Abstract

Background

Effective Interprofessional Communication (IPC) between healthcare professionals enhances teamwork and improves patient care. Yet IPC training remains poorly structured in medical schools. To address this gap, a scoping review is proposed to study current IPC training approaches in medical schools.

Methods

Krishna’s Systematic Evidence Based Approach (SEBA) was used to guide a scoping review of IPC training for medical students published between 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2018 in PubMed, ScienceDirect, JSTOR, Google Scholar, ERIC, Embase, Scopus and PsycINFO. The data accrued was independently analysed using thematic and content analysis to enhance the reproducibility and transparency of this SEBA guided review.

Results

17,809 titles and abstracts were found, 250 full-text articles were reviewed and 73 full text articles were included. Directed Content analysis revealed 4 categories corresponding to the levels of the Miller’s Pyramid whilst thematic analysis revealed 5 themes including the indications, stages of trainings and evaluations, content, challenges and outcomes of IPC training. Many longitudinal programs were designed around the levels of Miller’s Pyramid.

Conclusion

IPC training is a stage-wise, competency-based learning process that pivots on a learner-centric spiralled curriculum. Progress from one stage to the next requires attainment of the particular competencies within each stage of the training process. Whilst further studies into the dynamics of IPC interactions, assessment methods and structuring of these programs are required, we forward an evidenced based framework to guide design of future IPC programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Effective interprofessional communication (IPC) between healthcare professionals promotes teamwork, improves patient care and boosts cost efficiency [1, 2]. IPC also encourages open, honest and frank discussions, facilitates negotiations and resolution of conflicts, and promotes shared decision making [3]. These features foster coordinated medical, nursing, social, psychological and financial support by different members of the interprofessional team and contribute to holistic and longitudinal patient-centric care [4].

Yet, whilst medical schools have not been slow to recognise the importance of IPC training or equip its students to meet the IPC competencies set out by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and the World Health Organisation’s Framework for Action on International Education & Collaborative Practice, significant diversity in the approaches and structuring of current IPC training in medical schools have been observed [5]. These variations create concern about the ability of medical students to function effectively in interprofessional teams upon graduation [6,7,8].

The need for this review

To advance a consistent approach to IPC skills training in medical schools, a scoping review of current practice is proposed [9]. With most programs seen to be designed around the different levels of Miller’s pyramid this scoping review will frame it approach accordingly [6,7,8]. In addition, this scoping review will adopt a constructivist perspective and a relativist lens to capture IPC’s socioculturally-sensitive, linguistically-dependent, context and user-specific nature [10, 11] across different education and healthcare systems [12,13,14,15,16].

Methods

A scoping review allows for the summarizing [17] of current approaches, pedagogies, assessments, and practice settings employed [18,19,20] in peer-reviewed and grey literature [12,13,14,15,16] and the circumnavigation of inevitable differences in practice, healthcare, education and healthcare financing across the different programs.

To guide this scoping review, we adopt Krishna’s Systematic Evidenced Based Approach [21, 22] (henceforth SEBA) to enhance transparency and reproducibility of the scoping review (Fig. 1). To begin SEBA employs an expert team comprising of local clinicians, educators, researchers, and a medical librarian to determine the research question and guide the scope of the review. SEBA structures its search process by adopting the approach used in systematic reviews. To enhance transparency of the review process SEBA uses trained researchers to carry independent searches for data across the selected databases including grey literature. These individual researchers use consensus based decisions to determine the final list of included articles. Independent reviews and consensus based determinations are also a part of SEBA’s ‘split approach’ which sees the concurrent use of thematic and content analysis of the data. The research team guided by the expert team review the findings and make comparisons of the findings with current available data as part of the reiterative process and the synthesis of the scoping review. SEBA also sees the employ of the PICO search strategy protocol and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols (PRISMA-P) checklist [23]. SEBA also incorporates Levac et al. (2015) [24]‘s methodology for scoping reviews.

Stage 1. Defining the research question and scope

Guided by the expert team, the research team identified the primary research question to be: “what are the characteristics of prevailing IPC programs?” The secondary research questions are: “what are the indications, training and evaluation methods, content, challenges and outcomes of these IPC programs?”

These questions were designed based on the population and concept elements of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, which are presented via a PICOS format in Table 1 [25]. For practical reasons, the ‘members’ of the IPC are drawn from a ‘small Multi-Disciplinary Team’ (MDT) which includes members from the faculties of medicine, nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy and social work [26]. Articles involving IPC training programs for medical students including healthcare professionals and or students from nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy and social work, were reviewed.

Stage 2. Independent searches

Under the guidance of the expert team, search strategies (Supplementary File 1) were formulated with the following keywords: ‘medical students’, ‘nursing students’, ‘allied health students’, ‘interprofessional’, ‘communication’ and ‘education’. In keeping with Pham, Rajić [27]‘s approach to ensuring a viable and sustainable research process, the research team confined the searches to articles published between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2018.

Seven trained researchers carried out independent searches of PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, Scopus, PsycINFO, ERIC, JSTOR, and Google Scholar databases and created independent lists of titles and abstracts to be scrutinized further based on the screening criteria as detailed in Table 1. The researchers discussed their findings at online meetings and determined the final list of full text articles to be reviewed using Sandelowski M [28]‘s ‘negotiated consensual validation’ approach.

Selection of studies for review

The final list full text articles was independently scrutinised by members of the research team and discussed their findings at online meetings. The research team determined the final list of full text articles to be analysed using Sandelowski M [28]‘s ‘negotiated consensual validation’ approach. Figure 2 shows a summary of the PRISMA process.

Stage 3. Data characterization and Split approach [21, 22, 29]

Inspired by the notion that communication skills training is a longitudinal process that develops in competency based stages, Hsieh and Shannon’s directed content analysis was adopted [30]. The codes and categories for this content analysis was drawn from various stages of the Miller’s Pyramid [6,7,8]. Miller’s Pyramid serves as an influential conceptual framework for the development and assessment of clinical competence, one which sees learners move from cognitive acquisition of knowledge to applied behaviour in clinical settings where beneficiaries reside. Critically an initial review of prevailing programs suggest that many IPC programs appear to fashion their programs around the 4 levels of Miller’s Pyramid [6,7,8] which are ‘Knows’ – which requires the learner to be aware of knowledge and skills, ‘Knows How’ – which sees the learner apply these knowledge and skills in theory, ‘Shows How’ – where knowledge and skills are applied in practice, and ‘Does’ – where the learner is shown to be able to function independently in the clinical setting [31].

The decision to adopt content analysis was not unanimous precipitating the employ of the ‘split approach’. The decision to adopt Braun and Clarke’s approach to thematic analysis [26] gained traction following the findings of the deductive category application. Part of the directed content analysis, the deductive category application suggested the presence of a number of other categories not related to the 4 levels of Miller’s Pyramid. These include the indications, structure, content, assessments and obstacles to IPC programs [14]. Omission of these critical categories and the belief that the adoption of predetermined categories based on Miller’s Pyramid required further evidencing, underpinned the decision to adopt Krishna’s ‘Split Approach’ [23,24,25,26].

The ‘Split Approach’ [29] sees two independent teams carry out concurrent reviews of the data using Hsieh and Shannon’s directed content analysis [30] and Braun and Clarke’s approach to thematic analysis [26]. This saw two members of the research team carry out concurrent and independent analyses of the data using Hsieh and Shannon’s directed content analysis [30] and three other members of the research team carry out simultaneous and independent analysis of the data using Braun and Clarke’s approach to thematic analysis [26]. The findings were discussed within each sub-team at online and face-to-face meetings where “negotiated consensual validation” was employed to determine the final list of themes and categories [32,33,34]. The themes from Braun and Clarke’s approach to thematic analysis [26] and the categories from Hsieh and Shannon’s directed content analysis [30] were compared [29].

Stage 4. Review of results and comparing them with current data

Using PRISMA guidelines (Fig. 2), an initial search in eight databases revealed 17,809 titles and abstracts after removal of duplicates. Two hundred and fifty full-text articles were reviewed and a total of 73 articles were included for analysis. The narratives were written according to the Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) Collaboration guide [35] and the STORIES (STructured apprOach to the Reporting In healthcare education of Evidence Synthesis) statement [36].

Scrutiny of the themes identified from the employ of Braun and Clarke’s approach to thematic analysis [26] and the categories identified from Hsieh and Shannon’s directed content analysis [30] were found to be overlap in some areas [29]. In addition the 5 themes identified using Braun and Clarke’s approach to thematic analysis [26] which were the indications, stages of trainings and evaluations, content, challenges and outcomes of IPC training were similar to the categories identified using Hsieh and Shannon’s directed content analysis [30]. This allowed the themes and categories to be presented together.

-

a.

Indications for IPC programs

The indications for the development of IPC programs are outlined in Table 2. Most accounts sought to assess perspectives towards Interprofessional work and communication, to introduce the use of IPC amongst medical students, to assess the nature of these interactions, determine roles and responsibilities of tutors and students in IPC, to better understand the process of problem solving and teamwork, to scrutinize the decision making processes that occurred in collaborations and evaluate the impact of debriefs and feedback sessions following IPC sessions. Many of these interactions took place in case discussions, simulations and or clinical practice and involved medical students in pre-clinical and clinical postings. Other accounts focused upon training faculty on teaching, facilitating IPC, setting and evaluating clinical competencies and debriefs and reports of IPC programs.

-

b.

Stages of IPC training

Whilst there were accounts that assessed a specific aspect of the IPC process or involved ‘snap shots’ of the IPC process and interactions, accounts of IPC that took a longitudinal perspective of IPC did consider the development of IPC along the 4 levels of Miller’s Pyramid (Fig. 3) [6, 8, 38, 39]. As a result, we present the themes/categories related to each level of Miller’s Pyramid.

Level 1: knows

Training

Forming the base of the pyramid, the “Knows” level of Miller’s Pyramid focuses on the acquisition of theoretical concepts and skills. IPC training at this level Miller’s Pyramid [6, 8, 38, 39] were part of formal programs. This includes the provision videos, lectures and briefings [40,41,42,43,44,45,46], online courses, didactic lectures and workshops [40, 47,48,49,50,51,52,53], seminars and conferences [44, 54,55,56] and even a ‘Healthcare Interprofessional Education Day’ where there opportunities to clarify interprofessional roles and markers of proficiency [57]. IPC training at this level also took place as part of observations of interactions between the healthcare team, role modelled in multidisciplinary settings [58,59,60,61,62].

Evaluation

Evaluations at this level of Miller’s Pyramid include self-reported surveys which incorporated checklists, open-ended questions and Likert scales that assessed perception of their own knowledge [40, 43, 47, 50, 54, 55, 57, 59, 63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86]. Focused group discussions [59, 87, 88] and semi-structured interviews were also carried out by faculty members to grade students on their ability to demonstrate their knowledge [52, 64, 65, 89,90,91,92]. Only the Mayo High Performance Teamwork Scale [49], the Scope of Practice Checklist [64], Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale [93], Conceptions of Learning and Knowledge Questionnaire [94] as well as a purpose-designed questionnaire in Jakobsen, Gran [95]‘s study.

Level 2: knows how

Training

To achieve the “Knows How” level of Miller’s Pyramid, emphasis was placed on problem-based discussions [49, 53, 56, 65,66,67,68,69, 96,97,98,99,100,101,102].

Evaluation

Students were asked to reflect on their IPC experiences [45, 56, 62, 72, 103]. In Robertson, Kaplan [104]‘s program, they were asked to point out positive IPC skills demonstrated in a video and suggest areas for improvement.

Level 3: shows how

Training

The third level of Miller’s pyramid comprises of “Shows How”, where students are required to demonstrate the application of knowledge in their clinical performance. Clinical scenarios included cardiac resuscitations [52, 65, 81, 102]; handoffs [105]; mock pages [41, 106]; communication with a senior clinician [107]; interactions with simulated patients [40, 44, 50, 92, 105] and manikins [46, 49, 73, 74, 76, 95, 108, 109]; simulated ward rounds [43, 45, 48, 51, 71, 110], family meetings [47], roleplay [100, 104]; paediatric clinical simulations [75]; Objective Structured Clinical Exam simulations [111] and laboratory sessions [101]. Non-clinical scenarios incorporated the handling of difficult family conflicts [92] and sensitive cultural issues [92].

Evaluation

Student evaluations were carried out by faculty members [65, 69, 77, 99, 105, 108], and supplemented by feedback from simulated patients [49, 97, 99], and team building exercises [97]. A post-training analysis of verbal units of exchange during handoffs also served to quantify improvements in communication skills [105]. Once again only the Mayo High Performance Teamwork Scale [49], the University of West England Interprofessional Questionnaire [89], the Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale [65] and the Interprofessional Collaborative Competency Attainment Survey [57] and the I-PASS: Medical Student Workshop [105] were validated.

Level 4: does

Training

At the apex of the pyramid, the “Does” level focuses on the students’ independent performance in real clinical settings. IPC training was facilitated via experiential learning in clinics [53, 70, 80, 83, 93, 103, 112] and wards [80, 83, 85, 93], student-led clinics [82, 88,89,90], motivational interviews with certified health educationalists [99] and home visits [78, 91, 113]. These interactions provide opportunities for students to share disciplinary insights and expertise, conduct collaborative medical interviews, explore complex patient cases and manage challenging situations as a unified group [78, 91].

Evaluation

Whilst students provided self-reports of their competency levels in clinical settings via questionnaires [79, 89, 96], faculty members [99] and patients [60, 70] were also involved in the observation and identification of good communication skills. Few tools were validated [89, 99] such as the University of West England Interprofessional Questionnaire [89], and the Indiana University Individual Communication Rubric and Indiana University Team Communication Rubric which were modifications of the validated Indiana University Simulation Integration Rubric [99].

Attitudes

Acknowledging that IPC experiences and professional and personal development change individual concepts [40, 42, 49, 64, 69, 71, 106, 108], a combination of validated and unvalidated questionnaires, checklists, interviews and reflective pieces were employed to determine prevailing attitudes towards IPC [44, 47, 50, 51, 53, 55, 58, 59, 61, 66,67,68, 73,74,75,76,77, 80, 82,83,84, 86,87,88,89, 91, 93, 95, 98, 101, 102, 104, 109, 112].

Suitability of teaching and evaluation methods

It is of note that across the 73 included studies, only 14 studies [46, 52, 62, 72, 78, 80, 85, 89, 97, 99, 101, 102, 108, 109, 111, 114] offered evaluation methods that appropriately evaluated learning outcomes in a stepwise approach as delineated by the stage(s) of Miller’s pyramid.

Thirty four studies, studied improvements in attitudes towards IPC or satisfaction with training in lieu of assessing any stage in Miller’s pyramid of competency, or, had conducted no assessment [42, 44, 47, 48, 50, 53,54,55, 58, 59, 61, 67, 68, 71, 73,74,75,76, 81,82,83, 86,87,88, 90,91,92, 98, 100, 101, 106, 110, 112, 113].

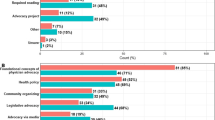

Content of IPC programs

Table 3 describes the list of topics covered in IPC programs. Most interventions were centred around clinical scenarios in various settings, deliberation of ethical issues and care determinations.

Challenges to IPC training

Challenges to IPC training include scheduling conflicts, difficulties in preparing effective and appropriate programs, obstacles in recruiting [108] and training [72] teachers [56, 80] and students [46, 54, 76, 78]. A further issue is failure to vertically integrate IPC training which has been found to reduce teamwork and collaboration and stunt professional identity [93].

Yet perhaps less evident but nonetheless as concerning is the lack of longitudinal assessment of the IPC interactions [48, 57, 65]. Only one account amongst the 74 included studies employed a longitudinal assessment approach [90].

Outcomes of IPC training

A lack of longitudinal assessments limit outcome measures to self-reported increases in understanding and appreciation of IPC [40, 55, 63, 64, 70, 72, 73, 84,85,86, 91, 107, 112], self-perceived improvements in teamwork [49, 97, 99], communication techniques [107] and clinical communication [49, 97, 99], self-reported improvements in IPC competency [87, 107] and the belief that they would better able to adapt to future practice [40, 47, 51, 57, 59, 62, 63, 66, 70,71,72, 74, 76, 78, 98, 102, 103, 107, 108].

Critically M. Amerongen, Legros [64], Berger, Mahler [54], Bradley, Cooper [65], Erickson, Blackhall [47], Robertson, Kaplan [104] found that efforts to instil IPC did not result in statistically significant improvements in IPC competencies and attitudes [47, 54, 64, 65, 104]. Bradley, Cooper [65] reported that scores for collaboration decreased three to four months post IPC training. Some have sought to attribute these poor results to cognitive overload [42], a ceiling effect [47] and the need for more training [47]. Concurrently initial discomfort [50] with this communication approach could be countered by continued collaborative work [52, 76, 93] with other healthcare professionals [58, 66, 70, 91, 108].

Stage 5. Consultations with key stakeholders and synthesis of discussion

Consultations with the expert team and local educators, clinicians and researchers well-versed in IPC training revealed was particularly insightful. To begin these discussions following the review of the omitted data identified through deductive category application [14] and the belief that adopting categories based on Miller’s Pyramid required evidencing, underpinned the decision to adopt Krishna’s ‘Split Approach’ [23,24,25,26]. This led to the shift from use of Levac et al. (2015) [24]‘s methodology to scoping reviews to adoption first of the split approach and then the integration of a more structured methodology in the form of a SEBA guided approach to SRs following comments by the journal’s anonymous reviewers.

Discussions with the expert teams and local educators, clinicians and researchers also revealed general consensus that the results of this review aligned with prevailing understandings of IPC programs. It was also agreed upon that there is an urgent need for further research on the impact of IPC training on interprofessional collaborations and in the design of comprehensive and longitudinal training and evaluation programs for medical students.

Discussion

In addressing its research questions, this scoping review revealed diverse approaches, learning objectives, and methods of assessing IPC in medical schools contribute to the poor alignment of training goals and the desire for a step-wise competency framework [6, 8, 39]. Forty five of the included accounts focused on just one level of the Miller’s pyramid, 23 studies focused on two levels whilst 5 studies considered three levels of Miller’s Pyramid. Critically 59 studies employed inappropriate assessments methods to assess the level of the Miller’s Pyramid employed in their program [115].

Whilst we acknowledge that Miller’s Pyramid is by no means the definitive framework to be used in IPC training, it provides a sound, foundational, learner-centric, progressive scaffolding for the effective acquisition and assimilation of IPC knowledge and skills. There is sufficient data to suggest that IPC programs is best ‘spiralled’ – bearing both vertical and horizontal integration within the curriculum. Whilst each stage builds upon prior core topics, knowledge and skills in a vertical manner, they must also work in tandem horizontally with the wider medical school curricula to ensure that students are equipped with other imperative skills which would adequately prepare them for simulations and clinical placements within their IPC training [116, 117]. This would enable the students to see the interwoven nature of specific cognitive and procedural knowledge and skills across settings, allowing for more judicious decision-making and cohesive interprofessional collaborations.

Likewise, training and evaluation methods must be strategically curated and complementary with this stage-wise curriculum. Evaluations must be longitudinal, holistic, multi-sourced and allow for faculty members to quickly identify areas for remediation. Thus competencies must have both fixed elements and personalised components to contend with the individual needs, abilities and contextual considerations. To this end, portfolios are recommended as a suitable learning and evaluation tool to accompany students as they hone their IPC skills [118,119,120]. Extensive follow-ups assessing attitudinal and behaviour change [121, 122] should also be conducted following graduation to determine the overall impact of the curriculum on IPC skills into the clinical setting [107].

Limitations

While it is reassuring that Millers’ Pyramid may be used to address present gaps in IPC training, there are a number of limitations to be broached.

First, drawing from a small pool of papers which were limited to articles published or translated to the English language can be problematic particularly when most are North American and European-centric. This may limit the applicability of the findings in wider healthcare settings.

Two, there is much to be clarified about the IPC training and assessment processes. This endeavor is set back, however, by a lack of holistic and longitudinal assessments and the continued reliance upon assessment tools still rooted in “Cartesian reductionism and Newtonian principles of linearity” [123] and fail to consider the evolving nature of the IPC training process and training environment [49, 57, 65].

Three, despite our independent efforts to carry out our searches and independent efforts to verify our searches and consolidate our findings there may still be important articles that have been omitted.

Conclusion

This scoping review finds that despite efforts to design IPC programs around competency-based stages, most programs lack a longitudinal perspective and effective means of appraising competency. Yet it is still possible to forward a basic framework for the design of IPC programs.

Acknowledging the need for a longitudinal perspective IPC training should be structured around a ‘spiralled’ curriculum. This facilitates both vertical and horizontal integrations within the formal medical training curriculum. Being part of the formal curriculum will also cement IPC as part of the core training processes in medical school and facilitates the recruitment and training of trainers, established purpose built training slots over the course of medical training program, financial support and effective oversight of the program and the training environment. With more medical schools adopting a portfolio-based assessment process, IPC would be furnished with a clear means of longitudinal assessments of IPC competencies over the course of each competency-based stage. It also allows effective follow up of graduates and a link with postgraduate training processes and portfolios.

The program itself must involve all 4 levels of Miller’s Pyramid [6, 8, 38, 39]. For Level 1 of Miller’s Pyramid, a combination of interactive workshops and role modelling of effective IPC in the clinical setting will help medical students appreciate the role of IPC.

Level 2 should involve case based discussions on ethical and care issues in the interprofessional setting whilst Level 3 and 4 may be demonstrated in simulated clinics and ward rounds. Perhaps just as critical is that IPC practice should be regularly assessed in all clinical postings to ensure that remediation can be carried out early.

Being part of the formal curriculum will also ensure that there are quality appraisals of the IPC program and policing of codes of conduct and practice standards. It will also facilitate research into better assessment measures and tools, communication dynamics and the professional identity formation. Finally, it will also evaluate the translatability of these findings beyond medical schools and their links to postgraduate practice.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article under Table 2 Indications for an IPC Programme.

Abbreviations

- IPC:

-

Interprofessional collaboration

- IPE:

-

Interprofessional education

- MDT:

-

Multi-Disciplinary Team

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

References

Shamian J, El-Jardali F. Healthy Workplaces for Health Workers in Canada: Knowledge Transfer and Uptake in Policy and Practice. HealthcarePapers. 2007;7 Spec No:6–25.

Foronda C, MacWilliams B, McArthur E. Interprofessional communication in healthcare: An integrative review. Nurse Educ Pract. 2016;19:36–40.

Thistlethwaite J, Moran M, World Health Organization Study Group on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. Learning outcomes for interprofessional education (IPE): Literature review and synthesis. J Interprof Care. 2010;24(5):503–13.

Wijlhuizen GJ, Perenboom RJ, Garre FG, Heerkens YF, van Meeteren N. Impact of multimorbidity on functioning: evaluating the ICF core set approach in an empirical study of people with rheumatic diseases. J Rehabil Med. 2012;44(8):664–8.

World Health Organization. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. World Health Organization; 2010.

Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Amending Miller's pyramid to include professional identity formation. Acad Med. 2016;91(2):180–5.

Al-Eraky M, Marei H. A fresh look at Miller's pyramid: assessment at the ‘is’ and ‘do’ levels. Med Educ. 2016;50(12):1253–7.

Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65(9 Suppl):S63–7.

Mauksch L, Farber S, Greer H. Design, dissemination, and evaluation of an advanced communication elective at seven U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 2013;88(6):843–51.

Horsley T. Tips for improving the writing and reporting quality of systematic, scoping, and narrative reviews. J Contin Educ Heal Prof. 2019;39(1):54–7.

Munn Z, Peters MD, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143.

Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inform Libraries J. 2009;26(2):91–108.

Lorenzetti DL, Powelson SE. A scoping review of mentoring programs for academic librarians. J Acad Librariansh. 2015;41(2):186–96.

Mays N, Roberts E, Popay J. In: Fulop N, Allen P, Clarke A, Black N, editors. Synthesising research evidence. Studying the organization and delivery of health services: research methods. London: Routledge; 2001.

Thomas A, Menon A, Boruff J, Rodriguez AM, Ahmed S. Applications of social constructivist learning theories in knowledge translation for healthcare professionals: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):54.

Du Mont J, Macdonald S, Kosa D, Elliot S, Spencer C, Yaffe M. Development of a comprehensive hospital-based elder abuse intervention: an initial systematic scoping review. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125105.

Blondon KS, Maitre F, Muller-Juge V, Bochatay N, Cullati S, Hudelson P, et al. Interprofessional collaborative reasoning by residents and nurses in internal medicine: Evidence from a simulation study. 2017 (1466-187X (Electronic)).

Bays AM, Engelberg RA, Back AL, Ford DW, Downey L, Shannon SE, Doorenbos AZ, Edlund B, Christianson P, Arnold RW, O'Connor K. Interprofessional communication skills training for serious illness: evaluation of a small-group, simulated patient intervention. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(2):159–66.

Zabar S, Adams J, Kurland S, Shaker-Brown A, Porter B, Horlick M, et al. Charting a Key Competency Domain: Understanding Resident Physician Interprofessional Collaboration (IPC) Skills. 2016 (1525–1497 (Electronic)).

Kow CS, Teo YH, Teo YN, Chua KZ, Quah EL, Kamal NH, Tan LH, Cheong CW, Ong YT, Tay KT, Chiam M. A systematic scoping review of ethical issues in mentoring in medical schools. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):1–0.

Ngiam LX, Ong YT, Ng JX, Kuek JT, Chia JL, Chan NP, Ho CY, Abdurrahman AB, Kamal NH, Cheong CW, Ng CH. Impact of Caring for Terminally Ill Children on Physicians: A Systematic Scoping Review. Am J Hosp Palliat Med®. 2020. p. 1–23.

Osama T, Brindley D, Majeed A, Murray KA, Shah H, Toumazos M, et al. Teaching the relationship between health and climate change: a systematic scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2018;8(5):e020330.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69.

Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Soares C, Khalil H, Parker D. Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews; 2015. p. 1–24.

Krishna LK. CONTINOUS DEEP PALLIATIVE SEDATION: AN ETHICAL ANALYSIS [doctoral dissertation]. Singapore, Singapore: NationalUniversity of Singapore; 2013.

Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(4):371–85.

Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2006.

Ng YX, Koh ZYK, Yap HW, Tay KT, Tan XH, Ong YT, et al. Assessing mentoring: A scoping review of mentoring assessment tools in internal medicine between 1990 and 2019. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0232511.

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88.

Mehay R, Burns R. Miller’s Pyramid of Clinical Competence. The Essential handbook for GP training and education. London: Radcliffe Publishing Limited; 2009. Chapter 29: Assessment and Competency. p414.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Gordon M, Gibbs T. STORIES statement: publication standards for healthcare education evidence synthesis. BMC Med. 2014;12:143.

Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):72–8.

Haig A, Dozier M. BEME guide no 3: systematic searching for evidence in medical education--part 1: sources of information. Med Teach. 2003;25(4):352–63.

Frei E, Stamm M, Buddeberg-Fischer B. Mentoring programs for medical students--a review of the PubMed literature 2000-2008. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:32.

Lannin DG, Tucker JR, Streyffeler L, Harder S, Ripley B, Vogel DL. How medical Students' compassionate values influence help-seeking barriers. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(2):170–7.

Ramani S, Leinster S. AMEE guide no. 34: teaching in the clinical environment. Med Teach. 2008;30:347–64.

Mehay R, BR. Miller’s Pyramid of Clinical Competence; 2009.

Alfes C, Rutherford-Hemming T, Schroeder-Jenkinson CM, Booth Lord C, Zimmermann E. Promoting Interprofessional Collaborative Practice Through Simulation. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2018;39:1.

Boehler ML, Schwind CJ, Markwell SJ, Minter RM. Mock pages are a valid construct for assessment of clinical decision making and Interprofessional communication. Ann Surg. 2017;265(1):116–21.

Andersen P, Coverdale S, Kelly M, Forster S. Interprofessional simulation: developing teamwork using a two-tiered debriefing approach. Clin Simul Nurs. 2018;20:15–23.

Tofil NM, Morris JL, Peterson DT, Watts P, Epps C, Harrington KF, Leon K, Pierce C, White ML. Interprofessional simulation training improves knowledge and teamwork in nursing and medical students during internal medicine clerkship. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):189–92.

New SN, Huff DC, Hutchison LC, Bilbruck TJ, Ragsdale PS, Jennings JE, et al. Integrating collaborative Interprofessional simulation into pre-licensure health care programs. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2015;36(6):396–7.

Oxelmark L, Amorøe TN, Carlzon L, Rystedt H. Students’ understanding of teamwork and professional roles after interprofessional simulation—a qualitative analysis. Adv Simul. 2017;2(1):8.

Leann Horsley T, Reed T, Muccino K, Quinones D, Siddall V, McCarthy J. Developing a Foundation for Interprofessional Education within Nursing and Medical Curricula. Nurse Educ. 2016;41:1.

Erickson JM, Blackhall L, Brashers V, Varhegyi N. An interprofessional workshop for students to improve communication and collaboration skills in end-of-life care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2015;32(8):876–80.

Nikendei C, Huhn D, Pittius G, Trost Y, Bugaj T, Koechel A, et al. Students' Perceptions on an Interprofessional Ward Round Training - A Qualitative Pilot Study. GMS J Med Educ. 2016;33:Doc14.

Hobgood C, Sherwood G, Frush K, Hollar D, Maynard L, Foster B, et al. Teamwork training with nursing and medical students: does the method matter? Results of an interinstitutional, interdisciplinary collaboration. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(6):e25.

Solomon P, Salfi J. Evaluation of an interprofessional education communication skills initiative. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2011;24:616.

Joyal KM, Katz C, Harder N, Dean H. Interprofessional education using simulation of an overnight inpatient ward shift. J Interprof Care. 2015;29(3):268–70.

Flentje M, Müßel T, Henzel B, Jantzen J-P. Simulating a patient's fall as a means to improve routine communication: Joint training for nursing and fifth-year medical students. GMS J Med Educ. 2016;33:Doc 18.

Lumague M, Morgan A, Mak D, Hanna M, Kwong J, Cameron C, et al. Interprofessional education: the student perspective. J Interprof Care. 2006;20:246–53.

Berger S, Mahler C, Krug K, Szecsenyi J, Schultz JH. Evaluation of interprofessional education: lessons learned through the development and implementation of an interprofessional seminar on team communication for undergraduate health care students in Heidelberg–a project report. GMS J Med Educ. 2016;33(2).

Ernawati DK, Lee YP, Hughes J. Indonesian students’ participation in an interprofessional learning workshop. J Interprof Care. 2015;29(4):398–400.

Cahan M, Larkin A, Starr S, Wellman S, Haley H-L, Sullivan K, et al. A Human Factors Curriculum for Surgical Clerkship Students. Arch Surg. 2010;145:1151–7.

Nagge JJ, Lee-Poy MF, Richard CL. Evaluation of a Unique Interprofessional Education Program Involving Medical and Pharmacy Students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81:ajpe6140.

Wright A, Hawkes G, Baker B, Lindqvist S. Reflections and unprompted observations by healthcare students of an interprofessional shadowing visit. J Interprof Care. 2012;26:305–11.

Shafran DM, Richardson L, Bonta M. A novel interprofessional shadowing initiative for senior medical students. Med Teach. 2015;37(1):86–9.

Kusnoor AV, Stelljes LA. Interprofessional learning through shadowing: Insights and lessons learned. Med Teach. 2016;38:1–7.

Jain A, Luo E, Yang J, Purkiss J, White C. Implementing a nurse-shadowing program for first-year medical students to improve Interprofessional collaborations on health care teams. Acad Med. 2012;87:1292–5.

Eich-Krohm A, Kaufmann A, Winkler-Stuck K, Werwick K, Spura A, Robra BP. First Contact: interprofessional education based on medical students' experiences from their nursing internship. GMS J Med Educ. 2016;33(2).

Reeves S, Lewin S, Espin S, Zwarenstein M. Interprofessional Teamwork in Health and Social Care; 2010.

Amerongen HM, LeGros TA, Cooley JH, Schloss EP, Theodorou A. Constructive contact: Design of a successful introductory interprofessional education experience. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning. 2015;7(5):565–74.

Bradley P, Cooper S, Duncan F. A mixed-methods study of interprofessional learning of resuscitation skills. Med Educ. 2009;43:912–22.

Lin Y-C, Chan T-F, Lai C-S, Chin C-C, Chou F-H, Lin H-J. The impact of an interprofessional problem-based learning curriculum of clinical ethics on medical and nursing students' attitudes and ability of interprofessional collaboration: a pilot study. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2013;29:505–11.

MacDougall C, Schwartz BS, Kim L, Nanamori M, Shekarchian S, Chin-Hong PV. An Interprofessional Curriculum on Antimicrobial Stewardship Improves Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Appropriate Antimicrobial Use and Collaboration. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;4:ofw225.

Patel K, Desai U, Paladine H. Development and implementation of an interprofessional pharmacotherapy learning experience during an advanced pharmacy practice rotation in primary care. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2018;10(7):990–5.

Chihchen Chou F, Kwan C-Y, Hsin-Chen HD. Examining the effects of interprofessional problem-based clinical ethics: findings from a mixed methods study. J Interprof Care. 2016;30:362–9.

Anderson E, Lakhani N. Interprofessional learning on polypharmacy. The clinical teacher. 2016;13(4):291–7.

Liaw SY, Zhou WT, Lau TC, Siau C, Chan SW. An interprofessional communication training using simulation to enhance safe care for a deteriorating patient. Nurse Educ Today. 2014;34(2):259–64.

Wershofen B, Heitzmann N, Beltermann E, Fischer MR. Fostering interprofessional communication through case discussions and simulated ward rounds in nursing and medical education: A pilot project. GMS J Med Educ. 2016;33(2):Doc28.

Reising DL, Carr DE, Shea RA, King JM. Comparison of communication outcomes in traditional versus simulation strategies in nursing and medical students. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2011;32(5):323–7.

Sigalet E, Donnon T, Grant V. Undergraduate students’ perceptions of and attitudes toward a simulation-based interprofessional curriculum: the KidSIM ATTITUDES questionnaire. Simul Healthc. 2012;7(6):353–8.

Stewart M, Purdy J, Kennedy N, Burns A. An interprofessional approach to improving paediatric medication safety. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10(1):19.

Stewart M, Kennedy N, Cuene-Grandidier H. Undergraduate interprofessional education using high-fidelity paediatric simulation. Clin Teach. 2010;7(2):90–6.

Turrentine B, Rose KM, Hanks JB, Lorntz B, Owen JA, Brashers V, et al. Interprofessional training enhances collaboration between nursing and medical students: A pilot study. Nurs Educ Today. 2016;40:33–8.

Vaughn LM, Cross B, Bossaer L, Flores EK, Moore J, Click I. Analysis of an interprofessional home visit assignment: student perceptions of team-based care, home visits, and medication-related problems. Fam Med. 2014;46(7):522–6.

Pathak S, Holzmueller C, Haller KB, Pronovost P. A Mile in Their Shoes: Interdisciplinary Education at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Am J Med Qual. 2010;25:462–7.

Ponzer S, Hylin U, Kusoffsky A, Lauffs M, Lonka K, Mattiasson A-C, et al. Interprofessional training in the context of clinical practice: goals and students' perceptions on clinical education wards. Med Educ. 2004;38:727–36.

King AE, Conrad M, Ahmed RA. Improving collaboration among medical, nursing and respiratory therapy students through interprofessional simulation. J Interprof Care. 2013;27(3):269–71.

Kent F, Martin N, Keating JL. Interprofessional student-led clinics: an innovative approach to the support of older people in the community. J Interprof Care. 2016;30(1):123–8.

Ericson A, Masiello I, Bolinder G. Interprofessional clinical training for undergraduate students in an emergency department setting. J Interprof Care. 2012;26:319–25.

Hallin K, Kiessling A, Waldner A, Henriksson P. Active interprofessional education in a patient based setting increases perceived collaborative and professional competence. Med Teach. 2009;31(2):151–7.

Hallin K, Henriksson P, Dalen N, Kiessling A. Effects of interprofessional education on patient perceived quality of care. Med Teach. 2011;33(1):e22–6.

Mitchell M, Groves M, Mitchell C, Batkin J. Innovation in learning – an inter-professional approach to improving communication. Nurse Educ Pract. 2010;10:379–84.

Meffe F, Moravac C, Espin S. An interprofessional education pilot program in maternity care: findings from an exploratory case study of undergraduate students. J Interprof Care. 2012;26:183–8.

Lie DA, Forest CP, Walsh A, Banzali Y, Lohenry K. What and how do students learn in an interprofessional student-run clinic? An educational framework for team-based care. Medical education online. 2016;21(1):31900.

Sick B, Sheldon L, Ajer K, Wang Q, Zhang L. The student-run free clinic: an ideal site to teach interprofessional education?. J Interprof Care. 2014;28(5):413–8.

Rotz M, Dueñas G. "Collaborative-ready" students: exploring factors that influence collaboration during a longitudinal interprofessional education practice experience. J Interprof Care. 2016;30:1–4.

Street KN, Eaton N, Clarke B, Ellis M, Young PM, Hunt L, et al. Child disability case studies: an interprofessional learning opportunity for medical students and paediatric nursing students. Med Educ. 2007;41(8):771–80.

Salvatori P, Mahoney P, Delottinville C. An interprofessional communication skills lab: A pilot project. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2006;19:380–4.

Hudson JN, Lethbridge A, Vella S, Caputi P. Decline in medical students' attitudes to interprofessional learning and patient-centredness. (1365–2923 (Electronic)).

Hylin U, Lonka K, Ponzer S. Students’ approaches to learning in clinical interprofessional context. Medical teacher. 2011;33(4):e204–10.

Jakobsen R, Gran S, Grimsmo B, Arntzen K, Fosse E, Frich J, et al. Examining participant perceptions of an interprofessional simulation-based trauma team training for medical and nursing students. J Interprof Care. 2017;32:1–9.

Levett-Jones T, Gilligan C, Lapkin S, Hoffman K. Interprofessional education for the quality use of medicines: Designing authentic multimedia learning resources. Nurse education today. 2012;32(8):934–8.

Macdonnell C, Rege S, Misto K, Dollase R, George P. An introductory Interprofessional exercise for healthcare students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76:154.

O'Carroll V, Braid M, Ker J, Jackson C. How can student experience enhance the development of a model of interprofessional clinical skills education in the practice placement setting? J Interprof Care. 2012;26:508–10.

Feather R, Carr DE, Garletts DM, Reising D. Nursing and medical students teaming up: results of an interprofessional project. J Interprof Care. 2017;31:1–3.

Sakai DH, Marshall S, Kasuya RT, Wong L, Deutsch M, Guerriero M, et al. Medical school hotline: interprofessional education: future nurses and physicians learning together. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2012;71(6):168–71.

Luctkar-Flude M, Baker C, Hopkins-Rosseel D, Pulling C, McGraw R, Medves J, et al. Development and evaluation of an Interprofessional simulation-based learning module on infection control skills for Prelicensure health professional students. Clin Simul Nurs. 2014;10(8):395–405.

Luctkar-Flude M, Baker C, Pulling C, McGraw R, Dagnone D, Medves J, et al. Evaluating an undergraduate interprofessional simulation-based educational module: communication, teamwork, and confidence performing cardiac resuscitation skills. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2010;1:59–66.

House JB, Cedarbaum J, Haque F, Wheaton M, Vredeveld J, Purkiss J, Moore L, Santen SA, Daniel M. Medical student perceptions of an initial collaborative immersion experience. J Interprof Care. 2018;32(2):245–9.

Robertson B, Kaplan B, Atallah H, Higgins M, Lewitt MJ, Ander DS. The use of simulation and a modified TeamSTEPPS curriculum for medical and nursing student team training. Simul Healthc. 2010;5(6):332–7.

Maraccini A, Ramona H, Kemmelmeier M, Piasecki M, Slonim AD. An inter-professional approach to train and evaluate communication accuracy and completeness during the delivery of nurse-physician student handoffs. J Interprof Educ Pract. 2018;12:65–72.

Arumpanayil AJ, Winkelman C, McConnell KK, Pelyak MR, Brandt CP, Lipman JM. Attitudes toward communication and collaboration after participation in a mock page program: a pilot of an interprofessional approach to surgical residency preparation. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(6):1491–7.

Reeves SA, Denault D, Huntington JT, Ogrinc G, Southard DR, Vebell R. Learning to Overcome Hierarchical Pressures to Achieve Safer Patient Care: An Interprofessional Simulation for Nursing, Medical, and Physician Assistant Students. Nurse Educ. 2017;42(5S Suppl 1):S27–s31.

Berg B, Wong L, Vincent DS. Technology-enabled interprofessional education for nursing and medical students: A pilot study. J Interprof Care. 2010;24:601–4.

Holland C, Bench S, Brown K, Bradley C, Johnson L, Frisby J. Interprofessional working in acute care. Clin Teach. 2013;10(2):107–12.

Wagner J, Liston B, Miller J. Developing interprofessional communication skills. Teach Learn Nurs. 2011;6:97–101.

Oza SK, Wamsley M, Boscardin C, Batt J, Hauer K. Medical students' engagement in interprofessional collaborative communication during an interprofessional observed structured clinical examination: A qualitative study. J Interprof Educ Pract. 2017;7:21–7.

Morison S, Jenkins J. Sustained effects of interprofessional shared learning on student attitudes to communication and team working depend on shared learning opportunities on clinical placement as well as in the classroom. Med Teach. 2007;29:464–70.

Clarke H, Voss M. The role of a multidisciplinary student team in the community management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2016;1:1–6.

Barnsteiner JH, Disch JM, Hall L, Mayer D, Moore SM. Promoting interprofessional education. Nursing outlook. 2007;55(3):144–50.

Roland D. Proposal of a linear rather than hierarchical evaluation of educational initiatives: the 7Is framework. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2015;12:35.

Harden RM. What is a spiral curriculum?. Med Teach. 1999;21(2):141–3.

Brauer DG, Ferguson KJ. The integrated curriculum in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 96. Med Teach. 2015;37(4):312–22.

David MF, Davis MH, Harden RM, Howie PW, Ker J, Pippard MJ. AMEE Medical Education Guide No. 24: Portfolios as a method of student assessment. Med Teach. 2001;23(6):535–51.

Van Tartwijk J, Driessen EW. Portfolios for assessment and learning: AMEE Guide no. 45. Med Teach. 2009;31(9):790–801.

Shumway JM, Harden RM. AMEE Guide No. 25: The assessment of learning outcomes for the competent and reflective physician. Med Teach. 2003;25(6):569–84.

Manstead ASR. Attitudes and behaviour. Applied social psychology. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc; 1996. p. 3–29.

Potter J, Wetherell M. Discourse and social psychology: Beyond attitudes and behaviour. London: Sage; 1987.

Mennin S. Self-organisation, integration and curriculum in the complex world of medical education. Med Educ. 2010;44(1):20–30.

Acknowledgments

This paper is dedicated to the late Dr. S. Radha Krishna, whose advice and insights were critical to the conceptualization of this review.

The authors would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers whose guidance and feedback greatly enhanced this manuscript.

Funding

None. This work was carried out as part of the Palliative Medicine Initiative run by the Division of Supportive and Palliative Care at the National Cancer Centre Singapore.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CB, NCH, LKRK, JKWH and HZBG has conducted the initial database search and carried out the directed content analysis of the data. HZBG, LHET and OYT carried out the secondary searches and analysis using the Braun and Clarke’s approach to thematic analysis. LKRK, LHET, CB, NCH, JKWH, OYT, HZBG and CCWS reviewed the findings and the conclusions. CB wrote the initial manuscript which was critically revised by LKRK, SM, LHET, OYT and CCWS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

IRB approval was not required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

PubMed Search Strategy.

Additional file 2.

Summary of Included Articles.

Additional file 3.

PRISMA Checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bok, C., Ng, C.H., Koh, J.W.H. et al. Interprofessional communication (IPC) for medical students: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ 20, 372 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02296-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02296-x