Summary

This article describes the structures and processes involved in healthcare delivery for sepsis, from the prehospital setting until rehabilitation. Quality improvement initiatives in sepsis may reduce both morbidity and mortality. Positive outcomes are more likely when the following steps are optimized: early recognition, severity assessment, prehospital emergency medical system activation when available, early therapy (antimicrobials and hemodynamic optimization), early orientation to an adequate facility (emergency room, operating theater or intensive care unit), in-hospital organ failure resuscitation associated with source control, and finally a comprehensive rehabilitation program. Such a trajectory of care dedicated to sepsis amounts to a chain of survival and rehabilitation for sepsis. Implementation of this chain of survival and rehabilitation for sepsis requires full interconnection between each link. To date, despite regular international recommendations updates, the adherence to sepsis guidelines remains low leading to a considerable burden of the disease. Developing and optimizing such an integrated network could significantly reduce sepsis related mortality and morbidity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Sepsis: a major health issue

Over 50 million patients suffer from sepsis every year [1,2,3]. The incidence of sepsis is approximately 300 per 100,000 inhabitants in the US [4] leading to nearly 270,000 deaths. With an incidence of 41.5 million cases per year leading to 8.2 million deaths in 2017, the burden of sepsis is highest in areas with the lowest soci-demographic index [5, 6]. Sepsis accounts for 20% of deaths worldwide [6]. The World Health organization (WHO) recently recognized sepsis as a leading public health issue. The overall burden of sepsis is increasing [7] due to a more and more aging and frailer population [8,9,10,11]. The short-term economic burden of sepsis is related to hospital costs [6, 12,13,14], while long-term burden is related to the support of subsequent neurocognitive, mental health sequalae or physical disabilities [8, 15, 16]. US cost-of-illness studies indicate that the direct cost of sepsis per patient is nearly 30 000$ [4]. Indirect costs are 3 to 4 times higher, arising mainly from productivity loss [4].

Early recognition and therapy

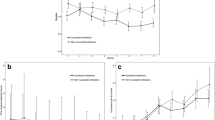

Up to 70% of all cases of sepsis may be identified in the community [17]. Early warning is therefore essential, through the timely initiation of the specific “chain of survival and rehabilitation for sepsis” (Fig. 1) that summarizes a theoretical optimal pathway of care for patients suffering from sepsis.

The chain of survival metaphor, previously used to describe the management of cardiac arrest, captures the complexity of coordinating prehospital emergency medical service (EMS) and hospital care [18]. The concept is straightforward, since prehospital EMS and hospital-based wards are separate entities. In addition, early treatment is associated with a better outcome. However, to initiate the chain of survival, sepsis must first be properly identified. Due to a lack of specific signs and symptoms of sepsis, significant time may be lost before the identification of the condition and therefore for assistance to be requested. Pre-hospital identification of sepsis can be achieved by a witness or a relative, a primary health caregiver or a pre-hospital EMS dispatcher. The role of the prehospital EMS dispatcher, when available, is to determine the severity of the condition and to decide if mandatory to send an emergency medical team. Overall, recognition of the seriousness of the condition, calling for help, and ambulance response time (time interval from reception of the call to the arrival of the emergency medical team at the scene), all increase the delay before prehospital EMS intervention and implementation of an emergent therapy. However, in low and lower middle income countries; there may be no possibility to call for help and/or no ambulance available for hospital transportation. A solution is to improve the recognition of sepsis by relatives and primary caregivers to reduce the delay between sepsis identification and care initiation [19]. Kironji et al. reported that in low and lower-middle income countries, policy makers and researchers should focus their efforts to increase transport availability, caregivers training and access to the out-of-hospital emergency care system [19].

Educational efforts seek to raise awareness of sepsis among the public and professionals [13, 20,21,22,23]. Indeed, recent studies report an incomplete understanding of sepsis among the public [13]. Earlier initiation of the survival chain through education should help to improve patient outcome.

Differences of organization, structure and process of prehospital emergency care for sepsis

In sepsis, patient outcomes are influenced by the process of care, primarily time intervals between the occurrence of sepsis and the delivery of four major interventions: recognition, severity assessment, early therapy, and transfer to the adequate facility [24,25,26]. These steps are included in “bundles of care”, as part of a general strategy recommended to improve the outcome of sepsis [27, 28]. Indeed, patient outcome is determined by the time with which these interventions are successfully delivered [28,29,30,31]. Delays in implementing these interventions are related to the organization of the healthcare system, which varies greatly from country to country, and depends on the available personnel and equipment [32]. For early therapy to be successfully delivered, the management of medical emergencies occurring in the community needs to be optimized. For example, in France, prehospital EMS is based on the SAMU (Urgent Medical Aid Service), a public organization providing a medical response to prehospital emergencies. The central component of SAMU is the dispatching center, where a team of physicians and assistants answer requests for medical assistance through a dedicated phone line [33]. SAMU also manages the SMUR (Mobile Emergency and Resuscitation Service) with mobile intensive care units (mICU), which provides advanced out-of-hospital therapy and may transport the patient. A similar organization to the French original SAMU system nowadays exists in several European countries, but also in low-income countries [24,25,26]. By contrast, in low and lower middle income countries, healthcare resources are scarce [34], leading to increased distance and time to access the appropriate healthcare structure (35–37). To date, no single care delivery model exists in low and lower-middle income countries because of the heterogeneity of the local context. To develop multi-faceted approaches through education, research, and policy should be considered [35].

Prehospital recognition and severity assessment of sepsis

A recent study by Parsons Leigh et al. [13] reported incomplete awareness and understanding of sepsis among the Canadian public, confirming earlier findings [20,21,22,23]. These observations confirm the positive impact of awareness programs performed among primary care and hospital health caregivers, both physicians and nurses, paired with the dissemination of sepsis guidelines and practice bundles allowing the improvement of sepsis diagnosis and the reduction of response care delays [36, 37]. Because most cases of sepsis occur in the community [17], it makes sense to promote awareness of sepsis among the public [38, 39]. General practitioners, nurses, paramedics, prehospital EMS call centers and prehospital emergency medical teams all play a crucial role in the early identification of sepsis [30, 36, 40]. To optimize the management of sepsis, the general practitioner, e.g., often the first witness, or sometimes the nurse, must be able to recognize the severity of the condition and to alert the prehospital EMS call center in order to initiate prehospital care [36]. Consequently, general practitioners play a major role in the overall quality of care of sepsis [41]. Nevertheless, a French study conducted among a sample of general practitioners in the greater Paris area reported a lack of knowledge about sepsis and its management [42]. Severity assessment is also a major issue. A simple, easy tool to assess sepsis severity would therefore be helpful [43]. The Quick SOFA score (qSOFA), which is a simplified SOFA score, was developed and suggested for such a purpose. The qSOFA score is composed of three clinical variables: impaired consciousness, systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≤ 100mmHg and respiratory rate (RR) ≥ 22/min and allows a rapid identification of the most severe forms of sepsis [36]. However, despite its simplicity, qSOFA has a limited sensitivity and is not recommend for sepsis screening [25, 28]. Indeed, sepsis is difficult to diagnose, either at the bedside or listening to a distressed bystander/family member in a call center. Scoring systems have been developed to try to alleviate some of these issues. Unfortunately, qSOFA, MRST, MEWS and PRESEP scores do not reliably predict ICU admission [44]. A reliable score for pre-hospital triage to predict the need for ICU admission is still being sought.

Prehospital emergency care and strategy

Evidence from in hospital studies indicate that early antibiotic therapy and hemodynamic optimization [27] improve outcomes in sepsis [36, 45,46,47,48,49,50,51], especially for the sicker patients [45]. Hemodynamic optimization relies on volume expansion and early norepinephrine infusion [36, 40] with a target mean blood pressure (MBP) of 65 mmHg [30, 52]. A shortened delay to correct hypotension is associated with improved outcomes [53,54,55,56]. Early antibiotic therapy administration is associated with sepsis morbidity and mortality decrease [57, 58]. Current guidelines recommend that antibiotic therapy be started within the first 3 h after sepsis recognition and diagnosis, or even as soon as possible in patients with high likelihood for sepsis [30, 36, 52]. Nevertheless, the right equilibrium, between the potential benefits versus unintended harms of antibiotic therapy [59], needs clarification in order to avoid the unwarranted administration of antibiotics to patients with non-infectious shock [60].

It is expected that an early management strategy will be more effective for the sicker and the frailest patients suffering from sepsis. Since every link in the chain of survival and rehabilitation for sepsis must be considered, we cannot rule out the impact of prehospital EMS organization on outcome [59]. For instance, a direct admission to the intensive care unit contributes to outcome improvement. If evidence-based medicine suggests the beneficial effect of the use of prehospital antibiotic therapy administration for severely ill patients [61,62,63], the impact of the prehospital EMS organization is not established [64].

In France, because 70% of sepsis occur in the community [17], and because prehospital care duration is nearly 60 to 90 min [45], the prehospital period offers a unique opportunity to save lives, by decreasing time-to-antibiotic therapy administration and by decreasing time-to-hemodynamic optimization [65]. Prehospital studies report a positive association between survival and early antibiotic therapy [45] and/or hemodynamic optimization [55, 66], based on early fluid expansion and/or norepinephrine administration [55, 66]. In low and lower-middle income countries, because of the scarcity of emergency care, the distance and time to access appropriate services [67,68,69], the development of emergency care systems is a growing focus. A recent review reported that, beyond the prehospital EMS organization, in low and lower-middle income countries, e.g. mainly in Africa, efforts should focus on improving out-of-hospital emergency care by increasing the availability of transport, caregiver training and patient access to the out-of-hospital emergency care system [19]. In these countries, the development and implementation of these three measures would allow to reduce facilities access delays, as well as allowing earlier antibiotic therapy and/or hemodynamic optimization for septic patients.

Consequently, policy makers, researcher and prehospital caregivers should be aware of their crucial role in early sepsis care [19]. Beyond antibiotic therapy administration and hemodynamic optimization, prehospital caregivers must also ensure that their patient is brought to the adequate facility for comprehensive treatment of sepsis. Controlling the source of sepsis impacts as much the outcome that early antibiotic therapy and hemodynamic optimization. As a result, prehospital caregivers have a key role on deciding in which facility the patient should be admitted. Whilst hemodynamic optimization and antibiotic therapy administration do not require any specific facility, sepsis source control may require a surgical procedure, i.e. peritonitis, which must be taken into account in the prehospital decision to refer the patient. The decision is mainly based on clinical assessment but may be helped by ultrasonography evaluation [70, 71], which is widely available in high-income countries and much less in low- and middle-income countries. Although the involvement of public health and healthcare policies is of paramount importance in determining which pre-hospital medical devices are available, the clinical evaluation remains still available.

In hospital care: emergency department, intensive care unit and ward to rehabilitation

Emergency department

Because septic patients may be primarily admitted to the emergency department, prior ICU admission or due to the lack of immediately available ICU bed, the guidelines for sepsis management should also be apply [28]. However, the ED overcrowding induces an increase in delays of sepsis recognition, severity assessment and treatment initiation, associated with worse outcomes [72]. To offset this, sepsis rapid response teams were developed around the World aiming for the early recognition, diagnosis, severity assessment and treatment of patients suffering from sepsis with a positive impact on patients’ outcome [73]. The early identification based on electronic tools and/or human collaborative approach with interdisciplinary teams improves sepsis bedside huddle and bundle compliance and sepsis outcomes in the emergency department [74], allowing shortening entry in the bundle [75] and decreasing inpatient hospital mortality rates, ED length of stay and hospital length of stay [76]. The activation, composition and rules of sepsis rapid response teams must be thought out and considered on a case-by-case, depending on local resources facility and the needs of the patient to encourage bundle adherence and to hope sepsis outcome improvement [28]. Having a clinical pharmacist on sepsis rapid response teams allows the optimal selection and dosing of initial dose, reduces the time to initiation of antibiotic therapy leading to a reduced inpatient mortality [77].

ICU care

Recently updated guidelines summarize treatments and strategies for managing sepsis [28].

A special attention on antibiotic therapy management is therefore essential. Sepsis leads to alterations of antibiotics PK/PD parameters because of renal clearance alteration [78, 79] and/or extracorporeal supports [80], may reducing blood concentrations leading to failure, or increasing drug toxicity [81, 82], therefore, guidelines recommend optimizing dosing antibiotic therapy based on PK/PD principles and specific drug properties [28]. To avoid the development of antimicrobial resistance, a daily assessment for de-escalation of antimicrobials over using fixed durations of therapy without daily reassessment for de-escalation is recommended [28]. This strategy is associated with short-term mortality improvement [83]. Despite regularly updated recommendations, recent studies reported that despite overall awareness and the importance of early diagnosis and treatment is high among healthcare practitioner, the adherence to sepsis bundles is well below the standard of care leading to important gaps and obstacles in reaching optimal care both in adults and pediatrics [84,85,86], reinforcing the importance of implementing a specific pathway of sepsis care.

The COVID 19 pandemic revealed to the World the inequity of access to an adequately equipped and staffed ICU bed because of the lack of ICU beds [87]. Beyond COVID 19 pandemic, the lack of ICU beds is a daily problem even more in low-income countries where most ICUs are located in large referral hospitals [88] leading to issues for the management of sepsis.

Bundles of care also aim at reducing the adverse effects of critical illness to optimize patient recovery and outcomes [89]. Recent studies report that early rehabilitation, e.g., started within 3 days of ICU admission, was associated with decreased length of stay and improved daily activities after hospital discharge [90, 91], indicating the importance of the early rehabilitation within the ICU. For this purpose, since 2013, the American College of Critical Care Medicine, the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, updated the in-ICU PAD (Pain, Agitation, and Delirium) guidelines to improve critically ill patient management [92]. More recently, the ABCDEF bundle, including many elements of the in-ICU PAD guidelines, was proposed. Briefly, the ABCDEF bundle includes: Assess, Prevent, and Manage Pain (A), Both Spontaneous Awakening Trials (SAT) and Spontaneous Breathing Trials (SBT) (B), Choice of analgesia and sedation (C), Delirium: Assess, Prevent, and Manage (D), Early mobility and Exercise (E), and Family engagement and empowerment (F) in order to early optimize resources utilization [89].

Post ICU care

Among survivors, nearly 50% recover, 30% die within the first year, and 15% suffer from severe persistent impairments [93]. The “post-sepsis syndrome (PSS)” associates physical, medical, cognitive, and mental health sequalae, responsible of long-term morbidity [16]. Prior to PSS, the post-intensive care syndrome (PICS) involves physical, cognitive, and mental impairments occurring during ICU stay or after ICU/hospital discharge, impairing the long-term outcome of survivors [94,95,96,97,98]. In order to combat PSS and PICS, post discharge rehabilitation strategies are effective and associated with a reduced risk of 10-year mortality in sepsis survivors [99]. Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines have a particular focus on continuing rehabilitation to improve functional outcomes during and after ICU discharge [28].

Sepsis is an entity for which the evidence of post-acute care on long-term outcome is supported by evidence-based medicine [99] despite changes over time [9]. The transition point from the ICU to ward is an important stage in the patient medical history. Indeed, it is essential to prepare the transfer to the general ward accurately and correctly to avoid the risk of patient ICU-readmission associated with stress for both patients and relatives [100,101,102,103,104]. ICU transitional care corresponds to the care provided before, during, and after the transfer from ICU to a ward with a minimal disruption and maintaining the optimal care for the patient [105]. To ensure ICU transitional care the discharge procedure need to be safe and structured involving a multidiscipline approach [105] because it corresponds to a period of high vulnerability [106]. To date, post-acute care resources are insufficient to address the needs of sepsis survivors [93] reflected by high rates of adverse outcomes after hospital discharge from high rates of healthcare utilization to hospital readmission and increased mortality [107,108,109]. Best-practice guidelines were developed to guide delivery of post-acute care [93] but suffer from a gap in understanding how to best integrate interventions into the complex post-discharge setting [110, 111].

Maximizing survival rate

The following table summarizes the differences between current practices and optimized practices according to the “chain of survival for sepsis” concept and proposals to achieve its goals (Table 1).

Future studies should determine the impact of implementing an optimized care pathway for sepsis. Without a proper and coordinated implementation of the “chain of survival and rehabilitation for sepsis”, such objectives will not be achieved.

Conclusion

Early access to the “chain of survival and rehabilitation for sepsis” ensures the early initiation of life saving treatments followed by the orientation of the patient to the adequate facility for advanced care. Earlier warning will be ensured by raising awareness of the condition among general practitioners, nurses, paramedics, prehospital caregivers and the general public. Earlier advanced care, based mainly on early antibiotic therapy and hemodynamic optimization, is possible independently of the prehospital emergency medical service organization even for primary health care when no ambulance can be dispatch to the scene. Triaging and admission to the adequate facility are essential for adequate source control. Advanced in hospital care helps overcome organ failure while waiting for the cause of sepsis to be treated. Rehabilitation is essential for survivors to recover an acceptable quality of life.

The ongoing public health challenge appears to be the development of coordinated actions, starting at the prehospital setting right through to rehabilitation, to be delivered as quickly as possible, thereby enhancing successful recovery for patients suffering from sepsis.

Data availability

Not applicable.

References

Fleischmann C, Scherag A, Adhikari NK, Hartog CS, Tsaganos T, Schlattmann P, et al. Assessment of Global Incidence and Mortality of Hospital-treated Sepsis. Current estimates and limitations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(3):259–72.

Gaieski DF, Edwards JM, Kallan MJ, Carr BG. Benchmarking the incidence and mortality of severe sepsis in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(5):1167–74.

Fleischmann-Struzek C, Mellhammar L, Rose N, Cassini A, Rudd KE, Schlattmann P, et al. Incidence and mortality of hospital- and ICU-treated sepsis: results from an updated and expanded systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(8):1552–62.

Burchardi H, Schneider H. Economic aspects of severe sepsis: a review of intensive care unit costs, cost of illness and cost effectiveness of therapy. PharmacoEconomics. 2004;22(12):793–813.

Stephen AH, Montoya RL, Aluisio AR. Sepsis and septic shock in low- and Middle-Income Countries. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2020;21(7):571–8.

Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, Shackelford KA, Tsoi D, Kievlan DR, et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990–2017: analysis for the global burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2020;395(10219):200–11.

Buchman TG, Simpson SQ, Sciarretta KL, Finne KP, Sowers N, Collier M, et al. Sepsis among Medicare beneficiaries: 3. The methods, models, and forecasts of Sepsis, 2012–2018. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(3):302–18.

Paoli CJ, Reynolds MA, Sinha M, Gitlin M, Crouser E. Epidemiology and costs of Sepsis in the United States-An Analysis based on timing of diagnosis and severity level. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(12):1889–97.

Lee JT, Mikkelsen ME, Qi M, Werner RM. Trends in Post-acute Care Use after admissions for Sepsis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(1):118–21.

Tew M, Dalziel K, Thursky K, Krahn M, Abrahamyan L, Morris AM, Clarke P. Excess cost of care associated with sepsis in cancer patients: results from a population-based case-control matched cohort. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(8):e0255107.

The Lancet Healthy L. Care for ageing populations globally. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021;2(4):e180.

Farrah K, McIntyre L, Doig CJ, Talarico R, Taljaard M, Krahn M, et al. Sepsis-Associated Mortality, Resource Use, and Healthcare costs: a propensity-matched cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2021;49(2):215–27.

Parsons Leigh J, Brundin-Mather R, Moss SJ, Nickel A, Parolini A, Walsh D, et al. Public awareness and knowledge of sepsis: a cross-sectional survey of adults in Canada. Crit Care. 2022;26(1):337.

Shankar-Hari M, Rubenfeld GD. Understanding long-term outcomes following Sepsis: implications and challenges. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2016;18(11):37.

Shankar-Hari M, Phillips GS, Levy ML, Seymour CW, Liu VX, Deutschman CS, et al. Developing a new definition and assessing New Clinical Criteria for septic shock: for the Third International Consensus definitions for Sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):775–87.

Mostel Z, Perl A, Marck M, Mehdi SF, Lowell B, Bathija S, et al. Post-sepsis syndrome - an evolving entity that afflicts survivors of sepsis. Mol Med. 2019;26(1):6.

Fay K, Sapiano MRP, Gokhale R, Dantes R, Thompson N, Katz DE, et al. Assessment of Health Care exposures and outcomes in adult patients with Sepsis and septic shock. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e206004.

Cummins RO, Ornato JP, Thies WH, Pepe PE. Improving survival from sudden cardiac arrest: the chain of survival concept. A statement for health professionals from the Advanced Cardiac Life Support Subcommittee and the Emergency Cardiac Care Committee, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1991;83(5):1832–47.

Kironji AG, Hodkinson P, de Ramirez SS, Anest T, Wallis L, Razzak J, et al. Identifying barriers for out of hospital emergency care in low and low-middle income countries: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):291.

Rubulotta FM, Ramsay G, Parker MM, Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Poeze M, et al. An international survey: public awareness and perception of sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(1):167–70.

Eitze S, Fleischmann-Struzek C, Betsch C, Reinhart K. vaccination60 + study g. determinants of sepsis knowledge: a representative survey of the elderly population in Germany. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):273.

Jabaley CS, Blum JM, Groff RF, O’Reilly-Shah VN. Global trends in the awareness of sepsis: insights from search engine data between 2012 and 2017. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):7.

Fiest KM, Krewulak KD, Brundin-Mather R, Leia MP, Fox-Robichaud A, Lamontagne F, et al. Patient, Public, and Healthcare professionals’ Sepsis Awareness, Knowledge, and information seeking behaviors: a scoping review. Crit Care Med. 2022;50(8):1187–97.

Adnet F, Lapostolle F. International EMS systems: France. Resuscitation. 2004;63(1):7–9.

Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, Antonelli M, Coopersmith CM, French C, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(11):1181–247.

Diaconu K, Falconer J, Vidal N, O’May F, Azasi E, Elimian K, et al. Understanding fragility: implications for global health research and practice. Health Policy Plan. 2020;35(2):235–43.

Leisman DE, Doerfler ME, Ward MF, Masick KD, Wie BJ, Gribben JL, et al. Survival benefit and cost savings from compliance with a simplified 3-Hour Sepsis bundle in a series of prospective, multisite, observational cohorts. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(3):395–406.

Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, Antonelli M, Coopersmith CM, French C, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock 2021. Crit Care Med. 2021;49(11):e1063–143.

Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(3):304–77.

Chen AX, Simpson SQ, Pallin DJ. Sepsis guidelines. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(14):1369–71.

Force IST. Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) POSITION STATEMENT: why IDSA did not endorse the surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(10):1631–5.

Bossaert LL. The complexity of comparing different EMS systems–a survey of EMS systems in Europe. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22(1):99–102.

Jouffroy R, Saade A, Carpentier A, Ellouze S, Philippe P, Idialisoa R, et al. Triage of septic patients using qSOFA criteria at the SAMU Regulation: a retrospective analysis. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(1):84–90.

Ouma PO, Maina J, Thuranira PN, Macharia PM, Alegana VA, English M, et al. Access to emergency hospital care provided by the public sector in sub-saharan Africa in 2015: a geocoded inventory and spatial analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(3):e342–50.

Losonczy LI, Papali A, Kivlehan S, Calvello Hynes EJ, Calderon G, Laytin A, et al. White Paper on early critical care services in low resource settings. Ann Glob Health. 2021;87(1):105.

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The Third International Consensus definitions for Sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–10.

Weiss SL, Peters MJ, Alhazzani W, Agus MSD, Flori HR, Inwald DP, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign International guidelines for the Management of Septic Shock and Sepsis-Associated Organ Dysfunction in Children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2020;21(2):e52–106.

Kerrigan SW, Martin-Loeches I. Public awareness of sepsis is still poor: we need to do more. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44(10):1771–3.

Angus DC, Bindman AB. Achieving Diagnostic Excellence for Sepsis. JAMA. 2022;327(2):117–8.

Levy MM, Evans LE, Rhodes A. The surviving Sepsis Campaign Bundle: 2018 update. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(6):997–1000.

Schorr CA, Zanotti S, Dellinger RP. Severe sepsis and septic shock: management and performance improvement. Virulence. 2014;5(1):190–9.

Froment MJR, Carli P, Vivien B. Connaissances et formation des médecins généralistes pour la gestion des états septiques. J Européen Des Urgences et de Réanimation. 2017;30.

Alves B, Jouffroy R. [A central role for the home care nurse in the assessment of the severity of sepsis]. Soins. 2021;66(856):11–3.

Jouffroy R, Saade A, Tourtier JP, Gueye P, Bloch-Laine E, Ecollan P, et al. Skin mottling score and capillary refill time to assess mortality of septic shock since pre-hospital setting. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(4):664–71.

Jouffroy R, Vivien B. Implementation of earlier antibiotic administration in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock in Japan: antibiotic action needs time and tissue perfusion to reach target. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):17.

Naucler P, Huttner A, van Werkhoven CH, Singer M, Tattevin P, Einav S, Tangden T. Impact of time to antibiotic therapy on clinical outcome in patients with bacterial infections in the emergency department: implications for antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(2):175–81.

Peltan P ID, Brown SM, Bledsoe JR, Sorensen J, Samore MH, Allen TL, Hough CL. ED door-to-antibiotic time and long-term mortality in Sepsis. Chest. 2019;155(5):938–46.

Seymour CW, Gesten F, Prescott HC, Friedrich ME, Iwashyna TJ, Phillips GS, et al. Time to treatment and mortality during mandated Emergency Care for Sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(23):2235–44.

Singer M. Antibiotics for Sepsis: does each hour really count, or is it incestuous amplification? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(7):800–2.

Sterling SA, Miller WR, Pryor J, Puskarich MA, Jones AE. The impact of timing of antibiotics on outcomes in severe Sepsis and septic shock: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(9):1907–15.

Seok H, Song J, Jeon JH, Choi HK, Choi WS, Moon S, Park DW. Timing of antibiotics in septic patients: a prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(11):1495–500.

Scheeren TWL, Bakker J, De Backer D, Annane D, Asfar P, Boerma EC, et al. Current use of vasopressors in septic shock. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9(1):20.

Dunser MW, Takala J, Ulmer H, Mayr VD, Luckner G, Jochberger S, et al. Arterial blood pressure during early sepsis and outcome. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(7):1225–33.

Maheshwari K, Nathanson BH, Munson SH, Khangulov V, Stevens M, Badani H, et al. The relationship between ICU hypotension and in-hospital mortality and morbidity in septic patients. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44(6):857–67.

Jouffroy R, Gilbert B, Gueye PN, Tourtier JP, Bloch-Laine E, Ecollan P, et al. Prehospital hemodynamic optimisation is associated with a 30-day mortality decrease in patients with septic shock. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;45:105–11.

Li Y, Li H, Zhang D. Timing of norepinephrine initiation in patients with septic shock: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):488.

Kumar A, Haery C, Paladugu B, Kumar A, Symeoneides S, Taiberg L, et al. The duration of hypotension before the initiation of antibiotic treatment is a critical determinant of survival in a murine model of Escherichia coli septic shock: association with serum lactate and inflammatory cytokine levels. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(2):251–8.

Liu VX, Fielding-Singh V, Greene JD, Baker JM, Iwashyna TJ, Bhattacharya J, Escobar GJ. The timing of early antibiotics and hospital mortality in Sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(7):856–63.

Klompas M, Goldberg SA. Turning back the clock: Prehospital Antibiotics for patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2022;50(10):1537–40.

Kanwar M, Brar N, Khatib R, Fakih MG. Misdiagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia and inappropriate utilization of antibiotics: side effects of the 4-h antibiotic administration rule. Chest. 2007;131(6):1865–9.

Jouffroy R, Gilbert B, Tourtier JP, Bloch-Laine E, Ecollan P, Boularan J, et al. Prehospital Bundle of Care based on antibiotic therapy and hemodynamic optimization is Associated with a 30-Day mortality decrease in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2022;50(10):1440–8.

Jouffroy R, Gilbert B, Hassan A, Tourtier JP, Bloch-Laine E, Ecollan P, et al. Adequacy of probabilistic prehospital antibiotic therapy for septic shock. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;53:80–5.

Jouffroy R, Gilbert B, Tourtier JP, Bloch-Laine E, Ecollan P, Bounes V, et al. Impact of Prehospital Antibiotic Therapy on Septic Shock Mortality. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;25(3):317–24.

Jouffroy R, Gueye P, Vivien B. Turning back the clock: Prehospital Antibiotics for patients with septic shock: let us act at the right time. Crit Care Med. 2023;51(4):e97–8.

Jouffroy R, Vivien B. Prehospital Emergency Care in Sepsis: from the door-to-antibiotic to the antibiotic-at-Door Concept? Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16(6):775–6.

Jouffroy R, Hajjar A, Gilbert B, Tourtier JP, Bloch-Laine E, Ecollan P, et al. Prehospital norepinephrine administration reduces 30-day mortality among septic shock patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):345.

Thomson N. Emergency medical services in Zimbabwe. Resuscitation. 2005;65(1):15–9.

Jammeh A, Sundby J, Vangen S. Barriers to emergency obstetric care services in perinatal deaths in rural Gambia: a qualitative in-depth interview study. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2011;2011:981096.

Tayler-Smith K, Zachariah R, Manzi M, Van den Boogaard W, Nyandwi G, Reid T, et al. An ambulance referral network improves access to emergency obstetric and neonatal care in a district of rural Burundi with high maternal mortality. Trop Med Int Health. 2013;18(8):993–1001.

Amaral CB, Ralston DC, Becker TK. Prehospital point-of-care ultrasound: a transformative technology. SAGE Open Med. 2020;8:2050312120932706.

Ketelaars R, Reijnders G, van Geffen GJ, Scheffer GJ, Hoogerwerf N. ABCDE of prehospital ultrasonography: a narrative review. Crit Ultrasound J. 2018;10(1):17.

Darraj A, Hudays A, Hazazi A, Hobani A, Alghamdi A. The Association between Emergency Department Overcrowding and Delay in treatment: a systematic review. Healthc (Basel). 2023;11(3).

Ju T, Al-Mashat M, Rivas L, Sarani B. Sepsis Rapid Response teams. Crit Care Clin. 2018;34(2):253–8.

Lafon T, Baisse A, Karam HH, Organista A, Boury M, Otranto M, et al. Sepsis unit in the Emergency Department: impact on management and outcome of septic patients. Shock. 2023;60(2):157–62.

Currie KE, Barry H, Scanlan JM, Harvey EM. Impact of a multidisciplinary sepsis huddle in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2023;64:150–4.

Simon EL, Truss K, Smalley CM, Mo K, Mangira C, Krizo J, Fertel BS. Improved hospital mortality rates after the implementation of emergency department sepsis teams. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;51:218–22.

Whitfield PL, Ratliff PD, Lockhart LL, Andrews D, Komyathy KL, Sloan MA, et al. Implementation of an adult code sepsis protocol and its impact on SEP-1 core measure perfect score attainment in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(5):879–82.

Nelson NR, Morbitzer KA, Jordan JD, Rhoney DH. The impact of capping Creatinine Clearance on achieving therapeutic vancomycin concentrations in neurocritically ill patients with traumatic brain Injury. Neurocrit Care. 2019;30(1):126–31.

Gregoire N, Marchand S, Ferrandiere M, Lasocki S, Seguin P, Vourc’h M, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of daptomycin in critically ill patients with various degrees of renal impairment. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74(1):117–25.

Cheng V, Abdul-Aziz MH, Roberts JA, Shekar K. Overcoming barriers to optimal drug dosing during ECMO in critically ill adult patients. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2019;15(2):103–12.

Roberts JA, Abdul-Aziz MH, Lipman J, Mouton JW, Vinks AA, Felton TW, et al. Individualised antibiotic dosing for patients who are critically ill: challenges and potential solutions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(6):498–509.

Veiga RP, Paiva JA. Pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics issues relevant for the clinical use of beta-lactam antibiotics in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):233.

Tabah A, Bassetti M, Kollef MH, Zahar JR, Paiva JA, Timsit JF, et al. Antimicrobial de-escalation in critically ill patients: a position statement from a task force of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) and European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious diseases (ESCMID) critically Ill patients Study Group (ESGCIP). Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(2):245–65.

Daniels R, Foot E, Pittaway S, Urzi S, Favry A, Miller M. Survey of adherence to sepsis care bundles in six European countries shows low adherence and possible patient risk. BMJ Open Qual. 2023;12(2).

Mutters NT, De Angelis G, Restuccia G, Di Muzio F, Schouten J, Hulscher M, et al. Use of evidence-based recommendations in an antibiotic care bundle for the intensive care unit. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018;51(1):65–70.

Workman JK, Chambers A, Miller C, Larsen GY, Lane RD. Best practices in pediatric sepsis: building and sustaining an evidence-based pediatric sepsis quality improvement program. Hosp Pract (1995). 2021;49(sup1):413 – 21.

Arabi YM, Myatra SN, Lobo SM. Surging ICU during COVID-19 pandemic: an overview. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2022;28(6):638–44.

Murthy S, Leligdowicz A, Adhikari NK. Intensive care unit capacity in low-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(1):e0116949.

Marra A, Ely EW, Pandharipande PP, Patel MB. The ABCDEF bundle in critical care. Crit Care Clin. 2017;33(2):225–43.

Sakai Y, Yamamoto S, Karasawa T, Sato M, Nitta K, Okada M, et al. Effects of early rehabilitation in sepsis patients by a specialized physical therapist in an emergency center on the return to activities of daily living independence: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(3):e0266348.

Liu K, Shibata J, Fukuchi K, Takahashi K, Sonoo T, Ogura T, Goto T. Optimal timing of introducing mobilization therapy for ICU patients with sepsis. J Intensive Care. 2022;10(1):22.

Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, Ely EW, Gelinas C, Dasta JF, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(1):263–306.

Prescott HC, Angus DC. Enhancing recovery from Sepsis: a review. JAMA. 2018;319(1):62–75.

Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, Hopkins RO, Weinert C, Wunsch H et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2):502-9.

Inoue S, Hatakeyama J, Kondo Y, Hifumi T, Sakuramoto H, Kawasaki T, et al. Post-intensive care syndrome: its pathophysiology, prevention, and future directions. Acute Med Surg. 2019;6(3):233–46.

Nakanishi N, Liu K, Kawakami D, Kawai Y, Morisawa T, Nishida T et al. Post-intensive Care Syndrome and its New challenges in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: a review of recent advances and perspectives. J Clin Med. 2021;10(17).

Vrettou CS, Mantziou V, Vassiliou AG, Orfanos SE, Kotanidou A, Dimopoulou I. Post-intensive Care Syndrome in survivors from critical illness including COVID-19 patients: a narrative review. Life (Basel). 2022;12(1).

Inoue S, Nakanishi N, Sugiyama J, Moriyama N, Miyazaki Y, Sugimoto T, et al. Prevalence and long-term prognosis of Post-intensive Care Syndrome after Sepsis: a single-center prospective observational study. J Clin Med. 2022;11:18.

Chao PW, Shih CJ, Lee YJ, Tseng CM, Kuo SC, Shih YN, et al. Association of postdischarge rehabilitation with mortality in intensive care unit survivors of sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(9):1003–11.

Whittaker J, Ball C. Discharge from intensive care: a view from the ward. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2000;16(3):135–43.

Cuzco C, Delgado-Hito P, Marin Perez R, Nunez Delgado A, Romero-Garcia M, Martinez-Momblan MA, et al. Patients’ experience while transitioning from the intensive care unit to a ward. Nurs Crit Care. 2022;27(3):419–28.

Ostermann M, Vincent JL. ICU without borders. Crit Care. 2023;27(1):186.

Gyllander T, Nappa U, Haggstrom M. Relatives’ experiences of care encounters in the general ward after ICU discharge: a qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2023;22(1):399.

Meiring-Noordstra A, van der Meulen IC, Onrust M, Hafsteinsdottir TB, Luttik ML. Relatives’ experiences of the transition from intensive care to home for acutely admitted intensive care patients-A qualitative study. Nurs Crit Care. 2023.

Haggstrom M, Backstrom B. Organizing safe transitions from intensive care. Nurs Res Pract. 2014;2014:175314.

Herbst LA, Desai S, Benscoter D, Jerardi K, Meier KA, Statile AM, White CM. Going back to the ward-transitioning care back to the ward team. Transl Pediatr. 2018;7(4):314–25.

Prescott HC, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ. Readmission diagnoses after hospitalization for severe sepsis and other acute medical conditions. JAMA. 2015;313(10):1055–7.

Prescott HC, Osterholzer JJ, Langa KM, Angus DC, Iwashyna TJ. Late mortality after sepsis: propensity matched cohort study. BMJ. 2016;353:i2375.

Goodwin AJ, Rice DA, Simpson KN, Ford DW. Frequency, cost, and risk factors of readmissions among severe sepsis survivors. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(4):738–46.

Taylor SP, Chou SH, Sierra MF, Shuman TP, McWilliams AD, Taylor BT, et al. Association between adherence to recommended care and outcomes for adult survivors of Sepsis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(1):89–97.

Bodenheimer T. Coordinating care–a perilous journey through the health care system. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(10):1064–71.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RJ, FD, RN, SJ, BV, NH and PG write and revise the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

none author has any competing interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jouffroy, R., Djossou, F., Neviere, R. et al. The chain of survival and rehabilitation for sepsis: concepts and proposals for healthcare trajectory optimization. Ann. Intensive Care 14, 58 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-024-01282-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-024-01282-6