Abstract

Background

Nutritional supplementation of omega-3 fatty acids has been proposed to modulate the balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators in sepsis. If proved to improve clinical outcomes in critically ill patients with sepsis, this intervention would be easy to implement. However, the cumulative evidence from several randomized clinical trials (RCTs) remains unclear.

Methods

We searched the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, and EMBASE through December 2016 for RCTs on parenteral or enteral omega-3 supplementation in adult critically ill patients diagnosed with sepsis or septic shock. We analysed the included studies for mortality, intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay, and duration of mechanical ventilation, and used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach to assess the quality of the evidence for each outcome.

Results

A total of 17 RCTs enrolling 1239 patients met our inclusion criteria. Omega-3 supplementation compared to no supplementation or placebo had no significant effect on mortality [relative risk (RR) 0.85; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.71, 1.03; P = 0.10; I 2 = 0%; moderate quality], but significantly reduced ICU length of stay [mean difference (MD) −3.79 days; 95% CI −5.49, −2.09; P < 0.0001, I 2 = 82%; very low quality] and duration of mechanical ventilation (MD −2.27 days; 95% CI −4.27, −0.27; P = 0.03, I 2 = 60%; very low quality). However, sensitivity analyses challenged the robustness of these results.

Conclusion

Omega-3 nutritional supplementation may reduce ICU length of stay and duration of mechanical ventilation without significantly affecting mortality, but the very low quality of overall evidence is insufficient to justify the routine use of omega-3 fatty acids in the management of sepsis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sepsis is a syndrome of life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection. Mortality from sepsis is approximately 10% when the Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score ≥2, and exceeds 40% in patients with septic shock [1]. Despite the advancement of best practice management by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign [2], the public health and disease burden of sepsis remains high [3,4,5]. As such, critical care research continues to search for ways to optimize clinical outcomes in this population, including through nutritional supplements [6].

Distinct changes in lipid metabolism have been noted in the critically ill, and the associations between nutritional intervention, lipid profile, and survival are of considerable interest [7]. Nutritional supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids has been proposed to modulate the immune response in critical illness by inhibiting pro-inflammatory (eicosanoid, NF-kB) and promoting anti-inflammatory (resolvin, protectin) mediators [8,9,10,11]. Clinical evidence for potential benefits of omega-3 fatty acids in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [12, 13] and general critical illness [14, 15] has been tempered by studies showing equivocal effects [16,17,18,19] and even potential harm [20].

Several RCTs have also investigated omega-3 supplementation in sepsis over the past two decades; most recently, Hall et al. [21] suggested that a reduced ratio of arachidonic acid (AA) to eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid [AA/(EPA + DHA)] after treatment with omega-3 fatty acids may be associated with improved survival in critically ill patients with sepsis. However, a comprehensive synthesis of these data has not been conducted, and the evidence for benefit remains unclear [2]. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs to evaluate the effect of omega-3 nutritional supplementation on clinical outcomes of adult critically ill patients with sepsis or septic shock.

Methods

We did not publish or register a protocol for this systematic review.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible studies met the following criteria: (1) randomized clinical trial (RCT) study design; (2) the population involved adult patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) with sepsis or septic shock; (3) the intervention group received either enteral or parenteral supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids; (4) the outcomes included any of the following: mortality (using the longest available follow-up time), ICU length of stay (LOS), and duration of mechanical ventilation (DMV).

Search strategy

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library from inception until December 2016. Our search strategies are given in Additional file 1: Tables S1–S3 and are limited to RCTs but not by language or publication date. We also screened the references from all included studies and relevant systematic reviews. Independently and in duplicate, two reviewers (CL and SS) screened titles and abstracts for eligibility, and conducted full-text reviews of selected studies. Disagreements over study selection were resolved by discussion and consensus. Studies fulfilling all of the eligibility criteria were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (CL and SS) independently extracted data of interest from included studies, with disagreements resolved by discussion and consensus. Mortality was the primary outcome, and ICU LOS and DMV were secondary outcomes. When data were missing or unclear, we contacted study authors for clarification.

Risk of bias assessment

Using the Cochrane Collaboration tool [22], two reviewers (CL and SS) independently assessed each study for risk of bias in seven domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of patients and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources of bias. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus, and adjudication by a third reviewer (WA) when necessary. For each study, the overall risk of bias was judged to be high if the risk of bias was high in any domain, unclear if the risk of bias was unclear in any domain (and not high in other domains), and low if the risk of bias was low across all domains.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using RevMan software (Review Manager, version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014). We used inverse variance weighting and the DerSimonian and Laird [23] random-effects model to pool the weighted effect of estimates across studies. We reported relative risks (RRs) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for dichotomous outcomes and mean differences (MDs) with 95% CI for continuous outcomes. In studies where standard deviation (SD) for ICU LOS and DMV was not reported, we calculated SD from other measures of variability (standard error (SE), interquartile range (IQR), or 95% CI) following the methods suggested by the Cochrane Collaboration [24]. We combined low- and high-dose omega-3 intervention groups from one trial [25] into a single intervention group, using formulae described in the Cochrane Handbook [24] to calculate combined means and SDs for relevant outcomes. We assessed between-studies heterogeneity using Chi-square and I 2 statistics, with significant heterogeneity defined as I 2 > 50% or P < 0.10 [26].

We assessed publication bias for the mortality outcome by visual inspection of funnel plots. We investigated heterogeneity between studies by performing a post hoc subgroup analysis comparing parenteral with enteral administration of omega-3. We did not perform a subgroup analysis comparing risk of bias levels, as all studies had either a “high” or “unclear” overall risk of bias.

To explore the robustness of the results, we conducted the following post hoc sensitivity analyses: For all outcomes, we excluded trials that used per-protocol analysis, trials published in abstract form, trials that did not explicitly blind patients and healthcare personnel, trials that administered control formulae containing omega-3, and trials that did not administer the control group a placebo feed. For the mortality outcome, we excluded trials in which eligibility for inclusion was unclear (based on ICU admission), and further explored odds ratio (OR) as an alternative to RR analysis. For the ICU LOS outcome, we excluded trials that did not directly report SDs. Lastly for the DMV outcome, we excluded trials that did not directly report SDs and trials that did not stratify randomization by mechanical ventilation.

Quality of evidence

For each outcome of interest, we used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach [27] to rate the quality of evidence based on risk of bias, indirectness, inconsistency, imprecision, and other factors. Indirectness was evaluated by reviewing each trial’s study population, intervention, control, and outcomes. Inconsistency was evaluated using between-trial Chi-square and I 2 heterogeneity analyses. Imprecision was evaluated based on event rate, optimal sample size, and width of confidence intervals. The quality of evidence for each outcome was downgraded one level for “serious” limitations and two levels for “very serious” limitations.

Results

Search results

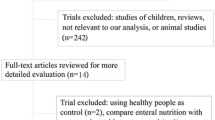

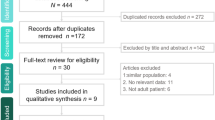

Our search strategy identified a total of 175 citations, and 90 citations remained after removing duplicates. Screening of titles and abstracts led to the exclusion of 57 articles and the retrieval of 33 articles for full-text assessment, of which 16 were excluded for reasons outlined in Fig. 1. A total of 17 RCTs [25, 28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43] met our inclusion criteria, representing 1239 critically ill patients with sepsis.

Study characteristics

Seventeen studies enrolled patients diagnosed with sepsis or subsets of sepsis (early sepsis [36], abdominal sepsis [32], severe sepsis [34, 35, 38], and septic shock [35, 38, 41]). Three studies [31, 35, 37] required both sepsis and mechanical ventilation for inclusion. One study [32] enrolled ICU and post-anaesthesia care unit (PACU) patients with abdominal sepsis; we abstracted data for the ICU subset only.

Ten studies [29, 32,33,34, 38,39,40,41,42,43] used the parenteral route to administer omega-3 supplements, while seven studies [25, 28, 30, 31, 35,36,37] used the enteral route. Brand-name formulae used included Omegaven [29, 32,33,34, 38, 41], Oxepa [31, 36, 37], Impact [28, 30], and Lipoplus [43]. Available data on the contents of all brand-name intervention and control formulae are given in Additional file 1: Tables S4–S5. Six studies calculated daily dose by weight [29, 31,32,33, 39, 40], five studies calculated daily dose by basal energy expenditure (BEE) and the Harris Benedict equation [28, 30, 35,36,37], and five studies administered a fixed daily dose [25, 34, 38, 41, 42]; in one study [43], the dosing method was not specified. The duration of supplementation ranged between 4 and 14 days.

While most studies administered the control group a placebo solution using standard enteral or parenteral formulae without omega-3, four studies [25, 29, 33, 41] assigned controls to standard sepsis care only; two of these explicitly defined standard care according to 2008 Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines [29, 33].

For outcomes, all studies assessed mortality, twelve assessed ICU LOS, and seven assessed DMV. Eleven studies evaluated 28-day mortality [25, 31, 33,34,35,36, 39,40,41,42,43], and the remainder defined mortality as 60-day [37], in-hospital [33], ICU [32], or left parameters undefined [28, 30, 38].

Six studies [28, 32, 34,35,36, 38] were appropriately blinded (patients, healthcare personnel, and research personnel), and seven studies [25, 29, 32, 33, 37, 39, 41] conducted a full intention-to-treat analysis of data. Six studies [28,29,30,31, 35, 36] were industry-funded. Finally, one study [32] was published solely as an abstract, but the authors provided missing data via personal communication. Table 1 presents further details of eligible studies.

Risk of bias

Using the Cochrane Collaboration tool for risk of bias [22], twelve studies were judged to be at high risk of bias, many of these due to attrition and performance bias. Risk of bias was unclear for the remaining five studies (Fig. 2).

Risk of bias assessment of the included trials using the Cochrane Collaboration tool. Individual risk of bias assessments across seven domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other bias. Risk of bias levels: low (green), unclear (yellow), high (red)

Quality of evidence

Table 2 presents our GRADE [27] assessment of the quality of evidence by outcome. Evidence quality was assessed as moderate for mortality and very low for both ICU LOS and DMV outcomes.

Main outcomes

Mortality was reported by 17 trials enrolling 1239 patients (Fig. 3). Omega-3 was not associated with a significant reduction in mortality (RR 0.85; 95% CI 0.71, 1.03; P = 0.10; I 2 = 0%; moderate quality). ICU length of stay was reported in 12 trials enrolling 925 patients (Fig. 4). There was a significant reduction in ICU LOS (MD −3.79 days; 95% CI −5.49, −2.09; P < 0.0001, I 2 = 82%; very low quality) for patients supplemented with omega-3. Duration of mechanical ventilation was reported in seven trials enrolling 495 patients (Fig. 5). There was a significant reduction in DMV (MD −2.27 days; 95% CI −4.27, −0.27; P = 0.03, I 2 = 60%; very low quality) in the group of patients supplemented with omega-3.

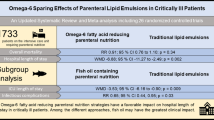

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

Ten studies used parenteral administration and seven studies used enteral administration of omega-3. We performed a post hoc subgroup analysis comparing these subgroups for the outcome of mortality (Additional file 1: Figure S1) and found no significant differences in treatment effect (P = 0.97, I 2 = 0%) between trials that used parenteral (RR 0.89; 95% CI 0.66, 1.19; P = 0.42; I 2 = 0%) compared to enteral (RR 0.88; 95% CI 0.64, 1.21; P = 0.43; I 2 = 35%) routes. However, the analysis is confounded by another major difference between subgroups: Most enteral formulations administered omega-3 in combination with other supplements (including arginine, selenium, and mRNA), while all parenteral formulations administered omega-3 as the sole supplement. Since the distinct influences of these two characteristics (additional supplementation and route of administration) on the treatment effect cannot be distinguished, no definitive conclusions can be drawn from this analysis.

Sensitivity analyses excluding trials that used per-protocol analysis [28, 30, 31, 34,35,36, 38, 40, 42, 43] and trials that used control formulae containing omega-3 [31, 36] produced congruent results for all three outcomes. For the mortality outcome, exclusion of trials in which ICU admission was unclear [39], trials published in abstract form [32], trials without explicit blinding of patients and healthcare personnel [25, 29,30,31, 33, 37, 39,40,41,42,43], and trials that did not administer the control group a placebo feed [25, 29, 33, 41] yielded similar non-significant results.

However, for the ICU LOS outcome, exclusion of trials that did not explicitly blind patients and healthcare personnel to the intervention [25, 30, 31, 33, 37, 40,41,42,43] rendered the significant reduction in ICU LOS non-significant (MD −3.63; 95% CI −7.85, 0.60; P = 0.09, I 2 = 85%). Similarly, the significant reduction in DMV was countered by the exclusion of trials that did not explicitly blind patients and healthcare personnel [25, 30, 31, 37, 43] (MD −4.63; 95% CI −10.00, 0.75; P = 0.09, I 2 = 70%), trials that did not stratify mechanically ventilated patients during randomization [25, 30, 36] (MD −1.78 days; 95% CI −4.39, 0.83; P = 0.18, I 2 = 61%), trials that did not administer the control group a placebo feed [25] (MD −2.10 days; 95% CI −4.48, 0.29; P = 0.08, I 2 = 65%), and trials published in abstract form [32] (MD −2.32 days; 95% CI −4.86, 0.22; P = 0.07, I 2 = 67%). Details of these analyses are given in Additional file 1: Tables S6–S8.

Publication bias

Visual inspection of funnel plots for the mortality and ICU LOS outcomes (Additional file 1: Figures S2–S3) did not reveal small-study effects suggestive of publication bias.

Discussion

Our meta-analysis of 17 RCTs (1239 patients) suggests, based on moderate-quality evidence, that omega-3 supplementation does not significantly reduce mortality in septic critically ill patients, with the absolute effect ranging from 77 fewer to 8 more deaths per 1000 patients. Very low-quality evidence also suggests that omega-3 may reduce length of ICU stay and duration of mechanical ventilation, but these results are challenged by multiple sensitivity analyses.

A recent meta-analysis of eleven RCTs (808 patients) [44] also explored omega-3 in the critically ill with sepsis and similarly found a non-significant reduction in mortality (RR 0.84; 95% CI 0.67 to 1.05; P = 0.12) and a significant reduction in DMV (MD −3.82 days; 95% CI −4.61 to −3.04; P < 0.001). However, the authors did not find a significant reduction in ICU LOS (MD −2.70 days; 95% CI −6.40 to 1.00; P = 0.15). Key differences in their analysis include the search of a single database (PubMed), the use of the Jadad score to assess risk of bias [45], the absence of six studies included in our analysis [25, 28, 39,40,41,42], and the inclusion of one study excluded from our analysis for enrolling patients without sepsis [46].

Another meta-analysis of twelve RCTs (721 patients) evaluated the effects of parenteral omega-3 in sepsis [47]. Their analysis revealed a significant reduction in 28-day mortality (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.99, P = 0.04) and ICU LOS (MD −3.10 days; 95% CI −5.98 to −0.21; P = 0.04) and a non-significant effect on DMV (MD 1.33 days; 95% CI −5.09 to 7.75; P = 0.69). Here the inconsistencies with our meta-analysis may be explained by the exclusion of trials using enteral omega-3, the inclusion of one study excluded from our analysis for enrolling patients without sepsis [46], and the absence of more recently published RCTs [29, 33, 38].

Beyond the potential reductions in DMV and ICU LOS suggested by the present meta-analysis, the risks and costs of omega-3 supplementation must also be addressed. Although the cost of omega-3 supplementation varies by dose, frequency, route of administration, and choice of formula, the leading parenteral formula used in this meta-analysis (Omegaven) has been reported to cost up to 3 times more than another lipid emulsion in conventional use [48]. According to its manufacturer, Omegaven in North America is currently obtained only by applying to special access programs.

Safety is another key consideration. While most RCTs studying omega-3 supplementation in critical illness have reported minimal adverse effects, others have identified important risks that include significantly longer hospital and ICU lengths of stay [30, 34], increased duration of mechanical ventilation [47], fewer ventilator-free and ICU-free days [20], elevated triglyceride levels [29, 37], and a higher incidence of diarrhoea [20, 25]. Most concerning are reported trends towards increased mortality [20, 28, 31, 39, 49]. Even in meta-analyses that demonstrate a non-significant reduction in mortality [18, 44, 50, 51], as this one does, the upper limit of the CI cannot exclude the potential for increased mortality with omega-3 supplementation. Detailed data on non-surviving patients would be necessary to explore characteristics associated with increased mortality risk with omega-3 supplementation.

Limitations that call for cautious interpretation of these findings exist at both the study and review level. Dosing and route of administration varied across trials; whether these characteristics modify the treatment effect has not been sufficiently studied for omega-3, and our subgroup analysis comparing enteral and parenteral routes was inconclusive. Recognizing that several trials administered omega-3 in combination with other supplements, we downgraded the quality of evidence across outcomes for indirectness of intervention. For ICU LOS and DMV, we further downgraded the quality of evidence for significant heterogeneity and high overall risk of bias.

Strengths of this meta-analysis include its comprehensive database search, literature assessments conducted independently and in duplicate, the expertise of a registered dietician, the use of the Cochrane Collaboration Tool [22] to assess risk of bias, and careful adherence to the GRADE approach [27] and PRISMA guidelines [52]. It addresses a specific question and includes recent eligible trials. To date, this is the largest meta-analysis conducted on the effect of omega-3 supplementation in critically ill patients with sepsis.

Conclusions

Our meta-analysis should prompt caution against the routine use of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation for critically ill patients with sepsis. While very low-quality evidence suggests that omega-3 may reduce the number of days patients spend on mechanical ventilation and in the ICU, these effects are overturned by multiple sensitivity analyses. Moderate-quality evidence also demonstrates a non-significant trend towards reduced mortality, yet the upper limit of confidence reveals potential for harm. Here, even the slightest possibility of increased mortality (moderate-quality evidence) demonstrated in the present and previous meta-analyses still outweighs the potential benefits of reduced ICU LOS and DMV (very low-quality evidence).

With current evidence limited in quality and quantity, the profile of risk and benefit does not favour treatment of sepsis with omega-3. Justification for omega-3 in sepsis will require large-scale, high-quality RCTs that strengthen the evidence for clinical benefit enough to outweigh the risks and costs of this intervention [53]. Until then, the routine use of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in patients with sepsis should be avoided.

Abbreviations

- AA:

-

arachidonic acid

- APACHE II:

-

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II

- ARDS:

-

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- BEE:

-

basal energy expenditure

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- DHA:

-

docosahexaenoic acid

- DMV:

-

duration of mechanical ventilation

- EN:

-

enteral nutrition

- EPA:

-

eicosapentaeonic acid

- FE:

-

fixed effects

- GLA:

-

gamma linolenic acid

- GRADE:

-

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- ITT:

-

intention to treat

- LCT:

-

long-chain triglycerides

- LOS:

-

length of stay

- MD:

-

mean difference

- MV:

-

mechanical ventilation

- NG:

-

nasogastric

- NR:

-

non-reported

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- PACU:

-

post-anaesthesia care unit

- PN:

-

parenteral nutrition

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PUFA:

-

polyunsaturated fatty acid

- RCT:

-

randomized clinical trial

- RE:

-

random effects

- RR:

-

relative risk

- SOFA:

-

Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment

- TPN:

-

total parenteral nutrition

References

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour C, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–10.

Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(2):580–637.

Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304(16):1787–94.

Vincent JL, Marshall JC, Namendys-Silva SA, Francois B, Martin-Loeches I, Lipman J, et al. Assessment of the worldwide burden of critical illness: the intensive care over nations (ICON) audit. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(5):380–6.

Fleischmann C, Scherag A, Adhikari NK, Hartog CS, Tsaganos T, Schlattmann P, et al. Assessment of global incidence and mortality of hospital-treated sepsis. Current estimates and limitations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(3):259–72.

Preiser JC, van Zanten AR, Berger MM, Biolo G, Casaer MP, Doig GS, et al. Metabolic and nutritional support of critically ill patients: consensus and controversies. Crit Care (London, England). 2015;19:35.

Green P, Theilla M, Singer P. Lipid metabolism in critical illness. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2016;19(2):111–5.

Martin JM, Stapleton RD. Omega-3 fatty acids in critical illness. Nutr Rev. 2010;68(9):531–41.

Whelan J, Broughton KS, Kinsella JE. The comparative effects of dietary alpha-linolenic acid and fish oil on 4- and 5-series leukotriene formation in vivo. Lipids. 1991;26(2):119–26.

Zhao Y, Joshi-Barve S, Barve S, Chen LH. Eicosapentaenoic acid prevents LPS-induced TNF-α expression by preventing NF-κB activation. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004;23(1):71–8.

Ariel A, Serhan CN. Resolvins and protectins in the termination program of acute inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2007;28(4):176–83.

Pontes-Arruda A, Demichele S, Seth A, Singer P. The use of an inflammation-modulating diet in patients with acute lung injury or acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis of outcome data. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2008;32(6):596–605.

Gadek JE, DeMichele SJ, Karlstad MD, Pacht ER, Donahoe M, Albertson TE, et al. Effect of enteral feeding with eicosapentaenoic acid, gamma-linolenic acid, and antioxidants in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Enteral nutrition in ARDS Study Group. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(8):1409–20.

Heller AR, Rossler S, Litz RJ, Stehr SN, Heller SC, Koch R, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids improve the diagnosis-related clinical outcome. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(4):972–9.

Grau-Carmona T, Bonet-Saris A, Garcia-de-Lorenzo A, Sanchez-Alvarez C, Rodriguez-Pozo A, Acosta-Escribano J, et al. Influence of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids enriched lipid emulsions on nosocomial infections and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients: ICU lipids study. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(1):31–9.

Zhu D, Zhang Y, Li S, Gan L, Feng H, Nie W. Enteral omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in adult patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(4):504–12.

Santacruz CA, Orbegozo D, Vincent JL, Preiser JC. Modulation of dietary lipid composition during acute respiratory distress syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2015;39(7):837–46.

Palmer AJ, Ho CK, Ajibola O, Avenell A. The role of omega-3 fatty acid supplemented parenteral nutrition in critical illness in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(1):307–16.

Manzanares W, Dhaliwal R, Jurewitsch B, Stapleton RD, Jeejeebhoy KN, Heyland DK. Parenteral fish oil lipid emulsions in the critically ill: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38(1):20–8.

Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Thompson BT, deBoisblanc BP, Steingrub J, Rock P. Enteral omega-3 fatty acid, gamma-linolenic acid, and antioxidant supplementation in acute lung injury. JAMA. 2011;306(14):1574–81.

Hall TC, Bilku DK, Neal CP, Cooke J, Fisk HL, Calder PC, et al. The impact of an omega-3 fatty acid rich lipid emulsion on fatty acid profiles in critically ill septic patients. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2016;112:1–11.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical Research ed). 2011;343:d5928.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88.

Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. http://www.handbook.cochrane.org.

Hosny M, Nahas R, Ali S, Elshafei SA, Khaled H. Impact of oral omega-3 fatty acids supplementation in early sepsis on clinical outcome and immunomodulation. Egypt J Crit Care Med. 2013;1(3):119–26.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ (Clinical Research ed). 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ (Clinical Research ed). 2008;336(7650):924–6.

Bower RH, Cerra FB, Bershadsky B, Licari JJ, Hoyt DB, Jensen GL, et al. Early enteral administration of a formula (Impact) supplemented with arginine, nucleotides, and fish oil in intensive care unit patients: results of a multicenter, prospective, randomized, clinical trial. Crit Care Med. 1995;23(3):436–49.

Burkhart CS, Dell-Kuster S, Siegemund M, Pargger H, Marsch S, Strebel SP, et al. Effect of n-3 fatty acids on markers of brain injury and incidence of sepsis-associated delirium in septic patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2014;58(6):689–700.

Galban C, Montejo JC, Mesejo A, Marco P, Celaya S, Sanchez-Segura JM, et al. An immune-enhancing enteral diet reduces mortality rate and episodes of bacteremia in septic intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(3):643–8.

Grau-Carmona T, Moran-Garcia V, Garcia-de-Lorenzo A, Heras-de-la-Calle G, Quesada-Bellver B, Lopez-Martinez J, et al. Effect of an enteral diet enriched with eicosapentaenoic acid, gamma-linolenic acid and anti-oxidants on the outcome of mechanically ventilated, critically ill, septic patients. Clin Nutr (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2011;30(5):578–84.

Grecu I, Mirea L, Grintescu I. Parenteral fish oil supplementation in patients with abdominal sepsis. Clin Nutr. 2003;22:S23.

Hall TC, Bilku DK, Al-Leswas D, Neal CP, Horst C, Cooke J, et al. A randomized controlled trial investigating the effects of parenteral fish oil on survival outcomes in critically ill patients with sepsis: a pilot study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2015;39(3):301–12.

Khor BS, Liaw SJ, Shih HC, Wang LS. Randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial of fish-oil-based lipid emulsion infusion for treatment of critically ill patients with severe sepsis. Asian J Surg Asian Surg Assoc. 2011;34(1):1–10.

Pontes-Arruda A, Aragao AM, Albuquerque JD. Effects of enteral feeding with eicosapentaenoic acid, gamma-linolenic acid, and antioxidants in mechanically ventilated patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(9):2325–33.

Pontes-Arruda A, Martins LF, de Lima SM, Isola AM, Toledo D, Rezende E, et al. Enteral nutrition with eicosapentaenoic acid, γ-linolenic acid and antioxidants in the early treatment of sepsis: results from a multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blinded, controlled study: the INTERSEPT Study. Crit Care. 2011;15(3):R144.

Shirai K, Yoshida S, Matsumaru N, Toyoda I, Ogura S. Effect of enteral diet enriched with eicosapentaenoic acid, gamma-linolenic acid, and antioxidants in patients with sepsis-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Intensive Care. 2015;3(1):24.

Gultekin G, Sahin H, Inanc N, Uyanik F, Ok E. Impact of Omega-3 and Omega-9 fatty acids enriched total parenteral nutrition on blood chemistry and inflammatory markers in septic patients. Pak J Med Sci. 2014;30(2):299–304.

Qu A, Xu L. Yuyou zhifang ru dui nong du zheng huanzhe mianyi gongneng de tiaojie zuoyong guancha (Regulation of fish oil fat emulsion on immune function in patients with sepsis). Shandong Med J. 2009;49(6):13–5.

Wu YY. ω-3-duo bu baohe zhifangsuan dui nong du zheng huanzhe mianyi gongneng ji yuhou de yingxiang (Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on immune function and prognosis in patients with sepsis) (Master’s thesis). Hebei Medical University; 2010.

Zhao K, Zhou W, Bo C. ω-3 yuyou zhifang ru dui nong du zheng huanzhe de linchuang liaoxiao (Clinical efficacy of omega-3 fish oil fat emulsion in patients with sepsis). Shandong Med J. 2011;51(16):102.

Guo Y. ω-3 duo bu baohe zhifangsuan dui nong du zheng huanzhe linchuang liaoxiao ji yuhou de yingxiang (Effect of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on clinical efficacy and prognosis in patients with sepsis). Shanxi Med J. 2008;37(15):727–9.

Barbosa VM, Miles EA, Calhau C, Lafuente E, Calder PC. Effects of a fish oil containing lipid emulsion on plasma phospholipid fatty acids, inflammatory markers, and clinical outcomes in septic patients: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Crit Care. 2010;14(1):R5.

Tao W, Li P-S, Shen Z, Shu Y-S, Liu S. Effects of omega-3 fatty acid nutrition on mortality in septic patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Anesthesiol. 2015;16:39.

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12.

Friesecke S, Lotze C, Kohler J, Heinrich A, Felix SB, Abel P. Fish oil supplementation in the parenteral nutrition of critically ill medical patients: a randomised controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(8):1411–20.

Mo Y, Hu X, Chang L, Ma P. The effect of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in parenteral nutrition on the outcome of patients with sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chin Crit Care Med. 2014;26(3):142–7.

Jurewitsch B, Gardiner G, Naccarato M, Jeejeebhoy KN. Omega-3-enriched lipid emulsion for liver salvage in parenteral nutrition-induced cholestasis in the adult patient. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011;35(3):386–90.

Atkinson S, Sieffert E, Bihari D. A prospective, randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial of enteral immunonutrition in the critically ill. Guy’s Hospital Intensive Care Group. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(7):1164–72.

Manzanares W, Langlois PL, Dhaliwal R, Lemieux M, Heyland DK. Intravenous fish oil lipid emulsions in critically ill patients: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care (London, England). 2015;19:167.

Chen W, Jiang H, Zhou ZY, Tao YX, Cai B, Liu J, et al. Is omega-3 fatty acids enriched nutrition support safe for critical ill patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2014;6(6):2148–64.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1.

Rochwerg B, Alhazzani W, Jaeschke R. Clinical meaning of the GRADE rules. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(6):877–9.

Authors’ contributions

CL searched the literature, analysed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. SS searched the literature and analysed and interpreted the data. LL extracted and summarized nutritional data. WA conceived the idea, guided the analysis and interpretation of the data, and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Irina Grecu for supplying missing data. We thank Wenxi Chen and Xiang Lu for their assistance with accessing and translating studies published in Chinese.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Datasets supporting the conclusions of this article that are not included within the article (and its additional file) are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval

As this is a systematic review, the need for ethics approval was waived.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

13613_2017_282_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1: Table S1. Search Strategy—MEDLINE. Table S2. Search Strategy—EMBASE. Table S3. Search Strategy—Cochrane Library. Table S4. Contents of Brand-name Parenteral Formulations. Table S5. Contents of Brand-name Enteral Formulations. Figure S1. Subgroup Analysis for Mortality Outcome. Table S6. Sensitivity Analyses for Mortality Outcome. Table S7. Sensitivity Analyses for ICU Length of Stay Outcome. Table S8. Sensitivity Analyses for Duration of Mechanical Ventilation Outcome. Figure S2. Funnel Plot for Mortality Outcome. Figure S3. Funnel Plot for ICU Length of Stay Outcome. Table S9. PRISMA Checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, C., Sharma, S., McIntyre, L. et al. Omega-3 supplementation in patients with sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Ann. Intensive Care 7, 58 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-017-0282-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-017-0282-5