Abstract

Background

The paper presents a numerical procedure for kinematic limit analysis of Mindlin plate governed by von Mises criterion.

Methods

The cell-based smoothed three-node Mindlin plate element (CS-MIN3) is combined with a second-order cone optimization programming (SOCP) to determine the upper bound limit load of the Mindlin plates. In the CS-MIN3, each triangular element will be divided into three sub-triangles, and in each sub-triangle, the gradient matrices of MIN3 is used to compute the strain rates. Then the gradient smoothing technique on whole the triangular element is used to smooth the strain rates on these three sub-triangles. The limit analysis problem of Mindlin plates is formulated by minimizing the dissipation power subjected to a set of constraints of boundary conditions and unitary external work. For Mindlin plates, the dissipation power is computed on both the middle plane and thickness of the plate. This minimization problem then can be transformed into a form suitable for the optimum solution using the SOCP.

Results and Conclusions

The numerical results of some benchmark problems show that the proposal procedure can provide the reliable upper bound collapse multipliers for both thick and thin plates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Limit analysis is a branch of plasticity analysis and plays an important role in determining the limit loads of a structure. The fundamental theorems of limit analysis ignore the evolutive elastoplastic computations but focus to determine the upper or lower bound loads which cause the plastic collapse of structures.

Using analytical methods and different yield criteria such as the maximum principal stress criterion, Tresca criterion, and von Mises criterion, many scholars derived the analytical solutions for the limit loads of plates. Some systematic and comprehensive summaries can be found in the monographs of Hodge [1], Save and Massonnet [2], Zyczkowski [3], Xu and Liu [4], Lubliner [5], Yu et al. [6], etc. Using numerical methods, some early works for the limit loads of plates can be mentioned such as those by Hodge and Belytschko [7] and Nguyen [8]. However, due to the lack of efficient optimization algorithms and the limit of the computing power, the numerical limit analysis of plates seems to be ignored for a certain times.

Recently, the interest of scientists in numerical limit analysis [9–15] has been resurged, principally thanks to the rapid development of efficient optimization algorithms and the continuous improvement in computer facilities. Current research is focusing on developing numerical limit analysis tools which are efficient and robust for the practice usage of engineers. In the numerical limit analysis, once the stress or displacement/velocity fields are approximated and the bound theorems are applied, the limit analysis becomes a problem of optimization involving either linear programing (LP) or nonlinear programming (NLP) which can be solved respectively by the available LP or NLP algorithms [16–23].

For the LP algorithms, some significant contributions have been published such as the active set LP algorithm by Sloan [16], the bespoke interior-point algorithm for LP by Andersen and Christiansen [17], and the commercial LP code XA by Pastor et al. [18]. For the NLP algorithms, some recently important contributions can be mentioned such as the algorithm based on feasible directions by Zouain et al. [10] or by Lyamin and Sloan [19], the algorithm based on the interior-point method by Andersen et al. [20] or by Krabbenhoft and Damkilde [21], and the general-purpose NLP codes CONOPT and MINOS by Tin-Loi and Ngo [22]. Recently, one of the most efficient NLP algorithms based on the primal-dual interior-point method was proposed by Andersen et al. [23]. The algorithm can be applied to von Mises-type yield functions and can handle problems with any nonlinear yield functions. The algorithm is implemented in second-order cone programming (SOCP) [24] of the commercial software MOSEK [25] and has been applied for the limit loads of some limit analysis problems [26, 27].

Using such LP and NLP algorithms for the numerical limit analyses of plate structures, many significant researches have been published. For the Kirchhoff plates, we can list the works by Christiansen and Larsen [28], Turco and Caracciolo [29], Corradi and Vena [30], Corradi and Panzeri [31], Tran et al. [32], Le et al. [33–35], and Zhou et al. [36]. For the Mindlin plates, we can list the works by Capsoni and Corradi [37] and Capsoni and Vicente da Silva [38]. In comparison, it is seen that many studies in the literature are concerned with the limit analysis of Kirchhoff plates, while the literature related to those of Mindlin plates is somehow still limited. This paper hence aims to further contribute a numerical limit analysis of Mindlin plates by using a Mindlin plate element proposed recently together with the SOCP.

In the other front of the development of numerical methods, Liu and Nguyen Thoi [39] have integrated the strain smoothing technique [40] into the finite element method (FEM) to create a series of smoothed FEMs (S-FEMs) such as cell/element-based smoothed FEM (CS-FEM) [41–43], node-based smoothed FEM (NS-FEM) [44–46], edge-based smoothed FEM (ES-FEM) [47, 48], face-based smoothed FEM (FS-FEM) [49], and a group of alpha-FEM [50–53]. Each of these smoothed FEMs has different properties and has been used to produce desired solutions for a wide class of benchmark and practical mechanics problems. Several theoretical aspects of the S-FEM models have been provided in [54, 55]. The S-FEM models have also been further investigated and applied to various problems such as plates and shells [56–68], piezoelectricity [69, 70], fracture mechanics [71], visco-elastoplasticity [72–74], limit and shakedown analysis for solids [75–77], and some other applications [78, 79].

Among these S-FEM models, the CS-FEM [39, 41] shows some interesting properties in solid mechanics problems. Extending the idea of the CS-FEM to plate structures, Nguyen-Thoi et al. [80] have recently formulated a cell-based smoothed three-node Mindlin plate element (CS-MIN3) for static and free vibration analyses of isotropic Mindlin plates by incorporating the CS-FEM with the original MIN3 element [81]. In the CS-MIN3, each triangular element will be divided into three sub-triangles, and in each sub-triangle, the MIN3 is used to compute the strains. Then, the strain smoothing technique on whole the triangular element is used to smooth the strains on these three sub-triangles. The numerical results showed that the CS-MIN3 is free of shear locking and achieves high accuracy compared to the exact solutions and other existing elements in the literature.

In this paper, the CS-MIN3 is further extended to the kinematic limit analysis of Mindlin plates governed by the von Mises criterion. The CS-MIN3 is combined with a SOCP to determine the limit load of the plates. The limit analysis problem of Mindlin plates is formulated by minimizing the dissipation power subjected to a set of constraints of boundary conditions and unitary external work. For Mindlin plates, the dissipation power is computed on both the middle plane and the thickness of the plate. This minimization problem can then be transformed into a form suitable for the optimum solution using the SOCP. The accuracy and reliability of the proposed method are verified by comparing its numerical solutions with those of other available numerical results.

Methods

Limit analysis of Mindlin plates-kinematic formulation

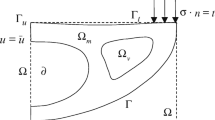

We now consider a rigid-perfectly plastic plate identified by its middle plane Ω, the thickness h, and the boundary Γ = Γ

u

∪ Γ

t

where Γ

t

is the boundary subjected to a surface traction  and Γ

u

is the constrained boundary. Let w be the transverse displacement (deflection) and

and Γ

u

is the constrained boundary. Let w be the transverse displacement (deflection) and  be the vector of rotations, in which β

x

and β

y

are the rotations of the middle plane around the y-axis and x-axis, respectively, with the positive directions defined as shown in Figure 1.

be the vector of rotations, in which β

x

and β

y

are the rotations of the middle plane around the y-axis and x-axis, respectively, with the positive directions defined as shown in Figure 1.

The unknown vector of three independent field variables at any point in the problem domain of the Mindlin plates can be written as

The curvature of the deflected plate κ and the shear strains γ are defined, respectively, as

where  and L

d

is a differential operator matrix defined by

and L

d

is a differential operator matrix defined by

Because the material in the limit analysis is assumed to be rigid-perfectly plastic, the bending stress σ and transverse shear τ are confined within the convex domain Φ(σ, τ) ≤ 0, where Φ(σ, τ) is the yield function. If von Mises's criterion is adopted, we have

where σ 0 is the yield stress and

Deformations cannot occur as long as Φ(σ, τ) < 0, while plastic flow may develop when Φ(σ, τ) = 0. In this case, strain rates  and

and  obey the normality flow rule as

obey the normality flow rule as

Equation 6 might impose restrictions on strain rates, by confining them within a convex domain  , the sub-space spanned by the outward normals to the yield surface.

, the sub-space spanned by the outward normals to the yield surface.

Let  represent the admissible stresses contained within the convex yield surface and

represent the admissible stresses contained within the convex yield surface and  represent the stress point on the limit surface associated to any given strain rate

represent the stress point on the limit surface associated to any given strain rate  through the plasticity condition, then the plastic dissipation power

through the plasticity condition, then the plastic dissipation power  (per unit volume) is defined by Hill's maximum principle as

(per unit volume) is defined by Hill's maximum principle as

The plastic dissipation power is a uniquely defined function of strain rates, and its explicit expression is available for a number of yield criteria [5]. If von Mises's criterion is adopted, one has [37]

with

Using the relation ϵ = z κ between the membrane strain ϵ with the curvature κ, Equation 8 can be rewritten as

The internal dissipation power for the two-dimensional plate domain Ω with the thickness h is now expressed as

The limit analysis of the Mindlin plate considers a rigid-perfectly plastic plate subjected to body forces  on its middle plane Ω and to surface tractions

on its middle plane Ω and to surface tractions  on the boundary Γ

t

. The constrained boundary Γ

u

is fixed. Loads now are defined as basic values b and

on the boundary Γ

t

. The constrained boundary Γ

u

is fixed. Loads now are defined as basic values b and  , affected by a load multiplier λ. Then, the kinematic theorem of limit analysis states that the limit value λ

+ (collapse multiplier) of λ is the optimal value of the minimization problem [37]

, affected by a load multiplier λ. Then, the kinematic theorem of limit analysis states that the limit value λ

+ (collapse multiplier) of λ is the optimal value of the minimization problem [37]

subject to

Equations 13(a) and 13(b) express the compatibility of the constrained boundary and the strain rate with a velocity field  , respectively, and Equation 13(c) denotes the power of basic loads, which is normalized to unity.

, respectively, and Equation 13(c) denotes the power of basic loads, which is normalized to unity.

Note that in Equation 11, the dissipation power  is a positively homogeneous function of degree 1 in the strain rates and not differentiable at strain rate zero. Equations 13(a) to 13(c) hence bring the computation of the collapse multiplier to the search of the minimum of a convex but not everywhere differentiable functional. The functional minimized in Equation 12 is only differentiable in the region Ω

p

where plastic flow develops, but not so in the remaining portion Ω

r

of the plate, which keeps rigid in the mechanism, and hence, the minimum does not correspond to a stationary point.

is a positively homogeneous function of degree 1 in the strain rates and not differentiable at strain rate zero. Equations 13(a) to 13(c) hence bring the computation of the collapse multiplier to the search of the minimum of a convex but not everywhere differentiable functional. The functional minimized in Equation 12 is only differentiable in the region Ω

p

where plastic flow develops, but not so in the remaining portion Ω

r

of the plate, which keeps rigid in the mechanism, and hence, the minimum does not correspond to a stationary point.

Brief on kinematic formulation of CS-MIN3 for Mindlin plates

Kinematic formulation of the MIN3 for Mindlin plates

In the original MIN3 [81], the rotations are assumed to be linear through the rotational degrees of freedom (DOFs) at three nodes of the elements, and the deflection is initially assumed to be quadratic through the deflection DOFs at six nodes (three nodes of the elements and three mid-edge points). Then, by enforcing continuous shear constraints at every element edge, the deflection DOFs at three mid-edge points can be removed and the deflection is now approximated only by vertex DOFs at three nodes of the elements. The MIN3 element can hence overcome shear locking and produces convergent solutions. In this paper, we just brief on the kinematic formulation of the MIN3 which is necessary for the kinematic formulation of the CS-MIN3.

Using a mesh of three-node triangular elements, the approximation of displacement flow  for an element Ω

e

shown in Figure 2 can be written as

for an element Ω

e

shown in Figure 2 can be written as

where  , I = 1, 2, 3, is the flow vector of the nodal degrees of freedom of

, I = 1, 2, 3, is the flow vector of the nodal degrees of freedom of  associated to node I and N

I

(x), I = 1, 2, 3, are linear shape functions at node I.

associated to node I and N

I

(x), I = 1, 2, 3, are linear shape functions at node I.

The curvature rates of the deflection flow in an element are then defined by

where  is the vector of nodal displacement flow of the element and B contains the constants which are derived from the derivatives of the shape functions as

is the vector of nodal displacement flow of the element and B contains the constants which are derived from the derivatives of the shape functions as

in which N ,x and N ,y are the matrices of derivatives of the shape functions in the x-direction and y-direction, respectively.

The shear strain rates of the deflection flow in an element are then defined by

where

in which L

,x

, L

,y

, H

,x

, and H

,y

are the matrices of derivatives of the shape functions in the x-direction and y-direction, respectively, and  and

and  are the vectors of shape functions, with L

I

and H

I

, I = 1, 2, 3, given by

are the vectors of shape functions, with L

I

and H

I

, I = 1, 2, 3, given by

in which a i and b i (i = 1 ÷ 3) are the geometric distances as shown in Figure 2.

Kinematic formulation of CS-MIN3

In the CS-MIN3 [80], the domain discretization is the same as that of the MIN3 using N n nodes and N e triangular elements. However, in the formulation of the CS-MIN3, each triangular element Ω e is further divided into three sub-triangles Δ1, Δ2, and Δ3 by connecting the central point O of the element to three field nodes as shown in Figure 3.

In the CS-MIN3, we assume that the vector of displacement flow  at the central point O is the simple average of three vectors of displacement flow

at the central point O is the simple average of three vectors of displacement flow  ,

,  , and

, and  of three field nodes as

of three field nodes as

On the first sub-triangle Δ1 (triangle O-1-2), the linear approximation  is constructed by

is constructed by

where  is the vector of displacement flow of nodal degrees of freedom of the sub-triangle Δ1 and

is the vector of displacement flow of nodal degrees of freedom of the sub-triangle Δ1 and  is the vector containing the linear shape functions at nodes O, 1, 2 of the sub-triangle Δ1.

is the vector containing the linear shape functions at nodes O, 1, 2 of the sub-triangle Δ1.

The curvature rates of the deflection flow  and the altered shear strain rates

and the altered shear strain rates  in the sub-triangle Δ1 are then obtained by

in the sub-triangle Δ1 are then obtained by

where  and

and  are respectively computed similarly as the matrices B and S of the MIN3 in Equations 16 and 18 but with two following changes: (1) the coordinates of three-node

are respectively computed similarly as the matrices B and S of the MIN3 in Equations 16 and 18 but with two following changes: (1) the coordinates of three-node  , i = 1, 2, 3, are replaced by x

O

, x

1, and x

2, respectively, and (2) the area A

e

is replaced by the area

, i = 1, 2, 3, are replaced by x

O

, x

1, and x

2, respectively, and (2) the area A

e

is replaced by the area  of sub-triangle Δ1.

of sub-triangle Δ1.

Substituting  in Equation 21 into Equations 23 and 24, and then rearranging, we obtain

in Equation 21 into Equations 23 and 24, and then rearranging, we obtain

Similarly, by using cyclic permutation, we easily obtain the curvature rates of the deflection flow  , the shear strains

, the shear strains  , and matrices

, and matrices  and

and  , j = 2, 3, for the second sub-triangle Δ

2 (triangle O-2-3) and third sub-triangle Δ

3 (triangle O-3-1), respectively.

, j = 2, 3, for the second sub-triangle Δ

2 (triangle O-2-3) and third sub-triangle Δ

3 (triangle O-3-1), respectively.

Now, by applying the cell-based strain smoothing operation in the CS-FEM [39, 41], the bending and shear strain rates  and

and  , j = 1, 2, 3, are used to create the smoothed bending and smoothed shear strain rates

, j = 1, 2, 3, are used to create the smoothed bending and smoothed shear strain rates  and

and  , respectively, on the triangular element Ω

e

, such as

, respectively, on the triangular element Ω

e

, such as

where Φ

e

(x) is a given smoothing function that satisfies the unity property  Using the following constant smoothing function

Using the following constant smoothing function

where A

e

is the area of the triangular element, the smoothed bending strain rate  and the smoothed shear strain rate

and the smoothed shear strain rate  in Equations 27 and 28 become

in Equations 27 and 28 become

Substituting  and

and  , j = 1, 2, 3, into Equation 30, the smoothed bending strain rate

, j = 1, 2, 3, into Equation 30, the smoothed bending strain rate  and the smoothed shear strain rate

and the smoothed shear strain rate  are expressed by

are expressed by

where  and

and  are the smoothed bending and shear strain gradient matrices given by

are the smoothed bending and shear strain gradient matrices given by

Discretization of kinematic formulation by CS-MIN3

In Equation 11, when c s becomes small at the thin plate limit, the last term is very nearly singular and numerical integration is preferable. To avoid inaccuracies associated with the point z = 0, twice the integral over half thickness is considered, and Equation 11 can be rewritten as [37]

where ζ = 4z/h − 1 and ζ g and W g are the usual Gauss integration point coordinates and weights, respectively; n G is the number of Gauss integration points; m 0 = σ 0 h 2/4 is the plastic moment of resistance per unit width of the plate of thickness h.

By discretizing the domain Ω into n

e

triangular plate elements such that  and Ω

i

∩ Ω

j

= ∅, i ≠ j, and using the kinematic formulation of the CS-MIN3 as presented in the ‘Brief on kinematic formulation of CS-MIN3 for Mindlin plates’ section, the plastic dissipation in Equation 33 is expressed as

and Ω

i

∩ Ω

j

= ∅, i ≠ j, and using the kinematic formulation of the CS-MIN3 as presented in the ‘Brief on kinematic formulation of CS-MIN3 for Mindlin plates’ section, the plastic dissipation in Equation 33 is expressed as

where  and

and  in which

in which  and

and  are computed at the Gauss points by Equation 31.

are computed at the Gauss points by Equation 31.

Combining Equations 9 and 31,  and

and  are now expressed explicitly as

are now expressed explicitly as

The plastic dissipation in Equation 34 is hence expressed as

where

Equation 37 can be rewritten in the matrix form as

where

and

Note that using Equations 31 and 32, the vector y

i

in Equation 40 can be rewritten in the form of the discrete element displacement flow vector

where

and  and

and  are the components extracted, respectively, from the matrices

are the components extracted, respectively, from the matrices  and

and  in Equation 32.

in Equation 32.

Similarly, the external energy  in Equation 13(c) and the boundary condition of displacement flow Equation 13(a) can be combined and rewritten in the matrix form of the discrete system displacement flow vector

in Equation 13(c) and the boundary condition of displacement flow Equation 13(a) can be combined and rewritten in the matrix form of the discrete system displacement flow vector  as [33]

as [33]

Combining Equations 36, 38, 42, and 44, the minimization problem (12) associated with the CS-MIN3 now becomes the problem of finding the optimal value λ + such that

subjected to the constraints

The minimization problem (45) is a convex programming problem in which the objective function is a positively homogeneous function of degree 1 in the variables z i (or in the strain rates) and is not differentiable at any points in the rigid domain which do not undergo plastic flow (||z i || = 0). The minimization problem (45) is also categorized into the group of the problems of minimizing a sum of Euclidean norms which has a natural dual maximization formulation [23].

For solving this group of problem, one of the well-known approaches used is to replace the terms ||z

i

|| in the objective by the differentiable quantity  , where μ is a fixed positive number. This method is robust but converges slowly as μ → 0 because some of the norms in the objective function have zero as their optimal value [23].

, where μ is a fixed positive number. This method is robust but converges slowly as μ → 0 because some of the norms in the objective function have zero as their optimal value [23].

Recently, Andersen et al. [24] recently employed the aspect of duality of the problem to propose a primal-dual interior-point method for solving a homogeneous self-dual model of conic quadratic programming. In this method, the terms ||z

i

|| are also replaced by  , but the quantity μ is treated as an extra variable, whose value is determined by duality estimates. Using this method, the minimization problem (45) is now solved rapidly and accurately even if there are a large number of variables and many norms ||z

i

|| are zero at a solution point. Also, the primal-dual interior-point method is recently integrated in an available general software (e.g., MOSEK [25]) which specializes second-order cone programming (SOCP) problems [24]. The limit analysis problem can hence be solved efficiently using such software.

, but the quantity μ is treated as an extra variable, whose value is determined by duality estimates. Using this method, the minimization problem (45) is now solved rapidly and accurately even if there are a large number of variables and many norms ||z

i

|| are zero at a solution point. Also, the primal-dual interior-point method is recently integrated in an available general software (e.g., MOSEK [25]) which specializes second-order cone programming (SOCP) problems [24]. The limit analysis problem can hence be solved efficiently using such software.

The minimization problem (45) is hence rewritten in the form of a standard SOCP problem by introducing auxiliary variables t i , i = 1, 2, …, n e × n G , such that

subjected to the constraints

where Equation 48(c) represents quadratic cone constraints. With the form of standard SOCP problem, the minimization problem (47) for finding the collapse multipliers of the Mindlin plates can now be solved efficiently by using the software MOSEK.

Note that the formulation of the minimization problem of the plastic dissipation power in the form of standard SOCP problem was also presented in [33, 35]; however, the form of standard SOCP problem in these references is only for Kirchhoff plates.

Also, note that in the kinematic limit analysis of plates, the ability to obtain the strict upper bound depends not only on the efficient solution of the arising optimization problem but also on the effectiveness of the elements employed. It is required that the flow rule needs hold throughout each element. For the C1-continuous elements, this requirement can be satisfied naturally. However, for the C0-continuous elements, it can be violated due to the appearance of plastic hinge lines on boundaries of elements. In order to overcome this violation, the internal work dissipated in resulting hinge lines on boundaries of elements should be taken into account as done by Hodge and Belytschko [7] and Makrodimopoulos and Martin [82]. In this paper, the CS-MIN3 uses only three-node triangular plate elements and hence belongs to the C0-continuous elements. However, for the sake of simplicity of using the CS-MIN3 in the limit analysis of plates, we can ignore considering the internal work dissipated in resulting hinge lines on boundaries of elements. It is therefore no longer possible to guarantee that the solution obtained from the minimization problem (47) is a strict upper bound on the collapse multiplier. However, using the smoothed strain rates which are constant over elements, the flow rule only needs to be enforced at any point in each element, and it is guaranteed to be satisfied almost everywhere in the problem domain. Therefore, the computed collapse load obtained using the proposed method can still be reasonably considered as an upper bound on the actual value.

Results and discussion

The number performance of the proposed limit analysis will now be tested by examining a number of benchmark uniformly loaded or point-loaded plate problems for which numerical solutions have been published in the literature. For all the examples considered, the following were assumed: yield stress σ p = 250 MPa and yield moment M p = σ p t 2/4.

Square plates

We now consider a square plate subjected to a uniform out-of-plane pressure loading (with basic load p = M p /L 2) with two different boundary conditions: (1) clamped supports on all edges as shown in Figure 4a and (2) simply supported supports on all edges as shown in Figure 4b. For this problem, the full plate is considered and the upper bound reference solution using quadrilateral elements with 867 degrees of freedom (DOFs) can be found in [37, 38]. Figure 4c illustrates four forms of discretization of the plate using triangular elements.

In this example, firstly, the thickness of the plate is chosen such that the ratio L/t = 10 and the plate is discretized by the mesh 12 × 12 with 507 DOFs. We first consider the effect of the collapse multipliers when the number of Gauss points along the half of the thickness of the plate is changed from 1 point to 7 points. Figures 5 and 6 show the convergence of the collapse multipliers versus the different numbers of Gauss points for both cases of boundary conditions by MIN3 and CS-MIN3. The results show that both solutions of the CS-MIN3 and MIN3 converge to the upper bound reference solution [38] when the number of Gauss points increases, but those of the CS-MIN3 are more accurate than those of the MIN3. This hence implies that the CS-MIN3 can provide the reliable upper bound collapse multipliers for the Mindlin plates when a suitable number of Gauss points is used along the half of the thickness of the plate. In these analyses, it is seen that the usage of 6 Gauss points is the most suitable for both cases of boundary conditions and hence will be recommended for default employing in the CS-MIN3 (and also in the MIN3) for all numerical examples in this paper.

Next, the convergence of the collapse multipliers versus various degrees of freedom of the system is considered. The numbers of degrees of freedom of the system are now changed from 75 (corresponding to the mesh 4 × 4) to 507 (corresponding to the mesh 12 × 12). The results for both cases of boundary conditions by the CS-MIN3 and MIN3 are listed in Table 1 and plotted in Figures 7 and 8, respectively. The results show that both solutions of the CS-MIN3 and MIN3 converge to the reference solutions when the number of degrees of freedom increases. In addition, Figures 9 and 10 show the patterns of displacement and plastic energy dissipation at collapse for both cases of boundary conditions by using the CS-MIN3. It can be observed that the forms of the yield lines are clearly identified reasonably from these dissipation patterns. These results hence imply that the CS-MIN3 can provide the reliable upper bound collapse multipliers for the Mindlin plates when a suitable number of degrees of freedom is used. Note that in the above analyses, the results of the CS-MIN3 are more accurate than those of the MIN3, especially in the coarse meshes. This hence implies that the cell-based strain smoothing technique in the CS-MIN3 is very necessary to improve the accuracy of the MIN3 in the limit analysis of Mindlin plates.

Last, the analysis for the solutions of the thin plate by the CS-MIN3 and MIN3 is performed for the clamped square plate by changing the slenderness ratios (L/t) from 5 to 6,250 with the mesh 12 × 12. Convergence of the collapse multipliers of the clamped square plate versus various slenderness ratios (L/t) by the CS-MIN3 and MIN3 is plotted in Figure 11. The Kirchhoff reference results can be found in [33, 37]. As expected, the solutions of the CS-MIN3 converge to the reference Kirchhoff solution [33] when the slenderness ratio is increased to the limit of the thin plate. This hence shows that the CS-MIN3 is free of shear locking in the limit analysis of thin plates. Also, note that the convergence of solutions of MIN3 is much higher than the expected value when the slenderness ratio is increased to the limit of the thin plate. This hence implies that the cell-based strain smoothing technique in the CS-MIN3 is very necessary to improve the instable behavior of the MIN3 in the limit analysis of thin plates.

Rectangular plate

We now consider a rectangular plate with simply supported supports on all edges and subjected to a uniform out-of-plane pressure loading (with basic load p = M p /(L. H)) as shown in Figure 12a. For this problem, the full plate is considered and the upper bound reference solution using a meshfree method with 1,350 DOFs can be found in [33]. Figure 12b illustrates four forms of discretization using uniform meshes of triangular elements.

The convergence of collapse multipliers with respect to the number of degrees of freedom is considered by choosing the thickness of the plate t = 0.01 m, the width L = 2 m, and the ratio L/H = 2. The results by the CS-MIN3 and MIN3 are listed in Table 2 and plotted in Figure 13. In addition, Figure 14 shows the patterns of displacement and plastic energy dissipation at collapse by the CS-MIN3. It is seen that the obtained comments from the square plates related to the convergence and accuracy of the CS-MIN3 in the limit analysis of Mindlin plates are confirmed for the rectangular plates.

Rhombic plate

We now consider a clamped rhombic plate with the radius R = 0.5 m and the thickness t = 0.02 m subjected to a uniform out-of-plane pressure loading (with basic load p = M p /R 2) as shown in Figure 15a. For this problem, the full plate is considered and the upper bound reference solutions using quadrilateral elements with 867 degrees of freedom can be found in [38]. Figure 15b illustrates four forms of discretization using uniform meshes of triangular elements.

The convergence of collapse multipliers of the clamped rhombic plate with respect to the number of degrees of freedom and various skewness angles α is listed in Table 3 and plotted in Figure 16 for two cases of α = 30° and α = 60°. In addition, the patterns of the plastic energy dissipation at collapse by the CS-MIN3 for two cases of α = 30° and α = 60° are shown in Figure 17. Again, it is seen that the comments obtained from two previous examples related to the convergence and accuracy of the CS-MIN3 in the limit analysis of Mindlin plates are confirmed for the rhombic plates.

In addition, an analysis of collapse multipliers of the clamped rhombic plate with respect to various skewness angles α by the CS-MIN3 and MIN3 is illustrated in Figure 18. It is observed that the results of the CS-MIN3 are very close to those of reference solutions, especially for small skewness angles α. These results hence imply that the CS-MIN3 can provide the reliable solutions in the limit analysis of skew Mindlin plates.

Circular plate

We now consider a clamped circular plate (radius R = 1m and thickness of plate t = 0.01 m) subjected to a uniform out-of-plane pressure loading (with basic load p = M p /R 2). Due to its symmetry, only the upper right quadrant of the plate is discretized by 294 triangular elements (507 DOFs) as shown in Figure 19. The upper bound reference solutions using quadrilateral elements with 1,041 DOFs can be found in [38].

The convergence of collapse multipliers with respect to the number of degrees of freedom is plotted in Figure 20, and the patterns of displacement and the plastic energy dissipation at collapse by the CS-MIN3 are shown Figure 21. Again, it is seen that the comments obtained from three previous examples related to the convergence and accuracy of the CS-MIN3 in the limit analysis of Mindlin plates are confirmed for the circular plates.

Next, due to the availability of the thin plate reference solutions [38] (collapse multiplier = 13.231), we hence perform a convergent analysis of the collapse multipliers with respect to various slenderness ratios (2R/t) by the CS-MIN3 and MIN3. The results are listed in Table 4 and plotted in Figure 22. As expected, the solutions of the CS-MIN3 again converge to the reference solutions when the slenderness ratio is increased to the limit of the thin plate. This hence confirms again that the CS-MIN3 is free of shear locking in the limit analysis of thin plates. Also, note that the convergence of solutions of MIN3 is much higher than the expected value when the slenderness ratio is increased to the limit of the thin plate. This hence confirms again that the cell-based strain smoothing technique in the CS-MIN3 is very necessary to improve the instable behavior of the MIN3 in the limit analysis of thin plates.

Equilateral triangle plate

We now consider an equilateral triangle plate as shown in Figure 23a with the assigned radius R = 1m and thickness t = 0.04m. The plate is clamped on the boundary and subjected to a uniform out-of-plane pressure loading (with basic load p = M p /R 2). For this problem, the full plate is considered and the upper bound reference solutions can be found in [38]. Figure 23b illustrates a discretization using uniform meshes of triangular elements.

The convergence of collapse multipliers with respect to the number of degrees is listed in Table 5 and plotted in Figure 24, and the patterns of displacement and the plastic energy dissipation at collapse by the CS-MIN3 are shown in Figure 25. Again, it is seen that the obtained comments from four previous examples related to the convergence and accuracy of the CS-MIN3 in the limit analysis of Mindlin plates are confirmed for the equilateral triangle plate.

Conclusions

The paper presents a numerical procedure for the kinematic limit analysis of thick plates governed by the von Mises criterion. The cell-based smoothed three-node Mindlin plate element (CS-MIN3) is combined with a second-order cone optimization programming (SOCP) to determine the upper bound limit load of the Mindlin plates. In the CS-MIN3, each triangular element is divided into three sub-triangles, and in each sub-triangle, the gradient matrices of MIN3 are used to compute the strain rates. Then, the gradient smoothing technique on whole the triangular element is used to smooth the strain rates on these three sub-triangles. The limit analysis problem of Mindlin plates is formulated by minimizing the dissipation power subjected to a set of constraints of boundary conditions and unitary external work. For Mindlin plates, the dissipation power is computed on both the middle plane and the thickness of the plate. This minimization problem can then be transformed into a form suitable for optimum solution using the SOCP. Through the formulation and numerical examples, some concluding remarks can be drawn as follows:

-

1.

The CS-MIN3 uses only three-node triangular elements that are much easily generated automatically for arbitrary complex geometrical domains.

-

2.

The CS-MIN3 can provide reliable upper bound collapse multipliers for both thick and thin plates.

-

3.

The solutions of the CS-MIN3 converge from the upper bound, and the CS-MIN3 is free of shear locking in the limit analysis of thin plates.

-

4.

Compared to the MIN3, the CS-MIN3 is more accurate in the limit analysis of thick plates and more stable in the limit analysis of thin plates.

-

5.

The forms of the yield lines by the CS-MIN3 are identified reasonably from the dissipation patterns.

In addition, the extension of the present CS-MIN3 for the limit analysis of flat shells using triangular elements is very promising.

References

Hodge PG: Limit analysis of rotationally symmetric plates and shells. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall; 1963.

Save MA, Massonnet CE: Plastic analysis and design of plates, shells and disks. North-Holland, Amsterdam; 1972.

Zyczkowski M: Combined loadings in the theory of plasticity. Wasarwa, Poland: Polish Scientific, PWN and Nijhoff; 1981.

Xu BY, Liu XS: Plastic limit analysis of structures. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press; 1985.

Lubliner J: Plasticity theory. New York: Macmillan; 1990.

Yu MH, Ma GW, Li JC: Structural plasticity limit, shakedown and dynamic plastic analyses of structures. New York: Springer; 2009.

PhGJr H, Belytschko T: Numerical methods for the limit analysis of plates. ASME J Appl Mech 1968, 35:796–802.

Nguyen HD: Direct limit analysis via rigid-plastic finite elements. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 1976, 8:81–116.

Christiansen E, Kortanek KO: Computation of the collapse state in limit analysis using the LP affine scaling algorithm. J Comput Appl Math 1991, 34:47–63.

Zouain N, Herskovits J, Borges LA, Feijóo RA: An iterative algorithm for limit analysis with nonlinear yield functions. Int J Solids Struct 1993, 30:1397–1417.

Liu YH, Zen ZZ, Xu BY: A numerical method for plastic limit analysis of 3-D structures. Int J Solids Struct 1995, 32:1645–1658.

Capsoni A, Corradi L: A finite element formulation of the rigid-plastic limit analysis problem. Int J Numer Methods Eng 1997, 40:2063–2086.

Christiansen E, Andersen KD: Computation of collapse states with von Mises type yield condition. Int J Numer Methods Eng 1999, 46:1185–1202.

Corradi L, Panzeri N: A triangular finite element for sequential limit analysis of shells. Adv Eng Software 2004, 35:633–643.

Le VC, Nguyen-Xuan H, Askes H, Bordas S, Rabczuk T, Nguyen-Vinh H: A cell-based smoothed finite element method for kinematic limit analysis. Int J Numer Methods Eng 2010, 83:1651–1674.

Sloan SW: A steepest edge active set algorithm for solving sparse linear programming problems. Int J Numer Methods Eng 1988, 26:2671–2685.

Andersen KD, Christiansen E: Limit analysis with the dual affine scaling algorithm. J Comput Appl Math 1995, 59:233–243.

Pastor J, Thai TH, Francescato P: Interior point optimization and limit analysis: an application. Commun Numer Methods Eng 2003, 19:779–785.

Lyamin AV, Sloan SW: Upper bound analysis using linear finite elements and non-linear programming. Int J Numer Anal Methods Geomech 2002, 26:181–216.

Andersen KD, Christiansen E, Overton ML: Computing limit loads by minimizing a sum of norms. SIAM J Sci Comput 1998, 19:1046–1062.

Krabbenhoft K, Damkilde L: A general non-linear optimization algorithm for lower bound limit analysis. Int J Numer Methods Eng 2003, 56:165–184.

Tin-Loi F, Ngo NS: Performance of the p -version finite element method for limit analysis. Int J Mech Sci 2003, 45:1149–1166.

Andersen KD, Christiansen E, Overton ML: An efficient primal-dual interior-point method for minimizing a sum of Euclidean norms. SIAM J Sci Comput 2001, 22:243–262.

Andersen ED, Roos C, Terlaky T: On implementing a primal-dual interior-point method for conic quadratic programming. Math Program 2003, 95:249–277.

Mosek: The MOSEK optimization toolbox for MATLAB manual. Mosek ApS 2008. http://www.mosek.com

Krabbenhoft K, Lyamin AV, Sloan SW: Formulation and solution of some plasticity problems as conic programs. Int J Solids Struct 2006, 44:1533–1549.

Makrodimopoulos A, Martin CM: Upper bound limit analysis using simplex strain elements and second-order cone programming. Int J Num Anal Methods Geomech 2007, 31:825–865.

Christiansen E, Larsen S: Computations in limit analysis for plastic plates. Int J Numer Methods Eng 1983, 19:169–184.

Turco E, Caracciolo P: Elasto-plastic analysis of Kirchhoff plates by high simplicity finite elements. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 2000, 10:691–706.

Corradi L, Vena P: Limit analysis of orthotropic plates. Int J Plast 2003, 19:1543–1566.

Corradi L, Panzeri N: Post-collapse analysis of plates and shells based on a rigid-plastic version of the TRIC element. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 2003, 192:3747–3775.

Tran TN, Kreissig R, Staat M: Probabilistic limit and shakedown analysis of thin plates and shells. Struct Saf 2009, 31:1–18.

Le VC, Gilbert M, Askes H: Limit analysis of plates using the EFG method and second-order cone programming. Int J Numer Methods Eng 2009, 78:1532–1552.

Le VC, Askes H, Gilbert M: Adaptive element-free Galerkin method applied to the limit analysis of plates. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 2010, 199:2487–2496.

Le VC, Nguyen-Xuan H, Nguyen-Dang H: Upper and lower bound limit analysis of plates using FEM and second-order cone programming. Comput Struct 2010, 88:65–73.

Zhou S, Liu Y, Chen S: Upper bound limit analysis of plates utilizing the C1 natural element method. Comput Mech 2010. doi:10.1007/s00466–012–0688–8

Capsoni A, Corradi L: Limit analysis of plates - a finite element formulation. Struct Eng Mech 1999, 8:325–341.

Capsoni A, Vicente da Silva M: A finite element formulation of Mindlin plates for limit analysis. Int J Num Methods Biomed Eng 2011, 27:143–156.

Liu GR, Nguyen Thoi T: Smoothed finite element methods. New York: CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group; 2010.

Chen JS, Wu CT, Yoon S, You Y: A stabilized conforming nodal integration for Galerkin mesh-free methods. Int J Numer Methods Eng 2001, 50:435–466.

Liu GR, Dai KY, Trung NT: A smoothed finite element for mechanics problems. Comp Mech 2007, 39:859–877.

Trung NT, Liu GR, Dai KY, Lam KY: Selective smoothed finite element method. Tsinghua Sci Technol 2007,12(5):497–508.

Liu GR, Trung NT, Nguyen-Xuan H, Dai KY, Lam KY: On the essence and the evaluation of the shape functions for the smoothed finite element method (SFEM). Int J Numer Methods Eng 2009, 77:1863–1869.

Liu GR, Nguyen-Thoi T, Nguyen-Xuan H, Lam KY: A node-based smoothed finite element method (NS-FEM) for upper bound solutions to solid mechanics problems. Comput Struct 2009, 87:14–26.

Nguyen-Thoi T, Liu GR, Nguyen-Xuan H, Nguyen-Tran C: Adaptive analysis using the node-based smoothed finite element method (NS-FEM). Commun Numer Methods Eng 2011, 27:198–218.

Nguyen-Thoi T, Liu GR, Nguyen-Xuan H: Additional properties of the node-based smoothed finite element method (NS-FEM) for solid mechanics problems. Int J Comp Methods 2009, 6:633–666.

Liu GR, Nguyen-Thoi T, Lam KY: An edge-based smoothed finite element method (ES-FEM) for static and dynamic problems of solid mechanics. J Sound Vib 2009, 320:1100–1130.

Nguyen-Thoi T, Liu GR, Nguyen-Xuan H: An n -sided polygonal edge-based smoothed finite element method (nES-FEM) for solid mechanics. Commun Numer Methods Eng 2011, 27:1446–1472.

Nguyen-Thoi T, Liu GR, Lam KY, Zhang GY: A face-based smoothed finite element method (FS-FEM) for 3D linear and nonlinear solid mechanics problems using 4-node tetrahedral elements. Int J Numer Methods Eng 2009, 78:324–353.

Liu GR, Nguyen-Thoi T, Lam KY: A novel alpha finite element method (αFEM) for exact solution to mechanics problems using triangular and tetrahedral elements. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 2008, 197:3883–3897.

Liu GR, Nguyen-Thoi T, Lam KY: A novel FEM by scaling the gradient of strains with factor α (αFEM). Comput Mech 2009, 43:369–391.

Liu GR, Nguyen-Xuan H, Nguyen-Thoi T, Xu X: A novel Galerkin-like weakform and a superconvergent alpha finite element method (SαFEM) for mechanics problems using triangular meshes. J Comput Phys 2009, 228:4055–4087.

Liu GR, Nguyen-Xuan H, Nguyen-Thoi T: A variationally consistent αFEM (VCαFEM) for solid mechanics problems. Int J Numer Methods Eng 2011, 85:461–497.

Liu GR, Nguyen-Thoi T, Dai KY, Lam KY: Theoretical aspects of the smoothed finite element method (SFEM). Int J Numer Methods Eng 2007, 71:902–930.

Liu GR, Nguyen-Xuan H, Nguyen-Thoi T: A theoretical study on NS/ES-FEM: properties, accuracy and convergence rates. Int J Numer Methods Eng 2010, 84:1222–1256.

Nguyen-Xuan H, Nguyen-Thoi T: A stabilized smoothed finite element method for free vibration analysis of Mindlin-Reissner plates. Int J Num Methods Biomed Eng 2009, 25:882–906.

Cui XY, Liu GR, Li GY, Zhao X, Nguyen-Thoi T, Sun GY: A smoothed finite element method (SFEM) for linear and geometrically nonlinear analysis of plates and shells. CMES-Comp Model Eng Sci 2008, 28:109–125.

Nguyen-Xuan H, Rabczuk T, Nguyen-Thanh N, Nguyen-Thoi T, Bordas S: A node-based smoothed finite element method (NS-FEM) with stabilized discrete shear gap technique for analysis of Reissner-Mindlin plates. Comput Mech 2010,46(5):679–701.

Nguyen-Xuan H, Loc TV, Chien TH, Nguyen-Thoi T: Analysis of functionally graded plates by an efficient finite element method with node-based strain smoothing. Thin-Walled Struct 2012, 54:1–18.

Thai-Hoang C, Loc T-V, Tran-Trung D, Nguyen-Thoi T, Nguyen-Xuan H: Analysis of laminated composite plates using higher-order shear deformation plate theory and node-based smoothed discrete shear gap method. Appl Math Model 2012, 36:5657–5677.

Nguyen-Xuan H, Tran-Vinh L, Nguyen-Thoi T, Vu-Do HC: Analysis of functionally graded plates using an edge-based smoothed finite element method. Compos Struct 2011,93(11):3019–3039.

Phan-Dao HH, Nguyen-Xuan H, Thai-Hoang C, Nguyen-Thoi T, Rabczuk T: An edge-based smoothed finite element method for analysis of laminated composite plates. Int J Comp Methods 2013,10(1):1340005.

Nguyen-Thoi T, Phung-Van P, Nguyen-Xuan H, Thai-Hoang H: A cell-based smoothed discrete shear gap method using triangular elements for static and free vibration analyses of Reissner–Mindlin plates. Int J Numer Methods Eng 2012,91(7):705–741.

Trung NT, Bui-Xuan T, Phung-Van P, Nguyen-Hoang S, Nguyen-Xuan H: An edge-based smoothed three-node Mindlin plate element (ES-MIN3) for static and free vibration analyses of plates. KSCE J Civ Eng 2013. in press

Phung-Van P, Nguyen-Thoi T, Tran V, Nguyen-Xuan H: A cell-based smoothed discrete shear gap method (CS-FEM-DSG3) based on the C 0 -type higher-order shear deformation theory for static and free vibration analyses of functionally graded plates. Comput Mater Sci 2013, 79:857–872.

Nguyen-Thoi T, Bui-Xuan T, Phung-Van P, Nguyen-Xuan H, Ngo-Thanh P: Static, free vibration and buckling analyses of stiffened plates by CS-FEM-DSG3 using triangular elements. Comput Struct 2013, 125:100–113.

Nguyen-Thoi T, Phung-Van P, Thai-Hoang C, Nguyen-Xuan H: A cell-based smoothed discrete shear gap method (CS-FEM-DSG3) using triangular elements for static and free vibration analyses of shell structures. Int J Mech Sci 2013, 74:32–45.

Nguyen-Xuan H, Liu GR, Thai-Hoang C, Nguyen-Thoi T: An edge-based smoothed finite element method with stabilized discrete shear gap technique for analysis of Reissner-Mindlin plates. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 2009, 199:471–489.

Nguyen-Xuan H, Liu GR, Nguyen-Thoi T, Nguyen-Tran C: An edge-based smoothed finite element method (ES-FEM) for analysis of two-dimensional piezoelectric structures. Smart Mater Struct 2009, 18:1–12.

Phung-Van P, Nguyen-Thoi T, Le-Dinh T, Nguyen-Xuan H: Static, free vibration analyses and dynamic control of composite plates integrated with piezoelectric sensors and actuators by the cell-based smoothed discrete shear gap method (CS-FEM-DSG3). Smart Mater Struct 2013, 22:095026.

Liu GR, Chen L, Nguyen-Thoi T, Zeng K, Zhang GY: A novel singular node-based smoothed finite element method (NS-FEM) for upper bound solutions of cracks. Int J Numer Methods Eng 2010, 83:1466–1497.

Nguyen-Thoi T, Liu GR, Vu-Do HC, Nguyen-Xuan H: An edge-based smoothed finite element method (ES-FEM) for visco-elastoplastic analyses of 2D solids using triangular mesh. Comput Mech 2009, 45:23–44.

Nguyen-Thoi T, Vu-Do HC, Rabczuk T, Nguyen-Xuan H: A node-based smoothed finite element method (NS-FEM) for upper bound solution to visco-elastoplastic analyses of solids using triangular and tetrahedral meshes. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 2010, 199:3005–3027.

Nguyen-Thoi T, Liu GR, Vu-Do HC, Nguyen-Xuan H: A face-based smoothed finite element method (FS-FEM) for visco-elastoplastic analyses of 3D solids using tetrahedral mesh. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 2009, 198:3479–3498.

Tran TN, Liu GR, Nguyen-Xuan H, Nguyen-Thoi T: An edge-based smoothed finite element method for primal-dual shakedown analysis of structures. Int J Numer Methods Eng 2010, 82:917–938.

Nguyen-Xuan H, Rabczuk T, Nguyen-Thoi T, Tran TN, Nguyen-Thanh N: Computation of limit and shakedown loads using a node-based smoothed finite element method. Int J Numer Methods Eng 2012, 90:287–310.

Le-Van C, Nguyen-Xuan H, Askes H, Rabczuk T, Nguyen-Thoi T: Computation of limit load using edge-based smoothed finite element method and second-order cone programming. Int J Comp Methods 2013,10(1):1340005.

Nguyen-Thoi T, Phung-Van P, Rabczuk T, Nguyen-Xuan H, Le-Van C: Free and forced vibration analysis using the n -sided polygonal cell-based smoothed finite element method ( n CS-FEM). Int J Comp Methods 2013,10(1):1340008.

Nguyen-Thoi T, Phung-Van P, Rabczuk T, Nguyen-Xuan H, Le-Van C: An application of the ES-FEM in solid domain for dynamic analysis of 2D fluid-solid interaction problems. Int J Comp Methods 2013,10(1):1340003.

Nguyen-Thoi T, Phung-Van P, Luong-Van H, Nguyen-Van H, Nguyen-Xuan H: A cell-based smoothed three-node Mindlin plate element (CS-MIN3) for static and free vibration analyses of plates. Comput Mech 2013, 51:65–81.

Tessler A, Hughes TJR: A three-node Mindlin plate element with improved transverse shear. Comp Methods Appl Mech Eng 1985, 50:71–101.

Makrodimopoulos A, Martin CM: Upper bound limit analysis using discontinuous quadratic displacement fields. Commun Numer Methods Eng 2008, 24:911–927.

Fox EN: Limit analysis for plates: the exact solution for a clamped square plate of isotropic homogeneous material obeying square yield criterion and loaded by uniform pressure. Philos Trans Royal Soc A 1974, 277:121–155.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Vietnam National Foundation for Science & Technology Development (NAFOSTED), Ministry of Science & Technology, under the basic research program (Project No.: 107.02-2012.05).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

NTT proposed the main idea of extending the CS-MIN3 to the limit analysis of Mindlin plates, carriout out the theory model, numerical discretization model, and revising the manuscript. PVP carried out the numerical results and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. LVC carried out the source code of the limit analysis for Kirchhoff plates. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This article [1] has been retracted by Professor Nguyen-Dang Hung, Editor-in-Chief of Asia Pacific Journal on Computational Engineering.

Upon investigation carried out according to the Committee on Publication Ethics guidelines, it has been found that the authors have duplicated substantial parts from the following article by T. Nguyen-Thoi, P. Phung-Van, M.H. Nguyen-Thoi, H. Dang-Trung [2], published in Journal of Computational Applied Mathematics.

This is a violation of publication ethics which, in accordance with the Springer Policy on Publishing Integrity, warrants a retraction of the article and a notice to this effect to be published in the journal.

A retraction note to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40540-015-0013-z.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Trung, NT., Phuc, PV. & Canh, LV. RETRACTED ARTICLE: A limit analysis of Mindlin plates using the cell-based smoothed triangular element CS-MIN3 and second-order cone programming (SOCP). Asia Pac. J. Comput. Engin. 1, 6 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2196-1166-1-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2196-1166-1-6