Abstract

Background

Empathy is pivotal to effective clinical care. Yet, the art of nurturing and assessing empathy in medical schools is rarely consistent and poorly studied. To inform future design of programs aimed at nurturing empathy in medical students and doctors, a review is proposed.

Methods

This systematic scoping review (SSR) employs a novel approach called the Systematic Evidence Based Approach (SEBA) to enhance the reproducibility and transparency of the process. This 6-stage SSR in SEBA involved three teams of independent researchers who reviewed eight bibliographic and grey literature databases and performed concurrent thematic and content analysis to evaluate the data.

Results

In total, 24429 abstracts were identified, 1188 reviewed, and 136 included for analysis. Thematic and content analysis revealed five similar themes/categories. These comprised the 1) definition of empathy, 2) approaches to nurturing empathy, 3) methods to assessing empathy, 4) outcome measures, and 5) enablers/barriers to a successful curriculum.

Conclusions

Nurturing empathy in medicine occurs in stages, thus underlining the need for it to be integrated into a formal program built around a spiralled curriculum. We forward a framework built upon these stages and focus attention on effective assessments at each stage of the program. Tellingly, there is also a clear need to consider the link between nurturing empathy and one’s professional identity formation. This foregrounds the need for more effective tools to assess empathy and to better understand their role in longitudinal and portfolio based learning programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A physician’s ability to demonstrate empathy strengthens doctor-patient relationships [1, 2], boosts patient outcomes [3, 4], patient satisfaction [2, 5], increases professional satisfaction [6, 7], improves clinical competence [8, 9] and reduces potential burnout [10, 11].

Yet, despite these benefits and evidence of diminishing empathy midway through medical school [12, 13], empathy remains poorly nurtured in medical school and postgraduation [9, 14,15,16,17,18,19]. These gaps have been attributed to the lack of an accepted definition of empathy that fully considers cognitive, affective and behavioural components highlighted in current literature [20]. Inconsistencies in the structuring of programs aimed at nurturing empathy and the lack of effective assessment methods further exacerbate the issue [14, 18].

To enhance understanding of how empathy may best nurtured and to address prevailing knowledge gaps, we propose a review of prevailing efforts to nurture and assess empathy amongst physicians and medical students.

Methodology

The reflexive nature of systematic scoping reviews (SSR)s and their lack of structure raises concerns over their reproducibility and transparency. To overcome this, we adopted Krishna’s novel Systematic Evidence Based Approach (SEBA) [21,22,23]. Compared to other existing SSR approaches [24], SEBA acknowledges the complex nature of empathy and the need to evaluate how empathy is nurtured and assessed in different programs, involving different education and healthcare structures and funding. SEBA’s constructivist approach and relativist lens allow for a multi-dimensional, transparent, and reproducible method of studying empathy – a personalised, socioculturally and contextually informed concept. This SSR in SEBA also facilitates systematic extraction, synthesis and summary of actionable and applicable information across a diverse range of study formats and overcomes a paucity of articles on this subject.

To enhance accountability within the SEBA methodology, the research process is overseen by a team of experts comprising of a medical librarian from the National University of Singapore’s (NUS) Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (YLLSoM), educational, clinical and research experts from the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS), the Palliative Care Institute Liverpool, YLLSoM and Duke-NUS Medical School (henceforth the expert team). The SEBA process consists of the following six stages: 1) Systematic Approach, 2) Split Approach, 3) Jigsaw Perspective, 4) Funnelling Process 5) Analysis of data and non-data driven literature, and 6) Discussion. This is outlined in Fig. 1 and will be further elaborated.

Stage 1 of SEBA: Systematic approach

Determining title and research question

Guided by the expert team, the research team determined the primary research question to be “How effective are current methods to nurture empathy in doctors and medical students?” and the secondary research question to be “what are the features of these programs?”. These questions were designed on the Population, Concept, and Context (PCC) elements of the inclusion criteria [25] and were concurrently guided by the PRISMA-P 2015 checklist [26].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The PICOS format was used to guide the research process, as outlined in Table 1.

Searching

To enhance trustworthiness of this approach, five members of the research team carried out independent searches between 14th February and 24th April 2020 for articles in PubMed, Embase, PsychInfo, CINAHL, Scopus, Cochrane, OpenGrey and ProQuest Dissertations using identical inclusion and exclusion criteria and search terms. The PubMed search strategy may be found in Supplementary file 1. All articles published up to 31st December 2019 were included. The results of these independent searches were discussed online and consensus was achieved on the final list of articles to be included using Sandelowski and Barroso [27]’s ‘negotiated consensual validation’ approach.

Additional articles that meet the PICOS requirement were obtained by ancestry searching/ forward tracing of the references in the first set of included articles.

PRISMA

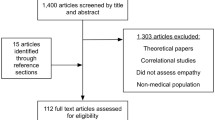

The research team identified 24,429 abstracts from the eight databases, 1188 articles were reviewed, and 136 articles were included (Fig. 2).

Stage 2 of SEBA: Split approach

Krishna’s Split Approach was employed to enhance the trustworthiness of the data analyses [21, 28]. The Split Approach saw two independent teams of at least three experienced researchers carrying out concurrent analysis of the included articles using Braun and Clarke [29]’s approach to thematic analysis and Hsieh and Shannon [30]’s approach to directed content analysis. Use of the Split Approach was employed in acknowledgment that a combination of these approaches reduces the omission of new findings and minimises the neglect of negative findings.

The categories for Hsieh and Shannon [30]’s approach to directed content analysis was drawn from Batt-Rawden, Chisolm [20] “Teaching Empathy to Medical Students: An Updated, Systematic Review”. Deductive category application was used to determine if any data was not captured by the pre-determined categories [31].

Stage 3 of SEBA: Jigsaw perspective

To present a holistic perspective of methods to nurture empathy, the Jigsaw Perspective pieces the themes identified through use of thematic analysis and categories used in directed content analysis in order to facilitate their effective interpretation and analysis.

Stage 4 of SEBA: Funnelling process

All 136 included articles were then independently reviewed and summarised using Wong et al.’s “RAMESES Publication Standards: Meta-narrative Reviews” [32] and Popay et al.’s “Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews” [33] These tabulated summaries ensure that key discussion points and contradictory views within the included articles are not lost (Supplementary file 2).

The themes/categories identified through the Split Approach were then compared with the tabulated summaries to prevent the loss of contradictory data and also served as a form of data triangulation. The verified themes/categories which will be presented in the Results section also formed the basis of the narrative synthesised in the Discussion section.

Stage 5 of SEBA: Analysis of data and non-data driven literature

In keeping with SEBA’s iterative process and active engagement with the expert team, the findings were discussed with the expert team and concerns were raised over the influence of grey literature on the results as these were neither peer reviewed nor clearly evidence based. Therefore, the research team differentiated grey literature such as correspondence, letters, editorials and perspective pieces extracted from academic databases, from data-driven and research-based peer reviewed articles. Both were analysed independently, and the themes derived from the grey literature were found to be in agreement with themes from the peer-reviewed literature [21,22,23, 34,36,37,37].

Results

The research team identified 24,429 abstracts were identified from eight databases, 1188 articles were reviewed and 136 articles were included in this review as shown in Fig. 2.

As the final five themes/categories identified through the Split Approach, Jigsaw Perspective and Funnelling Process were determined to be parallel in nature, they will be discussed in tandem for ease of understanding. The five themes/categories identified were the 1) definition of empathy, 2) approaches to nurturing empathy, 3) methods to assessing empathy, 4) outcome measures, and 5) enablers/barriers to a successful curriculum.

Definition of empathy

Overall, 35 articles stated that empathy was poorly defined in the literature [3, 6, 7, 10, 16, 17, 38,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,66]. Yet, analysis of prevailing accounts allow discernment of common characteristics amongst current accounts of empathy. Thus in the absence of a widely accepted definition of empathy, its cognitive, affective, behavioural, intrinsic and self-regulatory components must be considered.

The cognitive component suggests that empathy is “standing in the patient’s shoes” without confusing the patient’s experience as one’s own [67]. It hinges on identifying and understanding the patient’s perspective and mental state without losing objectivity. Sixty eight articles adopted variations of this approach [1, 2, 4, 5, 9, 11, 12, 14, 15, 17,18,19,20, 48, 60, 68,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,120].

The affective component sees recognition of the patient’s emotions and the offering of a suitable response [1, 2, 9, 11, 12, 15, 18, 20, 48, 67, 70, 79, 83, 88, 91,93,94,94, 98, 102, 104, 105, 108, 110,112,113,114,114, 118, 120,122,123,124,124]. The affective component is closely related to behavioural components of empathy which entail verbal and non-verbal communication of another person’s inner state [2, 11,12,13, 15, 18, 48, 60, 70, 71, 73, 76, 78, 83, 93, 95, 102, 106,108,109,110,111,111, 113, 115, 120, 125,127,128,128] and their intrinsic motivation to help others to reduce their distress [2, 4, 11, 12, 60, 83, 93, 106, 108, 113,115,115]. Decety and Meyer [129] and Airagnes et al. [67] argue that responding to the emotions and needs of others underscores the presence of self-regulation [129] and the ability to avoid “confusion between self and others” [67].

Approaches used

This theme/category revolves around the benefits of nurturing empathy in medicine for the patient and the physician, the methods of realising these benefits and the contents of these programs (Table 2).

A variety of approaches have been employed to nurture empathy but are not discussed in detail. For ease of reference they are summarised in Table 3.

Group discussions on personal experiences [71, 101, 115] and/or simulated scenarios including role play and simulated patients [16, 47, 57, 65] facilitate analysis of empathy [115] and shared experiences [63]. Role play has been found to boost participants’ confidence in communication [44, 118, 142, 144]. The use of the arts and humanities including poetry and literature [49, 57, 83, 136, 139], drawings and paintings [16, 43, 59, 83, 136, 139], reflective writing [49, 83, 136, 139], cultural studies and history [16], film [16], photography [59], and comics [5] have also shown to increase self-awareness and reflection [59].

The topics introduced in the ‘teaching’ of empathy vary significantly. They include mindfulness [17, 43, 78, 95, 105, 112, 115, 127, 133, 140, 148, 151, 152], communication and interpersonal skills [6, 12, 13, 15, 19, 38, 50, 51, 56, 60, 64, 69, 73, 85, 94, 105, 109, 115, 119, 121, 125, 127, 128, 138, 146, 143], and the arts and humanities [4, 5, 16, 43, 49, 57, 59, 72, 83, 139]. Teachings in mindfulness involve meditation and mindful listening [78, 95, 112, 133, 140] whilst communication skills include active listening [73, 125, 128, 138], use of open-ended questions [64], and improving communication among healthcare staff [69]. Arts based curricula include teachings such as principles of art therapy [136], art analysis [112], and social and cultural studies [16].

Critically, empathy was nurtured by facilitating understanding of the concept of empathy [19, 94, 108, 115], underscoring the differences between empathy and sympathy [108, 127], its importance [4, 94, 119] and its role in clinical practice [2, 12, 60, 68, 94, 108, 109].

Assessment methods used

Assessments of empathy involved self-rated, assessor and/or observer ratings. Whilst the most common assessment tool is the Jefferson Scale of Empathy (JSE), a number of other approaches have also been adopted as highlighted in Table 4.

In some cases, local assessment tools have adapted various elements of established tools such as the social presence questionnaire from the JSE [117], or the “perspective taking” and “empathic concern” subscales of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) [49].

Outcome measures of the curricula

The outcomes of different curricular programs varied. This is in part due to use of diverse approaches, contents, training programs, setting, duration and assessment methods. Table 5 summarises the reported outcomes.

The impact of programs aimed at nurturing empathy are widely reported and vary in their effects. Using the IRI, Sands et al. [101] reported increases in the “perspective taking” and “empathic concern” subscales, Airagnes et al. [67] reported an increase in the “fantasy” subscale, and Winkel et al. [49] reported an increase in “empathic concern”. Smith et al. [113] reported an increase in cognitive empathy using the Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy (QCAE), whilst Wellbery et al. [84] reported an increase in mean scores in the “contextual understanding of systemic barriers” domain of the Social Empathy Index (SEI) survey in their respective programs. Using the JSE, Stebbins [69] reported an improvement in the “ability to stand in patient’s shoes” subscale while San-Martín et al. [106], using three different curricula for three populations, concluded that the participants could either have increases in some or all three components of the scale depending on the approach employed [106].

Conversely, Airagnes et al. [67] reported a decrease in the “empathic concern” subscale of the IRI and San-Martín et al. [106] found a decrease in both the “compassionate care” and “walking in patient’s shoes” components of the JSE in the clinical phase of medical school. Bombeke et al. [80] suggest that these reductions in empathy related scores are the result of students witnessing the difference between idealistic teachings in their curriculum and the realities of clinical care and patient interactions. This may in turn have contributed to negative attitudes towards the training they received. Others suggest that a lack of finesse and clarity when using the tools may have contributed to a relative decrease in empathy scores [3, 97, 113, 139]. The apparent gaps in prevailing assessment tools are also highlighted when participants reported no significant change in self-reported scores on the JSE but simulated patients (SPs) and observers rated improved empathy scores [2, 12, 40, 88].

Notably, current tools seem to measure empathy along the different levels of Kirkpatrick’s Hierarchy [154]. This consists of Level 1 (participation), Level 2a (attitudes and perceptions) and Level 2b (knowledge and skills), Level 3 (behavioural change), Level 4a (organisational practice) and Level 4b (patient benefits). Whilst 29 of the 136 articles measured changes at Level 3, 20 focused on Level 4. These are summarised in Table 6.

Twenty one of the 29 studies that focused upon Level 3 of Kirkpatrick’s Hierarchy focused on general communication skills training. Fifteen of these studies employed role play, simulations and/or patient interviews to encourage communication skills [7, 40, 46, 50, 58, 64, 88, 91, 111, 115,117,117, 120, 125, 143] in a safe practice space [7, 9, 44, 62, 115, 147].

A common feature among the studies aiming at Level 4 of Kirkpatrick’s Hierarchy was that they encouraged participants to consider mindfulness [140, 152] and the patient’s perspective [43, 53, 62, 63] in their communications. Most Level 4 studies involved real or virtual patients as part of the assessment process [117, 120]. Kleinsmith et al. [117] noted that responses to virtual patients tend to be more empathetic than those to simulated patients.

Enablers and barriers for successful curricula

Table 7 provides a summary of the major enablers and barriers to implementing a successful curriculum.

Discussion

Stage 6 of SEBA: Discussion synthesis of SSR in SEBA

In answering its primary and secondary questions, this SEBA guided review provides a number of key insights.

Our findings suggest that empathy may be described as a “physician’s recognition and self-regulated cognitive, affective and behavioural response to a patient’s, family member’s, caregiver’s and/or a healthcare professional’s distress. This response does not conflate and confuse the patient’s, family member’s, caregiver’s and/or a healthcare professional’s distress with the physician’s own experiences and situation.” It is also apparent that empathy may be nurtured by building upon the individual’s innate ability to respond to the perceived state of mind, emotion and perspective of the other person. This process of nurturing empathy appears to occur in stages.

Stage 1 involves an introduction to concepts of empathy [4, 12, 115, 119]. These sessions are often in the form of didactic teaching sessions and discussions [7, 90].

Stage 2 acknowledges different learning styles [63] and offers a combination of teaching modalities to provide a holistic approach to nurturing empathy. This includes role play and simulations to practice communication skills [7, 15, 42, 44, 46, 51, 77, 85, 105, 107, 111, 115, 116, 118, 121, 123, 127, 142, 144] in a safe environment to share opinions and observations freely [7, 9, 44, 62, 115, 147].

Stage 3 involves debriefs and personalised, appropriate, specific, timely, actionable and holistic feedback [2, 38, 98, 125]. Reflective exercises [2, 38, 98, 125] and facilitated group discussion are used to explore learning points and experiences [52, 53, 66, 105, 115, 150] and to promote interprofessional education [7].

Stage 4 acknowledges the need to apply interpersonal and empathetic communication skills [44, 118, 142, 144] to elicit a holistic history from the patient [7, 105, 111]. This stage also acknowledges the shortfalls and inaccuracies posed when using simulated and virtual patients [80, 117, 120]. This stage also includes debriefs and feedback [2, 38, 98, 125], reflective exercises [2, 38, 98, 125] and facilitated group discussions [52, 53, 66, 105, 115, 150]. These methods should emphasise on building and bolstering the learner’s confidence and skills when communicating with patients.

Here the notion that external factors – such as practice culture, educational setting, clinical specialities, prevailing sociocultural norms, professional and practical considerations and regnant sociocultural, healthcare and educational systems – also impact empathetic responses suggests that these responses may vary in different circumstances. In addition, evidence that intrinsic motivations are informed by the physician’s demographic, historical, socio-cultural, ideological and contextual circumstances suggests that empathy is also a sociocultural construct demanding a personalised approach when nurturing and assessing empathy in physicians.

Acknowledgment that there are stages to empathy training that are influenced by contextual factors as well as innate considerations underscores the need to develop a ‘spiral curriculum’ [156] where each step repeatedly builds on prior knowledge and skills (horizontal integration) as more complex competencies are introduced and assessed in various settings. This spiralled approach must also be personalised and frequently assessed to inform effective nurturing of empathy. This underlines the need for personalised micro-competencies and general milestones to ensure that physicians are effectively supported in a manner appropriate to their abilities, needs and circumstances as well as the educational goals and training context. Personalised micro-competencies depend on the physician’s training, knowledge, skills, experience, motivations and circumstances, thus underlining the importance of assessing each physician’s individual needs so as to shape training and proffer appropriate support. General milestones relate to common expectations placed upon all physicians at each stage of their training and allows due consideration of the contextual aspects of empathy. The presence of general milestones underlines the need for different stages of the program to be carried out at a period in which there is relevant clinical training (vertical integration). This is so that the process of nurturing empathy occurs at a time where the physician can best appreciate its relevance to their practice and role and thereafter apply their new skills under supervision before doing so independently.

The need for horizontal and vertical integration within the spiral curriculum and the presence of personalised micro-competencies and general milestones underscore the need for efforts to nurture empathy to be integrated into a formal curriculum. The formal curriculum will also facilitate holistic and longitudinal assessments with clear opportunities for targeted and timely intervention and remediation before the physician lags too far behind. In addition, being integrated into the formal medical curricula allows for ‘protected time’ allocated [5, 41, 97, 148, 151] for training both learners and faculty members overseeing and conducting the curricula [7, 42, 44, 55, 70, 72, 79, 81, 83, 85, 97, 100, 101, 105, 125, 128, 133, 143].

However, a general lack of evidence for the efficacy of various assessment tools in the prevailing literature, the different foci of empathy training, and their stage sensitive nature renders the selection of an appropriate assessment tool a challenging task. This is especially so as different tools fundamentally pivot on different facets of empathy’s diverse conceptualisations. For example, the IRI focuses on measures of both cognitive and affective empathy [157] whilst the Empathy Scale focuses only on the cognitive [158] and the Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale only on the affective [159]. As a result, curriculum developers should ideally consider an amalgamation of assessment tools employed along the spiral curriculum, with assessment outcomes ‘stored’ in longitudinal portfolios to ensure transparency and rigorous follow-up across tutors and practice setting. Multi-source assessments of individuals and program outcomes will allow for changes in practices and attitudes [5, 41, 97, 148, 151] and will facilitate the inclusion of holistic assessments from assessors and observers [160] that ought to capture contextual considerations impacting progress and practice.

Limitations

Whilst SEBA offers an evidence based, comprehensive, reproducible and transparent approach to reviews across a wide range of settings and socio-culturally informed concepts, it is a resource intensive approach as SEBA requires at least three independent teams to perform the Split Approach and Funnelling Process appropriately. Concurrently, whilst the SEBA guided review has provided a number of new insights, reliance upon the expert team may be time consuming as it draws out the various SEBA stages.

In addition, its comprehensive approach does not circumnavigate other limitations such as the exclusion of publications that were not published in or translated into English. This is particularly important given that the concept of empathy is culturally informed. With 77% of the included articles conducted in a Western population, there is a significant risk that the concepts delineated here may not truly reflect how it is conceived in other parts of the world.

Further context specific elucidation of concepts of empathy in physician-patient relationships [1, 2, 4], on patient outcomes [3, 4, 12, 121] and satisfaction [2, 5, 15, 133], physician burnout [10, 11, 68], emotional exhaustion [161], professional satisfaction [6, 7, 12, 60], and clinical competence [4, 8, 9, 110] are required particularly when it appears that contextual considerations surrounding empathy impact behaviour and motivation.

Lastly, large variations in assessment methods were employed across the studies, making it difficult to compare outcome measures of nurturing empathy.

Conclusion

In answering its primary and secondary research questions, this review advances a more holistic understanding of empathy and proffers a stage-wise framework to guide the design of a formal, multimodal, longitudinal and spiralled program to nurture and assess empathy in medical education.

Whilst it is clear that assessments of empathy need to be improved if empathy is to be effectively nurtured, it is also evident that use of a mix of tools over each stage of the nurturing process requires the employ of portfolios. Portfolios replete with reflective entries and accounts of critical incidents will help assess wider and longitudinal influences upon the learner, including why and how these experiences may have affected their practice and their professional identity. It is evident that pragmatic and efficacious use of portfolios and empathy’s potential links with professional identity formation deserve closer scrutiny in future research endeavours.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- SEBA:

-

Systematic Evidence Based Approach

- NUS:

-

National University of Singapore

- YLLSoM:

-

Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine

- NCCS:

-

National Cancer Centre Singapore

- PCC:

-

Population, Concept and Context

- PICOS:

-

Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, Study Design

- JSE:

-

Jefferson Scale of Empathy

- IRI:

-

Interpersonal Reactivity Index

- QCAE:

-

Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy

- SEI:

-

Social Empathy Index

- SP:

-

Simulated Patients

References

Chen A, Hanna JJ, Manohar A, Tobia A. Teaching empathy: the implementation of a video game into a psychiatry clerkship curriculum. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(3):362–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-017-0862-6.

Wündrich M, Schwartz C, Feige B, Lemper D, Nissen C, Voderholzer U. Empathy training in medical students - a randomized controlled trial. Med Teach. 2017;39(10):1096–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2017.1355451.

Liu GZ, Jawitz OK, Zheng D, Gusberg RJ, Kim AW. Reflective writing for medical students on the surgical clerkship: oxymoron or antidote? J Surg Educ. 2016;73(2):296–304.

Hojat M, Axelrod D, Spandorfer J, Mangione S. Enhancing and sustaining empathy in medical students. Med Teach. 2013;35(12):996–1001.

Tsao P, Yu CH. “There’s no billing code for empathy” - Animated comics remind medical students of empathy: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):204.

Noordman J, Post B, van Dartel AAM, Slits JMA, Olde Hartman TC. Training residents in patient-centred communication and empathy: evaluation from patients, observers and residents. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):128.

Kaplan-Liss E, Lantz-Gefroh V, Bass E, Killebrew D, Ponzio NM, Savi C, et al. Teaching medical students to communicate with empathy and clarity using improvisation. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):440–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002031.

Kataoka H, Iwase T, Ogawa H, Mahmood S, Sato M, DeSantis J, et al. Can communication skills training improve empathy? A six-year longitudinal study of medical students in Japan. Med Teach. 2019;41(2):195–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1460657.

Koblar S, Cranwell M, Koblar S, Carnell B, Galletly C. Developing empathy: does experience through simulation improve medical-student empathy? Med Sci Educ. 2018;28(1):31–6.

Kane SE. The effects of a longitudinal patient experience on the enhancement of empathy in first and second year medical students [Ph.D.]. Ann Arbor: City University of New York; 2018.

Bergstresser K. Empathy in medical students: exploring the impact of a longitudinal integrated clerkship model [Psy.D.]. Ann Arbor: Marywood University; 2017.

Riess H, Kelley JM, Bailey RW, Dunn EJ, Phillips M. Empathy training for resident physicians: a randomized controlled trial of a neuroscience-informed curriculum. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1280–6.

Kramer D, Ber R, Moore M. Increasing empathy among medical students. Med Educ. 1989;23(2):168–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.1989.tb00881.x.

Patel S, Pelletier-Bui A, Smith S, Roberts MB, Kilgannon H, Trzeciak S, et al. Curricula for empathy and compassion training in medical education: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0221412.

Bonvicini KA, Perlin MJ, Bylund CL, Carroll G, Rouse RA, Goldstein MG. Impact of communication training on physician expression of empathy in patient encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75(1):3–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2008.09.007.

Graham J, Benson LM, Swanson J, Potyk D, Daratha K, Roberts K. Medical humanities coursework is associated with greater measured empathy in medical students. Am J Med. 2016;129(12):1334–7.

Chinai S, Bird S, Boudreaux E. The ABCs of empathy. Western J Emerg Med. 2016;17:S73–S4.

Fragkos KC, Crampton PES. The effectiveness of teaching clinical empathy to medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Acad Med. 2020;95(6):947–57.

Sanson-Fisher RW, Poole AD. Training medical students to empathize: an experimental study. Med J Aust. 1978;1(9):473–6.

Batt-Rawden SA, Chisolm MS, Anton B, Flickinger TE. Teaching empathy to medical students: an updated, systematic review. Acad Med. 2013;88(8):1171–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318299f3e3.

Kow CS, Teo YH, Teo YN, Chua KZY, Quah ELY, Kamal NHBA, et al. A systematic scoping review of ethical issues in mentoring in medical schools. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):1–10.

Krishna LKR, Tan LHE, Ong YT, Tay KT, Hee JM, Chiam M, et al. Enhancing mentoring in palliative care: an evidence based mentoring framework. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120520957649.

Ngiam LXL, Ong YT, Ng JX, Kuek JTY, Chia JL, Chan NPX, et al. Impact of Caring for Terminally Ill Children on Physicians: A Systematic Scoping Review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2021;38(4):396–418.

Arksey H. L. OM. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, McInerney P, Soares CB, Khalil H, Parker D. The Joanna Briggs institute reviewers’ manual 2015: methodology for JBI scoping reviews; 2015.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1.

Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research; 2006.

Ng YX, Koh ZYK, Yap HW, Tay KT, Tan XH, Ong YT, et al. Assessing mentoring: A scoping review of mentoring assessment tools in internal medicine between 1990 and 2019. PLos One. 2020;15(5):e0232511.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88.

Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–15.

Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Buckingham J, Pawson R. RAMESES publication standards: meta-narrative reviews. BMC Med. 2013;11(1):20.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme Version, vol. 1; 2006. p. b92.

Bok C, Ng CH, Koh JWH, Ong ZH, Ghazali HZB, Tan LHE, et al. Interprofessional communication (IPC) for medical students: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):372. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02296-x.

Kamal NHA, Tan LHE, Wong RSM, Ong RRS, Seow REW, Loh EKY, et al. Enhancing education in palliative medicine: the role of systematic scoping reviews. Palliat Med Care. 2020;7(1):1–11.

Ong RRS, Seow REW, Wong RSM, Loh EKY, Kamal NHA, Mah ZH, et al. A systematic scoping review of narrative reviews in palliative medicine education. Palliat Med Care. 2020;7(1):1–22.

Mah ZH, Wong RSM, Seow REW, Loh EKY, Kamal NHA, Ong RRS, et al. A systematic scoping review of systematic reviews in palliative medicine education. Palliat Med Care. 2020;7(1):1–12.

Tulsky JA, Arnold RM, Alexander SC, Olsen MK, Jeffreys AS, Rodriguez KL, et al. Enhancing communication between oncologists and patients with a computer-based training program: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(9):593–601. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-155-9-201111010-00007.

Hart CN, Drotar D, Gori A, Lewin L. Enhancing parent–provider communication in ambulatory pediatric practice. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;63(1):38–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2005.08.007.

LoSasso AA, Lamberton CE, Sammon M, Berg KT, Caruso JW, Cass J, et al. Enhancing student empathetic engagement, history-taking, and communication skills during electronic medical record use in patient care. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):1022–7.

Sin D, Chew T, Chia TK, Ser JS, Sayampanathan A, Koh G. Evaluation of constructing care collaboration - nurturing empathy and peer-to-peer learning in medical students who participate in voluntary structured service learning programmes for migrant workers. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):304.

Razavi D, Merckaert I, Marchal S, Libert Y, Conradt S, Boniver J, et al. How to optimize physicians’ communication skills in cancer care: results of a randomized study assessing the usefulness of posttraining consolidation workshops. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(16):3141–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2003.08.031.

Canales C, Strom S, Anderson CT, Fortier MA, Cannesson M, Rinehart JB, et al. Humanistic medicine in anaesthesiology: development and assessment of a curriculum in humanism for postgraduate anaesthesiology trainees. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123(6):887–97.

Vargas Pelaez AF, Ramirez SI, Valdes Sanchez C, Piedra Abusharar S, Romeu JC, Carmichael C, et al. Implementing a medical student interpreter training program as a strategy to developing humanism. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):141.

Riess H, Kelley JM, Bailey R, Konowitz PM, Gray ST. Improving empathy and relational skills in otolaryngology residents: a pilot study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;144(1):120–2. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599810390897.

Bays AM, Engelberg RA, Back AL, Ford DW, Downey L, Shannon SE, et al. Interprofessional communication skills training for serious illness: evaluation of a small-group, simulated patient intervention. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(2):159–66. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2013.0318.

Singh SP, Modi CM, Patel CP, Pathak AG. Low-fidelity simulation to enhance understanding of infection control among undergraduate medical students. Natl Med J India. 2017;30(4):215–8.

Yamada Y, Fujimori M, Shirai Y, Ninomiya H, Oka T, Uchitomi Y. Changes in Physicians’ intrapersonal empathy after a communication skills training in Japan. Acad Med. 2018;93(12):1821–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002426.

Winkel AF, Feldman N, Moss H, Jakalow H, Simon J, Blank S. Narrative Medicine Workshops for Obstetrics and Gynecology Residents and Association With Burnout Measures. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(Suppl 1):27s–33s.

Ditton-Phare P, Sandhu H, Kelly B, Kissane D, Loughland C. Pilot evaluation of a communication skills training program for psychiatry residents using standardized patient assessment. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(5):768–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-016-0560-9.

Shapiro J, Rucker L, Boker J, Lie D. Point-of-view writing: a method for increasing medical students’ empathy, identification and expression of emotion, and insight. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2006;19(1):96–105.

Duke P, Grosseman S, Novack DH, Rosenzweig S. Preserving third year medical students’ empathy and enhancing self-reflection using small group “virtual hangout” technology. Med Teach. 2015;37(6):566–71.

Sweeney K, Baker P. Promoting empathy using video-based teaching. Clin Teach. 2018;15(4):336–40.

Wiecha JM, Markuns JF. Promoting medical humanism: design and evaluation of an online curriculum. Fam Med. 2008;40(9):617–9.

Dhaliwal U, Singh S, Singh N. Reflective student narratives: honing professionalism and empathy. Indian J Med Ethics. 2018;3(1):9–15.

Delacruz N, Reed S, Splinter A, Brown A, Flowers S, Verbeck N, et al. Take the HEAT: a pilot study on improving communication with angry families. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(6):1235–9.

Muszkat M, Yehuda AB, Moses S, Naparstek Y. Teaching empathy through poetry: a clinically based model. Med Educ. 2010;44(5):503. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03673.x.

Junek W, Burra P, Leichner P. Teaching interviewing skills by encountering patients. J Med Educ. 1979;54(5):402–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-197905000-00008.

He B, Prasad S, Higashi RT, Goff HW. The art of observation: a qualitative analysis of medical students’ experiences. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):234. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1671-2.

Ozcan CT, Oflaz F, Bakir B. The effect of a structured empathy course on the students of a medical and a nursing school. Int Nurs Rev. 2012;59(4):532–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-7657.2012.01019.x.

Shapiro J, Youm J, Kheriaty A, Pham T, Chen Y, Clayma R. The human kindness curriculum: an innovative preclinical initiative to highlight kindness and empathy in medicine. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2019;32(2):53–61.

Wilkes M, Milgrom E, Hoffman JR. Towards more empathic medical students: a medical student hospitalization experience. Med Educ. 2002;36(6):528–33.

Ohuabunwa U, Perkins M, Eskildsen M, Flacker J. Towards patient safety: promoting clinical empathy through an experiential curriculum in care transitions among the underserved. Med Sci Educ. 2017;27(4):613–20.

Roter DL, Larson S, Shinitzky H, Chernoff R, Serwint JR, Adamo G, et al. Use of an innovative video feedback technique to enhance communication skills training. Med Educ. 2004;38(2):145–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2004.01754.x.

Kommalage M. Using videos to introduce clinical material: effects on empathy. Med Educ. 2011;45(5):514–5.

Deloney LA, Graham CJ. Wit: using drama to teach first-year medical students about empathy and compassion. Teach Learn Med. 2003;15(4):247–51.

Airagnes G, Consoli SM, De Morlhon O, Galliot A-M, Lemogne C, Jaury P. Appropriate training based on Balint groups can improve the empathic abilities of medical students: a preliminary study. J Psychosom Res. 2014;76(5):426–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.03.005.

Williams B, Sadasivan S, Kadirvelu A, Olaussen A. Empathy levels among first year Malaysian medical students: an observational study. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2014;5:149–56.

Stebbins CA. Enhancing empathy in medical students using Flex Care (TM) communication training. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences Engineering. 2005;66(4-B):1962.

Wang R, Houlden RL, Yu CH. Graphic stories as cultivators of empathy in medical clerkship education. Med Sci Educ. 2018;28(4):609–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-018-0590-x.

Rosenthal S, Howard B, Schlussel YR, Herrigel D, Smolarz BG, Gable B, et al. Humanism at heart: preserving empathy in third-year medical students. Acad Med. 2011;86(3):350–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318209897f.

Van Winkle LJ, Fjortoft N, Hojat M. Impact of a workshop about aging on the empathy scores of pharmacy and medical students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(1):9.

Fernández-Olano C, Montoya-Fernández J, Salinas-Sánchez AS. Impact of clinical interview training on the empathy level of medical students and medical residents. Med Teach. 2008;30(3):322–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590701802299.

Schoonover KL, Hall-Flavin D, Whitford K, Lussier M, Essary A, Lapid MI. Impact of poetry on empathy and professional burnout of health-care workers: a systematic review. J Palliat Care. 2020;35(2):127–32.

Misra-Hebert AD, Isaacson JH, Kohn M, Hull AL, Hojat M, Papp KK, et al. Improving empathy of physicians through guided reflective writing. Int J Med Educ. 2012;3:71–7. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.4f7e.e332.

Kelm Z, Womer J, Walter JK, Feudtner C. Interventions to cultivate physician empathy: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):219. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-219.

Gibon AS, Merckaert I, Liénard A, Libert Y, Delvaux N, Marchal S, et al. Is it possible to improve radiotherapy team members’ communication skills? A randomized study assessing the efficacy of a 38-h communication skills training program. Radiother Oncol. 2013;109(1):170–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2013.08.019.

van Vliet M, Jong M, Jong MC. Long-term benefits by a mind-body medicine skills course on perceived stress and empathy among medical and nursing students. Med Teach. 2017;39(7):710–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2017.1309374.

Karaoglu N, Seker M. Looking for winds of change with a PBL scenario about communication and empathy. HealthMED. 2011;5(3):515–21.

Bombeke K, Van Roosbroeck S, De Winter B, Debaene L, Schol S, Van Hal G, et al. Medical students trained in communication skills show a decline in patient-centred attitudes: an observational study comparing two cohorts during clinical clerkships. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84(3):310–8.

DelPrete A, Giordano C, Castiglioni A, Hernandez C. Medical Students’ attitudes toward non-adherent patients before and after a simulated patient-role activity and small-group discussion: revisited. Cureus. 2016;8(4):e576.

Wellbery C, Barjasteh T, Korostyshevskiy V. Medical students’ individual and social empathy: a follow-up study. Med Teach. 2019;41(6):656–61.

Afghani B, Besimanto S, Amin A, Shapiro J. Medical students’ perspectives on clinical empathy training. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2011;24(1):544.

Wellbery C, Saunders PA, Kureshi S, Visconti A. Medical Students’ empathy for vulnerable groups: results from a survey and reflective writing assignment. Acad Med. 2017;92(12):1709–14. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001953.

Cinar O, Ak M, Sutcigil L, Congologlu ED, Canbaz H, Kilic E, et al. Communication skills training for emergency medicine residents. Eur J Emerg Med. 2012;19(1):9–13.

Pedersen R. Empathy development in medical education--a critical review. Med Teach. 2010;32(7):593–600. https://doi.org/10.3109/01421590903544702.

Graham KL, Green S, Kurlan R, Pelosi JS. A patient-led educational program on Tourette syndrome: impact and implications for patient-centered medical education. Teach Learn Med. 2014;26(1):34–9.

Esfahani MN, Behzadipour M, Nadoushan AJ, Shariat SV. A pilot randomized controlled trial on the effectiveness of inclusion of a distant learning component into empathy training. Med J Islamic Repub Iran. 2014;28(1):65.

Yang KT, Yang JH. A study of the effect of a visual arts-based program on the scores of Jefferson scale for physician empathy. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:142.

Ahmadzadeh A, Esfahani MN, Ahmadzad-Asl M, Shalbafan M, Shariat SV. Does watching a movie improve empathy? A cluster randomized controlled trial. Can Med Educ J. 2019;10(4):e4–e12. https://doi.org/10.36834/cmej.56979.

Lim BT, Moriarty H, Huthwaite M. “Being-in-role”: a teaching innovation to enhance empathic communication skills in medical students. Med Teach. 2011;33(12):e663–9. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2011.611193.

McDonald P, Ashton K, Barratt R, Doyle S, Imeson D, Meir A, et al. Clinical realism: a new literary genre and a potential tool for encouraging empathy in medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):112. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0372-8.

Stepien KA, Baernstein A. Educating for empathy. A review. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(5):524–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00443.x.

D’Souza PC, Rasquinha SL, D'Souza TL, Jain A, Kulkarni V, Pai K. Effect of a single-session communication skills training on empathy in medical students. Acad Psychiatry. 2020;44(3):289–94.

Shapiro SL, Schwartz GE, Bonner G. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on medical and premedical students. J Behav Med. 1998;21(6):581–99. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018700829825.

Cai F, Ruhotina M, Bowler M, Howard E, Has P, Frishman GN, et al. Can I get a suggestion? Medical Improv as a tool for empathy training in obstetrics and gynecology residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(5):597–600.

Johnson LA, Gorman C, Morse R, Firth M, Rushbrooke S. Does communication skills training make a difference to patients’ experiences of consultations in oncology and palliative care services? Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2013;22(2):202–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12014.

Sripada BN, Henry DB, Jobe TH, Winer JA, Schoeny ME, Gibbons RD. A randomized controlled trial of a feedback method for improving empathic accuracy in psychotherapy. Psychol Psychother. 2011;84(2):113–27. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608310X495110.

Norfolk T, Birdi K, Patterson F. Developing therapeutic rapport: a training validation study. Qual Prim Care. 2009;17(2):99–106.

Thepwiwatjit S, Athisereerusth S, Lertpipopmetha W, Nanthanasub T, Dangprapai Y. Patient interviews improve empathy levels of preclinical medical students. Siriraj Med J. 2019;71(1):44–51.

Sands SA, Stanley P, Charon R. Pediatric narrative oncology: interprofessional training to promote empathy, build teams, and prevent burnout. J Support Oncol. 2008;6(7):307–12.

DasGupta S, Charon R. Personal illness narratives: using reflective writing to teach empathy. Acad Med. 2004;79(4):351–6.

Deen SR, Mangurian C, Cabaniss DL. Points of contact: using first-person narratives to help foster empathy in psychiatric residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2010;34(6):438–41.

Buffel du Vaure C, Lemogne C, Bunge L, Catu-Pinault A, Hoertel N, Ghasarossian C, et al. Promoting empathy among medical students: A two-site randomized controlled study. J Psychosom Res. 2017;103:102–7.

Bentley PG, Kaplan SG, Mokonogho J. Relational mindfulness for psychiatry residents: a pilot course in empathy development and burnout prevention. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(5):668–73.

San-Martín M, Delgado-Bolton R, Vivanco L. Role of a semiotics-based curriculum in empathy enhancement: a longitudinal study in three Dominican medical schools. Front Psychol. 2017;8:2018. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02018.

Alexander C, Sheeler RD, Rasmussen NH, Hayden L. Teaching an experiential mind-body method to medical students to increase interpersonal skills: a pilot study. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(3):316–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-014-0159-y.

Srivastava AK, Tiwari K, Vyas S, Semwal J, Kandpal SD. Teaching clinical empathy to undergraduate medical students of Dehradun: a quasi-experimental study. Indian J Community Health. 2017;29(3):258–63.

Dereboy C, Harlak H, Gürel S, Gemalmaz A, Eskin M. Teaching empathy in medical education. Turk psikiyatri dergisi [Turkish journal of psychiatry]. 2005;16(2):83–9.

Shapiro J, Morrison E, Boker J. Teaching empathy to first year medical students: evaluation of an elective literature and medicine course. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2004;17(1):73–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576280310001656196.

Ruiz-Moral R, Monge D, García Leonardo C, Caballero F, Pérula de Torres L. Teaching medical students to express empathy by exploring patient emotions and experiences in standardized medical encounters. Patient Educ Counseling. 2017;100(9):1694–700.

Zazulak J, Sanaee M, Frolic A, Knibb N, Tesluk E, Hughes E, et al. The art of medicine: arts-based training in observation and mindfulness for fostering the empathic response in medical residents. Med Humanit. 2017;43(3):192–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2016-011180.

Smith KE, Norman GJ, Decety J. The complexity of empathy during medical school training: evidence for positive changes. Med Educ. 2017;51(11):1146–59.

Schweller M, Costa FO, Antônio M, Amaral EM, de Carvalho-Filho MA. The impact of simulated medical consultations on the empathy levels of students at one medical school. Acad Med. 2014;89(4):632–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000175.

Bayne HB. Training medical students in empathic communication. J Specialists Group Work. 2011;36(4):316–29.

Pacoe LV, Naar R, Guyett IP, Wells R. Training medical students in interpersonal relationship skills. J Med Educ. 1976;51(09):743–50. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-197609000-00005.

Kleinsmith A, Rivera-Gutierrez D, Finney G, Cendan J, Lok B. Understanding empathy training with virtual patients. Comput Human Behav. 2015;52:151–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.05.033.

Singh K, Bhattacharyya M, Veerwal V, Singh A. Using role-plays as an empathy education tool for ophthalmology postgraduate. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2017;7(Suppl 1):S62–s6.

Dow AW, Leong D, Anderson A, Wenzel RP. Using theater to teach clinical empathy: a pilot study. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(8):1114–8.

Foster A, Chaudhary N, Kim T, Waller JL, Wong J, Borish M, et al. Using virtual patients to teach empathy: a randomized controlled study to enhance medical Students’ empathic communication. Simul Healthc. 2016;11(3):181–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0000000000000142.

Fine VK, Therrien ME. Empathy in the doctor-patient relationship: skill training for medical students. J Med Educ. 1977;52(9):752–7.

McManus S, Killeen D, Hartnett Y, Fitzgerald G, Murphy KC. Establishing and evaluating a Balint group for fourth-year medical students at an Irish University. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020;37(2):99–105.

Stebletsova AO, Torubarova II. Empathy development through ESP: a pilot study. J Educ Cultural Psychological Stud. 2017;2017(16):237–49.

Schweller M, Ribeiro DL, Celeri EV, de Carvalho-Filho MA. Nurturing virtues of the medical profession: does it enhance medical students’ empathy? Int J Med Educ. 2017;8:262–7. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5951.6044.

Winefield HR, Chur-Hansen A. Evaluating the outcome of communication skill teaching for entry-level medical students: does knowledge of empathy increase? Med Educ. 2000;34(2):90–4. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00463.x.

Poole AD, Sanson-Fisher RW. Long-term effects of empathy training on the interview skills of medical students. Patient Couns Health Educ. 1980;2(3):125–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0738-3991(80)80053-X.

Yun JY, Kim KH, Joo GJ, Kim BN, Roh MS, Shin MS. Changing characteristics of the empathic communication network after empathy-enhancement program for medical students. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):15092. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-33501-z.

Moorhead R, Winefield H. Teaching counselling skills to fourth-year medical students: a dilemma concerning goals. Fam Pract. 1991;8(4):343–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/8.4.343.

Decety J, Meyer M. From emotion resonance to empathic understanding: a social developmental neuroscience account. Dev Psychopathol. 2008;20(4):1053–80.

Varkey P, Chutka DS, Lesnick TG. The aging game: improving medical students’ attitudes toward caring for the elderly. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2006;7(4):224–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2005.07.009.

Han JL, Pappas TN. A review of empathy, its importance, and its teaching in surgical training. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(1):88–94.

Son D, Shimizu I, Ishikawa H, Aomatsu M, Leppink J. Communication skills training and the conceptual structure of empathy among medical students. Perspect Med Educ. 2018;7(4):264–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-018-0431-z.

Bond AR, Mason HF, Lemaster CM, Shaw SE, Mullin CS, Holick EA, et al. Embodied health: the effects of a mind-body course for medical students. Med Educ Online. 2013;18:1–8. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v18i0.20699.

Pacala JT, Boult C, Bland C, O'Brien J. Aging game improves medical students’ attitudes toward caring for elders. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 1995;15(4):45–57.

Johnsen K, Lok B. An evaluation of immersive displays for virtual human experiences C3 - Proceedings - IEEE Virtual Reality; 2008.

Potash J, Chen J. Art-mediated peer-to-peer learning of empathy. Clin Teach. 2014;11(5):327–31.

Bunn W, Terpstra J. Cultivating empathy for the mentally ill using simulated auditory hallucinations. Acad Psychiatry. 2009;33(6):457–60. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.33.6.457.

Farnill D, Todisco J, Hayes SC, Bartlett D. Videotaped interviewing of non-English speakers: training for medical students with volunteer clients. Med Educ. 1997;31(2):87–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.1997.tb02464.x.

Potash JS, Chen JY, Lam CL, Chau VT. Art-making in a family medicine clerkship: how does it affect medical student empathy? BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:247.

Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, Suchman AL, Chapman B, Mooney CJ, et al. Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1284–93.

Yu J, Chung Y, Lee JE, Suh DH, Wie JH, Ko HS, et al. The educational effects of a pregnancy simulation in medical/nursing students and professionals. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):168. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1589-8.

Blanco MA, Maderer A, Price LL, Epstein SK, Summergrad P. Efficiency is not enough; you have to prove that you care: role modelling of compassionate care in an innovative resident-as-teacher initiative. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2013;26(1):60–5. https://doi.org/10.4103/1357-6283.112805.

Flint H, Meyer M, Hossain M, Klein M. Discussing serious news. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2017;34(3):254–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909115617140.

Kushner RF, Zeiss DM, Feinglass JM, Yelen M. An obesity educational intervention for medical students addressing weight bias and communication skills using standardized patients. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:53.

Chunharas A, Hetrakul P, Boonyobol R, Udomkitti T, Tassanapitikul T, Wattanasirichaigoon D. Medical students themselves as surrogate patients increased satisfaction, confidence, and performance in practicing injection skill. Med Teach. 2013;35(4):308–13.

Harlak H, Gemalmaz A, Gurel FS, Dereboy C, Ertekin K. Communication skills training: effects on attitudes toward communication skills and empathic tendency. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2008;21(2):62.

Holton-Burke J, Vota S, Oyoung-Oliver D. The addition of virtual reality into the neurology curriculum. Neurology. 2019;92(15 Supplement P2.9-044). https://n.neurology.org/content/92/15_Supplement/P2.9-044/tab-article-info.

Cataldo KP, Peeden K, Geesey ME, Dickerson L. Association between Balint training and physician empathy and work satisfaction. Fam Med. 2005;37(5):328–31.

Ghetti C, Chang J, Gosman G. Burnout, psychological skills, and empathy: balint training in obstetrics and gynecology residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1(2):231–5. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-09-00049.1.

Shapiro J, Hunt L. All the world’s a stage: the use of theatrical performance in medical education. Med Educ. 2003;37(10):922–7.

van Dijk I, Lucassen PLBJ, Akkermans RP, van Engelen BGM, van Weel C, Speckens AEM. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on the mental health of clinical clerkship students: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):1012–21.

Gracia Gozalo RM, Ferrer Tarrés JM, Ayora Ayora A, Alonso Herrero M, Amutio Kareaga A, Ferrer RR. Application of a mindfulness program among healthcare professionals in an intensive care unit: effect on burnout, empathy and self-compassion. Med Int. 2019;43(4):207–16.

Ahmad L, Sawley E, Creasey H. Do informal interviews improve medical student empathy with the elderly? Med Educ. 2005;39(10):1077. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02294.x.

Kirkpatrick D. Evaluation. In: Craig RL, Bittel LR, editors. Training and development handbook. American Society for Training and Development. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1967.

Barr H, Freeth D, Hammick M, Koppel I, Reeves S. London: Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education; 2000. Evaluations of interprofessional education: a United Kingdom review for health and social care. Available from: http://caipe.org.uk/silo/files/evaluations-of-interprofessional-education.pdf.

Harden RM. What is a spiral curriculum? Med Teach. 1999;21(2):141–3.

Davis MH. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1983;44(1):113–26.

Hogan R. Development of an empathy scale. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1969;33(3):307–16.

Mehrabian A. Manual for the Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale (BEES). 1996. (Available from Albert Mehrabian, 1130 Alta Mesa Road, Monterey, CA 93940).

Murphy BA, Lilienfeld SO. Are self-report cognitive empathy ratings valid proxies for cognitive empathy ability? Negligible meta-analytic relations with behavioral task performance. Psychol Assess. 2019;31(8):1062–72.

Lee PT, Loh J, Sng G, Tung J, Yeo KK. Empathy and burnout: a study on residents from a Singapore institution. Singap Med J. 2018;59(1):50–4. https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2017096.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to dedicate this paper to the late Dr. S Radha Krishna whose advice and ideas were integral to the success of this study. The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers whose advice and feedback greatly improved this manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved in data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology and reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

NA

Consent for publication

NA

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

PubMed Search Strategy.

Additional file 2.

Tabulated Summaries.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Y.C., Tan, S.R., Tan, C.G.H. et al. A systematic scoping review of approaches to teaching and assessing empathy in medicine. BMC Med Educ 21, 292 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02697-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02697-6