Abstract

The gliding arc discharge plasma reactors are known as a source of non-equilibrium plasma at atmospheric pressure. In the present study, generation of dominant reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in gaseous and liquid phase in water by the compact gliding arc device (mini-GAD) and corresponding bactericidal effects were investigated. Water and phosphate buffer solutions were used as model liquids. Mini-GAD is a strong source of nitrogen oxides (up to 800 ppm NO and 200 ppm NO2) that result in high concentrations of nitrites and nitrates in water solutions. The highest bactericidal efficacy towards Escherichia coli was achieved for non-buffered water solution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electrical discharges effecting the generation of plasma activated media (PAM)/plasma activated water (PAW) via non-thermal plasma formation are considered to be a relatively energy efficient method for production of active species. Plasma methods effectively combine the contributions of high electric fields, UV radiation and active chemicals, leading to higher treatment efficiencies. Different designs of plasma reactors and variety of electrical discharge types (AC, DC, pulsed) generated either directly in water, in the gas introduced to water or above the water surface have been studied world-wide as possible methods for abatement of chemical and biological pollutants and for generation of PAM for further use for various applications in medicine, agriculture and biotechnology [1, 2].

The gliding arc (GA) is an electrical discharge formed between two or more divergent electrodes connected to a high voltage supply with high-velocity gas flow between the electrodes. The arc moves from the ignition zone along the electrodes until power system is not able to compensate losses resulting from the increasing volume of plasma. Then the arc extinguishes and is rebuilt again in the ignition zone. The first applications of the GA were described by Czernichowski and included flame overheating, air depollution from volatile hazardous compounds and initiations of various chemical processes [3]. Since then, many studies have been performed on the diagnostics and the applications for purification and production of selected chemical compounds. In recent years, there have also been many publications on the use of GA in low-temperature applications due to its potential to produce a non-equilibrium plasma at atmospheric pressure [2, 4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Du and Yan used GA with a mixture of distilled water and air to sterilize the isolated Escherichia coli, emphasizing the important role of the distance between the reactor and the sample [14]. Dasan et al. [15] decontaminated microbial residues from selected surfaces. Kim et al. used GA water reactor in conjunction with micro bubble generators and achieved a 6 logs reduction of colony-forming units of E. coli after 25 min of plasma treatment. The authors indicate that a high degree of oxidation was obtained due to the high content H2O2 combined with low-pH acidic water [16]. Studies carried out by Kamgang-Youbi et al. shows that GA allowed to obtain activated water containing large amounts of nitrites NO2−, hydrogen peroxide H2O2 and peroxynitrite ONOO− after 5 min of treatment with air. The activated species acting at acidic pH showed their destructive effects on the external walls of the Staphylococcus epidermidis, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Hafnia alvei and Saccharomyces cerevisiae and led to a decrease of their population on stainless steel and polyethylene surfaces [17]. Khani et al. [18] have shown that plasma processing using GA in inactivation peroxidase in tomatoes allowed preserving their nutritional value and is competitive in relation to other methods such as boiling water, steam and microwave. Burlica et al. used GA reactor for activation of water, using the systems above the surface and directly immersed in water. The first one allowed for the production of large quantities of molecular H2, oxygen ions and radicals, the second produced significant H2O2 [19]. Wang et al. [20] used GA to convert CO2 to CO and O2, indicating that the non-equilibrium nature of the discharge allows for much higher energy efficiency compared to classic thermal method. In work of Zhu et al., plasma catalysis using rotating GA allows for high conversion of methane CH4 from CO2-rich biogas [21]. Bidgoli et al. applied a pulsed reactor with an electric arc moving much faster than the gas flow to direct pyrolysis of CH4. Gliding sparks produced by self-stimulated acoustic waves allow for chemical conversion rate as high as 50%, having much better performance in comparison with the conventional pulsed plasmas [22]. Several authors have also successfully used GA reactors to stimulate the growth of seeds of plants, such as wheat, Thuringian Mallow or hemp [23,24,25].

An important part of research on these applications is the investigation of corresponding plasma chemistry responsible for the formation of RONS [26,27,28]. Research carried out by Patil et al. shown a significant role of O2 admixtures in the formation of NOx. For pulsed power supply, air mixtures were not only economically advantageous, but also allowed to obtain a lot of NO2 that increased with increasing O2 fraction [29]. Experiment on the sinusoidal and pulsed power supply for water spray GA carried out by Burlica and Locke has shown significant concentration of nitrates NO3− formed in water, when the working gases were air and N2, compared to very low levels obtained for Ar and O2. In case of H2O2, it was detected only for oxygen and argon due to the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide H2O2 by nitrite NO2− [30]. Porter et al. [31] reported that amount of H2O2 is sensitive to gas carrier in case of the formation of nitrogen oxides NOx, which can be produced from gas mixture, ambient air and oxygen species originating from water molecules. Both groups pointed out that higher power can cause energy wasting in thermal processes and the degradation of active species. Temperature measurements carried out by Hsieh et al. indicated the significant effect of O2 in the mixture, which increased the plasma temperature. The authors also pointed out that higher power can be related to the change in UV radiation and affecting H2O2 production [32]. Results obtained by Wang et al. [33] indicate that NOx production depends mainly on vibrational excitation of N2 and to a lesser extent on the thermal process. Additional information on active species in the reactor discharge chamber can be obtained using optical techniques. In the work of Sun et al., the images from the high-speed camera combined with the emission spectroscopy allowed the observation of the discharge emission and spatial distribution of species. In this case, excited N2 dominated upstream area near the electrodes, whereas downstream the main species were OH and NO [34].

The mini gliding arc discharge/device (mini-GAD) reactor is a low power consuming and compact design of the gliding arc supplied by high voltage–power supply with no separate ignition system, which can deliver certain part of the energy in the single cycle of plasma. Reactor is a portable device, designed especially for biomedical and agricultural applications and can be operated in different conditions, e.g. in various gas mixtures containing nitrogen and oxygen. It can be a good source of RONS in distant and off-grid applications. This work objective was to identify the dominant RONS generated by the mini-GAD in gaseous and liquid phases and evaluate its bactericidal effects.

Gliding Arc Plasma Generator

Compact experimental set-up with mini-GAD reactor used is schematically presented in Fig. 1.

The design of the reactor was selected based on our previous experimental work [9, 15]. It consisted of two 1.5 mm thick, and 10.4 cm long copper electrodes with 12° angle between them. Inter-electrode distance in the lower part forming initial discharge gap was 3 mm. AC high-voltage–power supply of parameters enlisted in Table 1 was utilized. The power supply is based on electronic high-voltage transformer of 50 Hz operation cycle. It consists of converter giving the series of 20 kHz, high voltage irregular microimpulses in 10 ms time span so transformer works in cut-off state for the next 10 ms. It is not possible to depict a high voltage signal of 20 kHz frequency in detail with our present measuring devices. It is caused by high irregularity of the signal caused by electrical arc discharges in the gap between electrodes. Arc itself also develops in irregular way depending on the gas flow rate, type of gas, electrode geometry, material and the level of surface microcorrosion. Measurements of voltage and current waveforms of the mini-GAD were performed using a Tektronix P6015A voltage probe, Tektronix P6022 current probe and Tektronix TDS 2024B oscilloscope. Typical voltage and current characteristic are depicted in Fig. 2. The current probe was placed on the same power wire and earthed at the same point as the voltage probe. In the arc-type discharge, the current flow is mainly related to the movement of electric charges in the arc column, i.e. the conductive current. In the case of GA, the frequency was 50 Hz; the displacement currents become important at much higher frequencies. For larger distances between the electrodes when the discharge ceased, the displacement current was not possible to register with the equipment used. However, due to the fact that this factor was not taken into account, we did not to use the term of the discharge current, and the measured current values refer to the current drawn from the power supply.

During the experiments, the gas flow was directed perpendicularly to the surface of the sample (liquid) set at a distance of 3 cm from the end of electrodes. The samples were treated with GA for 2 or 5 min. Temperature of the processed gas was measured using uninsulated K-type thermocouple with electronic temperature compensation multimeter at a distance of 3 cm from the end of electrodes. It ranged from 46 to 53 °C in dependence on the gas composition and the treatment time. The temperature of treated liquids did not exceed 28 °C.

Results and Discussion

Generation of Reactive Species in Gaseous Phase

Nitrogen and oxygen based gaseous products (NO, NO2, O3) generated by mini-GAD in atmospheric pressure N2/O2 mixtures in dependence on the molecular composition of feed gas were measured.

Mini-GAD is known as a good source for generation of relatively high concentrations of NO and NO2. Table 2 shows concentration of these two gaseous species in dependence of the initial oxygen O2 concentrations in the nitrogen N2 feed gas. Total gas flow rate was 7.3 L/min. The concentrations of NO2, NO, were measured using KANE Quintox electrochemical portable analyzer. In the mixture of N2 + 32%O2, NO concentration increased up to 749 ppm and NO2 to 195 ppm.

According to our present investigations, concentration of produced gaseous ozone O3 was low. When the discharge was operated in ambient air, ozone concentration amounted to 0.32 ppm only in nitrogen as a substrate gas.

In order to further investigate the reactive species generated by the mini-GAD in various gas mixtures, time-integrated optical emission spectroscopy (OES) was performed. The OES technique can provide valuable information on excited atomic and molecular states. It enables us to determine the rotational, vibrational and electronic excitation temperatures of the plasma and thus the level of non-equilibrium [35,36,37]. The rotational temperature derived from the emission spectra of the N2 second positive system (SPS) can be also used as an indicator of gas temperature [35].

For fast recording of time-integrated spectra of a broad spectral region, a two-channel compact emission spectrometer Ocean Optics SD2000 (200–1100 nm, resolution 0.6–1.7 nm) was used. Spectra of the discharge in three different positions along the electrodes were measured—at the place of the smallest electrode gap, where the discharge ignites and starts to propagate (position 1), in the middle of the electrodes (position 2) and approximately 1 cm from the end of the electrodes (position 3, depicted in Fig. 1). The measured spectra were compared with simulated spectra produced by Specair software [35] in order to determine rotational and vibrational temperatures of emitting species.

In the UV range (Fig. 3), the second positive system of molecular nitrogen (N2 SPS) emission dominates in the spectra in all studied gas mixtures. The first positive system of nitrogen (N2 FPS) emission was also observed in all mixtures in the visible part of the spectra (Fig. 4), but here, the emission of O and N atomic lines was stronger.

The emission spectra of mini-GAD generated in mixture of N2 + 21% O2 measured at position 2 (middle of the discharge propagation). The simulated spectra were obtained using Specair software. The N2 FPS emission shown on the figure was calculated with Tr = 1500 K and Tv = 6000 K. The emission spectra of atomic lines were simulated using electronic temperature 35,000 K, which could be much different from the real electron temperature in the plasma

The time-integrated OES study confirmed that mini-GAD generates highly reactive non-equilibrium plasma, since the rotational temperature Tr derived from the N2 SPS spectra (ranging from 650 to 2500 K depending on the mixture and the measurement position) was always much lower than the corresponding vibrational temperature (Tv = 3500–5500 K). Figure 5 shows that in all mixtures, the Tr was the lowest in the position 1 (beginning of the discharge propagation) and the highest in the position 3 (end of the propagation). The opposite trend was observed in case of Tv (data not shown), though the changes were less significant. These results thus indicate that the plasma generated by mini-GAD gradually approaches the thermal equilibrium during its propagation, but this equilibrium is never reached.

The evolution of rotational temperature along the propagation of the mini-GAD in all studied gas mixtures. The rotational temperature was derived from the emission spectra of N2 SPS. The position (x-axis) indicates the place between the electrodes, where the emission spectra was measured (refers to Fig. 1)

Figure 5 also indicates that the temperature evolution depends on the gas composition.There are several other possible mechanisms that could change the evolution of Tr and Tg in various gas mixtures. Admixtures in N2 gas can introduce new heating mechanisms [38, 39], or faster transfer of energy stored in N2 vibrational levels to the translation energy of molecules [40]. With scarce data set and with characteristic uncertainty above 100 K, we could only speculate about the real cause of the observed influence of the gas composition on estimated Tr. Moreover, we should emphasize that Tr derived from the N2 second positive emission system may not be perfectly identical to the kinetic gas temperature Tg.

On the other hand, the results of the OES (Figs. 3, 4, 5) help us to understand chemical activity of the mini-GAD. The observed emission spectra are similar to those of DC driven transient spark (TS) discharge [36]. In transient spark, the atomic lines dominate also in the visible part of the emission spectrum, whereas in the streamer corona the N2 FPS system dominates and the emission of the atomic lines is weak. The TS is initiated by the streamer that leads to the formation of short (~ 10 ns) high current (~ A) spark pulse [41]. The time-resolved OES study and imaging of the TS revealed that the emission from the excited molecular nitrogen is generated mostly during the streamer phase, and the emission of the atomic lines comes mainly from the spark phase [42, 43]. During the TS spark phase the heating of the gas up to 2000–3000 K was also observed, high electron density (= high degree of ionization) [44], and high degree of atomization [45]. We assume that the plasma generated by mini-GAD has similar chemical activity as the plasma generated during the spark phase of the TS discharge. This assumption is based not only on the similarity of observed emission spectra but also on fact that in both discharges, the nitrogen oxides NOx are dominant gas phase products, while the generation of O3 is negligible.

High density of atomic N and O (based on strong emission of atomic lines, Fig. 4) and increase of the temperature up to ~ 2000 K (Fig. 5) can explain the dominant NOx formation. Under these conditions, the NO species are generated probably mainly via Zeldovich mechanism (Eqs. 1 and 2):

The NO2 species are generated by subsequent oxidation of NO via reaction (Eq. 3)

In air-like mixtures the generation of ozone (Eq. 4) is possible, however here it is strongly suppressed by increased gas temperature.

Further details on the air plasma chemistry leading to NOx formation in the transient spark discharge can be found in [1, 2, 46].

Generation of Reactive Species in Aqueous Phase

Deionized water (DI) (< 3 µS/cm, pH ~ 5.5), synthetic tap-like water (W) (8.5 mM NaH2PO4 phosphate solution, ~ 600 μS/cm, pH ~ 5.5) designated to mimic the natural conductivity of tap water and a weak phosphate buffered solution (PB) (2 mM Na2HPO4/KH2PO4, ~ 550 μS/cm, pH ~ 7) represent the liquid samples treated by mini-GAD. In PB solution, the range of pH was adequately buffered close to physiological pH value; providing nearly the same initial conductivities as in synthetic tap water. The initial temperature of all solutions was ambient.

In all analyzed cases, the oxidants measurement results obtained with DI and W were similar so only the results obtained with W, which actually simulate real conditions are presented in the following figures.

In the experiment, 3 mL of liquid sample was placed in 5 cm Petri dish located in a position of 3 cm from the electrodes’ tips to the water surface and treated for 2 or 5 min with mini-GAD plasma. The treatment times were selected based upon our previous results on seeds treatment using the presented device due to its chemical and biological effects. The treatment period ranging from 2 to 5 min was the most beneficial for the germination energy and germination capacity of Lavatera thuringiaca [23]. Conductivity and pH of treated solutions are summarized in Table 3. All systems have shown similar response, in DI and in W after plasma treatment pH dropped to about 3.3 while in PB solution it decreased only down to 4.1. In all cases conductivity increased after the plasma treatment.

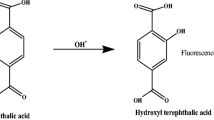

Just for verification and rough evaluation, a semi quantitative measurement of dissolved ozone O3 was performed using indigo blue method with minimal detection limit 0.05–0.5 mg/L. Indigo should be decolorised by dissolved ozone. However, even without the presence of O3 indigo could have been affected by interference with other RONS present in plasma treated water, for instance via formation of OH radicals, probably formed as a decay product from peroxynitrites. More detailed discussion on the suitability of indigo blue method for O3 detection in plasma activated water can be found in [46]. Approximately 0.8 mg/L of “apparent” O3 was recorded for 5 min GA treatment in DI.

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was measured by colorimetric method using TiOSO4 (Titanium(IV) oxysulfate) solution, which reacts with H2O2 and gives a yellow-coloured product with the absorption maximum at 407 nm. The detection limit for this method is ~ 5 µM [47]. The method is independent of the pH since the measurement of H2O2 is performed in strongly acidic solution of sulfuric acid. Due to possible H2O2 decomposition by NO2− under acidic conditions, the solution of sodium azide NaN3 (60 mM) was added to the samples prior to mixing with titanium sulfate reagent to eliminate decomposition of H2O2 [26]. The measurement results are depicted in Fig. 6. It shows that non-acidic environment of PB resulted in slightly lower concentrations of H2O2 compared to non-buffered solutions (W, DI) where acidification occurred. The highest concentrations were obtained in the case of pure N2 and pure O2 gases, what is especially visible for 5 min plasma treatment. Low concentration of H2O2 in N2/O2 gas mixture may indicate occurrence of competitive quenching reactions, most likely the reaction of H2O2 and NO2− at acidic conditions leading to peroxynitrous acid ONOOH (for detailed chemistry, we refer to [1, 26, 27]).

Nitrites (NO2−) and nitrates (NO3−) were measured by the colorimetric and selective Griess assay (Nitrate/Nitrite Colorimetric Assay Kit, Cayman Chemicals). The detection limit of the assay is approximately 1 µM for NO2− and 2.5 µM for NO3−. This method is based on the reaction of NO2− with Griess reagents under acidic conditions resulting into formation of deep purple azo compound with the absorption maximum at 540 nm. Figure 7 and 8 present the concentrations of NO2− obtained in W and PB solutions after plasma treatment. Slightly higher concentrations of NO2− were achieved in non-acidic PB than W, as the acceleration of subsequent disproportionation of NO2− into NO3− occurs under acidic conditions, especially at pH below 3.5.

Nitrate NO3− detection is also possible by using Griess assay, but prior to mixing of the sample with reagents, the reduction of NO3− into NO2− is necessary. Nitrate/Nitrite Colorimetric Assay Kit contains the nitrate reductase enzyme, which allows the NO3− reduction to NO2−. The sample after reduction gives the total NO −x concentration (NO2− + NO3−) and the NO3− concentration can be evaluated after subtraction of NO2− concentration. Higher concentrations of NO3− after Mini-GAD treatment were detected in PB solution. Nitrites NO2− and nitrates NO3−concentrations were significantly higher when N2 was used as the substrate gas. Generated gaseous NOX were efficiently transferred into the liquid phase adding the complexity of nitrogen oxidation cycle in liquid. Elaborated details on gas-phase air plasma chemistry, the transport of species into water and subsequent liquid-phase chemistry can be found in [1].

Bactericidal Effects

Mini-GAD was employed to reduce deposited bactericidal load on stainless steel, silicone and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) surfaces and also planktonic bacteria in the liquid media.

In the experiment of surface decontamination from bacteria, sterile Teflon coupons (15 × 10 × 2 mm) were inoculated by three 10 µL droplets of Gram-negative Escherichia coli BW 25113 overnight culture in Miller’s modified Lysogeny Broth (LB, Biolab) with initial concentration 1.21 × 107 ± 16.1 CFU/mL (CFU—Colony Forming Unit). Contaminated samples were subsequently dried by gas flow from the mini-GAD and treated by GAD plasma for 2 or 5 min exposure time 3 cm from tip of its electrodes. Discharge treated samples were placed inside test tubes with 10 mL of physiological saline solution and vortexed to remove bacteria from surface to solution. Then solutions were serially diluted in 1/3 LB and plated on Petri dishes. All plates were incubated for 24 h at 35 °C, than the colonies were counted. The control samples were treated the same way except the (discharge) plasma was not turned on.

The results of this experiment are presented in Fig. 9. Log reduction (logarithmic reduction) of bacterial concentration after 2 min exposure to the mini-GAD was highest in N2: 1.93 ± 0.23, similar value was in air like mixture: 1.77 ± 0.26 and finally: 1.11 ± 0.17 in O2. However, these differences were not statistically significant (Kruskal–Wallis test, on the level of significance α = 0.05). In all three gas mixtures discharge decontamination efficiency increased significantly after 5 min exposure time. It ranged 3.48 ± 0.39 in N2, 3.62 ± 0.39 in N2 + 21% O2, and 2.93 ± 0.10 in O2, again these differences were not statistically significant. No thermal effects (3 cm) from mini-GAD were observed.

The results are in a good agreement with our previous findings [48]. For the case of microorganisms deposited on solid surfaces, 5 min treatment at 0.5 m3/h of N2 flow rate resulted in reduction of E. coli population on stainless steel, silicone and PET surfaces about 0.91, 3.82 and 2.00 log (CFU/mL), respectively. 3.13, 3.12 and 2.55 log (CFU/mL) reductions using air were achieved on stainless steel, silicone and PET surfaces, respectively. Moreover, 5 min treatment using nitrogen resulted in reduction of Gram-positive S. epidermis population on stainless steel, silicone and PET surfaces about 3.60, 3.02 and 2.67 log (CFU/mL), respectively. In the case of using air, 3.28, 1.63 and 3.65 log (CFU/mL) reductions were achieved on stainless steel, silicone and PET surfaces, respectively.

For the liquid media, bactericidal effect was observed on plaktonic form of E. coli (CCM 394). The suspensions were prepared by the dissolution of bacteria precultivated on gelatin disc in 10 mL of desired aqueous solutions. After overnight cultivation (~ 18 h at 37 °C) were bacteria active and vital. Bacterial suspension with the initial concentrations ~ 106–107 CFU/mL were prepared by mixing 5 mL of the overnight suspension and 45 mL of the desired aqueous solution. The number of living bacterial cells in the suspensions after mini-GAD treatment and also the control suspensions is evaluated immediately after plasma treatment by classical thermostatic cultivation on Petri dishes. The results of the bactericidal reduction are depicted in Fig. 10. Generally, relatively weak bactericidal effect was observed (< 2 log for W solution).

Buffered (PB) solutions resulted in the weakest effect, as the bactericidal effect of plasma treated solutions seems to be correlated with and superposed by the decrease in pH value. In W solution the superposing of bactericidal effect is likely to be caused by peroxynitrites ONOO− or peroxynitrous acid ONOOH, and reaction between H2O2 and NO2−, described in detail in [1, 26, 27, 49]. Under increased acidity, decomposition reaction of peroxynitrous acid ONOOH leads to the formation of OH and NO radicals contributing to the reduction of E. coli. In addition to this mechanism, high NO2− concentrations at acidic pH (Fig. 7a) may support the antibacterial effect of acidified nitrite, i.e. nitrous acid [26]. According to previous findings, the ionic strength of water and PB was sufficient to rule out bacteria destruction caused by osmotic stress in these solutions.

Conclusions

We introduced and characterized a compact mini gliding arc source (mini-GAD) which is able to generate high concentrations of NOx in gaseous phase, which can be further transferred to the liquid media. The optical emission spectra characterized the GAD in various gas mixtures (N2, air, O2) and enabled us to determine the typical plasma temperatures and reactive species leading to the formation of NOx. It was found that the NOx formation mechanism in GAD is similar to that in the spark phase of the transient spark discharge. Synthetic water mimicking the natural conductivity of tap water and phosphate buffer solution were used to evaluate the potential of the mini-GAD to form aqueous active species: hydrogen peroxide H2O2, nitrites NO2−, nitrates NO3− and dissolved ozone O3 in water. Obtained concentrations of NO2− and NO3− were higher in the case of PB solution compared with water, especially for 5 min of plasma treatment and the presence of N2 in the substrate gas. On the other hand, the highest concentration of H2O2 was obtained in water, where the highest bactericidal activity was also observed. Mini-GAD was also demonstrated as an efficient tool for surface decontamination.

References

Machala Z, Tarabová B, Sersenová D, Janda M, Hensel K (2019) Chemical and antibacterial effects of plasma activated water: correlation with gaseous and aqueous reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, plasma sources and air flow conditions. J Phys Appl Phys 52:034002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/aae807

Pawłat J (2013) Electrical discharges in humid environments. Generators, effects, application. Politechnika Lubelska, Lublin

Czernichowski A (1994) Gliding arc: applications to engineering and environment control. Pure Appl Chem 66:1301–1310. https://doi.org/10.1351/pac199466061301

Kalra CS, Gutsol AF, Fridman AA (2005) Gliding arc discharges as a source of intermediate plasma for methane partial oxidation. IEEE Trans Plasma Sci 33:32–41. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPS.2004.842321

Pawłat J, Diatczyk J, Stryczewska HD (2011) Low-temperature plasma for exhaust gas purification from paint shop: a case study. Przegląd Elektrotechniczny 87:245–248

Misra NN, Tiwari BK, Raghavarao KSMS, Cullen PJ (2011) Nonthermal plasma inactivation of food–borne pathogens. Food Eng Rev 3:159–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12393-011-9041-9

Czernichowski A, Czernichowski P (2010) GlidArc-assisted cleaning of flue gas from destruction of conventional or chemical weapons. Environ Prot Eng 36:37–45

Fridman A, Nester S, Kennedy LA et al (1999) Gliding arc gas discharge. Prog Energy Combust Sci 25:211–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0360-1285(98)00021-5

Stryczewska HD, Jakubowski T, Kalisiak S et al (2013) Power systems of plasma reactors for non-thermal plasma generation. J Adv Oxid Technol 16:52–62

Brisset J-L, Pawlat J (2016) Chemical effects of air plasma species on aqueous solutes in direct and delayed exposure modes: discharge, post-discharge and plasma activated water. Plasma Chem Plasma Process 36:355–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11090-015-9653-6

Malik MA, Ghaffar A, Malik SA (2001) Water purification by electrical discharges. Plasma Sources Sci Technol 10:82. https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-0252/10/1/311

Abdelmalek F, Gharbi S, Benstaali B et al (2004) Plasmachemical degradation of azo dyes by humid air plasma: yellow Supranol 4 GL, Scarlet Red Nylosan F3 GL and industrial waste. Water Res 38:2339–2347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2004.02.015

Watanabe T, Itoh H, Ishii Y (2001) Preparation of ultrafine particles of silicon base intermetallic compound by arc plasma method. Thin Solid Films 390:44–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-6090(01)00923-3

Du C, Yan J (2017) Surface sterilization by atmospheric pressure non-thermal plasma. In: Du C, Yan J (eds) Plasma remediation technology for environmental protection. Springer, Singapore, pp 61–73

Dasan BG, Onal-Ulusoy B, Pawlat J et al (2017) A new and simple approach for decontamination of food contact surfaces with gliding arc discharge atmospheric non-thermal plasma. Food Bioprocess Technol 10:650–661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11947-016-1847-2

Kim HS, Cho YI, Hwang IH et al (2013) Use of plasma gliding arc discharges on the inactivation of E. Coli in water. Sep Purif Technol 120:423–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2013.09.041

Kamgang-Youbi G, Herry J-M, Meylheuc T et al (2018) Microbial decontamination of stainless steel and polyethylene surfaces using GlidArc plasma activated water without chemical additives. J Chem Technol Biotechnol 93:2544–2551. https://doi.org/10.1002/jctb.5608

Khani MR, Shokri B, Khajeh K (2017) Studying the performance of dielectric barrier discharge and gliding arc plasma reactors in tomato peroxidase inactivation. J Food Eng 197:107–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2016.11.012

Burlica R, Kirkpatrick MJ, Locke BR (2006) Formation of reactive species in gliding arc discharges with liquid water. J Electrost 64:35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elstat.2004.12.007

Wang W, Mei D, Tu X, Bogaerts A (2017) Gliding arc plasma for CO2 conversion: better insights by a combined experimental and modelling approach. Chem Eng J 330:11–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2017.07.133

Zhu F, Zhang H, Yan X et al (2017) Plasma-catalytic reforming of CO2-rich biogas over Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalysts in a rotating gliding arc reactor. Fuel 199:430–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2017.02.082

Majidi Bidgoli A, Ghorbanzadeh A, Lotfalipour R et al (2017) Gliding spark plasma: physical principles and performance in direct pyrolysis of methane. Energy 125:705–715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2017.02.144

Pawlat J, Starek A, Sujak A et al (2018) Effects of atmospheric pressure plasma generated in GlidArc reactor on Lavatera thuringiaca L. seeds’ germination. Plasma Process Polym 15:1700064. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppap.201700064

Roy NC, Hasan MM, Kabir AH et al (2018) Atmospheric pressure gliding arc discharge plasma treatments for improving germination, growth and yield of wheat. Plasma Sci Technol 20:115501. https://doi.org/10.1088/2058-6272/aac647

Sera B, Sery M, Gavril B, Gajdova I (2017) Seed germination and early growth responses to seed pre-treatment by non-thermal plasma in hemp cultivars (Cannabis sativa L.). Plasma Chem Plasma Process 37:207–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11090-016-9763-9

Lukes P, Dolezalova E, Sisrova I, Clupek M (2014) Aqueous-phase chemistry and bactericidal effects from an air discharge plasma in contact with water: evidence for the formation of peroxynitrite through a pseudo-second-order post-discharge reaction of H2O2 and HNO2. Plasma Sources Sci Technol 23:015019. https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-0252/23/1/015019

Machala Z, Tarabova B, Hensel K et al (2013) Formation of ROS and RNS in water electro-sprayed through transient spark discharge in air and their bactericidal effects. Plasma Process Polym 10:649–659. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppap.201200113

Bruggeman PJ, Kushner MJ, Locke BR et al (2016) Plasma–liquid interactions: a review and roadmap. Plasma Sources Sci Technol 25:053002. https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-0252/25/5/053002

Patil BS, Peeters FJJ, van Rooij GJ et al (2018) Plasma assisted nitrogen oxide production from air: using pulsed powered gliding arc reactor for a containerized plant. AIChE J 64:526–537. https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.15922

Burlica R, Locke BR (2008) Pulsed plasma gliding-arc discharges with water spray. IEEE Trans Ind Appl 44:482–489. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIA.2008.916603

Porter D, Poplin MD, Holzer F et al (2009) Formation of hydrogen peroxide, hydrogen, and oxygen in gliding arc electrical discharge reactors with water spray. IEEE Trans Ind Appl 45:623–629. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIA.2009.2013560

Hsieh KC, Wang H, Locke BR (2016) Analysis of electrical discharge plasma in a gas–liquid flow reactor using optical emission spectroscopy and the formation of hydrogen peroxide. Plasma Process Polym 13:908–917. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppap.201500204

Wang W, Patil B, Heijkers S et al (2017) Nitrogen fixation by gliding arc plasma: better insight by chemical kinetics modelling. Chemsuschem 10:2145–2157. https://doi.org/10.1002/cssc.201700095

Sun ZW, Zhu JJ, Li ZS et al (2013) Optical diagnostics of a gliding arc. Opt Express 21:6028–6044. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.21.006028

Laux CO, Spence TG, Kruger CH, Zare RN (2003) Optical diagnostics of atmospheric pressure air plasmas. Plasma Sources Sci Technol 12:125. https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-0252/12/2/301

Machala Z, Janda M, Hensel K et al (2007) Emission spectroscopy of atmospheric pressure plasmas for bio-medical and environmental applications. J Mol Spectrosc 243:194–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jms.2007.03.001

Fantz U (2006) Basics of plasma spectroscopy. Plasma Sources Sci Technol 15:S137. https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-0252/15/4/S01

Rusterholtz DL, Lacoste DA, Stancu GD et al (2013) Ultrafast heating and oxygen dissociation in atmospheric pressure air by nanosecond repetitively pulsed discharges. J Phys Appl Phys 46:464010. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/46/46/464010

Popov NA (2011) Fast gas heating in a nitrogen–oxygen discharge plasma: I. Kinetic mechanism. J Phys Appl Phys 44:285201. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/44/28/285201

Komuro A, Ono R, Oda T (2010) Kinetic model of vibrational relaxation in a humid-air pulsed corona discharge. Plasma Sources Sci Technol 19:055004. https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-0252/19/5/055004

Janda M, Martišovitš V, Machala Z (2011) Transient spark: a dc-driven repetitively pulsed discharge and its control by electric circuit parameters. Plasma Sources Sci Technol 20:035015. https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-0252/20/3/035015

Janda M, Machala Z, Niklová A, Martišovitš V (2012) The streamer-to-spark transition in a transient spark: a dc-driven nanosecond-pulsed discharge in atmospheric air. Plasma Sources Sci Technol 21:045006. https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-0252/21/4/045006

Janda M, Martišovitš V, Hensel K, Machala Z (2016) Generation of antimicrobial NOx by atmospheric air transient spark discharge. Plasma Chem Plasma Process 36:767–781. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11090-016-9694-5

Janda M, Martišovitš V, Hensel K et al (2014) Measurement of the electron density in transient spark discharge. Plasma Sources Sci Technol 23:065016. https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-0252/23/6/065016

Dvonč L, Janda M (2015) Study of transient spark discharge properties using kinetic modeling. IEEE Trans Plasma Sci 43:2562–2570. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPS.2015.2452947

Tarabová B, Lukeš P, Janda M et al (2018) Specificity of detection methods of nitrites and ozone in aqueous solutions activated by air plasma. Plasma Process Polym 15:1800030. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppap.201800030

Eisenberg G (1943) Colorimetric determination of hydrogen peroxide. Ind Eng Chem Anal Ed 15:327–328

Tučeková Z, Koval’ová Z, Zahoranová A et al (2016) Inactivation of Escherichia coli on PTFE surfaces by diffuse coplanar surface barrier discharge. Eur Phys J Appl Phys 75:24711. https://doi.org/10.1051/epjap/2016150590

Machala Z, Hensel K, Akishev Y (2012) Plasma for bio-decontamination, medicine and food security. Springer, Berlin

Acknowledgements

This study has been supported by Polish-Slovak Bilateral Cooperation Programme (PlasmaBioAgro) PPN/BIL/2018/1/00065 and SK-PL-18-0090; Slovak Research and Development Agency Grants: APVV-0134-12 and APVV-17-0382; M-era.net PNANO4BONE-NCN, Project No. 2016/22/Z/ST8/00694; Slovak Grant Agency VEGA 1/0419/18 and networking action CEEPUS CIII-AT-0063.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Pawłat, J., Terebun, P., Kwiatkowski, M. et al. Evaluation of Oxidative Species in Gaseous and Liquid Phase Generated by Mini-Gliding Arc Discharge. Plasma Chem Plasma Process 39, 627–642 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11090-019-09974-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11090-019-09974-9