Abstract

Objectives

Considering the Western-Eastern cultural differences in parenting practices, as well as the relative paucity of research on the use of mindfulness-based programs by Chinese parents, we replicated a recently proposed Western model of mindfulness. The purpose of this study was to test the direct and indirect relations between parents’ dispositional mindfulness, mindful parenting, parenting practices, and child internalizing and externalizing behaviors.

Method

A total of 2237 Chinses parents (M = 38.46, SD = 4.43) of 6- to 12-year-old children participated in the current study.

Results

The results showed that parents’ dispositional mindfulness was indirectly associated with child internalizing and externalizing behaviors through mindful parenting and positive parenting practices, whereas this pathway was not significant through negative parenting practices. In addition, mothers and fathers demonstrated almost equal effects on direct and indirect pathways except that mothers showed stronger effects on the relationships between dispositional mindfulness and mindful parenting, as well as on the link between negative parenting practices and child externalizing behaviors.

Conclusions

These findings contribute to a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying how mindfulness and parenting associated with child internalizing and externalizing behaviors, and have important implications for research on interventions aimed at promoting children’s psychological well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Mindfulness refers to “the awareness that emerges through paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment” (Kabat-Zinn 2003, p. 145). Research has highlighted a number of benefits associated with increased mindfulness, including reduced depression and anxiety symptoms (Keng et al. 2011; Moreira and Canavarro 2018). In addition, comparable effectiveness has been observed between mindfulness-based programs and other evidence-based treatments (Goldberg et al. 2017) with promising results demonstrated across various settings and age groups. In recent years, increased attention has focused on the study of dispositional (e.g., Wang et al. 2017) or trait mindfulness (Brown et al. 2007) and mindful parenting (e.g., Parent et al. 2016).

Dispositional mindfulness is an individual’s tendency or inner capacity to pay nonjudgmental attention to experiences and events occurring in the present moment (Brown and Ryan 2003). Research suggests that higher levels of dispositional mindfulness are associated with favorable outcomes, such as better emotion regulation (Baer et al. 2004; Pepping et al. 2013) and more effective coping strategies (Brown and Ryan 2003). In addition, a recent study reported that parents with higher levels of dispositional mindfulness are more likely to engage in mindful parenting with children (Parent et al. 2016).

Mindful parenting consists of nonjudgmental and present-centered awareness during parent-child interactions (Bögels and Restifo 2014; Kabat-Zinn and Kabat-Zinn 1997). It involves listening to the child with full attention, maintaining an awareness of the child’s emotional experience, regulating one’s own emotions during the parenting process, maintaining a non-judgmental acceptance of parental functioning, and being compassionate both towards the child, as well as oneself (Duncan et al. 2009). Research has suggested that higher levels of dispositional mindfulness can increase the likelihood of parents’ engagement in mindful parenting behaviors (de Bruin et al. 2014; Parent et al. 2016). This may be due to mindful parents being better able to distinguish cognitive, affective, and behavioral experiences compared to their less mindful counterparts (Bishop et al. 2004), thus decreasing the likelihood of engaging in maladaptive interactions with children.

Moreover, mindful parenting has been associated with more positive parenting practices (Bazzano et al. 2015; Bögels et al. 2013; Haydicky et al. 2015). During parent-child interactions, a mindful parent is more likely to be consistent with his/her values and goals (Duncan et al. 2009), non-judgmental, demonstrates present-moment awareness, and sensitive to the children’s needs. Thus, mindful parenting has been shown to be associated with lower levels of dysfunctional parenting styles (de Bruin et al. 2014). Parent et al. (2016) examined parents of children at varying developmental stages and reported similar results, suggesting that mindful parenting is directly related to higher levels of positive parenting practices (e.g., warmth and reinforcement) and lower levels of negative parenting practices (e.g., coercion or hostility).

There is a substantial amount of literature establishing the relationship between parenting practices and child psychopathology in Western cultural contexts (Harold et al. 2012; Kawabata et al. 2011; Lindblom et al. 2017), with similar results in Eastern contexts (Baharudin et al. 2011; Lin et al. 2016). For instance, Chinese parents’ support for autonomy was associated with fewer depressive symptoms as reported by their middle-school-aged children (Yan et al. 2017). In addition, harsh parenting from fathers and mothers negatively contributed to children’s emotion regulation and peer aggression (Wang et al. 2017). However, little research has been conducted to delineate the processes through which dispositional mindfulness, mindful parenting, and parenting practices affect child psychopathology outside of Western cultures. This is an important area of exploration given the significant implications of early psychopathology for children’s long-term mental health, academic performance, and overall quality of life (e.g., Barkley et al. 2006; Yap and Jorm 2015).

It has been suggested that over time all cultures derive unique concepts and values on effective parenting, and, therefore, the support for mindful parenting is likely to vary depending on cultural context (Smith and Dishion 2013). In addition, similar parenting practices may have varying effects on children of different cultures (Leung et al. 1998). For example, many researchers have argued that culture shapes how children’s emotional competence is defined and thus influences parenting behaviors, as well as child mental health outcomes (e.g., Friedlmeier et al. 2011). As such, it is of great importance to explore mindful parenting beyond Western cultures and to elucidate the process through which mindful parenting is associated with child outcomes in comparatively understudied cultural contexts (e.g., Chinese culture).

Hofstede (1980) initially proposed the individualism-collectivism dimension to help describe the primary distinction between cultures, and this principle can be used to better understand parenting and the role of parenting in child adjustment beyond Western culture. In this context, Hofstede (1980) proposed that individualistic societies (e.g., the USA) value independence and tend to focus on the self, thus encouraging parenting practices (e.g., warmth) that foster children’s self-reliance. In contrast, collectivistic societies (e.g., China and India) emphasize interdependence and group harmony, thus encouraging parenting practices (e.g., training) that promote children’s obedience to group rules. Parents from individualistic and collectivistic cultures might adopt different parenting behaviors given the various and possibly divergent cultural norms and values related to these behaviors and the associated child outcomes. Little research has extended beyond the Western model of mindful parenting to explicitly discuss cultural issues pertaining to mindful parenting and related child outcomes; however, an emerging line of research has been conducted with Chinese parents that can help provide a foundation for this work. For example, Siu et al. (2016) found parental mindfulness had a negative indirect association on children’s emotional and behavioral problems through a series of positive factors related to the parent-child relationship. These emerging findings have been consistent across Western societies and suggest parents who mindfully interact with their children have higher quality relationships with their children than those who have less mindful interactions (Duncan et al. 2009). This, in turn, is related to greater psychological adjustment and fewer problem behaviors in children (Geurtzen et al. 2015; Parent et al. 2010; Williams and Wahler 2010).

These findings across cultures might be explained by the recent proposition that while Chinese parenting is still largely influenced by traditional cultural values, a Western and child-centered approach has gradually been incorporated into contemporary Chinese parenting, particularly among more highly educated parents (Xu et al. 2014). Despite this preliminary evidence, studies have not delineated the processes through which parental mindfulness and parenting practices are associated with child outcomes using a large Chinese sample. Elucidating these processes with a Chinese sample will enable more nuanced research on the development and implementation of mindfulness-based program with Chinese families.

Parent gender might also shape the processes by which parenting influences child psychopathology (Friedlmeier et al. 2011; Klimes-Dougan et al. 2010). For example, when compared to Western parents (both mothers and fathers) and Chinese mothers, Chinese fathers’ parenting practices (e.g., harsh parenting and physical control) are viewed as strong behavioral modeling for children, especially sons (Chen et al. 2000). Thus, it is important to consider the cultural expectations of mothers and fathers when examining the influence of parenting on their children. Furthermore, gender differences have only been evaluated in the Western context of mindful parenting (Gouveia et al. 2016; Medeiros et al. 2016). In these studies, mothers generally have shown higher level of mindful parenting compared to fathers (e.g., Gouveia et al. 2016), whereas fathers have displayed more supportive emotion socialization with children than mothers when they both participate in mindfulness programs (Coatsworth et al. 2015).

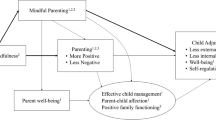

The current study aimed to test the Parent et al. (2016) model of mindful parenting practices and child psychopathology with a large group of parents from Mainland China. The hypotheses of the current study take into consideration the potential impact of cultural context and parent gender (see Fig. 1). First, we hypothesized that parent dispositional mindfulness would be positively associated with mindful parenting and that mindful parenting would be associated with greater positive parenting practices and fewer negative parenting practices. Second, we hypothesized that positive parenting practices would be negatively associated with children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior, whereas negative parenting practices would be positively associated with children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior. Third, regarding the overall theoretical model, we hypothesized that parent dispositional mindfulness would have a negative indirect association with children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior through an increase in mindful parenting, resulting in positive parenting practices, as well as decreased negative parenting practices.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited through flyers that were distributed throughout the community and electronically through communication websites among parents in Mainland China. A total of 2237 Chinese parents (M = 38.46, SD = 4.43) of children aged 6 to 12 (M = 9.40 years, SD = 1.78) participated in the study. Of these, 23% of the parents were fathers, and approximately half (51.9%) of the children were male. Most parents were of the Han nationality (93.8%), held a college degree or above (56.4%), and were employed either full- (67.2%) or part-time (13.7%). Regarding family socioeconomic status, 70.3% of the families reported living in households with an income at or above average for urban Chinese families (around $17,316 annually; National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China 2017). Parents completed a survey designed to collect information regarding demographic variables, dispositional mindfulness, mindful parenting, broadband positive/negative parenting, and externalizing/internalizing behaviors of their children.

Procedure

The Institutional Review Board of sponsoring university approved all materials and procedures. Parents were provided with a brief description of the study prior to obtaining their consent electronically. Following parental consent, they were asked to complete a series of questionnaires through an online questionnaire system (Qualtrics). For families with more than one child, parents were asked to only report on one child who was within the study’s age range (i.e., 6 to 12 years). The families received feedback on parenting and children’s developmental outcomes based on their responses to questionnaires.

Measures

Dispositional Mindfulness

The 39-item Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer et al. 2008) was utilized to assess parental dispositional mindfulness. The current study used the Chinese version of FFMQ (Deng and Xia 2011). These items captured five aspects of individuals’ mindful dispositions: (1) observing, (2) describing, (3) acting with awareness, (4) non-judging of inner experience, and (5) non-reactivity to inner experience. The parents indicated to what extent each statement (e.g., I criticize myself for having irrational or inappropriate emotions) was true using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never or very rarely true) to 5 (very often or always true). A total dispositional mindfulness score was derived by computing the sum of all items. The FFMQ has been found to have good reliability and has been used widely with Chinese samples (Deng and Xia 2011). For the current study, the FFMQ demonstrated good reliability (α = 0.89).

Interpersonal Mindfulness Parenting

Mindful parenting was measured using the composite score from the Interpersonal Mindfulness in Parenting (IM-P; Duncan et al. 2009). The Chinese version of the IM-P, which has been good psychometric properties, was used (Lo et al. 2018). The 31-item version is comprised of five subscales corresponding to the different dimensions of mindful parenting: (1) listening with full attention (e.g., I find myself listening to my child with one ear because I am busy doing or thinking about something else at the same time); (2) emotional awareness of self and child (e.g., I notice how changes in my child’s mood affect my mood); (3) self-regulation in the parenting relationship (e.g., When I am upset with my child, I notice how I am feeling before I take action); (4) non-judgmental acceptance of self and child (e.g., I try to understand my child’s point of view, even when his/her opinions do not make sense to me); and (5) compassion for self and child (e.g., I tend to be hard on myself when I make mistakes as a parent). A 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never true) to 5 (always true) was used, with higher scores indicating higher levels of mindful parenting. Internal consistency in the current sample was good (α = 0.84).

Parenting

Broadband positive and negative parenting practices were measured via the Multidimensional Assessment of Parenting Scale (MAPS; Parent and Forehand 2017). The 16-item positive parenting subscale included items representing proactive parenting, positive reinforcement, warmth, and supportiveness (e.g., I express affection by hugging, kissing, and holding my child). The 18-item negative parenting subscale included items representing hostility, lax control, and physical control (e.g., I spank my child with my hand when he/she has done something wrong). Parents responded to each item using a 5-point Likert rating scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Each item was forward- and back-translated by three associate professors or doctoral students who were fluent in both Chinese and English. The back translation was sent to the original author to ensure that all items retained the original meanings. A pilot study was conducted among adults to determine the readability of the Chinese version, and the lax control scale was removed due to its relatively low factor loadings and reliability. Then two subscales were scored separately, and the reliability of the positive (α = 0.89) and negative subscales (α = 0.89) was excellent.

Child Psychopathology

Children’s externalizing and internalizing behaviors were assessed by the Brief Problem Monitor-Parent Form (BPM-P; Achenbach et al. 2011). Nineteen items of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach 1991) made up the BPM-P for children ages 6–18: six items for attention problems (e.g., inattentive or easily distracted), seven for externalizing problems (e.g., threatens people), and six for internalizing problems (e.g., unhappy, sad, or depressed). Items were rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not true) to 3 (very true). For the purpose of the present study, only the internalizing and externalizing subscales were scored. The Chinese measure of the BPM-P was translated and back-translated by three associate professors of Psychology. The back translation was sent to the original author to ensure that all items retained the original meanings. The internal consistency of the BPM-P in the current study was α = 0.76 for externalizing problems and α = 0.81 for internalizing problems.

Data Analyses

Preliminary Analysis

The associations between primary study variables with categorical (e.g., parent gender) and continuous demographic variables (e.g., child age) were examined using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and zero-order correlations, respectively. We then examined means (M), standard deviations (SD), missing rates, and zero-order correlations of all study variables.

Missing Data

Missing data mechanisms were examined using R packages BaylorEdPsych (Beaujean 2012). Results of Little’s MCAR test showed that the missingness was not completely at random, χ2 (62) = 116.58, p < .001. The associations between missingness in study variables and demographic characteristics were examined using an unpooled t test for continuous demographic variables (i.e., age, education, income) and a chi-square test of independence for dichotomous demographic variables (i.e., parent and child gender). Full information maximum likelihood estimation techniques were used to include all available data.

Structural Equation Models

Model fit and path coefficients for the proposed structural equation models were estimated with R package lavaan (Rosseel 2012). Maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR) was used because of the skewness in the outcome variables. For model fit indices, the model chi-square with its degrees of freedom and p value, Steiger-Lind root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Steiger 1990) and its 90% CI, Bentler comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler 1990), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) of each model were reported as recommended by Kline (2015). The null hypothesis of the chi-square test was that the proposed variance-covariance matrices and sample matrices are the same. RMSEA values below 0.05, 0.08, and 0.10 were indicative of close, reasonable, and mediocre fit, respectively (Browne and Cudeck 1992). For the 90% confidence intervals, lower values less than 0.05 and upper values less than 0.08 were considered acceptable. CFI values greater than 0.95 and SRMR values less than 0.08 suggested good fit (Hu and Bentler 1999).

Model Comparisons and Model Building

A series of nested model comparisons were conducted to build the most parsimonious model. The scaled chi-square difference test (Satorra 2000) was conducted to make comparisons among nested models.

Indirect Effects

Indirect effect sizes were calculated using lavaan, and the standard errors and confidence intervals for the indirect effects were computed with 5000 bootstrap samples. All data analyses were completed using RStudio (RStudio Team 2015).

Results

Preliminary Analysis

All means, standard deviations, missing rates, and bivariate correlations among study variables and covariates are displayed in Table 1. In particular, boys were reported to display higher externalizing [t (2093.44) = 3.36, p < 0.001, d = 0.15] and internalizing behaviors [t (2084.60) = 2.31, p = 0.021, d = 0.10]. Parents of boys reported lower dispositional mindfulness [t (1933.62) = − 2.23, p = 0.026, d = −0.10] and higher negative parenting [t (2140.82) = 3.91, p < 0.001, d = 0.17]. No study variables differed across parent gender.

We then examined whether missingness in study variables was associated with demographic characteristics. The families who did not fill out the CBCL (resulting in missingness for internalizing and externalizing behaviors) tended to also report lower income [t (158.42) = − 2.70, p = 0.008, d = − 0.24] and parent education [t (157.80) = − 3.98, p < 0.001, d = − 0.36]. Similarly, the parents with missingness in dispositional mindfulness tended to report low education [t (331.68) = − 6.91, p < 0.001, d = − 0.47] and income [t (337.14) = −4.87, p < .001, d = −0.32]. The parents who did not fill out the MAPS measure (resulting in missingness in positive and negative parenting) had fewer years of education than those who completed the measure [t (73.82) = −2.63, p = 0.010, d = − 0.31].

Model Building and Direct Effects

The proposed model fit well to the data (χ2 (4) = 7.99, p = .092; RMSEA = 0.03 (90% CI = 0.00, 0.06); CFI = 0.999; SRMR = 0.007). A series of nested model comparisons were conducted to build the most parsimonious model possible. First, we removed the direct paths from parent dispositional mindfulness to internalizing and externalizing behaviors. The model fit was not worse after this constraint (Δ χ2 (4) = 3.34, p = 0.50). Next, we constrained the direct paths from mindful parenting to internalizing and externalizing behaviors to be 0. Such constraints did not change the model fit (Δ χ2 (4) = 7.15, p = 0.12). Therefore, these paths were trimmed from the final model. The following model comparison showed that the paths from dispositional mindfulness to positive and negative parenting practices were different from 0 and needed to be kept in the final model (Δ χ2 (4) = 185.25, p < 0.001). Similarly, the paths from dispositional mindfulness to parenting (Δ χ2 (2) = 65.12, p < 0.001) remained in the final model.

The final model fits well to the data (χ2 (12) = 18.51, p = 0.101; RMSEA = 0.02 (90% CI = 0.00, 0.04); CFI = 0.997; SRMR = 0.012). Standardized direct path estimates for mothers and fathers in the final model are shown in Fig. 1. As expected, parent dispositional mindfulness was positively associated with mindful parenting for both mothers and fathers. Results of the chi-square difference test showed that constraining this regression coefficient being equal across mothers and fathers did not worsen the model fit (Δ χ2 (1) = 1.76, p = 0.18). The association between dispositional mindfulness and mindful parenting tended to be stronger for mothers. Mothers’ and fathers’ dispositional mindfulness was positively associated with positive parenting practices and negatively associated negative parenting practices (Δ χ2 (1) = 0.52, p = 0.47 for positive parenting; Δ χ2 (1) = 0.51, p = 0.47 for negative parenting). Mothers’ and fathers’ mindful parenting was positively associated only with positive parenting practices. Mindful parenting was not significantly associated with negative parenting practices for either mothers or fathers. Mindful parenting was equally predictive of parenting practices for mothers and fathers (Δ χ2 (1) = 0.01, p = 0.91 for positive parenting; Δ χ2 (1) = 0.04, p = 0.83 for negative parenting). Higher levels of mothers’ and fathers’ positive parenting practices were predictive of lower levels of child internalizing and externalizing behaviors, whereas higher levels of mothers’ and fathers’ negative parenting practices were predictive of higher levels of child internalizing and externalizing behaviors. The association between negative parenting practices and externalizing behaviors was stronger for mothers (Δ χ2 (1) = 5.71, p = 0.017), whereas the other links were not different across parent gender (Δ χ2 (1) = 0.03, p = 0.86) for positive parenting to externalizing behaviors; Δ χ2 (1) = 0.01, p = 0.93 for negative parenting to internalizing behavior; Δ χ2 (1) = 0.02, p = 0.36 for positive parenting to internalizing behaviors).

Indirect Effects

As shown in Table 2, higher levels of parent dispositional mindfulness were indirectly associated with higher levels of positive parenting through a higher level of mindful parenting. The indirect effect between dispositional mindfulness and negative parenting practices through mindful parenting was not significant. Mindful parenting was negatively associated with internalizing and externalizing behaviors through increased levels of positive parenting practices, but not through negative parenting practices. As expected, the indirect effect of dispositional mindfulness on child internalizing and externalizing behaviors through mindful parenting and subsequent positive parenting was significantly different from 0 (b = − 0.04, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [− 0.06, − 0.02] for child internalizing behaviors; b = − 0.04, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [− 0.06, − 0.02] for child externalizing behaviors).

Discussion

Given the possible differences in parenting processing (e.g., mindful parenting and parenting practices) between Western and Eastern cultures, the current study aimed to replicate the model proposed by Parent et al. (2016) using a sample of Mainland Chinese families to determine if similar effects would be observed in a Chinese cultural context.

The present model suggests that the increases in parents’ dispositional mindfulness are negatively associated with children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms through mindful parenting and subsequent parenting practices. In addition, this study aimed to determine if parents’ gender influenced child outcomes. We hypothesized that parents’ dispositional mindfulness would be positively associated with mindful parenting which, in turn, would be associated with greater positive parenting practices and fewer negative parenting practices. We also hypothesized that positive parenting practices would be associated with decreases in child internalizing and externalizing behaviors, while negative parenting practices would be associated with increases in child internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Finally, we hypothesized that our findings would replicate those found by Parent et al. (2016), such that parent dispositional mindfulness would have a negative indirect effect on children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors through an increase in mindful parenting and positive parenting practices, as well as a decrease in negative parenting practices.

The current study produced mixed results in replicating the findings of the original study conducted in a Western cultural context. Our findings were consistent in that parents’ dispositional mindfulness was associated with mindful parenting, and negative parenting practices were related to child internalizing and externalizing symptoms. In the Chinese sample, parents’ dispositional mindfulness was also associated with positive parenting practices, such that parents with higher levels of dispositional mindfulness reported greater use of positive parenting practices. In addition, higher levels of positive parenting were also associated with decreases in child internalizing and externalizing behaviors. While all pathways were significant in the original Western sample, the relationship between parents’ mindful parenting and negative parenting practices in the current study was not significant. These results indicate that for Chinese parents, mindful parenting was more effective on parents’ positive behaviors such as positive reinforcement, warmth, and supportiveness for children rather than negative parenting practices.

In the current study, we created separate models for mothers and fathers to explore gender differences in mindful parenting. The results indicate that parents’ dispositional mindfulness was associated with mindful parenting for both mothers and fathers, but this link was stronger for mothers. This association was, in turn, linked to only positive parenting practices in both mothers and fathers. In the final component of the model, positive and negative parenting practices were associated with child internalizing and externalizing behaviors regardless of parent’s gender. Specifically, positive parenting was directly related to decreases in children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors, whereas negative parenting was directly related to increases in children’s behaviors. These results were consistent with Western findings (Jones et al. 2008; McKee et al. 2018). In addition, the association between negative parenting practices and increased child behaviors suggests that hostile (i.e., overcontrolling), harsh (i.e., yelling and threatening), and the use of physical control (i.e., physical discipline) may have more implications for externalizing behaviors. This relationship was accentuated in a mother-child relationship, such that the above traits were more strongly associated with increases in child behaviors when observed in the sample of mothers as compared to fathers.

Our findings provide initial evidence for the importance of mindfulness in parent-child relationship, as there are clear benefits to being present-focused and attentive ar the moment when interacting with children. The integration of mindfulness skills and parenting practices can increase parents’ positive interactions with children, as modeling these positive behaviors (i.e., self-regulation and providing direct attention) and exhibiting fewer negative behaviors (i.e., corporal punishment and dysregulation while angry) can likely lead to improvements in children’s own behaviors. Consequently, the reduction of negative parenting behaviors may, in turn, be associated with reductions in internalizing and externalizing behaviors among children.

Limitations

There are several limitations of our study that should be noted. First, a clear limitation is that temporal order cannot definitively be established based on cross-sectional analyses as used in this study. The use of a cross-sectional design to test mediation seriously limits the reliability of the findings because cross-sectional data often lead to biased estimates when compared to longitudinal data (Maxwell and Cole 2007). Future research should use longitudinal data, preferably with at least three separate measurements across time to assess not only the amount of change (which can be assessed with two measurements) but also the rate of change (i.e., developmental trajectory) which can be assessed only with three or more well-spaced measurements. Second, our sample was restricted to parents of children ages 6 to 12; future research should incorporate additional developmental time points to determine the extent to which these findings are consistent across different age groups. Moreover, clinical samples should be considered for more targeted intervention programs. Third, our study may be subject to common method bias, which is a well-documented phenomenon observed in research based on self-reported measures (Lindell and Whitney 2001). Measuring multiple constructs using common methods (e.g., multiple-item scales presented within the same survey) often leads to spurious effects due to the measurement instruments than to the constructs being measured (Podsakoff et al. 2003). For example, spurious rather than true correlations among the constructs being measured may result from response styles, social desirability, and priming effects. Future research can avoid common methods bias using multiple methods or instruments. Despite these limitations, the current study extends our understanding of potential mechanisms that could account for the relationship between parent dispositional mindfulness and child internalizing and externalizing behaviors in one Eastern population.

References

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR, and TRF profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families.

Achenbach, T. M., Mcconaughy, S. H., Ivanova, M. Y., & Rescorla, L. A. (2011). Manual for the ASEBA brief problem monitor (bpm/6). Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., & Allen, K. B. (2004). Assessment of mindfulness by self-report: the Kentucky inventory of mindfulness skills. Assessment, 11, 191–206.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., & William, J. M. G. (2008). Construct validity of the five-facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15, 329–342.

Baharudin, R., Krauss, S. E., Yacoob, S. N., & Pei, T. J. (2011). Family processes as predictors of antisocial behaviors among adolescents from urban, single-mother Malay families in Malaysia. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 42, 509–522.

Barkley, R. A., Fischer, M., Smallish, L., & Fletcher, K. (2006). Young adult outcome of hyperactive children: adaptive functioning in major life activities. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 45, 192–202.

Bazzano, A., Wolfe, C., Zylowska, L., Wang, S., Schuster, E., Barrett, C., & Lehrer, D. (2015). Mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR) for parents and caregivers of individuals with developmental disabilities: a community-based approach. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 298–308.

Beaujean, A. A. (2012). Latent variable modeling using R. New York: Routledge.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychology Bulletin, 107, 256–259.

Bishop, S., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N., Carmody, J., et al. (2004). Mindfulness: a proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 230–241.

Bögels, S., & Restifo, K. (2014). Mindful parenting: a guide for mental health practitioners. New York: Springer.

Bögels, S., Hellemans, J., van Deursen, S., Römer, M., & van der Meulen, R. (2013). Mindful parenting in mental health care: effects on parental and child psychopathology, parental stress, parenting, coparenting, and marital functioning. Mindfulness, 5, 536–551.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822–848.

Brown, K. W., Ryan, R. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2007). Addressing fundamental questions about mindfulness. Psychological Inquiry, 18(4), 272–281.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 21, 230–258.

Chen, X., Liu, M., & Li, D. (2000). Parental warmth, control, and indulgence and their relations to adjustment in Chinese children: a longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology, 14, 401–419.

Coatsworth, J. D., Duncan, L. G., Nix, R. L., Greenberg, M. T., Gayles, J. G., Bamberger, K. T., et al. (2015). Integrating mindfulness with parent training: effects of the mindfulness-enhanced strengthening families program. Developmental Psychology, 51(1), 26–35.

de Bruin, E. I., Zijlstra, B. J., Geurtzen, N., van Zundert, R. M., Van, d. W. E., Hartman, E. E., et al. (2014). Mindful parenting assessed further: psychometric properties of the Dutch version of the interpersonal mindfulness in parenting scale (IM-P). Mindfulness, 5, 200–212.

Deng, Y. Q., & Xia, C. Y. (2011). The five-facet mindfulness questionnaire: psychometric properties of the Chinese version. Mindfulness, 2, 123–128.

Duncan, L. G., Coatsworth, J. D., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). A model of mindful parenting: implications for parent–child relationships and prevention research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12, 255–270.

Friedlmeier, W., Corapci, F., & Cole, P. M. (2011). Emotion socialization in cross-cultural perspective. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5, 410–427.

Geurtzen, N., Scholte, R. H. J., Engels, R. C. M. E., Tak, Y. R., & Zundert, R. M. P. V. (2015). Association between mindful parenting and adolescents’ internalizing problems: non-judgmental acceptance of parenting as core element. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 1117–1128.

Goldberg, S. B., Tucker, R. P., Greene, P. A., Davidson, R. J., Wampold, B. E., Kearney, D. J., & Simpson, T. L. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 59, 52–60.

Gouveia, M. J., Carona, C., Canavarro, M. C., & Moreira, H. (2016). Self-compassion and dispositional mindfulness are associated with parenting styles and parenting stress: the mediating role of mindful parenting. Mindfulness, 7, 700–712.

Harold, G. T., Elam, K. K., Lewis, G., Rice, F., & Thapar, A. (2012). Interparental conflict, parent psychopathology, hostile parenting, and child antisocial behavior: examining the role of maternal versus paternal influences using a novel genetically sensitive research design. Development and Psychopathology, 24, 1283–1295.

Haydicky, J., Shecter, C., Wiener, J., & Ducharme, J. M. (2015). Evaluation of mbct for adolescents with ADHD and their parents: impact on individual and family functioning. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 76–94.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture and organizations. International Studies of Management and Organization, 10, 15–41.

Jones, D. J., Forehand, R., Rakow, A., Colletti, C., McKee, L., & Zalot, A. (2008). The specificity of maternal parenting behavior and child adjustment difficulties: a study of inner-city African American families. Journal of Family Psychology, 22, 181–192.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 144–156.

Kabat-Zinn, M., & Kabat-Zinn, J. (1997). Everyday blessings: the inner work of mindful parenting. New York: Hyperion.

Kawabata, Y., Alink, L. R. A., Tseng, W. L., Ijzendoorn, M. H. V., & Crick, N. R. (2011). Maternal and paternal parenting styles associated with relational aggression in children and adolescents: a conceptual analysis and meta-analytic review. Developmental Review, 31, 240–278.

Keng, S. L., Smoski, M. J., & Robins, C. J. (2011). Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: a review of empirical studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 31, 1041–1056.

Klimes-Dougan, B., Brand, A. E., Zahn-Waxler, C., Usher, B., Hastings, P. D., Kendziora, K., et al. (2010). Parental emotion socialization in adolescence: differences in sex, age and problem status. Social Development, 16, 326–342.

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). New York: Guildford.

Leung, K., Lau, S., & Lam, W. L. (1998). Parenting styles and academic achievement: a cross-cultural study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 44, 157–172.

Lin, X., Li, L., Chi, P., Wang, Z., Heath, M. A., Du, H., & Fang, X. (2016). Child maltreatment and interpersonal relationship among Chinese children with oppositional defiant disorder. Child Abuse and Neglect, 51, 192–202.

Lindblom, J., Vänskä, M., Flykt, M., Tolvanen, A., Tiitinen, A., Tulppala, M., & Punamäki, R.-L. (2017). From early family systems to internalizing symptoms: the role of emotion regulation and peer relations. Journal of Family Psychology, 31, 316–326.

Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 114–121.

Lo, H. H. M., Yeung, J. W. K., Duncan, L. G., Ma, Y., Siu, A. F. Y., Chan, S. K. C., et al. (2018). Validating of the interpersonal mindfulness in parenting scale in Hong Kong Chinese. Mindfulness, 5, 1390–1401.

Maxwell, S. E., & Cole, D. A. (2007). Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods, 12, 23–44.

McKee, L., Parent, J., Zachery, C. R., & Forehand, R. (2018). Mindful parenting and emotion socialization practices: concurrent and longitudinal associations. Family Process, 57, 752–766.

Medeiros, C., Gouveia, M. J., Canavarro, M. C., & Moreira, H. (2016). The indirect effect of the mindful parenting of mothers and fathers on the child’s perceived well-being through the child’s attachment to parents. Mindfulness, 7(4), 916–927.

Moreira, H., & Canavarro, M. C. (2018). The association between self-critical rumination and parenting stress: the mediating role of mindful parenting. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27, 2265–2275.

National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China. (2017). Household report of urban Chinese families. Retrieved from http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/201801/t20180118_1574931.html. Accessed 18 Jan 2018.

Parent, J., & Forehand, R. (2017). The multidimensional assessment of parenting scale (MAPS): development and psychometric properties. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(8), 2136–2151.

Parent, J., Garai, E., Forehand, R., Roland, E., Champion, J. E., Haker, K., Hardcastle, E. J., & Compas, B. E. (2010). Parent mindfulness and child outcome: The roles of parent depressive symptoms and parenting. Mindfulness, 1, 254–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-010-0034-1.

Parent, J., McKee, L. G., Rough, J. N., & Forehand, R. (2016). The association of parent mindfulness with parenting and youth psychopathology across three developmental stages. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44, 191–202.

Pepping, C., O’Donovan, A., & Davis, P. (2013). The positive effects of mindfulness on self-esteem. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 8, 376–386.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36.

RStudio Team. (2015). RStudio: integrated development for R. RStudio, Inc. Boston: Author.

Satorra, A. (2000). Scaled and adjusted restricted tests in multi-sample analysis of moment structures. Adv. Stud. Theoret. Appl. Econometrics, 36, 233–247.

Siu, A. F. Y., Ma, Y., & Chui, F. W. Y. (2016). Maternal mindfulness and child social behavior: the mediating role of the mother-child relationship. Mindfulness, 7, 577–583.

Smith, J. D., & Dishion, T. J. (2013). Mindful parenting in the development and maintenance of youth psychopathology. In J. T. Ehrenreich-May & B. C. Chu (Eds.), Transdiagnostic mechanisms and treatment for youth psychopathology (pp. 138–160). New York: Guilford Press.

Steiger, J. H. (1990). Structural model evaluation and modification: an interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 25, 173–180.

Wang, G., Liu, L., Tan, X., & Zheng, W. (2017). The moderating effect of dispositional mindfulness on the relationship between materialism and mental health. Personality and Individual Differences, 107, 131–136.

Williams, K. L., & Wahler, R. G. (2010). Are mindful parents more authoritative and less authoritarian? an analysis of clinic-referred mothers. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19, 230–235.

Xu, Y., Zhang, L., & Hee, P. (2014). Parenting practices and shyness in Chinese children. In H. Selin (Ed.), Parenting across cultures: child rearing, motherhood and fatherhood in non-western cultures (pp. 13–24). New York: Springer.

Yan, J., Han, Z. R., Tang, Y., & Zhang, X. (2017). Parental support for autonomy and child depressive symptoms in middle childhood: The mediating role of parent–child attachment. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26, 1970–1978.

Yap, M. B., & Jorm, A. F. (2015). Parental factors associated with childhood anxiety, depression, and internalizing problems: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 175, 424–440.

Funding

This research was supported by the 2019 Comprehensive Discipline Construction Fund of Faculty of Education, Beijing Normal University, and the Funding of International Center for Educational Research, ICER, Faculty of Education, Beijing Normal University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZRH: designed and executed the study, and drafted the manuscript. NA: collected data and drafted the manuscript. JY: analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. XH: assisted with the writing and editing of the manuscript. JP: designed the study, helped with data analysis, and edited the manuscript.CD and KD: drafted the manuscript. NNS: designed the study, helped with data analysis, and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Beijing University Institutional Research Board (IRB) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

OpenAccess This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, Z.R., Ahemaitijiang, N., Yan, J. et al. Parent Mindfulness, Parenting, and Child Psychopathology in China. Mindfulness 12, 334–343 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01111-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01111-z