Abstract

Main conclusion

The complexes involving MYBPA2, TT2b, and TT8 proteins are the critical regulators of ANR and LAR genes to promote the biosynthesis of proanthocyanidins in the leaves of Lotus spp.

Abstract

The environmental impact and health of ruminants fed with forage legumes depend on the herbage's concentration and structure of proanthocyanidins (PAs). Unfortunately, the primary forage legumes (alfalfa and clover) do not contain substantial levels of PAs. No significant progress has been made to induce PAs to agronomically valuable levels in their edible organs by biotechnological approaches thus far. Building this trait requires a profound knowledge of PA regulators and their interplay in species naturally committed to accumulating these metabolites in the target organs. Against this background, we compared the shoot transcriptomes of two inter-fertile Lotus species, namely Lotus tenuis and Lotus corniculatus, polymorphic for this trait, to search for differentially expressed MYB and bHLH genes. We then tested the expression of the above-reported regulators in L. tenuis x L. corniculatus interspecific hybrids, several Lotus spp., and different L. corniculatus organs with contrasting PA levels. We identified a novel MYB activator and MYB-bHLH-based complexes that, when expressed in Nicotiana benthamiana, trans-activated the promoters of L. corniculatus anthocyanidin reductase and leucoanthocyanidin reductase 1 genes. The last are the two critical structural genes for the biosynthesis of PAs in Lotus spp. Competition between MYB activators for the transactivation of these promoters also emerged. Overall, by employing Lotus as a model genus, we refined the transcriptional network underlying PA biosynthesis in the herbage of legumes. These findings are crucial to engineering this trait in pasture legumes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Legumes (Fabaceae) are critical components of natural and agricultural ecosystems and are the primary source of plant protein for human and livestock nutrition. Pasture legumes' nutritional value must be improved to meet the rising world's demand for cheap and safe livestock food products and genuinely sustainable livestock farming (Lüscher et al. 2014; Notenbaert et al. 2021). Proanthocyanidins (PAs), known as condensed tannins, are polymeric flavonoids that significantly affect legume quality (Mueller-Harvey et al. 2019). By binding dietary proteins, PAs slow down their fermentation in the rumen and, in turn, increase the conversion rate of plant proteins into animal proteins while decreasing ruminal bloating and the emission of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere (Aerts et al. 1999; Hess et al. 2006; Patra and Saxena 2010). PAs also exert an anti-parasitic effect against ruminant and non-ruminant gastrointestinal parasites. Still, when their concentration is too high, they reduce the voluntary intake by the animals and lower the nutritional value of forage diets (Mueller-Harvey et al. 2019). Unfortunately, only a few forage legumes of temperate climates synthesize these metabolites in their edible herbage; most do it in the seed coat (Paolocci et al. 2007). Thus, understanding the genetic control of PAs is vital to engineer the biosynthesis of these metabolites in the herbage of the most valuable forage legumes (such as Medicago and Trifolium spp., Lotus tenuis), currently one of the primary goals of forage breeders worldwide.

The PA biosynthetic pathway has been characterized in many species. The building blocks of these polymers are the flavan-3-ols epicatechins and catechins that are synthesized by the reduction of anthocyanidins and leucoanthocyanidins via anthocyanidin reductase (ANR) and leucoanthocyanidin reductase (LAR), respectively (Tian et al. 2008). More recently, it has also been shown that the biosynthetic routes to epicatechin starter and extension units can differ and that LAR plays a crucial role in producing epicatechin starter units (reviewed in Lu et al. 2022). This additional role of LAR explains the higher levels of epicatechin rather than catechin units found in species overexpressing functional LARs (Liu et al. 2013).

The regulation of flavonoid genes occurs mainly at the transcriptional level. Members of the R2R3-MYB, the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH), and WD-repeat families (Davies and Schwinn 2003; Lepiniec et al. 2006) form the MYB-bHLH-WDR (MBW) complex that regulates the organ- and tissue-specific expression of the different branches of the flavonoid pathway (Davies and Schwinn 2003; Lepiniec et al. 2006; Dubos et al. 2010; Xu et al. 2015; Lafferty et al. 2022). The MYB components provide branch specificity to this complex (Broun 2005). In Arabidopsis, AtMYB123/TT2 is the R2R3-MYB that targets the MBW complex to the PA pathway (Nesi et al. 2001, 2002). Orthologue genes of AtMYB123 have been characterized in Lotus japonicus (Yoshida et al. 2010b), Medicago spp. (Verdier et al. 2012), and Trifolium spp. (Hancock et al. 2012). Furthermore, other MYB proteins related to transcriptional activation of PA biosynthesis have been described: MYB5 from Medicago truncatula (Liu et al. 2014), MYBPA1 and MYBPA2 from Vitis vinifera (Bogs et al. 2007) or MYB7 from Prunus persica (Terrier et al. 2008). MYBs, like MYB134 from Trifolium repens and MYB1 from Fragaria x ananassa, have been shown to act as repressors of PA-genes in legumes (Albert 2015; Paolocci et al. 2011). These metabolites accumulate in an organ-specific manner that depends upon a finely tuned balance between activator and repressor proteins (Ma and Constabel 2019; Zho et al. 2019).

Despite the wealth of knowledge on PA biosynthesis in legume and non-legume species, no significant steps forward have been made in inducing PAs to agronomical valuable levels in the herbage of the most important forage legumes by trans-genetics (Zhou et al. 2015). Nevertheless, we note that most of the genes employed for this purpose are from species that do not naturally accumulate PAs in the herbage, such as L. japonicus, M. truncatula, and Arabidopsis (Li et al. 1996; Debeaujon et al. 2003). Thus, they might operate within complexes specific to reproductive rather than vegetative organs. Only very recently, levels of foliar PAs sufficient to reduce ammonia and methane production in the rumen in vitro assays were reached in Trifolium repens, provided that the exogenous TaMYB14-1 transcription factor (TF) was expressed in recipient germplasm already committed to synthesizing anthocyanins in leaves (Roldan et al. 2022). To search for PA-specific TFs regulating the synthesis of these metabolites in the foliage of agronomically important forage species, here we exploited the genetic variability of two Lotus spp. polymorphic for the PA trait, namely L. tenuis and Lotus corniculatus. Being inter-fertile and unable to accumulate anthocyanins in their leaf blades and shoot apexes, these two species offer the advantage of assessing the levels of PAs and those of structural and regulatory genes of this pathway in their progeny and anthocyanin-free germplasm contexts (Robbins et al. 2003; Escaray et al. 2014; Aoki et al. 2021). The latter point is crucial in light that PA and anthocyanin genes can be co-regulated through the same core MBW regulatory complex (Yue et al. 2023), somewhat hampering the identification of PA-specific regulators from those controlling multiple branches of the flavonoid pathway. Thus, the transcriptomes of the shoot apexes of a cultivar of L. tenuis grown in South America and with negligible levels of PAs (Escaray et al. 2012) and that of a wild, diploid genotype of Lotus corniculatus, which accumulates high levels of PAs throughout the leaf mesophyll and in the stems (Escaray et al. 2014) have been compared and differentially expressed (DE) MBW components retrieved. Then, their expression was assessed in leaves of L. tenuis x L. corniculatus interspecific hybrids, which showed intermediate levels of PAs compared to the two parents and F2 progeny with contrasting levels of leaf PAs (Escaray et al. 2014, 2017). Additionally, the expression of the MBW components retrieved above has been investigated in Lotus species and different L. corniculatus organs with varying levels of PAs. In essence, to avoid any possible interference or artifact due to ectopic gene expression, while taking into consideration the potential effects of environmental cues, the expression of the candidate PA regulators has been investigated in genome contexts that did not experience an ectopic expression of any given regulators and were grown under different environmental conditions. Finally, the candidates whose expression correlated with the levels of PAs in any comparison made, regardless of plant-growing conditions, were evaluated to form in vitro stable MBW complexes and induce the transcription of Lotus ANR and LAR1 promoters. Overall, new actors and various MBW complexes with different relevance in controlling PA accumulation in the herbage of legumes have been characterized. Present findings are crucial to breeding bloat-safe forage legumes.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and cDNA sample sets

The Lotus spp. plant material employed in the present study was categorized as “PA-rich” and “PA-poor” genotypes according to the levels of PAs in their herbage. “PA-rich” genotypes showed more than 4 mg PA/g DW and were characterized by PA-accumulating cells throughout the leaf mesophyll. Conversely, in the “PA-poor” genotypes, the PA-accumulating cells were observed around the vascular tissues of only some of them, and the levels of PAs in these species were consistently lower than 1.5 mg/g DW (Escaray et al. 2014).

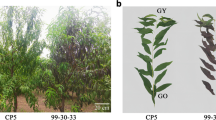

For RNAseq analysis, “PA-rich” and “PA-poor” apical shoots were collected from the diploid L. corniculatus accession “Charlii” and L. tenuis commercial cultivar “Pampa INTA”, respectively (Escaray et al. 2014). Fig. S1 provides information on RNA isolation and plant growing conditions of this material. The figure also gives information on the origin and features of the four sample sets employed to validate the involvement of PA biosynthesis of the regulatory genes selected after RNA-seq analysis. This was tested by investigating the correlation of their expression with PA levels and the expression profiles of main structural genes of this pathway in Lotus spp. accessions (sample sets 1–3) and L. corniculatus organs (set 4) polymorphic for this trait.

RNA-seq analysis and functional annotation of transcripts

Samples for RNA-seq analysis (n = 3) were prepared as described in the TruSeq® RNA Sample Preparation Guide (Illumina). High-performance, paired-end (2 × 100 bp) sequencing was performed on an Illumina Hiseq 1500 apparatus by the Institute of Agrobiotechnology of Rosario (Rosario, Argentina). Low-quality RNA-Seq reads (QScore < Q30) detected using FastQC (Version 0.11.2) were discarded (Andrews 2010). De novo assembly was performed by merging the high-quality reads using Trinity software (Grabherr et al. 2011) with a minimum contig length of 200 bases and a k-mer size of 25 bp. Functional annotation of assembled transcripts was performed by homology search (BLAST/Uniprot and SwissProt), protein domain identification (HMMER/PFAM), protein signal peptide and transmembrane domain prediction (signalP/tmHMM), and annotation databases search (eggnog/GO/Kegg) using Trinotate pipeline (Bryant et al. 2017).

The reads' FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase Million) value was determined by the eXpress abundance estimation method (Roberts and Pachter 2013). Fold change for selected transcripts was estimated by FPKM of L. corniculatus / FPKM of L. tenuis.

Selection and cloning of candidate MBW regulators

As reported above, all predicted proteins annotated as MYBs were selected. In addition, the two transcriptomes underwent a local Position-Specific Iterated BLAST (PSI-BLAST) using as queries the reference MYB proteins reported in Table S1. Likewise, this last strategy was used to identify possible bHLH and WDR members of the PA MBW regulatory complex.

Primer pairs (listed in Table S2) for each candidate regulator were designed to amplify their ORF from both species by RT-PCR and verify their sequence by Sanger. Neighbor-joining trees for each protein family were built using Mega 7 (Kumar et al. 2016).

Gene expression analysis by qRT-PCR

The relative expression of PA structural and regulatory genes was verified on different sample sets by qRT-PCR, as reported by Escaray et al. (2017). The genes and relative primer pairs investigated by qRT-PCR are given in Table S2. The relative gene expression analysis was performed according to Pfaffl et al. (2002). The correlation analysis was performed using the Pearson test. All statistical analysis was performed using the Infostat program (Di Rienzo et al. 2011).

Proanthocyanidin determination

An aliquot of samples ground for RNA isolation for RNA-seq analysis and for synthesizing the third and fourth sets of cDNAs was retained for PA determination performed as described in Escaray et al. (2012).

Yeast-two-hybrid assay

Protein–protein interactions were evaluated by Y2H assay. The full CDS of L. corniculatus TT8, TT2b, MYBPA2, and MYB5, along with the control genes that code for MYBPA1 from grape and Sn (bHLH) from maize were fused either to the Gal4-DBD in the pDEST32 vector or to the Gal4-AD in pDEST22 vector using the Invitrogen Gateway® Recombination Cloning Technology and following standard procedures. Once verified by sequencing, the final constructs were used to transform yeast following the LiAc/ssDNA/PEG protocol (Gietz 2014). Selection of transformed yeasts was performed by growing on Synthetic Defined (SD) medium without Leu (for yeast strain Y187 transformed with pDEST32 vectors) or Trp (for yeast strain Y2HGold transformed with pDEST22 vectors). Subsequently, diploid cells obtained by mating were selected on an SD medium lacking both Leu and Trp. Protein–protein interaction assays were performed in SD plates lacking Leu, Trp, and His in the presence of different concentrations of 3-amino triazole (Sigma-Aldrich).

Promoter transactivation assay

To evaluate the activation by the candidate MYB and bHLH TFs of the two key genes for the epicatechin and catechin branches of the PA pathway, a genome fragment of 800–1200 bp upstream of the translation start codons of ANR and LAR1 was PCR amplified from DNA samples of L. corniculatus "Charlii" using the primers reported in Table S2. These primers were designed on the ANR and LAR1 promoters cloned by genome walking from the tetraploid S41 L. corniculatus genotype (Paolocci et al. unpublished results). The resulting PCR products were digested using BamHI and NcoI enzymes (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) and cloned into pGreenII 0800 LUC plasmid using T4 DNA Ligase (Promega). Both constructs, ANR promoter::Firefly luciferase reporter and LAR promoter::Firefly luciferase reporter were verified by sequencing and then transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58 containing the pSoup helper plasmid.

pDONR221 entry vectors containing LcTT8 and the candidates MYBs LcTT2b, LcMYBPA2, and LcMYB5 were recombined via LR reaction (LR Clonase II, Invitrogen) into pAlligator1 plasmid. Once verified by sequencing, the resulting cassettes were used to transform A. tumefaciens strain C58.

An aliquot of 0.5 OD (600 nm) from each Agrobacterium fresh culture was pellet by centrifugation (20 min at 5000 g) and resuspended in 2 ml of infiltration solution (10 mM MES, 10 mM MgCl2, and 100 µM acetosyringone). Combinations of Agrobacterium cultures for Nicotiana benthamiana infiltration were prepared by mixing equal amounts of each one. Young leaves of 2-week-old N. benthamiana plants (n = 3) cultivated in growth chambers were infiltrated. Leaf samples were extracted with Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega) two days post infiltration. Then the ratio of Firefly luciferase to Renilla luciferase fluorescence was measured using Dual-Glo® Luciferase Assay System (Promega) on a luminometer (Luminoskan Ascent, Thermo Scientific).

Results

Illumina Hiseq 1500 sequencing, de novo assembly of L. corniculatus and L. tenuis transcriptomes and functional annotation

After adapter sequences were trimmed and sequences shorter than 90 bases removed, 200,136,278 and 181,191,352 clean paired-end reads remained for de novo assembly by Trinity software. Reads assembly yielded 123,301 contigs (91,530 unigenes) with an average length of 880 bp from L. corniculatus and 109,953 contigs (80,911 unigenes) of 930 average bp length from L. tenuis. In L. corniculatus, 61,318 assemblies were > 500 bp and 35,369 > 1 kb, whereas in L. tenuis, 57,469 were > 500 bp and 34,021 > 1 kb. The quality of sequencing and assembly was verified by comparing the nucleotide sequences of 1αEF, PAL, CHS, DFR, ANS, ANR, LAR1, LAR2, and MATE1 genes from both Lotus spp. with those previously reported (Escaray et al. 2014, 2017); in all cases, the identity between these sequences was always higher than 95%.

Using BLASTx search in Uniprot databases, 94,005 (76.2%) and 82,760 (75.3%) transcripts were annotated from L. corniculatus and L. tenuis, respectively. Using a TransDecoder Software, 52,401 predicted proteins for L. corniculatus and 47,775 for L. tenuis were obtained, which were 43,854 (83.6%) and 39,688 (83.1%) after BLASTp search in Uniprot databases. Finally, predicted proteins were also functionally annotated by search in the pfam database; by this way, 34,191 (65.2%) and 31,275 (65.5%) sequences for L. corniculatus and L. tenuis, respectively, were annotated.

Identification of putative PA regulators in L. corniculatus and L. tenuis

A total of 280 and 257 putative MYB transcripts resulted from annotation and BLAST analyses of the L. corniculatus and L. tenuis transcriptomes, respectively. About 20 of them per species clustered with MYBs controlling PAs or anthocyanins in different plant species (Fig. S2). These were re-sequenced in both species and then employed to build a flavonoid-specific Neighbor-joining tree, which displayed seven subgroups, named from A to G (Fig. 1). MYB activators of PA biosynthesis formed subgroups A and G, the activators of PA, anthocyanins and flavonoids subgroups B and F, activators of anthocyanin subgroup C. In contrast, subgroup E included MYB11 and MYB12, reported to be as general activators of flavonoid biosynthetic genes, and subgroup D repressors of either PA and/or anthocyanin pathways.

R2R3MYBs considered in the present study. a Evolutionary relationships of selected R2R3-MYB proteins. The Neighbor-Joining method inferred the evolutionary history (Saitou and Nei 1987). The optimal tree with the sum of branch length = 48.22591070 is shown. The evolutionary distances were computed using the p-distance method (Nei and Kumar 2000) and are in the units of the number of amino acid differences per site. The analysis involved 284 amino acid sequences. All positions with less than 95% site coverage were eliminated. There were a total of 162 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7 (Kumar et al. 2016). Reference sequences are detailed in Table S1. Branches in blue color indicate clusters that include MYB activators of proanthocyanidin (PA) biosynthesis; in purple MYBs reported to activate both PA and anthocyanin biosynthesis; in red MYB activators of anthocyanins; in light brown MYB activators of flavonoids; in green MYB repressors of both PA and anthocyanidins. In brackets are given the subgroups of the reference R2R3MYB Arabidopsis genes as designated in Strake et al. (2001). b FPKM (fragments per kilobase of exon model per million reads mapped) of selected MYBs from L. corniculatus and L. tenuis transcriptomes

Subgroup A, which corresponds to subgroup 5 (SG5) according to the MYB classification in Arabidopsis, included the L. corniculatus and L. tenuis homologs to LjTT2a, LjTT2b, LjTT2c, and TaMYB14, the contig LjSGA_029658 from L. japonicus reported as LjMYB123 (Shelton et al. 2012), and to MtPAR (Verdier et al. 2012). According to the FPKM values, the transcript levels of homologs to LjTT2a, LjTT2b, LjTT2c, and TaMYB14 were higher in L. corniculatus than in L. tenuis (Fig. 1b). Coupled to the evidence that TT2b was not detected in the transcriptome of L. tenuis, the about seven-fold higher transcript levels of TT2a were also of interest. The level of MYB123 transcripts was only slightly higher in the PA-rich Lotus spp., whereas no transcripts were found for PAR in the L. tenuis transcriptome. Subgroup G included MYBPA proteins with two candidates for each Lotus species here considered, named MYBPA1 and MYBPA2. Transcript levels of MYBPA2 and MYBPA1 were higher (2.1 fold) or slightly higher (1.3 fold) in L. corniculatus than in L. tenuis, respectively (Fig. 1b). The first MYBPA1 protein was characterized in grape as a PA regulator and belongs to a separate clade from the SG5 and SG6 R2R3 MYB genes (Bogs et al. 2007). Within subgroups B and F, there were the homologs to PAP from L. japonicus and MYB5 from various species, respectively. If the level of PAP transcripts was similar in the two transcriptomes, MYB5 was 5.7 fold higher in L. corniculatus (Fig. 1b).

Subgroup C, corresponding to the SG6 in Arabidopsis, included MYB proteins related to anthocyanin regulation (Table S1), such as MYB75 and MYB90 (known as PAP1 and PAP2, Borevitz et al. 2000) with orthologues of both MYB75 and MYB90 found in both Lotus spp. transcriptomes. The FPKM values of MYB75 were similar between the two species, and those of MYB90 were much higher in L. tenuis (80 fold).

Subgroup E included proteins, classified as SG7 in Arabidopsis, related to the regulation of flavonoid biosynthesis (Table S1) with two MYBs, MYB11 and MYB12 (Fig. 1a). MYB11 was ten-fold more expressed in L. tenuis; on the contrary, the level of MYB12 transcripts was slightly higher in L. corniculatus (Fig. 1b).

Since the present work was focused on identifying MYB activators of PAs in the foliage of Lotus spp, those belonging to subgroups A, B, C, F, and G were objects of further analyses. However, as shown in the phylogenetic tree, orthologues of repressors of PAs and/or anthocyanins were found in the two transcriptomes. More specifically, six Lotus MYBs here identified in subgroup D clustered with well-characterized repressors of the SG4 (Fig. 1a). This included MYBs highly similar to T. repens MYB132, MYB133, and MYB134, repressors of PAs and anthocyanins, and MYB7 and MYB4 repressors phenylpropanoid compounds (Albert 2015). In general, the transcript levels of these MYBs were slightly higher in L. corniculatus than in L. tenuis except for MYB134, which was 2.5-fold more expressed in L. corniculatus and of MYB133, which was not found in the L. tenuis transcriptome (Fig. 1b).

Regarding bHLH members, homologs from both L. corniculatus and L. tenuis were retrieved when their transcriptomes were scanned for TT8, GL3/EGL3, and TAN1 proteins. The levels of TT8, which showed 99% of identity with the LjTT8 and LcTT8 described previously (Escaray et al. 2017), were 5.2 fold higher in L. corniculatus. In contrast, those of GL3/EGL3, and TAN1 were slightly higher in L. tenuis (Fig. S3). Finally, despite several reference sequences being used as queries, only a TTG1 gene in both Lotus spp were retrieved. It showed high similarity with the LcTTG1 gene previously cloned (Escaray et al. 2017) and TTG1 from L. japonicus. The transcripts levels of TTG1 in FPKM values were 13.2 ± 1.2 in L. corniculatus and 14.8 ± 0.8 in L. tenuis in the face of the fact that the former species showed 18.1 ± 2.2 mg PAs / g DM and the latter only 0.8 ± 0.2 mg.

Relative expression of candidate genes for PA accumulation in different Lotus spp. accessions

The first three sample sets included “PA-rich” and “PA-poor” Lotus genotypes (Table S3). The expression of genes coding for structural enzymes of the PA pathway evaluated in the third sample set showed significantly higher levels for CHS, DFR, ANS, ANR, LAR1, LAR2, and MATE genes in “PA-rich” genotypes (Table S4). Better still, a positive correlation (r > 0.95; P value ≤ 0.0001) emerged between the relative expression of all these genes and the levels of PAs. These findings keep and extend what emerged from the analyses of the first and second sample sets (Table 1, Escaray et al. 2014, 2017).

The same three sets of cDNA have been then employed to assess the expression levels of all candidate activators identified by the transcriptomic analysis reported above. The heatmap in Fig. 2 shows the relative expression of each of these genes and the levels of total PAs in each sample of the three cDNA sets. The statistics beyond this map are provided in Table S5. From the correlation analysis between PA and gene expression levels (Table 1), the only MYB of subgroup A that showed a significant correlation with PAs in any sample set was TT2b. MYB14 and PAR showed a significant correlation with PAs only in the first set, MYB123 and TT2a both in the first and third sets, whereas TT2c only in the third one.

PA content and relative expression levels of regulatory genes in PA polymorphic Lotus spp. genotypes. The blue color indicates total proanthocyanidins (PA) levels. Red color indicate Log2 FoldChange of the gene expression levels, calculated using the 2−(ΔΔCt) algorithm and refered to L. tenuis (mean from three biological replicates). Lc C: L. corniculatus “charlii”, LtxLc: L. tenuis x L. corniculatus, Lc G: L. corniculatus “Granada”, Lc SG: L. corniculatus “San Gabriel”, Lb: L. burtii, and Lj: L. japonicus

Interestingly, the other MYBs that showed a significant correlation with PAs in any setting were MYBPA2 (subgroup G; r ≥ 0.92, P value ≤ 0.0001) and MYB5 (subgroup F; r ≥ 0.93, P value ≤ 0.0001). Focusing on genotypes that did not derive from interspecific hybridization, it turned out that the MYBs consistently upregulated in the three “PA-rich” L. corniculatus genotypes compared to the “PA-poor” Lotus ones were TT2b and MYBPA2 only (Table S5). Regarding the bHLH and WDR partners, TT8 always showed a significant correlation with PA in any comparison, whereas TTG1 did not (Table 1).

The involvement of TT2b, MYBPA2, MYB5, and TT8 in PA synthesis was confirmed by the positive correlation of their expression with those of ANR, LAR1, and MATE in any sample set analyzed (Table S6). Nevertheless, MYB5 exhibited a positive correlation with CHS and DFR, MYBPA2 with DFR, and TT8 with ANS in these sets. A positive correlation also emerged between the expression of TT2a and that of ANS, ANR, and LAR1 (P value ≤ 0.01) in any sample set.

PA and gene expression levels in L. corniculatus seedlings

The levels of PAs in L. corniculatus plants depend on tissues and organs (Escaray et al. 2014). In the seedlings of L. corniculatus “Charlii”, PA-accumulating cells were present through mesophyll and around the vascular tissues since their first leaves. Still, they were absent in the cotyledons (Fig. S4). Thus, the relative expression of structural genes related to PAs, TTG1, TT8, and different MYBs was compared between the seedlings shoot apex and the cotyledons (Fig. S4b, c). All genes coding for late structural enzymes of the PA pathway showed higher relative expression in shoot apex than in cotyledon, particularly LAR1 and LAR2, 92.6 and 192.8 folds, respectively. Concerning the candidates of MBW complex, no difference was observed for TTG1, whereas TT8 was 46.9 folds higher expressed in the shoot apex. Likewise, MYB14, MYB123, TT2a, TT2b, TT2c, PAR, PAP, MYBPA2, and MYB5 were more expressed in shoot apex than in cotyledons, with fold changes ranging from 287.0 (TT2a) down to 2.99 (MYB5). No differences were observed for both MYBs of subgroup C (MYB75 and MYB90), whereas the relative expression of MYBPA1 was higher in cotyledons.

Functional evaluation of the interaction between selected Lotus MYBs and bHLHs by Y2H assay

MYBs have to interact with bHLH proteins to form an active MBW complex. All the R2R3MYBs are likely involved in the regulation of flavonoids retrieved from the transcriptomes of the two Lotus spp. showed the conserved amino acid signature ([D/E]Lx2[R/K]x3Lx6Lx3R) for the interaction with bHLH proteins (Fig. 3a). The yeast two-hybrid assays were thus employed to experimentally confirm the interaction between L. corniculatus TT8 and the L. corniculatus MYBs that showed a significant correlation with the PA levels in any sample set investigated TT2b, MYBPA2, and MYB5. As a control, MYBPA1 from grapes and Sn from maize were used. The first is an important regulator of PA biosynthesis in grapes which induced a metabolic diversion from anthocyanins to PAs in transgenic tobacco flowers (Bogs et al. 2007; Passeri et al. 2017); the second is an activator of anthocyanins in maize, which promoted the expression of the PA genes, thereby increasing the number of PA accumulating leaf cells and the overall PA levels, when ectopically expressed in L. corniculatus (Damiani et al. 1999; Paolocci et al. 2007). All the LcMYBs, but one (LcMYB5), strongly interacted with bHLH members (LcTT8) as much as VvMYBPA1 did. Interestingly, LcMYB5 weakly interacted with LcTT8, but it did it strongly with Sn (Fig. 3b, c). In M. truncatula MYB5 forms with MYB14, TT8, and WD40-1, a quaternary MBW complex to activate the ANR and LAR promoters (Liu et al. 2014), thus the Y2H assays were performed to test if the presence of other MYBs could mediate the interaction of MYB5 with TT8. This hypothesis had to be ruled out, at least for what concerns LcTT2b, LcMYBPA2, and VvMYBPA1, since LcMYB5 did not interact with any of these major PA regulators (Fig. 3c).

MYB-bHLH interactions. a Phylogenetic tree of selected MYBs and R2R3 conserved motif (MEME). Black triangles indicate the [D/E]Lx2[R/K]x3Lx6Lx3R motifs important for the interaction with bHLH proteins. b Interactions between LcTT8 fused to GAL4 DNA binding domain (BD) and VvMYBPA1, LcTT2b, LcMYBPA2, or LcMYB5 fused to GAL4 activation domain (AD) evaluated by yeast two-hybrid assay. Two serial dilutions per yeast clone grown in control media (-L -W), selective media (-L -W -H) and selective media supplemented with 3-aminotriazole (3-AT) at three different concentrations (1, 3 and 5 mM) are shown. c Interactions of LcMYB5 fused to the GAL4 BD and LcTT2b, LcMYBPA2, VvMYBPA1, LcTT8, or Sn fused to the GAL4 AD evaluated by yeast two-hybrid assay. MYBPA1 from V. vinifera and Sn from Z. mays were used as MYB and bHLH positive control, respectively. Dilutions are as in b

Functional analysis of the transactivation of the ANR and LAR1 promoters by candidate LcMYB and LcbHLH PA regulators

To test whether and to what extent the candidate MYBs and bHLH regulate the transcription of the critical genes for PA accumulation in Lotus spp., the promoters of the genes coding for functional enzymes in catalyzing the synthesis of catechin and epicatechin units were cloned from both L. corniculatus and L. tenuis species. These genes were ANR and LAR1 but not LAR2, since the enzyme coded by this gene could not yield catechins from leucoanthocyanidins (Paolocci et al. 2007). The about 430 bp long regions upstream of the coding sequence of ANR of L. tenuis and L. corniculatus showed a high level of identity between each other (98.6%). PLACE predicted two bHLH-recognizing elements (BREs) and one MYB-recognizing element (MRE) in the ANR promoter from both species, respectively (Fig. S5). The about 710 bp long regions upstream of the coding sequence of L. tenuis and L. corniculatus LAR1 also showed high identity (93.9%). Additionally, the LAR1 promoter of the two species showed four and two conserved BREs and MREs cis-elements, respectively. Notably, the two MREs overlapped with the two central BREs. It is worth noting that all the BREs and MREs found in the promoters of both ANR and LAR1 genes from L. corniculatus and L. tenuis were also found in the promoters of the same genes from L. japonicus (Fig. S5). This evidence paves the way for experiments to test the hypothesis suggesting that different transcriptional rates of these two genes between PA-rich and poor Lotus spp. does not depend on mutations of their regulatory sequences.

N. benthamiana leaves were employed to test the capacity of the selected regulators to transactivate the promoters of ANR and LAR1 from the diploid L. corniculatus plant (Fig. 4). The infiltration of a single MYB, whatever it was, or of TT8 alone was not sufficient to significantly activate the luciferase reporter gene when driven either by ANR or LAR1 promoter. Conversely, this activation was achieved when TT8 was co-infiltrated with an MYB, regardless of whether the MYB being tested was TT2b, MYBPA2, or MYB5. Yet, the activation of both ANR and LAR1 promoters was significantly higher in leaves co-infiltrated with TT2b-TT8 or MYBPA2-TT8 than with MYB5-TT8, and the luciferase signal was always about an order of magnitude lower when the reporter gene was driven by the promoter of LAR1 than ANR, regardless of the combination of TFs used.

Promoter transactivation assays. a Activation of ANR promoter by the L. corniculatus MYBs. b activation of LAR1 promoters. MYBs are given in different blue color scales, TT8 in red. Means were obtained from three biological replicates; different letters among bars indicate significant differences (P value ≤ 0.01; Duncan's test)

To test whether multiple MYBs cooperate to activate these promoters, the combinations of two or three MYBs with TT8 were evaluated. The activation of ANR increased when TT2b and MYBPA2 were simultaneously employed with respect to the sole TT2b; the same did not occur for LAR1 (Fig. 4). Conversely, when MYB5 replaced one of these two MYBs, the luciferase signals decreased; regardless of the promoter used. This decrement was more pronounced when MYB5 was tested with TT2b than with MYBPA2 on ANR promoters. Adding MYBPA2 to TT2b-MYB5-TT8 raised the luciferase signal to values found with MYPA2-TT8 and MYBPA2-TT2b-TT8 combinations. Conversely, on the LAR1 promoter, the decrement due to the presence of MYB5 was slightly more severe when it was used in combination with MYBPA2 and TT8 than with TT2b and TT8, and the negative effect of MYB5 was rescued when it was co-infiltrated with MYBPA2-TT2b and TT8 (Fig. 4).

Discussion

The expression of TT2b, MYBPA2, MYB5, and TT8 correlates with the levels of PA in Lotus spp.

The synthesis of PAs is mainly regulated at the transcriptional level by the ternary MBW complex (Baudry et al. 2004). TT2 from Arabidopsis is the best-studied MYB controlling PA biosynthesis, which in this species occurs only in the seed coat and via the ANR branch (Nesi et al. 2001; Abrahams et al. 2003). Three TT2 orthologs (TT2a, TT2b, and TT2c) have been characterized in L. japonicus (Yoshida et al. 2010b) and L. corniculatus (Escaray et al. 2017). The three LjTT2s are involved in the induction of LjANR but not of LjLAR, and they show different expression patterns and interaction abilities with TT8 and TTG1 (Yoshida et al. 2008, 2010b). Additionally, complementation analysis of Arabidopsis tt2 mutants showed that M. truncatula PAR and MYB14 proteins are the functional orthologs of TT2 and that AtMYB5 but not MtMYB5 rescues PAs in the seeds of this mutant (Liu et al. 2014; Xu et al. 2014). MYB14 has also been characterized in Trifolium spp (Hancock et al. 2012) and L. corniculatus, but its expression did not mirror the levels of PA in the Lotus genotypes tested (Escaray et al. 2017). To search for additional PA players and herbage-specific MBW complexes, here we compared the shoot transcriptomes of two Lotus species, L. corniculatus and L. tenuis, which displayed a marked difference in PA accumulation in these organs. The commitment of candidate genes in this trait has been confirmed by studying their expression levels in L. corniculatus x L. tenuis hybrids and their progeny and Lotus species and organs with different commitments for PA synthesis grown under different environmental conditions. Our phylogenetic analysis has sorted about 20 MYBs per transcriptome into the seven clusters (named from A to G) related to PA or anthocyanin regulators. Within subgroup A, only TT2b shows a positive correlation with ANR, LAR1, and MATE expression and with the levels of PAs in any sample set and condition investigated. Putative Lotus PA regulators are also found in clusters F and G, containing the VvMYBPA and AtMYB5 reference proteins, respectively. The Lotus MYB5 positively correlates with the levels of PA accumulation and the expression of genes from CHS down to MATE in any set investigated. MYBPAs from different species are known as solid activators of the PA pathway (Bogs et al. 2007; Akagi et al. 2009; Ravaglia et al. 2013). MYBPA1 from grape rescues PA accumulation in Arabidopsis tt2 mutant. However, Arabidopsis does not have a MYBPA1 orthologue, and it activates the promoters of two PA-specific biosynthetic genes, VvLAR and VvANR. Still, it could not turn on VvUFGT, which is necessary for anthocyanin biosynthesis (Bogs et al. 2007). Additionally, the Lotus MYBPA1 and MYBPA2 cluster with MYBPA1.1 from Vaccinium myrtillus (Fig. S6) which has been very recently shown to exert a dual role in co-regulating PA biosynthesis and anthocyanin biosynthesis (Lafferty et al. 2022). More recently, Jin et al. (2022) reported a new MYB, OvMYBPA2, whose expression correlates with PA accumulation in sainfoin (Onobrychis viciifolia); however, this MYB clusters in subgroup A together with TT2s and MYB14, thus Lotus MYBPAs and the sainfoin OvMYBPA2 are not orthologs (Fig. S6). Therefore, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report describing the presence of MYBPA orthologs in legumes. Of the two MYBPA genes present, only MYBPA2 shows a strong correlation with the levels of PAs in any sample set investigated. Its expression positively correlates with that from DFR to downstream genes.

The transcriptomic data also suggest that PA accumulation in Lotus occurs independently from the activation of MYBs that promote anthocyanins in other genera since none of the candidate MYBs, MYB75, MYB90, or PAP1 and PAP2 (named after those of L. japonicus (Yoshida et al. 2010a) are upregulated in L. corniculatus. Moreover, in keeping with the negligible, if any, accumulation of anthocyanins in the two species under investigation, transcripts relative to the anthocyanin activators found in other legumes, such as LAP1-4 in M. truncatula and Tr-RED LEAF, Tr-RED V, Tr-CA1, Tr-RED LEAF DIFFUSE and Tr-BX1 proteins in T. repens (Peel et al. 2009; Albert et al. 2014), were not found. TT8 is likely the only bHLH member that is pivotal in controlling PAs in Lotus spp., as it is the sole DE bHLH gene between the two initial transcriptomes. Its expression correlates with ANS, ANR, LAR1, LAR2 and MATE genes, with PAs' total levels in any sample set investigated. The present study also shows that, differently from other legume species, TTG1 expression correlates neither with PAs nor with the expression of the structural genes and any of the MYB and bHLH regulators. In M. truncatula it has been reported that MtWD40-1, which complements the Arabidopsis ttgg1 mutant, is mainly expressed in the seed coat as well as MtPAR, which, in turn, is sufficient to activate MtWD40-1 transcription in one hybrid yeast assay (Pang et al. 2009; Verdier et al. 2012). The combinations of MtPAR, MtLAP1, MtTT8, and MtWD40-1 also activate the promoter of MtTT8 (Li et al. 2016). The lack of correlation between the expression of TTG1 or PAR with that of TT8 and with the overall levels of PAs coupled with the evidence that LAPs are not among the genes present in our transcriptomes suggests that in the herbage of forage legumes, the presence of TTG1 is dispensable for the correct assemblage of the PA- specific protein complexes. Alternatively, the basal levels of TTG1 might be sufficient to ensure such complexes' formation. Likewise, MBW complexes operating in seeds differ from those operating in vegetative organs. This could partially explain why the ectopic expression of PA activators from M. truncatula and Arabidopsis was insufficient to produce bloat-safe forage legumes.

MYB5 interferes with TT2b-TT8 and MYBPA2-TT8 mediated activation of the ANR and LAR promoters

Xu and collaborators (2014) have remarked that four different MBW complexes in Arabidopsis (TT2-TT8-TTG1, MYB5-TT8-TTG1, TT2-EGL3-TTG1, and TT2-GL3-TTG1) are involved, in a tissue-specific manner, in the transcriptional regulation of LGB genes related to PA biosynthesis. Likewise, the present study reveals that different MBW complexes, with likely partially overlapping functions, might be involved in this regulation in Lotus spp. Several could be the MYB partners of these complexes, namely all those present in subgroup A and MYBPA and MYB5 from groups G and F, respectively. We cannot rule out the formation of even quaternary complexes in which activators and repressors are involved, the last providing feedback regulation to MBW complexes (Albert 2015). Notwithstanding, our data suggest that the complexes in which are present TT2b, MYBPA2 for the MYB component, and TT8 for the bHLH are the ones that more strongly promote PA biosynthesis in Lotus herbage. Additionally, our assays unveil a different commitment among MYBs to interact with TT8. The findings that TT2b and MYBPA2 strongly interact in vitro with TT8 without TTG1 reinforces our contention that TTG1 is either dispensable or its basal levels sufficient to ensure the correct assemblage of the MYBPA2-TT8 and TT2b-TT8 PA complexes. However, this does not hold for MYB5. This protein interacts weakly with TT8 but firmly with Sn. Since in most of the plants studied, the WDR proteins interact with the bHLH TFs only (Grotewold et al. 2000; Dubos et al. 2008; An et al. 2012), and the maize bHLHs do not require the orthologs of TTG1 to form complexes with MYBs, we infer that MYB5 can bind bHLH and promote the transcription of PA specific genes only in an environment where TTG1 is expressed. From the transactivation assays in N. benthamiana leaves, we can also argue that ANR and LAR1 promoters are activated when either TT2b-TT8 or MYBPA2-TT8 proteins are co-expressed. Strikingly, when transfected with TT8, MYB5 activates, although to a far less extent than the other two MYBs, the promoter of ANR but not that of LAR1.

Conversely, by transfecting Arabidopsis protoplasts, Liu and colleagues (2014) have shown that MtMYB5 alone is sufficient to transactivate both MtANR and MtLAR promoters and that the addition of TT8 can enhance this effect but only on ANR promoter. The different outcomes from these studies can stem from the various regulatory elements in the promoters of the two species and/or the different host systems employed. The presence of the endogenous MBW partners could mediate these MYB-bHLH interactions. In this context, the endogenous WDR40 partner expressed in N. benthamiana leaves (Albert et al. 2014; Montefiori et al. 2015) might be responsible for the functional assemblage MYB5-TT8 complex and the following activation of the LcANR promoter.

The finding that MYBPA2 induces the transactivation of both ANR and LAR1 promoters provides functional evidence that this newly identified MYB plays a crucial role in activating both PA branches in Lotus spp. Still better, MYBPA2 amplifies the effects of TT2b on ANR promoter. Notwithstanding, MYB5 compromises the transactivation of activation of ANR and LAR1 by MYBPA2 and TT2b. This outcome is somewhat unexpected since MtMYB5 can synergistically act with another MYB activator (i.e., MtMYB14) to promote ANR and LAR transcription (Liu et al. 2014).

Bottleneck and perspectives for engineering PAs in forage legumes

The approach and the experimental material employed have allowed us to: (a) add new MYB players in the regulation of PA pathway in forage legumes; (b) refine our previous contention, stemming from transgenic approaches, that ANR and LAR1 genes are tightly co-regulated (Paolocci et al. 2007, 2011) and (c) highlight striking differences concerning the regulation of this pathway in Lotus versus other genera of forage legumes. Here, we provide compelling data showing that another player, MYBPA2, adds to the MYBs known to control PA biosynthesis in legumes. Better still, MYBPA2 seems to play a more relevant role than TT2b on the activation of ANR promoter, which, in turn, is more responsive to the transfection with MYB5, MYBPA2, and/or TT2b along with TT8 proteins than LAR1 promoter. It also appears peculiar the role of MYB5: it likely plays a role as a general activator of the flavonoid pathways. It only promotes ANR transcription in Lotus organs/species when either TT2b or MYBPA2 are absent. Conversely, it acts as a passive repressor, likely because it recruits other components on the cis-elements of PA genes when either MYBPA2 or TT2 are present. However, such an effect seems titration-dependent because it is reverted when MYBPA2 and TT2b are expressed. The putative dampening effect of an MYB activator could represent an additional means by which plant cells and organs control the biosynthesis of these pigments. In turn, because of the dampening effect, the pyramiding of multiple TFs might not always be adequate to engineer the biosynthesis of PAs.

Conclusions

The plethora of activator and repressor MYBs found in the two Lotus transcriptomes calls for many MBW complexes underlying the biosynthesis of PAs in forage legumes. These complexes might also differ in composition according to specific developmental windows and growing conditions. This evidence aligns with the complexity of protein interactions, regulatory loop, and gene hierarchy underlying the biosynthesis of PAs described in other genera (Lafferty et al. 2022). Nevertheless, by comparing multiple PA-polymorphic Lotus genotypes grown under different environmental conditions, we show that TT8 for bHLHs and MYBPA2, along with TT2b for MYBs, are the significant determinants of PA biosynthesis in the herbage of Lotus spp. The ectopic expression under different combinations of these TFs, driven by leaf-specific or constitutive promoters to bypass the problem of any hierarchical regulation of these genes, is ongoing in L. tenuis and alfalfa. The goal is to verify whether and to what extent the co-expression of potent regulators of the ANR and LAR branches of the PA pathway will be sufficient to build PAs in species depleted or not naturally committed to synthesizing these compounds in the herbage.

Data availability

The RNA-seq data that support the findings of this study are available in NCBI BioProject, reference number [PRJNA609966], BioSample accessions SAMN14267684 (L. corniculatus) and SAMN14267774 (L. tenuis). The sequences of L.corniculatus and L.tenuis ANR and LAR1 promoters are deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers OM362813-OM362816.

Abbreviations

- ANR:

-

Anthocyanins reductase

- bHLH:

-

Basic helix-loop-helix

- BRE:

-

BHLH-recognizing elements

- LAR:

-

Leucoanthocyanidin reductase

- MBW:

-

MYB-bHLH-WDR complex

- MRE:

-

MYB- recognizing elements

- Pas:

-

Proanthocyanidins

- TFs:

-

Transcription factors

- Y2H:

-

Yeast two-hybrid assay

- WDR:

-

WD-repeat

References

Abrahams S, Lee E, Walker AR et al (2003) The Arabidopsis TDS4 gene encodes leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase (LDOX) and is essential for proanthocyanidin synthesis and vacuole development. Plant J 35:624–636

Aerts RJ, Barry TN, Mcnabb WC (1999) Polyphenols and agriculture: beneficial effects of proanthocyanidins in forages. Agric Ecosyst Environ 75:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8809(99)00062-6

Akagi T, Ikegami A, Tsujimoto T et al (2009) DkMyb4 is a Myb transcription factor involved in proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in persimmon fruit. Plant Physiol 151:2028–2045. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.109.146985

Albert NW (2015) Subspecialization of R2R3-MYB repressors for anthocyanin and Proanthocyanidin regulation in forage legumes. Front Plant Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.01165

Albert NW, Griffiths AG, Cousins GR (2014) Anthocyanin leaf markings are regulated by a family of R2R3-MYB genes in the genus Trifolium. New Phytol 205:882–893

An XH, Tian Y, Chen KQ et al (2012) The apple WD40 protein MdTTG1 interacts with bHLH but not MYB proteins to regulate anthocyanin accumulation. J Plant Physiol 169:710–717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2012.01.015

Andrews S (2010) A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Available online at: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc.

Aoki T, Kawaguchi M, Imaizumi-Anraku H et al (2021) Mutants of Lotus japonicus deficient in flavonoid biosynthesis. J Plant Res 134:341–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10265-021-01258-8

Baudry A, Heim MA, Dubreucq B et al (2004) TT2, TT8, and TTG1 synergistically specify the expression of BANYULS and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 39:366–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02138.x

Bogs J, Jaffé FW, Takos AM et al (2007) The grapevine transcription factor VvMYBPA1 regulates proanthocyanidin synthesis during fruit development. Plant Physiol 143:1347–1361. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.106.093203

Borevitz JO, Xia Y, Blount J et al (2000) Activation tagging identifies a conserved MYB regulator of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Plant Cell 12:2383–2393. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.12.12.2383

Broun P (2005) Transcriptional control of flavonoid biosynthesis: a complex network of conserved regulators involved in multiple aspects of differentiation in Arabidopsis. Curr Opin Plant Biol 8:272–279

Bryant DM, Johnson K, DiTommaso T et al (2017) A tissue-mapped Axolotl De Novo transcriptome enables identification of limb regeneration factors. Cell Rep 18:762–776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.063

Damiani F, Paolocci F, Cluster PD et al (1999) The maize transcription factor Sn alters proanthocyanidin synthesis in transgenic Lotus corniculatus plants. Aust J Plant Physiol 26:159–169

Davies KM, Schwinn KE (2003) Transcriptional regulation of secondary metabolism. Funct Plant Biol 30:913–925

Debeaujon I, Nesi N, Perez P et al (2003) Proanthocyanidin-accumulating cells in Arabidopsis testa: regulation of differentiation and role in seed development. Plant Cell 15:2514–2531. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.014043.1

Di Rienzo JA, Casanoves F, Balzarini MG, et al. (2011) InfoStat versión 2011. Grupo InfoStat, FCA, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina. http://www.infostat.com.ar

Dubos C, Le Gourrierec J, Baudry A et al (2008) MYBL2 is a new regulator of flavonoid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 55:940–953. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03564.x

Dubos C, Stracke R, Grotewold E et al (2010) MYB transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci 15:573–581

Escaray FJ, Rosato M, Pieckenstain FL et al (2012) The proanthocyanidin content as a tool to differentiate between Lotus tenuis and L. corniculatus individuals. Phytochem Lett 5:37–40

Escaray FJ, Passeri V, Babuin MF et al (2014) Lotus tenuis x L. corniculatus interspecific hybridization as a means to breed bloat-safe pastures and gain insight into the genetic control of proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in legumes. BMC Plant Biol 14:14–40. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-14-40

Escaray FJ, Passeri V, Perea-García A et al (2017) The R2R3-MYB TT2b and the bHLH TT8 genes are the major regulators of proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in the leaves of Lotus species. Planta 246:243–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-017-2696-6

Gietz RD (2014) Yeast transformation by the LiAc/SS carrier DNA/PEG method BT - yeast protocols. In: Xiao W (ed) Yeast protoc. Springer, New York, pp 33–44

Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M et al (2011) Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol 29:644–652. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1883

Grotewold E, Sainz MB, Tagliani L et al (2000) Identification of the residues in the Myb domain of maize C1 that specify the interaction with the bHLH cofactor R. Proc Natl Acad Sci 97:13579–13584

Hancock KR, Collette V, Fraser K et al (2012) Expression of the R2R3-MYB transcription factor TaMYB14 from Trifolium arvense activates proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in the legumes Trifolium repens and Medicago sativa. Plant Physiol 159:1204–1220

Hess HD, Tiemann TT, Noto F et al (2006) Strategic use of tannins as means to limit methane emission from ruminant livestock. Int Congr Ser 1293:164–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ics.2006.01.010

Jin Z, Jiang W, Luo Y et al (2022) Analyses on flavonoids and transcriptome reveals key MYB gene for proanthocyanidins regulation in Onobrychis Viciifolia. Front Plant Sci 13:1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.941918

Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K (2016) MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33:1870–1874

Lafferty DJ, Espley RV, Deng CH et al (2022) Hierarchical regulation of MYBPA1 by anthocyanin- and proanthocyanidin-related MYB proteins is conserved in Vaccinium species. J Exp Bot 73:1344–1356. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erab460

Lepiniec L, Debeaujon I, Routaboul J-M et al (2006) Genetics and biochemistry of seed flavonoids. Annu Rev Plant Biol 57:405–430

Li Y-G, Tanner G, Larkin P (1996) The DMACA-HCl protocol and the treshold proanthocyanidin content for bloat safety in forage legumes. J Sci Food Agric 70:89–101

Li P, Dong Q, Ge S et al (2016) Metabolic engineering of proanthocyanidin production by repressing the isoflavone pathways and redirecting anthocyanidin precursor flux in legume. Plant Biotechnol J 14:1604–1618. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.12524

Liu Y, Shi Z, Maximova S et al (2013) Proanthocyanidin synthesis in Theobroma cacao: genes encoding anthocyanidin synthase, anthocyanidin reductase, and leucoanthocyanidin reductase. BMC Plant Biol. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-13-202

Liu C, Jun JH, Dixon RA (2014) MYB5 and MYB14 Play Pivotal Roles in Seed Coat Polymer Biosynthesis in Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiol 165:1424–1439

Lu N, Jun JH, Liu C, Dixon RA (2022) The flexibility of proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in plants. Plant Physiol 190:202–205. https://doi.org/10.1093/plphys/kiac274

Lüscher A, Mueller-Harvey I, Soussana JF et al (2014) Potential of legume-based grassland-livestock systems in Europe: a review. Grass Forage Sci 69:206–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/gfs.12124

Ma D, Constabel CP (2019) MYB repressors as regulators of phenylpropanoid metabolism in plants. Trends Plant Sci 24(3):275–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2018.12.003

Montefiori M, Brendolise C, Dare AP et al (2015) In the Solanaceae, a hierarchy of bHLHs confer distinct target specificity to the anthocyanin regulatory complex. J Exp Bot 66:1427–1436. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/eru494

Mueller-Harvey I, Bee G, Dohme-Meier F et al (2019) Benefits of condensed tannins in forage legumes fed to ruminants: Importance of structure, concentration, and diet composition. Crop Sci 59:861–885. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2017.06.0369

Nei M, Kumar S (2000) Molecular evolution and phylogenetics. Oxford University Press, New York

Nesi N, Jond C, Debeaujon I et al (2001) The Arabidopsis TT2 gene encodes an R2R3 MYB domain protein that acts as a key determinant for proanthocyanidin accumulation in developing seed. Plant Cell 13:2099–2114

Nesi N, Debeaujon I, Jond C et al (2002) The TRANSPARENT TESTA16 locus encodes the ARABIDOPSIS BSISTER MADS domain protein and is required for proper development and pigmentation of the seed coat. Plant Cell 14:2463–2479. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.004127

Notenbaert AMO, Douxchamps S, Villegas DM et al (2021) Tapping Into the environmental co-benefits of improved tropical forages for an agroecological transformation of livestock production systems. Front Sustain Food Syst. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.742842

Pang Y, Wenger JP, Saathoff K et al (2009) A WD40 repeat protein from Medicago truncatula is necessary for tissue-specific anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis but not for trichome development. Plant Physiol 151:1114–1129

Paolocci F, Robbins MP, Madeo L et al (2007) Ectopic expression of a basic helix-loop-helix gene transactivates parallel pathways of proanthocyanidin biosynthesis. structure, expression analysis, and genetic control of leucoanthocyanidin 4-reductase and anthocyanidin reductase genes in Lotus corniculatus. Plant Physiol 143:504–516

Paolocci F, Robbins MP, Passeri V et al (2011) The strawberry transcription factor FaMYB1 inhibits the biosynthesis of proanthocyanidins in Lotus corniculatus leaves. J Exp Bot 62:1189

Passeri V, Martens S, Carvalho E et al (2017) The R2R3MYB VvMYBPA1 from grape reprograms the phenylpropanoid pathway in tobacco flowers. Planta 246:185–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-017-2667-y

Patra AK, Saxena J (2010) A new perspective on the use of plant secondary metabolites to inhibit methanogenesis in the rumen. Phytochemistry 71:1198–1222

Peel GJ, Pang Y, Modolo LV, Dixon RA (2009) The LAP1 MYB transcription factor orchestrates anthocyanidin biosynthesis and glycosylation in Medicago. Plant J 59:136–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03885.x

Pfaffl MW, Horgan GW, Dempfle L (2002) Relative expression software tool (REST) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucl Acids Res 30:1–10

Ravaglia D, Espley RV, Henry-kirk RA et al (2013) Transcriptional regulation of flavonoid biosynthesis in nectarine (Prunus persica) by a set of R2R3 MYB transcription factors. BMC Plant Biol 13:68–68

Robbins MP, Paolocci F, Hughes J-W et al (2003) Sn, a maize bHLH gene, modulates anthocyanin and condensed tannin pathways in Lotus corniculatus. J Exp Bot 54:239–248

Roberts A, Pachter L (2013) Streaming fragment assignment for real-time analysis of sequencing experiments. Nat Methods 10:71–73. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2251

Roldan MB, Cousins G, Muetzel S et al (2022) Condensed tannins in white clover (Trifolium repens) foliar tissues expressing the transcription factor TaMYB14-1 bind to forage protein and reduce ammonia and methane emissions in vitro. Front Plant Sci 12:1–19. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.777354

Saitou N, Nei M (1987) The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4:406–425. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454

Shelton D, Stranne M, Mikkelsen L et al (2012) Transcription factors of Lotus: regulation of isoflavonoid biosynthesis requires coordinated changes in transcription factor activity. Plant Physiol 159:531–547. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.112.194753

Terrier N, Torregrosa L, Ageorges A et al (2008) Ectopic expression of VvMybPA2 promotes proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in grapevine and suggests additional targets in the pathway. Plant Physiol 149:1028–1041. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.108.131862

Tian L, Pang Y, Dixon RA (2008) Biosynthesis and genetic engineering of proanthocyanidins and (iso) flavonoids. Phytochem Rev 7:445–465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11101-007-9076-y

Verdier J, Zhao J, Torres-Jerez I et al (2012) MtPAR MYB transcription factor acts as an on switch for proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in Medicago truncatula. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:1766–1771

Xu W, Dubos C, Lepiniec L (2015) Transcriptional control of flavonoid biosynthesis by MYB–bHLH–WDR complexes. Trends Plant Sci 20:176–185

Xu W, Lepiniec L, Dubos C (2014) New insights toward the transcriptional engineering of proanthocyanidin biosynthesis. Plant Signal Behav 9:e28736. https://doi.org/10.4161/psb.28736

Yoshida K, Iwasaka R, Kaneko T et al (2008) Functional differentiation of Lotus japonicus TT2s, R2R3-MYB transcription factors comprising a multigene family. Plant Cell Physiol 49:157–169. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcn009

Yoshida K, Iwasaka R, Shimada N et al (2010a) Transcriptional control of the dihydroflavonol 4-reductase multigene family in Lotus japonicus. J Plant Res 123:801–805

Yoshida K, Kume N, Nakaya Y et al (2010b) Comparative analysis of the triplicate proathocyanidin regulators in Lotus japonicus. Plant Cell Physiol 51:912–922

Yue M, Jiang L, Zhang N, Zhang L, Liu Y, Lin Y, Zhang Y, Luo Y, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Li M, Wang X, Chen Q, Tang H (2023) Regulation of flavonoids in strawberry fruits by FaMYB5/FaMYB10 dominated MYBbHLH-WD40 ternary complexes. Front Plant Sci 14:1145670. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1145670

Zho H, Lin-Wang K, Wang F, Espley RV, Ren F, Zhao J, Ogutu C, He H, Jiang Q, Allan AC, Han Y (2019) Activator-type R2R3-MYB genes induce a repressor-type R2R3-MYB gene to balance anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin accumulation. New Phytol 221(4):1919–1934. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.15486

Zhou M, Wei L, Sun Z et al (2015) Production and transcriptional regulation of proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in forage legumes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 99:3797–3806

Acknowledgements

This study was partially supported by CNR (Italy)—CONICET (Argentina) 2021-2022 Bilateral Agreement, by the project Pict 2021-2023 from Agencia de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (Argentina), by Margin Up, funded by the European Union's Horizon research and innovation program GA number nº101082089, and by the Italian Agritech National Research Center funded by the European Union Next-Generation EU (Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza (PNRR)– Missione 4 Componente 2, Investitmento 1.4 – D.D. 1032 17/06/2022, CN00000022). In particular, our study represents an original paper related to the Spoke 4 "Multifunctional and resilient agriculture and forestry systems for the mitigation of climate change risks" of the PNRR project. However, views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Agency (REA). Neither the European Union nor the granting authorities can be held responsible.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Consiglio Nazionale Delle Ricerche (CNR) within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FJE, OAR, PD, and FP conceived the research. FJE, MCV, FD and FP conducted molecular and metabolic analyses. FJE carried out bioinformatics analyses. FJE and FP wrote the manuscript with the contribution of all the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Communicated by De-Yu Xie.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Escaray, F.J., Valeri, M.C., Damiani, F. et al. Multiple bHLH/MYB-based protein complexes regulate proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in the herbage of Lotus spp.. Planta 259, 10 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-023-04281-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-023-04281-2