Abstract

Background

Systemic inflammation and cachexia are associated with adverse clinical outcomes in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). The Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI) is one of the main parameters used to assess these conditions, but its efficacy in DLBCL is inconclusive.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 228 DLBCL patients who were treated with R-CHOP immunochemotherapy (rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone). The patients were stratified according to GNRI score (> 98, 92 to 98, 82 to < 92, and < 82) as defined in previous studies. Additionally, the extent of sarcopenia was categorized as sarcopenia-both, sarcopenia-L3/PM alone, and non-sarcopenia-both according to skeletal muscle index.

Results

Survival curves plotted against a combination of GNRI and sarcopenia scores revealed two clear groups as follows: high cachexia risk (HCR) group (GNRI < 82, sarcopenia-both, or GNRI 82–92 with sarcopenia-L3/PM alone) and low cachexia risk (LCR) group (others). The HCR group had a lower complete response rate (46.5% vs. 86.6%) and higher frequency of treatment-related mortality (19.7% vs. 3.8%) and early treatment discontinuation (43.7% vs. 8.3%) compared with the LCR group. The median progression-free survival (PFS) (not reached vs. 10.3 months, p < 0.001) and overall survival (OS) (not reached vs. 12.9 months, p < 0.001) were much shorter in the HCR group than in the LCR group. On multivariable analyses, the HCR group was shown to be an independent negative prognostic factor for PFS and OS after adjusting the National Comprehensive Cancer Network-International Prognostic Index (NCCN-IPI).

Conclusions

A combined model of GNRI and sarcopenia may provide prognostic information independently of the NCCN-IPI in DLBCL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of adult non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Despite its aggressive nature, DLBCL is a potentially curable disease when treated with immunochemotherapy consisting of rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) [1,2,3]. The International Prognostic Index (IPI) and its variations are well-known prognostic markers for DLBCL [4,5,6]; however, these indices remain limited in their ability to predict disease prognosis in disease such as this, where survival remains < 50%. Inability to predict clinical outcomes may be due, in part, to the heterogeneous nature of the disease, consisting of several molecular subtypes including germinal center B-cell-like (GCB) and activated B-cell-like (ABC) types [7]. Recently, five robust DLBCL subsets were detected using whole-exome sequencing. These subsets were shown to be a better predictor of disease prognosis relative to IPI scores [8]. Furthermore, comprehensive geriatric assessment could identify non-fit patients in whom curative intent treatment did not improve the prognosis [9]. Development of such novel prognosticators for disease outcomes remains a significant unmet need, allowing doctors to individualize treatment strategies for DLBCL patients.

Cancer cachexia is a multifactorial syndrome characterized by ongoing loss of skeletal muscle mass, malnutrition, and progressive functional impairment [10]. Cancer cachexia is associated with increased treatment-related toxicity and poor prognosis in cancer patients [11,12,13]. Given the high tumor burden of DLBCL and the favorable response rate with substantial treatment-related toxicities of R-CHOP treatment, the prognostic role of cancer cachexia is also likely to be observed in DLBCL patients. Several markers for malnutrition and cachexia such as body mass index (BMI), sarcopenia, adipopenia, and serum albumin level have been studied and suggested to be prognostic factors in DLBCL [14,15,16,17]. Additionally, the clinical value of the Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI), which was originally developed to predict nutrition-related morbidity and mortality in non-cancer patients [18], was evaluated in two previous DLBCL studies with conflicting results [19, 20]. In this study, we re-evaluated the clinical impact of the GNRI on patient outcomes, both alone and in combination with sarcopenia.

Methods

Patients

All DLBCL patients (n = 262) treated with R-CHOP as first-line treatment between 2004 and 2017 at a single institution were retrospectively evaluated. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Gyeongsang National University Hospital. Eligible patients were aged 18 years or older, had baseline CT scans for chest and abdomen, and had the records for height, body weight, and serum albumin level measured within a week before the beginning of R-CHOP (n = 246). Exclusion criteria were patients who had active infections (n = 7), double primary malignancy (n = 4), histologic transformation from low-grade lymphoma (n = 3), and lack of information for the National Comprehensive Cancer Network-International Prognostic Index (NCCN-IPI) at the time of measurement of GNRI and sarcopenia (n = 4). Finally, 228 patients were included in the analysis.

Definitions of clinical variables

Pretreatment demographics and clinical variables were collected via electronic medical records. Body mass index (BMI) of less than 23.0 kg/m2 was classified to be underweight according to the Asian standard [21]. The response to R-CHOP along with any treatment-related toxicities were assessed using the revised International Working Group response criteria and the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (version 4.0). Relative dose intensity (RDI) was defined as the percentage of the actual total dose of each drug relative to the planned dose of the drug. Early treatment discontinuation was defined as any treatment prematurely terminated for reasons not due to disease progression. Treatment-related mortality was defined as any death not due to disease progression occurring within a month of the R-CHOP treatment or as death, at any time, that was apparently related to the R-CHOP treatment.

To determine the extent of sarcopenia, we measured muscle mass by CT histogram analysis, as described previously [16, 22]. Briefly, the muscle masses of the third lumbar level and of the pectoralis major and minor were measured and converted to L3 skeletal muscle index (L3-SMI) and pectoralis muscle SMI (PM-SMI), respectively, by dividing muscle mass by height in meters squared (cm2/m2). The patients were considered to be sarcopenic if their SMIs were lower than their respective cut-off values (L3-SMI, 52.4 cm2/m2 in males and 38.5 cm2/m2 in females; PM-SMI, 4.4 cm2/m2 in males and 3.1 cm2/m2 in females) [16, 22]. The extent of sarcopenia was defined as follows: non-sarcopenia-both, neither L3- nor PM-SMI at sarcopenic level; sarcopenia-L3/PM alone, only one of SMIs at sarcopenic level; and sarcopenia-both, both L3- and PM-SMIs at sarcopenic level [23]. GNRI was estimated using the following formula: 1.489 × serum albumin level (g/L) + 41.7 × [actual body weight (ABW)/ideal body weight (IBW) (kg)]. If the ABW was higher than the IBW, the ABW/IBW ratio was set to 1. According to previous criteria, GNRI scores > 98, 92 to 98, 82 to < 92 and < 82 were classified as no, low, moderate, and major risk, respectively [18].

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed with STATA, version 16.0 (College Station, TX, USA). Mann-Whitney U test and Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test were used to compare continuous and categorical variables between two groups, respectively. Progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated as the time from the date of R-CHOP treatment initiation to the date of progression, death, or last follow-up. Overall survival (OS) was calculated as the time from the date of R-CHOP treatment initiation to the date of death or last follow-up. Survival was plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. Cox regression analysis was performed to assess the influence of clinical variables on PFS and OS. Demographics, NCCN-IPI, and other conventional prognostic factors such as B-symptoms [24], bulky disease [25], and BMI [26] were included on univariate analyses. Each factor of NCCN-IPI such as age, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level, Ann Arbor stage, extranodal disease, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) was not separately analyzed to avoid multicollinearity problem. Then, all statistically significant variables with p-value < 0.05 on univariate analysis were included without variable selection technique in the multivariate Cox regression model. To compare the predictive performance of the models for OS, C-index, Akaike information criterion (AIC), and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) were calculated. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

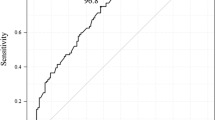

According to the GNRI score, 94, 49, 55, and, 30 patients were classified as no, low, moderate, and major risk groups, respectively. In terms of sarcopenia, 128, 78, and 22 patients were indicated as non-sarcopenia-both, sarcopenia-L3/PM alone, and sarcopenia-both groups, respectively. The mean (± SD) GNRIs were 97.4 (± 8.5), 91.5 (± 10.2), and 83.3 (± 10.0) in non-sarcopenia-both, sarcopenia-L3/PM alone, and sarcopenia-both groups, respectively (p < 0.001). PFS and OS were superior in patients with lower GNRI (Fig. 1a, b) as well as in more sarcopenic patients (Fig. 1c, d). When the survival curves were plotted against the combination of GNRI score and sarcopenic status (Fig. 2a, b), two groups emerged who exhibited significant differences in prognosis. These groups were defined as either the high cachexia risk group (HCR; n = 71, major GNRI risk, sarcopenia-both, or moderate GNRI risk with sarcopenia-L3/PM alone) and low cachexia risk group (LCR; n = 157, others).

a Progression-free survival (PFS) and (b) overall survival (OS) according to the GNRI and severity of sarcopenia. Blue and red circles indicate the groups stratified into low and high cachexia risk, respectively. (c) PFS and (D) OS according to cachexia risk. Abbreviations: GNRI Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index

The baseline characteristics according to the cachexia risk are listed in Table 1. The median age was 64 years (range, 21–88 years), with 132 patients (57.9%) > 60 years old. The majority of patients had a good performance status (ECOG PS 0–1, 71.9%). There were remarkable differences in the baseline characteristics between two groups. The HCR group was associated with adverse clinical features including older age, poor PS, B-symptoms, bulky disease, advanced stage, extranodal disease, elevated LDH level, and higher IPI and NCCN-IPI. The GCB type was observed in 26 of 135 (19.3%) available patients without significant differences between groups. The BMI was lower in the HCR group relative to the LCR group (median BMI, 21.7 vs. 23.9 kg/m2, p < 0.001).

Treatment-related toxicity

Grade 3 or worse treatment-related toxicities were reported more frequently in the HCR group than in the LCR group (Table 2). The rates of grade 3 or worse anemia, febrile neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia were 31.0, 43.7, and 43.7% in the HCR group and 14.7, 26.1, and 18.5% in the LCR groups. Grade 3 or worse non-hematologic toxicities were also more common in the HCR group compared to the LCR group (49.3% vs. 30.6%). Of note, the incidence of treatment-related mortality (19.7% vs. 3.8%) and early treatment discontinuation (43.7% vs. 8.3%) was very high in the HCR group compared with the LCR group.

Treatment response

In all patients, complete response (CR) was achieved in 33 of 71 patients (46.5%) with HCR and in 136 of 157 patients (86.6%) with LCR (p < 0.001, Table 3). CR rates of the LCR group were more than 90% regardless of the RDI of chemotherapy if the treatment was completed as scheduled. In contrast, CR rates of the HCR group were remarkably decreased, as the RDI of chemotherapy was decreased. When the treatment was prematurely discontinued, there were no statistical differences in CR rates between two groups (10.7% vs. 25.0%, p = 0.341).

Survival

There were 104 PFS events and 97 deaths during the study period. With a median follow-up duration of 71.1 months, median PFS and OS of the entire cohort were 87.2 and 89.4 months, respectively. Median PFS in the HCR group was 10.3 months compared with not reached in the LCR group (p < 0.001; Fig. 2c). The 5-year PFS rates were 23.5 and 68.7% in the HCR and LCR groups, respectively. Median OS in the HCR group was 12.9 months and not reached in the LCR group (p < 0.001, Fig. 2d). The 5-year OS rates were 24.4 and 71.6% in the HCR and LCR groups, respectively. While there was no significant difference in OS according to the GNRI in the patients with low to low-intermediate NCCN-IPI, the HCR group had worse OS than the LCR group irrespective of NCCN-IPI (Fig. 3).

Overall survival (OS) according to the GNRI in patients with (a) low to low-intermediate NCCN-IPI and (b) high-intermediate to high NCCN-IPI. OS according to cachexia risk in patients with (c) low to low-intermediate NCCN-IPI and (d) high-intermediate to high NCCN-IPI. Abbreviations: GNRI Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index, NCCN-IPI National Comprehensive Cancer Network-International Prognostic Index

On multivariate analyses, the HCR group was shown to be an independent poor prognostic factor for PFS [hazard ratio (HR) 2.773, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.826–4.212, p < 0.001] and OS (HR 3.348, 95% CI 2.169–5.167, p < 0.001) after adjusting for other covariates including the NCCN-IPI (Table 4). The predictive performance of the model for OS was best (higher C-index and lower AIC and BIC) when the cachexia risk was included in the model, instead of sarcopenia and GNRI (Supplementary Table S1).

Discussion

Our study supports the prognostic role of the GNRI in DLBCL patients. Lower GNRI was associated with worse PFS and OS. Notably, patients who did not meet any of the two criteria for sarcopenia had a favorable prognosis regardless of GNRI score, with the exception of those with major GNRI risk scores, while all patients who met both criteria for sarcopenia had an unfavorable prognosis even in cases of no GNRI risk. In contrast, for patients who met only one of the criteria for sarcopenia, disease prognoses were determined based on GNRI score. Furthermore, the predictive performance was better in the Cox model including the cachexia risk than in those including either sarcopenia or GNRI. These findings suggest that the combined use of GNRI and sarcopenia may improve the predictability of each factor in DLBCL patients.

A previous Japanese study showed that the GNRI score could identify patients with poorer prognosis among those with high-intermediate to high NCCN-IPI [19]. In contrast, a Chinese study found that while there was a marginal difference in OS by univariate analysis, GNRI score was not an independent prognostic factor for OS in multivariate analysis [20]. Given the differences in patient populations and inclusion criteria it is difficult to compare the results of our study directly with those of previous studies; however, there were considerable differences in patient characteristics between studies. The patients in the Chinese study were younger (mean age, 55 years) than those in both the Japanese study and this investigation (median ages, 68 and 64 years, respectively). The proportions of patients with low to low-intermediate NCCN-IPI were 80, 46, and 46.5% in the Chinese, Japanese, and current studies, respectively. In subgroup analyses, the GNRI score could not identify patients with a worse prognosis among those with low to low-intermediate NCCN-IPI in any these studies, whereas there was a significant association between GNRI score and OS among those with high-intermediate to high NCCN-IPI in both the Japanese and current studies. These findings may explain why the prognostic value of GNRI was differently reported in the literature [19, 20] and suggests that the GNRI alone can be a prognostic factor only in DLBCL patients with higher NCCN-IPI.

There is debate about which single parameter for cancer cachexia is most appropriate to predict the prognosis of DLBCL patients. Large database cohort studies reported that patients with low to normal BMI had shorter survival times relative to overweight or obese patients [27, 28], while subset analysis from a phase III trial failed to prove the prognostic role of BMI [29]. Sarcopenia, as determined by CT imaging, has been proposed as an independent prognostic factor in several studies [16, 23, 30, 31]. However, other studies found that the prognostic value of sarcopenia was limited in elderly and male patients [32, 33]. There are also contradictory reports regarding the prognostic role of hypoalbuminemia with various cut-off points [14, 17, 34].

Essentially, multifactorial elements are intricately linked to cancer cachexia. Muscle wasting and atrophy, which are key features in cancer cachexia, are mediated by tumor-derived factors such as proteolysis-inducing factor involving nuclear factor-κB pathway [35, 36]. Tumor-driven inflammatory cytokines are responsible for the development of cancer cachexia by inducing alterations in protein metabolism, as well as by activation of apoptosis and inhibition of regeneration of muscle mass [37]. White adipose tissue browning and lipolysis promoted by tumor-derived cytokines and hormones mediates adipose tissue and muscle wasting through molecular crosstalk between adipose and different tissues [38]. Myostatin expression and activity are enhanced in experimental cancer cachexia, with inhibition sufficient to reduce muscle loss [39, 40]. Furthermore, an international consensus has suggested that the staging criteria of cancer cachexia consist of various clinical factors, including weight loss, BMI, sarcopenia, systemic inflammation, anorexia, response to anticancer therapy, and performance status [10]. Therefore, the cachexia risk of our study, which reflects body weight, sarcopenia, and systemic inflammation may be a better surrogate marker for evaluating the severity of cancer cachexia compared with other single parameters. Cachexia risk was a predictor of treatment response, treatment-related toxicity, and survival in DLBCL. Given the intolerance to R-CHOP treatment observed in patients with high cachexia risk, dose adjustment may be considered in this group. However, chemotherapy dose adjustment resulted in a remarkable decrease of CR rate in the patients with high cachexia risk, whereas there was little effect in those with low cachexia risk. This suggests that a novel therapeutic strategy and intensive supportive care may be warranted in patients with high cachexia risk.

Our study has several limitations. First, the retrospective, non-randomized study design with a relatively small sample size makes it difficult to determine whether the differences in patients’ characteristics between the HCR and LCR groups were caused by potential selection bias or by essential differences between the two groups. In this regard, cachexia risk may be a significant confounding variable. To reduce this potential bias, all consecutive patients who were treated with the same treatment modality were included in this study. Furthermore, the prognostic value of cachexia risk was still significant after adjustment for important covariates and in stratified analysis by the NCCN-IPI. Second, laboratory biomarkers for cachexia and systemic inflammation other than serum albumin were not assessed in our study. Although serum albumin, one of the representative markers for systemic inflammation [41], was used to define cachexia risk in this study, the absence of a biomarker that better reflects the muscle wasting process may weaken the relevance of our risk model for cancer cachexia. To overcome these pitfalls, a prospectively designed study with sufficient power and sample size including various biomarkers for cancer cachexia is needed to validate our findings.

Conclusions

Taken together, the data presented here raise the possibility of the GNRI score as a prognostic factor in DLBCL. In addition, we found that the combined risk model including GNRI and sarcopenia could better predict patient prognosis relative to GNRI alone. These findings emphasize the complexity of cancer cachexia and suggest a close relationship between cachexia, systemic inflammation, and DLBCL.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ABC:

-

Activated B-cell like

- ABW:

-

Actual body weight

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CPA:

-

Cyclophosphamide

- CR:

-

Complete response

- DLBCL:

-

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- DR:

-

Dose reduction

- DXR:

-

Doxorubicin

- ECOG PS:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status

- GCB:

-

Germinal center B-cell like

- GNRI:

-

Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index

- HCR:

-

High cachexia risk

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- IBW:

-

Ideal body weight

- IPI:

-

International Prognostic Index

- LCR:

-

Low cachexia risk

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- NCCN-IPI:

-

National Comprehensive Cancer Network-International Prognostic Index

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- PM:

-

Pectoralis muscle

- R-CHOP:

-

Rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone

- RDI:

-

Relative dose intensity

- SMI:

-

Skeletal muscle index

References

Al-Hamadani M, Habermann TM, Cerhan JR, Macon WR, Maurer MJ, Go RS. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtype distribution, geodemographic patterns, and survival in the US: a longitudinal analysis of the National Cancer Data Base from 1998 to 2011. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:790–5.

Pfreundschuh M, Kuhnt E, Trumper L, Osterborg A, Trneny M, Shepherd L, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy with or without rituximab in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: 6-year results of an open-label randomised study of the MabThera international trial (MInT) group. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:1013–22.

Coiffier B, Thieblemont C, Van Den Neste E, Lepeu G, Plantier I, Castaigne S, et al. Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: a study by the Groupe d'Etudes des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. Blood. 2010;116:2040–5.

International Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Prognostic Factors P. A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:987–94.

Sehn LH, Berry B, Chhanabhai M, Fitzgerald C, Gill K, Hoskins P, et al. The revised international prognostic index (R-IPI) is a better predictor of outcome than the standard IPI for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. Blood. 2007;109:1857–61.

Zhou Z, Sehn LH, Rademaker AW, Gordon LI, Lacasce AS, Crosby-Thompson A, et al. An enhanced international prognostic index (NCCN-IPI) for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated in the rituximab era. Blood. 2014;123:837–42.

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris NL, Stein H, Siebert R, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375–90.

Chapuy B, Stewart C, Dunford AJ, Kim J, Kamburov A, Redd RA, et al. Molecular subtypes of diffuse large B cell lymphoma are associated with distinct pathogenic mechanisms and outcomes. Nat Med. 2018;24:679–90.

Tucci A, Martelli M, Rigacci L, Riccomagno P, Cabras MG, Salvi F, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment is an essential tool to support treatment decisions in elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a prospective multicenter evaluation in 173 patients by the lymphoma Italian Foundation (FIL). Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56:921–6.

Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD, Bosaeus I, Bruera E, Fainsinger RL, et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:489–95.

Chowdhry SM. Chowdhry VK. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care: Cancer cachexia and treatment toxicity; 2019.

Fearon KC, Voss AC, Hustead DS, Cancer Cachexia Study G. Definition of cancer cachexia: effect of weight loss, reduced food intake, and systemic inflammation on functional status and prognosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1345–50.

Silva GAD, Wiegert EVM, Calixto-Lima L, Oliveira LC. Clinical utility of the modified Glasgow Prognostic Score to classify cachexia in patients with advanced cancer in palliative care. Clin Nutr. 2019.

Park S, Han B, Cho JW, Woo SY, Kim S, Kim SJ, et al. Effect of nutritional status on survival outcome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated with rituximab-CHOP. Nutr Cancer. 2014;66:225–33.

Burkart M, Schieber M, Basu S, Shah P, Venugopal P, Borgia JA, et al. Evaluation of the impact of cachexia on clinical outcomes in aggressive lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2019;186:45–53.

Go SI, Park MJ, Song HN, Kim HG, Kang MH, Lee HR, et al. Prognostic impact of sarcopenia in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2016;7:567–76.

Dalia S, Chavez J, Little B, Bello C, Fisher K, Lee JH, et al. Serum albumin retains independent prognostic significance in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the post-rituximab era. Ann Hematol. 2014;93:1305–12.

Bouillanne O, Morineau G, Dupont C, Coulombel I, Vincent JP, Nicolis I, et al. Geriatric nutritional risk index: a new index for evaluating at-risk elderly medical patients. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:777–83.

Kanemasa Y, Shimoyama T, Sasaki Y, Hishima T, Omuro Y. Geriatric nutritional risk index as a prognostic factor in patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2018;97:999–1007.

Li Z, Guo Q, Wei J, Jin J, Wang J. Geriatric nutritional risk index is not an independent predictor in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Biomark. 2018;21:813–20.

Consultation WHOE. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363:157–63.

Prado CM, Lieffers JR, McCargar LJ, Reiman T, Sawyer MB, Martin L, et al. Prevalence and clinical implications of sarcopenic obesity in patients with solid tumours of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:629–35.

Go SI, Park MJ, Song HN, Kim HG, Kang MH, Kang JH, et al. A comparison of pectoralis versus lumbar skeletal muscle indices for defining sarcopenia in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma - two are better than one. Oncotarget. 2017;8:47007–19.

Tomita N, Kodama F, Motomura S, Koharazawa H, Fujita H, Harano H, et al. Prognostic factors in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated by risk-adopted therapy. Intern Med. 2006;45:247–52.

Gaudio F, Giordano A, Perrone T, Pastore D, Curci P, Delia M, et al. High Ki67 index and bulky disease remain significant adverse prognostic factors in patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma before and after the introduction of rituximab. Acta Haematol. 2011;126:44–51.

Hwang HS, Yoon DH, Suh C, Huh J. Body mass index as a prognostic factor in Asian patients treated with chemoimmunotherapy for diffuse large B cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified. Ann Hematol. 2015;94:1655–65.

Carson KR, Bartlett NL, McDonald JR, Luo S, Zeringue A, Liu J, et al. Increased body mass index is associated with improved survival in United States veterans with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3217–22.

Zhou Z, Rademaker AW, Gordon LI, LaCasce AS, Crosby-Thompson A, Vanderplas A, et al. High body mass index in elderly patients with DLBCL treated with rituximab-containing therapy compensates for negative impact of male sex. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2016;14:1274–81.

Hong F, Habermann TM, Gordon LI, Hochster H, Gascoyne RD, Morrison VA, et al. The role of body mass index in survival outcome for lymphoma patients: US intergroup experience. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:669–74.

Lanic H, Kraut-Tauzia J, Modzelewski R, Clatot F, Mareschal S, Picquenot JM, et al. Sarcopenia is an independent prognostic factor in elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55:817–23.

Camus V, Lanic H, Kraut J, Modzelewski R, Clatot F, Picquenot JM, et al. Prognostic impact of fat tissue loss and cachexia assessed by computed tomography scan in elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy. Eur J Haematol. 2014;93:9–18.

Chu MP, Lieffers J, Ghosh S, Belch A, Chua NS, Fontaine A, et al. Skeletal muscle density is an independent predictor of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma outcomes treated with rituximab-based chemoimmunotherapy. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2017;8:298–304.

Nakamura N, Hara T, Shibata Y, Matsumoto T, Nakamura H, Ninomiya S, et al. Sarcopenia is an independent prognostic factor in male patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2015;94:2043–53.

Bairey O, Shacham-Abulafia A, Shpilberg O, Gurion R. Serum albumin level at diagnosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: an important simple prognostic factor. Hematol Oncol. 2016;34:184–92.

Monitto CL, Dong SM, Jen J, Sidransky D. Characterization of a human homologue of proteolysis-inducing factor and its role in cancer cachexia. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5862–9.

Whitehouse AS, Tisdale MJ. Increased expression of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in murine myotubes by proteolysis-inducing factor (PIF) is associated with activation of the transcription factor NF-kappaB. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1116–22.

Argiles JM, Busquets S, Stemmler B, Lopez-Soriano FJ. Cancer cachexia: understanding the molecular basis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:754–62.

Daas SI, Rizeq BR, Nasrallah GK. Adipose tissue dysfunction in cancer cachexia. J Cell Physiol. 2018;234:13–22.

Costelli P, Muscaritoli M, Bonetto A, Penna F, Reffo P, Bossola M, et al. Muscle myostatin signalling is enhanced in experimental cancer cachexia. Eur J Clin Investig. 2008;38:531–8.

Benny Klimek ME, Aydogdu T, Link MJ, Pons M, Koniaris LG, Zimmers TA. Acute inhibition of myostatin-family proteins preserves skeletal muscle in mouse models of cancer cachexia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391:1548–54.

Arroyo V, Garcia-Martinez R, Salvatella X. Human serum albumin, systemic inflammation, and cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2014;61:396–407.

Acknowledgments

The English in this document has been checked by at least two professional editors, both native speakers of English. For a certificate, please see: http://www.textcheck.com/certificate/1AWBlF

Funding

No financial support has been received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conceptualization and design: SG and GL. Data collection: SG, HK, MHK, SP, and GL. Data analysis and interpretation: SG, SP, and GL. Overall supervision: HK, GL. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Gyeongsang National University Hospital and conducted in accordance with the Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Comparison of predictive performance between the Cox regression models for overall survival.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Go, SI., Kim, HG., Kang, M.H. et al. Prognostic model based on the geriatric nutritional risk index and sarcopenia in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. BMC Cancer 20, 439 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-06921-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-06921-2