Abstract

The fact that primary school is a pre-adolescent period makes it important in terms of regulating emotions. The beginning signals of adolescence occur during this period. It is clear that this challenging process of emotion regulation is linked to age and development, along with parental characteristics and the interactions of the child with the parent. It is believed that researching the variables that influence emotion regulation can help individuals maintain healthy social interactions throughout their journey from childhood to adulthood. In this context, parents’ mindfulness levels, which include both intrapersonal and interpersonal processes, play a crucial role in helping their children regulate their emotions. The current study aims to ascertain the serial mediating role of mindfulness in marriage and mindfulness in parenting in the relationship between parents’ dispositional mindfulness and the emotion regulation of their children aged 6–10. A total of 333 parents, all of whom were married and had children ranging from 6 to 10 years old, participated in the study. “Emotion Regulation Checklist”, “Mindfulness in Marriage Scale”, “Mindful Attention Awareness Scale” and “Mindfulness in Parenting Questionnaire” were used in the study. To determine the mediating role, the bootstrap method was used via structural equation modeling (SEM) to ascertain the mediating role. The SEM and bootstrap method revealed that there was a serial mediation effect between parents’ dispositional mindfulness and emotion regulation of their children. This effect was attributed to mindfulness in marriage and mindfulness in parenting. Given that the primary school years are a critical developmental stage in improving emotion regulation skills, family-based interventions supporting parents’ mindfulness in three important areas (dispositional, marital, and parental) may help to improve the children’s capacity to regulate their emotions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The period of late childhood is a crucial phase for development of emotions and the ability to regulate them. In this period, children start primary school, and the primary school plays an esssential role in emotion regulation along with the changes in children’s social environment (Schlesier et al., 2019). In addition, during this period, children’s social world expands, social interactions increase, and emotion regulation skills become especially essential to social processes (Saarni, 1999). For this reason, the study on emotion regulation in primary school children has had a significant growth over the last two decades (Schlesier et al., 2019). According to Gross (1998), emotion regulation refers to the processes that influence the specific feelings people experience, the timing of these emotions, and the way they feel and reflect these emotions. Emotion regulation encompasses the control of both unpleasant emotions (e.g. stress, anger and disappointment) and good emotions, in line with one’s objectives (McRae & Gross, 2020). Stifter and Augustine (2019) emphasized that emotion regulation becomes more developed with age; thus, it is considered a fundamental developmental task for intrapersonal and interpersonal functioning. Emotion regulation processes play an important role in attention control, problem solving, and healthy relationships. Considering that these issues are of great importance for school success and personal satisfaction, it can be said that emotion regulation processes contribute to positive functioning in children (Macklem, 2008). There are also developmental tasks that the child must accomplish in the first 7 years of life that involve the regulation of emotions. These include tolerance of frustration, interacting with and enjoying others, coping with fear and anxiety, self-defense within acceptable behavioral limits, enduring times of alone, having a curiosity in the drive for learning, and making friends (Cole et al., 1994). Thus, it can be said that emotion regulation processes are important for primary school children in many ways.

The emotional regulation skills of children depend not only on their development and age but also on the environment in which they grow up. Parents are the most important factor in providing an environment where children can express their emotions openly and freely. Parents’ acceptance of their children’s emotions allows them to recognize their own emotions and have control over the intensity of their emotions (Şahin & Arı, 2015). Within the family, each individual can be seen as a system in its own right. Additionally, they also function as subsystems within a larger hierarchy of systems. These systems and subsystems are constantly interacting with one another (Cox & Paley, 1997). In other words, the traits of the parental subsystem (including parental mental health and mindfulness) have an influence on the dyadic subsystem (parent-child bond, healthy relationship), and subsequently, the child subsystem (emotional and cognitive growth).

According to this perspective, it can be said that the internal processes of the parent affect the child’s emotion regulation (Zhang et al., 2019). Focusing on these internal processes, the level of dispositional mindfulness was evaluated in this study. Mindfulness, according to Kabat-Zinn (2003), is the awareness that arises from deliberately and impartially focusing on the experience right now. Along with this, a greater focus and awareness of the present moment or reality is what is meant by mindfulness (Brown & Ryan, 2003). As these definitions make clear, mindfulness reflects the internal processes of the individual. Mindfulness is an important concept in situations such as physical health, mental well-being, and interpersonal relationships (Brown & Ryan, 2004). In parallel, resistances and fears to mindfulness were found to negatively predict life satisfaction (Deniz et al., 2023). Also, mindfulness practices have a functional role in thinking clearly, focusing on what is most important, and in the moment, maintaining high performance and becoming more empathetic (Altan, 2021). Parents’ dispositional mindfulness does not only affect their own mental health; it also affects the development of their children. Parents’ high level of mindfulness enables their children to be competent in regulating emotions (Zhang et al., 2019). For instance, mothers who have a greater level mindfulness are more likely to exhibit positive parenting behaviors and generate favorable emotional climate that enhance the emotional development of their children (Ren et al., 2021).

The process of mindfulness in interpersonal relationships is emphasized by the concept of “interpersonal mindfulness” (Pratscher et al., 2019). According to Duncan (2007), confining the concept of mindfulness to the individual’s inner realm may be insufficient to explain an individual’s mindfulness in interpersonal relationships. Therefore, interpersonal mindfulness becomes one of the crucial elements of mindfulness. Enhancing the quality of marriage and the ability to effectively co-parent is one of the important functions of mindfulness in interpersonal interactions. That way, one of the key components that it also affects is emotion regulation abilities. According to the study findings, it can be concluded that children who experience unpleasant feelings directed by parents towards each other are at risk for the development of social and emotional problems (Morris et al., 2007). In addition, parents can use mindfulness in their relationships with their spouses (interpersonal mindfulness in marriage) (Bögels et al., 2014). Interpersonal mindfulness in parenting is a concept evaluated within the scope of interpersonal mindfulness.

Mindful parenting is a theoretical framework that Kabat-Zinn (1997/2014) emphasizes and defines as embracing the full endeavor of parenting our children as best we can in a mutuality of love, exploration, and not knowing in the present moment (Kabat-Zinn & Kabat-Zinn, 2021). Duncan (2007) used the existing theoretical framework on “mindfulness” (i.e., deliberate potential to sustain consciousness and attention in the here and now without making any judgements) to conceptualize mindful parenting. Similarly, Erus and Deniz (2018) proposed the concept of mindfulness in marriage based on interpersonal mindfulness by Pratscher et al. (2018) and mindful parenting (Duncan, 2007; Kabat-Zinn, 1997/2014; McCaffrey et al., 2017). It reflects how mindfulness affects spousal relationships. It enhances an individual’s self-regulation skills in the relationship, promoting acceptance and non-judgment of their spouse, leading to improved marital adjustment (Erus & Deniz, 2020). Mindfulness in marriage has been investigated in studies with different variables such as marital satisfaction, well-being, emotional intelligence, and social skills in early childhood (see Deniz et al., 2020; Erus & Deniz, 2020; Erus & Tekel, 2020; Karaağaç & Deniz, 2023; Parlar & Akgün, 2018). Parents with high levels of marital adjustment express their negative emotions towards each other in a healthier way; thus, the children of these parents are less exposed to the negative emotions directed by their parents towards each other and experience a healthier emotional development process. For this reason, it is possible to say that not only the parents’ dispositional mindfulness but also their interpersonal mindfulness in marriage stands out as an important variable in the emotion regulation of the child. Studies have found that well-being, emotional intelligence, and marital satisfaction are related to mindfulness (Burpee & Langer, 2005; Hanley et al., 2015; Schutte & Malouff, 2011) and marital mindfulness (Deniz et al., 2020; Erus, 2019). Individuals with high levels of dispositional mindfulness and mindfulness in marriage transfer these functional characteristics to other systems in the family (relationship between parent and child, child’s emotional development, etc.). It is thought that the reflection of these functional characteristics will occur, especially in the parental relationship, so that parenting skills will have positive effects on the emotional development of the child.

It can be said that dispositional mindfulness affects mindfulness in marriage; in parallel, mindfulness in marriage affects mindfulness in parenting. As a result of a study (Karaağaç & Deniz, 2023) that examined the relationship between mindfulness in parenting and marriage. Mindfulness in marriage and mindful parenting have both been found to be significantly positively related. There are limited studies investigating mindfulness in marriage and mindful parenting together, but there are many studies (Booth & Amato, 1994; Cox et al., 1989; Klausli & Owen, 2011; Morrill et al., 2010; Yu & Gamble, 2008) addressing marital relationship and parenting. In one of these studies, it was found that marital quality improved co-parenting; thus, it positively affected parenting practices (Morrill et al., 2010). A significant number of studies examining the relationships between marriage and parenting rely on the principles and concepts of family systems theory. The relationships between the components of the family system are circular which means that every component both affects and is affected by the others. (Grych, 2002). Consequently, it may be said that interpersonal mindfulness in marriage, which is a reflection of the relationship between partners, is related to mindful parenting, which is a reflection of the parent-child relationship. Increasing the level of mindfulness enables parents to behave more consciously and exhibit a non-judgmental attitude towards themselves and their children (Corthorn & Milicic, 2016). However, variability in parents’ neurobiological, hormonal, and behavioral states may increase the difficulties in parental self-regulation, which might significantly impact the emotional and behavioral regulation of their children. (Rutherford et al., 2015). Additionally, the inclusion of mindfulness in parenting practices leads to an increase in positive parenting practices and a decrease in negative practices and is associated with lower levels of psychopathology in youth (Parent et al., 2016). It is possible to state that mindful parenting has an important effect on the emotion regulation of the child, in addition to the parent’s dispositional mindfulness and mindfulness in marriage. According to research in the literature, it may be inferred that parents’ dispositional mindfulness, mindfulness in marriage, and mindfulness in parenting are associated with emotion regulation skills in children who are 6 to 10 years old. According to research, those who have high levels of mindfulness also have high levels of emotional control (Bao et al., 2015; Gillespie et al., 2015). Interpersonal mindfulness is positively linked to emotional intelligence and emotion regulation (Erus & Deniz, 2020; Pratscher et al., 2019). Children of parents who are successful in emotion regulation can model these skills; they can acquire the ability to control their emotions through observing and modeling these positive skills of their parents (Morris et al., 2007). In addition, mindfulness supports positive parenting practices (Han et al., 2021) and constructive parenting behaviors significantly affect emotion regulation skills of children (Rutherford et al., 2015). Considering this angle, it can be emphasized that dispositional mindfulness of the parents, mindfulness in marriage, and mindfulness in parenting play a crucial part in the emotion regulation skills of their children. Within the context of this research, it was intended to investigate the relationship between parents’ dispositional mindfulness and emotion regulation of their children, and the serial mediation roles of mindfulness in marriage and parenting. The problem statement for the research is stated below.

-

Do mindfulness in marriage and mindfulness in parenting have a serial mediating role in the relationship between parents’ dispositional mindfulness and emotion regulation of their children?

Methods

Participants

The method for collecting the data was convenience sampling. This sampling method selects participants who are generally located in a place (hospital, school, database, website, membership list, etc.) suitable for the purpose of the research. Convenience sampling is not costly, is not as time-consuming as other sampling methods, and is simple (Stratton, 2021). In this context, the researchers collected data by reaching out to parents in their circle who were married and had children between the ages of 6 and 10 and by reaching out to parents working in institutions around the researchers. Participants were reached via a web-based survey. The researchers used a Google form to collect the data. The Google form first added informed consent, then a personal information form with demographic data and measurement tools in that order. When the research link was followed, the participants, who were informed about the research, completed the questionnaires after confirming their consent to the research. The researchers sent the link to parents via social media while they were gathering the data. The data were gathered from a total of 378 parents living in Türkiye. Out of the collected data, 45 entries were not included due to being incomplete, inaccurate, not meeting the requirements or being identified as outliers. Consequently, the demographic information of the remaining 333 parents is presented in Table 1.

Table 1 shows the demographic information for the parents and their children according to the information obtained from 333 parents who participated in the study. As can be seen, 261 (78.4%) of the parents were female and 72 (21.6%) were male; 170 (51.1%) of the children were girl and 163 (48.9%) were boy. In relation to ages of the children, 119 (35.7%) were 6–7 years old, 89 (26.7%) were 8 years old, and 125 (37.6%) were 9–10 years old. Among the parents, 107 (32.1%) were between 27 and 36 years old, and 226 (67.9%) were between 37 and 52 years old. Among the children, 110 (33%) had no siblings, and 223 (67%) had at least one sibling. Regarding birth order, 215 (64.6%) of the children were the first child, and 118 (35.4%) were the second or higher birth order. Regarding the educational level of the parents, 131 (39.3%) of the parents had an associate’s degree or less, while 202 (60.7%) had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Regarding the employment status of the parents, there are 149 (44.7%) children with one working parent and 184 (55.3%) children with both working parents.

Measures

Emotion Regulation Checklist

The Emotion Regulation Checklist was developed to measure children’s emotion regulation skills (Shields & Cicchetti, 1997). Kapçı et al. (2009) adapted The Emotion Regulation Checklist into Turkish. There are 24 items on the scale, which an adult who knows the child can complete. In the scale, a 4-point Likert type was utilized. “Emotion Regulation Checklist” was completed by the parents. The Turkish version of the scale includes the “Emotion Regulation” and “Lability/Negativity” subscales. The items on the Emotion Regulation subscale are associated with aspects such as understanding emotions, coherence, and cautiousness (e.g., “My child is empathic towards others; shows concern when others are upset or distressed”). The items on the Lability/Negativity subscale are about to reacting with anger, emotional intensity, and inability to regulate negative emotions (e.g., “My child responds angrily to limit setting by adults”). While an increase in the score acquired from the scale means that emotion regulation is at a low level, a decrease in the score obtained from the scale means that emotion regulation is at a high level. In addition, index values (GFI > .86; RMSR < .04; AGFI > .83; RMSEA < .06) used to interpret the outcomes of confirmatory factor analysis were reported to be acceptable. The internal consistency coefficient of the entire scale was found to be .84, the internal consistency coefficient of the Lability/Negativity subscale was .80 and the internal consistency coefficient of the Emotion Regulation subscale was .81 (Kapçı et al., 2009). The Cronbach’s alpha values obtained in this study were .76 for the Lability/Negativity subscale, .69 for the Emotion Regulation subscale, and .79 for the total score of the scale.

Mindful Attention Awareness Scale

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) (Brown & Ryan, 2003) is the most often used, validated and translated dispositional mindfulness measure (Morissette Harvey et al., 2023). The fact that it is a brief, well-validated measurement tool with strong psychometric qualities that can be used with a variety of clinical and non-clinical groups may further contribute to its broad use (Medvedev et al., 2016). MAAS was adapted into Turkish by Özyeşil et al. (2011). This 15-item scale assesses an individual’s general propensity to recognize fleeting moments in everyday life (e.g., “I find it difficult to stay focused on what’s happening in the present” and “I find myself doing things without paying attention”). A 6-point Likert type was used in the scale. The Turkish version of the scale has a single-factor structure and a high score demonstrates a high level of mindfulness. As an outcome of the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), the fit indices confirmed that MAAS showed a one-factor structure ((χ²/df) = 189.57/90; RMSEA = 0.058; GFI = 0.92; CFI = 0.91). The scale’s Cronbach’s alpha value was found to be 0.80 (Özyeşil et al., 2011) and obtained in this research was 0.86.

Mindfulness in Marriage Scale

Erus and Deniz (2018) developed the Mindfulness in Marriage Scale to assess the interpersonal mindfulness in married relationships in Turkish sample. The scale has 12 items (e.g., “I accept my spouse as she or he is” and “I recognize how my feelings for my partner affect my thoughts and behaviors”), has a unidimensional structure and a 5-point Likert scale is used. A high score obtained from this scale demonstrates a high level of interpersonal mindfulness in the marital relationship. Development study of the scale was conducted with two separate study groups consisting of married individuals who had been married for at least 1 year. Exploratory factor analysis and reliability analysis were conducted with the data acquired from the first group of 384 participants. Confirmatory factor analysis was performed with the data acquired from the second group consisting of 162 participants. As an outcome of exploratory factor analysis, the factor loadings of the items were found to be between 0.48 and 0.78. As a result of confirmatory factor analysis, the fit index values of the model were calculated as RMSEA = 0.046, GFI = 0.93, AGFI = 0.90, CFI = 0.99, NFI = 0.95. The scale’s Cronbach’s alpha value was determined to be 0.87 and 0.85 as a result of analyses conducted with two separate study groups (Erus & Deniz, 2018). The scale’s Cronbach’s alpha value obtained in this research is 0.81.

Mindfulness in Parenting Questionnaire

Mindfulness in Parenting Questionnaire (MIPQ) was adapted into Turkish by Aslan Gördesli et al. (2018) in order to assess mindfulness levels of parents. The scale’s Turkish version has two subscales, “Being in the Moment with the Child” and “Parental Self-Efficacy.” The scale is a 4-point Likert-type with 24 items. “Parental Self-Efficacy” measures the parents’ conscious awareness of their behavior towards their child (e.g., “Over the past two weeks, how often did you take a moment to think before punishing your child”). “Being in the Moment with the Child” measures whether the parent is aware of their own inner experiences during the time they interact with their child (e.g., “Over the past two weeks, did you have fun and act goofy with your child”). On this scale, a high score denotes a parent’s high level of mindfulness in their interactions with their child. It was found that the scale’s goodness of fit indices were within acceptable bounds for the two-factor structure (χ²/df = 1.927, GFI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.049, IFI = 0.90, CFI = 0.90) as an outcome of the confirmatory factor analysis. According to the calculation of Cronbach’s alpha, the Parental Self-Efficacy subscale had an internal consistency coefficient of 0.73, the Being in the Moment with the Child subscale of 0.87 and the entire scale of 0.83 (Aslan Gördesli et al., 2018). Cronbach’s alpha values for the Parental Self-Efficacy subscale, the Being in the Moment with the Child subscale, and the overall scale score were 0.91, 0.86 and 0.83, respectively, in this study.

Data Analysis

Analysed data was derived from a sample of 333 parents, consisting of 261 mothers and 72 fathers. SPSS and AMOS package programs were used for statistical analyses and a reference significance level of 0.05 in this study. The analyses were performed in sequential steps. In the first stage, the mean, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis, and Mahalanobis distance of the variables were analysed, and Pearson correlation analysis was tested for evaluation of multicollinearity problem.

The second stage used the two-stage SEM that Anderson and Gerbing (1988) suggested to investigate the connections between dispositional mindfulness, mindfulness in marriage, mindfulness in parenting, and emotion regulation. To conduct SEM, the parceling method was applied to the unidimensional Mindfulness in Marriage Scale and Mindful Attention Awareness Scale. Parceling is a extensively used technique in SEM (Little et al., 2002). The parceling technique refers to creating “item plots” based on the sums of responses to items for use in analysing latent variables (Russell et al., 1998). A parcel, which is an aggregate indicator, consists of the mean of two or more responses, behaviors or items (Little et al., 2002). In this study, the scale items were classified into two sub-dimensions according to their factor loadings through exploratory factor analysis. Consequently, according to these analyses, the data were suitable for SEM. During the first phase of the SEM, the measurement model and, during the second phase of the SEM, the structural model were analysed. GFI, AGFI, CFI, NFI, TLI, SRMR, and RMSEA values were determined. Additionally, a 95% confidence interval (CI) and 5000 resampling using the bootstrap technique were employed to assess the indirect effect’s significance. Parent’s age and parent’s gender were control variables.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Skewness and kurtosis values of the variables were determined to range between 0.454 and − 0.669. According to George and Mallery (2016), kurtosis and skewness coefficients within the range of + 2 to -2 suggest a normal distribution. After examining univariate normality, multivariate outliers were analysed using the Mahalanobis distance method (De Maesschalck et al., 2000). Following Field’s (2016) recommendation for Mahalanobis distance, one data point below 15 was excluded. As a result, the SEM was constructed using data from 332 parents: 261 mothers and 71 fathers. In the subsequent analysis with these 332 data points, potential multicollinearity among the variables was examined. Tabachnick and Fidell (2015) emphasized that a relationship of .90 and above between variables constitutes a multicollinearity problem. The results of the Pearson correlation analysis revealed correlation coefficients ranging from .25 to .44. The correlation findings indicate the absence of multicollinearity among the variables. The results of Pearson correlation analyses conducted to obtain the relationships between emotion regulation, dispositional mindfulness, mindfulness in marriage, and mindfulness in parenting are presented in Table 2. In the interpretation of correlations, correlations between .00 and .30 were considered “low”, .31 and .70 were considered “moderate,” .71 and above were considered “high” (Moore et al., 2009).

In Table 2, there is a significant moderate negative relationship between dispositional mindfulness and child’s emotion regulation (r = − .35, p < .01). Since a low mean score on the Emotion Regulation Checklist indicates that the child’s emotion regulation is high, this result is interpreted as meaning that the higher the level of dispositional mindfulness of the parent, the higher the level of emotion regulation of the child. In parallel with this, there is a significant moderate negative relationship between mindfulness in marriage and child’s emotion regulation (r = − .39, p < .01) and between mindful parenting and emotion regulation of the child (r = − .43, p < .01). As indicated by the other results of the correlation analysis, there is a significant moderate positive relationship between dispositional mindfulness and mindfulness in marriage (r = .40, p < .01), a low positive significant relationship between dispositional mindfulness and mindful parenting (r = .25, p < .01), and a significant moderate positive relationship between mindfulness in marriage and mindful parenting (r = .44, p < .01). As a result of the Pearson correlation analyses results being significant, serial multiple mediation analyses were conducted.

Serial Multiple Mediation Analyses

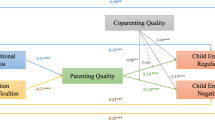

In the first phase of the structural model, the measurement model, which aims to analyse the relationships between the variables, was evaluated. In the measurement model, there are eight observed variables that form four latent variables. The latent variable of mindfulness in parenting consists of Being in the Moment with the Child and Parental Self-Efficacy variables. Emotion regulation latent variable consists of Emotion Regulation and Lability/Negativity variables. The latent variables of dispositional mindfulness and mindfulness in marriage were formed in two dimensions as a result of the parceling method. The goodness of fit indices in the measurement model were assessed using the fit index standards suggested by Schermelleh-Engel et al. (2003). As a result of the comparison of the goodness of fit indices in the model with the goodness of fit criteria, it was found that the p value of the χ2 was significant (p < .01). In addition, χ²/df = 2.099 and RMSEA = 0.058 values were found to be within acceptable ranges and SRMR = 0.0241; CFI = 0.986; NFI = 0.975; AGFI = 0.944; GFI = 0.978; and TLI = 0.973 values were found to be within good fit ranges. Therefore, the measurement model was validated to test the structural model. As seen in Fig. 1, the values showing the standardized path coefficients of the variables.

Structural Model 1. PSE Parental Self-Efficacy; BMC Being in the Moment with the Child; ER Emotion Regulation; L/N Lability/Negativity; MAAS1 First Parcel of Dispositional Mindfulness; MAAS2 Second Parcel of Dispositional Mindfulness; MM1 First Parcel of Mindfulness in Marriage; MM2 Second Parcel of Mindfulness in Marriage **p < .01

As an outcome of the structural equation model in which the variables of dispositional mindfulness, mindfulness in marriage, mindfulness in parenting, and emotion regulation of the child are analysed in Fig. 1, direct effects are evaluated first. It is observed that dispositional mindfulness predicts the child’s emotion regulation ability negatively (β =-0.26, p < .01) and mindfulness in marriage positively (β = 0.49, p < .01). Mindfulness in marriage predicted mindfulness in parenting positively (β = 0.50, p < .01) and emotion regulation of the child negatively (β =-0.23, p < .01). Mindfulness in parenting was also found to directly predict emotion regulation of the child negatively (β =-0.45, p < .01). In Fig. 1, the path between dispositional mindfulness and mindful parenting (β = 0.06, p > .05) was found to be insignificant and this model was stated as Structural Model 1. Baron and Kenny (1986) stated that it is undesirable for the path between dispositional mindfulness and the mediating variable, mindfulness in parenting, to be insignificant. Thus, after deleting the insignificant path, the model was analysed once again. In Fig. 2, the standardized path coefficients (Structural Model 2) are given.

Structural Model 2. PSE Parental Self-Efficacy; BMC Being in the Moment with the Child; ER Emotion Regulation; L/N Lability/Negativity; MAAS1 First Parcel of Dispositional Mindfulness; MAAS2 Second Parcel of Dispositional Mindfulness; MM1 First Parcel of Mindfulness in Marriage; MM2 Second Parcel of Mindfulness in Marriage **p < .01

As seen in Fig. 2, all path coefficients in Structural Model 2 are significant. The age and gender of the parent were control variables, and when the direct effects were evaluated as a result of the model, dispositional mindfulness predicted emotion regulation of the child negatively (β =-0.27, p < .01) and mindfulness in marriage positively (β = 0.49, p < .01); mindfulness in marriage positively predicted mindfulness in parenting (β = 0.53, p < .01) and negatively predicted emotion regulation of the child (β =-0.22, p < .01); and mindfulness in parenting negatively predicted emotion regulation of the child (β =-0.45, p < .01). The p value of the χ² was within the acceptable range and the values of χ²/df = 1.738, p < .05; RMSEA = 0.047; SRMR = 0.0345; CFI = 0.984; NFI = 0.964; AGFI = 0.943; GFI = 0.974; TLI = 0.972 met the criteria of good fit.

In the last stage of serial multiple mediation analyses, bootstrap analysis with 95% confidence interval (CI) and 5000 resampling was performed to analyse the serial mediation effect of mindfulness in marriage and mindfulness in parenting in the relationship between parents’ dispositional mindfulness and emotion regulation of their children. According to the study, it concluded that parents’ dispositional mindfulness affected the emotion regulation of their children through the serial mediation of mindfulness in marriage and mindful parenting, and the standardized indirect effect coefficient was − 0.24. As a result of bootstrapping, it was found that the lower bound value was − 0.375 and the upper bound value was − 0.140 in confidence intervals. According to Hayes (2022), if there is not zero between the confidence interval’s lower and upper bounds, the indirect impact is considered significant. In light of these findings, it can be determined that mindfulness in marriage and parenting play a sequential mediating role in the relationships between parents’ dispositional mindfulness and child’s emotion regulation.

Discussion

The research revealed that mindfulness in marriage and parenting plays a serial mediating role between parents’ dispositional mindfulness and their children’s emotion regulation. According to this result, dispositional mindfulness predicts mindfulness in marriage, mindfulness in marriage predicts mindfulness in parenting, and these relationships predict the emotion regulation of the child. Firstly, it was figured out that dispositional mindfulness predicts mindfulness in marriage. Mindfulness processes are highly effective in interpersonal relationships (Wachs & Cordova, 2007). People with high levels of dispositional mindfulness show the characteristics of having more positive views about others, behaving more empathically, and being more sensitive to the needs of others (Gambrel & Keeling, 2010). These characteristics positively affect interpersonal relationships, especially marital relationships. Researchers emphasize the importance of mindfulness in marital relationships (Burpee & Langer, 2005; Deniz et al., 2020; Gambrel & Keeling, 2010; Gambrel & Piercy, 2015; Isfahani et al., 2018; Molajafar et al., 2015). Wachs and Cordova (2007) stated that awareness and acceptance processes, which are components of mindfulness, lead to a decrease in emotional impulsivity in interpersonal relationships, which enhanced constructive communication among partners. Thus, it is possible to say that the positive effects of mindfulness also contribute to the married relationship. Erus (2019), while explaining mindfulness in marriage, emphasized that it is important to accept the feelings and thoughts of one’s spouse without judgment. The concept of “non-judgement” is one of the attitudinal foundations of dispositional mindfulness (Kabat-Zinn, 2013). In addition, mindfulness contributes to the individual to feel emotionally calm and to form thoughts away from evaluation and judgement (Sauer et al., 2011). From this point of view, it can be stated that individuals who adopt a non-judgemental attitude have higher levels of mindfulness. It can be said that individuals who approach themselves with a non-judgemental attitude will transfer this attitude to their relationships with their spouses and their level of mindfulness in marriage will increase.

In this study, when mindfulness in marriage was a mediating variable, it was found that dispositional mindfulness did not predict mindfulness in parenting. When the correlational relationships in the study were analysed, a low level significant positive relationship was found between dispositional mindfulness and mindfulness in parenting, while a moderate level significant positive relationship was found between mindfulness in parenting and marriage. When these relationships were transferred to path analysis, the path coefficient between dispositional mindfulness and mindfulness in parenting, which had a low correlational relationship, was not significant, while the path coefficient between mindfulness in marriage and parenting, which had a medium correlational relationship, was significant. Therefore, it can be interpreted that dispositional mindfulness predicts mindfulness in marriage, and this relationship significantly explains mindfulness in parenting. In addition, Erus (2019) emphasized that dispositional mindfulness is related to the individual’s turning inward and achieving spiritual balance within oneself; therefore, it has little contribution to the processes in interpersonal relationships. Thus, it can be stated that dispositional mindfulness is insufficient for directly predicting mindfulness in parenting when it is a means of mindfulness in marriage, since mindfulness in marriage becomes a priority for mindfulness in parenting. Another explanation for this result can be seen as the role of mindfulness in marriage in predicting mindful parenting. In the literature, there have been various studies examining the positive relationships between marital relationship and parenting (Booth & Amato, 1994; Cox et al., 1989; Klausli & Owen, 2011; Morrill et al., 2010; Yu & Gamble, 2008). For example, in a study conducted with 70 mothers and fathers, it was concluded that marital hostility and estrangement from the spouse negatively affected responsiveness in parenting (parents being compassionate and caring towards the needs of the child), whereas supportive marital behavior positively affected responsiveness in parenting (Klausli & Owen, 2011). Morrill et al. (2010) conducted a study with 76 couples with children under the age of 18 and found that marital quality positively affected parenting practices by improving co-parenting. Family systems theory (Cox & Paley, 1997) emphasizes that subsystems within the family affect each other and that positive emotions arising from inter-parental relationships can be transferred to parent-child relationships. Thus, it can be stated that family systems theory supports the finding that mindfulness in marriage, which refers to the mindfulness of spouses in their interactions with each other (inter-parental relationships) (Erus, 2019), predicts mindfulness in parenting, which refers to mindful parenting to children (relationship between parent and child) (Duncan et al., 2009; Ahemaitijiang et al., 2021). In addition, the first person the individual interacts with in the family system is the spouse. In the family, the spousal subsystem (marital relationship) manifests itself first, and the parental subsystem enters the family system with the birth of the child. Thus, in terms of interpersonal mindfulness, the individual’s bond with their spouse is established prior to their bond with their children. The high level of mindfulness in marriage as a result of the spouses’ interactions with each other positively affects the relationship with the child within the parenting subsystem by increasing marital adjustment (Erus & Deniz, 2020) and contributing to the formation of healthy family characteristics. The positive effects of mindfulness in marriage on an individual basis contribute to the establishment of a mindful relationship based on parenting.

Another result of this study is that mindfulness in marriage predicts children’s emotion regulation skills. The emotional climate in the family plays an essential part in children’s emotional development and emotion regulation skills. When there is a negative emotional environment in the family, children become emotionally reactive due to the negative emotional reactions they observe from relatives (Morris et al., 2007). The marital relationship is also included in the emotional climate. Mindfulness in marriage includes processes such as listening carefully to one’s spouse, accepting one’s spouse’s feelings and thoughts without judgment, and responding to one’s spouse’s behaviors by regulating oneself (Erus, 2019). Thus, it can be stated that parents with high levels of mindfulness in marriage will tend to build a positive emotional atmosphere in the family, and this positive emotional climate will reduce the risk of the child being emotionally reactive. Research shows that one of the important factors affecting children’s emotion regulation skills is conflict between parents (Crockenberg et al., 2007; Frankel et al., 2015; Porter et al., 2003; Siffert & Schwarz, 2011). For example, Siffert and Schwarz (2011), in a research conducted with 246 students between the ages of 9 and 12 and their mothers, found that parents’ negative conflict resolution increased children’s maladaptive emotion regulation strategies. Thus, it can be considered that the ways of conflict resolution between parents are important for children to learn to use healthy and adaptive emotion regulation strategies. Couples’ levels of mindfulness and their likelihood of experiencing marital conflict are negatively related. In addition, an individual with a high level of mindfulness can think about how others may interpret the same situation differently. This increases the possibility of finding solutions to problems (Burpee & Langer, 2005) and using compatible strategies in the process of finding solutions. These adaptive strategies used by the spouses towards each other positively affect the emotion regulation strategies of the child. In line with all this information, it can be stated that the level of mindfulness in marriage and the emotion regulation skills of children are positively related.

According to the results of the study, mindfulness in parenting predicts emotion regulation skills of children significantly. Research results from the literature (Mafaza & Mayang Sarry, 2022; Moran et al., 2022; Moreira & Canavarro, 2020; Zhang et al., 2019) support the findings of this study. One of the factors that contributes positively to emotion regulation skills of children is parental emotion coaching. Parental emotion coaching includes attitudes such as parents being aware of emotions of their children and accepting their emotions. Parents with a high level of mindfulness in parenting tend to engage in emotion coaching. Parents who are more successful in emotion coaching realize their children’s emotions, talk to them about these emotions, and allow them to experience and regulate their emotions (Ramsden & Hubbard, 2002). In addition, differences in parental responsiveness, such as acceptance and support, significantly affect the growth of the ability of children to regulate their emotions (Morris et al., 2007). These characteristics, which play a crucial part in emotion regulation of children, appear as the basic characteristics of mindfulness in parenting (Zhang et al., 2019). Parents who have high levels of mindfulness exhibit an accepting and supportive attitude towards their children’s needs. Considering that mindfulness in parenting includes the attitudes of “emotional awareness of self and child” and “nonjudgmental acceptance of self and child” (Duncan et al., 2009) and that mindful parenting programs have positive effects on being aware of and accepting children’s emotions (Townshend et al., 2016), it is seen that mindfulness in parenting has a positive relationship with the emotion regulation abilities of children.

The findings in this research suggest that the relationship between parents’ dispositional mindfulness and emotion regulation of their children is serially mediated by mindfulness in marriage and mindfulness in parenting. In the literature, there are research results indicating that parents’ level of mindfulness predicts the emotion regulation of their children (Ren et al., 2021; Yan et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2019). For example, in a study conducted with parents who have children between the ages of 6 and 12, it was found that the mindfulness of the parent positively affected the emotion regulation of the child by increasing quality parenting (Yan et al., 2021). According to another research conducted with parents whose children were between the ages of 3 and 6, it was concluded that the mindfulness of parents contributed to children’s competence in regulating emotions (Zhang et al., 2019). The outcomes of this study are supported by research results found in the literature. In addition, research proves that individuals who have high levels of mindfulness are more successful in regulating their emotions (Bao et al., 2015; Erus & Deniz, 2020; Gillespie et al., 2015). Based on the results of these studies, it can be said that children of parents with high emotion regulation skills can model these skills; by observing and modeling their parents’ behaviors, they can learn how to control their emotions (Morris et al., 2007). Thus, it can be stated that parents who have high levels of mindfulness are more successful in regulating their emotions, and children can learn the emotion regulation strategies by observing them. In addition to observation in the parent-child bound, the relationship between parent and child is also effective in regulating the child’s thoughts, emotions and behaviors. To ensure that this effect to be positive, it is especially important for the parent to be able to regulate their emotions individually and to have self-regulation skills. However, individuals who have high levels of mindfulness are also more likely to acquired positive emotions (Garland et al., 2015). Parents with high levels of mindfulness will transfer the positive emotions they experience to the parent-child relationship. As a result of the positive emotions transferred to parent-child interactions, children with parents with high levels of mindfulness will show less emotional lability and experience less emotional negativity (Zhang et al., 2019).

Limitations and Recommendations

There are several limitations in this study. As one limitation, the emotion regulation levels of children were reached from the perspective and evaluation of parents. This may lead to less reliable results, as no data is collected directly from the child. In future research, the data collected directly from children can be evaluated together with the data collected from parents. For example, gathering data based on the self-report of the child, observing the child, and collecting data from parents to assess the child can be used in conjunction so more reliable results can be obtained. In addition, in this research, data were gathered from the parents of the child, who were the mother or father. Collecting data from only one parent may not be sufficient to obtain consistent and accurate information about the child. Therefore, future research should, if possible, collect data from both parents. Another limitation is that because the study was model-based and relationally performed, it is not possible to establish a cause-and-effect relationship. Longitudinal and experimental research are required to identify the links between parents’ dispositional mindfulness, mindfulness in marriage, mindfulness in parenting, and the emotion regulation of children. For instance, a mindfulness-based program in different areas (marriage, parenting, and dispositional) can be applied to parents by practitioners, and the emotion regulation levels of their children can be examined before and after the program. In addition, collecting data from the same parents for their children at annual intervals and longitudinally analysing and comparing the results can be presented as a valuable suggestion for future research.

In this study, when mindfulness in marriage and parenting were in the model, the relationship between parents’ dispositional mindfulness and the emotion regulation of children remained significant. It is thought that different variables may also be involved in the relationship between parents’ dispositional mindfulness and the emotion regulation of children. In future studies, the mediating role of variables such as parenting styles, parent-child relationship, parent’s personality traits, and child’s temperament in the relationship between dispositional mindfulness of parents and emotion regulation of their children can be examined. In addition, the MAAS questionnaire, like other prominent questionnaires (e.g., the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire; Baer et al., 2008), has been criticized as inadequate by some authors, owing to its unidimensional factorial structure (Morissette Harvey et al., 2023). For this purpose, a study in which sub-dimensions of mindfulness such as describing, observing, acting with awareness, nonreactivity and nonjudging of inner experience (Baer et al., 2008) can be examined in future studies. Last but not least, there are measurement tools (see De Bruin et al., 2014; Duncan, 2007; McCaffrey et al., 2017) commonly used in the literature to measure mindful parenting. Although McCaffrey et al. (2017) state that the sub-dimensions of these measurement tools are related, it is crucial to investigate the relevant variables with different dimensions of mindful parenting as emotional non-reactivity in parenting, emotional awareness of the self, non-judgmental acceptance of parental functioning (De Bruin et al., 2014), self-regulation in the parenting relationship, listening with full attention, emotion regulation in the parenting context, and parenting in accordance with goals and values (Duncan et al., 2009) in future research. Recommendations to be given to practitioners based on the results of the study are as important as the recommendations for future research. Given the results of the study, psychological counselors, psychologists, and therapists working with families and children can include the intrapersonal and interpersonal mindfulness practices of parents in their psychological counseling sessions. In this way, children’s emotion regulation skills can be increased by increasing the mindfulness of parents in internal processes, marriage, and parenting relationships. In this study, the relationships between mindfulness, mindfulness in marriage, mindfulness in parenting, and the emotion regulation levels of children aged 6–10 years were revealed. Based on these findings, psychoeducational programs that develop dispositional mindfulness, mindfulness in marriage and mindfulness in parenting, mindfulness-based spouse, and parenting skills programs can be adopted and applied to parents who have children between the ages of 6 and 10. The intervention of these programs can potentially enhance the emotion regulation skills of the children.

Conclusion

As far as we know, this research is the first to find out the mediating effects of mindfulness in marriage and mindfulness in parenting on the link between parents’ dispositional mindfulness and the emotion regulation of their children. According to the extant literature, research, and outcomes of this study, it is possible to say that mindfulness in marriage and parenting are important variables between parents’ dispositional mindfulness and the emotion regulation of their children. In this study, it was revealed that the parent has an crucial function in the emotional regulation of the child. It is discussed that both the internal processes of the parent and the marital and parenting processes play a role in the family system and how they may affect the emotional regulation of the child. Based on these results, it can be said that the parents’ dispositional mindfulness, reflecting their inner experiences, affects their relationships with both their spouses and their children, and these relationships affect the parents’ perception of the children’s emotion regulation.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ahemaitijiang, N., Fang, H., Ren, Y., Han, Z. R., & Singh, N. N. (2021). A review of mindful parenting: Theory, measurement, correlates, and outcomes. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 15, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1834490921103701.

Altan, M. Z. (2021). Bilinçli farkındalık ve İngiliz Dili ve Öğretimi Lisans öğrencilerinin MAAS’a (the mindful attention awareness Scale/Bilinçli Farkındalık Dikkat Ölçeği) dayalı farkındalık ve dikkat düzeyleri [Mindfulness and mindfulness and attention levels of English Language and Teaching undergraduate students based on MAAS (the mindful attention awareness scale)]. International Journal of Humanities and Education, 7(16), 612–649. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/ijhe/issu.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411.

Aslan Gördesli, M., Arslan, R., Çekici, F., Aydın Sünbül, Z., & Malkoç, A. (2018). The psyhometric properties of Mindfulness in Parenting Questionnaire (MIPQ) in Turkish sample. European Journal of Education Studies, 5(5), 175–188. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1477467.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., Walsh, E., Duggan, D., & Williams, J. M. G. (2008). Construct validity of the five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15(3), 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191107313003.

Bao, X., Xue, S., & Kong, F. (2015). Dispositional mindfulness and perceived stress: The role of emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 78, 48–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.01.007.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173.

Bögels, S. M., Hellemans, J., van Deursen, S., Römer, M., & van der Meulen, R. (2014). Mindful parenting in mental health care: Effects on parental and child psychopathology, parental stress, parenting, coparenting, and marital functioning. Mindfulness, 5(5), 536–551. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0209-7.

Booth, A., & Amato, P. R. (1994). Parental marital quality, parental divorce, and relations with parents. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 56(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/352698.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2004). Perils and promise in defining and measuring mindfulness: Observations from experience. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 242–248. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bph078.

Burpee, L. C., & Langer, E. J. (2005). Mindfulness and marital satisfaction. Journal of Adult Development, 12, 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-005-1281-6.

Cole, P. M., Michel, M. K., & O’Donnell Teti, L. (1994). The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation: A clinical perspective. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59(2/3), 73–100. https://doi.org/10.2307/1166139.

Corthorn, C., & Milicic, N. (2016). Mindfulness and parenting: A correlational study of nonmeditating mothers of preschool children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 1672–1683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0319-z.

Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (1997). Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology, 48(1), 243–267. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.243.

Cox, M. J., Owen, M. T., Lewis, J. M., & Henderson, V. K. (1989). Marriage, adult adjustment, and early parenting. Child Development, 60(5), 1015–1024. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130775.

Crockenberg, S. C., Leerkes, E. M., & Lekka, S. K. (2007). Pathways from marital aggression to infant emotion regulation: The development of withdrawal in infancy. Infant Behavior & Development, 30(1), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.009.

De Bruin, E. I., Zijlstra, B. J., Geurtzen, N., van Zundert, R. M., van de Weijer-Bergsma, E., Hartman, E. E., Nieuwesteeg, A. M., Duncan, L. G., & Bögels, S. M. (2014). Mindful parenting assessed further: Psychometric properties of the Dutch version of the interpersonal mindfulness in parenting scale (IM-P). Mindfulness, 5, 200–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0168-4.

De Maesschalck, R., Jouan-Rimbaud, D., & Massart, D. L. (2000). The mahalanobis distance. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 50(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-7439(99)00047-7.

Deniz, M. E., Erus, S. M., & Batum, D. (2020). Examining marital satisfaction in terms of interpersonal mindfulness and perceived problem solving skills in marriage. International Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 12(2), 69–83. https://doi.org/10.15345/iojes.2020.02.005.

Deniz, M. E., Arslan, U., Satici, B., Kaya, Y., & Akbaba, M. F. (2023). A Turkish adaptation of the fears and resistances to Mindfulness Scale: Factor structure and psychometric properties. Journal of Social and Educational Research, 2(2), 79–84. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10442299.

Duncan, L. G. (2007). Assessment of mindful parenting among parents of early adolescents: Development and validation of the Interpersonal Mindfulness in Parenting Scale [Unpublished Doctorate Dissertation]. The Pennsylvania State University.

Duncan, L. G., Coatsworth, J. D., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). A model of mindful parenting: Implications for parent–child relationships and prevention research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12, 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-009-0046-3.

Erus, S. M. (2019). Evlilikte bilinçli farkındalık ile öznel iyi oluş arasındaki ilişkide duygusal zekâ ve evlilik uyumunun aracılık rolü [The mediating role of emotional intelligence and marital adjustment in the relationship between mindfulness in marriage and subjective well-being] (Publication No. 554025) [Doctoral dissertation, Yıldız Technical University]. YÖK National Thesis Center. https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/giris.jsp.

Erus, S. M., & Deniz, M. E. (2018). Evlilikte Bilinçli Farkındalık Ölçeğinin geliştirmesi: Geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalışması [Development of Mindfulness in Marriage Scale (MMS): Validity and reliability study]. The Journal of Happiness & Well-Being, 6(2), 96–113.

Erus, S. M., & Deniz, M. E. (2020). The mediating role of emotional intelligence and marital adjustment in the relationship between mindfulness in marriage and subjective well-being. Pegem Journal of Education and Instruction, 10(2), 317–354. https://doi.org/10.14527/pegegog.2020.011.

Erus, S. M., & Tekel, E. (2020). Development of Interpersonal Mindfulness Scale-TR (IMS-TR): A validity and reliability study. European Journal of Educational Research, 9(1), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.9.1.103.

Field, A. (2016). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. Sage Publications.

Frankel, L. A., Umemura, T., Jacobvitz, D., & Hazen, N. (2015). Marital conflict and parental responses to infant negative emotions: Relations with toddler emotional regulation. Infant Behavior and Development, 40, 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2015.03.004.

Gambrel, L. E., & Keeling, M. L. (2010). Relational aspects of mindfulness: Implications for the practice of marriage and family therapy. Contemporary Family Therapy, 32, 412–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-010-9129-z.

Gambrel, L. E., & Piercy, F. P. (2015). Mindfulness-based relationship education for couples expecting their first child—part 1: A randomized mixed‐methods program evaluation. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 41(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12066.

Garland, E. L., Farb, N. A., Goldin, R., P., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2015). Mindfulness broadens awareness and builds eudaimonic meaning: A process model of mindful positive emotion regulation. Psychological Inquiry, 26(4), 293–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2015.1064294.

George, D., & Mallery, M. (2016). IBM SPSS statistics 23 step by step a simple guide and reference. Routledge.

Gillespie, B., Davey, M. P., & Flemke, K. (2015). Intimate partners’ perspectives on the relational effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction training: A qualitative research study. Contemporary Family Therapy, 37(4), 396–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-015-9350-x.

Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271.

Grych, J. H. (2002). Marital relationships and parenting. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Social conditions and applied parenting (pp. 203–225). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Han, Z. R., Ahemaitijiang, N., Yan, J., Hu, X., Parent, J., Dale, C., DiMarzio, K., & Singh, N. N. (2021). Parent mindfulness, parenting, and child psychopathology in China. Mindfulness, 12, 334–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01111-z.

Hanley, A., Warner, A., & Garland, E. L. (2015). Associations between mindfulness, psychological well-being, and subjective well-being with respect to contemplative practice. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16, 1423–1436. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9569-5.

Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression based approach. The Guilford Press.

Isfahani, N., Bahrami, F., Etemadi, O., & Mohamadi, R. A. (2018). Effectiveness of counseling based on mindfulness and acceptance on the marital conflict of intercultural married women in Iran. Contemporary Family Therapy, 40, 204–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-017-9454-6.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg016.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2013). The foundations of mindfulness practice: Attitudes and commitment. Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your mind to face stress, pain and illness (Rev. ed.) (pp. 19–38). https://www.mindfulnessinbiz.org.hk/wp-content/uploads/The-Foundation-of-Mindfulness-Practice.pdf.

Kabat-Zinn, J., & Kabat-Zinn, M. (2021). Mindful parenting: Perspectives on the heart of the matter. Mindfulness, 12(2), 266–268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01564-7.

Kabat-Zinn, M., & Kabat-Zinn, J. (1997/2014). Everyday blessings: The inner work of mindful parenting. Hachette.

Kapçı, E. G., Uslu, R., Akgün, E., & Acer, D. (2009). İlköğretim çağı çocuklarında duygu ayarlama: Bir ölçek uyarlama çalışması ve duygu ayarlamayla ilişkili etmenlerin belirlenmesi [Emotion regulation in elementary school children: A scale adaptation study and determination of factors related to emotion regulation]. Turk J Child Adolesc Ment Health, 16(1), 13–20.

Karaağaç, Z. G., & Deniz, M. E. (2023). Mindfulness in marriage and mindfulness in parenting as predictors of social skills in early childhood. Cukurova University Faculty of Education Journal, 52(1), 180–206. https://doi.org/10.14812/cuefd.1205785.

Klausli, J. F., & Owen, M. T. (2011). Exploring actor and partner effects in associations between marriage and parenting for mothers and fathers. Parenting: Science and Practice, 11(4), 264–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2011.613723.

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1.

Macklem, G. L. (2008). Practitioner’s guide to emotion regulation in school-aged children. Springer Science & Business Media.

Mafaza, M., & Mayang Sarry, S. (2022). Emotional regulation ability in early childhood: Role of Coparenting and mindful parenting. Journal An-Nafs: Kajian Penelitian Psikologi, 7(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.33367/psi.v7i1.2000.

McCaffrey, S., Reitman, D., & Black, R. (2017). Mindfulness in Parenting Questionnaire (MIPQ): Development and validation of a measure of mindful parenting. Mindfulness, 8, 232–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0596-7.

McRae, K., & Gross, J. J. (2020). Emotion regulation. Emotion, 20(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000703.

Medvedev, O. N., Siegert, R. J., Feng, X. J., Billington, D. R., Jang, J. Y., & Krägeloh, C. U. (2016). Measuring trait mindfulness: How to improve the precision of the mindful attention awareness scale using a Rasch model. Mindfulness, 7, 384–395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0454-z.

Molajafar, H., Mousavi, S. M., Lotfi, R., Ghasemnejad, S. M., & Falah, M. (2015). Comparing the effectiveness of mindfulness and emotion regulation training in reduction of marital conflicts. Journal of Medicine and Life, 8(2), 111–116.

Moore, D. S., McCabe, G. P., & Craig, B. A. (2009). Introduction to the practice of statistics. W.H. Freeman and Company.

Moran, M. J., Murray, S. A., LaPorte, E., & Lucas-Thompson, R. G. (2022). Associations Between Children’s Emotion Regulation, Mindful Parenting, Parent Stress, and Parent Coping During the COVID-19 Pandemic. The Family Journal, 10664807221123562. https://doi.org/10.1177/10664807221123562.

Moreira, H., & Canavarro, M. C. (2020). Mindful parenting is associated with adolescents’ difficulties in emotion regulation through adolescents’ psychological inflexibility and self-compassion. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(1), 192–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01133-9.

Morissette Harvey, F., Paradis, A., Daspe, M., Dion, J., & Godbout, N. (2023). Childhood trauma and relationship satisfaction among parents: A dyadic perspective on the role of mindfulness and experiential avoidance. Mindfulness, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02262-w.

Morrill, M. I., Hines, D. A., Mahmood, S., & Córdova, J. V. (2010). Pathways between marriage and parenting for wives and husbands: The role of coparenting. Family Process, 49(1), 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01308.x.

Morris, A. S., Silk, J. S., Steinberg, L., Myers, S. S., & Robinson, L. R. (2007). The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development, 16(2), 361–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x.

Özyeşil, Z., Arslan, C., Kesici, Ş., & Deniz, M. E. (2011). Adaptation of the mindful attention awareness scale into Turkish. Education and Science, 36(160), 224–235. http://eb.ted.org.tr/index.php/EB/article/view/697.

Parent, J., McKee, L. G., Mahon, J., & Foreh, R. (2016). The association of parent mindfulness with parenting and youth psychopathology across three developmental stages. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(1), 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-9978-x.

Parlar, H., & Akgün, Ş. (2018). Evlilikte bilinçli farkındalık, evlilik doyumu ve problem çözme becerileri ilişkilerinin incelenmesi [Examining the relationships among mindfulness, marital problem solving and marital satisfaction in marriage]. Academic Platform Journal of Education and Change, 1(1), 11–21.

Porter, C. L., Wouden-Miller, M., Silva, S. S., & Porter, A. E. (2003). Marital harmony and conflict: Linked to infants’ emotional regulation and cardiac vagal tone. Infancy, 4(2), 297–307. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327078IN0402_09.

Pratscher, S. D., Rose, A. J., Markovitz, L., & Bettencourt, A. (2018). Interpersonal mindfulness: Investigating mindfulness in interpersonal interactions, co-rumination, and friendship quality. Mindfulness, 9, 1206–1215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0859-y.

Pratscher, S. D., Wood, P. K., King, L. A., & Bettencourt, B. A. (2019). Interpersonal mindfulness: Scale development and initial construct validation. Mindfulness, 10, 1044–1061. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-1057-2.

Ramsden, S. R., & Hubbard, J. A. (2002). Family expressiveness and parental emotion coaching: Their role in children’s emotion regulation and aggression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30(6), 657–667. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020819915881.

Ren, Y., Han, Z. R., Ahemaitijiang, N., & Zhang, G. (2021). Maternal mindfulness and school-age children’s emotion regulation: Mediation by positive parenting practices and moderation by maternal perceived life stress. Mindfulness, 12, 306–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01300-w.

Russell, D. W., Kahn, J. H., Spoth, R., & Altmaier, E. M. (1998). Analyzing data from experimental studies: A latent variable structural equation modeling approach. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 45(1), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.45.1.18.

Rutherford, H. J. V., Wallace, N. S., Laurent, H. K., & Mayes, L. C. (2015). Emotion regulation in parenthood. Developmental Review, 36, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2014.12.008.

Saarni, C. (1999). The development of emotional competence. Guilford Press.

Şahin, G., & Arı, R. (2015). Okul öncesi çocukların duygu düzenleme becerilerinin bağlanma örüntüleri açısından incelenmesi [An examination on emotion regulation of preschool children in terms of attachment patterns]. The Journal of International Education Science, 2(5), 1–12. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/inesj/issue/40015/475738.

Sauer, S., Lynch, S., Walach, H., & Kohls, N. (2011). Dialectics of mindfulness: Implications for western medicine. Philos Ethics Humanit Med, 6(10), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-5341-6-10.

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research, 8(2), 23–74. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2003-08119-003.

Schlesier, J., Roden, I., & Moschner, B. (2019). Emotion regulation in primary school children: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 100, 239–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.02.044.

Schutte, N. S., & Malouff, J. M. (2011). Emotional intelligence mediates the relationship between mindfulness and subjective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(7), 1116–1119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.01.037.

Shields, A., & Cicchetti, D. (1997). Emotion regulation among school-age children: The development and validation of a new criterion Q-sort scale [Abstract]. Developmental Psychology, 33(6), 906–916. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.33.6.906.

Siffert, A., & Schwarz, B. (2011). Parental conflict resolution styles and children’s adjustment: Children’s appraisals and emotion regulation as mediators. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development, 172(1), 21–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2010.503723.

Stifter, C., & Augustine, M. (2019). Emotion regulation. V. LoBue, K. Pérez-Edgar, & K. Buss (Eds.), Handbook of emotional development (pp. 405–430). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-17332-6_16.

Stratton, S. J. (2021). Population research: Convenience sampling strategies. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 36(4), 373–374. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X21000649.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2015). Using multivariate statistics (Trans., M. Baloğlu). Nobel.

Townshend, K., Jordan, Z., Stephenson, M., & Tsey, K. (2016). The effectiveness of mindful parenting programs in promoting parents’ and children’s wellbeing: A systematic review. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 14(3), 139–180. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-2314.

Wachs, K., & Cordova, J. V. (2007). Mindful relating: Exploring mindfulness and emotion repertoires in intimate relationships. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 33(4), 464–481. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2007.00032.x.

Yan, J. J., Schoppe-Sullivan, S., Wu, Q., & Han, Z. R. (2021). Associations from parental mindfulness and emotion regulation to child emotion regulation through parenting: The moderating role of coparenting in Chinese families. Mindfulness, 12, 1513–1523. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-021-01619-3.

Yu, J. J., & Gamble, W. C. (2008). Pathways of influence: Marital relationships and their association with parenting styles and sibling relationship quality. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 17(6), 757–778. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-008-9188-z.

Zhang, W., Wang, M., & Ying, L. (2019). Parental mindfulness and preschool children’s emotion regulation: The role of mindful parenting and secure parent-child attachment. Mindfulness, 10, 2481–2491. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01120-y.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Open access funding provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

This study has been created of the master thesis of Ezgi Güney Uygun supervised by Dr. Seher Merve Erus. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by Yildiz Technical University Social Sciences Scientific Research Ethics Committee (Issue No: 20221201840 28/12/2022).

Informed Consentant

was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Uygun, E.G., Erus, S.M. The Mediating Roles of Mindfulness in Marriage and Mindfulness in Parenting in the Relationship Between Parents’ Dispositional Mindfulness and Emotion Regulation of Their Children. Applied Research Quality Life 19, 1075–1096 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-024-10280-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-024-10280-6