Abstract

Background

Understanding and identifying the factors responsible for genetic differentiation is of fundamental importance for efficient utilization and conservation of traditional rice landraces. In this study, we examined the spatial genetic differentiation of 594 individuals sampled from 28 locations in Yunnan Province, China, covering a wide geographic distribution and diverse growing conditions. All 594 accessions were studied using ten unlinked target genes and 48 microsatellite loci, and the representative 108 accessions from the whole collection were sampled for resequencing.

Results

The genetic diversity of rice landraces was quite different geographically and exhibited a geographical decline from south to north in Yunnan, China. Population structure revealed that the rice landraces could be clearly differentiated into japonica and indica groups, respectively. In each group, the rice accessions could be further differentiated corresponded to their geographic locations, including three subgroups from northern, southern and middle locations. We found more obvious internal geographic structure in the japonica group than in the indica group. In the japonica group, we found that genetic and phenotypic differentiation were strongly related to geographical distance, suggesting a pattern of isolation by distance (IBD); this relationship remained highly significant when we controlled for environmental effects, where the likelihood of gene flow is inversely proportional to the distance between locations. Moreover, the gene flow also followed patterns of isolation by environment (IBE) whereby gene flow rates are higher in similar environments. We detected 314 and 216 regions had been differentially selected between Jap-N and Jap-S, Ind-N and Ind-S, respectively, and thus referred to as selection signatures for different geographic subgroups. We also observed a number of significant and interesting associations between loci and environmental factors, which implies adaptation to local environment.

Conclusions

Our findings highlight the influence of geographical isolation and environmental heterogeneity on the pattern of the gene flow, and demonstrate that both geographical isolation and environment drives adaptive divergence play dominant roles in the genetic differentiation of the rice landraces in Yunnan, China as a result of limited dispersal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Rice, as one of the world’s major food crops, feeds more people than any other crop species and is a staple crop for nearly all of Asia. Historically, rice yield has accounted for 40 % of the total grain output in China (Hu et al. 2002). Over the past 30 years, the phenomenon of large areas planted with single breeding varieties has increased the use of improved rice varieties, which has led to a narrow genetic base and an overall reduction in the genetic diversity of rice varieties grown in China (Xu et al. 2016).

Compared with improved varieties, traditional landraces are the products of natural and artificial selection that occurred over thousands of years. Landraces are grown by local farmers, and have been passed down from generation to generation. Landraces are defined as ‘‘geographically or ecologically distinctive populations (Pusadee et al. 2009), which are conspicuously diverse in their genetic composition both between landraces and within them,’’ (Brown 1978) and they are each identifiable by their unique morphologies and well-established local names (Harlan 1992). Landrace diversity is found throughout the cultivated range for rice, making the landraces a rich source of genetic variation that includes such characteristics as high grain quality, wide adaptability, strong environmental tolerance, disease and insect resistance, and cultural uses, and can provide a valuable gene pool for the discovery and utilization of favorable genes. However, over the past 50 years, local rice landraces have been largely replaced by genetically uniform, high-yielding modern varieties in many parts of China. Rice landraces are generally no longer planted in China, although there are exceptions in some ethnic minority regions in Yunnan or Guizhou.

Yunnan province is one of the important centers of genetic diversity for cultivated rice in China and throughout the world (Zhang et al. 2006). Over thousands of years of planting history, natural and artificial selection has preserved a large number of traditional rice landraces in Yunnan, due to its complex geographical environment, diverse climatic conditions, and rich national culture. A remarkably diverse set of rice landraces (including all varieties of Oryza sativa L. in China) are found in Yunnan, and include both indica and japonica types, those with glumes, with or without hairs, non-glutinous or glutinous, upland or lowland, naked rice, and rice with various hull grain colors (white, red, and purple) and flavors (ordinary or fragrant) (Zeng et al. 2000a; Zeng et al. 2000b).

By the late 1980s, there were 5,128 local rice landraces collected and catalogued in Yunnan, China. At present, many traditional rice landraces are still planted by indigenous farmers in the ethnic minority regions of Yunnan. These landraces have been passed down from generation to generation despite the availability of modern improved varieties, mainly due to reasons associated with the diversity of the local agro-ecology and also to fulfill cultural requirements (Xu et al. 2014). Indigenous farmers work to conserve the diverse traditional rice landraces on the farm, preferring not only highly productive landraces, but also those that are more resistant to diseases and pests and that display tolerance to extreme environmental conditions, as well as landraces that are of cultural importance (e.g., ethnic dietary customs, medicinal uses, festivals, and religious ceremonies) (Gao 2003). The rice landraces that are grown have desirable features, and they cannot easily be replaced by modern improved varieties because some of these landraces have been cultivated for > 50 years.

Rice landraces in Yunnan province are widely distributed over a region extending from 21° 8’ 32’’ N to 29° 11’ 18’’ N and 97° 31’ 39’’ E to 106° 11’ 47’ E (Zeng et al. 2007), and are planted at altitudes ranging from approximately 76.4 m in Hekou county to 2,695 m in Ninglang county in Yunnan (Xu et al. 2016). The heterogeneity of the environments and wide distribution of rice landraces provides an excellent opportunity for studies of genetic differentiation among populations in different geographical locations as well as for determining how geographical distance and environmental factors affect population genetic differentiation. Many studies have focused on population structure and genetic differentiation of rice landraces (Xiong et al. 2010; Xiong et al. 2011; Zeng et al. 2001). However, little is known about how geographical distance and environmental factors affect population genetic differentiation in the rice landraces of Yunnan province, China. Furthermore, the role of geographical or environmental isolation in genetic differentiation of rice landraces is still unclear.

We first collected 28 populations (594 individuals) of rice landraces that cover a wide geographical area and diverse growing conditions in Yunnan province, China, and analyzed ten gene sequences and 48 SSR (simple sequence repeat) markers. Then, a core subset of the collection of 594 landraces (108 accessions) was sampled for whole-genome sequencing. Our objectives were to examine the genetic structure and differentiation in rice landraces from Yunnan province, China, and to determine the relationships with their spatial and geographical distribution. We also discuss the role of geographical isolation and environmental heterogeneity in genetic differentiation among populations of rice landraces to provide theoretical support and a scientific basis for the protection and utilization of rice landraces.

Results

Genetic diversity

We sequenced ten unlinked gene segments from 594 accessions from 28 rice landrace populations in Yunnan (Table S1 and Figure S1). The length of the aligned sequences ranged from 420 to 627 bp for each gene locus, with a total length of 4,994 bp (Table S2 and Figure S2). The standard statistics of sequence polymorphisms for each locus are summarized in Table S3. The term θπ indicates the nucleotide diversity, which was calculated for each locus. This term ranged from 0.0023 (STS22) to 0.0149 (CatA) in rice landraces, with an average of 0.0060. The haplotype diversity varied from 0.501 (Os1977) to 0.788 (GS5), with an average of 0.655. Four-gamete testing revealed that the Rm ranged from 0 to 7 in rice landraces, with an average of 3, indicating that there was low heterozygosity in the rice landraces due to high levels of inbreeding. Neutrality test values for most gene loci were not significant, except Os1977 (D = 2.856) and Ehd1 (D = 2.280), indicating that most were neutral gene loci. Based on SSR markers, a total of 629 alleles were detected in all accessions, with an average of 13.10 per locus. The average gene diversity and PIC were 0.755 and 0.725, respectively (Table S4).

Standard sequence polymorphism statistics for each location are summarized in Table S5 and Fig. 1. For the gene loci, we observed genetic diversity, estimated by θπ, ranging from 0.0039 (Jianchuan, JC) to 0.0063 (Longchuan, LN), with an average of 0.0055. The haplotype diversity varied from 0.475 (Jianchuan, JC) to 0.671 (Ximeng, XM) (with an average of 0.610). Based on SSR markers, gene diversity, PIC, and heterozygosity ranged from 0.5082 to 0.7289, 0.4717 to 0.6928, and 0.0355 to 0.1264, respectively. Globally, the mean genetic diversity, PIC, and heterozygosity were 0.6729, 0.6318, and 0.0690, respectively. Correlation analysis indicated that genetic diversity was significantly negative with respect to latitude (Figure S3). In other words, the genetic diversity of rice landraces in Yunnan province, China showed a geographical decline from south to north.

Population structure and genetic relationships

The STRUCTURE analysis suggested K = 2 as the optimal number of clusters based on the calculation of ∆K (Figure S4). This suggests that the rice landraces can be grouped into two groups, referred to as P1 and P2. We found the 271 P1 accessions are japonica or japonica-like, and the 323 P2 accessions are indica or indica-like. This result indicated that rice landraces from Yunnan were clearly differentiated into japonica and indica groups (Figure S5a). We found both japonica- and indica-type landraces distributed in each location (Figure S5b). We further detected a significant positive correlation between the proportion of japonica rice landraces in various locations and latitudes (r = 0.367, P < 0.05), but a significant negative correlation between the proportion of indica rice landraces in various locations and latitudes (r = -0.367, P < 0.05) (Figure S6). In other words, the proportion of japonica landraces in each location in Yunnan increased from low to high latitudes. By contrast, the proportion of indica landraces in each location decreased from low to high latitudes. In each japonica or indica group, the neighbor-joining tree showed that the rice accessions could be clearly differentiated according to their geographic locations, including a cluster from northern locations, a cluster from southern locations, and other cluster from middle locations (Fig. 2). Moreover, we found more obvious geographic structure in the japonica group than in the indica group.

Unrooted neighbor-joining trees of the rice landraces from 28 locations based on Nei’s genetic distances in japonica (a) and indica (b) groups. Colours for rice landraces collected from different locations: red, from northern locations (N); green, from southern locations (S); blue, from middle locations (M)

In the japonica and indica groups, the first two components of the PCA accounted for 64.1 and 51.3 % of total variation, respectively, which were used to visualize the dispersion of the populations in a graph (Fig. 3). The result of PCA also showed geographic structure in the japonica group: we found that the rice accessions from northern locations were assigned to one cluster, the rice accessions from southern locations were assigned to one cluster, and rice accessions from locations in the middle were assigned to one cluster (Fig. 3a). In the indica group, we found less obvious geographic structure than in the japonica group, which was consistent with neighbor-joining tree (Fig. 3b).

Isolation by distance and environment

In the japonica group, there was an overall relationship between pairwise genetic differentiation and geographic distance matrices (Mantel test, R = 0.3757, P < 0.01; Table 1; Fig. 4a), suggesting a pattern of IBD, and this relationship remained highly significant after controlling for environmental effects (partial Mantel test, R = 0.3579, P < 0.01; Table 2). Similarly, genetic differentiation was strongly related to environmental distance (R = 0.3350, P < 0.01; Table 1; Fig. 4b), suggesting a pattern of IBE; this relationship remained highly significant when we controlled for geography-level effects (R = 0.3142, P < 0.01; Table 2). For the individual gene loci, we found significant correlations between genetic differentiation and geographical distance regardless of whether we accounted for environmental effects at only the GS5 locus (R = 0.3408, P < 0.01 and R = 0.3404, P < 0.01 respectively; Tables 1 and 2). Additionally, the positive genetic-environmental association was significant regardless of whether we accounted for geographical distance at only the STS90 locus (R = 0.2114, P < 0.05 and R = 0.2223, P < 0.05 respectively; Tables 1 and 2). In the indica group, genetic differentiation was not related to geographic distance, regardless of whether environmental effects were accounted for (R = -0.0054, P > 0.05 and R = -0.0076, P > 0.05 respectively; Tables 1 and 2). Similarly, genetic differentiation was not related to environmental distance, regardless of whether geography-level factors were accounted for (R = 0.0176, P > 0.05 and R = 0.0184, P > 0.05 respectively; Tables 1 and 2).

Like genetic differentiation, population-level pairwise morphological distance was significantly related to geographic/environmental distance (R = 0.2779, P < 0.01; R = 0.2597, P < 0.05; Fig. 4c and d), and this relationship remained significant after controlling for environmental/geographic effects (R = 0.2568, P < 0.01; R = 0.2367, P < 0.05; Table 2) in the japonica group. However, in the indica group, morphological distance was not related to geographic distance between populations (R = 0.1340, P > 0.05; Table 1), nor to environmental distance (R = 0.1512, P > 0.05; Table 2).

To further demonstrate gene flow among different populations, we estimated frequency changes of dominant haplotypes at the important gene Ehd1 (Early heading date 1) in different locations (Figure S7). The total number of haplotypes for Ehd1 was 15 and 18 in the japonica and indica group, respectively. Among these haplotypes, H_3 was widely distributed in Yunnan in the japonica group, whereas H_1 was widely distributed in the indica group, which indicates that these two haplotypes were favored in japonica or indica group. In addition, we found there were some distinct differences in haplotype frequency among rice landraces from different locations. For example, the frequency of H_1 varied from 7.69 % (Luoping, LP) to 80.00 % (Qiaojia, QJ) (with an average of 34.57 %) in the japonica group, and the frequency of H_3 varied from 5.88 % (Yuanyang, YY) to 66.67 % (Luoping, LP) (with an average of 21.45 %) in the indica group. Notably, there were some environment-specific haplotype which could be found only in one location, such as H_2, H_11 and H_14 in the japonica group, and H_2, H_4 and H_6 in the indica group.

Differential selection in the different geographic locations

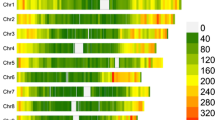

We used a composite likelihood ratio method (CLR) (Nielsen et al. 2005) to identify genomic regions differentially selected in the subgroups from different geographic locations. (Fig. 5). Regions with the strongest 5th percentile of CLR selection signals were considered (Nielsen et al. 2005). In the japonica group, 179 regions and 170 regions were identified as the most affected by selection in subgroup Jap-N (rice landraces from northern locations) and Jap-S (rice landraces from southern locations), respectively (Table S6-7). The selected regions of Jap-N had a mean size of 105.9 kb, covering 5.1 % of the rice genome, whereas those selected regions of Jap-S covered 5.0 % of the rice genome with a mean size of 110.95 kb. The selected regions of Jap-N and Jap-S contained 2,165 and 1,785 protein-coding genes, respectively (Table S6-7). In the indica group, we identified 140 potential selected regions with an average size of 134.7 kb in Ind-N (rice landraces from northern locations), comprising approximately 5.0 % of the rice genome, and 77 potential selected regions with an average size of 234.5 kb in Ind-S (rice landraces from southern locations), comprising approximately 4.8 % of the rice genome (Table S8-9). The selected regions of Ind-N and Ind-S contained 1,964 and 1,875 protein-coding genes, respectively (Table S8-9). Thirty-seven selected regions of Jap-N overlapped with 35 selected regions of Jap-S, containing 309 genes, and 52 selected regions of Ind-N overlapped with 37 selected regions of Ind-S, containing 984 genes. These results suggested that although different target genes were selected in different subgroups, some of the targets were common to the different subgroups.

As expected, we found a number of candidate genes included in the potential selected regions were important agronomic genes/quantitative trait loci (QTLs) released by Q-TARO (Yamamoto et al. 2012) (Table S10-11). We found the gene MYBS3 included in the selected regions of Jap-N on chromosome 10 (21.796–22.338 Mb, CLR = 332.87) (Fig. 5a), which were involved in cold stress response and cold tolerance (Su et al. 2010). Meanwhile, the region on chromosome 6 containing OsiSAP8 showed a selective-sweep signal (24.469–24.593 Mb, CLR = 1148.06) in Ind-N (Fig. 5c). This gene was also related to cold tolerance (Kanneganti and Gupta 2008). Whereas, the selection signals were detected in regions of Jap-S and Ind-S, which includes the TOGR1 and Spl7 genes (Fig. 5b and d). These genes are involved in response to high temperature (Wang et al. 2016; Yamanouchi et al. 2002). Additionally, many important genes such as Hd1 (Yano et al. 2000), Ehd4 (Gao et al. 2013), Gn1a (Ashikari et al. 2005), GIF1 (Wang et al. 2008), xa25 (Chen et al. 2002) and Bph14 (Du et al. 2009) were found in selected regions (Table S10). In total, we found 208 cloned agronomic genes in selected regions of Jap-N, Jap-S, Ind-N and Ind-S. Notably, these selective-sweep regions were extremely enriched in grain yield and plant type gene categories, followed by the abiotic stress resistance category (Figure S8). Furthermore, nearly all (96.6 %) of our selected regions were overlapped with previously reported agronomic QTLs (Table S11).

Genomic signatures of local adaptation

To screen genomes for signatures of local adaptation, we tested for associations between genetic variation and environmental variables using Latent Factor Mixed Models (LFMM) (Frichot et al. 2013). A total of 1346 SNPs that obtained |z|-scores greater than 6 (P < 10− 10) (Table S12) were associated with environmental variables. Among these SNPs, we found the SNP (|z| = 7.02) located at 2.22 Mb on chromosome 3 was in the gene region of sd37 involving in plant height in rice (Zhang et al. 2014), which indicated this candidate gene might be related to adaptation to the local environment (Table S13). We also found a significant SNP (|z| = 6.90) on chromosome 9 in the gene OsMYBc (Table S13), which is involved in salt tolerance (Wang et al. 2015), reflecting its adaption to the local environment. Among these SNPs significantly correlated with environmental variables, several notable examples include candidate genes involved in heading date (OsRR1 and OsRRM) (Cho et al.2016; Chen et al. 2007), grain shape (GL7 and BG2) (Yang et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2015), plant height (CYP734A4 and OsIAGLU) (Choi et al. 2012; Qian et al. 2017), disease resistance (OsCERK1 and JAmyb) (Cao et al. 2015; Huang et al. 2020), and heat tolerance (HSP70) (Breusegem et al. 1994), etc. (Table S13). All of these significant associations between loci/genes and environmental variables imply adaptation to the local environment. In total, in terms of the loci with high levels of association with environmental variables, we found 190 loci were also in the selected regions, which indicates that loci involving local adaptation have been particularly targeted in selection (Figure S9 and Table S12).

Discussion

Owing to the wide geographical variation, diverse growing conditions, and cultural and ethnic diversity, Yunnan is acknowledged as one of the largest genetic diversity centers for rice in China and even worldwide (Zeng et al. 2001; Zhang et al. 2006; Zeng et al. 2007). In the present study, we analyzed the genetic diversity in rice landraces sampled from 28 locations that cover a broad geographical distribution including the diverse growing conditions in Yunnan province, China. We found the average haplotype diversity, gene diversity, and PIC were 0.655, 0.755, and 0.725, respectively (Table S3-4), which indicated there was a high level of genetic diversity in landraces from Yunnan and these landraces were extremely important for enriching the rice gene pool. We calculated the genetic diversity in each location measured by θπ and PIC, which ranged from 0.0039 to 0.0063 and 0.4717 to 0.6928, respectively (Table S5), indicating that the patterns of genetic diversity are quite different geographically. Further analysis found the genetic diversity of rice landraces in Yunnan shows a geographic decline from south to north (Fig. S3). This result is consistent with the results of previous studies (Zhang et al. 2006; Zeng et al. 2007), which reported that the southwest region of Yunnan, encompassing the Simao, Lincang, and Xishuangbanna districts, is the center of genetic diversity for Yunnan rice landraces. In Yunnan, the common wild rice (O. ruffipogon Griff.), a direct ancestor of cultivated rice, is only found in Yuanjiang, Yuxi (the south-central region of Yunnan) and Jinghong, Xishuangbanna (the southwest region of Yunnan). Gene flow between landraces and their wild relatives greatly enhances the genetic variation of rice landraces in the genetic diversity center.

One important result of our study is the finding that genetic and phenotypic differentiation among rice landraces in the japonica group showed obvious geographic structure. However, we found less obvious internal geographic structure in the indica group. This result was consistent with a previous study: Xiong et al. found that the geographic distribution of indica and japonica rice landraces showed different patterns in Yunnan, China. The indica rice landraces with broad adaptability were widely distributed in the area between 2°S to 40°N, while the japonica rice landraces were obviously concentrated around 15°N (Xiong et al. 2011). Notably, a significant IBD pattern was revealed within the japonica group. The IBD pattern was further confirmed when the influence of environmental factors was considered (Table 2). This suggested that geographic isolation is one of the main factors influencing gene flow among the populations of the japonica rice landraces, implying that gene flow is more likely to occur between nearby locations. The pattern of IBD was highly associated with limited gene flow among populations due to affecting the spread of pollen and seeds. For inbred cultivated rice, where little to no pollen flow occurs, gene flow must occur by seed movement, and specifically by seed exchange among farmers (Pusadee et al. 2009). Farmers from the same or different locations establish networks and exchange their own seeds with others engaged in farming and cultural activities. In the ethnic minority regions of Yunnan province, seed exchange among indigenous farmers is also frequent. Seed exchange typically occurs between relatives, neighbors, friends, or through marriage patterns, and directly influences farmers’ seed exchange preferences whether within or between locations. Exchange among locations most often occurs between neighboring locations. Similar results were found in a previous study, where seed exchange between close communities played a role in reducing population structure in the rice landrace Bue Chomee in Thailand (Pusadee et al. 2009). Generally, differentiation occurs between locations, reflecting more limited seed exchange. For example, the local people in southern Yunnan are minority nationalities and live on rice. Daizu people dwell in the flatlands and enjoy eating glutinous rice, while Lahuzu people dwell in medium or highly mountainous regions and preferred red rice varieties. Therefore, seed exchange might be restricted between these locations under these circumstances, i.e., geographical isolation, traffic restriction, language, and custom barriers (Gao 2003).

Notably, our results revealed that gene flow among rice landrace populations also followed patterns of IBE for the japonica group, whereby gene flow rates are higher among similar environments. It indicated that environmental heterogeneity was essential in the genetic differentiation of japonica rice landraces in Yunnan as a result of limited dispersal. Additionally, the geographic distribution of haplotypes revealed the frequency changes of haplotypes at the important gene Ehd1 (Early heading date 1) in different geographic locations and further demonstrated that both adaptation to local environment and environment-dependent gene flow played key roles in the genetic differentiation of rice landraces in Yunnan, China. Different environmental conditions (e.g., altitude, temperature, rainfall) can affect the survival and reproduction of plants and populations; thus, divergence might be due to local adaptation (Ohsawa and Ide 2008; Frei 2014). Local adaption may be enhanced with IBE. Under IBE, adaptation may be faster under stable environment conditions if populations from similar environments are exchanging beneficial alleles; however, with rapid environmental change, IBE could result in maladaptation if alleles from dissimilar environments are required for rapid adaptation (Sexton et al. 2014).

We next considered the potential role of natural and farmer selection in population genetic differentiation in rice landraces. We performed a genome-wide scan for signatures of selective sweeps to identify genomic regions differentially selected in the subgroups from different geographic locations. In the japonica group, 179 regions and 170 regions were identified as the most affected by selection in subgroup Jap-N and Jap-S, respectively. Similarly, we identified 140 and 77 potential selected regions in Ind-N and Ind-S, respectively. As expected, we found a number of candidate genes included in the potential selected regions and they were enriched in the grain yield category, followed by the plant-type and abiotic stress resistance categories, while enrichment was quite low in the eating quality category (Fig. S7). The results indicated selection for adaptation to each local environment results in rice landraces with high levels of local adaptation to abiotic and biotic stresses as well as for agricultural traits. For example, the rice landraces in Jap-N and Ind-N were from relatively high latitudes and we found that the genes involved in cold stress response and cold tolerance were included in the selected regions in these two subgroups. On the contrary, the rice landraces in Jap-S and Ind-S were from relatively low latitudes and we found that the genes involved in heat tolerance were included in the selected regions in these two subgroups. We also observed a number of significant and interesting associations between loci and environmental factors, which implies adaptation to local environment. Among these loci, we found 190 loci were also in the selected regions, which indicates that loci involving local adaptation have been particularly targeted in selection. Furthermore, different ethnic groups maintain and grow their own rice landraces for highly specific uses (e.g. ethnic dietary customs, medicinal uses, festivals, and religious ceremonies) (Gao 2003). The traditional cultures of these indigenous farmers has also resulted in population differentiation for the rice landraces of Yunnan.

Conclusions

Our findings highlight the influence of geographical isolation and environmental heterogeneity on the pattern of the gene flow, and demonstrate that both geographical isolation and environmental heterogeneity were essential in the genetic differentiation of rice landraces in Yunnan province, China. Our study provides the theoretical support and a scientific basis for the protection and utilization of rice landraces.

Methods

Sample collection and choice of loci

We performed a large scale analysis of 594 rice landrace accessions collected from 28 sites that cover a wide geographical distribution and diverse growing conditions (Table S1). The sampled populations represent most of the genetic diversity present in rice landraces in Yunnan, China (Figure S1). We carefully collected between seven and 39 rice landrace accessions from each location based on the population size. In each location, we selected samples which can represent most of the diversity within Yunnan rice landraces in order to reduce sampling error as much as possible. All 594 accessions were studied using ten unlinked target genes and 48 microsatellite loci, and a core subset of the collection of 594 landraces (108 accessions) (Table S1) was sampled for whole-genome sequencing. The sequence data were released in our previous study (Cui et al. 2020).

A set of 48 SSRs with high polymorphism that map to loci evenly distributed throughout the rice genome (Table S14) and ten unlinked nuclear genes were used in this study. Five of the genes – CatA, GBSSII, Os1977, STS22, and STS90 – had been used to estimate nucleotide diversity in rice populations in previous studies (Caicedo et al. 2007; Cui et al. 2016). We also used five additional genes – Ehd1, Pid3, GS3, GS5, and S5 – that are known to be associated with environmental adaptation and important agronomic traits in rice (Doi et al. 2004; Chen et al. 2008; Shang et al. 2009; Mao et al. 2010; Li et al. 2011). Schematic diagrams of the structures of all ten genes are shown in Figure S2. Detailed information about the genomic location and putative functions of the genes, as well as the primer sequences for amplifying them, can be found in Table S2.

DNA extraction, SSR genotyping, and gene sequencing

Total genomic DNA was extracted from fresh seedling leaves using a modified CTAB procedure (Doyle and Dickson 1987). The 48 SSRs were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with fluorescently labeled primers in 10-µL reactions containing 20 ng of genomic DNA, 1 µl 10× PCR reaction buffer, 10 mM mixed dNTPs, 2 µM primers, and 0.5 units of Taq polymerase. The PCR profile consisted of a pre-denaturation step of 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 36 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55–60 °C (depending on primer sequences) for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 40 s, with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were size separated on a 3730XL DNA Sequencer equipped with GENESCAN software (ABI, Waltham, MA, USA). Fragment sizes were recorded using Gene Marker V1.6 (SoftGene, State College, PA, USA) and manually re-checked.

To detect genes, PCR was performed in a 25-µL volume consisting of 0.2 µM of each primer, 200 µM of each dNTP, 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 U of HiFi DNA polymerase (Transgen, Beijing, China), and 10–30 ng of genomic DNA. The PCR amplification profile was as follows: pre-denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 36 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55–60 °C (depending on the primers) for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1.5 min, with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR products were electrophoresed on 1.2 % agarose gels, and DNA fragments were excised from the gel and purified using a Tiangen Gel Extraction Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). DNA sequencing reactions were performed using an ABI 3730 Automated Sequencer. Initially, all samples were directly sequenced. However, if the haplotypes could not be readily inferred owing to heterozygosity, the PCR products were ligated into a pGEM®-T Easy Vector (Transgen) and at least four clones were then sequenced. For heterozygous individuals, one allele sequence was randomly selected. Because Taq amplification errors can occur, when a polymorphism was found in only one accession, this accession was re-sequenced after cloning the amplified DNA fragment to verify the polymorphism.

Analysis of DNA sequences and SSR data

DNA sequences were aligned using ClustalX 1.83 (Thompson et al. 1997) and edited using BioEdit 7.0.9.0 (Hall 1999). Indels were not included in the analysis. For each locus, we determined the number of segregating sites (S), the number of haplotypes (h), the haplotype diversity (Hd), and two nucleotide diversity parameters, mean pairwise differences (θπ) (Nei 1987) and Watterson’s estimator, based on the number of segregating sites (θw) (Watterson 1975), using DnaSP version 5.0 (Rozas 2009). Statistical analysis of the SSR data, including allele number, genotype number, heterozygosity, gene diversity, and polymorphism information content (PIC), was performed using methods implemented in PowerMarker version 3.25 (Liu and Muse 2005).

Population genetic structure

To identify population structure, a Bayesian clustering analysis was conducted using STRUCTURE 2.2 (Pritchard et al. 2000; Falush et al. 2003) based on data for the 48 SSRs. Fifteen independent runs were performed for each k value (from 1 to 12), using a burn-in length of 100,000, a run length of 100,000, and admixture and correlated allele frequency models. The k value was determined based on LnP(D) in the STRUCTURE output and the ad-hoc statistic Δk (Evanno et al. 2005). We constructed a neighbor-joining tree using a matrix of pairwise genetic distances of 28 populations, calculated by PowerMarker version 3.25 (Liu and Muse 2005), and with tree visualization in MEGA 7.0 (Kumar et al. 2016). Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed with NTSYSpc software version 2.11 (Rohlf 2000).

Isolation by distance and environment

Pairwise FST was calculated using Arlequin 3.5 (Excoffier and Lischer 2010). Population-level pairwise genetic differentiation as FST/(1-FST) (Slatkin 1995) was measured. Isolation by distance (IBD) was evaluated by assessing the correlation matrix between pairwise geographical distance and genetic differentiation between locations was assessed using Mantel tests. A total of 100,000 random permutations were performed. The analyses above were performed using methods implemented in Arlequin 3.5 (Excoffier and Lischer 2010 ).

We reduced the environmental variables using principal component analysis (PCA) based on the 24 environmental variables (Table S15) in SAS version 8.02. With PCA, we kept the first two axes as environmental variables because they explained 82.26 % of the environmental variation, and they were used to calculate the environmental dissimilarity. Prior to analysis, all environmental variables were standardized. The correlations between genetic differentiation and geographic/environmental factors were determined by partial Mantel tests. The environmental distance between populations was the Euclidean distance calculated with the values of the PCA axes. Partial Mantel tests with 100,000 permutations were performed between genetic factors and one factor under the influence of the other, using the “ecodist” package in R (Goslee and Urban, 2007). Because we identified two genetic clusters corresponding to the indica and japonica subpopulations (see results), partial Mantel tests were also conducted separately in each subpopulation.

Morphometric analyses

To visualize the level of morphological structure across locations, we conducted a PCA of fifteen morphological traits (Table S16) and plotted the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2). We tested whether morphological differences between locations were the product of isolation by distance (IBD) or by environment (IBE) using the same rationale as for the genetic data. We calculated Euclidean distances in morphology between all pairs of locations, using the mean values per population of the fifteen morphometric traits (i.e. we obtained a single matrix of Euclidean distances in fifteen-dimensional space) (Table S16). Morphometric traits were standardized in the same manner as for environmental variables. We tested whether morphometric distance was related to geographic distance and environmental distance using Mantel tests and partial Mantel tests.

Selection analyses

A total of 2,771,245 high-quality SNPs of the representative 108 accessions were used for selection analyses. The sequence data were released in our previous study (Cui et al. 2020).

To detect regions with significant signatures of selective sweep, we performed a genome scan using a composite likelihood ratio method CLR (Nielsen et al. 2005) to calculate the candidate selected regions. A 10-kb sliding window across the whole genome was used for scanning. The highest CLR values, accounting for 5 % of the genome, were considered as selected regions.

Environmental association analysis

Latent factor mixed models (LFMM) (Frichot et al. 2013) were used to identify genetic variants associated with 3 environmental variables representing the 3 first components of a PCA for 24 environmental factors. The K-value was set to 2 based on the eigenvalues of the PCA of the genetic data as the number of latent factors. Five replicates were verified for convergence. The median z-scores of five runs was used to re-adjust the p-values. For an expected value of the FDR (q = 5 %), a list of candidate loci was obtained by using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure.

Availability of data and materials

All data supporting the conclusions of this article are provided within the article (and its additional files).

References

Ashikari M, Sakakibara H, Lin SY, Yamamoto T, Takashi T, Nishimura A et al (2005) Cytokinin Oxidase Regulates Rice Grain Production. Science 309(741):741–745

Breusegem FV, Dekeyser R, Garcia AB, Claes B, Gielen J, Montagu MV et al (1994) Heat-inducible rice hsp82 and hsp70 are not always co-regulated. Planta 193(1):57–66

Brown AHD (1978) Isozymes, plant population genetics structure and genetic conservation. Theor Appl Genet 52:145–157

Caicedo AL, Williamson SH, Hernandez RD, Boyko A, Fledel-Alon A, York TL et al (2007) Genome–wide patterns of nucleotide polymorphism in domesticated rice. PLoS Genet 3:1745–1756

Cao WL, Chu RZ, Zhang Y, Luo J, Su YY, Xie LJ (2015) OsJAMyb, a R2R3-type MYB transcription factor, enhanced blast resistance in transgenic rice. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 92:154–160

Chen HL, Wang SP, Zhang QF (2002) New Gene for Bacterial Blight Resistance in Rice Located on Chromosome 12 Identified from Minghui 63, an Elite Restorer Line. Phytopathology 92(7):750–754

Chen SY, Wang ZY, Cai XL (2007) OsRRM, a Spen-like rice gene expressed specifically in the endosperm. Cell Res 17(8):713–721

Chen JJ, Ding JH, Ouyang YD, Du HY, Yang JY, Cheng K et al (2008) A triallelic system of S5 is a major regulator of the reproductive barrier and compatibility of indicaÐjaponica hybrids in rice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105:11436–11441

Cho LH, Yoon J, Pasriga R, An G (2016) Homodimerization of Ehd1 Is Required to Induce Flowering in Rice. Plant Physiol 170(4):2159–2171

Choi MS, Koh EB, Woo MO, Piao RH, Oh CS, Koh HJ (2012) Tiller formation in rice is altered by overexpression of OsIAGLU gene encoding an IAA-conjugating enzyme or exogenous treatment of free IAA. Journal of Plant Biology, 2012, 55(6): 429–435

Cui D, Li JM, Tang CF, Yu AXX, Ma TQ XD, et al (2016) Diachronic analysis of genetic diversity in rice landraces under on-farm conservation in Yunnan, China. Theor Appl Genet 129:155–168

Cui D, Lu HF, Tang CF, Li JM, A XX, Yu TQ et al (2020) Genomic analyses reveal selection footprints in rice landraces grown under on-farm conservation conditions during a short-term period of domestication. Evol Appl 13:290–302

Doi K, Izawa T, Fuse T, Yamanouchi U, Kubo T, Shimatani Z et al (2004) Ehd1, a BÐtype response regulatorin rice, confers short-day promotion of flowering and controls FTÐlike gene expression independently of Hd1. Genes Development 18:926–936

Doyle JJ, Dickson EE (1987) Preservation of plant samples for DNA restriction endonuclease analysis. Taxon 36:715–722

Du B, Zhang WL, Liu BF, Hu J, Wei Z, Shi ZY et al (2009) Identification and characterization of Bph14, a gene conferring resistance to brown planthopper in rice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106(52):22163–22168

Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J (2005) Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol Ecol 14:2611–2620

Excoffier L, Lischer HE (2010) Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Molecular Ecology Resources 10:564–567

Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK (2003) Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics 164:1567–1587

Frei ER, Ghazoul J, Matter P, Heggli M, Pluess AR (2014) Plant population differentiation and climate change: responses of grassland species along an elevational gradient. Global Change Biol 20441–455

Frichot E, Schoville SD, Guillaume B, Francois O (2013) Testing for associations between loci and environmental gradients using latent factor mixed models. Mol Biol Evol 30:1687–1699

Gao LZ (2003) The conservation of Chinese rice biodiversity: genetic erosion, ethnobotany and prospects. Genetic Resourse Crop Evolution 50:17–32

Gao H, Zheng XM, Fei GL, Chen J, Jin MN, Ren YL et al (2013) Ehd4 Encodes a Novel and Oryza-Genus-Specific Regulator of Photoperiodic Flowering in Rice. PLoS Genet 9(2):e1003281

Goslee SC, Urban DL (2007) The ecodist package for dissimilarity-based analysis of ecological data. J Stat Softw 22:1–19

Hall TA (1999) Bioedit: a user–friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series 41:95–98

Harlan J (1992) Crop & Man, 2nd edn. Am Soc Agron, Madison

Hu PS, Zhai HQ, Wang JM (2002) New Characteristics of Rice Production and Quality Improvement in China. Review of China Agricultural Science Technology 4(4):33–39

Huang RL, Li Z, Mao C, Zhang H, Sun ZF, Li H (2020) Natural variation at OsCERK1 regulates arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in rice. New Phytol 225(4):1762–1776

Kanneganti V, Gupta AK (2008) Overexpression of OsiSAP8, a member of stress associated protein (SAP) gene family of rice confers tolerance to salt, drought and cold stress in transgenic tobacco and rice. Plant Mol Biol 66(5):445–462

Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K (2016) MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33:1870–1874

Li YB, Fan CC, Xing YZ, Jiang YH, Luo LJ, Sun L et al (2011) Natural variation in GS5 plays an important role in regulating grain size and yield in rice. Nat Genet 43:1266–1269

Liu KJ, Muse SV (2005) PowerMarker: an integrated analysis environment for genetic marker analysis. Bioinformatics 21:2128–2129

Mao HL, Sun SY, Yao JL, Wang CR, Yu SB, Xu CG et al (2010) Linking differential domain functions of the GS3 protein to natural variation of grain size in rice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107:19579–19584

Nei M (1987) Molecular Evolutionary Genetics. Columbia University Press, New York

Nielsen R, Williamson S, Kim Y, Hubisz MJ, Clark AG, Bustamante C (2005) Genomic scans for selective sweeps using SNP data. Genome Res 15(11):1566–1575

Ohsawa T, Ide Y (2008) Global patterns of genetic variation in plant species along vertical and horizontal gradients on mountains. Global Ecol Biogeogr 17:152–163

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P (2000) Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155:945–959

Pusadee T, Jamjod S, Chiang YC, Rerkasem B, Schaal BA (2009) Genetic structure and isolation by distance in a landrace of Thai rice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106:13880–13885

Qian WJ, Wu C, Fu YP, Hu GC, He ZQ, Liu WZ (2017) Novel rice mutants overexpressing the brassinosteroid catabolic gene CYP734A4. Plant Mol Biol 93(1):197–208

Rohlf F (2000) FNTSYS-PC numerical taxonomy and multivariate analysis system ver 2.11L. Applied Biostatistics, Newyork

Rozas J (2009) DNA sequence polymorphism analysis using DnaSP. Methods Mol Biol 537:337–350

Sexton JP, Hangartner SB, Hoffmann AA (2014) Genetic Isolation by Environment or Distance: Which Pattern of Gene Flow Is Most. Common? Evolution 68(1):1–15

Shang JJ, Tao Y, Chen XW, Zou Y, Lei CL, Wang J et al (2009) Identification of a New Rice Blast Resistance Gene, Pid3, by Genomewide Comparison of Paired Nucleotide-Binding SiteÐLeucine-Rich Repeat Genes and Their Pseudogene Alleles Between the Two Sequenced Rice Genomes. Genetics 182:1303–1311

Slatkin M (1995) A measure of population subdivision based on microsatellite allele frequencies. Genetics 139:457–462

Su CF, Wang YC, Hsieh TH, Lu CA, Tseng TH, Yu SM (2010) A Novel MYBS3-Dependent Pathway Confers Cold Tolerance in Rice. Plant Physiol 153(1):145–158

Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG (1997) The CLUSTALX windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res 25:4876–4882

Wang ET, Wang JJ, Zhu XD, Hao W, Wang LY, Li Q et al (2008) Control of rice grain-filling and yield by a gene with a potential signature of domestication. Nat Genet 40(11):1370–1374

Wang R, Jing W, Xiao LY, Jin YK, Shen LK, Zhang WH (2015) The Rice High-Affinity Potassium Transporter1;1 Is Involved in Salt Tolerance and Regulated by an MYB-Type Transcription Factor. Plant Physiol 168(3):1076–1090

Wang YX, Xiong GS, Hu J, Jiang L, Yu H, Jie, Xu et al (2015) Copy number variation at the GL7 locus contributes to grain size diversity in rice. Nat Genet 47(8):944–948

Wang D, Qin BX, Li X, Tang D, Zhang YE, Cheng ZK et al (2016) Nucleolar DEAD-Box RNA Helicase TOGR1 Regulates Thermotolerant Growth as a Pre-rRNA Chaperone in Rice. PLoS Genet 12(2):e1005844

Watterson GA (1975) On the number of segregating sites in genetical models without recombination. Theoretical population Biology 7:256–276

Xiong ZY, Zhang SJ, Wang YY, Ford-Lloyd BV, Tu M, Jin X et al (2010) Differentiation and distribution of indica and japonica rice varieties along the altitude gradients in Yunnan Province of China as revealed by InDel molecular markers. Genet Resour Crop Evol 57:891–902

Xiong ZY, Zhang SJ, Ford-Lloyd BV, Jin X, Wu Y, Yan HX et al (2011) Latitudinal Distribution and Diff erentiation of Rice Germplasm: Its Implications in Breeding. Crop Sci 51:1050–1058

Xu FR, Xinxiang A, Zhang FF, Zhang EL, Tang CF, Dong C et al (2014) On-farm conservation of 12 cereal crops among 15 ethnic groups inYunnan (PR China). Genet Resour Crop Evol 61:423–434

Xu FR, Dai LY, Han LZ (2016) Pictorial of Yunnan rice landraces in the early 21st century. Science Press, Beijing

Yamamoto E, Yonemaru JI, Yamamoto T, Yano M (2012) Rice OGRO: The overview of functionally characterized genes in rice on-line database. Rice 5:26

Yamanouchi U, Yano M, Lin HX, Ashikari M, Yamada K (2002) A rice spotted leaf gene, Spl7, encodes a heat stress transcription factor protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (11):7530–7535

Yang WB, Gao MJ, Yin X, Liu JY, Xu YH, Zeng LJ et al (2013) Control of Rice Embryo Development, Shoot Apical Meristem Maintenance, and Grain Yield by a Novel Cytochrome P450. Mol Plant 6(6):1945–1960

Yano M, Katayose Y, Ashikari M, Yamanouchi U, Monna L, Fuse T et al (2000) Hd1, a Major Photoperiod Sensitivity Quantitative Trait Locus in Rice, Is Closely Related to the Arabidopsis Flowering Time Gene CONSTANS. Plant Cell 12(12):2473–2484

Zeng YW, Wang XK, Yang ZY, Li ZC, Shen SQ, Zhang HL et al (2000a) Establishment and utilization of core collection bank of rice resources in Yunnan Province. J Plant Genet Resourc 1:12–16

Zeng YW, Xu FR, Shen SQ, Deng JY (2000b) Correlation of Indica japonica classification and morphological character of Yunnan nuda rice cultivars. Chinese J Rice Sci 14:115–118

Zeng YW, Wang JJ, Yang ZY, Shen SQ, Wu LH, Chen XY et al (2001) The diversity and sustainable devolopment of crop genetic resources in the Lancang River Valley. Genetic Resourse Crop Evolution 48:297–306

Zeng YW, Zhang HL, Li ZC, Shen SQ, Sun JL, Wang MX et al (2007) Evaluation of genetic diversity of rice landraces (Oryza sativa L.) in Yunnan, China. Breed Sci 57:91–99

Zhang HL, Sun JL, Wang MX, Liao DQ, Zeng YW, Shen SQ et al (2006) Genetic structure and phylogeography of rice landraces in Yunnan, China, revealed by SSR. Genome 50:72–83

Zhang J, Liu XQ, Li SY, Cheng ZK, Li CY (2014) The Rice Semi-Dwarf Mutant sd37, Caused by a Mutation in CYP96B4, Plays an Important Role in the Fine-Tuning of Plant Growth. PLoS ONE 9(2):e88068

Acknowledgements

We thank the Chinese National Germplasm Bank for providing the landrace rice seeds.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0100301, 2016YFD0100101), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31671664), the CAAS Science and Technology Innovation Program, the National Infrastructure for Crop Germplasm Resources (NICGR2018-01), and the Protective Program of Crop Germplasm of China (2018NWB036-01, 2018NWB036-12-2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.C., C.F.T., and H.F.L. performed statistical analyses and wrote the paper. L.Z.H. and D.C. conceived of and designed the experiments; D.C., J.M.L., and X.D.M. performed the experiments; C.F.T., X.X.A., L.Y.D., C.D., B.H., Y.Y.Y., and F.F.Z. contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools; L.Z.H. supervised the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Data availability statement

All data in this study have been uploaded as supplementary materials.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Geographic localities of rice landraces sampled in this study. The localities of rice landraces are indicated by solid circles. Detailed information of the materials is provided in Table S1. Figure S2. Schematic diagrams of ten nuclear loci and locations of the sequenced regions. Exons are shown as open boxes and exon numbers are labeled with capital roman numbers. Thin lines between open boxes indicate introns. Locations of primers for each fragment are shown above the diagrams. Figure S3. Correlation between the number of haplotypes and latitude (a), between θπ and latitude (b), between the number of alleles and latitude (c), and between gene diversity and altitude (d). Figure S4. The ΔK statistic for each given k. Figure S5. Model-based ancestries and their distribution in each location. (a) Model-based ancestry of each accession in P1 and P2; (b) distribution of model-based populations in each location. Figure S6. Correlation between the proportion of japonica rice and latitude (a) and between the proportion of indica rice and latitude (b). Figure S7. A map showing the sampled populations of rice landraces and the distribution of haplotypes. (a) and (b) show rice landraces in the japonica and indica group, respectively. Phylogenetic relationship of the haplotype based on the NJ analysis is indicated below the map. Pie charts show the proportions of the haplotypes within each county. Haplotypes are indicated by different colors. Figure S8. Functional category of cloned genes in selected regions. Figure S9. “a” to “d” depict the composite likelihood ration (CLR) value of subgroup “Jap-N” (purple), “Jap-S” (orange), “Ind-N” (dark blue), and “Ind-S” (blue), respectively, and “e” presents |z|-scores of the SNPs which were tested for associations between genetic variation and environmental gradients using latent factor mixed models (LFMM).

Additional file 2: Table S1.

List of samples included in the study, including their origin and group. Table S2. Summary of sequenced genes and primer sequences used in this study. Table S3. Summary of nucleotide polymorphisms and neutrality tests. Table S4. The genetic diversity of rice landraces based on 48 SSRs. Table S5. The genetic diversity of rice landraces in each population. Table S6. Putative selective-sweep regions in subgroup jap-N. Table S7. Putative selective-sweep regions in subgroup jap-S. Table S8. Putative selective-sweep regions in subgroup ind-N. Table S9. Putative selective-sweep regions in subgroup ind-S. Table S10. Cloned genes located on the selection-sweep regions. Table S11. QTLs that overlapped with selection-sweep regions. Table S12. SNPs with absolute value greater than 6 for the first three components of 24 environmental factors. Table S13. SNPs with the top 25 highest |z|-scores among those candidate genes with known functions. Table S14. Summary of SSR markers and primer sequences. Table S15. The detailed information of 24 environmental factors in each population. Table S16. Summary of agronomic traits for rice landraces in each population. The value before the slash shows the data collection from Yunnan, and the value after the slash shows the data collection from Hainan.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, D., Tang, C., Lu, H. et al. Genetic differentiation and restricted gene flow in rice landraces from Yunnan, China: effects of isolation-by-distance and isolation-by-environment. Rice 14, 54 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-021-00497-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-021-00497-6