Abstract

Background

Pseudodiaptomus annandalei is an estuarine species and being cultured as live feed for grouper fish larvae and other planktivores. We examined the predation behavior of P. annandalei adults when preying on ciliated protists (Euplotes sp.) and the effects of mono- and pluri-algal diets on ciliate predation by P. annandalei under laboratory conditions. The algal food comprised the pigmented flagellate Isochrysis galbana (4 ~ 5 μm) and Tetraselmis chui (17 ~ 20 μm).

Results

Males and females of P. annandalei consumed 8 ~ 15 ciliate cells/h. The probability of ciliate ingestion following an attack was a direct function of the copepod's hunger level. Conversely, the probability of prey rejection after capture was a negative function of the copepod's hunger level. Starved and poorly fed females showed a significantly lower rate of prey rejection compared to similarly treated males. The duration of handling a ciliate prey did not significantly differ between males and females of P. annandalei. Starved copepods spent less time handling a ciliate prey than fed copepods. Prey ingestion rates showed a negative relation with the feeding duration, whereas the prey rejection rate increased as the feeding duration increased. The ciliate consumption rate of P. annandalei was significantly lower in the presence of mixed algae. Neither I. galbana nor T. chui alone had any significant effect on ciliate consumption by P. annandalei.

Conclusions

The results confirmed that P. annandalei ingests bacterivorous heterotrophic protists even in the presence of autotrophic protists. Therefore, our results point to the role of P. annandalei in the transfer of microbial carbon to the classical food chain in estuarine and brackish water ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Copepods play a central role in transferring carbon energy from lower trophic levels to higher trophic levels such as fish in estuarine and marine food webs (Turner 2004). Pseudodiaptomus annandalei is a euryhaline species found perennially in coastal, estuarine, and brackish waters in the tropical and subtropical Indo-Pacific (Madhupratap 1987; Hwang et al. 2010; Kâ and Hwang 2011; Dahms et al. 2012; Dur et al. 2012). Recent laboratory studies and the perennial occurrence of this species in nature indicate that P. annandalei can utilize a wide spectrum of food (Hwang et al. 2010; Dhanker et al. 2012). In turn, this species constitutes a major portion of the diet of numerous estuarine fish larvae. Its mass culture is also being carried out, and it is currently being used as live feed in larviculture of grouper fish larvae and other planktivores (Doi et al. 1997; Hagiwara et al. 2001; Liao et al. 2001; Chen et al. 2006; Lee et al. 2010; Celino et al. 2012). P. annandalei was traditionally considered to be herbivorous and is commercially produced on a microalgal diet by the aquaculture industry. The mixotrophic and predatory nature of this species was recently shown by Cheng et al. (2011) and Dhanker et al. (2012). The feeding ecology of this species has been well documented on some commonly available microalgae (Liao et al. 2001; Chen et al. 2006; Beyrend-Dur et al. 2011) and rotifers (Dhanker et al. 2012). No information is as yet available on the feeding potential of P. annandalei on ciliate protists.

Ciliates were identified as a major food source of copepods in detritus-rich estuaries with lower chlorophyll levels (Landry et al. 1993; Atkinson 1996; Vincent and Hartmann 2001). Numerous studies proved that copepods can utilize considerable proportions of ciliate production (Kumar 2003; Huo et al. 2008; Fileman et al. 2010). Ciliate consumption rates by certain copepods were significantly higher than those for algae (Gifford and Dagg 1988; Vadstein et al. 2004; Loder et al. 2011; Küppersm and Claps 2012), and clearance rates for ciliates were equal as they cleared large algal cells (Tiselius 1989; Gifford and Dagg 1991). Because they can exploit food stocks more efficiently due to their higher metabolism and growth rates (Hansen 1992 Sherr and Sherr 2007), heterotrophic protists have a higher biomass conversion potential compared to autotrophic protists (Gifford 1991; Broglio et al. 2003; Tang and Taal 2005) and are more nutritionally important qualitatively and quantitatively in diets of copepods (Adriana et al. 2006). Therefore, ciliates may constitute an important food source for P. annandalei in nature where primary production is scarce. Ciliates may convert lipids obtained from their food to polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) (Sul and Erwin 1997) which are essential for copepod growth and reproduction. Ismar et al. (2008) reported that the estuarine copepod Acartia tonsa showed a behavioral preference for Euplotes over diatom feeding.

Copepods require sterols as an essential component for their growth and egg production (Ederington et al. 1995; Klein Breteler et al. 1999), and these are synthesized by the copepods themselves. Cholesterol synthesis was detected in the hypotrich ciliate protist Euplotes sp. (class Nassophorea) (Harvey and McManus 1991).

The feeding mechanism of copepods in nature is strongly influenced by the availability of alternate food sources (Kumar 1999a, b; 2003) and by the motility, density, size, age, reproductive stage, and abundance of prey (Jonsson and Tiselius 1990; Rao and Kumar 2002; Jakobsen et al. 2005; Tseng et al. 2009; Dhanker et al. 2012). Other factors are hunger level, satiation, age, and sex of the copepods (Salvanes and Hart 1998; Kumar and Rao 1999a, b; Asaeda et al. 2001; Rao and Kumar 2002; Kumar 2003; Dhanker et al. 2012). The ciliate, Euplotes sp., often coexists with P. annandalei, and it may be a preferred food source for copepods when primary production is limited. However, no information is available about P. annandalei predation on ciliate protists. The aim of this study was to understand the details of the ecological and behavioral attributes of P. annandalei predation on a ciliate protist (Euplotes sp.). We attempted to answer the following questions through this study: (a) Can P. annandalei utilize heterotrophic ciliate protists as a food source? (b) To what extent does the presence of autotrophic protists in its environment affect predation on heterotrophic protists?

Methods

Experimental organisms

Starter cultures of adult P. annandalei were isolated from zooplankton samples collected from a coastal brackish water pond of Taiwan. A monoculture was developed in a mixture of filtered seawater and autoclaved tap water, and this was inoculated into a 5-L aquarium that contained 4 L of medium. A mixture of the microalgae Isochrysis galbana and Tetraselmis chui, rotifer Brachionus rotundiformis, and ciliate Euplotes sp. was used as food for the copepods (Table 1). The culture was maintained at a salinity of 20 psu and 28°C under a photoperiod of 12 h of light and 12 h of dark. The copepod culture was maintained in the laboratory for ≥3 months prior to the experiment. Moreover, ≥200 ovigerous females of P. annandalei were collected to obtain freshly hatched nauplii to perform the experiment. All experiments were conducted with P. annandalei of a known age (18 to 20 days). The culture was continuously mildly aerated to keep the food uniformly distributed in the culture tank. The culture medium was renewed twice a week.

Ciliates of the genus Euplotes were originally isolated from the rotifer culture tank. They were propagated and maintained in a 2-L beaker at a salinity of 20 to 25 psu and fed to the unicellular alga I. galbana (Table 1). The abundance of Euplotes cells was determined using an inverted microscope. The culture medium was changed on alternate days with a mixture of filtered autoclaved seawater and autoclaved tap water (20 to 25 psu).

Mass cultures of both algal species (I. galbana and T. chui) were established in the laboratory. Algal culture media were prepared by enriching sterile filtered seawater with macronutrients and micronutrients (Walne medium; Walne 1970) in a 2-L borosilicate glass flask. Individual monocultures of both algae were maintained at a salinity of 20 psu at a photoperiod of 12 h of light and 12 h of dark. The algae were harvested in their exponential growth phase of the nutrient-replenished condition to prevent mineral nutrient limitation. Details of the experimental organisms are shown in Table 1.

Experimental protocol

All experiments were conducted at a salinity of 20 psu and at a fixed temperature (28°C) in BOD (biochemical oxygen demand). Experiments were conducted in three consecutive phases: (a) the effects of algal diets on ciliate consumption rates by males and females of P. annandalei, (b) ciliate ingestion in relation to the satiation level of copepods, and (c) elucidation of the act of ciliate capture by males and females of P. annandalei.

Effects of algal diets on ciliate consumption rates

Predation rates on ciliates by males and ovigerous and nonovigerous females of P. annandalei were examined in the presence and absence of an algal diet. The experimental protocol included the following: (a) ciliate prey alone, (b) ciliates with I. galbana, (c) ciliates with T. chui, and (d) ciliates with I. galbana and T. chui. Known-age individuals of P. annandalei were collected from stock cultures and transferred to a bowl containing 40 mL of medium 3 h prior to the experiment. P. annandalei was deprived of food for 3 h prior to the experiment. Subsequently, 40 cells of Euplotes sp. were introduced into each bowl, and five bowls were used for each treatment. The number of consumed cells was recorded after 60 min. P. annandalei was removed from the experimental bowl at the end of the test, and all remaining live prey from each bowl were carefully counted under a zoom stereomicroscope (Olympus SXZ 16; Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan) to obtain an estimate of the number consumed.

Feeding by P. annandalei as a function of satiation time and satiation level

The starting time for feeding by an animal to a voluntary pause despite food availability is considered the satiation duration. In total, five P. annandalei females (18 to 20 days old) were collected from the stock culture, individually placed in a 50-mL experimental bowl with 40 mL of water medium, and deprived of food for 3 h to estimate their satiation duration. Thereafter, 40 (1 ciliate individual (ind)/mL) ciliates were introduced into each experimental bowl containing P. annandalei. The number of consumed ciliates within 15 min was recorded as the first observation, and prey consumption was subsequently recorded at 30-min intervals. The number of ingested cells in 30 min was replaced with fresh cells to maintain a constant prey concentration (number of ciliates = 40/experimental bowl).

Predation efficiency (microscopic observation) as a function of hunger level

The predation behaviors of male and female P. annandalei on Euplotes sp. were examined in this experiment. The number of predatory steps such as prey searching, handling time, post-attack prey ingestion, and rejection probabilities in relation to the hunger level was recorded during the experiment. Well-fed, poorly fed (starved for 30 min), and starved (starved for 2 h) copepods were used for the experiment. Copepods were acclimated for 15 min in an experimental glass cavity block (4.5-cm diameter and 1.7-cm-deep petri dish) containing 20-mL medium at 20 psu. Moreover, the required number of ciliate cells was counted and stored in a separate petri dish. P. annandalei predation behavior was directly observed for 15 min (using a stopwatch) in five replicates for each treatment under a zoom stereomicroscope (Olympus SXZ 16). Observations were performed on a glass cavity block (3.2-cm diameter and 0.6-cm-deep petri dish) containing 5 mL of medium.

The probability of prey ingestion after an attack (PI) and probability of prey rejection after an attack (PR) were calculated using the following formulae:

The differences in the probability of each predation event were analyzed using a stepwise analysis of variance (ANOVA); probability data were arch-sine-transformed for statistical analyses.

Prey rejection as a function of feeding duration

Prey ingestion and rejection rates were observed in this experiment for differentially starved P. annandalei individuals. Female individuals were allowed to feed on ciliates for various durations prior to initiating the experiments. Experiments were conducted in a transparent glass cavity block (3.2-cm diameter and 0.6-cm-deep petri dish) containing 5 mL of medium. Thereafter, 20 cells of Euplotes sp. were introduced into the cavity block, and each ingestion and rejection event of ciliate cells was carefully recorded under a microscope for every 15-min interval.

Results

Direct microscopic observations proved that P. annandalei actively consumed Euplotes cells. First, P. annandalei used filter feeding currents to bring ciliates near its mouthparts and when ciliate prey approached an appropriate capturable distance, the copepod captured and ingested them. Images of female P. annandalei capturing cells of Euplotes sp. are shown in Figure 1.

Effects of algal diets on ciliate consumption rates

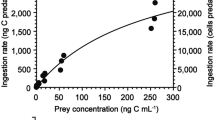

Both male and female (nonovigerous and ovigerous) P. annandalei efficiently ingested Euplotes cells (Figure 2). Gender-based differences in ciliate ingestion by P. annandalei were not significant (p > 0.37, one-way ANOVA), and 8 to 15 Euplotes cells/h were consumed. Male and female P. annandalei showed differential responses to an algal-diet presence in the medium. Neither I. galbana (a smaller alga) nor T. chui (a larger alga) alone showed any significant effect (p > 0.05, one-way ANOVA, Figure 2) on ciliate consumption by ovigerous and nonovigerous P. annandalei females. However, the presence of I. galbana elicited significantly (p = 0.018) less ciliate ingestion by P. annandalei males. Furthermore, the combination of the smaller and larger algae elicited significantly lower ciliate consumption rates (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA) by both male and female P. annandalei (Figure 2).

Feeding by P. annandalei as affected by satiation time and satiation level

P. annandalei females efficiently cleared Euplotes cells for 105 min in a food-rich environment. Although copepods were kept in a food-rich environment for 225 min, the number of cells consumed did not significantly differ from 105 to 225 min. Therefore, the consumption of ciliates by female P. annandalei reached a satiation level at 105 min, after ingesting a total of 25.5 ± 2 Euplotes cells (Figure 3).

Predation efficiency (microscopic observations) as a function of hunger level

Through repeated observations using a zoom stereomicroscope, P. annandalei was shown to react to ciliates that approached its visual horizon, outside of which no reaction was observed independently of the distance from the first antennae. P. annandalei created feeding currents that carried prey towards its capture zone, bringing ciliates near its antennules. Prey handling, ingestion, and rejection were observed. Prey capture events were analyzed using our behavioral observations.

Prey searching and handling times

Prey searching times were significantly influenced by the hunger state of the predator. The hunger level exerted a significant effect (p = 0.002, one-way ANOVA, Figure 4A) on P. annandalei males searching for prey, but was not significant (p = 0.35, one-way ANOVA) in female calanoids (Figure 4A). Well-fed males required a significantly longer duration (p < 0.05) to search for prey compared to their poorly fed and starved counterparts. However, prey searching times did not significantly differ between poorly fed and starved males. Prey searching times were significantly longer (p < 0.05, Student's t test) in well-fed and poorly fed P. annandalei males compared to female calanoids (Figure 4A). Hunger level related differences in prey handling times did not significantly differ (p = 0.152; Figure 4B) in female P. annandalei, but significantly differed (p = 0.005, one-way ANOVA; Figure 4B) in males. The prey handling time for starved males was significantly lower (p < 0.001) than those of well-fed and poorly fed male P. annandalei. Furthermore, prey handling times were significantly longer (p < 0.05) in males than females.

Prey searching and handling times by males and females of P. annandalei . Prey searching time (A) and handling time (B) (seconds; mean ± SE) by males and females of P. annandalei as a function of the hunger level. Significant differences are indicated by letters within a gender and by asterisks between genders.

Post-attack probabilities of ingestion and rejection

Probabilities of cell ingestion significantly increased (p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA; Figure 5A) with increasing hunger levels in both male and female P. annandalei. Prey ingestion probabilities were significantly higher (p < 0.05, Student's t test; Figure 5A) in poorly fed and starved females compared to male calanoids. Differences in prey ingestion probabilities were not significant (p = 0.117, Student's t test) between genders for well-fed P. annandalei.

Post-attack probabilities of Euplotes cell ingestion and rejection. Post-attack probabilities of Euplotes cell ingestion (A) and rejection (B) (mean ± SE) by males and females of P. annandalei with an increasing hunger level (well fed, poorly fed and starved). Significant differences are indicated by letters within a gender and by asterisks between genders.

Prey rejection probabilities were inversely proportional to the hunger level of P. annandalei. Prey rejection frequencies were significantly higher in poorly fed and starved male calanoids than in the same female calanoids (p < 0.05), but there was no significant difference for well-fed calanoids (p = 0.82, Student's t test; Figure 5B). The highest prey rejection probabilities were recorded (p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA; Figure 5B) for both female and male P. annandalei that were starved for the longest duration (i.e., at the maximum hunger level).

Furthermore, prey ingestion and rejection were inversely correlated with the feeding duration in female P. annandalei. The number of rejected ciliate cells was significantly higher (p = 0.003, R 2 = 0.91), and cell ingestion was significantly lower (p = 0.001, R 2 = 0.98; Figure 6) at the longest feeding duration in female calanoids.

Discussion

Visual behavioral studies in laboratories provide reliable quantitative information regarding the sequence of feeding steps, such as prey searching, handling times, attack, capture, ingestion, and rejection by a predator (Trager et al. 1990; Awasthi et al. 2012a), efficiency of a predator in capturing prey (Hwang and Strickler 2001; Rao and Kumar 2002; Dhanker et al. 2012), and antipredator (escape) behavior by prey (Awasthi et al. 2012b). Dhanker et al. (2012) indicated that P. annandalei fed efficiently on the rotifer B. rotundiformis Tschugunoff, 1921 even in the presence of alternate algal food. This study further elucidated the predatory behavior of P. annandalei on a heterotrophic ciliate. The ciliate genus used in this study is widely distributed (cosmopolitan) such as several other microzooplankton. The contribution of ciliates to food sources of copepods is commonly known for freshwater (Wickham 1995; Reiss and Schmid-Araya 2011; Kamjunke et al. 2012), estuarine (Wiadnyana and Rassoulzadegan 1989; Vincent and Hartmann 2001), and marine ecosystems (Levinsen et al. 2000; Calbert and Saiz 2005). A mixture of ciliates and phytoplankton provided different results from that of either prey alone (Kumar 2003). Numerous studies showed higher clearances of ciliates over algal food, but several showed equal ingestion rates. Conversely, lower ciliate ingestion rates were verified (see reviews by Stoecker and Capuzzo 1990; Sanders and Wickham 1993).

In this study, P. annandalei efficiently ingested Euplotes cells, and Euplotes cell consumption was not affected by the mono-algal diets. The presence of a pluri-algal diet significantly affected ciliate consumption by male and female P. annandalei. This study concluded that P. annandalei exhibited a behavioral preference for ciliated protists. It should be noted that marine calanoids require ω3-PUFAs in their food for growth and development (Brett and Müller-Navarr 1997), and hence any food containing ω3-PUFAs is considered a nutritionally enriched diet for copepods. The present study did not discuss the nutritional contents of ciliate protists for P. annandalei. The ciliate prey tested in this study, Euplotes sp. (Zhukova and Kharlamenko 1999), was reported to possess the ability to synthesize highly unsaturated fatty acids (HUFAs) (Mieczan 2012). Moreover, Euplotes sp. is the only ciliate known to produce a sterol (Harvey and McManus 1991). Sterols are indispensable for maintaining cell membrane fluidity (Ourisson et al. 1987); thus, they occur in nearly all higher organisms. Although P. annandalei produced eggs on microalgal diets in culture conditions, we presumed that adult P. annandalei would be able to produce more eggs on a mixed diet of ciliate and algae than solely on a pure algal diet.

The predatory feeding behavior of P. annandalei was recently experimentally described (Dhanker et al. 2012), and this is the first study to demonstrate P. annandalei predation on a ciliated protist. In aquaculture practice, numerous species of the genus Pseudodiaptomus have been cultured on algae alone (Pagano et al. 2003; Puello-Cruz et al. 2009; Ohs et al. 2010). This suggests that truly herbivorous or truly carnivorous taxa are rare. Our observations suggest that adult P. annandalei can consume heterotrophic ciliates even in the presence of algal food. Calanoid copepods are generally more effective in controlling ciliate communities than cyclopoids (Burns and Gilbert 1993; Wickham 1995). Even smaller diaptomids have the potential to control both the biomass and species structure of ciliate communities (Burns and Gilbert 1993). The omnivorous calanoid, Acartia, had a significantly higher clearance rate of ciliate prey than of phytoplankton (Gifford and Dagg 1988). Similarly, in the Bay of Biscay, Temora longicornis and Centropages chierchiae were found to ingest ciliates at higher rates rather than chlorophyll pigments (Vincent and Hartmann 2001).

Two algal species were used as alternative food in this study (Table 1). The microalga I. galbana is at the smaller size limit of the dietary niche width for calanoid copepods. Copepods generally avoid food of <5 μm in size regardless of their body size (Pagano et al. 1999 2003; Fileman et al. 2007; Jang et al. 2010). Larger protozoa (>10 μm in length or width) are ingested at high rates rather than phytoplankton by various species of calanoid copepods in various stages (Ohman and Runge 1994). This study demonstrated that P. annandalei (a) exerted strong predation pressure on ciliated protists and (b) actively fed on ciliates in the presence of either smaller alga I. galbana or larger alga T. chui, but the feeding activity was differentially influenced by the algal species and their combination.

In this study, longer searching and handling times, and lower ingestion and higher rejection rates of ciliates in male P. annandalei, suggest that males are less efficient predators compared to their female counterparts. Behaviors of ciliates belonging to the genus Euplotes following exposure to predator cues were extensively described (Kusch 1993; Altwegg et al. 2004; Duquette et al. 2005). Euplotes cells were observed to respond to the predatory flatworm by producing large lateral wings, a dorsal ridge, and ventral projections, as well as significantly increasing their maximum body width (Wiackowski and Staronska 1999; Altwegg et al. 2004). These morphological changes lead to a significantly reduced probability of ingestion by predators (Kuhlmann and Heckmann 1994). Moreover, changes in Euplotes behaviors following exposure to amoeboid predators were previously documented (Kusch 1993). Predator encounters are associated with a prey's movements, indicating that a reduced velocity during foraging may be an adaptive measure because it lowers the chances of encountering predators. Therefore, observing each event of prey capture and the probability of successive events during prey capture is important in understanding prey capture success.

The probability of each event following preceding events during predation in copepods is variable and dependent on biotic and abiotic factors. Copepods in nature regularly experience hunger because of long-term seasonal changes in vertical migrations of the food supply (Runge 1980) and/or prey patchiness (Dagg 1977). Hunger levels have important roles in feeding behaviors of copepods (Runge 1980; Williamson 1980; Asaeda et al. 2001). The hunger level of a copepod may increase the feeding current speed and decrease the duration for completing several or all steps of the predation sequence. Other factors that influence predation interactions between copepods and their prey are age, size, sex, and reproductive stage of the predator (Yen 1983; Kumar 2003; Dhanker et al. 2012). Prey ingestion rates were inversely proportional to gut fullness of the predator as shown in the present study. A previous study showed that P. annandalei became more selective when feeding on rotifer prey following a certain duration of feeding (Dhanker et al. 2012). In contrast, the hunger level is an important promoter of prey ingestion; animals do not show feeding stimuli or become more selective when satiated (Croy and Hughes 1991; Salvanes and Hart 1998). Starved calanoids are more active in generating feeding currents compared to satiated individuals. The gut content affects prey ingestion probabilities and handling times in P. annandalei (Dhanker et al. 2012). Prey ingestion rates and gut fullness generally show an inverse relationship (Croy and Hughes 1991). In this study, P. annandalei at near satiation showed a tendency to reject ciliates following prey entrainment in the feeding appendages. Conversely, the rejection of an entrained cell was minimal when copepods were at their maximum hunger stage, which may be attributed to the number of ciliate cells in the gut. When satiated, P. annandalei did not show active swimming towards prey and frequently rejected prey entrained in its feeding appendages. Price et al. (1983) reported that calanoid copepods used their second maxillae for the reverse motion of rejecting a prey following capture. Prey rejection by copepods may be due to gut fullness, prey size, unpalatability of the prey, and longer handling times (Williamson 1980 1987).

Previous studies showed that copepods initially entrain their prey in a feeding current and attack the prey after detection (Svensen and Kiørboe 2000 Jakobsen et al. 2005). The feeding current beats the bands of the microzooplankton prey (Conover 1981). We observed that P. annandalei began moving slowly towards a ciliate until it was in close proximity and then used feeding currents to capture the prey in its feeding appendages. Different feeding modes in P. annandalei may be attributed to the differential size and mobility of ciliates compared to rotifers.

The prey searching time of organisms depends on the hunger level of the predator (Williamson 1980) and other factors such as swimming speed, and size and abundance of prey and predators (Mazzocchi and Paffenhöfer 1999; Rao and Kumar 2002; Uttieri et al. 2008; Wu et al. 2010; Mahjoub et al. 2011; Kumar et al. 2012). In the present study, gut fullness did not have a significant effect on handling times or prey detection in female P. annandalei, but males were affected by hunger levels. Searching and handling times were higher in male P. annandalei with increased hunger levels than in females. We discovered that starved calanoids were more active in searching for ciliates compared to satiated ones. This study concluded that prey detection by P. annandalei is influenced by the hunger level, sex, and distance between the prey and predator. Several studies demonstrated that the hunger state of copepods has a significant effect on ciliate consumption (Runge 1980; Jonsson and Tiselius 1990). Runge (1980) demonstrated that grazing rates of starved Calanus pacificus increased 1.5 ~ 3-fold compared to well-fed copepods. In our earlier study (Dhanker et al. 2012), prey handling times directly affected rotifer ingestion probabilities in P. annandalei with increasing hunger levels in the predator. Ciliate ingestion probabilities showed a direct relationship with the hunger level of P. annandalei regardless of sex, which is a similar result as in the present study. A minimum number of ciliate cells were rejected at the highest hunger level in male and female P. annandalei.

Conclusions

The perennial abundance in natural habitats and efficiency of utilizing food from autotrophic and heterotrophic food suggest that feeding habits of P. annandalei are highly adaptive and it can derive nutrients during periods of low primary production. Moreover, single algal species did not alter ciliate ingestion rates of P. annandalei, which reflects its adaptive nature of feeding. Copepods are unable to synthesize HUFAs, which are essential for their growth and reproduction. Phytoplankton feeders must obtain these essential HUFAs in their diet (Støttrup and Jensen 1990). T. chui is a moderate source of HUFAs, and Isochrysis is rich (9% total fatty acids) in DHA but has scant EPA (Dunstan et al. 1993). Therefore, either alga is not nutritionally sufficient for the copepod, but a combination of the two species is suitable. This limits the chance of nutritional deficiencies during copepod development and reduces the risk of food shortages that may occur from the failure of algal culture. The present study points to the role of P. annandalei in forming a link between the microbial loop and classical food chain, which expedites the flow of bacterial carbon to higher trophic levels in estuarine ecosystems (e.g., the Danshui estuary; Hwang et al. 2010). Laboratory experiments such as those in this study are important for estimating ingestion rates at specific prey concentrations and determining what factors influence those rates. However, better estimates of natural microzooplankton concentrations and the size and permanence of patches are necessary before such studies can be used to quantitatively measure mortality from predation in nature.

References

Adriana JV, Chu FLE, Tang KW: Trophic modification of essential fatty acids by heterotrophic protists and its effects on the fatty acid composition of the copepod Acartia tonsa . Mar Biol 2006, 148: 779–788. 10.1007/s00227-005-0123-1

Altwegg R, Marchinko KB, Duquette SL, Anholt BR: Dynamics of an inducible defence in the protist Euplotes . Arch Hydrobiologia 2004, 160: 431–446. 10.1127/0003-9136/2004/0160-0431

Asaeda T, Priyadarshana T, Manatunge J: Effects of satiation on feeding and swimming behavior of planktivores. Hydrobiologia 2001, 443: 147–157. 10.1023/A:1017560524056

Atkinson A: Subarctic copepods in an oceanic, low chlorophyll environment: ciliate predation, food selectivity and impact on prey populations. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 1996, 130: 85–96.

Awasthi AK, Wu CH, Tsai KH, King CC, Hwang JS: How does ambush predatory copepod Megacyclops formosanus (Harada 1931) capture mosquito larvae, Aedes aegypti ? Zool Stud 2012a, 51: 927–936.

Awasthi AK, Wu CH, Hwang JS: Diving as an antipredator behavior in mosquito pupae. Zool Stud 2012b, 51: 1225–1234.

Beyrend-Dur D, Kumar R, Rao TR, Souissi S, Cheng SH, Hwang JS: Demographic parameters of adults of Pseudodiaptomus annandalei (Copepoda: Calanoida): temperature-salinity and generation effects. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 2011, 404: 1–14. 10.1016/j.jembe.2011.04.012

Brett MT, Müller-Navarr DC: The role of highly unsaturated fatty acids in aquatic food web processes. Freshw Biol 1997, 38: 483–499. 10.1046/j.1365-2427.1997.00220.x

Broglio E, Jonasdottir SH, Calbet A, Jakobsen HH, Saiz E: Effect of heterotrophic versus autotrophic food on feeding and reproduction of the calanoid copepod Acartia tonsa : relationship with prey fatty acid composition. Aquat Microb Ecol 2003, 31: 267–278.

Burns CW, Gilbert JJ: Predation on ciliates by freshwater calanoid copepods: rates of predation and relative vulnerability of prey. Freshw Biol 1993, 30: 377–393. 10.1111/j.1365-2427.1993.tb00822.x

Calbert A, Saiz E: The ciliate-copepod link in marine ecosystems. Aquat Microb Ecol 2005, 38: 157–167.

Celino FT, Hilomen-Garcia GV, Del Norte-Campos AGC: Feeding selectivity of the seahorse, Hippocampus kuda (Bleeker), juveniles under laboratory conditions. Aquacult Res 2012, 43: 1804–1815. 10.1111/j.1365-2109.2011.02988.x

Chen Q, Sheng J, Lin Q, Gao Y, Lv J: Effect of salinity on reproduction and survival of the copepod Pseudodiaptomus annandalei Sewell, 1919. Aquaculture 2006, 258: 575–582. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.04.032

Cheng SH, Kâ S, Kumar R, Kuo SC, Hwang JS: Effects of salinity, food level, and the presence of microcrustacean zooplankters on the population dynamics of rotifer Brachionus rotundiformis . Hydrobiologia 2011, 666: 289–299. 10.1007/s10750-011-0615-6

Conover RJ: Nutritional strategies for feeding on small suspended particles. In Analysis of marine ecosystems. Edited by: Longhurst A. Academic, New York; 1981:363–395.

Croy MI, Hughes RN: The influence of hunger on feeding behaviour and on the acquisition of learned foraging skills by the fifteen spined stickleback, Spinachia spinachia L. Anim Behav 1991, 41: 161–170. 10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80511-1

Dagg MJ: Some effects of patchy food environments on copepods. Limnol Oceanogr 1977, 22: 99–107. 10.4319/lo.1977.22.1.0099

Dahms HU, Tseng LC, Hsiao SH, Chen QC, Kim BR, Hwang JS: Biodiversity of planktonic copepods in the Lanyang River (northeastern Taiwan), a typical watershed of Oceania. Zool Stud 2012, 51: 160–174.

Dhanker R, Kumar R, Hwang JS: Predation by Pseudodiaptomus annandalei (Copepoda: Calanoida) on rotifer prey: size selection, egg predation and effect of algal diet. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 2012, 414–415: 44–53.

Doi M, Toledo JD, Golez MSN: Preliminary investigation of feeding performance of larvae of early red-spotted grouper, Epinephelus coioides , reared with mixed zooplankton. Hydrobiologia 1997, 358: 259–263. 10.1023/A:1003193121532

Dunstan GA, Volkman JK, Barrett SM, Garland CD: Changes in the lipid composition and maximization of the polyunsaturated fatty acid content of three microalgae grown in mass culture. J Appl Phycol 1993, 5: 71–83. 10.1007/BF02182424

Duquette SL, Altwegg R, Anholt BR: Factors affecting the expression of inducible defences in Euplotes : genotype, predator density and experience. Funct Ecol 2005, 19: 648–655. 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2005.01013.x

Dur G, Souissi S, Schmitt FG, Cheng SH, Hwang JS: Sex ratio and mating behavior in the calanoid copepod Pseudodiaptomus annandalei . Zool Stud 2012, 51: 589–597.

Ederington MC, McManus GB, Harvey HR: Trophic transfer of fatty acids, sterols and a triterpenoid alcohol between bacteria, a ciliate, and the copepod Acartia tonsa . Limnol Oceanogr 1995, 40: 860–867. 10.4319/lo.1995.40.5.0860

Fileman E, Smith T, Harris R: Grazing by Calanus helgolandicus and Para-Pseudocalanus spp. on phytoplankton and protozooplankton during the spring bloom in the Celtic Sea. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 2007, 348: 70–84. 10.1016/j.jembe.2007.04.003

Fileman E, Petropavlovsky A, Harris R: Grazing by the copepods Calanus helgolandicus and Acartia clausi on the protozooplankton community at station L4 in the western English Channel. J Plankt Res 2010, 32: 709–724. 10.1093/plankt/fbp142

Gifford DJ: The protozoan-metazoan trophic link in pelagic ecosystems. J Protozool 1991, 38: 81–86. 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1991.tb04806.x

Gifford DJ, Dagg MJ: Feeding of the estuarine copepod Acartia tonsa Dana: carnivory vs. herbivory in natural microplankton assemblages. Bull Mar Sci 1988, 43: 458–468.

Gifford DJ, Dagg MJ: The microzooplankton-mesozooplankton link: consumption of planktonic protozoa by the calanoid copepods Acartia tonsa Dana and Neocalanus plumchrus Murukawa. Mar. Microb. Food Webs 1991, 5: 161–177.

Hagiwara A, Gallardo WG, Assavaaree M, Kotani T, De Araujo AB: Live food production in Japan: recent progress and future aspects. Aquaculture 2001, 200: 111–127. 10.1016/S0044-8486(01)00696-2

Hansen PJ: Prey size selection, feeding rates and growth dynamics of heterotrophic dinoflagellates with special emphasis on Gyrodinium spirale . Mar Biol 1992, 114: 327–334. 10.1007/BF00349535

Harvey RH, McManus GB: Marine ciliates as a widespread source of tetrahymanol and hopan-3β-ol in sediments. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 1991, 55: 3387–3390. 10.1016/0016-7037(91)90496-R

Huo YZ, Wang SW, Sun S, Li CL, Liu MT: Feeding and egg production of the planktonic copepod Calanus sinicus in spring and autumn in the Yellow Sea. China J Plankton Res 2008, 30: 723–734. 10.1093/plankt/fbn034

Hwang JS, Strickler JR: Can copepods differentiate prey from predator hydromechanically? Zool Stud 2001, 40: 1–6.

Hwang JS, Kumar R, Hsieh CW, Kuo AY, Souissi S, Hsu MH, Wu JT, Liu WC, Wang CF, Chen QC: Patterns of zooplankton distribution along marine, estuarine and riverine portion of Danshuei ecosystem, northern Taiwan. Zool Stud 2010, 49: 335–352.

Ismar SMH, Hansen T, Sommer U: Effect of food concentration and type of diet on Acartia survival and naupliar development. Mar Biol 2008, 154: 335–343. 10.1007/s00227-008-0928-9

Jakobsen HH, Halvorsen E, Hansen BW, Visser AW: Effects of prey motility and concentration on feeding in Acartia tonsa and Temora longicornis : the importance of feeding modes. J Plankton Res 2005, 8: 775–785.

Jang MC, Shin K, Lee T, Noh I: Feeding selectivity of calanoid copepods on phytoplankton in Jangmok Bay, South Coast of Korea. Ocean Sci J 2010, 45: 101–111. 10.1007/s12601-010-0009-0

Jonsson PR, Tiselius P: Feeding behavior, prey predation and capture efficiency of the copepod Acartia tonsa feeding on planktonic ciliates. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 1990, 60: 35–44.

Kâ S, Hwang JS: Mesozooplankton distribution and composition on the northeastern coast of Taiwan during autumn: effects of the Kuroshio Current and hydrothermal vents. Zool Stud 2011, 50: 155–163.

Kamjunke N, Kramps M, Chavez S, Woelfl S: Consumption of large, Chlorella -bearing ciliates ( Stentor ) by Mesocyclops araucanus in North Patagonian lakes. J Plankton Res 2012, 34: 922–927. 10.1093/plankt/fbs051

Klein Breteler WCM, Schogt N, Baas M, Schouten S, Kraay GW: Trophic upgrading of food quality by protozoans enhancing copepod growth: role of essential lipids. Mar Biol 1999, 135: 191–198. 10.1007/s002270050616

Kuhlmann HW, Heckmann K: Predation risk of typical ovoid and ‘winged’ morphs of Euplotes (Protozoa, Ciliophora). Hydrobiologia 1994, 284: 219–227. 10.1007/BF00006691

Kumar R: Effect of different food types on the postembryonic developmental rates and demographic parameters of Phyllodiaptomus blanci (Copepoda; Calanoida). Arch Hydrobiologia 2003, 157: 351–377. 10.1127/0003-9136/2003/0157-0351

Kumar R, Rao TR: Demographic responses of adult Mesocyclops thermocyclopoides (Copepoda, Cyclopoida) to different plant and animal diets. Freshw Biol 1999, 42: 487–501. 10.1046/j.1365-2427.1999.00485.x

Kumar R, Rao TR: Effect of algal food on animal prey consumption rates in the omnivorous copepod. Mesocyclops thermocyclopoides. Int Rev Hydrobiologia 1999, 84: 419–426.

Kumar R, Souissi S, Hwang JS: Vulnerability of carp larvae to copepod predation as a function of larval age and body length. Aquaculture 2012, 338–341: 274–283.

Küppersm GC, Claps MC: Spatiotemporal variations in abundance and biomass of planktonic ciliates related to environmental variables in a temporal pond. Argentina Zool Stud 2012, 51: 298–313.

Kusch J: Behavioural and morphological changes in ciliates induced by the predator Amoeba proteus . Oecologia 1993, 96: 354–359. 10.1007/BF00317505

Landry MR, Gifford DJ, Kirchman DL, Wheeler PA, Monger BC: Direct and indirect effects of grazing by Neocalanus plumchrus on planktonic community dynamics in the Subarctic Pacific. Prog Oceanogr 1993, 32: 239–258. 10.1016/0079-6611(93)90016-7

Lee CH, Dahms HU, Cheng SH, Souissi S, Schmitt FG, Kumar R, Hwang JS: Predation on Pseudodiaptomus annandalei (Copepoda: Calanoida) by the grouper fish larvae Epinephelus coioides under different hydrodynamic conditions. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 2010, 393: 17–22. 10.1016/j.jembe.2010.06.005

Levinsen H, Turner TJ, Nielsen TG, Hansen BW: On the trophic coupling between protists and copepods in arctic marine ecosystems. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 2000, 204: 65–77.

Liao IC, Su HM, Chang EY: Techniques in finfish larviculture in Taiwan. Aquaculture 2001, 200: 1–31. 10.1016/S0044-8486(01)00692-5

Loder MGC, Meunier C, Wiltshire KH, Boersma M, Aberle N: The role of ciliates, heterotrophic dinoflagellates and copepods in structuring spring plankton communities at Helgoland Roads, North Sea. Mar Biol 2011, 158: 1551–1580. 10.1007/s00227-011-1670-2

Madhupratap M: Status and strategy of zooplankton of tropical Indian estuaries: a review. Bull Plankton Soc Japan 1987, 34: 65–81.

Mahjoub MS, Souissi S, Michalec FG, Schmit FG, Hwang JS: Swimming kinematics of Eurytemora affinis (Copepoda, Calanoida) reproductive stages and differential vulnerability to predation of larval Dicentrarchus labrax (Teleostei, Perciformes). J Plankton Res 2011, 33: 1095–1103. 10.1093/plankt/fbr013

Mazzocchi MG, Paffenhöfer GA: Swimming and feeding behaviour of the planktonic copepod Clausocalanus furcatus . J Plankton Res 1999, 21: 1501–1518. 10.1093/plankt/21.8.1501

Mieczan T: Distributions of testate amoebae and ciliates in different types of peatlands and their contributions to the nutrient supply. Zool Stud 2012, 51: 18–26.

Ohman MD, Runge JA: Sustained fecundity when phytoplankton resources are in short supply: omnivory by Calanus finmarchicus in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Limnol Oceanogr 1994, 39: 21–36. 10.4319/lo.1994.39.1.0021

Ohs CL, Chang KL, Grabe SW, DiMaggio MA, Stenn E: Evaluation of dietary microalgae for culture of the calanoid copepod Pseudodiaptomus pelagicus . Aquaculture 2010, 307: 225–232. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2010.07.016

Ourisson G, Rohmer M, Poralla K: Prokaryotic hopanoids and other polyterpenoid sterol surrogates. Annu Rev Microbiol 1987, 41: 301–333. 10.1146/annurev.mi.41.100187.001505

Pagano M, Saint-Jean L, Arfi R, Bouvy M, Guiral D: Zooplankton food limitation and grazing impact in a eutrophic brackish-water tropical pond (Côte d'Ivoire, West Africa). Hydrobiologia 1999, 390: 83–98.

Pagano M, Saint-Jean L, Arfi R, Bouvy M: Feeding of Acartia clausi and Pseudodiaptomus hessei (Copepoda: Calanoida) on natural particles in a tropical lagoon (Côte d'Ivoire). Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 2003, 56: 433–445. 10.1016/S0272-7714(02)00193-2

Price HJ, Paffenhofer GA, Strickler JR: Modes of cell capture in calanoid copepods. Limnol Oceanogr 1983, 28: 116–123. 10.4319/lo.1983.28.1.0116

Puello-Cruz AC, Mezo-Villalobos S, Gonzalez-Rodriguez B, Voltolina D: Culture of the calanoid copepod Pseudodiaptomus euryhalinus (Johnson 1939) with different microalgal diets. Aquaculture 2009, 290: 217–219.

Rao TR, Kumar R: Patterns of prey selectivity in the cyclopoid copepod, Mesocyclops thermocyclopoides . Aquat Ecol 2002, 36: 411–424. 10.1023/A:1016509016852

Reiss J, Schmid-Araya JM: Feeding response of a benthic copepod to ciliate prey type, prey concentration and habitat complexity. Freshw Biol 2011, 56: 1519–1530. 10.1111/j.1365-2427.2011.02590.x

Runge JA: Effects of hunger and season on the feeding behavior of Calanus pacificus . Limnol Oceanogr 1980, 25: 134–145. 10.4319/lo.1980.25.1.0134

Salvanes AV, Hart PJB: Individual variability in state dependent feeding behavior in three-spined sticklebacks. Anim Behav 1998, 55: 1349–1359. 10.1006/anbe.1997.0707

Sanders RW, Wickham SA: Planktonic protozoa and metazoa: predation, food quality and population control. Mar. Microb. Food Webs 1993, 7: 197–223.

Sherr EB, Sherr BF: Heterotrophic dinoflagellates: a significant component of microzooplankton biomass and major grazers of diatoms in the sea. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 2007, 352: 187–197.

Stoecker DK, Capuzzo JM: Predation on protozoa: its importance to zooplankton. J Plankton Res 1990, 12: 891–908. 10.1093/plankt/12.5.891

Støttrup JG, Jensen J: Influence of algal diet on feeding and egg-production of the calanoid copepod Acartia tonsa Dana. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 1990, 141: 87–103. 10.1016/0022-0981(90)90216-Y

Sul DG, Erwin JA: The membrane lipids of the marine ciliated protozoan Parauronema acutum . Biochim Biophys Acta 1997, 1345: 162–171. 10.1016/S0005-2760(96)00172-5

Svensen C, Kiørboe T: Remote prey detection in Oithona similis : hydromechanical versus chemical cues. J Plankton Res 2000, 22: 1155–1166. 10.1093/plankt/22.6.1155

Tang KW, Taal M: Trophic modification of food quality by heterotrophic protists: species-specific effects on copepod egg production and egg hatching. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 2005, 318: 85–98. 10.1016/j.jembe.2004.12.004

Tiselius P: Contribution of aloricate ciliates to the diet of Acartia clausi and Centropages hamatus in coastal waters. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 1989, 56: 49–56.

Trager GC, Hwang JS, Strickler JR: Barnacle suspension-feeding in variable flow. Mar Biol 1990, 105: 117–127. 10.1007/BF01344277

Tseng LC, Dahms HU, Chen QC, Hwang JS: Copepod feeding study in the upper layer of the tropical South China Sea. Helg Mar Res 2009, 63: 327–337. 10.1007/s10152-009-0162-y

Turner JT: The importance of small planktonic copepods and their roles in pelagic marine food webs. Zool Stud 2004, 43: 255–266.

Uttieri M, Paffenhőfer GA, Mazzocchi MG: Prey capture in Clausocalanus furcatus (Copepoda: Calanoida). The role of swimming behaviour. Mar Biol 2008, 153: 925–935. 10.1007/s00227-007-0864-0

Vadstein O, Stibor H, Lippert B, Roederer W, Sundt-Hansen L, Olsen Y: Moderate increase in the biomass of omnivorous copepods may ease grazing control of planktonic algae. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 2004, 270: 199–207.

Vincent D, Hartmann HJ: Contribution of ciliated microprotozoans and dinoflagellates to the diet of three copepod species in the Bay of Biscay. Hydrobiologia 2001, 443: 193–204. 10.1023/A:1017502813154

Walne PR: Studies on the food value of nineteen genera of algae to juvenile bivalves of the genera Ostrea , Crassostrea , Mercenaria and Mytilus . Fish Invest 1970, 26: 1–62.

Wiackowski K, Staronska A: The effect of predator and prey density on the induced defence of a ciliate. Funct Ecol 1999, 13: 59–65. 10.1046/j.1365-2435.1999.00282.x

Wiadnyana NN, Rassoulzadegan F: Selective feeding of Acartia clausi and Centropages typicus on microzooplankton. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 1989, 53: 37–45.

Wickham SA: Cyclops predation on ciliates: species specific differences and functional responses. J Plankton Res 1995, 17: 1633–1646. 10.1093/plankt/17.8.1633

Williamson CE: The predatory behavior of Mesocyclops edax : predator preferences, prey defenses, and starvation-induced changes. Limnol Oceanogr 1980, 25: 903–909.

Williamson CE: Predator–prey interactions between omnivorous diaptomid copepods and rotifers: the role of prey morphology and behavior. Limnol Oceanogr 1987, 32: 167–177. 10.4319/lo.1987.32.1.0167

Wu CH, Dahms HU, Buskey EJ, Strickler JR, Hwang JS: Behavioral interactions of the copepod Temora turbinata with potential ciliate prey. Zool Stud 2010, 49: 157–168.

Yen J: Effects of the prey concentration, prey size, predator life stage, predator starvation and season on predation rates of the carnivorous copepod Euchaeta elongata . Mar Biol 1983, 75: 69–77. 10.1007/BF00392632

Zhukova NV, Kharlamenko VI: Sources of essential fatty acids in the marine microbial loop. Aquat Microb Ecol 1999, 17: 153–157.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the National Science Council of Taiwan (grant nos. NSC98-2621-B-019-001-MY3, NSC101-2621-B-019-002, and NSC102-2923-B-019-001-MY3) for supporting this research. We thank two anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions that substantially improved the quality of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JSH wrote the proposal and ran the lab. JSH and RD designed the study. RD carried out the studies as well as performed the statistical analysis with LCT. RD made figures, tables and wrote the manuscript. JSH commented and revised on the manuscript. RD, RK and JSH finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Dhanker, R., Kumar, R., Tseng, LC. et al. Ciliate (Euplotes sp.) predation by Pseudodiaptomus annandalei (Copepoda: Calanoida) and the effects of mono-algal and pluri-algal diets. Zool. Stud. 52, 34 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1810-522X-52-34

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1810-522X-52-34