Abstract

Background

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin and TDP-43 positive neuronal inclusions represents a novel entity (FTLD-TDP) that may be associated with motor neuron disease (FTLD-MND); involvement of extrapyramidal and other systems has also been reported.

Case presentation

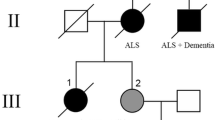

We present three cases with similar clinical symptoms, including Parkinsonism, supranuclear gaze palsy, visuospatial impairment and a behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia, associated with either clinically possible or definite MND. Neuropathological examination revealed hallmarks of FTLD-TDP with major involvement of subcortical and, in particular, mesencephalic structures. These cases differed in onset and progression of clinical manifestations as well as distribution of histopathological changes in the brain and spinal cord. Two cases were sporadic, whereas the third case had a pathological variation in the progranulin gene 102 delC.

Conclusions

Association of a "progressive supranuclear palsy-like" syndrome with marked visuospatial impairment, motor neuron disease and early behavioral disturbances may represent a clinically distinct phenotype of FTLD-TDP. Our observations further support the concept that TDP-43 proteinopathies represent a spectrum of disorders, where preferential localization of pathogenetic inclusions and neuronal cell loss defines clinical phenotypes ranging from frontotemporal dementia with or without motor neuron disease, to corticobasal syndrome and to a progressive supranuclear palsy-like syndrome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) caused by frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin and transactive response DNA binding protein 43 (TDP-43) positive inclusions (FTLD-TDP) represent two different manifestations of the same neurodegenerative disease [1]. Distribution of TDP-43 related neuropathological changes include various anatomical regions with differences in the predominance of lesions, suggesting that TDP-43 proteinopathies reflect the spectrum of a multisystem disorder [2–4]. Mutations in the progranulin (PGRN) gene, located on chromosome 17, have been linked to inherited forms associated with neuropathologically detectable TDP-43 proteinopathy and with different clinical symptomatology [5–7]. Moreover, an increasing number of variations within PGRN have been described http://www.molgen.ua.ac.be/FTDMutations.

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is characterized by early gait disturbances and falls, axial rigidity, vertical gaze palsy, and subcortical dementia [8]. PSP is considered to be a tauopathy; however, a PSP-like syndrome has been associated with ubiquitin-only-immunoreactive neuronal changes [9], and thus could be part of the clinical picture of "ALS-plus syndrome" caused by TDP-43 proteinopathy [2, 10]. Moreover, FTLD-TDP may have a presentation similar to corticobasal degeneration [11] indicating that these disorders can present with a spectrum of clinical phenotypes that also overlaps other neurodegenerative disorders.

Here we describe three cases, including one with a variation in the PGRN gene, with a clinical presentation reminiscent of PSP ("PSP-like syndrome") in patients with FTLD-TDP (with or without MND) that supports the notion of a further, clinically distinguishable, phenotype within the spectrum of TDP-43 proteinopathies.

Clinical and neuropathological data were obtained from three patients followed in the Departments of Neurology, Thomayer Teaching Hospital and Motol Teaching Hospital, Prague, CZ. Patients were assessed using standardized diagnostic tools: magnetic resonance (MRI), electromyography (EMG), routine blood analysis, and neuropsychological assessments. All procedures were explained to the patients and their caregivers, and informed consent was obtained in all cases. All data were analyzed with respect for patient privacy and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Thomayer Teaching Hospital.

During autopsy, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded blocks were obtained from the following regions: frontal, cingulate, temporal, parietal and occipital cortices and subcortical white matter, basal ganglia, thalamus, hippocampus, cerebellum, and brainstem. For immunohistochemistry 5 μm thick sections of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue were used with primary antibodies against the following antigens: anti-tau AT8 (1:200, Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA, pS202/pT205); ubiquitin (1:200, rabbit polyclonal; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark); protein p62 (1:4,000, guinea pig polyclonal; Progen Biotechnik GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany); protein TDP-43 (1:2.000, mouse monoclonal; Abnova Corp., Taipei, Taiwan, and 1:100, polyclonal; ProteinTech Group, Chicago, Il, USA), and phospho-TDP-43 (1:2.000, mouse monoclonal, pS409/410; Cosmo Bio Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). Semiquantitatively (0 = none; 1 = mild or few; 2 = moderate; 3 = severe or many), we scored different types of inclusions in selected brain areas.

Genomic DNA was extracted from frozen bone marrow samples (autopsy) using an isolating kit. The microtubule-associated protein (MAPT) exon 1-10, transactive response DNA binding protein (TARDBP) exons 2-6, progranulin (PGRN) exons 0-12 and respective flanking intronic regions were amplified as described previously. Products were examined using agarose gel electrophoresis, treated with ExoSAP-IT (USB, Cleveland, OH, USA), asymmetrically amplified using the DTCS Quick Start Kit (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA), and analyzed on a CEQ 8000 GeXP Genetic Analysis System (Beckman Coulter). The resulting sequences were compared to published TARDBP, MAPT, and PGRN sequences http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

Case presentation

Clinical data of the three patients are summarized in (Table 1) and the temporal evolution of symptoms in (Figure 1).

Case 1

A 70-year-old woman was referred to our department for spontaneous ptosis and slowly (five months) progressive dysarthria. In the family, apart from her two children with multiple sclerosis, there was no history of neurologic disease.

Clinical examination revealed asymmetric semiptosis, paralytic dysarthria, and mild finger (right hand) weakness. Reflexes were brisk and there was no sensory impairment. Needle EMG showed chronic regeneration and fibrillation patterns in the anterior tibialis and common finger extensor muscles. Nerve conduction studies and repetitive stimulation were normal.

Gradually, disinhibition, emotional incontinence, and spasmodic laughter developed. Five months later a neurological examination revealed blepharospasm instead of ptosis. Frontal lobe involvement (reduced verbal fluency, stereotypias, perseverative features, grasping, and apathy) became associated with impairment in visuo-spatial functions and short-term memory. Akinesia with rigidity, but without tremor, was more pronounced in axial muscles; reflexes remained brisk. There was noticeable slowing of oculomotor saccades, but without gaze palsy.

Over the next two months, the patient's condition progressively deteriorated. Extrapyramidal features and dysexecutive signs worsened, accompanied by frequent falls. The blepharospasm diminished and vertical gaze palsy developed together with eye-lid closing apraxia. Dysarthric features progressed and frontal-type gait apraxia with astasia-abasia, and incontinence appeared. A brain MRI showed marked asymmetric frontotemporal atrophy (Figure 2).

Neuropsychological assessment revealed relatively preserved episodic verbal memory and language, with conserved learning abilities (Token Test and Boston Naming Test). Executive functions were markedly impaired (Wisconsin Card Sorting Test: one category, more than 16 perseverative errors; Trail Making Test: under 10th percentile for age-matched norms). The patient failed in immediate and delayed recall of the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure; basic visuospatial skills and copying were altered to a lesser degree.

Repeated EMGs, showing signs of widespread denervation and chronic reinervation, confirmed clinically definite ALS, according to the El Escorial criteria [12]. Treatment with riluzole was started, but with little effect on disease evolution. Because of increased dysphagia and malnutrition, a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) was performed six weeks later. The patient deceased two months later from terminal bronchopneumonia.

Case 2

A 49-year-old woman, without comorbidities, was referred for cognitive and behavioral changes. Two years prior, her husband had noticed personality changes accompanied by difficulties in complex task solving (cooking, grooming). Her mood was slightly depressive and apathetic; polydipsia had also been noticed by the family (6 liters a day), but no metabolic or endocrine abnormalities were found. There was a history of dementia in the family involving a grandmother, who died at the age of 92.

Six months later we observed gait instability, swallowing difficulties and involuntary neck anteflexion. Asymmetric, left-predominant, rigidity displaying the cogwheel phenomenon and postural instability were present. Reflexes were brisk. There was no gaze palsy or fasciculations. MRI scans showed generalized atrophy with only mild, nonspecific white matter changes (Figure 2).

The neuropsychological profile was primarily dysexecutive (Frontal Assessment Battery, Digit Span, Verbal Fluency Test, and Trail Making Test under 10th percentile for age-matched norms). Language analysis showed mild alteration (Boston Naming Test 6 mistakes), visuospatial functions were impaired (Clock Drawing Test - incorrect placement and repeating of numbers, Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure with respect to copy but severely altered recall). We also noted important episodic memory impairment with reduced learning abilities sensible to cuing: The Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT): 16 words - 5 retrieved spontaneously, 11 more with cuing) and occasional confabulations. The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score was 22/30.

Vertical gaze palsy appeared 10 months later, with severe Parkinsonism and frequent falls. Levodopa (3 × 62.5 mg/day) had no effect and was stopped after 1 month because of progressive dysphagia. The MMSE dropped to 16/30 and the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scale revealed complete loss of functional capacity. Two months later, pseudobulbar signs with significant dysphagia and weight loss (15 kg in 6 months) and increasing spasticity with hyperreflexia and pyramidal signs were reported. The patient received memantine with no effect on MMSE or ADL, citalopram was added to treat signs of mild depression.

Two months later (after nearly two years of evolution), her condition deteriorated rapidly to profound dementia and severe Parkinsonism. Interosseal muscle atrophy was found, but no fasciculations; reflexes remained brisk. An EMG was scheduled but never completed. Shortly after admission there was a sudden decline in her condition, she died of bronchopneumonia and septic shock.

Case 3

A 64-year-old woman, with a family history of stroke (mother), developed gait instability, dysarthria, and mnestic difficulties over a 2 year period. Muscle rigidity appeared, falls occurred, and she became incontinent. Six months later, in another hospital, multiple system atrophy was diagnosed, and treatment with levodopa and pramipexole was started. Escitalopram was added for depression a few months later. Despite increasing doses of levodopa (up to 1000 mg daily), rigidity and akinesia worsened and the patient became wheelchair-bound. Ultimately, she was referred for diagnostic re-evaluation.

Clinical examination found psychomotor slowing, dysexecutive features with apathy, perseverations, and stereotypical behavior. Verbal fluency was decreased and there was a marked lack of insight. Speech required effort and was associated with palilalia and fluctuating dysphagia. There was no gaze paralysis, but horizontal and vertical saccades were slowed; fixation was impaired and eyelid-opening apraxia was observed. Extrapyramidal features included extensive axial rigidity with significant akinesia, but no tremor. Notable right-sided hypertonus was associated with extremity spasticity.

A MRI revealed significant atrophy with frontal and temporal predominance, and periventricular dilatation, and brain stem atrophy (Figure 2). The EMG was difficult to evaluate (extensive rigidity and lack of cooperation); there was suspicion of denervation potentials.

A cognitive assessment was incomplete due to lack of cooperation. However, we found signs of noticeably impaired executive functions and behavioral changes, visuo-constructional abilities and episodic memory were impaired with relatively conserved cueing effect (figure copying, cued recall).

Despite high-doses of L-dopa (1.5 g daily) and baclofen (150 mg daily) the condition worsened over the next months. Subcortical dementia with severely impaired fluency progressed to anarthria, and finally mutism. Massive perseveration interfered with any spontaneous movement and spasticity increased to flexion contractures. Oculomotor involvement included gaze apraxia, dissociation between impaired voluntary gaze and preserved involuntary horizontal pursuit, together with a freely elicitable oculocephalic reflex. Rigidity and akinesia remained notable in axial regions, later accompanied by dystonia and retrocollis. The patient's condition continued to decline and she deceased shortly thereafter from urosepsis.

Genetic analysis revealed a pathogenic mutation (102 delC (predicted protein: Gly35GlufsX19)) in the PGRN gene previously described [3]. We found no variations in TARDBP and MAPT genes.

Neuropathology

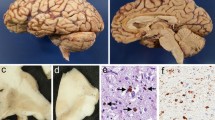

Neuronal loss and gliosis were most prominent in the mesencephalon, basal ganglia, and frontal and temporal cortices. TDP-43 and phospho-TDP-43 immunostaining revealed neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions of different types, including compact globular and dot-like structures, more pathological profiles were detected using anti-phospho-TDP-43 antibody. Neuritic profiles, positive for ubiquitin and p62 of variable intensity, were seen in different brain structures (Figure 3). Glial cytoplasmic inclusions and thread-like (phospho)-TDP-43 immunoreactivity was seen in the white matter. These cases did not strictly fit the subtyping schemes recently proposed [13]. However, due to the slight predominance of neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions in the frontal cortex and hippocampus Case 1 and 2 were reminiscent, following the proposed classification, of type 2. The long and tortuous neurites as well as neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions, seen in Case 3, made it more compatible with type 3 according to Cairns et al. [14]. Neuronal nuclear inclusions, associated with type 4, were not convincingly observed in any of cases. In addition skein-like neuronal inclusions were seen in brainstem nuclei in all cases, including substantia nigra (all), hypoglossal nucleus (Cases 1 and 2) and inferior olivary nucleus (Case 3).

Immunohistochemistry for phospho-TDP-43. Spherical, "Lewy-like" and skein-like neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions as well as diffuse granular inclusions were found in substantia nigra (case III - A), pontine base (case I - B) and in hypoglossal nucleus (case II - C); thin and long as well as globular neurites in hippocampal formation (case I - D). Scale bars = Bar graphs: 50 μm (A), 100 μm (B and D), 200 μm (C).

In summary, we found hallmarks of FTLD-MND with ubiquitin-immunoreactive neuronal changes and intracytoplasmic and neuritic TDP-43, phosphorylated TDP-43, and p62 immunopositivity (Figure 3) compatible with the diagnosis of FTLD-TDP with MND. Detailed mapping of immunohistochemical positivity in different brain areas is summarized in (Figure 4).

Conclusions

We present three autopsy proven cases of FTLD-TDP with clinical manifestation as "progressive supranuclear palsy plus" syndrome. A summary of our study observations include: (i) during the clinical course, but not as initial symptoms, all patients showed clinical hallmarks of PSP (subcortical dementia, axial predominant akinesia and rigidity, supranuclear gaze abnormalities, and frequent falls), (ii) additionally, upper and/or lower motor neuron involvement and a frontal behavioral syndrome ("ALS-plus" syndrome) were also detected, (iii) FTLD-TDP was confirmed neuropathologically in all cases, (iv) mutations in MAPT, TARDBP were not observed, while in one patient we found a PGRN mutation (Case 3), and (v) the extent of histopathological changes correlated positively with progression and were widespread in subcortical structures.

All cases shared some common features, although there were also some important differences (Table 1, Figure 1 and 2).

Case 1 was classified as clinically definite ALS within the first year. Frontal lobe involvement with behavioral changes and a "PSP-like" syndrome with Parkinsonism and supranuclear ophthalmoplegia developed only later. Illness duration was 14 months. Neuronal inclusions were common in the hippocampal and temporal areas, caudate nucleus, thalamus, and oculomotor complex, and in the inferior olive, while TDP-43 immunoreactive neurites and glial inclusions and neuronal loss was prominent in the caudate nucleus, locus coeruleus, substantia nigra, and oculomotor nuclei. Skein-like inclusions were detected in the hypoglossal nucleus.

In contrast, the "PSP-like" syndrome in Case 2 appeared earlier, was associated with behavioral signs of FTD and Parkinsonism, progressed slowly to dementia and severe rigidity with supranuclear gaze palsy. The clinical course was longer (4 years) and lower motor neuron signs came very late. Neuronal inclusions (including skein-like neurites and glial pathology) were more widespread and strongly associated with subcortical and brainstem nuclei.

Case 3 had a clinical picture that was most typical for PSP, linked to FTD and upper motor neuron involvement. Neuronal inclusions and neurites and glial inclusions had dispositions similar to Case 2 (hippocampal areas, fronto-temporal cortex, caudate, putamen, substantia nigra). A pathogenic mutation (102 delC) in the PGRN gene was also detected.

Clinical manifestations, age of onset, duration of illness and distribution of neuropathological changes of PGRN gene mutation carriers are variable: the majority have progressive aphasia or frontotemporal dementia, but without symptoms of MND or PSP [13, 15]. Familial forms of FTLD expressing prominent parkinsonian features have been linked to mutations in MAPT, formerly frontotemporal dementia and Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17) [16]. We did not observe tau pathology and MAPT gene analysis excluded mutations in all presented cases. More recently, MAPT negative cases with a familial setting were shown to harbor mutations in the PGRN gene [17]. These cases were neuropathologically identified as tau negative but ubiquitin-positive [5, 18]. The clinical and neuropathological phenotype and age of disease onset, tends to be highly variable not only among families but even between individuals in one family [19]. Case 3 expands this group to include the PSP-like phenotype, in addition to primary progressive aphasia [20] or corticobasal syndrome [21].

In summary, criteria for probable PSP [8] were fulfilled in Cases 1 and 2 (Table 1). In Case 3, all signs were present, but the evolution lasted more than one year. Overall, features of PSP developed later in the course of our patients. It must be noted that none were diagnosed clinically as PSP. The severe frontal and temporal atrophy on MRI (Figure 2) was oriented more towards FTLD; however all displayed considerable features of PSP. It is noteworthy, that in addition to subcortical dementia, typical for PSP [22], all of our patients developed considerable behavioral and personality changes compatible with behavioral variants of FTD. This becomes most apparent in Case 3 (apathy, perseverations, stereotypical behavior, lack of insight and dynamic aphasia), however, rigidity, oculomotor findings, considerably restricted verbal fluency and the absence of disinhibition or compulsivity are less typical of FTD. MRI scans of our patients showed only mild asymmetry of atrophy and the degree of frontal and temporal atrophy was not as impressive as in many other FTLD-TDP-43 cases. The subcortical white matter changes in Case 3 are similar to findings in PGRN mutation carriers [23]. Finally, MRIs in our patients did not show posterior fossa findings evoking PSP (such as hummingbird sing, thinning of superior cerebellar peduncle or prominent mesencephalic atrophy).

All patients corresponded to possible/probable MND with significant upper motor neuron signs in Case 3, lower motor neuron involvement in Case 2, and both in Case 1 [12]. The extent of histopathological changes (Figure 4) correlated positively with progression.

The distribution of histopathological changes in particular TDP-43 immunoreactive profiles involved subcortical and brainstem structures somewhat more than reported previously, in association with FTLD-TDP subtypes [24], supporting the notion that TDP-43 proteinopathies are representatives of a multisystem proteinopathy [25] with involvement of anatomical regions corresponding to predominant clinical symptoms. The progression rate of clinical features differed in our cases (Figure 1).

An important finding in our patients is the impairment of visuospatial functions in all three cases. This profile is rather uncommon in parkinsonian syndromes. A large prospective cohort of patients with PSP and multiple system atrophy (MSA) demonstrated the existence of a cognitive profile similar to that previously reported in idiopathic Parkinson´s disease. Visuospatial functions scores, measured on the dementia rating scale (DRS), for construction and conceptualization, were largely preserved [26]. Another study suggested that visuospatial functions are not consistently impaired in atypical parkinsonian syndromes, but the degree and pattern varied across the diseases. This could imply a different neural basis in each condition, since the most prominent visuospatial impairment was linked to corticobasal degeneration [27]. There are other findings however, which suggest that visuospatial and visuoperceptual dysfunctions reflect structural grey matter changes in temporo-parietal cortical regions of Parkinson´s disease patients [28].

Severe visuospatial impairment is not a characteristic of motor neuron disease. Patients with FTLD-MND and ubiquitin inclusions whose visuospatial skills were tested by copying drawings and the visual object and space perception battery (VOSP) subtests, did not show remarkable alterations [29].

On the other hand, visuospatial deficits have been reported in FTLD patients. Koedam et al. recently published a very interesting observation; neuropsychological profiles, including visuospatial impairment, does not differ between frontotemporal dementia patients with and without lobar atrophy, although patients without atrophy, on MRI, were less severely demented [30]. Other authors have suggested that parietal deficits including visuospatial dysfunction may be a prominent feature of PGRN mutations [31].

A very similar observation to ours demonstrated a movement disorder resembling PSP and associated with dementia and MND-like pathology. Besides selective verbal and action processing, there was visual recall and recognition (Door and People test (DPT)) and lower construction and conceptualization scores (VOSP). The most important neuropathological findings were abundant ubiquitin-positive inclusions, which were also detected in areas without apparent atrophy or neuronal loss [32].

There have been only very limited reports of oculomotor abnormalities in FTLD-MND. In our cases we found significant neuropathological changes in the mesencephalic tegmentum. This supports the notion that vulnerability patterns may differ in TDP-43 proteinopathies (sporadic and genetic forms) leading to variable clinical phenotypes. Indeed, our observations with several previous studies indicate that sporadic TDP-43 proteinopathies may present as MND, FTD, progressive aphasia, FTD with MND, corticobasal syndrome [11], and PSP-like phenotypes associated with FTD and features of MND. These clinical phenotypes may show overlap with tauopathies; indeed PSP (tauopathy) may be also associated with MND and corticospinal tract degeneration [33]. Furthermore, these clinical phenotypes were reported in cases with an established genetic cause, linked not only to PGRN mutations but also to mutations in TARDBP. MND, FTLD-MND, and FTD with supranuclear palsy having also been associated with TARDBP variations [34–36], demonstrating the complexity of clinico-pathological and genetic relations.

In conclusion, our observation suggests that: (i) association of "PSP-like" to "ALS-plus" syndromes in the same patient may represent a clinically distinguishable entity within a broad spectrum of TDP-43 positive neurodegeneration; (ii) this clinical manifestation develops irrespective of genetic variation in TARDBP, MAPT, and PGRN; (iii) the clinical picture seems to be related to preferential localization of pathogenetic inclusions and neuronal cell loss rather than specific pathological mechanisms of the disease itself; and (iv) motor neuron involvement, visuospatial and frontal behavioral signs should be systematically explored in atypical PSP patients.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained in one case from the patient and in two cases from patient´s relatives for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

- (FTD):

-

Frontotemporal dementia

- (FTLD-TDP):

-

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin and TDP-43 positive neuronal inclusions

- (FTLD-MND):

-

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration associated with motor neuron disease

- (ALS):

-

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- (TDP-43):

-

Transactive response DNA binding protein 43

- (TARDBP):

-

Transactive response DNA binding protein

- (PGRN):

-

Progranulin

- (MAPT):

-

Microtubule-associated protein

- (PSP):

-

Progressive supranuclear palsy

- (MRI):

-

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- (EMG):

-

Electromyography

- (AVLT):

-

Auditory Verbal Learning Test

- (MMSE):

-

Mini Mental State Examination

- (ADL):

-

Activities of Daily Living

- (VOSP):

-

Visual Object and Space Perception battery

- (MSA):

-

Multiple System Atrophy

- (DRS):

-

Dementia Rating Scale

References

Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, Truax AC, Micsenyi MC, Chou TT, Bruce J, Schuck T, Grossman M, Clark CM, McCluskey LF, Miller BL, Masliah E, Mackenzie IR, Feldman H, Feiden W, Kretzschmar HA, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM: Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006, 314: 130-133. 10.1126/science.1134108.

Geser F, Martinez-Lage M, Kwong LK, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, frontotemporal dementia and beyond: the TDP-43 diseases. J Neurol. 2009, 256: 1205-1214. 10.1007/s00415-009-5069-7.

Shintaku M, Oyanagi K, Kaneda D: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with dementia showing clinical parkinsonism and severe degeneration of the substantia nigra: report of an autopsy case. Neuropathology. 2007, 27: 295-299. 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2007.00763.x.

Brandmeir NJ, Geser F, Kwong LK, Zimmerman E, Qian J, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ: Severe subcortical TDP-43 pathology in sporadic frontotemporal lobar degeneration with motor neuron disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2008, 115: 123-131.

Cruts M, Gijselinck I, van der Zee J, Engelborghs S, Wils H, Pirici D, Rademakers R, Vandenberghe R, Dermaut B, Martin JJ, van Duijn C, Peeters K, Sciot R, Santens P, De Pooter T, Mattheijssens M, Vanden Broeck M, Cuijt I, Vennekens K, De Deyn PP, Kumar-Singh S, Van Broeckhoven C: Null mutations in progranulin cause ubiquitin-positive frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17q21. Nature. 2006, 442: 920-924. 10.1038/nature05017.

Van Deerlin VM, Wood EM, Moore P, Yuan W, Forman MS, Clark CM, Neumann M, Kwong LK, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM, Grossman M: Clinical, genetic, and pathologic characteristics of patients with frontotemporal dementia and progranulin mutations. Arch Neurol. 2007, 64: 1148-1153. 10.1001/archneur.64.8.1148.

Chen-Plotkin AS, Xiao J, Geser F, Martinez-Lage M, Grossman M, Unger T, Wood EM, Van Deerlin VM, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM: Brain progranulin expression in GRN-associated frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2010, 119: 111-122. 10.1007/s00401-009-0576-2.

Litvan I, Bhatia KP, Burn DJ, Goetz CG, Lang AE, McKeith I, Quinn N, Sethi KD, Shults C, Wenning GK: Movement Disorders Society Scientific Issues Committee report: SIC Task Force appraisal of clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinsonian disorders. Mov Disord. 2003, 18: 467-486. 10.1002/mds.10459.

Paviour DC, Lees AJ, Josephs KA, Ozawa T, Ganguly M, Strand C, Godbolt A, Howard RS, Revesz T, Holton JL: Frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-only-immunoreactive neuronal changes: broadening the clinical picture to include progressive supranuclear palsy. Brain. 2004, 127: 2441-2451. 10.1093/brain/awh265.

McCluskey LF, Elman LB, Martinez-Lage M, Van Deerlin V, Yuan W, Clay D, Siderowf A, Trojanowski JQ: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-plus syndrome with TAR DNA-binding protein-43 pathology. Arch Neurol. 2009, 66: 121-124. 10.1001/archneur.66.1.121.

Tartaglia MC, Sidhu M, Laluz V, Racine C, Rabinovici GD, Creighton K, Karydas A, Rademakers R, Huang EJ, Miller BL, Dearmond SJ, Seeley WW: Sporadic corticobasal syndrome due to FTLD-TDP. Acta Neuropathol. 2010, 119: 365-374. 10.1007/s00401-009-0605-1.

Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, Munsat TL: El Escorial revisited: revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2000, 1: 293-299. 10.1080/146608200300079536.

Gass J, Cannon A, Mackenzie IR, Boeve B, Baker M, Adamson J, Crook R, Melquist S, Kuntz K, Petersen R, Josephs K, Pickering-Brown SM, Graff-Radford N, Uitti R, Dickson D, Wszolek Z, Gonzalez J, Beach TG, Bigio E, Johnson N, Weintraub S, Mesulam M, White CL, Woodruff B, Caselli R, Hsiung GY, Feldman H, Knopman D, Hutton M, Rademakers R: Mutations in progranulin are a major cause of ubiquitin-positive frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2006, 15: 2988-3001. 10.1093/hmg/ddl241.

Cairns NJ, Bigio EH, Mackenzie IR, Neumann M, Lee VM, Hatanpaa KJ, White CL, Schneider JA, Grinberg LT, Halliday G, Duyckaerts C, Lowe JS, Holm IE, Tolnay M, Okamoto K, Yokoo H, Murayama S, Woulfe J, Munoz DG, Dickson DW, Ince PG, Trojanowski JQ, Mann DM, Consortium for Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration: Neuropathologic diagnostic and nosologic criteria for frontotemporal lobar degeneration: consensus of the Consortium for Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2007, 114: 5-22. 10.1007/s00401-007-0237-2.

Skoglund L, Brundin R, Olofsson T, Kalimo H, Ingvast S, Blom ES, Giedraitis V, Ingelsson M, Lannfelt L, Basun H, Glaser A: Frontotemporal dementia in a large Swedish family is caused by a progranulin null mutation. Neurogenetics. 2009, 10: 27-34. 10.1007/s10048-008-0155-z.

Spillantini MG, Bird TD, Ghetti B: Frontotemporal dementia and Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17: a new group of tauopathies. Brain Pathol. 1998, 8: 387-402.

Boeve BF, Baker M, Dickson DW, Parisi J, Giannini C, Josephs KA, Hutton M, Pickering-Brown SM, Rademakers R, Tang-Wai D, Jack CR, Kantarci K, Shiung MM, Golde T, Smith GE, Geda YE, Knopman DS, Petersen RC: Frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism associated with the IVS1+1G- > A mutation in progranulin: a clinicopathologic study. Brain. 2006, 129: 3103-3114. 10.1093/brain/awl268.

Baker M, Mackenzie IR, Pickering-Brown SM, Gass J, Rademakers R, Lindholm C, Snowden J, Adamson J, Sadovnick AD, Rollinson S, Cannon A, Dwosh E, Neary D, Melquist S, Richardson A, Dickson D, Berger Z, Eriksen J, Robinson T, Zehr C, Dickey CA, Crook R, McGowan E, Mann D, Boeve B, Feldman H, Hutton M: Mutations in progranulin cause tau-negative frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17. Nature. 2006, 442: 916-919. 10.1038/nature05016.

Benussi L, Binetti G, Sina E, Gigola L, Bettecken T, Meitinger T, Ghidoni R: A novel deletion in progranulin gene is associated with FTDP-17 and CBS. Neurobiol Aging. 2008, 29: 427-435. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.10.028.

Pickering-Brown SM: Progranulin and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2007, 114: 39-47. 10.1007/s00401-007-0241-6.

Spina S, Murrell JR, Huey ED, Wassermann EM, Pietrini P, Grafman J, Ghetti B: Corticobasal syndrome associated with the A9D Progranulin mutation. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007, 66: 892-900. 10.1097/nen.0b013e3181567873.

Bak TH, Crawford LM, Hearn VC, Mathuranath PS, Hodges JR: Subcortical dementia revisited: similarities and differences in cognitive function between progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), corticobasal degeneration (CBD) and multiple system atrophy (MSA). Neurocase. 2005, 11: 268-273. 10.1080/13554790590962997.

Kelley BJ, Haidar W, Boeve BF, Baker M, Graff-Radford NR, Krefft T, Frank AR, Jack CR, Shiung M, Knopman DS, Josephs KA, Parashos SA, Rademakers R, Hutton M, Pickering-Brown S, Adamson J, Kuntz KM, Dickson DW, Parisi JE, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Petersen RC: Prominent phenotypic variability associated with mutations in Progranulin. Neurobiol Aging. 2009, 30: 739-751. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.08.022.

Josephs KA, Stroh A, Dugger B, Dickson DW: Evaluation of subcortical pathology and clinical correlations in FTLD-U subtypes. Acta Neuropathol. 2009, 118: 349-358. 10.1007/s00401-009-0547-7.

Geser F, Martinez-Lage M, Robinson J, Uryu K, Neumann M, Brandmeir NJ, Xie SX, Kwong LK, Elman L, McCluskey L, Clark CM, Malunda J, Miller BL, Zimmerman EA, Qian J, Van Deerlin V, Grossman M, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ: Clinical and pathological continuum of multisystem TDP-43 proteinopathies. Arch Neurol. 2009, 66: 180-189. 10.1001/archneurol.2008.558.

Brown RG, Lacomblez L, Landwehrmeyer BG, Bak T, Uttner I, Dubois B, Agid Y, Ludolph A, Bensimon G, Payan C, Leigh NP, NNIPPS Study Group: Cognitive impairment in patients with multiple system atrophy and progressive supranuclear palsy. Brain. 2010, 133: 2382-2393.

Bak TH, Caine D, Hearn VC, Hodges JR: Visuospatial functions in atypical parkinsonian syndromes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006, 77: 454-456. 10.1136/jnnp.2005.068239.

Pereira JB, Junqué C, Martí MJ, Ramirez-Ruiz B, Bargalló N, Tolosa E: Neuroanatomical substrate of visuospatial and visuoperceptual impairment in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2009, 24: 1193-1199. 10.1002/mds.22560.

Bak TH, O'Donovan DG, Xuereb JH, Boniface S, Hodges JR: Selective impairment of verb processing associated with pathological changes in Brodmann areas 44 and 45 in the motor neurone disease-dementia-aphasia syndrome. Brain. 2001, 124: 103-120. 10.1093/brain/124.1.103.

Koedam EL, Van der Flier WM, Barkhof F, Koene T, Scheltens P, Pijnenburg YA: Clinical characteristics of patients with frontotemporal dementia with and without lobar atrophy on MRI. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010, 24: 242-247.

Rohrer JD, Warren JD, Omar R, Mead S, Beck J, Revesz T, Holton J, Stevens JM, Al-Sarraj S, Pickering-Brown SM, Hardy J, Fox NC, Collinge J, Warrington EK, Rossor MN: Parietal lobe deficits in frontotemporal lobar degeneration caused by a mutation in the progranulin gene. Arch Neurol. 2008, 65: 506-513. 10.1001/archneur.65.4.506.

Bak TH, Yancopoulou D, Nestor PJ, Xuereb JH, Spillantini MG, Pulvermüller F, Hodges JR: Clinical, imaging and pathological correlates of a hereditary deficit in verb and action processing. Brain. 2006, 129: 321-332.

Josephs KA, Katsuse O, Beccano-Kelly DA, Lin WL, Uitti RJ, Fujino Y, Boeve BF, Hutton ML, Baker MC, Dickson DW: Atypical progressive supranuclear palsy with corticospinal tract degeneration. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006, 65: 396-405. 10.1097/01.jnen.0000218446.38158.61.

Gitcho MA, Bigio EH, Mishra M, Johnson N, Weintraub S, Mesulam M, Rademakers R, Chakraverty S, Cruchaga C, Morris JC, Goate AM, Cairns NJ: TARDBP 3'-UTR variant in autopsy-confirmed frontotemporal lobar degeneration with TDP-43 proteinopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2009, 118: 633-645. 10.1007/s00401-009-0571-7.

Kovacs GG, Murrell JR, Horvath S, Haraszti L, Majtenyi K, Molnar MJ, Budka H, Ghetti B, Spina S: TARDBP variation associated with frontotemporal dementia, supranuclear gaze palsy, and chorea. Mov Disord. 2009, 24: 1843-1847. 10.1002/mds.22701.

Benajiba L, Le Ber I, Camuzat A, Lacoste M, Thomas-Anterion C, Couratier P, Legallic S, Salachas F, Hannequin D, Decousus M, Lacomblez L, Guedj E, Golfier V, Camu W, Dubois B, Campion D, Meininger V, Brice A, French Clinical and Genetic Research Network on Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration/Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration with Motoneuron Disease: TARDBP mutations in motoneuron disease with frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Ann Neurol. 2009, 65: 470-473. 10.1002/ana.21612.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2377/11/50/prepub

Acknowledgements

This study was partly supported by Austrian-Czech bilateral OAD project (2008-12/CZ 04/2008), by the Czech Ministry of Education (research program MŠM 0021620849) and grants 309/09/1053 and 309/09/P204 of the Grant Agency of Czech Republic. The authors wish to thank Pavel Fendrych, MD, PhD (IKEM hospital, Prague, Czech Republic), Josef Vymazal, MD, DSc (Homolka Hospital Prague, Czech Republic) and Zdeněk Seidl, MD, PhD (General Faculty Hospital, Prague, Czech Republic), for providing MRI services, and Tom Secrest for revisions on the English version of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

RR, JF and RM made substantial conceptual contributions to the design of the study, analysis of sources, and contributed to drafting of the manuscript. GGK was involved in data analysis and gave critical revision of the manuscript regarding important intellectual content. RM and GGK performed neuropathological and immunohistological examination. TS performed and discussed the results of genetic analysis. PR, IH and JH supplied important and relevant clinical data of the patients. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Rusina, R., Kovacs, G.G., Fiala, J. et al. FTLD-TDP with motor neuron disease, visuospatial impairment and a progressive supranuclear palsy-like syndrome: broadening the clinical phenotype of TDP-43 proteinopathies. A report of three cases. BMC Neurol 11, 50 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-11-50

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-11-50