Abstract

Arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) symbiosis is heavily and positively implicated in phosphorus (P) acquisition from soil to plants, including many important agricultural crops. Its role in plant nitrogen (N) nutrition is generally not as prominent or beneficial, with exception of some situations when N is available predominantly in organic forms. Yet the AM fungi (AMF) are, due to their poor exo-enzymatic repertoire, unlikely to degrade organic compounds on their own, therefore they possibly depend on other microorganisms to liberate nutrients contained in those materials. Here, we review current knowledge on the roles played by the AMF in plant N nutrition in general and uptake of N from organic compounds in particular, with a specific reference to microbes and processes involved in liberation and AM fungal utilization of N from organic compounds. Future research needs and directions are outlined, as is the agronomic and societal context of such research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction—setting the scene

Nitrogen (N) is an integral part of a number of macromolecules supporting all life on Earth, including nucleic acids, proteins, some polysaccharides (e.g., chitin and chitosan) and a wide range of secondary metabolites. It is, thus, present in all living cells and is consequently regarded as one of the vitally important macronutrients (biogenic elements) for the life as we know it. The N-rich organic materials such as farmyard and green manures, composts and guano have been used for millennia to sustain sedentary agriculture [32]. Since about 100 years, large amounts of mineral N fertilizers have been manufactured through the Haber–Bosch ammonia synthesis with energy and hydrogen inputs from fossil fuels, mainly natural gas [17]. This single chemical invention, together with widespread use of potent pesticides and breeding for high-yielding crop cultivars, have together made what we refer to as Green Revolution, which allowed unprecedented yield increases and literally detonated the human population explosion, driving the world’s population from 1.6 billion in 1900 to current approximately 8 billion [110]. Even though mineral N fertilizers did play a major role in the Green Revolution, their use poses a great risk of environmental pollution, degradation of soil quality, and great societal dependency on fossil energy. As the production of mineral N fertilizers is an energy intensive process, it will consequently be very difficult to maintain any close to the current production levels, shall the availability of fossil energy thin or vanish in the future [33, 129]. As the world population would only reach a maximum of about 4 billion without synthetic N fertilizers today, the other half of the world population is literally reliant on the Haber–Bosch process and, therefore, on fossil energy supplies [26].

Agriculture has always been a system out of (natural) balance, aiming at suppressing weeds and pathogens and maximizing yields of only a few or a single crop/product. Current agricultural practices reached much closer to the theoretical yield/production potential of many agricultural products than ever before, with further perspectives of closing the crop yield gap by fertilizers, supplementary irrigation, modern breeding and novel management options, e.g., precision agriculture [18, 121]. However, the humanity at the same time also achieved the lowest levels of global food reserves and the highest dependency on global reshuffling of resources than ever before. Therefore, the imminent danger of shortage of suppy of food, feed, and other agricultural commodities arises shall any of the current agricultural or linked resources be performing weakly under future stress scenarios. The scenarios include, among others: emergence of novel pathogens; drought or heat spells; lack of pollinators; low availability of mineral N and phosphorus (P) fertilizers, energy and/or pesticides; major soil losses due to erosion; and further degradation of soil and ground water quality [21, 36, 40].

Relying on mineral N fertilizers, conventional agricultural production literally feeds on finite fossil energy in large parts of the world today—and, at the same time, silently accepting rather low mineral N fertilizer use efficiency (with the maximum at around 50%) and immense environmental costs, particularly with respect to soil and water quality [98]. Fostering the transition of a significant portion of agricultural lands to more sustainable organic management is, thus, urgently required to improve both global ecosystem sustainability and resilience of the food production systems to current and future challenges [114]. This is because organic agriculture helps recycling organic waste, improves soil quality and organic food generally has a smaller environmental footprint than conventionally produced food (though it still requires judicious management of inputs), which all may be important with respect to mitigation of and adapting to climate changes [47, 70, 88]. Additionally, supporting personal modesty as a counterbalance to civilization of endless consumption must be encouraged; while at the same time, an increased level of agricultural productivity is required to feed the growing world population with rising demand for high quality food. As the altered needs of human civilization mutually interact with the Earth ecosystem, it could remain within habitable boundaries [115]. Therefore, future agricultural production systems will need to rely, more than ever, on healthy soil and its inhabitants, dedicating particular attention to maintaining and promoting soil quality. In this review, we summarize current knowledge on the roles played by the omnipresent yet still broadly under-appreciated arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) in N cycling in soil–plant systems in general and recycling organic N from soil to plant in particular.

Arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis and nitrogen cycling

The AMF are establishing so-called arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) symbiosis with majority (> 60%) of extant plant species [111]. This means that AMF can be regarded as an important biological soil resource. This is because the AM symbiosis, an intimate co-existence between the AMF and roots of their host plants, plays a substantial role in mineral nutrition, abiotic stress tolerance and pathogen resistance of the plants including many important agricultural crops such as wheat, maize, rice, banana, potato or sunflower [83, 95, 112]. Further, the AM symbiosis apparently plays a pivotal role in maintenance of diversity of plant communities through redistribution of symbiotic costs and benefits between individuals of the same or different plant species through so-called common mycorrhizal networks [7, 28, 131].

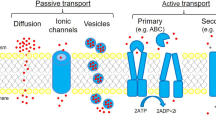

The AMF hyphae interconnect soil with the cortical cells of roots, establishing a unique and direct pathway to shuffling nutrients from the soil to plants and reduced carbon (C) in the other direction [82, 97, 132]. However, this connection is not very likely to facilitate any significant direct interplant nutrient and/or C transfers [30, 31], except when C is transferred from a green host to a neighboring mycotrophic, achlorophyllous plant [14, 23]. The AM symbiosis is particularly important for their host plant acquisition of P, zinc and copper from soil because those nutrients only have a limited mobility in most soils and AMF hyphae are well suited to reach those nutrients beyond the root depletion zone [1, 64, 92]. The AMF hyphae, however, have generally much lesser importance in directly improving N nutrition of their hosts from mineral N sources ([51] and reference therein). This may appear surprising because the AMF obviously possess the metabolic capacity to take up inorganic N forms from soil solution and transport the N to their host plants [27, 34, 39]. However, the mobility of inorganic N forms in soil is mostly not limiting the N uptake by the plants [86]—probably with the exception of N being present predominantly as NH4+ ions in clayey, highly organic, and/or calcareous, alkaline soils. Under such conditions, the mobility of ammonium ions in soil is low and, consequently, significant improvements of plant N acquisition are sometimes, though not always, recorded due to AM symbiosis establishment [4, 67, 85].

Yet, the AM symbiosis can have important indirect effects on plant N nutrition during which the mycorrhizal benefits and costs may vary according to the environmental context [22, 60, 69]. Particularly, under low mineral N availability in the soil, a competition for soil N between the plant and the AMF has been documented, resulting in less N being taken up from the N-deficient soil by mycorrhizal as compared to the non-mycorrhizal plants [99]. Only when the N demand of the fungus was satisfied, the mycorrhizal growth- and P-uptake responses became positive [54, 99]. This is mainly because the N demand of AMF hyphae can be substantial, as the N concentration in the AMF hyphae may (at least for some AMF taxa) reach well over 5% [53]. On the other hand, in legumes supporting symbiotic dinitrogen fixation, AMF-mediated P supply could have significant positive feedback on the efficiency of atmospheric dinitrogen fixation [100]. Direct transfer of N from plant to plant via common mycorrhizal networks is remaining another intriguing yet largely unconfirmed hypothesis. It is namely difficult to separate processes like biotrophic (AMF hyphae-mediated) transfer of N from transfer via root exudates [61] or from recycling of nutrients contained in necromass—plant or fungal [29, 68]. Uptake of N from such different sources can only be unequivocally traced in very simplified ecosystems such as monoxenic cultures [74] or in reduced soil diversity experiments [130]. Using such simplified experimental systems, and benefitting from the use of isotopically labeled compounds, uptake of simple amino acids by AMF hyphae has previously been tested [46, 80]. Based on that research, there is thus far no experimental evidence for any substantial and quantitatively important acquisition of N by mycorrhizal roots via AMF hyphae from such simple organic sources, in the absence of other microbes. On the other hand, there is some limited and partly equivocal evidence from experiments employing quantum dot technology indicating that organic N fragments could potentially be taken up by AMF hyphae and that uptake of N in the form of certain amino acids is enhanced in mycorrhizal as compared to non-mycorrhizal roots [133, 134].

Nevertheless, there are specific situations where the AM symbiosis can indeed play a major and direct role in soil–plant N cycling—mainly, if the N is present in soil predominantly in organic forms (e.g., plant litter, manure, compost or organic wastes). This particular scenario will be handled in detail below.

Organic nitrogen in soil and AM symbiosis

The development of AMF in soil—both hyphal proliferation and spore formation—is often stimulated by organic amendments, particularly by those with a significant N content [16, 43, 101]. For example, farmyard manure, plant litter, yeast biomass, chitin, nucleic acids or proteins, when added to soil/growth substrate, have previously been shown to induce short-term increases in AMF hyphal and/or spore densities (Table 1 and references therein). Such effects have not been observed for compounds like cellulose or phytic acid, which contain no organically bound N, however [16, 44, 51]. Such a stimulation of AMF development could relate to release of nutrients (particularly of N in form of ammonium) from the soil amendments through mineralization, or to locally changed abiotic or biotic soil properties, or both [15, 43, 96]. Interestingly, addition of mineral nutrients does usually induce much weaker effects on AMF hyphal proliferation as compared to the organic amendments [15].

The AMF possess a particularly weak exo-enzymatic repertoire [124] as compared to other (ecto-, ericoid and orchid) mycorrhizal and saprotrophic fungi [76, 87, 118]. Thus, the AMF are very unlikely to mineralize soil organic nutrients effectively on their own, although some exo-phosphatase activity has previously been detected in the AMF hyphae [71, 72, 77]. Therefore, it is very likely that to effectively acquire mineral nutrients (be it P or N) bound either in the organic amendments or in the soil organic matter (SOM) itself, the AMF must rely on mineralization of such resources carried out by other saprotrophic or hypersymbiotic microbes [62, 96, 123]. The distinction between saprotrophic and hypersymbiotic microbes in this regards is the origin of C the microbes live on—either from the SOM or from the AMF hyphae, respectively. A nice example of a tight cooperation between the AMF hyphae and a soil bacterium Rahnella aquatilis with regards to organic P (phytate) mineralization has recently been described by Zhang et al. [136]. Although mineralization of organic N is at least equally important process as organic P mineralization, and microbial communities in AMF hyphosphere amended with organic N have been analyzed previously [16, 43, 96], there is as yet no specific information about the identity of primary organic N decomposers teaming directly with the AMF hyphae.

Besides the primary decomposers, which catalyze the liberation of small (organic or inorganic) molecules that could then be taken up by the microbial cells, it seems that for utilization by AMF hyphae of N supplied in organic forms, microbial grazers (protists and/or nematodes) play a particularly important role ([15] and references therein). This is because the grazers excrete, for stoichiometric reasons, large amounts of N they take in with their prey as free ammonium ions back to the soil solution [126]. From the soil solution, this N can then be readily taken up by the AMF hyphae to cover their own N demand or to transport it to the host plant [15, 68, 123]. The central role of free ammonium ions in the utilization of organic N by AMF hyphae has been postulated in several studies (e.g., [15, 117]). Further, ammonium is the preferred mineral form of N for uptake by the AMF hyphae [119]. And, interestingly enough, there is no unequivocal evidence as yet for the extraradical AMF hyphae to be able to directly and in significant amounts acquire small organic N molecules such as amino acids, peptides, chitin oligomers, or nucleotides from the soil solution ([46, 59, 80]; but see [134]).

Chitin—a relevant organic N source for the AMF?

Chitin is the second (after cellulose) most abundant polymer in nature [122], and, unlike the cellulose, it is rich in N (it contains > 6% N by weight). It is present in soil micro- and meso-fauna and in microorganisms, including many insects, crustaceans, and fungi, respectively. Large amounts of chitin are, thus, both produced and recycled in the soils [25, 29]. Addition of crab-shell chitin to plant cultivation substrate has earlier been shown to strongly promote sporulation of several AMF species [43], a trick that is now widely been used in commercial production of AMF inocula to enhance their quality. More recently, it has been shown by direct isotopic 15N-labeling that a large fraction (> 20%) of the organic N supplied as chitin into a pot zone accessible solely to AMF hyphae but not roots has been transferred to the plants within as little as 5 weeks [15]. Further examples of experimentally measured N transfer rates from organic N sources to plants via AMF hyphae are provided in Table 1. Such efficient release and transport of N as quoted above would require very fast chitin mineralization, for example, by specialized soil prokaryotes and/or fungi [12, 94] and further processing via the soil microbial loop involving microbial grazers [15]. It is noteworthy that chitinolytic microorganisms usually degrade chitin to oligomers that are directly taken to their cells via specialized transporters, referred to (at least in the prokaryotic world) as chitoporins ([12] and references therein). Specialized or more generic transmembrane transporters facilitate uptake of N-acetylglucosamine (a chitin monomer) to eukaryotic cells [3, 107]. Interestingly, genes responsible for N-acetylglucosamine transport across membrane and its further metabolism have also been described from AM fungus Rhizophagus irregularis [75], yet they have only been documented to be active in the intraradical mycelium, possibly recycling organic N from collapsing arbuscules. Regardless of the possible role of N-acetylglucosamine (or other soluble products of chitinolysis) in N nutrition of various microorganisms, chitin oligomers and their derivatives (such as lipo-chitooligosaccharides) also serve as signals to recognize pathogens or symbionts in the plant and microbial worlds [5, 93, 108]. To recognize such signals, specialized receptors and signaling cascades have developed in plants [5, 38], but these are unlikely to be involved in mass chito-oligomer uptake by cells for nutritional purposes.

Metabolic capacity to take up soluble organic N compounds derived from chitinolysis may give the microbes the priority of utilizing the N from chitin over other soil opportunists. Yet, regardless the priority in organic N uptake, once such microbes are digested by bacterial/fungal grazers, their N eventually returns to the soil ammonium pool. The AMF hyphal proliferation in chitin-enriched patches [15] could then be explained by locally elevated ammonium concentration or by the presence of specific microbiome in the chitin-amended patches, with countless of more or less specific interactions between individual microbes and the AMF hyphae [41, 63]. Among such interactions, we mention here just two examples: first, a competition for free ammonium ions in soil solution between AMF hyphae and soil ammonia oxidizers has recently been documented [15]. And second, stimulation of nosZ gene-carrying bacterial clades (e.g., Gemmatimonadetes and Deltaproteobacteria) by AMF hyphae has been suggested to explain overall reduction of soil N2O emissions from AMF-colonized N2O hotspots [13, 117].

There is also an interesting question remaining to be answered as to whether the AMF hyphae could directly be implicated in chitin mineralization and consequent N release from its polymeric structure. If we accept that the AMF have chitin in their cell walls [35], hyphal elongation (apical growth) requires a suite of membrane-bound and exo-cellular enzymes including chitin synthases and chitinases [37, 104, 109]. Having such enzymes in their repertoire, the AMF may (at least theoretically) be well capable of releasing N locked up in the exogenous chitin without involvement of other (chitinolytic) microorganisms. Whether the AMF generally utilize the N from exogenous chitin without involvement of other microorganisms and whether the rate of N release from chitin and its uptake into the hyphae is of any significance for the AMF is still remaining to be addressed experimentally, though.

Conclusions and future research directions

In spite of a significant progress in understanding of importance of organic N sources for AMF hyphal development and N acquisition [59], there are still a number of open questions to be answered by future research.

First, the effects should specifically be addressed of the chemical identity of model N compounds on AMF and the soil N cycling. There have namely been different organic N sources including complex substrates such as plant litter or yeast biomass tested in previous experiments ([16, 50, 52, 103]; see also Table 1), which might have stimulated different microbial groups and/or mineralization pathways [16]. Future experiments should, thus, concentrate on a few, chemically well-defined compounds to achieve deeper understanding of mechanisms and processes behind utilization of those model organic N sources by the AMF and their associated plants. Chitin may be a good candidate for such experimentation because of its chemical uniformity and simplicity, although, admittedly, complex plant litter [81] or even entire roots [127] might well be even more relevant from a broader ecosystem-wise point of view.

Second, unambiguous identification should be achieved of the players involved in the release/uptake of N from the organic N sources, including their energy (and C) sources. Experimental approaches to achieve this include stable isotope labeling of the organic soil amendments coupled with density-gradient fractionation of nucleic acid and subsequent next generation sequencing (NGS) or with signature phospholipid fatty acid analyses, approaches known as stable isotope probing (SIP) experiments [24]. Studying soil meta-transcriptomes and genetic makeup of microorganisms identified in the SIP experiments, along with metabolic and co-occurrence network analyses, should allow reconstructing the entire organic N utilization pathway [8, 91]. Such experiments should carefully be designed to cover all relevant time points in the organic N mineralization and downstream N utilization within the complex microbial communities to seize their temporal dynamics aspect. The unprecedented depth of current NGS methods should be utilized, including less prominently studied, but functionally equally important, microbial groups such as soil protists and nematodes [79, 106, 135].

Third, fully quantitative insights should be provided into the fluxes of N and C in soil. The usage of stable isotopes allows addressing whether it was specifically the N that was cleaved off the organic moieties without further degrading/utilizing the C backbone structures of the organic soil amendments. Or, alternatively, whether mineralization of organic N sources such as chitin is only or preferentially happening upon strong microbial demand for C/energy. In the latter scenario, liberation of N contained in the organic molecules would effectively happen only as a by-product of mineralization of the organic N source primarily because of microbial C requirements. There is evidence for both pathways being operational in the microbial world—with deacetylation/deamination processes being more active if bacteria are N but not C limited, and full depolymerization/mineralization of chitin being predominant under conditions when chitin is the major C source [12]. Specific utilization of organic N but not C from the SOM (a process leading eventually to enhanced C sequestration) is also described for ectomycorrhizal fungi [11, 84] and also suggested by some earlier data from AMF systems [127]. When the entire organic N source including the C was taken up by the microbes, it would result in removal and not in stabilization/sequestration of the SOM, which is consistent with some other observations, showing co-incidental disappearance of both N and C added to the soil as organic amendment [19, 128]. Organic N mineralization in soil could also be catalyzed by different microbial groups, depending on resource stoichiometry such as relative C and N availabilities. This means that bulk processes such as organic N mineralization cannot always be unequivocally linked to the individual microbial groups—there obviously is a continuum in both [78].

Fourth, detailed and spatially explicit insight is needed into the microbial world, which would allow directly linking the players to individual processes in soil N cycling. Spatial arrangement of both the microbes and the stable isotopes could be visualized by advanced approaches such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and by nanoscale secondary ion mass spectrometry (NanoSIMs), respectively [73, 90, 96, 125]. Further, the activity of the different enzymes potentially involved in chitin or other N sources mineralization (e.g., chitinases, deaminases, proteinases) can be visualized in a spatially discrete manner by zymography [113].

Fifth, the ultimate proof is required of the causal link between the functionality and the structure of processes. Reconstructing simple model ecosystems from individual microorganisms or from functional guilds [130] shall provide the direct experimental evidence for the processes suggested by observations of complex systems, e.g., involvement of protists in increasing N availability from the organic N sources for the AMF hyphae through so-called soil microbial loop (e.g., [15]).

Last but not least, in each and every stage of the research outlined above, it is always important to think about how the results relate to our ultimate goal—which is to utilize the new knowledge for the sake of global sustainability and human welfare. Applied research should translate the basic findings (for example, those related to efficiency of organic N recycling in soils) to improved and more environmentally sustainable agricultural practices. Improving efficiency and sustainability of agricultural production is urgently needed, while it is equally important not to accept any productivity decreases—an uneasy task to fulfill, yet vitally important to attain in order to ensure enough food for every human being on the planet—now and in the future.

Abbreviations

- AM:

-

arbuscular mycorrhizal

- AMF:

-

arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus/fungi

- C:

-

carbon

- FISH:

-

fluorescence in situ hybridization

- N:

-

nitrogen

- NanoSIMs:

-

nanoscale secondary ion mass spectrometry

- NGS:

-

next generation sequencing

- P:

-

phosphorus

- SIP:

-

stable isotope probing

- SOM:

-

soil organic matter

References

Allen MF. Mycorrhizal fungi: highways for water and nutrients in arid soils. Vadose Zone J. 2007;6:291–7.

Allen JW, Shachar-Hill Y. Sulfur transfer through an arbuscular mycorrhiza. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:549–60. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.108.129866.

Alvarez FJ, Konopka JB. Identification of an N-acetylglucosamine transporter that mediates hyphal induction in Candida albicans. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:965–75.

Ames RN, Reid CPP, Porter LK, Cambardella C. Hyphal uptake and transport of nitrogen from 2 15N-labeled sources by Glomus mosseae, a vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus. New Phytol. 1983;95:381–96.

Antolin-Llovera M, Petutsching EK, Ried MK, Lipka V, Nurnberger T, Robatzek S, Parniske M. Knowing your friends and foes—plant receptor-like kinases as initiators of symbiosis or defence. New Phytol. 2014;204:791–802.

Atul-Nayyar A, Hamel C, Hanson K, Germida J. The arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis links N mineralization to plant demand. Mycorrhiza. 2009;19:239–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-008-0215-0.

Babikova Z, Johnson D, Bruce T, Pickett J, Gilbert L. Underground allies: how and why do mycelial networks help plants defend themselves? BioEssays. 2014;36:21–6.

Banerjee S, Kirkby CA, Schmutter D, Bissett A, Kirkegaard JA, Richardson AE. Network analysis reveals functional redundancy and keystone taxa amongst bacterial and fungal communities during organic matter decomposition in an arable soil. Soil Biol Biochem. 2016;97:188–98.

Barrett G, Campbell CD, Fitter AH, Hodge A. The arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Glomus hoi can capture and transfer nitrogen from organic patches to its associated host plant at low temperature. Appl Soil Ecol. 2011;48:102–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2011.02.002.

Barrett G, Campbell CD, Hodge A. The direct response of the external mycelium of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi to temperature and the implications for nutrient transfer. Soil Biol Biochem. 2014;78:109–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.07.025.

Baskaran P, Hyvonen R, Berglund SL, Clemmensen KE, Agren GI, Lindahl BD, Manzoni S. Modelling the influence of ectomycorrhizal decomposition on plant nutrition and soil carbon sequestration in boreal forest ecosystems. New Phytol. 2017;213:1452–65.

Beier S, Bertilsson S. Bacterial chitin degradation-mechanisms and ecophysiological strategies. Front Microbiol. 2013;4:149.

Bender SF, Plantenga F, Neftel A, Jocher M, Oberholzer HR, Kohl L, Giles M, Daniell TJ, van der Heijden MGA. Symbiotic relationships between soil fungi and plants reduce N2O emissions from soil. ISME J. 2014;8:1336–45.

Bidartondo MI, Redecker D, Hijri I, Wiemken A, Bruns TD, Dominguez L, Sersic A, Leake JR, Read DJ. Epiparasitic plants specialized on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Nature. 2002;419:389–92.

Bukovská P, Bonkowski M, Konvalinková T, Beskid O, Hujslová M, Püschel D, Řezáčová V, Gutierrez-Nunez MS, Gryndler M, Jansa J. Utilization of organic nitrogen by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi—is there a specific role for protists and ammonia oxidizers? Mycorrhiza. 2018;28:269–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-018-0825-0.

Bukovská P, Gryndler M, Gryndlerová H, Püschel D, Jansa J. Organic nitrogen-driven stimulation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal hyphae correlates with abundance of ammonia oxidizers. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:711. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00711.

Canfield DE, Glazer AN, Falkowski PG. The evolution and future of Earth’s nitrogen cycle. Science. 2010;330:192–6.

Cassman KG. Ecological intensification of cereal production systems: yield potential, soil quality, and precision agriculture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5952–9.

Cheng L, Booker FL, Tu C, Burkey KO, Zhou LS, Shew HD, Rufty TW, Hu SJ. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi increase organic carbon decomposition under elevated CO2. Science. 2012;337:1084–7.

Cliquet JB, Murray PJ, Boucaud J. Effect of the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Glomus fasciculatum on the uptake of amino nitrogen by Lolium perenne. New Phytol. 1997;137:345–9. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.1997.00810.x.

Cordell D, Drangert JO, White S. The story of phosphorus: global food security and food for thought. Glob Environ Change. 2009;19:292–305.

Corrêa A, Cruz C, Ferrol N. Nitrogen and carbon/nitrogen dynamics in arbuscular mycorrhiza: the great unknown. Mycorrhiza. 2015;25:499–515.

Courty PE, Walder F, Boller T, Ineichen K, Wiemken A, Rousteau A, Selosse MA. Carbon and nitrogen metabolism in mycorrhizal networks and mycoheterotrophic plants of tropical forests: a stable isotope analysis. Plant Physiol. 2011;156:952–61.

Drigo B, Pijl AS, Duyts H, Kielak A, Gamper HA, Houtekamer MJ, Boschker HTS, Bodelier PLE, Whiteley AS, Van Veen JA, Kowalchuk GA. Shifting carbon flow from roots into associated microbial communities in response to elevated atmospheric CO2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:10938–42. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1005874107.

Ekblad A, Wallander H, Godbold DL, Cruz C, Johnson D, Baldrian P, Bjork RG, Epron D, Kieliszewska-Rokicka B, Kjøller R, Kraigher H, Matzner E, Neumann J, Plassard C. The production and turnover of extramatrical mycelium of ectomycorrhizal fungi in forest soils: role in carbon cycling. Plant Soil. 2013;366:1–27.

Erisman JW, Sutton MA, Galloway J, Klimont Z, Winiwarter W. How a century of ammonia synthesis changed the world. Nat Geosci. 2008;1:636–9.

Fellbaum CR, Gachomo EW, Beesetty Y, Choudhari S, Strahan GD, Pfeffer PE, Kiers ET, Bücking H. Carbon availability triggers fungal nitrogen uptake and transport in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:2666–71. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1118650109.

Fellbaum CR, Mensah JA, Cloos AJ, Strahan GE, Pfeffer PE, Kiers ET, Bücking H. Fungal nutrient allocation in common mycorrhizal networks is regulated by the carbon source strength of individual host plants. New Phytol. 2014;203:646–56.

Fernandez CW, Koide RT. The role of chitin in the decomposition of ectomycorrhizal fungal litter. Ecology. 2012;93:24–8.

Fitter AH. What is the link between carbon and phosphorus fluxes in arbuscular mycorrhizas? A null hypothesis for symbiotic function. New Phytol. 2006;172:3–6.

Fitter AH, Graves JD, Watkins NK, Robinson D, Scrimgeour C. Carbon transfer between plants and its control in networks of arbuscular mycorrhizas. Funct Ecol. 1998;12:406–12.

Frossard E, Bünemann E, Jansa J, Oberson A, Feller C. Concepts and practices of nutrient management in agro-ecosystems: can we draw lessons from history to design future sustainable agricultural production systems? Die Bodenkultur. 2009;60:43–60.

Galloway JN, Townsend AR, Erisman JW, Bekunda M, Cai ZC, Freney JR, Martinelli LA, Seitzinger SP, Sutton MA. Transformation of the nitrogen cycle: recent trends, questions, and potential solutions. Science. 2008;320:889–92.

Garcia K, Doidy J, Zimmermann SD, Wipf D, Courty PE. Take a trip through the plant and fungal transportome of mycorrhiza. Trends Plant Sci. 2016;21:937–50.

Gianinazzi-Pearson V, Lemoine MC, Arnould C, Gollotte A, Morton JB. Localization of β-(1-3) glucans in spore and hyphal walls of fungi in the Glomales. Mycologia. 1994;86:478–85.

Godfray HCJ, Crute IR, Haddad L, Lawrence D, Muir JF, Nisbett N, Pretty J, Robinson S, Toulmin C, Whiteley R. The future of the global food system. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2010;365:2769–77.

Gooday GW, Zhu WY, Odonnell RW. What are the roles of chitinases in the growing fungus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;100:387–91.

Gough C, Cullimore J. Lipo-chitooligosaccharide signalling in endosymbiotic plant-microbe interactions. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2011;24:867–78.

Govindarajulu M, Pfeffer PE, Jin HR, Abubaker J, Douds DD, Allen JW, Bücking H, Lammers PJ, Shachar-Hill Y. Nitrogen transfer in the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Nature. 2005;435:819–23.

Gregory PJ, Ingram JSI, Brklacich M. Climate change and food security. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2005;360:2139–48.

Gryndler M, Hršelová H, Stříteská D. Effect of soil bacteria on hyphal growth of the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Glomus claroideum. Folia Microbiol. 2000;45:545–51.

Gryndler M, Hršelová H, Sudová R, Gryndlerová H, Řezáčová V, Merhautová V. Hyphal growth and mycorrhiza formation by the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Glomus claroideum BEG 23 is stimulated by humic substances. Mycorrhiza. 2005;15:483–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-005-0352-7.

Gryndler M, Jansa J, Hršelová H, Chvátalová I, Vosátka M. Chitin stimulates development and sporulation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Appl Soil Ecol. 2003;22:283–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0929-1393(02)00154-3.

Gryndler M, Vosátka M, Hršelová H, Chvátalová I, Jansa J. Interaction between arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and cellulose in growth substrate. Appl Soil Ecol. 2002;19:279–88.

Hawkins HJ, George E. Effect of plant nitrogen status on the contribution of arbuscular mycorrhizal hyphae to plant nitrogen uptake. Physiol Plant. 1999;105:694–700. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1026500810385.

Hawkins HJ, Johansen A, George E. Uptake and transport of organic and inorganic nitrogen by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Plant Soil. 2000;226:275–85.

Hillier J, Hawes C, Squire G, Hilton A, Wale S, Smith P. The carbon footprints of food crop production. Int J Agric Sustain. 2009;7:107–18.

Hodge A. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi influence decomposition of, but not plant nutrient capture from, glycine patches in soil. New Phytol. 2001;151:725–34. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0028-646x.2001.00200.x.

Hodge A. Plant nitrogen capture from organic matter as affected by spatial dispersion, interspecific competition and mycorrhizal colonization. New Phytol. 2003;157:303–14. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00662.x.

Hodge A. Interactions between arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and organic material substrates. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2014;89:47–99.

Hodge A. Accessibility of inorganic and organic nutrients for mycorrhizas. In: Johnson NC, Gehring C, Jansa J, editors. Mycorrhizal mediation of soils. Fertility, structure, and carbon storage. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2017. p. 129–48.

Hodge A, Campbell CD, Fitter AH. An arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus accelerates decomposition and acquires nitrogen directly from organic material. Nature. 2001;413:297–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/35095041.

Hodge A, Fitter AH. Substantial nitrogen acquisition by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi from organic material has implications for N cycling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:13754–9.

Hodge A, Helgason T, Fitter AH. Nutritional ecology of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Fungal Ecol. 2010;4:267–73.

Hodge A, Robinson D, Fitter AH. An arbuscular mycorrhizal inoculum enhances root proliferation in, but not nitrogen capture from, nutrient-rich patches in soil. New Phytol. 2000;145:575–84. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.2000.00602.x.

Hodge A, Stewart J, Robinson D, Griffiths BS, Fitter AH. Root proliferation, soil fauna and plant nitrogen capture from nutrient-rich patches in soil. New Phytol. 1998;139:479–94. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.1998.00216.x.

Hodge A, Robinson D, Griffiths BS, Fitter AH. Why plants bother: root proliferation results in increased nitrogen capture from an organic patch when two grasses compete. Plant Cell Environ. 1999;22:811–20. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3040.1999.00454.x.

Hodge A, Stewart J, Robinson D, Griffiths BS, Fitter AH. Spatial and physical heterogeneity of N supply from soil does not influence N capture by two grass species. Funct Ecol. 2000;14:645–53. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2435.2000.t01-1-00470.x.

Hodge A, Storer K. Arbuscular mycorrhiza and nitrogen: implications for individual plants through to ecosystems. Plant Soil. 2015;386:1–19.

Hoeksema JD, Bruna EM. Context-dependent outcomes of mutualistic interactions. In: Bronstein JL, editor. Mutualism. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015. p. 181–202.

Jalonen R, Nygren P, Sierra J. Transfer of nitrogen from a tropical legume tree to an associated fodder grass via root exudation and common mycelial networks. Plant Cell Environ. 2009;32:1366–76.

Jansa J, Bukovská P, Gryndler M. Mycorrhizal hyphae as ecological niche for highly specialized hypersymbionts—or just soil free-riders? Front Plant Sci. 2013;4:134.

Jansa J, Gryndler M. Biotic environment of the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in soil. In: Koltai H, Kapulnik Y, editors. Arbuscular mycorrhizas: physiology and function. Heidelberg: Springer; 2010. p. 209–36.

Jansa J, Mozafar A, Frossard E. Long-distance transport of P and Zn through the hyphae of an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus in symbiosis with maize. Agronomie. 2003;23:481–8.

Johansen A, Jakobsen I, Jensen ES. Hyphal transport of 15N-labeled nitrogen by a vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus and its effect on depletion of inorganic soil N. New Phytol. 1992;122:281–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00336518.

Johansen A, Jakobsen I, Jensen ES. Hyphal transport by a vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus of N applied to the soil as ammonium or nitrate. Biol Fert Soils. 1993;16:66–70.

Johansen A, Jakobsen I, Jensen ES. Hyphal N transport by vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus associated with cucumber grown at three nitrogen levels. Plant Soil. 1994;160:1–9. https://doi.org/10.2307/1937216.

Johansen A, Jensen ES. Transfer of N and P from intact or decomposing roots of pea to barley interconnected by an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus. Soil Biol Biochem. 1996;28:73–81.

Johnson NC. Resource stoichiometry elucidates the structure and function of arbuscular mycorrhizas across scales. New Phytol. 2010;185:631–47.

Johnson JMF, Franzluebbers AJ, Weyers SL, Reicosky DC. Agricultural opportunities to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions. Environ Pollut. 2007;150:107–24.

Joner EJ, van Aarle IM, Vosátka M. Phosphatase activity of extra-radical arbuscular mycorrhizal hyphae: a review. Plant Soil. 2000;226:199–210.

Joner EJ, Ravnskov S, Jakobsen I. Arbuscular mycorrhizal phosphate transport under monoxenic conditions using radio-labelled inorganic and organic phosphate. Biotechnol Lett. 2000;22:1705–8.

Kaiser C, Kilburn MR, Clode PL, Fuchslueger L, Koranda M, Cliff JB, Solaiman ZM, Murphy DV. Exploring the transfer of recent plant photosynthates to soil microbes: mycorrhizal pathway vs direct root exudation. New Phytol. 2015;205:1537–51.

Kiers ET, Duhamel M, Beesetty Y, Mensah JA, Franken O, Verbruggen E, Fellbaum CR, Kowalchuk GA, Hart MM, Bago A, Palmer TM, West SA, Vandenkoornhuyse P, Jansa J, Bücking H. Reciprocal rewards stabilize cooperation in the mycorrhizal symbiosis. Science. 2011;333:880–2.

Kobae Y, Kawachi M, Saito K, Kikuchi Y, Ezawa T, Maeshima M, Hata S, Fujiwara T. Up-regulation of genes involved in N-acetylglucosamine uptake and metabolism suggests a recycling mode of chitin in intraradical mycelium of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Mycorrhiza. 2015;25:411–7.

Kohler A, Kuo A, Nagy LG, Morin E, Barry KW, Buscot F, Canback B, Choi C, Cichocki N, Clum A, Colpaert J, Copeland A, Costa MD, Dore J, Floudas D, Gay G, Girlanda M, Henrissat B, Herrmann S, Hess J, Hogberg N, Johansson T, Khouja HR, LaButti K, Lahrmann U, Levasseur A, Lindquist EA, Lipzen A, Marmeisse R, Martino E, Murat C, Ngan CY, Nehls U, Plett JM, Pringle A, Ohm RA, Perotto S, Peter M, Riley R, Rineau F, Ruytinx J, Salamov A, Shah F, Sun H, Tarkka M, Tritt A, Veneault-Fourrey C, Zuccaro A, Tunlid A, Grigoriev IV, Hibbett DS, Martin F, Mycorrhizal Genomics Initiative Consortium. Convergent losses of decay mechanisms and rapid turnover of symbiosis genes in mycorrhizal mutualists. Nature Genet. 2015;47:410–5.

Koide RT, Kabir Z. Extraradical hyphae of the mycorrhizal fungus Glomus intraradices can hydrolyse organic phosphate. New Phytol. 2000;148:511–7.

Koranda M, Kaiser C, Fuchslueger L, Kitzler B, Sessitsch A, Zechmeister-Boltenstern S, Richter A. Fungal and bacterial utilization of organic substrates depends on substrate complexity and N availability. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2014;87:142–52.

Lear G, Dickie I, Banks J, Boyer S, Buckley HL, Buckley TR, Cruickshank R, Dopheide A, Handley KM, Hermans S, Kamke J, Lee CK, MacDiarmid R, Morales SE, Orlovich DA, Smissen R, Wood J, Holdaway R. Methods for the extraction, storage, amplification and sequencing of DNA from environmental samples. N Z J Ecol. 2018;42:10.

Leigh J, Fitter AH, Hodge A. Growth and symbiotic effectiveness of an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus in organic matter in competition with soil bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2011;76:428–38.

Leigh J, Hodge A, Fitter AH. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi can transfer substantial amounts of nitrogen to their host plant from organic material. New Phytol. 2009;181:199–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02630.x.

Lendenmann M, Thonar C, Barnard RL, Salmon Y, Werner RA, Frossard E, Jansa J. Symbiont identity matters: carbon and phosphorus fluxes between Medicago truncatula and different arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Mycorrhiza. 2011;21:689–702.

Lenoir I, Fontaine J, Sahraoui ALH. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal responses to abiotic stresses: a review. Phytochemistry. 2016;123:4–15.

Lindahl BD, Tunlid A. Ectomycorrhizal fungi—potential organic matter decomposers, yet not saprotrophs. New Phytol. 2015;205:1443–7.

Mäder P, Vierheilig H, Streitwolf-Engel R, Boller T, Frey B, Christie P, Wiemken A. Transport of 15N from a soil compartment separated by a polytetrafluoroethylene membrane to plant roots via the hyphae of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol. 2000;146:155–61. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.2000.00615.x.

Marschner H. Mineral nutrition of higher plants. London: Academic Press; 1995.

Martino E, Morin E, Grelet GA, Kuo A, Kohler A, Daghino S, Barry KW, Cichocki N, Clum A, Dockter RB, Hainaut M, Kuo RC, LaButti K, Lindahl BD, Lindquist EA, Lipzen A, Khouja HR, Magnuson J, Murat C, Ohm RA, Singer SW, Spatafora JW, Wang M, Veneault-Fourrey C, Henrissat B, Grigoriev IV, Martin FM, Perotto S. Comparative genomics and transcriptomics depict ericoid mycorrhizal fungi as versatile saprotrophs and plant mutualists. New Phytol. 2018;217:1213–29.

McDougall R, Kristiansen P, Rader R. Small-scale urban agriculture results in high yields but requires judicious management of inputs to achieve sustainability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:129–34.

McFarland JW, Ruess RW, Kielland K, Pregitzer K, Hendrick R, Allen M. Cross-ecosystem comparisons of in situ plant uptake of amino acid-N and NH4 +. Ecosystems. 2010;13:177–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-009-9309-6.

Mogge B, Loferer C, Agerer R, Hutzler P, Hartmann A. Bacterial community structure and colonization patterns of Fagus sylvatica L-ectomycorrhizospheres as determined by fluorescence in situ hybridization and confocal laser scanning microscopy. Mycorrhiza. 2000;9:271–8.

Morrien E. Understanding soil food web dynamics, how close do we get? Soil Biol Biochem. 2016;102:10–3.

Mosse B. Growth and chemical composition of mycorrhizal and non-mycorrhizal apples. Nature. 1957;179:923–4.

Nadal M, Sawers R, Naseem S, Bassin B, Kulicke C, Sharman A, An G, An K, Ahern KR, Romag A, Brutnell TP, Gutjahr C, Geldner N, Roux C, Martinoia E, Konopka JB, Paszkowski U. An N-acetylglucosamine transporter required for arbuscular mycorrhizal symbioses in rice and maize. Nat Plants. 2017;3:17073.

Nampally M, Rajulu MBG, Gillet D, Suryanarayanan TS, Moerschbacher BB. A high diversity in chitinolytic and chitosanolytic species and enzymes and their oligomeric products exist in soil with a history of chitin and chitosan exposure. Biomed Res Int. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/857639.

Newsham KK, Fitter AH, Watkinson AR. Multi-functionality and biodiversity in arbuscular mycorrhizas. Trends Ecol Evol. 1995;10:407–11.

Nuccio EE, Hodge A, Pett-Ridge J, Herman DJ, Weber PK, Firestone MK. An arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus significantly modifies the soil bacterial community and nitrogen cycling during litter decomposition. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15:1870–81.

Pearson JN, Jakobsen I. Symbiotic exchange of carbon and phosphorus between cucumber and 3 arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol. 1993;124:481–8.

Pimentel D, Pimentel MH. Food, energy, and society. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2007.

Püschel D, Janoušková M, Hujslová M, Slavíková R, Gryndlerová H, Jansa J. Plant-fungus competition for nitrogen erases mycorrhizal growth benefits of Andropogon gerardii under limited nitrogen supply. Ecol Evol. 2016;6:4332–46.

Püschel D, Janoušková M, Voříšková A, Gryndlerová H, Vosátka M, Jansa J. Arbuscular mycorrhiza stimulates biological nitrogen fixation in two Medicago spp. through improved phosphorus acquisition. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:390.

Quilliam RS, Hodge A, Jones DL. Sporulation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in organic-rich patches following host excision. Appl Soil Ecol. 2010;46:247–50.

Rains KC, Bledsoe CS. Rapid uptake of 15N-ammonium and 13C-15N-glycine by arbuscular and ericoid mycorrhizal plants native to a Northern California coastal pygmy forest. Soil Biol Biochem. 2007;39:1078–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2006.11.019.

Ravnskov S, Larsen J, Olsson PA, Jakobsen I. Effects of various organic compounds growth and phosphorus uptake of an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus. New Phytol. 1999;141:517–24. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.1999.00353.x.

Riquelme M. Tip growth in filamentous fungi: a road trip to the apex. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2013;67:587–609.

Saia S, Benitez E, Garcia-Garrido JM, Settanni L, Amato G, Giambalvo D. The effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on total plant nitrogen uptake and nitrogen recovery from soil organic material. J Agric Sci. 2014;152:370–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/s002185961300004x.

Sapkota R, Nicolaisen M. High-througput sequencing of nematode communities from total soil DNA extractions. BMC Ecol. 2015;15:3.

Scarcelli JJ, Colussi PA, Fabre AL, Boles E, Orlean P, Taron CH. Uptake of radiolabeled GlcNAc into Saccharomyces cerevisiae via native hexose transporters and its in vivo incorporation into GPI precursors in cells expressing heterologous GlcNAc kinase. FEMS Yeast Res. 2012;12:305–16.

Shinya T, Nakagawa T, Kaku H, Shibuya N. Chitin-mediated plant-fungal interactions: catching, hiding and handshaking. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2015;26:64–71.

Schuster M, Martin-Urdiroz M, Higuchi Y, Hacker C, Kilaru S, Gurr SJ, Steinberg G. Co-delivery of cell-wall-forming enzymes in the same vesicle for coordinated fungal cell wall formation. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1:11.

Smil V. Detonator of the population explosion. Nature. 1999;1999(400):415.

Smith SE, Read DJ. Mycorrhizal symbiosis. 3rd ed. Amsterdam: Academic Press; 2008.

Smith FA, Smith SE. What is the significance of the arbuscular mycorrhizal colonisation of many economically important crop plants? Plant Soil. 2011;348:63–79.

Spohn M, Kuzyakov Y. Spatial and temporal dynamics of hotspots of enzyme activity in soil as affected by living and dead roots-a soil zymography analysis. Plant Soil. 2014;379:67–77.

Steffen W, Richardson K, Rockström J, Cornell SE, Fetzer I, Bennett EM, Biggs R, Carpenter SR, de Vries W, de Wit CA, Folke C, Gerten D, Heinke J, Mace GM, Persson LM, Ramanathan V, Reyers B, Sorlin S. Planetary boundaries: guiding human development on a changing planet. Science. 2015;347:1217.

Steffen W, Rockström J, Richardson K, Lenton TM, Folke C, Liverman D, Summerhayes CP, Barnosky AD, Cornell SE, Crucifix M, Donges JF, Fetzer I, Lade SJ, Scheffer M, Winkelmann R, Schellnhuber HJ. Trajectories of the Earth system in the anthropocene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:8252–9.

St. John TV, Coleman DC, Reid CPP. Association of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal hyphae with soil organic particles. Ecology. 1983;64:957–9. https://doi.org/10.2307/1937216.

Storer K, Coggan A, Ineson P, Hodge A. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi reduce nitrous oxide emissions from N2O hotspots. New Phytol. 2018;220:1285–95.

Talbot JM, Martin F, Kohler A, Henrissat B, Peay KG. Functional guild classification predicts the enzymatic role of fungi in litter and soil biogeochemistry. Soil Biol Biochem. 2015;88:441–56.

Tanaka Y, Yano K. Nitrogen delivery to maize via mycorrhizal hyphae depends on the form of N supplied. Plant Cell Environ. 2005;28:1247–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01360.x.

Tanwar A, Aggarwal A, Parkash V. Sugarcane bagasse: a novel substrate for mass multiplication of Funneliformis mosseae with onion as host. J Cent Eur Agric. 2013;14:1519–28. https://doi.org/10.5513/jcea01/14.4.1386.

Tester M, Langridge P. Breeding technologies to increase crop production in a changing world. Science. 2010;327:818–22.

Tharanathan RN, Kittur FS. Chitin—the undisputed biomolecule of great potential. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2003;43:61–87.

Thirkell TJ, Cameron DD, Hodge A. Resolving the ‘nitrogen paradox’ of arbuscular mycorrhizas: fertilization with organic matter brings considerable benefits for plant nutrition and growth. Plant Cell Environ. 2016;39:1683–90.

Tisserant E, Malbreil M, Kuo A, Kohler A, Symeonidi A, Balestrini R, Charron P, Duensing N, Frey NFD, Gianinazzi-Pearson V, Gilbert LB, Handa Y, Herr JR, Hijri M, Koul R, Kawaguchi M, Krajinski F, Lammers PJ, Masclauxm FG, Murat C, Morin E, Ndikumana S, Pagni M, Petitpierre D, Requena N, Rosikiewicz P, Riley R, Saito K, Clemente HS, Shapiro H, Van Tuinen D, Becard G, Bonfante P, Paszkowski U, Shachar-Hill YY, Tuskan GA, Young PW, Sanders IR, Henrissat B, Rensing SA, Grigoriev IV, Corradi N, Roux C, Martin F. Genome of an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus provides insight into the oldest plant symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:20117–22.

Toljander JF, Artursson V, Paul LR, Jansson JK, Finlay RD. Attachment of different soil bacteria to arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal extraradical hyphae is determined by hyphal vitality and fungal species. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;254:34–40.

Trap J, Bonkowski M, Plassard C, Villenave C, Blanchart E. Ecological importance of soil bacterivores for ecosystem functions. Plant Soil. 2016;398:1–24.

Verbruggen E, Jansa J, Hammer EC, Rillig MC. Do arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi stabilize litter-derived carbon in soil? J Ecol. 2016;104:261–9.

Verbruggen E, Veresoglou SD, Anderson IC, Caruso T, Hammer EC, Kohler J, Rillig MC. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi—short-term liability but long-term benefits for soil carbon storage? New Phytol. 2013;197:366–8.

Vitousek PM, Aber JD, Howarth RW, Likens GE, Matson PA, Schindler DW, Schlesinger WH, Tilman D. Human alteration of the global nitrogen cycle: sources and consequences. Ecol Appl. 1997;7:737–50.

Wagg C, Bender SF, Widmer F, van der Heijden MGA. Soil biodiversity and soil community composition determine ecosystem multifunctionality. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:5266–70.

Walder F, Niemann H, Natarajan M, Lehmann MF, Boller T, Wiemken A. Mycorrhizal networks: common goods of plants shared under unequal terms of trade. Plant Physiol. 2012;159:789–97.

Wang WX, Shi JC, Xie QJ, Jiang YN, Yu N, Wang ET. Nutrient exchange and regulation in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Mol Plant. 2017;10:1147–58.

Whiteside MD, Digman MA, Gratton E, Treseder KK. Organic nitrogen uptake by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in a boreal forest. Soil Biol Biochem. 2012;55:7–13.

Whiteside MD, Garcia MO, Treseder KK. Amino acid uptake in arbuscular mycorrhizal plants. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e47643.

Xiong W, Jousset A, Guo S, Karlsson I, Zhao QY, Wu HS, Kowalchuk GA, Shen QR, Li R, Geisen S. Soil protist communities form a dynamic hub in the soil microbiome. ISME J. 2018;12:634–8.

Zhang L, Feng G, Declerck S. Signal beyond nutrient, fructose, exuded by an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus triggers phytate mineralization by a phosphate solubilizing bacterium. ISME J. 2018;12:2339–51.

Authors’ contributions

JJ and PB devised the structure of the article and both substantially contributed to defining the content and conclusions of the paper. SF reviewed literature on hyphal responses to soil organic amendments, and on nitrogen transfer rates from organic amendments to plants via mycorrhizal hyphae. MR specifically contributed to discussion on interaction of AMF hyphae with bacteria. DP provided insights into plant–mycorrhiza–nitrogen interactions. HH helped defining future goals with respect to molecular analyses of the microbial communities. JJ wrote the first draft of the paper, all authors contributed to subsequent revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This research was carried out in the joint working group of the Institute of Microbiology and the Institute of Botany. The authors are grateful for invitation by Vincenza Cozzolino to contribute this short review to the special issue dedicated to AMF, and for waiving the publication fees. The authors also wish to thank two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments that helped improving the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

We gratefully acknowledge funding of salary expenses of the author team by the Czech Science Foundation (Project ID 18-04892S). Research infrastructure including access to scientific literature resources was further supported by the long-term development programs RVO 61388971, RVO 61389030, and RVO 67985939.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Jansa, J., Forczek, S.T., Rozmoš, M. et al. Arbuscular mycorrhiza and soil organic nitrogen: network of players and interactions. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 6, 10 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40538-019-0147-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40538-019-0147-2