Abstract

The paper focuses on the development and functional distribution of indefinite pronouns in Old East Slavic, taking into account different sources, genres and registers. All the examples in the collected dataset were taken from the historical modules of the Russian National Corpus. They were tagged for type of indefinite marker, source (including originality and date), type of reference of the indefinite marker, semantics, type of discourse, and the degree of formality (formal or informal) present in the context. We then applied both descriptive and inferential statistical methods such as Random Forest analysis as well as multinomial logistic regression. Our analysis enabled us to identify the primary and secondary predictors of the choice of a particular indefinite marker and to trace the functional distribution of indefinite markers according to these factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction and overview of indefinite markers in the history of Russian

The present paper discusses indefinite pronouns in Old East Slavic (OES). The initial system of OES indefinites differed significantly from that of modern Russian. The system presented in the oldest OES written sources featured relatively few distinctions. It included only interrogatives in the function of indefinites (1–2), a function they can still have in modern colloquial Russian, the ně-prefixed pronouns (3), and quasi-relative constructions based on the predicative adjective ljubo, with the original meaning of ‘pleasing’ (4), that were used as indefinites (Krys’ ko et al., 2020, p. 178‒183).

-

(1)

ты ко мнѣ при|шли а не угодице с кымъ п|рислать и ты у себѧ избѣ|ли

‘send [it] to me, and if sending it with someone doesn’t work out (lit.: if it doesn’t work out to send [it] with someone), whiten [it] by yourself’ (Birchbark letter 21; ca. 1410–1420)Footnote 1

-

(2)

аже возможеши пособлѧi мнѣ цимо

‘if you can, help me with something’ (Birchbark letter 286; ca. 1360–1380)

-

(3)

пъвели нѣкъмѹ ѿ ѹцинѧ[ть] […] жемецюженѣ окънъ быше стрѣ[лъкы]

‘command someone to make pearl [jewelry] like arrows’ (Birchbark letter 809, ca. 1160–1180)

-

(4)

ѿ рьмьшѣ покланѧнье къ климѧ(тѣ) и къ павьл[

] ∙б҃∙ дѣлѧ котореи любо потрѹдисѧ до владычѣ съка(ж)ита владычѣ мою обидѹ

] ∙б҃∙ дѣлѧ котореи любо потрѹдисѧ до владычѣ съка(ж)ита владычѣ мою обидѹ‘Rьmьša bows (lit.: a bow from Rьmьša) to Klimjata and Pavel: for God’s sake, anyone, reach the master, tell the master my complaint’ (Birchbark letter 725, ca. 1180–1200)

The only indefinite marker that has survived in Standard Russian up to the present day – albeit with certain formal, semantic and syntactic changes (cf. 3) – is the prefix нe- < ně (modern Russian некто, нечто, некий < OES нѣкъто, нѣчьто, нѣкыи):

-

(5)

Modern Russian: Атаманом этой банды был некий Гавриленко, который называл себя «учеником самого князя Кропоткина»

‘The ataman of this gang was a certain Gavrilenko, who called himself “a disciple of Prince Kropotkin”.’ (D. Granin: Zubr (1987), Padučeva, 2016)

The earliest attestations of the particle libo, a marker of negative polarity indefinites in Modern Russian (Padučeva, 2015), date back to the late 13th century, when it began to replace the particle ljubo (Krys’ ko et al., 2020, p. 183; for more on modern Russian quasi-relative constructions as a final stage in the evolution of original subordinate clauses, see Kustova, 2015):

-

(6)

аще убо отнынѣ кровь животнаго кимь либо образомь ясти начнеть […] да извержется

‘if from this day [he] begins to eat animal blood in any way […], let him be cast out’ (Riazanskaja kormčaja 1284, SDRJa 4, 401)

All the indefinite markers mentioned above are attested in texts belonging to both high-variety genres (so-called Standard Church Slavonic) and Hybrid Church Slavonic texts (for more on Hybrid and Standard Church Slavonic see Živov, 2017, p. 205‒314), as well as in vernacular OES sources, i.e., in the birchbark letters. However, there are only three attestations of ně-indefinites in the Novgorod birchbark letters with vernacular spelling, according to the RNC. Malovickij (1971, p. 70) claims that ně-indefinites were borrowed in OES from OCS since they predominantly occur in Church Slavonic sources. Another indefinite marker also borrowed from OCS but not mentioned by Malovickij is the pronoun eter-. It could be used as a marker of indefiniteness exclusively in the high-code texts (Krys’ ko et al., 2020, p. 179), cf. (7).

-

(7)

изидоша же ѿ воинъ ѥтери хотѧще трѣбовани

брашьнѹ обрѣсти

брашьнѹ обрѣсти‘some of the warriors came out wishing to find the required food’ (Miracles of Saint Nicholas)

In the present paper, we do not dwell on the indefinite markers that emerged later – in the Middle Russian period, that is, on nibud’, -to and -koe. The particles ljubo and libo are treated as one marker (we have only one example with libo instead of ljubo in our dataset).

In OES, there were also other pronouns that could be used in ways very similar to the indefinite ones. These include universal quantifiers such as kъžьdo ‘each’ and vьsjakъ ‘every’, and identity/non-identity determiners such as inъ and drugyj ‘another’. For various reasons, neither of the two classes are considered to be true indefinite pronouns (cf. Haspelmath, 1997, 11‒13). In this paper, we do not dwell on such quantifiers and focus only on true indefinites; an exception is made only for the pronoun eter-, a borrowing in OES, which can have pure indefinite uses (see below).

We proceed as follows: Sect. 2 presents an overview of previous research on the history of indefinites in East Slavic. Section 3 introduces the research data and the methods used in the study. Sections 4 and 5 discuss the results.

2 State of research

Indefinite pronouns have always been among the most discussed topics in Modern Russian linguistics (see, for example, Růžička, 1973; Šeljakin, 1978; Padučeva, 1985; Seliverstova, 1988; Kuz’ mina, 1989; Tatevosov, 2002; Bylinina & Testelec, 2005; Geist, 2008; Kustova, 2015). This is not the case for OES indefinites, which are, on the contrary, under-researched (see Malovickij, 1971; Krys’ ko et al., 2020; for Middle Russian, see Penkova 2011, 2016, 2017, 2021). Differences and changes in the distribution of OES indefinites, their referential status, refunctionalization, and competition between different types in different genres and registers – these are all questions that have remained outside the scope of previous research.

For Old Church Slavonic, Večerka (1989) enumerates several indefinite pronouns and provides a few examples of their being used with a substantival function. He counts interrogatives such as kъto ‘who’, čьto ‘what’, as well as někъto, něčьto, among the indefinite pronouns (Večerka, 1989, p. 39; 1996, p. 135; 2002, p. 179). However, Večerka only discusses the syntactic functions of these pronouns – i.e., whether they can be used attributively or substantivally – and pays no attention to their semantics and reference.

The OCS dictionary (SJS) also treats the particle ljubo as a marker of indefiniteness, providing examples from Codex Suprasliensis and some later Russian manuscripts from the 1200s and 1500s (SJS II, p. 159), cf. (8).

-

(8)

Имѣниѥ свое желаѧ оустроити по коѥмоу лоубо образоу

‘Wishing to arrange his belongings according to a certain manner’ (Supr. 547, 3sq, Večerka, 1989)

The origins of ljubo as well as the shift from ljubo to libo that took place in Russian are not clear. Recently, Majer (2015) proposed an interesting hypothesis regarding the development of ljubo. He cites numerous authoritative sources (e.g., Vaillant, 1958, p. 407; ĖSSJa 15, p. 177) claiming the grammaticalization path of the indefinite marker ljubo (as well as the conjunction ljubo ‘or’) originated from the neuter of the adjective *ljubъ. However, after analyzing both Slavic and Non-Slavic data, he concludes that “it is a tempting alternative to derive them from a (Post-)PIE verbal form *lewbh-o(r) instead” (Majer, 2015, p. 201), more specifically, from the t-less middle voice form, which is known to produce indefinite formants across Indo-European. According to Majer, if the t-less middle voice form is the source of grammaticalization this directly implies that “the grammaticalization must have happened before the class of t-less middles was lost from the language” (Majer, 2015, p. 200). Whereas this conclusion sounds reasonable for the conjunction ljubo, which lost its semantic connection with the verbal meaning, it creates a problem for ljubo as an indefinite marker, which shows a lower degree of grammaticalization in OES (see below).

The reasons for the shift from ljubo to libo have not yet been established and call for separate research. There are contradictory explanations in the scholarly literature. Some scholars claim that the shift from ljubo into libo might have occurred for phonological reasons such as delabialization, as is typical for subsequent stages of grammaticalization (Miklosich, 1886; Haspelmath, 1997, p. 168). Others (cf. Fasmer II, p. 493) reject this explanation. This shift could possibly also be explained in terms of contamination between two paronyms, namely, the phonetically and functionally similar conjunctions ljubo and libo, which both exhibit a disjunctive meaning (‘or’).

Pičсhadze (2011) has discussed the pronoun eter- as a feature of the Cyrillo-Methodian language. She shows that eter- was often replaced with ně(kyj) in later Church Slavonic texts copied in Preslav. Nevertheless, the pronoun eter- was preserved in many Old Bulgarian texts and was adopted by the Old East Slavic tradition. Many attestations of eter- can be found in East Slavic copies of Old Bulgarian translations (for more information, see Pičсhadze, 2011) as well as in original East Slavic texts from as late as the 17th century (SRJa V, p. 64).

The pronoun eter- could be used in two main ways: as an indefinite pronoun (with both substantival and attributive functions) and to indicate non-identity (‘another’). According to Pičсhadze (2011), the latter was a Serbian-Macedonian innovation unknown in the Cyrillo-Methodian tradition. However, both uses were well-known in East Slavic. We will deal here only with eter- as a marker of indefiniteness, though both meanings are to some extent semantically and (probably) diachronically related.

According to Miklosich’s lexicon (Miklosich, 1862–1865, p. 1150) and the Etymological Dictionary of the Slavic Languages (= ĖSSJa; 1981, V, p. 185‒186), there was another infrequent construction which could mark indefiniteness, consisting of the demonstrative pronoun je combined with the de-particle and an interrogative pronoun.Footnote 2 In the following we will not deal with this construction with the particle jede since it is extremely marginal in OES.

Some topics related to the history of indefinite pronouns in Russian are discussed by Malovickij (1971, p. 3‒130). The most significant contribution of his paper was to describe interrogative pronouns with indefinite function and to identify their typical uses, specifically in conditional clauses, interrogative sentences and irrealis predication, and in combination with the pronouns inъ, drugyj ‘(an)other’ (i.e., in the context of disjunction). Malovickij examines other structural types of indefinites mainly based on data from late Middle Russian or even later periods (19th–20th century Russian texts). Consequently, neither the emergence nor the semantic evolution of OES indefinites has been traced thoroughly. Pronouns that ceased to be used over the course of the history of Russian, such as eter-, were left out of his study.

Malovickij’s description, accomplished in the “pre-corpus” era, obviously requires verification, significant revision and amendment to account for up-to-date knowledge in the field and the possibilities of corpus-based research methods.

From a typological perspective, indefinite markers are often described by means of semantic maps (Haspelmath, 1997 and Tatevosov, 2002). According to Haspelmath (2003, p. 213), a semantic map is “a geometrical representation of functions in “conceptual/semantic space” that are linked by connecting lines and thus constitute a network.” It implies that the configuration of a map is universal and that a gram “occupies a contiguous area” in it (Haspelmath, 2003, 216). Semantic maps for the indefinite pronouns in Modern Russian are established by Haspelmath (1997) and Tatevosov (2002, p. 141). For OES indefinites, neither synchronic semantic nor diachronic semantic mapsFootnote 3 have been established.

Haspelmath (1997) also identified the main diachronic sources of the grammaticalization of indefinite pronouns. According to his analysis, there are at least four main constructions that serve as sources of grammaticalization for indefinites (1997, p. 130‒141):

-

Don’t know-type: Bog vestʹ kto ‘God knows who’ (Haspelmath, 1997, p. 131); Middle Russian nivěs(t)ʹ kakoj ‘[one] doesn’t know which’; type absent in OES;

-

wants/pleases-type: kto ugodno ‘whoever pleases [you]’ (Haspelmath, 1997, p. 134); OES kъto ljubo ‘whoever pleases [you]’;

-

no matter-type: french n’importe qui ‘no matter who’ (Haspelmath, 1997, p 140); kto ni pópadja ‘whoever one comes upon’; type absent in OES;

-

it may be-type: kto by ni bylo ‘whoever it would be’, kto-nibudʹ ‘whoever let [it] be’ (Haspelmath, 1997, p. 135); Middle Russian kto ni jestʹ ‘whoever [it] is’; type absent in OES.

According to Haspelmath, other sources of indefinites not driven by grammaticalization are:

-

interrogative pronouns in the function of indefinites (an archaic feature of many Indo-European languages including Vedic Sanskit, Ancient Greek, Latin, Gothic, Slavic and OES in particular, yet with restricted usage in modern colloquial Russian). Haspelmath argues that the ability of interrogatives to be used as indefinites is based on the shared semantic component of ‘ignorance’, a characteristic of both interrogative and indefinite pronouns (Haspelmath, 1997, p. 175); different functions of interrogatives in the function of indefinites across Slavic were discussed by Křížková (1974);

-

reduplication of interrogatives: Latin quis-quis, lit. ‘who-who’ (Haspelmath, 1997, p. 179), Late Middle and modern Russian кое-кто, lit. ‘which-who’; this type is based on the notion of irrelevance; the type is unknown in OES;

-

negative scalar focus particles: modern Russian negative indefinite pronouns like nikto ‘not even who’ (Haspelmath, 1997, p. 222), etymologically also nеktо, nečto; OES někto, něčto, etc.

There are also several other diachronic sources of indefinite pronouns, such as generic nouns (e.g. French rien, personne) or numerals denoting ‘one’ (Haspelmath, 1997, p. 157–335). However both types have only restricted uses.

Indefinites in modern Russian were also discussed by Haspelmath (1997). However, some of his observations were based on incorrect etymological interpretations. For instance, Fasmer argues that it is incorrect to explain the etymology of the prefix ně- through *nе vě ‘don’t know’ (Fasmer III, p. 59), as Haspelmath does (Haspelmath, 1997, p. 131). There are other, more acceptable etymologies for ně-, such as a lengthened form of the negative particle *ne or a PIE deictic particle *ne/no (Fasmer, 2004, III, p. 59, see also ĖSSJa 1997, p. 24, pp. 91‒93). A good structural analogy to the former explanation can be found in the Northern Russian dialects, where there are indefinites consisting of an interrogative and a negative particle, just like the ně-pronouns. However, in this case, the negative particle ni follows the interrogative pronoun, cf. gde-ni ‘anywhere, lit. where even not’ (Zaliznjak, 2004, p. 200; on the prosodic status of Middle Russian ni, see also Penkova, 2011).

Therefore, in OES, we are dealing primarily with the following types: bare interrogatives as indefinites (kъto, čьto, etc.), indefinites of the wants/pleases-type (kъto ljubo, etc., later replaced by kъto-libo; see the overview above); and the negative particle-type (někъto, etc.).

Cross-linguistically, indefinite pronouns are typically characterised by multifunctionality and diachronic instability. Multifunctionality, i.e., the ability of different structures to be used in the same types of contexts, inevitably leads to competition between them (for the competition of indefinites in Modern Russian see, for instance, Padučeva, 1985, p. 219–220). Diachronic instability of indefinites implies that they are subject to rapid changes in semantics. According to Haspelmath, as they evolve semantically, their capacity for emphasis is gradually weakened: “[…] the semantic grammaticalization of indefinite pronouns is primarily weakening of emphasis”Footnote 4 (Haspelmath, 1997, p. 154).

In the present paper, we describe the OES system of indefinite markers and establish the role of each marker in it. We can expect the OES system of indefinites to be organized differently from Modern Russian one, with one marker simultaneously covering many functions. We also expect to find diachronic changes occurring over a fairly short period considering the diachronic instability of indefinites. Finally, we assume that there could have been differences or changes in the distribution of indefinite markers with regard to the rhetorical strategy of the writer, i.e., between higher-code and lower-code texts and contexts, as well as between different types of discourse.

3 Data and methods

We collected our data from the historical subcorpora of the Russian National Corpus (RNC), specifically the Corpus of Birchbark Letters and the Old Russian Corpus. The former is rather small and contained only 19002 tokens at the time it was accessed. At the time of writing (October 2021) it comprised 1059 birchbark letters, which accounts for about 90% of all the birchbark letters that have been discovered so far. The Old Russian Corpus is more extensive and included 504077 tokens at the time it was accessed. Though these corpora may seem not large enough for studying infrequent phenomena, that is not the case for indefinite markers, which exhibit frequencies comparable with that of major grammatical categories.

Both corpora are fully tagged for part-of-speech and morphology and manually corrected. However, they are not completely disambiguated for our purposes, which means that we could not get disambiguated search results for most of our items.Footnote 5 First, the corpus tagset does not recognize interrogatives used in the function of indefinites. Second, we cannot rely on the corpus tagset to distinguish between uses of ljubo as an indefinite particle and as an epistemic particle meaning ‘maybe’ (SRJa VIII, 328). The latter is used without a pronoun, so it is not the subject of our analysis (9).

-

(9)

сн҃ѹ мои Юрьи не ходи самъ с Литвою ѹбилъ

кнѧзѧ ихъ Воишелка любо восхотѧть мьсть створити

кнѧзѧ ихъ Воишелка любо восхотѧть мьсть створити‘my son Jurij, do not go with the Lithuanians yourself. I killed their prince Voišelk, maybe they want to take revenge’ (Volhynian Chronicle)

Finally, we could not automatically draw the line between the use of eter- as an indefinite pronoun and with the meaning of ‘another’. Therefore, all the search entries of the zero-marked pronouns, pronouns combined with the particle ljubo and the pronouns eter- were manually checked for indefinite meaning. For instance, we included in our dataset examples such as (17), in which the pronoun kto is used in the indefinite function, but not examples such as (10), where it is used as an interrogative, and not examples such as (11) with a relative function of the pronoun kto. We also did not include in the dataset examples with ljubo such as (9) and examples with eter- such as (12), in which it is used in the meaning ‘(an)other’.

-

(10)

никола […] рече къто ты ѥси и ѿкѹдѹ идеши и къ комѹ идеши?

‘Nicolas […] said: “Who are you and where do you come from and to whom are you going?”’ (Miracles of Saint Nicolas)

-

(11)

кто боудеть виноватъ на того татьба снидеть

‘The responsibility will fall on the person who is guilty’ (Russkaja Pravda)

-

(12)

Соломо(н҃): Желѣзо желѣза остритъ, мѹжь же остритъ лице етера

‘Iron sharpens iron and a man shapes the countenance of another one’ (Pčela)

Nevertheless, the Old Russian Corpus, complemented by the Corpus of Birchbark Letters, is a reliable source, especially since it is possible to discriminate among the textual genres in it. It includes a representative number of OES original texts as well as texts translated by East Slavic scribes. The translated texts in the corpus comprise 7 sources (237998 words), i.e., “Life of Andrew the Fool”, “1076 Izbornik of Svjatoslav”, “Alexander Romance”, “History of the Jewish War”, “Story of Ahikar”, “Miracles of Saint Nicolas”, and “Pčela”. The original sources in the corpus comprised nine texts at the time of access (266079 words), i.e., six chronicles (The Primary chronicle, Novgorod First chronicle, Kievan, Galician, Volhynian and Suzdal’ chronicles), “Questions of Kirik”, and two tales by Cyril from Turov. Only legal texts were lacking at the time the Old Russian Corpus was accessed, though some such texts are incorporated into the chronicles in the corpus. The Corpus of Birchbark Letters supplies us with instances of vernacular usage of indefinite markers.

The resulting dataset contains 608 examples: all examples of the indefinite markers ljubo and eter-, all examples of někъto and něčьto, and of kъto and čьto used as indefinites, from all OES sources included in the Old Russian corpus and the Corpus of Birchbark Letters at the moment of access. We did not include numerals such as OES odinъ (OCS edinъ) in our dataset since they are limited to the attributive function, and we were focused primarily on indefinites with a substantival function.

After collecting the data, we tagged the indefinite markers in our dataset for various features.

First, we tagged them for the type of indefinite marker. We distinguish between zero-marked indefinites deriving from interrogatives (limited to contexts with the pronouns kъto and čьto only); as well as kъto and čьto prefixed by indefinite marker ně- (the reason for this choice is the impossibility of getting disambiguated results for bare interrogatives and the need for manual data selection), all pronouns marked with ljubo, and all indefinite uses of the pronoun eter-.

Second, we tagged the indefinites for source, including originality and date. In the case of translations, this was the date when the translation was produced, rather than the date of the copy. Accordingly, the examples from the “Life of Andrew the Fool” are tagged for the 12th century and not for the 14th, the date of the earliest known copy (Moldovan, 2000). The same holds for other translated sources, such as the “Story of Ahikar” (the translation is no later than 1230, yet the earliest copy dates from the 15th century), the “History of the Jewish War” (the translation was made in the 12th century, cf. Pičchadze, 2002, p. 168, while the earliest copies are from no earlier than the 15th century), etc. The same strategy was adopted for the original OES texts (works by particular authors and chronicles as far as we are aware of their textual history). Based on these principles, the examples from the Kievan Chronicle were tagged for 1199, the time when Abbot Moses of Vydubyči Monastery brought together a set of linguistically diverse sources into one codex, and not the 15th century, the date of the earliest extant copy. Examples from original works by a particular author (e.g., Cyril of Turov or Kyrik of Novgorod) are tagged in our dataset according to the lifetime of the respective author. Examples from the birchbark letters are tagged with the date established in (Zaliznjak, 2004). If the date reads “no later than year N”, the example is tagged with the last possible year. The data is distributed evenly across two important periods in the evolution of OES: we collected 289 examples from Early Old East Slavic, that is from the 11th and 12th century sources, and 320 examples from Late Old East Slavic (13th ‒ 14th century sources). Within the former subset, the majority of data belongs to the 12th century (244 examples), whereas for the 11th century, we collected only 45 examples. The datasets for the 13th and 14th centuries, on the other hand, are comparable, containing 152 and 168 examples respectively.

Third, the indefinites were classified according to their reference type:

-

a)

specific indefiniteness (the object is specific but unknown to the speaker);

-

b)

half-definiteness (the object is specific, known to the speaker and unknown to the listener);

-

c)

non-specific indefiniteness, or existential indefiniteness (the object exists but is not specified);

-

d)

universal reference (indefinite markers serve as universal quantifiers).

We distinguish between four main types of reference: half-definite, specific indefinite, non-specific indefinite and universal, or generic.Footnote 6 Specific indefiniteness implies that the object is specific but unknown to the speaker. According to Haspelmath (1997, p. 38), “the speaker presupposes the existence and unique identifiability of its referent”, cf. (13).

-

(13)

и бѣаше в судѣ томъ нѣчто чрѣмно добрѣ вонѧ

велми, да

велми, да  коже съ ст҃ою водою смѣсивъ и съклативъ, вда пити, рекъ ѥму: миръ тебе

коже съ ст҃ою водою смѣсивъ и съклативъ, вда пити, рекъ ѥму: миръ тебе‘and there was something red in that vessel that smelled very nice, and when [he] mixed it with holy water [he] gave him a drink, saying to him: Peace [be] with you’ (Life of Andrew the Fool)

The main diagnostic factors which allow us to identify specific reference are the use of a co-referential anaphoric pronoun (cf. onъ ‘he, that’ in 14) and an affirmative declarative sentence with the perfective past or an ongoing presentFootnote 7 (13).

-

(14)

слыша же хлапъ […]

ко речи нѣкому,

ко речи нѣкому,  ко изъ млада ѥсть ѹмѣлъ сьи

ко изъ млада ѥсть ѹмѣлъ сьи  зыкъ, да хлапъ молѧшесѧ, да бы ѥму быти,

зыкъ, да хлапъ молѧшесѧ, да бы ѥму быти,  коже ѥсть и ѻнъ

коже ѥсть и ѻнъ‘A slave heard someone saying that [he] knew this language since his childhood and the slave begged to be like that’ (Life of Andrew the Fool)

Half-definiteness means that the object is concrete, known to the speaker and unknown to the addressee; cf. 15 and 16. We consider the use of a pronoun to be half-definite if it is used with a proper noun in the context (cf. 15), or the pronoun depends on a modal verb in the 1st person form requiring definite reference (cf. chošču ‘I want’ in 16).

-

(15)

бѣ же нѣ́кто та́мо паѹса́ниѧ именемъ, мѹ́жь вели́къ и бога́тъ зѣло

‘There was a certain man there whose name was Pausania, a great man of wealth ’ (Alexander Romance)

-

(16)

хощю ємѹ показати нѣчто ди́вно

‘I want to show him something amazing’(Alexander Romance)

Non-specific indefiniteness means that the object is not specified. The main criteria for such use, according to Haspelmath (1997, p. 45), is the presence of the indefinite in conditional protasis, questions (cf. 17), contexts with the imperative, direct and indirect negation. The same criteria were used for tagging indefinite markers in our dataset.

-

(17)

ре(ч)

нь к по(д)возникомъ: ци кому васъ родинъ ѹбьенъ ѿ сею?

нь к по(д)возникомъ: ци кому васъ родинъ ѹбьенъ ѿ сею?‘And John said to the drivers: Is there any of your relatives among those killed?’ (Primary Chronicle)

Generic reference is used for speaking about a category of objects. The main type of contexts where the pronoun may be used with the generic reference is an imperfective present tense or future lacking their temporal meaning but denoting possibility (cf. 18).

-

(18)

можеть кто любо ѿ дѣмонъ плакатисѧ

‘anyone/everyone can cry because of demons’ (Life of Andrew the Fool)

Fourth, we also defined the semantic function of indefinite markers in our dataset according to the classification elaborated by Haspelmath (1997) and Tatevosov (2002) for semantic maps of indefinite pronouns (see below for details). This classification does not always match the reference type (as in the case of universal references).

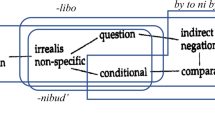

Haspelmath’s semantic map for indefinite pronouns (for the notion of a semantic map, see above) includes and arranges different types of functions, among them the following: specific known, specific unknown, irrealis-non specific, question, conditional, indirect negation, direct negation, comparative, free-choice. Haspelmath’s map has been revised and completed by Tatevosov who added three nodes for the functions covered by universal quantifiers, i.e., generic, completeness, and definite (Tatevosov, 2002, p. 167). We will also use the node for generic and neglect the other ones as irrelevant for indefinite pronouns (Fig. 1).

The functions that are labelled as specific known and specific unknown are already discussed above. Most functions on the map belong to the non-specific, or existential, reference type. Now, we will illustrate these functions with OES examples. The only function that we cannot illustrate with an example is the comparative function, that is the use of an indefinite marker in the standard of comparison (bigger than anyone type). According to Haspelmath, the domain of negative polarity is covered by the following functions: direct negation (the central context is a direct, or clausemate, negation) (19), polar questions (20), conditional protasis (21), and indirect negation, which includes contexts of implicit negation (complements of verbs meaning ‘refuse’, ‘be absent’, etc.; prepositions meaning ‘without’, ‘besides’, etc.; negative quantifiers like ‘few’, and contexts with negation in the main clause and an indefinite NP in the subordinate clause, see Haspelmath, 1997, pp. 33‒37; Tatevosov, 2002, 137), cf. (22).

-

(19)

и нѣ бѣ емѹ кого послати

‘and he had no one to send’ (Galician chronicle)

-

(20)

мышлѧх же и се гл҃ѧ: есть ли здѣ кто инъ или азъ єсмь єдинъ?

‘I was thinking so, saying: is there anyone else here or am I alone?’ (Life of Andrew the Fool)

-

(21)

али чимо есемо винова|та а восоли отроко

‘If I am to blame for anything, send a bailiff’ (Birchbark letter 644, 1100-1120)

-

(22)

ѿлѹчено бо єсть в̾кѹсити что преж(д)е мл҃твы

‘it is forbidden to eat anything before praying’ (History of the Jewish War)

The irrealis-non-specific function comprises various types of irrealis contexts including hypothetic and counterfactual modality, future, imperative, complements of non-factual predicates (like ‘want’), and habitual, e.g. (23).

-

(23)

Всѧкомѹ хотѧщем

к тобѣ что изрещи подажь дерзновениѥ

к тобѣ что изрещи подажь дерзновениѥ‘Give courage to anyone who wants to tell you something’ (Pčela)

Free-choice indefinites are used when “the speaker introduces many objects into consideration […] one of which the listener has to choose” (Tatevosov, 2002, p. 145), cf. (24).

-

(24)

сверзи коверъ ли что ли что постьлати или чимъ прекрыти г(с̑)на нашего

‘Throw the rug or whatever you can lay or cover our master with’ (Kievan chronicle)

The free-choice uses can be very similar to the uses of indefinites as universal quantifiers, that is, with generic, or universal, reference (cf. 18 above). For us, the main criterion to distinguish between the former and the latter was the reading ‘every, all’, possible for an indefinite used with the generic reference (cf. 18 above) and impossible for a free-choice functionFootnote 8 (cf. 24).

As mentioned above, the notion of a semantic map implies that there is not only a list but also a certain order of uses with particular links between them, and that the functional spaces covered by the markers are contiguous (see Haspelmath, 2003). In contrast to synchronic ones, diachronic semantic maps also specify the direction of development from one type of use to another. Moreover, while synchronic semantic maps have been already established for Russian indefinite pronouns, diachronic ones have not. A diachronic analysis could contribute to creating such a diachronic map.

Fifth, we took into consideration the type of discourse (deictic discourse, narration, or irrealis discourse) and the degree of formality (formal or informal) represented in the context. Relying on the classification of types of discourse proposed by Plungian (2008, p. 24), we were able to discern three types of discourse: deictically oriented discourse, the interpretation of which requires an appeal to the moment of speech; irrealis discourse, not requiring such an appeal (habitual, hypothetical, counterfactual situations, combined with a non-referential character); and narrative discourse. Irrealis discourse should not be confused here with the irrealis semantic domain.

The degree of formality and type of discourse are attributed to the context and not the source text in general due to the fact that the latter is – usually – quite straightforward. Usually, the immediate context is equal to one or two sentences and becomes evident in the context of the corpus output. In the case of direct speech, the boundaries of the context coincide with the boundaries of the direct speech, on the one hand, and the text of the author that introduces direct speech, on the other hand. This is particularly important for chronicles, which are a heterogeneous genre of medieval writing and may include more formal hagiographical discourse as well as the more informal speech of treaties (on the existence of at least two linguistic layers in the Kievan Chronicle, see Zaliznjak, 2004, p. 51).

We classified the context as formal if it included one or more linguistic features of high-code writing, such as an aorist, imperfect, dative absolute, accusative with infinitive, or any other syntactic/morphological marker with a higher degree of formality (for an extensive list of formal and informal features see Uspenskij, 2002, pp. 192‒266; for the discussion of different linguistic features typical for formal and informal registers see Živov, 2017, pp. 325‒815), e.g. (25–26).

-

(25)

ты, цр҃ю, самъ вѣси, въ дн҃ї твоѧ и во дн҃и ѡц҃а твоєго коє любо слово прεм

дрыи акыръ исправлѧше

дрыи акыръ исправлѧше‘you, king, know yourself that in your days and in the days of your father, the wise Ahikar would fulfill any promise’ (Story of Ahikar)

-

(26)

Нѣкомѹ много исторьѣ предъ ними молвѧщю […]

‘while someone was telling a lot of stories in front of them […]’ (Pčela)

We tagged the context as “formal” if it included high-code lexical or derivational features and no lower-code ones (as in 27), and as “informal” if it included low-code features (28).

-

(27)

ѥже вы ѥсть въ имѣнии ли злато, ли срѣбро, ли ино чьто, ѥмѹже что хощете оставити

‘which you have in the property: gold, or silver, or something else, to whom you want to leave something’ (Miracles of Saint Nicholas)

-

(28)

ты ѥси ѹ насъ кнѧзь ѡдинъ, ѡже тобѣ сѧ что створить, то что на(м̑) дѣ

ти? A поѣди, кнѧже, к городу

ти? A поѣди, кнѧже, к городу‘you are our only prince; if something happens to you, then what shall we do? And go, prince, to the city’ (Suzdalʹ Chronicle)

Contexts lacking either high- or low-code features were classified as informal (the reason for this decision will be given below), as in (29).

-

(29)

да дроугыи сблюдеть колико любо, а дроугыи мало, дажь и падають. Лзѣ ли имъ в божници быти?

‘And one observes some [rules], and another only few [of them], and [some people] even fall, is it licit for them to be in church?’ (Questions of Kirik)

-

(30)

Сокра(т҃): Нѣкто ѥго въпраша(л҃): что ѥсть въздержаниѥ?

‘Socrates: Someone asked him what abstinence is’ (Pčela)

Such an approach to classifying contexts makes it possible to identify cases in which the choice of the indefinite marker might have been forced by the presence of high-code stylistic markers. It also explains why contexts without any stylistic markers are classified as informal. In such cases, as well as in contexts with low-code markers, the choice of the speaker/writer is not influenced by any formal features, so it is more likely that an item from the vernacular system would be intuitively chosen.

We applied a mixed-methods approach, i.e. a combination of qualitative and quantitative analysis. We used statistical methods such as Random Forest analysis as well as multinomial logistic regression.

4 Analysis of data and discussion

In this section, we discuss the factors that were taken into consideration in our dataset: reference, semantics, degree of formality, discourse types, originality of sources, date, and source specification. Studies of this kind that take into account all the above-mentioned factors (both reference types and semantic distribution of OES indefinites, and different discourse factors) as well as a wide range of sources provided by the RNC haven’t been undertaken yet.

We will structure the discussion that follows according to these probable predictors and show which of them play a more significant role, and which do not.

4.1 Reference type

Table 1 shows the frequency of different reference types.

It is obvious that non-specific indefiniteness (the existential reference type) is the most frequent and that the most frequent marker with this type is the zero marker. On the other hand, the half-definite and specific indefinite reference types are most often tied to the use of the prefix ně.

According to the data, interrogatives were used as the main means of expressing non-specific indefiniteness, e.g. (31) and (32).

-

(31)

сн҃

, ащε что слышиши, не повѣдаи ником

, ащε что слышиши, не повѣдаи ником , аще что ѹзрыши, не обавлѧи

, аще что ѹзрыши, не обавлѧи‘son, if [you] hear anything, do not tell anyone; if [you] see anything, do not show [it to anyone]’ (Story of Ahikar)

-

(32)

ѹбивашеть бо на всѧкъ дн҃ь по три по четыри. которого же дн҃i не ѹбь

шеть кого, печаловашеть тогда, коли же ѹбь

шеть кого, печаловашеть тогда, коли же ѹбь шеть кого, тогда веселъ бѧшеть

шеть кого, тогда веселъ бѧшеть‘because he killed three to four people every day; if on a given day he didn’t kill anyone, then he was sad. Whenever he was killing someone, [then] he was cheerful’ (Volhynian Chronicle)

However, it is possible that at an earlier stage zero-marked indefinites may have been used with a specific type of reference, as in the following OCS example given by Křížková (1974, p. 82):Footnote 9

-

(33)

Прикоснѫ сѧ мьнѣ къто, азъ бо чюхъ силѫ ишьдъшѫ из мене

‘someone touched me, for I felt a force emanating from me’ (Lk. 8:46, Zogr.)

Pronouns with the prefix ně display a wider range of forms of “indefiniteness”. Unlike zero-marked indefinites, ně-pronouns tend to occur more frequently with a specific reference (34). However, they are also attested in non-specific uses (35).

-

(34)

и р(ч̑)е: ѡле тѣ нѣкто мѧ ѹдари за плече. и не може с того мѣста ни мало поступити и хотѣ летѣти

‘and [he] said: oh, but someone hit me on the shoulder! Аnd [he] couldn’t step from that place and was about to fall’ (Kievan Chronicle)

-

(35)

видивъ, ѥпифанъ ѻбрати лице своѥ ѿ не

, ѹлыснувсѧ и ре(ч̑): “зрите на бестудную сию лисицю, како ти сѧ ломить, лукаво хотѧщи ѹловити курѧ, рк҃уще, нѣ ѿ кого ѹнаго дш҃ю ѹловити!”

, ѹлыснувсѧ и ре(ч̑): “зрите на бестудную сию лисицю, како ти сѧ ломить, лукаво хотѧщи ѹловити курѧ, рк҃уще, нѣ ѿ кого ѹнаго дш҃ю ѹловити!”‘seeing [this], Epiphanius turned his face away from her, smiled and said: “look at this shameless fox: how it is wriggling, craftily desiring to catch a chicken, that is, to ensnare the soul of some young one!”’ (Life of Andrew the Fool)

The marker ně could indicate a specific object irrespective of whether the object was familiar to the speaker and unknown to the addressee (half-definiteness, as in 36), or was unknown to both the speaker and the listener (37) (cf. the difference between the modern Russian koje- and -to). The system of indefinite markers thus did not have a particular marker of half-definiteness akin to modern Russian koje-.

-

(36)

конникъ же помолисѧ имъ гл҃ѧ: повѣмъ вамъ нѣчто же полезноє, имже ѡдолѣєте ѡтинѹдь, аще мене не ѹбиєте

‘the horseman was begging them, saying: I will tell you something useful, with which you will completely prevail if you do not kill me’ (History of the Jewish War)

-

(37)

сократъ же, видѣвъ и зимою ѹмирающа, и ѡдѣ и, и ѡбѹ, и пищѹ давъ емѹ, и ѿстѹпи; и поносимъ же бы(с҃) ѿ нѣко(г҃), зане незнаемаего разбоиника снабдѣ, и ѿвѣща: не аки чл҃вка разбоиника поч(с҃)тихъ, но чл҃вчьское ѥ(с҃)ство почьстихъ

‘Socrates, seeing him dying in the winter, both clothed and shod him, and gave him food, and departed; and he was reproached by someone because he had equipped an unknown robber, and Socrates answered: I honored him not as a robber, but as a human being [lit.: as a human nature I honored him]’ (Pčela)

Surprisingly, even the ně-marked indefinites sporadically occur with universal (generic) reference. In our material there is only a sole relic attestation of this (38), in combination with edinъ.

-

(38)

мѹжи воистїи, аще и мало єсть число наше, но смыслъ в на(с҃) великъ, и дръзновениє, и сила паче пръсъ противныхъ нашихъ. никто(ж҃) ѹбо ѿ васъ немощно нѣчто да не смыслить, видѧ множество варваръ. єдинъ бо нѣкто ѿ васъ, рукѹ ѡбнаживъ, тысѧщю побїєть противныхъ

‘warriors, even if our numbers are small, our craft is great, as is our courage, and [our] strength is greater than that of the Persians, our enemies. Let none of you imagine anything weak upon seeing many barbarians, because any/every one of you, baring his hand, will defeat a thousand enemies’ (Alexander Romance)

The ljubo-marker is considerably less frequent than zero-marked indefinites and the ně-series. Consider the frequency with which markers related to kъto and čьto occur (Table 2).

Such a low frequency can hardly be considered accidental. It can be taken as an indication that ljubo was a new marker, probably one still undergoing a process of grammaticalization (cf. the similar conclusion by Malovickij, 1971, p. 71). There are many examples of quasi-relative constructions with ljubo preserving the expected argument structure, i.e. dative of the experiencer (40–41), and of relative constructions with ljubo preserving agreement in gender (39).

-

(39)

ѡже бы пришелъ толико съ дѣтьми, то котора

єму волость люба, ту же бы взѧлъ

єму волость люба, ту же бы взѧлъ‘if [he] had come only with children, then whichever province he loved, [he] would have taken’ (Kievan Chronicle)

-

(40)

а къ онтонию послаша: поиди кде ти любо; антонии же поиде въ новгородъ

‘and they sent to Anthony: go wherever you like; and Anthony went to Novgorod’ (Novgorod Primary Chronicle. Synodal Redaction)

-

(41)

пѹщени быша камо и(м) любо

‘they were released wherever they liked’ (History of the Jewish War)

Ljubo occurs only to express non-specific indefiniteness, and as a universal marker, i.e. in contexts typical for zero-marked indefinites. It thus could have entered the web of indefinites as a marked functional alternative to the older unmarked interrogatives, or it could have first specialized as a marker of the free-choice function. Consider, for example, the difference between (42) and (43):

-

(42)

аще ѹкраде(т) русинъ что любо ѹ крѣсть

нина или пакы хр(и)сть

нина или пакы хр(и)сть нинъ […]

нинъ […]‘if one of the Rusʹ steals something from a Christian or vice versa […]’ (Primary Chronicle)

-

(43)

аще ли ѿ не

възметь кто что, или чл҃вка поработить, или ѹбьеть, да будеть виненъ закону рускому и грѣцком(у)

възметь кто что, или чл҃вка поработить, или ѹбьеть, да будеть виненъ закону рускому и грѣцком(у)‘if someone takes something from it or enslaves a person, or kills a person, let him be accused of violating Russian and Greek law’ (Primary Chronicle)

Another piece of evidence supporting this observation is an example with double marking: an interrogative koe marked with both ně and ljubo, with ně already being less strongly associated with non-specific uses and thus requiring a stronger marker of non-specific indefiniteness (44).

-

(44)

аще ѡбрѧщю(т) русь кувару грѣчьску вывержену на нѣкоемъ любо мѣстѣ, да не приѡбидѧть е

‘if the Rusʹ find a Greek ship cast away in some place, [they shall] cause no damage to it’ (Primary Chronicle)

The homonymy of the interrogative and indefinite pronouns could have reinforced the development of a special marker of non-specific indefiniteness or its drift from free-choice towards other non-specific functions. The source of this marker was the quasi-relative construction interrogative + predicative ljubo, with the experiencer in the dative omitted.

The indefinite eter- occurred in the sources only sporadically and did not belong to the core system of indefinites. Its peripheral status can be proven by its indifference to any type of reference, which suggests that it was a multifunctional higher-code substitution for any indefinite marker (primarily for the multifunctional ně). In (45), eterъ is a marker of non-specific indefiniteness (it is accounted for by the context of conditional protasis, impossible for a marker of specific reference). In (46), it is a marker of specific indefiniteness (it is accounted for by the narrative context); whereas in (47), it is a marker of half-definiteness (cf. the context with a proper noun). Finally, in (48), it is a universal quantifier (cf. the gnomic use of future tense in the meaning of possibility):

-

(45)

аще братъ етеръ вънъ идѧше изь манастырѧ, и всѧ брать

имѧху ѡ томъ печаль велику

имѧху ѡ томъ печаль велику‘if any brother left the monastery, then all the brothers were very sorrowful for him’ (Primary Chronicle)

-

(46)

придоша же ѥтери ѿ града и поклонишасѧ рѣша ст҃омѹ

‘some [people] came from the city and bowed and said to the saint’ (Miracles of Saint Nicholas)

-

(47)

цр҃ь же рече имъ: Вѣсте ли ѥтера николѹ тако нарицаѥма? Они же, слышавъше имѧ ст҃го николы,

ко ѥдинѣми ѹсты тако възъпиша

ко ѥдинѣми ѹсты тако възъпиша‘And the king said to them: Do you know a certain so-called Nicholas? They, hearing the name of St. Nicholas, exclaimed in chorus’ (Miracles of Saint Nicholas)

-

(48)

ѹтѣшаите печалны

по истинѣ аще что створилъ есть на свѣтѣ семь, етеро согрѣшенье ѿдастьсѧ ему, зане положи главѹ свою за бра(т) своего

по истинѣ аще что створилъ есть на свѣтѣ семь, етеро согрѣшенье ѿдастьсѧ ему, зане положи главѹ свою за бра(т) своего‘console those who grieve truly if they have done anything [sinful] in this life; any/every sin will be forgiven for someone who has laid down his life [lit.: head] for his brother’ (Primary Chronicle)

4.2 Semantic functions of OES indefinites

We tagged our data according to the functions proposed by Haspelmath (1997). Unfortunately, not all the semantic types of use are present in the corpus: we have no examples at all of the comparative function and very few examples of questions and indirect negation (Table 3).

According to our data, zero-marked indefinites occur most frequently in conditional and irrealis non-specific uses (including future events as well as different types of non-indicative modality: in this respect, it confirms the results obtained by Malovickij (1971, pp. 61‒73)), as well as in questions (49). On the other hand, ně-marked pronouns tend to appear with specific uses, in which they have almost no competitors, and in irrealis non-specific uses (50), in which they compete with ljubo- (51) and zero-marked indefinites (52):

-

(49)

мышлѧх же и се гл҃ѧ: есть ли здѣ кто инъ или азъ єсмь єдинъ?

‘I was thinking, saying the following: is there anyone else here, or am I alone?’ (Life of Andrew the Fool)

-

(50)

ѻн же мнѧ,

ко ѥдинъ ѥсть ѿ нищихъ того дѣлѧ стоить, дабы взѧлъ ѹ него нѣчто, и ре(ч̑) ѥму: “бъ҃ тѧ помилуи, бра(т̑),

ко ѥдинъ ѥсть ѿ нищихъ того дѣлѧ стоить, дабы взѧлъ ѹ него нѣчто, и ре(ч̑) ѥму: “бъ҃ тѧ помилуи, бра(т̑),  ко не имѣю ти что вдати”

ко не имѣю ти что вдати”‘But he was thinking that [this] was one of the beggars, because he was standing to take something from him, and said to him: “God have mercy on you, brother, because I have nothing to give you!”’ (Life of Andrew the Fool)

-

(51)

а вороти ми товара брата моєго со што любо, а

с тобою буду

с тобою буду‘and give me back my brother’s merchandise with whatever [you] like, and I will be with you’ (Kievan Chronicle)

-

(52)

Се же напсахъ не

ко творити все то, нъ разоума ради, ци коли сѧ что таково пригодить

ко творити все то, нъ разоума ради, ци коли сѧ что таково пригодить‘I wrote this, not to do all of this, but to be aware if ever some of this should be of use’ (Questions of Kirik)

Thus, the ně- indefinites behave similar to the modern Russian -to-series, which competes with the nibudʹ-series in irrealis non-specific uses in a similar way (however, unlike the to-series, the ně- indefinites also occur as markers of half-definiteness) (53).

-

(53)

Если он что-нибудь / что-то утаил, он за это поплатится

‘If he hid something, he will pay for it’ (Padučeva, 2015)

-

(54)

Если возникнут какие-нибудь / какие-то проблемы, звони

‘If any problems arise, call’ (Padučeva, 2015)

The irrealis non-specific context should be considered the main field of competition between different types of OES indefinite pronouns. Another field where the uses of OES indefinites also intersect is the free-choice context, cf. (55–56).

-

(55)

остави дѣло земльноѥ коѥ любо и иди на дш҃евьнѹю пиштю съ тъштѧниѥмь, акы петръ [и] їѡанъ къ гроб

‘leave behind any earthly work and go to the spiritual food with zeal, as Peter [and] John [fled] to the tomb [of Christ]’ (1076 Izbornik of Svjatoslav)

-

(56)

р(ч̑)е вьзрѣвъ на нь […] сверзи коверъ ли что ли что постьлати, или чимъ прекрыти г(с̑)на нашего

‘said looking at him […] throw off the carpet or something that [one can] lay down [as bedding] or with which [one can] cover our master’ (Kievan Chronicle)

We have few examples of free-choice interpretation of OES indefinites. Nevertheless, some observations can be made. Indefinites used in the free-choice contexts appear in slightly different contexts. Ljubo-indefinites can appear in contexts emphasizing a diversity of elements in the set, i.e. in contexts with concessive meaning similar to the propositions with the emphatic particle ‘even’ (cf. the right-hand context in (57) where this meaning is reinforced with an emphatic particle ni ‘even’). In our examples, ljubo marks the maximum degree of the value (‘even’), cf. examples (57‒59).

-

(57)

бѣаше бо єпифанъ прем

дръ велми, нъ

дръ велми, нъ  коже бѣаше славныи ѻндрѣи, єпифанъ не бѣаше: ст҃ымъ дх҃мъ

коже бѣаше славныи ѻндрѣи, єпифанъ не бѣаше: ст҃ымъ дх҃мъ  зыкомъ иноплеменьны(х̑) гл҃ше и толковаше, єже кто любо хотѧше, ни ѿ прем

зыкомъ иноплеменьны(х̑) гл҃ше и толковаше, єже кто любо хотѧше, ни ѿ прем дрости книжны

дрости книжны не ѹта

не ѹта шесѧ єм

шесѧ єм ничтоже

ничтоже‘Epiphanius was very wise, but Epiphanius was not like the glorious Andrew: [the latter] spoke foreign languages due to the Holy Spirit and knew how to interpret what anyone wanted, and nothing was hidden from him even from the book wisdom’ (Life of Andrew the Fool)

-

(58)

в та бо лѣта всѧко зла(т̑), ѥже ѥсть кдѣ любо съкровено, повелѣньѥмь би҃имь

витьсѧ

витьсѧ‘for in those years, all the gold that is hidden somewhere [= even in the most hard-to-reach places] will be revealed by God’s command’ (Life of Andrew the Fool)

-

(59)

Аште достонии казни бѹ[дѹть при коѥ]и любо винѣ, то въ того мѣсто по[ми]ловани да бѹ[дѹ]ть

‘If they deserve to be punished for any fault [=even the hardest fault], then instead, let them have mercy’ (1076 Izbornik of Svjatoslav)

That is not the case for zero-marked indefinites. They do not occur in pure free-choice contexts, but mostly in disjunctive contexts (usually with pronouns meaning ‘other’), that is, in those emphasizing the indifference of the choice, with no particular focus on the diversity of the objects:

-

(60)

ко се ѧзыкьмь ли слѹхъмь ли окъмь крадъмь: ли тъштеславиѥмь: ли печѧлию ли ѧростью ли чимь отъ таковыхъ похѹлѧюшт<е се>бе и исповѣдаюштесѧ бѹ҃ такѡ ст҃ыихъ та<и>нъ приѥмлемъ вѣрѹюште:

ко се ѧзыкьмь ли слѹхъмь ли окъмь крадъмь: ли тъштеславиѥмь: ли печѧлию ли ѧростью ли чимь отъ таковыхъ похѹлѧюшт<е се>бе и исповѣдаюштесѧ бѹ҃ такѡ ст҃ыихъ та<и>нъ приѥмлемъ вѣрѹюште:  ко въ очиштениѥ таковыихъ нашихъ грѣсѣхъ приѧтиѥ

ко въ очиштениѥ таковыихъ нашихъ грѣсѣхъ приѧтиѥ‘For when we put ourselves at fault, whether by word or by listening or by secret glances, or through vanity, or sadness, or anger, or any of these sins [= no matter which of them], thus confessing to God, we receive holy the holy mysteries, believing that we receive them for the forgiveness of our sins’ (1076 Izbornik of Svjatoslav)

-

(61)

Мѹчи кого сѹдомъ, а не гнѣвомъ

‘Torture a person [= no matter whom] with condemnation, not anger!’ (Pčela)

In this respect, zero-marked indefinites are similar to modern Russian nibudʹ-pronouns, which are not pure free-choice indefinites but can occur in contexts of disjunction together with the pronoun drugoj ‘another’:

-

(62)

Разве могли бы Дмитриев, или Ксения Фёдоровна, или кто-нибудь другой из дмитриевской родни организовать и провернуть так лихо ремонт дачи, как это сделал Иван Васильевич?

‘Could Dmitriev, or Ksenija Fjodorovna, or some other of Dmitriev’s relatives organize and carry out such a renovation of the dacha as Ivan Vasiljevič did?’ (Jurij Trifonov: Obmen, 1969)

Ljubo-indefinites therefore can emphasize a diversity of objects, and zero-marked indefinites – only indifference to the diversity. In this respect, the former are more similar to the modern Russian by to ni bylo than to the modern Russian libo (for by to no bylo- and libo-indefinites, see Padučeva, 2013, pp. 222‒238). Presumably, this effect of the ljubo-marked indefinites is the consequence of the original meaning of ljubo ‘pleasing’, which is associated with a choice anchored not to the speaker but to another discourse referent (in 58, the discourse referent may choose the most hard-to-reach place; in 59, – the hardest fault).

Whereas modern Russian has specialised negative polarity indefinites, OES seems not to feature any specific markers for such contexts. However, all the OES indefinite markers except eter- can occur in contexts of indirect negation and even direct negation, though such usage is sporadic (63–65).

-

(63)

никто(ж҃) ѹбо̀ ѿ ва́съ немо́щно нѣчто да не смы́слить

‘let none of you think of anything weak’ (Alexander Romance)

-

(64)

мы вѣдаѥмъ, ѡже не кончати добро(м̑) с тѣмъ племене(м̑) ни ва(м̑) ни на(м̑) коли любо

‘we know that neither we nor you will never achieve anything good with this kin’ (Suzdalʹ Chronicle)

-

(65)

которого же дн҃i не ѹбь

шеть кого – печаловашеть тогда, коли же ѹбь

шеть кого – печаловашеть тогда, коли же ѹбь шеть кого – тогда веселъ бѧшеть

шеть кого – тогда веселъ бѧшеть‘on any day [he] did not kill anyone, then [he] was cheerful – [he] was sad when [he] killed someone’ (Volhynian Chronicle)

However, this does not mean that indefinites have no restrictions in this respect and can be used in any negative context. We do not have many examples at our disposal, but all the examples with clausemate negation meet the conditions for nonveridicality, or suspended assertion (Padučeva, 2015). Nonveridicality is marked by the modal particle da ‘let’ in (63), by the irreal modality of the infinitive clause in (64), and by iterativity in (65), which generates a distributive situation repeated with different participants. The same conditions explain the ability of -nibudʹ-indefinites to occur in contexts with direct negation in modern Russian (Padučeva, 2015).

The corpus data enable us to create the following semantic map for Old East Slavic indefinites. On the map, we take into account only the most common uses of indefinites; marginal uses are not included in the functional space covered by high-frequency markers such as ně and zero-. The pronouns with ljubo are still in the process of being grammaticalized and do not allow us to make any definite conclusions. However, ljubo is the only marker attested in pure free-choice contexts. At the same time, it exhibits a tendency to take over the space on the left of the semantic map. This space has been indicated with a dotted line. The marker eter- has not been added to the map, since the status of this marker is artificial and the data are very scarce (Fig. 2).

4.3 Discourse factors

In this subsection, we discuss the role of discourse-related factors in the choice of a particular marker. These factors include the degree of formality (higher- and lower-code contexts), the type of discourse (deictic, irrealis discourse or narration), and the factor of originality (original or translated text).

The OES corpus is not balanced with regard to the number of higher- and lower-code sources and contexts, i.e., the number of higher- and lower-code sources and contexts are not equal. We will thus compare the frequency of our indefinite markers in different discourse types with the average frequency of a particular indefinite marker in the dataset. We have italicized the number of cases where the relative frequency is significantly (i.e. more than 30%) lower and indicated in bold the number of cases where the relative frequency is noticeably (i.e. more than 30%) higher than the percentual share of the respective marker in the dataset (Table 4).

Indefinite markers in higher-code contexts do not deviate much from the average level. Significant deviations affect only contexts with a lower code. The ně-marked indefinites are very unlikely to occur in such contexts, and no attestations of eter- can be found in contexts with informal vernacular features. At the same time, the frequency of zero- and ljubo-marked indefinites is significantly higher in contexts with low-code markers.

The choice of an indefinite is not determined to a large extent by discourse factors. Nevertheless, several tendencies can be observed. For instance, ljubo-marked indefinites rarely occur in narration and are much more frequent than average in irrealis discourse. The discourse-related distribution of zero-marked indefinites is even more worthy of note: they tend to occur in deictic discourse and are found with less-than-average frequency in narrative and irrealis discourse. Low frequency in narrative discourse is expected for markers of non-specific reference. With respect to ně-indefinites, we observe the opposite tendency: they are more likely to occur in narration than in the deictic discourse. However, all these features may be caused by the reference type. This follows from the fact that non-specific indefinites, unlike specific ones, are not possible in affirmative declarative sentences with a perfective past tense form (see above).

Let us now turn to evaluate the factor of originality. The number of examples with indefinites in translated and original texts is not equal, so the frequency of the markers in original texts and translations should be compared to the respective percentual share in our dataset (we have used the same formatting to indicate strong deviations from the respective percentual share) (Table 5).

Comparing the average frequency with the frequency in original and translated texts, we see that the translations do not significantly deviate from the average in the corpus, except with respect to eter-. Given the overall low numbers for eter-, these results should not be overinterpreted. However, it should be noted that this pronoun occurs in OES translations only 3 times (cf. also Pičсhadze, 2011, p. 220, p. 245), and all the examples are from the same source, the “Miracles of Saint Nicholas” (66).

-

(66)

цр҃ь же рече имъ. вѣсте ли ѥтера николѹ. тако нарицаѥма? –

‘the king said to them: Do you know a certain [man] called Nicola?’ [Miracles of Saint Nicholas].

This can be explained by the fact that OES translations from Greek fall into several groups according to linguistic features driven by different translation schools or traditions (Pičсhadze, 2011). Pičchadze could not find enough data to identify the place of the Miracles of Saint Nicholas among other OES translations. However, this translation is the only one in our material that uses the indefinite pronoun eter-.

In original texts, the frequency of indefinite markers deviates more significantly from the average. (As we have already shown, this affects the pronoun eter-, as well.) For ljubo- and zero-marked indefinites, it is higher than the average, whereas for the ně-marked indefinites, the frequency is extremely low.

Ljubo-marked indefinites occur in a limited number of translations. No attestations can be found in such large-volume sources as the Aleksander Romance, the History of the Jewish War, or the Pčela. They occur primarily in texts where a significant part is made up of direct speech or prophecies (Life of Andrew the Fool, Tale of Ahikar), for example (67).

-

(67)

ст҃ць ре(ч̑): “а єгда кто любо ѡтвержетьсѧ дѣлъ вашихъ, єже б

деть дѣ

деть дѣ лъ прѣже, како то терпѣть, добле ли ци люто?”

лъ прѣже, како то терпѣть, добле ли ци люто?”‘the saint said, “and when someone renounces your deeds, which he did before, how does he endure it, courageously or dreadfully?”’ (Life of Andrew the Fool)

Ně-indefinites occur rarely in original writing. There are a few examples in birchbark letters, in the writings of Cyril of Turov, and in hagiographic sections of the chronicles. Some of these examples are citations from Holy Scripture (68–69).

-

(68)

ре(ч҃) г(с҃)ь: члв҃къ нѣкто домовитъ бѣаше, иже насади виногра(д҃) и остѣни ѥго оплотомь [cf. Mt. 21:33]

‘said the Lord: there was a certain man, a master of a house, who planted a vineyard and put a wall around it’ (Parable on the Soul and the Body)

-

(69)

наслажаютьсѧ ѹчени

бж(с)твенаго гласа,

бж(с)твенаго гласа,  коже бо нѣкто землю разореть, другыи же насѣеть, инии же пожинають и

коже бо нѣкто землю разореть, другыи же насѣеть, инии же пожинають и  дѧть пищу бескудну

дѧть пищу бескудну‘they enjoy the teachings of the divine voice, that one will plow the earth, the other will sow, and the others will reap and eat rich food’ (Primary Chronicle)

4.4 Role of individual sources

The following descriptive chart shows the overall relative frequency of any overt (i.e. non-zero-marked) indefinite markers in each of the sources used.Footnote 10 A high percentage means that predominantly overt indefinite markers are used, while a low percentage means that the zero-markers are predominantly used. As can be seen, there are some translated sources (represented by the black bars) with a very high percentage of overt indefinite markers (Fig. 3).

The overall percentage of overt indefinite markers in translated sources is slightly higher than in original sources, with the notable exception of the Suzdalʹ chronicle. However, as can be seen, inter-source variation is high, especially when focusing on the translated sources, suggesting that the factor original vs. translation is not a suitable predictor for the use of overt indefinite markers.

4.5 Chronology and exploratory statistics

Using the multinom function from the nnet package in R, we fitted several multinomial logistic regressions with marker as the multinomial response variable and date as well as one other variable (such as originality or referential type) as predictor variables, in order to evaluate the role of these variables, above all, the date variable. Some of the multinomial regressions fitted suggest that the date variable plays a role (i.e. the zero marker as well as the ně type of universal reference seem to rise with time). However, since the results were predominantly not statistically significant, we resolved not to report the results of the multinomial regressions.

The structure of our data, with many low-number variables, thus seems to call for a different statistical method than (multinomial) logistic regression. Recently, random forests have gained popularity in modern quantitative linguistics. Random forests are a robust, exploratory method from the field of machine learning and are used to classify complex data with many potentially relevant variables. The method works as follows:

“Random forests […] work through the data and, by trial and error, establish whether a variable is a useful predictor. The basic algorithm used by the random forests constructs conditional inference trees. A conditional inference tree provides estimates of the likelihood of the value of the response variable […] on the basis of a series of binary questions about the values of predictor variables.” (Baayen & Tagliamonte, 2012, p. 159)

Random forests construct many conditional inference trees, each of them based on a random subset of the data. In this way, the results of the classification are more reliable than that found in a single tree. For our dataset, the results (produced with the R party and randomForestExplainer (Paluszynska et al., 2020) packages, 2,000 iterations) are as shown in Fig. 4.

The predictors farthest to the left are the most important ones, in the sense that these predictors are found statistically closer to the roots of the classification trees, and therefore are responsible for a larger number of the splits in the dataset. This means that date is not among the most important predictors, suggesting that language-internal factors such as the semantic or referential type play a more important role. While clearly relevant for other linguistic variables in the time period covered by our study, the variable date does not seem to have much of an effect on the choice of indefinite markers.

While individual sources have a certain impact, whether or not the source containing the respective indefinite marker is an original work or a translation does not have any significant effect.

The most important factors determining the choice of indefinites can be seen in the visualization in Fig. 5 (for more specific information on how to interpret random forest visualizations, see https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/randomForestExplainer/vignettes/randomForestExplainer.html).

The farther to the upper right the respective variable, the more important it is, in the sense that the analysis would lose accuracy if it were omitted. Interestingly, despite being relatively far up on the right, the p-value of the referential type is greater than 0.1, which means that it is not statistically significant. This leaves us with a single most important predictor of the choice of an indefinite marker: semantic type. Thus, we have empirically established that the data analysed conforms well to Haspelmath’s semantic map, suggesting that his classification is superior to competing classifications.

5 Conclusion

In our analysis of indefinite pronouns in OES, we made use of a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods and applied statistical tools to the OES data.

Contrary to one of our hypotheses, the diachronic factor does not play a dominant role, nor does the formality of the texts or whether or not they are original works. The absence of any significant changes during the whole OES period means that the crucial restructuring in the system happened later, in the Middle Russian period (15th–17th centuries) when the new series of indefinites were grammaticalizing. This can be explained by the fact that no new indefinite markers came into being during the period in question. Internal factors, such as, first and foremost, semantic type, are more important in determining the choice of indefinite pronouns than external factors such as time. The only language-external factor with some degree of importance was the individual source. Therefore, we can conclude that separate subsystems of indefinite pronouns were not a feature of Church Slavonic and East Slavic vernacular texts.

In future studies, the somewhat unexpected result that such factors as date, formality, or original vs. translation play only a minor role in explaining linguistic variation in OES, should be statistically tested against other linguistic phenomena using the same methods applied in the current study. It may allow us to distinguish between linguistic phenomena that are more susceptible to being affected by factors such as tradition, formality or originality and the ones that are more resistant to them. The results of our analysis are also important for further typological and diachronic studies of indefinite pronouns, since in our case, the choice of a particular marker depended only to a very small extent on the influence of tradition or originality, being instead determined primarily by the internal logic of the language system.

Data Availability

The main sources of data for both quantitative and qualitative analysis are historical subcorpora of the Russian National Corpus.

Code Availability

The code for statistical analysis was written in RStudio using the R packages nnet, party and randomForestExplainer, among others.

Notes

Here and below, the sources of the examples will be given from the RNC unless otherwise specified.

The ĖSSJa mentions only the combination jede kyj. There is a construction employing this combination in modern Bulgarian. According to Miklosich, the combination is attested in Bulgarian and Serbian manuscripts, but there are no traces of it in OCS texts (cf. SJS). Unlike eter-, it was not borrowed into OES, and there are no attestations of it in East Slavic written texts. Miklosich also gives evidence for another combination, jede čьto, similar to the previous one. This combination cannot be found anywhere in OES (cf. SRJa XI, SDRJa III, and RNC), except for a sole example cited by Miklosich: Но срѣтаемъ брата иного и абiе глаголемъ емоу еде что и еде что бысть ‘But we meet another brother and suddenly tell him: this and that happened (?)’ [perhaps mistakenly for eda čьto?] (Izv. 1856, p. 208). This citation was taken from the 16th century “Discourse” of Metropolitan Daniil, though Miklosich erroneously has a reference to an 11th century Menaion. We can hardly draw any conclusions based on one occurrence only, but in the example cited, the context exactly matches those in which indefinite pronouns with the marker edi are used in modern Bulgarian. In Bulgarian, edi serves as a marker of so-called “secondary indefiniteness”, that is, it is used in the context of reproduced speech (Nicolova, 2008, p. 202‒203).

A diachronic semantic map is a map that contains arrows showing the directions of the semantic development of a gram (cf. the diachronic semantic map of universal quantifiers in Tatevosov, 2002, p. 175).

Loss of focusing and desemanticization.

For recent developments in statistical tagging of pre-modern Orthodox Slavic that takes into account both orthographic variation and grammatical homonymy, see Scherrer et al., 2018.

Non-referential use of indefinites is also possible, such as use of indefinites in a predicative function, or the so-called discourse uses; the meaning of indefinites in such constructions is labelled as ‘appreciative’ by Haspelmath (1997, pp. 186‒189), cf.: Такоже и жены безъ мѹжии мнѧтьсѧ нѣчто, а при мѹжехъ своего величани

ѿ

ѿ ти сѹть ‘also wives without husbands are considered [to be] something [important, significant], while with their husbands they are deprived of their significance’ (Pčela); Не мнисѧ что, егда твориши добродѣтель ‘do not consider yourself something [important, significant] when you do a good deed’ (Pčela).

ти сѹть ‘also wives without husbands are considered [to be] something [important, significant], while with their husbands they are deprived of their significance’ (Pčela); Не мнисѧ что, егда твориши добродѣтель ‘do not consider yourself something [important, significant] when you do a good deed’ (Pčela).Both criteria are described by Haspelmath (1997, pp. 38‒39) among some other diagnostic paraphrases, which are inaccessible for the historical data.

This criterion is used in Haspelmath (1997, pp. 48‒49).

OCS may provide evidence for an earlier stage of the semantic development of indefinites in Slavic.

For this graph, we omitted the sources with a very low overall number of indefinite markers.

Sources

ĖSSJa – Ėtimologičeskij slovarʹ slavjanskich jazykov. Praslavjanskij leksičeskij fond. O. N. Trubačev (Ed.). Vyp. 8 (*ха – *jьvьlga), Moskva 1981; Vyp. 15 (*lětina–*lokačь), Moskva 1988; Vyp. 24 (*navijati(sę)/navivati(sę) – *nerodimъ(jь)), Moskva 1997.

Izv. – Izvestija Otdelenija russkogo jazyka i slovesnosti (Vol. 5 Vyp. 4). Sankt-Peterburg 1856.

Merilo pravednoe po rukopisi XIV v. Izd. pod nabljudeniem i so vstupitelʹnoj statʹej M. N. Tichomirova. Мoskva 1961.

NKRJa – Russian National Corpus. http://ruscorpora.ru.

SDRJa 4 – Slovarʹ drevnerusskogo jazyka (XI-XIV vv.). Moskva 1988–.

SJS II – Slovník jazyka staroslověnského. Lexicon linguae palaeoslovenicae. Praha 1973.

SRJa – Slovarʹ russkogo jazyka XI–XVII vv. Moskva 1975–.

References

Baayen, H., & Tagliamonte, S. A. (2012). Models, forest, and trees of York English: Was/were variation as a case study for statistical practice. Language Variation and Change, 24(2), 135–178.

Bylinina, Е. G., & Testelec, Y. G. (2005). O nekotorych konstrukcijach so značeniem neopredelennych mestoimenij v russkom jazyke: amalʹgamy i kvazireljativy. In Seminar «Teoretičeskaja semantika». Moskva: Institut problem peredači informacii RAN.

Fasmer, M. (2004). Ėtimologičeskij slovarʹ russkogo jazyka: V 4-ch t.: Per. s nem. = Russisches etymologisches Wörterbuch / Perevod i dopolnenija O. N. Trubačëva (4-е izd.). Мoskva: Astrelʹ – АSТ.

Geist, L. (2008). Specificity as referential anchoring: evidence from Russian. In A. Grønn (Ed.), Proceedings of SuB12 (pp. 151–164). Oslo: ILOS.

Haspelmath, M. (1997). Indefinite pronouns. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Haspelmath, M. (2003). The geometry of grammatical meaning: semantic maps and cross-linguistic comparison. In M. Tomasello (Ed.), The new psychology of language (Vol. II, pp. 211–242). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Křížková, H. (1974). Neurčitá záimena typu kdo v současných slovanských jazycích. Jazykovedné stúdie, 12, 88–95.

Krys’ko, V. B., Kuznecov, А. М., & Penkova, Y. А. (2020). Mestoimenija. In V. B. Krysʹko (Ed.), Istoričeskaja grammatika russkogo jazyka: Ėnciklopedičeskij slovarʹ (pp. 172–189). Мoskva: Azbukovnik.

Kustova, G. I. (2015). Pragmatičeskie faktory v reducirovannych konstrukcijach: kvazireljativy tipa “čto chočešʹ”. Vestnik Novosibirskogo gosudarstvennogo pedagogicheskogo universiteta, 5(27), 122–133.

Kuz’mina, S. М. (1989). Semantika i stilistika neopredelennych mestoimenij. In D. N. Šmelev (Ed.), Grammatičeskie issledovanija. Funkcionalʹno-stilističeskij aspekt (pp. 158–231). Мoskva: Progress.

Majer, M. (2015). A lovely alternative: Proto-Slavic *ljubo. In E. Mańczak-Wohlfeld & B. Podolak (Eds.), Words and dictionaries. A festschrift for Professor Stanisław Stachowski on the occasion of his 85th birthday (pp. 193–203). Kraków: Jagiellonian University Press.

Malovickij, L. (1971). Voprosy istorii predmetno-ličnych mestoimenij (kto, čto). Učenye zapiski Leningradskogo gosudarstvennogo pedagogičeskogo instituta imeni A. I. Gercena, 517, 3–130.

Miklosich, F. (1862–1865). Lexicon palaeoslovenico-graeco-latinum: emendatum auctum. Vienna: Braumüller.

Miklosich, F. (1886). Etymologisches Wörterbuch der slavischen Sprachen. Wien: Braumüller.

Moldovan, А. А. (2000). Žitie Andreja Jurodivogo v slavjanskoj pisʹmennosti. Мoskva: Azbukovnik.

Nicolova, R. (2008). Bălgarska gramatika. Morfologija. Sofija: Sv. Kliment Ohridski.

Padučeva, Е. V. (1985). Vyskazyvanie i ego sootnesennostʹ s dejstvitelʹnostʹju (referencialʹnye aspekty semantiki mestoimenij). Мoskva: Nauka.

Padučeva, E. V. (2013). Russkoe otricatelʹnoe predloženie. Мoskva: Jazyki slavjanskoj kulʹtury.

Padučeva, E. V. (2015). Nereferentnye mestoimenija na -nibudʹ. Materialy dlja proekta korpusnogo opisanija russkoj grammatiki (http://rusgram.ru). Na pravach rukopisi. Мoskva.

Padučeva, E. V. (2016). Mestoimenija slaboj opredelennosti (serija na koe-, serija na ne-, odin). Materialy dlja proekta korpusnogo opisanija russkoj grammatiki (http://rusgram.ru). Na pravach rukopisi. Мoskva.

Paluszynska, A., Biecek, P., & Jiang, Y. (2020). randomForestExplainer: explaining and visualizing random forests in terms of variable importance. R package version 0.10.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=randomForestExplainer.

Penkova, Ya. A. (2011). Imperativ budi v pamjatnikach XV veka: k voprosu o formirovanii neopredelennych mestoimenij na -nibudʹ v russkom jazyke. Russkij jazyk v naučnom osveščenii, 1(21), 251–265.

Penkova, Ya. A. (2016). Neopredelennye mestoimenija s formantami nibudʹ i libo/ljubo v istorii russkogo jazyka XV‒XVII vv.: korpusnoe issledovanie. In El’Manuscript–2016. Rašytinis palikimas ir informacinės technologijos. VI tarptautinė mokslinė konferencija. Vilnius, 2016 m. rugpjūčio 22–28 d. Pranešimai ir tezės (pp. 280–284). Vilnius–Iževskas: Vilniaus universitetas.