Abstract

Semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs) in estuarine waters can adversely affect biota but watershed sources can be difficult to identify because these compounds are transient. Natural bacterial assemblages may respond to chronic, episodic exposure to SVOCs through selection of more organotolerant bacterial communities. We measured bacterial production, organotolerance and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) mineralization in Charleston Harbor and compared surface sediment from stations near a known, permitted SVOC outfall (pulp mill effluent) to that from more pristine stations. Naphthalene additions inhibited an average of 77% of bacterial metabolism in sediments from the more pristine site (Wando River). Production in sediments nearest the outfall was only inhibited an average of 9% and in some cases, was actually stimulated. In general, the stations with the highest rates of bacterial production also were among those with the highest rates of PAH mineralization. This suggests that the capacity to mineralize PAH carbon is a common feature amongst the bacterial assemblage in these estuarine sediments and could account for an average of 5.6% of bacterial carbon demand (in terms of production) in the summer, 3.3% in the spring (April) and only 1.2% in winter (December).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Natural bacterial assemblage composition is a result of numerous environmental factors and stressors, including the presence of semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs), which can disrupt bacterial cell membranes and cause cell damage or death (see review by Beney and Gervais 2001). Bacteria can compensate for the presence of these compounds by decreasing cell membrane fluidity, which reduces disruption by organic compounds and thereby increases organotolerance (Beney and Gervais 2001). Although membrane fluidity can be altered by the bacterium, sudden changes in the SVOC concentration may cause a temporary reduction in the metabolic rate of cells that are not adapted to elevated organic levels (Beney and Gervais 2001). Conversely, a bacterial assemblage that is chronically exposed to SVOCs may be less likely to be metabolically affected by abrupt change in organic concentration. Metabolic rate of the heterotrophic assemblage, also called bacterial production, is commonly measured using the leucine incorporation assay (Kirchman et al. 1985; Smith and Azam 1992; Kirchman 1993). In addition to its widespread use in marine microbial ecology, bacterial production has been used to evaluate hydrocarbon biodegradation strategies in groundwater (Holm et al. 1992; Jensen 1989; Boyd et al. 2001, 2002; Montgomery et al. 2002), bilgewater (Stamper and Montgomery 2008), estuarine sediments (Boyd et al. 2005, 2008; Montgomery et al. 2008) and wastewater inputs into groundwater (Harvey and George 1987; Harvey et al. 1984).

SVOC exposure may affect metabolism among some components of the bacterial assemblage in submerged sediments (Godoy et al. 1998; Castle et al. 2006; Gomes et al. 2007). In estuaries, these compounds are often associated with surface water release of fresh petroleum fuels, atmospheric fallout, storm water runoff and occasionally intrusion of contaminated groundwater into the submerged sediments. Inputs to the surface water can interact with surface sediments via deposition of organics on particles, resuspension, or through reworking of sediments by benthic macrofauna that increases contact with the water column. Due to rapid abiotic and biotic losses of volatile compounds from the system, SVOC-impacted sediments might be expected to be closer to the input source than those sediments impacted by less volatile PAH, like phenanthrene and fluoranthene.

Naphthalene is one of the most common SVOC in estuarine systems owing to its association with petroleum fuels, combustion activities and many industrial processes. Despite its ubiquity in anthropogenically influenced systems (Kastner et al. 1994), naphthalene is often transient as it is metabolized by many types of natural bacteria and is more water soluble and volatile than many other petroleum compounds. This two-ringed hydrocarbon can rapidly transfer out of an estuarine system into the atmosphere (Gustafson and Dickhut 1997), so it is more likely to reflect a current petroleum source than a more weathered product input (Arzayus et al. 2001). The presence of naphthalene can reduce bacterial diversity (Nyman 1999), increase the relative abundance of naphthalene degraders (Castle et al. 2006), and inhibit bacterial production, even among strains that metabolize higher molecular weight PAH (Bouchez et al. 1995; Lantz et al. 1997). These characteristics may allow for the identification of sediments that are chronically subjected to SVOC inputs.

We compared the effect of naphthalene addition on bacteria collected from sediment chronically exposed to SVOCs from a Cooper River permitted outfall with sediment from less exposed areas of Charleston Harbor estuary, a coastal plain estuary formed at the confluence of three rivers, Cooper, Ashley and Wando. It was expected that the bacterial assemblage in surface sediments with chronic exposure to an outfall permitted for release of SVOCs and other low molecular weight organics would be less metabolically inhibited by naphthalene additions than those from more pristine areas.

Materials and methods

Study site and collection methods

The Charleston Harbor survey involved seasonal sampling of twenty-two stations throughout the harbor and the three major source waters, the Ashley, Wando and Cooper Rivers (Fig. 1). A standard shipboard CTD rosette with three 10-L Niskin collection bottles on board the R/V Cape Hatteras was used to collect water samples and measure temperature and salinity. Bottom water for the bacterial production and PAH mineralization assays was collected from one meter above the sediment–water interface. Water was subsampled using acid-cleaned 500 mL amber glass bottles with Teflon®-lined closures and then transferred to onboard laboratory facilities for processing within minutes of collection for biological analysis. Surface sediment (top 2 cm) was collected using a Shipek benthic grab, transferred to 50 mL centrifuge tubes and immediately subsampled for production and mineralization assays. Surveys were performed during three research cruises in August and December 1998 and April 1999. Possible sources of SVOCs to the estuarine surface sediments are the numerous industries along the waterway including a petroleum storage facility and paper mill, as well as non-point sources such as ship traffic, storm water outfalls and surface runoff (Van Dolah et al. 1990). The paper mill (adjacent to station 4) has an outfall permitted to discharge 20 million gallons per day of organic-rich effluent (Van Dolah et al. 1990).

Bacteria production

A 50 μl sample of wet sediment was subsampled from each station and added to 2.0 mL microcentrifuge tubes (three experimental and one killed control) sealed with a cap with an O-ring and pre-charged with [3H-4,5]-L-leucine (154 mCi mmol−1, final concn. 20 nM). The sediment was extracted from the sample using a 1 mL polypropylene syringe with the end cut off and then added to the assay tube. One mL of 0.22 μm (nom. pore dia.) filtered bottom water was then added to each tube and vortexed to form a sediment slurry. Samples were incubated at in situ temperature for two hours. Incubations were ended by adding 57 μl of 100% trichloroacetic acid (5% final concentration; TCA, Fisher Scientific) and frozen for storage prior to processing by the method of Smith and Azam (1992). Killed controls had the TCA added prior to the addition of the sample and their values were subtracted from those of the experimental samples. A constant isotope dilution factor of two was used for all samples and was estimated from sediment dissolved free amino acids measurements (Burdige and Martens 1990) and saturation experiments (Tuominen 1995). Triplicate one mL syringed samples of wet sediment were dried (overnight; 21°C) and used to covert production values into dry weight from wet volume (0.05 mL). Leucine incorporation rate was converted to bacterial carbon using the formula of Simon and Azam (1989) (detection limit: 1.0 μg C kg−1 day−1).

Bacterial organotolerance

Naphthalene organotolerance of the natural bacterial assemblage was measured by adding 0, 5, 15 or 25 μg of naphthalene dissolved in 5 μl of methanol to 0.50 μl of wet sediment and subsequently processing for bacterial production. All treatments and controls received the same addition of methanol (5 μl) though preliminary experiments showed that production was not affected in parallel incubations with methanol alone. The 5 μl of methanol with dissolved naphthalene was added to the microcentrifuge tube prior to sample addition. Average and standard deviation of the three live incubations (with value for the killed control subtracted) were regressed to the amount of naphthalene added to the leucine incorporation assay. Bacterial production values were converted to dry weight by drying triplicate subsamples of 1.0 mL wet volume of sediment (overnight; 21°C). Final concentration of naphthalene in the 25 μg addition was ca. 250 μg g−1 sediment (dry weight). The regression formula and r 2 value were calculated using Microsoft Excel®.

PAH mineralization

PAH mineralization assays were initiated within 3 h of sediment sample collection using a modification of Boyd et al. (2005) and Pohlman et al. (2002). Three sentinel PAHs (Sigma) were used as radiotracers: UL-14C-naphthalene (specific activity: 18.6 mCi mmol−1), 3-14C-fluoranthene (45 mCi mmol−1), and 9-14C-phenanthrene (55.7 mCi mmol−1). They were added in separate incubations (triplicate live samples and one killed control) to sediment samples (1 cm3 wet volume) in 100 × 16 mm polystyrene test tubes to a final concentration of ca. 0.2 μg g−1 (depending on specific activity). Filtered (0.22 μm nom. pore dia.) bottom water (0.5 mL) was mixed with the sediment to form slurry. Isotope dilution was calculated from the ambient PAH concentration which was determined using EPA SW 8270 method for 18 priority pollutants (Fisher et al. 1997) with a detection limit of 0.01 μg g−1. Sample incubations were held to 24 h at in situ temperature to minimize bacterial assemblage change, and evolved 14CO2 was captured on NaOH-soaked filter papers. H2SO4 was added to end incubations and to partition any remaining CO2 into headspace of the tube and ultimately to the filter paper trap. Killed control samples were used as a control for volatilization of naphthalene into the headspace and partitioning onto the NaOH trap. Values for killed controls were subtracted from those for live samples. The filter paper traps containing metabolized 14CO2 were removed, radioassayed and then used to calculate substrate mineralization (detection limit: 0.01 μg C kg−1 day−1).

Results

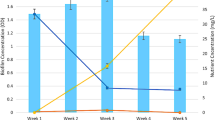

Growth rate of the natural bacterial assemblage (bacterial production) was highest in August (range: 31–630 μg C kg−1 day−1) and lowest in December (range: 13–120 μg C kg−1 day−1) (Table 1). Of the stations sampled in August, production was highest at Shipyard Creek (stations 10–12; 180–630 μg C kg−1 day−1) and at most upriver station in the Cooper River (station 1; 310 μg C kg−1 day−1), and lowest near a pulp mill outfall at station 4 (31 ± 5 μg C kg−1 day−1). Similarly, mineralization rates for the PAHs, naphthalene (range: 5.7–11 μg C kg−1 day−1), phenanthrene (range: 7.7–18 μg C kg−1 day−1) and fluoranthene (range: 2.8–14 μg C kg−1 day−1) were also highest at these stations during the August sampling. In general, the stations with the highest rates of bacterial production also were among those with the highest rates of PAH mineralization (Fig. 2). This suggests that the capacity to mineralize PAH carbon is a common feature amongst the bacterial assemblage in these estuarine sediments and could account for an average of 5.6% of bacterial carbon demand (in terms of production) in the summer, 3.3% in the spring (April) and only 1.2% in winter (December) (Table 2).

Due to their transient nature, volatile and semi-volatile organic matter discharge to estuarine surface waters may not lead to sediment accumulation. Average naphthalene concentrations in the sediments ranged from below detection limit to 0.12 μg g−1 (Table 1). Assemblages from relatively pristine areas of the estuary were dramatically inhibited (station A2: 70–86% at 25 μg addition, Table 3). In contrast, adding naphthalene to sediments from nearest to an industrial outfall (station 4) inhibited bacterial production to a lesser extent (25–34% at 25 μg addition) and even showed some stimulation of production (−32%, Table 3).

Values for inhibition of bacterial productivity for the highest naphthalene addition (25 μg) were averaged for each station and compared with distance from the permitted SVOC outfall. Stations adjacent to the Charleston Navy Yard (CNY; 6A–E) were near to each other and were grouped, as were stations from Shipyard Creek (stations 10–12; Fig. 1). Station 4 which is closest to the outfall had the lowest average effect of naphthalene on production (9% inhibition), followed by the nearest stations, 5 and 3, and then the stations (2 and 3 km away), 2 and 6A–E (Table 4). Stations greater than 2 km upriver (1 and 2) and greater than 3 km downriver (10 to A1) were inhibited by 57% or greater (Table 4). Bacterial assemblages from the less-industrialized Wando station A2 (11 km downriver from station 4) were most sensitive to the naphthalene additions (averaging 77% inhibition, Table 4).

Discussion

SVOCs and other low molecular weight organics are transient in estuarine ecosystems making it difficult to identify impacted sediments. In this study, naphthalene concentrations in surface sediments were low, ranging from below detection limit to 0.22 μg g−1 for all stations from the three cruises, relative to the creeks and tributaries feeding the estuary (Sanger et al. 1999). Although these compounds are short lived in estuarine sediments, their effect on individual bacterial cells can be immediate and can last well after the SVOC concentrations have diminished. SVOCs, including naphthalene, can disrupt and destabilize the outer membrane of estuarine bacteria causing cell damage and death (Beney and Gervais 2001). Some strains of bacteria can compensate through various strategies including decreasing membrane fluidity through cis to trans isomerization of unsaturated fatty acids in the bacterial membrane (Loffeld and Keweloh 1996; Morita et al. 1993) or changes in polar head group composition (Beney and Gervais 2001). Other strategies involve the use of efflux pumps in the bacterial cell membrane which regulate the rate and amount of PAHs entering the cell through passive diffusion (Bugg et al. 2000) though such pumps are not necessarily used for naphthalene (Isken and de Bont 1996; Kieboom et al. 1998; Hearn et al. 2003). These solvent efflux pumps are also reported to enhance antibiotic resistance (Fernandes et al. 2003; Muller et al. 2007). Once the immediate threat of cell lysis has been overcome, bacterial strains that can catabolize the volatile organic or associated carbon sources would have a selective advantage over noncatabolizing components of the assemblage (Hayes et al. 1999). The time scales for recovery of the assemblage back to organosensitive strains is more poorly understood but may be based on protist grazing rate on bacteria (Tso and Taghon 2006), competition for nutrients, or selective pressure from normal seasonal fluctuations or other extreme environmental conditions like high organic matter concentrations (Morrison and Alexander 1997).

This study used naphthalene additions to the standard assay for bacterial production to quantify the sensitivity of natural bacteria assemblages to SVOC exposure. Naphthalene additions are known to inhibit bacteria production (Hudak et al. 1988), thus organotolerant strains may contribute disproportionately to measured heterotrophic production in the presence of elevated naphthalene concentrations. The assay was performed on surface sediments at 12 stations throughout the Charleston Harbor estuarine over the course of three sampling events in 1998 and 1999. The primary comparison was between sediments nearest an industrial wastewater outfall and the relatively pristine area in the Wando River.

Bacterial production in sediments from the Wando River were inhibited by >70% at the highest naphthalene addition (25 μg to the assay is equivalent to about 250 μg g−1) and the inhibition was often linear with increasing naphthalene concentration. Sedimentary assemblages closest to the outfall (station 4) in the Cooper River were much less inhibited by naphthalene addition (<50% of production) with the metabolism at one sampling actually being stimulated by the naphthalene addition. The effect of naphthalene on production in stations upriver and downriver of the outfall was variable but generally, there was greater inhibition with distance from the outfall. The Cooper River is a tidally influenced system with a well-defined salt wedge and little net flow into the harbor for most of the year (Van Dolah et al. 1990). As such, most of the impact of outfall effluent would be expected in stations nearest to the outfall at both upriver and downriver stations.

We did not find a relationship between organotolerance to naphthalene (effect of production) and mineralization of naphthalene. Absence of this relationship has also been reported for other organic solvents (e.g., toluene) with other Gram-negative bacteria (Mosqueda et al. 1999; Matsumoto et al. 2002) and with marine bacterial isolates (Segura et al. 2008). Though naphthalene mineralization rates were not found to be a good indicator of naphthalene exposure, the ratio of naphthalene mineralization to production might be used to identify sediments that were acting as relative sinks for PAHs. Though the presence of naphthalene may select for organotolerant assemblages, the total naphthalene flux to the sediment may not be enough (relative to other organic carbon sources) to account for a large component of total bacterial metabolism. We found that naphthalene mineralization supported less than 1% of total production in most sediment. Naphthalene may be a good surrogate for SVOCs in terms of disruption of bacterial outer membranes, but the specificity of bacterial enzymatic systems (Powell et al. 2008) suggests it is not a good surrogate for SVOCs as a carbon source. A better indication of the importance of PAH carbon as a proportion of the total microbial carbon demand may be phenanthrene and fluoranthene mineralization, which (summed with naphthalene mineralization) on average supported 5.6% of bacterial carbon demand in the summer, 3.3% in the spring, but only 1.2% in winter. This reduction during winter was the opposite of that reported by Boyd et al. (2001) for freshwater sediment in the Philadelphia Reserve Basin (near confluence of the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers). Boyd et al. (2001) noted that the difference corresponded to lower oxygen levels in the basin bottom water during the summer that depressed PAH mineralization rates. Although oxygen depletion has been reported for the Cooper River during the summer, it may not have been low enough to control seasonal PAH metabolism during this study.

References

Arzayus KM, Dickhut RM, Canuel EA (2001) Fate of atmospherically deposited polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Chesapeake Bay. Environ Sci Technol 35:2178–2183

Beney L, Gervais P (2001) MINIREVIEW: influence of the fluidity of the membrane on the response of microorganisms to environmental stress. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 57:34–42

Bouchez M, Blanchet D, Vandecasteele JP (1995) Degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by pure strains and by defined strain association: inhibition phenomena and cometabolism. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 43(1):156–164

Boyd TJ, Montgomery MT, Spargo BJ, Smith DC, Coffin RB, Kelley CA, Mueller JG (2001) Effects of oxygenation on hydrocarbon biodegradation in a hypoxic environment. Bioremed J 5(2):145–157

Boyd TJ, Montgomery MT, Coffin RB, Reatherford SR, Badger CV (2002) Characterization of intrinsic PAH bioremediation in groundwater during tidal cycles at the Naval Station Norfolk: interim report. US Naval Research Laboratory Formal Report, NRL/FR/6110–02-10,029

Boyd TJ, Montgomery MT, Steele JK, Pohlman JW, Reatherford SR, Spargo BJ, Smith DC (2005) Dissolved oxygen saturation controls PAH biodegradation in freshwater estuary sediments. Microb Ecol 49(2):226–235. doi:10.1007/s00248-004-0279-0. PMID:15965718

Boyd TJ, Smith DC, Apple JK, Hamdan LJ, Osburn CL, Montgomery MT (2008) Evaluating PAH biodegradation relative to bacterial carbon demand in coastal ecosystems: Are PAHs truly recalcitrant? In: Van Dijk T (ed) Microbial Ecology Research Trends. NOVA Science Publishers Inc, Hauppauge, NY, pp 1–38

Bugg T, Foght JM, Pickard MA, Gray MR (2000) Uptake and active efflux of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by Pseudomonas fluorescens LP6a. Appl Environ Microbiol 66(12):5387–5392

Burdige DJ, Martens CS (1990) Biogeochemical cycling in an organic-rich marine basin-11. The sedimentary cycling of dissolved free amino acids. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 54:3033–3052

Castle DM, Montgomery MT, Kirchman DL (2006) Effects of naphthalene on microbial community composition in the Delaware estuary. FEMS Microb Ecol 56:55–63

Fernandes P, Ferreira BS, Cabral JMS (2003) Solvent tolerance in bacteria: role of efflux pumps and cross-resistance with antibiotics. Int J Antimicrob Agents 22:211–216

Fisher JA, Scarlett MJ, Stott AD (1997) Accelerated solvent extraction: an evaluation for screening of soils for selected US EPA semivolatile organic priority pollutants. Environ Sci Technol 31:1120–1127

Godoy F, Zenteno P, Cerda F, Gonzalex B, Martinez M (1998) Tolerance to trichlorophenols in microorganisms from a polluted and a pristine site of a river. Chemosphere 38(3):655–662

Gomes NCM, Borges LR, Paranhos R, Pinto FN, Krogerrecklenfort E, Mendonca-Hagler LCS, Kornelia S (2007) Diversity of ndo genes in mangrove sediments exposed to different sources of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon pollution. Appl Environ Microbiol 73(22):7392–7399

Gustafson KE, Dickhut RM (1997) Gaseous exchange of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons across the air–water interface of southern Chesapeake Bay. Environ Sci Technol 31:1623–1629

Harvey RW, George LH (1987) Growth determinations for unattached bacteria in a contaminated aquifer. Appl Environ Microbiol 53(12):2992–2996

Harvey RW, Smith RL, George LH (1984) Effect of organic contamination upon microbial distributions and heterotrophic uptake in a Cape Cod, Mass., aquifer. Appl Environ Microbiol 48(6):1197–1202

Hayes LA, Nevin KP, Lovley DR (1999) Role of prior exposure on anaerobic degradation of naphthalene and phenanthrene in marine harbor sediments. Org Geochem 30:937–945

Hearn EM, Dennis JJ, Gray MR, Foght JM (2003) Identification and characterization of the emhABC efflux system for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in Pseudomonas fluorescens cLP6a. J Bacteriol 185(21):6233–6240

Holm PE, Nielsen PH, Albrechtsen H-J, Christensen TH (1992) Importance of unattached bacteria and bacteria attached to sediment in determining potentials for degradation of xenobiotic organic contaminants in an aerobic aquifer. Appl Environ Microbiol 58(9):3020–3026

Hudak JP, McDaniel J, Lee S, Fuhrman JA (1988) Mineralization potentials of aromatic-hydrocarbons by estuarine microorganisms—variations with season, location, and bacterioplankton production. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 47:97–102

Isken S, de Bont JA (1996) Active efflux of toluene in a solvent-resistant bacterium. J Bacteriol 178(20):6056–6058

Jensen BK (1989) ATP-related specific heterotrophic activity in petroleum contaminated and uncontaminated groundwater. Can J Microbiol 35:814–818

Kastner M, Breuerjammali M, Mahro B (1994) Enumeration and characterization of the soil microflora from hydrocarbon-contaminated soil sites able to mineralize polycyclic aromatic-hydrocarbons (PAH). Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 41:267–273

Kieboom J, Dennis JJ, de Bont JA, Zylstra GJ (1998) Identification and molecular characterization of an efflux pump involved in Pseudomonas putida S12 solvent tolerance. J Biol Chem 273(1):85–91

Kirchman DL (1993) Leucine incorporation as a measure of biomass production by heterotrophic bacteria. In: Kemp PF, Sherr BF, Sherr EB, Cole JJ (eds) Handbook of methods in aquatic microbial ecology. Lewis Publishers, Ann Arbor, pp 509–512

Kirchman DL, K’Nees E, Hodson R (1985) Leucine incorporation and its potential as a measure of protein synthesis by bacteria in natural aquatic systems. Appl Environ Microbiol 49:599–607

Lantz SE, Montgomery MT, Schultz WW, Pritchard PH, Spargo BJ, Mueller JG (1997) Constituents of organic wood preservatives that inhibit the fluoranthene degrading activity of bacterial strain Sphingomonas paucimobilis Strain EPA505. Environ Sci Technol 31:3573–3580

Loffeld B, Keweloh H (1996) Cis/trans isomerization of unsaturated fatty acids as possible control mechanism of membrane fluidity in Pseudomonas putida P8. Lipids 31:811–815

Matsumoto M, de Bont JAM, Isken S (2002) Isolation and characterization of the solvent-tolerant Bacillus cereus strain R1. J Biosci Bioengin 94:45–51

Montgomery MT, Spargo BJ, Mueller JG, Coffin RB, Smith DC, Boyd TJ (2002) Bacterial production stimulated across the zone of influence of a groundwater circulation well in a BTEX-contaminated aquifer. Ground Water Monit Remediat 22(3):144–150

Montgomery MT, Osburn CL, Furukawa Y, Gieskes JM (2008) Increased capacity for PAH mineralization in biologically mixed marine sediments. Bioremed J 12(2):1–13

Morita N, Shibahara A, Yamamoto K, Shinkai K, Kajimoto G, Okuyama H (1993) Evidence for cis–trans isomerization of a double bond in the fatty acids of the psychrophilic bacterium Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1. J Bacteriol 175:916–918

Morrison D, Alexander M (1997) Microbial competition for nutrients and the relative biodegradability of minor toxic constituents. Environ Toxicol Chem 16:1561–1567

Mosqueda G, Ramos-González MI, Ramos JL (1999) Toluene metabolism by the solvent-tolerant Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E strain, and its role in solvent impermeabilization. Gene 232:69–76

Muller JF, Stevens AM, Craig J, Love NG (2007) Transcriptome analysis reveals that multidrug efflux genes are upregulated to protect Pseudomonas aeruginosa from pentachlorophenol stress. Appl Environ Microbiol 73(14):4550–4558

Nyman JA (1999) Effect of crude oil and chemical additives on metabolic activity of mixed microbial populations in fresh marsh soils. Microb Ecol 37:152–162

Pohlman JW, Coffin RB, Mitchell CS, Montgomery MT, Spargo BJ, Steele JK, Boyd TJ (2002) Transport, deposition, and biodegradation of particle bound polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in a tidal basin of an industrial watershed. Environ Monitor Assess 75:155–167

Powell SN, Singleton DR, Aitken MD (2008) Effects of enrichment with salicylate on bacterial selection and PAH mineralization in a microbial community from a bioreactor treating contaminated soil. Environ Sci Technol 42(11):4099–4105

Sanger DM, Holland AF, Scott GI (1999) Tidal creek and salt marsh sediments in South Carolina coastal estuaries: II. Distribution of organic contaminants. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 37:458–471

Segura A, Hurtado A, Rivera B, Lazaroaie MM (2008) Isolation of new toluene-tolerant marine strains of bacteria and characterization of their solvent-tolerance properties. J Appl Microbiol 104:1408–1416

Simon M, Azam F (1989) Protein content and protein synthesis rates of planktonic marine bacteria. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 51:201–213

Smith DC, Azam F (1992) A simple, economical method for measuring bacterial protein synthesis rates in seawater using 3H-leucine. Mar Microb Food Webs 6(2):107–114

Stamper DM, Montgomery MT (2008) Petroleum and synthetic oils biodegradation in a combined approach for treating oily and non-oily wastewaters. Can J Microbiol 54(8):687–693

Tso SK, Taghon GL (2006) Protozoan grazing increases mineralization of naphthalene in marine sediment. Microb Ecol 51(4):460–469

Tuominen L (1995) Comparison of leucine uptake methods and a thymidine incorporation method for measuring bacterial activity in sediment. J Microbiol Meth 24:125–134

Van Dolah RF, Wendt PH, Wenner EL (1990) A physical and ecological characterization of the Charleston Harbor Estuarine System. Final Report to the South Carolina Coastal Council, 634 pp

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the crews of the R/V Cape Hatteras for assistance in sampling the Charleston Harbor. Julia (Steele) Tsakumis and Dawn Castle provided technical assistance and sample processing. Site support was provided by Matthew A. Hunt, P. E. at Naval Facilities Engineering Command, South Division. This manuscript was formatted for publication by Angela DeLozier and improved by technical comments from Jason Speicher and Robert LaMontagne and two annonymous reviewers. Research funding was provided by Linda Chrisey at the Office of Naval Research (to MTM and DCS) Contract # N0001403WX20068 and the NRL Shiptime Program (to TJB). This work was not funded by any commercial industry (such as the paper mill) in the sampled region.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Montgomery, M.T., Boyd, T.J., Osburn, C.L. et al. PAH mineralization and bacterial organotolerance in surface sediments of the Charleston Harbor estuary. Biodegradation 21, 257–266 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10532-009-9298-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10532-009-9298-3