Abstract

Background

Knowledge translation (KT) strategies are widely used to facilitate the implementation of EBIs into healthcare practices. However, it is unknown what and how KT strategies are used to facilitate the sustainability of EBIs in institutional healthcare settings.

Objectives

This scoping review aimed to consolidate the current evidence on (i) what and how KT strategies are being used for the sustainability of EBIs in institutional healthcare settings; (ii) the reported KT strategy outcomes (e.g., acceptability) for EBI sustainability, and (iii) the reported EBI sustainability outcomes (e.g., EBI activities or component of the intervention continue).

Methods

We conducted a scoping review of five electronic databases. We included studies describing the use of specific KT strategies to facilitate the sustainability of EBIs (more than 1-year post-implementation). We coded KT strategies using the clustered ERIC taxonomy and AIMD framework, we coded KT strategy outcomes using Tierney et al.’s measures, and EBI sustainability outcomes using Scheirer and Dearing’s and Lennox’s taxonomy. We conducted descriptive numerical summaries and a narrative synthesis to analyze the results.

Results

The search identified 3776 studies for review. Following the screening, 25 studies (reported in 27 papers due to two companion reports) met the final inclusion criteria. Most studies used multi-component KT strategies for EBI sustainability (n = 24). The most common ERIC KT strategy clusters were to train and educate stakeholders (n = 38) and develop stakeholder interrelationships (n = 34). Education was the most widely used KT strategy (n = 17). Many studies (n = 11) did not clearly report whether they used different or the same KT strategies between EBI implementation and sustainability. Seven studies adapted KT strategies from implementation to sustainability efforts. Only two studies reported using a new KT strategy for EBI sustainability. The most reported KT strategy outcomes were acceptability (n = 10), sustainability (n = 5); and adoption (n = 4). The most commonly measured EBI sustainability outcome was the continuation of EBI activities or components (n = 23), followed by continued benefits for patients, staff, and stakeholders (n = 22).

Conclusions

Our review provides insight into a conceptual problem where initial EBI implementation and sustainability are considered as two discrete time periods. Our findings show we need to consider EBI implementation and sustainability as a continuum and design and select KT strategies with this in mind. Our review has emphasized areas that require further research (e.g., KT strategy adaptation for EBI sustainability). To advance understanding of how to employ KT strategies for EBI sustainability, we recommend clearly reporting the dose, frequency, adaptations, fidelity, and cost of KT strategies. Advancing our understanding in this area would facilitate better design, selection, tailored, and adapted use of KT strategies for EBI sustainability, thereby contributing to improved patient, provider, and health system outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Evidence-based interventions (EBIs) are innovations, practices, programs, or policies with proven efficacy and effectiveness [1]. Despite enormous investments in the development of EBIs for healthcare improvement, 60% of care provided is aligned with the best evidence, 30% of care is wasteful or inappropriate and 10% is harmful [2, 3]. Furthermore, only 23% of EBIs are sustained 2 years after initial implementation, leading to unnecessary healthcare waste and reduced benefits for patients, providers, and systems [4].

To address these gaps, knowledge translation (KT) focuses on the application of innovation to practice or policy to improve patients’ health outcomes and strengthen the healthcare system with more effective health services and EBIs [5]. KT occurs through a dynamic and iterative process of knowledge synthesis, dissemination, and exchange between researchers, decision-makers, and knowledge users [6]. A central goal of KT is to ensure that stakeholders are aware of and use research evidence to inform their health and healthcare decision-making. Stakeholders for KT, include policymakers, professionals, patients, family members, informal carers, researchers, and industry [7]. KT strategies are approaches designed to promote the use of EBIs in healthcare practices and policy and to help close research-practice gaps (i.e., what we know versus what we do) [7]. KT strategies can be single or multifaceted in nature, target multiple levels (individual, team, system), and focus on the implementation, adoption, and/or sustainability of an EBI [8, 9].

Taxonomies such as the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) [10, 11] have been developed to establish a common classification system for KT strategy terms, definitions, and categories. Examples of KT strategies include (1) audit and feedback: where data is summarized about specific aspects of practice and provided to practitioners to encourage practice change [12,13,14,15,16], (2) facilitation: where an internal and/or external person acts as enabler for the process of implementation [12], and (3) educational outreach: where a trained person or expert visits practice settings and provides information, such as new evidence to change practice [16]. There is an abundance of evidence on the varying degrees of effectiveness of different types of KT strategies [15, 17,18,19] used to facilitate the implementation of various EBIs with different stakeholders such as nurses [20, 21], physicians [22, 23], and allied health [24] for various health conditions [25, 26] across different health contexts [27, 28]. Recent synthesis efforts have identified KT strategies used to facilitate the sustainability (long-term use and benefits) of EBIs in public health [29, 30], and for chronic diseases [31]. Most recently a synthesis on the efficacy of sustained knowledge translation (KT) strategies in chronic disease management found that over the long term, continuing to use KT strategies was rarely defined and infrequently assessed, suggesting fundamental gaps in knowledge [32]. There is no synthesized and consolidated empirical evidence on what and how KT strategies are used to facilitate the sustainability of EBIs in institutional healthcare settings (e.g., hospital organizations and long-term care facilities). Given that most of the healthcare EBIs are implemented in institutional healthcare settings it is important to understand, what and how KT strategies facilitate EBI sustainability in these contexts.

Sustainability is a priority issue for health services research and has been described as “one of the most significant translational research problems of our time” 33 (pg. 89). Over the last decade, less than 1% of research has focused on the sustainability of EBIs for healthcare [4, 33, 34]. One challenge with sustainability research has been the variation in its conceptualization resulting in operationalization and measurement challenges. As a result, Moore et al. developed a comprehensive definition that states that sustainability occurs when an EBI continues to be delivered and maintained after a defined time, during which the EBI and individual and collective behavior change may evolve or adapt while continuing to produce benefits for individuals/systems [35] (pg. 114). Our review is guided by this multicomponent definition of sustainability.

It is unclear if there are similarities and differences between KT strategies used to facilitate implementation (initial use of EBIs) and strategies used to facilitate the sustainability (ongoing use) of EBIs for healthcare. It is also unknown if the same KT strategies can support both implementation and sustainability or if specific KT sustainability strategies need to be developed and used. There is a need for this evidence to inform the selection, design, and use of KT strategies to facilitate the ongoing use of EBIs in institutional healthcare settings.

This scoping review aimed to consolidate the current evidence on (i) what and how KT strategies are being used for the sustainability of different EBIs across various institutional healthcare settings; (ii) what KT strategy outcomes (i.e., feasibility, acceptability, appropriateness, fidelity, adoption, cost) are reported on for the sustainability of EBIs in institutional healthcare settings; and (iii) what EBI sustainability outcomes (i.e., continuation of benefits for patients) are reported in the current evidence base. The rationale for looking at both KT strategy outcomes (e.g., the feasibility of external facilitators for the sustainability of an EBI) and EBI sustainability outcomes (e.g., the continuation of benefits for patients, staff, and stakeholders as a result of the EBI) is to understand how acceptable, feasible, etc. the KT strategy was or not for supporting EBI sustainability and whether the EBI itself continued to produce improved outcomes for patients, practices, and policy. A scoping review was deemed to be the appropriate method as it allowed for examination of the “extent, range and nature of research activity” in the use of KT strategies for the sustainability of EBIs in institutional healthcare settings (i.e., hospital organizations and long-term care settings) [36]. The key terms used for this review are presented in Table 1.

Research aims and context

The following research questions guided this review:

-

1.

What KT strategies have been used to facilitate the sustainability of EBIs in institutional healthcare settings within peer-reviewed publications?

-

2.

How have KT strategies been used to facilitate the sustainability of EBIs in institutional healthcare settings?

-

3.

What KT strategy outcomes are reported in the included studies?

-

4.

What sustainability outcomes of the EBI are reported in the included studies?

Methods

We conducted this scoping review using the Arksey and O’Malley framework [36] for conducting scoping reviews and the Joanna Briggs Institute Methodology for Scoping Reviews [42]. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow chart [43] and the PRISMA for Searching (PRISMA-S) extension (Additional file 1) [44] to guide the reporting of our scoping review. There is no published protocol for this review.

To identify relevant studies, we developed inclusion and exclusion criteria based on the population, concept, and context mnemonic recommended by the Joanna Briggs Institute Methodology for Scoping Reviews [42] (Table 2).

Search methods

The search methods for this review are in adherence to the PRISMA for Searching (PRISMA-S) extension [44] An experienced health sciences librarian (MK) conducted comprehensive systematic searches in November 2021. She searched the following databases from inception to November 3rd, 2021: Medline and EMBASE via OVID; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) via EBSCOhost; Scopus via Elsevier; Cochrane Library via Wiley. In consultation with the research team, MK created a robust search strategy derived from three main concepts: (1) program or initiative sustainability, including long-term changes or continuous adoption; (2) knowledge translation or transfer, quality improvement, organizational change, implementation, implementation science, diffusion of innovation, and other related knowledge translation terminology; (3) evidence-based, evidence-informed, or evidence-supported practice, including searching for clinical pathways and healthcare policies. Databases were searched using a combination of natural language terms (keywords) and controlled terms (subject headings, e.g., MeSH), wherever they were available. No language or publication date limits were applied. Study type limits were not applied but items such as news reports, opinion pieces, editorials, notes, and conference materials were removed from the results. We also hand-searched the reference lists of included papers to identify additional records. See Additional file 2 for the full search strategy by database.

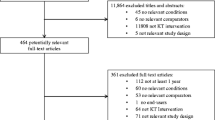

Study selection

We exported the search results from each database in complete batches and imported them to the systematic review management software, Covidence [45] to identify and remove duplicate records and to facilitate title/abstract and full-text screening. Overall, we identified 7704 records through database searches and removed 3846 records as duplicates, leaving 3858 records for title/abstract screening. Two independent reviewers (LD and JAR) screened titles and abstracts for assessment against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. We only included studies that reported on an EBI defined as a practice, program, innovation, or policy that had been established as effective through previous research. Two independent reviewers (LD and JAR) assessed the full text of selected studies in detail against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. We recorded the reasons for exclusion directly in Covidence. We resolved any disagreements between the reviewers at each stage of the selection process through discussion, or by a third and fourth reviewer (CC and RF).

Data extraction and analysis

We used a data extraction tool developed by the research team to extract data from the included studies, using Microsoft Excel. We initially piloted the data extraction tool with five studies and modified it as needed. Two reviewers independently extracted (LD, JL) the following study information: author(s); year of publication; country of origin; study aim/purpose; study discipline and; level of analysis (individual, team or organizational); study setting; reporting of sex/gender; design and length of study; description of evidence-based intervention; description of KT strategy; the aims, ingredients, mechanism, and delivery of the KT strategies; description of KT strategy outcomes, description of EBI sustainability outcomes. A third and fourth reviewers resolved any questions or discrepancies (CC, RF).

Two reviewers (LD, JL) used several frameworks and taxonomies to chart and analyze the extracted data advised by (RF, CC, IDG, and SDS) (see Table 3). We used the AIMD framework [47] to extract details about the KT strategy, including the aim, ingredients, mechanisms, and delivery. Next, we used the Clustered ERIC taxonomy [10] to classify the KT strategies by the following nine clusters: (1) use of evaluative and iterative strategies; (2) provide interactive assistance; (3) adapt and tailor to context; (4) develop stakeholder interrelationships; (5) train and educate stakeholders; (6) support clinicians; (7) engage consumers; (8) utilize financial strategies; (9) change infrastructure. We used Tierney et al.’s [49] 10 implementation measures recommended to extract when conducting evidence syntheses to extract and report the KT strategy outcomes used in the included studies: (1) acceptability, (2) adoption, (3) appropriateness, (4) feasibility, (5) fidelity, (6) implementation cost, (7) intervention complexity, (8) penetration, (9) reach, and (10) sustainability of KT strategies [NO_PRINTED_FORM]. We used Scheirer and Dearing’s taxonomy (expanded by Lennox et al.) [34, 48] to extract and report the sustainability outcomes of the EBI: (1) Benefits for patients, staff and stakeholders continue, (2) activities or components of the EBI continue, (3) maintenance of relationships, partnerships, or networks, (4) maintenance of new procedures, and policies, (5) attention and awareness of the problem or issue are continued or increased, (6) replication, roll-out or scale-up of the EBI, (7) capacity built within staff, stakeholders and communities continues, (8) adaptation of the EBI in response to new evidence or contextual influences and (9) gaining further funds to continue the EBI and maintain improvements.

Further, we extracted additional information on the reported KT strategies, including (1) whether the same KT strategies were used for implementation and sustainability, (2) new KT strategies were introduced for sustainability, or (3) adaptations were made to the KT strategies to support sustainability of the EBI. We produced descriptive numerical summaries of the quantitative data (i.e., frequency of KT strategy, barriers and facilitators, and outcomes). Next, we conducted deductive content analysis to categorize qualitative data into the respective frameworks and taxonomies and reported these narratively and in tabular formats [50].

Results

After the removal of duplicates, we screened 3858 titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria. 82 studies were included for full-text screening. From this set, we excluded 57 studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria. In total, 25 studies (reported in 27 papers due to 2 companion reports) met the final inclusion criteria for the review (Fig. 1) [51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77].

Study characteristics

Study characteristic details are described in Table 4. All 25 studies were published between 2011 and 2021 (Fig. 2). The 25 included studies reported on 16 health disciplines. Most studies focused on the adult population (n = 16) [51, 55,56,57, 59, 61, 62, 64, 66,67,68,69,70,71, 73, 74], while fewer had a pediatric focus (n = 8) [53, 58, 60, 63, 65, 72, 75, 77], and one reported on the neonatal intensive care unit [76]. Thirteen of the included studies took place in acute care [55, 57, 60,61,62, 66, 68, 69, 71, 73, 75,76,77], 11 in tertiary care [51, 53, 56, 58, 59, 63,64,65, 70, 72, 74], and 1 in ambulatory care [67]. Fifty-two percent (n = 13) [53, 56,57,58, 61,62,63, 65, 67, 71, 75,76,77] of the included studies were published in the USA, with the remaining (n = 12) published in Australia (n = 2) [68, 74], Canada (n = 2) [60, 69], Italy (n = 2) [66, 72], Sweden (n = 2) [59, 73], Spain (n = 1) [70], United Kingdom (n = 1) [64], Netherland (n = 1) [51], and Northern Ireland (n = 1) [55]. Mixed method research was the most common study design (n = 8) [51, 57,58,59, 67, 71, 74, 75]. Other study designs included quantitative descriptive (n = 8) [53, 56, 63, 65, 66, 68, 70, 76], quantitative non-randomized (n = 4) [62, 69, 72, 73], qualitative (n = 3) [55, 64, 77], and cluster randomized control trials (n = 2) [60, 61]. While many studies did not explicitly define sustainability (n = 11) [53, 57, 58, 63, 64, 69,70,71,72,73, 76], all included studies reported on sustainability of an EBI from 1 to 10 years post-implementation, with 5–9 years being the most commonly reported timeframe (n = 8) [51, 53, 56, 62, 66, 68, 74, 76], and a median reported timeframe of 4 years. The most common types of EBIs were practice guidelines (n = 12) and care pathways (n = 8).

KT strategies to facilitate the sustainability of EBIs

Table 5 reports on the KT strategies used to facilitate sustainability and an additional file describes the reported aims, ingredients, mechanism, and delivery of the KT strategies [see Additional file 3]. Among the 25 studies, 66 KT strategies were used. Most studies employed multi-component KT strategies and only one study reported a single-component KT strategy (education) [65]. The three most common KT strategy clusters, as per the ERIC taxonomy [10] were training and educating stakeholders (n = 38), developing stakeholder interrelationships (n = 33), and the use of evaluative and iterative strategies (n = 29). Under the ERIC KT strategy cluster of train and educating stakeholders (n = 38), formal education such as seminars and modules were the most common modes of delivery for training and educating staff (n = 19) with the aim of increasing awareness on the EBI. Other popular education-related KT strategies were delivered via pocket cards (n = 3) and EBI-specific toolkits (n = 2). Under the ERIC KT strategy cluster of the development of stakeholder interrelationships (n = 33), EBI champions (n = 13) and multidisciplinary teams (n = 7) were the most common KT strategies used for the sustainability of the EBI, while under the cluster of evaluative and iterative KT strategy, audit and feedback (n = 16) were the most frequently reported. Other KT strategies used for the sustainability of the EBI were clinician support, specifically leadership support (n = 9), ongoing reminders (n = 6), and EBI facilitators (n = 5).

Few studies reported explicit details on how the KT strategy was delivered, including the dose and frequency of the KT strategy (see Additional file 3). For example, Becker et al. and MacDonald et al. described having EBI champions lead monthly meetings with staff [67, 71]. Schnipper et al. reported detailed training activities, including three peer-to-peer webinars and four regional workshops [57]. Other studies provided some detail on how they conducted audit and feedback strategies for EBI sustainability, including how often the audit occurred and how feedback was shared [55, 59, 62, 67, 76]. From a synthesis of the qualitative data across the included studies, ongoing reminders (verbal, visual, and electronic) that were provided by local champions were reported to facilitate the sustainability of the EBI [51, 56, 63, 64, 66, 69, 77]. Furthermore, participants perceived that EBI-related resources built into Electronic Health Record systems and existing structures acted as a consistent reminder for staff to continue the EBI as the standard of care and improved the chances of sustaining lessons learned [69, 77]. One study reported that hiring a designated facilitator was felt to be a key strategy to “ maintaining EBI ‘visibility’, reducing anxiety among nurses, and increasing their confidence regarding the delivery of the EBI” [55] (pg.70). Despite these insights, the majority of included studies lacked specific details on how the KT strategies were used to facilitate the sustainability of the EBI.

Many studies (n = 11) did not clearly report whether they used different or the same KT strategies between EBI implementation and EBI sustainability [51, 55, 56, 58, 60, 63, 65, 66, 70, 72, 73]. However, some studies (n = 7) reported KT strategies that were adapted from the initial implementation period and used to support the sustainability of the EBI (Table 6). For example, one study changed the frequency of their audit cycles, as outcomes were maintained, audits decreased in frequency from weekly to monthly, then quarterly [71]. Nkoy et al. report adapting their initial KT strategies to fit local needs and integrate them into the workflow [53], and Santos et al. used a sustainability and spread framework and KT strategies underpinned by this framework, adapting strategies such as training to continue over time [62]. Schnipper and colleagues refined their EBI and adapted their KT strategies for the scale and spread of an EBI. These changes were based on the results of a mixed-methods evaluation of the EBI post-implementation [57]. Sving et al. adapted their KT strategy of an external facilitator from the implementation to sustainability periods. After 2 years, the role of the external facilitator changed, whereby the facilitator provided support when requested from the unit. This study continued with quality improvement measures every month, a key strategy for the sustainability of the EBI [59]. Of the 25 included studies, only one study used a combination of adapted KT strategies from implementation and new KT sustainability strategies [67]. In this study, MacDonald et al. used the Dynamic Sustainability Framework (DSF) to adapt implementation strategies to sustainability strategies [67]. Four studies [61, 68, 69, 77] reported that they used the same KT strategies in the EBI implementation and sustainability periods, and one of these studies [68] stated that they demonstrated the sustainability of the EBI 5 years post-implementation with the continuation of KT strategies (audit and feedback, local champion). Kingsnorth et al.’s study reported planning for and considering sustainability from the beginning, using multidimensional KT strategies throughout, which included health electronic record revisions, audit and feedback built into the system, mentoring, and education [69]. Only two studies reported using a brand-new KT strategy specifically for EBI sustainability [75, 76]. Of these, one study introduced rapid improvement cycles as a strategy for the sustainability of the EBI, coined as ‘continuous improvement’ [75]. This phase occurred over a 2-year period, commencing immediately after the implementation phase [75]. The other study viewed EBI sustainability as dynamic and introduced new KT strategies based on EBI outcome results over a 5-year period [76].

Reported outcomes

Few studies reported on KT strategy outcomes. Five papers reported on the acceptability of 10 KT strategies used [55, 59, 68, 71, 74], 5 papers reported on the adoption of the KT strategies used [58, 60, 62, 69, 71], and 4 papers reported on the sustainability of 12 KT strategies used [51, 55, 67, 77]. For example, Lai et al. reported that the EBI champion role was readily accepted within the culture that exists in the clinical unit. Three of the five papers that reported on the adoption of a KT strategy were on education and training. For example, Willis et al. reported that the adoption of training as a KT strategy for EBI sustainability was a challenge due to inconsistent refresher training and poor coordination across the included clinical units [58]. Similarly, Santos et al. [65] reported poor adoption of training as a KT strategy for the sustainability of their selected EBI, noting scheduling difficulties. The four papers that reported on the sustainability of KT strategies used, focused on a variety of strategies. For example, Jaladanki [77] et al reported on the sustainability of five KT strategies (EBI champion, quality monitoring, EHR revision, ongoing reminders, and EBI multidisciplinary team), and MacDonald [67] et al, reported on four KT strategies (EBI champion, program facilitator, education, and leadership support). Education was one of the most reported KT strategies in relation to sustainability. For example, Mc Connell et al. [62] reported that the withdrawal of a dedicated facilitator meant that education was delivered informally to new staff by other staff members which led to frustration for staff who felt that formal education was key to successful implementation and sustainability.

The most reported sustainability outcome was the continuation of EBI activities or components (n = 24). The other most reported sustainability outcomes of the EBI were the continuation of benefits for staff and patients (n = 22). For example, Nkoy et al. [74] reported that they observed sustained reductions in asthma readmissions (P = .026) and length of stay (P = .001), a trend reduced costs (P = .094), and no change in hospital resource use, ICU transfers, or deaths. Another commonly reported sustainability outcome was the maintenance of new policies and procedures created because of the EBI (n = 15). For example, Becker et al. [57] reported that their EBI was declared an expected practice by nursing shared governance, supported by the nurse executive, and incorporated into the nursing strategic plan. Rutman et al. [76] reported on the maintenance of procedures for the management of acute gastroenteritis for children presenting to the ED over a 10-year period following the implementation of a clinical pathway using staff involvement, education, and reminders. Table 7 details the reported sustainability outcomes of the EBIs from the included studies.

Discussion

The implementation of EBIs to improve healthcare does not always result in their long-term use or continued benefit for patients or health systems [33]. This gap illustrates the need to examine EBI sustainability as a separate phenomenon [34]. There has been a growing evidence base on factors that influence sustainability [78,79,80] and theoretical approaches to guide the sustainability of EBIs across various healthcare settings [48, 81]. More recently, there has been research conducted on KT strategies for sustaining public health EBIs [29]. However, there is no consolidated evidence on what and how KT strategies are used to support the ongoing use of EBIs across different institutional healthcare settings. This scoping review aimed to address this gap by synthesizing 25 studies reporting on KT strategies used to support the long-term sustainability of EBIs in healthcare institutional settings.

What KT strategies are used to facilitate EBI sustainability

We identified training and education (n = 38) and the development of stakeholder interrelationships (n = 33) as the most reported ERIC KT strategy clusters employed to promote the sustainability of EBIs in our review. This finding is consistent with previous reviews of KT strategies for the implementation of guidelines and EBIs, as well as reviews on the sustainability of KT strategies in healthcare decision-making and public health settings [29, 31]. Future research should consider how education and training KT strategies, such as outreach visits, learning collaboratives, and presentations should be adapted to meet the evolving knowledge needs of the target audience from implementation to sustainability of an EBI.

Developing stakeholder relationships was the second most reported ERIC KT strategy cluster, which includes the use of opinion leaders, EBI champions, and multidisciplinary teams. This finding speaks to the relational nature of EBI implementation and sustainability [48]. Similarly, a previous review on EBI sustainability found that stakeholder participation was a determinant in 79% of theoretical approaches used for the sustainability efforts of EBIs across healthcare settings [48]. A recent study on factors influencing the sustainability and scale-up of a primary healthcare EBI also found that having a leader-champion, facilitation by local facilitators and researchers, and organizational and leadership support as strategies that facilitated sustainability [78].

How are KT strategies used to sustain EBI?

Anticipating that knowledge needs may change over time, as the target audience becomes more familiar with the EBI, we believed that it was important to examine whether: (i) the same KT strategies were used for implementation and sustainability; (ii) new KT strategies were introduced for sustainability; or, (iii) adaptations were made to the KT strategies to support sustainability of the EBI. Our findings showed that 44% (n = 11/25) of studies did not report whether they used different or the same KT strategies between EBI implementation and sustainability. Furthermore, 28% (n = 7/25) of the included studies adopted a KT strategy used to support EBI sustainability [82]. Adaptation may mean changes to the design or delivery of the KT strategy during implementation and sustainability efforts [83, 84]. The papers included in our review provide valuable details on what and how KT strategies are used to support the sustainability of EBIs in healthcare institutions. Future studies should provide the description needed to understand how the KT strategies are adapted or not from implementation to sustainability efforts.

Reported outcomes

Overall, from the included studies it was difficult to synthesize what KT strategies were most acceptable, feasible, appropriate, or adoptable for EBI sustainability across institutional healthcare settings. The studies that reported on KT strategy outcomes primarily focused on the acceptability and adoption of the KT strategies used. This is consistent with a recent review of implementation outcomes, which found that 52% of included studies examined acceptability, while penetration, sustainability, and cost were examined less frequently [85]. We echo Proctor et al.’s recommendations for a more objective measurement of KT strategy (implementation) outcomes to fully understand how KT strategies are being used to facilitate the sustainability of EBIs across different healthcare contexts [38].

Most included studies evaluated EBI sustainability outcomes related to the continuation of EBI activities and the continuation of benefits for staff and patients. This is like a review by Flynn et al. which found that 70% of their included studies evaluated continued benefits for patients, staff, and stakeholders and that the most frequently reported sustained benefits were improved health outcomes and improved quality of care [82]. Similar to our review, Flynn et al. also found that one of the least reported EBI sustainability outcomes was gaining further funds to continue the EBI and to maintain improvements [82]. Our findings also echo a review by Lennox et al., which found that only 21% of included studies reported any information on EBI sustainability outcomes in healthcare [79].

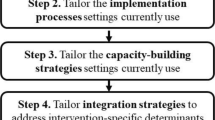

Implications

First, this scoping review mapped what and how KT strategies are used for the sustainability of EBIs across institutional healthcare settings. Our review findings provide insights for health system leaders, decision-makers, and researchers about KT strategies being used to facilitate the sustainability of EBIs in institutional healthcare settings. Our findings suggest that health system leaders and decision-makers may want to pay special attention to the people involved, including champions and staff support, training and education, and evaluative and iterative strategies when aiming to sustain an EBI.

Second, this scoping review identified research gaps in the existing literature. To advance understanding of how to employ KT strategies for EBI sustainability, we recommend clearly reporting the dose, frequency, adaptations, fidelity, and cost of KT strategies. EBI sustainability literature has made important strides to enhance our understanding of KT strategies for sustainability, including the recent adaption, refinement, and extension of the ERIC taxonomy to include an explicit focus on sustainment [86]. We recommend using this revised taxonomy in future EBI implementation and sustainability efforts and include specific details such as KT strategy description, dose, frequency, and adaptations when first used to implement the EBI through to its use for the sustainability of the EBI. The use of reporting guidelines, such as the Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI), AIMD Framework [47], and the TIDieR Checklist [84], but with clear reporting on if/how KT strategies are adapted for the sustainability of EBIs, could strengthen this evidence base [87].

Third, like Penno et al. [88], our work suggests that sustainability is a dynamic process with implementation and sustainability better conceptualized as a continuum rather than two discrete time periods or phases. This continuum conceptualization supports the consideration of how KT strategies for EBI sustainability over time differ from EBI implementation and/or potentially overlap. This continuum also supports the idea that over time the target audience may become more familiar with the EBI and as a result, KT strategies may need to be adapted.

Fourth, building on this scoping review, future research is needed that compares KT strategies in sustainability research, to determine how aspects of the EBI, potential adopters, and other context features interact with KT strategies to influence initial and ongoing EBI use. This will help determine which strategies are most pertinent to EBI sustainability. As such, efforts on KT ‘sustainability’ strategies are needed to add to this evidence base including experimental study designs to test different types of KT strategies, as well as other non-experimental designs to understand how, why, and under what contexts certain KT strategies work or not for EBI sustainability. We recommend the use of realist approaches to unpack the causal relationships between contexts (e.g., culture for change), the EBI (e.g., a clinical pathway), mechanisms of change (e.g., KT strategy) that lead to sustainability outcomes (e.g., continuation of benefits for patients). Such evidence would be highly beneficial to researchers, healthcare leaders, and decision-makers who need guidance on what KT strategy to select to support not only implementation but also EBI sustainability across different healthcare environments.

Strengths and limitations

Findings from this scoping review should be considered with the following limitations in mind. We only included published studies in the English language and peer-reviewed primary studies in this review. We recognize that there is the possibility of relevant articles not being included in our search strategy. This review was descriptive in nature, given its scoping review focus. As such the study reports what strategies are being used but does not describe the effectiveness of the KT strategies. As such, our review findings are limited in their ability to make recommendations on the effectiveness of KT strategies for the sustainability of EBIs across institutional healthcare settings and the relationship between the EBI, KT strategy selected, and subsequent implementation and sustainability outcomes.

This review used a systematic approach to our search strategy and screening with multiple databases and employed theoretical frameworks/taxonomies/classification systems to understand how the findings align with other implementation and sustainability literature. Our review highlights that the implementation and sustainability of EBIs in healthcare is a continuum and the need for a better understanding of the potential extent of KT strategy adaptation from the initial implementation of an EBI to sustainability.

Conclusion

It is only with the sustainability of EBIs that patient, provider, and health system outcomes will be realized, hence the imperative to better understand (how and to what extent) KT strategies support the ongoing use of EBIs. Our review has emphasized areas that require further research (e.g., KT strategy adaptation for EBI sustainability) and the need for reporting on KT strategies for the sustainability of EBIs in healthcare. Advancing our understanding in this area would facilitate better design, selection, tailored, and adapted use of KT strategies for EBI sustainability, thereby contributing to improved patient, provider, and health system outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- KT:

-

Knowledge translation

- EBIs:

-

Evidence-based interventions

References

Rabin BA, Brownson RC. Developing the terminology for dissemination and implementation research. In: Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice. Oxford University Press; 2012. p. 23–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199751877.003.0002.

Braithwaite J, Glasziou P, Westbrook J. The three numbers you need to know about healthcare: the 60-30-10 Challenge. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01563-4.

Squires JE, Cho-Young D, Aloisio LD, et al. Inappropriate use of clinical practices in Canada: a systematic review. Can Med Assoc J. 2022;194(8):E279–96. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.211416.

Wiltsey Stirman S, Kimberly J, Cook N, Calloway A, Castro F, Charns M. The sustainability of new programs and innovations: a review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-17.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research. CIHR About Us - Knowledge Translation. Accessed August 24, 2023. https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29418.html.

Eccles MP, Mittman BS. Welcome to Implementation Science. Implement Sci. 2006;1(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-1-1.

Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, Squires JE. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-50.

Powell BJ, Fernandez ME, Williams NJ, et al. Enhancing the Impact of Implementation Strategies in Healthcare: A Research Agenda. Front. Public Health. 2019;7(JAN):431063. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00003.

Armstrong R, Waters E, Dobbins M, et al. Knowledge translation strategies to improve the use of evidence in public health decision making in local government: intervention design and implementation plan. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):121. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-121.

Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Matthieu MM, et al. Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):109. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0295-0.

Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1.

Stetler CB, Legro MW, Rycroft-Malone J, et al. Role of “external facilitation” in implementation of research findings: a qualitative evaluation of facilitation experiences in the Veterans Health Administration. Implement Sci. 2006;1(1):23. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-1-23.

O’Brien M, Oxman A, Haynes R, Davis D, Freemantle N, Harvey E. Local opinion leaders: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. In: O’Brien MA, editor. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 1999. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000125.

Colquhoun HL, Carroll K, Eva KW, et al. Informing the research agenda for optimizing audit and feedback interventions: results of a prioritization exercise. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021;21(1):20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-020-01195-5.

Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2012(6) https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub3.

O’Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000409.pub2.

Yamada J, Shorkey A, Barwick M, Widger K, Stevens BJ. The effectiveness of toolkits as knowledge translation strategies for integrating evidence into clinical care: A systematic review. BMJ Open. 2015;5(4):e006808. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJOPEN-2014-006808/-/DC1.

Abdullah G, Rossy D, Ploeg J, et al. Measuring the effectiveness of mentoring as a knowledge translation intervention for implementing empirical evidence: a systematic review. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2014;11(5):284–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12060.

Squires JE, Sullivan K, Eccles MP, Worswick J, Grimshaw JM. Are multifaceted interventions more effective than single-component interventions in changing health-care professionals’ behaviours? An overview of systematic reviews. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):152. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-014-0152-6.

Thompson C, Stapley S. Do educational interventions improve nurses’ clinical decision making and judgement? A systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(7):881–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJNURSTU.2010.12.005.

Thompson DS, Estabrooks CA, Scott-Findlay S, Moore K, Wallin L. Interventions aimed at increasing research use in nursing: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2007;2(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-2-15.

Squires JE, Suh KN, Linklater S, et al. Improving physician hand hygiene compliance using behavioural theories: A study protocol. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-16/TABLES/3.

Sasaki N, Yamaguchi N, Okumura A, et al. Factors affecting the use of clinical practice guidelines by hospital physicians: the interplay of IT infrastructure and physician attitudes. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13012-020-01056-1/TABLES/4.

Menon A, Korner-Bitensky N, Kastner M, McKibbon KA, Straus S. Strategies for rehabilitation professionals to move evidence-based knowledge into practice: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41(13):1024–32. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-0451.

Ospina MB, Taenzer P, Rashiq S, et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness of knowledge translation interventions for chronic noncancer pain management. Pain Res Manag. 2013;18(6):e129–41. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/120784.

Al Zoubi FM, Menon A, Mayo NE, Bussières AE. The effectiveness of interventions designed to increase the uptake of clinical practice guidelines and best practices among musculoskeletal professionals: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):435. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3253-0.

Larocca R, Yost J, Dobbins M, Ciliska D, Butt M. The effectiveness of knowledge translation strategies used in public health: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-751/TABLES/3.

Yost J, Ganann R, Thompson D, et al. The effectiveness of knowledge translation interventions for promoting evidence-informed decision-making among nurses in tertiary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/S13012-015-0286-1.

Hailemariam M, Bustos T, Montgomery B, Barajas R, Evans LB, Drahota A. Evidence-based intervention sustainability strategies: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13012-019-0910-6/TABLES/6.

Shelton RC, Cooper BR, Stirman SW. The sustainability of evidence-based interventions and practices in public health and health care. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:55–76. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-014731.

Tricco AC, Ashoor HM, Cardoso R, et al. Sustainability of knowledge translation interventions in healthcare decision-making: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0421-7.

Veroniki AA, Soobiah C, Nincic V, et al. Efficacy of sustained knowledge translation (KT) interventions in chronic disease management in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of complex interventions. BMC Med. 2023;21(1):269. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-023-02966-9.

Nathan N, Shelton RC, Laur CV, Hailemariam M, Hall A. Editorial: Sustaining the implementation of evidence-based interventions in clinical and community settings. Front Health Serv. 2023;3:1176023. https://doi.org/10.3389/frhs.2023.1176023.

Scheirer MA, Dearing JW. An Agenda for Research on the Sustainability of Public Health Programs. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(11):2059–67. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300193.

Moore JE, Mascarenhas A, Bain J, Straus SE. Developing a comprehensive definition of sustainability. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/S13012-017-0637-1.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK. Dissemination and Implementation Research in HealthTranslating Science to Practice. Oxford University Press; 2012. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199751877.001.0001.

Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):139. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-139.

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Hlth Service Res. 2011;38(2):65–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7.

Shoesmith A, Hall A, Wolfenden L, et al. Barriers and facilitators influencing the sustainment of health behaviour interventions in schools and childcare services: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2021;16(1):62. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-021-01134-y.

Proctor E, Luke D, Calhoun A, et al. Sustainability of evidence-based healthcare: research agenda, methodological advances, and infrastructure support. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0274-5.

The Joanna Briggs Institute. Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews. In: Reviewers’ Manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute. Published online 2015:3-24. https://research.monash.edu/en/publications/methodology-for-jbi-scoping-reviews.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Rethlefsen ML, Kirtley S, Waffenschmidt S, et al. PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01542-z.

Covidence. Covidence - Better systematic review management. Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation. Published 2020. https://www.covidence.org/.

Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Fernández ME, Abadie B, Damschroder LJ. Choosing implementation strategies to address contextual barriers: diversity in recommendations and future directions. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0892-4.

Bragge P, Grimshaw JM, Lokker C, Colquhoun H, AIMD Writing/Working Group. AIMD - a validated, simplified framework of interventions to promote and integrate evidence into health practices, systems, and policies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17(1:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0314-8.

Lennox L, Maher L, Reed J. Navigating the sustainability landscape: a systematic review of sustainability approaches in healthcare. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0707-4.

Tierney A, Haverfield C, McGovern P, Zulman D. Advancing Evidence Synthesis from Effectiveness to Implementation: Integration of Implementation Measures into Evidence Reviews. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(4):1219–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05586-3.

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content. Analysis. 2005;15 https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

Storm-Versloot MN, Knops AM, Ubbink DT, Goossens A, Legemate DA, Vermeulen H. Long-term adherence to a local guideline on postoperative body temperature measurement: mixed methods analysis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(4):841–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01687.x.

Mixon AS, Smith GR, Mallouk M, et al. Design of MARQUIS2: study protocol for a mentored implementation study of an evidence-based toolkit to improve patient safety through medication reconciliation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):659. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4491-5.

Nkoy F, Fassl B, Stone B, et al. Improving pediatric asthma care and outcomes across multiple hospitals. Pediatrics. 2015;136(6):e1602–10. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-0285.

Titler MG, Herr K, Brooks JM, et al. Translating research into practice intervention improves management of acute pain in older hip fracture patients. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(1):264–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00913.x.

McConnell T, O’Halloran P, Donnelly M, Porter S. Factors affecting the successful implementation and sustainability of the Liverpool Care Pathway for dying patients: a realist evaluation. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2015;5(1):70–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000723.

Tamboli M, Leng JC, Hunter OO, et al. Five-year follow-up to assess long-term sustainability of changing clinical practice regarding anesthesia and regional analgesia for lower extremity arthroplasty. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2020;73(5):401–7. https://doi.org/10.4097/kja.19400.

Schnipper JL, Reyes Nieva H, Mallouk M, et al. Effects of a refined evidence-based toolkit and mentored implementation on medication reconciliation at 18 hospitals: results of the MARQUIS2 study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2022;31(4):278–86. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2020-012709.

Willis TS, Yip T, Brown K, Buck S, Mill M. Improved teamwork and implementation of clinical pathways in a congenital heart surgery program. Pediatr Qual Saf. 2019;4(1):126. https://doi.org/10.1097/pq9.0000000000000126.

Sving E, Fredriksson L, Mamhidir AG, Högman M, Gunningberg L. A multifaceted intervention for evidence-based pressure ulcer prevention. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2020;18(4):391–400. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000239.

Stevens BJ, Yamada J, Promislow S, Barwick M, Pinard M, CIHR Team in Children’s Pain. Pain Assessment and Management After a Knowledge Translation Booster Intervention. Pediatrics. 2016;138(4) https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3468.

Shuman CJ, Xie XJ, Herr KA, Titler MG. Sustainability of evidence-based acute pain management practices for hospitalized older adults. West J Nurs Res. 2018;40(12):1749–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945917738781.

Santos P, Joglekar A, Faughnan K, et al. Sustaining and spreading quality improvement: Decreasing intrapartum malpractice risk. J Healthcare Risk Manag. 2019;38(3):42–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhrm.21329.

Rutman L, Klein EJ, Brown JC. Clinical pathway produces sustained improvement in acute gastroenteritis care. Pediatrics. 2017;140(4) https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-4310.

Parand A, Benn J, Burnett S, Pinto A, Vincent C. Strategies for sustaining a quality improvement collaborative and its patient safety gains. Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;24(4):380–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzs030.

Oetgen ME, Martin BD, Gordish-Dressman H, Cronin J, Pestieau SR. Effectiveness and sustainability of a standardized care pathway developed with use of lean process mapping for the treatment of patients undergoing posterior spinal fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg - Am. 2018;100(21):1864–70. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.18.00079.

Moro ML, Morsillo F, Nascetti S, et al. Determinants of success and sustainability of the WHO multimodal hand hygiene promotion campaign, Italy, 2007-2008 and 2014. Euro Surveill. 2017;22(23):30546. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.23.30546.

MacDonald J, Doyle L, Moore JL, Rafferty MR. Sustainment of proactive physical therapy for individuals with early-stage Parkinson’s disease: a quality improvement study over 4 years. Implement Sci Commun. 2021;2(1):111. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-021-00205-x.

Lai B, Gibb C, Pink J, Thomas L. Sustainability of a pharmacist-driven pathway for osteoporosis-related fractures on an orthopaedic unit after a 5-year period. Int J Pharm Practice. 2012;20(2):134–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-7174.2011.00167.x.

Kingsnorth S, Joachimides N, Krog K, Davies B, Higuchi KS. Optimal pain assessment in pediatric rehabilitation: implementation of a nursing guideline. Pain Manag Nursing. 2015;16(6):871–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2015.07.009.

Comino-Sanz IM, Sánchez-Pablo C, Albornos-Muñoz L, et al. Falls prevention strategies for patients over 65 years in a neurology ward: a best practice implementation project. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2018;16(7):1582–9. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003628.

Becker S, Hagle M, Amrhein A, et al. Implementing and sustaining bedside shift report for quality patient-centered care. J Nurs Care Qual. 2021;36(2):125–31. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000509.

Barbieri E, De Luca M, Minute M, et al. Impact and sustainability of antibiotic stewardship in pediatric emergency departments: why persistence is the key to success. Antibiotics. 2020;9(12):867. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics9120867.

Andersson V, Bergman S, Henoch I, et al. Pain and pain management in hospitalized patients before and after an intervention. Scand J Pain. 2017;15(1):22–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2016.11.006.

Allen E, Williams A, Jennings D, et al. Revisiting the pain resource nurse role in sustaining evidence-based practice changes for pain assessment and management. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2018;15(5):368–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12318.

Algaze CA, Shin AY, Nather C, et al. Applying Lessons from an Inaugural Clinical Pathway to Establish a Clinical Effectiveness Program. Pediatr Qual Saf. 2018;3(6):115. https://doi.org/10.1097/pq9.0000000000000115.

Erdei C, McAvoy LL, Gupta M, Pereira S, McGowan EC. Is zero central line-associated bloodstream infection rate sustainable? A 5-year perspective. Pediatrics. 2015;135(6):e1485–93. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2523.

Jaladanki S, Schechter SB, Genies MC, et al. Strategies for sustaining high-quality pediatric asthma care in community hospitals. Health Serv Res. 2022;57(1):125–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13870.

Morgan D, Kosteniuk J, O’Connell ME, et al. Factors influencing sustainability and scale-up of rural primary healthcare memory clinics: perspectives of clinic team members. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):148. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07550-0.

Lennox L, Linwood-Amor A, Maher L, Reed J. Making change last? Exploring the value of sustainability approaches in healthcare: a scoping review. Health Res Policy Syst. 2020;18(1):120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00601-0.

Braithwaite J, Ludlow K, Testa L, et al. Built to last? The sustainability of healthcare system improvements, programmes and interventions: a systematic integrative review. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e036453. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJOPEN-2019-036453.

Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-117.

Flynn R, Stevens B, Bains A, Kennedy M, Scott SD. Identifying existing approaches used to evaluate the sustainability of evidence-based interventions in healthcare: an integrative review. Syst Rev. 2022;11(1):221. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-022-02093-1.

Baumann AA, Cabassa LJ, Stirman SW. Adaptation in dissemination and implementation science, vol. 1. Oxford University Press; 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190683214.003.0017.

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348(mar07 3):g1687-g1687. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1687.

Proctor EK, Bunger AC, Lengnick-Hall R, et al. Ten years of implementation outcomes research: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2023;18(1):31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-023-01286-z.

Nathan N, Powell BJ, Shelton RC, et al. Do the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) strategies adequately address sustainment? Front Health Service. 2022;2:905909. https://doi.org/10.3389/frhs.2022.905909.

Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, et al. Standards for reporting implementation studies (StaRI) statement. BMJ. 2017;356:i6795. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i6795.

Nadalin Penno L, Davies B, Graham ID, et al. Identifying relevant concepts and factors for the sustainability of evidence-based practices within acute care contexts: a systematic review and theory analysis of selected sustainability frameworks. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0952-9.

Acknowledgements

RF acknowledges the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, the Women and Children’s Health Research Institute, and the Faculty of Nursing, University of Alberta, for their support during the time of this research. CC acknowledges the Faculty of Health Research Establishment grant for support of this review. SDS is funded through a Canada Research Chair and a Distinguished Researcher Award from the Stollery Science Lab program at the Women and Children’s Health Research Institute. IDG is a CIHR Foundation Grant recipient (DFN# 132237).

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RF and CC developed the research question. RF, CC, SDS, and IG designed the study. LD, JAR, and JL coded the data, supervised by RF and CC. SDS and IG were advised during data extraction and synthesis. JS managed the project team and review processes. All authors collaborated on writing the manuscript, and all authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist.

Additional file 2.

Search strategies by database.

Additional file 3.

The reported aims, ingredients, mechanism, and delivery of the KT strategies.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Flynn, R., Cassidy, C., Dobson, L. et al. Knowledge translation strategies to support the sustainability of evidence-based interventions in healthcare: a scoping review. Implementation Sci 18, 69 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-023-01320-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-023-01320-0