Abstract

Background

Cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYPs) are exciting biocatalysts that catalyzes diverse regio- and stereoselective reactions of a broad range of substrates. The cytochrome P450 genes (CYPomes) of a chronically polluted soil (3S) with history of agricultural activities were deciphered via functional annotation of putative ORFs (open reading frames) using KEGG KofamKOALA, PHMMER, the Cytochrome P450 Engineering Database CYPED v6.0, and the NCBI Batch Web CD-Search tool.

Results

Annotation revealed the detection of seventy-seven CYP families and eight standalone CYPs cutting across the three domains of life. The prokaryote CYPome has 72 CYP families, 93 subfamilies, and seven standalone CYPs. The phylum Proteobacteria and the genera Streptomyces, Mycobacterium, and Bacillus with 17, 16, 24, and 5 CYP families were predominant, while the domain Archaea was represented by CYP119A1. The phylum Cyanobacteria has two families, while 23 actinobacterial CYPs (other than Streptomyces and Mycobacterium) were also detected. The detected prokaryote CYPs are responsible for biodegradation of camphor, hydroxylation of monoterpene alcohols, biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, and hydroxylation of fatty acids and steroidal compounds. The eukaryote CYPome was represented by seven fungal CYPs (CYP505A3, CYP505B1, CYP51A, CYP51C, CYP55A1, CYP55A2, and CYP55A3) from Acremonium egyptiacum, Fusarium oxysporum, Aspergillus oryzae, Gibberella moniliformis, Aspergillus flavus, and Fusarium lichenicola, respectively, and CYP524A1 from the slime mold, Dictyostelium discoideum. The fungi CYPs were involved in biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, hydroxylation of fatty acids, and nitrate reduction and denitrification.

Conclusions

This study has established the diverse roles played by CYPs in soil, its implication for soil health and resilience, and its potentials for industrial application.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

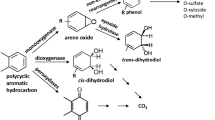

The cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYPs) comprise a large group of hemeproteins that catalyze a wide range of reactions, playing important roles in several fundamental biological processes (Danielson 2002). The majority of CYPs are monooxygenases, catalyzing the cleavage of dioxygen bound to their b-type heme iron, leading to the formation of a highly reactive ferryl iron-oxo intermediate, which catalyzes the insertion of an oxygen atom into the substrate (Girvan and Munro 2016). Several reaction outcomes such as hydroxylation and epoxidation, oxidative demethylation, dealkylation and deamination, oxidative and reductive dehalogenation, oxidation of alcohols and aldehydes, sulfoxidation, decarboxylation, among others result from oxidation of CYP substrates (Guengerich and Munro 2013). These reactions allow CYP enzymes to interact with both exogenous (such as drugs, plant secondary metabolites, and pollutants) and endogenous (such as steroids and fatty acids) compounds with highly diverse chemical structures and thus play a role in several critical physiological processes (Pankov et al. 2021).

Prokaryotic CYPs are soluble enzymes that lack the N-terminal membrane anchor, while the eukaryotic CYPs are bound to membranes with an N-terminal transmembrane helix. Functionally, prokaryotic CYPs are generally involved in biotransformation of xenobiotic compounds, biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, and hydroxylation of fatty acids and steroidal compounds (O’Keefe et al. 1988; Moody et al. 2012). Fungal CYPs are involved in diverse life processes such as production of primary and secondary metabolites, denitrification under anoxic conditions, among others. However, the CYPome of fungal species depends on their ecology and mode of life, a plausible reason why pathogenic forms have more CYPs than non-pathogenic or free-living forms (Pedrini et al. 2010; Shin et al. 2018). The abundance and diversity of CYPs in an environment can be an indicator of stress-induced functional shift. Their role in maintaining soil health via mineralization of natural organic compounds and detoxification of environmental pollutants and highly electronegative molecular species cannot therefore be over emphasized.

The soil environment is consistently inundated with coterie of pollutants from diverse sources. It is extremely difficult to find a polluted soil with a single pollutant. The presence of these pollutants imposes selective pressure on the microbial community, alters soil physicochemistry, reduces inorganic nutrients bioavailability, and potentiates changes in the direction of alternative metabolism and secondary metabolism, including bioactive compounds and toxicity and stress-induced resistances (Salam 2020; Salam and Obayori 2020; Salam et al. 2021). Understanding the potential of pollutants to disrupt community structure and functions has undergone a shift in the past decade or two from culture-dependent to culture-independent method, with more emphasis placed on metagenomic approach.

The chronically polluted soil (3S) is an environment with a dual history of agricultural activities that span more than 50 years followed by its use as automobile workshop where spent oils and other oils were routinely released into the environment. Physicochemical analysis of the polluted soil and functional characterization of 3S metagenome obtained from the soil revealed an environment that is grossly polluted as exemplified with the detection of hydrocarbon degradation genes, heavy metal resistance genes, and antibiotic resistance genes (Salam and Ishaq 2019; Salam 2020). However, while CYPs are often harbored by microorganisms for selective advantages and metabolic fitness, not much work has been done in the area of applying metagenomic approach to gain insight into the genomic potentials associated with CYPs in hydrocarbon impacted soils or similar environmental compartments.

Here, we report the detection of diverse CYP genes in the metagenome of a former agricultural soil which had witnessed over one decade of hydrocarbon pollution, with the aim of giving an insight into the functional properties of the CYPs harbored by members of the microbiome and how it accentuates their metabolic fitness and survival in the hydrocarbon-stressed environment.

Methods

Sampling site description and microcosm properties

The sampling site with coordinates of 8°28′ 42.4ʺ N and 4°32′15.6ʺ E is a hydrocarbon-polluted soil located in an automobile workshop at Taiwo, Ilorin, Nigeria. The site has a phased history of being used for agricultural activities for several decades, which is followed by its use till date as an automobile workshop with attendant history of hydrocarbon contamination for more than 10 years. Composite samples were collected at a depth of 10–12 cm with a sterile hand trowel, sieved (4 mm), and thoroughly mixed in a large plastic bag to avoid variability among the results of replicate soil samples. The sieved polluted soil (2 kg) was poured in open aluminum pans (37 cm × 14 cm × 7 cm) and designated 3S. The setup was done in triplicates. For DNA extraction, the samples (triplicate) were mixed and 0.25 g of the soil was used for the extraction. The physicochemistry of the soil (means of three replicates) revealed a weakly acidic pH (6.76), organic matter content of 1.35%, and the phosphorus, nitrogen, and potassium content of 6.38 mg/kg, 0.13%, and 0.15 mg/kg, respectively. The hydrocarbon content analysis revealed aliphatic hydrocarbon concentration of 1332.30 mg/kg, while the aromatic fraction is 1325.51 mg/kg, respectively (Salam and Ishaq 2019). Further information on the soil microcosm (polluted soil, 3S) setup, incubation conditions, physicochemical properties, and residual hydrocarbons has been reported previously (Salam and Ishaq 2019).

DNA extraction, shotgun metagenomics, and metagenome properties

Genomic DNA used for metagenomic analysis was extracted directly from 3S soil microcosm (0.25 g) using ZYMO soil DNA extraction Kit (Model D 6001, Zymo Research, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration and quality of the extracted DNA were ascertained using NanoDrop spectrophotometer and electrophoresed on a 0.9% (w/v) agarose gel, respectively. Shotgun metagenomic of 3S soil microcosm was prepared using the Illumina Nextera XT sample processing kit and sequenced on a MiSeq. The protocols for total DNA preparation for Illumina shotgun sequencing were described previously (Salam 2018; Salam and Ishaq 2019). Sequence reads from the 3S microcosm setup were assembled individually by VelvetOptimiser v2.2.5, and the resulting contigs fed into the MG-RAST metagenomic analysis pipeline. Pre-quality control analysis of the assembled sequences revealed 1239 contigs with a total of 314,848 bp, an average sequence length of 254 ± 66 bp, and the mean GC content of 61 ± 6%, respectively. Post-dereplication and quality control of 3S metagenome by MG-RAST revealed 1064 contigs with 260,627 bp, and an average sequence length of 245 ± 55 bp (Salam and Ishaq 2019). The data, metadata, and sequences of the 3S metagenome used in this study have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) at EMBL-EBI under accession number PRJEB36986 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/data/view/PRJEB36986).

Functional analyses of 3S metagenome for cytochrome P450 proteins

Gene calling to identify coding DNA sequences (CDSs) was performed on the 3S contigs using an ab initio gene prediction software, FragGeneScan (Rho et al. 2010) to predict open reading frames (ORFs). The ORFs were functionally annotated for cytochrome P450 proteins using KEGG KofamKOALA (Aramaki et al. 2020), PHMMER, a biosequence analysis tool that searches one or more query protein sequences against a protein sequence database using profile hidden Markov models (HMMER) (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/hmmer/search/phmmer), and the protein BLAST tool in the Cytochrome P450 Engineering Database CYPED v6.0 (Fischer et al. 2007). The ORFs were also functional annotated for cytochrome P450 using the NCBI Batch Web CD-Search tool (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/bwrpsb/bwrpsb.cgi). In all instances, the default parameters of the functional annotation tools were used.

Results

Functional analysis of ORFs of 3S metagenome for cytochrome P450 (CYP) proteins revealed that 3S CYPome comprises seventy-seven CYP families and eight standalone CYPs cutting across the three domains of life. The domain Bacteria had 72 CYP families, and Eukarya had five CYP families, while the domain Archaea has 1 CYP family. The detected CYPomes of the prokaryotic and eukaryotic communities in 3S metagenome and their taxonomic affiliation are depicted in Tables 1 and 2 (see Additional file 1: Table S1, Additional file 1: Table S2 for functions of the CYPs).

Prokaryote CYPome in 3S metagenome

Bacillus Cytochrome P450

Bacillus CYPome in 3S metagenome comprises five CYP families and 13 subfamilies (Table 1, Fig. 1). Abundance wise, CYP102 and CYP107, with four subfamilies (CYP102: A1, A2, A3, A5; CYP107: DY1, AA1, H1, J1) each, had the highest representation (31% each) among Bacillus CYPs. This is followed by CYP106 and CYP109 with two subfamilies (CYP106: A1, A2; CYP109: A1, B1), each contributing 15% to the Bacillus CYPs in the metagenome. CYP134 had only one subfamily (CYP134A1), constituting 8% of the Bacillus CYPs.

Distribution of cytochrome P450 genes constituting Bacillus CYPome in 3S metagenome. The CYPome comprises five CYP families and 13 subfamilies. Bacillus CYPs are dominated by CYP102 (CYP102A1, CYP102A2, CYP102A3, CYP102A5) and CYP107 (CYP107AA1, CYP107D1, CYP107H1, CYP107J1), respectively, contributing 62% of the Bacillus CYPs in the metagenome. The detected Bacillus CYPs are primarily responsible for biosynthesis of secondary metabolites and hydroxylation of fatty acids and steroidal compounds

Streptomyces cytochrome P450

Streptomyces CYPome in 3S metagenome comprises 16 CYP families, 27 subfamilies, and four standalone CYPs (aziB1, ncsB3, nlmB, and scnG) that do not belong to any of the existing CYP families (Table 1, Fig. 2). CYP105 with eight subfamilies (CYP105: A1, A3, B1, B2, C1, D1, H4, and L1) have the highest representation with 24% of Streptomyces CYPs in the metagenome. CYP107 members with four subfamilies (CYP107: D1, G1, L1, and L14) constitute 12% of the detected Streptomyces CYPs. CYP158, CYP161, and CYP163 with two subfamilies each cumulatively constitute 18% of the detected Streptomyces CYPs in the metagenome. Other detected Streptomyces CYPs are indicated in Table 1.

Distribution of cytochrome P450 genes constituting Streptomyces CYPome in 3S metagenome. Sixteen CYP families and four standalone CYPs (aziB1, ncsB3, nlmB, and scnG) that do not belong to any of the existing CYP families were detected. Streptomyces CYPs are dominated by CYP105 (CYP105A1, CYP105A3, CYP105B1, CYP105B2, CYP105C1, CYP105D1, CYP105H4, CYP105L1) and CYP107 (CYP107D1, CYP107G1, CYP107L1, CYP107L14), respectively, contributing 36% of the Streptomyces CYPs in the metagenome. The detected CYPs are responsible for biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, xenobiotics catabolism, biosynthesis of antibiotics, and hydroxylation of testosterone and bile acids

Mycobacterium cytochrome P450

Thirty-three CYPs belonging to 24 CYP families and 18 subfamilies were detected as members of Mycobacterium CYPome in 3S metagenome (Table 1, Fig. 3). While each of CYP123 and CYP140 constitutes 9% of the Mycobacterium CYPome, CYP124, CYP125, CYP135, CYP142, CYP143, and CYP187 with two subfamilies each cumulatively constitute 36% of the CYPome. Other detected Mycobacterium CYPs are indicated in Table 1.

Distribution of cytochrome P450 genes constituting Mycobacterium CYPome in 3S metagenome. Thirty-three CYPs belonging to 24 CYP families were detected as members of Mycobacterium CYPome. Majority (79%) of the detected CYPs were orphan CYPs that have no known assigned biological functions. The detected CYPs with biological functions are responsible for sterol biodegradation (CYP51, CYP124, CYP142), and biosynthesis of secondary metabolites (CYP128, CYP139, CYP140A7), some of which played prominent roles in virulence

Proteobacteria cytochrome P450

Seventeen CYP families with 16 subfamilies constitute the Proteobacteria CYPome detected in 3S metagenome (Table 1, Fig. 4) with CYP109 (CYP109C1, CYP109C2, CYP109D1) from Sorangium cellulosum and CYP133 (CYP133B1, CYP133B2) from Xylella fastidiosa constituting 29% of the CYPome. Three CYPs (CYP101A1, CYP108A1, and CYP111A2) were recovered from Pseudomonas species (CYP101A1, CYP108A1, CYP111A2), while seven CYPs (CYP109C1, CYP109C2, CYP109D1, CYP167A1, CYP265A1, CYP266A1, and CYP267A1) were recovered from the myxobacteria species Sorangium cellulosum strain So ce56. Rhizobium, Sinorhizobium, and Bradyrhizobium species were represented by CYP103, CYP104, CYP112, CYP114 and CYP127, while Halomonas chromatireducens was represented by CYP116.

Distribution of cytochrome P450 genes constituting Actinobacteria (other than Streptomyces and Mycobacterium) and Proteobacteria CYPome in 3S metagenome. Twenty CYPs belonging to 12 CYP families and three standalone CYPs (ebh, nocL, and pdmW) were annotated for Actinobacteria CYPome. Members of CYP107, CYP105, and CYP165 are preponderant in the CYPome contributing 44% of the Actinobacteria CYPs (A). In Proteobacteria CYPome, 17 CYP families with 16 subfamilies were annotated. Members of CYP109 and CYP133 are dominant constituting 25% of the CYPome (B). The detected CYPs are majorly involved in biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, catabolism of xenobiotics, and oxidative metabolism of monoterpenoids

Cytochrome P450 of other prokaryotes

The CYP genes of members of the phyla Actinobacteria (aside from Streptomyces and Mycobacterium) and Cyanobacteria as well as the domain Archaea were detected in 3S metagenome (Table 1, Fig. 4).

Four CYP107 subfamilies (CYP107A1, CYP107B1, CYP107BR1, and CYP107E1) were detected in three Actinobacteria genera Saccharopolyspora, Micromonospora, and Pseudonocardia constituting 18% of the CYPs. CYP105 (CYP105E1, CYP105L2, CYP105W2) and CYP165 (CYP165A3, CYP165B3, CYP165C4) each with three subfamilies cumulatively represent 26% of the CYPs. While CYP105 genes were recovered from Actinobacteria genera Micromonospora and Rhodococcus, CYP165 genes were recovered from Amycolatopsis orientalis (Table 1). Other detected actinobacterial CYPs include CYP113 (Saccharopolyspora erythraea), CYP125 (Mycolicibacterium smegmatis, Rhodococcus jostii), CYP163 (Salinispora tropica), CYP188-CYP190 (Mycolicibacter sinensis strain JDM601), CYP245 (Lechevalieria aerocolonigenes), among others (Table 1, Fig. 4). In addition, three standalone CYPs (ebh, nocL, and pdmW) not assigned to any known CYP families were also detected.

The phylum Cyanobacteria is represented in 3S metagenome by two CYPs., CYP110 from Nostoc sp. and CYP120A1 from Synechocystis sp., respectively, while CYP119A1 from Sulfolobus acidocaldarius is the only archaeal CYP detected in 3S metagenome (Table 1).

Eukaryote CYPome in 3S metagenome

The eukaryote CYPome in 3S metagenome comprises four CYP families, eight subfamilies, and ascE, a CYP not assigned to any of the existing CYP families (Table 2).

The fungi CYPome in 3S metagenome comprises three families (CYP505, CYP51, and CYP55), seven subfamilies (CYP505A3, CYP505B1, CYP51A, CYP51C, CYP55A1, CYP55A2, and CYP55A3), and ascE. The fungi CYPs were annotated for Acremonium egyptiacum, Fusarium oxysporum, Aspergillus oryzae, Gibberella moniliformis, Aspergillus flavus, and Fusarium lichenicola, respectively (Table 2). In addition, one CYP, CYP524A1 was annotated for the slime mold, Dictyostelium discoideum in the metagenome (Table 2).

Discussion

This study revealed the detection of 77 CYP families in 3S metagenome cutting across the three domains of life (Bacteria, 72 CYPs; Eukarya 4 CYPs; and Archaea 1 CYP). The low number recorded for Archaea may be attributed to the fact that Archaea are extremophiles adapted to environments with extremes of temperature, pH, salinity, or anaerobic conditions and in some cases a combination of more than one of these, which are characteristics of the 3S site. Furthermore, CYPs have not been well elucidated in the Archaea, unlike Bacteria and Eukarya, until lately when attention started shifting toward biotechnological applications of CYPs recovered from thermophilic Archaea and other extremophiles (Schallmey et al. 2011; Müller et al. 2018).

With a total of 45 out of 72 bacterial CYP families affiliated to Bacillus, Streptomyces, and Mycobacterium, these genera are the most represented in the CYPome. This may be attributed to the fact that they are members of the phyla Firmicutes and Actinobacteria which have consistently been reported to assume dominance in soils contaminated with petroleum hydrocarbons, attribute accounted for by their resilience to stressors and extreme conditions, including oligotrophy (Leahy and Colwell 1990; Kanaly and Harayama 2010; Salam and Obayori 2020). The Actinobacteria are particularly notable for their metabolic plasticity and possession of diverse gene batteries encoding enzymes with broad specificities (Salam and Obayori 2020).

All the four CYP102 (CYP102A1, CYP102A2, CYP102A3 and CYP102A5) subfamilies annotated in this study for Bacillus CYPome have been well studied. CYP102A1 is a unique monooxygenase with a redox partner diflavin reductase which clusters with eukaryotic P450s rather than prokaryotic P450s (Lewis et al. 1998). Several variants of the enzyme have been found in Bacillus megaterium. Naturally exhibiting catalytic activity against long-chain fatty acids at the subterminal position, its potential for exploitation in biocatalytic production of drugs, short-chain hydrocarbons, and xenobiotics has been explored (Kang et al. 2011). CYP102A1 shares high level of structural and functional similarities with CYP102A2 and CYP102A3 from Bacillus subtilis (Budde et al. 2004; Lentz et al. 2006; Dietrich et al. 2008). CYP102A5, on the other hand, catalyze alongside unsaturated fatty acid, N-acylamino acids with higher specificity and yield than other CYP102 subfamilies (Chowdhary et al. 2007). Generally, the enzymes encoded by the CYP102 genes have been identified as a group that can be engineered for industrial applications.

The genes encoding CYP107 (detected in this study) are among those reported to belong to biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) of Bacillus species constituting 61% (n = 68) of those reported in the database (Mthethwa et al. 2018). CYP107 have been found to be more highly conserved in Bacillus and Streptomyces (Mnguni et al. 2020), and many are involved in the synthesis of macrolide antibiotics (Kim et al. 2020). One of the subfamilies of this group annotated in this study CYP107DY1 is a recently discovered plasmid encoded protein in Bacillus megaterium, which acts on mevastatin to produce pravastatin, a drug used in the treatment of hypercholesterolemia (Milhim et al. 2016). Also worth mentioning is CYP107J1 (CYPA) detected in this study. The enzyme encoded by this gene is involved in hydroxylation of polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB), a notorious environmental pollutant (Sun et al. 2017). CYP109B1 which trailed behind CYP102 and CYP107 alongside CYP106 in the Bacillus CYPome belongs to a family noted for its activity on saturated fatty acids and primary n-alcohols but not on alkanes (Girhard et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2015).

Aside from their catabolic competence on diverse hydrocarbon moieties (Baoune et al. 2019), Streptomyces species are well-known producer of chemically diverse secondary metabolites that are used in human medicine as antibiotics, anti-infectives, anti-fibrotic, antitumor, and immunosuppressant drugs, and it is estimated that they produce > 50% of commercially available antibiotics (Lima Procópio et al. 2012; Senate et al. 2019). It is therefore not surprising that majority (85%; CYP28, CYP105, CYP107, CYP113, CYP129, CYP151, CYP161, CYP162, CYP163, CYP170, CYP183, CYP244, CYP245, scnG, ncsB3, aziB1) of the Streptomyces CYPs annotated in this study are involved in biosynthesis of secondary metabolites (McLean et al. 2015; Mnguni et al. 2020). This includes neopentalenolactone/pentalenolactone (CYP28, CYP161C3, CYP183A1), benanomicin A (CYP105C1), compactin (CYP105A3), tylosin (CYP105L1, CYP113B1), amphotericin (CYP105H4, CYP161A3), pikromycin, methymycin, neomethymycin (CYP107L1), rapamycin, oleandomycin (CYP107G1, CYP244A1, CYP245A1, CYP107D1), among others (Additional file 1: Table S1). In the Streptomyces CYPome, the CYP107 family constituted 12% even as the majority were CYP105 (24%) and a host of standalone CYPs involved in the biosynthesis off the enediyne antitumor antibiotic neocarzinostatin (ncsB3), azinomycin B (aziB1), as well as natamycin (Hang et al. 2010; Ding et al. 2010; Liu et al. 2015). Even though CYP107 were not associated with Mycobacterium, also a member of the Actinobacteria, it is interesting that four CYP107 subfamilies (CYP107A1, CYP107B1, CYP107BR1, and CYP107E1) associated with other Actinobacteria genera Saccharopolyspora, Micromonospora, and Pseudonocardia and found to be involved in catabolism of xenobiotics, biosynthesis of erythromycin and mycinamicin, and hydroxylation of vitamin D3 to its active form were annotated (McLean et al. 2015; Mnguni et al. 2020). This further buttresses the possible role of this phylum in biosynthesis of secondary metabolites and metabolism of xenobiotics in the 3S soil.

Also prominent are the CYP105 subfamilies both in the Streptomyces CYPome and other Actinobacteria genera such as Micromonospora and Rhodococcus. The secondary metabolites biosynthesized by CYP105 subfamilies such as mycinamicin and the antitumor antibiotic calicheamicin in Micromonospora are important antibiotics (Greule et al. 2018), while CYP105B1 (P450-SU-2) have been fingered in the metabolism of sulfonylurea herbicides. Homologues of CYP105 are found in all Streptomyces and are predominantly found in Actinobacteria (Moody and Loveridge 2014). Just like CYP107, they are generally involved in biosynthesis of secondary metabolites and xenobiotic catabolism, and while some show narrow substrate specificity, others demonstrate broad substrate specificity with potential for biotechnological applications (Xu et al. 2010; Podust and Sherman 2012; Li et al. 2013). Taken together with the detection of biosynthetic CYPs of other antibiotics like erythromycin (CYP107A1 eryF; CYP113A1 eryK), vancomycin (CYP165A3 oxyA; CYP165B3 oxyB; CYP165C4 oxyC), pradimicin (pdmW) associated with other Actinobacteria (Napan et al. 2014; McLean et al. 2015) in this study, it is plausible that the Actinobacteria group, apart from being resistant to hydrocarbon pollution, may also rely on such capability to have an edge in competing for survival in such environment. This assertion is further buttressed by the realization that 85% of Streptomyces CYPs detected in this study are involved in biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, which the members of the genus routinely produced as a form of adaptation, and to confer selective advantage in a nutritionally deficient, stressed, chronically polluted soil environment. Thus, Streptomyces CYPs are by necessity primed for secondary metabolite production to support the genus lifestyle and ecological niche (Mnguni et al. 2020).

In contrast to Streptomyces species, the genus Mycobacterium comprises of species that are well-known pathogens of humans and other animals, despite some saprophytes being present in the genus (Ventura et al. 2007; Parvez et al. 2016). The pathogenic nature of mycobacterial species forced them to adapt to parasitic lifestyles where living in a host, evading the host’s immune system, and utilizing host carbon sources for survival are the prime tasks (Mnguni et al. 2020). To sustain this lifestyle, mycobacterial CYPs are carefully acquired to serve as biocatalyst for the utilization of host lipids or synthesis of novel lipids. These assertions were strengthened by findings in this study which shows that though majority (26, 79%) of the detected mycobacterial CYPs were orphan CYPs that have no known assigned biological functions, the few CYPs with functions were only annotated for sterol biodegradation (CYP51, CYP124, CYP142), and biosynthesis of secondary metabolites (CYP128, CYP139, CYP140A7), some of which play prominent role in Mycobacterium virulence (McLean et al. 2015). Interest in the M. tuberculosis CYPome is driven mainly by the need to understand the role the enzymes encoded play in the establishment of infection as a way of identifying potential drug targets and developing effective drugs (McLean et al. 2008; Ouellet et al. 2010; Ortiz de Montellano 2018). Indeed, some of the CYP families detected in this study, including CYP125 and CYP142, have been found to be promising targets of anti-tuberculosis therapeutics (Chang et al. 2009; Hudson et al. 2013; Ortiz de Montellano 2018). It is worth noting, however, that in terms of source, the Mycobacterium CYPs recovered in this study may have come more likely from human sources as the automobile workshop is usually a hub of human activities open to contamination, even though as it is a well-known fact that Mycobacterium species also play very important role in hydrocarbon degradation, especially polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (Kanaly and Harayama 2010).

Of the seventeen CYP families that constitute the Proteobacteria CYPome detected in 3S metagenome, seven CYPs were annotated for Sorangium cellulosum So ce56, a myxobacterial soil bacterium reputed as a producer of important secondary metabolites (Khatri et al. 2010). Of the seven CYPs, three (CYP167A1, CYP265A1, and CYP266A1) were involved in the biosynthesis and hydroxylation of epothilone D (Kern et al. 2015). CYP167A1 is responsible for the last step in epothilone biosynthesis in Sorangium cellulosum So ce56, catalyzing the epoxidation of epothilone D to epothilone B (Julien et al. 2000), while CYP265A1 and CYP266A1 were involved in hydroxylation of epothilone D to generate hydroxylated epothilones 14-OH epothilones (Kern et al. 2015). Epothilones are a family of novel microtubule-stabilizing agents, which inhibit mitosis and thus prevent cancer cells from dividing via obstruction of microtubule depolymerization, thereby causing G2-M interphase arrest of the cell cycle with subsequent cytotoxicity and eventual cancer cell apoptosis (Molner et al. 2000; Goodin et al. 2004). The detection of these CYPs in 3S soil highlights the importance of the soil environment as a repository of natural products with extensive functionalities. Aside the detection of genes for epothilone biosynthesis and hydroxylation in Sorangium cellulosum So ce56, other CYPs annotated for this genus are involved in hydroxylation of fatty acids (Khatri et al. 2013). The three CYPs (CYP101A1, CYP108A1, and CYP111A2) annotated for Pseudomonas Spp. are catabolic genes involved in hydroxylation of camphor, and oxidative metabolism of monoterpenoids α-terpinol, and linalool, which has multiple commercial applications (Greule et al. 2018). Previously, Pseudomonas Cytochrome P450 involvement have been documented for toxic pesticides such as 1,2-dichloromethane and propiconazole (Hage and Hartman 1999; Satapute and Kaliwal 2016) and recently, Balaraman and Plettner (2019) elucidated the functional role of P450 in camphor uptake. Recovery of these cytochromes from an automobile workshop where hydrocarbon and other hydrocarbon-derived contaminants were in high concentration could be a pointer to the role of P450 in the degradation of these pollutants in 3S. The detection of CYP103 and CYP104 involved in detoxification of plant protective agents at the site of wounding from the phytopathogen Rhizobium radiobacter (formerly Agrobacterium tumefaciens) and CYP112 and CYP114 involved in the biosynthesis of the phytohormone gibberellin (Nagel et al. 2018) from Sinorhizobium and Bradyrhizobium spp. is a confirmation of the historical antecedent of agricultural activities at the 3S polluted soil.

The phylum Cyanobacteria are foremost autotrophic components of soil microbiomes, which plays key ecological roles in nutrient cycling and soil productivity (Hakkoum et al. 2021). While they are well adapted to hostile terrestrial environments such as extremely arid and dryland areas, their population and diversity often took a hit in hydrocarbon-polluted soils (Salam et al. 2017; Salam and Idris 2019). In this study, two CYPs, CYP110 and CYP120A1, were annotated for Cyanobacteria spp. Nostoc sp. strain PCC 7120, and Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. CYP110 is involved in omega oxidation of saturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids and subsequent formation of dicarboxylic acids, which thereafter undergo β-oxidation (Van Bogaert et al. 2011). CYP120A1 detected in this study have been reported to encode the first non-animal retinoic acid-metabolizing enzyme, retinoic acid hydroxylase, which has broad substrate specificity on cis-retinoic acid, retinal, 3R-OH-retinal, retinol, β-apo-13-carotenone (C(18)) and β-apo-14′-carotenal (C(22)), respectively (Alder et al. 2009).

Fungal CYPs are involved in diverse life processes such as production of primary and secondary metabolites; but generally, the CYPome of species depends on their ecology and mode of life, a plausible reason why pathogenic forms have more CYPs than non-pathogenic or free-living forms (Pedrini et al. 2010; Shin et al. 2018). Some of the fungi for which CYP genes were annotated in this study such as Aspergillus flavus, Fusarium oxysporum, and Fusarium lichenicola are common soil flora with well-described CYPs. However, the small number of genes annotated for fungi may not be unconnected to the limited role they play in the polluted soil, as only those able to survive the toxicity would persist. The genes encoding CYPs associated with the biosynthesis of ascfuranone and ascochlorin, namely CYP505A3 and CYP505A1, were annotated in this study. These enzymes catalyze the generation of ilicicolin A epoxide. These metabolites have generated interest as a result of their potential as drug candidate for trypanosomal parasite (Araki et al. 2019). The CYP55 subfamilies identified in this study, namely CYP55A1, CYP55A2, and CYP55A3, are well documented in the literature as fungal CYPs functional in denitrification under anoxic condition (Kudo et al. 1996; Kaya et al. 2004; Shin et al. 2018). All CYP55s are part of a two-component fungal denitrification system consisting of NorK (a copper containing nitrite reductase) and P450nor (a cytochrome P450 nitric oxide reductase (Nor) localized in the mitochondrion (Shoun et al. 2012) and have been identified in ascomycetous fungi including Fusarium oxysporum, Fusarium linicola, and Aspergillus oryzae.

Conclusions

Metagenomic assessment of the cytochrome P450 genes of an automobile workshop with previous history of use as agricultural soil and subsequent over a decade-long contamination with petroleum hydrocarbons and other automobile waste pollutants revealed diverse CYPomes spanning prokaryotes and eukaryotes in 77 CYP families. Although majority of the families (73) were annotated for prokaryotes, these were mainly in the phyla noted as important hydrocarbon degraders (Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Firmicutes), thus indicating concurrence in pollution-induced reduction in phylotype diversity and CYPome richness. Furthermore, CYPs encoding enzymes with potential industrial applications were also annotated. We also note the poor showing by the fungal CYPs and attribute this to their possible limited role in the polluted soil. Future study will have to be directed to targeting some of the CYP genes annotated for functions of biotechnological interest with the aim of evaluating their prospects for useful application.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- CYP:

-

Cytochrome P450 monooxygenase

References

Alder A, Bigler P, Werck-Reichhart D, Al-Babili S (2009) In vitro characterization of Synechocystis CYP120A1 revealed the first non-animal retinoic acid hydroxylase. FEBS J 276(19):5416–5431

Araki Y, Awakawa T, Matsuzuzaki M, Cho R, Matsuda Y, Hoshi J et al (2019) Complete biosynthetic pathways of ascofuranone and ascochlorin in Acremomium egyptiacum. PNAS 116(17):8269–8274. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1819254116

Aramaki T, Blanc-Mathieu R, Endo H, Ohkubo K, Kanehisa M, Goto S, Ogata H (2020) KofamKOALA: KEGG ortholog assignment based on profile HMM and adaptive score threshold. Bioinformatics 36(7):2251–2252. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz859

Balaraman P, Plettner E (2019) Chemotaxis by Pseudomonas putida (ATCC 17453) towards camphor involves cytochrome P450cam (CYP101A1). Biochim et Biophys Acta General Subj 2:304–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2018.10.018

Baoune H, Aparicio JD, Pucci G et al (2019) Bioremediation of petroleum-contaminated soils using Streptomyces sp. Hlh1. J Soils Sediments 19:2222–2230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-019-02259-w

Budde M, Maurer SC, Schmid RD, Urlacher VB (2004) Cloning, expression, and characterization of CYP102A2, a self-sufficient P450 monooxygenase from Bacillus subtilis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 66(2):180–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-004-1719-y

Chang JC, Miner MD, Pandey AK, Gill WP, Harik NS, Sassetti CM, Sherman DR (2009) igr Genes and Mycobacterium tuberculosis cholesterol metabolism. J Bacteriol 191:5232–5239. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.004452-09

Chowdhary PK, Alemseghed M, Haines DC (2007) Cloning, expression, and characterization of a fast self-sufficient P450: CYP102A5 from Bacillus cereus. Arch Biochem Biophys 468(1):32–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2007.09.010

de Lima Procipio RE, da Silva IR, Martin’s MK, de Azevedo JL, de Araujo JM (2012) Antibiotics produced by Streptomyces. Brazilian J Infect Dis 16(5):466–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjid.2012.08.014

Dietrich M, Eiben S, Asta C, Do TA, Pleiss J, Urlacher VB (2008) Cloning, expression and characterization of CYP102A7, a self-sufficient P450 monooxygenase from Bacillus licheniformis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 79(6):931–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-008-1500-8

Ding W, Deng W, Tang M, Zhang Q, Tang G, Bi Y, Liu W (2010) Biosynthesis of 3-methoxy-5-methyl naphthoic acid and its incorporation into the antitumor antibiotic azinomycin B. Mol Biosyst 6(6):1071–1081

Fischer M, Knoll M, Sirim D, Wagner F, Funke S, Pleiss J (2007) The cytochrome P450 engineering database: a navigation and prediction tool for the cytochrome P450 protein family. Bioinformatics 23(15):2015–2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btm268

Girhard M, Klaus T, Khatri Y, Bernhardt R, Urlacher VB (2010) Characterization of the versatile monooxygenase CYP109B1 from Bacillus subtilis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 87(2):595–607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-010-2472-z

Girvan HM, Munro AW (2016) Applications of microbial cytochrome P450 enzymes in biotechnology and synthetic biology. Curr Opin Chem Biol 31:136–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.02.018

Goodin S, Kane MP, Rubin EH (2004) Epothilones: mechanism of action and biologic activity. J Clin Oncol 22(10):2015–2025. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2004.12.001

Greule A, Stok JE, De Voss JJ, Cryle MJ (2018) Unrivalled diversity: the many roles and reactions of bacterial cytochromes P450 in secondary metabolism. Nat Prod Rep 35(8):757–791. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7NP00063D

Guengerich FP, Munro AW (2013) Unusual cytochrome P450 enzymes and reactions. J Biol Chem 288:17065–17073. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.R113.462275

Hage JC, Hartmans S (1999) Monooxygenase-mediated 1,2-dichloroethane degradation by Pseudomonas sp. strain DCA1. Appl Environ Microbiol 65:2466–2470. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.65.6.2466-2470.1999

Hakkoum Z, Minaoui F, Douma M, Mouhri K, Loudiki M (2021) Impact of human disturbances on soil cyanobacteria diversity and distribution in suburban arid area of Marrakesh, Morocco. Ecol Process 10:42

Hang VTT, Oh TJ, Yamaguchi T, Sohng JK (2010) In vivo characterization of NcsB3 to establish the complete biosynthesis of the naphthoic acid moiety of the neocarzinostatin chromophore. FEMS Microbiol Lett 311(2):119–125

Hudson SA, Surade S, Coyne AG, McLean KJ, Leys D, Munro AW, Abell C (2013) Overcoming the limitations of fragment merging: rescuing a strained merged fragment series targeting Mycobacterium tuberculosis CYP121. ChemMedChem 8:1451–1456. https://doi.org/10.1002/cmdc.201300219

Julien B, Shah S, Ziermann R, Goldman R, Katz L, Khosia C (2000) Isolation and characterization of the epothilone biosynthetic gene cluster from Sorangium cellulosum. Gene 249(1–2):153–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00149-9

Kanaly RA, Harayama S (2010) Advances in the field of high-molecular-weight polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon biodegradation by bacteria. Microbial Biotechnol 3(2):132–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-7915.2009.00130.x

Kang JY, Kim SY, Kim D et al (2011) Characterization of diverse natural variants of CYP102A1 found within a species of Bacillus megaterium. AMB Express 1(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2191-0855-1-1

Kaya M, Matsumura K, Higashida K, Hata Y, Kawato A, Abe Y, Akita O, Takaya N, Shoun H (2004) Cloning and enhanced expression of the cytochrome P450nor gene (nicA; CYP55A5) encoding nitric oxidereductase from Aspergillus oryzae. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 68:2040–2049. https://doi.org/10.1271/bbb.68.2040

Kern F, Dier TKF, Khatri Y, Ewen KM, Jacquot J-P, Volmer DA, Bernhardt R (2015) Highly efficient CYP167A1 (EpoK) dependent epothilone B formation and production of 7-ketone epothilone D as a new epothilone derivative. Sci Rep 5:14881. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep14881

Khatri Y, Hannemann F, Ewen KM et al (2010) The CYPome of Sorangium cellulosum So ce56 and identification of CYP109D1 as a new fatty acid hydtroxylase. Chem Biol 17(12):1295–1305

Khatri Y, Hannemann F, Girhard M et al (2013) Novel family members of CYP109 from Sorangium cellulosum So ce56 exhibit characteristic biochemical and biophysical properties. Biotechnol Appl Biochem 60(1):18–29

Kim V, Lim YR, Lee I et al (2020) Structural insights into CYP107G1 from rapamycin-producing Streptomyces rapamycinicus. Arch Biochem Biophys 692:108544

Kudo T, Tomura D, Liu DL, Dai XQ, Shoun H (1996) Two isozymes of P450nor of Cylindrocarpon tonkinense: molecular cloning of the cDNAs and genes, expressions in the yeast, and the putative NAD(P)H-binding site. Biochimie 78(8–9):792–799. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0300-9084(97)82538-2

Leahy JG, Colwell RR (1990) Microbial degradation of hydrocarbons in the environment. Microbiol Rev 54:305–315

Lentz O, Feenstra A, Habicher T, Hauer B, Schmid RD, Urlacher VB (2006) Altering the regioselectivity of cytochrome P450 CYP102A3 of Bacillus subtilis by using a new versatile assay system. ChemBioChem 7(2):345–350. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbic.200500266

Lewis DF, Eddershaw PJ, Dickins M, Tarbit MH, Goldfarb PS (1998) Structural determinants of cytochrome P450 substrate specificity, binding affinity, and catalytic rate. Chem Biol Interact 115(3):175–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0009-2797(98)00068-4

Li ZZ, Li XF, Yang W et al (2013) Identification and functional analysis of cytochrome P450 complement in Streptomyces virginiae IBL14. BMC Genomics 14:130

Liu S-P, Yuan P-H, Wang Y-Y et al (2015) Generation of the natamycin analogs by gene engineering of natamycin biosynthetic genes in Streptomyces chattanoogensis L10. Microbiol Res 173:25–33

McLean KJ, Carroll P, Lewis DG et al (2008) Characterization of active site structure in CYP121: a cytochrome P450 essential for viability of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. J Biol Chem 283:33406–33416

McLean KJ, Luciakova D, Belcher J, Tee KL, Munro AW (2015) Biological diversity of cytochrome P450 redox partner systems. Adv Exp Med Biol 851:299–317

Milhim M, Putkaradze N, Abdulmughni A, Kern F, Hartz P, Bernhardt R (2016) Identification of a new plasmid-encoded cytochrome P450 CYP107DY1 from Bacillus megaterium with a catalytic activity towards mevastatin. J Biotechnol 20(240):68–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.11.002

Mnguni FC, Padayachee T, Chen W, Gront D, Yu JH, Nelson DR, Syed K (2020) More P450s are involved in secondary metabolite biosynthesis in Streptomyces compared to Bacillus, Cyanobacteria, and Mycobacterium. Int J Mol Sci 21(13):4814. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21134814

Molner I, Schupp T, Ono M et al (2000) The biosynthetic gene cluster for the microtubule-stabilizing agents epothilone A and B from Sorangium cellulosum So ce90. Chem Biol 7(2):97–109

Moody S, Loveridge EJ (2014) CYP105—diverse structures, functions, and roles in an intriguing family of enzymes in Streptomyces. J Appl Microbiol 117:1549–1563

Moody SC, Zhao B, Lei L, Nelson DR, Mullins JG, Waterman MR, Kelly SL, Lamb DC (2012) Investigating conservation of the albaflavenone biosynthetic pathway and CYP170 bifunctionality in streptomycetes. FEBS J 279(9):1640–1649

Mthethwa BC, Chen W, Ngwenya ML et al (2018) Comparative analyses of cytochrome P450s and those associated with secondary metabolism in Bacillus species. Int J Mol Sci 19(11):3623

Müller WJ, Smit MS, van Heerden E, Capes MD, DasSarma S (2018) Complex effects of cytochrome P450 monooxygenase on purple membrane and bacterioruberin production in an extremely halophilic archaeon: genetic, phenotypic, and aranscriptomic Analyses. Front Microbiol 9:2563

Nagel R, Bieber JE, Schmidt-Dannert MG, Nett RS, Peters RJ (2018) A third-class: functional gibberellin biosynthetic operon in beta-proteobacteria. Front Microbiol 9:2916

Napan K, Zhang S, Morgan W, Anderson T, Takemoto JY, Zhan J (2014) Synergistic actions of tailoring enzymes in pradimicin biosynthesis. ChemBioChem 15:2289–2296

O’Keefe DP, Romesser JA, Leto KJ (1988) Identification of constitutive and herbicide inducible cytochrome P-450 in Streptomyces griseolus. Arch Microbiol 149(5):406–412

Ortiz de Montellano PR (2018) Potential drug targets in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis cytochrome P450 system. J Inorg Biochem 180:235–245

Ouellet H, Johnston JB, Ortiz de Montellano PR (2010) The Mycobacterium tuberculosis cytochrome P450 system. Arch Biochem Biophys 493(1):82–95

Pankov KV, McArthur AG, Gold DA, Nelson DR, Goldstone JV, Wilson JY (2021) The cytochrome P450 (CYP) superfamily in cnidarians. Sci Rep 11(1):9834. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-88700-y

Parvez M, Qhanya LB, Mthakathi NT et al (2016) Molecular evolutionary dynamics of cytochrome P450 monooxygenases across kingdoms: Special focus on mycobacterial P450s. Sci Rep 6:33099. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep33099

Pedrini N, Zhang S, Juárez MP, Keyhani NO (2010) Molecular characterization and expression analysis of a suite of cytochrome P450 enzymes implicated in insect hydrocarbon degradation in the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana. Microbiology (Read Engl) 156(Pt 8):2549–2557. https://doi.org/10.1099/mic.0.039735-0

Podust LM, Sherman DH (2012) Diversity of P450 enzymes in the biosynthesis of natural products. Nat Prod Rep 29:1251–1266

Rho M, Tang H, Ye Y (2010) FragGeneScan: predicting genes in short and error-prone reads. Nucleic Acid Res 38:20–191

Salam LB (2018) Detection of carbohydrate-active enzymes and genes in a spent engine oil-perturbed agricultural soil. Bull Natl Res Center 42:10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-018-0013-6

Salam LB (2020) Unravelling the antibiotic and heavy metal resistome of a chronically polluted soil. 3 Biotech 10(6):1–23

Salam LB, Idris H (2019) Consequences of crude oil contamination on the structure and function of allochthonous microbial community of a tropical agricultural soil. Environ Sustain 2(2):167–187

Salam LB, Ishaq A (2019) Biostimulation potentials of corn steep liquor in enhanced hydrocarbon degradation in chronically polluted soil. 3 Biotech 9:46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-019-1580-4

Salam LB, Obayori OS (2020) Remarkable shift in structural and functional properties of an animal charcoal-polluted soil accentuated by inorganic nutrient amendment. J Genet Eng Biotechnol 18:70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43141-020-00089-9

Salam LB, Obayori OS, Nwaokorie FO, Suleiman A, Mustapha R (2017) Metagenomic insights into effects of spent engine oil perturbation on the microbial community composition and function in a tropical agricultural soil. Environ Sci Pollut Res 24:7139–7159

Salam LB, Obayori OS, Ilori MO, Amund OO (2021) Impact of spent engine oil contamination on the antibiotic resistome of a tropical agricultural soil. Ecotoxicology 30:1251–1271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10646-021-02422-5

Satapute P, Kaliwal B (2016) Biodegradation of the fungicide propiconazole by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PS-4 strain isolated from a paddy soil. Ann Microbiol 66:1355–1365

Schallmey A, den Besten G, Teune IGP et al (2011) Characterization of cytochrome P450 monooxygenase CYP154H1 from the thermophilic soil bacterium Thermobifida fusca. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 89:1475–1485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-010-2965-9

Senate LM, Tjatji MP, Pillay K et al (2019) Similarities, variations, and evolution of cytochrome P450s in Streptomyces versus Mycobacterium. Sci Rep 9:3962. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40646-y

Shin J, Kim J-E, Lee Y-W, Son H (2018) Fungal cytochrome P450s and the P450 complement (CYPome) of Fusarium graminearum. Toxins 10(3):112

Shoun H, Fushinobu S, Jiang L, Kim S-W, Wakagi T (2012) Fungal denitrification and nitric oxide reductase cytochrome P450nor. Phil Trans Biol Sci 367(1593):1186–1194

Sun J, Pan L, Zhu L (2017) Formation of hydroxylated and methoxylated polychlorinated biphenyls by Bacillus subtilis: new insights into microbial metabolism. Sci Total Environ 613–614:54–61

Van Bogaert INA, Groeneboer S, Saerens K, Soetaert W (2011) The role of cytochrome P450 monooxygenases in microbial fatty acid metabolism. FEBS J 278:206–221

Ventura M, Cnchaya C, Tauch A, Chandra G, Fitzgerald GF, Chater KF, van Sinderen D (2007) Genomics of Actinobacteria: tracing the evolutionary history of an ancient phylum. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 71:495–548

Xu LH, Fushinobu S, Takamatsu S, Wakagi T, Ikeda H, Shoun H (2010) Regio-and stereospecificity of filipin hydroxylation sites revealed by crystal structures of cytochrome P450 105P1 and 105D6 from Streptomyces avermitilis. J Biol Chem 285:16844–16853

Zhang A, Zhang T, Hall EA, Hutchinson S, Cryle MJ, Wong LL, Zhou W, Bell SG (2015) The crystal structure of the versatile cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP109B1 from Bacillus subtilis. Mol Biosyst 11(3):869–881. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4mb00665h

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

No external funding was received to conduct this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LBS conceived the study and performed the experiments and wrote the Materials and Methods and Results. OSO coordinated the study and in consultation with LBS wrote the Introduction and Discussion. MOI and OOA contributed to Discussion section. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethic approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

. Table S1. Detected Cytochrome P450 proteins constituting the CYPome of the prokaryotic community of 3S metagenome and their functions. Table S2. Detected Cytochrome P450 proteins constituting the CYPome of the eukaryotic community of 3S metagenome and their functions.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Salam, L.B., Obayori, O.S., Ilori, M.O. et al. Deciphering the cytochrome P450 genes in the microbiome of a chronically polluted soil with history of agricultural activities. Bull Natl Res Cent 46, 256 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-022-00947-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-022-00947-1