Abstract

This study was designed to investigate the anti-arrhythmic effect of diosgenin preconditioning in myocardial reperfusion injury in rat, focusing on the involvement of the nitric oxide (NO) system and mitochondrial ATP-dependent potassium (mitoKATP) channels in this scenario. After isolation of the hearts of male Wister rats, the study was conducted in an isolated buffer-perfused heart model. Global ischemia (for 30 min) was induced by interruption of the aortic supply, which was followed by 90-min reperfusion. Throughout the experiment, the electrocardiograms of hearts were monitored using three golden surface electrodes connected to a data acquisition system. Arrhythmias were assessed based on the Lambeth convention and were categorized as number, duration and incidence of ventricular tachycardia (VT), ventricular fibrillation (VF), and premature ventricular complexes (PVC), and arrhythmic score. Additionally, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels in coronary effluent were estimated colorimetrically. Diosgenin pre-administration for 20 min before ischemia reduced the LDH release into the coronary effluent, as compared with control hearts (P < 0.05). In addition, the diosgenin-receiving group showed a lower number of PVC, VT and VF, a reduced duration and incidence of VT and VF, and less severe arrhythmia at reperfusion phase, in comparison with controls. Blocking the mitoKATP channels using 5-hydroxydecanoate as well as inhibiting the NO system through prior administration of l-NAME significantly reduced the positive effects of diosgenin. Our finding showed that pre-administration of diosgenin could provide cardioprotection through anti-arrhythmic effects against ischemia–reperfusion (I/R) injury in isolated rat hearts. In addition, mitoKATP channels and NO system may be the key players in diosgenin-induced cardioprotective mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ischemia–reperfusion (I/R) contributes to tissue injury, morbidity and mortality in a variety of cardiovascular diseases such as myocardial infarction [1]. Tissue injury occurs as a consequence of the initial ischemic insult, which is determined by the magnitude and duration of the interruption in the blood supply, and then subsequent damage induced by reperfusion [2]. During prolonged ischemia, intracellular pH and ATP levels decrease as a result of anaerobic metabolism and lactate accumulation [3]. Therefore, ATPase-dependent ion transport mechanisms become dysfunctional, contributing to increased intracellular and intra-mitochondrial calcium levels (calcium overload), cell swelling and rupture, and cell death by necrotic, necroptotic, apoptotic, and autophagic mechanisms [4]. On the other hand, restoration of oxygen molecules upon reperfusion leads to a surge in the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). In addition, pro-inflammatory mediators such as neutrophils infiltrate into the ischemic tissues and accelerate the I/R injury [5].

The clinical manifestations of I/R injury include myocardial necrosis, myocardial stunning, arrhythmias, and microvascular and endothelial dysfunction. I/R injury is manifested with ventricular arrhythmias in the moments following coronary occlusion and reperfusion [1, 2, 4]. Although the precise mechanisms have not been understood, several factors have already been implicated in this scenario, including the generation of ROS, the rapid washout of K+ and H+ ions from the extracellular space and the accumulation of Ca2+ inside the cell. The rapid washout of extracellular H+ on reperfusion may create an intracellular to extracellular H+ gradient, resulting in an influx of Na+, which in turn would favor an increase in intracellular [Ca2+] via the Na+–Ca2+ exchanger. As a result, the increase in intracellular [Ca2+] has been proposed as a potential culprit for reperfusion arrhythmogenesis. Furthermore, the occurrence of arrhythmias and myocardial infarction might be the direct consequence of increased production of ROS during myocardial ischemia and reperfusion [6]. Free radicals have been implicated in the mechanisms of reversible post-ischemic contractile dysfunction, cardiac cell death, and electrophysiological derangements. Myocardial ischemia-induced arrhythmias may be mitigated by various antiradical interventions, such as inhibition of radical formation or scavenging free radicals [7].

Mitochondria play a pivotal role in cell death as well as cardioprotection [8]. During ischemia, when ATP is depleted, ion pumps cannot function, leading to a rise in intracellular [Ca2+], which further increases ATP depletion [9]. Many studies have suggested that mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K (mitoKATP) channels play an important role in the process of cardioprotection [10, 11, 12, 13]. The precise mechanism by which the mitoKATP channel exerts its protective effects is not clearly understood; however, changes in mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and levels of ROS, and mitochondrial matrix swelling are believed to be involved [1]. In addition to mitoKATP channels, nitric oxide (NO) is a vital signal molecule in cardiovascular system and I/R injury. Many studies have indicated that NO has a dual role in the cardiovascular system; besides its deleterious effects and negative role, it is involved in the mechanisms of protection triggered by cardiac adaptation [14]. The protective action of NO during I/R is due to its potential as an anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory agent [15]. NO acts as an oxygen radical scavenger and also inhibits mitochondrial respiration and thereby reduces the generation of oxygen-derived free radicals during I/R injury [16].

Moreover, pharmacological preconditioning induces a state of protection against I/R injury and has been proposed as a strategy for improving myocardial function [17, 18]. Diosgenin (as a phytoestrogen), which is isolated from wild yams, is structurally similar to estrogen and progesterone [19]. Diosgenin is known to possess important pharmacological roles such as anti-diabetic and anti-hyper-lipidemic activity, the ability to lower plasma cholesterol levels, anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant properties. However, the mechanism of action involved in the pharmacological preconditioning activities induced by diosgenin remains unclear [17]. There is not any study in which the anti-arrhythmic properties of diosgenin have been discussed in I/R injury. Therefore, in the present study we investigated the anti-arrhythmic potential of diosgenin in isolated rat hearts during I/R injury and the contribution of mitoKATP channels and NO system on it.

Materials and methods

Animals

Healthy adult male Wistar rats (250–300 g; 12 weeks old) were used in this study. They were obtained from the animal center of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences and housed in the laboratory under standard animal room conditions (12-h light/dark cycle at 25 °C). All animal experiments and procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Ethics Board at the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Materials

Diosgenin was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). The selective mitoKATP channel and NO system antagonists (5-hydroxydecanoate; 5-HD and l-nitro-arginine methyl ester; l-NAME, respectively), were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Avonmouth, UK). All other chemicals and reagents were obtained from commercial sources at the highest quality available.

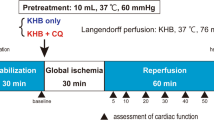

Langendorff perfusion setting

All animals were anesthetized intraperitoneally with sodium pentobarbital (6 mg/100 g) and heparinized with sodium heparin (500 IU). The hearts were excised rapidly via thoracotomy and immersed in ice-cold Krebs–Henseleit solution (K–H). Then the hearts were cannulated via the aorta and perfused with K–H solution that contained (in mmol/l): 118 NaCl, 4.8 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.0 KH2PO4, 27.2 NaHCO3, 10 glucose and 1.25 CaCl2. A mixture of 95 % O2 and 5 % CO2 was bubbled through the perfusate, and the perfusate pH was kept in the range of 7.35–7.45. The hearts were perfused at a constant mean pressure of 75 mmHg throughout the experiment. The thermostatically controlled water circulator (Satchwell Sunvic, UK) maintained the perfusate and bath temperatures at 37 °C.

Experimental design

The animals were randomly divided into the following groups (n = 10/each group):

-

1.

Con (control) — in which after the surgical preparation and 20-min stabilization periods in order to obtain the baseline measurements, the isolated hearts of animals were subjected to a 30-min global ischemia and 90-min reperfusion with a normal K–H solution.

-

2.

EL-C (Cremophor-EL) — in which the condition was similar to the control group except that the hearts were perfused with a K–H solution containing 0.1 %Cremophor-EL (EL-C, as a diosgenin solvent) 20 min before ischemia.

-

3.

Dio — in which the condition was similar to the control group except that the hearts were perfused with a K–H solution containing 0.001 μM diosgenin for 20 min before ischemia.

-

4.

5-HD — in which the condition was similar to the control group except that the hearts were perfused with a K–H solution containing 100 μM 5-hydroxydecanoate (5-HD, as a mitoKATP channel blocker) 20 min before ischemia.

-

5.

Dio + 5-HD — in which the condition was similar to the control group except that the hearts were perfused with a K–H solution containing both 100 μM 5-HD and then 0.001 μM diosgenin for 20 min before ischemia.

-

6.

l-NAME — in which the condition was similar to the control group except that the hearts were perfused with a K–H solution containing 100 μM l-NAME (as a NO synthase blocker) 20 min before ischemia.

-

7.

Dio + l-NAME — in which the condition was similar to the control group except that the hearts were perfused with a K–H solution containing both 100 μM l-NAME and then 0.001 μM diosgenin for 20 min before ischemia.

Exclusion criteria

In the Langendorff setting, exclusion criteria included: isolated hearts with a baseline coronary flow lower than 7.5 ml/min, hearts with weak contraction (left ventricular developed pressure lower than 70 mmHg), and those with irregular heartbeats.

Electrocardiogram recording and arrhythmias interpretation: the Lambeth convention

Electrocardiograms (ECGs) were continuously monitored with three bipolar golden electrodes (two recording and one reference), which were placed close to the apex of the right atrium (RA), on the base (LV1) and on the apex (LV2) of the left ventricle. ECGs were recorded at baseline, during the 30-min ischemia, and during the 90-min reperfusion. Criteria for classification of ventricular arrhythmias were based on the Lambeth conventions [20]. Accordingly, arrhythmias were categorized as a single ventricular premature beat (VPB), ventricular bigeminy (VB), ventricular salvos (VS), ventricular tachycardia (VT; run of 4 or more consecutive VPBs with corresponding effective left ventricular pressure), and ventricular fibrillation (VF; ventricular ECGs of irregular morphology without corresponding effective left ventricular pressure) (Fig. 1). VPB, VB, and VS were all collected and reported as the premature ventricular complexes (PVC) and they were not analyzed separately. ECGs were monitored during the first 30-min of reperfusion phase and analyzed for (1) the count and timing of PVC; (2) the incidence, count, and timing of VT and VF; and (3) the score or severity of arrhythmias. The scoring of arrhythmias was based on a 5-grade evaluation system, as follows: grade 0 for no arrhythmia, grade 1 for VPB, grade 2 for VB or VS, grade 3 for VT, and grade 4 for VF. If there was more than one type of arrhythmia in one sample, the highest grade of arrhythmia was reported.

Measurement of LDH levels

The coronary effluent was collected during the reperfusion period to measure the heart muscle damage indicator, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). The levels of enzyme were determined using commercial kits (Parsazmoon Co., Karaj, Iran) by auto analyzer (Abbott, Alcyon 300, USA), in accordance with the manufacturerʼs protocol. The absorbance of the solution for LDH was detected at 492 nm by a spectrophotometer. The results were reported in U/l.

Statistical analysis

All quantitative data have been presented as mean ± SEM. Differences between incidences of arrhythmias was analyzed by Fisher exact test. The nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test was used to analyze the data for count and duration of arrhythmias between groups. A level of P < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

Effects of diosgenin and blocking of mitoKATP channels and NO system on LDH release

The alterations of LDH release into coronary effluent are shown in Fig. 2. Pre-administration of diosgenin in I/R hearts decreased the LDH release as compared with those of control hearts (P < 0.05). After inhibiting the mitoKATP channels using 5-HD, diosgenin failed to significantly affect on this enzyme (P < 0.05). Blocking the NO system through administration of l-NAME also significantly abolished the effect of diosgenin on LDH level (Fig. 2). It should be noted that the data acquired from the group receiving EL-C (group 2) were not different from those of the control group, and thus were omitted from the result section for simplicity in the interpretation of differences between main groups.

The levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release into the coronary effluent of treated and untreated I/R hearts. n = 10 in each group. * P < 0.05 as compared with control (Con) group; and # P < 0.05 as compared with diosgenin (Dio) group. (In all figures: Con control, Dio diosgenin, 5HD 5-hydroxydecanoate, l -NAME L-nitro-arginine methyl ester)

Effects of diosgenin, and blocking of mitoKATP channels and NO system on the number of PVC, VT and VF

The number of PVCs was decreased in the diosgenin group as compared with controls during the first 30 min of the reperfusion period; however, this finding was not statistically significant. In addition, in comparison with the diosgenin group, the number of PVCs was insignificantly increased after administration of 5-HD and l-NAME as blocking agents of mitoKATP channels and the NO system, respectively (Fig. 3). On the other hand, we found that pretreatment with diosgenin lowered the number of episodes of VT and VF in comparison with controls (Figs. 4, 5, respectively). These changes were significant in relation to the count of VT (P < 0.05), but not VF. Moreover, blocking the mitoKATP channels and NO system significantly abolished the effects of diosgenin on both VT and VF (P < 0.05) (Figs. 4, 5).

Effects of diosgenin, and blocking of mitoKATP channels and NO system on the duration of episodes of VT and VF

Preconditioning with diosgenin decreased the duration of VT and VF episodes during the first 30 min of reperfusion period, compared with controls. The reducing effect of diosgenin on the duration of VT was significant (P < 0.05). After administration of 5-HD or l-NAME, the anti-arrhythmic effects of diosgenin was reduced, so that the duration of VT increased significantly in the Dio + l-NAME group and the duration of VF increased significantly in the Dio + 5-HD group in comparison with the corresponding diosgenin group (P < 0.05) (Figs. 6, 7, respectively).

Effects of diosgenin, and blocking of mitoKATP channels and NO system on the incidence of VT and VF

The effects of diosgenin with or without 5-HD or l-NAME on incidence of VT and VF were similar to each other. In the diosgenin group, only 6 hearts showed VT and 5 hearts showed VF, while all hearts in other groups showed VT. Therefore, the incidence of VT in the diosgenin group was 60 % in comparison with 100 % in the other groups. Similarly, the incidence of VF was 50 % in the diosgenin group, 80 % in the control group and 100 % in the others. Diosgenin decreased the incidence of VT by 40 % and the incidence of VF by 30 % as compared with the control group. Blocking the mitoKATP channels by 5-HD and inhibiting the NO system through l-NAME increased these variables to the controlʼs levels.

Effects of diosgenin, and blocking of mitoKATP channels and NO system on the severity of arrhythmias

Our results showed that diosgenin significantly decreased the severity (score) of arrhythmias as compared with those of controls (2.8 ± 0.4 vs 3.8 ± 0.2; P < 0.05). Blocking both mitoKATP channels by 5-HD and the NO system by l-NAME completely abolished the protective effects of diosgenin on the severity of arrhythmias (4.0 ± 0.0 in both groups; P < 0.05) (Fig. 8).

Discussion

This report showed that diosgenin has anti-arrhythmic effects on isolated rat hearts injured by I/R. The major findings of this study were that diosgenin pre-administration reduced the LDH level and decreased the number, duration and incidence of VT, VF and severity of arrhythmias. In addition, the protective effects of diosgenin were abolished by concomitant administration of 5-HD or l-NAME. Therefore, diosgenin may exert its anti-arrhythmic effects on reperfused hearts through involving the mitoKATP channels and NO system.

I/R injury leads to arrhythmias, transient mechanical dysfunction of the heart, microvascular injury and the ‘‘no-reflow’’ phenomenon, as well as inflammatory responses. In addition, apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy are some causes of cell death in the reperfusion phase of I/R injury. Given that marked improvements in protective strategies to reduce all manifestations of post-ischemic injury in cardiovascular diseases have been developed in recent years [21], a better and safer strategy of developing cardioprotective agents has not yet been outlined. On the other hand, in recent years, diosgenin has become important because of its cardioprotective qualities [22]. The anti-inflammatory function of diosgenin was reported in our previous study in which administration of diosgenin before myocardial ischemia improved cardiac function during reperfusion by lowering the levels of inflammatory mediators IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in an injured myocardium [23]. Additionally, the possible hypo-lipidemic and anti-oxidative effects of diosgenin were investigated on rats fed with a high-cholesterol diet in a study by Son et al. [24]. They reported that diosgenin could be a very useful compound to control hypercholesterolemia, which is a leading cause of cardiovascular diseases, by both improving the lipid profile and modulating oxidative stress. In addition, it was reported in a previous study that diosgenin had a protective effect on ECG alterations in isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in rats through its anti-oxidative properties [25]. Furthermore, the effect of diosgenin on lysosomal hydrolases, membrane-bound enzymes, and electrolytes during isoproterenol-induced myocardial necrosis in rats were assessed by Jayachandran et al. [26]. They concluded that the protective action of diosgenin might be due to the anti-oxidant and membrane stabilizing potential of diosgenin. In our studies, diosgenin showed anti-arrhythmic function in isolated rat hearts. The number, duration and incidence of VT, VF and the severity of arrhythmia were decreased by pre-administration of diosgenin in comparison with controls. Therefore, these results indicated that the anti-arrhythmic and cardioprotective effects of diosgenin may be attributed to its anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative activities. However, the mechanisms underlying the cardioprotective action of diosgenin have not been fully determined.

Over the past decade, an enormous number of studies have focused on the role of NO in the cardiovascular system as a “double edged sword” [27]. Besides its positive roles in cardiac function, some findings recognize that NO can be also cytotoxic, and its abnormal production and action participate in arterial and cardiac pathologies. The toxicity of NO is more likely to result from its reaction with superoxide anions to produce peroxy-nitrite that can exert cytotoxicity via its reaction with numerous molecular targets, and can be potentially injurious to myocardial tissue [14]. However, the evidence showing that NO plays a trigger role in cardioprotection in association with its anti-arrhythmic effect is considerable. There are a number of possible ways by which NO may result in anti-arrhythmic protection [28]. For instance, a possible mechanism might be the elevation of cGMP through the stimulation of soluble guanylyl cyclase by NO [29, 30, 31]. This would reduce energy demand, most likely by limiting myocardial cAMP levels through the stimulation of a cGMP-dependent phosphor-diesterase enzyme [32]. cGMP can also regulate calcium transport through the L-type calcium channels by inhibiting the influx of calcium [32]. The reduction of intracellular calcium accumulation and free radical overproduction during ischemia and reperfusion would result in anti-arrhythmic protection [33]. Reperfusion not only provides the oxygen molecules to reactivate mitochondrial respiration but also causes a large production of oxygen free radicals and a large influx of [Ca2+] in the cytosol [34]. NO acts as an oxygen radical scavenger and anti-inflammatory agent and also inhibits mitochondrial respiration, thereby reducing the generation of oxygen-derived free radicals during I/R injury [16]. In the present study, blocking the NO system by l-NAME abolished the positive anti-arrhythmic effect of diosgenin.

In addition to NO, mitoKATP channels support metabolic function by opening in response to a host of stimuli, including a drop in cytosolic ATP levels or elevation in bioenergetic metabolites and stress-related signals [35]. Although some debates persist regarding the anti-arrhythmic potential of KATP channel opening, the involvement of mitoKATP channel activation in the improvement of cardiac health and performance in the face of acute I/R has been established [36]. Protection is partially attributed to the prevention of re-entrant arrhythmias by mitigating phase 3 of the cardiac action potential during early ischemia and low-flow perfusion [37]. Selective pharmacological blockade of the mitoKATP channel demonstrated an essential role for this channel against arrhythmias [38]. Accordingly, we employed a 30-min ischemia and proportionate reperfusion period to evaluate whether diosgenin exerts its anti-arrhythmic effects through activation of these channels or the NO system. Our results showed that blocking the mitoKATP channel in a similar way to NO system blockade reversed the positive effects of diosgenin on arrhythmic parameters. It is clear that NO increased the activity and opening of the mitoKATP channels via protein kinase G and PKC activation [39, 40]. Therefore, diosgenin may increase the availability of NO by which it enforces the opening of mitoKATP channels, leading to the cardioprotection and anti-arrhythmic effects. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that high levels of oxidative stress deteriorate the outcomes of I/R injury [41, 42]; however, it has been also proposed that free radicals may play a role in the mechanism of cardioprotection. The opening of mitoKATP channels results in mitochondrial generation and release of free radicals which, in turn, could be another explanation of the anti-arrhythmic effect of mitoKATP channels [41, 43, 44].

In conclusion, our findings in this study showed that diosgenin preconditioning in myocardial I/R injury could provide cardioprotection by its anti-arrhythmic effects in isolated rat hearts. We also demonstrated that mitoKATP channels and the NO system may be two key players in diosgenin-induced cardioprotective mechanisms.

References

Perrelli MG, Pagliaro P, Penna C (2011) Ischemia/reperfusion injury and cardioprotective mechanisms: role of mitochondria and reactive oxygen species. World J Cardiol 3:186–200

Murphy E, Steenbergen C (2008) Mechanisms underlying acute protection from cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. Physiol Rev 88:581–609

Murry CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA (1986) Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation 74:1124–1136

Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL (2003) Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet 361:13–20

Burwell LS, Brookes PS (2008) The cardioprotective effects of nitric oxide in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Antioxid Redox Signal 10:579–600

Avkiran M, Ibuki C (1992) Reperfusion-induced arrhythmias: a role for washout of extracellular protons? Circ Res 71:1429–1440

Matejikova J, Kucharska J, Pinterova M, Pancza D, Raninjerova T (2009) Protection against ischemia-induced ventricular arrhythmias and myocardial dysfunction conferred by preconditioning in the rat heart: involvement of mitochondrial K(ATP) channels and reactive oxygen species. Physiol Res 58:9–19

Di Lisa F, Canton M, Menabó R, Kaludercic N, Bernardi P (2007) Mitochondria and cardioprotection. Heart Fail Rev 12:249–260

Grover GJ, Atwal KS, Sleph PG, Wang FL, Monshizadegan H, Monticello T, Green DW (2004) Excessive ATP hydrolysis in ischemic myocardium by mitochondrial F1F0-ATPase: effect of selective pharmacological inhibition of mitochondrial ATPase hydrolase activity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287:H1747–H1755

Ardehali H (2004) Role of the mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channels in cardioprotection. Acta Biochim Pol 51:379–390

Jin C, Wu J, Watanabe M, Okada T, Iesaki T (2012) Mitochondrial K+ channels are involved in ischemic postconditioning in rat hearts. J Physiol Sci 62:325–332

Ma H, Huang X, Li Q, Guan Y, Yuan F, Zhang Y (2011) ATP-dependent potassium channels and mitochondrial permeability transition pores play roles in the cardioprotection of theaflavin in young rat. J Physiol Sci 61:337–342

Jin C, Sonoda S, Fan L, Watanabe M, Kugimiya T, Okada T (2009) Sevoflurane and nitrous oxide exert cardioprotective effects against hypoxia-reoxygenation injury in the isolated rat heart. J Physiol Sci 59:123–129

Andelová E, Barteková M, Pancza D, Styk J, Ravingerová T (2005) The role of NO in ischemia/reperfusion injury in isolated rat heart. Gen Physiol Biophys 24:411

Dana A, Baxter CF, Yellon DM (2001) Delayed or second window preconditioning induced by adenosine A1 receptor activation is independent of early generation of nitric oxide or late induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 38:278–287

Ferdinandy FP, Schulz R (2003) Nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite in myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury and preconditioning. Br J Pharmacol 138:532–543

Esfandiarei M, Lam J, Abdoli Yazdi S, Kariminia A, Navarro Dorado J (2010) Diosgenin modulates vascular smooth muscle cell function by regulating cell viability, migration, and calcium homeostasis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 336:925–939

Hu ZY, Abbott GW, Fang YD, Huang YS, Liu J (2013) Emulsified isoflurane postconditioning produces cardioprotection against myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury in rats. J Physiol Sci 63:251–261

Jung HD, Park HJ, Byun HB, Park YM, Kim TW, Kim BO (2010) Diosgenin inhibits macrophage-derived inflammatory mediators through downregulation of CK2, JNK, NF-κB and AP-1 activation. Int Immunopharmacol 10:1047–1054

Curtis MJ, Hancox JC, Farkas A et al (2013) The Lambeth conventions (II): guidelines for the study of animal and human ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias. Pharmacol Ther 139:213–248

Moens AL, Claeys MJ, Timmermans JP, Vrints CJ (2005) Myocardial ischemia/reperfusion-injury, a clinical view on a complex pathophysiological process. Int J Cardiol 100:179–190

Cayen MN, Ferdinandi ES, Greselin E, Dvornik D (1979) Studies on the disposition of diosgenin in rats, dogs, monkeys and man. Atherosclerosis 33:71–87

Ebrahimi H, Badalzadeh R, Mohammadi M, Yousefi B (2014) Diosgenin attenuates inflammatory response induced by myocardial reperfusion injury: role of mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channels. J Physiol Biochem 70:425–432

Son IS, Kin JH, Sohn HY, Son KH, Kim JS, Kwon CS (2007) Antioxidative and hypolipidemic effects of diosgenin, a steroidal saponin of yam (Dioscorea spp.), on high-cholesterol fed rats. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 71:70472-1–70472-9

Salimeh A, Mohammadi M, Mohaddes G, Badalzadeh R (2011) Protective effect of diosgenin and exercise training on biochemical and ECG alteration in isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in rats. Iran J Basic Med Sci 14:264–274

Jayachandran KS, Vasanthi HR, Rajamanickam CV (2009) Antilipoperoxidative and membrane stabilizing effect of diosgenin, in experimentally induced myocardial infarction. Mol Cell Biochem 327:203–210

Pabla R, Curtis MJ (1995) Effects of NO modulation on cardiac arrhythmias in the rat isolated heart. Circ Res 77:984–992

Végh Á, Szekeres L, Parratt JR (1992) Preconditioning of the ischaemic myocardium; involvement of the L-arginine-nitric oxide pathway. Br J Pharmacol 107:648–652

Pabla R, Bland-Ward P, Moore PK, Curtis MJ (1995) An endogenous protectant effect of cardiac cyclic GMP against reperfusion-induced ventricular fibrillation in the rat heart. Br J Pharmacol 116:2923–2930

Paterson D (2001) Nitric oxide and the autonomic regulation of cardiac excitability. Exp Physiol 86:1–12

Brack KE, Patel VH, Coote JH, Ng GA (2007) Nitric oxide mediates the vagal protective effect on ventricular fibrillation via effects on action potential duration restitution in the rabbit heart. J Physiol 583:695–704

Fischmeister R, Castro L, Abi-Gerges A, Rochais F, Vandecasteele G (2005) Species- and tissue-dependent effects of NO and cyclic GMP on cardiac ion channels. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 142:136–143

Végh Á, Papp JG, Szekeres L, Parratt JR (1992) The local intracoronary administration of methylene blue prevents the pronounced antiarrhythmic effect of ischaemic preconditioning. Br J Pharmacol 107:910–911

Das B, Sarkar C, Karanth KS (2002) Selective mitochondrial K(ATP) channel activation results in antiarrhythmic effect during experimental myocardia ischemia/reperfusion in anesthetized rabbits. Eur J Pharmacol 437:165–171

Kane GC, Liu XK, Yamada S, Olson TM, Terzic A (2005) Cardiac KATP channels in health and disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol 38:937–943

Lu L, Reiter MJ, Xu Y, Chicco A, Greyson CR, Schwartz GG (2008) Thiazolidinedione drugs block cardiac KATP channels and may increase propensity for ischaemic ventricular fibrillation in pigs. Diabetologia 51:675–685

Pasnani JS, Ferrier GR (1992) Differential effects of glyburide on premature beats and ventricular tachycardia in an isolated tissue model of ischemia and reperfusion. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 262:1076–1084

Flagg TP, Nichols CG (2005) Sarcolemmal K(ATP) channels: what do we really know? J Mol Cell Cardiol 39:61–70

Costa AD, Garlid KD, West IC, Lincoln TM, Downey JM, Cohen MV, Critz SD (2005) Protein kinase G transmits the cardioprotective signal from cytosol to mitochondria. Circ Res 97:329–336

Schulza R, Kelmb M, Heusch G (2004) Nitric oxide in myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res 61:402–413

Das B, Sarkar C (2003) Mitochondrial K ATP channel activation is important in the antiarrhythmic and cardioprotective effects of non-hypotensive doses of nicorandil and cromakalim during ischemia/reperfusion: a study in an intact anesthetized rabbit model. Pharmacol Res 47:447–461

Adlam VJ, Harrison JC, Porteous CM, James AM, Smith RA, Murphy MP et al (2005) Targeting an antioxidant to mitochondria decreases cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. FASEB J 19:1088–1095

Pain T, Yang XM, Critz SD, Yue Y, Nakano A, Liu GS et al (2000) Opening of mitochondrial KATP channels triggers the preconditioned state by generating free radicals. Circ Res 87:460–466

Ma H, Huang X, Li Q, Guan Y, Yuan F, Zhang Y (2011) ATP-dependent potassium 454 channels and mitochondrial permeability transition pores play roles in the 455 cardioprotection of theaflavin in young rat. J Physiol Sci 61:337–342

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Badalzadeh, R., Yousefi, B., Majidinia, M. et al. Anti-arrhythmic effect of diosgenin in reperfusion-induced myocardial injury in a rat model: activation of nitric oxide system and mitochondrial KATP channel. J Physiol Sci 64, 393–400 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12576-014-0333-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12576-014-0333-8