Abstract

Background

The objective of this systematic review was to summarize and evaluate evidence about the effectiveness of knowledge translation (KT) interventions to improve the uptake and application of clinical practice guidelines and best practices for a wide range of musculoskeletal (MSK) disorders and health care professionals.

Methods

A search for relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in English was conducted in MEDLINE (Ovid interface), EMBASE, CINAHL, and CENTRAL (Cochrane library). Two independent reviewers selected studies, assessed risk of bias, and extracted data. All MSK disorders were included except MSK injuries, fractures, trauma, or inflammatory disorders.

Results

A total of 7904 citations yielded 11 eligible RCTs. The targeted MSK disorders included: low back pain (n = 5), neck pain (n = 2), whiplash (1), spinal disorders (n = 1), and osteoarthritis of the hip and knee (n = 2). Studies primarily involved physiotherapists, chiropractors, and a mix of physiotherapists, chiropractors and osteopaths. Results were reported using effect sizes (Cohen’s d). Interactive educational meetings were the most commonly used KT strategy. For professional outcomes, 3 studies using single-component interventions had a small effect (d ranges from 0.14 to 0.28) and 7 studies used multifaceted interventions (3 were effective (d ranges from 0.824 to 2.27). For patient outcomes, 4 studies were ineffective (d ranges from 0.06 to 0.31). The majority of the included RCTs had moderate-to-high risk of bias. About half of the studies used theory-based interventions, but the elements of the interventions and theoretical frameworks were often poorly described. Furthermore, there were no comparable outcome measures to evaluate the impact of the interventions on a similar scale.

Conclusions

The findings suggested that multifaceted educational KT interventions appear to be effective for improving professional outcomes, although effects were inconsistent. The KT strategies were generally not effective on patient outcomes. In general, studies were of low quality, interventions were poorly described, and only half had theoretical underpinning. Researchers are encouraged to use validated professional and patient outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Musculoskeletal (MSK) disorders are the second leading cause of disability globally and account for 21.3% of the total years lived with disability [1, 2]. About half (49.6%) of the total MSK disability stems from low back pain (LBP), followed by neck pain (20.1%), non-spinal MSK disorders (17.3%), osteoarthritis (10.5%), rheumatoid arthritis (2.3%), and gout (0.1%) [3]. Among people with MSK disorders, pain is the most common reason to consult health care providers in primary care [4,5,6,7]. In addition to the large impact on individuals, MSK conditions are associated with a massive social and economic burden to society [8,9,10,11,12].

Despite available evidence-based guidelines on the management of patients with MSK disorders [13,14,15], numerous professional barriers (e.g., lack of awareness, skills, self-capacity and motivation) impede the routine application of guideline recommendations in clinical practice [16, 17]. The field of knowledge translation (KT) has produced a plethora of tools and methods to address these barriers and enhance the uptake of guidelines by clinicians. The field of KT is focused on closing the gap between what is known to work best and what is routinely done in practice [18]. The closure of this gap can be achieved through developing and implementing KT interventions [19].

Most systematic reviews on the effectiveness of KT interventions to increase the uptake of clinical practice guidelines or best practices have targeted physicians [20,21,22,23,24] and nurses [25,26,27,28]. More recently, five systematic reviews focused on allied health professionals’ uptake of guidelines [19, 29,30,31,32]. Two of the reviews [29, 30] concluded that multifaceted KT interventions among physiotherapists can improve professional outcomes. However, one review failed to show improvement of patient outcomes [30]. In 2012, Scott et al. [19] conducted a review targeting five allied health professions (dietetics, occupational therapy, pharmacy, physiotherapy, and speech-language pathology). The search was later updated by Jones et al. (2015) [31] targeting three allied health professions (occupational therapists, physical therapists, and speech-language pathologists). These two reviews suggested that generally the studies were of poor methodological quality which precluded any decision about the effective KT intervention. A fifth review [32] evaluating the effectiveness of KT interventions to change clinical practice of physiotherapists managing common MSK disorders found equivocal effects for professional and patient outcomes.

To date, no single review has targeted other MSK professionals working in orthopedics, rheumatology, manual therapy, chiropractic, osteopathy, athletic therapy, sports medicine, acupuncture, among other areas. Thus, the goal of this review was to summarize and evaluate evidence about the effectiveness of KT interventions to improve the uptake and application of clinical practice guidelines and best practices for MSK disorders among MSK professionals.

This review addressed the following question: among MSK professionals, to what extent do KT interventions impact on (i) uptake of clinical practice guidelines or best practices for MSK disorders, and (ii) patient outcomes? For the purpose of this review, MSK professionals are health care providers whose nature and scope of practice primarily involves managing MSK disorders.

Methods

This review followed the recommendations of Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [33].

Search strategy

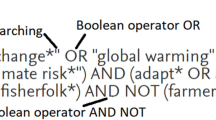

The following electronic databases were searched from inception to August 10th, 2016: MEDLINE (Ovid interface), EMBASE, CINAHL, and CENTRAL (Cochrane library). The search strategy (Additional file 1) was developed in conjunction with an expert health sciences librarian at McGill University. The search strategy was built using four key terms, MSK disorders, MSK health care professionals, KT interventions, and a filter for RCTs. The search strategy was developed in MEDLINE and translated into the other databases using the appropriate MESH terms as applicable. A validated search strategy with a filter for KT interventions [34] was used with some modifications (e.g. removing keywords such as nurse, pharmacist, and general practitioner) to fit our review question.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Control group studies

Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included in this review as they are considered the gold standard for examining the impact (or causal relationship) of an intervention and providing unbiased estimates of the intervention effects for the outcomes of interest [35, 36]. Furthermore, trials published in English were eligible for this review; it was deemed that this restriction is unlikely to bias the findings since most RCTs are published in English [37,38,39,40,41]. Non-RCTs, uncontrolled studies, and observational studies were excluded. Protocols, commentaries, conference proceedings, and reviews were also excluded.

Types of participants

MSK professionals

For the purpose of this review, MSK professionals included: physiotherapists, occupational therapists, manual therapists, chiropractors, athletic therapists, sport therapists, sport physicians, massage therapists, osteopaths, osteopathic physicians, exercise physiologists, kinesiologists, physiatrists, orthopedists, podiatrists, orthopedic surgeons, and acupuncturists. Studies targeting students were excluded.

Patients

All types of MSK conditions were included, except patients with MSK injuries, fractures, trauma, or inflammatory disorders (such as rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis). Furthermore, pregnant or pediatric-based MSK disorders were excluded.

Types of interventions

Studies that primarily aimed to evaluate all types of KT interventions (professional, financial, organizational, and regulatory) designed to improve the uptake and use of clinical practice guidelines or best evidence targeting MSK professionals working with MSK patients, were included. Studies had to mention the source and content of the evidence that had been transferred with the appropriate references. Studies with patient-directed interventions without the involvement of MSK professionals in the intervention were excluded. Pharmacological-based or surgical-based studies were excluded as well.

Types of outcome measures

We included studies with any primary outcome relevant to the objective of this review that assessed change, whether quantitatively or qualitatively, at the professional/process level (such as change in practice or behavior, knowledge, skills, self-efficacy) or patient level (such as change in knowledge, health status, pain, disability). Outcomes relevant to economic level were excluded. Table 1 provides a summary of the inclusion/exclusion criteria for this review.

Study selection and data abstraction

All citations retrieved from literature searches were imported into EndNote and duplicates were removed. After a calibration exercise, the selection criteria were applied independently by two reviewers (FZ, AM) on all citations’ titles and abstracts. These criteria were then applied to the full text of eligible studies. One reviewer (FZ) undertook the data extraction of the included studies using a modified EPOC Data Collection Checklist [42], and the another reviewer reviewed the extracted data. At all steps, disagreements were resolved by discussion between the reviewers; if no agreement was reached, a third reviewer (AB) was asked to resolve differences. Articles deemed unsuitable for inclusion are listed in the additional file 2, along with the reason for their exclusion.

Quality assessment

Two reviewers independently assessed the risk of bias of the included studies using the criteria developed by the Cochrane Handbook for Risk of Bias Assessment (version 5.1.0) [33], which included random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other potential sources of bias. Studies deemed as poor quality with a high risk for bias were included in this analysis. RevMan 5.3 software [43] was used to provide a graphical representation for risk of bias.

Data analysis

For both professionals and patients, studies were categorized according to their outcomes. A meta-analysis was not conducted due to the substantial heterogeneity (divergence) in the methodological quality, type of KT interventions, outcomes measures, and the type of MSK disorder under consideration across studies. Therefore, the findings were synthesized in a narrative manner. Effect sizes were calculated for both professional and patient outcomes using the differences in means between intervention and control groups over time, divided by pooled standard deviation [44]. The common rule of thumb was used for interpreting effect sizes (Cohen’s d) in the following manner: small (d = 0.2), medium (d = 0.5), and large (d = 0.8) [45].

Results

Search results and characteristics of the included studies

A total of 7904 citations were identified by the search strategy, leaving 3356 citations after duplicate removal. After screening of titles and abstracts, 172 studies were assigned for full-text reading; of which only 13 met the eligibility criteria. Of these, 2 references were multiple publications; thus, analysis was conducted on 11 unique studies (six individual RCTs [46,47,48,49,50,51] and five cluster RCTs [52,53,54,55,56]) reported in 13 publications (see Fig. 1 for the Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram). Additional files 3 and 4 report the characteristics of the included studies for professional and patient outcomes respectively.

The distribution of the included studies by country of origin was as follows: the Netherlands (n = 4) [49, 50, 52, 55], UK (n = 2) [48, 53], Australia (n = 2) [51, 54], USA (n = 1) [46], Switzerland (n = 1) [47], and Ireland (n = 1) [56]. Targeted MSK disorders included five studies on LBP [48, 52, 53, 55, 56], two studies on hip and knee osteoarthritis (OA) [49, 50], one on whiplash [54], two on neck pain [46, 51], and one on spinal disorders [47]. Two of the included studies tested KT interventions delivered in primary care settings [52, 53], two in private clinics [46, 54], two in both primary and secondary settings [49, 50], one in a conference for chiropractors [47]; one in primary care and occupational settings [48], one in communities of practice of physical therapists [55], and one in hospital outpatient physiotherapy clinics [56]. One study did not report their setting [51].

Risk of bias

Figure 2 provides a graphical representation of the reviewers’ judgments on each ‘risk of bias’ item, which is presented as overall percentages across all included studies to facilitate comparison. Fig. 3 presents the reviewers’ judgments on all ‘risk of bias’ items for each included study. Over 75% of the included studies addressed random sequence generation (selection bias) and allocation concealment (selection bias); almost half of them carried out blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) and blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias). One study was deemed to have a low risk of bias [46], six a moderate risk of bias [47,48,49, 52, 54,55,56], and four a high risk of bias [50, 51, 53]. Table 2 outlines the assessment of methodological quality (low, moderate, or high) of the included studies based on the EPOC standard criteria for reviews for RCTs.

Types of professional and patient outcomes

Ten studies [47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56] assessed MSK professional-related primary outcomes, including: knowledge about the guidelines [54, 55], self-confidence [51], adherence to guidelines [49, 50, 52], change in clinical practice (advice to patients [48, 53], and appropriate use of the diagnostic imaging [47]), and clinician-patient communication [56]. Each outcome was measured using a different scale. Four studies assessed patient-related outcomes, including patients’ function (disability) [46, 51, 52, 54] and pain [46, 52].

Impact of KT interventions on professional and patient outcomes

Additional files 3 and 4 also report on the effectiveness of KT interventions on professional and patient outcomes respectively. Results were reported using effect sizes (Cohen’s d) and the reported P- values based on the original authors’ measurement units because there were no comparable outcome measures. Graphical representation of publication bias using a funnel plot was also not possible for this same reason.

Impact of KT interventions on professional outcomes

All studies included in this review involved KT interventions targeting professional outcomes, except one that focused on patient outcomes only [46]. Additional file 5 presents the elements of the KT interventions and use of theoretical frameworks, models or theories, while Table 3 presents the KT intervention types and their components.

Effects of single and multifaceted interventions on professional outcomes

Single-component KT interventions

In total three studies assessed the impact of single-component KT interventions on professional outcomes. Two of these tested a single-component KT intervention against no intervention [48, 50], while only one study compared a single-component KT intervention against another KT intervention [49]. Interactive educational meetings were found to have a small effect on enhancing professional adherence to clinical practice guidelines for hip and knee OA for physiotherapists, as compared to those who received no intervention (d = 0.23 (0.01–0.45), P < 0.05) [50] or a conventional educational meeting (d = 0.28 (0.02–0.53), P < 0.05) [49] at 3-month follow-up. Distribution of educational materials (LBP management guideline by postal mail) against no intervention also had a small effect on changing practice behavior (advice about physical activity level: d = 0.14 (0.05–0.23), P < 0.05; work: d = 0.16 (0.07–0.25), P < 0.05) for physiotherapists, chiropractors, and osteopaths at six months [48].

Multifaceted KT interventions

In total seven studies assessed the effectiveness of multifaceted KT interventions on professional outcomes. Three of these assessed multifaceted KT interventions were against no intervention [47, 53, 56] and reported mixed results. The first study showed that communication skills training from educational meetings and reminders for physiotherapists to support patients’ psychological needs were found to be more effective than the control for managing chronic LBP at 16.7 ± 6.9 weeks (d = 2.27 (1.24–3.29), P < 0.05) [56]. A second study reported on the effect of educational meetings on enhancing the appropriate use of diagnostic imaging for spinal disorders for chiropractors [47]. While the subgroup with access to a reminder at midpoint performed significantly better than another subgroup (F = 4.486; df = 1, 30; P = 0.043), the overall scores for the pretest and the final test did not significantly differ at 10 weeks (d = 0.05 (− 0.26–0.36), P > 0.05). A third study combined interactive educational meetings with local opinion leaders against no intervention and was also found to be ineffective in changing physiotherapists’ clinical practice regarding the use of best evidence on ‘Psychosocial Yellow Flags’ for non-specific LBP patients at 6 months [53] (see Additional file 3 for the summary effect sizes).

The other four studies compared multifaceted KT interventions against other single or multifaceted interventions [51, 52, 54, 55] and reported positive findings. A combination of interactive educational meetings, educational outreach visits, distribution of educational materials, and local opinion leaders showed a significantly superior effect (d = 2.151 (1.2–3.1), P < 0.05) compared with the distribution of educational materials (guideline by postal mail), in changing physiotherapists’ knowledge about the whiplash guideline at 12 months [54]. Implementation of the Dutch physical therapy guideline for LBP found that educational meetings, distribution of educational materials, and peer-assessment compared to educational meetings and distribution of educational materials significantly improved knowledge and guideline-consistent clinical reasoning with a large effect (d = 0.824 (− 0.23–1.88), P < 0.05) at 6 months [55]. Interactive educational meetings and distribution of educational materials also had a significant, but small effect (d = 0.4 (0.08–0.71), P < 0.05) compared to distribution of educational materials (guideline by postal mail) in improving physiotherapists’ adherence to a non-specific LBP guideline at 1 month [52]. One other study found that a traditional continuing professional development educational meeting and a reminder compared to a traditional educational meeting alone had a small, non-significant effect in improving physiotherapists’ practice behaviour or confidence in using multimodal interventions (advice, education, exercise and manual therapy) for neck pain patients at 2 months [51].

Together, these findings suggest that for professional outcomes, single-component KT interventions are more effective than no intervention, and multifaceted interventions are more effective than single-component interventions.

Impact of KT interventions on patient outcomes

Four studies evaluated the impact of the KT interventions on patient outcomes [46, 51, 52, 54].

Single-component KT interventions

No study assessed the impact of a single-component KT intervention on patient outcomes.

Multifaceted KT interventions

Four studies assessed the effectiveness of multifaceted KT interventions on patient outcomes. One study favoured a multifaceted intervention (combination of educational meetings and an educational outreach visit) over no intervention for reducing neck disability at 12 months (d = 0.27 (0.09–0.45), P < 0.05), but not level of neck pain (d = 0.16 (− 0.01–0.33), P > 0.05) [46]. Three other studies investigated the effectiveness of multifaceted interventions against other types of interventions. Interactive educational meetings were predominantly shared with all of these studies along with other components. A combination of distribution of educational materials about a non-specific LBP guideline and interactive educational meetings against distribution of educational materials alone had no effect on improving disability (d = 0.28 (0.10–0.45), P > 0.05) or pain at 6, 12, 26, and 52 weeks (d = 0.31 (0.13–0.49), P > 0.05) [52]. A combination of interactive educational meetings, educational outreach visits, local opinion leaders, and distribution of educational materials (a guideline on the management of acute whiplash) was not superior to the distribution of educational materials alone for improving disability at 12 months (d = 0.06 (− 0.39–0.51), P > 0.05) [54]. Lastly, a combination of educational meetings and reminders was ineffective for improving disability for neck pain patients at 4 months (d = 0.11 (− 0.25–0.48), P > 0.05) [51].

Overall, included studies suggest that multifaceted interventions delivered to professionals did not improve patient outcomes.

Discussion

This review summarized the evidence from eleven studies that investigated the impact of various KT interventions on MSK professional and patient outcomes for MSK disorders. Nine studies involved physiotherapists, one chiropractors, and one a mixed of physiotherapists, chiropractors, and osteopaths. The targeted behaviors were the general management of MSK disorders (nine studies), diagnostic spine imaging, and professional-patient communication. Five studies were on LBP, two on neck pain and whiplash, one on spinal disorders, and two others on OA of the hip and knee.

Although this review included only RCTs, the majority of the included studies were considered to have moderate-to-high risk of bias. This is consistent with the findings of similar reviews [19, 29, 57, 58]. The assessment of the risk of bias was challenging due to poor or incomplete reporting of methodological characteristics in several studies. The small number of eligible studies prevented us from comparing outcome measures across studies considering this review included multiple KT strategies, professions, targeted behaviours and MSK conditions.

Educational meetings were used across most the included studies. Three studies suggested that single-component interventions had a small, albeit significant effect for improving professional outcomes whether compared to no intervention [48, 50] or another intervention [50].

The majority of the included studies (8/11) used multifaceted KT interventions. This is consistent with other reviews in similar areas [19, 58], possibly because the use of multifaceted interventions was previously encouraged [59]. Seven studies assessed the effectiveness of multifaceted interventions on professional outcomes. Three of these were compared to no interventions showing mixed effects for educational meetings and reminders [47, 56], and no effect for interactive educational meetings delivered by local opinion leaders [53]. Four other studies were compared to single-type interventions, with three showing favorable results [52, 54, 55], and one a non-significant trend toward improvement t [51]. While our findings are consistent with seven prior reviews [19, 29, 30, 57, 58, 60, 61] suggesting multifaceted interventions are more effective than single-component interventions, a recent overview of systematic reviews found that multifaceted interventions are no more effective than single-component interventions [62]. However their findings should be interpreted with caution considering the following limitations: First, the authors limited their search to reviews available on the Rx-for-Change database. Second, they did not search the ‘grey literature’, possibly omitting other relevant work in the field. Third, they did not retrieve data from the original studies that comprised the included reviews, thereby having to rely on the information reported by the review authors. Fourth, they relied on reviews that mainly used non-statistical analyses, so they did not account for the effect sizes of individual studies. Fifth, the included reviews were comprised of different methodological designs (i.e. RCTs, controlled trials, interrupted time series, etc.), whereas this review considered only RCTs.

Finally, four included studies suggested that multifaceted interventions delivered to professionals were ineffective in improving patient outcomes [46, 51, 52, 54]. Similar findings were reported by other reviews targeting physiotherapists [30, 32]. Bekkering et al. (2005) [52] and Rebbeck et al. (2006) [54] attributed the lack of effect of KT interventions on patient outcomes to the high quality care delivered by physiotherapists mitigating further improvement in patient health. Other authors suggested instead this may be due to unmeasured patient’s characteristics (e.g., fear avoidance and depression) moderating the effect on patient outcomes [46], or to the small effect of individual components include in the KT interventions evaluate in these RCTs [51]. For instance adding outreach visits may increase the likelihood of improving outcomes.

About half of the included studies indicated using theoretical frameworks, theories or models to guide the design of the behavior change intervention [49, 50, 52, 53, 56]. Only one of the studies provided a rationale for choosing a specific theory and a description of how using such theories informed intervention design [56]. This is in part because KT frameworks had not been developed when some of the primary RCTs were designed.

Findings from this review suggest that multifaceted educational interventions appear to be effective for improving professional outcomes. However, several elements ought to be improved in future trials to increase our confidence regarding the effect of multifaceted interventions, including: better reporting of providers’ characteristics and level of training; theoretical framework used to support behavior change; intervention components; and the implementation fidelity. Larger sample sizes and a clear rationale for selecting each component of the KT intervention are also needed [33].

Because of the nature and the scope of practice of each MSK profession, the success of specific KT interventions for one profession may not necessarily be successfully replicated among other health professions [19]. Improving the reporting of intervention elements may help explain why certain KT interventions are effective or ineffective, in particular with respect to multifaceted components, and whether more effective interventions are likely to also work with other MSK professionals or for other disorders [59]. Mapping behavior change techniques to previously identified barriers when designing KT interventions may improve the likelihood of successful professional behaviour change and improve patient health outcomes [63,64,65,66].

The strength of this review stemmed from the rigorous search strategy it employed. It captured more studies than antecedent reviews [19, 29, 57, 58] within relevant areas over similar periods. The search strategy we used was recently validated and recommended by Cochrane and Rx for change, helping capture studies other reviews did not identify [48, 49]. Moreover, the present study covered a wide spectrum of MSK disorders and health care professionals. To our knowledge, this is the first review to report on the use of single-component interventions from RCTs for MSK disorders. Other reviews reported on the use of single-component interventions in non-RCT designs [19, 29, 57, 58]. Furthermore, other reviews had not reported the intervention details, for instance, Ospina et al. (2013) [57] classified both Bekkering et al. (2005) [52] and Stevenson et al. (2006) [53] under single-component strategies when in fact, these should be classified under multifaceted strategies as also reported in other reviews [19, 29, 58]. The authors may have overestimated the effect of multifaceted interventions in those reviews.

Study limitations

Despite these strengths, this review has several limitations. First, the search was restricted to studies published in English. Second, studies were mainly conducted in western countries which may restrict the generalizability of our findings. Third, a graphical representation of the publication bias using funnel plots was not possible as there were no comparable outcome measures. However, this review controlled for the effect of multiple publication biases in terms of the results. This is important as studies with significant findings often have multiple publications [67] which could lead to overestimation of the intervention’s impacts in reviews [68, 69]. We identified two multiple publications we presented as a single study. Data extraction was not double-blinded which may be a source of bias. This review did not identify any pragmatic studies. Fourth, our review included RCTs only to minimize bias and confounding. Nonetheless, RCTs are not without limitations (e.g., population availability, contamination, time for follow-up, external validity, cost) [70]. The integration of multiple study designs could have better informed ‘real-world’ clinical practice and the many facets of patient relevant issues [71]. Fifth, patient reported outcomes concepts/domains and time points for assessment should closely align with the trial objectives and hypotheses [72]. The use of measures such as health-related quality of life and coping may be more relevant and sensitive indicators of success in KT trials than specific symptoms such as pain.

Conclusion

This review is one of the first to summarize studies on the effectiveness of KT interventions to improve the uptake and application of clinical practice guidelines and best practices specific to MSK disorders among a wide range of MSK professionals. The findings showed that primary trials use a variety of educational approaches with favorable but inconsistent impact on professional outcomes. Very few studies reported the effect on patient outcomes and results tended to be negative. The overall quality of included RCTs was poor. There was poor reporting of the interventions and a lack of reporting the way theoretical frameworks were implemented in the included trials.

Abbreviations

- KT:

-

Knowledge translation

- LBP:

-

Low back pain

- MSK:

-

Musculoskeletal

- OA:

-

Osteoarthritis

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trials

References

Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2197–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4.

Smith E, Hoy DG, Cross M, Vos T, Naghavi M, Buchbinder R, et al. The global burden of other musculoskeletal disorders: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(8):1462–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204680.

March L, Smith EU, Hoy DG, Cross MJ, Sanchez-Riera L, Blyth F, et al. Burden of disability due to musculoskeletal (MSK) disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2014;28(3):353–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2014.08.002.

Bove SE, Flatters SJ, Inglis JJ, Mantyh PW. New advances in musculoskeletal pain. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60(1):187–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.012. Epub Dec 25.

Das SK, Farooqi A. Osteoarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22(4):657–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2008.07.002.

Breivik H, Borchgrevink PC, Allen SM, Rosseland LA, Romundstad L, Hals EK, et al. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101(1):17–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aen103. Epub 2008 May 16

McBeth J, Jones K. Epidemiology of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21(3):403–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2007.03.003.

Asche CV, Kirkness CS, McAdam-Marx C, Fritz JM. The societal costs of low back pain: data published between 2001 and 2007. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2007;21(4):25–33.

Luo X, Pietrobon R, Sun SX, Liu GG, Hey L. Estimates and patterns of direct health care expenditures among individuals with back pain in the United States. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29(1):79–86. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.BRS.0000105527.13866.0F.

Holm LW, Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Hogg-Johnson S, Cote P, Guzman J, et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in whiplash-associated disorders after traffic collisions: results of the bone and joint decade 2000-2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(4 Suppl):S52–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181643ece.

Makela M, Heliovaara M, Sievers K, Knekt P, Maatela J, Aromaa A. Musculoskeletal disorders as determinants of disability in Finns aged 30 years or more. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(6):549–59.

Dagenais S, Caro J, Haldeman S. A systematic review of low back pain cost of illness studies in the United States and internationally. Spine J. 2008;8(1):8–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2007.10.005.

Koes BW, van Tulder M, Lin CW, Macedo LG, McAuley J, Maher C. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(12):2075–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-010-1502-y.

Pillastrini P, Gardenghi I, Bonetti F, Capra F, Guccione A, Mugnai R, et al. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for chronic low back pain management in primary care. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79(2):176–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2011.03.019.

Delitto A, George SZ, Van Dillen LR, Whitman JM, Sowa G, Shekelle P, et al. Low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(4):A1–57. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2012.0301.

Wallace J, Nwosu B, Clarke M. Barriers to the uptake of evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses: a systematic review of decision makers’ perceptions. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e001220. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001220.

Shirazi KK, Wallace LM, Niknami S, Hidarnia A, Torkaman G, Gilchrist M, et al. A home-based, transtheoretical change model designed strength training intervention to increase exercise to prevent osteoporosis in Iranian women aged 40-65 years: a randomized controlled trial. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(3):305–17.

Graham ID, Tetroe JM. Getting evidence into policy and practice: perspective of a health research funder. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;18(1):46–50.

Scott SD, Albrecht L, O’Leary K, Ball GD, Hartling L, Hofmeyer A, et al. Systematic review of knowledge translation strategies in the allied health professions. Implement Sci. 2012;7:70. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-70.

Flodgren G, Eccles MP, Shepperd S, Scott A, Parmelli E, Beyer FR. An overview of reviews evaluating the effectiveness of financial incentives in changing healthcare professional behaviours and patient outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;7:CD009255. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009255.

Vergouwen AC, Bakker A, Katon WJ, Verheij TJ, Koerselman F. Improving adherence to antidepressants: a systematic review of interventions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(12):1415–20.

Williams JW Jr, Gerrity M, Holsinger T, Dobscha S, Gaynes B, Dietrich A. Systematic review of multifaceted interventions to improve depression care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29(2):91–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.12.003.

Kawamoto K, Lobach DF. Clinical decision support provided within physician order entry systems: a systematic review of features effective for changing clinician behavior. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2003;2003:361–5.

Siddiqui MR, Sajid MS, Khatri K, Kanri B, Cheek E, Baig MK. The role of physician reminders in faecal occult blood testing for colorectal cancer screening. Eur J Gen Pract. 2011;17(4):221–8. https://doi.org/10.3109/13814788.2011.601412.

Randell R, Mitchell N, Dowding D, Cullum N, Thompson C. Effects of computerized decision support systems on nursing performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2007;12(4):242–9. https://doi.org/10.1258/135581907782101543.

Thompson DS, Estabrooks CA, Scott-Findlay S, Moore K, Wallin L. Interventions aimed at increasing research use in nursing: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2007;2:15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-2-15.

Thompson C, Stapley S. Do educational interventions improve nurses’ clinical decision making and judgement? A systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(7):881–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.12.005.

Foxcroft DR, Cole N. Organisational infrastructures to promote evidence based nursing practice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;4:CD002212. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002212.

Menon A, Korner-Bitensky N, Kastner M, McKibbon KA, Straus S. Strategies for rehabilitation professionals to move evidence-based knowledge into practice: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41(13):1024–32. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-0451.

van der Wees PJ, Jamtvedt G, Rebbeck T, de Bie RA, Dekker J, Hendriks EJM. Multifaceted strategies may increase implementation of physiotherapy clinical guidelines: a systematic review. Aust J Physiother. 2008;54(4):233–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0004-9514(08)70002-3

Jones CA, Roop SC, Pohar SL, Albrecht L, Scott SD. Translating knowledge in rehabilitation: systematic review. Phys Ther. 2015;95(4):663–77. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20130512.

Bérubé M-È, Poitras S, Bastien M, Laliberté L-A, Lacharité A, Douglas PG. Strategies to translate knowledge related to common musculoskeletal conditions into physiotherapy practice: a systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2018;104(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2017.05.002.

Higgins JPT, Green S, (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from http://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/.

Search Strategies Rx for Change. Professional. In: Organisational and Consumer Interventions; 2014. https://www.cadth.ca/media/media/Search%20Strategies%20Rx%20for%20Change%20April%202014.pdf.

Hennekens CH, DeMets D. Statistical association and causation: contributions of different types of evidence. JAMA. 2011;305(11):1134–5. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.322.

Chalmers I. Unbiased, relevant, and reliable assessments in health care: important progress during the past century, but plenty of scope for doing better. BMJ. 1998;317(7167):1167–8.

Juni P, Holenstein F, Sterne J, Bartlett C, Egger M. Direction and impact of language bias in meta-analyses of controlled trials: empirical study. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(1):115–23.

Moher D, Fortin P, Jadad AR, Juni P, Klassen T, Le Lorier J, et al. Completeness of reporting of trials published in languages other than English: implications for conduct and reporting of systematic reviews. Lancet. 1996;347(8998):363–6.

Moher D, Pham B, Lawson ML, Klassen TP. The inclusion of reports of randomised trials published in languages other than English in systematic reviews. Health Technol Assess. 2003;7(41):1–90.

Morrison A, Polisena J, Husereau D, Moulton K, Clark M, Fiander M, et al. The effect of English-language restriction on systematic review-based meta-analyses: a systematic review of empirical studies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012;28(2):138–44. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462312000086.

Sutton AJ, Duval SJ, Tweedie RL, Abrams KR, Jones DR. Empirical assessment of effect of publication bias on meta-analyses. BMJ. 2000;320(7249):1574–7.

Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Review Group. Data collection checklist. Available from <http://epoc.cochrane.org/sites/epoc.cochrane.org/files/uploads/datacollectionchecklist.pdf> (Accessed February 6, 2015).

Samuel BG. How many subjects does it take to do a regression analysis? Multivar Behav Res. 1991;26:499–510.

Durlak JA. How to select, calculate, and interpret effect sizes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34(9):917–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsp004.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge Academic: New York, NY; 1988.

Cleland JA, Fritz JM, Brennan GP, Magel J. Does continuing education improve physical therapists’ effectiveness in treating neck pain? A randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2009;89(1):38–47.

Bussières A, Laurencelle L, Peterson C. Diagnostic imaging guidelines implementation study for spinal disorders: a randomized trial with postal follow-ups. Journal of Chiropractic Education (Association of Chiropractic Colleges). 2010;24(1):2–18.

Evans DW, Breen AC, Pincus T, Sim J, Underwood M, Vogel S, et al. The effectiveness of a posted information package on the beliefs and behavior of musculoskeletal practitioners: the UK chiropractors, osteopaths, and musculoskeletal physiotherapists low back pain ManagemENT (COMPLeMENT) randomized trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35(8):858–66. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181d4e04b.

Peter WF, van der Wees PJ, Verhoef J, de Jong Z, van Bodegom-Vos L, Hilberdink WK, et al. Postgraduate education to increase adherence to a Dutch physiotherapy practice guideline for hip and knee OA: a randomized controlled trial. Rheumatology. 2013;52(2):368–75.

Peter W, van der Wees PJ, Verhoef J, de Jong Z, van Bodegom-Vos L, Hilberdink WK, et al. Effectiveness of an interactive postgraduate educational intervention with patient participation on the adherence to a physiotherapy guideline for hip and knee osteoarthritis: a randomised controlled trial. Disability & Rehabilitation. 2015;37(3):274–82.

Chipchase LS, Cavaleri R, Jull G. Can a professional development workshop with follow-up alter practitioner behaviour and outcomes for neck pain patients? A randomised controlled trial. Man Ther. 2016;25:87–93.

Bekkering GE, van Tulder MW, Hendriks EJ, Koopmanschap MA, Knol DL, Bouter LM, et al. Implementation of clinical guidelines on physical therapy for patients with low back pain: randomized trial comparing patient outcomes after a standard and active implementation strategy. Phys Ther. 2005;85(6):544–55.

Stevenson K, Lewis M, Hay E. Does physiotherapy management of low back pain change as a result of an evidence-based educational programme? J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12(3):365–75.

Rebbeck T, Maher CG, Refshauge KM. Evaluating two implementation strategies for whiplash guidelines in physiotherapy: a cluster randomised trial. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy. 2006;52(3):165–74.

van Dulmen SA, Maas M, Staal JB, Rutten G, Kiers H, Nijhuis-van der Sanden M, et al. Effectiveness of peer assessment for implementing a Dutch physical therapy low back pain guideline: cluster randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2014;94(10):1396–409. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20130286.

Murray A, Hall AM, Williams GC, McDonough SM, Ntoumanis N, Taylor IM, et al. Effect of a self-determination theory–based communication skills training program on Physiotherapists’ psychological support for their patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2015;96(5):809–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2014.11.007.

Ospina MB, Taenzer P, Rashiq S, MacDermid JC, Carr E, Chojecki D, et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness of knowledge translation interventions for chronic noncancer pain management. Pain Res Manag. 2013;18(6):e129–41.

Jones CA, Roop SC, Pohar SL, Albrecht L, Scott SD. Translating knowledge in rehabilitation: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2014;95(4) https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20130512.

Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas R, Mowatt G, Fraser C, Bero L, et al. Changing provider behavior: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Med Care. 2001;39(8 Suppl 2):Ii2–45.

Davis DA, Thomson MA, Oxman AD, Haynes RB. Changing physician performance. A systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies. JAMA. 1995;274(9):700–5.

Wensing M, Grol R. Single and combined strategies for implementing changes in primary care: a literature review. Int J Qual Health Care. 1994;6(2):115–32.

Squires JE, Sullivan K, Eccles MP, Worswick J, Grimshaw JM. Are multifaceted interventions more effective than single-component interventions in changing health-care professionals’ behaviours? An overview of systematic reviews. Implement Sci. 2014;9:152. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-014-0152-6.

Albada A, Ausems MG, Bensing JM, van Dulmen S. Tailored information about cancer risk and screening: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(2):155–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.005.

Glanz K, Bishop DB. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:399–418. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103604.

Evans C, Gilbert JR, Taylor W, Hildebrand A. A randomized controlled trial of flexion exercises, education, and bed rest for patients with acute low back pain. Physiother Can. 1987;39(2):96–101.

Webb TL, Joseph J, Yardley L, Michie S. Using the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12(1):e4. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1376.

Easterbrook PJ, Berlin JA, Gopalan R, Matthews DR. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet. 1991;337(8746):867–72.

Tramer MR, Reynolds DJ, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Impact of covert duplicate publication on meta-analysis: a case study. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):635–40.

Huston P, Moher D. Redundancy, disaggregation, and the integrity of medical research. Lancet. 1996;347(9007):1024–6.

Sanson-Fisher RW, Bonevski B, Green LW, D’Este C. Limitations of the randomized controlled trial in evaluating population-based health interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(2):155–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.007.

Peinemann F, Tushabe DA, Kleijnen J. Using multiple types of studies in systematic reviews of health care interventions – a systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e85035. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0085035.

Calvert M, Kyte D, Mercieca-Bebber R, Slade A, Chan AW, King MT, et al. Guidelines for inclusion of patient-reported outcomes in clinical trial protocols: the SPIRIT-PRO extension. JAMA. 2018;319(5):483–94. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.21903.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Pamela Anderson for helping in reviewing the search strategy.

Availability of data and materials

The data set(s) supporting the results of this article is (are) included within the article and its additional file(s).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FZ adapted the study design, contributed to the development of the interview guide, analysed and interpreted the data, wrote the initial manuscript. AEB oversaw all phases of the study. AM and NEM contributed to the study design, development of the interview guide, analyses and interpretation of the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

FZ has clinical training in physical therapy with an MSc degree in professional physical therapy, a thesis-based master in rehabilitation science, and a PhD candidate in Rehabilitation Science from the School of Physical and Occupational Therapy at McGill University. AEB has clinical training in nursing and chiropractic with over 15 years of clinical experience and holds a faculty position at the School of Physical and Occupational Therapy at McGill University and in the chiropractic department at l’Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières. He holds a Canadian Chiropractic Research Foundation (CCRF) chair in Epidemiology and Rehabilitation at McGill University. AM is assistant professor and academic associate at the School of Physical and Occupational Therapy at McGill University. She is also Project Director of the Edith Strauss Rehabilitation Research Projects. NEM is the James McGill Professor in the Department of Medicine and the School of Physical and Occupational Therapy at McGill University. She is one of Canada’s best known researchers in stroke rehabilitation. She is a health outcomes, health services, and population health researcher with interests in all aspects of disability and quality of life in people with chronic diseases and the elderly.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This systematic review did not collect data from participants. Therefore, research ethical approval and consent to participate were not required.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Search strategy. (PDF 264 kb)

Additional file 2:

Characteristics of excluded studies. (PDF 463 kb)

Additional file 3:

The main characteristics of KT interventions and their effectiveness of the professional outcomes. (DOCX 29 kb)

Additional file 4:

The main characteristics of KT interventions and their effectiveness on patient outcomes. (DOCX 18 kb)

Additional file 5:

Elements of KT interventions and use of theoretical frameworks, models or theories. (DOCX 31 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

AL Zoubi, F.M., Menon, A., Mayo, N.E. et al. The effectiveness of interventions designed to increase the uptake of clinical practice guidelines and best practices among musculoskeletal professionals: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 18, 435 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3253-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3253-0