Abstract

Background

Mentoring provides mentees and mentors with holistic support and research opportunities. Yet, the quality of this support has been called into question amidst suggestions that mentoring is prone to bullying and professional lapses. These concerns jeopardise mentoring’s role in medical schools and demand closer scrutiny.

Methods

To better understand prevailing concerns, a novel approach to systematic scoping reviews (SSR) s is proposed to map prevailing ethical issues in mentoring in an accountable and reproducible manner. Ten members of the research team carried out systematic and independent searches of PubMed, Embase, ERIC, ScienceDirect, Scopus, OpenGrey and Mednar databases. The individual researchers employed ‘negotiated consensual validation’ to determine the final list of articles to be analysed. The reviewers worked in three independent teams. One team summarised the included articles. The other teams employed independent thematic and content analysis respectively. The findings of the three approaches were compared. The themes from non-evidence based and grey literature were also compared with themes from research driven data.

Results

Four thousand six titles were reviewed and 51 full text articles were included. Findings from thematic and content analyses were similar and reflected the tabulated summaries. The themes/categories identified were ethical concerns, predisposing factors and possible solutions at the mentor and mentee, mentoring relationship and/or host organisation level. Ethical concerns were found to stem from issues such as power differentials and lack of motivation whilst predisposing factors comprised of the mentor’s lack of experience and personality conflicts. Possible solutions include better program oversight and the fostering of an effective mentoring environment.

Conclusions

This structured SSR found that ethical issues in mentoring occur as a result of inconducive mentoring environments. As such, further studies and systematic reviews of mentoring structures, cultures and remediation must follow so as to guide host organisations in their endeavour to improve mentoring in medical schools.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mentoring’s success in nurturing “dynamic, context dependent, goal sensitive, mutually beneficial relationships between an experienced clinician and medical students that is focused upon advancing the development of the mentee” has seen its role in medical school education grow [1]. Yet, mentoring has come under increased scrutiny amidst suggestions that mentoring relationships are poorly assessed and supported [2,3,4]. These gaps are seen to aggravate power dynamics between mentee and mentor [2] and predispose to grave issues such as bullying and even sexual harrassment [3, 4]. These reports have curtailed mentoring’s role in medical school education, hampering the provision of personalised, longitudinal and holistic support [5,6,7], career guidance [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15], and research opportunities [16,17,18,19,20,21,22] to medical students.

With mentoring playing a key role in training medical students and with many ethical issues poorly described [2, 23], a systematic scoping review (SSR) is proposed to map prevailing descriptions of ethical issues in mentoring in medical schools to guide a structured and evidence-based response [24,25,26,27,28,29,30].

Methods

An SSR is employed given its wide scope [24]. However, to allow identification of patterns, relationships and disagreements [25] amongst prevailing studies [26], a new approach to SSRs is proposed. Krishna’s novel systematic evidence-based approach (SEBA) seeks to overcome existing concerns over the transparency and reproducibility of SSRs (henceforth SSRs in SEBA). SSRs in SEBA are built upon a constructivist perspective, enabling it to map complex topics from multiple angles [27,28,29]. Acknowledging the impact of the mentee’s, mentor’s and indeed the host organisation’s (henceforth stakeholders) historical, socio-cultural, ideological and contextual circumstances on their individual perspectives [30], SSRs in SEBA employ a relativist lens. This allows the collation of mentoring experiences from a diverse population of stakeholders in order to provide a holistic picture of ethical issues in mentoring in medical schools [27,28,29, 31]. To further enhance the trustworthiness of its synthesis, the research team was supported by medical librarians from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (YLLSoM) at the National University of Singapore and the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS). Advice from local educational experts and clinicians at the NCCS, the Palliative Care Institute Liverpool, YLLSoM and Duke-NUS Medical School (henceforth expert team) was also sought. The expert team was consulted at each stage of the SEBA process. The research team also adopted the principles of interpretivist analysis to immerse themselves in the data. A reflexive attitude towards repeated reading and/or analysis of the quantitative data and group discussions enabled the findings to be pieced together in a more meaningful manner.

The SEBA process comprises of the following stages: 1) Systematic Approach, 2) Split Approach, 3) Jigsaw Perspective, 4) Reiterative Process and 5) Discussion. This is outlined in Fig. 1 and will be further elaborated on.

Stage 1: systematic approach

Determining title and background of review

Ensuring a systematic approach to the SSR in SEBA synthesis, the research team consulted the expert team to determine the overall goals of the SSR and the population, context and particular mentoring approach to be evaluated.

Background of review

Building on findings of two recent systematic scoping reviews [2, 23] of ethical issues in postgraduate and undergraduate mentoring in surgery and medicine, the teams acknowledged that a steeper hierarchy in medical schools see greater power differentials between mentors and mentees as well as the latter’s dependence on the former, thus differentiating ethical issues in medical schools from those affecting doctors.

Identifying research question

Guided by the PCC (population, concept and context) elements of the inclusion criteria [32], the primary research question was determined to be “what is known of ethical issues in mentoring within medical schools?” The secondary research questions were determined to be “what factors precipitate ethical issues in mentoring?” and “what solutions have been offered to address ethical issues in mentoring?”

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are elaborated on below (Table 1).

Types of population, concept and context

The focus was confined to ethical issues in mentoring in undergraduate and postgraduate medical schools.

Searching

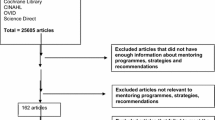

Ten members of the research team carried out independent searches of five bibliographic databases (PubMed, Embase, ERIC, ScienceDirect and Scopus) and two grey literature databases (OpenGrey and Mednar) between 5th March 2020 to 7th March 2020 for articles published between 1st January 2000 to 31st December 2019. The PubMed search strategy may be found in Additional file 1.

Extracting and charting

Ten members of the research team independently reviewed all identified article titles and abstracts, created individual lists of titles to be included and discussed them online where ‘negotiated consensual validation’ [33] was employed to determine the final list of titles to be reviewed. The team then independently reviewed these titles, compared their individual lists of articles to be included and employed ‘negotiated consensual validation’ once more to achieve consensus on the final list of articles to be analysed. This process is outlined in Fig. 2 and the final list of included articles may be found in Additional file 2.

Stage 2: split approach

Three teams comprising of three researchers simultaneously reviewed the 51 included full text articles. The first team independently summarised and tabulated the articles in keeping with Wong and Greenhalgh’s RAMESES publication standards: meta-narrative reviews [34] and Popay et al.’s “Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews” [30]. The final table was then agreed upon. It ensured that key discussion points and contradictory views within the included articles were not lost.

Concurrently, each member of the second team analysed the 51 included articles using Braun and Clarke’s approach to thematic analysis [35] whilst the third team used Hsieh and Shannon’s approach to directed content analysis [36]. A comparison of findings from the thematic analysis, directed content analysis and the tabulated summaries is a hallmark of the ‘Split Approach’ used to enhance their reliability.

Results

Themes identified using thematic analysis

The themes identified were ethical concerns and solutions at the level of the mentee, mentor, mentoring relationship and host organisation.

Categories identified using directed content analysis

Deductive category application [37] was employed in tandem with the categories drawn from Cheong et al.’s systematic scoping review of ethical issues in mentoring in internal medicine, family medicine and academic medicine [23] and Lee et al.’s focus on surgery [2] to discern if any new categories could be identified. No new themes were identified beyond those ascertained from Braun and Clarke’s approach to thematic analysis.

Comparisons between tabulated summaries, thematic analysis and directed content analysis

There was general consensus within the research team and expert team that the findings reflected the positions of the included articles. The combined findings of the Split Approach are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

Stage 3: jigsaw perspective

The jigsaw perspective brings data from complementary pieces of the mentoring process such as aspects of the mentoring relationship together to create a cohesive picture of ethical issues in mentoring.

Stage 4: reiterative process

Whilst there was consensus on the content and arrangement of the themes/categories identified, the expert team raised concerns that data from grey literature, which is neither quality assessed nor necessarily evidence-based, could ‘slant’ the direction of the narrative synthesis. As a result of these concerns, the research team thematically analysed the data from grey literature and non-research-based pieces drawn from the five bibliographic databases. These included letters, opinion and perspective pieces, commentaries and editorials.

Comparisons of themes from grey literature and non-research-based pieces with peer-reviewed evidence-based data revealed that the former two additionally focused on predisposing factors to ethical issues involving mentees, mentors and their mentoring relationships (Table 4).

Stage 5: discussion

It comes as no surprise that ethical concerns surrounding mentoring issues in medical schools remain poorly understood and categorised. In curating and analysing the data, this SSR in SEBA found great diversity in what constitutes ethical issues in mentoring. This ranges from ineffective mentoring support and the misappropriation of the mentee’s work [33, 50,51,52] to suggestions of bullying and potential sexual misconduct [3, 70, 71]. However, despite this diversity, the SSR in SEBA identified patterns and relationships amongst prevailing studies [25, 26]. Indeed, there is consensus amongst the research and expert teams that ethical concerns revolve around and are precipitated by stakeholders and their mentoring relationships. This enabled us to address our research questions:

What is known of ethical issues in mentoring within medical schools?

There appears to be a connection between relatively mild or innocuous issues and severe breaches of professional, ethical and clinical codes of conduct. Without timely and effective interventions, innocuous ethical issues may lead to more serious violations in mentoring practice. Poor access to mentoring support [61] may exacerbate power differentials [33, 50, 55, 64] whilst minor lapses in professionalism [42] and a lack of respect for personal and professional boundaries [38, 47, 68] may precipitate bullying, racism, sexism, misappropriation of the mentee’s work and potential sexual abuse [32, 49,50,51]. Just as concerning is the stiff competition between mentees and mentors for educational and financial resources, with mentors prioritising their own interests over those of their mentees [33, 38, 45, 61, 72].

What factors precipitate these ethical issues?

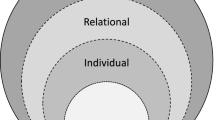

Upon closer analysis of the data, predisposing factors to breaches in ethical mentoring practice may be categorised at the level of the (i) individual mentee and mentor, (ii) mentoring relationship as well as the (iii) host organisation.

At the mentee and mentor level, ethical concerns stem from poor mentee and mentor recruitment and training [33, 40, 44, 47, 50, 52, 58, 62, 73], matching [74], alignment of expectations [40, 44] and oversight and support for the evolving mentoring relationship [57]. These findings highlight three issues. Firstly, mentees and mentors are fundamentally unaware of what is expected of them. Secondly, both groups are not adequately trained to meet their mentoring roles and responsibilities. Thirdly, poor support gives way to communication breakdowns and heightened power dynamics [33, 50, 55, 64], rendering both groups less likely to invest in and sustain their mentoring relationship [39, 43, 49, 63, 75]. Inevitable compromises to the mentoring relationship give rise to significant ethical issues and this failed relationship results in a waste of precious mentoring resources and a missed opportunity for other potential mentees to access the program [39].

At the matching stage, a lack of choice in mentors and poor consideration of mentee preferences for the mentor’s gender, cultural background, experience, interests, personality and working style may have a detrimental effect on the suitability of the mentoring approach and the quality of their interactions [3, 33, 38, 40, 43, 44, 51,52,53,54,55, 63, 66, 76,77,78]. Poor quality interactions may result from personality conflicts, time pressures, a lack of privacy and difficulties in balancing mentoring goals, outcomes, individual interests and institutional objectives [33, 38,39,40,41, 43,44,45,46, 50, 52, 55,56,57,58, 60, 62, 63, 65, 67, 75, 79]. Compromises to the development of trusting and enduring mentoring relationships result in poor mentoring outcomes, experiences and culminate in the program’s overall failure to meet their participants’ needs.

At the level of the host organisation, the primary source of ethical issues in mentoring revolves around poor structuring of the mentoring program which includes the lack of clearly established goals, timelines, project outcomes, mentoring approaches, roles, responsibilities, codes of conduct and expectations upon mentee, mentor and the host organisation at recruitment, training and matching processes. These issues, if insufficiently addressed or supported by the institution, will lead to mentoring failures.

What solutions have been offered to address these concerns?

On deeper consideration of the findings, it could be surmised that the solutions proffered ultimately pivot on the provision of a conducive mentoring environment. To this end, Hee et al. note that an effective mentoring environment comprises of both an efficacious mentoring structure and mentoring culture [80]. The mentoring structure ensures that the various stages of the mentoring process are consistently designed, supported and assessed. This allows for lapses at any stage to be addressed early, minimising the potential snowballing of minor breaches into severe ethical violations. The mentoring culture, in turn, nurtures personal, professional, research, academic, clinical values and behaviours in ways that are consistent with regnant practices and codes of conduct delineated by the respective healthcare and educational systems. It is the mentoring culture that guides mentees, mentors and the host organisation as they navigate through the mentoring process. It informs their decision making within the mentoring relationship and the larger mentoring program.

With the lack of in-depth discussion in prevailing literature on pertinent characteristics of unethical mentoring practice, it is clear that there are no ‘magic bullets’. However, comparing the findings of this SSR in SEBA with existing reviews on mentoring in medicine and surgery [2, 23], it would appear that mentoring in medical schools will benefit from a formal, structured mentoring program overseen by the host organisation. The data suggest that clear guidelines with regards to recruitment, training, matching and the firm delineation of mentee and mentor roles and responsibilities should be established. In addition, Codes of Practice and acceptable parameters should be drawn up and cogently conveyed to all stakeholders. Rigorous, holistic and longitudinal assessments will help to ensure that ethical breaches or violations do not slip through the cracks. In turn, timely, specific, personalised and appropriate support by host organisations will allow mentees to be better protected from many of the ethical issues raised. Suggestions of concrete actions to be taken by the host organisation are outlined in Table 5.

Limitations

Efforts to enhance the reproducibility and transparency of the SSR in SEBA unfortunately appear limited. Whilst the databases used were identified by the expert team, critical papers may still have been omitted despite concerted efforts to employ independent selection processes. Similarly, whilst use of the Split Approach allowed for triangulation and greater transparency of the SSR in SEBA, inherent human biases may have impacted the data analyses. Although use of thematic analysis to review the impact of grey literature also improved the transparency of the discussion, the inclusion of themes derived from grey literature may have skewed the results by providing opinion-based views with a ‘veneer of respectability’ despite a lack of evidence to support them. This raises the question as to whether grey literature should be accorded the same weight as published literature.

Conclusion

In answering its primary and secondary research questions, this SSR in SEBA provides a comprehensive, accountable, reproducible and evidence-based perspective of ethical issues in mentoring in undergraduate and postgraduate medical schools. This SSR in SEBA also identifies the pivotal role of the host organisation in identifying and addressing these concerns.

Further studies on mentoring structures and mentoring cultures are necessary to further guide efforts on how a more gracious and altruistic mentoring environment could be facilitated. Better prevention and remediation of ethical breaches and violations would also certainly help to reinstate mentoring’s role in medical schools. It is only when these concerns are addressed head-on that all stakeholders will be able to truly reap the benefits of mentoring.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- SSR:

-

Systematic Scoping Review

- SEBA:

-

Systematic Evidence-Based Approach

- YLLSoM:

-

Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine

- NCCS:

-

National Cancer Centre Singapore

- PCC:

-

Population Concept Context

- PICOS:

-

Population Intervention Comparison Outcomes Study Design

References

Krishna L, Toh YP, Mason S, Kanesvaran R. Mentoring stages: A study of undergraduate mentoring in palliative medicine in Singapore. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(4):e0214643.

Lee FQH, Chua WJ, Cheong CWS, Tay KT, Hian EKY, Chin AMC, et al. A systematic scoping review of ethical issues in mentoring in surgery. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2019;6:2382120519888915.

Byerley JS. Mentoring in the era of #MeToo. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1199–200.

Grant-Kels JM. Can men mentor women in the# MeToo era? Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018;4(3):179.

Brown RT, Daly BP, Leong FT. Mentoring in research: a developmental approach. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2009;40(3):306.

Crites GE, Gaines JK, Cottrell S, Kalishman S, Gusic M, Mavis B, et al. Medical education scholarship: an introductory guide: AMEE guide no. 89. Med Teach. 2014;36(8):657–74.

Sakushima K, Mishina H, Fukuhara S, Sada K, Koizumi J, Sugioka T, et al. Mentoring the next generation of physician-scientists in Japan: a cross-sectional survey of mentees in six academic medical centers. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:54.

Burnham EL, Schiro S, Fleming M. Mentoring K scholars: strategies to support research mentors. Clin Transl Sci. 2011;4(3):199–203.

Meagher E, Taylor L, Probsfield J, Fleming M. Evaluating research mentors working in the area of clinical translational science: a review of the literature. Clin Transl Sci. 2011;4(5):353–8.

Anderson L, Silet K, Fleming M. Evaluating and giving feedback to mentors: new evidence-based approaches. Clin Transl Sci. 2012;5(1):71–7.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215.

Feldman MD, Steinauer JE, Khalili M, Huang L, Kahn JS, Lee KA, et al. A mentor development program for clinical translational science faculty leads to sustained, improved confidence in mentoring skills. Clin Transl Sci. 2012;5(4):362–7.

Johnson MO, Gandhi M. A mentor training program improves mentoring competency for researchers working with early-career investigators from underrepresented backgrounds. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2015;20(3):683–9.

McGee R. Biomedical workforce diversity: the context for mentoring to develop talents and Foster success within the 'Pipeline'. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(Suppl 2):231–7.

Kirsch JD, Duran A, Kaizer AM, Buum HT, Robiner WN, Weber-Main AM. Career-focused mentoring for early-career clinician educators in academic general internal medicine. Am J Med. 2018;131(11):1387–94.

Cho CS, Ramanan RA, Feldman MD. Defining the ideal qualities of mentorship: a qualitative analysis of the characteristics of outstanding mentors. Am J Med. 2011;124(5):453–8.

Feldman MD, Arean PA, Marshall SJ, Lovett M, O'Sullivan P. Does mentoring matter: results from a survey of faculty mentees at a large health sciences university. Med Educ Online. 2010;15(1):5063.

Ramanan RA, Phillips RS, Davis RB, Silen W, Reede JY. Mentoring in medicine: keys to satisfaction. Am J Med. 2002;112(4):336–41.

Shea JA, Stern DT, Klotman PE, Clayton CP, O'Hara JL, Feldman MD, et al. Career development of physician scientists: a survey of leaders in academic medicine. Am J Med. 2011;124(8):779–87.

Garman KA, Wingard DL, Reznik V. Development of junior faculty's self-efficacy: outcomes of a National Center of leadership in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2001;76(10 Suppl):S74–6.

Palepu A, Friedman RH, Barnett RC, Carr PL, Ash AS, Szalacha L, et al. Junior faculty members' mentoring relationships and their professional development in U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 1998;73(3):318–23.

Pfund C, Byars-Winston A, Branchaw J, Hurtado S, Eagan K. Defining attributes and metrics of effective research mentoring relationships. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(Suppl 2):238–48.

Cheong CWS, Chia EWY, Tay KT, Chua WJ, Lee FQH, Koh EYH, et al. A systematic scoping review of ethical issues in mentoring in internal medicine, family medicine and academic medicine. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2019;25(2):415–39.

Hinchcliff R, Greenfield D, Moldovan M, Westbrook JI, Pawsey M, Mumford V, et al. Narrative synthesis of health service accreditation literature. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(12):979–91.

Davey S, Davey A, Singh J. Metanarrative review: current status and opportunities for public health research. Int J Health Syst Disaster Manag. 2013;1(2):59–63.

Greenhalgh T, Wong G. Training materials for meta-narrative reviews. UK: Global Health Innovation and Policy Unit Centre for Primary Care and Public Health Blizard Institute, Queen Mary University of London; 2013.

Crotty M. The foundations of social research: meaning and perspective in the research process. UK: SAGE; 1998.

Pring R. The ‘false dualism’of educational research. J Philos Educ. 2000;34(2):247–60.

Ford K. Taking a narrative turn: Possibilities, challenges and potential outcomes. OnCue J. 2011;6(1):23–36.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. Prod ESRC Methods Programme Version. 2006;1:b92.

Schick-Makaroff K, MacDonald M, Plummer M, Burgess J, Neander W. What synthesis methodology should I use? A review and analysis of approaches to research synthesis. AIMS Public Health. 2016;3:172–215.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H. McInerne yP, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–6.

Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):72–8.

Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Buckingham J, Pawson R. RAMESES publication standards: meta-narrative reviews. BMC Med. 2013;11(1):20.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88.

Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–15.

Sanfey H, Hollands C, Gantt NL. Strategies for building an effective mentoring relationship. Am J Surg. 2013;206(5):714–8.

Stenfors-Hayes T, Kalen S, Hult H, Dahlgren LO, Hindbeck H, Ponzer S. Being a mentor for undergraduate medical students enhances personal and professional development. Med Teach. 2010;32(2):148–53.

Barker JC, Rendon J, Janis JE. Medical student mentorship in plastic surgery: the Mentee’s perspective. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(6):1934–42.

Bhatia A, Singh N, Dhaliwal U. Mentoring for first year medical students: humanising medical education. Indian J Med Ethics. 2013;10(2):100–3.

Piemonte NM. Last laughs: gallows humor and medical education. J Med Humanit. 2015;36(4):375–90.

Healy NA, Cantillon P, Malone C, Kerin MJ. Role models and mentors in surgery. Am J Surg. 2012;204(2):256–61.

Janis JE, Barker JC. Medical Student Mentorship in Plastic Surgery: The Mentor’s Perspective. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 2016;138(5):925e–35e.

Straus SE, Johnson MO, Marquez C, Feldman MD. Characteristics of successful and failed mentoring relationships: a qualitative study across two academic health centers. Acad Med. 2013;88(1):82–9.

Konstantakos AK. Surgical education and the mentor-student relationship. Curr Surg. 2003;60(5):547–8.

Sawatsky A, Parekh N, Muula A, Mbata I, Bui T. Cultural implications of mentoring in sub-Saharan Africa: a qualitative study. Med Educ. 2016;50:657–69.

Hansman CA. Diversity and power in mentoring relationships; 2002.

Goldie J, Dowie A, Goldie A, Cotton P, Morrison J. What makes a good clinical student and teacher? An exploratory study. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:40.

Keyser DJ, Lakoski JM, Lara-Cinisomo S, Schultz DJ, Williams VL, Zellers DF, et al. Advancing institutional efforts to support research mentorship: a conceptual framework and self-assessment tool. Acad Med. 2008;83(3):217–25.

Rose GL, Rukstalis MR, Schuckit MA. Informal mentoring between faculty and medical students. Acad Med. 2005;80(4):344–8.

Garmel GM. Mentoring medical students in academic emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(12):1351–7.

Dixon A, Silva NA, Sotayo A, Mazzola CA. Female medical student retention in neurosurgery: a multifaceted approach. World Neurosurg. 2019;122:245–51.

Henry-Noel N, Bishop M, Gwede CK, Petkova E, Szumacher E. Mentorship in medicine and other health professions. J Cancer Educ. 2019;34(4):629–37.

Zerzan JT, Hess R, Schur E, Phillips RS, Rigotti N. Making the most of mentors: a guide for mentees. Acad Med. 2009;84(1):140–4.

Kadom N, Tigges S, Wagner SB, Vey BL, Straus CM. Research mentoring of medical students: a win-win. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15(12):1771–4.

Frei E, Stamm M, Buddeberg-Fischer B. Mentoring programs for medical students - a review of the PubMed literature 2000-2008. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:32.

Cloyd J, Holtzman D, O'Sullivan P, Sammann A, Tendick F, Ascher N. Operating room assist: surgical mentorship and operating room experience for Preclerkship medical students. J Surg Educ. 2008;65(4):275–82.

Macaulay W, Mellman LA, Quest DO, Nichols GL, Haddad J Jr, Puchner PJ. The advisory dean program: a personalized approach to academic and career advising for medical students. Acad Med. 2007;82(7):718–22.

Dobie S, Smith S, Robins L. How assigned faculty mentors view their mentoring relationships: an interview study of mentors in medical education. Mentoring Tutoring Partnership Learn. 2010;18(4):337–59.

Sng JH, Pei Y, Toh YP, Peh TY, Neo SH, Krishna LKR. Mentoring relationships between senior physicians and junior doctors and/or medical students: a thematic review. Med Teach. 2017;39(8):866–75.

Tan YS, Teo SWA, Pei Y, Sng JH, Yap HW, Toh YP, et al. A framework for mentoring of medical students: thematic analysis of mentoring programmes between 2000 and 2015. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2018;23(4):671–97.

Kalén S, Stenfors-Hayes T, Hylin U, Larm MF, Hindbeck H, Ponzer S. Mentoring medical students during clinical courses: a way to enhance professional development. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):e315–e21.

Nguyen SQ, Divino CM. Surgical residents as medical student mentors. Am J Surg. 2007;193(1):90–3.

Alleyne SD, Horner MS, Walter G, Hall Fleisher S, Arzubi E, Martin A. Mentors' perspectives on group mentorship: a descriptive study of two programs in child and adolescent psychiatry. Acad Psychiatry. 2009;33(5):377–82.

Bettis J, Thrush CR, Slotcavage RL, Stephenson K, Petersen E, Kimbrough MK. What makes them different? An exploration of mentoring for female faculty, residents, and medical students pursuing a career in surgery. Am J Surg. 2019;218(4):767–71.

Sobbing J, Duong J, Dong F, Grainger D. Residents as medical student mentors during an obstetrics and gynecology clerkship. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(3):412–6.

Usmani A, Omaeer Q, Sultan ST. Mentoring undergraduate medical students: experience from Bahria University Karachi. J Pak Med Assoc. 2011;61(8):790–4.

Schäfer M, Pander T, Pinilla S, Fischer MR, von der Borch P, Dimitriadis K. The Munich-evaluation-of-mentoring-questionnaire (MEMeQ) – a novel instrument for evaluating protégés’ satisfaction with mentoring relationships in medical education. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):201.

Singh MD, Pilkington FB, Patrick L. Empowerment and mentoring in nursing academia. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2014;11(1):101–11.

Soklaridis S, Zahn C, Kuper A, Gillis D, Taylor VH, Whitehead C. Men's fear of mentoring in the #MeToo era - What's at stake for academic medicine? N Engl J Med. 2018;379(23):2270–4.

Liang TJ. Odysseus's lament: death of mentor. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(6):1429.

Hauer KE, Teherani A, Dechet A, Aagaard EM. Medical students’ perceptions of mentoring: a focus-group analysis. Med Teach. 2005;27(8):732–4.

Lin CD, Lin BY, Lin CC, Lee CC. Redesigning a clinical mentoring program for improved outcomes in the clinical training of clerks. Med Educ Online. 2015;20:28327.

Usmani A, Sultan S, Omaeer Q. PAKISTAN: Ethical implications in mentoring medical students - Asian Human Rights Commission [Internet]. Asian Human Rights Commission. 2020. [cited 15 April 2020]. Available from: http://www.humanrights.asia/opinions/columns/AHRC-ETC-019-2011.

Edmunds LD, Ovseiko PV, Shepperd S, Greenhalgh T, Frith P, Roberts NW, et al. Why do women choose or reject careers in academic medicine? A narrative review of empirical evidence. Lancet. 2016;388(10062):2948–58.

Earp BE, Rozental TD. Expanding the Orthopaedic Pipeline: The B.O.N.E.S. Initiative. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(3):704-9.

Luc JGY, Stamp NL, Antonoff MB. Social media in the mentorship and networking of physicians: important role for women in surgical specialties. Am J Surg. 2018;215(4):752–60.

Devi V, Abraham RR, Adiga A, Ramnarayan K, Kamath A. Fostering research skills in undergraduate medical students through mentored students projects: example from an Indian medical school. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2010;8(31):294–8.

Hee JM, Yap HW, Ong ZX, Quek SQM, Toh YP, Mason S, et al. Understanding the mentoring environment through thematic analysis of the learning environment in medical education: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(10):2190–9.

Kalen S, Ponzer S, Silen C. The core of mentorship: medical students' experiences of one-to-one mentoring in a clinical environment. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2012;17(3):389–401.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to dedicate this paper to the late Dr. S Radha Krishna whose advice and ideas were integral to the success of this study. The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers whose advice and feedback greatly improved this manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CSK was involved in data curation, formal analysis, investigation, preparing the original draft of the manuscript as well as reviewing and editing the manuscript. YHT, YNT, KCZY, QLYE were involved in data curation, formal analysis and investigation. NHBAK was involved in data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology. LHET was involved in data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology and reviewing and editing the manuscript. CWSC was involved in data curation, formal analysis, investigation, and reviewing and editing the manuscript. YTO, KTT, MC were involved in reviewing and editing the manuscript. SM was involved in project administration, supervision and reviewing and editing the manuscript. LKRK was involved in conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, and reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

NA

Consent for publication

NA

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Search Strategy, which shows Search Strategy employed for PubMed.

Additional file 2.

Summary of Included Articles, which shows Summary of Included Articles.

Additional file 3.

PRISMA Checklist.doc, PRISMA Checklist, which shows the PRISMA checklist for this review.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kow, C.S., Teo, Y.H., Teo, Y.N. et al. A systematic scoping review of ethical issues in mentoring in medical schools. BMC Med Educ 20, 246 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02169-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02169-3