Abstract

In order to produce dry and hydrophobic microfibrillated cellulose (MFC) in a simple procedure, its modification with alkyl ketene dimer (AKD) was performed. For this purpose, MFC was solvent-exchanged to ethyl acetate and mixed with AKD dissolved in the same solvent. Curing at 130 °C for 20 h under the catalysis of 1-methylimidazole yielded a dry powder. Scanning electron microscopy of the powder indicated loss in nanofibrillar structure due to aggregation, but discrete microfibrillar structures were still present. Water contact angle measurements of films produced from modified and unmodified MFC showed high hydrophobicity after AKD treatment, which persisted even after extraction with THF for 8 h. The hydrophobized MFC was characterized by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, nuclear magnetic resonance and X-ray analysis. In summary, strong indications for the presence of AKD on the surface of MFC before and after extraction with solvent were found, but only a very small amount of covalent β-ketoester linkages between the modification agent and cellulose was revealed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microfibrillated cellulose (MFC) has been discussed for many potential applications (Eichhorn et al. 2010; Dufresne 2012), among which polymer reinforcement is one of the most obvious. Because of its high strength and stiffness, high aspect ratio, web-like structure, and its bio-based and renewable characteristics, MFC has been widely used in polymer preparation as an excellent reinforcement material (Fakirov et al. 2008; Iwatake et al. 2008; Lu et al. 2008a, b; Nakagaito et al. 2009; Wang and Drzal 2012; Miao and Hamad 2013; Pandey et al. 2013). However, as demonstrated in a recent comprehensive overview, a break-through towards bulk use of MFC in polymer reinforcement has not been realized to date (Lee et al. 2014).

One major limitation to be overcome lies in the poor surface-chemical compatibility of cellulose with many widely used fossil-based consumer polymers, such as polyolefins as well as important biopolymers from renewable resources such as polylactic acid (PLA). The pronounced hydrophilicity of MFC, caused by the presence of abundant hydroxyl groups, limits its dispersibility in hydrophobic polymers and solvents (Yang et al. 2014), and subsequently entails poor reinforcement efficiency in composites. Chemical surface modification efficiently tackles this problem (Habibi 2014). Among the many different routes for surface modification reported, esterification with acetic anhydride or long chain carboxylic acids (Rodionova et al. 2010; Lee et al. 2011; Bulota et al. 2012);grafting of polymers (Lönnberg et al. 2008; Littunen et al. 2011; Missoum et al. 2012);cationization (Hasani et al. 2008; Syverud et al. 2010); silylation (Goussé et al. 2004; Andresen et al. 2006; Lu et al. 2008a, b), and TEMPO oxidation (Saito et al. 2006; Fukuzumi et al. 2009) are mentioned as important examples. Even though highly successful at the laboratory scale, the up-scaling of these wet-chemical approaches to industrial dimensions, involving partly pricey reagents and repeated solvent transfers is most probably quite cost-intensive.

Another significant obstacle for high-volume MFC application is the fact that MFC cannot be dried directly from suspension in water by simple evaporation at atmospheric pressure, because this may cause an irreversible agglomeration, also termed hornification, during drying, affecting its unique properties related to size and nanofibrillar geometry (Spence et al. 2011; Beck et al. 2012). Preparation of dry microfibrillated cellulose powder without hornification could be of great interest in industrial application. Freeze-drying represents a potential option, because it largely preserves the fibrillary structure of MFC without agglomeration during the drying process (Peng et al. 2012). Nanocellulose powder was prepared by combining freezing drying and surfactant treatment, and it was re-dispersed in PLA-chloroform solution to prepare PLA composites (Petersson et al. 2007). Drying in supercritical CO2 is also a good way to produce dry NFC, as it keeps the dimensions in nano size (Peng et al. 2012). However, both of these two methods are of high cost and impractical to scale up. By carboxymethylation and mechanical disintegration, water-redispersible MFC in powder form was prepared by Eyholzer et al. (2010). Though the MFC powder maintained its original properties, the carboxymethylated sample displayed a loss in crystallinity and a strong decrease in thermal stability.

In summary, the hydrophilicity of MFC greatly hinders its large-scale application in polymer reinforcement, as it limits dispersion and reinforcement efficiency, and prevents the production of a dry fibrillary product required for convenient industrial processing. We propose a novel approach to significantly reduce this hurdle for MFC utilization by using AKD as a modifier. In the paper industry, sizing agents such as alkyl succinic anhydride (ASA), alkyl ketene dimer (AKD) and rosin are used to provide a certain degree of hydrophobicity and printability. These components are readily available in bulk amounts at a reasonable price (Song et al. 2012). With regard to AKD, which consists of two long alkyl chains on a four-membered heterocycle, several studies concerning modification of cellulose can be found in literature (Takihara et al. 2007; Yoshida and Isogai 2007; Song et al. 2012; Yoshida et al. 2012; Yoshida and Isogai 2012). All results indicate that AKD may react with free hydroxyl groups to form β-ketoester linkages, endowing cellulose with good hydrophobicity (Fig. 1). At the same time, also adsorbed AKD, which is not covalently bonded to the cellulose matrix, may impart the same properties after thermal curing. Typically, the procedures reported involved cellulose dissolved in a lithium chloride/1, 3-dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone (LiCl/DMI) system, where subsequently reaction with AKD melt under homogeneous condition took place. Cellulose fibers were modified heterogeneously by AKD vapor redeposition (Hutton and Shen 2005; Zhang et al. 2007) or impregnated with subcritical and supercritical carbon dioxide (Hutton and Parker 2009; Russler et al. 2012). However, these treatment processes are always laborious or result in uneven AKD distribution, which may limit their suitability for scaling up in industry. In industrial paper sizing, AKD is usually applied as a suspension in cationized starch, followed by drying and curing. This procedure is not applicable to MFC, where irreversible collapse and hornification result after drying from water. In the present study, a dry hydrophobic MFC powder is produced in a simple and straightforward way from AKD in an organic solvent.

Materials and methods

Materials

Microfibrillated cellulose slurry with 3.5 wt% cellulose content was supplied by EMPA Zurich Switzerland. Elemental chlorine-free (ECF) bleached softwood-based pulp-fibres (Picea abies and Pinus spp.) were obtained from Stendal (Berlin, Germany) and used as a raw material for MFC preparation. The pulp was obtained in wet state and further diluted with water to a solid content of 2 wt%. After swelling for 24 h, cellulose fibers were grinded 10 times in a Supermass Colloider (MKZA10-20 J CE, Masuko Sangyo Co., Ltd.). During the process, grinding disks were in close contact to each other without any clearance (negative gap). AKD (Fennowax HMP, technical grade) was obtained from Kemira Chemie GesmbH, Krems, Austria. Ethyl acetate, 1-methylimidazole (MIm) and other regents or solvents were of laboratory grade supplied by Carl Roth, Austria.

Surface modification of MFC

MFC was solvent exchanged by ethanol and ethyl acetate (three times) to remove the water in the MFC slurry. The solvent exchanged MFC was filtrated resulting in a content of 12.5 wt%. Different amounts of AKD (0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0 g) were dissolved in 60 g of ethyl acetate in glass flasks at a temperature of 60 °C. 40 g of MFC suspension corresponding to 5.0 g dry MFC was added. After adding the catalyst 1-methylimidazole (1 wt% of the solution), the suspensions were homogenized using an Ultra-Turrax micro-homogenizer for 2 min. Then the mixture were transferred into glass dishes and heated to 130 °C for 20 h in the oven, resulting in a dry and fluffy MFC cake. After that the modified MFC cake was milled to powder by microfine grinder (IKA MF 10 basic). In the following, the resulting MFC samples are labelled according to the amount of AKD in g used for the modification of 5.0 g dry MFC, e.g. MFC 0.0 AKD, MFC 0.5 AKD, and so on. For a better overview, the preparation scheme of AKD modified MFC is given in Fig. 2.

Microscopy

After modification, the MFC powders treated and untreated were glued onto aluminum stubs. The samples were sputter coated with gold and observed in a Zeiss-LEO SEM in high vacuum mode at an acceleration voltage of 10 kV. In order to compare the effect of AKD modification and different drying regimes on fibril morphology, untreated MFC was left to air-dry from aqueous suspension and alternatively, a small amount of MFC suspension with 0.05 % (w/w) cellulose content was directly subjected to sputter coating without prior drying, i.e. drying was one in the sputter coating apparatus.

Contact angle measurement

Treated and untreated MFC powder was compressed in order to obtain a pellet with a smooth surface. Contact angles of sessile drops of deionized water (volume 3 µl) on the pellet surface were measured using a self-built contact angle measurement device operated with Drop Shape Analysis (DSA) for Windows 1.90 software (KR_SS Optronic, Hamburg, Germany). Five measurements were done for each sample. Measurements were taken for 120 s at 1 s intervals starting 1 s after drop placement on the pellet surface.

Attenuated total reflection infrared spectroscopy (ATR-IR)

IR spectra were recorded with a Perkin Elmer FT-IR Spectrometer Frontier equipped with a Universal ATR Sampling Accessory. Each sample was scanned in quadruplicate from 650 to 4000 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1 for 32 times.

13C CP-MAS solid-state NMR spectroscopy

Solid-state NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker Avance III HD 400 spectrometer (resonance frequency of 13C of 100.61 MHz), equipped with a 4 mm dual broadband cross-polarization magic angle spinning (CPMAS) probe. 13C spectra were acquired with the total sideband suppression (TOSS) sequence at ambient temperature with a spinning rate of 5 kHz, a cross-polarization (CP) contact time of 2 ms, a recycle delay of 2 s, SPINAL-64 1H decoupling and an acquisition time of 43 ms. Chemical shifts were referenced externally against the carbonyl signal of glycine at δ = 176.03 ppm.

X-ray analysis

X-ray powder diffractograms were obtained with a Rigaku SmartLab 5-Axis X-ray diffractometer using glass capillaries.

Results and discussion

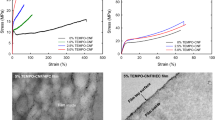

The morphology of MFC was studied by SEM imaging before and after treatment. The morphology of the raw material used for study prepared for SEM according to Ho et al. (2011) is shown in Fig. 3a. Long and thin fibrils with diameters <100 nm dominate and larger aggregations, presumably resulting from drying in the sputter coater, are infrequent. When the raw MFC was left to dry directly from aqueous suspension, a solid cellulose film formed, and MFC almost completely aggregated according to well-known phenomena observed for cellulose nanopapers (Fig. 3b). The solvent-exchange and AKD-modification of MFC, as described in the present paper resulted in a dry and fluffy powder. Figure 3c, d reveal fibrillary morphology with diameters from 100 to 800 nm for MFC dried from ethyl acetate, i.e. in the micron- rather than in the nanometer range, when one assumes a diameter threshold of 100 nm separating nanofibrils from microfibrils. No significant differences in fibril morphology were observed for the MFC types with- and without AKD treatment shown in Fig. 3c, d, respectively.

The contact angles of water on the surface of compressed pellets of MFC confirmed very significant hydrophobization due to AKD modification (Fig. 4). All modified variants showed values > 100° (Fig. 4a), and only the variant MFC 0.5 AKD gave a slight reduction in contact angle during the two minutes measurement time, indicating slight penetration of water into the MFC pellets. It should be stressed here that the pellets measured were not entirely compacted, but still porous, as confirmed by the instantaneous wetting of the variant MFC 0.0 AKD. The hydrophobization effect demonstrated here is in good agreement with- or even surpasses the values of earlier studies (Jonoobi et al. 2009; Yoshida et al. 2012; Missoum et al. 2013). The highest value of 140° for MFC 4.0 AKD even attains almost superhydrophobic character, which begins at a water-contact angle of 150° (Sousa and Mano 2013). As suggested by Song and Yang (Song et al. 2012; Yang et al. 2014) the greatly increased hydrophobicity of AKD-modified MFC may be due to the introduction of long alkyl chains of AKD on the cellulose surfaces via ketoester linkages (Fig. 1). In order to confirm stable anchoring of alkyl chains on the cellulose surface, contact angle measurements were repeated for four variants after solvent extraction with THF (Fig. 4b). Clearly, even after Soxhlet extraction for 8 h in THF, which easily dissolves unreacted AKD, the contact angles of MFC 1.0 AKD, MFC 2.0 AKD, and MFC 4.0 AKD remained at very high values and was only slightly reduced compared to the first measurement prior to extraction. Only the most gently modified variant MFC 0.5 AKD experienced a clear loss in hydrophobisation. The observation of persistent hydrophobisation in the majority of variants does not necessarily prove the formation of covalent linkages, although the apparent stability of AKD anchoring on the cellulose surface strongly points into this direction.

The infrared spectra of different MFC-AKD variants demonstrate the presence of both unreacted and reacted AKD on the surface of cellulose (Fig. 5a). The spectrum of commercial AKD shows two strong bands at 2920 and 2850 cm−1 due to stretching vibration of C-H in methylene and methyl groups. Another intensive peak at 1465 cm−1 is due to -CH2- bending. The bands at 1848 and 1721 cm−1 are the stretching peaks of the enol and carbonyl group in the lactone ring, respectively (Zhang et al. 2007; Seo et al. 2008). These bands are no longer apparent in AKD-modified MFC, indicating structural changes of AKD during MFC modification. The FT-IR spectra of AKD-modified MFC show two absorption bands at 1735 and 1710 cm−1 indicating that AKD has reacted with MFC hydroxyl groups forming the corresponding β-keto ester. These absorption bands, which increase in intensity with increasing amounts of AKD involved in the modification procedure, prove the ring opening of AKD and are indicative of covalent bonding with the cellulose surface (Song et al. 2012). In parallel, absorption bands at 1467 and 720 cm−1 associated with -CH- stretching and deformation vibrations of alkyl chains (Yoshida et al. 2005; Zhang et al. 2007), also appear and increase in intensity with increasing amount of AKD. These changes in the infrared spectra of MFC indicate that AKD was consumed during the reaction and at least partly bonded covalently via by esterification. As mentioned above (Fig. 5b), for the MFC 4.0 AKD variant prior to- and after extraction with THF, characteristic absorption bands persist after extraction, albeit at diminished intensity. It may thus be concluded that not covalently attached AKD is removed by THF extraction, whereas significant hydrophobization still persists due to the alkyl chains of covalently linked AKD on the cellulose surface.

The dried samples AKD, pure MFC, MFC 1.0 AKD, MFC 2.0 AKD, and MFC 4.0 AKD were further characterized by high resolution solid state NMR to assess potential reaction between cellulose and AKD. The peaks of the anhydrosugar unit of cellulose are assigned as shown in Fig. 6, 105 ppm for C1, 88.9 ppm for C4cryst, 83 ppm for C4amorph, 79–68 ppm region for C2, C3, C5, 65 ppm for C6cryst, and 62.5 ppm for C6amorph. The intensity ratio of C4cryst/C4amorph indicated that MFC still has high crystallinity after hydrophobization. The chemical shifts at 14.3 ppm and 30.3 ppm are assigned to methyl and methylene groups of AKD, respectively. 13C CP/MAS NMR of three hydrophobized products qualitatively shows a low degree of substitution (~ 0.02). The broad peak around 170–175 ppm, only slightly visible in the MFC 4.0 AKD sample with the highest AKD load, corresponds to the ester carbonyl in AKD and is indicative of both a covalent linkage and different environments of the bound ester groups.

Chemical modification of cellulose can decrease its crystallinity (Sassi and Chanzy 1995) leading to a possible reduction of its reinforcing potential in composites with polymers. As shown in Fig. 6, NMR hints at persistent crystallinity also after AKD treatment of MFC. The X-ray diffractograms shown in Fig. 7 do not provide any contrary indication, but a detailed analysis of cellulose crystallinity in the case of MFC-AKD mixtures is difficult. Unreacted dry AKD is highly crystalline and shows a characteristic diffraction pattern with strong diffraction peaks. Similarly, untreated MFC shows the well-known diffraction pattern of cellulose I, with the most intense diffraction peak originating from the cellulose I (200) crystal plane. Upon hydrophobization with AKD, the diffraction pattern changes significantly. Close inspection reveals a small shoulder at a diffraction angle of 21.5°, which is very slight in MFC 0.5 AKD and MFC 1.0 AKD, but turns into a clear peak in MFC 2.0 AKD and MFC 4.0 AKD, respectively. The diffraction peak may be attributed to the presence of solid unreacted AKD on the surface of MFC, which is confirmed by the fact that this peak completely disappears after extraction with THF. In fact, the diffraction pattern of extracted MFC 4.0 AKD is identical with the diffraction pattern of untreated MFC. This indicates that unreacted material is largely removed upon extraction with THF. AKD-treated MFC shows overlapping diffraction peaks of both cellulose and AKD, which is the reason why crystallinity cannot be easily estimated, e.g. according to the method of Segal et al. (1959). Tentatively, the height of the cellulose 004 diffraction peak at 34° was examined, since AKD does not exhibit diffraction in this region, but no indication of changes in crystallinity was found. A detailed analysis of the MFC 4.0 AKD sample prior-to and after extraction of unreacted AKD confirms the first impression of no significant effect of AKD modification on MFC crystallinity. Using the peak height method of Segal et al. (1959), an crystallinity index of 0.60 ± 0.018 is obtained for MFC 0.0 AKD compared to 0.59 ± 0.018 for extracted MFC 4.0 AKD. The preservation of cellulose crystallinity may be interpreted indicative of AKD only reacting with the surface of MFC and not being detrimental to the cellulose crystal structure.

Conclusion

The results shown above demonstrate that highly hydrophobic MFC powder can be obtained in a simple procedure using the common paper sizing agent AKD. Since only small amounts of AKD are covalently bonded to the cellulose surface, hydrophobicity is mostly imparted by physically adsorbed sizing agent. While a clear loss in nano-scale morphology presents an important disadvantage of the method, fibrillary—as opposed to particulate as obtained in spray drying—structure paired with hydrophobicity and availability in dry powder form present attractive features with regard to applications such as polymer reinforcement.

References

Andresen M, Johansson L-S, Tanem BS, Stenius P (2006) Properties and characterization of hydrophobized microfibrillated cellulose. Cellulose 13(6):665–677

Beck S, Bouchard J, Berry R (2012) Dispersibility in water of dried nanocrystalline cellulose. Biomacromolecules 13(5):1486–1494

Bulota M, Kreitsmann K, Hughes M, Paltakari J (2012) Acetylated microfibrillated cellulose as a toughening agent in poly(lactic acid). J Appl Polym Sci 126(S1):E449–E458

Dufresne A (2012) Nanocellulose: from nature to high performance tailored materials. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin

Eichhorn S, Dufresne A, Aranguren M, Marcovich N, Capadona J, Rowan S, Weder C, Thielemans W, Roman M, Renneckar S (2010) Review: current international research into cellulose nanofibres and nanocomposites. J Mater Sci 45(1):1–33

Eyholzer C, Bordeanu N, Lopez-Suevos F, Rentsch D, Zimmermann T, Oksman K (2010) Preparation and characterization of water-redispersible nanofibrillated cellulose in powder form. Cellulose 17(1):19–30

Fakirov S, Bhattacharyya D, Shields RJ (2008) Nanofibril reinforced composites from polymer blends. Colloids Surf A 313–314:2–8

Fukuzumi H, Saito T, Iwata T, Kumamoto Y, Isogai A (2009) Transparent and high gas barrier films of cellulose nanofibers prepared by TEMPO-mediated oxidation. Biomacromolecules 10(1):162–165

Goussé C, Chanzy H, Cerrada ML, Fleury E (2004) Surface silylation of cellulose microfibrils: preparation and rheological properties. Polymer 45(5):1569–1575

Habibi Y (2014) Key advances in the chemical modification of nanocelluloses. Chem Soc Rev 43(5):1519–1542

Hasani M, Cranston ED, Westman G, Gray DG (2008) Cationic surface functionalization of cellulose nanocrystals. Soft Matter 4(11):2238

Ho TTT, Zimmermann T, Hauert R, Caseri W (2011) Preparation and characterization of cationic nanofibrillated cellulose from etherification and high-shear disintegration processes. Cellulose 18(6):1391–1406

Hutton BH, Parker IH (2009) A surface study of cellulose fibres impregnated with alkyl ketene dimers via subcritical and supercritical carbon dioxide. Colloids Surf A 334(1–3):59–65

Hutton B, Shen W (2005) Sizing effects via AKD vaporisation. Appita J 58(5):367–373

Iwatake A, Nogi M, Yano H (2008) Cellulose nanofiber-reinforced polylactic acid. Compos Sci Technol 68(9):2103–2106

Jonoobi M, Harun J, Mathew AP, Hussein MZB, Oksman K (2009) Preparation of cellulose nanofibers with hydrophobic surface characteristics. Cellulose 17(2):299–307

Lee K-Y, Quero F, Blaker JJ, Hill CAS, Eichhorn SJ, Bismarck A (2011) Surface only modification of bacterial cellulose nanofibres with organic acids. Cellulose 18(3):595–605

Lee K-Y, Aitomäki Y, Berglund LA, Oksman K, Bismarck A (2014) On the use of nanocellulose as reinforcement in polymer matrix composites. Compos Sci Technol 105:15–27

Littunen K, Hippi U, Johansson L-S, Österberg M, Tammelin T, Laine J, Seppälä J (2011) Free radical graft copolymerization of nanofibrillated cellulose with acrylic monomers. Carbohydr Polym 84(3):1039–1047

Lönnberg H, Fogelström L, Berglund L, Malmström E, Hult A (2008) Surface grafting of microfibrillated cellulose with poly(ε-caprolactone)—synthesis and characterization. Eur Polym J 44(9):2991–2997

Lu J, Askeland P, Drzal LT (2008a) Surface modification of microfibrillated cellulose for epoxy composite applications. Polymer 49(5):1285–1296

Lu J, Wang T, Drzal LT (2008b) Preparation and properties of microfibrillated cellulose polyvinyl alcohol composite materials. Compos A 39(5):738–746

Miao C, Hamad WY (2013) Cellulose reinforced polymer composites and nanocomposites: a critical review. Cellulose 20(5):2221–2262

Missoum K, Bras J, Belgacem MN (2012) Organization of aliphatic chains grafted on nanofibrillated cellulose and influence on final properties. Cellulose 19(6):1957–1973

Missoum K, Martoïa F, Belgacem MN, Bras J (2013) Effect of chemically modified nanofibrillated cellulose addition on the properties of fiber-based materials. Ind Crops Prod 48:98–105

Nakagaito AN, Fujimura A, Sakai T, Hama Y, Yano H (2009) Production of microfibrillated cellulose (MFC)-reinforced polylactic acid (PLA) nanocomposites from sheets obtained by a papermaking-like process. Compos Sci Technol 69(7–8):1293–1297

Pandey JK, Nakagaito AN, Takagi H (2013) Fabrication and applications of cellulose nanoparticle-based polymer composites. Polym Eng Sci 53(1):1–8

Peng Y, Gardner DJ, Han Y (2012) Drying cellulose nanofibrils: in search of a suitable method. Cellulose 19(1):91–102

Petersson L, Kvien I, Oksman K (2007) Structure and thermal properties of poly(lactic acid)/cellulose whiskers nanocomposite materials. Compos Sci Technol 67(11–12):2535–2544

Rodionova G, Lenes M, Eriksen Ø, Gregersen Ø (2010) Surface chemical modification of microfibrillated cellulose: improvement of barrier properties for packaging applications. Cellulose 18(1):127–134

Russler A, Wieland M, Bacher M, Henniges U, Miethe P, Liebner F, Potthast A, Rosenau T (2012) AKD-Modification of bacterial cellulose aerogels in supercritical CO2. Cellulose 19(4):1337–1349

Saito T, Nishiyama Y, Putaux JL, Vignon M, Isogai A (2006) Homogeneous suspensions of individualized microfibrils from TEMPO-catalyzed oxidation of native cellulose. Biomacromolecules 7(6):1687–1691

Sassi J-F, Chanzy H (1995) Ultrastructural aspects of the acetylation of cellulose. Cellulose 2(2):111–127

Segal L, Creely JJ, Martin AE, Conrad CM (1959) An empirical method for estimating the degree of crystallinity of native cellulose using the X-ray diffractometer. Text Res J 29:786–794

Seo WS, Cho NS, Ohga S (2008) Possibility of Hydrogen Bonding between AKD and Cellulose Molecules during AKD Sizing. J Fac Agric Kyushu Univ 53(2):405–410

Song X, Chen F, Liu F (2012) Preparation and characterization of alkyl ketene dimer (AKD) modified cellulose composite membrane. Carbohydr Polym 88(2):417–421

Sousa MP, Mano JF (2013) Patterned superhydrophobic paper for microfluidic devices obtained by writing and printing. Cellulose 20(5):2185–2190

Spence K, Habibi Y, Dufresne A (2011) Nanocellulose-based composites. Cellulose fibers: bio-and nano-polymer composites. Springer, Berlin, pp 179–213

Syverud K, Xhanari K, Chinga-Carrasco G, Yu Y, Stenius P (2010) Films made of cellulose nanofibrils: surface modification by adsorption of a cationic surfactant and characterization by computer-assisted electron microscopy. J Nanopart Res 13(2):773–782

Takihara T, Yoshida Y, Isogai A (2007) Reactions between cellulose diacetate and alkenylsuccinic anhydrides and characterization of the reaction products. Cellulose 14(4):357–366

Wang T, Drzal LT (2012) Cellulose-nanofiber-reinforced poly(lactic acid) composites prepared by a water-based approach. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 4(10):5079–5085

Yang Q, Takeuchi M, Saito T, Isogai A (2014) Formation of nanosized islands of dialkyl beta-ketoester bonds for efficient hydrophobization of a cellulose film surface. Langmuir 30(27):8109–8118

Yoshida Y, Isogai A (2007) Preparation and characterization of cellulose β-ketoesters prepared by homogeneous reaction with alkylketene dimers: comparison with cellulose/fatty acid esters. Cellulose 14(5):481–488

Yoshida Y, Isogai A (2012) Nanofibrillation of alkyl ketene dimer (AKD)-treated cellulose in tetrahydrofuran. Cellulose 20(1):3–7

Yoshida Y, Yanagisawa M, Isogai A, Suguri N, Sumikawa N (2005) Preparation of polymer brush-type cellulose β-ketoesters using LiCl/1,3-dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone as a solvent. Polymer 46(8):2548–2557

Yoshida Y, Heux L, Isogai A (2012) Heterogeneous reaction between cellulose and alkyl ketene dimer under solvent-free conditions. Cellulose 19(5):1667–1676

Zhang H, Kannangara D, Hilder M, Ettl R, Shen W (2007) The role of vapour deposition in the hydrophobization treatment of cellulose fibres using alkyl ketene dimers and alkenyl succinic acid anhydrides. Colloids Surf A 297(1–3):203–210

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful for financial support from Special Fund for Forestry Research in the Public Interest (Project 201204702) and the support from the China Scholarship Council (CSC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, Y., Amer, H., Rosenau, T. et al. Dry, hydrophobic microfibrillated cellulose powder obtained in a simple procedure using alkyl ketene dimer. Cellulose 23, 1189–1197 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-016-0887-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-016-0887-0