Abstract

Background

The leaf is a determinate organ essential for photosynthesis, whose size and shape determine plant architecture and strongly affect agronomic traits. In soybean, the molecular mechanism of leaf development is not well understood. The flowering repressor gene E1, which encodes a legume-specific B3-like protein, is known to be the gene with the largest influence on soybean flowering and maturity. However, knowledge of its potential other functions remains poor.

Results

Here, we identified a novel function of E1 protein in leaf development. Unifoliolate leaves of E1-overexpression (E1-OE) lines were smaller and curlier than those of wild type DongNong 50 (DN50) and Williams 82 (W82). Transverse histological sections showed disorganized cells and significantly elevated palisade tissue number, spongy tissue number, and bulliform cell number in E1-OE lines. Our results indicate that E1 binds to the promoters of the leaf- development-related CINCINNATA (CIN)-like TEOSINTE BRANCHED1/CYCLOIDEA/PROLIFERATING CELL FACTOR (TCP) transcription factor genes to negatively regulate their expression.

Conclusions

Our findings identify E1 as an important new factor in soybean leaf development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The shape of the leaf, the main photosynthetic organ in plants, varies based on species and developmental stage [1,2,3]. Leaf size and shape are important for leaf function and plant survival [4,5,6,7]. Genes that influence leaf formation have been described in rice, Cardamine, tomato, and Arabidopsis thaliana [1, 3, 8,9,10,11]. For example, TCP3 gene regulates Arabidopsis leaf development via the jasmonate signaling pathway [12, 13]. In rice, curled later1 (cur1) mutants have narrow leaves compared with wild type (WT) [3]. Little is known, however, about the molecular mechanisms of leaf development of in soybean (Glycine max), despite its status as an economically important plant oil and protein crop.

In 1927, a pair of genes controlling soybean maturity were detected and named E and e [14]. In 1971, Bernard confirmed that these genes are identical to E1 and e1, two alleles of a major locus that influencing maturity [15]. The E1 locus has a largest impact on flowering time and maturity in cultivated soybean [16,17,18]. Xia et al. mapped E1 through positional cloning, and discovered that it contained a putative nuclear localization signal and sequences related to the plant-specific B3 domain [19]. The E1 protein is assumed to be a transcription factor unique to legumes [18, 19]. In cultivated soybean, it inhibits flowering: the leaky allele (e1-as) and the loss-of-function alleles (e1-fs and e1-nl) cause earlier flowering under long-day (LD) conditions [17, 19, 20]. The molecular mechanism of E1 regulation of soybean flowering has been well studied, with both genes acting upstream of E1 (such as E3, E4, J, LHYs, Tof11, and Tof12) [19,20,21,22] and genes acting downstream of E1 (such as FT2a and FT5a) reported [19, 23,24,25]. In soybean, some important flowering genes have different functions in other aspects of plant development [26, 27]. For instance, FT5a have dual function in the regulation of post-flowering stem growth and flowering time [27]. Nonetheless, possible roles of E1 in other developmental processes are unknown.

In Arabidopsis, microRNA miR319A/ JAGGED AND WAVY (JAW), a key role in leaf development, causing a wavy-leaf phenotype by suppresses CINCINNATA (CIN) subclass TEOSINTE BRANCHED1/CYCLOIDEA/PROLIFERATING CELL FACTOR (TCP) genes (TCP2, TCP3, TCP4, TCP10, and TCP24) [12]. The TCP proteins comprise one of the largest families of plant-specific transcription factors [28,29,30]. Among them, CINCINNATA (CIN) subclass TCP genes contribute to regulate the leaf development [10, 12, 31,32,33]. The soybean genome encodes 54 TCP transcription factors that fall into two classes: 26 members in class I group TCPs and 28 in class II group TCPs. Class II TCP members are further divided into the CIN subclass (19 TCPs) and the CYCLOIDEA/ TEOSINTE BRANCHED1 (CYC/TB1) subclass (9 TCPs) [30]. In this study, we uncovered a role of E1 in soybean leaf development, finding that E1 directly represses CIN-type TCP genes (TCP14, TCP29), resulting in small, curly unifoliolate leaves.

Results

Overexpression of E1 influences leaf development

To examine the function of E1 (Glyma.06G207800) in other developmental pathways, we created four independent transgenic lines that express p35S:E1-Flag in DN50. Immunoblot analyses confirmed the expression of the recombinant E1 fusion protein in four independent T7 E1-OE lines (E1-OE1, E1-OE2, E1-OE3, and E1-OE4). The expression of the E1 protein line was highest in E1-OE4, followed by E1-OE3, E1-OE2, and E1-OE1 (Fig. 1a). Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses confirmed that the expression level of E1 was significantly higher in E1-OE lines than in DN50, and that E1 was constitutively and highly expressed in the E1-OE4 line, followed by E1-OE3, E1-OE2, and E1-OE1 (Fig. 1b).

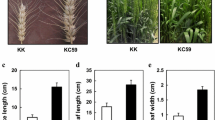

The leaf phenotypic characterization of the E1-overexpression (E1-OE) plants in DN50. a. Immuno-blot of FLAG antibodies in DN50 and E1-OE lines. The gel image had high-contrast and the original gel image included in the Additional file 2. b. The expression of E1 in DN50 and E1-OE plants. The soybean TUB (GmTubulin) gene was used as an internal control to normalize gene expression data. The experiment was performed using three biological replicates, each with three technical replicates. Differences between groups were statistically analyzed using Student’s t-test (**P < 0.01). Bars indicate standard error of the mean. c. Top view of DN50 and E1-OE plants. Red boxes indicates that the close-up image of the leaf of DN50 and E1-OE plants. d. Quantification of leaf size in DN50 and E1-OE plants (n = 10). e. Quantification of leaf weight in DN50 and E1-OE plants (n = 10). All values are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) (n = 10 plants). Bars indicate the s.e.m. Significant differences were identified by Student’s t-test (**P < 0.01)

As compared with DN50, E1-OE transgenic plants flowered significantly later under long-day conditions, and the plants were much shorter (Additional file 1: Fig. S1a-b). Assessment of the unifoliolate leaves of E1-OE and DN50 plants at 7 DAE, revealed that E1-OE plants had smaller leaf areas and lower leaf weights than DN50 (Fig. 1c-e), they also curled downward (Fig. 1c). Higher E1 expression in the E1-OE lines was associated with increased curliness of the leaves (Fig. 1c).

We also observed the phenotypes of T1 E1-OE transgenic lines in the Williams82 (W82) background. Consistent with our observations of E1-OE transgenics in DN50, leaf area and weight of E1-OE plants (E1-OE5–8) were smaller and lighter than those of W82 (Additional file 1: Fig. S2a-c). Thus, E1 may regulate leaf development in soybean. Since the genetic stability of T7 E1-OE lines in DN50 was higher than that of T1 E1-OE lines in W82, the E1-OE transgenic lines in DN50 were selected for subsequent experiments.

E1 regulates cell number and size in the developing leaf

Proper balance of leaf tissue structure is critical for normal leaf development [34]. To further our understanding of the processes controlling leaf development, we analyzed transverse histological sections of E1-OE unifoliolate leaves. Compared with those in DN50 plants, cells were more disorganized in E1-OE plants (Fig. 2a). As an additional approach to examine the effects of E1-OE, we compared leaf functional traits such as leaf thickness, the cell tense ratio (CTR), spongy tissue ratio (SR), cell number and cell size (Fig. 2b-i). Leaf thickness was similar in E1-OE1 and E1-OE2 lines, but increased in E1-OE3 and E1-OE4 lines (Fig. 2b). The CTR, SR, and spongy tissue size were similar in E1-OE and DN50 plants (Fig. 2g, h, i). In contrast, E1-OE plants had significantly higher palisade tissue number, spongy tissue number and bulliform cell number (Fig. 2c-e), and lower palisade tissue size (Fig. 2f), confirming that the E1 could regulate leaf development by affecting the leaf tissue structure. We found that higher expression of E1 was associated with a more obvious cellular phenotype, confirming that E1 could influence the balance of different cells within the leaf tissue.

The cell size and cell number of the leaf in DN50 and E1-OE plants. a. Transverse sections of leaves from DN50 and E1-OE lines. b. Quantification of leaf thickness. c. Bulliform cell number. d. Palisade tissue number. e. Spongy tissue number. f. Palisade tissue size. g. Spongy tissue size. h. spongy tissue ratio. i. cell tense ratio

RNA-seq analysis of E1 overexpression

To identify the genes and signaling pathways related to E1-mediated leaf development, we performed RNA-seq analysis and analyzed the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the E1-OE transgenic and DN50 plants. The gene expression levels were similar between two biological replicates (Fig. 3a), but differed significantly between the E1-OE transgenic lines and DN50 plants. Genes involved in metabolic process, cellular process, single-organism process, response to stimulus, and biological regulation were enriched in the DEGs (Fig. 3b). We compared the RNA- seq datasets and identified a total of 7407 DEGs (FDR P < 0.01) (Additional file 2: Data S1). Among these, 3966 genes were significantly upregulated and 3441 genes were significantly downregulated (Fig. 3c). The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis demonstrated that some primary metabolic pathways that are essential for plant growth and development were significantly enriched; these included fatty acid metabolism, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, cysteine and methionine metabolism, and starch and sucrose metabolism (Fig. 3d).

Differentially expressed genes identified from RNA-seq analysis. a. The heat map of differentially expressed genes in DN50 and E1-OE lines. The numerical values for the blue-to-red gradient bar represent log2-fold change relative to the control sample. b. GO terms that were statistically enriched in differentially expressed genes in DN50 and E1-OE lines according to the RNA-seq assay. c. The numbers of genes showing differential expression between DN50 and E1-OE plants. d. KEGG pathway that were statistically enriched in DN50 and E1-OE RNA-seq assay. The dot size indicates the number of DEGs of the pathway, and the red-to-blue gradient dot represent -log10 (P- value)

RNA-seq approaches have identified transcription factor (TF) gene families, such as the AP2/ERF-ERF, bHLH, MYB, WRKY, NAC, HB-HD-ZIP, C2H2, GRAS, bZIP, MYB-related, TCP and B3-ARF families (Fig. 4a). Many studies suggested that the CIN subclass TCP genes, played the important role in regulating the leaf development [31,32,33]. We found 14 TCP TF genes among the DEGs, of which six were CIN-type TCP genes (Fig. 4a). The heat map showed that 5 CIN-type TCP (TCP6, TCP14, TCP15, TCP30, and TCP33) genes were significantly downregulated in E1-OE transgenic lines as compared with DN50 (Fig. 4b).

E1 negatively regulates the expression of TCP family genes in soybean. a. Numbers of transcription factors among differentially expressed genes in DN50 and E1-OE lines based on RNA-seq data. Green represents PCF subclass TCP genes, grey represents CIN subclass TCP genes. b. The heat map of differential expression of CIN subclass TCP genes in DN50 and E1-OE plants. The numerical values for the blue-to-green gradient bar represent log2- (fold change) relative to the control sample. c-n. The transcription levels of TCP5, TCP7, TCP11, TCP13, TCP14, TCP15, TCP18, TCP19, TCP29, TCP32, TCP47 and TCP49 in DN50 and E1-OE plants; data obtained by qRT-PCR. Significant differences were analyzed based on the results of three biological replicates, each with three technical replicates (Student’s t-test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Bars indicate the standard error of the mean

E1 represses TCP genes

The soybean genome includes 19 CIN-subclass TCP genes [30]. To validate the RNA-seq results and E1 regulation in all 19 CIN-type TCP genes in soybean, we tested their expression by qRT-PCR in E1-OE and DN50 plants. Most genes were downregulated in E1-OE transgenic plants, including TCP6, TCP7, TCP11, TCP13, TCP14, TCP18, TCP19, TCP29, TCP47, and TCP49 (Fig. 4c-n). However, the expression levels of TCP15, TCP36, TCP39, and TCP42 remained unchanged (Additional file 1: Fig. S3b, d, e), and TCP32, TCP33 and TCP37 were upregulated in E1-OE transgenic (Additional file 1: Fig. S3a, c). The expression levels of TCP30 and TCP38 were not detected in E1-OE and DN50 plants.

To examine the regulatory effect of E1 on its target genes, we performed transient expression assays, using TCP14 and TCP29 promoters fused to the LUC reporter (pTCP14:LUC and pTCP29:LUC; Fig. 5a). The effector construct harbored E1 under the control of the 35S promoter (p35S:E1; Fig. 5a). We transformed the reporter construct (pTCP14:LUC or pTCP29:LUC) and the effector construct (p35S:E1) into healthy N. benthamiana leaves and found that E1 significantly repressed TCP14 and TCP29 expression (Fig. 5b). Thus, E1 regulates leaf development by repressing CIN-type TCPs.

E1 represses TCPs transcription by directly binding to the promoter. a. Constructs used for the transient transfection assay. b. Luciferase activity under the control of TCP14 and TCP29 promoters, from three biological replicates. A Student’s t-test was used to detect statistically significant differences. c. Location of the promoters of TCP14 and TCP29 and the amplicons targeted in ChIP-qPCR assay. d. Results of ChIP-qPCR on TCP amplicons in DN50 and E1-OE lines fused with Flag tags. A monoclonal Flag antibody was used for the ChIP assay

To determine whether E1 directly inhibits the expression of TCP genes, we performed a ChIP-qPCR assay to compare the relative enrichment of specific TCP14 and TCP29 sequences in E1-OE and DN50 plants using anti-Flag antibodies. We selected four sites in the 2027 bp and 2209 bp regions upstream of the TCP14 and TCP29 promoters, respectively (Fig. 5c). The E1 protein was highly enriched in the TCP14 promoter sites 1 and 4, and in the TCP29 promoter site 1, whereas it was present at extremely low levels in the DN50 control (Fig. 5c). These results showed that E1 could directly bound the promoters of TCP genes.

The transcript levels of the CIN-type TCP genes in soybean tissues

To understand the functions of CIN-type TCP genes in soybean, we use an RNA-seq database and retrieved transcript levels of 10 of the TCP genes repressed by E1, in eight different tissues (flower, leaf, pod, shoot, nodule, cotyledon, seed and root; Machado et al., 2020). These genes presented similar expression profiles and were constitutively expressed to high levels in the leaf and cotyledon (Fig. 6a-k). In contrast, all CIN-type TCP genes displayed low transcript abundance in nodule and root, except TCP6 high expression level in seed and root (Fig. 6a-k). Moreover, TCP13, TCP47, and TCP49 presented similar expression profiles and were highly expressed in pod, flower and shoot (Fig. 6b, e, j, k). TCP7, TCP14, TCP19, TCP11, TCP18, and TCP29 were expressed in shoot and seed, seed, flower and shoot, shoot, pod and shoot, and flower, respectively (Fig. 6c, f, h, d, g, i).

The differential expression of representative CIN-type TCP genes in different tissues. a. A model of the soybean plant. b-k. The expression of TCP6, TCP7, TCP11, TCP13, TCP14, TCP18, TCP19, TCP29, TCP47, and TCP49 in different soybean tissues (flower, leaf, pod, shoot, nodule, cotyledon, seed and root) based on an RNA-seq database. The mean transcription values were visualized by TBtools; red represents high transcript level and green represents low transcript level. l. Expression levels of TCP6, TCP7, TCP11, TCP13, TCP14, TCP18, TCP19, TCP29, TCP47, and TCP49 in different soybean tissues (flower, leaf, pod, shoot, nodule, cotyledon, seed and root) by qRT-PCR. The mean transcription values were visualized by TBtools; green represents high transcript levels and blue represents low transcript levels. The mean expression value was calculated from three independent biological replicates

To determine the tissue-specific expression patterns of TCP genes, we assayed the transcript levels of 10 CIN-type TCP genes by qRT-PCR. The tissue-specific expression patterns in the qRT-PCR were similar to those in the RNA-seq data (Fig. 6l). Thus, the CIN-type TCP genes regulated by E1 play key roles in soybean leaf development.

Discussion

The role of E1 in controlling soybean flowering time and maturity is well known; the molecular mechanisms have also been reported [19, 21, 22, 35]. When E1 is knocked out in soybean, flowering is promoted by the derepression of two important FT genes (FT2a and FT5a) under long-day conditions [19, 35]. To explore the functions of E1 in other development pathways in soybean, we created E1-OE transgenics and compared them with the DN50 wild type plants. E1-OE transgenic lines flowered significantly later under long-day conditions (Additional file 1: Fig. S1b). Consistent with previous reports [19, 35], our findings demonstrate that E1 functions as a flowering repressor in soybean. We observed smaller, lighter, and curlier unifoliolate leaves in E1-OE transgenic plants (Fig. 1, Additional file 1: Fig. S1), suggesting that E1 might play an important role in leaf development.

The size and shape of a leaf are major traits that affect yield in soybean [36,37,38,39,40]. The narrow leaf trait is associated with increased seed number than broad leaf trait in soybean [36]. The locus that controls leaf shape cosegregates with the locus that controls the seed number [40]. For example, Jeong et al. [40] recorded the numbers of 1-, 2-, 3-, and 4-seeded pods and leaf shape for each of the soybean plants, and found that narrow leaf linked with 4-seeded pods. Only one gene for leaf shape has been identified by map-based cloning in soybean —an allele of ln on chromosome 20, encoded by JAGGED1 (Glyma20g25000.1), the ortholog of Arabidopsis JAGGED (JAG) [41]. JAG1 complements leaf shape and silique length in Arabidopsis mutants [41]. Although leaf traits are important for soybean yield, the molecular link between the two remains unknown. In this study, we show that overexpression of E1 in transgenic plants could affect unifoliolate leaf development and plant development (Fig. 1c-e, Additional file 1: Fig.S1a). Our data thus provide valuable information about the molecular basis of leaf development in soybean.

In plants, cell number and size affect leaf morphology [42,43,44,45]. In rice, the narrow leaf 7 (nal7) mutant has larger but fewer bulliform cells than the wild type (Haymasari), resulting in reduced leaf width [44]. The loss of function of ADL1 (Adaxialized leaf 1) increases the number of bulliform cells, which leads to a change in leaf shape in rice [42]. Our data showed that cells were more disorganized in E1-OE plants; the numbers of bulliform cells, palisade tissue cells, and spongy tissue cells were significantly higher (Fig. 2a, c-e). Thus, we propose that cell number affects the shape of the leaf. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying this effect require further study in soybean.

E1, a potential B3-like transcription factor, may directly target downstream genes involved in leaf development. We performed RNA-seq and found a significant enrichment in E1-OE transgenic soybean plants of metabolic pathways essential for plant growth and development (Fig. 3d). Therefore, E1 may regulate leaf development through metabolic signaling pathways in soybean. Furthermore, Furthermore, among the TF families previously identified by RNA-seq, such as the AP2/ERF-ERF, bHLH, MYB, WRKY, NAC, HB-HD-ZIP, C2H2, GRAS, bZIP, MYB-related, TCP and B3-ARF TFs (Fig. 4a). CIN-type TCP genes in particular appear to regulate leaf development [9, 12, 13]. For example, CIN-like TCP proteins promote leaf differentiation by regulating the meristematic and auxin response genes in Arabidopsis [46]. In soybean, we found that most CIN-type TCP genes were down-regulated in E1-OE lines. E1 also repressed TCP14 and TCP29 expression in transient expression assay, and our ChIP-qPCR analysis demonstrated that E1 directly binds to the TCP14 and TCP29 promoter (Fig. 5d). Therefore, E1 may directly repress CIN-type TCP genes to regulate the leaf development in soybean.

Conclusions

Based on our data, we determined that the overexpression of E1 could affect leaf development in soybean by directly repressing a large number of leaf development-related CIN-type TCP genes. E1, therefore, regulates leaf development and flowering time. Our findings provide important information into the molecular mechanism underlying leaf development in soybean.

Methods

Plasmid construction and soybean transformation

For overexpression and EI-Flag fusion constructs, we amplified the coding sequence (CDS) of E1 using the primer set E1Flag-F/E1Flag-R. The amplicon was inserted into PTF101-3Flag under the control of a CaMV35S promoter. The PCR conditions were as follows: 94 °C for 2 min followed by 30 cycles at 94 °C for30s, 55 °C for 30s, and 72 °C for 30s and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. Cotyledonary nodes from DN50 and W82 were used as explants for the Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation method described by Paz et al. [47]. Transgenic soybean plants (T1) were identified by PCR amplification and western blot hybridization, and then were advanced to T7 for further analysis. All primers used for vector construction, PCR, and qRT-PCR assays for target genes are listed in Additional file 4: Table S1.

Materials and growth conditions

DN50 and W82, were obtained from the Innovative Center of Molecular Genetics and Evolution, School of Life Sciences, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou, and subsequently used for transformation and experiments. The E1-OE transgenics and wild types (W82, DN50) were grown in a chamber maintained at 25 °C and 70% relative humidity with a 16 h light/ 8 h dark cycle. Plants were phenotyped 7 days after emergence (DAE).

Nicotiana benthamiana was obtained from the Innovative Center of Molecular Genetics and Evolution, School of Life Sciences, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou, and used for transactivation assays. The N.benthamiana seeds were grown in a chamber maintained at 22 °C and 70% relative humidity with a 12 h light/ 12 h dark cycle. Twenty days after planting, the leaves were used for transient transformation.

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

qRT-PCR analysis was performed to determine the transcript abundance of E1. Total RNA was isolated from DN50 soybean leaf, cotyledon, pod, flower, shoot, seed, nodule and root using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was synthesized using Oligo (dT) 18 primer and the First cDNA transcriptase kit (Takara, Dalian, China). qRT-PCR was performed using a LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) in Roche LightCycler480 system (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The soybean housekeeping gene Tubulin was used as the internal control. The relative transcript level of the target gene was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Three biological replicates with three technical replicates each were performed.

RNA-seq analysis

Two independent EI-OE transgenic lines and two DN50 plants grown for 20 days in the greenhouse were used for RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis. Total RNA was extracted from leaves using the Spectrum Plant Total RNA Kit (Sigma-Aldrich). The RNA was sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform to generate paired-end reads. DEGs between samples were defined by DESeq using two separate models [48], based on fold change > 2 and false discovery rate–adjusted P value < 0.05. DEGs were then subjected to enrichment analysis of Gene Ontology (GO) functions and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways.

Transient expression assay

A transient dual-luciferase assay was performed as previously described [49]. Briefly, p35S:E1-Flag was used in effector constructs and the 2027 bp and 2209 bp promoter sequences of TCP14 and TCP29 were cloned using gene-specific primers pTCP14/29luc-F/R and inserted into the pGreen-0800-LUC vector. The reporter construct pTCPs:LUC and the effector constructs p35S:E1-Flag were transformed into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 and transfected into healthy leaves of 21-d-old N. benthamiana tobacco leaves by agroinfiltration as described previously [26, 50]. The plants were placed under continuous white light for 3 d after infiltration, leaf samples were collected for the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System kit (Promega, USA). Relative LUC activity was normalized against the renilla luciferase (REN) activity, and the data presented are the averages of at least three independent replicates.

Protein extraction and immunoblotting

To analyze protein expression in transgenics, total proteins were extracted according to the protocol of Cheng et al. [26]. Total proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Germany) and probed using anti-Flag antibodies (Sigma).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation–qPCR assays

For chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)–qPCR assays, DN50 and E1-OE transgenic lines were subjected to chromatin extraction and immunoprecipitation as described by Saleh et al. [51]. The precipitated DNA was recovered and analyzed by qRT-PCR with LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The precipitated input DNA samples were analyzed by qPCR using gene-specific primers. The data were normalized to input transcript levels and the means represent three biological replicates.

Tissues expression profile analysis

The expression data for TCP genes in different tissues, including leaf, shoot, root, flower, seed, pod, cotyledon, and nodule, were available in the RNA-seq database [52]. TBtools [53] was used to display the expression profile of TCP genes in the heatmap.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets and materials developed and analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The RNA-seq data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in to NCBI with accession number PRJNA749473 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA749473).

Abbreviations

- E1-OE:

-

E1-overexpression

- DN50:

-

DongNong 50

- W82:

-

Williams 82

- CIN:

-

CINCINNATA

- TCP:

-

TEOSINTE BRANCHED1/CYCLOIDEA/PROLIFERATING CELL FACTOR

- WT:

-

Wild type

- LD:

-

Long-day

- JAW:

-

JAGGED AND WAVY

- CYC/TB1:

-

CYCLOIDEA/ TEOSINTE BRANCHED1

- CTR:

-

Cell tense ratio

- SR:

-

Spongy tissue ratio

- DEGs:

-

Differentially expressed genes

- TF:

-

Transcription factor

- nal7:

-

Narrow leaf 7

- ADL1:

-

Adaxialized leaf 1

- CDS:

-

Coding sequence

- qRT-PCR:

-

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR

- RNA-seq:

-

RNA-sequencing

- GO:

-

Gene Ontology

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- REN:

-

Renilla luciferase

- ChIP:

-

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

References

Kougioumoutzi E, Cartolano M, Canales C, Dupre M, Bramsiepe J, Vlad D, et al. SIMPLE LEAF3 encodes a ribosome-associated protein required for leaflet development in Cardamine hirsute. Plant J. 2013;73:533–45.

Xue J, Luo D, Xu D, Zeng M, Cui X, Li L, et al. CCR1, an enzyme required for lignin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis, mediates cell proliferation exit for leaf development. Plant J. 2015;83:375–87.

Matsumoto H, Yasui Y, Ohmori Y, Tanaka W, Ishikawa T, Numa H, et al. CURLED LATER1 encoding the largest subunit of the Elongator complex has a unique role in leaf development and meristem function in rice. Plant J. 2020;104:351–64.

Gaillochet C, Lohmann JU. The never-ending story: from pluripotency to plant developmental plasticity. Development. 2015;142:2237–49.

Szymanski DB. The kinematics and mechanics of leaf expansion: new pieces to the Arabidopsis puzzle. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2014;22:141–8.

Ichihashi Y, Tsukaya H. Behavior of leaf meristems and their modification. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:1060.

Zhang J, Wei B, Yuan R, Wang J, Ding M, Chen Z, et al. The Arabidopsis RING-type E3 ligase TEAR1 controls leaf development by targeting the TIE1 transcriptional repressor for degradation. Plant Cell. 2017;29:243–59.

Reinhardt B, Hänggi E, Müller S, Bauch M, Wyrzykowska J, Kerstetter R, et al. Restoration of DWF4 expression to the leaf margin of a dwf4 mutant is sufficient to restore leaf shape but not size: the role of the margin in leaf development. Plant J. 2007;52:1094–104.

Uberti-Manassero NG, Lucero L, Viola IL, Vegetti AC, Gonzalez DH. The class I protein AtTCP15 modulates plant development through a pathway that overlaps with the one affected by CIN-like TCP proteins. J Exp Bot. 2012;63:809–23.

Ori N, Cohen AR, Etzioni A, Brand A, Yanai O, Sharona S, et al. Regulation of LANCEOLATE by miR319 is required for compound-leaf development in tomato. Nat Genet. 2007;39:787–91.

Palatnik JF, Wollmann H, Schommer C, Schwab R, Boisbouvier J, Rodriguez R, et al. Sequence and expression differences underlie functional specialization of Arabidopsis microRNAs miR159 and miR319. Dev Cell. 2007;13:115–25.

Palatnik JF, Allen E, Wu X, Schommer C, Schwab R, Carrington JC, et al. Control of leaf morphogenesis by microRNAs. Nature. 2003;425:257–63.

Danisman S, van der Wal F, Dhondt S, Waites R, de Folter S, Bimbo A, et al. Arabidopsis class I and class II TCP transcription factors regulate jasmonic acid metabolism and leaf development antagonistically. Plant Physiol. 2012;159:1511–23.

Owen FV. Inheritance studies in soybeans. II. Glabrousness, color of pubescence, time of maturity, and linkage relations. Genetics. 1927;12:519–29.

Bernard RL. Two major genes for time of flowering and maturity in soybeans. Crop Sci. 1971;11:242–4.

McBlain BA, Bernard RL, Cremeens CR, Korczak JF. A procedure to identify genes affecting maturity using soybean isoline testers. Crop Sci. 1987;27:1127–32.

Tsubokura Y, Watanabe S, Xia ZG, Kanamori H, Yamagata H, Kaga A, et al. Natural variation in the genes responsible for maturity loci E1, E2, E3 and E4 in soybean. Ann Bot. 2014;113:429–41.

Cao D, Takeshima R, Zhao C, Liu B, Jun A, Kong F. Molecular mechanisms of flowering under long days and stem growth habit in soybean. J Exp Bot. 2017;68:1873–84.

Xia Z, Watanabe S, Yamada T, Tsubokura Y, Nakashima H, Zhai H, et al. Positional cloning and characterization reveal the molecular basis for soybean maturity locus E1 that regulates photoperiodic flowering. PNAS. 2012;109:12852–3.

Xu ML, Xu ZH, Liu BH, Kong FJ, Tsubokura Y, Watanabe S, et al. Genetic variation in four maturity genes affects photoperiod insensitivity and PHYA-regulated post-flowering responses of soybean BMC Plant Biol 2013; 13: 91.

Lu SJ, Zhao XH, Hu YL, Liu SL, Nan HY, Li XM, et al. Natural variation at the soybean J locus improves adaptation to the tropics and enhances yield. Nat Genet. 2017;49:773–9.

Lu SJ, Dong LD, Fang C, Liu SL, Kong LP, Cheng Q, et al. Stepwise selection on homeologous PRR genes controlling flowering and maturity during soybean domestication. Nat Genet. 2020;52:1–9.

Kong FJ, Liu BH, Xia ZJ, Sato S, Kim BM, Watanabe S, et al. Two coordinately regulated homologs of FLOWERING LOCUS T are involved in the control of photoperiodic flowering in soybean. Plant Physiol. 2010;154:1220–31.

Thakare D, Kumudini S, Dinkins RD. The alleles at the E1 locus impact the expression pattern of two soybean FT-like genes shown to induce flowering in Arabidopsis. Planta. 2011;234:933–43.

Watanabe S, Xia ZJ, Hideshima R, Tsubokura Y, Sato S, Yamanaka N, et al. A map-based cloning strategy employing a residual heterozygous line reveals that the GIGANTEA gene is involved in soybean maturity and flowering. Genetics. 2011;188:395–U260.

Cheng Q, Dong LD, Gao TJ, Liu TF, Li NH, Wang L, et al. The bHLH transcription factor GmPIB1 facilitates resistance to Phytophthora sojae in Glycine max. J Exp Bot. 2018;69:2527–41.

Takeshima R, Nan HY, Harigai K, Dong LD, Zhu JH, Lu SJ, et al. Functional divergence between soybean FLOWERING LOCUS T orthologues FT2a and FT5a in post-flowering stem growth. J Exp Bot. 2019;70(15):3941–53.

Cubas PN, Doebley J, Coen E. The TCP domain: a motif found in proteins regulating plant growth and development. Plant J. 1999;18:215–22.

Aggarwal P, Das Gupta M, Joseph AP, Chatterjee N, Srinivasan N, Nath U. Identification of specific DNA binding residues in the TCP family of transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2010;22:1174–89.

Feng ZJ, Xu SC, Liu N, Zhang GW, Hu QZ, Gong YM. Soybean TCP transcription factors: evolution, classification, protein interaction and stress and hormone responsiveness. Plant Physiol Bioch. 2018;127:129–42.

Nath U, Crawford BC, Carpenter R, Coen E. Genetic control of surface curvature. Science. 2003;299:1404–7.

Koyama T, Furutani M, Tasaka M, Ohme-Takagi M. TCP transcription factors control the morphology of shoot lateral organs via negative regulation of the expression of boundary-specific genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:473–84.

Efroni I, Blum E, Goldshmidt A, Eshed Y. A protracted and dynamic maturation schedule underlies Arabidopsis leaf development. Plant Cell. 2008;20:2293–306.

Scanlon MJ, Schneeberger RG, Freeling M. The maize mutant narrow sheath fails to establish leaf margin identity in a meristematic domain. Development. 1996;122:1683–91.

Han J, Guo B, Guo Y, Zhan B, Wang X, Qiu LJ. Creation of early flowering germplasm of soybean by CRISPR/ Cas9 technology. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:1446.

Takahashi N. Linkage relation between the genes for the form of leaves and the number of seeds per pod of soybeans. Jpn J Genet. 1934;9:208–25.

Domingo WE. Inheritance of number of seeds per pod and leaflet shape in the soybean. Span J of Agric Res. 1945;70:251–68.

Weiss MG. Genetic linkage in soybeans. Linkage group IV. Crop Sci. 1970;10:368–70.

Dinkins RD, Keim KR, Farno L, Edwards LH. Expression of the narrow leaflet gene for yield and agronomic traits in soybean. J Hered. 2002;93:346–51.

Jeong N, Moon JK, Kim HS, Kim CG, Jeong SC. Fine genetic mapping of the genomic region controlling leaflet shape and number of seeds per pod in the soybean. TAG. 2011;122:865–74.

Jeong N, Suh SJ, Kim MH, Lee S, Moon JK, Kim HS, et al. Ln is a key regulator of leaflet shape and number of seeds per pod in soybean. Plant Cell. 2012;24:4807–18.

Hibara KI, Obara M, Hayashida E, Abe M, Ishimaru T, Satoh H, et al. The ADAXIALIZED LEAF1 gene functions in LEAF and embryonic pattern formation in rice. Dev Biol. 2009;334:345–54.

Price AH, Young EM, Tomos AD. Quantitative trait loci associated with stomatal conductance, leaf rolling and heading date mapped in upland rice (Oryza sativa L.). New Phytol. 1997;137:83–91.

Fujino K, Matsuda Y, Ozawa K, Nishimura T, Koshiba T, Tomokazu F, et al. NARROW LEAF 7 controls LEAF shape mediated by auxin in rice. Mol Genet and Genomics. 2008;279:499–507.

Woo YM, Park HJ, Su'udi M, Jl Y, Park JJ, Back K, et al. Constitutively wilted 1, a member of the rice YUCCA gene family, is required for maintaining water homeostasis and appropriate root to shoot ratio. Plant Mol. Biol. 2007;65:125–36.

Koyama T, Mitsuda N, Seki M, Shinozaki K, Ohme-Takagi M. TCP transcription factors regulate the activities of ASYMMETRIC LEAVES1 and miR164, as well as the auxin response, during differentiation of LEAVES in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2010;22:3574–88.

Paz MM, Martinez JC, Kalvig AB, Fonger TM, Wang K. Improved cotyledonary node method using an alternative explant derived from mature seed for efficient Agrobacterium-mediated soybean transformation. Plant Cell Rep. 2006;25:206–13.

Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106.

Shang Y, Yan L, Liu ZQ, Cao Z, Mei C, Xin Q, et al. The mg-chelatase H subunit of Arabidopsis antagonizes a group of WRKY transcription repressors to relieve ABA-responsive genes of inhibition. Plant Cell. 2010;22:1909–35.

Meng Y, Li H, Wang Q, Liu B, Lin C. Blue light-dependent interaction between cryptochrome2 and CIB1 regulates transcription and leaf senescence in soybean. Plant Cell. 2013;25:4405–20.

Saleh A, Alvarez-Venegas R, Avramova Z. An efficient chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) protocol for studying histone modifications in Arabidopsis plants. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1018–25.

Machado FB, Moharana KC, Fabricio AS, Rajesh KG, Thiago MV. Systematic analysis of 1,298 RNA-Seq samples and construction of a comprehensive soybean (Glycine max) expression atlas. Plant J. 2020;103:1894–909.

Chen C, Chen H, Zhang Y, Thomas HR, Frank MH, He Y, et al. TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol Plant. 2020;13:1194–202.

Acknowledgements

We thank planteditors (http://planteditors.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32001508, 31930083, 31901568). The funding agencies provided only the experimental cost and publication fee for this work. However, the experimental design and data collection and analysis were managed by the contributing authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

QC, BHL and LDD designed the experiments. YLL, ZHH, WWL, HYL and SJL performed the research. ZRG, HD, TL, YHZ, FJK, MLH, LXM, CML, and YRL analysed the data. QC and LDD wrote the article. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1.

Phenotypes of E1 transgenic lines and DN50 plants under LD (long day, 16 h light/8 h dark) conditions. Fig. S2. The leaf phenotypic characterization of the E1-overexpression (E1-OE) plants in W82. Fig. S3. The transcription levels of TCP33, TCP36, TCP37, TCP39 and TCP42 in DN50 and E1-OE plants.

Additional file 2: Fig. S4.

Source data of full gel blot images for Fig.1a.

Additional file 3: Data S1.

List of genes with significant expression changes. (XLS 6546 kb)

Additional file 4: Table S1.

Primers used for PCR and qRT-PCR in this study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Hou, Z., Li, W. et al. The legume-specific transcription factor E1 controls leaf morphology in soybean. BMC Plant Biol 21, 531 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-021-03301-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-021-03301-1