Abstract

Background

Stroke is the fifth leading cause of death and the leading cause of long-term disability in the USA, costing $40.2 billion in direct and indirect costs. Globally, stroke is the second leading cause of death and has a higher prevalence in lower- and middle-income countries compared to high-income countries.

The role of the spleen in stroke has been studied in rodent models of stroke and is seen as a major contributor to increased secondary neural injury after stroke. Splenectomy 2 weeks prior to ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke in mice and rats shows decreased infarct volumes. Additionally, the spleen decreases in size following stroke in rodents. Pro-inflammatory mediators are also increased in the spleen and subsequently the brain after stroke. These data in preclinical models of stroke have led stroke neurologists to look at the splenic response in stroke subjects. The outcomes of these studies suggest the spleen is responding in a similar manner in stroke subjects as it is in animal models of stroke.

Conclusion

Animal models demonstrating the detrimental role of the spleen in stroke are providing strong evidence of how the spleen is responding during stroke in human subjects. This indicates treatments targeting the splenic immune response in animals could provide useful targets and treatments for stroke subjects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

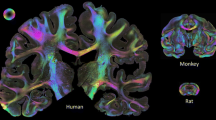

Stroke is the leading cause of disability and the fifth leading cause of death in the USA. Each year, 42.4 million strokes occur globally. The most common type is ischemic stroke resulting from a clot occluding a cerebral vessel [1]. While advancements have been made in treating the clot and restoring blood flow to the brain, there are still many factors that influence infarct size and the resulting disability. The immune system has been shown to play a detrimental role after stroke [2,3,4]. The spleen is a storage site for immune cells [5] and has been shown in animal models to play a role in increasing neural injury after experimental stroke [6,7,8,9,10]. This review will examine the spleen’s role in animal models of stroke and how these studies have translated into examining the spleens in stroke subjects.

Stroke statistics

Stroke is the fifth leading cause of death in the USA and second leading cause of death around the world. In the USA, 795,000 strokes occur annually resulting in the largest cause of long-term disability and costing $40.1 billion in direct and indirect costs. Globally 42.4 million strokes occur each year, with high-income countries seeing a decrease in the incidence of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke compared to low and middle income countries. Of the two main stroke subtypes, ischemic and hemorrhagic, ischemic strokes account for 87% of strokes while hemorrhagic strokes make up 13%. There are racial differences in stroke risks and outcomes. American Indian/Alaska Natives and non-Hispanic blacks have higher stroke prevalence compared to non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, and Asians/Pacific Islanders (~ 4.5 vs. ~ 2%, respectively). Additionally there are differences between men and women with regards to stroke risk, incidence, and outcomes. Overall women have a higher lifetime risk of stroke than men, and 55,000 more women than men experience a stroke each year. Men are at a slightly higher risk for stroke in younger and middle-aged groups but women have a much greater risk for stroke later in life and are more likely to die from a stroke. Women accounted for 58% of stroke deaths in the USA in 2015 [1].

The spleen

The spleen is a secondary immune organ that is part of the immune system. The spleen acts as a filter for the blood to remove any dying red blood cells, antibody coated cells, and bacterial pathogens. Additionally, the spleen serves as a communication hub for various immune cells to interact with each other, including T cells, B cells, macrophages/monocytes, and dendritic cells to initiate adaptive immune responses. The spleen is divided between the red and white pulp. The red pulp contains macrophages that filter the blood as it passes through the spleen and antibody producing B cells that allow for rapid delivery of antibodies into circulation. The white pulp has concentrated areas of lymphocytes. The close proximity of these cells allows for easy interaction of T cells and B cells to mount adaptive responses and allows macrophages and dendritic cells easy access to lymphocytes. T cells are concentrated around arterioles and make up periarteriolar lymphoid sheaths. This allows T cells to be in close proximity to the blood supply that allows dendritic cells easy access to naïve T cells, which once activated leave the spleen. B cells are organized to form B cell follicles. B cell follicles are where B cell responses are honed with isotype switching and increasing antigen specificity. These processes require T cells. The highly specific structure of the spleen allows for all these cells to be in close proximity to each other [5].

Peripheral immune response to stroke

Numerous studies have demonstrated the role the immune system plays in increasing neural injury follow stroke. Mice lacking lymphocytes, both Rag−/− [2] and SCID mice [3], have decreased infract volumes compared to wild type mice following middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). An additional study showed peripheral immune cells in the stroked brain hours to days after the initial insult [4]. The spleen, which is a reservoir of immune cells, is of interest in secondary neural injury following stroke. Splenocytes have been found in the brain in only the injured hemisphere at 48 and 96 h following MCAO [11], a rodent model of stroke.

Splenic response to ischemia/reperfusion injuries

The spleen’s involvement is well documented to enhance inflammation in ischemia/reperfusion (IR) injuries to various organs. The liver was the first organ where splenectomy was shown to decrease injury from the IR and blunt the inflammatory response triggered by IR [12]. Splenectomy also protected the intestines [13] and the kidneys [14] from IR injury. The injury in all three organs is believed to be mediated by monocytes in the spleen that activate Kupffer cells in the liver. Removing the spleen and splenic monocytes prevents activation of Kupffer cells, resulting in less inflammation and a reduction in tissue damage, as does blocking Kupffer cell activation with gadolinium chloride. Splenic monocytes were also found to play a detrimental role following IR injury to the heart, since splenectomy was protective against IR injury in that organ [15].

Splenic response to stroke in rodents

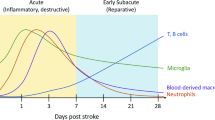

Rodent spleens show a decrease in size after MCAO that appears to be catecholamine (CA)-mediated, but the reason for the change in spleen size after stroke varies between rats and mice. The splenic capsule of rat spleens expresses α1 adrenergic receptors that cause splenic contraction when activated [16]. Following permanent MCAO (pMCAO) in rats, circulating CAs cause a transient decrease in spleen size. While the spleen is highly innervated by sympathetic neural networks [17], denervation of the spleen prior to pMCAO did not prevent the spleen from contracting. However, blocking the α1 receptors with prazosin or carvedilol did block splenic contraction, whereas propranolol did not block contraction. Carvedilol also decreased infarct size [18]. Additionally, rat spleens demonstrated a transient decrease in size with the smallest size detected 48 h after pMCAO but a return to pre-stroke size by 72 h. During splenic contraction, splenocytes were released into the systemic circulation and traveled to the injured hemisphere of the brain. Innate splenocytes were found in the brain as early as 48 h, whereas adaptive splenocytes appeared at 96 h following pMCAO [11]. Generally, there was a negative correlation between spleen size and infarct volume [19]. Mice also exhibit a significant loss of cells and decreased spleen size following transient MCAO (tMCAO) that persists over time. This loss of splenocytes appears to be due to apoptosis of the splenocytes and loss of splenic structures, including B cell follicles. At 96 h after tMCAO, mice show a 90% reduction in splenocyte numbers compared to sham-operated mice. The greatest effect is on B cells, while T cell numbers appear to increase, specifically regulatory T cells [20]. An additional study showed that mouse spleens continued to decrease in size through day 7 post-tMCAO [21]. Mouse spleens are extensively innervated like rat spleens and also appear to highly express α1-adenergic receptors on the splenic capsule [22]. Unlike rats, mouse spleens do not contract, but the catecholaminergic innervation of immune cells appears to negatively impact some of these cells resulting in cell death.

In addition to the cellular responses in the spleen to stroke, there are also changes in cytokine and chemokine responses. In mouse spleens, there is an increase by 22 h after tMCAO in TNFα, interferon gamma (IFNγ), IL-6, MCP-1, and IL-2, all of which are pro-inflammatory mediators [23]. One pro-inflammatory cytokine of interest is IFNγ, since IFNγ−/− mice have smaller infarcts than wild-type mice [2]. In rats, splenic increases in IFNγ production as early as 24 h after pMCAO results in a delayed increase in IFNγ in the injured brain at 72 h. This early transient increase in IFNγ in the spleen is likely connected to the later increase in IFNγ in the brain, since splenectomy decreases the IFNγ expression in the brain [7]. Similar results were found in mice after tMCAO such that IFNγ was increased at 72 h in the brain and splenectomy significantly decreased IFNγ levels within the brain [8]. IFNγ also initiated the expression of the pro-inflammatory chemokine interferon inducible protein 10 (IP-10) in both the spleen and the brain after pMCAO. Splenectomy prior to pMCAO or treatment with an IFNγ neutralizing antibody after pMCAO reduced IP-10 levels in the brain and subsequent T cell recruitment to the brain [24].

Splenectomy in rodent models of stroke

Splenectomy carried out 2 weeks prior to initiating MCAO in mice or intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) in rats afforded protection in the brain. Initial studies found that splenectomy 2 weeks prior to pMCAO in rats decreased infarct volume by 80% and reduced immune cell infiltration into the brain [6]. Subsequently, a study found that splenectomy significantly decreased edema and water content in a rat model of ICH [10]. In mice, splenectomy prior to tMCAO was first carried out only in males and showed a significant reduction in infarct volume [8]. Additional studies in mice again showed that male mice were protected from stroke after splenectomy but that the protective effect was lost in female mice [9]. It was found that female mice had more regulatory lymphocytes in their spleens than male mice and the loss of these regulatory cells in female mice resulted in the loss of protection from stroke [9, 25]. Additionally, male mice had more activated T cells in their spleens after tMCAO compared to female mice [26]. A study in older mice demonstrated that splenectomy decreased infarct volume in older male mice, improved behavioral outcomes, and decreased immune cell infiltration into the brain [27]. A more recent study in rats showed splenectomy immediately following tMCAO significantly decreased infarct volume and improved behavioral deficits [28]. Other studies have concluded that splenectomy does not protect mice or rats from tMCAO although it was noted that the MCAO surgery was performed immediately after the splenectomy surgery [29, 30]. Splenectomy is a major surgery, and the body compensates for the loss of the spleen by transiently increasing circulating immune cells over the course of a week (data not published). Additionally, the body is also responding to the surgical insult of removing the spleen. Therefore, splenectomy should be performed 2 weeks prior to the MCAO surgery to allow the animal’s body to recovery from the splenectomy surgery. Another study investigating the role the spleen plays in enhancing neural injury used splenic irradiation in place of splenectomy as a noninvasive way to blunt the splenic responses. Rats received targeted splenic irradiation 3 or 4 h after tMCAO, and this significantly decreased infarct size but did not damage the spleen or surrounding organs or lead to immune suppression or increased infections [31].

Neuroprotective therapies also involve the spleen

Various therapies that protect the brain after stroke interact with the spleen. Some therapies interact with splenocytes or travel to the spleen. Others prevent the decrease in spleen size seen after tMCAO. Stem cells from various sources protect the brain after stroke and also travel to the spleen. Human umbilical cord blood (HUCB) cells reduce infarct after pMCAO in rats and restore spleen size at 48 h post-pMCAO [19, 32]. HUCB cells protected gray and white matter [33] in rats when administered 24 h after MCAO and reduced behavioral deficits. Additionally, HUCB cells saved the spleen weight [19], were found in the injured brain and the spleen [34], and allowed splenocytes to respond normally when stimulated with concanavalin A when the cells were administered intravenously [19]. Studies with human bone marrow stem cells (hBMSC) found these cells decreased infarct volume in rats and migrated to the spleen when administered intravenously [35]. The previous two examples were immune cell derived stem cells that migrated to the spleen after stroke to help reduce the infarct. A study in a model of ICH used neural stem cells and found these cells were more effective at reducing edema and brain water content after ICH when injected intravenously compared to direct injection into the brain. In addition, it was reported that neural stem cells in the spleen were in direct contact with the splenic monocytes. The spleen was also found to be necessary for neural stem cells to provide protection since protection was lost when the rats underwent splenectomy 2 weeks prior to ICH and neural stem cell administration [10].

Other therapies save spleen size and reduce infarct. One such therapy is treatment with recombinant T cell receptor ligands (RTL), which are partial major histocompatibility complex II molecules covalently bound to myelin peptides. After tMCAO in mice, RTL administration reduced infarct size by 50%, reduced the recruitment of immune cells to the brain, and prevented the reduction in spleen size seen in mice. This effect was only seen in mice given the RTL with a myelin peptide [36,37,38]. Another therapy, carvedilol—a pan adrenergic blocker, also reduced infarct size in rats with pMCAO and prevented splenic contraction [18].

The splenic response in stroke subjects

The initial pilot study in stroke subjects used ultrasound to evaluate at the spleen size in 30 stroke subjects with ischemic stroke that were at the hospital within 6 h after onset of symptoms. This study found that the spleen size of subjects initially decreased and if the subject continued to decline on the NIH Stroke Severity (NIHSS) score then their spleens continued to decrease in size. However, in some subjects, the NIHSS score decreased as the spleen size began to increase until it surpassed the initial ultrasound reading [39]. Another study used a retrospective approach looking at CT scans of 82 stroke subject spleens. This study included both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke subjects. The study concluded that the spleen undergoes a biphasic response to stroke characterized by a transient decrease in spleen size reaching its smallest size at 48 h post stroke. There were gender differences in spleen size after stroke, but no difference between stroke subtypes [40]. A larger study derived from the initial pilot study was expanded to include both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke subjects and a cohort of healthy control subjects to establish a baseline spleen size. The 158 healthy controls underwent an ultrasound of their spleen for 5 consecutive days. Based on these data, significant differences were found between gender, height, weight, and body surface area (BSA). To evaluate if there was any splenic contraction in stroke subjects, their spleen volumes were compared to healthy controls based on gender and BSA. A spleen was considered to be contracted if it was 20 cm3 smaller than their gender and BSA matched healthy controls. This study found that 40.5% of stroke subjects had a contracted spleen. Individuals were at a significantly higher risk for splenic contraction if they were African American, over the age of 75, had a more severe stroke, or had a history of stroke. There were no differences between genders, types of stroke, or admission NIHSS score. Plasma cytokines were also analyzed in a subset of subjects and individuals with splenic contraction had significantly elevated levels of IFNγ, IL-6, IL-12, and IL-10 [41]. In an expansion of the previous study, a retrospective looked at only ischemic stroke subjects to determine if there was an association between splenic contraction and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). SIRS is an inflammatory process that is detrimental to stroke recovery and independent of an infection. SIRS was considered present if two of the following were present: elevated heart rate, changes in body temperature, elevated respiratory rate, or changes in white blood cell counts. Non-infectious SIRS is associated with longer hospital stays and poorer functional outcomes. Splenic contraction was not associated with the development of early SIRS. African Americans and individuals aged over 75 were at a significantly higher risk of splenic contraction following a stroke. African Americans had a 92.3% chance of developing SIRS within the first 48 h of stroke if they had splenic contraction compared to a 62.5% chance of developing SIRS with splenic contraction in other races. In individuals over the age of 75, there was a negative correlation with splenic contraction and the development of SIRS at 72 h post stroke, while there was no significant connection between splenic contraction and SIRS in the younger age groups. In stroke subjects over the age of 75, the development of SIRS was higher in individuals without splenic contraction compared to those subjects with splenic contraction (71.4 vs. 46.1, respectively) [42].

Conclusion

The importance of the spleen in contributing to increased neural damage following a stroke is becoming increasing evident in stroke subjects. Changes that were seen in preclinical models of stroke in rodents are similar to the data being collected in stroke subjects. While there are limitations to all animal models of human diseases, the role of the spleen in stroke from preclinical models so far has provided some insight into the disease process of human stroke. Not only has the spleen been shown to decrease in size following stroke there is also an increase in IFNγ in subjects with splenic contraction (Table 1). This could lead to biomarkers for stroke outcomes or targets to treat stroke in certain subsets of subjects (Fig. 1).

The splenic immune response to stroke. The spleen responds to stroke in mice, rats, and humans after cerebral ischemia. In experimental models with mice and rats using MCAO as a model for ischemic stroke, the spleen decreases in size. In mice, this is due to splenic apoptosis and loss of cells. In rats, the spleen contracts and releases immune cells into circulation. In stroke subjects, the spleen contracts in some individuals. The spleen’s involvement in post-stroke events contributes to secondary neural injury and worse outcomes. When the spleen is targeted in animal models of stroke, using splenectomy, this decreases neural injury in mice and rats. Can targeting the spleen in humans improve clinical outcomes by decreasing neural injury? * indicates splenectomy 2 weeks prior to MCAO. # splenectomy only works in male mice

Abbreviations

- BSA:

-

Body surface area

- CA:

-

Catecholamine

- hBMSC:

-

Human bone marrow stem cells

- HUCB:

-

Human umbilical cord blood

- ICH:

-

Intracerebral hemorrhage

- IFNγ:

-

Interferon gamma

- IP-10:

-

Interferon inducible protein 10

- IR:

-

Ischemia/reperfusion

- MCAO:

-

Middle cerebral artery occlusion

- NIHSS:

-

NIH stroke severity

- NSC:

-

Neural stem cells

- pMCAO:

-

Permanent MCAO

- RTL:

-

Recombinant T cell receptor ligands

- SIRS:

-

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome

- tMCAO:

-

Transient MCAO

References

Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(12):e67–e492.

Yilmaz G, et al. Role of T lymphocytes and interferon-gamma in ischemic stroke. Circulation. 2006;113(17):2105–12.

Hurn PD, et al. T- and B-cell-deficient mice with experimental stroke have reduced lesion size and inflammation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27(11):1798–805.

Stevens SL, et al. The use of flow cytometry to evaluate temporal changes in inflammatory cells following focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Brain Res. 2002;932(1–2):110–9.

Mebius RE, Kraal G. Structure and function of the spleen. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(8):606–16.

Ajmo CT Jr, et al. The spleen contributes to stroke-induced neurodegeneration. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:2227–34.

Seifert HA, et al. The spleen contributes to stroke induced neurodegeneration through interferon gamma signaling. Metab Brain Dis. 2012;27(2):131–41.

Jin R, et al. Simvastatin attenuates stroke-induced splenic atrophy and lung susceptibility to spontaneous bacterial infection in mice. Stroke. 2013;44(4):1135–43.

Dotson AL, et al. Splenectomy reduces infarct volume and neuroinflammation in male but not female mice in experimental stroke. J Neuroimmunol. 2015;278:289–98.

Lee ST, et al. Anti-inflammatory mechanism of intravascular neural stem cell transplantation in haemorrhagic stroke. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 3):616–29.

Seifert HA, et al. A transient decrease in spleen size following stroke corresponds to splenocyte release into systemic circulation. J Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 2012;7(4):1017–24.

Okuaki Y, et al. Splenectomy-reduced hepatic injury induced by ischemia/reperfusion in the rat. Liver. 1996;16(3):188–94.

Savas MC, et al. Splenectomy attenuates intestinal ischemia-reperfusion-induced acute lung injury. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38(10):1465–70.

Jiang H, et al. Splenectomy ameliorates acute multiple organ damage induced by liver warm ischemia reperfusion in rats. Surgery. 2007;141(1):32–40.

Leuschner F, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition prevents the release of monocytes from their splenic reservoir in mice with myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2010;107(11):1364–73.

Aboud R, Shafii M, Docherty JR. Investigation of the subtypes of alpha 1-adrenoceptor mediating contractions of rat aorta, vas deferens and spleen. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;109(1):80–7.

Felten DL, et al. Noradrenergic and peptidergic innervation of lymphoid tissue. J Immunol. 1985;135(2 Suppl):755s–65s.

Ajmo CT Jr, et al. Blockade of adrenoreceptors inhibits the splenic response to stroke. Exp Neurol. 2009;218(1):47–55.

Vendrame M, et al. Infusion of human umbilical cord blood cells in a rat model of stroke dose-dependently rescues behavioral deficits and reduces infarct volume. Stroke. 2004;35(10):2390–5.

Offner H, et al. Splenic atrophy in experimental stroke is accompanied by increased regulatory T cells and circulating macrophages. J Immunol. 2006;176(11):6523–31.

Bao Y, et al. A role for spleen monocytes in post-ischemic brain inflammation and injury. J Neuroinflammation. 2010;7:92.

Grisanti LA, Perez DM, Porter JE. Modulation of immune cell function by alpha(1)-adrenergic receptor activation. Curr Top Membr. 2011;67:113–38.

Offner H, et al. Experimental stroke induces massive, rapid activation of the peripheral immune system. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26(5):654–65.

Seifert HA, et al. Pro-inflammatory interferon gamma signaling is directly associated with stroke induced neurodegeneration. J NeuroImmune Pharmacol. 2014;9(5):679–89.

Seifert HA, et al. Sex differences in regulatory cells in experimental stroke. Cell Immunol. 2017;318:49–54.

Banerjee A, et al. Phenotypic changes in immune cell subsets reflect increased infarct volume in male vs. female mice. Transl Stroke Res. 2013;4(5):554–63.

Chauhan A, et al. Splenectomy protects aged mice from injury after experimental stroke. Neurobiol Aging. 2018;61:102–11.

Belinga VF, et al. Splenectomy following MCAO inhibits the TLR4-NF-kappaB signaling pathway and protects the brain from neurodegeneration in rats. J Neuroimmunol. 2016;293:105–13.

Kim E, et al. Role of spleen-derived monocytes/macrophages in acute ischemic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34(8):1411–9.

Zierath D, et al. Splenectomy does not improve long-term outcome after stroke. Stroke. 2017;48(2):497–500.

Ostrowski R, et al. Acute splenic irradiation reduces brain injury in the rat focal ischemic stroke model. Transl Stroke Res. 2012;3:473–81.

Vendrame M, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of human cord blood cells in a rat model of stroke. Stem Cells Dev. 2005;14:595–604.

Rowe DD, et al. Cord blood administration induces oligodendrocyte survival through alterations in gene expression. Brain Res. 2010;1366:172–88.

Vendrame M, et al. Cord blood rescues stroke-induced changes in splenocyte phenotype and function. Exp Neurol. 2006;199(1):191–200.

Acosta SA, et al. Intravenous bone marrow stem cell grafts preferentially migrate to spleen and abrogate chronic inflammation in stroke. Stroke. 2015;46(9):2616–27.

Subramanian S, et al. Recombinant T cell receptor ligand treats experimental stroke. Stroke. 2009;40(7):2539–45.

Dziennis S, et al. Therapy with recombinant T-cell receptor ligand reduces infarct size and infiltrating inflammatory cells in brain after middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice. Metab Brain Dis. 2011;26(2):123–33.

Akiyoshi K, et al. Recombinant T cell receptor ligands improve outcome after experimental cerebral ischemia. Transl Stroke Res. 2011;2(3):404–10.

Sahota P, et al. Changes in spleen size in patients with acute ischemic stroke: a pilot observational study. Int J Stroke. 2013;8(2):60–7.

Chiu NL, et al. The volume of the spleen and its correlates after acute stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25(12):2958–61.

Vahidy FS, et al. Acute splenic responses in patients with ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2016;36(6):1012–21.

Zha A, et al. Association between splenic contraction and the systemic inflammatory response after acute ischemic stroke varies with age and race. Transl Stroke Res. 2017;27:1–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Gail Kent for assistance with manuscript preparation and submission.

Funding

This work was supported by American Heart Association grants 17GRNT33220001 and NIH/NINDS R01NS076013, and R01NS080890 (Halina Offner). This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Portland Health Care Center in Portland, OR. The contents do not represent the views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HS and HO wrote and edited the review. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

HO and OHSU have a significant financial interest in Artielle ImmunoTherapeutics, Inc., a company that may have a commercial interest in the results of the research and technology involving RTL. This potential conflict of interest has been reviewed and managed by the OHSU and VA Portland Health Care System Conflict of Interest in Research Committees. HS declares no conflicts of interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Seifert, H.A., Offner, H. The splenic response to stroke: from rodents to stroke subjects. J Neuroinflammation 15, 195 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-018-1239-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-018-1239-9