Abstract

Background

Clinical guidelines recommend a preoperative forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) of > 2 L as an indication for left or right pneumonectomy. This study compares the safety and long-term prognosis of pneumonectomy for destroyed lung (DL) patients with FEV1 ≤ 2 L or > 2 L.

Methods

A total of 123 DL patients who underwent pneumonectomy between November 2002 and February 2023 at the Department of Thoracic Surgery, Beijing Chest Hospital were included. Patients were sorted into two groups: the FEV1 > 2 L group (n = 30) or the FEV1 ≤ 2 L group (n = 96). Clinical characteristics and rates of mortality, complications within 30 days after surgery, long-term mortality, occurrence of residual lung infection/tuberculosis (TB), bronchopleural fistula/empyema, readmission by last follow-up visit, and modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scores were compared between groups.

Results

A total of 96.7% (119/123) of patients were successfully discharged, with 75.6% (93/123) in the FEV1 ≤ 2 L group. As compared to the FEV1 > 2 L group, the FEV1 ≤ 2 L group exhibited significantly lower proportions of males, patients with smoking histories, patients with lung cavities as revealed by chest imaging findings, and patients with lower forced vital capacity as a percentage of predicted values (FVC%pred) (P values of 0.001, 0.027, and 0.023, 0.003, respectively). No significant intergroup differences were observed in rates of mortality within 30 days after surgery, incidence of postoperative complications, long-term mortality, occurrence of residual lung infection/TB, bronchopleural fistula/empyema, mMRC ≥ 1 at the last follow-up visit, and postoperative readmission (P > 0.05).

Conclusions

As most DL patients planning to undergo left/right pneumonectomy have a preoperative FEV1 ≤ 2 L, the procedure is generally safe with favourable short- and long-term prognoses for these patients. Consequently, the results of this study suggest that DL patient preoperative FEV1 > 2 L should not be utilised as an exclusion criterion for pneumonectomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Destroyed lung (DL) is a pulmonary disorder characterised by diffuse structural destruction of the lung resulting from chronic focal infection of lung tissues, as evidenced by chest CT imaging findings revealing multiple fibrotic lesions, bronchiectasis, necrosis, cavities, and calcification [1,2,3,4]. This serious condition, which can lead to almost complete loss of lung function, is more prevalent in developing countries, where approximately one-half to two-thirds of patients experience varying degrees of respiratory dysfunction [1, 5, 6]. Pathogens commonly implicated in DL causation include Mycobacterium tuberculosis and/or diverse fungal species, which can trigger recurrent infections that cannot be controlled with chemotherapy, as reflected by repeatedly positive sputum cultures. Such infections can escalate, leading to development of massive hemoptysis requiring surgical removal of infected tissues to save lives [7,8,9]. In addition, surgery can improve patients’ quality of life by removing multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) bacilli and damaged tissues from the lungs to prevent infection recurrence and restore respiratory function [10,11,12,13,14].

Preoperative pulmonary function tests are valuable tools used to assess surgical eligibility and the optimal scope of surgical lung resection. Notably, forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) was identified by Boush et al. (1971) as a crucial preoperative evaluation benchmark for predicting patient tolerance of thoracic surgery [15]. Their findings demonstrated that for every 10% decrease in FEV1 value, the incidence of lung-related complications increased 1.1-fold [1, 16]. Similarly, another study of 1046 lung cancer patients conducted by Ferguson et al. [17]. pinpointed FEV1 as an independent predictive risk factor for perioperative mortality resulting from pulmonary complications, as consistent with results of a study conducted by Licker et al. of 1239 lung cancer patients underscoring the value of FEV1 in predicting complications of lung surgery [18]. Based on these findings, pulmonary surgical guidelines provided by the British Thoracic Society (BTS) and the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommend the absolute value of FEV1 as a screening criterion for pneumonectomy candidates, with FEV1 > 2.0 L signifying the procedure is suitable and feasible for patients meeting this criterion [19, 20].

Notably, our thoracic surgery department has achieved favourable clinical outcomes performing unilateral pneumonectomies in DL patients with FEV1 ≤ 2 L. Therefore, in this retrospective study we analysed clinical data of DL patients with FEV1 ≤ 2 L or FEV1 > 2 L who underwent pneumonectomy in our hospital from 2002 to 2023. The study aimed to assess pneumonectomy effectiveness and safety in these patient groups and investigate the clinical significance of FEV1 as a preoperative criterion for excluding DL patients from pneumonectomy.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

The study included a total of 135 patients diagnosed with DL who underwent pneumonectomy at Beijing Chest Hospital, a hospital affiliated with Capital Medical University, from November 2002 to February 2023. Among them, 12 patients who did not undergo preoperative lung function testing were excluded, leaving a total of 123 patients for the analysis. Based on preoperative forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) value, patients were sorted into two groups: the FEV1 > 2 L group (30 cases) and the FEV1 ≤ 2 L group (96 cases).

Clinical data were extracted from the hospital’s electronic medical records system. The study design adhered to the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration. The requirement for patient written informed consent for participation in the study was waived by the Ethics Committee of the Institutional Review Board of Beijing Chest Hospital, an affiliate of Capital Medical University (Ethics number: Clinical Research 2018 (43)).

Inclusion criteria were as follows: postoperative pathological morphology consistent with TB or inflammation, meeting surgical treatment criteria for DL patients, all of these no sign of respiratory failure, as based on preoperative arterial blood gas analysis.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: bronchial asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, interstitial lung disease, concurrent malignant tumours, chronic heart failure, chronic renal insufficiency, one or more of these.

Indications of DL patient suitability for pneumonectomy were as follows: lesions located in one lung, life-threatening massive hemoptysis, DL-related recurrent infections, MDR-TB, inability to tolerate anti-TB treatment, repeated positive results of sputum culture and/or smear for M. tuberculosis.

Demographic data included gender, age, body mass index (BMI), smoking history, history of alcohol use, major complications, and common comorbidities (hypertension, coronary heart disease, and diabetes). General clinical data included primary symptoms at admission and duration of the current bout of infection/TB (in months). Infections with MDR-TB, extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB), and chronic aspergillosis were documented.

The modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale (mMRC) was employed to assess dyspnea severity at time of admission then patients were sorted into two groups based on mMRC score: mMRC = 0 and mMRC ≥ 1. Preoperative auxiliary evaluations included chest CT scans, pulmonary function tests, and routine laboratory tests. Chest CT scan interpretation included the identification of spinal scoliosis and TB cavities within the lesion area. Lung function measurements were conducted using Master Screen-IOS and Master Screen-PFT instruments (Jaeger, Germany). The single-breath diffusion method was employed to determine lung diffusion capacity and predicted lung function values as based on instrument default values endorsed by the European Respiratory Society. Key indicators assessed via lung function testing included forced vital capacity (FVC), FEV1, total lung capacity (TLC), and diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO).

Surgery-related data included the following: intraoperative blood loss, duration of surgery, left or right lung resection, and performance of pleural stripping. Pneumonectomies were performed as open surgeries.

Short-term postoperative observation-based indicators included death during hospitalisation or within 30 days after discharge, postoperative complications (requiring invasive respiratory support, residual lung infection, heart failure), and median duration of postoperative complications (in days).

Follow-up face-to-face or telephone interviews were administered by a healthcare provider through June 30, 2023 to assess participant survival status, postoperative TB/pulmonary infection recurrence, respiratory function, readmission history, and postoperative treatment. Three patients died during the perioperative period. Of the 120 participants, 26 Of the initial participants (21.7% of 120) became unreachable after three unsuccessful attempts to establish contact via telephone, leading to their classification as lost to follow-up. within the perioperative period, three patients passed away. Subsequently, the follow-up was successfully completed by the remaining 94 patients, with an average age of 39.8 ± 13.6 years. This cohort comprised 28 males and 66 females.

Quality control

Overall aims of this study included the establishment of a standardised follow-up program, a training program, and a follow-up methodology. The follow-up program design and questionnaire were reviewed and validated by senior respiratory medicine and thoracic surgery clinicians prior to follow-up program implementation under supervision of highly trained general practitioners (GPs). GPs were responsible for conducting face-to-face or telephone interviews to gather comprehensive patient clinical data following hospital discharge.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using the SPSS 25.0 statistical software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and included analysis of both continuous and categorical variables. Normally distributed continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, with intergroup comparisons conducted using the t-test. Non-normally distributed continuous variables are expressed as median (25%, 75%) percentile, with intergroup comparisons conducted using the Z-test. Categorical variables are presented as composition ratios or percentages (%), with intergroup comparisons conducted using the chi-square test.

The study aimed to compare short-term mortality and postoperative complications between FEV1 > 2 L and FEV1 ≤ 2 L groups. Additionally, follow-up observations were compared between groups regarding rates of mortality, residual lung reinfection, bronchial stump fistula/empyema, and readmission, as well as postoperative proportions of patients with mMRC ≥ 1.

Binary logistic regression analysis was performed to identify correlations between independent variables (gender, age, current or past smoking status, presence of cavities on chest CT images and the continuous variable FEV1) and dependent variables related to clinical short- and long-term outcomes. Outcomes variables included rates of postoperative 30-day mortality, incidence of postoperative complications, long-term mortality, residual lung reinfection, TB recurrence, and bronchial stump fistula/empyema, as well as the proportion of patients with mMRC ≥ 1 at follow-up and the postoperative rehospitalisation rate. Clinically relevant statistically significant factors (P < 0.05) are listed in Table 1.

Results

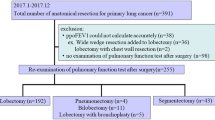

A total of 123 patients who underwent pneumonectomy for DL were included in the study. Among them, 75.6% (93/123) had preoperative lung function FEV1 values of ≤ 2 L and 96.7% (119/123) were discharged without postoperative complications. The FEV1 > 2 L group was comprised of 30 participants, accounting for 24.4% (30/123) of patients. This group included 18 males and 12 females with an overall mean age of 44.6 ± 12.3 years. In contrast, the FEV1 ≤ 2 L group consisted of 93 cases, accounting for 75.6% (93/123) of patients. This group included 24 males and 69 females with an overall mean age of 40.2 ± 13.7 years (Fig. 1). Pathological examinations confirmed TB-related lung damage in 77 cases (62.6%) and identified massive hemoptysis in 20 cases (16.3%). At time of admission, 70 cases (56.9%) had mMRC scores of ≥ 1 (Table 1).

As compared to the FEV1 ≤ 2 L group, the FEV1 > 2 L group exhibited a higher proportion of males and smokers (P = 0.001 and P = 0.027, respectively), while the FEV1 > 2 L group exhibited a significantly higher mean FVC%pred value as compared to that of the FEV1 ≤ 2 L group (65.1 ± 14.4 vs. 57.2 ± 1.6, respectively, P = 0.003). Moreover, the proportion of patients with detectable pulmonary cavities on chest CT scans was higher in the FEV1 > 2 L group than in the FEV1 ≤ 2 L group (46.7% vs. 24.7%, respectively, P = 0.023) (Table 1).

Comparisons of short-term surgical outcomes revealed no significant intergroup differences in the mortality rate within 30 days after surgery/discharge or the postoperative complication rate. Similarly, comparisons of long-term outcomes through the end of the follow-up period revealed no significant intergroup differences in rates of mortality, residual lung reinfection/TB recurrence, bronchial stump fistula/empyema, mMRC score, and rehospitalisation (Table 2).

As shown in Table 3, results of logistic regression analysis indicated no significant differences in correlations observed between independent and dependent variables for FEV1 > 2 L and FEV1 ≤ 2 L groups in this study. Independent variables included FEV1 as a continuous variable and its covariates (gender, age, smoking, presence of lesions on chest CT images). Dependent variables included short-term outcomes such as mortality rates within 30 days post-surgery and postoperative complication rates, as well as long-term outcomes including rates of mortality, residual lung reinfection/TB recurrence, bronchial stump fistula/empyema, postoperative hospitalisation, and the proportion of patients with mMRC ≥ 1 during follow-up.

Discussion

Surgical lung resection is an important diagnostic and therapeutic method used to treat pulmonary diseases, including DL, a severe complication of pulmonary infection [14, 21, 22]. However, surgeons view pneumonectomy as a high-risk surgical procedure [23, 24], especially when used to treat patients with pre-existing lung damage. As such, current clinical guidelines recommend a preoperative FEV1 value of > 2 L as an indication for surgery [19, 25, 26], with BTS/ACCP guidelines [19, 20] recommending a preoperative FEV1 > 2 L as an indication for pneumonectomy of lung cancer patients.

Currently, there is a notable absence of established guidelines or expert consensus regarding pneumonectomy as a DL treatment. In this study, despite the fact that 75.6% of DL patients had preoperative FEV1 values of ≤ 2 L, 96.7% of patients experienced successful postoperative treatment outcomes at discharge. Furthermore, no significant differences were observed between FEV1 > 2 L and FEV1 ≤ 2 L groups with regard to short-term outcome rates, including mortality within 30 days post-surgery and postoperative complications. Likewise, no intergroup differences were observed in long-term follow-up rates pertaining to mortality, recurrence of residual lung infection/TB, occurrence of bronchopleural fistula/empyema, postoperative readmission, or proportions of patients with mMRC ≥ 1 at follow-up. These findings suggest that a preoperative FEV1 value of ≤ 2 L should not preclude pneumonectomy, while also highlighting pneumonectomy as a safe and viable treatment option offering favourable short-term and long-term outcomes for DL patients.

In this study, the FEV1 ≤ 2 L group exhibited lower proportions of males and smokers as compared to the FEV1 > 2.0 L group, potentially reflecting common trends of higher FEV1 values and smoking rates among males. The incidence rate of perioperative complications was 26.8%, aligning with findings reported by other research groups [21, 23, 27], thereby demonstrating that most pneumonectomised DL patients recover successfully and resume normal activities after surgery. However, a small number of patients experienced complications, such as recurrent lung infection and bronchopleural fistula, as consistent with results of our previous study [13]. The overall mortality rate at the end of the follow-up period was 7.5%. Interestingly, the incorporation of the actual measured FEV1 as a continuous variable within our regression model revealed no significant correlations between FEV1 values and either short-term or long-term postoperative outcomes.

In the 1970s, studies of over 2000 pneumonectomy cases conducted across three research centres demonstrated a mortality rate of 5% for patients with preoperative FEV1 values of > 2 L, a clinical standard that continues to be followed [25]. Nonetheless, it should be noted here that lung resection methodologies used to treat DL and lung cancer patients differ. Lung cancer resection typically involves removal of the tumour and surrounding lung tissue with the aim of preserving some respiratory function of the treated lung. Conversely, DL resection involves the excision of irreversibly damaged lung tissue, as confirmed by radiographic imaging [1]. This diseased tissue affects ventilation function within the lesion area, inducing pulmonary-systemic shunting that reduces the ventilation/perfusion ratio, leading to long-term hypoxia. However, organs and tissues of most DL patients gradually adapt to the hypoxic state as the disease progresses [12, 28]. Notably, the excision of non-ventilated tissue in unilateral diffuse lung (DL) patients can notably enhance the ventilation/perfusion ratio, elevate oxygen index values in organs and tissues, and alleviate respiratory distress, ultimately contributing to an improved quality of life [13]. Conversely, lung cancer resection involves eliminating tumor tissue that still retains some gas exchange function. This process significantly reduces the ventilation/perfusion ratio without activating compensatory mechanisms, thereby increasing the risk of stress responses and subsequent postoperative complications [29].

These contrasting outcomes led us to hypothesize that decreased ventilation and the activation of stress responses heighten the probability of postoperative complications in pneumonectomized lung cancer patients compared to those with diffuse lung diseases [30, 31]. Therefore, a preoperative lung function FEV1 > 2 L might be a crucial indicator for pneumonectomy in left/right lung cancer patients but may not hold the same significance for DL patients.

This study had several limitations. First, its retrospective nature and inclusion of a relatively small number of cases may have weakened the robustness of our conclusions. This limitations may stem from low clinician awareness of DL and the absence of established clinical DL treatment guidelines that ultimately hindered our ability to evaluate smaller effect factors. Nevertheless, this study encompassed all DL pneumonectomy cases treated at our centre over a 21-year period, a relatively large sample size as compared to sample sizes of other studies focused on this rare condition. Moreover, as the study was conducted at a single centre, our results might not be generalisable to other healthcare settings or populations. Secondly, a significant proportion of patients (21.7%) were lost to follow-up, potentially affecting the strength of our long-term outcomes data. Thirdly, despite standardised training, variations in expertise among thoracic surgeons over the extended duration of the study and the diverse surgical techniques employed may have introduced biases into our results, particularly those related to post-surgical respiratory failure rates. Finally, our study was solely focused on assessing long-term respiratory distress in DL patients during the follow-up period without analysing lifestyle and psychological factors that could significantly impact respiratory function. Hence, larger-scale clinical studies are warranted to establish specific FEV1 assessment and cutoff values for predicting postoperative risks.

Conclusion

Pneumonectomy appears to be a safe and viable option for DL patients, including those with preoperative lung function FEV1 values of ≤ 2 L. No significant differences were observed between DL patients with FEV1 values of ≤ 2 L and > 2 L with regard to rates of postoperative survival, complications, recurrence of residual lung infection/TB, bronchopleural fistula, mMRC ≥ 1 at follow-up, and readmission. Hence, the preoperative lung function criterion FEV1 > 2 L may not be an appropriate indication for pneumonectomy in DL patients, particularly in the absence of surgical guidelines or consensus. Given the current lack of compelling evidence, further research is warranted to ascertain the true predictive value of FEV1 in assessing postoperative risks of DL patients.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the.

corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- FEV1% pred:

-

forced expiratory volume in one second of predicted

- TDL:

-

tuberculosis-destroyed lung

- CPA:

-

chronic pulmonary aspergillosis

- BPF:

-

bronchopleural fistula

- MDR-TB:

-

multidrug-resistant tuberculosis

- XDR-TB:

-

extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- MMV% pred:

-

maximal minute ventilation of predicted

- DLCO% pred:

-

lung diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide of predicted

- CRP:

-

C-reaction protein

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- CI:

-

confidence interval

References

Rhee CK, Yoo KH, Lee JH, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with tuberculosis-destroyed lung. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(1):67–75.

Ryu YJ, Lee JH, Chun EM, Chang JH, Shim SS. Clinical outcomes and prognostic factors in patients with tuberculous destroyed lung. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15(2):246–50, i.

Kim SJ, Lee J, Park YS, et al. Effect of airflow limitation on acute exacerbations in patients with destroyed lungs by tuberculosis. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30(6):737–42.

Fawibe AE, Salami AK, Oluboyo PO, Desalu OO, Odeigha LO. Profile and outcome of unilateral tuberculous lung destruction in Ilorin, Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2011;30(2):130–5.

Yue B, Ye S, Liu F, et al. Bilateral lung transplantation for patients with destroyed lung and asymmetric chest deformity. Front Surg. 2021;8:680207.

Muñoz-Torrico M, Rendon A, Centis R, et al. Is there a rationale for pulmonary rehabilitation following successful chemotherapy for tuberculosis. J Bras Pneumol. 2016;42(5):374–85.

Kim SW, Lee SJ, Ryu YJ, et al. Prognosis and predictors of rebleeding after bronchial artery embolization in patients with active or inactive pulmonary tuberculosis. Lung. 2015;193(4):575–81.

Lee JK, Lee YJ, Park SS, et al. Clinical course and prognostic factors of pulmonary aspergilloma. Respirology. 2014;19(7):1066–72.

Okubo K, Ueno Y, Isobe J, Kato T. Emergent pneumonectomy for hemoptysis in a patient with previous thoracoplasty. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 2004;45(5):515–7.

Rivera C, Arame A, Pricopi C, et al. Pneumonectomy for benign disease: indications and postoperative outcomes, a nationwide study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;48(3):435–40. discussion 440.

Lee Y, Kim HK, Lee S, Kim H, Kim J. Surgical correction of postpneumonectomy-like syndrome in a patient with a tuberculosis-destroyed lung. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;136(3):780–1.

Ruan H, Li Y, Wang Y, et al. Risk factors for respiratory failure after tuberculosis-destroyed lung surgery and increased dyspnea score at 1-year follow-up. J Thorac Dis. 2022;14(10):3737–47.

Ruan H, Liu F, Li Y, et al. Long-term follow-up of tuberculosis-destroyed lung patients after surgical treatment. BMC Pulm Med. 2022;22(1):346.

Han D, Lee HY, Kim K, Kim T, Oh YM, Rhee CK. Burden and clinical characteristics of high grade Tuberculosis destroyed lung: a nationwide study. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11(10):4224–33.

Boushy SF, Billig DM, North LB, Helgason AH. Clinical course related to preoperative and postoperative pulmonary function in patients with bronchogenic carcinoma. Chest. 1971;59(4):383–91.

Tashkin DP, Li N, Halpin D, et al. Annual rates of change in pre- vs. post-bronchodilator FEV1 and FVC over 4 years in moderate to very severe COPD. Respir Med. 2013;107(12):1904–11.

Ferguson MK, Siddique J, Karrison T. Modeling major lung resection outcomes using classification trees and multiple imputation techniques. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;34(5):1085–9.

Licker MJ, Widikker I, Robert J, et al. Operative mortality and respiratory complications after lung resection for cancer: impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and time trends. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(5):1830–7.

BTS guidelines. Guidelines on the selection of patients with lung cancer for surgery. Thorax. 2001;56(2):89–108.

Colice GL, Shafazand S, Griffin JP, Keenan R, Bolliger CT. Physiologic evaluation of the patient with lung cancer being considered for resectional surgery: ACCP evidenced-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition). Chest. 2007;132(3 Suppl):161S–77S.

Ruan H, Liu F, Han M, Gong C. Incidence and risk factors of postoperative complications in patients with tuberculosis-destroyed lung. BMC Pulm Med. 2021;21(1):273.

Park DW, Kim BG, Jeong YH, et al. Risk of short- and long-term pulmonary complications should be determined before surgery for tuberculosis-destroyed lung. J Thorac Dis. 2023;15(3):950–2.

Li Y, Hu X, Jiang G, Chen C. Pneumonectomy for treatment of destroyed lung: a retrospective study of 137 patients. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;65(7):528–34.

Halezeroglu S, Keles M, Uysal A, et al. Factors affecting postoperative morbidity and mortality in destroyed lung. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64(6):1635–8.

Peng J, Zhao L, Wang Y, et al. A study of the correlation between total lung volume and the percent of low attenuation volume and PFT indicators in patients with preoperative lung cancer. Med (Baltim). 2023;102(29):e34201.

Bolliger CT, Wyser C, Roser H, Stulz P, Solèr M, Perruchoud AP. [Lung scintigraphy and ergospirometry in prediction of postoperative course in lung resection candidates with increased risk of postoperative complications]. Pneumologie. 1996;50(5):334–41.

Bai L, Hong Z, Gong C, Yan D, Liang Z. Surgical treatment efficacy in 172 cases of tuberculosis-destroyed lungs. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;41(2):335–40.

Jo YS, Park JH, Lee JK, Heo EY, Chung HS, Kim DK. Risk factors for pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients with tuberculosis-destroyed lungs and their clinical characteristics compared with patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:2433–43.

Chai XQ, Ma J, Xie YH, Wang D, Chen KZ. Flurbiprofen axetil increases arterial oxygen partial pressure by decreasing intrapulmonary shunt in patients undergoing one-lung ventilation. J Anesth. 2015;29(6):881–6.

Torres MF, Porfirio GJ, Carvalho AP, Riera R. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation for prevention of complications after pulmonary resection in lung cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(9):CD010355.

Horino T, Tokunaga R, Miyamoto Y, et al. The advanced lung cancer inflammation index is a novel independent prognosticator in colorectal cancer patients after curative resection. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2022;6(1):83–91.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Beijing Hospitals Authority Innovation Studio of Young Staff Funding Support, code: 202134. Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Incubating Program, code: PX2022064.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.R. and F.L. wrote the main manuscript text and W.L. prepared Figs. 1. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study design adhered to the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration. Approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Chest Hospital, Capital Medical University (Ethics No.: Clinical Research 2018 (43)). Clinical data were extracted from the hospital’s electronic medical records system. publication of such data does not compromise anonymity or confidentiality or breach local data protection laws. Any participants will fully anonymous. The Ethics Committee of Beijing Chest Hospital of Capital Medical University waived the written informed consent of the patients in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Zhao, J., Gong, C. et al. Value of preoperative evaluation of FEV1 in patients with destroyed lung undergoing pneumonectomy - a 20-year real-world study. BMC Pulm Med 24, 39 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-024-02858-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-024-02858-5