Abstract

This study examines the interaction of the Japanese modal auxiliary daroo with different sentence types and intonation. A detailed investigation of daroo reveals an interesting paradigm with respect to parameters such as clause type, boundary tone, tier of meaning and pragmatic context. I propose that daroo is a use-conditional speech act operator which asserts the epistemic knowledge of the speaker. The proposal is formally implemented in the framework of inquisitive epistemic logic. That is, daroo marks an assertion of an entertain modality. A rising intonational contour is analyzed as a prosodic morpheme that is paratactically associated to its host and functions as a use-conditional question operator that renders a truth-conditional declarative into a use-condition of question act. A new composition rule that indicates how to interpret paratactically associated use-conditional items is also proposed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

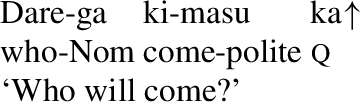

Following the standard practice in the literature of formal semantics and philosophy of language, I use the term “interrogative” to refer to a type of syntactic clause and the term “question” to refer to its semantic content (see Cross and Roelofsen 2020).

(2) is less marked than (1) with rising intonation ↑. Intuitively, the speaker of (1) seems to be a male talking to his junior, while (2) does not have such a connotation: the speaker could be either male or female and they are casually talking to their friends.

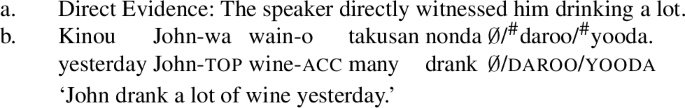

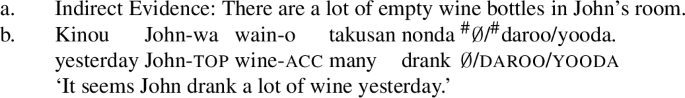

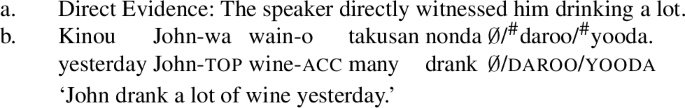

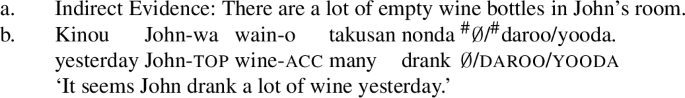

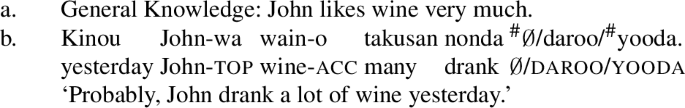

As observed by Hara (2006), daroo has an additional interesting semantic-pragmatic property. That is, α-daroo cannot be used when the speaker has direct/indirect evidence for the prejacent α, as can be seen in the translations of Izvorski’s (1997) “Wine bottle scenario” (i)–(ii).

-

(i)

-

(ii)

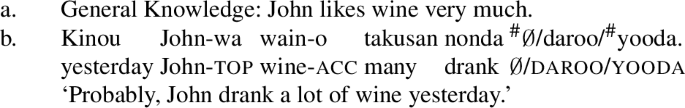

When can α-daroo be used? It is actually not very easy to characterize the exact range of felicitous situations. According to Hara (2006), α-daroo denotes the speaker’s epistemic bias for α as derived from reasoning and not from observable (direct or indirect) evidence.

-

(iii)

I adopt Hara and Davis’s (2013) explanation. Hara and Davis (2013) argue that Hara’s (2006) characterization of daroo is not ideal because it is negatively defined. Instead, Hara and Davis (2013) employ Optimality Theoretic Pragmatics (Blutner and Zeevat 2004; Zeevat 2004) and show that the distribution of daroo can be explained as a result of pragmatic competition. In a nutshell, the definition of daroo does not lexically encode the evidencelessness condition, and it simply expresses the bias toward the prejacent proposition. Now, daroo is in competition with the bare assertion (indicated by ∅ in (ib)-(iiib)) and the evidential yooda ‘it seems.’ When the speaker has direct evidence, she should assert the bare form as in (ib), since it is the most economical, hence optimal. When the speaker only has indirect evidence, the speaker should choose the yooda ending as in (iib), since it lexically encodes the evidential meaning (Hara 2017; Hara et al. 2020). Elsewhere, daroo is used as in (iiib). Thus, following Hara and Davis (2013), I do not have any evidence-sensitivity condition in the lexical semantics of daroo presented in Sect. 3.3.

-

(i)

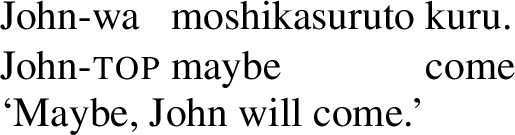

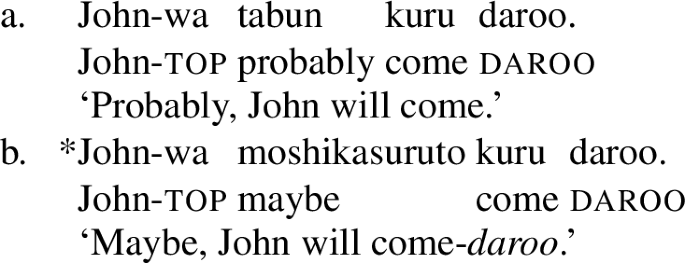

Furthermore, Hara (2006) shows that daroo takes a higher scope than other “normal” modals and argues that there are two kinds of modalities in Japanese, root-level and proposition-level. The root-level modals include daroo, tabun/kitto ‘probably/certainly’ and moshikasuruto ‘maybe,’ while the proposition-level modals include kanarazu ‘certainly,’ and kanoosei-ga aru/hikui ‘the possibility exists/is low.’ See Sect. 3.3.2 and Appendix C.

When daroo is embedded under an attitude predicate, the holder of the bias can be the subject of the attitude predicate as well. See footnote 31.

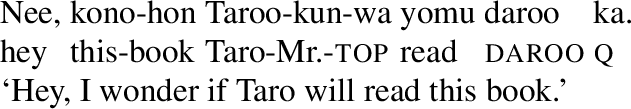

An anonymous reviewer questioned this self-addressing nature of the construction since in (12), a falling daroo-interrogative seems to be used to address the hearer:

-

(i)

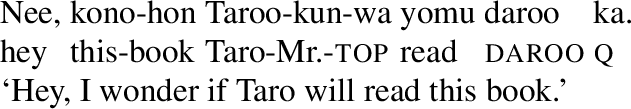

I argue that the utterance in (11) is interpreted as a question directed to the addressee at the pragmatic level. In other words, the construction semantically denotes a description of the speaker’s epistemic state, i.e., it indicates that the speaker is entertaining an issue (see Sect. 4 for the formal implementation). Together with a discourse marker like nee ‘hey,’ the utterance pragmatically functions as an indirect question act just as in the English translation ‘I wonder ...’ which can function as a question directed at the hearer.

-

(i)

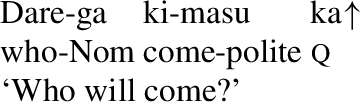

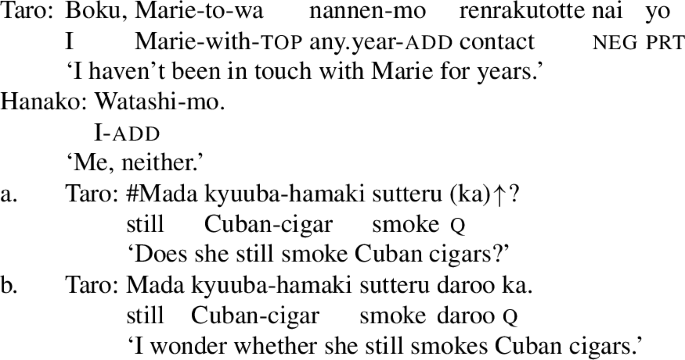

Rising intonation (↑) is not optional in (16) since the interpretation would change if it is uttered without ↑, namely with falling intonation as in (16).

-

(i)

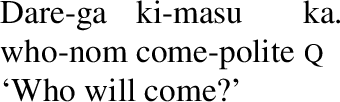

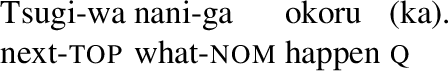

Intuitively, (15) is a mere statement of an issue of what happens next, rather than a question addressed to someone. The semantics of tonally unmarked ka proposed in Sect. 3.4 explains this intuition.

-

(i)

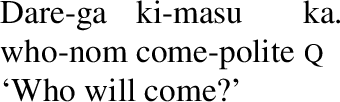

I owe this example to an anonymous reviewer. The interaction between daroo and wh-interrogatives is analyzed in Sect. 4.5.

I owe example (19) to an anonymous reviewer.

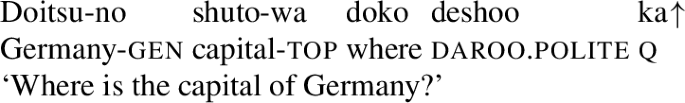

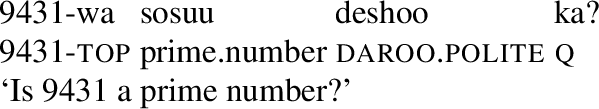

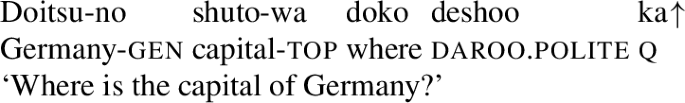

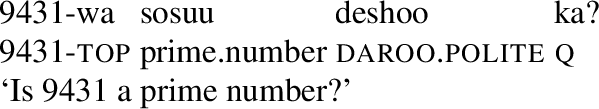

The sentences that Sudo (2013) examines end with desho as in (20). Desho(o) is a polite form of daroo. Sudo (2013) treats desho as a question particle and name the sentences like (20) as positive polarity questions (PPQs) with -desho. I consider them rising daroo-declaratives as desho(o)-sentences have exactly the same interpretational paradigm as daroo-sentences.

-

(i)

-

(i)

I owe example (20) to an anonymous reviewer.

Daroo-interrogatives with a variant of Final Rise L%H%, namely Final High H%, can be made felicitous in a very particular kind of context. See footnote 42.

The judgements are empirically justified by two experimental tasks with fourteen participants each.

\(\varSigma _{a}(w)\) observes factivity and introspection conditions. See Definition 3 in Ciardelli and Roelofsen (2015: 1651).

The same state depicted in Fig. 4 supports \(K_{a} ?\alpha \).

More precisely, φ-daroo translates to the assertion of Eφ. See Sect. 3.3.1.

Entailment is defined as follows:

-

(i)

(Definition of Entailment)

We say that a sentence φ entails another sentence ψ (notation φ⊨ψ) just in case for all states p, if p∈〚φ〛, then p∈〚ψ〛.

(Ciardelli and Roelofsen 2015: 1657)

-

(i)

Equivalence is defined as follows:

-

(i)

(Definition of Equivalence)

We say that two sentences φ and ψ are equivalent (notation φ≡ψ) just in case for all states p, p∈〚φ〛⇔p∈〚ψ〛.

(Ciardelli and Roelofsen 2015: 1657)

-

(i)

This is by no means the exhaustive list. See Gutzmann (2015: 9) for a more extensive list, though probably it is not a fully exhaustive one, either.

Farkas and Bruce’s (2010) original structure has another component, the projected set ps which represents possible common grounds, which I do not include in (45) as it does not play a role in characterizing the use conditions of speech acts.

Here, I depart from Gutzmann (2015), who draws a strict distinction between sentence mood and illocutionary force or speech act. According to Gutzmann (2015), syntactic sentence types only determine sentence moods, which in turn constrain what kind of illocutionary forces are possible. In analyzing an English expressive question construction, e.g., Angry, much? (Gutzmann and Henderson 2019), however, Gutzmann also analyzes a syntactic construction as a direct correlate of a context update in Gunlogson’s (2008) model.

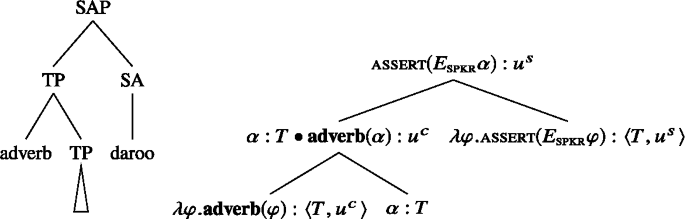

I do not fully adopt \(\mathcal{L}_{\mathit{CI}}^{+S}\) because the current paper does not deal with prototypical expressive items (Potts 2005) nor mixed contents (McCready 2010), so many of the type specifications and combinatoric rules presented there are unnecessary for the purposes of the current paper. Furthermore, a new basic type u and a new rule Paratactic Association are added to \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}\). See Appendix B for the complete type specifications and combinatoric rules of \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}\).

Gutzmann (2015) does not treat use-conditional items such as sentence moods as shunting-typed, so they project both truth-conditional and use-conditional meanings. Gutzmann and Henderson (2019), in contrast, analyze the English x-much? question like (55) as a shunting-typed UCI, which projects only a use-conditional meaning.

The configuration given in (67) may seem unconventional in Japanese linguistics as the semantic composition of Japanese sentences is relatively faithful to the surface linear order as pointed out by an anonymous reviewer. In fact, Japanese does have some constructions the interpretations of which do not reflect their linear order. For example, there are cases where the linear order does not affect the meaning, although there are syntactic restrictions on the order between the past tense and the polite form depending on the category of the root predicate. Japanese has two syntactic categories for adjectives: one is keiyoodoosi ‘adjectival noun’ and the other is keiyoosi ‘adjective.’ When the root predicate is an adjectival noun as in (68), the polite form precedes the past tense.

-

(i)

In contrast, when the root is an adjective as in (68), the past tense precedes the polite form.

-

(ii)

This difference in linear order does not affect how their meanings are composed, since both mean ‘It was pretty/interesting’ and are politely uttered. Furthermore, (67) apparently violates the Head Movement Constraint. See Appendix A for English constructions that involve head movement which also violate the Head Movement Constraint.

-

(i)

Emonds (1969: 6) defines a root sentence as “either the highest S in a tree, an S immediately dominated by the highest S or the reported S in direct discourse.”

This is also a property of non-truth-conditional content. See Sect. 5.1.

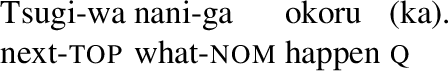

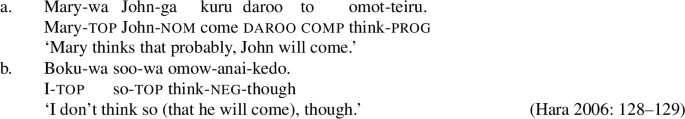

As seen in (29), the holder of the bias can be attributed to the agent of attitude predicates, i.e., the speaker of the embedded speech act. In (ia), for instance, the bias expressed by daroo is attributed to Mary, since the speaker can felicitously challenge the content of the bias as in (ib):

-

(i)

Potts (2005) claims that expressives and conventional implicatures are invariably speaker-oriented. This idea has been challenged by many scholars (Amaral et al. 2007, among others). In Harris and Potts (2009, 2011), Potts also concludes that the speaker-orientedness is not an essential feature of expressive meanings. Since it is beyond the scope of the current paper, I do not attempt to provide a fully compositional analysis of (i) and instead simply assume that attitude predicates can embed expressive/use-conditional content and shift the holder of the bias expressed by daroo.

-

(i)

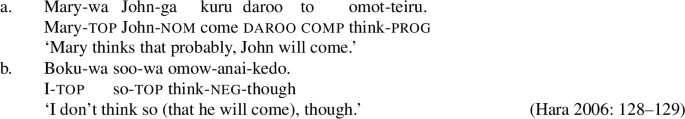

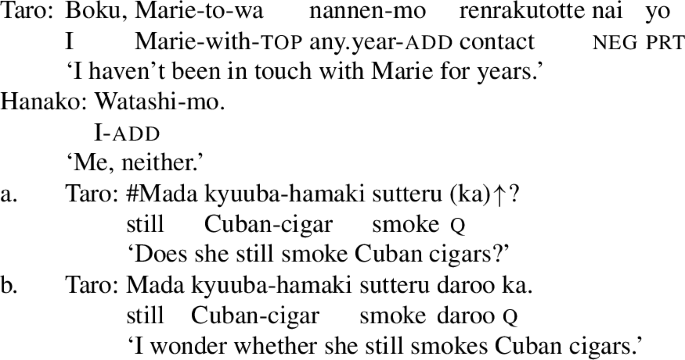

The Final Rise with/without the particle ka (-ka)↑ seems to have an addressee knowledge presupposition as can be seen in the translation of Truckenbrodt’s (2006b: 274) “Cuban cigar scenario”:

-

(i)

Taro’s question in (ia) is strange because it is common knowledge that Hanako does not know about Marie’s current smoking habits. On the other hand, (ib) is an appropriate utterance given the previous discourse. Thus, φ(-ka)↑ presupposes that the addressee knows the answer to 〈?〉φ, i.e.,

. We could incorporate this presupposition in the use conditions of (-ka)↑ as in (85):

. We could incorporate this presupposition in the use conditions of (-ka)↑ as in (85): -

(ii)

Use-conditions of (-ka)↑ with addressee knowledge presupposition

Alternatively, the presupposition could be part of the quest operator in general. Since the data at hand do not provide a way to distinguish the two options, I do not include this presupposition in the use conditions of (-ka)↑.

-

(i)

The term “paratactic association” is adopted from Lyons (1977), who analyzes performative verbs that are tagged sentence-finally as in (ia).

-

(i)

-

a.

I’ll be there at two o’clock, I promise you. (Lyons 1977: 738)

-

b.

I’ll be there at two o’clock ⊗ I promise you.

-

a.

According to Lyons (1977: 738), the second clauses in (ia) is attached as parenthetical modulation or is paratactically associated as schematically shown in (ib), thus the whole utterance projects two speech acts, one that performs the act of promising and the other that “confirms, rather than establishes, the speaker’s commitment.”

Thus, paratactic association is a relation between the main sentence and a sentence-final expression that projects an illocutionary force independent of the main sentence.

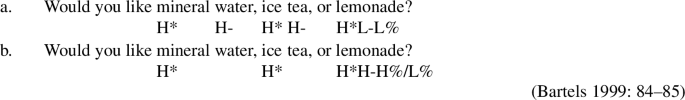

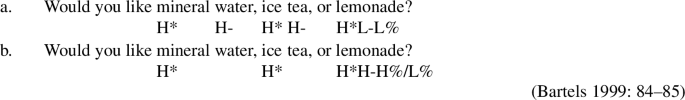

Bartels (1999) applies this idea to her analysis of the Final Fall in alternative questions like (iia). It has been observed in the literature that alternative questions must end with a Final Fall, H*L-(L%) (Bolinger 1958). When the same string of words is uttered without Final Fall as in (iib), it is unambiguously understood as a yes-no question.

-

(ii)

Based on these observations, Bartels (1999) proposes that the final L- phrase accent in (iia) denotes the assert morpheme and is paratactically associated with the utterance as in (90).

-

(iii)

Would you like mineral water, ice tea, or lemonade ⊗ assert

In effect, the alternative question like (iia) performs two speech acts: one is the question denoted by the main interrogative clause and the other is an assertion of the disjunctive statement, ‘You would like mineral water, ice tea, or lemonade.’

-

(i)

See Appendix B for the full system of \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}\).

See Sect. 4.3 for a full composition of rising daroo declaratives.

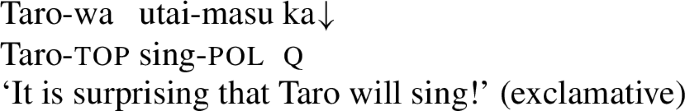

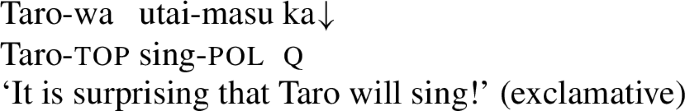

This line of analysis is compatible with Uegaki & Roelofsen’s (2018) observation that a root-level interrogative without rising intonation tends to be interpreted as an exclamative as in (100) (Uegaki & Roelofsen’s (14)). Since α-ka simply denotes a truth-conditional interrogative sentence, it can be an argument of another functor like an Exclamative Act Operator. See also Appendix D.

-

(i)

Taro-wa utai-masu ka.

‘It is surprising that Taro will sing!’ (exclamative)

-

(i)

One may wonder whether it is possible to remove ka↑ from the lexicon by deriving its semantics from the semantics of ka and ↑. This line of analysis indeed does not make a difference to the simple rising interrogative discussed here but it makes a wrong prediction for the rising daroo interrogative discussed below in Sect. 4.4.

I would like to thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

An anonymous reviewer reports their intuition that the bias expressed by falling α-daroo is somewhat weaker than the one expressed by rising α-daroo. This intuition can be explained by observing the pragmatic competition between α and α-daroo. In my analysis, falling α-daroo is an assertion of

, and so pushes the modalized sentence

, and so pushes the modalized sentence  onto the Table. When the addressee accepts the speaker’s assertion, therefore, what enters the common ground will be

onto the Table. When the addressee accepts the speaker’s assertion, therefore, what enters the common ground will be  , not α. On the other hand, rising α-daroo is a combination of two speech acts, an assertion of

, not α. On the other hand, rising α-daroo is a combination of two speech acts, an assertion of  and a question ?α. The question act pushes the issue ?{α,¬α} as well as

and a question ?α. The question act pushes the issue ?{α,¬α} as well as  onto the Table, so when the addressee responds with ‘yes’, α will enter the common ground.

onto the Table, so when the addressee responds with ‘yes’, α will enter the common ground.A variant of α-daroo ka↑ with a Final High H% instead of Final Rise L%H% seems to become possible, if we have an appropriate context. For instance, in a quiz show or an instructive/Socratic questioning context, the questioner can felicitously utter a rising interrogative α-daroo ka↑ to the answerer (I owe (ii) to an anonymous reviewer):

-

(i)

-

(ii)

Deshoo is the polite form of daroo. I speculate that the Final High functions as a shifter of the epistemic agent from spkr to addr. In a quiz show context like (114), the speaker, i.e., the quizmaster, indeed has the power to impose a question on the addressee, i.e., the contestant. Thus, Final Rise is a modifier of daroo rather than an interrogativizer.

-

(i)

See Ciardelli et al. (2017) for a full-fledged compositional system in inquisitive semantics.

An anonymous reviewer noted that the following sentence can be used as an information-seeking question:

-

(i)

My intuition is that (122) with Final Fall is less natural than (123) with Final Rise, though I agree that an information-seeking interpretation of (122) in some limited contexts is not impossible. I speculate that in (122), the addition of the polite morpheme masu invokes a presupposition of the presence of an addressee, which in turn invokes a covert quest operator.

-

(ii)

-

(i)

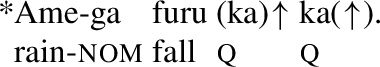

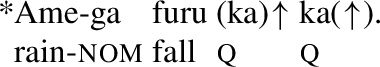

(Ka)↑ cannot be embedded under another question particle:

-

(i)

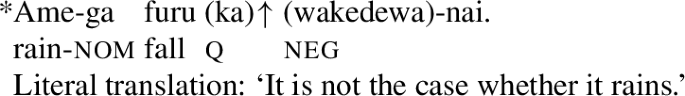

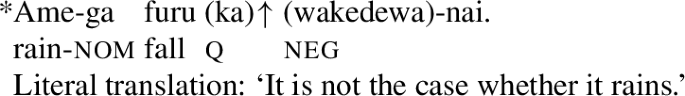

Neither the affixal nor the sentential negation can embed ka↑ or ↑:

-

(ii)

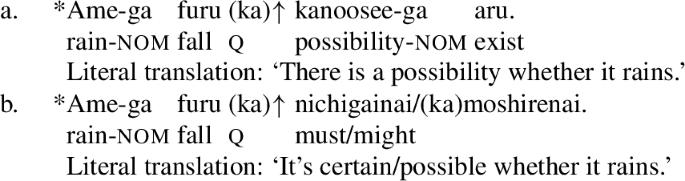

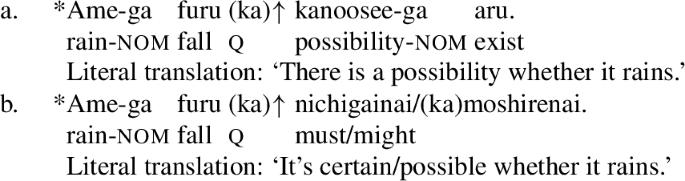

Modal expressions cannot follow ka↑ or ↑ (Etymologically, ka in kamoshirenai ‘might’ is arguably derived from the question particle ka. In any case, neither moshirenai nor kamoshirenai can follow ka↑ or ↑.):

-

(iii)

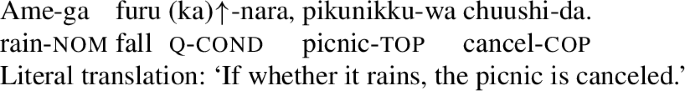

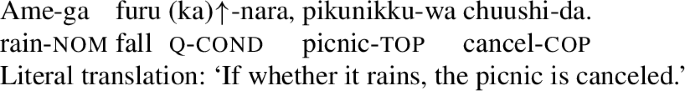

Finally, (ka)↑ cannot be in the scope of a conditional antecedent:

-

(iv)

-

(i)

Evidential/sentience markers are different from attitude predicates in that they cannot shift the attitude holder of the bias of daroo (10) while attitude predicates can (i). See Hara (2006: Ch. 6) for more discussion.

See Appendix D for other problems of U&R’s analysis.

References

Amaral, Patricia, Craige Roberts, and E. Allyn Smith. 2007. Review of The logic of conventional implicatures by Chris Potts. Linguistics and Philosophy 30(6): 707–749.

Barker, Chris. 2009. Clarity and the grammar of skepticism. Mind & Language 24: 253–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0017.2009.01362.x.

Bartels, Christine. 1999. The intonations of English statements and questions. New York: Garland.

Blutner, Reinhard, and Henk Zeevat, eds. 2004. Optimality theory and pragmatics, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bolinger, D. 1958. Interrogative structures of American English: The direct question. In American dialect society, Vol. 28. Birmingham: University of Alabama Press.

Brandt, Margareta, Marga Reis, Inger Rosengren, and Ilse Zimmermann. 1992. Satztyp, satzmodus und illokution. In Satz und illokution, ed. Inger Rosengren. Vol. i, 1–90. Max Niemeyer Verlag.

Büring, Daniel, and Christine Gunlogson. 2000. Aren’t positive and negative polar questions the same? Ms., USCS/UCLA.

Ciardelli, Ivano A., and Floris Roelofsen. 2015. Inquisitive dynamic epistemic logic. Synthese 192(6): 1643–1687.

Ciardelli, Ivano, and Floris Roelofsen. 2018. An inquisitive perspective on modals and quantifiers. Annual Review of Linguistics 4: 129–149. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurevlinguistics-011817-045626.

Ciardelli, Ivano, Floris Roelofsen, and Nadine Theiler. 2017. Composing alternatives. Linguistics and Philossophy 40: 1–36.

Cinque, G. 1999. Adverbs and functional heads: A cross-linguistic perspective. London: Oxford University Press.

Cross, Charles, and Floris Roelofsen. 2020. Questions. In The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

Davis, Christopher. 2009. Decisions, dynamics and the Japanese particle yo. Journal of Semantics 26: 329–366.

Davis, Christopher. 2011. Constraining interpretation: Sentence final particles in Japanese. PhD diss, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Emonds, Joe. 1969. Root and structure-preserving transformations. PhD diss, MIT.

Farkas, Donka. F., and Kim. B. Bruce. 2010. On reacting to assertions and polar questions. Journal of Semantics 27(1): 81–118.

Farkas, Donka F., and Floris Roelofsen. 2017. Division of labor in the interpretation of declaratives and interrogatives. Journal of Semantics 34(2): 237–289. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/w012.

Grice, H. Paul. 1975. Logic and conversation. In Syntax and semantics, vol. 3: Speech act, eds. Peter Cole and Jerry Morgan, 43–58. New York: Academic Press.

Gunlogson, Christine. 2003. True to form: Rising and falling declaratives as questions in English. New York: Routledge.

Gunlogson, Christine. 2008. A question of commitment. Belgian Journal of Linguistics 22: 101–136. https://doi.org/10.1075/bjl.22.06gun.

Gutzmann, Daniel. 2015. Use-conditional meaning: Studies in multidimensional semantics. London: Oxford University Press.

Gutzmann, Daniel, and Robert Henderson. 2019. Expressive updates, much? Language 95(1): 107–135. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2019.0014.

Hamblin, Charles L. 1973. Questions in montague English. Foundations of Language 10: 41–53.

Hara, Yurie. 2008. Evidentiality of discourse items and because-clauses. Journal of Semantics 25(3): 229–268.

Hara, Yurie. 2017. Causality and evidentiality. In Proceedings of the 21st Amsterdam colloquium, eds. Alexandre Cremers, Thom van Gessel, and Floris Roelofsen, 295–304.

Hara, Yurie. 2018. Daroo as an entertain modal: An inquisitive approach. In Japanese/Korean linguistics, eds. Shinichiro Fukuda, Mary Shin Kim, Mee-Jeong Park, and Haruko Minegishi Cook, Vol. 25, 1–13. CSLI Publications.

Hara, Yurie. 2006. Japanese discourse items at interfaces. PhD diss, University of Delaware.

Hara, Yurie, and Christopher Davis. 2013. Darou as a deictic context shifter. In Proceedings of formal approaches to Japanese linguistics 6 (FAJL 6), eds. Kazuko Yatsushiro and Uli Sauerland. Vol. 66 of MIT working papers in linguistics, 41–56.

Hara, Yurie, Naho Orita, Deng Ying, Takeshi Koshizuka, and Hiromu Sakai. 2020. A neurolinguistic investigation into semantic differences of evidentiality and modality. In Proceedings of sinn und bedeutung 24, 273–290.

Hare, Richard Mervyn. 1952. The language of morals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harris, Jesse A., and Christopher Potts. 2009. Perspective-shifting with appositives and expressives. Linguistics and Philosophy 36(2): 523–552.

Harris, Jesse A., and Christopher Potts. 2011. Predicting perspectival orientation for appositives. In Proceedings from the 45th annual meeting of the Chicago linguistic society, Vol. 45, 207–221.

Heim, Irene. 1994. Interrogative semantics and Karttunen’s semantics for know. In The proceedings of the ninth annual conference and the workshop on discourse of the Israel association for theoretical linguistics, eds. R. Buchalla and A. Mittwoch, 128–144. Jerusalem: Academon.

Heim, Irene. 1982. The semantics of definite and indefinite noun phrases. PhD diss, University of Massachussets, Amherst.

Homer, Vincent. 2011. As simple as it seems. In Proceedings of the 18th Amsterdam colloquium, eds. Maria Aloni, Vadim Kimmelman, Floris Roelofsen, Galit Weidman Sassoon, Katrin Schulz, and Matthijs Westera, 351–360.

Hooper, Joan, and Sandra Thompson. 1973. On the applicability of root transformations. Linguistic Inquiry 4: 465–497.

Izvorski, Roumyana. 1997. The present perfect as an epistemic modal. In The proceedings of SALT 7, 222–239.

Jacobson, Pauline. 2006. I can’t seem to figure this out. In Drawing the boundaries of meaning: Neo-Gricean studies in pragmatics and semantics in honor of Laurence R. Horn, eds. B. J. Birner and G. Ward. Vol. 80 of Studies in language companion series, 157–175. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Jakobson, Roman. 1960. Linguistik und poetik. In Poetik, ed. Ronan Jakobsen, 83–121. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

Kaplan, David. 1999. The meaning of ouch and oops: Explorations in the theory of meaning as use. [2004 version.] Ms., University of California.

Karttunen, Lauri. 1972. Possible and must. In Syntax and semantics, ed. John Kimball. Vol. 1, 1–20. Seminar Press.

Karttunen, L. 1977. Syntax and semantics of questions. Linguistics and Philosophy 1: 3–44.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1991. Modality. In Semantics: An international handbook of contemporary research, eds. A. von Stechow and D. Wunderlich, 639–650. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Krifka, Manfred. 2001. Quantifying into question acts. Natural Language Semantics 9: 1–40.

Lahiri, Utpal. 2000. Lexical selection and quantificational variability in embedded interrogatives. Linguistics and Philosophy 23(4): 325–389.

Langendoen, D. Terence. 1970. The ‘can’t seem to’ construction. Linguistic Inquiry 1(1): 25–35.

Lassiter, Daniel. 2014. The weakness of must: In defense of a mantra. In Proceedings of SALT 24, 597–618.

Lyons, John. 1977. Semantics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Malamud, Sophia, and Tamina Stephenson. 2015. Three ways to avoid commitments: Declarative force modifiers in the conversational scoreboard. Journal of Semantics 32: 275–311.

Matyiku, Sabina Maria. 2017. Semantic effects of head movement: Evidence from negative auxiliary inversion. PhD diss, Yale University.

McCready, Elin. 2010. Varieties of conventional implicature. Semantics and Pragmatics 3(8): 1–57. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.3.8.

Nilsenova, Marie. 2002. A game-theoretical approach to the meaning of intonation in rising declaratives and negative polar questions. In Proceedings of speech prosody 2002, eds. B. Bel and I. Marlien. Aix-en-Provence, France.

Northrup, Oliver. 2014. Grounds for commitment. PhD diss, University of California, Santa Cruz.

Potts, Christopher. 2005. The logic of conventional implicatures. Oxford studies in theoretical linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Potts, Christopher. 2007. The expressive dimension. Theoretical Linguistics 33(2): 165–197. https://doi.org/10.1515/TL.2007.011.

Potts, Christopher. 2003. The logic of conventional implicatures. PhD diss, University of California, Santa Cruz.

Recanati, François. 2004. Pragmatics and semantics. In Handbook of pragmatics, ed. Larry Horn and Gregory Ward, 442–462. Oxford: Blackwell.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left-periphery. In Elements of grammar, ed. Liliane Haegeman, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Roelofsen, Floris, and Donka F. Farkas. 2015. Polarity particle responses as a window onto the interpretation of questions and assertions. Language 91(2): 359–414.

Rooth, Matts. 1985. Association with focus. PhD diss, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Speas, Magaret, and Carol Tenny. 2003. Configurational properties of point of view roles. In Asymmetry in grammar, 315–344. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Spector, Benjamin, and Paul Egré. 2015. A uniform semantics for embedded interrogatives: An answer, not necessarily the answer. Synthese 192(6): 1729–1784.

Stevenson, Charles Leslie. 1937. The emotive meaning of ethical terms. Mind 46(181): 14–31. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2250027.

Sudo, Y. 2013. Biased polar questions in English and Japanese. In Beyond expressives: Explorations in use-conditional meaning, current research in the semantics/pragmatics interface (CRiSPI), eds. Daniel Gutzmann, and Hans-Martin Gaertner. Vol. 28, 275–295. Leiden: Brill.

Sugimura, Yasushi. 2004. Gaizensei o arawasu fukushi to bunmatsu no modality keishiki (Adverbs of probability and sentence-final modality expressions). Gengo Bunka Ronshuu 25(2): 90–111.

Tenny, Carol. 2006. Evidentiality, experiencers, and the syntax of sentience in Japanese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 15(3): 245–288.

Theiler, Nadine, Maria Aloni, and Floris Roelofsen. 2018. A uniform semantics for declarative and interrogative complements. Journal of Semantics 35(3): 409–466. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffy003.

Tomioka, Satoshi, and Dursun Altinok. 2021. Right dislocation at the grammar-discourse crossroads. Talk presented at ICU LINC.

Truckenbrodt, H. 2006a. On the semantic motivation of syntactic verb movement to C in German. Theoretical Linguistics 32(3): 257–306.

Truckenbrodt, Hubert. 2006b. Replies to the comments by Gärtner, Plunze and Zimmermann, Portner, Potts, Reis, and Zaefferer. Theoretical Linguistics 32(3): 387–410. https://doi.org/10.1515/TL.2006.025.

Uegaki, Wataru. 2015. Interpreting questions under attitudes. PhD diss, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Uegaki, Wataru, and Floris Roelofsen. 2018. Do modals take propositions or sets of propositions? Evidence from Japanese darou. In Proceedings of SALT 28, 809–829.

Venditti, Jennifer J. 2005. The J_ToBI model of Japanese intonation. In Prosodic typology: The phonology of intonation and phrasing, ed. Sun-Ah Jun, 172–200. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

von Fintel, Kai, and Anthony S. Gillies. 2010. Must ... stay ... strong! Natural Language Semantics 18(4): 351–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-010-9058-2.

Westera, Matthijs. 2013. ‘Attention, I’m violating a maxim!’ A unifying account of the final rise. In Proceedings of the 17th workshop on the semantics and pragmatics of dialogue (SemDial), Amsterdam.

Zanuttini, Raffaella, and Paul Portner. 2003. Exclamative clauses: At the syntax-semantics interface. Language 79: 39–81. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2003.0105.

Zeevat, Henk. 2004. Particles: Presupposition triggers, context markers or speech act markers. In Optimality theory and pragmatics, 91–111. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Zimmermann, Malte. 2004. Discourse particles in the left periphery. In Proceedings of the dislocated elements workshop, ZAS Berlin (ZAS papers in linguistics 35), eds. Benjamin Shaer, Werner Frey, and Claudia Maienborn, 544–566. Berlin: ZAS.

Acknowledgement

This work is partly supported by JSPS Kiban (C) “Semantic-Pragmatic Interfaces at Left Periphery: a neuroscientific approach” (18K00589). I would like to thank anonymous reviewers for Natural Language & Linguistic Theory and Roumyana Pancheva for insightful and encouraging comments as well as Christopher Davis, Regine Eckardt, Daniel Gutzmann, Yuki Hirose, Magdalena Kaufmann, Shigeto Kawahara, Sven Lauer, Elin McCready, Anne Peng, Katsuhiko Sano, Satoshi Tomioka, and the audience at Okinawan Semantics Workshop (30–31 July, 2016), the 25th Japanese/Korean Linguistics Conference (October 12–14, 2017) and the colloquium at University of Konstanz (January 24, 2019) for helpful discussion. All remaining errors are mine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Head movement and the interpretation of its trace

The movement of daroo skips over the question particle ka, which apparently violates the Head Movement Constraint (HMC). In fact, English has a similar construction, where a modal below a functional head undergoes covert raising and hence violates the HMC, resulting in a wide-scope interpretation for the modal over the functional head. More concretely, the verb seem in (141) raises over can and negation as indicated in the paraphrase (Langendoen 1970; Jacobson 2006; Homer 2011):

-

(141)

John can’t seem to run very fast. (Langendoen 1970: 25)

Paraphrasable as: It seems that John is not able to run very fast. (seem > not > can)

Homer (2011) argues that seem is a mobile PPI (positive polarity item), and so has to outscope negation (or downward-entailing expressions), which results in the wide scope interpretation in (141). The analysis is motivated by the fact that the scope reversal happens only with negation (see Homer 2011 for discussion).

To the author’s knowledge, the first work which studies the semantic effects of head movement is done by Matyiku (2017). Matyiku (2017) investigates negative auxiliary inversion in West Texas English. In this variety of English, a negated auxiliary can precede a quantified subject as in (142). (142) is uttered with falling intonation and is not an interrogative but a declarative. The negation in the inverted form unambiguously takes scope over the quantifier, while the non-inverted form in (142b) is ambiguous between the surface scope and the inverted scope.

-

(142)

-

a.

Don’t many people like you. (unambiguous: not > many; *many > not)

-

b.

Many people don’t like you. (ambiguous: not > many; many > not)

-

a.

Matyiku (2017) argues that the inverted form (142a) and the negation-wide-scope reading of the non-inverted form (142b) are both derived by raising the negated auxiliary higher than the subject. However, Matyiku (2017) shows that raising the negation is not enough to obtain the desired reading. This is because negation is interpreted at the original position even after being QR-ed (See Tree 3.17 in Matyiku 2017: 82), so the composition would end up with the subject outscoping negation, i.e., many>¬. Matyiku (2017) offers two options to obtain the desired reading. One is to raise the type of negation to 〈〈〈t,t〉,t〉,t〉 (see Tree 3.18 in Matyiku 2017: 83). The other is to delete the trace of negation (see Tree 3.19 in Matyiku 2017: 84). Matyiku (2017) states that there is no preference between the two options.

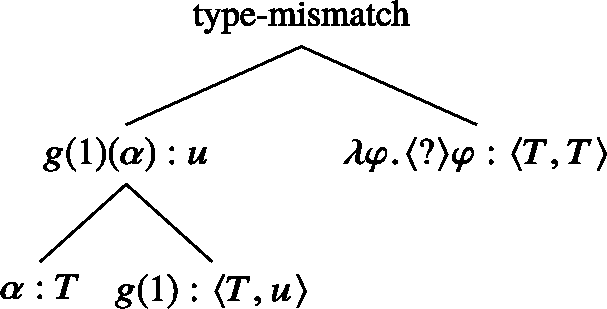

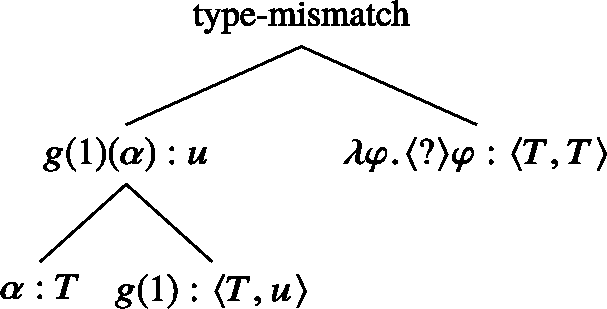

Turning to the raising of daroo in a falling daroo-interrogative like (108), we will face the same problem as the raising of the negated auxiliary. That is, the interpretation of daroo would be reconstructed into the base-generated position. Before seeing how the derivation runs into a problem, we first assume that the trace of daroo is of truth-conditional type 〈T,T〉, which I believe is a reasonable assumption. If it were of type 〈T,u〉, it would cause a type mismatch before merging with raised daroo as in (143).

-

(143)

However, even with that assumption, the derivation would result in a type-mismatch since the interpretation of daroo is forced to be reconstructed into the base-generated position.

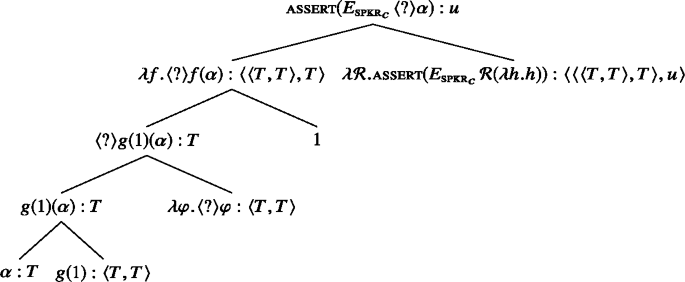

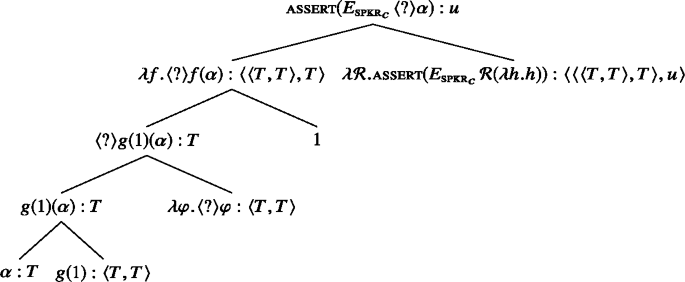

Now let us try Matyiku’s (2017) two options. First, we raise the type of daroo to 〈〈〈T,T〉,T〉,u〉. Together with the assumption that the trace is of type 〈T,T〉, we obtain the desired interpretation  .

.

-

(144)

Second, we delete the trace or assume that the movement of head does not leave a trace. As we have seen in (109), this also correctly derives the desired interpretation.

Now, do we have a preference for one over the other? I think we do. The first option requires two assumptions: 1. The trace of daroo is of at-issue type 〈T,T〉; 2. Daroo has a complex type 〈〈〈T,T〉,T〉,u〉, which is needed only for the falling interrogative-daroo construction. On the other hand, the second option only needs one assumption, that the trace is deleted or that there is no trace for head movement. Thus, the current manuscript adopts Matyiku’s (2017) second option and assumes that movement of heads does not leave a trace or that the trace is deleted.

Appendix B: Formal system of \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}\)

The formal system of \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}\) is based on McCready’s \(\mathcal{L}_{\mathit{CI}}^{+S}\), which in turn is based on Potts’ \(\mathcal{L}_{\mathit{CI}}\). It also incorporates Gutzmann’s notion of use-conditions, so a new basic shunting use-conditional type u is added to the system. Furthermore, a use-conditional product type (u × u), which arises from the paratactic association rule, is added to the system. The system does not include other non-descriptive types such as CI types (\(e^{c},t^{c},s^{c}\)), shunting types (\(e^{s},t^{s},s^{s}\)) or mixed types since the current paper only deals with the shunting-type UCIs (daroo, ka↑ and ↑) as well as descriptive content and does not discuss prototypical expressives such as damn as discussed in Potts (2005) (except for the ones mentioned in Sect. 5.1 and Appendix C) nor the mixed-type expressives discussed in McCready (2010).

-

(145)

Types for \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}\)

-

a.

e, t, s are basic truth-conditional types for \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}\).

-

b.

u is a basic shunting use-conditional type for \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}\).

-

c.

If σ and τ are truth-conditional types for \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}\), then 〈σ,τ〉 is a truth-conditional type for \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}\).

-

d.

If σ is a truth-conditional type for \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}\) and τ is a use-conditional type for \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}\), then 〈σ,τ〉 is a use-conditional type for \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}\).

-

e.

If σ and τ are use-conditional types for \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}\), then σ × τ is a use-conditional product type for \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}\).

-

f.

The full set of types for \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}\) is the union of the truth-conditional types and the use-conditional types for \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}\).

-

a.

Similarly, \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}\) is different from McCready’s (2010) in that it does not include CI application nor rules for mixed types but contains the Paratactic Association rule.

-

(146)

Rules of proof in \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}\)

-

a.

Reflexivity Axiom

-

b.

Functional Application

-

c.

Predicate Modification

-

d.

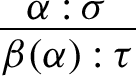

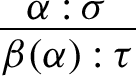

Feature Semantics

(where β is a designated feature term)

-

e.

Shunting-type Application

-

f.

Paratactic Association

-

a.

Appendix C: Modal adverbs as non-shunting UCIs

In Sect. 5.1, I propose that modal adverbs such as kitto ‘certainly,’ tabun ‘probably,’ and moshikasuruto ‘maybe’ are non-shunting UCIs, and so are similar to canonical expressive items that project both truth-conditional and use-conditional meanings à la Potts (2005). To implement this idea, we need to extend \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}\) so that we can distinguish shunting and non-shunting use-conditional types. Thus, in the extended system \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}^{+}\), (145b) is replaced by (147) and all the u’s in (146) are replaced by \(u^{s}\).

-

(147)

-

a.

\(u^{s}\) is a basic shunting use-conditional type for \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}^{+}\).

-

b.

\(u^{c}\) is a basic non-shunting use-conditional type for \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}^{+}\).

-

a.

Furthermore, Potts’ (2005) CI application is added back to the set of rules in \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}^{+}\).

-

(148)

CI application

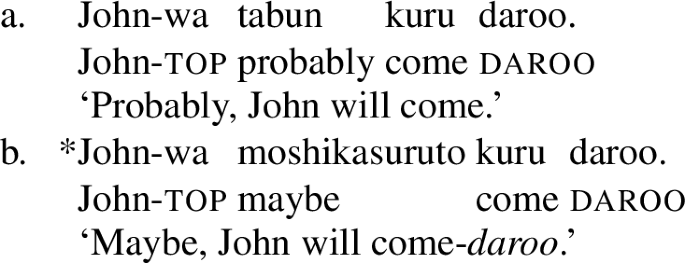

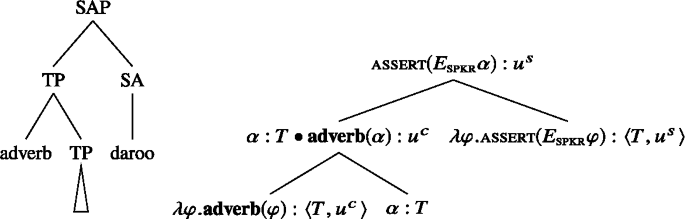

Now, let us see how sentences with daroo and modal adverbs like (149) are composed in \(\mathcal{L}_{\otimes}^{+}\).

-

(149)

First, I propose that both tabun and moshikasuruto are non-shunting use-conditional items of type \(\langle T,u^{c}\rangle \).

-

(150)

\([\!\![\textbf{tabun}]\!\!], [\!\![\textbf{moshikasuruto}]\!\!]\in D_{\langle T,u^{c}\rangle}\)

Thus, when they are combined with their prejacent propositions, the rule of CI application (148) applies and projects a pair of expressions, the truth-conditional prejacent proposition α and the use condition adverb(φ), as depicted in (151). Then daroo takes α as its argument and outputs a shunting-type use condition.

-

(151)

Therefore, as far as the composition is concerned, the derivations of tabun-α-daroo and moshikasuruto-α-daroo should both converge. The ungrammaticality of (149b) comes from the fact that the resulting pair of use conditions is incongruous. To see this, I propose the use conditions of tabun ‘probably’ and moshikasuruto ‘maybe’ as follows:

-

(152)

-

a.

-

b.

-

a.

The use condition of tabun is compatible with that of daroo, which says that  is in the speaker’s discourse commitments

is in the speaker’s discourse commitments  . The speaker finds φ more likely than the alternative and adds φ to her commitment set. On the other hand, the use condition of moshikasuruto is incompatible with that of daroo. The speaker finds φ less likely than ¬φ yet adds φ to her commitment set.

. The speaker finds φ more likely than the alternative and adds φ to her commitment set. On the other hand, the use condition of moshikasuruto is incompatible with that of daroo. The speaker finds φ less likely than ¬φ yet adds φ to her commitment set.

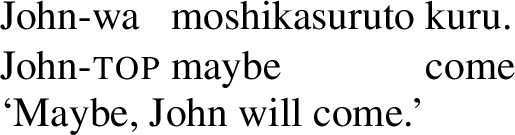

As readers may notice, treating moshikasuruto as a non-shunting UCI causes the original problem to return. That is, when it does not co-occur with daroo as in (153), the use-conditional meaning would weaken the truth-conditional one, ‘α and maybe α.’

-

(153)

I see two ways to solve the problem. One is to propose that when there is no sentence-final auxiliary that acts as a speech act operator as in (153), moshikasuruto becomes one. Thus, the only use condition of (153) is  . Alternatively, in (153), the default assert operator only pushes α onto the Table and does not alter the speaker’s discourse commitments

. Alternatively, in (153), the default assert operator only pushes α onto the Table and does not alter the speaker’s discourse commitments  . The latter proposal is motivated by the intuition that in uttering (153), the speaker merely presents a possibility of α without fully committing herself to it. Since we do not have further data to decide one over the other, I leave this issue for future research.

. The latter proposal is motivated by the intuition that in uttering (153), the speaker merely presents a possibility of α without fully committing herself to it. Since we do not have further data to decide one over the other, I leave this issue for future research.

The analysis just sketched here is based on Hara (2006: Ch. 5), who categorizes modal expressions into two groups, propositional and expressive. I refine Hara’s taxonomy and add more items as in (154):

-

(154)

Taxonomy of Japanese modal expressions

-

a.

truth-conditional items (〈T,T〉)

kanarazu ‘certainly,’ kanousei-ga aru/hikui/takai ‘The possibility exists/is low/is high,’

nichigainai ‘must,’ kamosirenai ‘might’

-

b.

use-conditional items

-

i.

shunting-type (\(\langle T, u^{s}\rangle \))

daroo ‘probably/I bet’

-

ii.

non-shunting type (\(\langle T, u^{c}\rangle \))

kitto ‘certainly,’ tabun ‘probably,’ moshikasuruto ‘maybe’

-

i.

-

a.

It is not accidental that all the non-shunting type UCIs are adverbs and the only shunting-type UCI is daroo, which is a sentence-final auxiliary. Modal adverbs are sentence-modifiers and just like the prototypical expressives discussed by Potts (2005: 11), they “[comment] on a semantic core.” On the other hand, daroo and the other shunting-type UCIs, i.e, ka↑ and ↑, which are sentence-final particles, are speech act operators, and therefore act as the semantic core of the utterances.

Appendix D: Comparison with Uegaki and Roelofsen (2018)

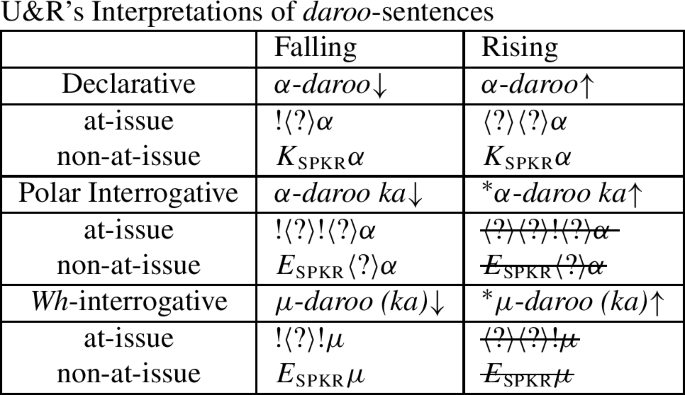

One of the core proposals of the current paper is that Japanese modal auxiliairy daroo is an entertain modality that can embed both declarative and interrogative clauses without reducing the latter to declarative ones. To the author’s knowledge, the same claim is made by two works, Hara (2018) and Uegaki and Roelofsen (2018). Hara (2018) is a precursor of the current paper. Uegaki and Roelofsen (2018) use the observations reported in Hara (2006) and Hara and Davis (2013) to argue against the assumption that modals only embed declarative clauses and for an inquisitive semantics that treats declarative and interrogative clauses uniformly.

This section critically reviews Uegaki and Roelofsen (2018) (U&R, henceforth) and points out its problems. Not only is their analysis of daroo not novel in that the claim that daroo is an interrogative-embedding modal is already made by Hara (2018), but also their implementation makes wrong predictions for empirical data.

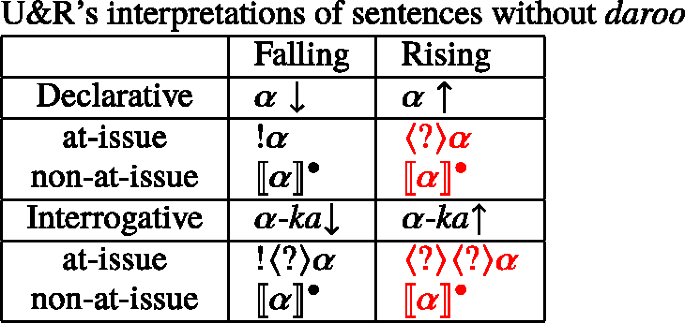

U&R situated their analysis in the framework of two-dimensional semantics, at-issue and non-at-issue (expressive). At the at-issue level, φ-daroo projects a question meaning 〈?〉!φ (\([\!\![!\varphi ]\!\!]=\{p|p \subseteq |\varphi |_{M}\}\)). At the same time, at non-at-issue level, it projects ‘the speaker entertains φ.’ (According to Wataru Uegaki p.c., \(\cap [\!\![\varphi ]\!\!]^{\bullet}\) “is there to make sure that the non-at-issue meaning of φ-daroo inherits the non-at-issue meaning of φ. [...] [I]t can make a difference if for example φ contains an appositive.” Since it does not make a difference for the data discussed in the current paper and U&R do not discuss how their at-issue and non-at-issue compositions work, following U&R, I ignore the \(\cap [\!\![\varphi ]\!\!]^{\bullet}\) part in the rest of this discussion.)

-

(155)

-

a.

〚φ daroo〛 = 〚〈?〉!φ〛

-

b.

-

a.

U&R treat both ↓ and ↑ as intonational morphemes and propose the following semantics:

-

(156)

-

a.

〚φ↓〛 = 〚!φ〛

-

b.

\([\!\![\varphi \downarrow ]\!\!]^{\bullet}=[\!\![\varphi ]\!\!]^{\bullet}\)

-

a.

-

(157)

-

a.

〚φ↑〛 = 〚〈?〉φ〛

-

b.

\([\!\![\varphi \uparrow ]\!\!]^{\bullet}=[\!\![\varphi ]\!\!]^{\bullet}\)

-

a.

-

(158)

-

a.

〚φ ka〛 = 〚〈?〉φ〛

-

b.

\([\!\![\varphi \, {\mathrm{ka}} ]\!\!]^{\bullet}=[\!\![\varphi ]\!\!]^{\bullet}\)

-

a.

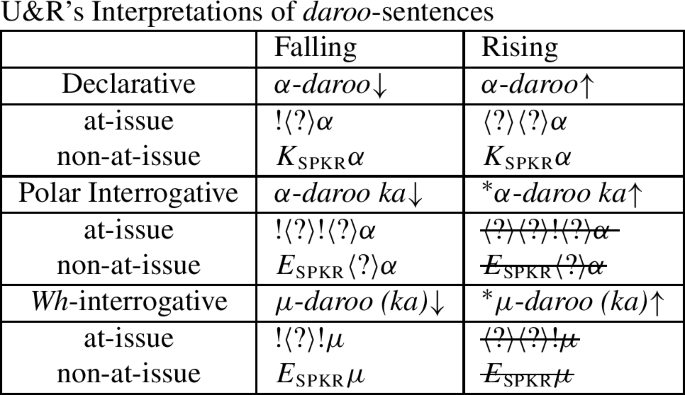

As can be seen, ↑ and ka are defined as synonymous. Given these denotations, U&R derive the interpretations for falling and rising declaratives, polar and wh interrogatives summarized in (159): α-daroo↓ projects a tautologous at-issue meaning 〚!〈?〉α〛 = ℘(⋃(〚α〛∪〚¬α〛)) and non-at-issue bias  . α-daroo↑ projects an at-issue question 〚〈?〉〈?〉α〛 = 〚〈?〉α〛 (since the iteration of 〈?〉 has no effect) and non-at-issue bias

. α-daroo↑ projects an at-issue question 〚〈?〉〈?〉α〛 = 〚〈?〉α〛 (since the iteration of 〈?〉 has no effect) and non-at-issue bias  which explains its tag-question-like interpretation. α-daroo ka↓ projects a tautologous proposition at at-issue and conveys that the speaker entertains an issue 〈?〉α, i.e.,

which explains its tag-question-like interpretation. α-daroo ka↓ projects a tautologous proposition at at-issue and conveys that the speaker entertains an issue 〈?〉α, i.e.,  as non-at-issue content. A rising interrogative α-daroo ka↑ is ruled out by a blocking effect: It has exactly the same effect as the falling interrogative α-daroo ka↓ but is more marked since it involves ↑.

as non-at-issue content. A rising interrogative α-daroo ka↑ is ruled out by a blocking effect: It has exactly the same effect as the falling interrogative α-daroo ka↓ but is more marked since it involves ↑.

-

(159)

Turning to wh interrogatives, μ-daroo↓ projects a tautologous proposition !〈?〉!μ as at-issue and indicates that the speaker entertains an issue μ, i.e.,  . μ-daroo ka↓ has exactly the same at-issue and non-at-issue meanings since μ is already inquisitive, so adding 〈?〉 has no effect. In contrast, the falling wh interrogatives μ-daroo↑ and μ-daroo ka↑ project the tautologous !〈?〉!μ and

. μ-daroo ka↓ has exactly the same at-issue and non-at-issue meanings since μ is already inquisitive, so adding 〈?〉 has no effect. In contrast, the falling wh interrogatives μ-daroo↑ and μ-daroo ka↑ project the tautologous !〈?〉!μ and  . These at-issue and non-at-issue meanings are identical to those derived from μ-daroo (ka)↓. Thus, μ-daroo (ka)↑, which contains the more costly ↑, is blocked by μ-daroo (ka)↓.

. These at-issue and non-at-issue meanings are identical to those derived from μ-daroo (ka)↓. Thus, μ-daroo (ka)↑, which contains the more costly ↑, is blocked by μ-daroo (ka)↓.

To explain why μ-daroo ka↓ is not blocked by μ-daroo↓, U&R speculate that μ-daroo ka↓ is not syntactically more complex than μ-daroo↓ since the wh-word such as dare ‘who’ in μ needs to be licensed by a question marker, which may or may not be overtly marked. In other words, U&R adopt a syntactic structure similar to the current proposal, in that μ-daroo↓ also contains a covert question marker.

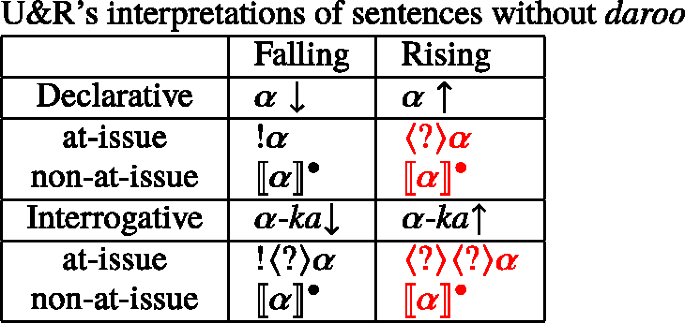

Although U&R’s analysis is elegant in that it maintains a simple and uniform semantics for ka and ↑ as 〈?〉, it faces a number of empirical problems. First of all, the blocking-based account is too strict. Consider falling/rising declaratives and (polar) interrogatives without daroo (see (81), (82), (93) and (87) for example sentences). The derivations that U&R’s analysis would derive are summarized in (160). As can be seen, α↑ and α-ka↑ yield the same semantics, yet α-ka↑ is not blocked. Unlike the wh cases, the sentence α is a declarative which does not contain any wh-word, so α-ka↑ must be syntactically more complex than α↑. Thus, U&R’s analysis wrongly predicts that α-ka↑ would be ungrammatical due to the blocking by α↑ under semantic equivalence.

-

(160)

As we have already seen in Sect. 3.4, my proposal correctly predicts that both α↑ and α-ka↑ are grammatical and give rise to the same interpretations. The ungrammaticality of rising polar and wh daroo-interrogatives, α-daroo (ka)↑ and ∗μ-daroo (ka)↑, is explained by the type-mismatch.

Second, as U&R also admit, it is mysterious how the tautologous proposition derived from the falling interrogative α-ka↓ ends up having an exclamative interpretation. In the current paper, unlike Final Rise ↑, Final Fall ↓ is not an intonational morpheme, but considered to be the default sentential prosody. Thus, under the current analysis, α-ka simply denotes a truth-conditional interrogative clause, which is analogous to a set of alternative propositions in alternative semantics (Rooth 1985). Since it is a truth-conditional type, it can be an argument of another functor such as Zannuttini and Portner’s (2003) Exclamative operator.

-

(161)

Third, since U&R assume that Final Rise and daroo project both at-issue and non-at-issue contents, their analysis makes wrong predictions when these items are embedded. That is, it wrongly predicts that constructions with Final Rise can be embedded questions in the absence of extra syntactic constraints for constructions with Final Rise. Furthermore, it does not derive the correct interpretations when kara ‘because’ embeds a daroo-declarative as seen in (138) in Sect. 5.2.

In summary, U&R’s analysis makes a number of wrong predictions. First, it incorrectly rules out rising polar interrogatives without daroo, α-ka↑. Second, it does not leave room to explain why falling interrogatives are interpreted as exclamatives. Third, it makes wrong predictions regarding embeddings of Final Rise and daroo. Finally, as also mentioned in Sect. 5.2, it is conceptually problematic to categorize the semantics of daroo as “non-at-issue” content since it is the main content of the sentence, and so it should actually be treated as “at-issue” content.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hara, Y. *Daroo ka↑: the interplay of deictic modality, sentence type, prosody and tier of meaning. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 42, 95–152 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-023-09573-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-023-09573-6

. We could incorporate this presupposition in the use conditions of (-ka)↑ as in (85):

. We could incorporate this presupposition in the use conditions of (-ka)↑ as in (85):

, and so pushes the modalized sentence

, and so pushes the modalized sentence  onto the Table. When the addressee accepts the speaker’s assertion, therefore, what enters the common ground will be

onto the Table. When the addressee accepts the speaker’s assertion, therefore, what enters the common ground will be  , not α. On the other hand, rising α-daroo is a combination of two speech acts, an assertion of

, not α. On the other hand, rising α-daroo is a combination of two speech acts, an assertion of  and a question ?α. The question act pushes the issue ?{α,¬α} as well as

and a question ?α. The question act pushes the issue ?{α,¬α} as well as  onto the Table, so when the addressee responds with ‘yes’, α will enter the common ground.

onto the Table, so when the addressee responds with ‘yes’, α will enter the common ground.