Abstract

The study was designed to evaluate the production of auxin by eukaryotic unicellular organism Pichia fermentans. Different media formulations were used for the production of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) under broth and submerged conditions. Wheat straw-based production medium was formulated and optimized using statistical approach. The IAA production was significantly enhanced by nine folds, when the wheat straw was pretreated with Phanerochaete chrysosporium (150 µg/ml) as compared to untreated wheat straw (16.44 µg/ml). Partial purification of IAA was carried out by silica gel column chromatography and further confirmed by high-performance liquid chromatography. Exogenous application of crude and partially purified IAA positively influenced the Vigna radiata seedling growth. The number of lateral roots in the growing seedlings was significantly higher as compared to the control seeds. Thus, the present findings point towards an efficient production of plant hormone by yeast and white rot fungus using abundantly available wheat straw, which may lead to the development of cost-effective production of such metabolites and their further use in agricultural field to reduce the negative impact of chemical fertilizers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Worldwide increased food demands for the growing population have stressed the various agricultural systems to enhance their productivity and yield. The economic losses due to various biotic and abiotic stresses have affected the growth, and productivity of the numerous crops and, thus, the food supply. To deal with this problem several chemical and biological methods have been proposed. Among several methods, the application of auxin (indole-3-acetic acid) as a plant growth regulator is widely acceptable. Auxin is a plant hormone, which mainly includes indole acetic acid (IAA). Some microorganisms have IAA biosynthesis pathway, which converts tryptophan to IAA. IAA can be found in actively growing parts of plant such as apical meristem, young leaves and buds (Müller and Leyser 2011). IAA helps in stimulation of root initiation, cell differentiation, elongation and division, lateral root development, and gravitational responses (El-Tarabily 2008). IAA also acts as a signaling molecule for development of plant structure and overall growth (Teale et al. 2006).

Application of the synthetic indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) has been suggested but its high cost and less stability than synthetic auxin analogs such as 1-naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) limit its practical use (Flasiński and Hac-Wydro 2014). The use of synthetic NAA is also toxic to both human and animal health (Jaishankar et al. 2014). This has raised concern with regard to the toxic contamination of the soil, air, natural water reservoirs and most importantly food crops. Application of eco-friendly technologies in the form of biosynthetic IAA could result as an alternative for synthetic IAA and NAA. Excessive production of IAA in plants is tough and time consuming compared to microorganisms. Therefore, it is of great interest to explore IAA production by microbes. Apart from its synthesis by plants, IAA is also produced by bacteria (Apine and Jadhav 2011), yeast, (Xin et al. 2009) and fungi (Ünyayar et al. 2000; Yürekli et al. 2003; Maor et al. 2004). Applications of IAA-producing yeasts, such as Candida valida, Rhodotorula glutinis, Trichosporon asahii, Lindera saturnus and Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, to promote plant growth have already been reported (Xin et al. 2009). However, information on the production of phytohormones using fermentation is sparse and little data on the IAA synthesized by fungi is known. Earlier, several white rot fungi such as Ganoderma lucidum, Lentinula edodes, Pleurotus ostreatus and Agaricus bisporus were found to have promising antioxidant properties to protect the cells from reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Jayakumar et al. 2009; Jaszek et al. 2014). However, physiological role of auxins in fungi remains unclear. One of the suggested roles for IAA produced by fungus is to mediate fungal–plant interaction thereby favoring the transfer of phytohormones from plant system to soil and vice versa (Fu et al. 2015). High concentrations of IAA can inhibit the hypersensitive response (Jouanneau et al. 1991) and may suppress expression of plant defense genes (Yamada et al. 1985; Shinshi et al. 1987), thus suggesting involvement of IAA in fungal phyto-pathogenicity as well.

Industrial production of IAA is gaining importance as it is widely used in both research and agriculture sectors. Production of secondary metabolites in microbes is faster, easily managed and cost can be minimized. Among different microbes, yeast belonging to Saccharomycetaceae can be a good choice for the production of such compounds as this group of microbes naturally occur in fruits and widely used in fermentation process and also have low risk of pathogenicity (Cousin et al. 2017). Recently, about seven different yeasts including Pichia have been found to be endophytic in nature (Ling et al. 2019). Pichia fermentans is widely present in nature and habitually found in fruits and juices, as well as being connected to humans and animals (Las Heras-Vazquez et al. 2003). Recently, this yeast species was also reported to possess exoelectrogenic property (Pal and Sharma 2019). The species has been successfully used for bio-control of brown rot of apple, but found to be pathogenic when applied to peach fruit (Giobbe et al. 2007). Besides this, P. fermentans is well accepted for the production of wines together with Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Kong et al. 2019). In view of the isolation of P. fermentans from various plant species, it seems likely that this species may have some significant role in plant growth promotion by producing plant growth regulating hormone.

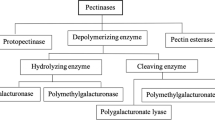

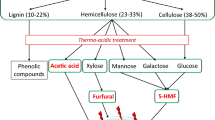

In the industrial processes, production media plays a key role, which is responsible for its high cost. In the present study, an economic medium based on agricultural residues was formulated. Wheat straw as agricultural residue is obtained after harvesting of wheat grains, which has about 529 million tons of global production (Govumoni et al. 2013). Wheat straw contains cellulose (34–40%), hemicellulose (20–25%), and lignin (20%) (Carvalheiro et al. 2009). Among these components, lignin is the most resistant component of plant cell walls, which makes the cellulose like polymers inaccessible for microbial degradation or depolymerization. Few fungi are able to completely degrade lignin to carbon dioxide and thereby increase the accessibility of carbohydrate polymers present in plant cell walls. Selective degradation of lignin is carried out by white rot fungi (Sharma and Arora 2015). Among different white rot fungi, Phanerochaete chrysosporium is known for its selective degradation of lignin and have potential in wide range of biotechnological applications (Sharma et al. 2011). Abundantly available wheat straw can be pretreated using white rot fungi, which converted the complex plant biomass, i.e., cellulose into the easily fermentable sugars glucose (Sadh et al. 2018). P. fermentans may utilize this sugar and may produce IAA in the presence of tryptophan. Besides efficient pretreatment of wheat straw during primary fermentation, P. chrysosporium may also produce IAA in the presence of tryptophan (Chandra et al. 2019), which may further contribute to increase the IAA production during secondary fermentation.

To validate the root proliferating potential of the IAA produced by yeast and fungus, mung bean (Vigna radiata) was used as a model plant, since it is commonly cultivated in the most of the parts of South Asian subcontinent. Owing to its short growing period, these are commonly used for crop rotation to enhance the soil fertility as their roots have symbiotic association with rhizobia (Sharma et al. 2019b).

In the present study, P. chrysosporium pretreated wheat straw was used to produce IAA under submerged fermentation conditions by P. fermentans. After optimizing the production level, the product was isolated and purified using column chromatography and further confirmed by HPLC. IAA produced by Pichia fermentans and P. chrysosporium was exogenously used to evaluate its effect on plant growth.

Materials and methods

Substrate and organisms

Wheat straw (agricultural residue) was collected locally and ground (particle size 2 mm). Pichia fermentans (MTCC 189) was procured from Microbial Type Culture Collection (MTCC), Chandigarh, India, and Phanerochaete chrysosporium (BKM-F-1767) was received from the Center for Forest Mycology Research, USDA Forest Products Laboratory, Madison, Wisconsin. YPD [2% (w/v) peptone, 1% (w/v) yeast extract, 2% (w/v) dextrose] and ME [0.5% (w/v) malt extract] medium were used to grow the pure cultures of P. chrysosporium and P. fermentans, respectively.

Screening of yeast and white rot fungus for IAA production

Yeast and white rot fungus were screened for IAA production as per the method described earlier (Chandra et al. 2019). Flask containing 50 ml of 0.5% (w/v) malt extract were sterilized at 15 lbs/in.2 for 15 min and aseptically amended with tryptophan (0.05% (w/v) (filter sterilized). The flasks were inoculated with P. fermentans (24 h old 1 ml of 1 OD600) or P. chrysosporium (2 mycelial discs of 4-day-old culture), and incubated at 30 °C up to 10 days along with uninoculated control flask. Two ml aliquot was aseptically taken out from the flask at 1-day interval and centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was used for IAA estimation.

IAA production using wheat straw

Flasks containing 1 g wheat straw and 20 ml of 0.1% (w/v) malt extract were sterilized and amended with 0.05% (w/v) tryptophan. P. fermentans or P. chrysosporium were inoculated aseptically and incubated up to 10 days at 30 °C and processed as described in previous step.

Pretreatment of wheat straw

Wheat straw was pretreated with P. chrysosporium under submerged conditions (primary fermentation). Flask containing 2 g wheat straw and 20 ml of 0.1% malt extract (w/v) were inoculated with fungus and then incubated at 30 °C. One ml of the sample was taken out each day to estimate sugar content up to 10 days. A similar set was prepared and P. fermentans was inoculated with tryptophan in the flask on 5th day (as the primary fermentation produced significantly higher sugar on this day) and further incubated for 5 days (secondary fermentation). After incubation, the aliquot was tested for the presence of IAA and the contents of the flask were dried at 80 °C for 48 h to calculate the amount of wheat straw consumed, while the dried residual straw contained degraded straw along with fungal and yeast biomass.

Optimization of conditions for IAA production

On the basis of results obtained from above experiments, three independent variables (distilled water, tryptophan and malt extract) were selected to enhance the production of auxin. The optimization of the selected variables was done as described previously by response surface methodology (RSM) using a Box–Behnken design (Box and Behnken 1960). The experimental design included 15 flasks with 3 center points. Each 100-ml conical flask contained 1 g of wheat straw, 0.1–0.5% (w/v) of malt extract and 15–50 ml of distilled water (Table 1). The flasks were sterilized, inoculated with P. chrysosporium and incubated for 5 days (primary fermentation). Then, P. fermentans was inoculated aseptically along with appropriate concentration of tryptophan (0.1–1% (w/v)) (Table 1) and again incubated for 5 days. The contents of the flasks were filtered and the filtrate was centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 10 min. The obtained supernatant was used for further analyses. Complete experiment was repeated and validated using optimized concentration of supplements. The mathematical relationship of response G (for each parameter) and independent variable X (X1, distilled water; X2, tryptophan; and X3, malt extract) was calculated by the quadratic model equation (Box and Behnken 1960):

where G is the predicted response; \(\beta_{0}\), intercept; \(\beta_{1}\), \(\beta_{2}\), \(\beta_{3}\) and, linear coefficients; \(\beta_{11}\), \(\beta_{22}\) and \(\beta_{33}\), squared coefficients and \(\beta_{12}\), \(\beta_{13}\) and \(\beta_{23}\) interaction coefficients. MINITAB and statistical software package Design Expert® version 8.0 (State ease, Inc., Minneapolis, USA) were used to find out the optimal working conditions and prepare response surface graphs. The predicted concentrations were used to confirm the maximum production of IAA.

Analytical methods

Estimation of IAA

IAA was quantitatively estimated as per the method described earlier (Chandra et al. 2019). Briefly, 1 ml of the supernatant was mixed with the equal amount of Salkowski’s reagent and the OD was read at 530 nm after 30 min of incubation. An uninoculated sample was used as control. The standard IAA was used to prepare a standard curve for quantitative comparison.

Estimation of released sugar content

Reducing sugar content was measured in pretreated wheat straw containing flasks as per the standard protocol using 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNSA) reagent (Miller 1959). Briefly, 1 ml of the supernatant was transferred into separate test tubes containing 2 ml of DNSA reagent (1 g DNSA, 30 g sodium potassium tartrate and 20 ml of 2 M sodium hydroxide to a final volume of 100 ml in distilled water); the test tubes were kept in a water bath for 10 min at 100 °C. After incubation the tubes were allowed to cool down at room temperature and the absorbance was recorded at 540 nm.

Purification of IAA

Partial purification of IAA from crude extract was carried out by silica gel column (22 × 5 cm) using the methanol:water (9:1) as a mobile phase. The flow rate was kept at 1 ml/min and the fractions (2 ml) were collected up to 50 fractions. Each fraction was tested for the presence of IAA using Salkowski’s reagent. The positive fractions were pooled together and evaporated to dry in a rotary evaporator at 60 °C then solubilized in 2 ml of methanol. Presence of IAA was further confirmed by HPLC using C18 column (5 μm; 25 × 0.46 cm) with elution performed using the ratio 9:1 of methanol and water, containing 0.5% acetic acid with a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min and the detection was monitored at 220 nm at 40 °C.

Effect of crude and purified IAA on seedling and root development

Plant growth promotion and root proliferation ability of the crude and purified IAA was assessed in vitro in Petri plates. The Vigna radiata seeds were surface sterilized using 0.1% HgCl2 followed by 4–5 repeated washings with sterilized distilled water. These seeds were treated with crude (150 µg/ml) or purified (100–200 µg/ml) IAA extract and incubated for 7 days at 30 °C, 1 ml sterilized water was added to each plate along with the control. Root length, seedling length and weight were measured after incubations.

Statistical analyses

Except RSM, all the results were represented as mean ± standard error (n = 20). Statistically significant difference was calculated using t test and one-way ANOVA as appropriate. Least significant difference was calculated to find out the statistical significant difference (P < 0.05)

Results

IAA production by yeast and white rot fungus

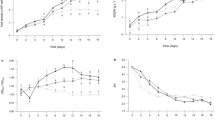

P. fermentans and P. chrysosporium produced IAA in malt extract and wheat straw-based medium supplemented with 0.05% (w/v) tryptophan. P. fermentans and P. chrysosporium produced IAA in the range of 1.99–129.33 µg/ml (Table 2). Maximum production of IAA was observed in medium (without wheat straw) inoculated with P. fermentans on the 6th day (129.33 ± 11.20 µg/ml). On the other hand, P. chrysosporium produced maximum IAA on the 10th day (51.49 ± 3.68 µg/ml) when inoculated in wheat straw-based medium.

Medium formulation using pretreated wheat straw

Wheat straw, the basic component of the medium, was pretreated by P. chrysosporium to release sugar in the medium which may be utilized by P. fermentans for IAA production. P. chrysosporium released a significant amount of sugar from the 2nd day onwards, which increased with time and was maximum (0.89 mg/ml) on the 9th day (Fig. 1). However, it could release five times higher sugar (0.747 mg/ml) from wheat straw after 5 days of incubation (primary fermentation) as compared to uninoculated control (0.152 mg/ml). Thus, the yeast was inoculated on the 5th day after primary fermentation. As a result, IAA production by P. fermentans was significantly enhanced (P < 0.05) by six times after secondary fermentation, when wheat straw was pretreated with P. chrysosporium (128 ± 4.43 µg/ml) as compared to untreated wheat straw (16 ± 0.33 µg/ml). About 20% (w/w) wheat straw was consumed during the 10 days of fermentation process (Fig. 2).

Optimization of the medium using RSM

An enhancement in the IAA production was obtained during RSM experimental design. Based on Eq. (1) multiple regression analysis method was used to analyze the data obtained from Box–Behnken design, which were statistically significant. It was verified by F values and the analysis of variance by fitting the data of all independent observations in response surface quadratic model. \(R^{2}\) value for IAA produced was 95.42%, which showed the appropriateness of the model in the present experiments. For IAA production one linear (\(X_{2}\)) and one squared (\(X_{2}^{2}\)) effect was significant. The plot of predicted versus actual IAA produced (Fig. 3a) demonstrated a high positive correlation between the predicted and actual results. Maximum IAA production (152.36 µg/ml) was obtained at minimum malt extract concentration, maximum tryptophan concentration and 32.5 ml distilled water (Fig. 3b). The optimized values of different factors were validated by executing the experiment and repeating the same with distilled water 32.5 ml, tryptophan 1% and malt extract 0.1% which gave significant IAA produce (150 ± 2.5 µg/ml). Regression coefficients value significance is inversely proportional to the P-values and bears a direct effect with the magnitude of t-value. Hence from Table 3, it can be observed that the linear effect of tryptophan was the most significant (P-value = 0.0003). Quadratic effect was more significant for tryptophan (P-value = 0.0730) followed by malt extract and distilled water. The interaction of tryptophan and malt extract was more significant than that of other factors. The fitness of the model was determined by the coefficient of determination R2. A model having an R2 value higher than 0.9 was considered as very high correlation between experimental value and predicted value from the model (Chen et al., 2009). The R2 value in this model was found to be 0.9542, which depicts that 95.42% of the total variation that occurred in the response value could be explained by the model and the remaining 4.58% is not explained by the model. The ANOVA for the response surface quadratic model is shown in Table 3; the model was highly significant with the P value 0.0074.

Purification of IAA

Fraction number 5 to 15 obtained from column chromatography showed the presence of IAA. These fractions were pooled, and concentrated to 2 ml. HPLC detected the peak at 6.77 min when standard IAA was run (0.1 mg/ml). A peak comparable to standard IAA confirmed the presence of IAA in the methanolic extract (Fig. 4).

Effect of crude and partially purified IAA on seedling and root development

An increase in lateral root count and weight of seedlings as compared to control was observed upon inoculation of seeds with crude and purified IAA (Table 4). All seeds used in the experiments germinated under the experimental conditions. The treated seeds with crude and partially purified IAA showed statistically significant (P < 0.05) increase in the lateral root count, which increased from 5.35 to 14.1 and 17.7, respectively (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Plant-associated yeast might be a good source of plant hormone as confirmed by the experimental results. As reported earlier, Pichia spartinae also influenced the IAA content in the plant (Nakamura et al. 1991). IAA production by yeast has been reported earlier (Pandi et al. 2019), while P. fermentans is being reported for the first time. In the present study, P. fermentans produced high amount of IAA and using fungal pretreated wheat straw positively influenced its production. Pichia guilliermondii and Hanseniaspora uvarum produced less than 25 μg/ml when inoculated in yeast extract-dextrose based medium after 7 days of incubation (Basha and Ramanujam 2015). Also, Williopsis saturnus an endophytic yeast in maize roots was found to be capable of producing IAA (22.51 µg/ml) in vitro in glucose-peptone broth (GPB) medium (Nassar et al. 2005). In the present study a much higher amount of IAA (129.33 µg/ml) was produced by P. fermentans under submerged conditions after 6 days of incubation. However, some phylloplane yeast strains Rhodosporidium fluviale demonstrated efficient IAA (565 mg/L) production (Limtong et al. 2014) almost comparable to P. fermentans as demonstrated in the present study. Similarly, R. paludigenum also produced a sufficient level of IAA (25.4 mg/L/h) under fed-batch fermentation (Nutaratat et al. 2016). Besides IAA production, several rhizosphere yeast strains have also demonstrated plant growth promoting properties, e.g., Sporobolomyces roseus (Perondi et al. 1996), Rhodotorula sp. (Abd El-Hafez and Shehata 2001), Candida valida, Rhodotorula glutinis and Trichosporon asahii (El-Tarabily 2004) have been reported to promote the growth of wheat, tomato and sugar beet, respectively.

Two different pathways for auxin biosynthetic have been proposed for plants: production via indole-3-glycerophosphate and tryptophan-dependent pathways. It differs in the intermediates as: indole-3-pyruvate (IPA) (Woodward and Bartel 2005), tryptamine (TAM), indole-3-acetaldoxime (IAOx) (Zhao et al. 2002), and indole-3-acetamide (IAM) (Pollmann et al. 2009). Another way to convert indole-3-acetonitrile (IAN) into IAA has also been suggested (Mano and Nemoto 2012). Approximately 37.7% of the investigated yeast strains collected from the phyllosphere of various plant species in Thailand produce IAA (Limtong and Koowadjanakul 2012). Three endophytic yeasts isolated from Populus tree also produced IAA when incubated with tryptophan. It suggests that IAA production is common in some yeasts and tryptophan is a major IAA precursor.

White rot species are widely used in biotechnological and biochemical applications, i.e., delignification or bioremediation. However, their application is limited to the production of plant growth promoting factors. Plant growth regulators, e.g., abscisic acid production were reported by some white rot fungi (Crocoll et al. 1991). Besides abscisic acid, Funalia trogii and Trametes versicolor also produced cytokinins, gibberellic acid and indole acetic acid by using olive oil mill and alcohol factory wastewaters as substrate for fermentation (Yürekli et al. 1999). Numerous fungi have demonstrated IAA production, but their biosynthetic pathway and enzyme involved have not been documented (Sukumar et al. 2013). However, researchers have confirmed the presence of IAM and IPA pathways in Colletotrichum gloeosporioides f. sp. aeschynomene. It also revealed that IAM pathway to be a major pathway used this fungus to produce IAA (Robinson et al. 1998). Gas chromatography analyses confirmed the presence of metabolic intermediates of IPA, IAM, and TRA pathways in the culture filtrates of Fusarium delphinoides (Kulkarni et al. 2013).

Production of indole-3-acetic acid by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides f. sp. Aeschynomene was strictly dependent on external tryptophan (Maor et al. 2004). Trichoderma atroviride also produced high level of IAA (6.2, 9.8 and 38.55 µg/ml) in the presence of 200 µg/ml tryptophan, tryptamine and tryptophol, respectively (Gravel et al. 2007). Thus, IAA can be produced when the external tryptophan is available to the fungus. Most of these studies have used costly medium to produce IAA. Earlier, immobilized culture of P. chrysosporium has also been used for the IAA production. The fungi produced maximum auxin on the 18th day (76 µg/ml) (Ünyayar et al. 2000), while the same strain Phanerochaete chrysosporium ME446 demonstrated 0.198 µg IAA/ml in broth medium (Ünyayar 2002). Recently, another wood-degrading basidiomycetes Pleurotus pulmonarius was reported to convert 10 mM tryptophan to approximately 15 μg/ml IAA using, cellulose as a sole carbon source (Pham et al. 2019). Three white rot fungi Pleurotus ostreatus, Phanerochaete chrysosporium and Trametes versicolor produced IAA when plant biomass (Jatropha seed cake) was used as a substrate. Among these fungi, P. chrysosporium produced maximum IAA in Jatropha seed cake-based medium, which took about 15 days for the production, while the other fungi followed P. chrysosporium (Bose et al. 2013). Phlebia species and P. chrysosporium have also been reported to produce maximum IAA (31–20 μg/ml) in complex yeast extract glucose broth (Chandra et al. 2019). Among different white rot fungi, P. chrysosporium is a well-known wood-degrading fungus, which has already been reported to treat wheat straw for various industrial applications (Sharma and Arora 2015). This fungus can degrade lignin, cellulose and hemicelluloses to release a sufficient amount of sugar. Secondly, the IAA production ability of this fungus along with lignocellulosic biomass degradation made P. chrysosporium the preferable choice for wheat straw pretreatment. Pretreatment of complex lignocellulosic biomass may enhance the efficiency of the fermentation process to be used for the production of various secondary metabolites by the microorganisms. Among various pretreatment methods of lignocellulose, the biological method using microorganisms are better in terms of economic and environmental friendly. The co-culture (simultaneous inoculation) of bacteria and/or fungi in bio-processing seems to be highly useful in the breakdown of complex biopolymers because of their high enzyme activity (Sharma et al. 2019a).

Level of IAA produced by P. fermentans under broth and submerged conditions decreased gradually after reaching threshold. This might be due the fact that high IAA concentrations substantially reduced yeast growth (Sun et al. 2014). Previous studies have similarly indicated that IAA inhibits the growth of fungi (Prusty et al. 2004; Kulkarni et al. 2013). Similarly, the fungal strain, P. chrysosporium, was able to grow and produce IAA in the presence of tryptophan up to 10th day of incubation thereafter the IAA production decreased sharply. Besides yeast and fungi, it was observed that IAA production increased gradually from 2nd to 8th day, and decreased thereafter in the case of Pseudomonas putida (Bharucha et al. 2013).

IAA production is regulated by several factors like strain, concentration of precursor, media components, growth stage, etc. (Jasim et al. 2014). Therefore, the medium formulation needs to be optimized to get maximum production under the experimental conditions. In industrial production, downstream processing and the quality of the product is one of the important parameters considered. During HPLC analysis, an adjacent peak was also observed during the analysis, which was also seen in the previous studies. This peak might belong to some related indole compounds (indole lactic acid) as described during the IAA production by fungus Colletotrichum acutatum (Chung et al. 2003).

Shoot length of V. radiata was enhanced during the treatment of fungal strain Trichoderma viride, however, no much change was observed in case of root length (Kumar et al. 2017). As demonstrated earlier, IAA enhanced the seedling length at lower concentrations, while promoted lateral root growth and weight at higher concentrations (Malik and Sindhu 2011). The present study also confirmed the typical behavior of IAA, which enhanced the number of lateral roots and weight of seedlings. Thus, it could be concluded that the effect of exogenous IAA is concentration dependent, where lower concentrations can promote root growth, whereas higher concentrations can inhibit the same. Endogenous IAA produced by plants has a limited amount and is not used directly by plants, while IAA obtained from fungus may be applied as biological fertilizers.

Conclusion

Pichia fermentans and Phanerochaete chrysosporium produced IAA independently. The findings also highlighted the importance of pretreatment of wheat straw by P. chrysosporium, for better IAA production. Exogenous treatment of IAA demonstrated the potential of partially purified compound to increase the number of lateral roots in Vigna radiata seedlings and subsequent plant growth. Thus, the study provides an application of agricultural residue (wheat straw) to be used sued as substrate for the production of plant growth regulating hormone under submerged conditions.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included in the main manuscript file.

Abbreviations

- IAA:

-

Indole-3acetic acid

- HPLC:

-

High performance liquid chromatography

- MTCC:

-

Microbial type culture collection

- OD:

-

Optical density

- DNSA:

-

3,5-Dinitrosalicylic acid

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- IPA:

-

Indole-3-pyruvate

- TAM:

-

Tryptamine

- IAOx:

-

Indole-3-acetaldoxime

- IAM:

-

Indole-3-acetamide

- IAN:

-

Indole-3-acetonitrile

References

Abd El-Hafez AE, Shehata SF (2001) Field evaluation of yeasts as a biofertilizer for some vegetable crops. Arab Univ J Agric Sci 9:169–182

Apine OA, Jadhav JP (2011) Optimization of medium for indole-3-acetic acid production using Pantoea agglomerans strain PVM. J Appl Microbiol. 110:1235–1244

Basha H, Ramanujam B (2015) Growth promotion effect of Pichia guilliermondii in chilli and biocontrol potential of Hanseniaspora uvarum against Colletotrichum capsici causing fruit rot. Biocontrol Sci Technol 25:185–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/09583157.2014.968092

Bharucha U, Patel K, Trivedi UB (2013) Optimization of indole acetic acid production by Pseudomonas putida UB1 and its effect as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria on mustard (Brassica nigra). Agric Res 2:215–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40003-013-0065-7

Bose A, Shah D, Keharia H (2013) Production of indole-3-acetic-acid (IAA) by the white rot fungus Pleurotus ostreatus under submerged condition of Jatropha seedcake. Mycology 4:103–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/21501203.2013.823891

Box GEP, Behnken DW (1960) Some new three level designs for the study of quantitative variables. Technometrics 2:455–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/00401706.1960.10489912

Carvalheiro F, Silva-Fernandes T, Duarte LC, Gírio FM (2009) Wheat straw autohydrolysis: process optimization and products characterization. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 153:84–93

Chandra P, Arora DS, Pal M, Sharma RK (2019) Antioxidant potential and extracellular auxin production by white rot fungi. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 187:531–539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-018-2842-z

Chen XC, Bai JX, Cao JM, Li ZJ, Xiong J, Zhang L, Hong Y, Ying HJ (2009) Medium optimization for the production of cyclic adenosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate by Microbacterium sp. no. 205 using response surface methodology. Biores Technol 100:919–924

Chung KR, Shilts T, Ertürk Ü et al (2003) Indole derivatives produced by the fungus Colletotrichum acutatum causing lime anthracnose and postbloom fruit drop of citrus. FEMS Microbiol Lett 226:23–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00605-0

Cousin F, Le Guellec R, Schlusselhuber M et al (2017) Microorganisms in fermented apple beverages: current knowledge and future directions. Microorganisms 5:39. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms5030039

Crocoll C, Kettner J, Dörffling K (1991) Abscisic acid in saprophytic and parasitic species of fungi. Phytochemistry 30:1059–1060. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9422(00)95171-9

El-Tarabily KA (2004) Suppression of Rhizoctonia solani diseases of sugar beet by antagonistic and plant growth-promoting yeasts. J Appl Microbiol 96:69–75

El-Tarabily KA (2008) Promotion of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) plant growth by rhizosphere competent 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid deaminase-producing streptomycete actinomycetes. Plant Soil 308:161–174

Flasiński M, Hac-Wydro K (2014) Natural vs synthetic auxin: studies on the interactions between plant hormones and biological membrane lipids. Environ Res 133:123–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2014.05.019

Fu S-F, Wei J-Y, Chen H-W et al (2015) Indole-3-acetic acid: a widespread physiological code in interactions of fungi with other organisms. Plant Signal Behav 10:e1048052

Giobbe S, Marceddu S, Scherm B et al (2007) The strange case of a biofilm-forming strain of Pichia fermentans, which controls Monilinia brown rot on apple but is pathogenic on peach fruit. FEMS Yeast Res 7:1389–1398. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1567-1364.2007.00301.x

Govumoni SP, Koti S, Kothagouni SY et al (2013) Evaluation of pretreatment methods for enzymatic saccharification of wheat straw for bioethanol production. Carbohydr Polym 91:646–650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.08.019

Gravel V, Antoun H, Tweddell RJ (2007) Growth stimulation and fruit yield improvement of greenhouse tomato plants by inoculation with Pseudomonas putida or Trichoderma atroviride: possible role of indole acetic acid (IAA). Soil Biol Biochem 39:1968–1977

Jaishankar M, Tseten T, Anbalagan N et al (2014) Toxicity, mechanism and health effects of some heavy metals. Interdiscip Toxicol 7:60–72

Jasim B, Jimtha John C, Shimil V et al (2014) Studies on the factors modulating indole-3-acetic acid production in endophytic bacterial isolates from Piper nigrum and molecular analysis of ipdc gene. J Appl Microbiol 117:786–799. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.12569

Jaszek M, Kos K, Matuszewska A, Grąz M, Stefaniuk D, Osińska-Jaroszuk M, Prendecka M, Jóźwik E, Grzywnowicz K (2014) Effective stimulation of the biotechnological potential of the medicinal white rot fungus: Phellinus pini by menadione-mediated oxidative stress. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 174:644–656

Jayakumar T, Thomas PA, Geraldine P (2009) In-vitro antioxidant activities of an ethanolic extract of the oyster mushroom, Pleurotus ostreatus. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol 10:228–234

Jouanneau JP, Lapous D, Guern J (1991) In plant protoplasts, the spontaneous expression of defense reactions and the responsiveness to exogenous elicitors are under auxin control. Plant Physiol 96:459–466

Kong CL, Li AH, Su J et al (2019) Flavor modification of dry red wine from Chinese spine grape by mixed fermentation with Pichia fermentans and S. cerevisiae. LWT 109:83–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2019.03.101

Kulkarni GB, Sanjeevkumar S, Kirankumar B et al (2013) Indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis in Fusarium delphinoides strain GPK, a causal agent of wilt in chickpea. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 169:1292–1305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-012-0037-6

Kumar NV, Rajam KS, Rani ME (2017) Plant growth promotion efficacy of indole acetic acid (IAA) produced by a mangrove associated fungi-Trichoderma viride VKF3. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci 6(11):2692–2701

Las Heras-Vazquez FJ, Mingorance-Cazorla L, Clemente-Jimenez JM, Rodriguez-Vico F (2003) Identification of yeast species from orange fruit and juice by RFLP and sequence analysis of the 5.8S rRNA gene and the two internal transcribed spacers. FEMS Yeast Res 3:3–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1567-1356(02)00134-4

Limtong S, Koowadjanakul N (2012) Yeasts from phylloplane and their capability to produce indole-3-acetic acid. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 28:3323–3335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-012-1144-9

Limtong S, Kaewwichian R, Yongmanitchai W, Kawasaki H (2014) Diversity of culturable yeasts in phylloplane of sugarcane in Thailand and their capability to produce indole-3-acetic acid. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 30:1785–1796. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-014-1602-7

Ling L, Li Z, Jiao Z et al (2019) Identification of novel endophytic yeast strains from tangerine peel. Curr Microbiol 76:1066–1072. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-019-01721-9

Malik DK, Sindhu SS (2011) Production of indole acetic acid by Pseudomonas sp.: effect of coinoculation with Mesorhizobium sp. Cicer on nodulation and plant growth of chickpea (Cicer arietinum). Physiol Mol Biol Plants 17:25–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12298-010-0041-7

Mano Y, Nemoto K (2012) The pathway of auxin biosynthesis in plants. J Exp Bot 63:2853–2872

Maor R, Haskin S, Levi-Kedmi H, Sharon A (2004) In planta production of indole-3-acetic acid by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides f. sp. aeschynomene. App Environ Microbiol. 70:1852–1854

Miller GL (1959) Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal Chem 31:426–428. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac60147a030

Müller D, Leyser O (2011) Auxin, cytokinin and the control of shoot branching. Ann Bot 107:1203–1212

Nakamura T, Murakami T, Saotome M et al (1991) Identification of indole-3-acetic acid in Pichia spartinae, an ascosporogenous yeast from Spartina alterniflora marshland environments. Mycologia 83:662. https://doi.org/10.2307/3760223

Nassar AH, El-Tarabily KA, Sivasithamparam K (2005) Promotion of plant growth by an auxin-producing isolate of the yeast Williopsis saturnus endophytic in maize (Zea mays L.) roots. Biol Fertil Soils 42(2):97–108

Nutaratat P, Srisuk N, Arunrattiyakorn P, Limtong S (2016) Fed-batch fermentation of indole-3-acetic acid production in stirred tank fermenter by red yeast Rhodosporidium paludigenum. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng 21:414–421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12257-015-0819-0

Pal M, Sharma RK (2019) Exoelectrogenic response of Pichia fermentans influenced by mediator and reactor design. J Biosci Bioeng 127:714–720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiosc.2018.11.004

Pandi R, Velu G, Devi P, Dananjeyan B (2019) Isolation and screening of soil yeasts for plant growth promoting traits. Madras Agric J. https://doi.org/10.29321/maj.2019.000289

Perondi NL, Luz WC, Thomas R (1996) Microbiological control of Gibberella in wheat. Fitopatol Bras 21:243–249

Pham MT, Huang CM, Kirschner R (2019) The plant growth-promoting potential of the mesophilic wood-rot mushroom Pleurotus pulmonarius. J Appl Microbiol 127:1157–1171. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.14375

Pollmann S, Düchting P, Weiler EW (2009) Tryptophan-dependent indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis by “IAA-synthase” proceeds via indole-3-acetamide. Phytochemistry 70:523–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.01.021

Prusty R, Grisafi P, Fink GR (2004) The plant hormone indoleacetic acid induces invasive growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci 101(12):4153–4157

Robinson M, Riov J, Sharon A (1998) Indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis in Colletotrichum gloeosporioides f. sp. aeschynomene. Appl Environ Microbiol 64:5030–5032

Sadh PK, Duhan S, Duhan JS (2018) Agro-industrial wastes and their utilization using solid state fermentation: a review. Bioresour Bioprocess 5:1

Sharma RK, Arora DS (2015) Fungal degradation of lignocellulosic residues: an aspect of improved nutritive quality. Crit Rev Microbiol 41:52–60. https://doi.org/10.3109/1040841X.2013.791247

Sharma RK, Chandra P, Arora DS (2011) Antioxidant properties and nutritional value of wheat straw bioprocessed by Phanerochaete chrysosporium and Daedalea flavida. J Gen Appl Microbiol 56:519–523. https://doi.org/10.2323/jgam.56.519

Sharma HK, Xu C, Qin W (2019a) Biological pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for biofuels and bioproducts: an overview. Waste Biomass Valorization 10:235–251

Sharma RK, Barot K, Archana G (2019b) Root colonization by heavy metal resistant Enterobacter and its influence on metal induced oxidative stress on Cajanus cajan. J Sci Food Agric. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.10161

Shinshi H, Mohnen D, Meins F (1987) Regulation of a plant pathogenesis related enzyme: inhibition of chitinase and chitinase mRNA accumulation in cultured tobacco tissues by auxin and cytokinin. Proc Natl Acad Sci 84:89–93

Sukumar P, Legué V, Vayssières A et al (2013) Involvement of auxin pathways in modulating root architecture during beneficial plant-microorganism interactions. Plant Cell Environ 36:909–919. https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.12036

Sun PF, Fang WT, Shin LY, Wei JY, Fu SF, Chou JY (2014) Indole-3-acetic acid-producing yeasts in the phyllosphere of the carnivorous plant Drosera indica L. PLoS ONE 9(12):e114196

Teale WD, Paponov IA, Palme K (2006) Auxin in action: signalling, transport and the control of plant growth and development. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7:847–859

Ünyayar S (2002) Changes in abscisic acid and indole-3-acetic acid concentrations in Funalia trogii (Berk.) Bondartsev & Singer and Phanerochaete chrysosporium Burds. ME446 subjected to salt stress. Turk J Botany 26:1–4

Ünyayar S, Ünal E, Ünyayar A (2000) Production of auxin and abscisic acid by Phanerochaete chrysosporium ME446 immobilized on polyurethane foam. Turkish J Biol 24:769–774

Woodward AW, Bartel B (2005) Auxin: regulation, action, and interaction. Ann Bot 95:707–735

Xin G, Glawe D, Doty SL (2009) Characterization of three endophytic, indole-3-acetic acid-producing yeasts occurring in Populus trees. Mycol Res 113:973–980

Yamada T, Palm C, Brooks B, Kosuge T (1985) Nucleotide sequences of the Pseudomonas savastanoi indole acetic acid genes show homology with Agrobacterium tumefaciens TDNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci 82:6522–6526

Yürekli F, Yesilada O, Yürekli M, Topcuoglu SF (1999) Plant growth hormone production from olive oil mill and alcohol factory wastewaters by white rot fungi. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 15:503–505. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008952732015

Yürekli F, Geckil H, Topcuoglu F (2003) The synthesis of indole-3-acetic acid by the industrially important white-rot fungus Lentinus sajor-caju under different culture conditions. Mycol Res 107:305–309

Zhao Y, Hull AK, Gupta NR et al (2002) Trp-dependent auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis: involvement of cytochrome P450s CYP79B2 and CYP79B3. Genes Dev 16:3100–3112. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.1035402

Acknowledgements

Central Analytical Facility, Manipal University Jaipur, is acknowledged for HPLC analysis.

Funding

RKS is thankful to Manipal University Jaipur for providing Enhanced Seed Grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RG performed the experimental work, recorded and compiled the all the data and drafted the manuscript. RKS designed the experiment, analyzed the data and finalized the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Giri, R., Sharma, R.K. Fungal pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for the production of plant hormone by Pichia fermentans under submerged conditions. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 7, 30 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643-020-00319-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643-020-00319-5