Abstract

This paper offers a new analysis of Russian syntactic idioms consisting of stressed general negation n´e- fused with a wh-word (k-word). The elements from this class take infinitival complements and select dative subjects. The clauses with Russian neg-words like mne negde spat’ ‘I have no space to sleep’ and their affirmative counterparts represent the modal existential construction conveying the meaning ‘p is (not) available & X can (not) do q’. I argue that while the perspective of checking Russian modal existentials on a class of embedded wh-infinitives is important, it must be complemented by a comparison of idioms of the mne negde spat’ type with two productive sentence patterns—dative-predicative and dative-infinitive structures. The former are control structures, where dative subjects are matrix clause elements, while the latter have raising properties. Syntactic idioms display mixed properties: on the one hand, they match the overt syntax of dative predicatives, on the other hand, show residual raising effects and license derived non-animate subjects. Like root dative-infinitive structures, syntactic idioms express the meaning of external (alethic) modality, but the same type of modality can be expressed by some dative predicatives. The clauses with neg-words originated as embedded dative-infinitive structures, a type marginally acceptable in Modern Russian, while the dative-predicative construction extends its coverage and assimilates neg-words. The neg-words are derived by the movement of k-words into the matrix clause. If a case-marked k-word raises to a non-argument position, it loses morphological case and the neg-word is reanalyzed as a predicative. If a case-marked k-word raises to the subject position, the neg-word inherits the case of the k-word, which is possible only for dative k-words komu and čemu.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Except for the prepositions splitting the oblique forms of nekto, nečto, сf. *uPREP nekogoGEN otprašivat’sjaINF ‘to ask anybody for leave’ ⇒ neNEG uPREP kogoGEN otprašivat’sja ‘<X> has no one to ask for leave’. Split oblique forms of indefinites with koe- (u, koe-kakoj ⇒ koe u kakogo) and non-predicative negatives with ni- (u, nikto ⇒ ni u kogo) are a well-known feature of Modern East Slavic. The splitting of koe-indefinites and ni-negatives can be interpreted as endoclisis, since koe- and ni- lack word properties (Arkadiev, 2016). For Russian neg-words, an endoclitic analysis depends on the assumption that ne- is a standard prefix.

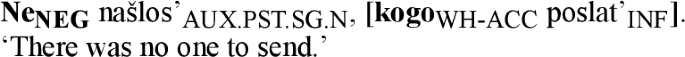

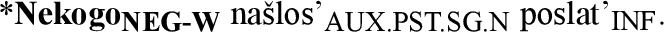

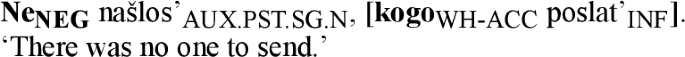

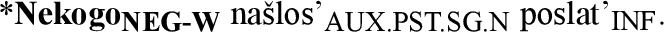

The copular forms of byt’ occasionally alternate with semi-content verbs stat’, okazat’sja, delat’sja marking the change of state (Apresjan & Iomdin, 2010, pp. 92–94). Apresjan & Iomdin also mention najtis’ ‘show up’, but it is licensed only with distant negation, cf. (i), not with neg-words, cf. (ii).

-

(i)

-

(ii)

Fortuin (2014, pp. 32, 52) provides several examples with najdetsja intervening between ne and the k-word.

-

(i)

Colloquial Russian occasionally licenses dropping li in the context of net, e.g., Net

? Such sentences express the meaning ‘p or ∼ p’ with an additional flavor, ca. ‘You have something to drink, right?’.

? Such sentences express the meaning ‘p or ∼ p’ with an additional flavor, ca. ‘You have something to drink, right?’.The non-present forms byt’ are two-way ambiguous between copular vs content-verb uses. The overt present tense form est’BE.PRES has pragmatically marked copular uses in bi-nominative sentences like VasjaNOM.SG i est’BE.PRES naš načal’nikNOM.SG ‘Bazil is indeed our boss’, ÈkzistencializmNOM.SG est’BE.PRES gumanizmNOM.SG ‘Existentialism is <the same thing as> humanism’, but such patterns do not occur in Russian MEC.

The plural form ‘MECs’ stands for ‘MEC sentences’.

The contrast between Šimík’s and Fortuin’s accounts is not radical: neither of them claims that the inherent lexical meaning of the existential verb remains unmodified in MEC. The former stipulates that BE and HAVE only bring about modal meanings in a group of contexts including MEC but not in other cases, e.g., a sentence of the type ‘X has Y’ is not modal. The latter argues that the “modality of EC is an interpretation, which is contextually determined, rather than a meaning expressed by a form” (Fortuin, 2014, p. 55).

The last part of Peškovskij’s point does not apply to adverbial neg-words like negde.

A similar analysis has been outlined by Paducheva (2017), who claims that structures with lowered, i.e., lexically bound negation lack semantic interpretation.

Šimík’s thesis (2011) seems to be the only work in the field that includes an annotated bibliography.

The label ‘Tense’ is not used in Apresjan and Iomdin (2010) but is a generalization over specific tags used by them in the annotation of dependency trees on pp. 78–80.

Generative scholars usually treat the orders like #…wh …Inf as derived even if the wh-element is not fronted to the clausal left periphery.

Avgustinova (2003) and Kondrashova and Šimík (2013, Sect. 4.2.) ascribe to Apresjan & Iomdin the idea that neg-words are assembled before syntactic derivation, but that is merely a framework-internal issue. The Meaning-Text Theory used by Apresjan & Iomdin lacks morphological rules that are applied post-syntactically or parallel with syntactic operations.

Apresjan & Iomdin’s analysis of neg-words is implemented in the deep annotation of SynTagRus corpus, which is part of the Russian National Corpus (RNC) and the Universal Dependencies project.

There are borderline cases like <Grustno>, i nekomuNEG-W1 ne o čemNEG-W1 pisat’ ‘<I am sad>, and I have no one and nothing to write about’, but generally Russian speakers avoid combining two neg-words without a conjunction. An anonymous reviewer points out that the assumption that all coordinate structures are bi-clausal is not shared by all linguists.

Kondrashova & Šimík take for granted that the word нет is a contraction of *не есть.

In this pair of examples, the form of the perfective infinitive (vyexat’) contributes to selecting an alethic reading of nel’zja ‘cannot’ or ‘must not’ or ‘it is forbidden’. However, the perfective form does not force an alethic reading and the imperfective form does not force a deontic/normative reading, since many contexts are ambiguous. E.g., the sentences EmuDAT.3SG.M nadoPRED byloAUX.PST.3SG.N uexat’INF.PERF / uezžat’INF.IMPERF are compatible both with the reading ‘Еxternal Force caused him to leave, and he left’, cf. Emu nado bylo uexat’/ uezžat’, i on uexal’, and with the reading ‘He had to/was obliged to leave, but he stayed’, cf. Emu nado bylo uexat’ / uezžat’, no on ostalsja. A preliminary generalization over Russian DPS sentences is that the type of modality is not established in the embedded infinitival clause.

The genitive case form in nečego1 pit’ is a standard modification of the accusative object pit’ čto-toACC in the context of negation.

An anonymous reviewer wonders whether the ungrammaticality of (20b) could be alternatively explained by the absence of the head assigning GEN to čego. This explanation does not work, since the k-word čego is licensed in the affirmative MEC sentences, cf. est’ čego prokrutit’ ‘there is something to twist’ (RNC, 2007), est’ čego axat’, lit. ‘there is something to groan / gasp at’ (RNC, 1880). The same holds for wh-questions, cf. Čego tut axat’? ‘Why groan here?’

For the discussion of case loss see Sect. 3.4. below. Note that the frozen genitive ending inherited from the k-word čego is present both in nečego1 and in nečego2.

The lexical homonymy of the hybrid nečego1 vs. modal nečego2 is easier to explain in the accounts, where neg-words are formed before syntactic derivation, cf. Rappaport (1986) or the Meaning-Text-Theory. With the derivational analysis adopted in this paper one can assume that the modal nečego2 is merged higher than the hybrid nečego1. I am grateful to the anonymous reviewer for the suggestion.

Cf. a late example: Raz ètomu oluxuDAT.SG.M nevdomekPRED raznicaNOM.SG.F meždu Zemlej i asteroidom... ‘Since this idiot cannot make out the difference between Earth and an asteroid…’ (RNC, 1967).

Russian National Corpus: https://ruscorpora.ru/ [Date of access: 24.08.2022].

The processing of ipm values for all Russian neg-words including the low frequent ones is a feasible but difficult task that requires a larger corpus than RNC.

A possible objection is that the raising verbs najtis’, okazat’sja or stat’ do not discriminate animacy of the embedded clause arguments, cf. EmuDAT.3SGANIM okazalos’AUX.PST.3SG.N nekudaNEG-W klast’INF sumku ‘It turned out that he had to place to put the bag’. It is therefore better to explain the raising of the inanimate dative arguments by the internal syntax of Russian neg-words, and not by the type of the copula they combine.

Cf. a similar proposal by Gerasimova (2015).

An anonymous reviewer provides another argument against treating obligatory animate dative subjects as external arguments of neg-words: the negation takes the proposition as its argument, not an individual. I assume that sentences with Russian neg-words undergo restructuring, with reanalysis of the complex ne2 + k-word as a new syntactic head NEG-W0. In terms of dependency grammar, the higher dative (DAT1) is the dependency of the NEG-W0 head. In terms of generalized phrase structure grammar, it can be located at SpecNP, though this step needs justification.

Note that the restriction on the simultaneous filling of DAT1 and DAT2 shown in (28a) holds because both dative arguments are subject-like, while the prepositional genitive u menja in (28b) is not. There are numerous proposals for postulating genitive and accusative subjects, such as the u + GEN construction for Russian. In this paper, I treat ‘subject’ as a structural, not as a functional or semantic notion. In sentences like U SergejaGEN.PREP bylAUX.PST.3SG.M grippNOM.SG.M ‘S. had flu’ the nominative NP controls the number and gender form of the predicate, and I do not see an obvious way to treat this NP as nominative object, not as subject, since nominative objects are banned in Standard Russian, cf. *mneDAT.1SG nužno byloAUX.PST.3SG.N [NP lekarstva ot grippa]NOM.PL.

Russian ni-negatives are NPI items that must be licensed by an overt negative head like nel’zja: nel’zja0 podobrat’INF [NiP nikogo drugogo], nel’zja0 ostanovit’ ix [NiP ni na čem drugom].

RNC has 158 DIS sentences with nečemu in the subject position, 146 of which have intransitive verbs. The sample with nečemu in the predicative position with DAT slot filled by another expression is smaller—100 sentences, all of which have + ANIM subjects and transitive verbs.

The raising of nekomu to the subject position is blocked, if it is an internal argument of the (semi) transitive verb with a dative slot. Cf. verit’ komu-l. i čemu-l. ‘to trust someone or something’: Tut nekomu i nečemu verit’ ‘There is no one and nothing to trust here.’ (RNC, Alexander Zinoviev, 1995) = Tut ((nekomu verit’) & (nečemu verit’)).

There is another approach to the control vs raising distinction, whereby all modal verbs are considered raising predicates that take their subjects from embedded clauses. It is less convenient for our purpose since it does not capture the restructuring effects and the contrast between alethic and deontic modals.

It is possible to analyze (42) as a control structure with Izjaslavu generated in the matrix clause. However, one has to take into account the difference in semantics between Old Russian matrix clause dative constructions and presumably raising constructions with a dative argument. The first group includes DIS sentences with an obligatory animate subject and a modal meaning—usually alethic (im)possibility, but also wish, prescription, command or prohibition, cf. GrigorijuDAT.3G goroditiINF peregorodaNOM.F zaovinnajaNOM.F ‘Gregory has to raise the fence behind the barn’. They do not express statements. The second group includes embedded infinitive clauses with an external head, the dative argument does not discriminate animacy. Here, Izjaslav is animate, but the same structure can be built with an inanimate noun zolotu. (42) is a statement: the speaker (Prince Vladimir) assumes that his enemy Izjaslav is not in the mountains and asserts that there is no place for him to be there.

It is expected that situations where X reproaches oneself are less usual than situations where X reproaches Y.

43 928 documents, 98 023 229 words (24.08.2022).

In standard Modern Russian, možno (\(\lozenge\) p) and nel’zja (∼ \(\lozenge\) p) make up a pair. The positive form *l’zja ‘allowed’ is lost, while the negative combination ne možno ‘not allowed’ is non-standard and survives only as a quotation from XIX century Russian (41 hits in RNS).

Abbreviations

- ACC:

-

Accusative

- ADJ:

-

Adjective

- AUX:

-

Auxiliary

- CP:

-

Complement Phrase

- DAT:

-

Dative

- DIS:

-

Dative-infinitive-structure

- DPS:

-

Dative-predicative-structure

- FR:

-

Free Relative

- FUT:

-

Future

- GEN:

-

Genitive

- IMPERF:

-

Imperfective

- INDEF:

-

Indefinite

- INF:

-

Infinitive

- InfP:

-

Infinitive Phrase

- INSTR:

-

Instrumental

- K-W:

-

k-word (the merged interrogative component of the predicative neg-word)

- LOC:

-

Locative

- MEC:

-

Modal-existential construction

- NEG:

-

Negation

- NEG-W:

-

neg-word (a predicative complex with a k-word merged with the general negation)

- NEG-WP:

-

Neg-W Phrase (a phrase including a single neg-word)

- NiP:

-

Ni-Phrase (a phrase including a single NPI item with the prefix ni-)

- NOM:

-

Nominative

- NP:

-

Noun Phrase

- NPI:

-

negative polarity item

- OPT:

-

Optative

- PERF:

-

Perfective

- PP:

-

Preposition Phrase

- PRED:

-

Predicative

- PREP:

-

Preposition

- PRES:

-

Present

- PST:

-

Past

- Q:

-

Question

- REC:

-

Reciprocal

- REFL:

-

Reflexive

- TP:

-

Tense Phrase

- VP:

-

Verb Phrase

- WH:

-

wh-element (different from a k-word)

- RNC:

-

Russian National Corpus: https://ruscorpora.ru/ [Date of access: 24.08.2022]

- Hypat:

-

Ipat’evskaja letopis’ (Polnoe sobranie russkix letopisej, II). Moskva 2001

- Theod:

-

Žitie prepodobnago Feodosija, igumena Pečerskago. In A. A. Šaxmatov & P. A. Lavrov (Eds.). (1899), Sbornik XII věka Moskovskago Uspenskago sobora. Moskva

References

Apresjan, J. D. (1996). Leksikografičeskie portrety (na primere glagola byt’). In Integral’noe opisanie jazyka i sistemnaja leksikografija (pp. 503–537). Jazyki slavjanskoj kul’tury.

Apresjan, J. D., & Iomdin, L. L. (1989). Konstrukcija tipa NEGDE SPAT’: sintaksis, semantika, leksikografija. Semiotika i informatika, 29, 34–92.

Apresjan, J. D., & Iomdin, L. L. (2010). Konstrukcija tipa NEGDE SPAT’: sintaksis, semantika, leksikografija. In Ju. D. Apresjan, I. M. Boguslavski, L. L. Iomdin, & V. Z. Sannikov (Eds.), Teoretičeskie problemy russkogo sintaksisa. Vzaimodejstvie grammatiki i slovarja (pp. 59–113). Jazyki slavjanskix kul’tur.

Arkadiev, P. M. (2016). K voprosu ob endoklitikax v russkom jazyke. In A. V. Zimmerling & E. A. Lyutikova (Eds.), Arxitektura klauzy v parametričeskix modeljax: sintaksis, informacionnaja struktura, porjadok slov (pp. 325–331). Jazyki slavjanskoj kul’tury.

Avgustinova, T. (2003). Russian infinitival existential constructions from an HPSG perspective. In P. Kosta, J. Blaszczak, J. Frasek, L. Geist, & M. Zygis (Eds.), Investigations into Formal Slavic Linguistics. Contributions of the Fourth European Conference on Formal Description of Slavic Languages (FDSL IV) (pp. 461–482). Peter Lang.

Babby, L. H. (2000). Infinitival existential sentences in Russian: A case of syntactic suppletion. In T. H. King & I. A. Sekerina (Eds.), Formal Approaches to Slavic Linguistics 8: The Philadelphia Meeting 1999 (pp. 1–21). Michigan Slavic Publications.

Barwise, J., & Cooper, R. (1981). Generalized quantifiers and natural language. Linguistics and Philosophy, 4, 159–219.

Bonč-Osmolovskaja, A. А. (2003). Konstrukcii s dativnym sub’’ektom v russkom jazyke. Phd, Moscow, MSU.

Borkovskij, V. I. (1978). Istoričeskaja grammatika russkogo jazyka. Sintaksis. Prostoe predloženie. Nauka.

Burukina, I. V. (2019). Raising and control in non-finite clausal complementation. Doctoral dissertation, University of Budapest.

Dymarskij, M. J. (2018). A u men’a v karmane gvozd’. Nulevaja sv’azka ili ellipsis skazuemogo? Mir russkogo slova, 3, 5–12.

Ebeling, C. L. (1984). On the meaning of the Russian infinitive. In J. J. Van Baak (Ed.), Signs of Friendship, to Honour Andre G. F. van Holk, Slavist, Linguist, Semiotician (pp. 97–130). Rodopi.

Fleisher, N. (2006). Russian Dative Subjects, Case, and Control. Ms, University of California.

Fortuin, E. L. J. (2005). From necessity to possibility: the modal spectrum of the dative-infinitive construction in Russian. In B. Hansen & P. Karlik (Eds.), Modality in Slavonic Languages. New Perspectives (pp. 39–60). Otto Sagner.

Fortuin, E. L. J. (2007). Modality and aspect: Interaction of constructional meaning and aspectual meaning in the dative-infinitive construction in Russian. Russian Linguistics, 31(3), 201–230.

Fortuin, E. L. I. (2014). The Existential Construction in Russian: a Semantic-Syntactic Approach. In E. Fortuin, H. Houtzagers, J. Kalsbeek, & S. Dekker (Eds.), Dutch Contributions to the Fifteenth International Congress of Slavists: Minsk, August 20–27, 2013. Linguistics (pp. 25–58). Rodopi.

Garde, P. (1976). Analyse de la tournure russe Mne nečego delat’. International Journal of Slavic Linguistics and Poetics, 22, 43–60.

Gerasimova, A. A. (2015). Licenzirovanije otricatel’nyx mestoimenij čerez granicu infinitivnogo oborota v russkom jazyke. In E. A. Lyutikova & A. V. Zimmerling (Eds.), Tipologija morfosintaksičeskix parametrov. Materialy meždunarodnoj konferencii ‘TMP 2015’. Issue 2 (pp. 47–61). MPGU.

Grosu, A. (2004). The syntax-semantics of modal existential wh-constructions. In O. Mišeska Tomić (Ed.), Balkan syntax and semantics (pp. 405–438). John Benjamins.

Hamblin, C. L. (1973). Questions in Montague grammar. Foundations of Language, 10, 41–53.

Haspelmath, M. (1997). Indefinite pronouns. Clarendon Press.

Holthusen, J. (1953). Russisch nečego und Verwandtes. Zeitschrift für Slawische Philologie, 22(1), 156–159.

Isačenko, A. V. (1965). O sintaksičeskoj prirode mestoimenij. In Problemy sovremennoj filologii. Sb. Statej k 70-letijyu akad. V. V. Vinogradova (pp. 159–166). Nauka [Reprinted in: Opera selecta, München: Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 1976, 354–361.]

Israeli, A. (2013). Dative-infinitive constructions in Russian. Taxonomy and semantics. In I. Kor Chahine (Ed.), Contemporary Studies in Slavic Linguistics (pp. 199–224). John Benjamins.

Israeli, A. (2014). Dative-infinitive БЫ constructions in Russian. Taxonomy and semantics. In J. Witkoś & S. Jaworsky (Eds.), New Insights into Slavic Linguistics (pp. 141–159). Peter Lang.

Israeli, A. (2016). Dative-Infinitive Сonstructions with the Particle ЖЕ in Russian: Taxonomy and Semantics. Slavic and East European Journal, 60(2), 308–330.

Ivanova, E., & Zimmerling, A. (2019). Shared by all speakers? Dative Predicatives in Bulgarian and Russian. Bulgarian Language and Literature, 4, 353–363.

Izvorski, R. (1998). Non-indicative wh-complements of possessive and existential predicates. In P. N. Tamanji & K. Kusumoto (Eds.), NELS 28: Proceedings of the 28th Annual Meeting of the North East Linguistic Society (pp. 159–173).

Kalėdaitė, V. (2008). Language-specific existential sentence types. Kalbotyra, 59(3), 128–137.

Khatatneh, A. H. (2020). Modal existential constructions in Modern Standard Arabic. Education and Linguistics Research, 6(1).

Khodova, K. I. (1980). Prostoe predlozhenie v staroslavyanskom jazyke. Nauka.

Kondrashova, N. (2008). Negated wh-items in Russian: Syntactic and semantic puzzles. Presented at the Third Meeting of the Slavic Linguistic Society (SLS), Ohio State University.

Kondrashova, N., & Šimík, R. (2013). Quantificational properties of neg-wh items in Russian. In NELS 40: Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting of the North East Linguistic Society, (pp. 15–28). GLSA Publications.

Kosta, P. (2009). Targets, Theory and Methods of Slavic Generative Syntax: Minimalism, Negation and Clitics. In S. Kempgen, P. Kosta, T. Berger, & K. Gutschmidt (Eds.), Die slavishen Sprachen. The Slavic Languages. An international Handbook of their Structures, their History and their Investigation, (pp. 282–316). Mouton de Gruyter.

Kratzer, A., & Shimoyama, Y. (2002). Indeterminate pronouns: The view from Japanese. In Y. Otsu (Ed.), Proceedings of the Third Tokyo Conference on Psycholinguistics. Hituzi Syobo.

Kustova, G. I. (2021). The types of infinitive constructions with predicatives (according to the Russian National Corpus). In Computational linguistics and intellectual technologies, 20. Proceedings of the international conference “Dialogue 2021” (pp. 456–463).

Letuchiy, A. B. (2018a). Nulevaja sv’azka, Russkaja korpusnaja grammatika [rusgram.ru].

Letuchiy, A. B. (2018b). Predikativ ili prilagatel’noe? Russkie konstrukcii s poluvspomogatel’nymi glagolami i prilagatel’nymi (tipa: ja sčitaju nužnym učastvovat’). Voprosy jazykoznanija, 2, 7–28.

Letuchiy, A. B. (2022). Predikativy v sisteme russkiх priznakovyх slov– narečij i prilagatel’nyx. Vestnik Tomskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Filologija, 76, 105–147.

Letuchiy, A. B., & Viklova, A. V. (2020). Pod’’em i smežnye javlenija v russkom jazyke. Voprosy jazykoznanija, 2, 31–60.

Lyutikova, E. A. (2022a). Est’ li sintaksičeskij pod’’em v russkom jazyke? Čast’ I. Infinitivnye klauzy. Vestnik Moskovskogo universiteta. Filologija, 5, 27–45.

Lyutikova, E. A. (2022b). Est’ li sintaksičeskij pod’’em v russkom jazyke? Čast’ II. Malye klauzy. Vestnik Moskovskogo universiteta. Filologija, 6, 58–74.

Madariaga, N. P. (2011). Infinitive clauses and dative subjects in Russian. Russian Linguistics, 35(3), 301–329.

Mitrenina, O. V. (2017). Dativno-infinitivnaja konstrukcija v russkom jazyke kak predložnaya gruppa. In E. A. Lyutikova & A. V. Zimmerling (Eds.), Tipologiya morfosinkatsicheskih parametrov (Vol. 4, pp. 64–70).

Moore, J., & Perlmutter, D. M. (1999). Case, agreement, and temporal particles in Russian infinitival clauses. Journal of Slavic Linguistics, 7(2), 219–246.

Moore, J., & Perlmutter, D. M. (2000). What does it take to be a dative subject? Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 18, 373–416.

Mrázek, R. (1972). Slav’anskij sintaksičeskij tip “mne nečego čitat’”. In Sborník prací Filosofické fakulty Brněnské university. Studia minora fakultatis philosophicae universitatis brunensis. A 20 (pp. 97–105).

Ožegov, S. I. (1964). Slovar’ russkogo jazyka (6th stereotype ed). Sovetskaja encyclopedija.

Paducheva, E. V. (2017). Otricatel’nye mestoimenija-predikativy (na ne-). http://rusgram.ru/Отрицательные местоимения - предикативы (на не-).

Paducheva, E. V. (2018). Infinitive. http://rusgram.ru/Инфинитив.

Pancheva-Izvorski, R. (2000). Free relatives and related matters. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Penchev, J. (1984). Stroež na bălgarskoto izrečenie. Nauka i izkustvo.

Penchev, J. (1993). Bălgarskijat sintaksis – upravlnie i svărzvane. Plovdivsko universitetsko izdatelstvo.

Penchev, J. (1998). Sintaksis. In T. Bojadjiev, I. Kucarov, & J. Penchev (Eds.), Săvremenen bălgarski ezik (fonetika, leksikologija, morfologija, sintaksis), Sofia (pp. 498–655).

Penkova, J., & Rabus, A. (2021). East Slavic Indefinite Pronouns: a Corpus Approach. Russian Linguistics, 45, 227–252.

Perlmutter, D. M., & Moore, J. (2002). Language-internal explanation: the distribution of Russian Impersonals. Language, 78, 619–650.

Peškovskij, A. M. (1928). Russkij jazyk v naučnom osveščenii (3rd ed.). Gosudarstvennoe izdatel’stvo.

Pospelov, N. S. (1955). V zaščitu kategorii sostojanija. Voprosy jazykoznanija, 2, 55–65.

Rappaport, G. (1986). On a persistent problem of Russian syntax: sentences of the type Mne negde spat’. Russian Linguistics, 10, 1–31.

Rudin, C. (1986). Aspects of Bulgarian syntax: Complementizers and wh-constructions. Slavica Publishers.

Stjepanović, S. (2004). Clitic climbing and restructuring with “finite clause” and infinitive complements. Journal of Slavic Linguistics, 12(1–2), 73–212.

Šimík, R. (2009). Hamblin pronouns in modal existential wh-constructions. In M. Babyonyshev, D. Kavitskaya, & J. Reich (Eds.), Formal Approaches to Slavic Linguistics 17: The Yale Meeting 2008 (pp. 187–202). Michigan Slavic Publications.

Šimík, R. (2011). Modal existential wh-construction. Phd, Groningen.

Švedova, J. N. (1982). Russkaja grammatika (Vols. 1–2). Nauka.

Ščerba, L. V. (1928). Kategorija sostojanija v russkom jazyke. In Russkaja reč. Novaja serija (Vol. II, pp. 5–27). Academia.

Tseitlina, R. M., Večerka, R., & Blahová, E. (1994). Staroslav’anskij slovar’ (po rukopis’am X—XI veka). Russkij jazyk.

Veyrenc, J. (1979). Les propositions infinitives en russe. Institut d’Études Slaves.

Yanovich, I. (2005). Choice-functional series of indefinites and Hamblin semantics. Presented at SALT 15, UCLA.

Zimmerling, A. (2009). Dative Subjects and Semi-Expletive Pronouns in Russian. In G. Zybatow, W. Junghanns, D. Lenertova, & P. Biskup (Eds.), Studies in Formal Slavic Phonology, Morphology, Syntax, Semantics and Discourse Structure (pp. 253–268). Peter Lang.

Zimmerling, A. (2018a). Impersonal’nye konstrukcii i dativno-predikativnye struktury v russkom jazyke. Voprosy jazykoznanija, 5, 7–33.

Zimmerling, A. (2018b). Tak im i nado: nužny li endoklitiki dl’a opisanija russkoj grammatiki. Russkij jazyk v naučnom osveščenii, 36(2), 159–179.

Zimmerling, A. (2020a). Oduševlennost’. Russkij jazyk. Trudy Instituta russkogo jazyka imeni V.V. Vinogradova RAN, 24, 43–56.

Zimmerling, A. (2020b). Avtoreferentnost’ i klassy predikativnyx slov. In M. D. Voeikova & V. V. Kazakovskaja (Eds.), Problemy funkcional’noj grammatiki: Otnošenie k govorjaščemu v semantike grammatičeskix kategorij (pp. 23–58). Jazyki slavjanskoj kul’tury.

Zimmerling, A. (2021a). Ot integral’nogo k aspektivnomu. Jazyki slavjanskoj kul’tury.

Zimmerling, A. (2021b). Primary and secondary predication in Russian and the SLP: ILP distinction revisited. In V. Warditz (Ed.), Russian Grammar: System – Language Usage – Language Variation (pp. 543–560). Peter Lang.

Zimmerling, A. (2022). Existentials, modals and the ontology of states. In Dokladi ot meždunarodnata godišna konferencija na Instituta za bălgarski ezik “Profesor Lubomir Andreičin” (pp. 57–66). Izdatelstvo na BAN „Prof. Marin Drinov”.

Zubatý, J. (1922). Mám co dĕlati. Naše řeč, 6, 65–71.

Žolobov, O. F. (2016). Zametki o slovoforme е ‛jest’’ v drevnerusskoj i staroslavjanskoj pis’mennosti. Slověne. International Journal of Slavic Studies, 1, 114–125.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the anonymous reviewers for the valuable critical comments and discussion. The sole responsibility for all shortcomings is mine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zimmerling, A. Microsyntax meets macrosyntax: Russian neg-words revisited. Russ Linguist 48, 6 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-024-09290-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-024-09290-7

? Such sentences express the meaning ‘p or ∼ p’ with an additional flavor, ca. ‘You have something to drink, right?’.

? Such sentences express the meaning ‘p or ∼ p’ with an additional flavor, ca. ‘You have something to drink, right?’.