Abstract

Considering the social disintegration approach of Wilhelm Heitmeyer and colleagues, this contribution explores three different dimensions of perceived recognition—positional, moral, and emotional recognition—among the Austrian population. The main purpose is to identify social groups that do not feel recognized and thus could be affected by social disintegration. The analysis is based on data from the Austrian Social Survey (SSÖ), a random 2018 sample of 1200 respondents that is representative of the population aged 18 and above. Based on an explorative latent class analysis, we are able to identify four distinct groups: poorly recognized, emotionally unrecognized, positionally unrecognized, and entirely recognized. Our contribution shows that the latter is the largest group in Austria, even though this group of almost entirely recognized respondents is not convinced that they have an impact on Austrian politics.

Zusammenfassung

In Anlehnung an den Ansatz sozialer Desintegration von Wilhelm Heitmeyer und Kolleg*innen untersucht der vorliegende Beitrag drei verschiedene Dimensionen der subjektiven Anerkennung – positionale, moralische und emotionale Anerkennung – in der österreichischen Bevölkerung. Hauptziel ist es, soziale Gruppen zu identifizieren, die sich im Vergleich zu anderen nur wenig anerkannt fühlen und daher von sozialer Desintegration betroffen sein könnten. Die Analyse basiert auf Daten des Sozialen Survey Österreich (SSÖ), einer Zufallsstichprobe von 1200 Befragten aus dem Jahr 2018, die für die Bevölkerung ab 18 Jahren repräsentativ ist. Basierend auf einer explorativen Analyse latenter Klassen können vier verschiedene Gruppen identifiziert werden: Personen, die sich tendenziell in allen Dimensionen nicht anerkannt fühlen; die ein Defizit bei der emotionalen Anerkennung wahrnehmen; die sich positional wenig anerkannt sehen; sowie Personen, die sich durch wahrgenommene Anerkennung auf allen Ebenen auszeichnen. Unser Beitrag macht deutlich, dass Letztere die größte Gruppe in Österreich ausmachen, wobei selbst diese Gruppe nicht davon überzeugt ist, einen Einfluss auf die österreichische Politik zu haben.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Austria and Austrian society have been exposed to various forms of societal turbulence in the last decade, ranging from an economic crisis in 2009, an increased influx of migrants in 2015, to cleavages between the political left and right and between urban and rural regions. These particular events are paralleled by and embedded in the functional and social differentiation of modern societies, individualization processes, and eroding common values and norms in an increasingly globalized and complex world. Sped up by a growing importance of the capitalist logic of competition among rational actors, these developments may cause problems for social cooperation (Imbusch and Rucht 2005, p. 17–18). Consequently, they raise the classic sociological question of how social cohesion is maintained in a society and which factors foster integration and avoid social disintegration.

Considering Friedrichs and Jagodzinski’s (1999) overview of four theoretical approaches to the question of social integration, Kaletta (2008, p. 8) identifies the experience of social recognition as “elementary for the development and maintenance of a positive identity” (Kaletta 2008, p. 14). Individuals constitute communities in which they are integrated to a greater or lesser extent. The individual perception of being recognized by others thus plays a decisive role when explaining the dynamics of social cohesion and integration. The degree of perceived recognition indicates the ability of societies to balance conflicting interests and to guarantee a just distribution of goods, services, and participation opportunities.

At the same time, modern societies are prone to crises and not protected from processes of disintegration (Imbusch and Heitmeyer 2012, p. 10–15). Social disintegration may occur in three forms: Economic disintegration results from growing pressure on national labor markets, which leads to increasing numbers of working poor and people in precarious working conditions and the erosion of the middle strata of society. Political integration weakens due to the nation state’s loss of power, which results in increasing disenchantment with politics and dissatisfaction with political elites. Barriers to cultural integration arise from an ongoing pluralism and relativism of basic societal values that attenuate the sense of community.

If individuals and groups do not feel integrated in society or if they are not integrated sufficiently, hostile points of view will gain popularity because they offer simple explanations for the social situation and provide compensation for perceived losses (see the concept of group-focused enmity Allport 1954; Heitmeyer 2002). Social cohesion is particularly endangered when the political and economic systems are not able to provide basic performance of production and distribution, fostering “tribalism, inner enmity and social anomy” (Imbusch and Rucht 2005, p. 15).

Using these societal trends as a backdrop and following the social disintegration approach of Wilhelm Heitmeyer (1994), the main purpose of this article is to better understand potential social groups that do not feel recognized and might be undergoing social disintegration. This contribution thus aims to explore, describe and classify the perceptions of Austrians regarding recognition using data from the 2018 Austrian Social Survey (SSÖ).

In the next section, we will briefly introduce the social disintegration approach of the Bielefeld research group, which is followed by a description of the methods and data used for the analysis. Subsequently, we will present our major findings, first, the descriptive results of Austrian perceptions of recognition, second, the results of an explorative latent class analysis and third, the findings from a subsequent multinomial logistic regression analysis. This regression analysis is used to compare the subjective dimension of recognition, derived from the explorative latent class analysis, with self-reported more objective criteria of social condition (e.g. financial situation, degree of education) as well as sociodemographic characteristics (e.g. gender, age, migration background). Finally, we summarize and discuss our main findings for Austrian society and the meaning of the theoretical approaches of recognition.

2 Social disintegration approach of the Bielefeld research group

The social disintegration approach of the Bielefeld research group, developed in the 1990s by Wilhelm Heitmeyer and colleagues, addresses the causes and effects of social disintegration and emphasizes social conflict. Similar to the recognition theory of Axel Honneth (1992), Heitmeyer et al. distinguish three different dimensions of recognition necessary to achieve and explain social cohesion and social integration: a social-structural dimension, an institutional dimension, and a personal dimension (Heitmeyer 1994; see also Imbusch and Rucht 2005, p. 601). The social-structural dimension of recognition focuses on the problem of inadequate participation in material and cultural goods within a society. The major challenge on the institutional level is balancing conflicting interests in a fair and just manner by recognizing an equality of all members of society. Recognition on the personal level refers to the problem that interpersonal emotional and expressive relationships are necessary for the creation of meaning in people’s lives and of opportunities for self-realization. Similarly, Honneth (1992) assumes that the basic form of recognition considers emotional attention and support from primary reference persons. On that basis, moral recognition in the sense of equal rights (civil rights, human rights) as well as social recognition in the sense of appreciating a person’s abilities, talents and performance come into play (for a comparison of recognition theories see also Aschauer 2017, p. 119–138).

According to the Bielefeld approach and following Bernhard Peters (1993), social integration can be achieved through solving three problems of recognition (see Table 1): The problem of individualistic-functional system integration refers to a lack of opportunities in getting access to the material and cultural goods of a society because people do not have equal access to, for instance, the job market, the housing market or the educational system (Heitmeyer et al. 2012, p. 62; Petzke et al. 2007, p. 63). If this problem is solved, people will experience positional recognition.

Communicative-interactive social integration is endangered, when conflicting interests are out of balance and violate people’s integrity (Heitmeyer et al. 2012, p. 62). The basic prerequisite to solve this problem is to guarantee equal opportunities for participating in the political discourse and decision process. In this context, free elections and the right to vote for political parties are the minimal requirements. Beyond these aspects, the de facto political influence and the feeling that politicians take people’s needs and interests seriously will foster recognition and social integration (Petzke et al. 2007, p. 64). Given the achievement of this form of social integration, moral recognition will be the result, which Anhut and Heitmeyer (2000) regard as part of a communicative-interactive integration process.

The problem of cultural-expressive social integration considers emotional relationships between people that provide a meaning for one’s life, and open opportunities for self-realization (Heitmeyer et al. 2012, p. 63). This problem is solved, when people experience emotional recognition through interactions with family, friends, neighbors and other individuals. Thus, emotional recognition is closely linked to everyday experiences and the opportunity for interactions with the social environment (Petzke et al. 2007, p. 64) which Honneth considers the most basic form of recognition.

According to Heitmeyer (2007, p. 43), the state of a society can be measured based on how far it succeeds in meeting the requirements of economic and political participation as well as social membership. Although emotional recognition is considered the basis of social recognition by Honneth, no general rank order in the three dimensions of social integration can be assumed. From the perspective of a political democracy, moral recognition is the most fundamental condition for social cohesion because political participation offers the population, and also minorities, the opportunity to represent their interests in democratic societies (see e.g. van Deth 2009). In contrast, from a more materialistic view, it can be argued that positional recognition is the key for social integration because it affects access to the limited resources that people compete for (see e.g. Marx 2005 [1872]; Maslow 1943). Undeniably, recent European history has shown that both a lack of political and economic freedom can contribute to destabilize societies and endanger social cohesion. In our understanding none of the aforementioned approaches is predominant, hence, it does not seem plausible to assume that moral recognition is a prerequisite for positional recognition or vice versa. Therefore, we regard the three dimensions of social recognition as a nominal scale and remain open for analyzing different patterns of recognition in an explorative manner.

In regard to the social disintegration approach of the Bielefeld research group, we address the following questions:

How pronounced is the perception of being socially recognized on a positional, moral and emotional level among the Austrian population (see descriptive results)?

Are there any specific groups that experience greater or less recognition in one or another dimension (see latent classes of recognition)?

How can these groups be characterized? In other words, which factors shape the membership in the latent classes of social recognition derived from the explorative latent class analysis (see findings from multinomial regression analysis)?

Our third question on the factors that shape the membership in the identified classes is highly dependent on the classes that will be identified. Given that these classes are still unknown, we are not able to posit directed hypotheses at this point. Yet, we are able to derive some assumptions from existing literature on the association between different socio-demographic characteristics, attitudes, and the level of social integration.

As pointed out by Imbusch and Heitmeyer (2012, p. 14), the increase of precarious work and the working poor, the erosion of standard employment contracts, and the fear of social decline by the middle classes all threaten social solidarity in modern societies (for Austria see Hofmann 2016, p. 247). Apart from objective criteria, such as the integration in the job market, social integration is closely connected to perceptions, attitude formation, and personal experiences. In this respect, social comparison processes play an essential role because people tend to compare their monetary and non-monetary endowments, and their opportunities to gain access to markets with the success of other individuals and social groups in achieving these recognitions (see classical theories from Merton and Rossi 1968; Festinger 1954; Runciman 1966). Moreover, the degree of positional and moral recognition depends on the gap between one’s present situation and one’s expectations (Anhut and Heitmeyer 2000, p. 33). Perceived gaps typically result in feelings of deprivation or of getting an unfair share of a society’s goods, which are driving factors for social disintegration (Rippl and Baier 2005, p. 645). From this perspective, it can be assumed that Austrians with less income and a lower level of education who work in jobs with few opportunities or in precarious jobs are more likely to experience a lack of positional as well as moral recognition. This is because their interests have less of an impact on politics, than the interests of Austrians with higher incomes, better education, and/or better jobs.

According to the findings of Heitmeyer (2018), gender, migration background, and where one lives have a significant impact on a person’s life chances and therefore may be relevant for societal recognition. In regard to gender it is proven that women are more often confronted with economic scarcity because many women work part-time and are employed in the low-wage sector, and in general earn less than men (Verwiebe and Fritsch 2011). Since these facts are highlighted and critized more and more in public discourse, we expect that women feel less recognized than men, particularly positional recognition.

Verwiebe and Fritsch (2011) have also shown that people with a migration background are more likely to belong to the working poor, even if they are employed full-time. Hence, we expect that people with a migration background will report feeling less recognized than people without a migration background. Given that they are minorities in Austrian society, it is also likely that people with a migration background will lack moral recognition because their interests are not the priority of the well-established political parties (for Germany see Mikuszies et al. 2010).

As we know from classical literature, acquaintanceships and the likelihood for social isolation are more pronounced in urban areas, and especially in large cities, than in rural areas and smaller cities (Simmel 1903; Granovetter 1973). Hence, it can be assumed that Austrians living in larger cities feel emotionally unrecognized more often than people living in smaller cities or in rural areas. In addition, people’s age has a considerable impact on social isolation: In Vienna almost half of the people aged 60–75 live in a single person household, and the number of social contacts not only with their family, but also with friends distinctly decreases over age 70 (Rosenmayr and Kolland 2002, p. 255–256).

Coming back to the social disintegration approach of the Bielefeld research group, it has to be stressed that feelings of deprivation and the lack of recognition in one or another dimension, however, do not automatically lead to individual and group reactions and consequently, to social disintegration. Anhut and Heitmeyer conclude that low recognition in one dimension can be compensated by high recognition in another dimension (2005, p. 92). Individual and social structures of opportunities influence the possibilities of compensation (Anhut and Heitmeyer 2005, p. 92–93). However, each society can run into trouble, if perceived recognition in one or more dimensions declines (Heitmeyer 2007, p. 43).

3 Data and Methods

Our analysis is based on data from the Austrian Social Survey (SSÖ), which was conducted via face-to-face computer-assisted personal interviews during the second quarter of 2018. The random sample comprises 1200 respondents representative of the national Austrian population aged 18 and above. SSÖ itself has been conducted since 1986 and aims to collect and explore data about the Austrian population’s common set of basic values towards family, state, politics, occupation, and culture.Footnote 1 Sociologists from the Universities of Graz, Linz, Vienna, and Salzburg carried out five waves of the survey (1986, 1993, 2003, 2016, and 2018) and have been analyzing the perceptions and attitudes of the Austrian population since the 1980s.

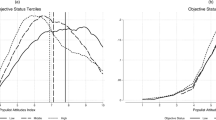

Table 2 provides an overview of the survey questions from the SSÖ 2018, which are used to operationalize the perception of integration in the three dimensions of recognition (positional, moral, and emotional). The items were formulated in accordance to the GMF-SurveyFootnote 2 (Heitmeyer, 2002) depicting relative deprivation in three dimensions. Reliability statistics and findings from exploratory factor analyses are provided in the notes of Table 2; descriptive results of these eight items are given in Fig. 1. In a first step, these items are used in an explorative latent class analysis to identify specific classes among the Austrian population. As mentioned above, we do not assume a general rank order of the three dimensions of social recognition but try to remain open for conducting explorative analyses. In a second step, we used the latent classes as dependent variables in a multinomial logistic regression model in order to find out which factors have an impact on the membership in the latent classes of social recognition. Due to this explorative character of the latent class analysis, we did not test hypotheses in the regression analysis, however, we suggested some general assumptions derived from theory and recent research in the last section. This two-step procedure allows distinguishing the subjective perspective on social recognition from a more objective approach. In this way it is possible to first identify latent classes of subjective recognition in an explorative manner (answering the 2nd research question), and to continue with the question of (more objective) determinants for belonging to one of these classes based on the results from the latent class analysis (answering the 3rd research question). The independent variables in the regression models, various sociodemographic and objective positional indicators and indicators of political participation, are described in the following paragraph. Finally, all results presented in this paper rely on weighted data.

3.1 Sociodemographic characteristics

As pointed out in Heitmeyer (2007), gender, migration background, and where one lives have a significant impact on life chances and therefore may be relevant for societal recognition. The same holds true for different age groups. We consider five different age groups: 18–29 years (17.2%), 30–44 years (23.9%), 45–59 years (28.5%), 60–74 years (19.5%), and 75–95 years (10.9%). As for gender, 51.4% of the respondents are women and 48.6% are men.Footnote 3 25% of the respondents live in a city with more than 100,000 inhabitants, 5% at the border of such a city, 5% in a city with 40,000 to 100,000 inhabitants, 25% in a small city (5000–40,000 inhabitants), 38% in a village, and 2% in a detached house in the countryside. We also include the region where one lives in the models (21.2% in Vienna, 19% in Lower Austria, 24.2% in Southern Austria (Burgenland, Styria, and Carinthia), 35.6% in Western Austria (Upper Austria, Salzburg, Tyrol, and Vorarlberg)). Migration background refers to respondents who were not born in Austria or whose father or mother was not born in Austria; 21% of the respondents have a migration background according to this definition (87.2% were born in Austria, 81.3% of the respondents report that their mother was born in Austria and 82.4% that their father was born in Austria).

3.2 Objective positional indicators

As “objective” indicators we consider the highest education attained, household income, individual income and self-rated financial well-being. The highest educational level achieved was divided into five categories: minimum compulsory schooling (15.1%), apprenticeship (43.7%), vocational secondary school (13.3%), higher school certificate (Matura; 15.5%) and tertiary educational degree (12.4%). The average net household income per month is € 2603.60 and the average net individual income € 1591.84. For both of the income variables we used dummy variables in order to include responses where some data was missing, which would be lost otherwise.Footnote 4 Because dummy variable adjustment can lead to biased estimates (Göthlich 2009, p. 127), we also calculated the model without the adjustment for missing data and compared the findings of the two models.Footnote 5

About 20.2% of respondents report that it is difficult or somewhat difficult to get by with their available household income. 49.2% have sufficient income whereas about 30.7% chose the response category “neither difficult nor easy”. As additional control variables, we also included the main groups of occupational status (ISCO 2008; nine different groups ranging from leading positions to unskilled workers)Footnote 6 and marital status in the models (59.4% married or in partnership, 22.3% single, 10.9% divorced, 7.2% widowed).Footnote 7

4 Descriptive Results

Fig. 1 provides an overview of perceived recognition for the items on the positional, moral, as well as emotional level in Austria. It indicates that perceived emotional recognition is the highest and moral recognition the lowest. The findings show that the majority of Austrians do not feel deprived since they believe to be neither disadvantaged nor privileged. Fewer than one in five Austrians consider themselves disadvantaged in society, yet almost a third believe that they receive less than their fair share (see Fig. 1).

Perceptions of moral recognition are distinctly lower than those involving access to material and cultural goods. More than half of the population does not think that they have any impact on the government and less than one third considers it useful to engage in politics. Regarding the social disintegration approach, Austrians seem to doubt that politics is good means of balancing conflicting interests in society. From this perspective communicative-interactive social integration is perceived as the biggest challenge in Austrian society. Yet, this is also a widespread phenomenon in several other European countries and thus not a unique characteristic of Austrian society (Moosbrugger et al. 2019, p. 570). Austrians feel most recognized in their social environment within the emotional dimension: More than 90% feel comfortable in their immediate surroundings and widely accepted by other members of the society. However, every tenth person also reports that it is hard to find their place in society (see Fig. 1).

5 Latent classes of recognition

In order to gain insights to what extent respondents feel recognized and how different dimensions of recognition are interrelated, we conducted a latent class analysis (LCA) using the R‑package poLCA (Linzer and Lewis 2011). LCA is based on probabilistic models to extract subgroups (classes) from a heterogeneous population. Therefore, we dichotomized all of the above-mentioned variables along the mean into above and below average recognition.Footnote 8 In an iterative process, we conducted different latent class models to identify the best-suited solution for the data at hand (Lazarsfeld and Henry 1968; Bacher et al. 2010). This approach allows identifying groups concerning “perceived” or “not perceived” recognition; i.e. whether “perceived” recognition is a given in all items, in some items, or in none. Fit statistics for the estimated models, the R‑Code and the correlation matrix of all single items can be found in the appendix (see Tables 4 and 5).

Findings from LCA support a four-class solution distinguishing Austrians perceiving themselves as almost entirely recognized from those seeing themselves as poorly recognized, and from two diametrically opposed groups in regard to the perceived positional and emotional recognition (see Fig. 2). The “almost entirely recognized” class is the largest group of respondents (predicted class membership: 47.1%) and consists of Austrians ranking above average on perceived positional, moral, and emotional recognition—with the exception of the median belief of not being able to influence the government. The smallest group is that of “the poorly recognized” (9.4%), as they rank below average in almost all items within the three dimensions. However, the poorly recognized on average think that they have more impact on the work of the government than Austrians from the other groups. The second largest group consists of Austrians that do not consider themselves disadvantaged in a monetary sense but report below average emotional recognition (29.4%). Members of this group feel accepted by other members of society and comparably less comfortable in their residential surroundings. In contrast, the fourth and last group (14.2%) sees itself monetarily disadvantaged but simultaneously somewhat accepted by its fellow citizens.

6 Findings from multinomial regression analysis

After describing the four classes derived from explorative latent class analysis, we use a multinomial logistic regression to identify factors that affect the membership in these classes. The dependent variable is the predicted membership in the four different groups of recognition:

- 1.

the almost entirely recognized,

- 2.

the poorly recognized,

- 3.

the emotionally unrecognized, and

- 4.

the positionally unrecognized.

Given the focus on disintegration, we use the almost entirely recognized (group 1) as a reference group and aim to estimate the influences on the less recognized classes. The independent variables consider sociodemographic characteristics (gender, age group, migration background, marital status, and place of residence) and positional characteristics (educational level, income, self-reported financial situation, and occupation). Table 3 shows the major findings of the multinomial logistic regression analysis. We report the effect sizes by means of odds ratios (Exp (B)) and statistical significance (p-values) for each of the three classes. An example is given in the note below Table 3.

Belonging to class 2, “poorly recognized”, depends on sociodemographic characteristics and positional indicators which was not the case for those who feel almost entirely recognized. A lack of recognition is most common among respondents living in a major city and having a migration background. People living in Lower Austria and Western Austria however, are even more likely to belong to this group than people living in the biggest city, Vienna. Being better educated and financially well-off lowers the chances of belonging to this group. Those with vocational secondary education and a high school education are particularly underrepresented in the poorly recognized group and thus feel more recognized compared to the lowest educated. Tentatively, workers also feel less recognized than people in higher occupational positions.

Membership in class 3 “emotionally unrecognized” depends on the place of residence, the educational degree and the subjective financial situation as well as marital status. A lack of emotional recognition is more likely when living in a city, especially when living in a larger city, but also to a lesser extent when living in a small city. In addition, those reporting having sufficient household income and those who attained a higher level of education have a lower probability of lacking emotional recognition. The actual household income and individual earnings, however, do not have any significant impact. Moreover, widowed persons perceive themselves less frequently as emotionally unrecognized than married people and people in partnerships. In contrast to the totally deprived, migration background does not play a role in belonging to the emotionally unrecognized group.

Similar to the poorly recognized, belonging to group 4 “positionally unrecognized” is also more common among those living in a large city but not among those living in smaller cities. In addition, people living in Southern Austria are overrepresented in this group. In regard to the positional indicators, the findings show that high school graduates and respondents with sufficient household income more frequently report not lacking positional recognition. This also applies to divorced people and younger Austrians aged below 45. Again, the migration background and the actual household and individual income do not play a role.

7 Discussion

Social recognition plays a decisive role in social integration, especially in increasingly differentiated and individualized societies that have faced severe crises in the last decade. Although Austrian society has experienced negative consequences of the worldwide financial crisis and cleavages between the political right and left, our analysis shows that the extent of social recognition remains high in large segments of the population. This is particularly the case for the dimension of perceived emotional recognition, and to a lesser extent also for perceived positional recognition. To a large degree, Austrians feel that they get what they deserve and feel appreciated in their social environment. At the same time, however, most groups are not convinced that they have an impact on Austrian politics, indicating a comparably low level of moral recognition.

A closer look at groups with varying levels of perceived recognition in Austrian society reveals that societal trends of pluralization have different effects. Urbanization and the exclusion or marginalization of migrants result both in lower levels of perceived integration, whereas education and a stable financial situation support social integration. According to our analysis, people with a migration background, less educated individuals, people feeling financially deprived, and urban dwellers display the most signs of social disintegration. For these groups it seems hard to compensate for a low level of recognition in one dimension by high recognition in another dimension (Anhut and Heitmeyer 2005). These groups seem to be affected the most by changing environments as they lack resources, leading to uncertainty which is, according to Heitmeyer (2018) a main reason for feelings of deprivation.

Reasons for the discrepancies between people living in rural and urban areas may be the different structures of integration and consequent isolation that have been addressed by classic sociologists such as Georg Simmel in his work on “The Metropolis and Mental Life” (1903) and Mark Granovetter (1973) in his concept of “The Strength of Weak Ties”. Anonymity in bigger cities, the agglomeration of “outlaws” and in part tougher competition in markets lead to looser structures of recognition and to larger gaps between the winners and losers of globalization. Due to the fact that bigger cities offer more job and educational opportunities, status expectations might also be higher, leading to the perception of more unfair gaps between achievements and expectations.

The perception of below average social recognition is also connected with the origin of the respondents and their migration background. Our findings show that people with a migration background still report more problems in finding their place within Austrian society. This seems to be particularly the case for non-German speaking immigrant groups that are usually overrepresented in the low-wage sector and often face spatial segregation, at least in Austrian cities. Further analyses of the SSÖ data concerning this group support this assumption as they show that 30.4% of respondents born in Turkey belong to the poorly recognized group, whereas only 7.7% of the respondents born in Germany and 7.7% of native Austrians do so. Regarding the results for respondents with a migration background from the Balkans, the Serbs are the only group that was more likely to consider themselves poorly recognized in society, with 14.4% viewing themselves in this way.

The feeling of being unrecognized is also interrelated with party preferences and the extent of social trust in other members of society (not included in the analyses of this paper). Corresponding with recent research (for Austria see Flecker and Kirschenhofer 2007), all of our latent classes lacking recognition in one or all three dimensions (emotional, positional and moral recognition) are more likely to vote for the right-wing freedom party FPÖ (Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs) or not to vote at all. This effect remains significant even when controlling for economic status and educational level. In addition, the feeling of not being recognized sufficiently in society is paralleled by a lower level of social trust. Yet, the group of the poorly recognized is the group with the highest perceived political (moral) recognition. A hypothetical explanation for this finding is that this group consists of a large number of right-wing party FPÖ voters. FPÖ party members became part of the government the year before the survey, thus the usually poorly recognized group may have experienced a sense of political recognition for the first time in a long while.

Despite its focus on social disintegration, our paper shows that the largest group in Austrian society perceives itself as almost entirely recognized, although even this group is not convinced that they have an impact on Austrian politics. From this perspective, economic and cultural disintegration processes in the sense of Heitmeyer and colleagues seem to be a manageable challenge, at least as far as the current perception of the Austrian population is concerned. Our findings rather suggest problems in regard to communicative-interactive social integration and thus a comparably high risk for political disintegration (Anhut and Heitmeyer 2000). This goes along with findings of Prandner and Grausgruber (2019, p. 399) who show that political efficacy in Austria has been on the decline since the 1980s. In the real world, the risk of political disintegration is of course, interrelated with economic and cultural aspects, as they are not completely independent from each other (e.g. Moosbrugger et al. 2019). Future research could put more emphasis on the empirical analysis of these interrelations in order to better understand the dynamics and consequences of social recognition.

Notes

The data can be downloaded free of charge from the Austrian Social Science Data Archive (https://aussda.at/daten-finden/). The method report with an elaborate description of the sample can be found there as well (Hadler et al. 2019).

GMF means group focused enmity (in German: Gruppenbezogene Menschenfeindlichkeit).

One respondent declared having a mixed gender. Including a single case in statistical analyses, however, is not meaningful. This person was thus excluded.

We utilized a dual-regressor procedure using an interaction term for missing cases for household income and earnings (see Hardy and Reynolds 2004). This method results in two regression parameters for each of the income variables: the first parameter indicates the effect of the income variable on the dependent variable; the second parameter indicates the difference between repliers and nonrepliers with regard to the dependent variable. Thus, we were able to keep all missing cases in the analysis.

The models with and without the adjustment for missing data lead to very similar results (more information can be found in the note to Table 3).

We utilize only the first level of the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) code which identified ten different groups: managers, professionals, technicians and associate professionals, clerical support workers, service and sales workers, skilled workers, craft and related trades workers, machine operators, elementary occupations, and armed forces (excluded) (Ganzeboom et al. 1992).

Although we consider objective positional indicators as independent variables and thus as impact factors to explain class membership in the latent classes of recognition, we cannot test the causality by means of this cross-sectional dataset. In line with our theoretical approach, we assume that deprivation affects social recognition, however, it is also plausible that low levels of social recognition foster processes of social disintegration.

This decision for comparing groups of above and below average recognition was driven by the idea that the degree of social recognition of the average Austrian is the most interesting starting point to assess the subjective status of social integration in Austria from a relational comparative perspective. It thus is a relative measure and not an absolute indicator of integration.

References

Allport, Gordon W. 1954. The nature of prejudice. Oxford: Addison-Wesley.

Anhut, Reimund, and Wilhelm Heitmeyer. 2000. Soziale Desintegrationsprozesse und ethnisch-kulturelle Konfliktkonstellationen. Weinheim: Juventa.

Anhut, Reimund, and Wilhelm Heitmeyer. 2005. Desintegration, Anerkennungsbilanzen und die Rolle sozialer Vergleichsprozesse. In Integrationspotenziale einer modernen Gesellschaft, ed. Wilhelm Heitmeyer, Peter Imbusch, 75–100. Wiesbaden: VS.

Aschauer, Wolfgang. 2017. Das gesellschaftliche Unbehagen in der EU. Ursachen, Dimensionen, Folgen. Wiesbaden: VS.

Bacher, Johann, Andreas Pöge, and Knut Wenzig. 2010. Clusteranalyse. Anwendungsorientierte Einführung in Klassifikationsverfahren. München: Oldenbourg.

Festinger, Leon. 1954. A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations 7(2):117–140.

Flecker, Jörg, and Sabine Kirschenhofer. 2007. Die populistische Lücke: Umbrüche in der Arbeitswelt und Aufstieg des Rechtspopulismus am Beispiel Österreichs. Berlin: edition sigma.

Friedrichs, Jürgen, and Wolfgang Jagodzinski. 1999. Theorien sozialer Integration. In Soziale Integration, ed. Jürgen Friedrichs, Wolfgang Jagodzinski, 9–43. Wiesbaden: VS.

Ganzeboom, Harry, Paul de Graaf, Donald Treiman, and Jan de Leeuw. 1992. A standard international socio-economic index of occupational status. Social Science Research 2(1):1–56.

Göthlich, Stephan E. 2009. Zum Umgang mit fehlenden Daten in großzahligen empirischen Erhebungen. In Methodik der empirischen Forschung, ed. Sönke Albers, Daniel Klapper, Udo Konradt, Achim Walter, and Joachim Wolf, 119–135. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Granovetter, Mark S. 1973. The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology 78(6):1360–1380.

Hadler, Markus, Franz Höllinger, and Johanna Muckenhuber. 2019. Social Survey Austria 2018 (SUF edition). https://doi.org/10.11587/ERDG3O. AUSSDA Dataverse, V2.0.

Hardy, Melissa, and John Reynolds. 2004. Incorporating categorical information into regression models. The utility of dummy variables. In Handbook of data analysis, ed. Melissa Hardy, Alan Bryman, 229–225. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Heitmeyer, Wilhelm. 1994. Das Desintegrations-Theorem. In Das Gewalt-Dilemma, ed. Wilhelm Heitmeyer, 26–69. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Heitmeyer, Wilhelm. 2002. Gruppenbezogene Menschenfeindlichkeit. Die theoretische Konzeption und erste empirische Ergebnisse. In Deutsche Zustände. Folge 1, ed. Wilhelm Heitmeyer, 15–34. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Heitmeyer, Wilhelm. 2007. Was hält die Gesellschaft zusammen? In Deutsche Zustände. Folge 5, ed. Wilhelm Heitmeyer, 37–50. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Heitmeyer, Wilhelm. 2018. Signaturen der Bedrohung. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Heitmeyer, Wilhelm, Sonja Kock, Julia Marth, Ulf Thöle, Helmut Thome, Andreas Schroth, and Denis van de Wetering. 2012. Gewalt in öffentlichen Räumen. Zum Einfluss von Bevölkerungs- und Siedlungsstrukturen in städtischen Wohnquartieren. Wiesbaden: VS.

Hofmann, Julia. 2016. Abstiegsangst und Tritt nach unten? Die Verbreitung von Vorurteilen und die Rolle sozialer Unsicherheit bei der Entstehung dieser am Beispiel Österreichs. In Solidaritätsbrüche in Europa, ed. Wolfgang Aschauer, Julia Hofmann, 237–257. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Honneth, Axel. 1992. Kampf um Anerkennung: Zur moralischen Grammatik sozialer Konflikte. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Imbusch, Peter, and Wilhelm Heitmeyer. 2012. Dynamiken gesellschaftlicher Integration und Desintegration. In Desintegrationsdynamiken, ed. Wilhelm Heitmeyer, Peter Imbusch, 9–23. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Imbusch, Peter, and Dieter Rucht. 2005. Integration und Desintegration in modernen Gesellschaften. In Integrationspotenziale einer modernen Gesellschaft, ed. Wilhelm Heitmeyer, Peter Imbusch, 13–74. Wiesbaden: VS.

Kaletta, Barbara. 2008. Anerkennung oder Abwertung. Über die Verarbeitung sozialer Desintegration. Wiesbaden: VS.

Lazarsfeld, Paul F., and Neil W. Henry. 1968. Latent structure analysis. Boston: Houghton Mill.

Linzer, Drew A., and Jeffrey B. Lewis. 2011. poLCA: an R package for polytomous variable latent class analysis. Journal of Statistical Software 42(10):1–29.

Marx, Karl. 2005. Das Kapital. Kritik der politischen Ökonomie. Der Produktionsprozess des Kapitals. Das Kommunistische Manifest. Stuttgart: Parkland Verlag.

Maslow, Abraham. 1943. A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review 50(4):370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346.

Merton, Robert K., and Alice S. Rossi. 1968. Contributions to the theory of reference group behaviour. In Social theory and social structure, ed. Robert K. Merton, 279–334. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Mikuszies, Esther, Jörg Nowak, Sabine Ruß, and Helen Schwenken. 2010. Die politische Repräsentation von schwachen Interessen am Beispiel von MigrantInnen. In Public Governance und schwache Interessen, ed. Ute Clement, Jörg Nowak, Christoph Scherrer, and Sabine Ruß, 95–109. Wiesbaden: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Moosbrugger, Robert, Johann Bacher, Antonia Kupfer, and Dimitri Prandner. 2019. Bildungsarmut und politische Teilhabe. In Handbuch Bildungsarmut, ed. Grudrun Quenzel, Klaus Hurrelmann, 555–584. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Peters, Bernhard. 1993. Integration moderner Gesellschaften. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Petzke, Martin, Kirsten Endrikat, and Steffen M. Kühnel. 2007. Risikofaktor Konformität. Soziale Gruppenprozesse im kommunalen Kontext. In Deutsche Zustände. Folge 5, ed. Wilhelm Heitmeyer, 52–76. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Prandner, Dimitri, and Alfred Grausgruber. 2019. Politische Involvierung in Österreich. In Sozialstruktur und Wertewandel in Österreich, ed. Johann Bacher, Alfred Grausgruber, Max Haller, Franz Höllinger, Dimitri Prandner, and Roland Verwiebe, 389–410. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Rippl, Susanne, and Dirk Baier. 2005. Das Deprivationskonzept in der Rechtsextremismusforschung. Eine vergleichende Analyse. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 57(4):644–666.

Rosenmayr, Franz, and Franz Kolland. 2002. Altern in der Großstadt – Eine empirische Untersuchung über Einsamkeit, Bewegungsarmut und ungenutzte Kulturchancen in Wien. In Zukunft der Soziologie des Alter(n)s, ed. Gertrud M. Backes, Wolfgang Clemens, 251–278. Wiesbaden: VS.

Runciman, Walter G. 1966. Relative deprivation & social justice: a study of attitudes to social inequality in 20th century England. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Simmel, Georg. 1903. Die Großstädte und das Geistesleben (The metropolis and mental life). Dresden: Permann.

Van Deth, Jan. 2009. Politische Partizipation. In Politische Soziologie, ed. Viktoria Kaina, Andrea Römmele, 141–161. Wiesbaden: VS.

Vermunt, Joren K., and Jay Magidson. 2000. Latent GOLD. User’s Guide. Belmont: Statistical Innovations.

Verwiebe, Roland, and Nina-Sophie Fritsch. 2011. Working poor: trotz Einkommen kein Auskommen; Trend- und Strukturanalysen für Österreich im europäischen Kontext. SWS-Rundschau 51(1):5–23.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Graz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Deciding on the number of latent classes represents a critical problem as typically several latent class models with various numbers of classes fit the data. Literature therefore supposes to base the decision on the number of classes on a combination of fit indices as well as theoretical knowledge (Bacher et al. 2010). Using log-likelihood allows for calculating average improvement comparing two solutions. The two most widely used measures are the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and Akaike information criterion (AIC). The preferred model to use is the one that minimizes values of the BIC and/or AIC. The most widely used criterion in latent class analyses is BIC as AIC tends to point to models too complex. cAIC accounts for this shortcoming by adding a weight concerning the sample size. In order to evaluate the selectivity of the latent classes R2-entropy (values from 0–1) is used. This measure can be read as explained entropy. Relative Entropy indicates the improvement of a more-class solution compared to the null-model. Basically, the closer entropy is to 1 the better the selectivity of the classes (Vermunt and Magidson 2000). The optimal latent class model therefore will have the lowest BIC, AIC, cAIC as well as highest entropy values and conceptual-interpretative meaning compared to other solutions. In our case this points to a four-class solution as BIC is the lowest, entropy the highest (though this is also the case for the six- and three-class-solution) and interpretability is given (see Table 4).

1.1 R-Code of latent class analysis (for the final solution of four classes)

f <- cbind(efficacy_dich, benachteiligt_dich, gerecht_dich, polengag_dich, angenommen_dich, platz_dichotom, hilfe_dich, sicher_dich) ~ 1 M1 <- poLCA(f, data=LCA, nclass=4, nrep=10, graphs=TRUE, maxiter=100000, na.rm=TRUE)

whereupon:

“f <- cbind (Y1, Y2, Y3)” … is the code for the variables to be included in the analysis. In our example eight variables are entered.

“M1 <‑ poLCA” regards the poLCA function that simulates the model

“nclass” is the the number of latent classes to assume in the model. Various numbers of classes (two- to six-class solutions) were tested. In our code, we present the final solution of four classes.

“nrep” defines the number of times to estimate the model.

“maxiter” is the maximum number of iterations.

“na.rm=TRUE” handles cases with missing values by removing cases (listwise deletion) before estimating the model.

1.1.1 Code for calculating entropy

entropy<-function(lc){ return(-sum(lc$posterior*log(lc$posterior), na.rm=T))} relative.entropy<-function(lc){ en<- -sum(lc$posterior* log(lc$posterior),na.rm=T) e<- 1-en/(nrow(lc$posterior)*log(ncol(lc$posterior))) return(e)}

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Eder, A., Hadler, M. & Moosbrugger, R. An enquiry into the importance of the perceived positional, moral and emotional recognition for social integration in Austria. Österreich Z Soziol 45, 213–233 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-020-00415-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-020-00415-y