Abstract

Manganese (Mn) is an essential element that is required in trace amount for normal growth, development as well maintenance of proper function and regulation of numerous cellular and biochemical reactions. Yet, excessive Mn brain accumulation upon chronic exposure to occupational or environmental sources of this metal may lead to a neurodegenerative disorder known as manganism, which shares similar symptoms with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (PD). In recent years, Mn exposure has gained public health interest for two primary reasons: continuous increased usage of Mn in various industries, and experimental findings on its toxicity, linking it to a number of neurological disorders. Since the first report on manganism nearly two centuries ago, there have been substantial advances in the understanding of mechanisms associated with Mn-induced neurotoxicity. This review will briefly highlight various aspects of Mn neurotoxicity with a focus on the role of astrocytic glutamate transporters in triggering its pathophysiology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Review

Mn is essential but needs to be in the balance

Mn is a ubiquitous element present naturally in the environment, including water and food. In the human body, Mn is found in all tissues where it is required for normal amino acid, lipid, protein and carbohydrate metabolism, and ATP generation. Mn also participates in blood clotting and sugar homeostasis, immune responsiveness, digestion, reproduction, and bone growth [1–3]. It is a critical component of numerous metalloenzymes, including Mn superoxide dismutase, arginase, phosphoenolpyruvate decarboxylase and glutamine synthetase [4–6], to name a few. Despite its requirement in multiple physiological processes, elevated levels of Mn trigger toxicity, particularly within the central nervous system (CNS), causing cognitive, psychiatric and motor abnormalities [7, 8]. In humans, Mn deficiency is rare as it is abundant in diets, but in extenuating conditions it may contribute to developmental defects, including malformation of bones, altered macromolecular metabolism, reduced fertility, weakness and enhanced susceptibility to seizures [3, 9, 10]. Mn deficiency has also been shown to induce skeletal defects and impaired lipid metabolism [11, 12].

Sources of human exposure

Mn is naturally abundant in the Earth’s crust (0.1%) and soil (40–900 mg/kg) [13, 14]. Mn is found as oxides, carbonates and silicates in minerals. The versatile chemical properties of Mn have expanded its industrial use in glass, ceramics, paint and adhesive industries, as well as in welding. The wide usage of Mn in a range of industries has led to global health concerns. Indeed, occupational exposures to Mn have been documented in multiple industries, including ferroalloy smelting, welding, mining, battery, glass and ceramics [15–19].

The primary source of Mn exposure in the general human population is from diet, which is estimated to contain 0.9-10 mg Mn per day [20]. Rice, grains and nuts are rich sources of Mn with excess of 30 mg/kg, while Mn content in tea is 0.4-1.3 mg/cup. Mn drinking water levels are in the range of 1–100 μg/L [21]. The high Mn content in infant formulas compared to human milk, has recently drawn public attention [22], along with Mn in parenteral nutrition. The latter is considered a risk factor for Mn-induced toxicity since the normal intestinal regulatory mechanisms are bypassed, rendering intravenously delivered Mn 100% bioavailable [23, 24]. Mn in fumes, aerosols or suspended particulate matters is deposited in the upper and lower respiratory tract, with subsequent entry into the bloodstream. An Mn-containing gasoline anti-knock additives additive, methylcyclopentadienyl manganese tricarbonyl (MMT), has been introduced in several countries, representing another source of Mn exposure via inhalation [25, 26]. Designer drugs, such as methcathinone hydrochloride (ephedrine), where potassium permanganate is used as an oxidant for the synthesis of the illicit drugs [27] has also been shown to cause neurodegenerative sequalae in drug abusers, consistent with PD-like symptomology.

Mn absorption, transport and excretion

Diet represents the major source of Mn in humans. The gastrointestinal tract absorbs 1-5% of ingested Mn; 60-70% of inhaled Mn is exhaled by the lungs [28, 29]. The uptake of Mn is tightly regulated and excess Mn is excreted through the bile [30]. Both active transport and passive diffusion mechanisms regulate oral Mn absorption and the process is governed by various factors, including dietary levels of Mn and other minerals as well as age [20, 30, 31]. Among other metals, iron (Fe) stores are particularly important given the inverse relationship between cellular Fe levels and Mn uptake, as evidenced by increased transport of orally administered Mn in states of Fe deficiency [32, 33]. In blood, Mn+2 is predominantly (>99%) in the 2+ oxidation state and mainly bound to β-globulin and albumin. A small fraction of Mn+3 is complexed with transferrin [34, 35]. Mn (in the 2+ oxidation state) transport across the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and cell membranes is facilitated by the divalent metal ion transporter 1 (DMT1), N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor channel and Zip8 [36–38], to name a few. Transferrin is the most efficient transport system for Mn in the 3+ oxidation state [39]. Mn is distributed throughout the brain and the highest Mn levels are found in the globus pallidus and other nuclei of the basal ganglia (striatum, substantia nigra) [40, 41]. DMT1 and transferrin also regulate Mn uptake both in astrocytes and neurons [42, 43]. Generally, the intracellular Mn concentration is higher in tissues rich in mitochondria and pigmentation. The highest Mn levels are noted in bone, liver, pancreas and kidney compared to other tissues [44].

Mn neurotoxicity

Mn in neurological disorders

Chronic inhalation of air-borne Mn particulates represents the major cause of human neurotoxicity, though there is growing number of reports on Mn toxicity resulting from consumption of Mn-adulterated drinking water [45, 46]. Occupational exposures represent the predominant source of excessive Mn exposure [47]. Manganism, first described by Couper in 1837 [48] is a clinical disorder characterized by psychological and neurological abnormalities that shares multiple analogous symptoms with idiopathic PD [Reviewed in [49]]. The early symptoms of manganism include hallucinations, psychoses and various behavioral disturbances soon followed by postural instability, dystonia, bradykinesia and rigidity [50]. Despite their resemblance in clinical features, manganism is clinically distinguishable from PD [51]. Mn-induced neurotoxicity affects mainly the globus pallidus as well as the cortex and hypothalamus [52, 53], distinct from the striatal changes associated with PD. Excessive CNS Mn levels may contribute in the pathogenesis of PD, causing loss of dopamine in the striatum, death of non-dopaminergic (DAergic) neurons in the globus pallidus, and damage to glutamatergic and GABAergic projections [54, 55]. Mn has also been shown to increase fibril formation by α-synuclein along with its expression and aggregation [53, 56, 57]. While playing a major role in the etiology of PD [58], the precise role of α-synuclein in Mn-induced neurotoxicity has yet to be determined. A role for Mn has also been advanced in the etiology of Huntington’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease [Reviewed in [49]].

Mechanism of Mn Neurotoxicity

Mitochondrial dysfunction

Mitochondria serve as the primary storage site for intracellular Mn where it is taken up by the calcium uniporter [59]. Mn is also an important cofactor for various mitochondrial enzymes and, thus, the elevation in Mn levels in this organelle can directly interfere with oxidative phosphorylation. Mn inhibits the function of F1-ATPase and the formation of complex I of the electron transport chain, thereby interfering with cellular ATP synthesis [60, 61].

Oxidative stress

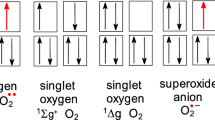

Elevated intra-mitochondrial Mn levels trigger oxidative stress, generating the excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS), causing mitochondrial dysfunction [61, 62]. The transition of Mn+2 to Mn+3 increases its pro-oxidant capacity [63]. Mn-induced oxidative stress leads to the opening of mitochondrial transition pore (MTP), resulting in increased solubility to protons, ions and solutes, loss of the mitochondrial inner membrane potential, impairment of oxidative phosphorylation and ATP synthesis and mitochondrial swelling [64, 65]. Furthermore, Mn exposure has also been linked to the activation of signaling pathways involved in response to oxidative stress, including nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1) [66, 67].

Apoptosis

Neuronal cell death by apoptosis has been considered to play a major role in neurodegenerative diseases, including PD [68]. Mn has been shown to trigger apoptosis in DAergic neurons in a caspase-3-dependent manner by activation of protein kinase C delta (PKC-δ) [69]. Similarly, Mn has been shown to cause apoptotic cell death in astrocytes by mitochondrial pathways involving cytochrome c release and caspase activation [64, 70].

Inflammation

Although the oxidative stress induced by mitochondrial dysfunction is regarded as the major pathological mechanism of Mn neurotoxicity, recent studies also suggest a proinflammatory role for Mn, which involves the activation of glial cells characterized by the release of non-neuronal derived ROS, such as nitric oxide (NO), cytokines, prostaglandins and H2O2 [71–73]. Mn potentiates the release of several cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β from the activated glial cells, thereby activating various transcription factors including NF-kB, AP-1 and kinases including ERK, JNK, AKT, and PKC-α [Reviewed in [74]].

The effect of Mn on astrocytic glutamate transporters

Astrocytes are the site of early dysfunction and damage in Mn neurotoxicity. Astrocytes are the most abundant CNS cells (~50% by volume), and they perform numerous essential functions for normal neuronal activity, such as glutamate uptake, glutamine release, K+ and H+ buffering and volume regulation [36, 75, 76]. Astrocytes accumulate up to 50-fold higher Mn concentrations compared to neurons, thus serving as the main homeostatic and storage site for this metal [75, 77]. The intracellular concentration of Mn in astrocytes is ~50-75 μM where it is an essential cofactor for the astrocyte-specific enzyme glutamine synthetase, which catalyzes the conversion of glutamate to glutamine [78, 79]. The excessive accumulation of Mn in astrocytes mediates neurotoxicity primarily by oxidative stress and impairment of glutamate transporters [80, 81]. Mn toxicity has been shown to cause astrocytic alterations in primate models, and exposure of pathophysiologically relevant Mn concentrations in astrocytes in vitro causes time-and concentration-dependent cell swelling secondary to oxidative stress [82, 83]. One of the proposed mechanisms of Mn-induced neurotoxicity in astrocytes is alteration in glutamate homeostasis due to impairment of glutamate transporters [84]. Mn has also been shown to downregulate the expression and function of glutamine transporters, resulting in reduced glutamine uptake [85]. The impairment of glutamate/glutamine transporters results in increased extracellular glutamate levels that elicit excitatory neurotoxicity. In support of this mechanism, we and others have shown that estrogen and selective estrogen receptor modulators protect astrocytes from Mn-induced neurotoxicity by upregulating the expression and function of glutamate transporters [86–88]. Moreover, Mn also activates selective cellular signaling pathways that mediate alterations in glutamate-glutamine homeostasis. The decrease in glutamine uptake after the activation of PKC-δ by Mn represents a typical example of the involvement of signaling pathways in Mn-induced neurotoxicity [89].

Although it is widely accepted that Mn impairs the expression and function of the two main glutamate transporters (GLAST and GLT-1), its mechanism of action at the transcriptional levels remains unknown. The increased production of ROS and TNF-α by Mn is thought to be the principal cause that leads to impairment in glutamate transporter function. ROS inhibit astrocyte glutamate uptake, and TNF-α decreases GLAST and GLT-1 protein and mRNA levels [90–92]. Oxidative stress also plays an important role in the regulation of glutamate transporter function since the activity of glutamate transporters is regulated by the redox state of reactive cysteine residues, with a dramatic decrease in activity once the reduced cysteine is oxidized [93]. Furthermore, glutamate uptake by the recombinant glutamate transporters EAAT1, EAAT2 and EAAT3 was found to be inhibited by peroxynitrite and H2O2 and restored upon treatment with the reducing agent, dithithreotol, suggesting a role for oxidative stress in the regulation of glutamate transporters activity [94]. TNF-α is a key neuroinflammatory mediator of neurotoxicity and neurodegeneration, and Mn increases the levels of this cytokine [95]. Several studies also corroborate the reduction in the expression and activity of glutamate transporters by TNF-α, highlighting its role as a negative regulator of the transporter [90, 92]. NF-kB and MAPK signaling pathways mediate TNF-α-induced reduction in GLT-1 expression, since the inhibition of these pathways restores the decrease in TNF-α induced GLT-1 expression and function [92].

Conclusion

Chronic excessive exposures to Mn represent a global health concern as growing evidences suggests that Mn accumulation in the brain may be a predisposing factor for several neurodegenerative diseases. Studies over the past several decades have provided invaluable insights into the cause, effects and mechanisms of Mn-induced neurotoxicity. The recent findings on the involvement of glutamate transporters and cellular signaling pathways in Mn-induced neurotoxicity provide not only new insights into the molecular mechanisms of Mn-induced neurotoxicity, but also provide new therapeutic targets in the development of novel drugs to attenuate the symptoms associated with manganism, PD and other related neurodegenerative disorders.

References

Aschner M, Erikson KM, Dorman DC: Crit Rev Toxicol. 2005, 35: 1–32. 10.1080/10408440590905920

Erikson KM, Thompson K, Aschner J, Aschner M: Pharmacol Ther. 2007, 113: 369–377. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.09.002

Aschner JL, Aschner M: Mol Aspects Med. 2005, 26: 353–362. 10.1016/j.mam.2005.07.003

Baly DL: J Nutr. 1985, 119: 327.

Bentle LA, Lardy HA: J Biol Chem. 1976, 251: 2916–2921.

Stallings WC, Metzger AL, Pattridge KA, Fee JA, Ludwig ML: Free Radic Res Commun. 1991,12–13(Pt 1):259–268.

Dobson AW, Erikson KM, Aschner M: Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004, 1012: 115–128. 10.1196/annals.1306.009

Pal PK, Samii A, Calne DB: Neurotoxicology. 1999, 20: 227–238.

Aschner M, Shanker G, Erikson K, Yang J, Mutkus LA: Neurotoxicology. 2002, 23: 165–168. 10.1016/S0161-813X(02)00056-6

Keen CL, Ensunsa JL, Watson MH, Baly DL, Donovan SM, Monaco MH, Clegg MS: Neurotoxicology. 1999, 20: 213–223.

Hurley LS: Physiol Rev. 1981, 61: 249–295.

Klimis-Tavantzis DJ, Leach RM Jr, Kris-Etherton PM: J Nutr. 1983, 113: 328–336.

Burton NC, Guilarte TR: Environ Health Perspect. 2009, 117: 325–332.

Cooper WC: J Toxicol Environ Health. 1984, 14: 23–46. 10.1080/15287398409530561

Bader M, Dietz MC, Ihrig A, Triebig G: Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1999, 72: 521–527. 10.1007/s004200050410

Bast-Pettersen R, Ellingsen DG, Hetland SM, Thomassen Y: Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2004, 77: 277–287. 10.1007/s00420-003-0491-0

Bowler RM, Nakagawa S, Drezgic M, Roels HA, Park RM, Diamond E, Mergler D, Bouchard M, Bowler RP, Koller W: Neurotoxicology. 2007, 28: 298–311. 10.1016/j.neuro.2006.11.001

Montes S, Riojas-Rodriguez H, Sabido-Pedraza E, Rios C: Environ Res. 2008, 106: 89–95. 10.1016/j.envres.2007.08.008

Srivastava AK, Gupta BN, Mathur N, Murty RC, Garg N, Chandra SV: Vet Hum Toxicol. 1991, 33: 280–282.

Finley JW, Davis CD: BioFactors (Oxford, England). 1999, 10: 15–24. 10.1002/biof.5520100102

ATSDR: Toxicological Profile for Manganese. Atlanta. GA: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry; 2000.

Krachler M, Rossipal E: Ann Nutr Metab. 2000, 44: 68–74. 10.1159/000012823

Bertinet DB, Tinivella M, Balzola FA, de Francesco A, Davini O, Rizzo L, Massarenti P, Leonardi MA, Balzola F: JPEN. Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition. 2000, 24: 223–227. 10.1177/0148607100024004223

Hardy G: Gastroenterology. 2009, 137: S29-S35. 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.011

Davis JM: Environ Health Perspect. 1998,106(Suppl 1):191–201. 10.1289/ehp.98106s1191

Kaiser J: Science (New York, N.Y.). 2003, 300: 926–928. 10.1126/science.300.5621.926

Sikk K, Taba P, Haldre S, Bergquist J, Nyholm D, Askmark H, Danfors T, Sorensen J, Thurfjell L, Raininko R, Eriksson R, Flink R, Farnstrand C, Aquilonius SM: Acta Neurol Scand. 2010, 121: 237–243. 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2009.01189.x

Davidsson L, Cederblad A, Hagebo E, Lonnerdal B, Sandstrom B: J Nutr. 1998, 118: 1517–1521.

Mena I: Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1974, 4: 487–491.

Davis CD, Zech L, Greger JL: Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine (New York, N.Y.) 1993, 202: 103–108.

Dorman DC, Struve MF, James RA, McManus BE, Marshall MW, Wong BA: Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2001, 60: 242–251. 10.1093/toxsci/60.2.242

Davis CD, Malecki EA, Greger JL: Am J Clin Nutr. 1992, 56: 926–932.

Gunshin H, Mackenzie B, Berger UV, Gunshin Y, Romero MF, Boron WF, Nussberger S, Gollan JL, Hediger MA: Nature. 1997, 388: 482–488. 10.1038/41343

Aisen P, Aasa R, Redfield AG: J Biol Chem. 1969, 244: 4628–4633.

Critchfield JW, Keen CL: Metabolism: clinical and experimental. 1992, 41: 1087–1092. 10.1016/0026-0495(92)90290-Q

Aschner M, Gannon M: Brain Res Bull. 1994, 33: 345–349. 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90204-6

Au C, Benedetto A, Aschner M: Neurotoxicology. 2008, 29: 569–576. 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.04.022

Itoh K, Sakata M, Watanabe M, Aikawa Y, Fujii H: Neuroscience. 2008, 154: 732–740. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.080

Aschner M, Aschner JL: Brain Res Bull. 1990, 24: 857–860. 10.1016/0361-9230(90)90152-P

Dorman DC, Struve MF, Marshall MW, Parkinson CU, James RA, Wong BA: Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2006, 92: 201–210. 10.1093/toxsci/kfj206

Guilarte TR, McGlothan JL, Degaonkar M, Chen MK, Barker PB, Syversen T, Schneider JS: Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2006, 94: 351–358. 10.1093/toxsci/kfl106

Erikson KM, Aschner M: Neurotoxicology. 2006, 27: 125–130. 10.1016/j.neuro.2005.07.003

Suarez N, Eriksson H: J Neurochem. 1993, 61: 127–131. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03546.x

Rehnberg GL, Hein JF, Carter SD, Laskey JW: J Toxicol Environ Health. 1980, 6: 217–226. 10.1080/15287398009529844

Mena I, Marin O, Fuenzalida S, Cotzias GC: Neurology. 1967, 17: 128–136. 10.1212/WNL.17.2.128

Roels HA, Bowler RM, Kim Y, Claus Henn B, Mergler D, Hoet P, Gocheva VV, Bellinger DC, Wright RO, Harris MG, Chang Y, Bouchard MF, Riojas-Rodriguez H, Menezes-Filho JA, Tellez-Rojo MM: Neurotoxicology. 2012, 33: 872–880. 10.1016/j.neuro.2012.03.009

Mergler D, Huel G, Bowler R, Iregren A, Belanger S, Baldwin M, Tardif R, Smargiassi A, Martin L: Environ Res. 1994, 64: 151–180. 10.1006/enrs.1994.1013

Couper J: Br Ann Med Pharmacol. 1837, 1: 41–42.

Bowman AB, Kwakye GF, Hernandez EH, Aschner M: Journal of trace elements in medicine and biology : organ of the Society for Minerals and Trace Elements (GMS). 2011, 25: 191–203. 10.1016/j.jtemb.2011.08.144

Olanow CW: Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004, 1012: 209–223. 10.1196/annals.1306.018

Calne DB, Chu NS, Huang CC, Lu CS, Olanow W: Neurology. 1994, 44: 1583–1586. 10.1212/WNL.44.9.1583

Yamada M, Ohno S, Okayasu I, Okeda R, Hatakeyama S, Watanabe H, Ushio K, Tsukagoshi H: Acta Neuropathol. 1986, 70: 273–278. 10.1007/BF00686083

Verina T, Schneider JS, Guilarte TR: Toxicol Lett. 2012.

Guilarte TR: Environ Health Perspect. 2010, 118: 1071–80. 10.1289/ehp.0901748

Sikk K, Haldre S, Aquilonius SM, Taba P: Parkinson's disease. 2011, 2011: 865319.

Li Y, Sun L, Cai T, Zhang Y, Lv S, Wang Y, Ye L: Brain Res Bull. 2010, 81: 428–33. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2009.11.007

Uversky VN, Li J, Fink AL: J Biol Chem. 2001, 276: 44284–96. 10.1074/jbc.M105343200

Eller M, Williams DR: Clinical chemistry and laboratory medicine: CCLM /FESCC. 2011, 49: 403–8.

Gavin CE, Gunter KK, Gunter TE: Neurotoxicology. 1999, 20: 445–53.

Chen JY, Tsao GC, Zhao Q, Zheng W: Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2001, 175: 160–8. 10.1006/taap.2001.9245

Gavin CE, Gunter KK, Gunter TE: Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1992, 115: 1–5. 10.1016/0041-008X(92)90360-5

Milatovic D, Yin Z, Gupta RC, Sidoryk M, Albrecht J, Aschner JL, Aschner M: Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2007, 98: 198–205. 10.1093/toxsci/kfm095

Reaney SH, Smith DR: Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005, 205: 271–81. 10.1016/j.taap.2004.10.013

Yin Z, Aschner JL, dos Santos AP, Aschner M: Brain Res. 2008, 1203: 1–11.

Zoratti M, Szabo I: Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995, 1241: 139–76. 10.1016/0304-4157(95)00003-A

Ramesh GT, Ghosh D, Gunasekar PG: Toxicol Lett. 2002, 136: 151–8. 10.1016/S0378-4274(02)00332-6

Wise K, Manna S, Barr J, Gunasekar P, Ramesh G: Toxicol Lett. 2004, 147: 237–44. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2003.11.007

Dauer W, Przedborski S: Neuron. 2003, 39: 889–909. 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00568-3

Latchoumycandane C, Anantharam V, Kitazawa M, Yang Y, Kanthasamy A, Kanthasamy AG: J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005, 313: 46–55.

Gonzalez LE, Juknat AA, Venosa AJ, Verrengia N, Kotler ML: Neurochem Int. 2008, 53: 408–15. 10.1016/j.neuint.2008.09.008

Liu X, Sullivan KA, Madl JE, Legare M, Tjalkens RB: Toxicological sciences: an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2006, 91: 521–31. 10.1093/toxsci/kfj150

Zhang P, Lokuta KM, Turner DE, Liu B: J Neurochem. 2010, 112: 434–43. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06477.x

Zhang P, Wong TA, Lokuta KM, Turner DE, Vujisic K, Liu B: Exp Neurol. 2009, 217: 219–30. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.02.013

Filipov NM, Dodd CA: Journal of applied toxicology: JAT. 2012, 32: 310–7. 10.1002/jat.1762

Aschner M, Guilarte TR, Schneider JS, Zheng W: Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007, 221: 131–47. 10.1016/j.taap.2007.03.001

Chen MK, Lee JS, McGlothan JL, Furukawa E, Adams RJ, Alexander M, Wong DF, Guilarte TR: Neurotoxicology. 2006, 27: 229–36. 10.1016/j.neuro.2005.10.008

Aschner M, Erikson KM, Herrero Hernandez E, Tjalkens R: Neuromolecular Med. 2009, 11: 252–66. 10.1007/s12017-009-8083-0

Gorovits R, Avidan N, Avisar N, Shaked I, Vardimon L: Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997, 94: 7024–9. 10.1073/pnas.94.13.7024

Tholey G, Ledig M, Mandel P, Sargentini L, Frivold AH, Leroy M, Grippo AA, Wedler FC: Neurochem Res. 1988, 13: 45–50. 10.1007/BF00971853

Brouillet EP, Shinobu L, McGarvey U, Hochberg F, Beal MF: Exp Neurol. 1993, 120: 89–94. 10.1006/exnr.1993.1042

Desole MS, Sciola L, Delogu MR, Sircana S, Migheli R, Miele E: Neurochem Int. 1997, 31: 169–76. 10.1016/S0197-0186(96)00146-5

Olanow CW, Good PF, Shinotoh H, Hewitt KA, Vingerhoets F, Snow BJ, Beal MF, Calne DB, Perl DP: Neurology. 1996, 46: 492–8. 10.1212/WNL.46.2.492

Rama Rao KV, Reddy PV, Hazell AS, Norenberg MD: Neurotoxicology. 2007, 28: 807–12. 10.1016/j.neuro.2007.03.001

Erikson K, Aschner M: Neurotoxicology. 2002, 23: 595–602. 10.1016/S0161-813X(02)00012-8

Sidoryk-Wegrzynowicz M, Lee E, Albrecht J, Aschner M: J Neurochem. 2009, 110: 822–30. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06172.x

Deng Y, Xu Z, Xu B, Xu D, Tian Y, Feng W: Biol Trace Elem Res. 2012, 148: 242–9. 10.1007/s12011-012-9365-1

Lee ES, Sidoryk M, Jiang H, Yin Z, Aschner M: J Neurochem. 2009, 110: 530–44. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06105.x

Lee ES, Yin Z, Milatovic D, Jiang H, Aschner M: Toxicological sciences: an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2009, 110: 156–67. 10.1093/toxsci/kfp081

Sidoryk-Wegrzynowicz M, Lee ES, Ni M, Aschner M: Glia. 2010, 58: 1905–12. 10.1002/glia.21060

Sitcheran R, Gupta P, Fisher PB, Baldwin AS: EMBO J. 2005, 24: 510–20. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600555

Sorg O, Horn TF, Yu N, Gruol DL, Bloom FE: Molecular medicine (Cambridge, Mass.). 1997, 3: 431–40.

Su ZZ, Leszczyniecka M, Kang DC, Sarkar D, Chao W, Volsky DJ, Fisher PB: Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003, 100: 1955–60. 10.1073/pnas.0136555100

Trotti D, Danbolt NC, Volterra A: Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1998, 19: 328–34. 10.1016/S0165-6147(98)01230-9

Miralles VJ, Martinez-Lopez I, Zaragoza R, Borras E, Garcia C, Pallardo FV, Vina JR: Brain Res. 2001, 922: 21–9. 10.1016/S0006-8993(01)03124-9

Crittenden PL, Filipov NM: Toxicology in vitro : an international journal published in association with BIBRA. 2008, 22: 18–27. 10.1016/j.tiv.2007.07.004

Acknowledgements

The studies in our laboratories are supported by NIH grants R01 ES 10563, P30 ES 00267 and SC1 GM089630.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no any competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

PK drafted the initial manuscript, EL and MA corrected, edited and finalized it. All the authors read and approve the final version of the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Karki, P., Lee, E. & Aschner, M. Manganese Neurotoxicity: a Focus on Glutamate Transporters. Ann of Occup and Environ Med 25, 4 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/2052-4374-25-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2052-4374-25-4