Abstract

Background

Knowledge translation (KT, also known as research utilization, and sometimes referring to implementation science) is a dynamic and iterative process that includes the synthesis, dissemination, exchange, and ethically sound application of knowledge to improve health. A KT intervention is one which facilitates the uptake of research. The long-term sustainability of KT interventions is unclear. We aimed to characterize KT interventions to manage chronic diseases that have been used for healthcare outcomes beyond 1 year or beyond the termination of initial grant funding.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review by searching MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Campbell from inception until February 2013. We included experimental, quasi-experimental, and observational studies providing information on the sustainability of KT interventions for managing chronic diseases in adults and focusing on end-users including patients, clinicians, public health officials, health service managers, and policy-makers. Articles were screened and abstracted by two reviewers, independently. The data were charted and results described narratively.

Results

We included 62 studies reported in 103 publications (total 260,688 patients) plus 41 companion reports after screening 12,328 titles and abstracts and 464 full-text articles. More than half of the studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The duration of the KT intervention ranged from 61 to 522 weeks. Nine chronic conditions were examined across the studies, such as diabetes (34 %), cardiovascular disease (28 %), and hypertension (16 %). Thirteen KT interventions were reported across the studies. Patient education was the most commonly examined (20 %), followed by self-management (17 %). Most studies (61 %) focused on patient-level outcomes (e.g. disease severity), while 31 % included system-level outcomes (e.g. number of eye examinations), and 8 % used both. The interventions were aimed at the patient (58 %), health system (28 %), and healthcare personnel (14 %) levels.

Conclusions

We found few studies focusing on the sustainability of KT interventions. Most of the included studies focused on patient-level outcomes and patient-level KT interventions. A future systematic review can be conducted of the RCTs to examine the impact of sustainable KT interventions on health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Evidence from systematic reviews suggests that numerous knowledge translation (KT) interventions are effective [1, 2]. A KT intervention is one which facilitates the uptake of research into practice and/or policy and can also be referred to as research utilization. When KT interventions are aimed at the clinician, organization, or health system level, these can also be considered implementation science interventions. In order to increase the uptake of KT interventions, researchers within the KT field have focused on surmounting barriers to their initial implementation [3, 4]. However, less research has been done to examine the long-term sustainability of KT interventions [5–8], which can be defined as the extent to which a KT intervention continues after adoption has been secured [9].

The sustainability of KT interventions is paramount to ensure the long-term quality of care for patients [10–13]. It has been suggested that KT interventions that are not sustained in the long-term may result in worse patient outcomes [10, 11, 14], such as decreased quality of care and quality of life. As such, evaluating sustainability is increasingly important in the field of KT [5–8].

Sustainability of interventions is particularly critical in the management of patients with chronic diseases. Half of all US adults (117 million people) have at least 1 chronic condition; 26 % of US adults have ≥2 chronic conditions (including diabetes, hypertension, cancer, arthritis, vascular disease, depression, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], and dementia) [15]. More chronic conditions translate to increased risks of functional limitations and admission to acute and long-term care hospitals. In 2006, 84 % of all US healthcare spending was for the 50 % of the population who have ≥2 chronic conditions [16]. This situation is not unique to the US. Chronic diseases are increasing rapidly in prevalence and are recognized by the World Health Organization as the major challenge facing health systems worldwide [17]. Our decision-maker partners [18] have identified sustainability of KT interventions to be a particular challenge in chronic disease management, as most research initiatives and pilot project focus on short-term implementation, yet this does not reflect the needs of the healthcare system [18]. For example, in a recent systematic review of effective KT strategies for coordination of care to reduce use of healthcare services by those who are identified as “frequent users of healthcare” (i.e. those with chronic disease), the majority of the 36 included studies lasted less than 12 months; with just 1 study extending to 3 years [19]. Yet, these patients have chronic disease, implying the intervention should extend beyond 1 year to reflect the course of their disease.

Frameworks for implementing sustainability interventions as well as for measuring sustainability have been proposed [6, 7, 20, 21]. Chambers and colleagues developed a “Dynamic Sustainability Framework” for sustainability involving “continued learning and problem solving, ongoing adaptation of interventions with a primary focus on fit between interventions and multi-level contexts, and expectations for ongoing improvement as opposed to diminishing outcomes over time” [6]. Doyle and colleagues conducted a formative evaluation of the National Health Service Institute for Innovation and Improvement Sustainability Model (SM), which provides information on 10 factors that may improve sustainability for teams who are implementing new practice in their organization [7]. Schell et al. developed a sustainability framework specific to public health interventions that includes nine domains that are essential for success [20]. Simpson et al. describe their model that was developed to sustain oral health interventions including addressing barriers and considering contextual factors [21]. These frameworks are likely useful for empirical research to develop, implement, or measure sustainability of KT interventions. However, this has not been formally evaluated.

We aimed to conduct a scoping review of KT intervention research to characterize KT interventions to manage chronic disease that have been used for healthcare outcomes beyond 1 year or beyond the termination of funding. We also aimed to determine the uptake of frameworks that focus on the sustainability of KT interventions in the included studies.

Methods

Protocol

A protocol for our scoping review was developed using the methods of Arksey and O’Malley [22] and others [23] and published in a peer-reviewed journal [24]. A scoping review “maps the concepts underpinning a research area and identifies the main sources and types of evidence available. Scoping reviews can be used to identify gaps in knowledge, establish research agendas, and discuss implications for decision-making” [25]. Since the full methods have been published, they are only described briefly in this paper.

Eligibility criteria

We included studies that targeted adults with chronic disease (excluding mental illness) who received a KT intervention (which may have targeted the patient, their healthcare provider, or the health system). The list of chronic diseases is presented in Additional file 1. Studies including patients with chronic diseases but without specifying the conditions were included. All comparators were eligible for inclusion, such as other KT interventions or usual care. The study designs included were experimental (randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-RCTs, non-RCTs), quasi-experimental (controlled before-after studies, interrupted time series), and observational studies with a comparator group(s) (i.e. comparative cohort and case control studies).

There is a lack of clarity and agreement on the definition (and the term) for sustainability [8]. Given our focus on chronic disease management, the evidence from the systematic review on KT interventions for those who are identified as “frequent users of the healthcare system,” [19] and in discussion with our knowledge users, it was felt that we should focus on studies that extended beyond 1 year of initial implementation to reflect the critical health system challenge. Moreover, given that a common concern of funders is what happens when research funding for a KT intervention ends [26], it was decided to also include those studies that looked at sustainability after the termination of research funds. As such, studies lasting more than 1 year after implementation or the termination of the study funding across all clinical settings were included.

Information sources and literature search

Comprehensive literature searches were conducted from inception until February 2013 in the MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and the Campbell databases. The MEDLINE search strategy was peer-reviewed by another librarian using the PRESS checklist [27] and is available in our protocol publication [24]. Search terms included durability, fidelity, sustainability, institutionalization, routinization, longitudinal and long-term. The search strategies for the other databases are available from the corresponding author upon request. References from 15 relevant review articles [11, 28–41] were searched to identify any additional studies.

Study selection process

The team calibrated the eligibility criteria using a random sample of 50 titles and abstracts screened independently by each reviewer. Two calibration exercises (using 50 records each time) were necessary for the team to reach 90 % agreement after clarifications on eligibility criteria were discussed amongst the team. Subsequently, pairs of team members independently screened the titles and abstracts for inclusion. Disagreements were resolved by discussion amongst pairs of reviewers or with a third member, if required. The same process was followed for full-text screening, except that 2 calibration exercises of 15 random full-text articles occurred prior to achieving 90 % agreement.

Data items and data abstraction process

The abstracted data included terminology used to describe sustainability, study characteristics (e.g. type of study design, year of study conduct, funding source, KT duration), patient characteristics (e.g. number of patients, number of clusters, type of chronic condition), outcomes examined, and interventions (e.g. frequency, duration, provider, target). A post hoc analysis was conducted to determine whether sustainability frameworks were used to inform the included studies. Using a random sample of five included studies, the pre-specified data abstraction form was calibrated amongst the team. Three such exercises were necessary prior to embarking on full data abstraction, which was undertaken by pairs of team members independently. A third team member verified all of the abstracted data by comparing the data abstraction with the original papers, to ensure accuracy. The KT interventions were coded independently by a clinician (SES) and a methodologist (ACT) on our team using a pre-existing taxonomy originally developed by the Cochrane EPOC group, revised by members of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and used in subsequent publications (Additional file 2) [42]. Conflicts in the KT intervention codes were resolved through discussion. Companion reports were identified by matching the authors, KT intervention, and timeframe for the study conduct. The main report was the one with the longest duration of follow-up; companion reports were used for supplementary material only.

Methodological quality appraisal

We did not appraise methodological quality or risk of bias of the included articles because this is a scoping review. This approach is consistent with scoping reviews of clinical topics [43].

Synthesis

The abstracted data from the included studies were charted using frequencies for the following variables: year of publication, study period, geographic region of conduct, study design, source of funding, duration of KT intervention, setting, duration of follow-up, number of patients, age range, percent female, type of chronic disease, number of conditions, type of KT intervention, target of KT intervention, level of KT intervention, fidelity of the KT intervention (defined as “the consistency and quality of targeted organizational members’ use of the specific innovation” [44]), whether the KT intervention was adapted for the setting, types of outcomes examined, and who the target was for the outcomes. Gaps in the literature were identified, as well as areas for future systematic reviews. Word clouds were drawn using the online program Wordle [45] for the terms used to describe sustainability (as described by study authors).

Results

Literature search

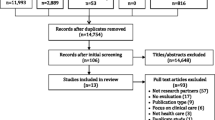

After screening 12,328 citations and 464 full-text papers, 62 studies (plus 41 companion reports) were included. Details of search results per database and the duplicates removed are presented in Fig. 1. The full list of citations for the included studies can be found in Additional file 3.

Terminology for sustainability

Only 15 % (8/62) of the included studies defined or described sustainability. The first study to provide a definition was published in 1996, where the authors described this as occurring when patient results identified earlier remain when the treatment groups have returned to routine care [46]. Six of the eight studies describing sustainability were published after 2005. Most focused on sustainability of interventions or outcomes or treatment goals. In addition, 79 % (49/62) used a term to describe sustainability. Of the studies providing a term for sustainability, the most commonly used term for sustainability was long-term (29/77, 38 %), which was followed by sustain (24/77, 31 %), maintain (8/77, 10 %), and adhere (6/77, 8 %) (Fig. 2). The use of the terms long-term and sustain were consistent over time. Figure 2 presents a word cloud of the sustainability terminology used in the included studies, with larger words representing more frequent usage. Further details of the nine definitions identified and the other terms used are presented in Additional file 4.

Study characteristics

The year of publication ranged from 1979 to 2012, while the study conduct period ranged from 1974 to 2010 (Table 1). More than half of the studies were published after 2003, suggesting that KT sustainability is a relatively new concept for KT research. The studies were most commonly conducted in North America (39/62, 63 %) and Europe (16/62, 26 %). More than half of the included studies were RCTs. The funding source was most commonly a governmental organization (23 %) or not reported (24 %). The duration of the KT intervention was 61 to 104 weeks in 61 % of included studies (range 61–522 weeks) and the total duration of follow-up was 61 to 104 weeks in 55 % of studies. Most of the study settings were multi-site (58 %), and most had two study arms (82 %). Further details, including specific study site, study setting, and organizational context, can be found in Additional file 4.

Patient characteristics

Across all studies, the total number of included patients was 260,688, with an average of 4495 patients per study. Their age ranged from 18 to 99 years and the average percent female was approximately 48. Most of the studies included patients with a single condition (87 %), with diabetes being the most common (34 %) (Table 2). Further data on the patient characteristics, including end-users, comorbidities, risk factors, history of treatment utilization, concomitant therapies, and eligibility criteria, can be found in Additional file 5.

KT interventions

A total of 13 interventions were identified (Table 3). The interventions were delivered at the patient (58 %), health system (28 %), and healthcare personnel (14 %) levels, using the previous coding scheme for the different KT interventions. The most commonly examined type of KT intervention was patient education (83/409, 20 %), followed by self-management (70/409, 17 %) (Table 3). In contrast, the least commonly used KT interventions were continuous quality improvement (5/409, 1 %) and facilitated relay of clinical information (5/409, 1 %). Interventions were commonly targeted to patients (236/315, 75 %) and healthcare providers (49/315, 16 %). A detailed description of the interventions examined across the studies can be found in Additional files 6 and 7.

Most of the studies did not mention adaptation (i.e. whether the intervention was adapted or changed over time) (56/62, 90 %) or fidelity (59/62, 95 %) of the intervention.

Outcome characteristics

The most commonly used outcome was healthcare utilization (142/628 outcomes reported across the studies, 23 %) (Table 4, Additional file 8). Most studies (61 %) focused on patient-level outcomes (e.g. disease severity), while 31 % included system-level outcomes (e.g. number of eye examinations) and 8 % used both. None of the studies reported the use of outcomes to assess for sustainability.

Use of frameworks on sustainability

Our post hoc analysis indicated that none of the included studies reported using a framework to develop, implement, or measure sustainability.

Discussion

It has been postulated that while nearly $300 billion is spent on research globally, much of this is wasted because of poor implementation [47–50]. Sources of waste include lack of consideration of sustainability of effective interventions. This waste is a particular challenge when considering how to optimize care of patients with chronic diseases given the growing proportion of these patients and their impact on health systems. Our scoping review found limited studies on sustainability of KT interventions for people with chronic diseases. Similar to what was postulated in a consensus project on gaps in sustainability research [8], we found that there is a need for clarity on the terms and definitions used to describe sustainability, which would enhance our ability to find this literature.

In addition, we found few studies that tested KT interventions beyond 2 years. This could be due to various reasons, such as a lack of funding or the belief that KT sustainability is not the top priority. As well, we were unable to identify any studies that used a framework to develop, implement, or measure sustainability of KT interventions. This would allow individuals to test different models of sustainability to determine which ones are the most optimal. Our results suggest that KT sustainability is in its infancy in the literature.

To ensure longevity, it has been suggested that planning for sustainability should be done early, when KT interventions are being designed [51]. In particular, theories, process models, and frameworks should be considered when trying to develop, implement, or evaluate KT interventions and their sustainability. However, our review found no studies that reported use of a framework to consider sustainability of a KT intervention. Testing sustainability frameworks empirically is also an area of future research. Moreover, the studies focused on KT interventions focused on single chronic diseases rather than patients with multiple conditions, failing to reflect the complexities of real-world clinical practice and policy.

It is plausible to postulate that depending on the nature and target audience of the intervention, the type of sustainability effort may differ. For example, a simple KT intervention in a clinical setting targeting patients (such as patient reminders) might not require extensive sustainability endeavours. However, more complex KT interventions at the organization or health system level (i.e. implementation science), such as financial incentives, may require more extensive sustainability initiatives. This is an area for future empirical research.

Most of the included studies focused on KT interventions at the patient level, such as patient education and self-management. This finding might be explained by accessibility of the KT intervention; for example, patient-oriented interventions are often easier to employ than more resource-intensive interventions, such as team changes or case management. Across all of the chronic conditions examined by the included studies, the most common was diabetes.

Although we did not formally appraise the methodological quality of included studies, we identified some limitations worth noting. Most of the studies did not mention fidelity or adaptation of the intervention, which should be mentioned in future KT sustainability studies to increase transparency and quality of reporting; indeed, these elements have been suggested in the checklist proposed to enhance reporting of interventions (TIDieR) [52]. As well, the quality of reporting of these studies was low overall and could be improved. For example, the duration of the KT intervention period was difficult to discern across the included studies. In addition, our results found a significant gap in “sustainability” terminology, with only nine (15 %) included studies providing a definition, and the individual terms used were not consistent across studies.

There are some limitations to our scoping review process that are worth mentioning. Due to the large number of citations identified (>12,000), we were unable to search unpublished literature or include studies on mental illness because of resource restraints. Although this is a deviation from our protocol [24], only half of the published scoping reviews in the literature do an extensive search for grey literature [43]. As well, we had hoped to develop a framework for developing, implementing or evaluating sustainability of KT interventions for chronic disease management but were unable to do so due to the dearth of included studies. Since sustainability was poorly reported across studies, we were also unable to formally evaluate factors that influence sustainability of KT interventions. Our scoping review was resource- and time-intensive due to the large screening yield, as well as the unanticipated time required to independently categorize the 13 identified KT interventions, which appeared 464 times across the included papers. Although our literature search is outdated, the purpose of our scoping review was to chart the literature on sustainability initiatives and identify areas to inform the conduct of a future systematic review. We are currently in the process of updating the literature search from our scoping review, focusing on RCTs. We have identified 31 randomized trials through our scoping review and plan to statistically evaluate the impact of sustainable KT interventions on health outcomes through meta-analysis in our future systematic review.

Conclusions

We found few studies that focused on sustainability of KT interventions. Most of the included studies focused on patient-level outcomes and patient-level KT interventions. A future systematic review can be conducted of the RCTs to examine the impact of sustainable KT interventions on health outcomes. Our results showed several gaps in the literature worth exploring in future research. In particular, our findings suggest that more work is needed on exploring sustainability of KT interventions for patients with chronic diseases.

Abbreviations

- KT:

-

knowledge translation

- RCTs:

-

randomized controlled trials

References

The Cochrane Collaboration. Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group. 2015. http://epoc.cochrane.org/. Accessed November 2015.

Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, Squires JE. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci. 2012;7:50.

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82(4):581–629.

Glasgow RE, Chambers D. Developing robust, sustainable, implementation systems using rigorous, rapid and relevant science. Clin Transl Sci. 2012;5(1):48–55.

Chambers LL. Factors for sustainability of evidence-based practice innovations: part I. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2015;29(2):89–93.

Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci. 2013;8:117.

Doyle C, Howe C, Woodcock T, Myron R, Phekoo K, McNicholas C, et al. Making change last: applying the NHS institute for innovation and improvement sustainability model to healthcare improvement. Implement Sci. 2013;8:127.

Proctor E, Luke D, Calhoun A, McMillen C, Brownson R, McCrary S, et al. Sustainability of evidence-based healthcare: research agenda, methodological advances, and infrastructure support. Implement Sci. 2015;10:88.

Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 5th ed. New York: Free Press; 2005.

Scheirer MA. Is sustainability possible? A review and commentary on empirical studies of program sustainability. Am J Eval. 2005;26(3):320–47.

Wiltsey Stirman S, Kimberly J, Cook N, Calloway A, Castro F, Charns M. The sustainability of new programs and innovations: a review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:17.

McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks J, DeCristofaro A, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2635–45.

Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629–40.

Ham C, Kipping R, McLeod H. Redesigning work processes in health care: lessons from the National Health Service. Milbank Q. 2003;81(3):415–39.

Ward BW, Schiller JS, Goodman RA. Multiple chronic conditions among US adults: a 2012 update. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E62.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. 2015. http://www.rwjf.org/en.html. Accessed November 2015.

World Health Organization. Chronic diseases and health promotion. 2015. http://www.who.int/chp/en/. Accessed November 2015.

Health Quality Ontario (HQO). Quality Improvement. 2015. http://www.hqontario.ca/Quality-Improvement/Tools-and-Resources. Accessed November 2015.

Tricco AC, Antony J, Ivers NM, Ashoor HM, Khan PA, Blondal E, et al. Effectiveness of quality improvement strategies for coordination of care to reduce use of health care services: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2014;186(15):E568–78.

Schell SF, Luke DA, Schooley MW, Elliott MB, Herbers SH, Mueller NB, et al. Public health program capacity for sustainability: a new framework. Implement Sci. 2013;8:15.

Simpson DD. A framework for implementing sustainable oral health promotion interventions. J Public Health Dent. 2011;71(s1):S84–s94.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–6.

Tricco AC, Cogo E, Ashoor H, Perrier L, McKibbon KA, Grimshaw JM, et al. Sustainability of knowledge translation interventions in healthcare decision-making: protocol for a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2013;3(5):e002970.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien K, Colquhoun H, Kastner M, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16(1):15.

Council of Academic Hospitals of Ontario (CAHO). Adopting Research To Improve Care (ARTIC). 2015. http://caho-hospitals.com/partnerships/adopting-research-to-improve-care-artic/. Accessed November 2015.

Sampson M, McGowan J, Cogo E, Grimshaw J, Moher D, Lefebvre C. An evidence-based practice guideline for the peer review of electronic search strategies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(9):944–52.

Arbesman M, Mosley LJ. Systematic review of occupation- and activity-based health management and maintenance interventions for community-dwelling older adults. Am J Occup Ther. 2012;66(3):277–83.

Benson G. Review: psychoeducational programmes reduce long term mortality and recurrence of myocardial infarction in cardiac patients. Evid Based Nurs. 2000;3(3):80.

Chien AT, Walters AE, Chin MH. Community health center quality improvement: a systematic review and future directions for research. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2007;1(1):105–16.

Czubak R, Tucker J, Zarowitz B. Optimizing drug prescribing in managed care populations. Dis Manag Health Outcomes. 2004;12(3):147–67.

Eakin EG, Bull SS, Glasgow RE, Mason M. Reaching those most in need: a review of diabetes self-management interventions in disadvantaged populations. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2002;18(1):26–35.

Gilbert M, Staley C, Lydall-Smith S, Castle D. Use of collaboration to improve outcomes in chronic disease. Dis Manag Health Outcomes. 2008;16(6):381–90.

Peek ME, Cargill A, Huang ES. Diabetes health disparities: a systematic review of health care interventions. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(5 Suppl):101s–56.

Scisney-Matlock M, Bosworth HB, Giger JN, Strickland OL, Harrison RV, Coverson D, et al. Strategies for implementing and sustaining therapeutic lifestyle changes as part of hypertension management in African Americans. Postgrad Med. 2009;121(3):147–59.

Gaikwad R, Warren J. The role of home-based information and communications technology interventions in chronic disease management: a systematic literature review. Health Informatics J. 2009;15(2):122–46.

Jacobs-van der Bruggen MA, van Baal PH, Hoogenveen RT, Feenstra TL, Briggs AH, Lawson K, et al. Cost-effectiveness of lifestyle modification in diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(8):1453–8.

Moullec G, Laurin C, Lavoie KL, Ninot G. Effects of pulmonary rehabilitation on quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2011;17(2):62–71.

Norris SL, Engelgau MM, Narayan KM. Effectiveness of self-management training in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(3):561–87.

Smith SM, Allwright S, O’Dowd T. Does sharing care across the primary-specialty interface improve outcomes in chronic disease? A systematic review. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(4):213–24.

Yu CH, Bahniwal R, Laupacis A, Leung E, Orr MS, Straus SE. Systematic review and evaluation of web-accessible tools for management of diabetes and related cardiovascular risk factors by patients and healthcare providers. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19(4):514–22.

Tricco AC, Ivers NM, Grimshaw JM, Moher D, Turner L, Galipeau J, et al. Effectiveness of quality improvement strategies on the management of diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9833):2252–61.

Pham MT, Rajic A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(4):371–85.

Klein KJ, Sorra JS. The challenge of innovation implementation. Acad Manage Rev. 1996;21(4):1055–80.

Feinberg J. Wordle. 2014. http://www.wordle.net/. Accessed November 2015.

Reichard P, Pihl M, Rosenqvist U, Sule J. Complications in IDDM are caused by elevated blood glucose level: the Stockholm Diabetes Intervention Study (SDIS) at 10-year follow up. Diabetologia. 1996;39(12):1483–8.

Moher D, Glasziou P, Chalmers I, Nasser M, Bossuyt PM, Korevaar DA, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste in biomedical research: who’s listening? Lancet. 2015;387(10027):1573-86 .

Glasziou P, Altman DG, Bossuyt P, Boutron I, Clarke M, Julious S, et al. Reducing waste from incomplete or unusable reports of biomedical research. Lancet. 2014;383(9913):267–76.

Al-Shahi Salman R, Beller E, Kagan J, Hemminki E, Phillips RS, Savulescu J, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste in biomedical research regulation and management. Lancet. 2014;383(9912):176–85.

Ioannidis JP, Greenland S, Hlatky MA, Khoury MJ, Macleod MR, Moher D, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste in research design, conduct, and analysis. Lancet. 2014;383(9912):166–75.

Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(1):13–24.

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687.

Acknowledgements

We thank Becky Skidmore for peer reviewing the literature search, as well as Susan Le and Inthuja Selvaratnam for formatting the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant number CRI 8836. ACT is funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research/Drug Safety and Effectiveness Network (CIHR/DSEN) New Investigator Award in Knowledge Synthesis. JMG is funded by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Health Knowledge Transfer and Uptake. SES is funded by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Translation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

SES is an associate editor at Implementation Science but was not involved with the peer review process or decision for publication. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ACT conceived the study, designed the study, helped obtain funding for the study, screened citations and full-text articles, abstracted data, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript. HMA coordinated the review, screened citations and full-text articles, abstracted data, cleaned the data, analysed the data, interpreted the results, and edited the manuscript. EC (who also helped coordinate the study) and MK screened citations and full-text articles, abstracted data, and edited the manuscript. RC and HM screened citations and full-text articles, abstracted data, cleaned the data, and edited the manuscript. RC, HMA, and EC helped code the data for analysis. LP developed the literature search, executed the literature search, and screened citations and full-text articles. KAM and JMG helped conceive the study, helped obtain funding for the study, provided methodological insight during the study conduct, and edited the manuscript. SES conceived the study, designed the study, obtained the funding, interpreted the results, and helped write the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

KT Sustainability Chronic Conditions of Interest. (PDF 77 kb)

Additional file 2:

Taxonomy of Quality Improvement (QI) Strategies. (PDF 133 kb)

Additional file 3:

Included Studies. (PDF 160 kb)

Additional file 4:

Study Characteristics. (PDF 136 kb)

Additional file 5:

Patient Characteristics. (PDF 200 kb)

Additional file 6:

KT Interventions. (PDF 181 kb)

Additional file 7:

Specific intervention details from included studies. (PDF 776 kb)

Additional file 8:

Outcomes. (PDF 115 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tricco, A.C., Ashoor, H.M., Cardoso, R. et al. Sustainability of knowledge translation interventions in healthcare decision-making: a scoping review. Implementation Sci 11, 55 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0421-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0421-7