Abstract

The Nakh-Daghestanian language Tabasaran displays indexical shift in the reported speech construction. Having many properties in common with indexical shift attested in other languages, the shift of embedded pronouns in Tabasaran depends strongly on the presence of person clitics on the embedded verb in the reported speech. Pronouns doubled by clitics receive a shifted interpretation, while independent personal pronouns have an indexical interpretation. This behavior of clitics contrasts with their behavior in an affirmative root clause, where they obligatorily double any first or second person subject. The investigation of interrogative sentences draws a link between two different strategies in the behavior of person clitics in the reported speech construction and in the affirmative root clause. I propose that personal pronouns and clitics are separate DPs, specified for different features: pronouns are indexicals, while clitics specified for person features also have the Logophoric feature and therefore indicate the logophoric Speaker and Addressee. In reported speech, when bound by a clitic, personal pronouns receive a shifted interpretation and also refer to logophoric participants that are matrix arguments in the reported speech. The paper also discusses the binding relationship between clitics and personal pronouns in those cases where they do not match in their phi-features and proposes that the binding is based not on the interaction between their morphological phi-features but rather on their referential content, which is generated by the whole feature set of each item.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Tabasaran is an ergative language of the Lezgic branch within the Nakh-Daghestanian family (the Republic of Daghestan, Russia). This paper discusses indexical shift in the reported speech construction in the Džuli dialect of the language.Footnote 1

Typologically, personal pronouns exhibit universal indexical behavior and uniformly refer to discourse participants. However, several unrelated languages display a phenomenon of indexical shift in reported speech sentences, where I and you refer to somebody other than the current speaker or the current addressee. Schlenker (1999, 2003) discusses what is now a very well-known example from Amharic (Ethiopian-Semitic), literally: ‘Johni says that Ii/j am a hero’ where ‘I’ can indicate not only the current speaker who restates what John said, but alternatively refer to ‘John,’ the third person argument that is semantically the original speaker.

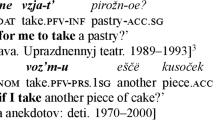

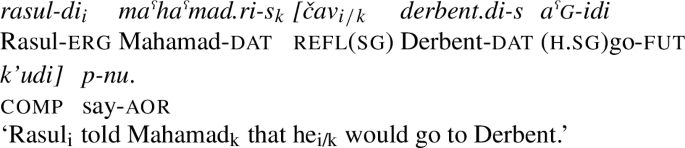

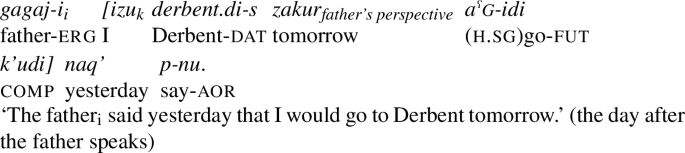

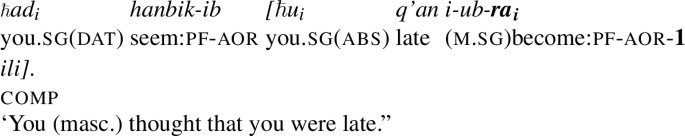

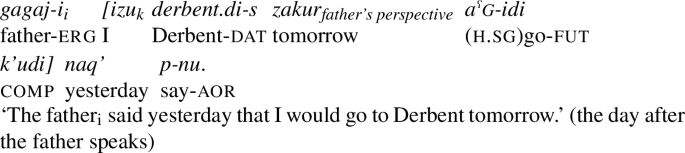

Tabasaran shares several characteristics of indexical shift with other languages that display this phenomenon. First, in Tabasaran, indexical shift occurs in the same syntactic environment as in other languages. The reported speech construction in Tabasaran is a complex clause. When they appear in the embedded clause under the attitude predicate, the interpretation of personal pronouns can change, in a way similar to Amharic. Second, as has been shown for other languages with indexical shift, the change in the interpretation of a personal pronoun is not a result of quoted speech, and the embedded clause cannot be treated as a direct quotation. In Tabasaran, in reported speech, the subordinate clause is obligatorily introduced by the special complementizer k’udi,Footnote 2 and other facts concerning the behavior of person clitics in reported speech that differ extremely from a root clause cannot support a quotation analysis either (Sect. 4). The third common property that Tabasaran shares with other languages is that indexical shift occurs within the embedded finite clause and does not occur in non-finite clauses. Examples (1a–1b) demonstrate the contrast. In (1a) the complementizer k’udi (glossed as comp) introduces the embedded finite clause. The first person pronoun izu ‘I’ within the embedded clause shifts and refers to the reported speaker gagaj ‘father’ (the coreferential arguments izu ‘I’ and gagaji ‘father’ are marked by the same index i). The unshifted interpretation, where izu ‘I’ refers to the current speaker, is impossible here. By contrast, in (1b) in the complex sentence the same complementizer k’udi introduces a non-finite purpose clause, the first person pronoun izu ‘I’ has only the unshifted interpretation, referring to the current speaker.

-

(1)

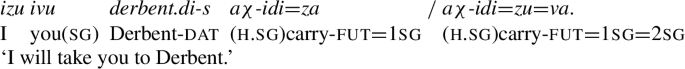

What makes Tabasaran interesting compared to other languages is that in indexical shift not only personal pronouns are involved but person clitics as well. Example (1a) shows that if the first person pronoun izu is doubled by the 1.sg clitic =za on the embedded verb a ‹CL›G- ‘go,’ the pronoun izu ‘I’ has a shifted interpretation. By contrast, example (2) demonstrates that if the embedded verb does not bear the clitic, the pronoun izu ‘I’ can only be interpreted indexically, unshifted; that is, it may only refer to the current speaker.

‹CL›G- ‘go,’ the pronoun izu ‘I’ has a shifted interpretation. By contrast, example (2) demonstrates that if the embedded verb does not bear the clitic, the pronoun izu ‘I’ can only be interpreted indexically, unshifted; that is, it may only refer to the current speaker.

-

(2)

Although indexical shift in the reported speech construction is discussed at great length in the current literature, the contribution of verbal inflections to indexical shift has only recently received theoretical attention. In this article, I document indexical shift in Tabasaran and show what contribution these data make to modern theories of indexical shift proposed for other languages.

The article is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, I give a short overview of two main approaches to indexical shift: the analysis with monster operators, and the binding-based analysis. I also take a closer look at languages that demonstrate shifting not only with personal pronouns but also with verbal inflections and discuss the phenomenon of feature mismatches between pronouns and verbal markers in the embedded report. In Sects. 3 through 9, I present indexical shift in Džuli and propose an analysis based on binding. Section 10 concludes.

2 Modern theories of indexical shift

Currently, at least two types of approaches to non-indexical behavior of personal pronouns in reported speech can be identified: those that employ context shift operators, and those that use the binding mechanism (see Deal 2019: 21–31 for a more complete overview of other sorts of approaches). The latter family of research has recently split in two directions. Typically, binding-based approaches assume that the indexical shift of pronouns is a result of a dependency relationship between embedded pronouns and an attitude verb or, more commonly, between the pronoun and a silent element, introduced by the attitude verb. By contrast, Alok and Baker (2018) and Alok (2020) propose that such kinds of elements can exist in the periphery of any finite clause and that indexical shift is a special case of how they can manifest themselves. This section briefly discusses key points in the development of the theory concerning indexical shift in order to show which components of the theory can be applied to the analysis of Tabasaran data.

2.1 Monsters and shifty operators

As is well known, the indexical theory of personal pronouns was initiated by Kaplan (1989), who claimed that personal pronouns like I and you are indexicals, whose semantics are fixed, since they directly refer to the speaker of the current speech act or his/her addressee. Kaplan’s main conclusion is that there are no context-shifting operators that can change the interpretation of indexicals. He calls this kind of operator a “monster” and rejects its existence in his theory.

However, Schlenker (1999, 2003) resurrects the metaphor of the monster and, in contrast to Kaplan’s theoretical claim, shows that pronouns can shift their interpretation, at least in the reported speech construction, as discussed for Amharic (see Sect. 1). Schlenker claims that the shifting operator does exist and can manipulate indexicals. He proposes that in Amharic these are attitude verbs that behave like Kaplan’s monsters. Personal pronouns in Amharic are treated as all-purpose indexicals that can get their interpretation either from a matrix or embedded context. He accounts for indexical shift in terms of binding. Indexicals consist of the free context variables ‹author, time, and world› and may spell out as variables that are bound either by the coordinates of the matrix or the coordinates of the embedded context.

The idea of the existence of a monster responsible for indexical shift is developed by Anand and Nevins (2004), who analyze data from Zazaki (Iranian) and Slave (Athabaskan). These two languages demonstrate a phenomenon that the authors call “shift-together,” where in the embedded clause under attitude verbs all indexicals simultaneously shift and all receive their reference from the same context. Example (3) from Zazaki shows that not only does the pronoun ‘I’ shift and refer to the reported speaker, but the adverbs ‘now’ and ‘here’ also have a shifted interpretation and refer to the situation described, in the embedded clause of the reported speech, rather than to the current speech act. The authors propose introducing a syntactically separate operator that overwrites all context parameters.

Zazaki (Anand and Nevins 2004: 23)

-

(3)

For a selective indexical shift attested in Slave, where under the verbs ‘say’ and ‘want’ only a first person pronoun can shift, the authors enrich the operator with an index parameter such as Author (OPauthor), which is determined by the lexical entry of the matrix verb.

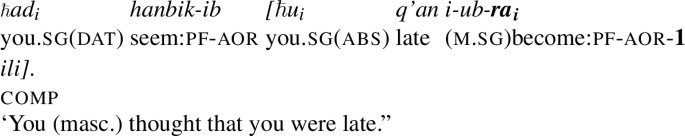

After Anand and Nevins (2004), Shklovsky and Sudo (2014), discussing indexical shift in Uyghur (Turkic), not only introduce a monster operator into their analysis of Uyghur but also show that the monster has a certain syntactic position in the clause structure. In Uyghur, indexical shift depends on whether the embedded pronoun is marked by accusative or nominative case. A nominative first person or second person subject obligatorily shifts in embedded clauses, as in (4a), while the subject pronoun in accusative case requires an unshifted interpretation, as in (4b) (see Sect. 2.3 concerning verbal morphology in these examples):

Uyghur (Shklovsky and Sudo 2014: 386)

-

(4)

The authors conclude that the monster divides the embedded clause into two domains: the shifted domain, the part of the clause that is under the monster; and the unshifted domain, the part of clause that is above of the monster. The accusative embedded subject is always structurally higher than the monster operator, so it does not shift. By contrast, the nominative embedded subject is lower and falls within the scope of the monster operator, with the consequence that it always has a shifted interpretation. One of the confirmations that the monster occupies a certain position in the clause structure in Uyghur is a fact strongly reminiscent of “shift-together,” discussed by Anand and Nevins (2004): in Uyghur, none of the indexicals within the accusative subject may shift, since they are not in the scope of the monster, while all indexicals within the nominative subject must shift since they do fall under the scope of the monster.

Considering a sufficiently large sample of languages with indexical shift, Deal (2017, 2019) develops the theory of shifty operators and shows that different attitude verbs introduce complements of different sizes, which affects the degree of indexical shift. Shifty operators sit in a rigid sequence in the clause periphery and vary in how many parameters of context they modify.

2.2 Operator binding theory

The alternative to shifty operator approaches is binding-based theory. Koopman and Sportiche (1989) are the first to propose a binding analysis to explain the logophoric behavior of pronouns in embedded clauses in reported speech in Abe (Kwa branch of the Niger-Congo family). The essence of the analysis is that there is a silent DP element (log operator), which acts as a mediator between the matrix subject and the corresponding embedded pronoun. The log operator specifies the CP in its scope as its logophoric domain and binds the embedded pronoun there, so that the latter refers to the matrix subject (see also Sect. 6).

Explaining the behavior of the long-distance anaphor in two dialects of Mandarin, Anand (2006) proposes that both mechanisms—the overwriting context parameters and the local binding between a silent element and an anaphor—can be operative in the syntax.

Based on Anand (2006), Deal (2017, 2018, 2019) proposes distinguishing between two different phenomena: true shifted indexicals, which change their interpretation depending on the context operator in whose scope they fall (Sect. 2.1) and what she calls indexiphoricity, parallel to logophoricity, which is a result of a binding relationship (see Sect. 2.3).

2.2.1 Reductive binding analysis: Alok and Baker (2018)

Recently, Alok and Baker (2018) have proposed a reductive binding analysis for the indexical shift found in Magahi (Eastern Indo-Aryan). Their main idea is that the non-indexical behavior of pronouns in reported speech is a manifestation of binding relationship between personal pronouns and silent elements in the periphery of root clauses.

In Magahi, in the embedded report, a personal pronoun can refer to either the current speaker or his/her addressee, constituting a non-shifted reading, or refer to matrix arguments, resulting in a shifted interpretation, shown in (5).

Magahi (Alok and Baker 2018)

-

(5)

What is interesting is that in Magahi not only personal pronouns but also allocutive markers can shift. Beyond the reported speech construction, allocutive markers (agreement) can optionally be used in a root clause and express the honorific status of the addressee from the speaker’s point of view in three degrees: non-honorific (speaker’s peer), honorific, and high honorific.

In reported speech, allocutive markers can be optionally used in an embedded clause and indicate the status of the addressee from the current speaker’s perspective (unshifted) or the status of the addressee from the reported speaker’s point of view (shifted) in the same three degrees (non-honorific, honorific, high honorific). What is crucial here is that if the allocutive marker on the embedded verb refers to the addressee of the reported speaker—that is, has a shifted interpretation—then any personal pronouns in the embedded clause are also subject to obligatory shift.

At the heart of Alok and Baker’s (2018) analysis is the theory of agreement in the finite clause developed by Baker (2008). In Baker’s theory, agreement of first and second person differs in nature from agreement in other features and is a sort of operator–variable agreement.Footnote 3 He introduces special empty categories at the CP level, null arguments that designate the speaker (Sp) and addressee (Ad) of the sentence, which bind the first and second person pronouns, acting as operators. Baker proposes that personal pronouns receive their person features over the course of their derivation (an idea akin to Krazter’s 2009 minimal pronoun approach). To be rendered fully fledged by person features, personal pronouns must participate in binding relationships with higher elements Sp and Ad that supply the whole package of person features to the bound personal pronoun.

For this reason, the allocutive markers in Magahi are treated as DPs that manifest the existence of Ad in the periphery of any finite clause. Being DPs, they bear all features that other DPs have in Magahi and are able to bind other referentially dependent DPs in their domain. Since allocutive makers bear features associated with the person that the sentence is addressed to, they bind second person pronouns in their domain. Although there are not any first person markers that would allow one to ascertain the covert Sp(eaker) in Magahi, Alok and Baker assume that there is another DP in the periphery of the clause that identifies the covert Speaker. In the same way that Ad binds the second person pronoun in its domain, Sp binds the first person pronoun.

Since in the reported speech construction the embedded clause is also finite, it also has Sp and Ad in its periphery. Whether an embedded pronoun has a shifted or unshifted interpretation depends on what its binder is. If the first pronoun is bound by the covert Sp of the embedded clause, the Sp is controlled by the subject of the main clause (the reported speaker) resulting in the embedded first person pronoun having a shifted interpretation, as presented schematically in (6):

-

(6)

Otherwise, the first person pronoun is bound by the Sp element of the main clause and so refers to the current speaker.

In the same way, if the second person pronoun in the embedded clause of the reported speech is bound by the Ad element of the embedded clause, the latter is controlled by the matrix goal argument (the addressee of the reported speaker), which yields the shifted interpretation of the second person pronoun, shown in (7):

-

(7)

By contrast, if the embedded second person pronoun is controlled by the highest Ad (of the main clause), there is no shifting and the pronoun refers to the addressee of the current speaker.

Alok and Baker’s (2018) analysis in terms of binding makes several strong predictions. First, since pronouns receive their features by being bound by Sp and Ad, the features on the pronoun and the features of the corresponding verbal marker must be the same, because of their strict syntactic feature sharing (based on Baker’s 2008 theory). Any mismatch in features between them is impossible. A mismatch is only valid if pronouns and allocutive markers have the ability to refer to the addressee independently, but this is not the case. Second, since Ad is controlled by the goal argument of the matrix clause, the covert DP has the same features as the goal of the matrix clause. Alok and Baker compare the Ad element with PRO in sentences like Mary told John [PRO to buy milk] and consider the Ad to be a kind of null pronominal at the edge of a particular type of clause. Third, the analysis also predicts that the argument controlling Sp is a syntactic subject nearest to Sp and that a mismatch between the grammatical subject and the semantic notion of speaker (author) of the propositional content is also impossible (for the diagnostic contexts, see Sect. 9).

Although the control analysis itself does not predict the “shift-together” phenomenon, Alok and Baker assume that “shift-together” is the result of the simultaneous control of Ad and Sp by arguments from the same syntactic level. Ad of the embedded clause is controlled by the matrix goal if and only if Sp in the embedded clause is controlled by the matrix subject.Footnote 4

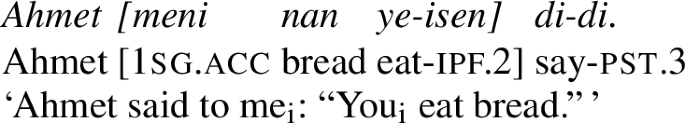

Baker (2008: 149–155) applies his analysis to the data from Amharic, Zazaki, and Slave (Schlenker 1999, 2003; Anand and Nevins 2004; see Sect. 2.1) and shows that it can successfully explain the indexical shift in these languages.

The theory of indexical shift receives a new twist in its development by drawing on new facts from languages in which pronouns and verbal inflections in embedded clauses demonstrate mismatches in their features.

2.3 Feature mismatches in the embedded report

Different approaches propose different explanations for feature mismatches between pronouns and verbal exponents in embedded reports.

Within the shifty operator-based account, Shklovsky and Sudo (2014) explain such mismatches in Uyghur based on a geometrical representation of clause domain. As shown in (4a), the nominative first person subject obligatorily triggers first person agreement. However, in (4b), the accusative first person subject does not have the corresponding agreement, and the embedded verb has the third person inflection, thus displaying a mismatch in features with the subject. The authors assume that in (4b), the accusative subject is not a proleptic argument of the embedded verb and therefore does not shift; however, the third person verbal agreement, being under the scope of the shifting operator, does shift, resulting in a third person interpretation.

In Uyghur, feature mismatches between embedded arguments and verbal agreement are also possible when both refer to matrix arguments. Example (8) shows that an accusative first person subject triggers second person agreement. Despite this mismatch, the two elements have the same interpretation, referring to the addressee of the reported speaker.Footnote 5

Uyghur (Shklovsky and Sudo 2014: 399)

-

(8)

Although the structural analysis proposed by Shklovsky and Sudo (2014) is able to explain the appearance of mismatches between subjects and agreement markers when they refer to the current participants, as in (4b), it seems unable to fully explain the situation in (8), where the accusative first person subject refers to the addressee of the reported speaker, receiving the same interpretation as the second person verbal agreement. The mechanism by which the referential identity between the pronoun and the verbal inflection is established is not clear from the structural analysis.

One of the first binding analyses for mismatches between pronominals and verbal markers in the embedded report was proposed for Tamil (Dravidian) by Sundaresan (2012). In that language, in indirect speech, the embedded subject that refers to the reported speaker is expressed by the third person anaphor ta(a)n. The embedded verb can have either third person or first person agreement. In the latter case, the logophoric pronoun and the first person inflection referring together to the reported speaker do not specify for the same person features, as shown in (9).

Tamil (Sundaresan 2012: 54–55)

-

(9)

Sundaresan (2012) first examines the third person agreement on the embedded verb and shows that agreement reflects the person–gender–number features of the matrix subject, the antecedent of ta(a)n. Referring to Kratzer (2009), she assumes that the anaphor ta(a)n itself has either defective features or no phi-features at all. Therefore, it is not the anaphor that triggers verbal agreement, but rather the verbal marker has another source. She introduces a null pronominal operator, a DP whose presence depends on the selection properties of a superordinate attitude predicate. The relationship between the matrix subject and the pronominal operator (DP) is predominantly conceptual and instantiates a type of non-obligatory control. The anaphor ta(a)n and the operator are characterized as having a Dep(endent) feature. The pronominal operator binds the anaphor, and two elements converge in their reference. In the case of first person agreement, the pronominal operator is shifted. It is interpreted as first person with respect to the context introduced by the speech predicate. Since taa(n) is feature-defective, the probe on T upwardly agrees with the null element, resulting in the first person agreement. Binding relationships between the silent DP, the anaphor, and the agreement with the silent DP ensure that taa(n) and the first person verbal inflection denote the same entity.

Messick (2023) revises Sundaresan’s (2012) analysis of monstrous agreement in Tamil. He examines a similar agreement pattern in reported speech in Telugu (Dravidian), where just as in Tamil, in the embedded report the third person pronoun co-occurs with first person agreement on the verb. In contrast to Sundaresan’s (2012, 2018) analysis, Messick proposes that it is the third person anaphor itself which controls the first person agreement. Based on Schlenker (2003), he assumes that an embedded pronoun, referring to an attitude holder, has complex features. It is simultaneously first person, bearing the features [+Author; −C(urrent speech)], and third person, specified for the features [−Author; +C(urrent speech)]. In contrast to the embedded pronoun, the agreement morphology is unspecified for [±C]. Therefore, the feature bundled with [+C]—that is, [−Author]—is deleted and the first person agreement morpheme is inserted.Footnote 6

Based on Culy (1994) and Coppock and Wechsler (2018), Deal (2019) examines reported speech in Donno Sɔ (Dogon) and Kathmandu Newari (Tibeto-Burman) and shows that in these languages, in simple declarative clauses a first person subject triggers first person agreement. However, in reported speech the same verbal inflection appears with an anaphoric pronoun and cannot appear with an embedded first person pronoun, unlike in a root declarative clause. Deal (2017, 2018) proposes that the logophoric operator in Donno Sɔ has the special property of licensing first person agreement and calls the effect agreement reprogramming. In Deal (2019), she proposes that a subject can bear a meaningful feature author, which manifests itself on the verb as first person agreement. In matrix declarative clauses, since the subject has this feature, the verb obligatorily bears first person agreement. In the embedded reported speech, embedded anaphoric pronouns have the feature author, resulting in the appearance of index-sensitive verbal inflection. Thus, despite the morphologically different feature specification, the two elements coincide in the feature author.

Recently, Ganenkov (to appear) has proposed a binding-based analysis for reported speech in Aqusha Dargwa (Nakh-Daghestanian). As in other languages cited above, in Aqusha, embedded personal pronouns and corresponding verbal agreement can shift in reported speech. Additionally, Aqusha demonstrates the mismatch discussed above, where the third person anaphor can trigger first person agreement. Finally, in Aqusha, a second person embedded pronoun can co-occur with the first person verbal marker, as shown in (10).

Aqusha Dargwa (Ganenkov, to appear)

-

(10)

Two types of agreement are distinguished in the analysis: the type that is sensitive to person features of arguments, and the type that is sensitive to logophoric features. The latter is involved in indexical shift in reported speech: only pronouns that denote the participants of the matrix clause trigger logophoric agreement. The complementizer ili acts as a log operator that represents the context of the speech event. It binds personal pronouns defining their context of interpretation (with reference to Schlenker 2003) and supplying them the feature [Log] via binding. In this case, the pronouns obligatorily trigger first or second person agreement correspondingly and both elements refer to matrix arguments.

An embedded report that contains mismatches is derived differently. In an example like (10), the second person pronoun does not shift, since it refers to the addressee of the current speaker. However, the verb bears first person agreement. In this case, the logophoric complementizer does not participate, since the embedded pronoun is indexical rather than shifted. The next assumption is that the complementizer introduces a null argument specified for the feature [attitude holder], which binds the second person pronoun so that the latter receives the [attitude holder] feature and therefore triggers first person agreement, however, superficially, it looks like a feature mismatch between two elements.

In sum, in the current theory of indexical shift, two types of analysis coexist: approaches with shifty operators and binding-based approaches. The latter are presented in at least two versions depending on where the logophoric operator is introduced. The more common assumption is that the log operator is initiated by the syntax of the reported speech construction and introduced by attitude verbs (Sundaresan 2012, 2018; Deal 2019; Messick 2023; Ganenkov to appear) or an attitude verb itself binds personal pronouns (Schlenker 1999, 2003; Ganenkov to appear). By contrast, Alok and Baker (2018) and Alok (2020) propose that operators responsible for indexical shift in reported speech exist in any root finite clause. Additionally, binding approaches greatly differ in how they treat relationships between a silent log operator, embedded pronouns, and verbal inflections. In Sundaresan (2012, 2018), T agrees with the log operator, yielding the mismatch between phi-features of the embedded anaphor and verbal agreement. Roughly, in Deal (2019), Messick (2023), and Ganenkov (to appear), embedded pronouns, independently of their morphological features, receive an additional feature such as [author] or [attitude holder] and therefore trigger first person inflection on the verb, resulting in their feature mismatches. Alok and Baker’s (2018) and Alok’s (2020) binding theory does not predict any mismatches between pronouns and verbal exponents; they must coincide in their features.

The rest of this paper documents the reported speech construction in Tabasaran.Footnote 7 For indexical shift there, I propose a binding-based analysis, going back to original idea of Alok and Baker (2018) but with a revision of their theory. Section 3 describes the main properties of Tabasaran clitics in root clauses. I lay out my main assumptions about the structure of simple clauses and the position of clitic in them. I outline the main characteristics of Tabasaran clitics, which are not explained by the existing approaches, and present my core proposal that clitics and pronouns are separate DPs, which differ in their features. The facts concerning reported speech bring their properties to light, and the rest of the discussion provides arguments for my claim. In Sect. 4 I focus on reported speech sentences and show that indexical shift in reported speech depends on the presence of clitics. The absence of “shift-together” and blocking effects in Džuli make both an analysis with a context operator and a binding-based analysis with a binder operator inappropriate for Tabasaran. Instead of this, I propose that in Tabasaran clitics trigger the shift of personal pronouns entering in the binding relationship with them. Section 5 demonstrates the behavior of pronouns and clitics in interrogative sentences and shows that the same binding mechanism is present in any root clause, which generally confirms the intuition of Baker (2008), Alok and Baker (2018), and Alok (2020). However, in contrast to their approach, I show that both pronouns and clitics have independent referential ability. Pronouns specified for person features are real indexicals. Clitics specified for person features independently of pronouns additionally have the Log(ophoric) feature and therefore refer only to logophoric participants. Bound by the corresponding clitics, pronouns also receive the Log feature via binding. Section 6 takes a closer look at personal pronouns and logophoricity and integrates the Tabasaran data into the theoretical discussion. Nominalizations give another piece of evidence that personal pronouns in Tabasaran are not minimal and that they have their own referential content. Section 7 shows this mechanism of binding for reported speech sentences in more detail. Section 8 demonstrates possible feature mismatches between personal pronouns, the reflexive, and clitics in Džuli and discusses that binding relationships are based not on the morphological phi-feature interaction between the items but rather on the interaction of their referential content generated by the features. Clitics are sensitive to items with the referential content [Logophoric Participant] and [Person Participant]. Finally, Sect. 9 discusses the relationship between matrix arguments and clitics.

3 Clitics in affirmative clauses

This section describes the behavior of clitics in a root affirmative sentence in order to subsequently show the difference in their behavior in indirect speech.

3.1 The structural position of clitics

First of all, I will briefly sketch the structure of a simple clause in Tabasaran and the clitic position there. I mostly depend on the analysis of the transitive clause, presented in Bogomolova (2022), based on the data from another Tabasaran dialect, Mežgül.

For a number of Daghestanian languages it has already been shown that they are extremely different from nominative–accusative languages, where the subject case assignment is associated with TP. Tsez, Archi, and Lak (all Daghestanian) demonstrate that case licensing occurs at an earlier stage of clause derivation (Polinsky and Potsdam 2001; Polinsky 2003, 2015, 2016; Gagliardi et al. 2014; Polinsky et al. 2017). The same has been recently shown for one of Dargwa languages, namely Chirag (Ganenkov 2021). This generalization is based on the behavior of nominalizations in these languages, clauses of a smaller size, lacking aspect, tense, and mood projections, which, despite their little content, display the same ergative–absolutive case marking as in a finite transitive clause. Mežgül Tabasaran is no exception here. In Mežgül, a nominalized verb morphologically has the suffix -ub, which attaches directly to the verbal root. Syntactically, the nominalization exhibits properties of a small structure. However, it has arguments in the same cases as in a finite clause. Example (11) shows a nominalization with the transitive verb u’‹CL›χ- ‘save,’ where the subject bears ergative case, while the direct object is in the absolutive.

Mežgül Tabasaran (Bogomolova 2022)

-

(11)

Following the common derivational model proposed for the Daghestanian languages, cited above, I assume that in Tabasaran, arguments receive their case assignment in an early stage, within vP.

For the next stage of derivation, again based on the papers mentioned above, I make the conventional assumption that the subject moves to Spec,TP, although it is apparently not case-feature checking requirements that cause this movement in the languages.Footnote 8 In addition to this, Tabasaran shows another peculiarity in that in a finite clause the verb does not display its own phi-agreement with the subject. Tabasaran therefore differs from those relative languages that have tense–person morphology.Footnote 9

Although person clitics follow temporal markers in any finite verbal form, they do not associate with T. One piece of evidence that person clitics are not directly tied to TP is that they can be easily separated from tense inflections by other morphological elements, such as by the question marker or particles. The first option is shown in (12) where the question marker -n is inserted between the past tense inflection ji- and the second person clitic =va (the consonant v is dropped; for more discussion of interrogative sentences see Sect. 5).

-

(12)

Assuming the Mirror Principle (Baker 1985), the right-peripheral location of the clitic in a head-final language indicates that it is associated with one of the highest functional heads. In Sect. 6, I identify it as the Log(ophoric) head projected above TP, which hosts clitics.

3.2 Core properties of clitics in an affirmative clause

Let us take a closer look at morphosyntactic behavior of clitics. Clitics are derived from personal pronouns and outwardly resemble them. Table 1 presents the paradigm of personal pronouns in Džuli and corresponding clitics in the absolutive/ergative case. Unlike nouns, neither pronouns nor clitics distinguish between the two cases.

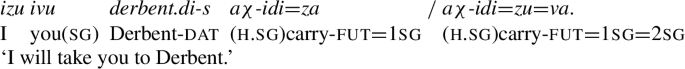

At first glance, the behavior of clitics in a root clause is extremely different from that in reported speech sentences. Both the first and the second person subjects are obligatorily doubled by the corresponding clitic on the verb.Footnote 10 The examples in (13) show intransitive and transitive sentences with the first person subject izu ‘I.’ In both cases, the verbs a ‹CL›G- ‘go’ (13a) and ip’- ‘do’ (13b) bear the 1.sg clitic =za; verbal forms without it are ungrammatical, as shown by an asterisk.

‹CL›G- ‘go’ (13a) and ip’- ‘do’ (13b) bear the 1.sg clitic =za; verbal forms without it are ungrammatical, as shown by an asterisk.

-

(13)

Examples (14) demonstrate sentences with the same verbs a ‹CL›G- ‘go’ (14a) and ip’- ‘do’ (14b), but with the second person subject ivu ‘you (sg).’ The verbs obligatorily bear the 2.sg clitic =va. If the clitic is omitted, the sentences are not felicitous, again shown by an asterisk.

‹CL›G- ‘go’ (14a) and ip’- ‘do’ (14b), but with the second person subject ivu ‘you (sg).’ The verbs obligatorily bear the 2.sg clitic =va. If the clitic is omitted, the sentences are not felicitous, again shown by an asterisk.

-

(14)

In a simple clause, person non-subject arguments can also be optionally doubled with the corresponding person clitic. In the transitive clause in (15a), the direct object is the first person izu ‘I,’ while in (15b) the direct object is expressed by the second person pronoun ivu ‘you(sg).’ In both cases, the arguments can be optionally doubled with corresponding clitics on the verbs, =za in (15a) or =va in (15b).

-

(15)

Although in finite clauses verbal markers obligatorily co-occur with pronominal subjects in a way that resembles a type of agreement, they nevertheless exhibit behavior typical for clitics. In particular, they can form combinations and display several restrictions on them, similar to the Person Case Constraint phenomenon, attested on clitic clusters, for example, in some European languages. In (16) the verb a‹CL›χ- ‘carry’ obligatorily has the subject clitic, 1.sg =za. Alternatively, in this sentence the verb can also attach the object clitic, 2.sg =va, forming the cluster =zu=va.Footnote 11

-

(16)

However, the opposite combination, namely the 2.sg subject clitic with the 1.sg object clitic is systematically blocked, shown in (17) by an asterisk.

-

(17)

3.3 Modern approaches to clitic doubling and clitics in Tabasaran

Before continuing with the presentation of facts and the analysis of indirect speech, I very briefly review the main approaches to clitic doubling. This is far from an exhaustive overview, but it can help highlight characteristic properties of clitics in Tabasaran and show differences with other languages with respect to this familiar phenomenon.

Most current literature applies the movement analysis to clitic doubling (Uriagereka 1995; Anagnostopoulou 2006; Arregi and Nevins 2008; Nevins 2011; Harizanov 2014; among many others; see Kramer 2014 for an overview). At least two types of movement are discussed. The first one assumes that, roughly speaking, the clitic and its associate start out as a single big constituent, where the clitic is a D category that moves from within the DP to a verbal functional head. In some sense, the clitic is similar to a definite determiner (see Kramer 2014 for more discussion). This assumption cannot easily be applied to the Tabasaran data, since we deal with the clitics of the first and second person here and not with the third person.

The second option is that clitic doubling is a result of the movement of the entire DP, where both the lower and higher copies are pronounced. This type of movement has been compared with object shift, and for some researchers it is even identical to it. Non-subject clitics and the absence of object shift in Tabasaran, along with other issues relevant to the topic, are discussed for Mežgül Tabasaran in Bogomolova (2022, Sect. 7). Moreover, Tabasaran is very different from the languages with clitic doubling, since first of all, it has obligatory subject clitics. Modern theories on clitic doubling do not cover the case where both subject and non-subject arguments can be doubled simultaneously. This is, however, a core characteristic of Tabasaran clitics. Furthermore, Tabasaran shows additional conclusive evidence that a clitic and its associate cannot be treated as an outcome of a movement. Regardless of what type of movement is assumed for clitic doubling, the movement is triggered by the agreement mechanism in these approaches. As a result, all phi-features of clitics and their associates always match. However, I will show that in Tabasaran, clitics have their own phi-features (Sect. 5), which may even differ from features of corresponding full DPs (Sect. 8). The reported speech construction is crucial here and reveals the independent clitic behavior from their associate.

The alternative to the movement analysis is a base-generated approach. According to it, clitics are derived in their surface position (Borer 1984; Suñer 1988; Sportiche 1996 for the earliest discussion). However, within this approach clitics are again treated as non-canonical agreement markers, bearing the same features as their full counterparts.

Recently, in their analysis of object markers in Amharic, Baker and Kramer (2018) have proposed a new modification to the theory. With some caution, they assume that in Amharic object markers are also base-generated (however, see Kramer 2014 for a movement analysis applied to the same data). They assume that clitics are independent DPs, interpreted as pronouns and distinct from doubled DPs. Along with phi-feature matching between them, object markers in Amharic enter into relationships of referential dependence with their associate.

Although Tabasaran clitics are again very different from the Amharic object markers and do not fit well into the analysis by the authors, some results of their study partly coincide with my conclusions regarding the Tabasaran data.

To account for clitics in Tabasaran, I propose that: i) clitics are base-generated in the periphery of a finite clause; and ii) they are independent pronominal elements, bearing their phi-features themselves. Reported speech reveals that they have an additional logophoric feature; iii) clitics and full pronouns are in referential dependent relationships and, as I assume they enter binding relationships,Footnote 12 where the pronoun that is bound by the corresponding clitic also receives the logophoric feature, the result is that both refer to the same logophoric participant. Reported speech exposes the original nature of clitics and exhibits a whole set of their properties, which are not visible in a root clause.

4 Clitics in reported speech

This section takes a closer look at reported speech in Tabasaran and at clitic behavior in that context.

4.1 Clitics and shifted interpretations of arguments

In Tabasaran, besides the verb p- ‘say/tell’ (see example (1a) above), different speech verbs such as  - ‘boast,’ nüq’a

- ‘boast,’ nüq’a n ap’- ‘swear’ (lit. ‘swear do’), kčul ap’- ‘tell lies’ (lit. ‘falsehood do’), č’ir ap’- ‘cry’ (lit. ‘cry do’), and žavav tuv- ‘answer’ (lit. ‘answer give’), several mental verbs such as fikir ap’- ‘think’ (lit. ‘thought do’), quʁ- ‘believe,’ and the experiential verb gič’- ‘fear’ also allow for indexical shift. For instance, example (18a) illustrates a sentence parallel to (1) but with the matrix verb gič’- ‘fear.’ The dependent clause demonstrates the same properties as in (1): the first person subject izu ‘I’ doubled with the clitic =za on the embedded verb a

n ap’- ‘swear’ (lit. ‘swear do’), kčul ap’- ‘tell lies’ (lit. ‘falsehood do’), č’ir ap’- ‘cry’ (lit. ‘cry do’), and žavav tuv- ‘answer’ (lit. ‘answer give’), several mental verbs such as fikir ap’- ‘think’ (lit. ‘thought do’), quʁ- ‘believe,’ and the experiential verb gič’- ‘fear’ also allow for indexical shift. For instance, example (18a) illustrates a sentence parallel to (1) but with the matrix verb gič’- ‘fear.’ The dependent clause demonstrates the same properties as in (1): the first person subject izu ‘I’ doubled with the clitic =za on the embedded verb a ‹CL›G- ‘go’ has a shifted interpretation, referring to the reported speaker ‘father.’ Other examples illustrate a similar indexical shift of the first person pronouns izu ‘I’ doubled by the 1.sg clitic =za but under different matrix verbs: ‘tell lies’ in (18b), ‘boast’ in (18c), and ‘believe’ in (18d).

‹CL›G- ‘go’ has a shifted interpretation, referring to the reported speaker ‘father.’ Other examples illustrate a similar indexical shift of the first person pronouns izu ‘I’ doubled by the 1.sg clitic =za but under different matrix verbs: ‘tell lies’ in (18b), ‘boast’ in (18c), and ‘believe’ in (18d).

-

(18)

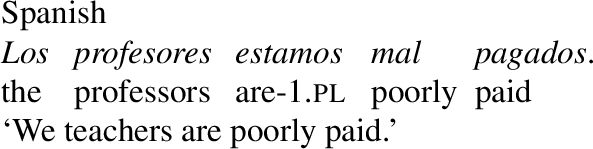

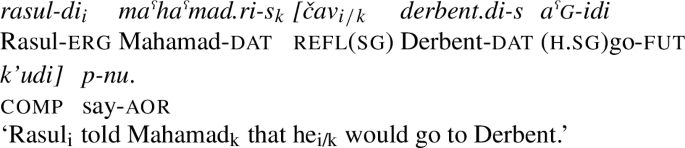

Let me first discuss why this type of sentence does not simply employ direct quotation. Tabasaran has obvious evidence that this is not the case, since in indirect speech we observe syntactic facts prohibited in root affirmative clauses. If these sentences were a case of quotation, they would have the same syntax as simple clauses, but this does not line up with the facts. As we saw above in (13) and (14), in affirmative clauses any pronominal subject is obligatorily doubled with the corresponding clitic. However, in reported speech, a pronominal subject may not be doubled with a clitic, as shown in (2) above for the first person pronoun izu ‘I.’ Examples (19a–19b) demonstrate the same difference with the second person pronoun ivu ‘you(sg).’ In (19a), the verb a ‹CL›G- ‘go’ bears the 2.sg clitic =va, and the pronoun ivu ‘you(sg)’ receives a shifted interpretation, referring to the addressee of the reported speaker, that is, Rasul. However, in example (19b), the embedded verb a

‹CL›G- ‘go’ bears the 2.sg clitic =va, and the pronoun ivu ‘you(sg)’ receives a shifted interpretation, referring to the addressee of the reported speaker, that is, Rasul. However, in example (19b), the embedded verb a ‹CL›G- ‘go’ does not bear the clitic. In contrast to a similar root clause (compare with example (14a)), the sentence in (19b) is felicitous. The difference between (19a) and (19b) is that in (19b) the second person pronoun ivu ‘you’ does not have a shifted interpretation and refers to the addressee of the current speaker.

‹CL›G- ‘go’ does not bear the clitic. In contrast to a similar root clause (compare with example (14a)), the sentence in (19b) is felicitous. The difference between (19a) and (19b) is that in (19b) the second person pronoun ivu ‘you’ does not have a shifted interpretation and refers to the addressee of the current speaker.

-

(19)

Examples (1a), (2), and (19) demonstrate the behavior of pronominal subjects in reported speech. Additionally, in the reported speech, non-subject arguments having a shifted interpretation must also be obligatorily doubled by clitics. Again, this contrasts with the situation in root clauses, where the doubling of the same arguments is always optional (see the examples in (15)). The examples (20) show the contrast. In (20a), the first person pronoun izu ‘I’ in the embedded clause is the direct object. It is doubled on the verb CL-is- ‘catch’ with the 1.sg clitic =za, referring to the reported speaker gagaj ‘father.’ The doubling here is required. If the first person direct object izu ‘I’ is not doubled with the clitic as in (20b), it has another interpretation and refers to the current speaker.

-

(20)

Examples (21a–21b) show the same pattern for the second person non-subject argument. In (21a) the second person direct object ivu ‘you(sg)’ is also obligatorily doubled with the 2.sg clitic =va on the verb CL-is- ‘catch,’ referring to the addressee of the reported speaker. This is the opposite of (21b), where the same argument that is not doubled with the clitic indicates the addressee of the current speaker.

-

(21)

As we see, clitics behave differently in a root affirmative clause, where they are required for pronominal subjects and their absence leads to ungrammaticality, as compared to in reported speech, where the absence of clitics under the same conditions does not yield infelicitous sentences but affects the interpretation of embedded personal pronouns. The rules for doubling with non-subject arguments are also different in simple clauses and reported speech. Contrary to an affirmative sentence, in an embedded report, clitics are obligatorily even for non-subject arguments if the latter have a shifted interpretation.

Thus, all these facts indicate that reported speech in Tabasaran is not a case of quotation (see also Appendix A.2 for standard tests of non-direct quotation).

With this in mind, let me briefly clarify how I treat verbal forms without a clitic in embedded clauses in reported speech as well as in a root clause. In examples (1a), (18), (19a), (20a), and (21a), with reported speech where personal pronouns are doubled with clitics, one can assume that it is the presence of a dedicated operator in the left periphery of the embedded clause that causes the shift with the personal pronouns as well as the shift of verbal inflections. Following this logic, in examples (2), (19b), (20b), and (21b), where the pronouns are not doubled with clitics, the verbal form can be interpreted as a shifted third person form. Such an analysis is proposed for Uyghur by Shklovsky and Sudo (2014), where in indirect speech, personal pronouns can trigger the form that is used with a third person argument instead of the corresponding verbal first or second person form. Similar mismatches are discussed by Messick (2023) for several languages.Footnote 13

In Tabasaran, the verbal form without a clitic is indeed used with nouns and demonstrative pronouns, as shown in example (22a) for a root clause and in (22b) for indirect speech, where the demonstrative pronoun dumu indicates another participant distinct from Rasul.

-

(22)

Below I show that a verbal form without a clitic is not a dedicated form for third person, but rather a bare form that does not contain person information and that can also be used not only with third person arguments but also with the first person pronoun in an interrogative clause (see Sect. 5). For this reason, in reported speech sentences I do not treat verbal forms without clitics like those in (2), (19b), (20b), (21b), and (22b) as shifted third person forms but instead consider them to be bare verbal forms unspecified for any person features.

The following section shows that Džuli does not demonstrate the “shift-together” phenomenon in reported speech and therefore presents an argument counter to the analysis with a context operator. Džuli does not display any blocking effect either, which makes it difficult to apply a binding-based analysis with a binder operator as proposed for the languages cited in Sect. 2.2.

4.2 No “shift-together” or blocking effect in Džuli

Several facts in reported speech are used as diagnostics for either a shifty operator, which overrides context parameters, or the presence of a binder operator, which establishes binding relationships with an embedded argument.

As assumed, the phenomenon “shift-together,” where all indexicals receive their interpretation from the same context, is a piece of evidence that the matrix verb introduces a context operator that is responsible for the shift of all indexicals. However, referring to Leslau (1995: 779), Schlenker (1999: 23) shows that in Amharic, non-“shift-together” is also possible and that two elements—the embedded first person pronoun and first person verbal agreement—can receive their interpretations from different contexts.Footnote 14

Džuli also allows non-“shift-together” where two pronouns are interpreted differently in the embedded report. In (23a), the embedded subject ivu ‘you(sg)’ is not doubled with the corresponding clitic and so refers to the addressee of the current speaker. By contrast, the direct object izu ‘I’ is doubled with the 1.sg=za clitic on the verb CL-is- ‘catch,’ whereby the pronoun shifts and indicates the reported speaker Rasul. So, two pronouns—ivu ‘you(sg)’ and izu ‘I’—in the same embedded clause receive different interpretations: unshifted and shifted, respectively. Similarly, in example (23b) in the embedded clause, the subject izu ‘I’ is not doubled with the corresponding clitic on the verb CL-is- ‘catch’ referring to the current speaker. By contrast, the direct object ivu ‘you(sg)’ doubled with the corresponding clitic of the 2.sg =va on the verb CL-is- ‘catch,’ refers to the addressee of the reported speaker Mahamad and does not indicate the current addressee. Again, two pronominal arguments in the same embedded clause receive their interpretation, unshifted and shifted, from different contexts.

-

(23)

The introduction of a shifty operator overwriting context parameters is problematic in (23). If there were an operator responsible for indexical shift, all pronouns would have to receive the interpretation from the same context (see also Appendix A.3 for a brief discussion of temporal adverbs in embedded reports).

Another diagnostic is the de re blocking effect, which, as assumed, diagnoses the presence of an operator that binds embedded arguments, yielding their shifted interpretation (Anand 2006). Discussing “non-shift-together,” Deal (2018: 82–83) describes the de re blocking effect as an impossibility for the first person subject to remain unshifted while the first person clausemate object shifts. Messick (2023) applies the diagnostics to Telugu and also concludes that the intervention is sensitive to c-command.

What is interesting is that in Džuli, two personal pronouns specified for the same features can refer to participants of different contexts. In example (24), the embedded first person subject izu ‘I’ refers to the current speaker, since the verb does not have the corresponding 1.sg clitic. However, the first person indirect object izu-s ‘I-dat’ is doubled with the corresponding clitic =jas and therefore refers to the reported speaker, rather than to the current speaker. The result is that two first person pronouns have unshifted and shifted interpretations and refer to speakers from different contexts.

-

(24)

The same is possible with the second person pronouns. In example (25), the second person subject ivu ‘you (sg)’ refers to the addressee of the current speaker, since the verb ap’- ‘do’ does not bear the corresponding 2.sg clitic. By contrast, the second person indirect object ivu-s ‘you(sg)-dat’ has a shifted interpretation, since the verb ap’- ‘do’ has the corresponding 2.sg clitic =vu-s.

-

(25)

Thus, Džuli exhibits neither “shift-together” nor the blocking effect. Based on these facts, I claim that the clitics themselves trigger the shift of personal pronouns in the reported speech construction: whenever a pronoun is bound by a clitic, the former obligatorily shifts, referring to logophoric participants, that is, matrix arguments (see also Appendix A.4 for the interpretation embedded arguments in the case of their omission).

My next question is what the nature of the clitics is, whether they affect the interpretation of the personal pronouns. I turn back to root clauses, showing that the origins of the shift with the pronouns are in the syntax of simple clauses. This makes my proposal akin to the reductive approach of Alok and Baker (2018) and Alok (2020). However, in contrast to their theory, where the silent elements Sp and Ad and the personal pronouns they bind are essentially the same, I propose that in Tabasaran, personal pronouns and clitics, which are also in binding relationships, differ in their referential properties, yielding many unusual effects in reported speech. The following section discusses the behavior of clitics in interrogative clauses and shows that the dissociation between clitics and pronouns is possible even in simple sentences.

5 The interrogative clause: Pronouns and clitics are different DPs

In Sect. 3, we saw that personal pronouns and clitics behave very differently in a root clause and reported speech. However, although the subject clitics mimic an obligatory agreement in an affirmative clause, the facts concerning interrogative sentences show that the same binding mechanism between personal pronouns and person clitics involved in a reported speech sentence is also operative in any root clause. An interrogative clause can be a connecting link between two different strategies in the behavior of clitics and personal pronouns in the affirmative clause and the reported speech construction.

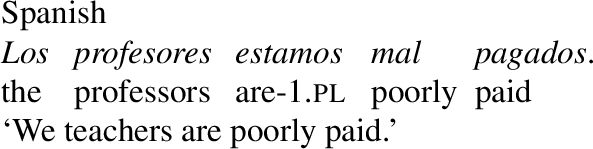

In Tabasaran yes/no questions have a marker -n that is attached to the verbal form after tense inflections (see (12)). In contrast to an affirmative sentence, in any interrogative sentence the first person pronoun is never doubled on the verb with the corresponding first person clitic. Examples (26a–26b) illustrate this difference. (26a) shows the affirmative sentence with the verb a‹CL›q- ‘fall down,’ where the subject is the first person izu ‘I,’ the verb obligatorily bears the 1.sg clitic =za (like in (13a–13b)). The sentence without the clitic =za is not felicitous, as shown by an asterisk. By contrast, example (26b) demonstrates the interrogative sentence with the same verb a‹CL›q- ‘fall down.’ Unlike the affirmative clause, in (26b) the first person subject izu ‘I’ cannot be doubled with the 1.sg clitic =za; the sentence with the clitic is ungrammatical, again shown by an asterisk. (26c) demonstrates a wh-question with the subject izu ‘I,’ where doubling it with the first person clitic is also prohibited.Footnote 15 Examples (26d–26e) demonstrate that the same bare form without a clitic is used with the third person argument Rasul in both yes/no and wh-questions and in the affirmative sentence in (26f) (see also (22a)).

-

(26)

The following examples demonstrate the same strategy with non-subject arguments. In the affirmative sentence in (27a), the first person direct object izu ‘I’ can be optionally doubled with the 1.sg clitic =za on the verb CL-is ‘catch,’ as we discussed above (see also (15a)). However, in example (27b) in the interrogative sentence with the same verb CL-is- ‘catch,’ this option is prohibited and the sentence with the 1.sg clitic =za is ungrammatical.

-

(27)

The interrogative examples (26b–26c) and (27b) immediately show that the first person pronoun here behaves independently of the clitic, which contrasts with the affirmative clause, where the subject pronouns are obligatorily doubled with the corresponding clitics. What is even more interesting is that examples (26b–26c) and (27b) demonstrate a strong parallelism with the indirect speech constructions where personal pronouns can also behave independently of clitics. Example (28) again illustrates that the bare first person pronoun receives an indexical interpretation and does not refer to the logophoric speaker gagaj ‘father.’

-

(28)

My first assumption is that personal pronouns and clitics are separate DPs. As we see, bare personal pronouns (without the corresponding clitic) have their own referential ability, do not depend on the presence of clitics, and behave as real indexicals. The reported speech sentences show that it is the clitics that change the interpretation of pronouns and make them to refer to matrix arguments of the reported clause. Let us assume that clitics themselves, being DPs independent of personal pronouns, have this ability to refer to logophoric participants (following papers on African languages discussing logophoricity: Hagège 1974; Clements 1975; Culy 1997; Huang 2000). Thus, my second assumption is that personal pronouns and clitics are referentially distinct: personal pronouns are indexicals, while clitics indicate logophoric participants. I propose that personal pronouns and clitics are internally specified for different features. Personal pronouns are specified for person features, while clitics, which are also specified for person features, additionally have the Log(ophoric) feature, as shown in (29).

-

(29)

-

a.

pronouns {person}

-

b.

clitics {Log, person}

-

a.

For these reasons, I propose that the pronouns that are coindexed by clitics are in binding relationships with them. Clitics c-command personal pronouns and via binding supply the Log feature to bound personal pronouns with the result that both refer to logophoric participants.Footnote 16

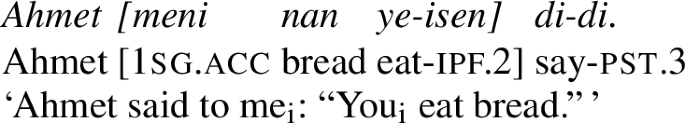

This opens the door for an explanation as to why in the interrogative sentence the first person pronoun cannot be doubled with the first person clitic. This ban is a restriction on the binding relationship between them. According to the proposed analysis, any personal pronoun bound by a clitic refers to a logophoric participant; however, this conflicts with the semantics of interrogative sentences. The speaker who is asking is not a logophoric participant, and especially, is not a source of information.Footnote 17 Therefore, in an interrogative sentence, the first person pronoun cannot be bound by the first person clitic.Footnote 18

However, in an interrogative sentence with the second person pronoun, the second person clitic is still obligatorily present on the verb, since it is assumed that the semantics of an interrogative sentence is that the second person participant is still an attitude holder, the source of information. In example (30a), the second subject ivu ‘you(sg)’ is obligatorily doubled with the clitic =(v)a (the consonant v drops at a morpheme boundary) on the verb CL -is- ‘catch’; the verbal form without the clitic is ungrammatical. Example (30b) shows that the second person direct object ivu ‘you(sg)’ can be also optionally doubled with the clitic =(v)a just as in any root clause.

-

(30)

What happens in an affirmative clause where a pronominal subject is obligatorily doubled by the corresponding clitic? What is strongly reminiscent of an agreement relationship is in fact obligatory binding between personal pronouns and clitics. The mandatory binding in examples like (13) and (14) is due to the fact that the speaker who reports about himself/herself is at the same time a source of information, a logophoric speaker. Via binding, the first person pronoun and person clitic are co-indexed, referring to the logophoric speaker, who referentially coincides with the speaker of the utterance. Since the second person pronoun is always doubled with the corresponding clitic too, we can conclude that the addressee of the speaker is also conceptualized as a logophoric participant. The second person pronoun being bound by the second person clitic is co-indexed and refers to the logophoric addressee who is the addressee of the speaker of utterance.

Let us take stock. First, interrogative sentences having a parallelism with the reported speech sentence demonstrate that the same binding mechanism between clitics and pronouns is present in the syntax of the root clause, which can be a confirmation of Baker’s (2008), Alok and Baker’s (2018), and Alok’s (2020) proposal. Second, in contrast to Alok and Baker (2018), however, who consider that personal pronouns receive their person features via binding with higher elements Sp and Ad and that pronouns and the silent DPs are referentially the same, for Tabasaran I propose that personal pronouns and clitics are independent DPs. Personal pronouns are full-fledged; specifying for person features independently of person clitics, they have their own referential ability to indicate the speaker or his/her addressee. Being DPs, clitics are also specified themselves for person features (see discussion of feature mismatches in Sect. 8 for a strong confirmation of this), and in addition to this, they have the Log(ophoric) feature. In contrast to personal pronouns, a clitic refers to such a logophoric participant, who is obligatorily a source of information or his/her addressee. Personal pronouns entering in binding relationships with clitics receive the {Log} feature, so both items are co-indexed referring to the logophoric speaker or addressee. This mechanism works in any root affirmative clause, as shown in (31).

-

(31)

The bare personal pronouns with no clitic refer to participants without logophoric properties. The interrogative sentence with the first person pronoun demonstrates this behavior, as in (32):

-

(32)

cp[tp[pronoun{1person}]] = Speaker

I address details of the mechanics of these relationships in Sect. 8.3. For now, let us turn to the question as to what introduces the clitic syntactically.

6 Log(ophoric) head

Based on their morphological position after tense markers for clitics in Tabasaran, I introduce the Log head in the periphery of a finite clause above T, which hosts clitics. This assumption leads us to a more general discussion about the correlation of personal pronouns with logophoricity.

6.1 Logophoricity and personal pronouns

As mentioned in Sect. 2, Koopman and Sportiche (1989) treat logophoricity in syntactic terms. For them, some complementizers introduce a silent NP with the [+n] feature, which binds the corresponding embedded n-pronoun,Footnote 19 so that the latter refers to the matrix subject. The authors do not specify the meaning of the feature [n], leaving this question open. In later papers on the topic, the [+n] feature is assimilated to the [+log] feature, and the silent element with the feature [+n] is understood as a log operator (for a recent discussion, see Charnavel and Sportiche 2016; Charnavel 2020).

The notion of log(ophoric) operator is also adopted to explain the phenomenon of long-distance anaphors attested in many languages.Footnote 20 Its behavior is only outwardly long-distance and is reduced to a local binding relationship with a silent log operator. Recently, Charnavel (2020) has discussed exempt anaphors in French.Footnote 21 The core ingredients of her approach are as follows: a Log projection can be introduced in any domain (TP, vP, DP, or other XP) rather than being contingent upon reported speech constructions. The Log head is a logophoric operator, which selects a silent logophoric pronoun referred to as the prolog. The relationship between the prolog and its complement depends on a combination of discourse and syntacticosemantic factors, rather than on syntactic feature interaction. The prolog introduces the first person perspective, while the second person is not taken into account. Therefore, all perspectival elements occurring in the same domain correspond to what the logophoric center could (or did) express in direct discourse in first person.

Making reference to Cable (2005), Kratzer (2009) proposes a local operator, but for first and second person pronouns. Her operator is a context shifter (again comparable to the shifty operators proposed in Anand and Nevins 2004; see Sect. 2), which is additionally equipped with indexical indices, allowing the operator to bind first and second person pronouns. Thus, a Log head in Charnavel (2020), or a λ-operator on a verbal head in Kratzer (2009), functions locally, but Kratzer’s operator works on the basis of feature interaction, rather than discourse factors as in Charnavel (2020).

In his theory of person agreement, Baker (2008: 155) makes the local condition a parameter that distinguishes his Person operators (Sp and Ad) from the Log operator. He assumes that both types of pronouns are always bound by an operator (Sp/Ad for personal pronouns or the Log operator for logophoric pronouns) and that they also have different properties. A logophoric pronoun cannot be used in a root clause, and it can be bound from a distance.Footnote 22 By contrast, first and second person pronouns are typically arguments of a root clause and must be bound by the closest operator (see Sect. 7 for the discussion of Tabasaran clitics with regard to the closest binder).

Bianchi (2001) and Sigurðsson (2004, 2007) view logophoricity as information encoded high in the clause structure. Like Baker, Bianchi also argues that person features have a special status, which in finite clauses manifests itself in person agreement. Any finite form encodes the relation of the event time to the speech event (with reference to Rizzi 1997). The latter constitutes the center of deixis from which the person feature is interpreted. She also uses examples from languages with logophoric pronouns and discusses the fact that they are sensitive to the internal deictic center. She concludes that the deictic center is just a particular manifestation of the logophoric center of any clause. Thus, Bianchi’s assumption correlates with Baker’s: logophoric and personal pronouns are subject to the same conditions. However, while in Baker’s theory, pronouns are bound by different operators (Log or Person), in Bianchi’s approach, both types of pronouns are interpreted from logophoric centers: logophoric pronouns must be interpreted from the internal log center, while personal pronouns are interpreted from the external log center corresponding to the perspective of the external speaker and addressee. Since the logophoric center is endowed with (possible) spatial and temporal coordinates and logophoric roles, personal pronouns, anchored to the logophoric center, result in person agreement.

Sigurðsson’s (2004, 2007) proposal is in general similar to Bianchi’s idea: features of the speech event are syntactically present. However, in his approach, logophoric features are not given as a whole package (space, time, log participants) but rather are separate features. He assumes that a final person category grows as a result of a strictly inferential relationship between three clausal levels, [speech features [grammatical features [event features]]]. Sigurðsson’s derivational hypothesis is thus close to Baker’s (2008) derivational person theory, where personal pronouns get their completeness by being obligatorily bound by the higher elements. However, the difference between the two proposals is that for Sigurðsson these elements are not only the speaker and the addressee, but also logophoric participants, while for Baker they are only the Speaker and the Addressee.

The list in (33) lays out the parameters discussed above for logophoricity:

-

(33)

-

a.

Nature of the Log operator: i) head (Charnavel 2020), ii) DP elements (Koopman and Sportiche 1989; Sigurðsson 2004, 2007; Baker 2008; Kratzer 2009), iii) log center (Bianchi 2001).

-

b.

Location of the Log operator/center: i) reported speech (Koopman and Sportiche 1989; Baker 2008), ii) finite domain (Bianchi 2001; Sigurðsson 2004, 2007); iii) phases/the closest head (Kratzer 2009; Charnavel 2020).

-

c.

The correlation of Log operator/center and person: i) The Log operator is distinct from the Person operator (Baker 2008). ii) The Log operator consists of person information: 1) via indexical indices (Kratzer 2009); 2) introduces the person perspective of first person (Charnavel 2020); 3) the log center includes speech participants (Bianchi 2001) or, more precisely, the logophoric speaker and addressee (Sigurðsson 2004, 2007).

-

d.

Relationships between the Log operator/center and its target: i) feature interaction (Koopman and Sportiche 1989; Sigurðsson 2004, 2007; Baker 2008; Kratzer 2009); ii) person features are anchored by the log center and are realized in person agreement (Bianchi 2001); iii) the relationship between the prolog and its complement is based on a combination of discourse and syntacticosemantic factors (Charnavel 2020).

-

a.

If my analysis is on the right track, the Tabasaran data provide evidence that, indeed, any finite clause can project the Log head above T (see the contrast shown between the finite clause and the non-finite converb clause in examples (1a–1b) in Sect. 1). However, what is interesting is that the Džuli dialect also demonstrates that a verbal form need not necessarily be tense-marked for clitics to appear on it. In spoken texts, I also found jussive forms that do not morphologically have tense markers but nevertheless include clitic doubling. Further research is needed for a more detailed analysis of the relationship between finiteness and the Log projection.

As I propose, clitics are DPs, themselves specified for person and Log features, and they encode both Log participants, Speaker as well as Addressee. However, other coordinates like space and time are not involved (at least overtly; see also Appendix A.3, a discussion about temporal adverbs in reported speech). Therefore, there is no evidence that the Log head introduces a logophoric center with a whole package of coordinates, so it cannot be treated in terms of perspective (at least for Tabasaran).

I also assume that the Log head specified for [person] and [logophoric] features functions as a probe, searching for a DP with the appropriate features. Whenever an argument with [person] features is present in an affirmative clause, the Log head introduces the corresponding clitic and adds the [log] feature to a personal pronoun. The Log head is also sensitive to the [log] feature. This is especially visible in reported speech, since there the logophoric anaphor can also optionally be bound by clitic (Sect. 8.1).

The following section provides an additional piece of evidence that personal pronouns are fully specified for person features themselves and that their referential ability is independent from clitics.

6.2 Full-fledged pronouns

Nominalized clauses such as in (11) (see Sect. 3.1) can also be informative for the feature specification of personal pronouns in Tabasaran. In particular, an anonymous reviewer asks me whether personal pronouns can be treated in the mold of Baker’s (2008) and Alok and Baker’s (2018) theory as items that receive their full referential content via binding with high silent Sp and Ad elements.Footnote 23 Gender-number agreement within the nominalized clause shows that this is not the case. Like other languages of the family, Tabasaran displays gender–number agreement with an absolutive argument, that is, with a direct object in a transitive clause, and distinguishes between non-human singular (n.sg in glosses) and other DPs, human singular and plural (h.sg and pl in glosses correspondingly). In (11), repeated in (34a) the transitive verb u’‹CL›χ- ‘save’ has the absolutive argument Mahamad, which is human, the verb has the corresponding human gender–number marker ‹r› (h.sg in glosses). (34b) demonstrates a very similar sentence but with the non-human absolutive direct object gatu ‘cat,’ with the verb bearing the non-human gender–number marker ‹b› (glossed as n.sg); the human gender marker ‹r› is ungrammatical here.

-

(34)

What is important for the current discussion is that gender–number agreement with personal pronouns directly depends on their referential properties. For instance, typically, first person pronoun indicates a human speaker. In this case the verb reflects human singular gender–number agreement, as in (35a), where the verb u ‹r›χ- ‘save’ has the human singular marker ‹r›, similar to (34a). However, for example, in a fairy tale narrative the speaker can be non-human, for instance, an animal. In this case, the first person pronoun in the absolutive direct object position triggers the non-human marker ‹b› on the verb, shown in (35b), similar to example (34b), and the human singular marker ‹r› is impossible in this case.

‹r›χ- ‘save’ has the human singular marker ‹r›, similar to (34a). However, for example, in a fairy tale narrative the speaker can be non-human, for instance, an animal. In this case, the first person pronoun in the absolutive direct object position triggers the non-human marker ‹b› on the verb, shown in (35b), similar to example (34b), and the human singular marker ‹r› is impossible in this case.

-

(35)

Taking into account that the nominalization is a clause of a smaller size than a finite sentence (see discussion in Sect. 3.1), we can conclude that even in this environment, personal pronouns already have their referential content, which apparently does not depend on finiteness and, more generally, on higher projections.Footnote 24

With this in mind, let’s take a closer look at how the binding mechanism between clitics and personal pronouns works in reported speech sentences.

7 The mechanics of indexical shift in reported speech in Tabasaran

In the reported speech construction, the mechanism of binding is the same as in a root clause. The only difference is that in a root clause the current speaker is at the same time also the logophoric speaker, and the addressee of the logophoric/current speaker is the logophoric addressee. This referential identity (between discourse and logophoric participants) is reflected in the fact that personal pronouns must obligatorily be doubled by clitics in any affirmative clause. By contrast, in the reported speech construction two speakers (current and logophoric), as well as two addressees (that of the current speaker and that of the logophoric speaker), are referentially distinguished. This split between participants is reflected in the dissociation between the personal pronouns and the clitics in reported speech.

The mechanics of the binding in the reported speech is as follows. The embedded clause of the reported speech, like other finite root clauses, is able to have its own Log projection and therefore introduce clitics in its periphery. Clitics, being specified for the feature {Log}, always indicate logophoric participants; therefore, in reported speech, they always refer to matrix arguments: the 1.sg clitic indicates the logophoric speaker, while the 2.sg clitic indicates the logophoric addressee (for a more detailed discussion of the relationship between matrix arguments and clitics see Sect. 9; for the current purpose I will refer to this relationship as binding). Clitics specified for person features bind personal pronouns within the same embedded domain. Bound personal pronouns receive the same referential interpretation as clitics resulting in indexical shift: the first person pronoun bound by the first person clitic refers to the reported speaker, shown in (36a); the second person pronoun bound by the second person clitic shifts and refers to the addressee of the reported speaker, as in (36b).

-

(36)

It should be also noted that a personal pronoun bound by a clitic can only refer to the closest antecedent. In example (37), in doubled embedded clauses, the shifted bound first person pronoun izu ‘I’ refers only to the matrix subject of the clause immediately above it, to the reported speaker Ahmed, and not to the highest matrix subject Rasul. Thus, clitics in Tabasaran display properties of Baker’s (2008) Person operator and demonstrate the closest relationship with its antecedent.

-

(37)