Abstract

Background

Governments in some countries or states/provinces mandate school-based policies intended to improve the health and well-being of primary and secondary students and in some cases the health of school staff. Examples include mandating a minimum time spent per week in programmed physical activity, mandating provision of healthy foods and limiting fat content of school meals, and banning tobacco products or use on school campuses. Although school health researchers have studied whether schools, districts, or states/provinces are meeting requirements, it is unclear to what extent implementation processes and determinants are assessed. The purposes of the present systematic review of quantitative measures of school policy implementation were to (1) identify quantitative school health policy measurement tools developed to measure implementation at the school, district, or state/provincial levels; (2) describe the policy implementation outcomes and determinants assessed and identify the trends in measurement; and (3) assess pragmatic and psychometric properties of identified implementation measures to understand their quality and suitability for broader application.

Methods

Peer-reviewed journal articles published 1995–2020 were included if they (1) had multiple-item quantitative measures of school policy implementation and (2) addressed overall wellness, tobacco, physical activity, nutrition, obesity prevention, or mental health/bullying/social-emotional learning. The final sample comprised 86 measurement tools from 67 peer-review articles. We extracted study characteristics, such as psychometric and pragmatic measure properties, from included articles based on three frameworks: (1) Implementation Outcomes Framework, (2) Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research, and (3) Policy Implementation Determinants Framework.

Results

Most implementation tools were developed to measure overall wellness policies which combined multiple policy topics (n = 35, 40%) and were in survey form (n = 75, 87%). Fidelity was the most frequently prevalent implementation outcome (n = 70, 81%), followed by adoption (n = 32, 81%). The implementation determinants most assessed were readiness for implementation, including resources (n = 43, 50%), leadership (n = 42, 49%), and policy communication (n = 41, 48%). Overall, measures were low-cost and had easy readability. However, lengthy tools and lack of reported validity/reliability data indicate low transferability.

Conclusions

Implementation science can contribute to more complete and rigorous assessment of school health policy implementation processes, which can improve implementation strategies and ultimately the intended health benefits. Several high-quality measures of implementation determinants and implementation outcomes can be applied to school health policy implementation assessment. Dissemination and implementation science researchers can also benefit from measurement experiences of school health researchers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Health policies enacted across multiple levels (e.g., schools, districts, states, countries) are necessary to influence children’s health behaviors [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Children and adolescents from marginalized communities (e.g., low-income, minoritized racial/ethnic groups) are disproportionately at risk for overweight and obesity, and evidence-based policies present an unmatched opportunity to mitigate social determinants of health [7,8,9]. Although evidence supports the impact of successful school-based policy implementation on student health outcomes [1, 6, 10,11,12,13], the disconnect between evidence-based policy and school-based enactment poses challenges for school administrators and teachers [14]. Therefore, researchers and practitioners have called for enhanced policy implementation research which specifically targets the implementation determinants, processes, and outcomes, in order to enhance the rate at which polices are adopted and infused into organizational culture [14,15,16,17].

Specific terms used within dissemination and implementation science (D&I) are implementation determinants, processes, and outcomes [18], which differ from traditional public health research outcomes and offer ways in which researchers can examine how well an innovation is integrated into a particular setting. A clear distinction exists between implementation outcomes and determinants. Implementation outcomes refer to detectable changes in organizational processes and practices as a result of a particular policy or innovation whereas determinants are attributes or characteristics of organizations, innovations, individuals, and the external environment which can be leveraged to increase the likelihood of implementation success [19,20,21,22]. Assessment of determinants offers a pragmatic approach to improving implementation efforts since these attributes are dynamic and ever-changing. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [23, 24] represents a means to study implementation determinants. The CFIR comprises five domains which are empirically based influencers of implementation: innovation characteristics (e.g., intervention cost, feasibility, quality), outer setting (e.g., external networks, policies and incentives), inner setting (e.g., readiness, networks, organizational climate/culture), characteristics of individuals (e.g., self-efficacy, motivation), and implementation process (e.g., planning, engaging, executing). Such determinants can be studied to gage what can influence implementation and help to refine implementation efforts over time.

Implementation processes pertain to the specific procedures or practices taking place within a setting to optimize such diffusion. Examples include enforcement of a policy (i.e., “What obligations are there to implement this?”), evaluation (i.e., “What measures are in place to evaluate implementation success?”), and general barriers and facilitators [24, 25]. Finally, implementation outcomes comprise measurable constructs which demonstrate that an implementation effort has been successful, and offer a broader range than fidelity/compliance which facilitates a deeper understanding of context and successful integration [19, 26, 27]. Such concepts have been applied to study policy implementation, with specific applications to public health policy in recent years [28, 29]. Grounded in the model by Proctor et al., implementation outcomes transcend beyond traditional conceptualizations of the research-to-practice paradigm and include adoption, acceptability, appropriateness, cost, fidelity, feasibility, penetration, and sustainability [19]. Measuring multiple implementation outcomes can enhance understanding of how school policies are diffused into practice, and areas for improvement [19, 29]. For example, a school policy may not be perceived as acceptable or appropriate by its stakeholders, which may explain why fidelity and penetration may be lower than anticipated [19]. To date, however, scant literature exists to understand the measures which exist to capture how school-based policies are implemented, warranting further attention to this setting.

One prominent example of school policy is the Child Nutrition and WIC Re-authorization Act [30], which mandated that all schools participating in the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) within the USA develop a comprehensive wellness policy and a plan for implementation. Another example is the Australian New South Wales (NSW) Sport and Physical Activity Policy, which mandates that all children attending primary and secondary schools should participate in a minimum of 150 min of planned moderate activity across the school week [31]. Findings from prior policy/school health promotion implementation research indicate that lack of funding, training/professional development, and administration support are highlighted as key barriers/negative determinants to implementing health promotion policies and programs [32,33,34,35], whereas provision of such supports are found to be enabling determinants [32]. However, the measurement tools used to assess implementation outcomes and determinants remain poorly understood [36], thus contributing to the sustained research-practice gap. The overuse and over-dependence of “barriers” and “facilitators” to explain implementation of school health promotion and policy research can contribute to misinformation and to the circulation of highly cited issues (i.e., time, funding, support) [33, 35, 37, 38]. As such, minimal solutions are provided for stakeholders to better implement policies and programs. Furthermore, much of the earlier research has been conducted through qualitative evaluation [1, 10, 39,40,41,42], which offers rich information about implementation processes but limits our ability for generalizability and replication.

Although research has examined influential attributes to school health-related policy implementation, matching these attributes to address specific implementation determinants derived through D&I research frameworks [24, 43, 44] will allow for greater use in other school health-related policy topics, and increase the credibility of school-based D&I research and practice. A previous systematic review by Allen et al. [29] investigated quantitative properties of measures of implementation determinants and outcomes pertaining to any type of health policy implemented in clinical or non-clinical settings. The previous review focused on existing measures worded broadly such that they could be applied to study implementation of any health policy type in any setting [29]. Due to such broad focus, however, it was not possible to delve deeper into setting-specific policy implementation measures, limiting the application to school and community-based implementation.

Given the vital role that schools play as a cornerstone of community engagement, understanding how to optimize implementation of health promotion policies can have a significant impact on mitigating health disparities [28]. Advancing this science can provide pragmatic solutions for school researchers and practitioners and optimize the overall impact and sustainability of evidence-based policies. Accordingly, the aims of this systematic review were to (1) identify quantitative school health policy measurement tools developed to measure implementation at the school, district, or state/provincial levels; (2) describe the policy implementation outcomes and determinants assessed and identify the trends in measurement; and (3) assess pragmatic and psychometric properties of identified implementation measures to understand their quality and suitability for broader application.

Methods

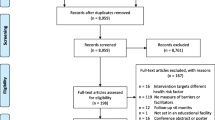

This review of school-based policy implementation measures was conducted with a similar protocol from the aforementioned Allen et al. review of health policy implementation tools [29]. Both reviews followed procedures for conducting a systematic review of implementation measurement tools [45] and adhered to PRISMA reporting guidelines (see Fig. 1 and Supplemental Table S1) [46]. The review was guided by three D&I frameworks: the Implementation Outcomes Framework (IOF) by Proctor and colleagues [19], the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) by Damschroder and colleagues to extract implementation determinants [24], and the Policy Implementation Determinants Framework by Bullock and Davis [25, 47]. Through a combination of constructs from these frameworks, we sought to gain a deeper understanding of the implementation outcomes, determinants, and processes for school health policy implementation which are assessed through measurement tools.

The definitions of public policy and policy implementation were standardized to facilitate reliable screening. Specifically, public policy includes federal/nation, state/province/county, regional unit, or local level legislation or policies mandated by governmental agencies [48, 49]. The implementation of policy conceptualizes the processes by which the mandate is carried out by public or private organizations [49]. For the purpose of this review, the organizations of interest comprised states/provinces, school districts, and primary and secondary pre-university schools as implementing sites.

Searches

We searched six databases in April 2019 and again in August 2020 to ensure inclusion of recent articles in the present review: MEDLINE, PsycInfo, and CINAHL Plus through EBSCO and PAIS, Worldwide Political, and ERIC through ProQuest. We searched terms at four domains: health, public policy, implementation, and measurement; see Supplemental Table S2 for search terms and syntax. Development of the search strings and terms was based on frameworks in D&I and policy research [29].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria comprised English-language peer-reviewed journal articles published from January 1995 through August 2020 and utilized quantitative self-report, observational, and/or archival tools to assess implementation of a government-mandated policy [35]. The review by Allen et al. (covering the period 1995–2019) included empiric studies from any continent on policy implementation in any clinical or non-clinical setting on a broad range of health policy topics. Exclusion criteria can be found in Supplementary Table S3. Specific to school settings, we sought articles that met additional criteria: (1) research must have taken place in/with school settings serving students in primary and secondary (ages 5–18; pre-university) schools; (2) measured implementation of school policies already passed or approved that addressed overall wellness, tobacco, physical activity, nutrition, obesity prevention, or mental health/bullying/social-emotional learning; and (3) policy-specific and setting-specific measures were included in the present review but excluded in the initial broad review (which sought generalizable measures that could be applied across multiple settings and topics). In the earlier review by Allen et al. [29], only six instruments that assessed school health policy implementation were worded broadly enough for inclusion in the published paper. The 2019 database searches identified many school health policy implementation measures, but they were excluded from the earlier review as too setting- and policy-specific; hence, the need for this separate more inclusive review of school health policies. Our review included multi-item measures; articles were excluded if the tool included only one relevant item.

Screening

Two members of the research team used Covidence systematic review software [50] to independently screen all abstracts for inclusion and exclusion. Full texts of all empiric studies of school setting public policy implementation that passed abstract screening in 2019 were rescreened independently in summer 2020 by two coauthors (GMM, PA) for potential inclusion into the present review, with decisions and exclusion reasons coded in Excel. The school setting full-text rescreening was conducted because the Allen review had excluded measures worded specifically for a certain setting or policy topic, whereas such specific measures were included in the present review. The two coauthors also conducted dual independent full-text screening of newly identified 2019–2020 studies that passed abstract screening after the August 2020 updated database searches. The two coauthors met to reach consensus on any inclusion/exclusion disagreements. A third coauthor was consulted if consensus could not be reached. One of the pre-identified exclusion reasons was attributed to each excluded article (for more information see PRISMA chart; Fig. 1).

Extraction

A comprehensive extraction procedure was implemented in which coauthor (GM, PA, CWB) pairs conducted dual non-independent extraction. A primary reviewer entered relevant information into the extraction database and the secondary reviewer checked data entry for accuracy and completeness. The primary and secondary reviewers then met to reach consensus on any extraction discrepancies; thus final agreement was 100%. Information extracted on the measurement properties included (1) type of measurement tool (i.e., survey, archival, observation), (2) implementation setting (i.e., elementary/primary, middle, high/secondary school, combination of two or more levels), (3) school policy topic (i.e., wellness [two or more health topics], physical activity, nutrition, mental health, tobacco, sun safety), and (4) level of educational entity directing implementation of the governmental mandate (i.e., school, district, state/province, national). Given the broad range of policy topics, we felt it useful to list “wellness policy” as a topic for measures where two or more topics were included in the measurement tool (e.g., physical activity, mental health, nutrition) to avoid over-categorization of measures. Following the three chosen D&I frameworks, all implementation outcomes from the Proctor framework were extracted from measures, followed by selected CFIR constructs which were used in the previous review article and found to be pertinent to policy implementation, and the actor relations/networks and actor context domains from the Bullock and Davis framework. Finally, following the procedures outlined by Lewis and colleagues regarding the Psychometric and Pragmatic Evidence Rating Scale (PAPERS) [45, 51,52,53,54,55], pragmatic (i.e., brevity, cost, readability, training, interpretation) and psychometric (i.e., internal consistency, validity, norms) properties were extracted from each measure to ascertain the quality of each tool. These scoring classifications assign scores from − 1 to 4 based on the degree to which the measures meet each criterion; higher scores on each construct reflect higher quality of the measurement tool (Supplemental Tables S4, S5).

Data synthesis

Upon achieving consensus on all measures, descriptive analyses were run to gather frequency of items in each school health policy topic. A subset of tools was widely used and/or based on national samples: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention School Health Policies and Practices Study (school, district, state) [56], the Wellness School Assessment Tool [57], the Maryland Wellness Policies and Practices Project surveys (school and district level) [58], and the Health Enhancing Physical Activity Europe policy audit [59]. We term these “large-scale” tools. Other less frequently reported measures with smaller sample sizes were called “unique tools.” Where appropriate, these measures were analyzed and presented separately when reporting characteristics, given the distinctive differences in methodology and utilization.

Results

Aim 1: Elucidate measurement tools used for school health policy implementation

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flowchart which outlines the steps taken from identifying records through database searching to the studies included in the final review. There were 67 studies included in this review; from these 86 measures were extracted for tool characteristics. From the broad review by Allen et al., six measures from seven studies were also included in in the present review. Of the measures, the vast majority were developed in the USA (n = 60; 69%), followed by Canada (n = 10; 11.6%), European countries (n = 6; 6.9%), and Australia (n = 5; 5.8%). Finally, 2 were developed in India, and 1 each was developed in Indonesia, Mexico, and Taiwan. The 6 studies conducted in Europe were from Denmark (1), the Netherlands (1), Spain (1), or were conducted in multiple countries (3). Table 1 shows the breakdown of tools by school health policy topic and type of tool (i.e., survey, observation, archival). The majority of tools were surveys (n = 75; 87.2%); the most common topic was general wellness policy (i.e., more than two health policy areas; n = 35, 40.6%), followed by nutrition (n = 21; 24.4%) and physical activity (n = 11; 12.7%). Roughly half (n = 42; 49%) of the tool items were generated by experts and 29 measures (33.7%) were piloted with a representative sample. In the included studies, authors reported reliability/validity testing data on pilot testing for 15 measures (17.4%). Of the measures we extracted, psychometric data were available for 28 tools (32.5%).

Aim 2: Investigate implementation determinants and outcomes assessed in the measurement tools

Table 2 displays the implementation outcomes, processes, and determinants extracted for the overall sample and then shown separately for large-scale tools and unique tools. The most common implementation outcomes assessed were fidelity (n = 70; 81.4%), adoption (n = 32; 37.2%), and acceptability (n = 18; 20.9%). The most prevalent implementation determinants in the sample were actor relations/networks (n = 45; 52.3%), followed by readiness for implementation:non-training resources (n = 43; 50.0%) and leadership for implementation (n = 42; 48.8%). Figure 2 illustrates the most 10 commonly measured constructs for the whole sample. Tools varied in their assessment of fidelity, ranging from asking respondents to report their implementation on a Likert scale, to asking about implementation of multiple “best practices” and reporting frequency of utilization/execution. Adoption typically manifested through asking respondents about their intentions to implement a policy or practice, or about planning activity which has occurred in order for implementation to be successful.

For large-scale tools, the most commonly measured determinants were the CFIR readiness for implementation- leadership construct and actor relationships/networks (both n = 22; 95.7%), and the most commonly measured outcome was fidelity from the Proctor model (n = 21; 91.3%). Compared to the whole sample, some constructs which were prevalent in large-scale tools only were the outcome of penetration and the innovation participants determinant from the CFIR-implementation process construct (both n = 8; 34.7%). Among unique tools, fidelity was also the most commonly measured outcome (n = 49; 77.8%) with readiness for implementation-non-training resources (n = 28; 44.4%) as the most common determinant. In terms of least measured constructs, target population characteristics affecting implementation (n = 1) and structure of organization from the CFIR inner setting domain (n = 2) were least measured in the entire sample (see Table 2 for all constructs).

Aim 3: Evaluate the pragmatic and psychometric properties of measurement tools

The PAPERS pragmatic scores are shown in Fig. 3 and show separate median scores for the large-scale and unique tools. In terms of brevity, large-scale tools were scored lower as they had a greater number of items (average = 150) compared to unique tools (average = 73). Almost all tools were free or available at very minimal cost to the public (i.e., not required to pay for article and tool if not subscribed to journal), although our team needed to request original items from the corresponding authors for a large proportion of the sample. Large-scale tools scored higher on training for tool administration as most required no/minimal training, compared to unique tools which were often described more ambiguously. However, the unique tools were shorter, provided easier interpretation guidelines, and had lower grade-level reading scores than the larger-scale tools.

Pragmatic PAPERS scores, by large-scale and unique tools. PAPERS, Psychometric and Pragmatic Evidence Rating Scale [55]

Psychometric PAPERS scores were low (0 median) across all components, with large-scale tools generally demonstrating higher quality according to internal consistency and validity (0.66 versus 0.56 mean PAPERS score, out of a possible lowest score of − 1 to a possible highest score of 4). Overall, internal consistency α coefficient scores ranged from 0.40 to 0.98 across the studies. In addition, the sample sizes (2 versus 0.78 mean PAPERS score) used to deduce findings were larger for large-scale studies, ranging from 19 [60] to 6504 schools [61]; samples ranged in between these numbers and were at the student, teacher, school, district, and state/provincial level (see Supplemental Tables S4, S5 for scoring criteria). Very few tool development articles/documents provided concurrent and structural validity information; none of the large-scale tool studies provided such information. Overall, psychometric quality of tools was unknown or low. These results highlight areas for improvement in future tool development and reporting.

Characteristics and PAPERS scores for each tool are provided in Supplementary Table S6. Despite low scores overall, some tools were well-developed and validated according to best practices. One example is the Maryland Wellness Policies and Practices Project (MWPPP) district and school surveys [58], which each received a score of at least 10 (15 for district, 10 for school) for pragmatic and 12 for psychometric properties (Supplementary Table S6). This tool measures overall wellness policy implementation at the school and district levels, assessing multiple implementation outcomes (i.e., adoption, feasibility, fidelity) and determinants (i.e., implementation climate-goals and feedback; readiness-communication of policy, policy awareness/knowledge, leadership, non-training resources, training; actor relationships, visibility of policy role, evaluation, collaboration, innovation participants). This tool may be easily adapted for use within other states and countries depending on policy characteristics. Supplemental Table S6 displays PAPERS scores and tool characteristics for all 86 measured included in the review.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to obtain a comprehensive understanding of quantitative implementation measurement tools for school health policy following a systematic review protocol. Findings revealed a large number of tools which covered a wide range of policy topics and implementation settings, with general wellness policy (i.e., two or more health topics) as the most commonly measured area of health promotion. Most of the tools assessing wellness policies more broadly were from the USA, which aligns with federal mandates for schools to develop and implement comprehensive wellness programming [30]. Further, it should be noted that almost all tools were gathered from high-income countries, which draws attention to low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) and the potential for both policy development and implementation evaluation as a means to support ongoing health needs in such populations. Findings from systematic review research highlight a lack of policy/intervention initiatives from LMIC which sought to address child health promotion in the school setting [62]. Accordingly, further work is warranted to examine the fit of existing tools for school contexts in LMIC and to determine how tools from high-income countries may be adapted for use in LMIC to optimize efficiency and sharing of resources.

Implementation outcomes

Integration of three prominent implementation frameworks in this study facilitated a rich understanding of implementation processes, outcomes, and determinants in a policy context. The finding that fidelity was the most commonly assessed implementation outcome aligns with findings of the broader review by Allen et al. [29], and highlights the high dependence on fidelity as an indicator of implementation success. Several tools only measured fidelity and/or adoption as the implementation outcomes, which draws concern for addressing constructs such as feasibility and sustainability, among others. Only 8 measures addressed feasibility, with 7 of those within unique tools; this is somewhat contradictory to the extant literature on school-based programming, as many studies have reported low feasibility for implementing policies and health promoting interventions [38, 63,64,65]. Further, through qualitative and mixed-methods research it has transpired that, despite providing financial and logistical support to schools, districts, and states/provinces, most policies are difficult to sustain in absence of such support [65,66,67]. The finding that only 3 tools measured sustainability is concerning given the emphasis on sustainability/maintenance as a key weakness in implementation science and policy research [19, 68]. Accordingly, it is clear that a greater emphasis on other implementation outcomes and processes would be beneficial in school policy research, given the top-down nature of policy to practice and need to understand how policy and practice can be sustained over time. Measures of implementation outcomes are continuously being developed and tested for validity and reliability, building on earlier work in the education setting [69]. For example, brief measures of acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness were designed to add in a specific evidence-based practice (or policy) as the item referent; these have preliminary evidence for good reliability and validity [70]. Luke and colleagues developed a measure to assess organizational capacity for sustaining public health and other programs that is reliable and has been tested for construct validity [71]. Although strong examples exist in the healthcare literature [51, 70, 71], there is a need for adaptation and modification to enhance application of D&I within school settings.

Overall, there was a lack of attention paid toward addressing health disparities in the school policy literature and sample of articles. Scholars have stressed the importance of grounding implementation research in health equity principles to examine how implementation efforts may mitigate specific disparities in access to interventions and care [28, 72,73,74]. Specifically, the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance (RE-AIM) initially developed by Glasgow et al. [68, 75] was adapted to address issues of equity and sustainability with the goal of advancing the science needed to understand how equity can be considered an independent outcome and embedded within each construct to enhance understanding of implementation context [72]. For example, within a school setting it may be useful to measure the community context and sociodemographic characteristics of the school and surrounding community, as a means to understand how implementation of a policy can also promote opportunities for students to engage in health programming, through leveraging community resources [76, 77]. Further research and development is needed in this area to enhance our understanding of health equity and policy implementation.

Implementation determinants

The finding that readiness for implementation as a general construct was most measured reflects prior research stressing the importance of assessing readiness and organizational capacity for implementation [33, 78,79,80,81,82,83]. Within this broader construct, non-training resources was the most common determinant assessed; provision of financial resources and personnel support have been cited as supportive factors for policy and innovation implementation in school research [12, 84, 85]. Following this, leadership for implementation was very prevalent in the measures, which again reflects extant knowledge that new innovations require a leader to succeed [65, 86, 87]. Finally, the prevalence of items measuring communication of policy demonstrated the importance of engaging stakeholders in policy implementation through enhancing awareness of such initiatives. Such communication is somewhat understudied as a determinant of implementation in school-based literature according to systematic review research [88, 89] but is perhaps one of the most influential determinants of implementation success. School policy research may be further enhanced by studying the relationships between implementation determinants and outcomes to provide clearer evidence between frameworks such as CFIR and the Proctor outcomes framework [19, 24]. Further, rather than developing completely new measurement tools, those previously tested in community and clinical settings may be used as is or adapted for school settings, facilitating transferability through implementation science [36].

Unlike readiness for implementation, there was a lack of measures to assess the inner setting and implementation process domains, with relative priority (inner setting) and evaluation (implementation process) identified as the most common among constructs. Research has demonstrated the importance of studying organizational culture and climate as a determinant of implementation [86], given that teachers’ actions are encompassed by school- and district-level policies and practices [90, 91]. Some innovations have indeed failed despite leadership for implementation (i.e., small group of leaders taking ownership) due to conflicting organizational practices and lack of priority placed on such initiatives [35, 92]. For true diffusion of innovation to occur, institutional buy-in is essential [93, 94]; future measures development should therefore integrate these constructs as a means to better understand what impacts policy implementation and bridge the research-to-practice gap. Recently, some measures have been developed to address organizational climate and context pertaining to school-based interventions [95]. Such work marks an important step to enhancing implementation measurement within schools; further modification and adaptation is needed to address other implementation determinants, outcomes, and processes.

Finally, as previously mentioned, health equity was absent from determinants measured. As with outcome frameworks, determinant frameworks such as the Health Equity Implementation Framework [73] provide ways to assess implementation context and the structural, sociopolitical, and organizational factors which should be studied to understand how and why implementation occurs in a specific setting. This is particularly salient for schools serving historically marginalized communities such as low-income and communities of color, given the lack of educational funding and support often given to these institutions [33, 96,97,98]. These factors could and should be studied as the field of policy implementation research grows over time.

Psychometric and pragmatic properties

Application of the PAPERS rating criteria for pragmatic and psychometric properties revealed areas of strength and need for future improvement [45, 54, 55]. Findings for the pragmatic criteria demonstrated that school policy implementation measures found were generally low-cost and written to a lay audience. However, many tools were long and median scores were driven by large-scale tools such as the SHPPS [56, 99]; a key barrier to conducting research and evaluation with schools is the limited time that stakeholders are able to spend completing surveys and other audit tools, which has implications for data quality and reliability [41, 55, 100, 101]. Although a key need from this study is to adopt pre-existing or develop comprehensive measures which examine implementation outcomes, processes, and determinants, this can lead to lengthy measurement tools which can become arduous to complete and lead to disenfranchisement from stakeholders. Finally, psychometric PAPERS protocols revealed that efforts to ensure quality of tools centered mainly on analyzing internal consistency, with little attention paid to other forms of validity and reliability. This trend is common across other reviews of implementation measures [29, 51] and has implications for broader tool use, specifically when trying to demonstrate implementation efficacy to other populations or policies within school settings. Accordingly, careful tool development should be a focus, and over time it may transpire that some determinants are more influential than others in the policy implementation field, facilitating a streamlined process for subsequent evaluation. Best practices such as field-based pilot testing based on representative samples and developing input from experts are therefore essential in enhancing the pragmatic capabilities of these tools.

Limitations

Although we conducted a rigorous systematic review following previously established protocols, there are several limitations to note. First, we only extracted tools which were available through online library searches and contacting authors directly where we could not find measures online. We used several approaches to retrieve all tools for extraction, but some tools were unavailable online or from the study authors. We were unable to analyze tools for which we could not access original items. We did not conduct citation searching to find all empiric uses of each included measure, so we may not have captured all adaptations of each measure. Tools from the grey literature were also not included in this review; although we searched for manuals and tools available online, it was required they were cited in a peer-reviewed article first. Second, we did not explicitly screen for health equity constructs, but based on our review of included tools there was not much to be gleaned in terms of health equity and policy. Several implementation science frameworks integrate health equity and these help to provide guidance for future measurement development [72, 73, 102,103,104,105,106]. Finally, although we took a comprehensive policy approach, some policy topics were excluded (i.e., not directly related to health/wellness topics), and in excluding these we may have overlooked other pertinent measurement tools.

Conclusions

What gets measured gets achieved [107] — our review suggests that more comprehensive measurement tools are needed for school policy research that come from or could potentially be transferred to other settings (i.e., community, clinical). Enhancing the quality of policy D&I research through high-quality pragmatic measures will mark a key step in bridging the policy to practice gap [52, 75, 108]. Future assessment of implementation of policies intended to improve school staff well-being is also needed. Furthermore, given the lack of focus on addressing health equity, there is now an opportunity to apply or develop tools which can help distinguish practices that address health disparities. The WIC Child Nutrition Re-Authorization act [30] and USDA Healthy Hunger Free Kids Act (HHFKA) [109] are examples of policies which inherently are aimed at reducing health inequality given the focus on NSLP integration, but we know little about how their implementation may influence social determinants of health. Thus, more explicitly addressing health equity is a priority for future research and practice in health policy, in order to elicit a meaningful impact on population health.

Availability of data and materials

A compendium of identified measures is publicly available for dissemination at https://www.health-policy-measures.org/. A link is provided on the website of the Prevention Research Center, Brown School, Washington University, in St. Louis, at https://prcstl.wustl.edu/. The authors invite interested organizations to provide a link to the compendium on their own websites. Citations and abstracts of excluded policy-specific measures are available on request.

References

Abbott R, Macdonald D, Hay P, McCuaig L. "Just add facilitators and stir": stimulating policy uptake in schools. Educ Manage Admin Leadership. 2011;39(5):603–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143211408452.

Chriqui JF, Chaloupka FJ. Transparency and oversight in local wellness policies. J Sch Health. 2011;81(2):114–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00568.x.

Fagen MC, Asada Y, Welch S, Dombrowski R, Gilmet K, Welter C, et al. Policy, systems, and environmentally oriented school-based obesity prevention: opportunities and challenges. J Prev Intervent Commun. 2014;42(2):95–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/10852352.2014.881175.

Schwartz MB, Henderson KE, Falbe J, Novak SA, Wharton CM, Long MW, et al. Strength and comprehensiveness of district school wellness policies predict policy implementation at the school level. J Sch Health. 2012;82(6):262–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2012.00696.x.

Story M, Nanney MS, Schwartz MB. Schools and obesity prevention: creating school environments and policies to promote healthy eating and physical activity. Milbank Q. 2009;87(1):71–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00548.x.

Turner L, Leider J, Piekarz-Porter E, Schwartz MB, Merlo C, Brener N, et al. State laws are associated with school lunch duration and promotion practices. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118(3):455–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2017.08.116.

Trent M, Dooley DG, Dougé J. The impact of racism on child and adolescent health. Pediatrics. 2019;144(2):e20191765. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-1765.

Odoms-Young A, Bruce MA. Examining the impact of structural racism on food insecurity: implications for addressing racial/ethnic disparities. Fam Community Health. 2018;41 Suppl 2 Suppl, Food Insecurity and Obesity(Suppl 2 FOOD INSECURITY AND OBESITY):S3–6.

Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, Pieterse A, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138511. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138511.

Allison KR, Vu-Nguyen K, Ng B, Schoueri-Mychasiw N, Dwyer JJM, Manson H, et al. Evaluation of daily physical activity (DPA) policy implementation in Ontario: surveys of elementary school administrators and teachers. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1–16.

Baker EA, Elliott M, Barnidge E, Estlund A, Brownson RC, Milne A, et al. Implementing and evaluating environmental and policy interventions for promoting physical activity in rural schools. J School Health. 2017;87(7):538.

Cradock AL, Barrett JL, Carter J, McHugh A, Sproul J, Russo ET, et al. Impact of the Boston active school day policy to promote physical activity among children. Am J Health Promot. 2014;28:54–64.

Melard N, Grard A, Robert PO, Kuipers MAG, Schreuders M, Rimpela AH, et al. School tobacco policies and adolescent smoking in six European cities in 2013 and 2016: a school-level longitudinal study. Prev Med. 2020;138:106142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106142.

Turgeon B. A district wellness policy: the gap between policy and practice. J Educ Learn. 2013;2(3):26–38.

Brownson RC, Eyler AA, Harris JK, Moore JB, Tabak RG. Getting the word out. J Public Health Manage Pract. 2018;24(2):102–11. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000000673.

Harvey SP, Markenson D, Gibson CA. Assessing school wellness policies and identifying priorities for action: results of a bi-state evaluation. J School Health. 2018;88(5):359–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12619.

Vandevijvere S, Mackay S, Swinburn B. Measuring and stimulating progress on implementing widely recommended food environment policies: the New Zealand case study. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16:1-N.PAG.

Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, editors. Dissemination and implementation research in health: translating science to practice, second edition. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018.

Proctor EK, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Admin Pol Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7.

Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, Mittman B. Implementation research in mental health services: an emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Admin Pol Ment Health. 2009;36(1):24–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4.

Purtle JD, EA; Brownson, RC. Policy Dissemination Research. In: Brownson R, ; Colditz, GA; Proctor, EK, editor. Dissemination and implementation research in health: translating science to practice, second edition. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018.

Tabak RG, Padek MM, Kerner JF, Stange KC, Proctor EK, Dobbins MJ, et al. Dissemination and implementation science training needs: insights from practitioners and researchers. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(3S3):S322–S9.

Damschroder LJ, Lowery JC. Evaluation of a large-scale weight management program using the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR). Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):51. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-51.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50.

Bullock HL, Lavis JN. Understanding the supports needed for policy implementation: a comparative analysis of the placement of intermediaries across three mental health systems. Health Res Policy Syst. 2019;17(1):82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-019-0479-1.

Lewis CC, Proctor, EK, Brownson RC. Measurement issues in dissemination and implementation research. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, editors. Disssemination and implementation research in health: translating science to practice, second edition. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018.

Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK. Future issues in dissemination and implementation research. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, editor. Dissemination and implementation research in health: translating science to practice. Second edition ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018.

Emmons KM, Chambers DA. Policy implementation science - an unexplored strategy to address social determinants of health. Ethn Dis. 2021;31(1):133–8. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.31.1.133.

Allen P, Pilar M, Walsh-Bailey C, Hooley C, Mazzucca S, Lewis CC, et al. Quantitative measures of health policy implementation determinants and outcomes: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-01007-w.

Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004, 42 U.S.C. 1751 §204 (2004).

New South Wales Department of Education. Sport and physical activity policy. 2020. [Available from: https://policies.education.nsw.gov.au/policy-library/policies/sport-and-physical-activity-policy. Accessed 20 Jan 2021.

Alexander KE, Brijnath B, Mazza D. Barriers and enablers to delivery of the healthy kids check: an analysis informed by the theoretical domains framework and COM-B model. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):60.

Blaine RE, Franckle RL, Ganter C, Falbe J, Giles C, Criss S, et al. Using school staff members to implement a childhood obesity prevention intervention in low-income school districts: the massachusetts childhood obesity research demonstration (MACORD Project), 2012-2014. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;12(14):E03. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd14.160381.

Bozsik F, Berman M, Shook R, Summar S, DeWit E, Carlson J. Implementation contextual factors related to youth advocacy for healthy eating and active living. Transl Behav Med. 2018;8(5):696–705. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibx006.

Slawson D, Southerland J, Lowe E, Dalton W, Pfortmiller D, Schetzina K. Go slow whoa meal patterns: cafeteria staff and teacher perceptions of effectiveness in winning with wellness schools. J Sch Health. 2013;83(7):485–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12056.

Martinez RG, Lewis CC, Weiner BJ. Instrumentation issues in implementation science. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):118. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-014-0118-8.

Agron P, Berends V, Ellis K, Gonzalez M. School wellness policies: perceptions, barriers, and needs among school leaders and wellness advocates. J Sch Health. 2010;80(11):527–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00538.x.

McLoughlin GM, Graber KC, Woods AM, Templin T, Metzler M, Khan NA. The status of physical education within a nationally recognized school health and wellness program. J Teach Phys Educ. 2020;39(2):274–83. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2019-0052.

Asada Y, Ziemann M, Zatz LY, Chriqui J. Successes and challenges in school meal reform: qualitative insights from food service directors. J Sch Health. 2017;87(8):608–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12534.

Evenson KR, Ballard K, Lee G, Ammerman A. Implementation of a school-based state policy to increase physical activity. J Sch Health. 2009;79(5):231–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00403.x.

Phillips MM, Raczynski JM, West DS, Pulley L, Bursac Z, Leviton LC. The evaluation of Arkansas Act 1220 of 2003 to reduce childhood obesity: conceptualization, design, and special challenges. Am J Community Psychol. 2013;51(1-2):289–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-012-9538-2.

Weatherson KA, McKay R, Gainforth HL, Jung ME. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of a school-based physical activity policy in Canada: application of the theoretical domains framework. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):835. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4846-y.

Kirk MA, Kelley C, Yankey N, Birken SA, Abadie B, Damschroder L. A systematic review of the use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):72.

Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Fernández ME, Abadie B, Damschroder LJ. Choosing implementation strategies to address contextual barriers: diversity in recommendations and future directions. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0892-4.

Lewis CC, Mettert KD, Dorsey CN, Martinez RG, Weiner BJ, Nolen E, et al. An updated protocol for a systematic review of implementation-related measures. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0728-3.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Bullock HL. Understanding the implementation of evidence-informed policies and practices from a policy perspective: a critical interpretive synthesis in: how do systems achieve their goals? The role of implementation in mental health systems improvement [Dissertation]. Hamilton, Ontario: McMaster University; 2019.

Eyler AA, Chriqui JF, Moreland-Russell S, Brownson RC, editors. Prevention, policy, and public health, first edition. New York: Oxford University Press; 2016. https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780190224653.001.0001.

Natesan SD, Marathe RR. Literature review of public policy implementation. Int J Public Policy. 2015;11(4):219–38. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPP.2015.070550.

Covidence. Cochrane Community. https://community.cochrane.org/help/tools-and-software/covidence. Accessed 30 July 2020.

Lewis CC, Fischer S, Weiner BJ, Stanick C, Kim M, Martinez RG. Outcomes for implementation science: an enhanced systematic review of instruments using evidence-based rating criteria. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):155. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0342-x.

Glasgow RE, Riley WT. Pragmatic measures: what they are and why we need them. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(2):237–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.03.010.

Henrikson NB, Blasi PR, Dorsey CN, Mettert KD, Nguyen MB, Walsh-Bailey C, et al. Psychometric and pragmatic properties of social risk screening tools: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(6S1):S13–24.

Powell BJ, Stanick CF, Halko HM, Dorsey CN, Weiner BJ, Barwick MA, et al. Toward criteria for pragmatic measurement in implementation research and practice: a stakeholder-driven approach using concept mapping. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):118. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0649-x.

Stanick CF, Halko HM, Nolen EA, Powell BJ, Dorsey CN, Mettert KD, et al. Pragmatic measures for implementation research: development of the Psychometric and Pragmatic Evidence Rating Scale (PAPERS). Transl Behav Med. 2021;11(1):11-20. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibz164.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. School Health Policies and Practices Study 2012. Atlanta: US Department of Health andHuman Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/shpps/index.htm. Accessed 1 Aug 2020.

Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity WellSAT: Wellness School Assessment Tool. Available online:http://www.wellsat.org/default.aspx. Accessed 7 Aug 2020.

Hager ER, Rubio DS, Eidel GS, Penniston ES, Lopes M, Saksvig BI, et al. Implementation of local wellness policies in schools: role of school systems, school health councils, and health disparities. J Sch Health. 2016;86(10):742–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12430.

Bull FC, Milton K, Kahlmeier S. National policy on physical activity: the development of a policy audit tool. J Phys Act Health. 2014;11(2):233–40. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2012-0083.

Bassi S, Gupta VK, Park M, Nazar GP, Rawal T, Bhaumik S, et al. School policies, built environment and practices for non-communicable disease (NCD) prevention and control in schools of Delhi, India. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0215365. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215365.

Kehm R, Davey CS, Nanney MS. The role of family and community involvement in the development and implementation of school nutrition and physical activity policy. J Sch Health. 2015;85(2):90–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12231.

Xu T, Tomokawa S, Gregorio ER Jr, Mannava P, Nagai M, Sobel H. School-based interventions to promote adolescent health: a systematic review in low- and middle-income countries of WHO Western Pacific Region. PLoS One. 2020;15(3):e0230046.

Au LE, Ritchie LD, Gurzo K, Nhan LA, Woodward-Lopez G, Kao J, et al. Post-healthy, hunger-free kids act adherence to select school nutrition standards by region and poverty level: the Healthy Communities study. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2020;52(3):249–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2019.10.016.

Gillies C, Alexander Research C, Farmer A, Maximova K, Willows ND. Alexander First Nations parents' perceptions of a school nutrition policy. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2020;81(2):66–71. https://doi.org/10.3148/cjdpr-2019-026.

McLoughlin GM, Candal P, Vazou S, Lee JA, Dzewaltowski DA, Rosenkranz RR, et al. Evaluating the implementation of the SWITCH® school wellness intervention and capacity-building process through multiple methods. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17(1):162. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01070-y.

Rozema AD, Mathijssen JJP, Jansen MWJ, van Oers JAM. Sustainability of outdoor school ground smoking bans at secondary schools: a mixed-method study. Eur J Pub Health. 2018;28(1):43–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckx099.

Wolfenden L, Reilly K, Kingsland M, Grady A, Williams CM, Nathan N, et al. Identifying opportunities to develop the science of implementation for community-based non-communicable disease prevention: A review of implementation trials. Prev Med. 2019;118:279–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.11.014.

Glasgow RE, Dzewaltowski DA, Estabrooks PA, Gaglio BA, King D, Klesges L. RE-AIM; 2010.

Martens BK, Witt JC, Elliott SN, Darveaux DX. Teacher judgments concerning the acceptability of school-based interventions. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 1985;16(2):191–8. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.16.2.191.

Weiner BJ, Lewis CC, Stanick C, Powell BJ, Dorsey CN, Clary AS, et al. Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0635-3.

Luke DA, Calhoun A, Robichaux CB, Elliott MB, Moreland-Russell S. The Program Sustainability Assessment Tool: a new instrument for public health programs. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:130184. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd11.130184.

Shelton RC, Chambers DA, Glasgow RE. An extension of RE-AIM to enhance sustainability: addressing dynamic context and promoting health equity over time. Front Public Health. 2020;8(134). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00134.

Woodward EN, Matthieu MM, Uchendu US, Rogal S, Kirchner JE. The health equity implementation framework: proposal and preliminary study of hepatitis C virus treatment. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):26.

Brownson RC, Kumanyika SK, Kreuter MW, Haire-Joshu D. Implementation science should give higher priority to health equity. Implement Sci. 2021;16(1):28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-021-01097-0.

Glasgow RE, Estabrooks PE. Pragmatic applications of RE-AIM for health care initiatives in community and clinical settings. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:E02.

Mazzucca S, Arredondo EM, Hoelscher DM, Haire-Joshu D, Tabak RG, Kumanyika SK, et al. Expanding implementation research to prevent chronic diseases in community settings. Annu Rev Public Health. 2021;42:135-58. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102547.

Kumanyika SK. A framework for increasing equity impact in obesity prevention. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(10):1350–7. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305221.

Scaccia JP, Cook BS, Lamont A, Wandersman A, Castellow J, Katz J, et al. A practical implementation science heuristic for organizational readiness: R = MC. J Commun Psychol. 2015;43(4):484.

Cheung K, Lesesne CA, Rasberry CN, Kroupa E, Fisher D, Robin L, et al. Barriers and facilitators to sustaining school health teams in coordinated school health programs. Health Promot Pract. 2017;18(3):418–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839916638817.

Holt DT, Helfrich CD, Hall CG, Weiner BJ. Are you ready? How health professionals can comprehensively conceptualize readiness for change. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(SUPPL. 1):50–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-1112-8.

Lee JA, Welk GJ, Vazou S, Ellingson LD, Lanningham-Foster L, Dixon P. Development and application of tools to assess elementary school wellness environments and readiness for wellness change (doctoral dissertation); 2018.

Octaria Y, Apriningsih A, Dwiriani CM, Februhartanty J. School readiness to adopt a school-based adolescent nutrition intervention in urban Indonesia. Public Health Nutr. 2020:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020001299.

Weiner BJ. A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):67.

Nathan N, Wiggers J, Bauman AE, Rissel C, Searles A, Reeves P, et al. A cluster randomised controlled trial of an intervention to increase the implementation of school physical activity policies and guidelines: study protocol for the physically active children in education (PACE) study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):170. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6492-z.

Nathan NK, Sutherland RL, Hope K, McCarthy NJ, Pettett M, Elton B, Jackson R, Trost SG, Lecathelinais C, Reilly K, Wiggers JH, Hall A, Gillham K,Herrmann V, Wolfenden L. J Phys Act Health. 2020;17(10):1009-18. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2019-0595.

Fernandez ME, Walker TJ, Weiner BJ, Calo WA, Liang S, Risendal B, et al. Developing measures to assess constructs from the inner setting domain of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0736-7.

McIsaac JLD, Read K, Veugelers PJ, Kirk SFL. Culture matters: a case of school health promotion in Canada. Health Promot Int. 2017;32(2):207-17. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dat055.

McKay H, Naylor P-J, Lau E, Gray SM, Wolfenden L, Milat A, et al. Implementation and scale-up of physical activity and behavioural nutrition interventions: an evaluation roadmap. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019;16(1):102.

Naylor P-J, Nettlefold L, Race D, Hoy C, Ashe MC, Wharf Higgins J, et al. Implementation of school based physical activity interventions: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2015;72:95–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.12.034.

Langille J-LD, Rodgers WM. Exploring the influence of a social ecological model on school-based physical activity. Health Educ Behav. 2010;37(6):879–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198110367877.

Suarez-Balcazar Y, Redmond L, Kouba J, Hellwig M, Davis R, Martinez L, et al. Introducing systems change in the schools: the case of school luncheons and vending machines. Am J Community Psychol. 2007;39(3):335–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-007-9102-7.

McIsaac JD, Penney TL, Mâsse L, Kirk SFL. The Association between Perceived Adequacy and Capacity for School Food Policy Implementation withFood Availability and Policy Adherence in Nova Scotia, Canada. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(11):1974. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16111974.

Dearing JW, Cox JG. Diffusion of innovations theory, principles, and practice. Health Aff. 2018;37(2):183.

Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations, Fifth Edition 2003; 2019.

Lyon AR, Cook CR, Brown EC, Locke J, Davis C, Ehrhart M, et al. Assessing organizational implementation context in the education sector: confirmatory factor analysis of measures of implementation leadership, climate, and citizenship. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0705-6.

McLoughlin GM, McCarthy JA, McGuirt JT, Singleton CR, Dunn CG, Gadhoke P. Addressing Food Insecurity through a Health Equity Lens: a Case Study of Large Urban School Districts during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Urban Health. 2020;97(6):759-75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-020-00476-0.

Bartfeld JS, Berger L, Men F. Universal access to free school meals through the community eligibility provision is associated with better attendance for low-income elementary school students in Wisconsin. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2020;120(2):210–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2019.07.022.

Schuler BR, Saksvig BI, Nduka J, Beckerman S, Jaspers L, Black MM, et al. Barriers and enablers to the implementation of school wellness policies: an economic perspective. Health Promot Pract. 2018;19(6):873–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839917752109.

Prevention CfDCa. SHPPS 2006: School Health Policies and Programs Study--state-level School Health Policies and Practices. A state-by-state summary from the school health policies and programs study 2006. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007.

Cargo M, Mercer SL. The value and challenges of participatory research: strengthening its practice. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29(1):325–50. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.091307.083824.

Harrington KF, Binkley D, Reynolds KD, Duvall RC, Copeland JR, Franklin F, et al. Recruitment issues in school-based research: lessons learned from the High 5 Alabama project. J Sch Health. 1997;67(10):415–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.1997.tb01287.x.

Eslava-Schmalbach J, Garzón-Orjuela N, Elias V, Reveiz L, Tran N, Langlois EV. Conceptual framework of equity-focused implementation research for health programs (EquIR). Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):80. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-0984-4.

Aby MJ. Race and equity in statewide implementation programs: an application of the policy ecology of implementation framework. Admin Pol Ment Health. 2020;47(6):946–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-020-01033-2.

Dover DC, Belon AP. The health equity measurement framework: a comprehensive model to measure social inequities in health. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-0935-0.

Yousefi Nooraie R, Kwan BM, Cohn E, AuYoung M, Clarke Roberts M, Adsul P, et al. Advancing health equity through CTSA programs: opportunities for interaction between health equity, dissemination and implementation, and translational science. J Clin Transl Sci. 2020;4(3):168–75. https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2020.10.

Nápoles AM, Stewart AL. Transcreation: an implementation science framework for community-engaged behavioral interventions to reduce health disparities. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):710.

Thacker SB. Public health surveillance and the prevention of injuries in sports: what gets measured gets done. J Athl Train. 2007;42(2):171–2.

Glasgow RE. What does it mean to be pragmatic? Pragmatic methods, measures, and models to facilitate research translation. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(3):257–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198113486805.

Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010, 42 U.S.C. 1779 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the administrative support of Mary Adams, Linda Dix, and Cheryl Valko at the Prevention Research Center, Brown School, Washington University in St. Louis. We also wish to thank Mia Vogel for her support in early refinements to data extraction methods. The Washington University library system provided assistance in developing and testing search syntax in this systematic review and facilitated inter-library loans.

Funding

Funding support for this project is from the National Cancer Institute P50CA244431, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention U48DP006395, and the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital, with support from the Washington University in St. Louis Institute of Clinical and Translational Science Pilot Program, NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) grant UL1 TR002345.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Eligibility criteria: PA, RCB, CWB, and GMM. Search strings and terms: PA and CWB. Abstract screening: PA and CWB. Full-text screening: GMM and PA. Data extraction: GMM, CWB, and PA. Data aggregation: GMM and PA. Writing: GMM, CWB, PA, and RCB. Editing: GMM, CWB, PA, and RCB. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

GMM and RCB are with the Implementation Science Center for Cancer Control and Prevention Research Center, Brown School, Washington University in St. Louis, and the Division of Public Health Sciences (Department of Surgery), Washington University School of Medicine, Washington University in St. Louis. CWB and PA are with the Prevention Research Center, Brown School, Washington University in St. Louis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplemental Table S1

. PRISMA 2009 checklist. Supplemental Table S2. Electronic database search terms. Supplemental Table S3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria. Supplemental Table S4. Psychometric and Pragmatic Evidence Rating Scale (PAPERS) Pragmatic rating scales. Supplemental Table S5. Psychometric and Pragmatic Evidence Rating Scale (PAPERS) Psychometric rating scales. Supplemental Table S6. Measures Information and Psychometric and Pragmatic Evidence Rating Scale (PAPERS) Scores.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

McLoughlin, G.M., Allen, P., Walsh-Bailey, C. et al. A systematic review of school health policy measurement tools: implementation determinants and outcomes. Implement Sci Commun 2, 67 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-021-00169-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-021-00169-y