Abstract

Background

The ability of acute care providers to cope with the influx of frail older patients is increasingly stressed, and changes need to be made to improve care provided to older adults. Our purpose was to conduct a scoping review to map and synthesize the literature addressing frailty in the acute care setting in order to understand how to tackle this challenge. We also aimed to highlight the current gaps in frailty research.

Methods

This scoping review included original research articles with acutely-ill Emergency Medical Services (EMS) or hospitalized older patients who were identified as frail by the authors. We searched Medline, CINAHL, Embase, PsycINFO, Eric, and Cochrane from January 2000 to September 2015.

Results

Our database search initially resulted in 8658 articles and 617 were eligible. In 67% of the articles the authors identified their participants as frail but did not report on how they measured frailty. Among the 204 articles that did measure frailty, the most common disciplines were geriatrics (14%), emergency department (14%), and general medicine (11%). In total, 89 measures were used. This included 13 established tools, used in 51% of the articles, and 35 non-frailty tools, used in 24% of the articles. The most commonly used tools were the Clinical Frailty Scale, the Frailty Index, and the Frailty Phenotype (12% each). Most often (44%) researchers used frailty tools to predict adverse health outcomes. In 74% of the cases frailty predicted the outcome examined, typically mortality and length of stay.

Conclusions

Most studies (83%) were conducted in non-geriatric disciplines and two thirds of the articles identified participants as frail without measuring frailty. There was great variability in tools used and more recently published studies were more likely to use established frailty tools. Overall, frailty appears to be a good predictor of adverse health outcomes. For frailty to be implemented in clinical practice frailty tools should help formulate the care plan and improve shared decision making. How this will happen has yet to be determined.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Providing health care to an aging population presents both challenges and opportunities. Perhaps most important is how we understand and respond to frailty. The concept of frailty was introduced in the literature of geriatric medicine and gerontology almost two decades ago to better understand the heterogeneous health status of the older persons. Since then, this area of research has grown exponentially. Although contested, frailty is increasingly understood conceptually as the increased vulnerability to adverse outcomes among people of the same chronological age [1]. Frail individuals can be thought of as complex systems close to failure, vulnerable to further physiological and psychological stressors caused by both intrinsic and environmental factors. Adding one more stressor to such a system, even a stress as minor as one more drug, may lead to a cascade effect. Not all older adults are frail. Among community-dwelling people over the age of 50 years approximately 20% are frail [2, 3]. Even so, levels of frailty are higher among those seen in clinical settings [4].

Frail patients have higher rates of adverse outcomes, and thus require adaptations of care, personalization of interventions, and modifications of standard protocols [1, 5]. As such, identifying frailty early in clinical care is vital [6,7,8]. Given its pervasive impact on health and the outcomes of health care, it has been proposed that frailty be considered routinely when treating the older patient [6]. To do so we need validated tools with sound measurement properties. With various instruments having been developed, there is heated debate over how to best operationally define frailty and which tools can feasibly be used across care settings [9, 10]. A 2007 systematic review identified 27 articles that included a frailty measure in older adults [11]. Since then many more tools have been developed and multiple systematic reviews have been published on them mostly focusing on community settings [2, 9, 12,13,14,15]. In a systematic review by de Vries and colleagues in 2011, 20 frailty tools were identified and the authors concluded that at that point the Frailty Index seemed to be the most suitable instrument to measure frailty [9]. A year later Pailoux and colleagues found that 10 instruments have been used for screening for frailty in primary health care [13]. Choosing among the many options available can be confusing for health care professionals.

Older frail adults are more vulnerable to health crises. They are more likely to be hospitalized or to need critical care, use emergency medical services, and have a longer in-hospital length of stay [16, 17]. Many critical, life altering decisions are made in the acute care setting during these crises. There are indications that frailty identification and management will improve clinical decision making and health outcomes within acute care. For example, frailty assessment by EMS and ED providers could facilitate referral or transport to the most appropriate service and could assist with identifying patients who will not benefit from aggressive medical treatments. Even so, before translational research programs focus on how frailty measures will be incorporated into every day care in the acute care setting and how they will benefit clinical decisions, we need to agree on how frailty will be measured and managed in this setting. Currently, no systematic reviews have been conducted with a general focus on EMS and in-hospital settings. Given the growing numbers of frail patients and the greater use of frailty tools within clinical settings, we conducted a scoping review to map and synthesize the literature around frailty in the acute care setting. This included identifying and documenting the nature and extent of research evidence related to frailty measurement and management in EMS and in-hospital settings.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

This scoping review included original research articles published since January 2000. Two of the most commonly used frailty definitions, the Frailty Phenotype and the Frailty Index, were developed in 2001 which is when the literature around frailty started increasing. In order for the articles to be included, the following criteria had to be met: at least 50% of the participants were acutely-ill EMS (paramedic services) or hospitalized patients, at least one patient was aged 65 or older, and at least one participant was identified as frail by the authors (with or without reporting on measuring frailty). We did not limit articles by language or study design. Articles were excluded if they focused on care delivery outside of hospital or on hospitalized patients who were not acutely ill (for example, dialysis and chemotherapy outpatients, inpatients on rehabilitation wards or doing elective surgeries, and subacute patients).

We searched a wide range of academic literature databases including Medline, CINAHL, Embase, PsycINFO, Eric, and Cochrane up to September 2015. The search terms we used were all words that are used interchangeably as descriptors of “frailty”, “aging”, “pre-hospital”, and “acute care” in Medical Subject Headings, text, and keywords (Additional file 1: Table S1). Additional articles were identified by manually searching the reference lists of systematic reviews focusing on frailty. We contacted authors when we needed additional information about the eligibility of an article. Two members of the review team independently screened the title and abstracts and then the full text of the articles that met the inclusion criteria. Disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by a third reviewer. We included reviewers who were fluent in all relevant languages.

Data analysis

The database search results were uploaded into Refworks where duplicates were removed. DistillerSR software was used to manage the screening process. An excel data extraction form was developed to guide collection of information relevant to the review. The following descriptive data was extracted from each article that satisfied the inclusion criteria: year of publication, language, and country. For the articles that included a frailty measure we extracted additional descriptive data: number of participants, participant age, participant sex, study setting (medical discipline) and design, when and how frailty was measured, who completed the evaluation, the stated purpose for measuring frailty, the prevalence of frailty, and any adverse outcome measure examined in association with frailty. Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS 21.

Results

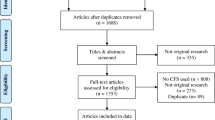

The initial database search resulted in 8658 articles. After duplicates were removed (n = 2621), we screened the title and abstract of 6037 articles and excluded 2797 from additional screening. Full text was obtained for 3240 articles, 589 of which remained after screening. We also hand-searched the reference list of other relevant papers, including systematic reviews focusing on frailty; 28 additional articles were added to bring the final number of included articles to 617 (Fig. 1; Additional file 1: Table S2).

In 67% of the articles (n = 413/617) the authors identified their participants as frail but did not provide an operational definition of frailty or refer to use of a frailty measurement tool (Fig. 1). Table 1 shows the descriptive characteristics of the articles that measured frailty (33%, n = 204) [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,216,217,218,219,220,221], whereas Additional file 1: Table S3 shows the descriptive characteristics of the articles that did not include a frailty measurement.

Most of the articles (n = 442/617) reported on studies conducted in a single medical discipline. The most common single disciplines were geriatrics, emergency department, general medicine, cardiology, and orthopedics. A total of 49 studies were conducted in two disciplines, with general medicine and surgery (n = 25) being the most common combination followed by geriatric medicine and general medicine (n = 15). In 29 articles, the authors specified that participants were recruited from at least 3 disciplines and in 97 articles the authors did not specify from which discipline the hospitalized patients were recruited (Additional file 1: Figure S1).

The number of articles increased over time with more articles published in the last 5 years of our review; 52% (n = 318/617) were published between 2011 and 2015, with less than 20% (n = 121) published in 2005 or earlier. The increase in publications was even more striking among articles which measured frailty: 69% (n = 141/204) of articles published in 2011–2015, up from only 12% (n = 24) of those published in 2000–2005 (Table 1; Additional file 1: Figure S2A). Almost all included articles were written in English (94%, n = 583/617). The remaining articles were written in French (n = 11), Italian (n = 7) [93, 102], Spanish (n = 7), Dutch (n = 4), Portuguese (n = 3) [51, 141], and German (n = 2). Among the 34 non-English articles, only 4 measured frailty. A variety of countries were represented, with the majority, 59%, of the published studies conducted in Europe (n = 361/617), 25% in North America (n = 157), and 8% in Australia or New Zealand (n = 48). Among the 204 articles that measured frailty, 48% reported on studies conducted in Europe (n = 98) and 36% on studies conducted in North America (n = 73) (Table 1).

Based on the descriptive characteristic data extracted for the 204 articles that measured frailty, the number of participants per study ranged from 9 to 971,434 with a median of 206 participants (interquartile range 100.5–460). The mean age of participants ranged from 47.1 to 91.6 years with a median of 78.9 years (interquartile range 74–82.9); for 9 articles [26, 60, 111, 128, 136,137,138, 169, 211], the mean age was less than 65 years. Among the articles that reported the number of female and male participants (n = 187/204), the median was 54% females (interquartile range 43.5–63%) (Table 1). The majority of articles were observational studies (n = 166/204) and 16% were experimental (n = 32; 26 were randomized controlled trials). In total, 3% of the studies were qualitative (n = 6) [27, 69, 88, 124, 145, 181]; 3 studies examined the involvement of hospitalized older people in decision making regarding their care (Fig. 2).

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of frailty measurement as reported in the included articles. In most cases, frailty was measured by either a health care professional (n = 80) or a researcher (n = 81) (Additional file 1: Figure S3). In geriatrics, oncology, surgery, and EMS disciplines, frailty assessments were done mostly by health care professionals, whereas in emergency department, general medicine, ICU, orthopedics, and cardiology it was more common that assessments were done by researchers (Additional file 1: Figure S3). Frailty was measured at hospital admission in almost half of the articles (n = 94), at discharge in 5% of the articles (n = 10), and was operationalized retrospectively through chart reviews or databases in 13% of the articles (n = 27). In cardiology, orthopedics, and EMS disciplines, more than one quarter of the articles operationalized frailty retrospectively (Table 2).

Overall, 89 measures were used 240 times in the 204 included articles. Most of the articles included only one frailty measure (n = 185), while 9 articles included 2 measures [45, 54, 70, 112, 163, 172, 183, 196, 212] and 10 articles included 3 or more measures (Table 2). Thirteen established tools, developed to measure frailty, were used in 51% of the cases (n = 123). Thirty-five non-frailty tools were used in 24% of the cases (n = 57). These were validated scales but not developed to identify frailty (e.g. short physical performance battery). In 23% of the cases (n = 56), ad hoc measures were used which were operational definitions developed for the purpose of that study (e.g. everyone who was older than 65 and had 2 or more chronic diseases was considered frail). Four articles used clinical judgment to define frailty. Established frailty tools were the most common type of measure across all disciplines, except the orthopedic discipline where non-frailty scales were more common (n = 10/18 articles) (Table 2). When the results were stratified by year of publication, we found that ad hoc measures of frailty (n = 15/24; 63%) were most commonly used in the oldest articles (those published between 2000 and 2005), whereas use of established frailty tools (n = 101/174; 58%) was most common in the most recent articles (published between 2011 and 2015), (Additional file 1: Figure S4). In articles reporting on studies conducted in USA, ad hoc measures were the most common (n = 26/62; 42%). In contrast, in the rest of the countries established frailty tools were the most common, with Canada (n = 17/18; 94%) and Australia/New Zealand (n = 14/18; 78%) having the highest proportion.

The Clinical Frailty Scale, the Frailty Index, and the Frailty Phenotype were the most common tools used to measure frailty (n = 28 each) (Additional file 1: Figure S5). The Clinical Frailty Scale was the most popular measure used in geriatric (n = 6/35; 17%) [34, 66, 94, 110, 185, 212] and ICU disciplines (n = 6/10; 60%) [103, 176, 190, 192, 196, 211] (Table 3), in Canada (n = 12/18; 67%) and the UK (n = 8/26; 31%) [103, 116, 139, 180, 188, 202, 207, 213], and in observational articles (n = 26/202; 13%). The Frailty Index was the most popular measure used in emergency departments (n = 7/33; 21%) [93, 106, 125, 131, 163, 165, 195] and orthopedics (n = 4/18; 22%) [126, 189, 219, 220] (Table 3), in Italy (n = 5/19; 26%) [93, 104, 106, 133] and Denmark (n = 3/8; 38%) [189, 219, 220], and in experimental articles (n = 6/32; 19%) [50, 62, 166, 189, 219, 220]. The Frailty Phenotype was the most popular measure used in cardiology (n = 6/24; 25%) [45, 89, 90, 112, 172, 208] and surgery (n = 2/10; 20%) [184, 221] (Table 3), and in Spain (n = 4/10; 40%) [90, 112, 172, 174] and Sweden (n = 2/6, 33%) [92, 119]. Among the 122 articles that reported the prevalence of frailty, the median prevalence was 49%. The highest prevalence was in orthopedics (69% median frailty prevalence) and the lowest in ICU (34% median frailty prevalence) (Table 2).

In almost half of the articles (n = 89, 44%), researchers used frailty for risk stratification purposes to examine whether frailty can predict adverse health outcomes (n = 89). In 41 articles (20%), frailty was used strictly as an inclusion criterion for patient recruitment. In 7 articles (4%), frailty was used solely as an outcome or in combination with risk stratification or inclusion criterion [52, 118, 119, 132, 138, 187, 216]. In the remaining articles (n = 67, 33%), frailty was only used as a descriptive of the sample (e.g. reporting only on the prevalence of frailty of the sample). Risk stratification was the most common reason for using the frailty tools across all disciplines, except in oncology where descriptive was the most common reason (Table 2). Stratified by year of publication (Fig. 3a), in the oldest articles (2000–2005) frailty tools were most commonly used as inclusion criterion (n = 16/24; 67%), while in the most recent articles (2011–2015) the most common use was risk stratification (n = 75/141; 53%); all 4 articles [118, 132, 138, 216] that used frailty solely as an outcome were published after 2010. In the included observational articles, risk stratification was the most common reason (n = 84/166; 51%) whereas in the experimental articles inclusion criterion was the most common (n = 16/32, 50%) (Fig. 3b). One of the experimental studies (prospective non-randomized trial) modified treatment plans based on frailty levels in cancer patients [52]. Three of the experimental studies (all randomized controlled trials) used frailty as an outcome measure [118, 119, 216]: two were published protocols (one of an exercise intervention and one of a combined exercise and nutrition intervention) and the other was a multi-professional team approach intervention creating a continuum of care for patients from the hospital emergency department to the older person’s own home (no significant change in frailty was found) [118, 216].

Proportion of articles based on the reason frailty measures were used in the articles. Stratified by (a). Year (b). Study design. 1Articles which only used frailty as a descriptive characteristic. For example, if an article used frailty both as an inclusion/exclusion criterion and a descriptive characteristic, it was only categorized as inclusion/exclusion criterion in our review. 2Inclusion/Exclusions criterion and outcome measure; risk stratification and outcome measure. 3Articles that examined the association of a frailty tool with a longitudinal adverse outcome

Among the 89 articles that used a frailty measure as a risk stratification tool, 115 measures were included; most often established frailty tools (n = 73, 64%), with the most common being the Frailty Index (n = 23, 20%), the CFS (n = 19, 17%), the Frailty Phenotype (n = 12, 10%), and the Edmonton frailty scale (n = 6, 5%) [71, 86, 121, 149, 178, 179]. Among these 89 risk stratification articles, 228 adverse outcomes were examined. The most frequent outcomes examined were mortality, in-hospital length of stay, institutionalization, and complications. Overall, in 169 cases (74%), frailty was predictive of an outcome (i.e. statistical significant association between frailty and the outcome measure), whereas in 59 cases it was not (26%). Frailty was predictive of mortality in 84% of the articles where this outcome was examined, in-hospital length of stay in 73%, institutionalization in 93%, and complications in 69% (Fig. 4). The highest rate for significant prediction of all outcomes combined was in EMS (n = 1/1, 100%) [159] and general medicine (n = 18/22, 82%) disciplines. The lowest rate was in oncology (n = 4/8, 50%) [49, 52, 169]. For mortality, the highest rate for significant prediction was in general medicine (n = 4/4, 100%) [99, 101, 116, 156] and the lowest in oncology (n = 1/2, 50%) [49] and cardiology (n = 7/10, 70%) [89, 121, 128, 172, 173, 208, 210]. When we stratified analysis by type of tool, the significant prediction rate was 74% (n = 122/164) for the established frailty tools, 84% for the ad-hoc tools (n = 16/19), 100% for clinical judgment (n = 2/2) [36, 111], and 67% for the non-frailty scales (n = 29/43). When we stratified by scale used, the predictive rate among the four most commonly used scales were 89% for the Frailty Index (n = 39/44 outcomes), 88% for the Edmonton frail scale (14/16 outcomes), 73% for the CFS (n = 35/48), and 53% for the Frailty Phenotype (n = 16/30) (Fig. 5).

Discussion

We identified and documented the nature and extent of research evidence related to frailty measurement and management in the pre-hospital and EMS acute care setting. We found that most articles were done in non-geriatric disciplines between 2011 and 2015 in North America or Europe. Two thirds of the articles identified participants as frail without measuring frailty, and as time passed, more frailty studies were conducted across all disciplines. Overall, 89 measures were used including 13 established tools and 35 non-frailty tools; more recent studies were more likely to use established frailty tools. We found that the most commonly used scales were the Clinical Frailty Scale, the Frailty Index, and the Frailty Phenotype. Most articles were observational and used frailty tools to predict adverse health outcomes, especially mortality and institutionalization. Overall, frailty seems to be a good predictor of adverse health outcomes; in 74% of the cases frailty was predictive. When we looked at specific scales, the Frailty Index and the Edmonton scale seemed to have the best predictive ability.

This scoping review has a number of limitations. Quality assessments or meta-analysis were not conducted, and the scope of the review was very broad; for example, if participants were called frail once in the discussion the article was included. This was an appropriate first step for the field of frailty within acute care. Now that we have identified specific areas with sufficient research evidence, the next step for the field is to answer more focused research questions, such as a meta-analysis on the ability of the frailty scales to predict mortality in acute care. Another limitation of our scoping review is that non-English articles may have been missed because the databases searched included mostly English journals. Also, we only included articles with acutely-ill inpatients, which means we have not gathered data on other articles that focused on frailty, for example, those in rehabilitation and dialysis units, and elective surgery. Finally, the grey literature was not reviewed.

Our scoping review includes articles published up to September 2015. More frailty papers have since been published. Due to the broad scope of our review and the pace of frailty research, it is not feasible to conduct a completely up to date review. We are confident that the main findings and gaps identified continue to be relevant. For example, three systematic reviews published in 2017 examined frailty in surgical patients and showed similarly to our study that the evidence about the ability of frailty tools to predict adverse health outcomes in surgical patients is limited and that even less studies have tested whether interventions can improve perioperative outcomes in surgical patients [222,223,224]. Another systematic review showed that frailty is common in patients admitted to ICU and is associated with higher hospital and long-term mortality [225]. A recent scoping review focused on frailty and acute care literature that was published between 2005 and 2015 in two databases and similarly with our review recommended that future research should focus on experimental studies [226].

Strengths of this study include an in-depth search strategy and very broad scope. We included all acute care specialties and synthesized the findings based on that. Due to this, clinicians and decisions makers will be able to review specific evidence pertaining directly to their specialty. We also involved reviewers with fluency in all relevant languages which allowed us to map and synthesize all the available literature around frailty in acute care. Finally, we did a detailed search for evidence related to EMS care which usually is excluded from frailty reviews. EMS frailty screening by paramedics could facilitate referral or transport to the most appropriate service as paramedics are in a unique position to document the living conditions and function of an older person within their own home [227].

Moreover, the purpose of this review was to highlight the current gaps in frailty research. We found that non-frailty tools were commonly used to identify frailty. Established frailty tools better capture the multidimensional nature of frailty than unidimensional non-frailty tools. We also found that frailty was rarely used in experimental and qualitative articles and was rarely used as an outcome measure. It was mostly used within geriatrics, emergency department, general medicine, and cardiology; information for other medical specialties is lacking. When frailty was used to predict outcomes, rarely were patient-oriented measures, such as function and quality of life included. In addition, since almost no clinical trials have been conducted with a focus on frailty, no guidelines exist on how care planning can be modified based on frailty. These research gaps need to be filled in order to implement frailty assessment and management plans in clinical practice, and to start the discussion about changes in policy.

This review highlights seven important call to action items:

-

Identify participants as frail only when it has been measured.

-

◦ In 67% of the articles the authors identified their participants as frail but did not report on how they measured frailty.

-

-

Report details of when and who measured frailty and other details about feasibility (e.g. time to complete assessment).

-

◦ In 13% of the articles the authors did not report when frailty was measured and in 19% authors did not report who measured frailty.

-

-

Use established frailty tools to measure frailty.

-

◦ Established tools were only used in 51% of the cases.

-

-

Conduct observational studies using patient-oriented outcomes.

-

◦ Quality of life and functional decline only accounted for 4% of outcomes examined.

-

-

Conduct qualitative studies about frailty.

-

Conduct experimental studies about modifying treatment plans based on frailty level.

-

◦ Only one prospective study modified treatment plans based on frailty [52].

-

-

Conduct experimental studies using frailty as an outcome.

The ability of acute care settings to cope with the influx of frail older patients may be reaching a limit, and unless changes are made in its organization, it seems inevitable that care provided to the older adult will suffer. Even though we presently lack strong evidence, identifying the frail people, those at higher risk for adverse outcomes, within EMS and in-hospital settings may lead to improvements in care. The development of a routinely collected frailty measure, such as the electronic Frailty Index of The National Health Service of England [228], can facilitate frailty to be considered in patients who come to hospital. How this will affect care has yet to be determined. Currently, comprehensive geriatric assessment (which also includes patient management) is the most effective intervention for frail older patients [229] and can also impact the patient’s frailty level. For example, a primary care model focusing on comprehensive geriatric assessment and goal-setting reversed frailty levels among older patients [230].

Recognizing the value of measuring frailty may benefit the patient and the health care system alike. By identifying frail individuals, we could increase patient-centered care and have a more efficient and effective health care system. It could lead to more targeted assessments for people who need them and end the unnecessary assessments of severely frail people. Therefore, frailty can assist clinicians in identifying patients who might benefit more from innovative processes of care than from aggressive medical treatments. Also, clinicians can use the information from the frailty assessments to discuss with patients and caregivers the risks and benefits of possible treatments, which can lead to a more informed and rational shared decision.

Conclusions

This scoping review showed that most studies were conducted in non-geriatric disciplines and identified participants as frail without measuring frailty. There was great variability in tools used to measure frailty. The more recently published studies were more likely to use established frailty tools and the most commonly used scales were the Clinical Frailty Scale, the Frailty Index, and the Frailty Phenotype. Most studies used frailty tools to predict adverse health outcomes, especially mortality and institutionalization. Overall, frailty appears to be a good predictor of adverse health outcomes.

References

Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752–62.

Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, Oude Voshaar RC. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(8):1487–92.

Theou O, Brothers TD, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Operationalization of frailty using eight commonly used scales and comparison of their ability to predict all-cause mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(9):1537–51.

Mitnitski A, Song X, Skoog I, Broe GA, Cox JL, Grunfeld E, Rockwood K. Relative fitness and frailty of elderly men and women in developed countries and their relationship with mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(12):2184–9.

Theou O, Rockwood K. Comparison and clinical applications of the frailty phenotype and frailty index approaches. Interdiscip Top Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;41:74–84. Epub 2015 Jul 17

Theou O, Rockwood. Should frailty status always be considered when treating the elderly patient? Aging Health. 2012;8(3):261–71.

Cheung A, Haas B, Ringer TJ, McFarlan A, Wong CL. Canadian study of health and aging clinical frailty scale: does it predict adverse outcomes among geriatric trauma patients? J Am Coll Surg. 2017;225:658.

Bebb O, Smith FG, Clegg A, Hall M, Gale CP. Frailty and acute coronary syndrome: a structured literature review. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2017;20:2048872617700873.

de Vries NM, Staal JB, van Ravensberg CD, Hobbelen JS, Olde Rikkert MG, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW. Outcome instruments to measure frailty: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(1):104–14.

Rodriguez-Manas L, Feart C, Mann G, et al. Searching for an operational definition of frailty: a Delphi method based consensus statement. The frailty operative definition-consensus conference project. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;68(1):62–7.

Theou O, Kloseck M. Tools to identify community-dwelling older adults in different stages of frailty. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. 2007;26(3):1–21.

Drubbel I, Numans ME, Kranenburg G, Bleijenberg N, de Wit NJ, Schuurmans MJ. Screening for frailty in primary care: a systematic review of the psychometric properties of the frailty index in community-dwelling older people. BMC Geriatr. 2014;6(14):27.

Pialoux T, Goyard J, Lesourd B. Screening tools for frailty in primary health care: a systematic review. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2012;12(2):189–97.

Sieliwonczyk E, Perkisas S, Vandewoude M. Frailty indexes, screening instruments and their application in Belgian primary care. Acta Clin Belg. 2014;69(4):233–9.

Shamliyan T, Talley KM, Ramakrishnan R, Kane RL. Association of frailty with survival: a systematic literature review. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(2):719–36.

Latham LP, Ackroyd-Stolarz S. Emergency department utilization by older adults: a descriptive study. Can Geriatr J. 2014;17(4):118.

Lowthian JA, Jolley DJ, Curtis AJ, Currell A, Cameron PA, Stoelwinder JU, McNeil JJ. The challenges of population ageing: accelerating demand for emergency ambulance services by older patients, 1995–2015. Med J Aust. 2011;194(11):574–8.

Dellasega CA, Zerbe TM. A multimethod study of advanced practice nurse postdischarge care. Clin Excell Nurse Pract. 2000;4(5):286–93.

Hanlon JT, Maher RL, Lindblad CI, Ruby CM, Twersky J, Cohen HJ, Schmader KE. Comparison of methods for detecting potential adverse drug events in frail elderly inpatients and outpatients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001;58(17):1622–6.

Lichtman JH, Krumholz HM, Wang Y, Radford MJ, Brass LM. Risk and predictors of stroke after myocardial infarction among the elderly. Circulation. 2002;105(9):1082–7.

Klepin HD, Geiger AM, Tooze JA, Kritchevsky SB, Williamson JD, Ellis LR, Levitan D, Pardee TS, Isom S, Powell BL. The feasibility of inpatient geriatric assessment for older adults receiving induction chemotherapy for acute myelogenous leukemia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(10):1837–46.

Cohen HJ, Feussner JR, Weinberger M, Carnes M, Hamdy RC, Hsieh F, Phibbs C, Courtney D, Lyles KW, May C, McMurtry C. A controlled trial of inpatient and outpatient geriatric evaluation and management. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(12):905–12.

Saltvedt I, Mo ES, Fayers P, Kaasa S, Sletvold O. Reduced mortality in treating acutely sick, frail older patients in a geriatric evaluation and management unit. A prospective randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(5):792–8.

Dai YT, Wu SC, Weng R. Unplanned hospital readmission and its predictors in patients with chronic conditions. J Formos Med Assoc. 2002;101(11):779–85.

Schmader KE, Hanlon JT, Pieper CF, Sloane R, Ruby CM, Twersky J, Francis SD, Branch LG, Lindblad CI, Artz M, Weinberger M. Effects of geriatric evaluation and management on adverse drug reactions and suboptimal prescribing in the frail elderly. Am J Med. 2004;116(6):394–401.

Brenner SS, Klotz U. P-glycoprotein function in the elderly. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;60(2):97–102.

Chouliara Z, Kearney N, Worth A, Stott D. Challenges in conducting research with hospitalized older people with cancer: drawing from the experience of an ongoing interview-based project. Eur J Cancer Care. 2004;13(5):409–15.

Hanlon JT, Artz MB, Pieper CF, Lindblad CI, Sloane RJ, Ruby CM, Schmader KE. Inappropriate medication use among frail elderly inpatients. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38(1):9–14.

Pitkala KH, Laurila JV, Strandberg TE, Tilvis RS. Prognostic significance of delirium in frail older people. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;19(2–3):158–63.

Saltvedt I, Saltnes T, Mo ES, Fayers P, Kaasa S, Sletvold O. Acute geriatric intervention increases the number of patients able to live at home. A prospective randomized study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2004;16(4):300–6.

Torres OH, Muñoz J, Ruiz D, Ris J, Gich I, Coma E, Gurguí M, Vázquez G. Outcome predictors of pneumonia in elderly patients: importance of functional assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(10):1603–9.

Vitagliano G, Curtis JP, Concato J, Feinstein AR, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Association between functional status and use and effectiveness of beta-blocker prophylaxis in elderly survivors of acute myocardial infarction. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(4):495–501.

Studenski S, Hayes RP, Leibowitz RQ, Bode R, Lavery L, Walston J, Duncan P, Perera S. Clinical global impression of change in physical frailty: development of a measure based on clinical judgment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(9):1560–6.

Andrew MK, Freter SH, Rockwood K. Incomplete functional recovery after delirium in elderly people: a prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2005;5(1):5.

Hajjar ER, Hanlon JT, Sloane RJ, Lindblad CI, Pieper CF, Ruby CM, Branch LC, Schmader KE. Unnecessary drug use in frail older people at hospital discharge. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(9):1518–23.

Herrmann FR, Osiek A, Cos M, Michel JP, Robine JM. Frailty judgment by hospital team members: degree of agreement and survival prediction. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(5):916–7.

Lindblad CI, Artz MB, Pieper CF, Sloane RJ, Hajjar ER, Ruby CM, Schmader KE, Hanlon JT. Potential drug—disease interactions in frail, hospitalized elderly veterans. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39(3):412–7.

Rao AV, Hsieh F, Feussner JR, Cohen HJ. Geriatric evaluation and management units in the care of the frail elderly cancer patient. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Med Sci. 2005;60(6):798–803.

Saltvedt I, Spigset O, Ruths S, Fayers P, Kaasa S, Sletvold O. Patterns of drug prescription in a geriatric evaluation and management unit as compared with the general medical wards: a randomised study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61(12):921–8.

Stretton CM, Latham NK, Carter KN, Lee AC, Anderson CS. Determinants of physical health in frail older people: the importance of self-efficacy. Clin Rehabil. 2006;20(4):357–66.

Young J, Robinson M, Chell S, Sanderson D, Chaplin S, Burns E, Fear J. A prospective baseline study of frail older people before the introduction of an intermediate care service. Health Soc Care Community. 2005;13(4):307–12.

Hanlon JT, Pieper CF, Hajjar ER, Sloane RJ, Lindblad CI, Ruby CM, Schmader KE. Incidence and predictors of all and preventable adverse drug reactions in frail elderly persons after hospital stay. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Med Sci. 2006;61(5):511–5.

Kaiser RM, Schmader KE, Pieper CF, Lindblad CI, Ruby CM, Hanlon JT. Therapeutic failure-related hospitalisations in the frail elderly. Drugs Aging. 2006;23(7):579–86.

Lindblad CI, Hanlon JT, Gross CR, Sloane RJ, Pieper CF, Hajjar ER, Ruby CM, Schmader KE, Panel MC. Clinically important drug-disease interactions and their prevalence in older adults. Clin Ther. 2006;28(8):1133–43.

Purser JL, Kuchibhatla MN, Fillenbaum GG, Harding T, Peterson ED, Alexander KP. Identifying frailty in hospitalized older adults with significant coronary artery disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(11):1674–81.

Rodríguez-Molinero A, López-Diéguez M, Tabuenca AI, de la Cruz JJ, Banegas JR. Functional assessment of older patients in the emergency department: comparison between standard instruments, medical records and physicians’ perceptions. BMC Geriatr. 2006;6(1):13.

Saltvedt I, Jordhøy M, Mo ES, Fayers P, Kaasa S, Sletvold O. Randomised trial of in-hospital geriatric intervention: impact on function and morale. Gerontology. 2006;52(4):223–30.

Copeland LA, Zeber JE, Rosenheck RA, Miller AL. Unforeseen inpatient mortality among veterans with schizophrenia. Med Care. 2006;44(2):110–6.

Basso U, Tonti S, Bassi C, Brunello A, Pasetto LM, Scaglione D, Falci C, Beda M, Aversa SM, Stefani M, Castegnaro E. Management of frail and not-frail elderly cancer patients in a hospital-based geriatric oncology program. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;66(2):163–70.

Ertel KA, Glymour MM, Glass TA, Berkman LF. Frailty modifies effectiveness of psychosocial intervention in recovery from stroke. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21(6):511–22.

Guerra IC, Ramos-Cerqueira AT. Risco de hospitalizações repetidas em idosos usuários de um centro de saúde escola. Cad Saude Publica. 2007;23:585–92.

Massa E, Madeddu C, Astara G, Pisano M, Spiga C, Tanca FM, Sanna E, Puddu I, Patteri E, Lamonica G, Deiana L. An attempt to correlate a “Multidimensional Geriatric Assessment” (MGA), treatment assignment and clinical outcome in elderly cancer patients: results of a phase II open study. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;66(1):75–83.

Söderback I. Hospital discharge among frail elderly people: a pilot study in Sweden. Occup Ther Int. 2008;15(1):18–31.

van Iersel MB, Munneke M, Esselink RA, Benraad CE, Rikkert MG. Gait velocity and the timed-up-and-go test were sensitive to changes in mobility in frail elderly patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(2):186–91.

Duffy SA, Copeland LA, Hopp FP, Zalenski RJ. Diagnostic classifications and resource utilization of decedents served by the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(5):1137–45.

Adamis D, Treloar A, Martin FC, Gregson N, Hamilton G, Macdonald AJ. APOE and cytokines as biological markers for recovery of prevalent delirium in elderly medical inpatients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(7):688–94.

Adamis D, Treloar A, Darwiche FZ, Gregson N, Macdonald AJ, Martin FC. Associations of delirium with in-hospital and in 6-months mortality in elderly medical inpatients. Age Ageing. 2007;36(6):644–9.

Ansell P, Howell D, Garry A, Kite S, Munro J, Roman E, Howard M. What determines referral of UK patients with haematological malignancies to palliative care services? An exploratory study using hospital records. Palliat Med. 2007;21(6):487–92.

Lindberg M, Saltvedt I, Sletvold O, Bjerve KS. Long-chain n− 3 fatty acids and mortality in elderly patients. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(3):722–9.

Lindhardt T, Nyberg P, Hallberg IR. Collaboration between relatives of elderly patients and nurses and its relation to satisfaction with the hospital care trajectory. Scand J Caring Sci. 2008;22(4):507–19.

Pepersack T. Minimum geriatric screening tools to detect common geriatric problems. J Nutr Health Aging. 2008;12(5):348–52.

Ridda I, Lindley R, MacIntyre RC. The challenges of clinical trials in the exclusion zone: the case of the frail elderly. Australas J Ageing. 2008;27(2):61–6.

Rockwood K, Rockwood MR, Andrew MK, Mitnitski A. Reliability of the hierarchical assessment of balance and mobility in frail older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(7):1213–7.

Thomas C, Hestermann U, Walther S, Pfueller U, Hack M, Oster P, Mundt C, Weisbrod M. Prolonged activation EEG differentiates dementia with and without delirium in frail elderly. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(2):119–25.

Cohen M. Research assessment of elder neglect and its risk factors in a hospital setting. Intern Med J. 2008;38(9):704–7.

Wong RY, Miller WC. Adverse outcomes following hospitalization in acutely ill older patients. BMC Geriatr. 2008;8(1):10.

Andela RM, Dijkstra A, Slaets JP, Sanderman R. Prevalence of frailty on clinical wards: description and implications. Int J Nurs Pract. 2010;16(1):14–9.

Buttery AK, Martin FC. Knowledge, attitudes and intentions about participation in physical activity of older post-acute hospital inpatients. Physiotherapy. 2009;95(3):192–8.

Ekdahl AW, Andersson L, Friedrichsen M. “They do what they think is the best for me.” Frail elderly patients’ preferences for participation in their care during hospitalization. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80(2):233–40.

Hilmer SN, Perera V, Mitchell S, Murnion BP, Dent J, Bajorek B, Matthews S, Rolfson DB. The assessment of frailty in older people in acute care. Australas J Ageing. 2009;28(4):182–8.

Perera V, Bajorek BV, Matthews S, Hilmer SN. The impact of frailty on the utilisation of antithrombotic therapy in older patients with atrial fibrillation. Age Ageing. 2009;38(2):156–62.

Vivanti AP, McDonald CK, Palmer MA, Sinnott M. Malnutrition associated with increased risk of frail mechanical falls among older people presenting to an emergency department. Emerg Med Australas. 2009;21(5):386–94.

Wright RM, Sloane R, Pieper CF, Ruby-Scelsi C, Twersky J, Schmader KE, Hanlon JT. Underuse of indicated medications among physically frail older US veterans at the time of hospital discharge: results of a cross-sectional analysis of data from the geriatric evaluation and management drug study. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2009;7(5):271–80.

Baird S, Hill L, Rybar J, Concha-Garcia S, Coimbra R, Patrick K. Age-related driving disorders: screening in hospitals and outpatients settings. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2010;10(4):288–94.

Buck HG, Riegel B. The impact of frailty on health related quality of life in heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;10(3):159–66.

De Breucker S, Herzog G, Pepersack T. Could geriatric characteristics explain the under-prescription of anticoagulation therapy for older patients admitted with atrial fibrillation? Drugs Aging. 2010;27(10):807–13.

Matsuzawa T, Sakurai T, Kuranaga M, Endo H, Yokono K. Predictive factors for hospitalized and institutionalized care-giving of the aged patients with diabetes mellitus in Japan. Kobe J Med Sci. 2010;56(4):E173–83.

Stiffler KA, Finley A, Midha S, Wilber ST. Frailty assessment in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2013;45(2):291–8.

Arora VM, Prochaska ML, Farnan JM, D'Arcy V, Michael J, Schwanz KJ, Vinci LM, Davis AM, Meltzer DO, Johnson JK. Problems after discharge and understanding of communication with their primary care physicians among hospitalized seniors: a mixed methods study. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):385–91.

Frew E, Sequeira J, Cant R. Nutrition screening process for patients in an acute public hospital servicing an elderly, culturally diverse population. Nutr Diet. 2010;67(2):71–6.

Abbatecola AM, Spazzafumo L, Corsonello A, Sirolla C, Bustacchini S, Guffanti E. Development and validation of the HOPE prognostic index on 24-month posthospital mortality and rehospitalization: Italian National Research Center on Aging (INRCA). Rejuvenation Res. 2011;14(6):605–13.

Dramé M, Novella JL, Jolly D, Lanièce I, Somme D, Heitz D, Gauvain JB, Voisin T, De Wazières B, Gonthier R, Jeandel C. Rapid cognitive decline, one-year institutional admission and one-year mortality: analysis of the ability to predict and inter-tool agreement of four validated clinical frailty indexes in the SAFEs cohort. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15(8):699–705.

Ekerstad N, Swahn E, Janzon M, Alfredsson J, Löfmark R, Lindenberger M, Carlsson P. Frailty is independently associated with short-term outcomes for elderly patients with non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2011;124(22):2397–404.

Hill L, Rybar J, Baird S, Concha-Garcia S, Coimbra R, Patrick K. Road safe seniors: screening for age-related driving disorders in inpatient and outpatient settings. J Saf Res. 2011;42(3):165–9.

Hubbard RE, Eeles EM, Rockwood MR, Fallah N, Ross E, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Assessing balance and mobility to track illness and recovery in older inpatients. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(12):1471–8.

Mitchell SJ, Hilmer SN, Murnion BP, Matthews S. Hepatotoxicity of therapeutic short-course paracetamol in hospital inpatients: impact of ageing and frailty. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2011;36(3):327–35.

Njemini R, Bautmans I, Onyema OO, Van Puyvelde K, Demanet C, Mets T. Circulating heat shock protein 70 in health, aging and disease. BMC Immunol. 2011;12(1):24.

Popejoy LL. Complexity of family caregiving and discharge planning. J Fam Nurs. 2011;17(1):61–81.

Singh M, Rihal CS, Lennon RJ, Spertus JA, Nair KS, Roger VL. Influence of frailty and health status on outcomes in patients with coronary disease undergoing percutaneous revascularization. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4(5):496–502.

Sánchez E, Vidán MT, Serra JA, Fernández-Avilés F, Bueno H. Prevalence of geriatric syndromes and impact on clinical and functional outcomes in older patients with acute cardiac diseases. Heart. 2011;97(19):1602–6.

Vicente V, Ekebergh M, Castren M, Sjöstrand F, Svensson L, Sundström BW. Differentiating frailty in older people using the Swedish ambulance service: a retrospective audit. Int Emerg Nurs. 2012;20(4):228–35.

Wilhelmson K, Duner A, Eklund K, Gosman-Hedström G, Blomberg S, Hasson H, Gustafsson H, Landahl S, Dahlin-Ivanoff S. Design of a randomized controlled study of a multi-professional and multidimensional intervention targeting frail elderly people. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11(1):24.

Fracchia S, Grasso A, Pagani M, Corsini C, Cerina G, Ghirmai S, Bernardini B, Berra C, Badalamenti S, Campanati P, Boncinelli S. Il paziente anziano nel setting di cura per acuti: ruolo di uno strumento di assessment rapido multidimensionale nell’identificazione dei pazienti a rischio. G Gerontol. 2011;59:130–9.

Villanyi D, Fok M, Wong RY. Medication reconciliation: identifying medication discrepancies in acutely ill hospitalized older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2011;9(5):339–44.

Popejoy L. Participation of elder persons, families, and health care teams in hospital discharge destination decisions. Appl Nurs Res. 2011;24(4):256–62.

Hendrix CC, Hastings SN, Van Houtven C, Steinhauser K, Chapman J, Ervin T, Sanders L, Weinberger M. Pilot study: individualized training for caregivers of hospitalized older veterans. Nurs Res. 2011;60(6):436–41.

Dalleur O, Spinewine A, Henrard S, Losseau C, Speybroeck N, Boland B. Inappropriate prescribing and related hospital admissions in frail older persons according to the STOPP and START criteria. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(10):829–37.

De Brauwer I, Lepage S, Yombi JC, Cornette P, Boland B. Prediction of risk of in-hospital geriatric complications in older patients with hip fracture. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2012;24(1):62–7.

Eeles EM, White SV, O'mahony SM, Bayer AJ, Hubbard RE. The impact of frailty and delirium on mortality in older inpatients. Age Ageing. 2012;41(3):412–6.

Farhat JS, Velanovich V, Falvo AJ, Horst HM, Swartz A, Patton Jr JH, Rubinfeld IS. Are the frail destined to fail? Frailty index as predictor of surgical morbidity and mortality in the elderly. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72(6):1526–31.

Khandelwal D, Goel A, Kumar U, Gulati V, Narang R, Dey AB. Frailty is associated with longer hospital stay and increased mortality in hospitalized older patients. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16(8):732-5.

Lococo F, Cesario A, Margaritora S, Nachira D, Leuzzi G, Porziella V, Meacci E, Vita ML, Congedo MT, Granone P. Clinical effect of bovine pericardial strips on air leak after stapled pulmonary resection in “frail” patients: early results. Minerva Chir. 2012;67(1):87–94.

Masud D, Norton S, Smailes S, Shelley O, Philp B, Dziewulski P. The use of a frailty scoring system for burns in the elderly. Burns. 2013;39(1):30–6.

Pilotto A, Rengo F, Marchionni N, Sancarlo D, Fontana A, Panza F, Ferrucci L, FIRI-SIGG study group. Comparing the prognostic accuracy for all-cause mortality of frailty instruments: a multicentre 1-year follow-up in hospitalized older patients. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29090.

Rao MY, Rao TS, Narayanaswamy RK. Study of hypothalamo pituitary adrenal axis in frail elderly subjects. J Assoc Physicians India. 2012;60:31–4.

Salvi F, Morichi V, Grilli A, Lancioni L, Spazzafumo L, Polonara S, Abbatecola AM, De Tommaso G, Dessi-Fulgheri P, Lattanzio F. Screening for frailty in elderly emergency department patients by using the Identification of Seniors At Risk (ISAR). J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16(4):313–8.

Gharacholou SM, Sloane R, Cohen HJ, Schmader KE. Geriatric inpatient units in the care of hospitalized frail adults with a history of heart failure. Int J Gerontol. 2012;6(2):112–6.

Hansen T, Lambert HC, Faber J. Ingestive skill difficulties are frequent among acutely-hospitalized frail elderly patients, and predict hospital outcomes. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. 2012;30(4):271–87.

Frank C, Touw M, Suurdt J, Jiang X, Wattam P, Heyland DK. Optimizing end-of-life care on medical clinical teaching units using the CANHELP questionnaire and a nurse facilitator: a feasibility study. CJNR. 2012;44(1):40–58.

Moorhouse P, Mallery LH. Palliative and therapeutic harmonization: a model for appropriate decision-making in frail older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(12):2326–32.

Aitken E, Carruthers C, Gall L, Kerr L, Geddes C, Kingsmore D. Acute kidney injury: outcomes and quality of care. QJM. 2013;106(4):323–32.

Ariza-Solé A, Formiga F, Vidán MT, Bueno H, Curós A, Aboal J, Llibre C, Rueda F, Bernal E, Cequier A. Impact of frailty and functional status on outcomes in elderly patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary angioplasty: rationale and design of the IFFANIAM study. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36(10):565–9.

Auais M, Morin S, Nadeau L, Finch L, Mayo N. Changes in frailty-related characteristics of the hip fracture population and their implications for healthcare services: evidence from Quebec, Canada. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(10):2713–24.

Bouzereau V, Le Caer F, Guardiola E, Scavennec C, Barriere JR, Chaix L, Le Caer H. Experience of multidisciplinary assessment of elderly patients with cancer in a French general hospital during 1 year: a new model care study. J Geriatr Oncol. 2013;4(4):394–401.

Compte N, Boudjeltia KZ, Vanhaeverbeek M, De Breucker S, Tassignon J, Trelcat A, Pepersack T, Goriely S. Frailty in old age is associated with decreased interleukin-12/23 production in response to toll-like receptor ligation. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e65325.

Conroy S, Dowsing T. The ability of frailty to predict outcomes in older people attending an acute medical unit. Acute Med. 2013;12(2):74–6.

Corona G, Polesel J, Fratino L, Miolo G, Rizzolio F, Crivellari D, Addobbati R, Cervo S, Toffoli G. Metabolomics biomarkers of frailty in elderly breast cancer patients. J Cell Physiol. 2014;229(7):898–902.

Dorner TE, Lackinger C, Haider S, Luger E, Kapan A, Luger M, Schindler KE. Nutritional intervention and physical training in malnourished frail community-dwelling elderly persons carried out by trained lay “buddies”: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1232.

Eklund K, Wilhelmson K, Gustafsson H, Landahl S, Dahlin-Ivanoff S. One-year outcome of frailty indicators and activities of daily living following the randomised controlled trial; “Continuum of care for frail older people”. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13(1):76.

Fontana L, Addante F, Copetti M, Paroni G, Fontana A, Sancarlo D, Pellegrini F, Ferrucci L, Pilotto A. Identification of a metabolic signature for multidimensional impairment and mortality risk in hospitalized older patients. Aging Cell. 2013;12(3):459–66.

Graham MM, Galbraith PD, O'Neill D, Rolfson DB, Dando C, Norris CM. Frailty and outcome in elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29(12):1610–5.

Hignett S, Sands G, Griffiths P. In-patient falls: what can we learn from incident reports? Age Ageing. 2013;42(4):527–31.

Hunt K, Walsh B, Voegeli D, Roberts H. Reducing avoidable hospital admission in older people: health status, frailty and predicting risk of ill-defined conditions diagnoses in older people admitted with collapse. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;57(2):172–6.

Ijkema R, Langelaan M, Van de Steeg L, Wagner C. What impedes and what facilitates a quality improvement project for older hospitalized patients? Int J Qual Health Care. 2013;26(1):41–8.

Joseph B, Pandit V, Rhee P, Aziz H, Sadoun M, Wynne J, Tang A, Kulvatunyou N, O’Keeffe T, Fain MJ, Friese RS. Predicting hospital discharge disposition in geriatric trauma patients: is frailty the answer? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76(1):196–200.

Krishnan M, Beck S, Havelock W, Eeles E, Hubbard RE, Johansen A. Predicting outcome after hip fracture: using a frailty index to integrate comprehensive geriatric assessment results. Age Ageing. 2013;43(1):122–6.

Ma HM, Yu RH, Woo J. Recurrent hospitalisation with pneumonia is associated with higher 1-year mortality in frail older people. Intern Med J. 2013;43(11):1210–5.

Matsuzawa Y, Konishi M, Akiyama E, Suzuki H, Nakayama N, Kiyokuni M, Sumita S, Ebina T, Kosuge M, Hibi K, Tsukahara K. Association between gait speed as a measure of frailty and risk of cardiovascular events after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(19):1964–72.

Oliveira DR, Bettinelli LA, Pasqualotti A, Corso D, Brock F, Erdmann AL. Prevalence of frailty syndrome in old people in a hospital institution. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2013;21(4):891–8.

Oo MT, Tencheva A, Khalid N, Chan YP, Ho SF. Assessing frailty in the acute medical admission of elderly patients. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2012;43(4):301–8.

Patel KV, Brennan KL, Brennan ML, Jupiter DC, Shar A, Davis ML. Association of a modified frailty index with mortality after femoral neck fracture in patients aged 60 years and older. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(3):1010–7.

Phillips AC, Upton J, Duggal NA, Carroll D, Lord JM. Depression following hip fracture is associated with increased physical frailty in older adults: the role of the cortisol: dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate ratio. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13(1):60.

Polidoro A, Stefanelli F, Ciacciarelli M, Pacelli A, Di Sanzo D, Alessandri C. Frailty in patients affected by atrial fibrillation. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;57(3):325–7.

Bugat ME, Gerard S, Balardy L, Beyne-Rauzy O, Boussier N, Perrin A, Oustric S, Vellas B, Nourhashemi F. Impact of an oncogeriatric consulting team on therapeutic decision-making. J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17(5):473.

Ryan T, Ingleton C, Gardiner C, Parker C, Gott M, Noble B. Symptom burden, palliative care need and predictors of physical and psychological discomfort in two UK hospitals. BMC Palliat Care. 2013;12(1):11.

Velanovich V, Antoine H, Swartz A, Peters D, Rubinfeld I. Accumulating deficits model of frailty and postoperative mortality and morbidity: its application to a national database. J Surg Res. 2013;183(1):104–10.

Lisiecki J, Zhang P, Wang L, Rinkinen J, De La Rosa S, Enchakalody B, Brownley RC, Wang SC, Buchman SR, Levi B. Morphomic measurement of the temporalis muscle and zygomatic bone as novel predictors of hospital-based clinical outcomes in patients with mandible fracture. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24(5):1577–81.

Myers V, Broday DM, Steinberg DM, Drory Y, Gerber Y. Exposure to particulate air pollution and long-term incidence of frailty after myocardial infarction. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23(7):395–400.

Conroy SP, Dowsing T, Reid J, Hsu R. Understanding readmissions: an in-depth review of 50 patients readmitted back to an acute hospital within 30 days. Eur Geriatr Med. 2013;4(1):25–7.

Zorman JV, Lusa L, Strle F, Maraspin V. Bacterial infection in elderly nursing home and community-based patients: a prospective cohort study. Infection. 2013;41(5):909–16.

Baldin Storti L, Coelho Fabrício-Whebe SC, Kusumota L, Partezani Rodrigues RA, Marques S. Fragilidade de idosos internados na clínica médica da unidade de emergência de um hospital geral terciário. Texto Contexto Enfermagem. 2013;22(2):452-9.

Bakker FC, Persoon A, Schoon Y, Rikkert O, Marcel GM. Hospital elder life program integrated in dutch hospital care: a pilot. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(4):641–2.

Maxwell CA. Screening hospitalized injured older adults for cognitive impairment and pre-injury functional impairment. Appl Nurs Res. 2013;26(3):146–50.

Aronow HU, Borenstein J, Haus F, Braunstein GD, Bolton LB. Validating SPICES as a screening tool for frailty risks among hospitalized older adults. Nurs Res Pract. 2014;2014:846759.

Baillie L, Gallini A, Corser R, Elworthy G, Scotcher A, Barrand A. Care transitions for frail, older people from acute hospital wards within an integrated healthcare system in England: a qualitative case study. Int J Integr Care. 2014;14(1):e009.

Bakker FC, Persoon A, Bredie SJ, van Haren-Willems J, Leferink VJ, Noyez L, Schoon Y, Rikkert MG. The CareWell in hospital program to improve the quality of care for frail elderly inpatients: results of a before–after study with focus on surgical patients. Am J Surg. 2014;208(5):735–46.

Bakker FC, Persoon A, Schoon Y, Marcel GM, Rikkert O. The CareWell in hospital questionnaire: a measure of frail elderly inpatient experiences with individualized and integrated hospital care. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(5):324–9.

Baldwin MR, Reid MC, Westlake AA, Rowe JW, Granieri EC, Wunsch H, Dam TT, Rabinowitz D, Goldstein NE, Maurer MS, Lederer DJ. The feasibility of measuring frailty to predict disability and mortality in older medical intensive care unit survivors. J Crit Care. 2014;29(3):401–8.

Bennett A, Gnjidic D, Gillett M, Carroll P, Matthews S, Johnell K, Fastbom J, Hilmer S. Prevalence and impact of fall-risk-increasing drugs, polypharmacy, and drug–drug interactions in robust versus frail hospitalised falls patients: a prospective cohort study. Drugs Aging. 2014;31(3):225–32.

Compté N, Bailly B, De Breucker S, Goriely S, Pepersack T. Study of the association of total and differential white blood cell counts with geriatric conditions, cardio-vascular diseases, seric IL-6 levels and telomere length. Exp Gerontol. 2015;61:105–12.

Crehan F, O'Shea D, Ryan JM, Horgan F. A profile of elderly fallers referred for physiotherapy in the emergency department of a Dublin teaching hospital. Ir Med J. 2013;106(6):173–6.

Dalleur O, Boland B, Losseau C, Henrard S, Wouters D, Speybroeck N, Degryse JM, Spinewine A. Reduction of potentially inappropriate medications using the STOPP criteria in frail older inpatients: a randomised controlled study. Drugs Aging. 2014;31(4):291–8.

Denoël P, Vanderstraeten J, Mols P, Pepersack T. Could some geriatric characteristics hinder the prescription of anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation in the elderly? J Aging Res. 2014;2014:693740.

Dent E, Perez-Zepeda M. Comparison of five indices for prediction of adverse outcomes in hospitalised Mexican older adults: a cohort study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;60(1):89–95.

TE D, Luger E, Tschinderle J, Stein KV, Haider S, Kapan A, Lackinger C, Schindler KE. Association between nutritional status (MNA®-SF) and frailty (SHARE-FI) in acute hospitalised elderly patients. J Nutr Health Aging. 2014;18(3):264–9.

Evans SJ, Sayers M, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. The risk of adverse outcomes in hospitalized older patients in relation to a frailty index based on a comprehensive geriatric assessment. Age Ageing. 2014;43(1):127–32.

Fairchild B, Webb TP, Xiang Q, Tarima S, Brasel KJ. Sarcopenia and frailty in elderly trauma patients. World J Surg. 2015;39(2):373–9.

Forti P, Maioli F, Zagni E, Lucassenn T, Montanari L, Maltoni B, Pirazzoli GL, Bianchi G, Zoli M. The physical phenotype of frailty for risk stratification of older medical inpatients. J Nutr Health Aging. 2014;18(10):912–8.

Goldstein J, Hubbard RE, Moorhouse P, Andrew MK, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. The validation of a care partner-derived frailty index based upon comprehensive geriatric assessment (CP-FI-CGA) in emergency medical services and geriatric ambulatory care. Age Ageing. 2014;44(2):327–30.

Grossman D, Rootenberg M, Perri GA, Yogaparan T, DeLeon M, Calabrese S, Grief CJ, Moore J, Gill A, Stilos K, Daines P. Enhancing communication in end-of-life care: a clinical tool translating between the clinical frailty scale and the palliative performance scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(8):1562–7.

Harvey P, Storer M, Berlowitz DJ, Jackson B, Hutchinson A, Lim WK. Feasibility and impact of a post–discharge geriatric evaluation and management service for patients from residential care: the Residential Care Intervention Program in the Elderly (RECIPE). BMC Geriatr. 2014;14(1):48.

Heim N, van Fenema EM, Weverling-Rijnsburger AW, Tuijl JP, Jue P, Oleksik AM, Verschuur MJ, Haverkamp JS, Blauw GJ, van der Mast RC, Westendorp RG. Optimal screening for increased risk for adverse outcomes in hospitalised older adults. Age Ageing. 2014;44(2):239–44.

Joosten E, Demuynck M, Detroyer E, Milisen K. Prevalence of frailty and its ability to predict in hospital delirium, falls, and 6-month mortality in hospitalized older patients. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14(1):1.

Joseph B, Pandit V, Zangbar B, Kulvatunyou N, Tang A, O'Keeffe T, Green DJ, Vercruysse G, Fain MJ, Friese RS, Rhee P. Validating trauma-specific frailty index for geriatric trauma patients: a prospective analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219(1):10–7.

Joseph B, Pandit V, Zangbar B, Kulvatunyou N, Hashmi A, Green DJ, O’Keeffe T, Tang A, Vercruysse G, Fain MJ, Friese RS. Superiority of frailty over age in predicting outcomes among geriatric trauma patients: a prospective analysis. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(8):766–72.

MacIntyre CR, Ridda I, Gao Z, Moa AM, McIntyre PB, Sullivan JS, Jones TR, Hayen A, Lindley RI. A randomized clinical trial of the immunogenicity of 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine compared to 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine in frail, hospitalized elderly. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94578.

Maes F, Dalleur O, Henrard S, Wouters D, Scavée C, Spinewine A, Boland B. Risk scores and geriatric profile: can they really help us in anticoagulation decision making among older patients suffering from atrial fibrillation? Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:1091.

Maxwell CA, Dietrich MS, Minnick AF, Mion LC. Preinjury physical function and frailty in injured older adults: self-versus proxy responses. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(7):1443–7.

Ponzetti A, Lista P, Pagano E, Demichelis MM, Ciuffreda L, Ciccone G. Role of multidimensional assessment of frailty in predicting short-term outcomes in hospitalized cancer patients: results of a prospective cohort study. Tumori. 2014;100(1):91–6.

Pugh JA, Wang CP, Espinoza SE, Noël PH, Bollinger M, Amuan M, Finley E, Pugh MJ. Influence of frailty-related diagnoses, high-risk prescribing in elderly adults, and primary care use on readmissions in fewer than 30 days for veterans aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(2):291–8.

Rosted E, Schultz M, Dynesen H, Dahl M, Sørensen M, Sanders S. The identification of seniors at risk screening tool is useful for predicting acute readmissions. Dan Med J. 2014;61(5):A4828.

Sanchis J, Bonanad C, Ruiz V, Fernández J, García-Blas S, Mainar L, Ventura S, Rodríguez-Borja E, Chorro FJ, Hermenegildo C, Bertomeu-González V. Frailty and other geriatric conditions for risk stratification of older patients with acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J. 2014;168(5):784–91.

Sujino Y, Tanno J, Nakano S, Funada S, Hosoi Y, Senbonmatsu T, Nishimura S. Impact of hypoalbuminemia, frailty, and body mass index on early prognosis in older patients (≥ 85 years) with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Cardiol. 2015;66(3):263–8.

Vidán MT, Sánchez E, Fernández-Avilés F, Serra-Rexach JA, Ortiz J, Bueno H. FRAIL-HF, a study to evaluate the clinical complexity of heart failure in nondependent older patients: rationale, methods and baseline characteristics. Clin Cardiol. 2014;37(12):725–32.

Capan M, Ivy JS, Rohleder T, Hickman J, Huddleston JM. Individualizing and optimizing the use of early warning scores in acute medical care for deteriorating hospitalized patients. Resuscitation. 2015;93:107–12.

Bagshaw SM, Stelfox HT, Johnson JA, McDermid RC, Rolfson DB, Tsuyuki RT, Ibrahim Q, Majumdar SR. Long-term association between frailty and health-related quality of life among survivors of critical illness: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(5):973–82.

Poudel A, Peel NM, Nissen L, Mitchell C, Gray LC, Hubbard RE. Potentially inappropriate prescribing in older patients discharged from acute care hospitals to residential aged care facilities. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(11):1425–33.

Kimmel LA, Holland AE, Simpson PM, Edwards ER, Gabbe BJ. Validating a simple discharge planning tool following hospital admission for an isolated lower limb fracture. Phys Ther. 2014;94(7):1005–13.

Rose M, Pan H, Levinson MR, Staples M. Can frailty predict complicated care needs and length of stay? Intern Med J. 2014;44(8):800–5.

Ormerod JO, Ramcharitar S. Does specific interventional risk scoring better predict mortality than comorbidity in nonagenerians undergoing coronary angioplasty? Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2014;15(4):258–60.

Andreasen J, Sørensen EE, Gobbens RJ, Lund H, Aadahl M. Danish version of the Tilburg frailty indicator–translation, cross-cultural adaption and validity pretest by cognitive interviewing. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;59(1):32–8.

Dwyer JG, Reynoso JF, Seevers GA, Schmid KK, Muralidhar P, Konigsberg B, Lynch TG, Johanning JM. Assessing preoperative frailty utilizing validated geriatric mortality calculators and their association with postoperative hip fracture mortality risk. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2014;5(3):109–15.

Hii TB, Lainchbury JG, Bridgman PG. Frailty in acute cardiology: comparison of a quick clinical assessment against a validated frailty assessment tool. Heart Lung Circ. 2015;24(6):551–6.

Ferguson MK, Thompson K, Huisingh-Scheetz M, Farnan J, Hemmerich JA, Slawinski K, Acevedo J, Lee SM, Rojnica M, Small S. Thoracic surgeons’ perception of frail behavior in videos of standardized patients. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e98654.

Basic D, Shanley C. Frailty in an older inpatient population: using the clinical frailty scale to predict patient outcomes. J Aging Health. 2015;27(4):670–85.

Bo M, Fonte G, Pivaro F, Bonetto M, Comi C, Giorgis V, Marchese L, Isaia G, Maggiani G, Furno E, Falcone Y. Prevalence of and factors associated with prolonged length of stay in older hospitalized medical patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16(3):314–21.

Bustacchini S, Abbatecola AM, Bonfigli AR, Chiatti C, Corsonello A, Di Stefano G, Galeazzi R, Fabbietti P, Lisa R, Guffanti EE, Provinciali M. The report-AGE project: a permanent epidemiological observatory to identify clinical and biological markers of health outcomes in elderly hospitalized patients in Italy. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2015;27(6):893–901.

El-Sharkawy AM, Watson P, Neal KR, Ljungqvist O, Maughan RJ, Sahota O, Lobo DN. Hydration and outcome in older patients admitted to hospital (the HOOP prospective cohort study). Age Ageing. 2015;44(6):943–7.

Gregersen M, Damsgaard EM, Borris LC. Blood transfusion and risk of infection in frail elderly after hip fracture surgery: the TRIFE randomized controlled trial. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2015;25(6):1031–8.

Heyland D, Cook D, Bagshaw SM, Garland A, Stelfox HT, Mehta S, Dodek P, Kutsogiannis J, Burns K, Muscedere J, Turgeon AF. The very elderly admitted to ICU: a quality finish? Crit Care Med. 2015;43(7):1352–60.

Heyland DK, Garland A, Bagshaw SM, Cook D, Rockwood K, Stelfox HT, Dodek P, Fowler RA, Turgeon AF, Burns K, Muscedere J. Recovery after critical illness in patients aged 80 years or older: a multi-center prospective observational cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(11):1911–20.

Heyland DK, Dodek P, Mehta S, Cook D, Garland A, Stelfox HT, Bagshaw SM, Kutsogiannis DJ, Burns K, Muscedere J, Turgeon AF. Admission of the very elderly to the intensive care unit: family members’ perspectives on clinical decision-making from a multicenter cohort study. Palliat Med. 2015;29(4):324–35.

Hope AA, Gong MN, Guerra C, Wunsch H. Frailty before critical illness and mortality for elderly Medicare beneficiaries. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(6):1121–8.

Housley BC, Stawicki SP, Evans DC, Jones C. Comorbidity-polypharmacy score predicts readmission in older trauma patients. J Surg Res. 2015;199(1):237–43.

Joseph B, Pandit V, Khalil M, Kulvatunyou N, Zangbar B, Friese RS, Mohler MJ, Fain MJ, Rhee P. Managing older adults with ground-level falls admitted to a trauma service: the effect of frailty. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(4):745–9.

Le Maguet P, Roquilly A, Lasocki S, Asehnoune K, Carise E, Saint Martin M, Mimoz O, Le Gac G, Somme D, Cattenoz C, Feuillet F. Prevalence and impact of frailty on mortality in elderly ICU patients: a prospective, multicenter, observational study. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(5):674–82.

Lee J, Sirois MJ, Moore L, Perry J, Daoust R, Griffith L, Worster A, Lang E, Emond M. Return to the ED and hospitalisation following minor injuries among older persons treated in the emergency department: predictors among independent seniors within 6 months. Age Ageing. 2015;44(4):624–9.

Lefebvre MC, St-Onge M, Glazer-Cavanagh M, Bell L, Nguyen JN, Nguyen PV, Tannenbaum C. The effect of bleeding risk and frailty status on anticoagulation patterns in octogenarians with atrial fibrillation: the FRAIL-AF study. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(2):169–76.

Leung DY, Lee DT, Lee IF, Lam LW, Lee SW, Chan MW, Lam YM, Leung SH, Chiu PC, Ho NK, Ip MF. The effect of a virtual ward program on emergency services utilization and quality of life in frail elderly patients after discharge: a pilot study. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:413.

Li Y, Zou Y, Wang S, Li J, Jing X, Yang M, Wang L, Cao L, Yang X, Xu L, Dong B. A pilot study of the FRAIL scale on predicting outcomes in Chinese elderly people with type 2 diabetes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(8):714–e7.

Maxwell CA, Mion LC, Mukherjee K, Dietrich MS, Minnick A, May A, Miller RS. Feasibility of screening for preinjury frailty in hospitalized injured older adults. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78(4):844–51.

Parmar KR, Xiu PY, Chowdhury MR, Patel E, Cohen M. In-hospital treatment and outcomes of heart failure in specialist and non-specialist services: a retrospective cohort study in the elderly. Open heart. 2015;2(1):e000095.

Provencher V, Sirois MJ, Ouellet MC, Camden S, Neveu X, Allain-Boulé N, Emond M. Decline in activities of daily living after a visit to a Canadian emergency department for minor injuries in independent older adults: are frail older adults with cognitive impairment at greater risk? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(5):860–8.

Schultz M, Rosted E, Sanders S. Frailty is associated with a history with more falls in elderly hospitalised patients. Dan Med J. 2015;62(6):A5058.

Uchmanowicz I, Wleklik M, Gobbens RJ. Frailty syndrome and self-care ability in elderly patients with heart failure. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:871.

Uchmanowicz I, Lisiak M, Wontor R, Łoboz-Grudzień K. Frailty in patients with acute coronary syndrome: comparison between tools for comprehensive geriatric assessment and the Tilburg frailty Indicator. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:521.

Wallis SJ, Wall J, Biram RW, Romero-Ortuno R. Association of the clinical frailty scale with hospital outcomes. QJM. 2015;108(12):943–9.

White HD, Westerhout CM, Alexander KP, Roe MT, Winters KJ, Cyr DD, Fox KA, Prabhakaran D, Hochman JS, Armstrong PW, Ohman EM. Frailty is associated with worse outcomes in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: insights from the targeted platelet inhibition to clarify the optimal strategy to medically manage acute coronary syndromes (TRILOGY ACS) trial. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2016;5(3):231–42.

Kistler EA, Nicholas JA, Kates SL, Friedman SM. Frailty and short-term outcomes in patients with hip fracture. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2015;6(3):209–14.

Christodoulidis G, Yu J, Kini A, Dangas GD, Baber U, Melissa A, Sartori S, Theodoropoulos K, Bhat A, Kovacic J, Moreno P. Gender-specific outcomes after balloon aortic valvuloplasty: Inhospital and long-term outcomes. Am Heart J. 2015;170(1):180–6.

Fisher C, Karalapillai DK, Bailey M, Glassford NG, Bellomo R, Jones D. Predicting intensive care and hospital outcome with the Dalhousie Clinical Frailty Scale: a pilot assessment. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2015;43(3):361-8.

Ritt M, Schwarz C, Kronawitter V, Delinic A, Bollheimer LC, Gassmann KG, Sieber CC. Analysis of Rockwood et al’s clinical frailty scale and fried et al’s frailty phenotype as predictors of mortality and other clinical outcomes in older patients who were admitted to a geriatric ward. J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;19(10):1043–8.

Subbe CP, Burford C, Le Jeune I, Masterton-Smith C, Ward D. Relationship between input and output in acute medicine–secondary analysis of the Society for Acute Medicine’s benchmarking audit 2013 (SAMBA ‘13). Clin Med. 2015;15(1):15–9.

Antunes JD, Okuno MF, Lopes MC, Campanharo CR, Batista RE. Frailty assessment of elderly hospitalized at an emergency service of a university hospital. Cogitare Enferm. 2015;20(2):264–71.

Huijberts S, Buurman BM, de Rooij SE. End-of-life care during and after an acute hospitalization in older patients with cancer, end-stage organ failure, or frailty: a sub-analysis of a prospective cohort study. Palliat Med. 2016;30(1):75–82.

Martínez-Velilla N, Casas-Herrero A, Zambom-Ferraresi F, Suárez N, Alonso-Renedo J, Contín KC, de Asteasu ML, Echeverria NF, Lázaro MG, Izquierdo M. Functional and cognitive impairment prevention through early physical activity for geriatric hospitalized patients: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15(1):112.

Brunet NM, Panicot JE, Sevilla-Sánchez D, Novellas JA, Jané CC, Roset JA, Gómez-Batiste X. A patient-centered prescription model assessing the appropriateness of chronic drug therapy in older patients at the end of life. Eur Geriatr Med. 2015;6(6):565–9.

Kenig J, Zychiewicz B, Olszewska U, Barczynski M, Nowak W. Six screening instruments for frailty in older patients qualified for emergency abdominal surgery. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;61(3):437–42.

Gregersen M, Borris LC, Damsgaard EM. Blood transfusion and overall quality of life after hip fracture in frail elderly patients—the transfusion requirements in frail elderly randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(9):762–6.

Gregersen M, Borris LC, Damsgaard EM. Postoperative blood transfusion strategy in frail, anemic elderly patients with hip fracture: the TRIFE randomized controlled trial. Acta Orthop. 2015;86(3):363–72.

Ferguson MK, Thompson K, Huisingh-Scheetz M, Farnan J, Hemmerich J, Acevedo J, Small S. The impact of a frailty education module on surgical resident estimates of lobectomy risk. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100(1):235–41.

Shen Y, Hao Q, Zhou J, Dong B. The impact of frailty and sarcopenia on postoperative outcomes in older patients undergoing gastrectomy surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):188. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0569-2.

Abdullahi YS, Athanasopoulos LV, Casula RP, Moscarelli M, Bagnall M, Ashrafian H, Athanasiou T. Systematic review on the predictive ability of frailty assessment measures in cardiac surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2017;24(4):619–24.