Abstract

I explore the ongoing language change in which the impersonal modal word možno ‘can, be possible’ takes a personal clause (možno + nom) as its complement instead of the Experiencer in the Dative case (možno + dat) and the infinitival clause in the speech act of request in Contemporary Russian. The corpus-based evidence reveals that the construction možno + dat is gradually being replaced by možno + nom. I discuss various syntactic and pragmatic factors such as verb class, aspect, transitivity and politeness strategies that motivate the choice of a specific modal construction. Methods of statistical modelling, used to sort out the most significant factors contributing to the choice of construction, show that the most important factor is the date of creation of the text. I propose a scenario for the development of the možno + nom construction. First, možno began to be used as a tag-question after both infinitive and personal clauses. The requester marked by the Dative has been steadily replaced by the more agentive Subject in the Nominative case. Then, by analogy with the možno + dat construction, možno was placed at the beginning of the sentence and was reanalyzed as a constructional unit with the following structure: možno + finite clause, in which možno functions as a sentence adverb.

Аннотация

В статье рассматривается процесс языкового изменения, в рамках которого безличный модальный предикатив можно принимает в качестве сентенциального актанта финитную клаузу с субъектом, маркированным именительным падежом, (конструкция “можно + nom”) вместо нефинитной клаузы с экспериенцером, маркированным дательным падежом (конструкция “можно + dat”), в речевом акте просьбы в современном русском языке. На материале корпусных данных прослеживается постепенная замена конструкции “можно + dat” на конструкцию “можно + nom” носителями русского языка как в письменной, так и в устной речи. В статье рассматриваются различные синтаксические и прагматические факторы, которые мотивируют выбор конструкции: семантический класс глагола, аспект, транзитивность, стратегии вежливости. Методы статистического моделирования, использованные для определения наиболее значимых факторов, влияющих на выбор конструкции, показывают, что наиболее значимым фактором является год создания текста. В статье предложен сценарий появления конструкции “можно + nom”: сначала предикатив можно использовался после финитных и нефинитных клауз в качестве вопросительного слова. В дальнейшем в нефинитных конструкциях адресант, маркированный дательным падежом, постепенно был заменен на более агентивный субъект, маркированный именительным падежом. Затем по аналогии с конструкцией “можно + dat” предикат можно был помещен в начало предложения и вместе с следующей за ним финитной клаузой был переосмыслен как новая конструкция “можно + finite clause”, в которой можно выступает в роли сентенциального наречия.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Russian modal words or modalsFootnote 1 denoting possibility and necessity form a syntactically heterogenous class that includes the personal modal verb moč’/smoč’ ‘be able’, the personal adjectival predicate dolžen ‘must’, and impersonal adverbial predicates možno ‘can, may, be possible’, nel’zja ‘not allowed’, nado/nužno ‘have to’ etc. In these modal constructions, personal predicates require a Subject in the Nominative case, whereas impersonal predicates require an Experiencer in the Dative case. Modal words are matrix predicates, i.e., modal words can have at least one sentential complement. Typically, the sentential complement is an infinitive phrase.

Russian displays several possibilities for formulating a request. A request is an illocutionary act in which “a speaker (requester) conveys to a hearer (requestee) that he/she wants the requestee to perform an act which is for the benefit of the speaker” (Trosborg, 1995: 187). The speaker may request non-verbal goods or services, e.g., an object or an action, or verbal goods and services, e.g., information or permission to carry out an action.

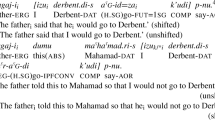

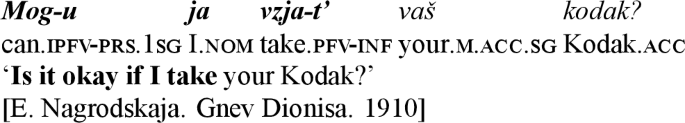

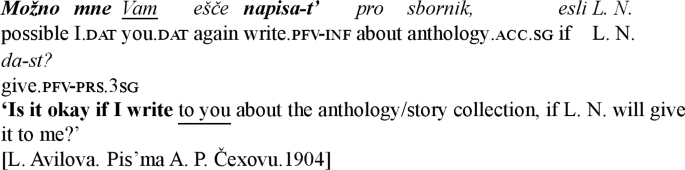

This article offers an analysis of two syntactic variants of a construction with the modal adverb možno ‘can, may, be possible’, namely možno + dat + inf, hereinafter “možno + dat”, and možno + nom + v.fin,Footnote 2 hereinafter “možno + nom”, which are used to formulate speech acts of request in contemporary Russian. While in the former construction možno is used with an Experiencer in the Dative case and an infinitive, in the latter možno lacks an Experiencer and instead takes a personal clause as a sentential complement. I will provide evidence that the construction with an Experiencer marked by Dative as in (1a) is gradually being replaced by možno + nom as in (1b). In examples like (1b) možno functions as a sentence adverb, i.e., an adverb that modifies the content of the clause in which it occurs, see Ramat and Ricca (2011).

-

(1)

Following Goldberg (2006: 5), I define a construction as a “learned pairing [of] form with semantic meaning or discourse function including morphemes or words, idioms, partially lexically filled and fully general phrase patterns”. I am interested in variation in the linguistic expression of a requester (a semantic Subject), and henceforth I will term the options illustrated by (1a)–(1b) dat–nom variation. In this article, I define variation in a narrow sense as two or more possible grammatically acceptable ways to express the same meaning by a speaker of a given language.

I suggest that the request formula with a Subject in the Nominative has developed in Russian under the influence of both syntactic and pragmatic factors. First, možno demonstrates relative syntactic freedom: možno can appear unconnected to any surrounding syntax as in (2).

-

(2)

In such examples the speaker asks permission by using the modal word možno, which refers to a situation that is indicated by non-verbal means. In example (2) the speaker communicates to the hearer that he wants to drink by merely pointing at the decanter. Thus, the dat–nom variation is facilitated and motivated by utterances in which the action desired by the speaker does not have an overt linguistic expression.

Second, requests for permission to carry out an action can be expressed by several modal constructions. The best-known constructions involve the two constructions with the modal adverb možno ‘can, may, be possible’ as in (1a) and (1b); a personal modal verb moč’ ‘be able’ as in (3) and an impersonal modal adverb nel’zja ‘not allowed’ combined with the particle li ‘whether’ as in (4). Another way to formulate a request is to pose a direct question as in (5).

-

(3)

-

(4)

-

(5)

Requests with the personal construction with the modal verb moč’ ‘be able’ as in (3) and direct question as in (5) might support the ongoing dat–nom change. Speakers have access to all the resources that encode requests, so exposure to the personal constructions that are used for the same pragmatic purposes can be another factor contributing to the ongoing language change.

Third, a speech act of request is a face-threatening act in which the speaker “attempts to exercise power or direct control over the intentional behavior of the hearer” (Trosborg, 1995: 188). At the same time the speaker exposes herself to the risk of being embarrassed if the hearer refuses to comply with her wishes. By using an indirect request with an impersonal modal construction, the speaker mitigates her power over the hearer, but simultaneously the speaker makes herself more vulnerable. My hypothesis is that by using a personal form such as možno + nom in a request for permission to carry out an action, the speaker secures her freedom to perform an action and desire to be respected by other members of the community.

I examine factors that are associated with the choice of construction, including any formal or pragmatic restrictions that would prompt a speaker to choose one of these constructions, taking into account external factors such as native speakers’ personal preferences. I will provide evidence demonstrating that možno is changing its argument structure to accept a personal clause as a sentential complement (možno + nom) instead of an infinitive phrase with an Experiencer in the Dative case (možno + dat).

This is a corpus-based quantitative study. For the purposes of this article, I will use two datasets: one based on written texts from the Russian National Corpus, hereinafter the RNC, (main database) and the other based on data retrieved from the spoken subcorpus of the RNC (supplementary database). The data will be analyzed separately since the datasets cover different time periods.

The article is structured as follows. In Sect. 2, I provide a brief overview of background information about modals that are used in speech acts of request in Russian, focusing on the constructions možno + dat and možno + nom. In Sect. 3, I describe the main dataset, explaining how the data was obtained and annotated. The analysis of the data is presented in Sect. 4. The results of statistical modelling are explained in Sect. 5. Section 6 describes the supplementary spoken dataset and data analysis. Section 7 outlines background information on speech acts of request and politeness theory. In Sect. 8, I discuss the ongoing language change and propose a scenario for the development of the možno + nom construction in terms of cognitive linguistics and constructionalization, see Traugott (2015). Section 9 summarizes the findings.

2 Prior scholarship on možno + dat and možno + nom

The origin of the word možno is obscure, however in the scholarly literature we find various alternative descriptions of how this word found its way into modern Russian. Kopečný and Havlová (1981) and Šanskij et al. (1961) claim that možno derived from an adjective možьnъ ‘possible’ which in its turn was derived from the Proto-Slavic noun moga ‘power’. According to Vaulina (1988) možno is first documented in the Russian language in the 15th century in “Gramota velikogo knjazja Vasilija Vasil’eviča pol’skomu i velikomu litovskomu knjazju Kazimiru” (1449) in the negated form nemožno. Besters-Dilger (1997) considers this usage of nemožno a mistake or a Polish borrowing. In the middle of the 17th century the word možno appears in texts along with its derivational relatives možnyj ‘possible’ and možnost’ ‘possibility’ and steadily replaces the Old Slavic lexemes močno (mošno) and moščno that existed along with their negative counterparts nemočno (nemošno) and nemoščno since the 12th century and were used to express participant-external and deontic modal meanings.

Besters-Dilger (1997) treats možno as a contamination of the Russian modal words močno, moščno, vozmožno and the Polish impersonal modal word można. Kochman (1975) denies any connection between the Old East Slavic lexemes and Russian možno and claims that možno is a lexeme that was directly borrowed from Polish into Russian. Besters-Dilger’s hypothesis is more convincing: it is most likely that možno was formed under the influence of Polish, but the presence of lexemes with almost the same meaning, morphology and functional load in the Old East Slavic language must have had an impact as well.

There existed at the same time another pair of modal words with similar semantics: l’zja ‘to have conditions or right to act in a certain way’ and nel’zja ‘not to have conditions to act in a certain way due to the external factors’. The usage of nel’zja significantly increased and nel’zja spreads to contexts where nemožno (nemočno, nemošno or nemoščno) appeared previously. Meanwhile l’zja was steadily replaced by možno. Thus, in Contemporary Standard Russian the paradigm was reduced to an opposition formed by two suppletive members, namely možno ‘possible’ and nel’zja ‘impossible’.

In summary, the modal word možno appeared relatively recently in Russian, with the very specific meaning ‘to have conditions to carry out an action’ taking the place of Old East Slavic lexemes that shared the same semantics but had different functional and stylistic distribution.

In contemporary Russian možno can express deontic or participant-external modal values according to the logical-based semantic map classification proposed by Van der Auwera and Plungian (1998). In this research I treat modality in a narrow way as an opposition of possibility and necessity. Deontic possibility is permission, while participant external possibility is defined as “circumstances that are external to participant engaged in the state of affairs and that make this state of affairs possible” (Van der Auwera & Plungian, 1998: 80).

Functionally možno can express possibility and permissibility. Možno per se is an impersonal modal word, i.e., it does not allow a Subject in the Nominative case and requires an Experiencer in Dative, as opposed to the personal modals (e.g., the verbs moč, smoč ‘be able’) that agree with their Subject. However, the Experiencer in the impersonal construction with možno can be overtly expressed, as in (6) or elided, as in (7).

-

(6)

-

(7)

One of the attested properties of impersonal modals is that when they are used without an Experiencer, the possibility applies to every participant involved in the situation: “The possibility is universal – it could apply to anyone” (Timberlake, 2004: 382). If the speaker wants to specify who can or cannot carry out an action, the speaker must overtly mark the Experiencer. A corpus study by Grillborzer (2019) demonstrates that overall constructions with the modal možno tend to be used with an elided (non-overt) Experiencer. The distribution in her dataset is as follows: 6 constructions with an Experiencer in the Dative case vs. 1790 constructions with an elided Experiencer. The same tendency is discovered for modals nado and nel’zja. Grillborzer (2019) suggests that modals možno, nado and nel’zja gravitate towards being used in impersonal constructions because the Russian language already has the modal verb moč’ that is used in personal constructions.

However, when možno is used in requests it behaves differently. Example (7) shows that in requests možno can be used without an overt Experiencer yet possibility is applied to only one specific participant. In this article, I will call examples with the elided Experiencer, as in (7), modal constructions with covert Dative (možno + cdat) since the Dative Experiencer is unambiguously recoverable.Footnote 3

Furthermore, the verb itself can be elided when a speaker requests an item (8).

-

(8)

To the best of my knowledge, there is little previous scholarship on the dat–nom variation, see (1a) and (1b). Scholars have mostly focused on the properties of impersonal uses of možno. Beljaeva (1990: 123–140) provides examples exclusively with the možno + dat construction. Padučeva (2016) lists examples with both constructions without any explanatory remarks. In the most recent corpus study on various modal meanings and their constructions, Lyashevskaya et al. (2017), in describing the annotation of their dataset, also mention in passing that možno can be used both with Nominative and Dative. Dubinina and Malamud (2017) made a study of how requests are formulated in Russian heritage language. As a baseline for their research, Dubinina and Malamud searched the spoken subcorpus of the RNC for various request formulas including requests with the modal možno. Such requests were treated by the authors as impersonal modal constructions, however the examples that are used in the article contain requests formulated mostly with možno + nom.

Choi (1994: 178) treats možno as an impersonal modal adverb and argues that možno is the only modal word that can be used to formulate requests for permission to carry out an action. According to Choi (1994) možno is not interchangeable with moč’ in the speech act of request.Footnote 4 I will argue that requests can be formulated with the modal verb moč’, as in (9a), (9b) and (9c), as well as with možno, although the usage of moč’ might be less frequent in such contexts.

-

(9)

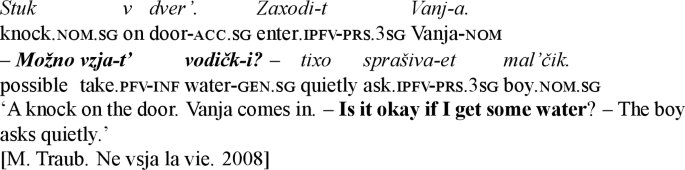

Švedova et al. (1980: 214) list možno among other impersonal modal words such as nel’zja ‘must not’, nado/nužno/neobxodimo ‘have to’ etc. and mention that možno can be used with or without an Experiencer. In a footnote in a section about particles, Švedova et al. (1980: 388) admit that možno can also be considered to be an interrogative particle that, when combined with a future tense verb form, is used to formulate a request as illustrated by examples from literary works:

-

(10)

-

(11)

Hansen (2001: 170) also refers to možno when used in requests as a modal particle that expresses courtesy. Thus, both Švedova et al. (1980) and Hansen (2001) posit two homonymous modal words možno: one is a modal adverb možno with or without an Experiencer in the Dative case, and the other is an interrogative particle možno used with the Subject in the Nominative case. This decision might be convenient for the purposes of descriptive grammar; however, the term “particle” lacks accuracy. Particles are usually negatively defined as “the words left over when all the others have been assigned to syntactic categories” (Zwicky, 1985: 292). Zwicky (1985) suggests eliminating the word class of particles from the part of speech inventory across the languages of the world, because particles are semantically heterogenous and syntactically diverse. Endresen et al. (2016) claim that the label particle as a part of speech is superfluous for Russian and provide as an alternative a conceptually motivated classification of nine lexemes previously classed as particles, reassigning them to other syntactic categories.Footnote 5

In agreement with Zwicky (1985) and Endresen et al. (2016), I claim that možno should be treated as a modal adverb regardless of the speech act it is used in. First, možno preserves its semantics ‘the possibility to do X’ in all contexts where it occurs. Besters-Dilger et al. (2009: 171) notes that “as modals are the result of grammaticalisation processes their morphology and syntax show traces of the part of speech they originally belonged to.” Therefore, the adverbial origin of možno can be reactivated in requests, i.e., možno transitions from a modal adverb to a modal sentence adverb, cf. lexicalization of možet ‘perhaps’ in Hansen (2010, 2016) (see Sect. 8 for more detail).

Second, Švedova et al. (1980) rely on the written form of language and might be misled by punctuation marks that artificially separate možno from other words in the utterance, while in the natural spoken discourse the speaker usually does not have to pause before or after možno. I will address this issue in more detail in Sect. 6.

In summary, it has been shown in this review that the impersonal modal word možno appeared in the Russian language approximately in the 16th century with the semantics ‘to have conditions to carry out an action’, a meaning that corresponds to the contemporary deontic and external modal readings. The paradigm of možno changed dramatically through a relatively short period of time: možno lost its negative counterpart nemožno and substituted nemožno by another impersonal modal word nel’zja. The original semantics determined the use of the construction možno + dat in requests and permissions. However, the možno + nom construction is mentioned in some studies but briefly so, and there remain aspects of this construction about which relatively little is known. At the same time Russian has direct questions and the personal construction moč’ + (li) + inf that can be used in requests as well.

3 Data

For the purposes of this study, I created two datasets: one based on data in the entire old version of Russian National Corpus which includes texts from the 18th century until the present (main dataset) and the other based on the data in the spoken subcorpus of the RNC which consists of texts from the 20th century until 2016 (supplementary dataset). The data from the spoken corpus reflects how modal constructions are used in natural discourse, in situations when the speaker has less time to check grammatical (prescriptive) correctness compared to written discourse. Therefore, the speaker displays less control over her speech production and chooses the construction unconsciously. In order to perform statistical analysis, I will analyze the two datasets separately due to the lack of data for 18th – 20th century in the spoken subcorpus.

3.1 Main dataset (written corpus of the RNC)

Given that možno is polysemous and can appear at various positions in the sentence (at the beginning or at the end of the sentence, following or preceding the pronoun/noun, the pronoun itself can be elided etc.), I formulated seven specific queries with the modal word možno, main verb and its arguments in order to extract as many relevant examples as possible. These queries yielded 1681 occurrences of možno up to 10 words before a question mark. Second, I manually removed all noise from the raw numbers and annotated the remaining sentences (clean data). As a result, I obtained 953 sentences for analysis. The entire database is publicly accessible from the Tromsø Repository of Language and Linguistics archive (TROLLing) at https://doi.org/10.18710/JXBOQF. The search queries and numbers for clean data for the main dataset are presented in Table 1.

Due to the fact that možno can express various modal meanings (deontic, external and internal possibility) there was considerable noise in the data: almost half of the examples (728 sentences) had to be excluded from the sample. In the majority of cases, sentences were flagged as noise because they were not conventional indirect requests. In the remainder of this section, I will briefly comment the two groups možno + dat and možno + nom mentioned in the Table 1, and illustrate each query with an example.

3.1.1 Možno + dat

The pronoun or noun in the Dative case in the možno + dat construction can follow the modal word možno as in (12), be elided as in (13) and (14), or precede the modal word as in (15) and (16).

možno + pron.dat + inf:

-

(12)

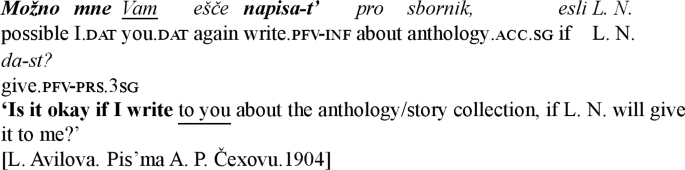

In this subgroup I did not exclude twenty-six sentences with a structure like in (13). Such examples were tagged as examples of the covert Dative case (možno + cdat, where C stands for covert) because vam ‘to you’ does not code the Agent or Experiencer but codes the recipient, i.e., the person to whom the speaker wants to address a question.

-

(13)

možno + inf:

-

(14)

pron.dat + možno + inf:

-

(15)

možno + name.dat + inf:

-

(16)

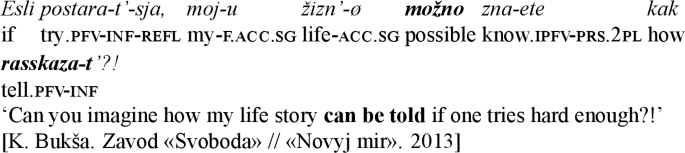

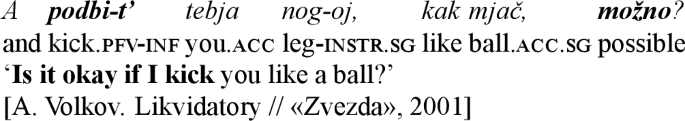

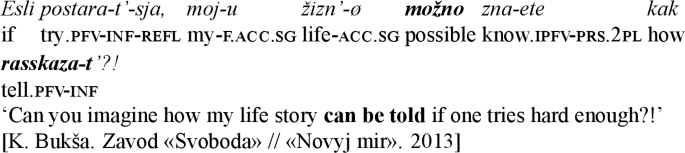

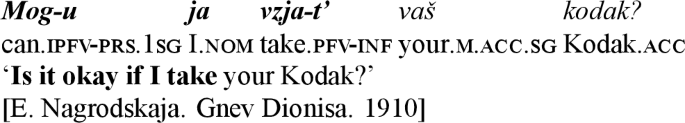

3.1.2 Možno + nom

In contemporary standard Russian, the pronoun or noun in the Nominative case in the construction možno + nom must follow the modal word možno (17), (18). Sometimes the Subject can be elided, but the person is still marked on the verb (19). I will refer to examples like (19) as to constructions with covert Nominative (možno + cnom).

možno + pron.nom + verb:

-

(17)

možno + name.nom + verb:

-

(18)

možno + verb:

-

(19)

3.2 Annotation of data

The annotation of clean data includes both syntactic and semantic features (a–f) and metadata for texts (h–j). The metadata reveals how the constructions are distributed through time in the dataset and, in principle, should reflect how the constructions are distributed across various genres, e.g., the možno + dat construction is expected to be used in formal contexts, while možno + nom would be typical for casual speech. The requests to carry out an action pragmatically are mostly tied to the speaker (first person singular or plural); however, the speaker might as well ask permission for another participant. Tense, aspect, transitivity, possibility of the infinitive or finite verb to have an argument in the Dative case and the semantic class of the predicate might trigger the choice of a more active semantic Subject, i.e., Agent in the Nominative, or a less actively involved Experiencer in the Dative.

Statistical analysis shows that the text creation date is the most important feature that predicts the choice of construction. Examination of text creation date makes it possible to determine when the možno + nom construction appeared in language and how its frequency has changed since.

Punctuation marks to some extent signal whether the speaker interprets možno + nom as a single construction or two constructions: one with the modal adverb možno and the other with a personal clause. However, punctuation rules are prescriptive and like other literary norms do not always reflect the present-day linguistic reality. Genre can also play role in the choice of construction: formal genres might prefer prescriptively correct možno + dat construction.

-

a.

case of the semantic Subject (Nominative or Dative);

-

b.

person and number of the semantic Subject (first singular, first plural, second singular, second plural etc);

-

c.

tense (past, non-past and future);

-

d.

aspect (perfective, imperfective);

-

e.

transitivity;

-

f.

possibility of the infinitive or finite verb to have an argument in the Dative case;

-

g.

the semantic class of the predicate under modality (motion, speech, location etc.Footnote 6);

-

h.

text’s creation date;

-

i.

genre (fiction, journalism, etc);

-

j.

punctuation marks.

I will explore the relationship between the choice of možno + nom or možno + dat constructions and the features listed above. To achieve this, I will examine each factor separately and after that I will apply the statistical method logistic regression. All statistical analyses were carried out using R package{lme4}.

4 Analysis

4.1 Case and person of the semantic Subject

Most of the requests are formulated with the Subject or Experiencer in the first person singular (93.6%). The rest are distributed among the first-person plural (4.1%), the second person singular (0.8%) and the third person singular (1.2%) and plural (0.3%). The distribution of requests according to the semantic Subject’s case, person and number is presented in Table 2.

The most semantically ambiguous examples compared to the other constructions are sentences with the covert Dative, i.e., without an overtly expressed Experiencer. The earliest constructions with covert Dative appeared in my dataset at the same time as the Dative constructions at the beginning of the 18th century, and since then the covert Dative constructions are somewhat more frequent in the language than the Dative (approx. in a ratio of 3:2).

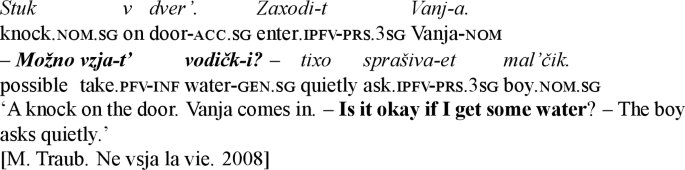

Usually, the modal word možno without an Experiencer is used in impersonal constructions, as in (20). In such examples možno + inf is not a request; the construction expresses the possibility of performing an action. Examples like (20) were excluded from the sample.

-

(20)

However, when možno is used in requests, in most examples the context unambiguously determines which participant is expected to perform an action even if the Experiencer is not overtly expressed as in (21)Footnote 7 or (22).

-

(21)

-

(22)

In example (21) a boy is thirsty, so he asks for permission to take a bottle of water from the refrigerator to quench his thirst. In example (22) a speaker wants to get to know an attractive woman and asks for permission to sit at her table. In requests concerning the first person singular and plural it is almost impossible for the hearer to misinterpret the modal construction even without an overtly present Experiencer. It is pragmatically unlikely that under circumstances as in (21) or (22) the speaker would wonder whether the possibility of performing an action exists in general. In other words, (21) and (22) cannot be understood as ‘Is it possible for anyone to get some water?’ and ‘Is it possible for anyone in the restaurant to sit with you?’ respectively. It is also unlikely to suggest that the speaker might be asking permission for other person, e.g., Možno ej vzjat’ vodički? ‘Can she get some water?’.

I have only five examples in which it is difficult to say whether the speaker requests the hearer to carry out an action or wants to carry out an action himself as in (23) and (24). In (23) a surgeon asks his colleague whether it would be possible to give the corpse of the woman who he operated on to her relatives without an autopsy. It remains unclear whether his colleague, the hospital, or the speaker himself will do this. In (24) Evelina’s son is playing with other children in the park and a gentleman asks to keep the noise down. It is not obvious whether Evelina should ask children to be quiet or the speaker is requesting permission to tell the children off himself.

-

(23)

-

(24)

Taken together these results suggest that there is a strong association between the speech act of request and the first person singular and plural regardless of the type of the construction used: možno + nom, možno + dat, možno + cnom or možno + cdat. However, requests with covert Dative sometimes require more linguistic and extralinguistic (e.g., gestures) support to be correctly interpreted by the hearer.

4.2 Tense, aspect and transitivity

A request is a future-oriented speech act, and, in addition to infinitive forms, there were only non-past perfective and periphrastic future verb forms in the database. Their distribution is as follows: 799 sentences are with perfective verbs (both finite and non-finite forms), 154 sentences are with imperfective verbs (both finite and non-finite forms). The information about tense and aspect of the lexical verb used in requests with možno is given in Table 3.

Seventy-two of the sentences with imperfective verbs include imperfective future forms with an auxiliary verb byt’ ‘be’ and an infinitive, see (25) and (26). Možno is used with a Subject marked in the Nominative case.

-

(25)

-

(26)

The remaining eighty-two sentences are distributed as follows: ten of them contain the future form budet (27); seventy-two of them do not have budet (28).

-

(27)

-

(28)

There are no examples in which možno combines with imperfective future forms with auxiliary verb byt’ ‘be’ and Subject in the Nominative is elided (možno + budu govorit’) in my dataset, but such examples are grammatical and can be produced by speakers in spontaneous discourse.

I classed verbs in my database into transitive and intransitive in agreement with the classification used in the RNC. As a result, I obtained 376 examples with intransitive verbs and 577 examples with transitive verbs. I will use this data in the statistical analysis in Sect. 5.

4.3 The possibility of the infinitive or finite verb to have an argument in the Dative case

Following the distinction proposed by Choi (1994), I will refer to možno as a modal predicate that represents a modal situation and to a complement clause predicate (infinitive or finite verb form) as a dictal predicate that represents propositional content. The Dative case is used in Russian to mark an Experiencer and the Indirect Object of a sentence, i.e., the Recipient. There are 260 examples out of 953 in which a dictal verb takes the Dative to mark the Recipient in the dataset, see (29) and (30).

-

(29)

-

(30)

I did not take into account cases in which verbs, particularly verbs of motion, are followed by the preposition \(k \) ‘towards/to’ and the pronoun in the Dative, because those are arguments of place, not Recipients as in (31).

-

(31)

In 109 out of 260 sentences in the dataset the Recipient of a dictal situation is overtly marked, see Fig. 1. Among those examples there are forty-nine examples with možno + dat as in (32), seventeen examples with možno + cdat as in (33), forty-one examples with možno + nom as in (34), and two examples with možno + cnom as in (35).

-

(32)

-

(33)

-

(34)

-

(35)

The most interesting cases are the examples in which both the modal adverb and dictal verb have their arguments in the Dative case overtly marked as in (32). A sequence of two arguments in the Dative case makes a sentence difficult to interpret by the hearer. Only one such example was found in our data, see (32). The remaining examples tended to separate the Experiencer from the Recipient by the dictal verb as in (36) or by the modal and the dictal verb as in (37).

-

(36)

-

(37)

To sum up, the Recipient marked by Dative appears in both Dative and Nominative constructions. Apparently, speakers tend to avoid structures in which the Experiencer is directly followed by the Recipient in the Dative case as in (38), because such structures require an extra effort to be processed by the hearer. Otherwise, both arguments can be present in the same utterance.

4.4 The semantic class of the predicate under modality

There are 312 unique verbs in the dataset. 131 of them are attested in two or more sentences. For the purposes of this study, I used the semantic classification independently established and annotated by the RNC. However, 109 verbs remain unclassified in the RNC. To avoid bias in the data analysis, these verbs were independently manually classed by an external specialist. The verbs in the data I collected fall into twenty verb classes: creation, existence, change of state, contact, impact, light, location, location of body, mental, motion, motion of body, perception, phasal, physiological, possession, emotion, placement (put), sound, speech and miscellaneous. The miscellaneous verb class includes 39 words that were not classified in the RNC, nor by the external linguist.

The ten most frequent verbs are presented in Table 4. These verbs are distributed among seven different verb classes that can be divided into two groups: physical activities (motion, location of body, possession) and mental activities (speech, mental, existence and perception). Rows containing physical activities are highlighted in light grey.

As can be seen from Table 4, the verbs uznat’ ‘find out’, videt’’see’ and vojti ‘enter’ are never used in the construction možno + nom. On the one hand these constructions might be interpreted by the speakers as idiomatic expressions. For instance, možno vojti ‘may I enter’ in a spoken discourse tends to be reduced to the bare modal word možno with an interrogative intonation and a co-speech gesture like knocking. The construction možno uznat’ ‘I wonder’ is frequently used as a polite formula to pose an uncomfortable question. On the other hand, I would argue that constructions like Možno ja uznaju or Možno ja vojdu are grammatical and can be heard and seen in natural spoken or written discourse.Footnote 8 Therefore, the results in Table 4 might not reflect the holistic picture due to the limited sample size and should be treated with caution.

Overall, the findings discussed in this subsection suggest that both constructions can be used with a variety of verb classes.

4.5 Text creation date and genre

The examples in my dataset are drawn from texts that can be broadly classified into six genres, namely fiction, journalism, forums and blogs, epistolary, liturgy/theology and science fiction. The main body of texts (95%) is distributed between fiction and journalism. The ratio of Nominative constructions to the Dative ones across these two genres is 2:3 the same as in the total dataset. Given that forums and blogs, epistolary, liturgy and science fiction are relatively rare in the database, I therefore collapsed those genres into one category, namely “Other”. Moreover, the statistical analysis in Sect. 5 shows that genre did not play a role whereas text creation date is by far the most important factor.

The dataset contains texts from the 18th to the 21st century. The earliest attestation of možno + dat was registered in the second half of 18th century, the earliest attestation of možno + nom was registered in the first half of 20th century. Figure 2 shows an upward trend for Nominative constructions whereas the Dative constructions remained almost at the same rate during the 20th century and decreased significantly compared to the Nominative ones for the past 15 years.

4.6 Punctuation marks

The Russian language has a strictly regulated system of punctuation rules. Punctuation is used to show the reader how the utterance should be interpreted and where to pause. The speaker must use a comma to separate two different clauses. The možno + dat construction does not require any punctuation marks within it.

In contrast one can suggest that možno behaves as an independent elliptic modal clause when možno is used in the construction možno + nom, therefore možno should be separated from the subject in the Nominative by a comma or another punctuation mark. However, the punctuation marks in my dataset are not consistent. There are 201 (54%) examples in which there is no comma following možno and 169 (46%) examples in which možno is separated from the personal clause by a comma or dash (one sentence). The speakers’ uncertainty regarding punctuation marks indicates that some speakers interpret možno + nom as a single construction (similar to možno + dat).

To sum up, punctuation is a weak factor when it comes to tracking a language change. Punctuation rules are conservative and slow to change. Nevertheless, the absence of a comma in half of the examples in the dataset within the možno + nom suggests that this construction is undergoing a language change in which the modal adverbial is being integrated into the clause.

5 Statistical modelling of factors contributing to the choice of construction

A logistic regression analysis was performed in order to sort out the influence of various factors contributing to the choice of Nominative versus Dative case in construction with možno. First, because the construction možno + cnom is very rare (eleven sentences in the dataset), that data does not support a meaningful statistical distinction of možno + cnom vs. možno + nom. Therefore, that data is aggregated with možno + nom and consequently covert Dative was aggregated with Dative. In a fact this is a distinction between the construction with infinitive where the only way we can insert the argument is the argument in the Dative case as opposed to možno with a finite verb where the only option is the Nominative case.

Second, examples with the verb byt’ ‘be’ were merged with imperfective verbs (according to traditional recognition of this verb as imperfective), therefore aspect (asp) was represented by the opposition imperfective (ipfv) – perfective (pfv). Third, verb classes (verbclass) represented by less than ten verbs, namely emotion, light, phasal, placement (put) and sound, were added to the miscellaneous group. Fourth, in created we removed one data point in 1751 that is all by itself ninety years earlier than any other datapoint. Since that point alone could not give us a reliable measure of the use of možno + nom vs. možno + dat. From 1841 onward we have fairly dense data. The remaining features: transitivity (trans) and possibility of the infinitive or finite form to have an argument in the Dative case (datgov) were not changed. The semantic and syntactic control variables are presented in Table 5.

We started with a statistical model of our maximal hypothesis according to the following formula form ∼ created + asp + datgov + trans + verbclass, meaning that the form is predicted according to the values of created, asp, datgov, trans and verbclass. We then followed a “drop one” procedure to eliminate any non-significant factors. The statistical model showed that predictors asp, trans, datgov and verbclass are not statistically significant. For instance, for perfective verbs 61.4% are used within the dative construction and for imperfective verbs the proportion is almost identical: 59.8%. Similar distributions are observed for datgov and trans. The code that I used is available at TROLLing repository (https://doi.org/10.18710/JXBOQF).

The optimal model is form ∼ created, which yields the following results: for each year the log-odds of getting Subject in the Nominative increases by 0.04, see Table 6.

Then we created a plot of the effect of created for analysis on predicted probability of use of the Nominative construction, see Fig. 3. The probability of use of the možno + nom construction is plotted on the Y-axis, where 0.2 equals 20%, 0.4 equals 40%, 0.6 equals 60%, 0.8 equals 80% and 1 equals 100%, while the creation date is plotted on the X-axis. Data points are projected onto the X-axis and represented as thin lines creating a “rug”. The “Rug” represents the density of data for each year in the time span. The blue line in Fig. 3 shows the prediction, whereas the light blue area is the two-sided 95% confidence interval with upper and lower limits. The confidence interval indicates the most likely range of values associated with the form, i.e., with the probability of using the Nominative construction.

Overall, statistical modeling confirms that we are dealing with a linguistic change, since the only statistically significant factor that influences the choice of construction is the date of creation of the text, and we see a clear upward trend. The shape of the curve is consistent with the s-curve that is associated with language change, see Blythe and Croft (2012).

6 Data from the spoken subcorpus of the RNC

I created a supplementary dataset based on data in the spoken sub-corpus of the RNC in order to determine whether there are pauses that might indicate that možno + nom is not a construction parallel to možno + dat. The corpus consists of 12 113 491 words of transcripts of recorded public and non-public speech of various genres produced by speakers of various ages and backgrounds as well as film transcripts from 1900 through 2016.

I formulated four specific queries with možno + nom and možno + dat, these queries yielded 649 occurrences of možno up to ten words before a question mark. Second, I manually removed all noise from the raw numbers and annotated the remaining sentences (clean data). As a result, I obtained 502 sentences for analysis. The search queries and numbers for clean data are presented in Table 7.

Overall, I removed 147 irrelevant examples that were not requests. The annotation of the clean data was made in accordance with the annotation of the examples in the main dataset.

6.1 Analysis

In this article I will not provide a detailed analysis of the data retrieved from the spoken subcorpus due to space limitations. However, I will provide a summary and highlight the most important findings.

The distribution of requests according to the case of the semantic Subject reflects the distribution of the data in the main dataset: možno is mostly used with the Subject in the Nominative or the Experiencer in the Dative in the first person singular (94%). 467 examples (93%) of dictal predicates were perfectives, followed by a small group of thirty imperfectives that included eighteen examples with periphrastic future forms (budu govorit’ ‘I will talk’). The remaining five examples are used with the verb byt’ ‘be’. 168 predicates are intransitive, whereas 334 verbs are transitive. 195 out of 502 dictal predicates can take an argument in the Dative case.

The dictal predicates were classified into seventeen verb classes, namely creation, existence, change of state, contact, emotion, impact, location, location of body, mental, motion, motion of body, perception, phasal, physiological, possession, speech and miscellaneous. The ten most frequent verbs are given in Table 8. The verbs in rows highlighted in light grey coincide with the most frequent verbs in the main dataset (see Table 4).

The genres are distributed among film and theater transcripts (293 examples) and transcripts of public (154 examples) and non-public (55 examples) discussions. There are not many occurrences of both Dative and Nominative constructions during the first half of the 20th century. However, Fig. 4 shows that from 1950 to 1999 the use of možno + nom is almost 2.5 times more frequent compared to the Dative constructions. At the beginning of the 21st century možno + nom is used 4 times more frequently than the Dative constructions.

Texts in the spoken subcorpus are manually transcribed by native speakers. Usually, the slash mark signals that the speaker paused, or that the annotator expected that the speaker should pause there. Only in 80 (22%) out of 372 examples možno is separated by slash when used in the možno + nom or možno + cnom construction, see (38).

-

(38)

The spoken subcorpus lacks information about the pause length or original recordings, so it is impossible to verify whether the speaker paused or not. In order to get more precise information, I searched for možno + nom and možno + cnom constructions in two corpora of spoken Russian that contain information about pause length, namely “Corpus of Russian Spoken Language” (http://russpeech.spbu.ru) and “Stories about dreams and other corpora of Spoken Language” (http://spokencorpora.ru). I found only three examples with možno + nom, and none of them attested to any pauses that separate the modal word možno and a pronoun, see (39)–(41). The examples are given with a simplified version of annotation for the reader’s convenience.

-

(39)

-

(40)

-

(41)

The absence of a pause demonstrates that in these three examples možno ja is processed by speakers as a single unit parallel to the možno + dat construction. However, due to the small number of examples I cannot extrapolate this assumption to all data.

Overall, the data from the spoken subcorpus confirms that the možno + nom construction is much more frequent than the možno + dat construction in the contemporary Russian language.

7 Speech act requests and politeness strategies

Let us now turn to the pragmatic factors that motivate the choice of the request formula. Requests are face-threatening illocutionary acts. According to Brown and Levinson’s Politeness theory (1978: 311) “‘face’ is the public self-image that every member wants to claim for himself”. “Face” can be both positive and negative. Negative face is “the basic claim to territories, personal preserves, rights to non-distraction – i.e., to freedom of action and freedom from imposition”. Positive face is “the positive consistent self-image or “personality” (crucially including the desire that this self-image be appreciated and approved of) claimed by interactants”.

Requests by their nature are intended to threaten the hearer’s negative face because “the speaker tries to exercise power or direct control over the intentional behavior of the hearer” (Trosborg, 1995: 188). At the same time the speaker loses positive face by imposing her will over the hearer. The speaker may lose a negative face herself, as “the hearer may choose to refuse to comply with her wishes”. Requests for permission to carry out an action are peculiar because as a pre-condition the speaker admits that the hearer has more power and controls the whole situation. Thus, to maintain successful communication it is crucial for the speaker to minimize the risks of losing face not only for the hearer but for herself as well.

One strategy to formulate polite requests is to use conventionally indirect requests. The speaker’s goal is to obtain permission from the hearer, so the speaker is interested in mitigating her request in order to keep the hearer’s face intact. The default way to formulate a conventionally indirect request to carry out an action in Russian is by making a question that begins with the impersonal modal word možno. The other ways of asking permission involve constructions with a personal modal verb moč’ ‘be able’, as in (42); an impersonal modal adverb nel’zja ‘not allowed’ and the particle li ‘whether’ as in (43) and direct questions as in (44).

-

(42)

-

(43)

-

(44)

Such requests are traditionally considered as polite requests as compared with direct requests formulated with an imperative form (45).

-

(45)

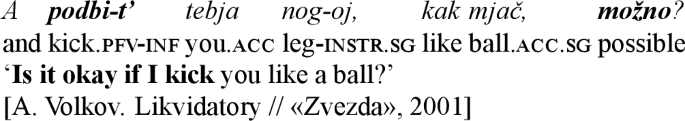

Politeness is a complex phenomenon with many facets to be taken into consideration simultaneously. In everyday communication between family members the imperatives might sound most natural as polite requests, while requests with nel’zja li may sound ironic. However, I suggest that in less familiar context speakers might interpret direct questions as less polite than the requests that begin with modal words. Consequently, speakers will attempt to mitigate the impoliteness of direct questions by adding the modal word možno as a tag-question. However, it is pragmatically unwise to place možno at the final position in a clause, because the hearer could be already upset by the lack of politeness and could refuse to comply with the speakers wishes. Thus, it is advantageous to place možno in the initial position in order to provide the mitigation before the hearer might get annoyed by a request. Thus, by using možno + nom the speaker secures her freedom to act according to her will. On the other hand, the construction with the agentive Subject reduces the hearer’s responsibility for the further development of the situation. However, these claims need to be experimentally tested on a representative group of native speakers.

8 Development of the možno + nom construction

My data demonstrates that the možno + nom construction has become more frequent in contemporary Russian compared to the beginning of the 20th century, while the use of the možno + dat construction has decreased. Language is a system of various forces that motivate the speaker’s linguistic behavior. In the previous sections, I presented various pragmatic (politeness), semantic (the semantic class of the predicate under modality (motion, speech, location etc.) and syntactic (tense, aspect, transitivity, possibility of the infinitive or finite verb to have an argument in the Dative case) factors that provide a conducive environment for the expansion of a new request formula with the Subject in the Nominative case. In this section, I will discuss in detail a possible scenario of the development of the možno+ nom construction and I will hypothesize how the initial construction možno + dat started to be replaced by the construction možno + nom.

The pattern in which the Experiencer in the Dative case is replaced by the Subject in the Nominative case has been discussed in the linguistic literature (Haspelmath, 2001; Seržant, 2013; Grillborzer, 2019). Haspelmath (2001) discusses cases of non-canonical marking of agents in Standard Average European (SAE) languages. Haspelmath (2001) claims that the semantic Subject marked by the Dative case is one of the types of non-canonical marking on experiential predicates (often called “psychological” predicates, e.g., nravit’sja ‘like’). Haspelmath interprets modality predicates of possibility may, can as Experiential predicates as well. Haspelmath (2001: 60) claims that “while Dative Experiencers in modern SAE languages exhibit few (if any) behavioral Subject properties, it might well be that they will acquire some in the future. There is a well-established diachronic tendency for oblique experiencer arguments to acquire behavioral Subject properties, which has been described for various languages by Cole et al. (1980)”. In example (46) taken from Old English the verb licodon ‘like’ requires an Experiencer in the Dative case, whereas in modern English the verb like uses the Subject in the Nominative case.

-

(46)

Þam wife þa word wel licodon.

[the.dat woman.dat those.nom words.nom well liked.3pl]

‘The woman (dat) liked those words (nom) well.’ (Beowulf 639)

If možno directly followed the path proposed by Haspelmath, we would have expected the result to be a modal construction with možno in which the pronoun in the Nominative case precedes the modal word, i.e., pron.nom + možno + verb. This could not be the case for two reasons. First, možno is a modal adverb, so it cannot have a Subject. Syntactically the Experiencer in the Dative case belongs to možno and a semantic subject in the Nominative belongs to the finite verb form (dictal predicate). Second, in Haspelmath’s example the verb like does not have other dependent verb forms, whereas originally možno has an infinitive phrase as a sentential complement.

In natural spoken discourse the pronoun in the Nominative case can be used before možno. There are two examples in the spoken subcorpus of the RNC that reflect the pattern pron.nom + možno + verb, see (47) and (48). Despite the word order, the Subject obviously belongs to the verbs nal’ju ‘I will pour’ and skažu ‘I will tell’.

-

(47)

-

(48)

At the same time the examples provided by Haspelmath are parallel to constructions with možno because the Experiencer in the Dative case and the subject in the Nominative case in the constructions with možno are referring to the same semantic Subject (a requester). The requester has all the semantic properties of a Subject, so potentially it can be marked not by the Dative case, but by Nominative as a canonical Subject. Based on that premise, I suggest that at some stage možno lost the Experiencer and began to be a part of a new construction combined with a personal clause.

Hansen (2010, 2016) examines the lexicalization pattern of the Russian modal verb možet byt’ ‘perhaps’ into an epistemic sentence marker možet ‘perhaps’. Lexicalization is a “change whereby in certain linguistic contexts speakers use a syntactic construction or a word formation as a new contentful form with formal and semantic properties that are not completely derivable or predictable from the constituents of the construction or the word formation pattern. Over time, there may be further loss of internal constituency and the item may become more lexical” (Brinton & Traugott, 2005: 144). Hansen (2010, 2016) claims that modal infinitival možet byt’ construction as in (49) was reanalyzed and, as a result, gave rise to a sentence adverb možet ‘perhaps’ as in (50).Footnote 9

-

(49)

-

(50)

I suggest that možno has undergone a lexicalization process similar to možet, and as a result transitioned from a modal of possibility into a sentence (modal) adverb in the možno + nom construction.

Možno appeared in the language as a modal that could have an Experiencer in the Dative case and an infinitival clause as its complements. At the same time, it could be used as an unconnected and independent možno in requests and permissions, as in (51).

-

(51)

In example (51) Marina is at a dinner where the hostess serves oranges as a special treat for her guests, so Marina requests permission to take an orange by using the modal word možno because she knows that the hearer would understand what she requested. Moreover, the hearer anticipates that the speaker will be tempted by oranges as she says Podoždite, (...) u menja koe-čto est’ ‘Wait a second, I have something here’ and brings plate with oranges into the room. Both the hearer and the speaker have enough knowledge about what the speaker may potentially request, so the speaker can covertly refer to the action which she wants to carry out by uttering just možno with interrogative intonation. Such examples when the action desired by the speaker does not have an overt linguistic expression open up space for activation of both možno + dat and možno + nom constructions. These utterances are typical of spoken language.

For the purposes of this study, I made an additional search in the written part of the RNC for sentences in which možno syntactically behaves as an independent clause or as a tag-question. In other words, I searched for sentences with unconnected možno. I looked for možno after any punctuation mark and before a question mark. This query returned 416 examples. I manually removed noise and annotated the remaining 353 examples, see Table 9. The first occurrences of unconnected use of možno in the RNC date from 1847.

In some situations, the bare modal word možno can be used as a request formula with interrogative intonation as in (52). In such situations speakers often use various extralinguistic means, such as knocking, pointing or nodding to let the hearer know what they want to do. In general, speakers ask whether there are conditions that might stop speakers from carrying out an action.

-

(52)

258 examples in this sample are uses of možno in an independent clause. Even if možno is used as an independent clause, it still can be preceded by a personal or an infinitival clause. In ninety-five examples možno appears as a tag-question as in (53). As a tag-question možno can follow both a clause with a conjugated verb form or an infinitival one as in (53) and (54) respectively. Sixty-seven out of ninety-seven examples have a conjugated verb form in a clause that precedes možno as in (53).

-

(53)

-

(54)

Examples like (53) and (54) have all the elements of a “prototypical” request, namely the modal word možno and an Experiencer in the Dative as in (54) or the Subject in the Nominative case as in (53).

I suggest that we are facing the constructionalization of the možno + nom construction in Contemporary Russian. Traugott (2015: 56) claims that constructionalization occurs when:

“Some hearers (re)analyze the morphosyntactic form of constructs arising at Step c. When there have been morphosyntactic and semantic reanalyses that are shared across speakers and hearers in a social network, a new micro-construction or schema is added to the network, because a new conventional symbolic unit, and hence a new type node, has been created.”

My hypothesis is that examples with unconnected možno served as an intermediate stage in the development of the možno + nom construction. First, speakers used možno as a tag-question for requesting permission. As a tag-question možno does not require the Experiencer in the Dative and syntactically behaves like a sentence adverb. Later speakers analogically began to place možno at the beginning of the sentence as in other requests with modal words. At this stage možno was reanalyzed as a part of a finite clause. As a result, the new možno + nom construction emerged in the language and began to compete with the synonymous možno + dat construction.

9 Conclusions

In this article I discussed the dat-nom variation in a speech act of request in the contemporary Russian language. My contribution can be summarized as follows. First, data from corpora provides evidence that the možno + nom construction is steadily taking the place of the možno + dat construction in both written and spoken discourse.

Second, the analysis of corpus data demonstrates that možno takes the finite clause as its complement and that the use of možno + nom construction is not restricted by syntactic, semantic or pragmatic factors. Third, methods of statistical modelling confirm that the most important factor is the text creation date, while other factors such as aspect, transitivity and semantic verb class of the dictal verb are insignificant. Fourth, I proposed a scenario for the development of the možno + nom construction. Možno began to be used as a tag-question after both infinitive and personal clauses. Steadily the requester marked by the Dative has been replaced by the more agentive Subject in the Nominative case. Then, by analogy with other constructions that are used to ask permission to carry out an action, možno was placed at the beginning of the sentence, and was reanalyzed as constructional unit with the following structure možno + finite clause in which možno functions as a sentence adverb. As a result, in contemporary Russian možno + nom functions as a default construction to formulate a request for permission to carry out an action.

Language change is a gradual process, and variation is an integral part of that process. We may expect that in the future the možno + dat construction will disappear from the Russian language, however it is also possible that možno + dat may never cease to be used, and remain a low-frequent alternative to the request formula možno + nom.

Data Availability

Data will be available at TROLLing repository (https://dataverse.no/dataverse/trolling).

Code Availability

Code will be available at TROLLing repository (https://dataverse.no/dataverse/trolling).

Notes

We use term modal in the same way as Besters-Dilger et al. (2009: 169) “modals as means of expression of modality, which have undergone a grammaticalization process; they express the basic notions of ‘necessity’ and ‘possibility’ and show syntactic properties of auxiliaries.”

In this formula “v.fin” stands for any finite verb form that agrees with the Subject in number, person and/or gender as opposed to the infinitive. “dat” and “nom” stand for any noun or pronoun in the Dative or in Nominative case respectively. This convention is used throughout the article.

This decision might contradict the surface-oriented principles of Usage-based Construction Grammar, i.e., “no underlying levels of syntax or any phonologically empty elements are posited” (see Goldberg, 2003: 219). However, in examples like (7) the requester usually coincides with the speaker (mne ‘for me’) or includes the speaker as a member of a larger group (nam ‘for us’). Thus, pragmatically it would be incorrect to call such constructions underspecified, because even if the requester is not overtly marked, the hearer is able to unequivocally identify the requester.

However, Choi (1994) does not present clear evidence why the use of moč’ is atypical in the speech act of request.

Although particles such as razve ‘really’ or neuželi ‘really’ that function as epistemic or evidential markers are not included in the analysis proposed in Endresen et al. (2016), the authors provide convincing evidence in favor of Zwicky’s claim that the label ‘particle’ should be removed from the inventory of parts of speech. In this article, we are following the direction set by Endresen et al. (2016) on further reclassification of particles by analyzing properties of možno when it is used in requests. Further examination of the behavior of razve, neuželi and možno is beyond the scope of this paper.

In this article, I use the same semantic tags as assigned in the RNC. The verbs that have not been assigned a semantic tag in the RNC were manually classified by an external linguist. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Galina Kustova, who generously agreed to class the remaining verbs in my dataset.

Example (14) repeated here as (21) with an extended context for readers’ convenience.

Examples with možno (ja) uznaju or možno mne uznat’ can be found in the GICR corpus (Belikov et al. (2013), http://www.webcorpora.ru/), e.g.: Možno ja uznaju? – umoljajušče stala prositʹ ja prepodavatelja ‘Is it okay if I check on him? – I began to plead the professor’; A možno mne uznatʹ pro rabotu? ‘Is it okay if I ask about a job?’.

Examples are cited from Hansen (2016: 273–274); comp stands for complementizer, whereas cond stands for conditional.

References

Belikov, V., Kopylov, N., Piperski, A., Selegey, V., & Sharoff, S. (2013). Corpus as language: from scalability to register variation. In Dialogue, Russian international conference on computational linguistics, Bekasovo.

Beljaeva, E. I. (1990). Vozmožnost’. In A. V. Bondarko (Ed.), Teorija funkcional’noj grammatiki. Temporal’nost’. Modal’nost’ (pp. 126–142). Leningrad: Nauka.

Besters-Dilger, J. (1997). Modal’nost’ v pol’skom i russkom jazykax. Istoričeskoe razvitie vyraženija neobxodimosti i vozmožnosti kak rezul’tat vne-mežslavjanskogo vlijanija. Wiener Slavistisches Jahrbuch, 43, 17–31.

Besters-Dilger, J., Drobnjaković, A., & Hansen, B. (2009). Modals in the Slavonic languages. In B. Hansen & F. Haan (Eds.), Modals in the languages of Europe: a reference work (pp. 167–198). Berlin, New York: de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110219210.2.167.

Blythe, R. A., & Croft, W. (2012). S-curves and the mechanisms of propagation in language change. Language, 88(2), 269–304. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2012.0027.

Brinton, L. J., & Traugott, E. C. (2005). Lexicalization and language change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1978). Universals in language usage: politeness phenomena. In E. Goody (Ed.), Questions and politeness: Strategies in social interaction (pp. 56–311). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Choi, S.-H. (1994). Modal predicates in Russian: semantics and syntax [Doctoral dissertation, UCLA].

Cole, P., Harbert, W., Hermon, G., & Sridhar, S. N. (1980). The acquisition of subjecthood. Language, 56(4), 719–743.

Dubinina, I. Y., & Malamud, S. A. (2017). Emergent communicative norms in a contact language: indirect requests in heritage Russian. Linguistics, 55(1), 67–116. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling-2016-0039.

Endresen, A., Janda, L. A., Reynolds, R., & Tyers, F. M. (2016). Who needs particles? A challenge to the classification of particles as a part of speech in Russian. Russian Linguistics, 40(2), 103–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-016-9160-2.

Goldberg, A. (2003). Constructions: a new theoretical approach to language. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(5), 219–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(03)00080-9.

Goldberg, A. (2006). Constructions at work: the nature of generalization in language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Grillborzer, C. (2019). Sintaksis konstrukcij s pervym dativnym aktantom. Sinxronnyj i diaxronnyj analiz. Berlin: Peter Lang. Retrieved May 15, 2022, from https://www.peterlang.com/document/1110877.

Hansen, B. (2001). Das slavische Modalauxiliar: Semantik und Grammatikalisierung im Russischen, Polnischen, Serbischen/Kroatischen und Altkirchenslavischen. München: O. Sagner.

Hansen, B. (2010). Constructional aspects of the rise of epistemic sentence adverbs in Russian. Wiener Slawistischer Almanach, 74, 75–86.

Hansen, B. (2016). What happens after grammaticalization? Post-grammaticalization processes in the area of modality. In D. Olmen, H. Cuyckens, & L. Ghesquière (Eds.), Aspects of grammaticalization: (inter) subjectification and directionality (pp. 257–280). Berlin, Boston: de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110492347-010.

Haspelmath, M. (2001). Non-canonical marking of core arguments in European languages. Typological Studies in Language, 46, 53–84. https://doi.org/10.1075/tsl.46.04has.

Kochman, S. (1975). Polsko-rosyjskie stosunki językowe od XVI do XVIII wieku. Opole: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Opolskiego.

Kopečný, F., & Havlová, E. (1981). Základní všeslovanská slovní zásoba. Praha: Academia.

Lyashevskaya, O., Ovsjannikova, M., Szymor, N., & Divjak, D. (2017). Looking for contextual cues to differentiating modal meanings. A corpus-based study. In M. Kopotev, O. Lyashevskaya & A. Mustajoki (Eds.), Quantitative Approaches to the Russian Language (pp. 51–78). Abingdon: Routledge.

Padučeva, E. (2016). Modal’nost’. Materialy dlja proekta korpusnogo opisanija russkoj grammatiki. Retrieved April, 12, 2021 from http://rusgram.ru.

Ramat, P., & Ricca, D. (2011). Sentence adverbs in the languages of Europe. In J. Auwera (Ed.), Adverbial constructions in the languages of Europe (pp. 187–276). Berlin, New York: de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110802610.187.

Seržant, I. A. (2013). The diachronic typology of non-canonical subjects. In I. A. Seržant & L. Kulikov (Eds.), The diachrony of non-canonical subjects. SLCS 140 (pp. 313–360). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/slcs.140.

Šanskij, N. M., Ivanov, V. V., & Šanskaja, T. V. (1961). Kratkij ètimologičeskij slovar’ russkogo jazyka. Moskva: Prosveščenie.

Švedova, N., Arutjunova, N., Bondarko, A., Ivanov, V., Lopatin, V., Uluxanov, I., & Filin, F. (Eds.) (1980). Russkaja grammatika (Vol. 1). Moscow: Nauka.

Timberlake, A. (2004). A reference grammar of Russian. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Traugott, E. C. (2015). Toward a coherent account of grammatical constructionalization. In J. Barðdal, E. Smirnova, L. Sommerer, & G. Spike (Eds.), Diachronic Construction Grammar (pp. 51–80). Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/cal.18.02tra.

Trosborg, A. (1995). Interlanguage pragmatics: requests, complaints and apologies. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Van der Auwera, J., & Plungian, V. A. (1998). Modality’s semantic map. Linguistic Typology, 2(1), 79–124. https://doi.org/10.1515/lity.1998.2.1.79.

Vaulina, S. S. (1988). Èvoljucija sredstv vyraženija modal’nosti v russkom jazyke (XI–XVII vv.). Leningrad: Izdatelʹstvo Leningradskogo universiteta.

Zwicky, A. M. (1985). Clitics and particles. Language, 61(2), 283–305. https://doi.org/10.2307/414146.

Corpora

Corpus of Russian Spoken Language. http://russpeech.spbu.ru.

RNC – Russian National Corpus. http://www.ruscorpora.ru.

Stories about dreams and other corpora of Spoken Language. http://spokencorpora.ru.

Funding

Open access funding provided by UiT The Arctic University of Norway (incl University Hospital of North Norway). Financial support was received from the PhD programme from the Arctic University of Norway.

This work was partially supported by TWIRLL: Targeting Wordforms in Russian Language Learning (CPRU-2017/10027).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest/Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhamaletdinova, E. The trajectory of the “Možno ja X?” construction: variation in speech acts of request in contemporary Russian. Russ Linguist 46, 133–164 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-022-09265-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-022-09265-6