(0,0,0)] the voters who receive 0 taler overwhelmingly vote for the challenger in both treatments (only 3.93% of the voters vote for the incumbent in NIA and 15.48% in IA). In the partial accountability case of option 4 [60;(30,30,0)] 5.48% of the voters who receive 0 taler vote for the incumbent in NIA and 19.64% in IA. In the full accountability case of option 3 [0;(60,60,0)] this increases to 19.52% in NIA and 30% in IA, indicating that more voters are willing to vote for the incumbent when the incumbent was fully accountable than when she was not, irrespective of their own receipt.

A similar pattern can be observed for voters who receive 30 taler (Fig. 2, last two sets of bars). In the partial accountability case of option 2 [30;(30,30,30)], 70.36% of the voters who receive 30 taler vote for the incumbent in NIA and that increases to 85.83% in IA. However, in the lower accountability situation of option 4 [60;(30,30,0)] the percentage of voters voting for the incumbent is lower in both treatments (39.88% in NIA and 51.43% in IA).

Retrospective voting result

In both treatments, voters are more likely to vote for the incumbents when incumbents behave more accountably.

So far the results can be seen as qualitatively in line with both a mild version of the selection hypothesis of Fearon (1999) and a mild version of the retrospective voting hypothesis of Ferejohn (1986). Both types of considerations are seemingly relevant for the voting decision and none of them dominates the other in a strict sense.

5.2 Pivotality

The theory analysis in Sect. 2 highlighted pivotality beliefs of voters and their potential key role for voting behavior. Beliefs about pivotality should be an element in voters’ decision making in the context of majority voting. The argument that the selection motive should dominate all other considerations becomes less compelling when voters’ pivotality is endogenous. Voting in line with the selection motive has a selection benefit only if the voter is pivotal. As seen by Proposition 1, this consideration opened up for a wealth of different voting behaviors that can be seen as equilibrium behavior, where some of these behaviors may be seen as more plausible than others from a theory perspective of equilibrium refinement.

These considerations led to the Pivotality hypothesis as well as the Favored majorities hypothesis. We now turn to the data analysis on these hypotheses.

Before we relate voters’ pivotality beliefs with their electoral choices, we consider these pivotality beliefs and their distribution. A voter needs to form beliefs about other voters’ electoral choices to evaluate their own pivotal probability in the election outcome. For a theory of this belief formation, one can draw on what psychologists call the theory of social projection (see, e.g., Marks and Miller 1987): a voter forms an own belief and projects this way of belief formation onto the other voters. Voters might believe that their own ways of how they form their beliefs is no different from how most of the other voters form their beliefs. A voter is pivotal in our context if exactly half of the remaining voters vote for incumbent and the other half vote for the challenger.

If a voter A is confronted with two other voters B and C who receive identical transfers this may induce the belief that it is more likely that they make the same decision; hence A is unlikely to be pivotal. If B and C are treated differently—say B receives transfers from the incumbent and not C, it appears less likely that they make identical electoral decisions; hence, A is more likely to be pivotal. For the budget allocations that attribute positive and identical amounts to two of the voters and zero to a third voter, in the equilibrium the voter who receives zero anticipates that he is not pivotal—and also observes that the two other voters receive identical amounts. Instead, each of the voters who receives a positive amount anticipates that he is pivotal—and also observes that the other two voters do not receive identical amounts.

This leads us to a prediction about voters’ pivotality beliefs as a function of the transfers \(x_{voter1},x_{voter2}\) and \(x_{voter3}\) which is expressed in the Table 4. The table also provides the overview of voters’ stated pivotality beliefs. It shows that the stated pivotality beliefs are, in fact, correlated with the predictions emerging from these considerations. The correlation between the stated pivotality beliefs and actual pivotality is also positive (Spearman’s correlation coefficient is 0.1338 with \(p <0.001\) from 8273 observations.Footnote 13)

According to this line of thought, we would expect the likelihood that all voters vote identically is higher for symmetric allocations than for the asymmetric allocations. If all voters vote identically, we define the outcome to be a super-majority. A super-majority for the incumbent is when the incumbent receives all three votes and a super-majority for the challenger is when the challenger receives all three votes. The outcomes in symmetric allocations of option 1 [120;(0,0,0)], option 2 [30;(30,30,30)] and option 5 [0;(40,40,40)] would be super-majorities and the asymmetric allocations of option 3 [0;(60,60,0)] and option 4 [60;(30,30,0)] would not be super-majorities.

This can indeed be observed in the data. We can see that 75% of the cases option 1 [120;(0,0,0)] is chosen result in a super-majority for the challenger, while 52% of cases in option 2 [30;(30,30,30)] and 84% of cases in option 5 [0;(40,40,40)] result in a super-majority for the incumbent. Figure 3 graphically represents this.

Allocation vectors and super-majorities. Note: The y-axis indicates the number of votes accruing to the incumbent. Thus, a number of 0 votes accruing to the incumbent indicates a super-majority for the challenger and a number of 3 votes accruing to the incumbent indicates a super-majority to the incumbent. The size of the circles indicates in each allocation vector what share of cases resulted in each number of votes. The three symmetric allocations of option 1 [120;(0,0,0)], option 2 [30;(30,30,30)] and option 5 [0;(40,40,40)] result mostly in super-majorities (for the challenger in the former and for the incumbent in the latter two cases). The asymmetric allocations of option 3 [0;(60,60,0)] and 4 [60;(30,30,0)] do not result in super-majorities as the major share of cases result in either two votes for the incumbent or two votes for the challenger

Next we compare voting for the incumbent as a function of own pivotality beliefs, for the two treatments. We hypothesize that the effect of the incumbency advantage is stronger if the voter believes that he is pivotal. Table 5 looks at this analysis. Simply believing to be pivotal does not affect voting behavior. Being in the incumbency advantage treatment increases the decision to vote for the incumbent by 11.4 percentage points (Column (6)). However, the interaction between IA treatment and belief \(=\) pivotal is not significant as indicated in Column (8). This result does not change qualitatively if we control for the transfers received by the voters and use a slightly different specification (Table 6).

Pivotality result

Voters who believe they are pivotal are not more likely to vote for the incumbent when there is a selection incentive.

To look at why we do not find evidence for this hypothesis, we look at how the beliefs are formed. While voters’ pivotality beliefs and actual pivotality are correlated in the data, we also have a hypothesis on how beliefs depend on the allocation vector chosen by the incumbent and voters’ own share of the transfers received. The favored majorities hypothesis states that voters who belong to the favored majority expect to have a higher probability of being pivotal than voters in the less favored minority. We test this by looking at the effect of being the recipient of the non-zero amounts in option 3 [0;(60,60,0)] and option 4 [60;(30,30,0)] on the pivotality belief. The voters who receive 60 taler in option 3 and 30 taler in option 4 belong to the favored majority and the voters who receive 0 taler in these options are in the less favored minority.

Table 7 reports these results. Pivotality beliefs are affected by whether the voter is in the favored majority or not (Column (1)). Being in the favored majority increases the probability of a voter believing to be pivotal by 43.7 percentage points.

Favored majorities result

Voters receiving a positive transfer and belonging to the favored majority are more likely to expect to be pivotal than voters who are in the less favored minority.

Pivotality beliefs are not affected by the treatment manipulation, i.e., whether there is an incumbency advantage or not (Column (2)). However, the interaction term between the favored majority and the treatment indicator (IA) has a coefficient of 0.117 and is significant at the 5% level. This indicates that voters in the favored majority in the IA treatment are 11.7 percentage points more likely to believe to be pivotal. This implies that beliefs are not entirely independent of the treatment manipulation. This could be a potential reason why we do not observe selection incentive being stronger on voters who believe to be pivotal. The selection incentive and pivotality beliefs interact in our data.

5.3 Incumbents and accountability

We now turn to the decisions made by incumbents. Given that voters react differently in the two treatments to the allocation choices made by the politician, one might expect that the incumbent behavior also differs in the two treatments.

Evidence for the decreasing accountability hypothesis is obtained by looking at the average transfers observed in the two treatments. The transfers chosen by the incumbents averaged 91 taler in NIA and 88 taler in IA. The transfers are statistically different in the two treatments (Wilcoxon rank-sum test: \(p<0.001\)).

Though the transfers in IA are lower than NIA, roughly three quarters of the budget is allocated to the voters by the incumbent in IA. The incumbents appear to take the retrospective voting into account even when there is a selection incentive.

Allocation vectors chosen by the incumbent. Note: The figure shows percentage of incumbents choosing each of the allocation vectors. Percentage of incumbents choosing partial accountability options of [30;(30,30,30)] and [60;(30,30,0)] is higher in IA than in NIA and the percentage of incumbents choosing the full accountability options of [0;(60,60,0)] and [0;(40,40,40)] is lower in IA than in NIA

There are also differences in the allocation vectors chosen by the incumbent as indicated by Fig. 4. Interestingly, both of the full accountability options see a drop in the IA treatment compared to the NIA treatment. There is a corresponding increase in the partial accountability options in the IA treatment compared to the NIA treatment. The fall in full accountability options is not seen to co-exist with a rise in the no accountability option of [120;(0,0,0)], but rather with a rise in the partial accountability options. This implies that even in the presence of a selection incentive, some accountability is retained.

It is also important to note that 45% of incumbents transfer the entire budget to the voters when there is no incumbency advantage in an attempt to win them over. In comparison only 28% of incumbents transfer the entire budget when there is an incumbency advantage. This indicates that the subjects in IA seem to understand that they have a large leeway to allocate a part of the budget to themselves.

Voters’ behavior is not deterministic, but the results revealed some patterns. Incumbents who observe these patterns might choose budget allocations that maximize their payoffs given these patterns. In fact, calculating the ex-post expected earnings from choosing each allocation vector using the voting probabilities indicates that incumbents are able to exploit this pattern. Table 8 displays the expected payoffs of the incumbents for each allocation vector calculated using the re-election probabilities from the data. It shows that incumbents choose the budget allocations that give them a higher expected payoff with a higher probability.

Decreasing accountability result

When there is an incumbency advantage the incumbent behaves less accountably compared to the case of no incumbency advantage. However, some degree of accountability is retained even when there is a selection incentive.

Figure 5 indicates the re-election probabilities of the incumbents for each allocation vector they choose. It differs for the two treatments. In NIA treatment, the highest probability of re-election is for the allocation vector [0;(40,40,40)]. Here the incumbent distributes the entire budget to the voters and hence is a case of full accountability. The second highest probability is for allocation vector [0;(60,60,0)], again an option of full accountability. The partial accountability options of [30;(30,30,30)] and [60;(30,30,0)] are preferred in this order after the former two.

In case of IA, the incumbents have the highest probability of getting re-elected when the allocation vector is [0;(40,40,40)]. Incumbents choosing the vector [30;(30,30,30)] has the next highest probability of re-election. This is followed by allocation vectors [0;(60,60,0)] and [60;(30,30,0)].

Incumbents deciding to appropriate the entire budget of 120 taler do not get re-elected even with the induced incumbency advantage. The difference between the two treatments is seen on the two partial accountability cases of [60;(30,30,0)] and [30;(30,30,30)]. When there is a selection incentive voters are more likely to re-elect the incumbents who are only partially accountable than in the baseline treatment. The re-election probability of an incumbent choosing [60;(30,30,0)] increases from 20 to 41% as a result of the treatment. For an incumbent choosing [30;(30,30,30)] this increases from 70% to nearly 97%. This indicates that voters do not press for full accountability when there is a selection incentive. On the other hand the selection incentive does not bite to the extent that they are willing to re-elect an incumbent who retains the entire budget. Accountability does not disappear entirely in the presence of a selection motive.

6 Conclusion

The incumbent officeholder in a democracy with majoritarian elections might or might not act in the best interest of the voters. An incumbent politician could use the office to extract rents. We assess the quality of majoritarian elections as a disciplining device. More specifically, we consider voting behavior of a set of voters who face an electoral decision of re-electing an incumbent in a framework with and without an incumbency advantage. We investigate if the voters can hold the incumbent officeholder accountable to them in these two settings.

We find that the set of voting equilibria is very large, due to the pivotality issue and the formation of pivotality beliefs. Some of these equilibria are observationally equivalent to behavior that appears to be driven by incumbents’ favoritism and by voters’ preferences for reciprocity. We confront these theoretical results with evidence obtained from a laboratory experiment. We find qualitative evidence on voting behavior that is broadly in line with a theory suggesting that voters cast their votes prospectively. If voters have a higher future benefit from re-electing the incumbent, this yields a higher re-election probability. An incumbency advantage reduces the power of the voting mechanism to prevent incumbent governments from extracting. But we also find evidence for retrospective voting, where retrospective voting is slightly less pronounced if voting against an incumbent who behaved unaccountably is conflicting with voters’ higher future benefit of re-election.

We find that voters’ pivotality beliefs are influenced by whether incumbent politicians treat all voters alike, or whether they cultivate a favored majority. Voters in the favored majority assume they are more likely to be pivotal than the minority voters. These beliefs are correct on average. However, we see that these voters are not significantly more likely to re-elect the incumbent when there is a selection incentive compared to those who believe they are non-pivotal. One potential reason for this could be that the pivotality beliefs are not independent of the treatment variation. Voters in the incumbency advantage treatment are more likely to believe they are pivotal when they belong to the favored majority.

We also see that the behavior of incumbents reflects the observed voting behavior of the voters. Incumbents do not take full advantage if there is a selection incentive in their favor. Rather, the amount of accountability is qualitatively very similar to that of incumbents who do not have an incumbency advantage. We conclude that an exogenously given incumbency advantage makes the incumbent extract somewhat more, but typically not the maximum amount that would be feasible. Voters are able to use retrospective voting as a mechanism to discipline the officeholder. A large share of the incumbents seemingly anticipate correctly that extractive government that takes full advantage is sanctioned by the voters in the equilibrium.

Notes

Seabright (1996), Kessing (2010), and Fearon (2011) are applications of sanctioning models with pure moral hazard in different contexts. However, due to the alleged robustness concerns, much of the accountability literature turned to a study of a selection model of voting and now focuses on issues of adverse selection: it studies how to identify and select the more competent or ideologically more appealing candidate if a candidate’s true type is private information. This literature is orthogonal to our research question and is too large to be adequately surveyed here. It includes important contributions by Fearon (1999), Ashworth (2005), Ashworth and Bueno de Mesquita (2008), Besley (2006), Besley and Michael (2007), Snyder and Ting (2008), and Fox and Shotts (2009).

Modeling incumbency advantage in this way that every voter benefits from the incumbent getting re-elected is not new in the literature. For example, Buchanan and Congleton (1994) have a setting where re-election of the incumbent gives the entire constituency a benefit as senior, experienced representatives are better at their legislative tasks than junior ones.

There is a large literature on expressive aspects of voting (Brennan and Buchanan 1984; Hillman 2010; Brennan and Lomasky 1993; Brennan and Hamlin 1998) where the non-pivotal voters use their vote not to change the outcome of the election, but to express their support or dissatisfaction. If we allow for expressive preferences, this result would get stronger.

A similar analysis could be carried out for an incumbency disadvantage (\(\theta <0\)). We focus on the case \(\theta >0\) to capture forces acting in opposite directions: an incumbency advantage, that makes the voter want the incumbent (irrespective of the action of the incumbent) to be re-elected and the need for accountability, that requires that an incumbent who diverted part of the budget for private use is voted out of office. Moreover, the case with an incumbency advantage received much empirical support (see footnote 3 for references).

As has been pointed out in the introduction, the equilibria with \(y>0\) do not survive a refinement that eliminates weakly dominated strategies, and this may be support of the argument that selection incentives dominate sanctioning. One should note that even for a strict incumbency advantage (\(\theta >0\)) an equilibrium for which an incumbent is not re-elected need not be very sensitive to perturbations. Suppose that the expectation is that \(2n-2\) other players vote against the incumbent as well. In this case, this voting behavior remains optimal, even if up to \(n-2\) of these other voters deviate from their equilibrium behavior.

The recordings of these instructions are available here: https://www.tax.mpg.de/de/publikationen/instructions_incumbency_advantage.html, https://www.tax.mpg.de/de/publikationen/instructions_no_incumbency_advantage.html.

We introduce a non-neutral setting because we want subjects to bring their political behavior and beliefs on to the laboratory. Additionally, this only affects the accountability part of the experiment which applies to both the treatment and control and is orthogonal to our treatment variation of the incumbency advantage.

Taler = Experimental Currency Unit. Conversion: 20 taler = 1 EUR.

In the experiment we reversed the order in which the five options were listed on the screen in half of the sessions to control for order effects.

For this purpose the participants were invited in groups of 20 (15 in some sessions in which less than 20 participants showed up). Re-matching occurred among this larger set. For this the participants were partitioned in four subgroups of 2 politicians and 3 voters, and this partitioning was changed in each round.

We cluster standard errors at the individual level to account for subjects making the voting decision in multiple rounds. We also cluster at the experimental session level as an additional conservative estimation. The results are not qualitatively different and we report them in the appendix.

Since the data series is binary we also report a Tetrachoric correlation coefficient of 0.2158 with \(p<0.001\).

References

Alt, J., Bueno de Mesquita, E., & Shanna, R. (2011). Disentangling accountability and competence in elections: evidence from U.S. term limits. Journal of Politics, 73(1), 171–186.

Ashworth, S. (2005). Reputational dynamics and political careers. Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 21(2), 441–466.

Ashworth, S. (2012). Electoral accountability: Recent theoretical and empirical work. Annual Review of Political Science, 15, 183–201.

Ashworth, S., & Bueno de Mesquita, E. (2008). Electoral selection, strategic challenger entry, and the incumbency advantage. Journal of Politics, 70(4), 1006–1025.

Barro, R. J. (1973). The control of politicians: An economic model. Public Choice, 14(1), 19–42.

Besley, T. (2006). Principled agents? The political economy of good governance. New York: Oxford University Press.

Besley, T., & Michael, S. (2007). Fiscal restraints and voter welfare. Journal of Public Economics, 91(3–4), 755–773.

Brennan, G., & Buchanan, J. (1984). Voter choice: Evaluating political alternatives. American Behavioral Scientist, 28, 185–201.

Brennan, G., & Hamlin, A. (1998). Expressive voting and electoral equilibrium. Public Choice, 95(1), 149–175.

Brennan, G., & Lomasky, L. (1993). Democracy and decision. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buchanan, J. M., & Congleton, R. D. (1994). The incumbency dilemma and rent extraction by legislators. Public Choice, 79(1–2), 47–60.

Collier, K. E., McKelvey, R. D., Ordeshook, P. C., & Williams, K. C. (1987). Retrospective voting: An experimental study. Public Choice, 53(2), 101–130.

Dahm, M., Dur, R., & Glazer, A. (2014). How a firm can induce legislators to adopt a bad policy. Public Choice, 159(1–2), 63–82.

Dal Bó, E. (2007). Bribing voters. American Journal of Political Science, 51(4), 789–803.

Diermeier, D., & Gailmard, S. (2006). Self-interest, inequality, and entitlement in majoritarian decision-making. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 1(4), 327–350.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., Sunde, U., Schupp, J., & Wagner, G. G. (2011). Individual risk attitudes: Measurement, determinants, and behavioral consequences. Journal of the European Economic Association, 9(3), 522–550.

Erikson, R. S., & Titiunik, R. (2015). Using regression discontinuity to uncover the personal incumbency advantage. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 10(1), 101–119.

Fearon, J. D. (1999). Electoral accountability and the control of politicians: Selecting good types versus sanctioning poor performance. In A. Przeworski, S. C. Stokes, & B. Manin (Eds.), Democracy, accountability, and representation (pp. 55–97). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fearon, J. D. (2011). Self-enforcing democracy. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(4), 1661–1708.

Feltovich, N., & Giovannoni, F. (2015). Selection vs. accountability: An experimental investigation of campaign promises in a moral-hazard environment. Journal of Public Economics, 126, 39–51.

Ferejohn, J. (1986). Incumbent performance and electoral control. Public Choice, 50, 5–25.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental economics, 10(2), 171–178.

Fischer, S., & Güth, W. (2012). Effects of exclusion on acceptance in ultimatum games. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(6), 1100–1114.

Fiorina, M. P. (1978). Economic retrospective voting in American national elections—Microanalysis. American Journal of Political Science, 22(2), 426–443.

Fowler, A., & Hall, A. B. (2014). Disentangling the personal and partisan incumbency advantages: Evidence from close elections and term limits. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 9(4), 501–531.

Fox, J., & Shotts, K. W. (2009). Delegates or trustees? A theory of political accountability. Journal of Politics, 71(4), 1225–1237.

Gelman, A., & King, G. (1990). Estimating incumbency advantage without bias. American Journal of Political Science, 34(4), 1142–1164.

Greiner, B. (2004). An online recruitment system for economic experiments. In K. Kremer & V. Macho (Eds.), Forschung und wissenschaftliches Rechnen (Vol. 63, pp. 79–93). Göttingen: Ges. für Wiss. Datenverarbeitung.

Hillman, A. L. (2010). Expressive behavior in economics and politics. European Journal of Political Economy, 26(4), 403–418.

Jones, D. N., & Delroy, P. L. (2014). Introducing the short dark triad (SD3) a brief measure of dark personality traits. Assessment, 21(1), 28–41.

Kagel, J. H., & Wolfe, K. W. (2001). Tests of fairness models based on equity considerations in a three-person ultimatum game. Experimental Economics, 4(3), 203–219.

Kayser, M. A., & Peress, M. (2012). Benchmarking across borders: Electoral accountability and the necessity of comparison. American Political Science Review, 106(3), 661–684.

Kessing, S. (2010). Federalism and accountability with distorted election choices. Journal of Urban Economics, 67(2), 239–247.

Kramer, G. H. (1971). Short-term fluctuations in U.S. voting behavior, 1896–1964. American Political Science Review, 65(1), 131–143.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Stegmaier, M. (2000). Economic determinants of electoral outcomes. Annual Review of Political Science, 3, 183–219.

Lizzeri, A., & Persico, N. (2001). The provision of public goods under alternative electoral incentives. American Economic Review, 91(1), 225–239.

Marks, G., & Miller, N. (1987). Ten years of research on the false-consensus effect: An empirical and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 102(1), 72–90.

Murphy, R. O., Ackermann, K. A., & Handgraaf, M. (2011). Measuring social value orientation. Judgment and Decision Making, 6(8), 771–781.

Myerson, R. B. (1993). Incentives to cultivate favored minorities under alternative electoral systems. American Political Science Review, 87(4), 856–869.

Seabright, P. (1996). Accountability and decentralization in government: An incomplete contracts model. European Economic Review, 40, 61–89.

Snyder, J. M, Jr., & Ting, M. M. (2008). Interest groups and the electoral control of politicians. Journal of Public Economics, 92(3–4), 482–500.

Woon, J. (2012). Democratic accountability and retrospective voting: A laboratory experiment. American Journal of Political Science, 56(4), 913–930.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by the Max Planck Society. We thank two anonymous reviewers and the editor of Constitutional Political Economy, Jana Cahlikova, Sven A. Simon, our colleagues at the MPI, and the participants at the annual meeting of the European Public Choice Society, Rome, International Meeting on Experimental and Behavioral Social Sciences, Florence, Public Economic Theory conference, Hue, the Experimental Sciences Association conference, Berlin, and at a seminar at University Carlos III, Madrid for helpful comments. We thank Nina Bonge, Alexandra Kostareva, Simon Lipot, and the staff at econlab in Munich for help in running the experiments. The usual caveat applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Thoughts from a very preliminary paper entitled “Sanctioning in spite of Strong Selection Incentives” have been incorporated into this work, which thus also embeds and replaces this preliminary paper.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

This appendix offers a proof for Proposition 1. Denote by \(\lambda _{i}\) whether a voter i votes for the incumbent (\(\lambda _{i}=1\)) or for the challenger (\(\lambda _{i}=0\)). Player i chooses \(\lambda _{i}\in \{0,1\}\) that maximizes

Consider the following equilibrium candidate set of pivotality beliefs for all voters:

If voter i believes that \(\hat{p}_{i}(x_{i})>0\), he votes for the incumbent. If a voter believes that \(\hat{p}_{i}(x_{i})=0\), he may vote for the incumbent or against the incumbent, as i’s payoff is independent of i’s vote. Let the voters’ tie-breaking rule be that \(\lambda _{i}=1\) in case of indifference if \(x_{i}\ge\) 1 / n, and \(\lambda _{i}=0\) otherwise. Given this, the incumbent is re-elected if and only if she gives transfers \(x_{i}=\)\(\frac{1}{n}\) for at least n voters. Note that n such transfers just exhaust her budget for \(x_{i}=\)\(\frac{1}{n}\), that this leads to n voters who believe that they are pivotal and \(n-1\) voters who think they are not pivotal, and these pivotality beliefs are correct in the candidate equilibrium. Turn to the incumbent’s choice. The incumbent anticipates that she is re-elected if and only if she allocates \(x_{i}=1/n\) to exactly n voters. As \(b>1\) the incumbent prefers to choose \(x_{i}=\)\(\frac{1}{n}\) to precisely n voters to any other choice.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Konrad, K.A., Sherif, R. Sanctioning, selection, and pivotality in voting: theory and experimental results. Const Polit Econ 30, 330–357 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-019-09284-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-019-09284-4