Abstract

Background and aims

Faecal incontinence (FI) is a socially devastating problem. The treatment algorithm depends on the aetiology of the problem. Large anal sphincter defects can be treated by sphincter replacement procedures: the dynamic graciloplasty and the artificial bowel sphincter (ABS).

Materials and methods

Patients were included between 1997 and 2006. A full preoperative workup was mandatory for all patients. During the follow-up, the Williams incontinence score was used to classify the symptoms, and anal manometry was performed.

Results

Thirty-four patients (25 women) were included, of which, 33 patients received an ABS. The mean follow-up was 17.4 (0.8–106.3) months. The Williams score improved significantly after placement of the ABS (p < 0.0001). The postoperative anal resting pressure with an empty cuff was not altered (p = 0.89). The postoperative ABS pressure was significantly higher then the baseline squeeze pressure (p = 0.003). Seven patients had an infection necessitating explantation. One patient was successfully reimplanted.

Conclusion

The artificial bowel sphincter is an effective treatment for FI in patients with a large anal sphincter defect. Infectious complications are the largest threat necessitating explantation of the device.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Faecal incontinence (FI) is a complex problem. The resulting social isolation is a major concern, which results in a reduced quality of life [1]. The real prevalence is unknown, but studies show a higher prevalence than expected [2–5]. Most patients are females with one or more vaginal deliveries in the past. Direct trauma to the anal sphincter complex can give immediate problems or problems later in life [6, 7].

The initial therapy should be conservative, e.g. diet modifications, medication, biofeedback physiotherapy or retrograde irrigation. Surgical intervention is indicated when conservative treatment fails. An anal repair is usually the first choice of treatment for a minor sphincter defect. Satisfactory results are achieved in a tension-free repair in 47–100% of the cases [8]. Long-term results are less satisfying [9]. Sacral nerve modulation (SNM) has proven to be effective for treating faecal incontinence in patients with an intact sphincter complex [10]. Sphincter replacing therapy is indicated in patients with large sphincter defects or completely disrupted sphincters and in case of SNM failure. The sphincter replacement procedures are grossly divided in the dynamic graciloplasty (DGP) [11, 12] or the artificial bowel sphincter (ABS). The first artificial bowel sphincter for faecal incontinence was a urinary prosthesis (AMS 800, AMS) placed by Christiansen in 1987 [13]. Modifications had to be made to suit the anal sphincter for use in patients with faecal incontinence.

Until 1997, patients with faecal incontinence due to large anal sphincter defects were treated with DGP in our institution [16]. Since then, the ABS was introduced in our institution for the same indication. Because the operating technique is similar, there was no learning curve to be dealt with. Is this study, the results of the ABS implantations for the treatment of feacal incontinence in a large volume centre are presented.

Materials and methods

This study is a non-randomised, non-controlled, prospective single-centre study. Thirty-four patients with persisting or recurrent end-stage FI were included between 1997 and 2006.The majority of patients had large (>33% of circumference) anal sphincter defects. A sufficient length of the perineum was a prerequisite for ABS implantation. Previous sphincter replacement surgery was no exclusion criterion for implantation of an ABS. All patients underwent a full preoperative examination consisting of a defaecography, endo-anal ultrasound (SDD 2000, Multiview, Aloka, Japan, 7,5 Mhz endo-anal transducer), pudendal nerve terminal motor latency measurement (St Mark’s pudendal electrode) and anal manometry using a Konigsberg catheter (Konigsberg Instrument, Pasadena CA, USA) connected to a polygraph (Synectics Medical, Stockholm, Sweden). An Acticon artificial bowel sphincter (ABS, American Medical Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was used in all patients. The Williams incontinence score was used to classify the symptoms. Anal manometry was routinely performed during the follow-up and used to objectivity ABS function. The follow-up appointments were scheduled at 1, 3, 6, 12 months and annually. Infection necessitating explantation was a primary endpoint. A re-intervention was a secondary endpoint.

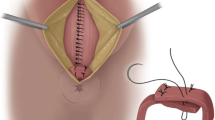

The system implantation has been described extensively elsewhere [14, 15], but will be summarised here. The ABS implant consists of three parts: an inflatable balloon, a cuff and a pump. Under strict systemic and local antibiotic prophylaxes, the cuff is placed around the anus using two lateral incisions. The pump is placed in the labia majora or scrotum, and the pressure-regulating balloon is placed in cavum Retzii. Care is taken not to perforate the rectum. If a perforation occurs, the procedure is stopped. After proper wound healing, the patient is eligible for another implantation procedure.

Data are expressed as the mean with the range between parenthesis. Data were analysed using the commercially available GraphPad Prism 4.00 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA). The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used for non-parametric paired values. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

The patient population existed of 25 women and nine men. The aetiology of the faecal incontinence is shown in Table 1. Three patients were previously treated with a DGP. The average age was 55.3 (23.8–75.6) years. The mean period of faecal incontinence before the placement of the ABS was 11.0 (1.0–48.0) years. One patient had a rectum perforation during the initial surgery, and placement of the ABS was abandoned. She awaits a second implant attempt. Thirty-three patients were implanted. The mean follow-up was 17.4 (0.8–106.3) months. The mean procedure time was 68.1 min (38.0–105.0). In 24 patients, the length of the cuff was 11 cm, in three patients 10 cm, in two patients 13 cm, in two patients 12 cm, in one patient 14 and in one patient 9. The width of the cuff was in all, but one patient, 2.9 cm. There was one patient with a cuff off 2.0 cm. All patients received a pressure-regulating balloon of 91–100 cm H2O. The mean postoperative hospital stay was 3.5 (2.0–12.0) days.

The mean preoperative Williams score of 4.8 (4–5) decreased significantly after ABS placement to 2.1 (1–5; Fig. 1). The mean preoperative anal resting pressure was 58.1 (17.0–128.0) mmHg. This was not significantly altered after implantation (60.3 (21.0–93.0 mmHg; p = 0.89). The mean preoperative squeeze pressure was 80.1 (25.0–149.0) mmHg, which increased to 120.5 (65.0–154.0) mmHg after implantation (p = 0.003; Fig. 2).

Thirteen patients (39%) complained about a rectal evacuation problem. In 12 patients, this could be managed conservatively. One patient had a revision of the system with placement of a wider anal cuff. Seven patients (21.2%) had an infection of the system, which led to seven explantations. One of these patients has been implanted successfully with a new ABS (Fig. 3).

In one patient, the ABS was successfully converted to a dynamic graciloplasty. In two patients, a colostomy was performed. The other three patients had no other interventions.

One patient was explanted due to persisting peri-anal pain without an infection. She received a colostomy. Twenty-six reinterventions (including explantations) had to be performed. This means 0.79 re-intervention per implanted patient.

Discussion

There is a large experience in our institution with the DGP [16]. However, since 1997, the ABS is also performed in our institution for the same area of indications as the DGP. When a patient qualifies for a sphincter replacement procedure, he or she can decide whether an ABS or DGP will be performed. Nonetheless, sufficient perineal length is a prerequisite for ABS implantation in a female patient. We believe that the risk for late erosion of the ABS is higher in the case of severe, cloaca-like malformations of the perineum. In these cases, a DGP is the preferred procedure. All patients in this study had an adequate perineal length.

In the beginning, the initial infection rate of the DGP was a problem, but improved as a result of technical modifications and the introduction of systemic and local antibiotic prophylaxis. The same prophylaxis protocol was used for the implantation of ABS. However, despite meticulous application of the antimicrobial protocol, the infection rate of the ABS implantations in our patient population remains high and is comparable with other series [14, 15]. We believe that this infection rate is likely to remain a serious problem in every attempt to place a corpus alienum around the anus through peri-anal incisions.

To overcome this problem of infection, Finlay et al. [17] have developed a new prosthetic sphincter, which is placed above the pelvic floor musculature by means of a laparotomy. It was hypothesised that this sphincter will function as a new puborectal sling in this position. Till now, 12 patients are implanted. Infectious complications, however, occurred in three patients (25%), with subsequent removal of the system. Technical problems occurred in five of the nine remaining patients during follow-up. Technical failure is also one of the main problems of the ABS. Twelve of our patients had some sort of technical failure. This is also known from other studies concerning the ABS [18].

Only limited data on long-term follow-up of a sufficient number of ABS sphincters are available. There is one multicentre study with disappointing long-term data where the initial data were promising [19]. The anal manometry data of this patient population suggest poor action of the ABS. The authors conclude that the ABS acts as a passive barrier causing a rectal outlet obstruction. Our manometry data contradict with this conclusion. We strongly believe that the ABS acts as an active sphincter. In our experience, the patients need to deflate the anal cuff to defecate. Nevertheless, constipation can be a problem. Thirteen of our patients complained about constipation. This could be solved in the majority of patients by conservative means. One patient needed a wider anal cuff to treat an outlet obstruction.

The indications for sphincter replacement surgery are decreasing in our institution since the introduction of SNM. The relative numbers of DGPs and ABSs decreased, while the number of SNM has increased. This implicates that ABS and DGP are reserved for the more severe complicated cases of faecal incontinence. A higher complication rate is therefore expected. However, the placement of an ABS remains an alternative to a colostomy in the well-informed and motivated patient even if a DGP has failed.

Conclusion

The artificial bowel sphincter is an effective treatment option for severe faecal incontinence. Even in experienced hands, the risk of infection, explantation and system malfunctioning remain high. In well-informed and motivated patients, it is worthwhile to proceed to implantation, as the alternative is a colostomy. Our data suggest that the ABS acts as an active sphincter and not as a passive barrier.

References

Bharucha AE, Zinsmeister AR, Locke GR, Schleck C, McKeon K, Melton LJ (2006) Symptoms and quality of life in community women with fecal incontinence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 4:1004–1009

Gibel GD, Lefering R, Troidl H, Bloch H (1998) Prevalence of fecal incontinence: what can be expected? Int J Colorectal Dis 13:73–77

Johanson JF, Lafferty J (1996) Epidemiology of fecal incontinence: the silent affliction. Am J Gastroenterol 91:33–36

Nelson R, Norton N, Cautley E, Furner S (1995) Community-based prevalence of anal incontinence. JAMA 274:559–561

Nelson RL (2004) Epidemiology of fecal incontinence. Gastroenterology 126:S3–S7 (Jan)

Oberwalder M, Dinnewitzer A, Khurrum B, Thlaer K, Cotman K, Nogueras J et al (2004) The association between late-onset fecal incontinence and obstetric anal sphincter defects. Arch Surg 139:429–432

Kamm MA (1994) Obstetric damage and fecal incontinence. Lancet 334:730–733

Baig MK, Wexner SD (2000) Factors predictive of outcome after surgery for faecal incontinence. Br J Surg 87:1316–1330

Baxter NN, Bravo Guittierez A, Lowry AC, Parker SC, Madoff RD (2003) Long-term results of sphincteroplasty for acquired faecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 46:A21–A22

Matzel KE, Kamm MA, Stösser M, Baeten CGMI, Christiansen J, Madoff R, Mellgren A et al (2004) Sacral nerve stimulation for feacal incontinence: multicenter study. Lancet 363:1270–1276

Williams NS, Patel J, George BD, Halan RI, Watkins ES (1991) Development of an electrically stimulated neoanal sphincter. Lancet 338:1166–1169

Baeten C, Spaans F, Fluks A (1988) An implanted neuromuscular stimulator for fecal continence following previously implanted gracilis muscle. Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum 31:134–137

Christiansen J, Lorentzen M (1987) Implantation of artificial sphincter for anal incontinence. Lancet 2:244–245

Wong WD, Congliosi SM, Spencer MP, Corman ML, Tan P, Opelka FG et al (2002) The safety and efficacy of the artificial bowel sphincter for fecal incontinence: results from a multicenter cohort study. Dis Colon Rectum 45:1139–1153

Altomare DF, Dodi G, La Torre F, Romano G, Melega E, Rinaldi M (2001) Multicentre retrospective analysis of the outcome of artificial anal sphincter implantation for severe faecal incontinence. Br J Surg 88:1481–1486

Rongen M-JGM, Uludag Ö, El Naggar K, Geerdes BP, Konsten J, Baeten CGMI (2003) Long-term follow-up of dynamic graciloplasty for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 46:716–721

Finlay IG, Richardson W, Hajivassiliou CA (2004) Outcome after implantation of a novel prosthetic anal sphincter. Br J Surg 91:1485–1492

Belyaev O, Muller C, Uhl W (2006) Neosphincter surgery for fecal incontinence: a critical and unbiased review of the relevant literature. Surg Today 36:295–303

Altomare DF, Binda GA, Dodi G, La Torre F, Romano G, Rinaldi M, Melega E (2004) Disappointing long-term results of the artificial bowel sphincter for faecal incontinence. Br J Surg 91:1352–1353

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Melenhorst, J., Koch, S.M., van Gemert, W.G. et al. The artificial bowel sphincter for faecal incontinence: a single centre study. Int J Colorectal Dis 23, 107–111 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-007-0357-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-007-0357-0