Abstract

Background

Gastric cancer is a major health problem, and frailty and sarcopenia will affect the postoperative outcomes in older people. However, there is still no systematic review to determine the role of frailty and sarcopenia in predicting postoperative outcomes among older patients with gastric cancer who undergo gastrectomy surgery.

Methods

We searched Embase, Medline through the Ovid interface and PubMed websites to identify potential studies. All the search strategies were run on August 24, 2016. We searched the Google website for unpublished studies on June 1, 2017. The data related to the endpoints of gastrectomy surgery were extracted. Odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were pooled to estimate the association between sarcopenia and adverse postoperative outcomes by using Stata version 11.0. PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews were followed.

Results

After screening 500 records, we identified eight studies, including three prospective cohort studies and five retrospective cohort studies. Only one study described frailty, and the remaining seven studies described sarcopenia. Frailty was statistically significant for predicting hospital mortality (OR 3.96; 95% CI: 1.12–14.09, P = 0.03). Sarcopenia was also associated with postoperative outcomes (pooled OR 3.12; 95% CI: 2.23–4.37). No significant heterogeneity was observed across these pooled studies (Chi2 = 3.10, I2 = 0%, P = 0.685).

Conclusion

Sarcopenia and frailty seem to have significant adverse impacts on the occurrence of postoperative outcomes. Well-designed prospective cohort studies focusing on frailty and quality of life with a sufficient sample are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gastric cancer constitutes a major health problem worldwide and is the second most common cause of cancer death [1]. Surgical resection is the main treatment for gastric cancer. Several studies have pointed out that old and young patients carry potential differences in surgery [2, 3]. Older gastric-cancer patients who undergo gastrointestinal surgery may encounter more adverse postoperative outcomes than younger patients [4]. Thus, the need exists to assess the risk of gastrointestinal surgery, especially in older gastric cancer patients.

The prevalence of frailty increases with aging [5]. Frailty is defined as a clinically recognisable state of older adults with increased vulnerability, resulting from age-associated decline in physiological reserve and function across multiple organ systems [5, 6]. Frailty assessment may be a very useful tool for preoperative risk assessment in gastric cancer patients. By assessing frailty, patients can be assigned to undergo either a more tailored individual approach or a standard treatment [5]. Sarcopenia is a syndrome characterised by progressive and generalised loss of skeletal muscle mass and strength [7] and is an important geriatric syndrome closely related to frailty syndrome [8,9,10]. Increasing evidence shows that frailty or sarcopenia is related to the risk of adverse postoperative outcomes, including morbidity, institutionalisation, prolonged length of hospitalisation, and mortality [2, 9, 11]. Therefore, assessment of frailty and sarcopenia is necessary for older gastric-cancer patients potentially undergoing surgery [5, 12,13,14].

However, studies concerning the benefit of assessing frailty and sarcopenia in older patients with gastric cancer undergoing gastric surgery are scarce, and the conclusions are inconsistent [2, 9, 11, 15]. Therefore, we conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis aiming to examine the impact of frailty or sarcopenia on postoperative outcomes in older patients undergoing elective gastrectomy surgery.

Methods

Search strategy

We searched the following electronic databases: (1) MEDLINE (Ovid, 1946 to August 24, 2016); (2) EMBASE (Ovid, 1974 to August 24, 2016). We used medical subject headings (MeSH) or equivalent and text word terms for MEDLINE and adaptations of the search strategy for EMBASE. We also searched the PubMed web version on August 24, 2016 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), and Google website (www.google.com) for unpublished studies on June 1, 2017. As mentioned in the methodology specified under the PRISMA guidelines (www.prisma-statement.org), two researchers (YJS and JHZ), in collaboration with a medical librarian, performed a systematic search. The following keywords were used for the search: gastric cancer, aged, frailty, sarcopenia, geriatric assessment, postoperative complications and postoperative outcomes. The search string is included in detail in the Additional file 1. We tailored searches to individual databases. The search was completed on August 24, 2016, and animal restriction was applied. In addition, the reference lists of the selected articles were also reviewed to identify relevant articles.

Study selection

Studies were eligible if they reported postoperative outcomes in older patients with gastric cancer in relation to frailty or sarcopenia profile. We included both retrospective and prospective cohort studies, which described clinical trials in which patients, with an average age of 60 years and older, underwent elective gastric surgery for gastric cancer and were categorised into frail or sarcopenic and non-frail or non-sarcopenic groups. In addition, the criteria used to categorise the patients into frail or sarcopenic groups had to be clearly reported, and frailty or sarcopenia had to be determined in a clinical setting. Studies were excluded if they did not examine postoperative outcomes or surgical complications such as wound infection, anastomotic leakage or mortality as endpoints.

The titles and abstracts of the articles were screened by two investigators (YJS and JHZ). Whenever an article was considered relevant, we reviewed the full text. Finally, to identify potentially eligible studies, we also reviewed all the references in lists of the included studies. We resolved disagreements by discussion to reach a consensus with a third review author (BRD).

Data charting

One reviewer (YJS) extracted the following data from the included studies: first author, study population, study design, sample size, age of the participants (mean age and standard deviation, if reported), year of publication, country and period of enrolment and inclusion and exclusion criteria of the study. Another reviewer (JHZ) independently double-checked this process. We extracted data regarding the targeted endpoints of this review: criteria and prevalence of frailty and sarcopenia and postoperative outcomes in relation to frailty and sarcopenia groups. If the data in the original manuscript was insufficient, the corresponding author was contacted for additional information.

Critical appraisal

Reviewers YJS and JHZ independently assessed the methodological quality of the included studies by the Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS). For non-comparative studies, this instrument consists of the following eight items: (1) a clearly stated aim, (2) inclusion of consecutive patients, (3) prospective collection of data, (4) endpoints appropriate to the aim of the study, (5) unbiased assessment of the study endpoint, (6) follow-up period appropriate to the aim of the study, (7) loss to follow-up less than 5% and (8) prospective calculation of the study size. If the information is not reported, an item is scored 0 points; if the information is reported but inadequate, it scores 1 point; if the information is reported and adequate, it scores 2 points. The ideal score is 16 for non-comparative studies. During a consensus meeting, disagreement among the reviewers was discussed with a third reviewer (BRD).

Statistical analysis

If there was no available data to extract and pool, we described the outcomes in our review. The summary odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the included studies were used as measures to assess the association of sarcopenia with postoperative complications. We measured heterogeneity by using the chi2 test with significance set at P < 0.1. The I2 is also computed; it is a quantitative measure of inconsistency across studies. The following is a rough guide to interpretation of I2: 0% to 30% might not be important; 30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity; 60% to 75% may represent substantial heterogeneity; 75% to 100% represents considerable heterogeneity. Clinically, there is heterogeneity because of the different evaluation methods of sarcopenia and follow-up time. In consideration of the presence of clinical heterogeneity, we used the random-effects model to synthesise all data, regardless of heterogeneity between the pooled studies in statistical order to obtain more conservative results. Publication bias was assessed by visually inspecting the funnel plots and Egger’s and Begg’s tests (P < 0.10). Subgroup analysis was conducted according to different designs of included studies. Sensitivity analysis was performed by omitting each study or included studies with lower quality. The STATA version 11.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA) was used to perform all of the analyses. If a P value was <0.05, it was statistically significant unless otherwise specified.

Results

Selected studies

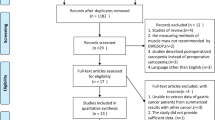

The search strategy yielded 500 records (Fig. 1), of which 468 after duplications were excluded. After screening the titles and abstracts of the 468 records, 22 articles were assessed for eligibility. Of these articles, 12 of them were conference studies. After reading the remaining 10 full texts, three articles were excluded. One study contained no gastric cancer groups [16]; another study contained no assessment of frailty or sarcopenia [17]; and in one study, sarcopenia was not assessed in a clinical and reliable way, and the outcomes in relation to sarcopenia were not examined [18]. Cross-referencing yielded one additional study [19]. In total, eight studies were included in this systematic review [15, 19,20,21,22,23,24,25].

Study and patient characteristics

In the eight included studies, three studies were prospective observational cohort studies [19, 22, 23], and five studies were retrospective observational cohort studies [15, 20, 21, 24, 25]. The studies were performed from 2005 to 2016 in the Netherlands [15, 20], Japan [21, 22, 25] and China [19, 23, 24]. Five studies described multiple outcomes, including postoperative complications, morbidity, length of stay, a 6-month mortality and in-hospital mortality, hospital costs, 30-day readmission, overall survival and disease-free survival [15, 20,21,22,23,24]. One study focused on surgical site infection [25], and two studies focused on short-term outcomes [19, 23]. The sample size of one study was small (n = 99), and the average age of the participants in this study was over 65 years of age [22]. The average age of patients in the remaining seven studies was over 60 years [15, 19,20,21, 23,24,25]. The characteristics of the included studies are summarised in Table 1.

Quality assessment

The quality assessments of the eight included articles [15, 19,20,21,22,23,24,25] are summarised in Table 2. Scores ranged from 13 to 16 with a median value of 14. Every study had collected data retrospectively or prospectively and had included patients consecutively. The follow-up period was appropriate in every study, with a loss to follow-up of less than 5% for all of the studies. Endpoints appropriate to the aim of the study and the prospective calculation of the study endpoint were not reported or reported but inadequate in some of the studies. Furthermore, the unbiased assessment for the study endpoint was not always clear.

Frailty and sarcopenia criteria, groups and prevalence

Only one study described frailty; the remaining seven studies described sarcopenia. One study performed the Groningen Frailty Indicator (GFI) to identify frailty [20]. The prevalence of frailty was 23.62% in the included study.

Two studies used the algorithm of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older Persons (EWGSOP) [15, 22]; another two studies used the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS) and EWGSOP [19, 23]. Patients were considered to have sarcopenia if they met a value that was calculated by the sum of low muscle mass plus low muscle strength and/or low physical performance; then the patients were divided into sarcopenia/non-sarcopenia patients. Although these studies used EWGSOP and AWGS, the cut-off value is different (as shown in Table 3). In addition, one study determined sarcopenia by scoring hand-grip strength [21]. Two studies (Zhuang, CL et al. [24] and Nishigori, T et al. [25]) determined sarcopenia by Assessment Skeletal Muscle Mass, but the cut-off value was different between them, as shown in Table 3. The subjects in our included studies were hospitalised patients with a mean age over 60 years old, and the prevalence of sarcopenia ranged from 12.5% [23] to 57.7% [15].

Frailty or sarcopenia and postoperative outcomes

The outcomes reported in all included studies in relation to frailty or sarcopenia were in-hospital mortality [20], postoperative complications [19, 21,22,23,24,25], serious adverse events [20, 22, 24], hospital costs [23], overall survival [24], disease-free survival [24] and surgical site infection [25]. The postoperative complications of the studies were classified into different severity grades by using a well-described classification system (Clavien–Dindo, 2004) [26]. The classification systems used are summarised in Table 4.

One study (Tegels, JJ et al.) [20] used GFI ≥3 to define frailty, and the results show a significant relationship between frailty and surgical mortality in gastric cancer (OR 3.96; 95% CI: 1.12 to 14.09, P = 0.03). This study also explored the relationship between frailty and serious adverse events, length of stay, and 6-month mortality. In this study, frailty was associated with increased risk of serious adverse events (defined as Clavien–Dindo grade 3a or over); however, frailty did not correlate with either increased 6-month mortality or increased length of stay.

Six studies reported the association between sarcopenia and postoperative complications. We calculated the summary OR values using random-effects models; the pooled OR of gastric cancer from the combination of included studies was 3.12 (95% CI: 2.23–4.37) for postoperative outcome (Fig. 2). This indicated that sarcopenia was an independent risk factor for severe postoperative complications. No significant heterogeneity was observed across these pooled studies (Chi2 = 3.10, df = 5, I2 = 0%, P = 0.685) (Fig. 3) [19, 21,22,23,24,25].

Publication bias

Begg’s and Egger’s tests were performed to assess the publication bias in these studies. The results did not show any statistical significance for publication bias (Begg’s test: p = 0.851; Egger’s test: p = 0.840). Furthermore, the shape of the funnel plot did not reveal any evidence of obvious asymmetry (Fig. 3).

Subgroup and sensitivity analysis

We conducted the subgroup analysis according to the study design (prospective and retrospective studies); the statistical significance was not changed by this subgroup analysis (prospective studies: OR 3.12, 95% CI (2.23, 4.37), I = 0%, P value for heterogeneity 0.684; and retrospective studies: OR 2.65, 95% CI (1.72, 4.09), I = 0%, P value for heterogeneity was 0.617). We performed sensitivity analysis by omitting every single study and two low quality studies of the included studies [15, 20] (quality score); the statistical significance of the results were still not changed (data not shown).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to explore systematically the impact of frailty and sarcopenia in predicting outcomes among older patients undergoing gastrectomy surgery. Although only one included study focused on frailty and gastrectomy surgery in this review, frailty was still a statistically significant factor for predicting surgical mortality in the older patient (OR 3.96, 95% CI 1.12–14.09). There was also a significant relationship between sarcopenia and postoperative complications (OR 3.12, 95% CI: 2.23–4.37) in older people. Our study indicated that assessing frailty and sarcopenia is important among older patients undergoing gastrectomy surgery.

The prevalence of sarcopenia ranged from 5% to 13% for older people aged 60 to 70 years and ranged from 11% to 50% for people aged 80 and older [27, 28]. The prevalence of sarcopenia among patients with gastric cancer has been reported to be as high as 38% [9]. In this systematic review, the prevalence of sarcopenia ranged from 12.5% [23] to 57.7% [15]. The difference in this prevalence can be explained by patients with gastric cancer being at a particularly high risk of sarcopenia and the different diagnostic criteria used in different studies. Even though these criteria had been established long ago, uniform criteria are still not established. Thus, different cut-off points for muscle mass and muscle strength were used in different studies (Table 3). In the present study, the EWGSOP and AWGS algorithm, hand grip strength (kg) and skeletal muscle mass were considered suitable methods for the diagnosis of sarcopenia. This may be for reasons of clinical heterogeneity.

Previous studies showed that the state of frailty and sarcopenia in the preoperative period were related to the occurrence of adverse postoperative outcomes, including morbidity, mortality, institutionalisation and prolonged length of hospitalisation [2, 9, 11]. Recently, Doris Wagner and colleagues [9] performed a systematic review regarding the role of frailty and sarcopenia in predicting outcomes among patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery. However, this review included not only gastrectomy surgery, but also gastroesophageal surgery, colorectal surgery and hepatopancreaticobiliary surgery. Because of the high level of heterogeneity, the authors did not do meta-analysis. Furthermore, they limited their search date to January 2000 to March 2015 and only considered studies published in English. Therefore, our systematic review and meta-analysis focuses on gastrectomy surgery to reduce some of the clinical heterogeneity, giving us an opportunity to conduct the meta-analysis in this review. To the best of our knowledge, there was no systematic review that reported the role of sarcopenia in predicting morbidity and mortality of patients undergoing gastric surgery. Another systematic review conducted by Kathleen Fagard and colleagues [29] suggested that frailty is associated with a greater risk of postoperative adverse outcomes in patients with colorectal cancer. Our study found frailty had a predictive capacity for in-hospital mortality [20] and serious adverse events [20], but not for 6-month mortality and length of stay [20]. Sarcopenia is associated with mortality [21], postoperative complications [19, 21,22,23,24], hospital costs [23], postoperative hospital stay [23], overall survival [24] and disease-free survival [24].

Our results must be interpreted with caution due to the following limitations. First, although we conducted subgroup and sensitivity analyses according to the design and quality of the included studies, we did not perform the subgroup analyses according to the different sarcopenia criteria. All these factors may cause heterogeneity. Second, even frailty and sarcopenia are common in the elderly, the included criteria of our review was based on the average age of 60 years or more. However, two included studies might have included some participants younger than 60 years, which may cause some bias. Third, whether our results can be applied to Western populations remains unknown because all the included studies were from Asian countries. Fourth, none of the included studies reported quality of life as a primary outcome. Therefore, future studies should focus on more patient-centred outcomes such as quality of life. Fifth, only one study focused on the frailty assessment in predicting postoperative complications in gastric cancer surgery. However, frailty is a very important geriatric syndrome in older people. Therefore, future studies focusing on frailty and postoperative complications in gastric cancer are needed.

Conclusion

Sarcopenia and frailty seem to have a significant impact on the occurrence of adverse postoperative outcomes. Thus, it is important to define whether a patient with gastric cancer has sarcopenia and is frail in the perioperative period. Further well-designed, prospective, cohort studies focusing on frailty and quality of life with sufficient samples are needed.

Abbreviations

- ASM:

-

appendicular skeletal muscle mass

- BIA:

-

bioimpedance analysis

- ECOG:

-

Eastern cooperative oncology group

- EWGSOP:

-

European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older Persons

- GFI:

-

Groningen frailty indicator

- GSL:

-

gender-specific lowest 20th percentile

- HGS:

-

hand grip strength

- HR:

-

hazards ratio

- LTG:

-

laparoscopic total gastrectomy

- NR:

-

not reported

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- SD:

-

standard deviation

- SMI:

-

skeletal muscle index

References

Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2095–128.

McCleary NJ, Dotan E, Browner I. Refining the chemotherapy approach for older patients with colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(24):2570–80.

Pujara D, Mansfield P, Ajani J, Blum M, Elimova E, Chiang YJ, Das P, Badgwell B. Comprehensive geriatric assessment in patients with gastric and gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma undergoing gastrectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2015;112(8):883–7.

Partridge JS, Harari D, Dhesi JK. Frailty in the older surgical patient: a review. Age Ageing. 2012;41(2):142–7.

Chen X, Mao G, Leng SX. Frailty syndrome: an overview. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:433–41.

Clegg A, Rogers L, Young J. Diagnostic test accuracy of simple instruments for identifying frailty in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2015;44(1):148–52.

Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, Boirie Y, Cederholm T, Landi F, Martin FC, Michel JP, Rolland Y, Schneider SM, et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: report of the European working group on sarcopenia in older people. Age Ageing. 2010;39(4):412–23.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–56.

Wagner D, DeMarco MM, Amini N, Buttner S, Segev D, Gani F, Pawlik TM. Role of frailty and sarcopenia in predicting outcomes among patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery. World J Gastrointes Surg. 2016;8(1):27–40.

Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Kiesswetter E, Drey M, Sieber CC. Nutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2017;29(1):43–8.

Robinson TN, Eiseman B, Wallace JI, Church SD, McFann KK, Pfister SM, Sharp TJ, Moss M. Redefining geriatric preoperative assessment using frailty, disability and co-morbidity. Ann Surg. 2009;250(3):449–55.

Beggs T, Sepehri A, Szwajcer A, Tangri N, Arora RC. Frailty and perioperative outcomes: a narrative review. Can J Anaesth. 2015;62(2):143–57.

Dasgupta M, Rolfson DB, Stolee P, Borrie MJ, Speechley M. Frailty is associated with postoperative complications in older adults with medical problems. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;48(1):78–83.

Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ, Syin D, Bandeen-Roche K, Patel P, Takenaga R, Devgan L, Holzmueller CG, Tian J, et al. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(6):901–8.

Tegels JJW, van Vugt JLA, Reisinger KW, Hulsewe KWE, Hoofwijk AGM, Derikx JPM, Stoot JHMB. Sarcopenia is highly prevalent in patients undergoing surgery for gastric cancer but not associated with worse outcomes. J Surg Oncol. 2015;112(4):403–7.

Tamandl D, Paireder M, Asari R, Baltzer PA, Schoppmann SF, Ba-Ssalamah A. Markers of sarcopenia quantified by computed tomography predict adverse long-term outcome in patients with resected oesophageal or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer. Eur Radiol. 2016;26(5):1359–67.

Pujara D, Mansfield P, Ajani J, Blum M, Elimova E, Chiang Y-J, Das P, Badgwell B. Comprehensive geriatric assessment in patients with gastric and gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma undergoing gastrectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2015;112(8):883–7.

Tan BH, Brammer K, Randhawa N, Welch NT, Parsons SL, James EJ, Catton JA. Sarcopenia is associated with toxicity in patients undergoing neo-adjuvant chemotherapy for oesophago-gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(3):333–8.

Chen FF, Zhang FY, Zhou XY, Shen X, Yu Z, Zhuang CL. Role of frailty and nutritional status in predicting complications following total gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy in patients with gastric cancer: a prospective study. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2016;401(6):813–22. doi:10.1007/s00423-016-1490-4. Epub 2016 Aug 2.

Tegels JJ, de Maat MF, Hulsewe KW, Hoofwijk AG, Stoot JH. Value of geriatric frailty and nutritional status assessment in predicting postoperative mortality in gastric cancer surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18(3):439–45. discussion 445-436

Sato T, Aoyama T, Hayashi T, Segami K, Kawabe T, Fujikawa H, Yamada T, Yamamoto N, Oshima T, Rino Y, et al. Impact of preoperative hand grip strength on morbidity following gastric cancer surgery. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19(3):1008–15.

Fukuda Y, Yamamoto K, Hirao M, Nishikawa K, Nagatsuma Y, Nakayama T, Tanikawa S, Maeda S, Uemura M, Miyake M, et al. Sarcopenia is associated with severe postoperative complications in elderly gastric cancer patients undergoing gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19(3):986–93.

Wang S-L, Zhuang C-L, Huang D-D, Pang W-Y, Lou N, Chen F-F, Zhou C-J, Shen X, Yu Z. Sarcopenia adversely impacts postoperative clinical outcomes following Gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer: a prospective study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(2):556–64.

Zhuang CL, Huang DD, Pang WY, Zhou CJ, Wang SL, Lou N, Ma LL, Yu Z, Shen X. Sarcopenia is an independent predictor of severe postoperative complications and long-term survival after radical Gastrectomy for gastric cancer: analysis from a large-scale cohort. Medicine. 2016;95(13):e3164.

Nishigori T, Tsunoda S, Okabe H, Tanaka E, Hisamori S, Hosogi H, Shinohara H, Sakai Y. Impact of Sarcopenic Obesity on Surgical Site Infection after Laparoscopic Total Gastrectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(Suppl 4):524–531. Epub 2016 Jul 5.

Schuurmans H, Steverink N, Lindenberg S, Frieswijk N, Slaets JP. Old or frail: what tells us more? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(9):M962–M965.

Fielding RA, Vellas B, Evans WJ, Bhasin S, Morley JE, Newman AB, Abellan van Kan G, Andrieu S, Bauer J, Breuille D, et al. Sarcopenia: an undiagnosed condition in older adults. Current consensus definition: prevalence, etiology, and consequences. International working group on sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12(4):249–56.

von Haehling S, Morley JE, Anker SD. An overview of sarcopenia: facts and numbers on prevalence and clinical impact. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2010;1(2):129–33.

Fagard K, Leonard S, Deschodt M, Devriendt E, Wolthuis A, Prenen H, Flamaing J, Milisen K, Wildiers H, Kenis C: The impact of frailty on postoperative outcomes in individuals aged 65 and over undergoing elective surgery for colorectal cancer: A systematic review. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(6):479–91. doi:10.1016/j.jgo.2016.06.001.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Valerie Tanner, Saint Louis University Geriatrics Division, in St. Louis, USA, for her editing and English review expertise of the manuscript. We also want to thank Yang Ying for her contribution in the preparation of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the Collaborative Innovation Center of Sichuan for Elderly Care and Health of China (Grant No. YLZBZ1503): To Construct a model based on frailty index to predict operative risks for hospitalized elderly with geriatric comorbidity.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files .

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept: YJS and QKH. Study design: YJS and QKH. Data acquisition: YJS and JHZ. Quality control of data and algorithms: BRD and QKH. Data analysis and interpretation: QKH and YJS. Manuscript preparation: YJS. Manuscript editing: YJS and QKH. Manuscript review: QKH and BRD. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

MEDLINE search strategy. (DOCX 12 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, Y., Hao, Q., Zhou, J. et al. The impact of frailty and sarcopenia on postoperative outcomes in older patients undergoing gastrectomy surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr 17, 188 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0569-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0569-2