Abstract

Background

Qualitative pathogen resistance in both dicotyledenous and monocotyledonous plants has been attributed to the action of resistance (R) genes, including those encoding nucleotide binding site – leucine rich repeat (NBS-LRR) proteins and receptor-like kinase enzymes. This study describes the large-scale isolation and characterisation of candidate R genes from perennial ryegrass. The analysis was based on the availability of an expressed sequence tag (EST) resource and a functionally-integrated bioinformatics database.

Results

Amplification of R gene sequences was performed using template EST data and information from orthologous candidate using a degenerate consensus PCR approach. A total of 102 unique partial R genes were cloned, sequenced and functionally annotated. Analysis of motif structure and R gene phylogeny demonstrated that Lolium R genes cluster with putative ortholoci, and evolved from common ancestral origins. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) predicted through resequencing of amplicons from the parental genotypes of a genetic mapping family were validated, and 26 distinct R gene loci were assigned to multiple genetic maps. Clusters of largely non-related NBS-LRR genes were located at multiple distinct genomic locations and were commonly found in close proximity to previously mapped defence response (DR) genes. A comparative genomics analysis revealed the co-location of several candidate R genes with disease resistance quantitative trait loci (QTLs).

Conclusion

This study is the most comprehensive analysis to date of qualitative disease resistance candidate genes in perennial ryegrass. SNPs identified within candidate genes provide a valuable resource for mapping in various ryegrass pair cross-derived populations and further germplasm analysis using association genetics. In parallel with the use of specific pathogen virulence races, such resources provide the means to identify gene-for-gene mechanisms for multiple host pathogen-interactions and ultimately to obtain durable field-based resistance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) is the most widely cultivated forage, turf and amenity grass species of global temperate grazing zones. Favourable agronomic qualities include high dry matter yield, nutritive content, digestibility, palatability and the ability to recover from heavy defoliation by herbivores [1, 2]. Perennial ryegrass is, however, susceptible to a number of different foliar diseases. Crown rust (Puccinia coronata f.sp. lolii) is the most widespread and damaging disease affecting ryegrasses [3–7]. Stem rust (P. graminis f.sp. lolii) infections are especially serious for producers of ryegrass seed [8], while grey leaf spot (Magnaporthe grisea), dollar spot (Sclerotinia homoeocarpa) and brown patch (Rhizoctonia solani) reduce turf quality [9]. The development of cultivars resistant to each of these diseases is currently recognised as an important mode of infection control.

The obligate outbreeding reproductive habit of perennial ryegrass [10] leads to high levels of genetic variation within, and to a lesser extent, between cultivars [11–13]. Conventional breeding for disease resistance is hence anticipated to be relatively slow for outcrossing forage species as compared to allogamous species such as cereals, because of a requirement for extensive progeny screening and phenotyping. Nonetheless, major genes and quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for disease resistance have been detected in Lolium species for resistance to crown rust [14–21], stem rust [22], bacterial wilt [23], powdery mildew [24] and grey leaf spot [25]. The extent of genetic variation within temperate Australasian crown rust pathogen populations [26] is consistent with the presence of different virulence races [27]. Identification of the molecular basis of major resistance determinants to different pathotypes will improve selection of favourable alleles during cultivar development.

Both genetic and physiological analysis has determined that hypersensitive reactions in response to fungal, viral and bacterial pathogen infections are caused by the action of genes encoding receptor proteins [28, 29]. The major class of resistance (R) genes contain a highly conserved nucleotide binding site (NBS) domain adjacent to the N-terminus and a leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain involved in the host recognition of pathogen-derived elicitors. NBS-LRRs constitute one of the largest plant gene families, accounting for c. 1% of all open reading frames (ORFs) in both rice and Arabidopsis thaliana, and are distributed non-randomly throughout the genome [30–32]. Clustering of R genes is known to facilitate tandem duplication of paralogous sequences and generation of new resistance specificities to counter novel avirulence determinants in evolving pathogen populations [30–34].

NBS domain-containing sequences have been isolated using degenerate PCR from many agronomically-important Poaceae species including cereals [33–37] and forage grasses [24, 38, 39]. In a comparison with the fully-sequenced rice genome [31], only a small proportion of the total NBS domain sequences are so far likely to have been isolated from Lolium species. Multiple strategies are hence required to isolate a larger R gene sample, allowing for structural characterisation, marker development for genetic mapping, and the potential for correlation with the locations of known disease resistance loci.

Disease resistance loci of cereal species are conserved at the chromosomal and molecular level [40, 41], and provide valuable template genes for a translational genomic approach to molecular marker development [42]. For example, the TaLrk10 receptor kinase gene (located at the Lr10 locus on hexaploid wheat chromosome 1AS) has been found to confer resistance to leaf rust in specific cultivars, and putative Lrk10 ortholoci are structurally conserved between Poaceae species [41, 43]. The Lrk10 orthologue of cultivated oat (Avena sativa L.) exhibits 76% nucleotide similarity to the wheat gene and maps in a region of conserved synteny between the two genomes, co-locating with a large cluster of NBS-LRR genes conferring resistance to the oat form of crown rust (P. coronata f.sp. avenae) [41]. The Poaceae sub-family Pooideae includes perennial ryegrass, along with cereals of the Aveneae and Triticeae tribes [44, 45], suggesting that template genes from these species are highly suitable for ortholocus isolation.

Based on studies of cereal-pathogen interactions, similar qualitative and quantitative genetic mechanisms are likely to contribute to disease resistance in perennial ryegrass. In order to test this hypothesis, a broad survey based on empirical and computational approaches was conducted to recover an enhanced proportion of perennial ryegrass NBS domain-containing sequences, as well as specific R gene ortholoci. Candidate R gene sequences (referred to as R genes throughout the text) were characterised by functional annotation, motif structure classification and phylogenetic analysis. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were discovered through re-sequencing of haplotypes from the parents of a two-way pseudo-testcross mapping population and validated SNPs were assigned to genetic maps. Co-location with disease resistance QTLs was demonstrated within Lolium taxa and by comparative analysis with related Poaceae species.

Methods

Bioinformatic approach to template gene selection

A proprietary resource of c. 50,000 perennial ryegrass expressed sequence tags (ESTs) [46] was integrated into the Bioinformatic Advanced Scientific Computing (BASC) system [47]. Each EST was functionally annotated using data from microarray-based transcriptomics experiments, the rice Ensembl browser, Pfam and gene ontology databases. BASC was used to search for the presence of NBS-LRR sequences. A text search with the query terms 'disease' and 'resistance' was used to identify candidates based on a wuBLASTX threshold of E = 10-15 through known gene ontology within the genomes of closely-related cereal species (wheat, oat and barley), rice and Arabidopsis.

Primer design for candidate Lolium R genes

Locus amplification primers (LAPs) for multiple target genes were designed using standard parameters as previously described [48]. LAPs were designed from perennial ryegrass EST templates, and sequence tagged site (STS) primers derived from Italian ryegrass (L. multiflorum Lam.) NBS sequences located in GenBank [39].

Primer design based on Pooideae R gene templates

LAPs were designed based on the sequence of four oat LGB-located Pca cluster R genes [37], five barley rust resistance genes (Hvs-18, Hvs-133-2, Hvs-T65, Hvs-236 and Hvs-L6) [33]; and the third exon and 3'-terminus of the TaLrk10 extracellular domain [41].

Degenerate primer design

Degenerate primers (4 in sense and 12 in antisense orientation) were designed to the conserved regions (P-loop and GLPL) of cloned oat R genes [37] and were used in conjunction with published R gene-specific degenerate primers [33, 34, 38, 49] (Additional File 1). Based on interpretation of initial amplicon complexity, specific primers were subsequently designed for SNP discovery.

Amplicon cloning and sequencing

For specific homologous and heterologous R gene-derived primers, PCR amplicons were generated using template genomic DNA from the parental genotypes of the F1(NA6 × AU6) mapping population [48, 50]. For degenerate primers, genomic DNA from the crown rust resistant Vedette6 genotype [14] was used as an primary template, and re-designed primer pairs were used with the F1(NA6 × AU6) parents. Amplicons were cloned and sequenced essentially as previously described [48], except that a total of 32 Vedette6 clones and 12 clones from each of NA6 and AU6 were analysed. Trace sequence files were used as input materials into the BASC module ESTdB [47].

Classification of derived sequences

All candidate NBS-LRR (R gene) nucleotide sequences were subjected to two-way BLASTX and wuBLASTX analysis against the GenBank and the Uniprot databases, respectively. Genomic DNA sequences were translated to amino acid sequences using Transeq software. Each peptide sequence was scanned against the Pfam database [51, 52] for the presence of known domains, the type, size and position of NBS domains and the number of LRR repeats. Multiple Expectation Maximisation for Motif Elicitation (MEME) [53] was used to detect conserved motifs between sequences containing NBS domains [34].

Phylogenetic analysis of R gene sequences

Preliminary alignments of predicted protein sequences was performed manually using Bioedit (version 7.0.5.3 – Ibis Biosciences, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The alignments were split into two separate datasets (for the P-Loop to GLPL region, and for the Kin-2A to GLPL region), and were realigned for phylogenetic analysis using CLUSTALX [54] with default options. Clustering of related sequences based on amino acid homology was conducted using a Neighbour Joining (NJ) algorithm and bootstrap analysis was calculated on an unrooted NJ cladogram based on 1000 iterations using CLUSTALX [55].

Plant materials

Perennial ryegrass genomic DNA was extracted from parents and progeny of the F1(NA6 × AU6), Vedette6 and p150/112 [45, 56] mapping families using the CTAB method [57]. A genotypic panel for genetic map assignment was constructed of 141 F1(NA6 × AU6) and 24 p150/112 F1 genotypes as previously described [21].

In vitrodiscovery, validation and mapping of gene-associated SNPs

PCR-amplified genomic amplicons were cloned and sequenced and DNA sequences were aligned essentially as previously described [48]. Predicted SNPs were initially validated using 10 F1(NA6 × AU6) individuals, and those showing Mendelian segregation were then genotyped across the full mapping panel through the single nucleotide primer extension (SNuPe) assay [48]. Integration of SNP loci into the existing F1(NA6 × AU6) parental genetic maps was performed as previously described [21, 48, 50].

Comparative genetic mapping

Comparison of chromosomal regions controlling crown rust resistance between perennial ryegrass trait-specific mapping populations was performed using data from QTL analysis of the F1(SB2 × TC1) mapping population [17]. The F1(SB2 × TC1) parental maps contained heterologous RFLP and genomic DNA-derived SSR (LPSSR) markers shared with the p150/112 and F1(NA6 × AU6) genetic maps, respectively [45, 56]. Comparison of marker locus order between the p150/112 and F1(NA6 × AU6) genetic maps was performed through the presence of common LPSSR loci [50, 56]. This common marker set also allowed interpolation of the position of the LpPc1 crown rust resistance locus on p150/112 LG2 [14]. Chromosomal locations of LrK10 ortholoci were compared between Lolium and Avena species using common heterologous RFLP loci [58]. Further comparative genomic analysis was conducted using published genetic maps from cereal species including barley, wheat, rye and oat [33, 59].

Results

Strategies for specific R gene isolation

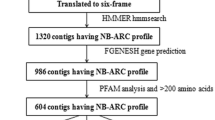

Three strategies (empirical approaches based on heterologous PCR and degenerate PCR, and a bioinformatic discovery method) resulted in the identification of 67 primary R gene templates for host genetic analysis (Table 1). Initial PCR amplification and resequencing using the parental genotypes of the F1(NA6 × AU6) mapping population allowed identification of a further 35 secondary R gene template sequences (Additional File 2). A total of 14 primer pairs amplified paralogous sequences, at a mean of 2.5 per primary template sequence, with a range from 1–12. A total of 102 distinct putative R gene sequences (corresponding to 99 NBS-containing genes and 3 receptor kinase genes) were annotated (Additional File 2) and subjected to further characterisation. Representative genomic sequence haplotypes were deposited as accessions for unrestricted access in GenBank (accession numbers FI856066–FI856167). A schematic summary of the candidate gene discovery process and further applications is depicted in Figure 1.

In the empirical approach category, translational genomics between perennial ryegrass and closely related cereal species (oat, barley and wheat) which are susceptible to other Puccinia rust pathogens (P. coronata f. sp. avenae, P. hordii, P. triticina) was used to identify R genes. Perennial ryegrass amplicons derived from oat R gene template primer pairs demonstrated high BLASTX similarity matches to their corresponding template sequences (data not shown). Primer pairs designed to the TaLrk10 template generated two 1.6 kb fragments, one of which (LpLrk10.1) displayed very high similarity scores to the putative oat ortholocus (AsPc68LrkA).

The specificity of amplification using degenerate primers designed to amplify NBS domains was dependent on the proportion of deoxyinosine (I)-containing nucleotides. Those based on oat R gene templates contained a high frequency of inosines (>15%) and predominantly amplified retrotransposon-like sequences (data not shown). In contrast, combinations of largely non-degenerate primer pairs based on sequence information from multiple Poaceae species (barley, sorghum and ryegrass) (Additional File 1), successfully generated NBS domain-containing amplicons of the correct size (Additional File 3). A total of 28 distinct NBS domain-containing sequences (Tables 1, Additional File 2) were generated, several primer pairs generating multiple products (up to 7) (Additional File 3).

The text search-based computational approach identified 23 distinct perennial ryegrass ESTs with high sequence similarity to known resistance genes from closely-related species (Table 1, Additional File 2). Amplification based on candidate EST primary templates was efficient, with only 13% of LAP pairs failing to generate amplicons. Additional sequences were amplified from several ESTs, all were putative paralogues showing significant BLASTX similarity (E < 1 × 10-15) to known R genes (Additional File 2).

Database searches for previously-characterised ryegrass NBS sequences identified 51 accessions from Italian ryegrass-derived clones and a further 14 from an interspecific L. perenne × L. multiflorum hybrid (L. x. boucheanum). All 6 previously-described STS primer pairs successfully generated single amplicons of the expected size (Table 1, Additional File 2).

Molecular characterisation of perennial ryegrass R genes

From the total of 102 analysed sequences, 89 (87%) exhibited BLASTX matches at E < 10-20 to known NBS domain-containing sequences from closely-related cereal species in both the GenBank and UniProt databases (Additional File 2). In most cases (80%), the highest matching sequence was the same for both databases. Sequence translation and subsequent Pfam analysis revealed that a substantial proportion of partial protein sequences were similar to the NBS domain (Additional File 4). A large proportion of the NBS-category sequences (55%) were within the NBS domain, while the remaining sequences either overlapped the NBS region at the N- or C- terminus, contained the LRR domain, or were located solely within the N- or C- terminal domain. A range of different R gene sub-classes containing NBS, CC-NBS, NBS-LRR, NBS-NBS-LRR, CC-NBS-LRR, CC-CC-NBS-LRR and NBS-NBS domains were detected, but no TIR-NBS containing sequences were observed. Of the different sub-classes of NBS sequences, 52 contained 1–33 LRRs (modal at 3), 25 contained 1 or more CC domains, and five sequences contained the NBS-NBS domain (Additional File 4). A further three receptor kinase and NBS-LRR genes contained trans-membrane domains.

Consensuses were determined for the seven major NBS domain motifs (P-Loop, RNBS-I, Kin-2A, RNBS-II, RNBS-III, GLPL and RNBS-V) (Additional File 5) and were compared to those from closely related Poaceae species (wheat and rice) and to A. thaliana. The P-Loop, Kin-2A and GLPL motifs were most highly conserved between all species examined, while the RNBS-I and RNBS-II motifs were conserved within the Poaceae, and the Kin-2A and RNBS-II motifs were the most conserved among the CC-NBS sequences. The RNBS-III and RNBS-V motifs were highly divergent between all species.

A total of 50 different motif signatures were identified by MEME analysis with 60 NBS domain-containing sequences at an average of 13 residues in length. The most commonly occurring signatures were components of the conserved regions such as the P-Loop, Kin-2A and GLPL motifs (Fig. 2, Additional File 6). All the distinct sub-classes of NBS sequences present either completely lacked, or contained highly variable RNBS regions. Structural analysis revealed substantial diversity in motif content within the NBS domain and grouping of specific motifs into sub-classes based on shared sequence origin.

Representation of motif patterns in the NBS domain of perennial ryegrass R gene sequences. Different coloured boxes and numbers indicate distinct motifs identified by the MEME program which are displayed using the MAST application (details provided in Additional File 6).

Phylogenetic analysis of perennial ryegrass R genes

Phylogenetic analysis was performed based on two selected NBS domain regions (P-Loop-GLPL and Kin-2A-GLPL). Unrelated NBS domain sequences from A. thaliana, lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.), flax (Linum usitatissimum L.), tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.) oat, rice and barley were included for both regions, as were GenBank-derived Lolium NBS sequences. A total of 38 P-Loop-GLPL sequences and 104 Kin-2A-GLPL sequences were analysed. Amino acid alignment of NBS regions permitted classification into sub-families or classes. A total of seven major clusters were identified for the P-Loop-GLPL region (Additional File 7, Additional File 8). Candidate sequences were clustered on the basis of similarity to putative orthologues identified from preliminary BLASTX analysis. The majority were most closely related to those from other ryegrass species, although some showed highest sequence similarity to template genes from other species. Sequences similar to rice R genes were also grouped with flax, lettuce and A. thaliana accessions [cluster C], and a sub-set of ryegrass sequences formed two separate clusters [clusters G and H] and may hence be similar to generic R gene variants previously identified in other species, which were not included within the alignment.

Eight major clusters were identified for the Kin-2A-GLPL region (Additional File 9, Additional File 10). Ryegrass-derived sequences were preferentially clustered with those from other Poaceae species (for instance, with oat sequences formerly used as LAP-design templates [cluster A], and with rice and barley sequences [clusters C and G, respectively]). Sequences from a number of dicotyledonous plant species were separately clustered for the P-Loop-GLPL [cluster E], but co-located in several distinct clusters [cluster D and E] with ryegrass-derived sequences for the Kin-2A-GLPL region.

In vitroSNP discovery and genetic mapping of perennial ryegrass R genes

Sixty-five distinct R gene templates were subjected to in vitro SNP discovery through resequencing from parental genotypes of the F1(NA6 × AU6) mapping population. Genomic DNA of a cumulative length of c. 37 kb was analysed and a total of 819 R gene SNPs were predicted, at an overall frequency of 1 per 46 bp. A total of 11 (17%) template biparental contigs contained no SNPs, while 27 (42%) of the remaining templates contained under 10 SNPs (Table 2). All monomorphic R gene contigs were derived from the NBS domain, apart from two encoding receptor kinase-like enzymes. SNP incidence was low within introns, due to limited representation in the sample set. SNP frequencies within parental genotypes was higher for NA6 (38) than for AU6 (20). A further 8 SNPs with biparental (AB × AB) segregation structures and 4 SNPs with AA × BB structures were identified.

Multiple R gene SNPs from 37 (69%) of 54 SNP-containing R gene contigs were validated (Additional File 11). A total of 26 R genes were assigned to loci on the parental maps of the F1 (NA6 × AU6) mapping population (22 on all NA6 LGs [Figs. 3, 4], 10 on all but LG4 for AU6 [Figs. 5, 6]). SNPs in four R gene loci showed biparental segregation structures, mapping to the equivalent LG position in each parental map, and hence provide bridging markers. Five loci were also mapped to equivalent positions on three p150/112 LGs. A single SNP locus derived from the template sequence LpHvESTClone1.1 (xlprg50-464ca) was mapped in p150/112 but not in F1(NA6 × AU6) (Fig. 7)

Genetic linkage maps of LGs 1–4 from the NA 6 parental genotype of the F 1 (NA 6 × AU 6 ) cross. Nomenclature for the parental maps of the F1(NA6 × AU6) cross is as follows: EST-RFLP markers are indicated with xlp (co-dominant Lolium perenne locus) prefixes and gene-specific abbreviations, while EST-SSR are indicated with xpps prefixes, both as described in [50]; genomic DNA-derived (LPSSR) markers are indicated as xlpssr loci using the nomenclature described in [56]. SNP loci are designated according to the nomenclature xlp-gene name abbreviation-nucleotide coordinate-SNP identity [48]. For instance, xlpchijb-240cg on NA6 LG5 is derived from a chitinase class gene (LpCHIjb), and the SNP is a C-G transversion located at coordinate 240. DR gene SNP loci are indicated in bold red type, and corresponding RFLP loci in black bold italic type. R gene SNP loci (designated with xlprg prefixes, and numbered according to Table 2), are indicated in bold blue type. Auxiliary DR and R gene loci mapped using JOINMAP 3.0, but not MAPMAKER 3.0, are interpolated between flanking markers to provide approximate genetic map locations.

Genetic linkage maps of LGs 1,2 and 5 from the p150/112 reference population. Marker nomenclature for the p150/112 map is as follows: AFLP loci are indicated in the format exxtyyyyy (e.g., e33t50800) and heterologous RFLP loci are indicated as × plus the relevant probe name (e.g., xcdo580). Homologous RFLP loci detected by PstI genomic clones are indicated as xablpgxxx (e.g.xablpg26y). Isoenzyme and EST markers are indicated with xlp prefixes and abbrevations for gene function (e.g. acp/2 and osw). Details of SNP loci are as described in the legend to Fig. 3.

R gene locus clusters were identified on a number of LGs, often in close proximity to mapped DR gene loci (represented by SNP and previously mapped EST-RFLP loci). Major clusters were identified in the lower regions of LGs 1 and 2 and the upper region of LG5 of both F1 (NA6 × AU6) parental maps (Fig. 3, 4, 5, 6).

Comparative genetic mapping based on R gene loci

Genetic mapping facilitated map integration between trait-specific ryegrass genetic maps, and also comparative relationships with other Lolium and Poaceae taxa. Coincidences between SNP loci assigned to the F1(NA6 × AU6) parental maps and crown rust resistance QTLs detected in other studies were observed for LGs 1, 2, 5, and 7. Two R gene loci co-located with the crown rust resistance QTLs LpPc2 and LpPc4 in the lower region of LG1 (Fig. 8). A further two loci were assigned to the centromeric region of p150/112 LG2, 4 cM distant from the genomic DNA-derived SSR locus xlpssrk02e02 which is closely associated with LpPc1. This marker locus group also co-locates with LpPc3 in the F1(SB2 × TC1) LG2 map, and through comparative alignment, with the hexaploid oat Pca cluster on LGB based on the position of the heterologous RFLP locus xcdo385.2 (Fig. 9). The R gene SNP locus xlprg60-216gt mapped adjacent to a previously-identified crown rust resistance QTL on AU6 LG7, and in putative alignment with a corresponding QTL on LG7 of the Lolium interspecific hybrid ψ-F2(MFA × MFB) population map, but a limited number of common markers precluded further interpretation (data not shown).

Comparative mapping analysis between candidate R gene SNP loci mapped in the F 1 (NA 6 × AU 6 ) population and QTLs for crown rust resistance from other published studies. Alignment of NA6-LG1 with LpPc2 and LpPc4 on LG1 F1(SB2 × TC1) [17]. Marker nomenclature for the NA6 and AU6 maps is as described in [48, 50] and the legend for Fig. 3. Marker nomenclature within the F1(SB2 × TC1) mapping population is described in [17].

Comparative mapping analysis between candidate R gene SNP loci mapped in the p150/112 population and QTLs for crown rust resistance from other published studies. Alignment of p150/112-LG2 with the LpPc1 and LpPc3 loci on LG2 F1(SB2 × TC1) [17] and the Pca cluster on hexaploid oat LGB (adapted from [14]). Marker nomenclature for the p150/112 maps is as described in [48, 50] and the legend for Fig. 7. The location of the LpPc1 crown rust resistance locus is as described in [14] and marker nomenclature within the F1(SB2 × TC1) mapping population is described in [17].

Comparative genomic analysis detected conserved relationships between perennial ryegrass Lrk10 R gene SNP locus (xlprg1-369ct) and the corresponding cereal LrK10 template genes. A macrosyntenic region was identified on LG1, although low numbers of common genetic markers again limited the accuracy of extrapolation (Fig. 10). The perennial ryegrass R gene loci xlprg24-460at and xlprg54-688ag are derived from putative orthologues of the barley R genes HvS-217 and HvS-L8, respectively. Alignment of genetic maps revealed conserved syntenic locations, as well as coincidence with QTLs for leaf rust and powdery mildew resistance on barley 2H and 3H, respectively (Additional File 12, Additional File 13).

Comparative mapping analysis of the perennial ryegrass LrK10 SNP locus (xlprg1-368ct). Macrosynteny of putative Lrk10 ortholoci was compared in other Poaceae species through alignment with LG1 of Italian ryegrass [76], LG4_12 from hexaploid oat, 1AS from wheat, 1HS from barley and 1RS from rye [41]. Black dotted lines align common genomic DNA-derived SSR markers (indicated in bold black italics) and an orange dotted line links the genetic map positions of LrK10 ortholoci.

Discussion

Large-scale survey of perennial ryegrass NBS domain-containing sequences

This study describes the most comprehensive study to date of ryegrass NBS domain-containing sequences. The largest comparable surveys were of R genes from Italian ryegrass (62 sequences: [39]) and from both annual and perennial ryegrass and the corresponding interspecific hybrid (16 sequences: [38], all derived by means of degenerate primer-based amplification. In this study, 102 distinct R genes were isolated and functionally annotated. Bioinformatic analysis identified the majority of candidate genes as members of the NBS-LRR family responsible for major gene resistance in plant species [29, 60–64]. A proportion of c. 20% of all perennial ryegrass R genes may be estimated to have been sampled, assuming equivalent gene content to that revealed (545 NBS sequences) by the genome-wide survey of rice [31]. It is possible, however, that major rounds of genome duplication or divergence events between species may have occurred, based on different selection pressures of surrounding pathogen populations. Such factors may influence the relative number of NBS-containing sequences in ryegrass species.

Structural classification of perennial ryegrass NBS sequences

Results from the current study suggest that only non-TIR NBS sequences are present within the Lolium genome, consistent with previous results from monocotyledonous species [33, 37–39, 58, 65]. Only degenerate primers specific to non-TIR sequences were able to amplify PCR products from perennial ryegrass genomic DNA, as observed in similar studies of sorghum [34].

Substantial variation was observed within coding regions of non-TIR NBS-LRRs, which exhibit greater sequence diversity than the TIR-NBS sub-family [66]. In this study, many R genes lacked the P-Loop region, while others contained NBS-NBS domains, duplicated CC regions or lacked CC and/or LRR domains. P-Loop, Kin-2A and GLPL motifs were conserved and similar in sequence to those of closely related Poaceae species such as wheat and rice [31, 58] and the model dicotyledonous species A. thaliana [30]. Further evidence for structural gene diversity was observed within particular NBS sub-families. NBS sub-classes contained specific signature motifs between conserved regions, and in some instances, RNBS motifs were missing or duplicated. This suggests that the RNBS-I and RNBS-II motifs may either play a role in pathogen-specific recognition, or be less functionally significant than other, more highly conserved domains mediating resistance in plant species [30, 66]. Alternatively, the presence of CC-NBS-specific motifs may suggest divergence to perform specialised functions. Variability was also observed within LRR domains, suggesting that NBS-LRRs in ryegrass are diverse in function [64, 67].

Phylogenetics of Lolium NBS domain-containing sequences and relationship to genomic location and evolution

Amino acid diversity in the P-Loop-Kin-2A region may account for the major differences between TIR-NBS and CC-NBS domains. The results from this study demonstrate that TIR-NBS sequences from flax and A. thaliana group in a separate cluster, as observed in a previous phylogenetic analysis of Lolium NBS domains [38]. Further sequence analysis of a larger number of Lolium sequences in the Kin-2A-GLPL motif interval demonstrated increased sequence similarity with known TIR-NBS regions from dicotyledonous plant species, suggesting that this region may be more conserved across taxa. Consensus motif order and sequence composition indicates that the Lolium RNBS-I region may have diverged from that of dicotyledonous plants. Similar results were observed in other Poaceae species such as sorghum, for which RNBS-I consensus sequences showed significantly higher similarity to those of rice than to those of A. thaliana TIR-NBS genes [34].

Phylogenetic analysis of the P-Loop-GLPL and the Kin-2A-GLPL domains detected at least 8 NBS sub-classes, as compared to 5 separate clusters identified in a previous study [38]. Analysis of the larger number of Kin-2A-GLPL interval sequences obtained only one more cluster than for the P-Loop-GLPL interval, indicative of domain conservation. Inclusion of NBS sequences from other closely, and more distantly related, species permitted grouping of R genes and inference of possible common origins for R gene sub-families. Sequences amplified from oat templates clustered together with ryegrass template-derived R genes, suggestive of a common origin. Based on known mechanisms of R gene evolution, gene duplication and divergence prior to speciation within the Pooideae sub-tribe is likely to account for the sequence similarity between ryegrass and oat genes, corresponding to putative orthologues [49, 61, 68].

Candidate R gene SNP discovery and genetic mapping

The SNP frequency observed within this study was marginally lower than that detected within a sub-set of 11 perennial ryegrass R genes across 20 diverse genotypes [69], but similar to that observed within DR genes [21] and a broad range of functionally-annotated candidate genes [48] in the F1(NA6 × AU6) mapping population. Eight R gene templates contained up to 90 SNPs per contig, possibly due to paralogous sequence alignment. Large numbers of haplotypes have been reported for other perennial ryegrass NBS-LRR genes, especially within variable LRR regions [69]. The data from this study suggests that allelic diversity within NBS domain is low compared to the highly variable LRR domain.

Previous studies identified significantly non-random chromosomal distributions of NBS-containing sequences [30, 31]: 44 gene clusters were detected in the japonica sub-species of rice. Five major clusters containing two or more closely linked NBS-LRR genes, which frequently showed low mutual sequence similarity, were identified from only a small sub-set (26) of mapped perennial ryegrass R genes. This suggests that the gene location pattern in perennial ryegrass may be similar to that observed in other plant species. Unrelated R genes also mapped in close association with DR gene SNP and RFLP loci [21, 50]. QTL based analysis and genetic mapping in wheat identified co-location of DR and R genes at qualitative disease resistance loci [70, 71]. Co-location of R genes with DR genes was also observed in similar chromosomal regions (lower regions of LG1, LG2 and LG6) as disease resistance QTLs which were mapped both in F1(NA6 × AU6) and other trait-specific mapping populations [17, 20, 21].

Co-location of R gene SNP markers with disease resistance QTLs

SNP mapping of two candidate R genes in both the F1(NA6 × AU6) and p150/112 mapping populations has provided possible candidates for the major gene crown rust resistance QTL (LpPc1) on LG2 [14]. To determine whether R gene SNP variants are of functional significance, further experiments involving transgenic approaches, association genetic analysis or map-based cloning are required [72, 73].

NBS-LRR genes loci mapping to the distal region of LG1 in the F1(NA6x AU6) parental genetic maps (xlprg29-293at, xlprg30-707ag and xlprg61-23ga) are potential candidates for resistance effects to crown rust pathotypes which are yet to be identified within Australasia. Major QTLs for crown rust resistance (LpPc2 and LpPc4) have been mapped to the lower part of LG1 in 3 different perennial ryegrass trait-specific mapping populations [17–19] but the limited number of common markers limits accurate extrapolation between genetic maps. Two QTLs of large magnitude were identified in each of the three populations, which were screened using European crown rust isolates However, so far no resistance QTLs have been detected within this chromosomal region using isolates from the southern hemisphere. As both F1(NA6 × AU6) mapping population parental genotypes are derived from Eurasia [50], LG1-located R gene polymorphisms may confer resistance to crown rust isolates of European provenance.

Comparative genomics analysis of perennial ryegrass R genes

Comparative analysis of R gene SNP loci and corresponding ortholoci confirmed previously reported macrosyntenic relationships between perennial ryegrass and other Poaceae species [45] in nearly all instances. The sole exception was the xlprg8-271ct locus, which was assigned to LG1 despite being derived from (and highly similar to) an oat Pca template gene predicted to map to LG2. Genetic mapping of the LpLrk10 locus to LG1 suggested that the structure and chromosomal location of this gene are highly conserved throughout the Pooideae [41, 43, 58]. The equivalent analysis for barley R gene ortholoci provides the basis for testing R gene functionality in response to a broader range of plant diseases, requiring significant improvements of pathogen phenotyping [74] and corresponding genetic analysis [42, 75].

Conclusion

This study has demonstrated that multiple approaches to R gene discovery, including the use of homologous and heterologous templates, can generate significant numbers of candidate genes for major disease resistance loci. An enhanced resource of R gene templates from perennial ryegrass has permitted evaluation of gene structural diversity and putative evolutionary origins. Efficient in vitro discovery methods allowed assignment of R gene-derived SNPs to genomic locations, revealing coincidence with pathogen resistance QTLs in ryegrasses, as well as comparative relationships with other grass and cereal species. R gene-associated markers are suitable for further evaluation and implementation in forage grass improvement programs.

References

Fulkerson WJ, Slack K, Lowe KF: Variation in the response of Lolium genotypes to defoliation. Aus J Agric Res. 1994, 45: 1309-1317. 10.1071/AR9941309.

Terry RA, Tilley JMA: The digestibility of the leaves and stems of perennial ryegrass, cocksfoot, timothy, tall fescue, lucerne and sainfoin, as measured by an in vitro procedure. J Brit Grassland Soc. 1964, 19: 363-372.

Lancashire JA, Latch GCM: Some effects of crown rust (Puccinia coronata Corda) on the growth of two ryegrass varieties in New Zealand. NZ J Agric Res. 1966, 9: 628-640.

Price T: Ryegrass rust in Victoria. Plant Protect Quart. 1987, 2: 189

Kimbeng CA: Genetic basis of crown rust resistance in perennial ryegrass, breeding strategies, and genetic variation among pathogen populations: a review. Aus J Exp Agric. 1999, 39: 361-378. 10.1071/EA98111.

Mattner SW, Parbery DG: Rust-enhanced allelopathy of perennial ryegrass against white clover. Agronomy J. 2001, 93: 54-59.

Dracatos PM, Dumsday JL, Olle RS, Cogan NOI, Dobrowolski MP, Fujimori M, Roderick H, Stewart AV, Smith KF, Forster JW: Development and characterization of EST-SSR markers for the crown rust pathogen of ryegrass (Puccinia coronata f.sp lolii). Genome. 2006, 49: 572-583. 10.1139/G06-006.

Cagas B: The effect of infection by crown rust on the thousand-seed weight of annual ryegrass. Rostlinna Vyroba. 1986, 32: 873-880.

Landschoot PJ, Hoyland BF: Gray leaf spot of perennial ryegrass turf in Pennsylvania. Plant Dis. 1972, 76: 1280-1282.

Cornish MA, Hayward MD, Lawrence MJ: Self-incompatibility in ryegrass. I. genetic control in diploid Lolium perenne L. Heredity. 1992, 43: 95-106. 10.1038/hdy.1979.63.

Clarke RG, Villata ON, Hepworth G: Evaluation of resistance to five isolates of Puccinia coronata f. sp. lolii in 19 perennial ryegrass cultivars. Aus J Agric Res. 1997, 48: 191-198. 10.1071/A95036.

Guthridge KM, Dupal MP, Kölliker R, Jones ES, Smith KF, Forster JW: AFLP analysis of genetic diversity within and between populations of perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Euphytica. 2001, 122: 191-201. 10.1023/A:1012658315290.

van Treuren R, Bas N, Goossens PJ, Jansen J, van Soest LJM: Genetic diversity in perennial ryegrass and white clover among old Dutch grasslands as compared to cultivars and nature reserves. Mol Ecol. 2005, 14: 39-52. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02391.x.

Dumsday JL, Smith KF, Forster JW, Jones ES: SSR-based genetic linkage analysis of resistance to crown rust (Puccinia coronata f. sp lolii) in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne). Plant Path. 2003, 52: 628-637. 10.1046/j.1365-3059.2003.00884.x.

Armstead IP, Harper JA, Turner LB, Skøt L, King IP, Humphreys MO, Morgan WG, Thomas HM, Roderick HW: Introgression of crown rust (Puccinia coronata) resistance from meadow fescue (Festuca pratensis) into Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum): genetic mapping and identification of associated molecular markers. Plant Path. 2006, 55: 62-67. 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2005.01308.x.

Muylle H, Baert J, Van Bockstaele E, Moerkerke B, Goetghebeur E, Roldan-Ruiz I: Identification of molecular markers linked with crown rust (Puccinia coronata f. sp. lolii) resistance in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) using AFLP markers and a bulked segregant approach. Euphytica. 2005, 143: 135-144. 10.1007/s10681-005-3058-1.

Muylle H, Baert J, Van Bockstaele E, Pertijs J, Roldan-Ruiz I: Four QTLs determine crown rust (Puccinia coronata f. sp. lolii) resistance in a perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) population. Heredity. 2005, 95: 348-357. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800729.

Studer B, Boller B, Bauer E, Posselt U, Widmer F, Kölliker R: Consistent detection of QTLs for crown rust resistance in Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.) across environments and phenotyping methods. Theor Appl Genet. 2007, 115: 9-17. 10.1007/s00122-007-0535-z.

Schejbel B, Jensen LB, Xing Y, Lübberstedt T: QTL analysis of crown rust resistance in perennial ryegrass under conditions of natural and artificial infection. Plant Breed. 2007, 126: 347-352. 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2007.01385.x.

Sim S, Diesburg K, Casler M, Jung G: Mapping and comparative analysis of QTL for crown rust resistance in an Italian × perennial ryegrass population. Phytopathol. 2007, 97: 767-776. 10.1094/PHYTO-97-6-0767.

Dracatos PM, Cogan NOI, Dobrowolski MP, Sawbridge TI, Spangenberg GC, Smith KF, Forster JW: Discovery and genetic mapping of single nucleotide polymorphisms in candidate genes for pathogen defence response in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2008, 117: 203-219. 10.1007/s00122-008-0766-7.

Curley J, Chakraborty N, Chang S, Jung G: QTL mapping of resistance to grey leaf spot in ryegrass: consistency of QTL between two mapping populations. J Korean Turfgrass Sci. 2008, 22: 85-100.

Studer B, Boller B, Herrmann D, Bauer E, Posselt UK, Widmer F, Kölliker R: Genetic mapping reveals a single major QTL for bacterial wilt resistance in Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.). Theoretical Appl Genet. 2006, 113: 661-671. 10.1007/s00122-006-0330-2.

Schejbel B, Jensen LB, Asp T, Xing Y, Lübberstedt T: Mapping QTL for resistance to powdery mildew and resistance gene analogues in perennial ryegrass. Plant Breed. 2008, 127: 368-375. 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2007.01477.x.

Curley J, Sim SC, Warnke S, Leong SB, Jung G: QTL mapping of resistance to grey leaf spot in ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2005, 111: 1107-1117. 10.1007/s00122-005-0036-x.

Dracatos PM, Dumsday JL, Stewart A, Dobrowolski MP, Cogan NOI, Smith KF, Forster JW: Genetic diversity in Australasian populations of the crown rust pathogen of ryegrasses (Puccinia coronata f.sp. lolii). Molecular Breeding of Forage and Turf: The Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on the Molecular Breeding of Forage and Turf. Edited by: Yamada T, Spangenberg GC. Springer, New York, USA; 2008:275-285.

Aldaoud R, Anderson MW, Reed KFM, Smith KF: Evidence of pathotypes among Australian isolates of crown rust infecting perennial ryegrass. Plant Breed. 2004, 123: 395-397. 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2004.00951.x.

Dodds PN, Lawrence G, Pryor T, Ellis J: Genetic analysis and evolution of plant disease resistance genes. Molecular Plant Pathology. Edited by: Dickinson M, Beynon J. Sheffield Academic Press., Sheffield, UK; 2000:88-107.

Dangl JL: Piece de Resistance: Novel class of plant disease resistance genes. Cell. 1995, 80: 363-366. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90485-9.

Meyers BC, Kozik A, Griego A, Kuang H, Michelmore RW: Genome-wide analysis of NBS-LRR-encoding genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2003, 15: 809-834. 10.1105/tpc.009308.

Zhou T, Wang Y, Chen JQ, Araki H, Jing Z, Jiang K, Shen J, Tian D: Genome-wide identification of NBS genes in japonica rice reveals significant expansion of divergent non-TIR NBS-LRR genes. Mol Genet Genom. 2004, 271: 402-414. 10.1007/s00438-004-0990-z.

Wisser RJ, Sun Q, Hulbert SH, Kresovich S, Nelson RJ: Identification and characterisation of regions of the rice genome associated with broad-spectrum, quantitative disease resistance. Genetics. 2005, 169: 2277-2203. 10.1534/genetics.104.036327.

Madsen LH, Collins NC, Rakwalska M, Backes G, Sandal N, Krusell L, Jensen J, Waterman EH, Jahoor A, Ayliffe M, Pryor AJ, Langridge P, Schulze-Lefert P, Stougaard J: Barley disease resistance gene analogs of the NBS-LRR class: identification and mapping. Mol Genet Genomics. 2003, 269 (1): 150-161.

Cho J: Isolation and characterisation of resistance gene analogues (RGAs) in sorghum. Ph.D. Thesis. 2005, Texas A&M University, USA.

Wenkai X, Mingliang X, Jiuren Z, Fengge W, Jiansheng L, Jingrui D: Genome-wide isolation of resistance gene analogs in maize (Zea mays L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2006, 113: 63-72. 10.1007/s00122-006-0272-8.

Monosi B, Wisser RJ, Pennill L, Hulbert SH: Full-genome analysis of resistance gene homologues in rice. Theor Appl Genet. 2004, 109: 1434-1447. 10.1007/s00122-004-1758-x.

Irigoyen ML, Loarce Y, Fominaya A, Ferrer E: Isolation and mapping of resistance gene analogs from the Avena strigosa genome. Theor Appl Genet. 2004, 109: 713-724. 10.1007/s00122-004-1679-8.

Li J, Xu Y, Fei S, Li L: Isolation, characterisation and evolutionary analysis of resistance gene analogs in annual ryegrass, perennial ryegrass and their hybrid. Physiologia Plantarium. 2006, 126: 627-638.

Ikeda S: Isolation of disease resistance gene analogues from Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.). Grasslands Sci. 2005, 51: 63-70. 10.1111/j.1744-697X.2005.00010.x.

Feuillet C, Keller B: High gene density is conserved at syntenic loci of small and large grass genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999, 96: 8265-8270. 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8265.

Cheng DW, Armstrong KC, Tinker N, Wight CP, He S, Lybaert A, Fedak G, Molnar SJ: Genetic and physical mapping of Lrk10-like receptor kinase sequences in hexaploid oat (Avena sativa L.). Genome. 2003, 45: 100-109. 10.1139/g01-135.

Forster JW, Cogan NOI, Dobrowolski MP, Francki MG, Spangenberg GC, Smith KF: Functionally-associated molecular genetic markers for temperate pasture plant improvement. Plant Genotyping II: SNP Technology. Edited by: Henry RJ. CABI Press, Wallingford, Oxford, UK; 2008:154-187.

Feuillet C, Schachmayr G, Keller B: Molecular cloning of a new receptor-like kinase gene encoded at the Lr10 resistance locus of wheat. Plant J. 1997, 11: 45-52. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.11010045.x.

Soreng RJ, Davis JI: Phylogenetics and character evolution in the grass family (Poaceae): Simultaneous analysis of morphological and chloroplast DNA restriction site character sets. Botanical Rev. 1998, 64: 1-85. 10.1007/BF02868851.

Jones ES, Mahoney NL, Hayward MD, Armstead I, Gilbert Jones J, Humphreys MO, King IP, Kishida T, Yamada T, Balfourier F, Charmet G, Forster JW: An enhanced molecular marker based genetic map of perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) reveals comparative relationships with other Poaceae genomes. Genome. 2002, 45: 282-295. 10.1139/g01-144.

Sawbridge T, Ong E, Binnion C, Emmerling M, McInnes R, Meath K, Nguyen N, Nunan K, O'Neill M, O'Toole F, Rhodes C, Simmonds J, Tian P, Wearne K, Webster T, Winkworth A, Spangenberg G: Generation and analysis of expressed sequence tags in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Plant Sci. 2003, 165: 1089-1100. 10.1016/S0168-9452(03)00304-2.

Erwin TA, Jewell EG, Love CG, Lim GAC, Li X, Chapman R, Batley J, Stajich JE, Mongin E, Stupka ER, Spangenberg G, Edwards D: BASC: an integrated bioinformatics system for Brassica research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35: 870-873. 10.1093/nar/gkl998.

Cogan NOI, Ponting RC, Vecchies AC, Drayton MC, George J, Dracatos PM, Dobrowolski MP, Sawbridge T, Smith KF, Spangenberg G, Forster JW: Gene-associated single nucleotide polymorphism discovery in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Mol Genet Genom. 2006, 276: 101-112. 10.1007/s00438-006-0126-8.

Leister D, Ballvora A, Salamini F, Gebhardt C: A PCR-based approach for isolating pathogen resistance genes from potato with potential for wide application in plants. Nat Genet. 1996, 14: 421-429. 10.1038/ng1296-421.

Faville MJ, Vecchies AC, Schreiber M, Drayton MC, Hughes LJ, Jones ES, Guthridge KM, Smith KF, Sawbridge T, Spangenberg GC, Bryan GT, Forster JW: Functionally associated molecular genetic marker map construction in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2004, 110: 12-32. 10.1007/s00122-004-1785-7.

Bateman A, Birney E, Cerruti L, Durbin R, Etwiller L, Eddy SR, Griffiths-Jones S, Howe KL, Marshall M, Sonnhammer ELL: The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30: 276-280. 10.1093/nar/30.1.276.

Finn RD, Mistry J, Scuster-Bockler B, Griffiths-Jones S, Hollich V, Lassmann T, Moxon S, Marshall M, Khanna A, Durbin R, Eddy SR, Sonnhammer LL, Bateman A: Pfam: clans, web tools and services. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34: D247-D251. 10.1093/nar/gkj149.

Bailey TL, Elkan C: The value of prior knowledge in discovering motifs with MEME. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol. 1995, 3: 21-29.

Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG: The ClustalX windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 24: 4876-4882. 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876.

Felsenstein J: Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985, 39: 783-791. 10.2307/2408678.

Jones ES, Dupal MP, Dumsday JL, Hughes LJ, Forster JW: An SSR-based genetic linkage map for perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2002, 105: 577-584. 10.1007/s00122-002-0907-3.

Fulton TM, Chunwongse J, Tanksley SD: Microprep protocol for extraction of DNA from tomato and other herbaceous plants. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 1995, 13: 207-209. 10.1007/BF02670897.

Maleki L, Faris JD, Bowden RL, Gill BS, Fellers JP: Physical and genetic mapping of wheat kinase analogs and NBS-LRR resistance gene analogs. Crop Sci. 2003, 43: 660-670.

Gallego F, Feuillet C, Messmer M, Penger A, Graner A, Yano M, Sasaki T, Keller B: Comparative mapping of the two wheat leaf rust resistance loci Lr1 and Lr10 in rice and barley. Genome. 1998, 41: 328-336. 10.1139/gen-41-3-328.

Dangl JL, Dietrich RA, Richberg MH: Death don't have no mercy: cell death programs in plant-microbe interactions. Plant Cell. 1996, 8 (10): 1793-1807. 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1793.

Dangl JL, Holub E: La Dolce Vita: a molecular feast in plant-pathogen interactions. Cell. 1997, 91: 17-24. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)80005-2.

Ellis J, Lawrence G, Ayliffe M, Anderson P, Collins N, Finnegan J, Frost D, Luck J, Pryor T: Advances in the molecular genetic analysis of the flax-flax rust interaction. Ann Rev Phytopathol. 1997, 35: 271-291. 10.1146/annurev.phyto.35.1.271.

Ellis J, Dodds P, Pryor T: Structure, function and evolution of plant disease resistance genes. Curr Op Plant Biol. 2000, 3: 278-284. 10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00080-7.

Dangl JL, Jones JD: Plant pathogens and integrated defence responses to infection. Nature. 2001, 411: 826-833. 10.1038/35081161.

Bai J, Pennill LA, Ning J, Lee SW, Ramalingam J, Webb CA, Zhao B, Sun Q, Nelson JC, Leach JE, Hulbert SH: Diversity in nucleotide binding site-leucine-rich repeat genes in cereals. Genet Res. 2002, 12: 1871-1884. 10.1101/gr.454902.

Meyers BC, Dickerman AW, Michelmore RW, Sivaramakrishnan S, Sobral BW, Young ND: Plant disease resistance genes encode members of an ancient and diverse protein family within the nucleotide-binding site family. Plant J. 1999, 20: 317-332. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.t01-1-00606.x.

Meyers BC, Kaushik S, Nandety RS: Evolving disease resistance genes. Curr Op Plant Biol. 2005, 8: 129-134. 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.01.002.

Leister D, Kurth DA, Laurie DA, Yano M, Sasaki T, Devos KM, Graner A, Schulze-Lefert P: Rapid reorganisation of resistance gene homologues in cereal genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998, 95: 370-375. 10.1073/pnas.95.1.370.

Xing Y, Frei U, Schejbel B, Asp T, Lübberstedt T: Nucleotide diversity and linkage disequilibrium in 11 expressed resistance genes in Lolium perenne. BMC Plant Biol. 2007, 7: 43-10.1186/1471-2229-7-43.

Faris JD, Li WL, Liu DJ, Chen PD, Gill BS: Candidate gene analysis of quantitative disease resistance in wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 1999, 98: 219-225. 10.1007/s001220051061.

Li WL, Faris JD, Chittoor JM, Leach JE, Hulbert SH, Liu DJ, Chen PD, Gill BS: Genomic mapping of defense response genes in wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 1999, 98: 226-233. 10.1007/s001220051062.

Takahashi W, Fujimori M, Miura Y, Komatsu T, Nishizawa Y, Hibi T, Takamizo T: Increased resistance to crown rust disease in transgenic Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.) expressing the rice chitinase gene. Plant Cell Reps. 2004, 23: 811-818. 10.1007/s00299-004-0900-1.

Ponting RC, Drayton MC, Cogan NOI, Dobrowolski MP, Smith KF, Spangenberg GC, Forster JW: SNP discovery, validation, haplotype structure and linkage disequilibrium in full-length herbage nutritive quality genes of perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Mol Genet Genom. 2007, 278: 585-597. 10.1007/s00438-007-0275-4.

Dracatos PM, Dobrowolski MP, Lamb J, Olle R, Gendall AR, Cogan NOI, Smith KF, Forster JW: Development of genetically homogenised populations of the crown rust pathogen (Puccinia coronata f.sp. lolii) for disease trait dissection in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Australasian Plant Path. 2009, 38: 55-62. 10.1071/AP08077.

Dobrowolski MP, Forster JW: Linkage disequilibrium-based association mapping in forage species. Association Mapping in Plants. volume Chapter 9 Edited by: Oraguzie NC, Rikkerink E, Gardiner SE, De Silva NH. Springer, New York, USA; 2007:97-209.

Miura Y, Hirata M, Fujimori M: Mapping of EST-derived CAPS markers in Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.). Plant Breed. 2007, 126: 353-360. 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2007.01386.x.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the Victorian Department of Primary Industries, Dairy Australia Ltd., the Geoffrey Gardiner Dairy Foundation, Meat and Livestock Australia Ltd. and the Molecular Plant Breeding Cooperative Research Centre (MPB CRC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

PD carried out the experimental work and the majority of analysis, prepared the tables and figures and the primary drafts of the manuscript, and contributed to finalisation of the text and journal-specific formatting. NC co-conceptualised the project and contributed to data analysis and text preparation. TS provided EST sequence information and assisted preparation of files for GenBank submission. TG co-conceptualised the project and contributed to text preparation. KS co-conceptualised the project and developed and contributed genetically-defined plant materials. GS provided EST sequence information and valuable editorial advice. JF co-conceptualised the project, provided overall project leadership, and co-developed interim and final drafts of the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12870_2009_404_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Additional File 1: Degenerate oligonucleotide primers used for NBS domain-containing sequence amplification. Sequence information for primer synthesis was obtained from published data specific to barley, sorghum and perennial ryegrass. (DOC 36 KB)

12870_2009_404_MOESM2_ESM.doc

Additional File 2: Bioinformatic (BLASTX and wuBLASTX) annotation of cloned and sequenced primary and secondary perennial ryegrass R gene templates to both GenBank and UniProt databases within the Bioinformatic Advanced Scientific Computing (BASC) database (as of June 2007 release). BASC is linked to the rice Ensemble Browser and Uniprot databases and employs known gene ontology and Pfam domain analysis to assign putative function to candidate sequences. Nomenclature of paralogous sequences is based on the unique identifier for the primary template sequence (e.g., LpESTe11_14) followed by a numerical suffix (.1, .2 etc.), e.g. LpESTe11_14rg.1. (DOC 252 KB)

12870_2009_404_MOESM3_ESM.doc

Additional File 3: Summary details for specific R gene-directed degenerate primer pair combinations, as described in Additional File 1, along with primer pair code, numbers of amplification products and corresponding R gene templates.(DOC 39 KB)

12870_2009_404_MOESM4_ESM.doc

Additional File 4: Functional characterisation of predicted translation products from perennial ryegrass candidate R genes. All information was derived from Pfam links within the best-available Uniprot wuBLASTX hits in BASC. Pfam information was used to obtain the probable location of candidate sequences, protein size, position of NBS sequence and number of LRR repeats. (DOC 216 KB)

12870_2009_404_MOESM5_ESM.doc

Additional File 5: Major protein sequence motifs in predicted Lolium NBS domains. aMotifs listed in the order of occurrence in the NBS domain of putative perennial ryegrass R genes. Perennial ryegrass motifs were named in accordance with descriptions obtained from both rice and A. thaliana [30, 31, 66]; bBioinformatic analysis using Pfam on putative R gene sequences identified all to be CC-NBS types (CNL denotes CC-NBS-LRR and TNL denotes TIR-NBS-LRR); cConsensus amino acid sequences for Lolium NBS sequences were derived from MEME, while those for wheat were derived from [58]. (DOC 48 KB)

12870_2009_404_MOESM6_ESM.doc

Additional File 6: Summary information of amino acid structure for NBS domain protein sequence motifs numbered in Fig. 2, based on matching using the MEME program.(DOC 37 KB)

12870_2009_404_MOESM7_ESM.doc

Additional File 7: Reference information for sequences corresponding to individual clusters identified during phylogenetic analysis for the complete NBS domain (P-Loop-GLPL), as depicted in Additional File 8. (DOC 73 KB)

12870_2009_404_MOESM8_ESM.ppt

Additional File 8: NJ dendrograms based on amino acid alignment of the full-length (P-Loop – GLPL) regions of NBS protein domains encoded by LoliumR genes. Bootstrap values are displayed as percentages of 1000 neighbour joining bootstrap replications. Bootstrap values at or greater than 65% are shown. Bars at the right of the dendrograms represent R gene sub-classes. (PPT 135 KB)

12870_2009_404_MOESM9_ESM.doc

Additional File 9: Reference information for sequences corresponding to individual clusters identified during phylogenetic analysis for the Kin-2A-GLPL region of the NBS domain, as depicted in Additional File 10. (DOC 151 KB)

12870_2009_404_MOESM10_ESM.ppt

Additional File 10: NJ dendrograms based on amino acid alignment of the partial (Kin-2A -GLPL) regions of NBS protein domains encoded by Lolium R genes. Details are as described in the legend for Additional File 8. (PPT 152 KB)

12870_2009_404_MOESM11_ESM.doc

Additional File 11: Summary information for LAP and SNuPe primers used for predicted R gene SNP validation. Information on segregation structure, parental polymorphism, SNP variant and successful genetic map assignment is included. All LAP PCRs and SNuPe reactions were designed for operating annealing temperatures of 55°C and 50°C, respectively. (DOC 86 KB)

12870_2009_404_MOESM12_ESM.ppt

Additional File 12: Comparative chromosomal positions of predicted putative orthologous R genes between perennial ryegrass and barley: Lps-217 (coded as xlprg50-464ca) on p150/112 LG2 compared to Hvs-217 at the bottom of chromosome 2H. qLr represents a QTL for barley leaf rust resistance.(PPT 117 KB)

12870_2009_404_MOESM13_ESM.ppt

Additional File 13: Comparative chromosomal positions of predicted putative orthologous R genes between perennial ryegrass and barley: Lps-L8 (coded as xlprg54-688ag) on NA6-LG3 compared to Hvs-L8 at the bottom of chromosome 3H. qMIL represents a major QTL for powdery mildew resistance in barley.(PPT 112 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Dracatos, P.M., Cogan, N.O., Sawbridge, T.I. et al. Molecular characterisation and genetic mapping of candidate genes for qualitative disease resistance in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). BMC Plant Biol 9, 62 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-9-62

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-9-62